new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Carnegie Medal, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 79

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Carnegie Medal in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

.jpeg?picon=3348)

By:

PJ Reece,

on 4/17/2016

Blog:

PJ Reece - The Meaning of Life

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Blog,

Why we read,

Story structure,

Heart of the story,

How Fiction Works,

Story Structure to Die for,

Ask the Dust,

Don't get it right get it written,

The hero must die,

Add a tag

I teach the “2-story” story.

I teach the “2-story” story.

Never mind the three-act structure, the best stories can be said to consist of two stories separated by a bottomless hole. Where the hero “dies.”

STORY ONE—from the opening line to the protagonist’s loss of faith in him/herself.

STORY TWO—the protagonist emerges from the hole armed with the moral authority to resolve the story.

THE HOLE—the heart of the story, where all is lost and all is gained. And where audiences, instinctively aware that principles and beliefs obscure our greatest happiness, swoon.

In the first of six classes I’m giving here in my seaside village of Gibsons, British Columbia, I asked the class to consume their fiction with an eye out for that blessed hole in the story. Films depict this essential story moment more obviously that novels. But to my surprise the novel I’m currently reading offered up one of the most graphic examples.

Ask the Dust, by John Fante.

Even you, Arturo, even you must die

The protagonist, young Arturo Bandini, a struggling writer in L.A., jeopardizes his happiness by treating other ethnics as badly as he was treated as an immigrant child in Colorado. After sexually mistreating a Jewish woman, his self-respect plummets. Listen as Arturo comes untethered from his own long-held beliefs about the way the world works:

“Then it came to me like crashing and thunder, like death and destruction. I walked away in fear… passing people who seemed strange and ghostly: the world seemed a myth, a transparent plane, and all things upon it were here for only a little while… We were going to die. Everybody was going to die. Even you, Arturo, even you must die.”

Arturo’s first thought is of death, corporeal death. But until that happens he’s stuck suffering the more painful loss of his belief system.

“Sick to my soul, I tried to face the ordeal of seeking forgiveness. From whom? What God? What Christ? They were myths I once believed, and now they were beliefs I felt were myths.”

A sick soul cannot fuel the organism. A person with no beliefs has no goal. Character, which is synonymous with plot, comes to a full stop.

End of Story-One.

“I said a prayer but it was dust in my mouth. No prayers. But there would be some changes made in my life. There would decency and gentleness from now on. This was the turning point. This was for me, a warning to Arturo Bandini.”

Story-Two begins. It’s a different protagonist who drives the story to its completion.

So, who else spotted a hole in a story this week?

Look! The story has a hole in it!

I have critics who insist that my so-called “story heart” presents nothing new, that I’m simply describing the well-known Act II crisis, which is true. There’s no need for me to stand on my soapbox and shout:

“Look!—there’s a hole in my story! And everything’s flowing into it!”

But, really, I do. In my opinion, its significance overshadows all other story elements. Look what’s getting sucked into that black hole:

The protagonist—disillusioned with the utter failure of his strategies, he falls off the time line into the hole. Really, he’s out of time. What a relief.

Ergo, the plot likewise disappears—bye, bye, for now.

The readers, there they go. Vicariously escaping the prison of narcissistic beliefs, they’re free at last. Every story is an escape story, and the hole is the portal to freedom. For readers, this is the payoff. But for real life interfering, this is where our deepest yearnings would lead. This is where drama delivers. This is where we get our money’s worth.

The writer, too, of course. There she goes, having spent how long loving her protagonist all the way to this dark heart. A writer lives for the moment she can deliver her hero to the hole in the story.

Arguably—I’m working on a proof—we writers are nourished daily by loving our fictional characters in this way.

In this week’s class we discuss “characters.”

Character as plot, as the story engine, and why the hero must die.

This is a children’s picture book structure break down for Mousetropolis by R. Gregory Christie. This breakdown will contain spoilers. Once upon a time: (Pages…

When struck with a shiny new idea, all you want to do is get stuck into creating it into the masterpiece you know it can be. For some of us, that means sitting down and plotting up a storm. For others, it means jumping straight into that first draft. And for some of us, it simply means grabbing a pen and paper and dreaming the day away.

Whatever your preferred method, structure and plot is an important part of making a novel come to life. So whether you're a pantser, or a plotter, or somewhere in between, you'll no doubt find the posts below invaluable. Read on for a collection of posts aimed at shaping your story into the best story it can possibly be.

Read more »

The fact that the Heart doesn’t show up in most fiction formulas is meant to alarm writers.

One reader must have become alarmed after reading it in my new article: THE HEART OF THE STORY: What Is it, Where Is it, and How Do We Get There?

I’m grateful to writer, Rahma Krambo, for Tweeting it because it reminds me why I’ve been hammering away on this issue for so long. The Heart doesn’t appear in most writing manuals!

Is anybody else alarmed?

It surprises me that I hadn’t previously devoted an article to the Story Heart such as I’ve done here — not on my own blog but over at Helping Writers Become Authors.

Click on over and see what all the ruckus is about.

I have to thank K.M. Weiland for offering her wonderful website for my heart rant. I can’t think of another writer who appreciates what might really be going on in this little-known heart of a story.

Thanks, Katie!

Coming up in a day or two, the next episode in my Travel Series:

Deep Travel: When Have You Gone Too Far?

The writer’s journey. The hero’s journey. Springtime and the open road.

The writer’s journey. The hero’s journey. Springtime and the open road.

Road stories!

I’m itching to recount my stories of the road—in Africa, India, Pakistan, Alberta, Samoa, Greece, Scotland, Italy, the high Arctic, New Zealand.

In my last post we didn’t get far before I ran into the bees.

Next up is an encounter with “simba” on the Hell Run in Tanzania.

But first a short detour to the UK where the Writers’ Village is graciously hosting my guest blog about “traveling light.”

If you’re a writer with a toolbox over-heavy with tips about story mechanics, then here are more tips! To lighten your load.

Traveling light on your writer’s journey—THIS WAY...

And after you’ve read my Reece’s Piece, join the discussion already in progress…

I love insightful, meaty craft articles that help me both improve my knowledge of storytelling while also pushing me to analyze my current WIP. Today's Craft of Writing post comes from author Ara Grigorian, who expertly does both. And he does so with examples from two movies that I loved: Notting Hill and The Hunger Games. I know I'm going to be using his fabulous analysis to help with my upcoming revision! Hope you will too. And be sure to check out his upcoming release, Game of Love, which has been receiving glowing reviews, at the bottom of the post!

Finding Your Story’s Beats by Ara Grigorian

Stephen King has said time and again, if you want to be a better writer, you have to read a lot and write a lot. I will humbly add one more task to your to-do list. If you want to be a better storyteller, watch more movies.

Okay, okay, set down the pitchforks and torches. Yes, we all understand that movies are never as good as the books. And no, we're not trying to write a screenplay, we're trying to write better books. So what am I really talking about?

If you’re writing commercial fiction, where pacing, strong plot points, and increased tension in your selected genre matters, then our brothers and sisters who write scripts can teach us plenty.

This past February, I taught a workshop at the

Southern California Writers’ Conference in San Diego and again recently at a local high school in Los Angeles. The goal:

help you find your story’s key beats and their timing.

I’ve combined lessons from James Scott Bell (“Plot & Structure,” his workshops and his newly released “Super Structure”), Blake Snyder (“Save the Cat!” series) and John Truby (“The Anatomy of Story”). There are more. Pick your methodology, it doesn’t matter. They are all great and they all show that structure and story is king.

GAME OF LOVE is my debut novel (May 2015, Curiosity Quills Press). But before I got a publishing deal, and before my agent became

my agent, I realized something was missing. I’d get requests for fulls based on the query and first five pages, but something would fizzle.

This is what I did…

I selected nearly a dozen movies that were in my book’s genre, or had characters and situations that aligned well with my book. Why movies and not books? Simple: in ten hours I can watch five movies. In ten hours I can read a good chunk of one book. My goal was to learn, to dissect, and find the patterns, fast! Efficiency and effectiveness are critical to the author who also has a full-time job or other competing priorities.

After the third movie, the patterns emerged. By the tenth, I saw exactly what was missing from my book. I was missing key beats, and furthermore, those that I was hitting, I was hitting them late in the story line. Pacing and powerful, distinct scenes that propel the story forward – that was the secret to getting my book noticed.

First of all, what’s a beat? Per Wikipedia (the source of all truth), a beat is the timing and movement, referring to an event, decision, or discovery that alters the way the goal will be pursued by the protagonist. Key word is,

alter. It needs to be big, powerful.

In my workshop, to drive the point home of these key beats, we dissect movie clips. For this post we will analyze one of my favorite movies,

Notting Hill (NH) with Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant and a few scenes form

The Hunger Games. Spoiler Warning: I give away the ending!

Let’s jump in and analyze the most important scenes:

1.

Opening Image/Disturbance: The opening scene needs to set the mood, style, and stakes. This is also where we get to meet our main character(s) and their “before” world.

Notting Hill opens with a collage of clips where Julia is bombarded by the flash of cameras. A radio personality says she is the “biggest star” by far. The song, “She” plays in the background and if we’re listening to the lyrics we hear, “She may not be what she may seem.” We very quickly understand she’s incomplete. Immediately after we are introduced to Hugh’s character. An unsuccessful bookshop owner who was once married but is now alone, with hopes for romance.

In less than three minutes we get the world of these two characters. We also see that these characters can’t go on like this forever. It is unsustainable. Change, radical change is needed. How quickly have you set up your characters? Furthermore, how obvious are the stakes and the need for transformation?

2.

Theme stated: Blake Synder hammers this one. Early in the story (certainly before the 5% mark of your story) the theme will get stated in the form of an innocent question or statement. The main character will not get the significance, but this is the core of the story – the “What’s the story all about.” In the first couple of minutes in

Notting Hill, Hugh says “I always thought she was fabulous, but, you know, a million, million miles from the world I live in.” He’s not talking about the physical distance but the distance between an average guy and a superstar. The theme of this movie is can love overcome the crevasse that lies between a superstar and a nobody. All the challenges they face and all the fun scenes will test the theme.

Read through your manuscript, how quickly are you planting the seed for your reader? Are you then sprinkling the story with situations that revisit this theme?

3.

Catalyst/Inciting Incident/Trouble Brewing: This is where the main character’s world is thrown off balance – a life-changing moment. In

Notting Hill, Julia walks into Hugh’s store where they first meet (a small incident). Shortly after she leaves, he accidentally spills orange juice all over her (a bigger incident). She goes to his place to change (definitely merits a Facebook post!). Then to really throw his world into a tailspin, she kisses him. That is the catalyst moment. He is hooked.

Make sure your catalyst isn’t just a plot device but tied directly to the story and the theme.

4.

Break into Two/First Doorway of No Return: This is a powerful scene where the protagonist makes a definitive decision to pursue the journey, as crazy as it may seem. A decision that has no turning back. This is key because if the protagonist can say, “never mind” then it’s not a big enough pull to force the plot forward. The motivation has to be primal: love, fear, death, life, etc. and still tied to the theme. In

Notting Hill, he has fallen for her, badly. At first she’s pushes back but she also can’t help but be attracted to him – he’s different. Not like the celebrity types, so she decides to take a chance and goes on a date with him to his sister’s birthday party. In

Hunger Games, when Primrose is called for the reaping, Katniss makes an immediate decision – she will volunteer. Not because she thinks she can win, but because she needs to save her sister. Can Katniss change her mind? No way!

Do you have a scene that’s this big where your main character makes a decision that is profound and impossible to turn back from? What propels the call to adventure in your book?

5.

Mid-Point/Mirror Moment: This is a critical scene because this is where the dynamics of the story change. After the break into two, the scenes that follow are fun. They show us the promise of the premise. The main character lives in the upside down world of the choice that’s been made. In

Notting Hill, Hugh experiences the world of the celebrity while Julia lives in his simple world. But after all that fun stuff a key scene is needed that shows the bad guys are getting ready to ruin the party. Time clocks appear here. In

Notting Hill, Hugh discovers that she still has a boyfriend and in a beautifully shot scene on the streets of London, then on a bus, and finally in his bedroom we see it on his face -- he is taking inventory of the mess that is his life. In

Hunger Games, after all the training and the fun of the capital, the games begin. She’s on the platform, scared for her life.

What happens halfway in your story? Is there a moment where your main character is thinking, what have I done? Maybe even stares into the mirror wondering who is that person reflecting back at her?

6.

All is Lost/Dark Night of the Soul/Lights Out: A scene where the main character is now officially worse off than when the story first started. Feels like total defeat. In

Notting Hill, when he finds her again during a shoot, he overhears her with another actor. She dismisses him and says, “I don’t even know what he’s doing here.” He finally gets it and leaves. She then finds him and tries to explain why she said what she said, but he’s done. He can’t take the pain anymore. In a dramatic scene, she says, “And don’t forget, I’m also just a little girl, standing in front of a boy, asking him to love her.” She leaves and Hugh is left stunned.

This is a critical scene because this is where humility will bring the main character to his knees. And from this humility a new idea will rise. The idea that will force the start of the final act.

7.

Break into Three/Second Doorway of No Return: A solution is found. The old world, the old way of being dies and a new world emerges. In

Notting Hill, he calls his friends to tell them what happened. Surrounded by his friends, he realizes that love is worth the pain of uncertainty. He realizes he needs her. And thus, they break into act three.

Your main character’s life is on the line (the alternative is death – professional, emotional, psychological). How big is your scene? Does the reason for the decision to go for it tie in with the theme?

8.

The Final Buildup and Battle: This is where you typically see the hero go up against the clock. He gathers the team, suits up for the challenge, executes the plan, only to be faced by another major challenge. But after digging deep finds a way to get to the final battle. Typically the main character will handle the bad guys in ascending order. In

Notting Hill, it’s a chase scene from one London Hotel to another until he finds her at her last press conference before she leaves the country. In a comedic scene he pretends he’s part of the press and asks, in front of all to hear, if she would consider staying if he admitted that he had been a “daft prick.” She does reconsider and a montage follows, to the music that opened the movie, we see footage from their wedding.

9.

The Final Scene/Resonance: But we’re not done because this is the bookend scene to the opening scene. We need to see the transformation of the character. We need to see that the world has also changed. In

Notting Hill, we started with two lonely people, trying to make it in their own lonely worlds. The movie ends with these two on a park bench, relaxing, he’s reading a book (a good man, clearly!), and she’s pregnant. Alone no more.

How does your story end? Is the final scene a bookend to the opening scene?

For this post, I highlighted nine story beats. You can easily identify 15, 30 or 40 if you invest a bit of time with the methodology of your choice and a day or two of back-to-back movies. I assure you, you will never watch a movie the same way again. And you will be a much more effective storyteller in the genre of your choice.

About the Author:

Ara Grigorian is a technology executive in the entertainment industry. He earned his Masters in Business Administration from University of Southern California where he specialized in marketing and entrepreneurship. True to the Hollywood life, Ara wrote for a children's television pilot that could have made him rich (but didn't) and nearly sold a video game to a major publisher (who closed shop days later). Fascinated by the human species, Ara writes about choices, relationships, and second chances. Always a sucker for a hopeful ending, he writes contemporary romance stories targeted to adult and new adult readers.

He is an alumnus of both the Santa Barbara Writers Conference and Southern California Writers' Conference (where he also serves as a workshop leader). Ara is an active member of the Romance Writers of America and its Los Angeles chapter.

Ara is represented by Stacey Donaghy of Donaghy Literary Agency.

Twitter |

Website |

Facebook |

Goodreads About The Book:

Game of Love is set in the high-stakes world of professional tennis where fortune and fame can be decided by a single point.

Gemma Lennon has spent nearly all of her 21 years focused on one thing: Winning a Grand Slam. After a disastrous and very public scandal and subsequent loss at the Australian Open, Gemma is now laser-focused on winning the French Open. Nothing and no one will derail her shot at winning - until a heated chance encounter with brilliant and sexy Andre Reyes threatens to throw her off her game.

Breaking her own rules, Gemma begins a whirlwind romance with Andre who shows her that love and a life off the court might be the real prize. With him, she learns to trust and love… at precisely the worst time in her career. The pressure from her home country, fans, and even the Prime Minister to be the first British woman to win in nearly four decades weighs heavily.

As Wimbledon begins, fabricated and sensationalized news about them spreads, fueling the paparazzi, and hurting her performance. Now, she must reconsider everything, because in the high-stakes game of love, anyone can be the enemy within… even lovers and even friends.

In the

Game of Love, winner takes all.

Amazon US |

Amazon UK |

Barnes & Noble |

Goodreads-- posted by Susan Sipal,

@HP4Writers

Anyone feel they haven’t read enough “how-to” books on writing?

Anyone feel they haven’t read enough “how-to” books on writing?

Claudia in Mendoza, Argentina, says she hasn’t finished reading John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction.

Go for it, Claudia—Gardner is one of my favourites. But before you go, take two minutes to consider my argument for becoming a writer from the inside out.

First, a confession:

Back in the 90s, I devoured the ‘how-to” gurus — Gardner and Hague and Vogler and Egri and Goldberg and Field and McKee and Campbell and Walter and Ueland and Dillard. Those books still adorn my office, their authors looking over my shoulder as I type. How do I get anything done?

I even wrote one of these books myself. I’m looking over my own shoulder!

That’s the answer, Claudia of Argentina–the answer to the “how-to” dilemma.

Write your own manual.

Thereby will you finally be able to unhook from “how-to.”

7 Suggestions for Unhooking from “How-to”

#1. Consume fiction

Read your brains out. Good fiction and bad. Savour, chew, and digest buckets of it. Reflect on how the best writers did it. How she moved you. How the hell did she make me cry? And laugh! I fall to sleep at night replaying the scenes that blew me away, the scenes that turned the story around. What happened there? How did she do it?

I fall to sleep soothed by the art of fiction

#2. Fall in love with the art of fiction.

Write like a lover. I remember watching sports on television as a kid, and how the instant the game ended we’d bolt out the door, bounding like jackrabbits, to the playing field where we would emulate the champions. We played past sundown, playing our brains out, in the dark—Who has the ball!

I’m equally hopeless whenever I read Virginia Woolf. I rush to my manuscript and emulate the hell out of her. I wrote the 15th draft of my novel ROXY in an adrenaline rush after reading Mrs. Dalloway.

What a joy to write like a lover. We’re not mechanics. Mechanics think. Lovers love their characters ecstatically and to death.

#3. Love your characters to death

There’s nothing “how-to” about this dictum, because no one else can tell you how to love your protagonist to death. You invented him and only you know how to thwart him. But you have to do it, the hero must die. Just do it. It is (arguably) all that counts in fiction. There’s no “how-to” book out there that teaches you how to love your fictional characters to death.

To heck with “how-to”—what about “where to”?

#4. Forget “how-to” in favour of “where-to”

What’s the point of “how to” if we don’t understand “where to”? We wouldn’t buy an appliance without knowing what it’s for. So, what’s fiction for? What’s at the heart of fiction? Is that where it’s going? What’s it all about?

Reading the best fiction we learn (repeatedly) that the best protagonists are on a trajectory toward freedom from their lesser selves. That’s “where to.” That’s (arguably) all we need to know. We keep writing draft after draft until our protagonist has arrived. We know he’s there when he stops kicking and screaming. He’s got that far away look in his eye. He’s gone so far and is so disillusioned with his game plan that he has no alternative but to forsake himself. A higher cause descends. There’s no “how-to” about it. This may look like “how-to,” but it’s not. It’s about understanding the human condition.

#5. Don’t try to BE a writer

“How-to” tomes often coax us to be a writer rather than encourage us to do the hard work that would turn us into writers. That is to say, write your brains out. I’ll bet there are young writers out there reading less literature than “how-to” books. We’re being seduced into posing as writers “rather than spending the time to absorb what is there in the vast riches of the world’s literature, and then crafting one’s own voice out of the myriad of voices.” (author, Richard Bausch)

#6. Don’t get it right, get it written

I sometimes run a course with such a title. Students write at home, then come to class to watch scenes from powerful movies—scenes that give the audience their money’s worth. And by that I mean scenes that depict the hero challenging his own human condition. Challenging the right of his own beliefs to prevent his true happiness.

Immersing ourselves in fiction, we get a feel for a story’s essential payoff. We are astonished each time we recognize it. And then we constructively and lovingly critique each other’s work before bolting for home like jackrabbits.

#7. Write your own “how-to” book

Make notes on your own astonishment at how the best writers serve the art of fiction. Each of our understandings is bound to be unique. Your perspective is going to underpin your own advice about “how-to.” Write that book and put it on the shelf and let it breathe down your neck.

Go for it, Claudia of Argentina. Write your own manual out of love for writing.

Our own “how-to” will be born of the love of the art of fiction.

I was browsing Amazon’s Kindle Store this morning.

I was browsing Amazon’s Kindle Store this morning.

In the Story Structure Department I noticed a drama unfolding:

“Writing by the rules” vs. “Organic writing.”

On one side it’s all structure and story engineering while the other camp is chanting, Don’t get it right, get it written!

But hold on a minute. The traditionalists insist that structure doesn’t mean formulaic.

The debate rages on writing blogs where the “rule rebels” get to express their disenchantment with the confusion of so many story theories. And who can blame them?

Enough already!

To hell with story theories

To hell with graphs and grids and plot points and page counts and blogs and eBooks and audiobooks and podcasts and webinars and all those online courses with all their marketing savvy—that’s the growing mood out there.

One writing guru has published a title clearly meant to fan the flames of discontent. The subtitle of his book reads: How to Write Unforgettable Fiction by Breaking the Rules.

Who doesn’t like to break the rules!

Well, it turns out to be a pretty standard writing text. Can’t say that I’m surprised. The book’s author is an accomplished novelist, he knows very well what a story is. I’ll bet he knows the rules so well that he knows how to break them. He’s probably a master story engineer.

“Prose is architecture,” said Ernest Hemingway.

And if that’s too didactic, try this:

“Structure is only the box that holds the gift.” ~ K.M. Weiland.

That’s straight from K.M. Weiland’s bestseller, Structuring Your Novel.

The gift that lies at the heart of fiction

I love it.

If the rebels reckon they’re beyond story structure, then they should explore “the gift” that lies at the heart of fiction. Yes, there exists a scene in every good story that lies beyond story structure.

I call it the hole in the story.

A story is two stories separated by a gap

The most ruthlessly simple overview of story suggests that a good story is actually two stories separated by a gap.

A chasm so deep that the plot comes to a halt at the brink.

The plot seems to serve this purpose—to hound the protagonist into this existential nothingness. This scene—often called the “Act II crisis”—is structure’s gift.

Story structure exists fore and aft of this hell hole, which becomes for the hero a chrysalis of moral adjustment. This is the gift.

Here, in the heart of the story, the hero disavows himself of himself. All strategies, structures and belief systems fall away and the human organism finds itself in a position to transcend its own self-serving delusions. This is the gift.

I introduce this concept in my short eBook, Story Structure to Die For.

The heart of the story

Fiction moves beyond structure when the protagonist lands in the heart of the story.

The story heart knows nothing of story mechanics. The heart doesn’t do reason or rules. It has nothing but disdain for a character’s logic, strategies, and petty desires.

Here in the heart we encounter a story’s “sacred mechanics.”

Here the hero finds freedom from the rules that have been preventing his true happiness.

Free of rules! This sounds like the very place an “organic” writer wants to be.

But consider this:

If the rule-rebel-writer wants to love her protagonists sufficiently to deliver them to the gift at the heart of the story, she’ll need a structure to get them there.

A writer needs a story structure to love her fictional characters the way a writer ought to.

If thinking of “story” like this makes sense to you, let me know.

Before we roll-out our fabulous lineup of bloggers with great craft of writing tips for 2015, we thought it might be fun to look back over our 2014 craft posts and highlight some of the best tips that we found to be fresh and useful. The ones below come from the first half of 2014 and cover aspects from Character Development to Worldbuilding to Prologues. We hope you'll find a snippet that speaks to you and then click the link to read the full article. And remember the blog labels! Follow

Craft of Writing to read more great craft articles than could be mentioned here.

Finally -- don't forget our new monthly

Ask a Pub Pro column where you can ask a specific craft question and have it answered by an industry professional. So,

get those questions in! Or, if you're a published author, or agent, or editor and would be willing to answer some questions, shoot us an email as well!

Craft of Writing: Best Craft Tips from 2014, part A

Character Development:

Whenever writing a character, always keep one question foremost in mind: what is this character’s motivation? What does this character want? Characters drive stories, and motivation drives character. So that basic motivation should never be too far from the character’s thoughts. What does this character want and what is he or she doing in this scene to get it? It’s almost a litmus test for the viability of a scene. If your character isn’t doing something to get closer to what he or she wants, then you should be asking yourself if the scene is really necessary.

(from

Using Soap Operas To Learn How To Write A Character Driven Story by Todd Strasser on 2/11/14)

Plot Element (A Ticking Clock):

|

| from sodahead.com |

The clock is mainly a metaphor. You can use any structural device that forces the protagonist to compress events. It can be the time before a bomb explodes or the air runs out for a kidnapped girl, but it can also be driven by an opponent after the same goal: only one child can survive the Hunger Games, supplies are running out in the City of Ember....

Only three things are required to make a ticking clock device work in a novel:

-- Clear stakes (hopefully escalating)

-- Increasing obstacles or demand for higher thresholds of competence

-- Diminishing time in which to achieve the goal

(from

The Ticking Clock: Techniques for the Breakout Novel by Martina Boone on 5/20/14)

World Building (Details):

Whenever you have an opportunity to name something or to get specific about a seemingly random detail in your story, do it. Don’t settle for anything vague or halfway. Be concrete. You never know when one of these details might come in handy later. They’re like tiny threads that you leave hanging out of the tapestry of story just to weave them back in again later.

(from

Crafting A Series by Mindee Arnett on 1/28/14)

Editing:

“Write without fear

Edit without mercy”

Your first draft should be unafraid. Personally, I’m a planner, but you don’t have to be; I know published authors who aren’t. The important thing is that you embrace the flow of creation and let the story and its characters live. Don’t judge at this point. Write until it’s done.

Once you have that first draft in place, set the story aside for a few weeks, then take off your writing-hat – with all its feathers and furbelows – and don your editing-hat instead. The hat your inner editor wears is stark. No-nonsense. Maybe a fedora.

(from

Edit Without Mercy by L.A Weatherly on 1/7/14)

GMC:

Even less likeable characters are readable and redeemable so long as they are striving for something they desperately care about. One of the basic tenets of creating a powerful story is that the protagonist must want something external and also need something internal one or both of which need to be in opposition to the antag's goals and/or needs. By the time the book is over, a series of setbacks devised by the antag will have forced a choice between the protag's external want and that internal need to maximize the conflict. The protagonist must react credibly to each of those setbacks, and take action based on her perception and understanding of each new situation.

(from

Use Action and Reaction to Pull the Reader Through Your Story by Martina Boone on 5/2/14)

|

| from pixshark.com |

Theme:

Theme is important when writing. It can be one of the things that puts the most passion into your work. What is it you are really trying to say with this book? You don’t have to know before you start writing. Heck, you don’t even have to know while doing the first revision. But as you go over your manuscript again—and again—you will see things popping out at you. Tell the truth. Dreams matter. Work together. Listen to your own heart. Those are the things that make us fall in love with literature. Once you begin to notice these repetitions (or if you know what you want to say from the start) the real fun begins, because you begin to see all kinds of beautiful ways to make it evident. Symbolism and dialogue and imagery.

(from

Write What You Love and Stay True To Your Passion by Katherine Longshore on 6/20/14)

Story Structure:

On Prologues:

The point I’m trying to make is that you should always strive to be confident in every page, to the point where you should never need a crutch like a prologue. Instead, the beginning needs to be amazing. Not necessarily adrenaline-filled, not necessarily action-oriented. Just damn good. Every page of your book should be, at the very least, strong and interesting writing, and your opening should have the tangible hooks of the ‘problem’ we feel in this book, even if they are only tugging ever so gently. If you have a prologue its worth examining the real page one and making it stronger, finding your real beginning, having faith in your book and your writing. If it doesn’t hold up, prologue or no, the book won’t work.

(from

An Agent's Perspective on Prologues by Seth Fishman on 2/24/14)

On story structure and finding the heart of the story:

As a novelist, I have to be both mother and master of my imagination. Story structure is what both of those roles rely upon—structure nurtures, protects, rules and drives the raw imagination. Months into working on Willow, the other characters began to want to have voice in different ways that the original epistolary form would not have allowed. Although I was confident in the characters, I had to also have confidence in my ability to tap into my imagination and structure it so that the soft, intangible electric energy of the original idea or the heart of the story (what Turkish author Orhan Pamuk calls “the secret center” of the novel) are bolstered and illuminated. Structure is always what I go back to when I’m feeling panic or insecurity.

(from

Wonder Woman's Invisible Jet of Creativity by Tonya Hegamin on 3/28/14)

-- Posted by Susan Sipal

Hi everyone! Welcome back from a wonderful break. I imagine, like us, some holiday rest and relaxation was just what the doctor ordered, but now you are getting a bit itchy, ready to jump back into the fray. To start things off right in 2015, we are diving right into the thick of writing technique with a guest post by author Raven Oak, who is joining us to talk about the successful pattern of Scene and Sequel. This is a must read, especially for those who do not know about this technique. Trust me, your writing will thank you!

Scene and Sequel

When I began writing seriously—not the scribbles in a notebook of plots I’d write someday or the half-started, never-finished stories I cranked out, but the “I want to write novels for a living” point in my career—my first completed book felt juvenile. Portions dragged. And those that didn’t, sped through the action without anyone stopping to smell any proverbial roses. So how does one develop solid pacing through a novel while building tension, developing characters, describing setting, and advancing plot lines? The answer is a little trick called Scene and Sequel. Why? Because humans like patterns.

When I began writing seriously—not the scribbles in a notebook of plots I’d write someday or the half-started, never-finished stories I cranked out, but the “I want to write novels for a living” point in my career—my first completed book felt juvenile. Portions dragged. And those that didn’t, sped through the action without anyone stopping to smell any proverbial roses. So how does one develop solid pacing through a novel while building tension, developing characters, describing setting, and advancing plot lines? The answer is a little trick called Scene and Sequel. Why? Because humans like patterns.

Scene and Sequel is a technique developed by Dwight Swain in his book, Techniques of the Selling Writer. (If you haven’t checked it out, I would strongly suggest doing so as he covers a wide range of simple tricks writers can use to develop better stories.)

Readers pick up a work because they want a powerful and emotional experience. It’s an escape from the drudgery of the real world and a way to live vicariously through others. As a writer, you must create and maintain an illusion strong enough to fool the reader. Pacing helps create and maintain this illusion.

Novels are typically comprised of chapters, which are often made up of scenes. To keep the ebb and flow of a novel going, each scene should then be identified as being a scene or a sequel.

A scene has the following pattern:

- Goal—what the character wants. Must be clearly definable

- Conflict—series of obstacles that keep the character from the goal

- Disaster—makes the character fail to get the goal

And a sequel has the following pattern:

- Reaction—emotional follow through of the disaster.

- Dilemma—a situation with no good options

- Decision—character makes a choice (which sets up the new goal).

To understand how this works, let’s look at A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens.

To understand how this works, let’s look at A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens.

Chapter 1 is a SCENE

- Goal—Scrooge wants money and to be left alone.

- Conflict—When the charity solicitors and Scrooge’s nephew visit, they stir up feelings in Scrooge and memories of his sister, Fran. As Scrooge arrives home, he sees his old business partner’s (Marley’s) face in the doorknocker, and then later in the pictures in his fireplace mantel. Scrooge tries to dismiss the conflicting emotions/thoughts this stirs up.

- Disaster—The disaster is when Marley’s Ghost arrives to warn Scrooge that three ghosts will visit him. Each one has a lesson to teach him. If he doesn’t heed their lessons, Scrooge’s afterlife will be full of pain and misery.

- Scenes tend to be full of action and tension that push the plot forward. Remember, every scene you write must further the plot and/or further the character development.

Chapter 2 is a SEQUEL

- Reaction—Scrooge’s initial reaction is to write off Marley’s visit as the result of some bad food. When the Ghost of Christmas Past arrives, Scrooge tries to send him away. He claims he doesn’t want or need the lesson, but having no choice, Scrooge accompanies the ghost into the past.

- Dilemma—As Scrooge journeys through quite a few joyful and painful memories, he begins to doubt the decisions he’s made. Scrooge faces a dilemma: whether or not to believe himself guilty of bad judgment and humbug, or whether to continue avoiding Christmas, its joy, and his family as he has for many-a-year. Neither are good options, so he picks the option he thinks he can live with.

- Decision—Scrooge decides the past is too painful, because it’s made him doubt himself. In anger, he decides to extinguish the light given by the Ghost of Christmas Past, and thus, his own light. At least momentarily.

What a sequel does is give our character(s) an opportunity for reflection and self-introspection. The decision will lead us into our next scene, where the character(s) develop a new goal. In the case of Scrooge, Chapter 3 (scene) begins with a new goal: Scrooge reacted rashly in extinguishing the light. At the sight of the Ghost of Christmas Present, he decides he will go with him willingly and see what there is to see. And if necessary, think further on his own attitudes and prejudices. He’s not ready for a huge change yet, but change is happening—as change should be happening to your characters as well.

Scenes and sequels should continue to alternate the entire length of the novel, and in doing so, they’ll create a natural flow for both plot progression & character development. Many authors plan or outline the sequence of events using scene & sequel on index cards before writing.

Just about any novel you read will follow this rhythm. It seems simple, but structure usually is. Pick up a book and give it a flip through—I bet it follows the pattern!

Do you use Scene and Sequel, or is this something you’re planning on testing out? Let us know in the comments!

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000447_00014]](http://cdn.writershelpingwriters.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/raven-Oak-188x300.jpg) Guess what? Raven’s Epic Fantasy has just released, so please enjoy this blurb, and if you like, add it to your Goodreads List, or snag a copy from Amazon.

Guess what? Raven’s Epic Fantasy has just released, so please enjoy this blurb, and if you like, add it to your Goodreads List, or snag a copy from Amazon.

Her name was Adelei, a master in her field, one of the feared Order of Amaska. Those who were a danger to the Little Dozen Kingdoms wound up dead by her hand. The Order sends her deep into the Kingdom of Alexander, away from her home in Sadai, and into the hands of the Order’s enemy.

The job is nothing short of a suicide mission, one serving no king, no god, and certainly not Justice. With no holy order to protect her, she tumbles dagger-first into the Boahim Senate’s political schemes and finds that magic is very much alive and well in the Little Dozen Kingdoms.

While fighting to unravel the betrayal surrounding the royal family of Alexander, she finds her entire past is a lie, right down to those she called family. They say the truth depends on which side of the sword one stands. But they never said what to do when all the swords are pointing at you.

Want more Raven? Catch her on Twitter, Facebook or visit her at her website!

The post Writing Patterns Into Fiction: Scene and Sequel appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS™.

By: Joyce Zarins,

on 9/30/2014

Blog:

Constructions: joyce audy zarins

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

children's books,

reviews,

picture books,

Art,

process,

YA fiction,

book art,

work in progress,

story structure,

traditional publishing,

Writing today,

Add a tag

This article is a post I wrote for the fabulous Writers Rumpus blog today, September 30th. While recently reading John Green’s Looking for Alaska, I was surprised by the shape of the story. I’ll get to that in a minute, but it reminded me of other authors who played with the structure of their narratives. […]

Welcome to the final installment of the Adventures in YA Publishing series on serialized novels! Two weeks ago we discussed the surprising pleasures of reading a serial, and last week I gave you some tips on how to write a serialized novel. Today, we’re talking about how to market your serial. Serialized novels are making a big comeback! If you are considering joining the serial revolution, I hope these marketing tips are helpful to you:

|

How do you find readers who will embrace your serial?

Photo credit: Robbert van der Steeg via flickr |

NUMBER, LENGTH, AND PRICE OF INSTALLMENTS

We’re all word-lovers here, so hold on tight: I’m going to throw some numbers at you. According to my (admittedly unscientific) research, while there is no industry standard for price, traditionally-published serials tend to be priced at $1.99 per episode, regardless if the audience is adult, new adult, or YA. The number and length of installments, however, can vary greatly. To compare, I’ll give you four examples: one adult, one new adult, and two young adult:

• Three of the books in

Beth Kery’s BECAUSE YOU ARE MINE adult romance series (Berkley) have eight installments apiece. Each installment is priced at $1.99, and each installment is approximately 55 pages long. The installments of each book were released weekly.

•

Jessa Holbrook’s new adult romance WHILE YOU’RE AWAY (Razorbill) has six installments of about 48 pages each, priced at $1.99 apiece (weekly releases).

•

THE WITCH COLLECTOR by Loretta Nyhan (Harper Teen) is a YA paranormal novel serialized into two parts of 184 and 110 pages respectively, and priced at $1.99 each. Released monthly.

•

The two books in my YA romantic thriller series, RUN TO YOU (Harlequin Teen), have three installments each, averaging 95 pages apiece. They are priced at $1.99 each. The installments of each book were released weekly.

Notice that in the examples above, the YA serials have fewer installments and a much longer length than the adult and new adult serials. Personally, I’m happy that Harlequin Teen serialized my books this way. While it’s not a big deal for an adult to make six or eight purchases of $1.99, teens often don’t have their own accounts with online e-tailers (serials are usually published digitally). To make an online purchase, many teens must first ask their parent’s permission or ask their parents to order it for them—which means for an eight-part serial, they would have to ask permission eight times. Also, an installment of 95+ pages is long enough to leave the YA audience satisfied with both the length and the price they paid. If you are budget-conscious, you will be delighted to note that at $1.99 per installment, the total price of the two- or three-part YA books is still lower than the average full-length digital book. A great deal for the YA audience!

The take-away: While adult and new adult serials have more, shorter installments per book, if you are considering publishing a YA serial, I highly recommend keeping the number of installments low, and the number of pages per installment high.

RELEASE SCHEDULE

Weekly releases seem to be the most popular release schedule lately (although there are exceptions). Why are weekly releases the most popular? Weekly releases give the readers enough time to finish one installment, and they don’t have to wait very long for the next. The book is still fresh on their mind when the next installment is released, so they don’t have time to forget about it and move on to a different book. Also, TV series broadcast their episodes weekly, so we’ve become programmed (pun intended) to enjoy our stories in weekly doses. Finally, for readers who prefer to read the entire book at once, they don’t have long to wait for all the installments to be released.

FINDING READERS

Okay! You’ve determined the length, number, and price of each installment of your serial, you’ve set the release schedule of your serial, and you wrote your serial. Good for you! Now you have to find readers for your serial. I’m not going to lie to you: there are definite challenges to finding readers for a serial. Why?

• Some people won’t read your book simply because of its serialized format. They will see that it’s a serial, and that’s it: they won’t even give it a chance. They want a complete book, and nothing else will do.

• Many readers don’t want to make multiple purchases for the equivalent of one book. They assume every serial will eventually be released as a complete novel, and they’ll wait until then to read it. In my (non-scientific) research, this is by far the biggest reason most people give for not wanting to read a book in serial format. But for some serials, the publisher has no intention of re-packaging it into one complete novel, which unfortunately means those people will never read it.

Other obstacles:

• Some readers will be disappointed that an installment is shorter than a full-length book. They may leave a bad review or give it low stars—not because they dislike the writing or the story, but because they dislike the length or the serialized format. They are perfectly entitled to their opinion, of course. As the author, you just have to hope that they like the story enough to read the next episode. But those bad reviews and lower stars will affect the book’s overall rating.

• All authors spend lots of time promoting their books. But because serials are new and different, you may spend more time explaining the serialized format of your book, rather than explaining what your book is actually about.

OPPORTUNITIES

But fear not, my friends. While there are definite challenges to marketing your serial, there are some unique benefits, additional audiences, and fun opportunities!

Benefits:

• Multiple releases in a short time frame help get an author’s name out faster through consistent exposure week after week.

• A serialized novel offers an author multiple opportunities to communicate with a growing and potential audience in a short time frame.

• Serials offer more opportunities for reviews.

• Multiple installments means multiple covers! Every author knows how hard it is to stand out from the crowd. The multiple, connected covers of your serial are a unique way to catch the eyes of readers.

Additional audiences:

• Serials appeal to busy people. If someone tells me they don’t read books, I often ask them why not. The most common reason: they don’t have the time. But most people have an hour here or there throughout the week, the perfect amount of time to read an episode of a serial.

• Serials appeal to the reluctant and occasional reader. I’ll give you a personal anecdote: I received an email—one I will cherish forever--from a mother who said RUN TO YOU was the first non-school book her teenage daughter had ever read. Her daughter envied her “fangirl” friends who were obsessed with popular YA novels such as HARRY POTTER, THE MORTAL INSTRUMENTS, and DIVERGENT. But those longer tomes intimidated her, and she felt excluded from the book fandom experience. Her mother discovered the RUN TO YOU serial and purchased it for her. Its weekly episodes of 95 pages each were perfect for the girl, who felt accomplished and proud after finishing each installment. Reluctant and occasional readers find serials to be incredibly gratifying.

• Serials also can also appeal to voracious readers. While reluctant and busy readers may take a week to read an episode, avid readers will read an episode in a single sitting. If they still want more, they can wait for all of the installments to release, then read them all at once.

Additional opportunities:

• Serialized novels can make reading a social experience. Like with television series, your readers can read each installment of your serial, then discuss it with each other and online. They will anxiously anticipate the next installment together.

• For example, you can utilize the fun social aspect of serials by having an online read-along! Your current readers will enjoy engaging with other fans, and the read-along will attract new readers as well. (Psst… we’re having a read-along of my serial right now! See the info at the bottom of this post.)

DISCUSSION:

So there you have it, folks: I’ve told you about reading, writing, and marketing serialized novels. Any questions? Ask away!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Clara Kensie grew up near Chicago, reading every book she could find and using her diary to write stories about a girl with psychic powers who solved mysteries. She purposely did not hide her diary, hoping someone would read it and assume she was writing about herself. Since then, she’s swapped her diary for a computer and admits her characters are fictional, but otherwise she hasn’t changed one bit.

Today Clara is the author of dark fiction young adults. Her debut series, the romantic thriller RUN TO YOU, is Harlequin TEEN’s first serial. Book One is First Sight, Second Glance, and Third Charm. Book Two is Fourth Shadow, Fifth Touch, and Sixth Sense.

Her favorite foods are guacamole and cookie dough. But not together. That would be gross.

Find Clara online:

Website Twitter Facebook Tumblr Instagram Goodreads Newsletter

About the books

Good news!

Good news! The first installment of my serial, RUN TO YOU Part I: FIRST SIGHT, is

still free across all e-tailers! It won't last much longer, so get it before the price goes back up!

In Part One of this romantic thriller about a family on the run from a deadly past, and a first love that will transcend secrets, lies and danger…

Sarah Spencer has a secret: her real name is Tessa Carson, and to stay alive, she can tell no one the truth about her psychically gifted family and the danger they are running from. As the new girl in the latest of countless schools, she also runs from her attraction to Tristan Walker—after all, she can't even tell him her real name. But Tristan won't be put off by a few secrets. Not even dangerous ones that might rip Tessa from his arms before they even kiss…

RUN TO YOU is Tessa and Tristan's saga—two books about psychic gifts, secret lives and dangerous loves. Each book is told in three parts: a total of six shattering reads that will stay with you long after the last page.

Grab FIRST SIGHT now for

free, then join Harlequin Teen and a whole bunch of book bloggers and fans at the

RUN TO YOU read-along. It's not too late to join in the FIRST SIGHT and SECOND GLANCE discussions, and we're starting the THIRD CHARM week on Monday, August 3. We’re having a great time, and we have some fun prizes to give away. Get more details on my blog:

http://bit.ly/readR2Y. I’d love to see the Adventures in YA Publishing gang at the read-along!

Find RUN TO YOU at your favorite e-tailers, including:

I turned in my draft of the sequel to Compulsion a couple of weeks ago, and we finally have a name for the book.

Are you ready?

Persuasion

What do you think? I loooooove it.

And I have an AMAZINGLY gorgeous cover design by the fabulous Regina Flath. I think it's even better than Compulsion's cover, and I can't wait to share it with you.

While I'm waiting for my editorial letter from my lovely editor, Sara Sargent, I'm going through the manuscript and making notes for myself. Most of that involves checking to make sure I've done everything I can structure-wise, because we're not at the stage of worrying about words quite yet.

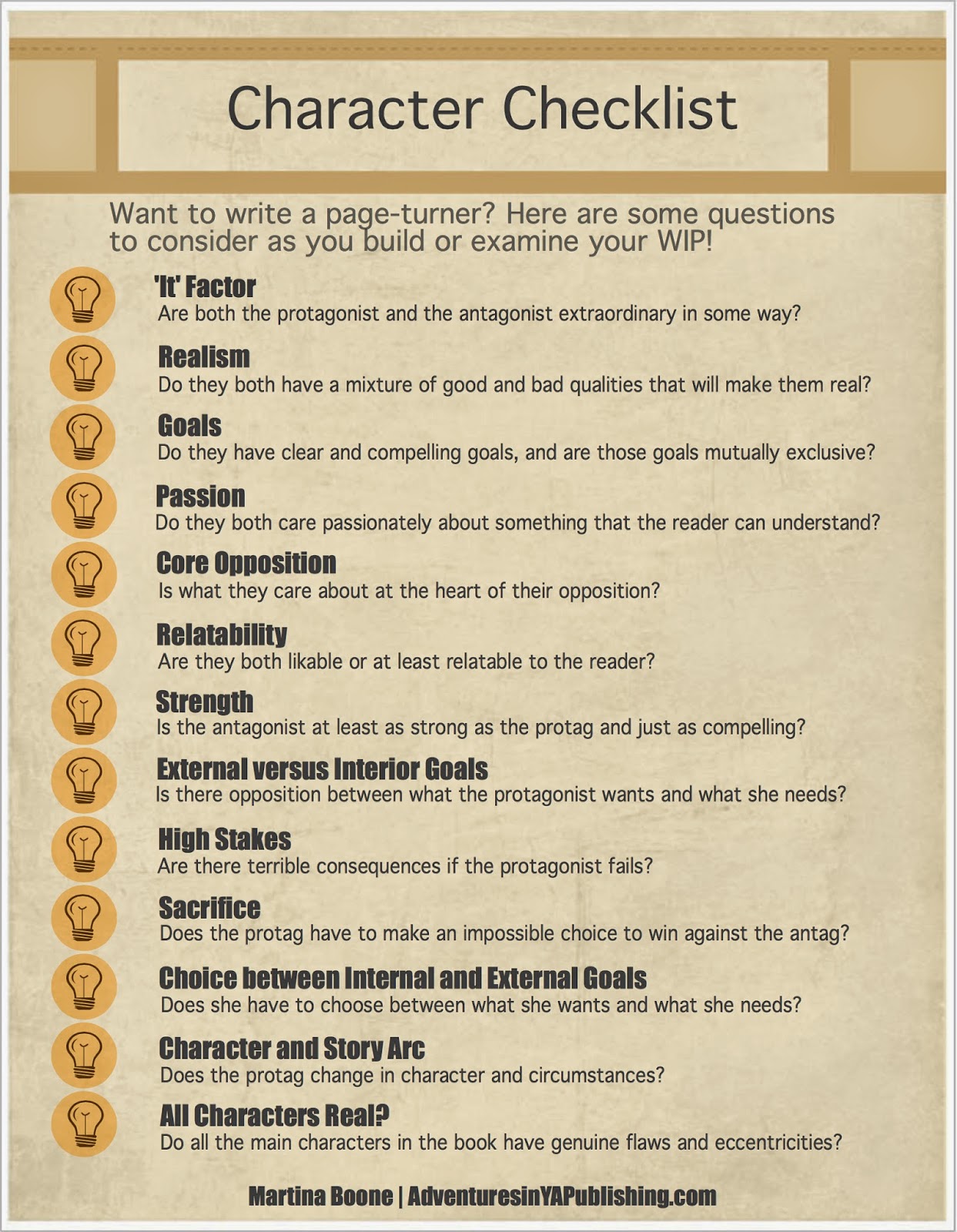

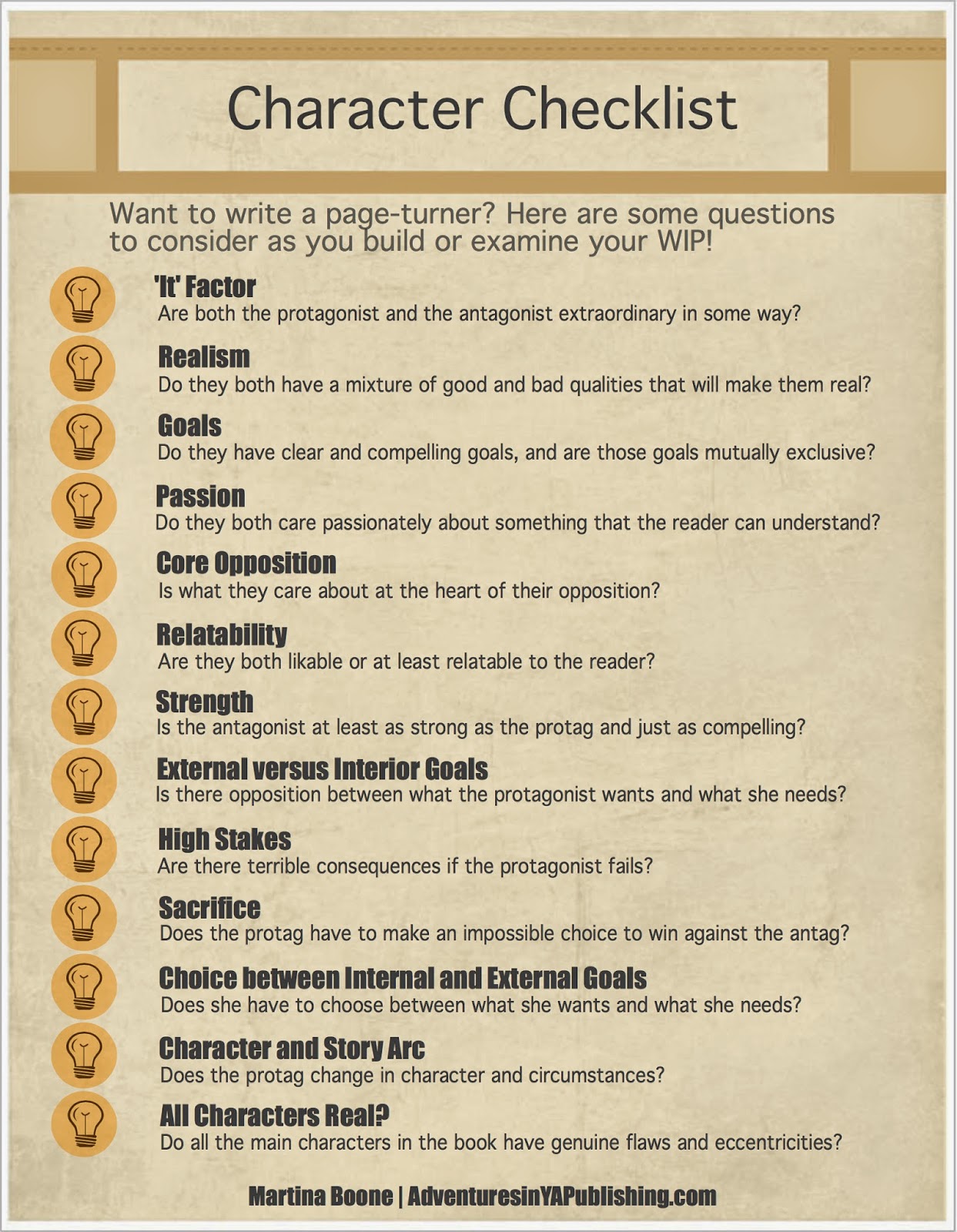

For me, thinking about structure begins with character. I'm asking myself some tough questions, and I thought I'd share them with you as an info graphic:

CHARACTER CHECKLIST INFOGRAPHIC

|

| Character Checklist Infographic by Martina Boone (@MartinaABoone) |

YA GIVEAWAY THIS WEEK

Hexedby Michelle KrysHardcoverDelacorte PressReleased 6/10/2014

Hexedby Michelle KrysHardcoverDelacorte PressReleased 6/10/2014If high school is all about social status, Indigo Blackwood has it made. Sure, her quirky mom owns an occult shop, and a nerd just won’t stop trying to be her friend, but Indie is a popular cheerleader with a football-star boyfriend and a social circle powerful enough to ruin everyone at school. Who wouldn’t want to be her?

Then a guy dies right before her eyes. And the dusty old family Bible her mom is freakishly possessive of is stolen. But it’s when a frustratingly sexy stranger named Bishop enters Indie’s world that she learns her destiny involves a lot more than pom-poms and parties. If she doesn’t get the Bible back, every witch on the planet will die. And that’s seriously bad news for Indie, because according to Bishop, she’s a witch too.

Suddenly forced into a centuries-old war between witches and sorcerers, Indie’s about to uncover the many dark truths about her life—and a future unlike any she ever imagined on top of the cheer pyramid.

Author Question: What is your favorite thing about Hexed?

I love the humor. Indie’s sarcastic commentary and Bishop’s cheeky banter adds some levity to the novel that breaks up some of the heavier, darker paranormal elements of the book.

Purchase Hexed at AmazonPurchase Hexed at IndieBoundView Hexed on GoodreadsFill out the Rafflecopter to win, and don't forget to check the sidebar for more great giveaways!

That's it for me this week! What's going on with you? Read anything good? Are you managing to get any writing done this summer?

Happy reading and writing, everyone!

Martina

a Rafflecopter giveaway

By:

Angela Ackerman,

on 6/11/2014

Blog:

The Bookshelf Muse

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Uncategorized,

Editing,

lessons,

Characters,

Writing Craft,

Experiments,

story structure,

fear,

writing resource,

plotting,

Emotion,

Flaws,

Emotion Thesaurus Guide,

Character wound,

Add a tag

I recently read a Huff Post psychology piece on Turning Negative Emotions Into Your Greatest Advantage and immediately saw how this could also apply to our characters. Feel free to follow the link and read, but if you’re short on time, the rundown is this: negative emotions are not all bad. In fact, they are necessary to the human experience, and can spark a shift that leads to self growth.

And after reading James Scott Bell’s Write Your Novel From The Middle: A New Approach for Plotters, Pantsers and Everyone in Between and attending a full day workshop with him a few weeks ago, I can also see how this idea of using negative emotions to fuel a positive changes fits oh-so-nicely with Jim’s concept of “the Mirror Moment.”

and attending a full day workshop with him a few weeks ago, I can also see how this idea of using negative emotions to fuel a positive changes fits oh-so-nicely with Jim’s concept of “the Mirror Moment.”

But I’m getting ahead of myself. First, let’s look at what a mirror moment is.

Mirror Moment: a moment in midpoint scene of a novel or screenplay when the character is forced to look within and reflect on who he is and who he must become in order to achieve his goal. If he decides to continue on as he always has, he will surely fail (tragedy).

Mirror Moment: a moment in midpoint scene of a novel or screenplay when the character is forced to look within and reflect on who he is and who he must become in order to achieve his goal. If he decides to continue on as he always has, he will surely fail (tragedy).

If the story is not a tragedy, the hero realizes he must either a) become stronger to overcome the odds or b) transform, shedding his biggest flaws and become more open-minded to new ideas and beliefs. One way or the other, he must better himself in some way to step onto the path which will lead to success.

Jim actually describes the Mirror Moment so much better than I can HERE, but do your writing a BIG FAVOR and also snag a copy of this book. (It’s a short read and will absolutely help you strengthen the character’s arc in your story!)

To see how the two tie together, let’s explore what leads to this essential “mirror moment.” Your hero is taking stock of his situation, realizing he has two choices: stubbornly continue on unchanged and hope for the best, or move forward differently, becoming something more.

The big question: what is the catalyst? What causes him to take stock of the situation? What causes his self-reflection?

The answer is not surprising: EMOTION. Something the character FEELS causes him to stop, look within, and make a choice.

Let’s assume this isn’t a tragedy. If this moment had a math formula, it would look something like this:

Emotion + look within = change

So what type of emotions are the best fit to encourage this necessary shift toward change? And are they positive emotions, or negative ones? Let’s experiment!

Common positive emotions, taken right from The Emotion Thesaurus:

Happiness + look within

Happiness is contentment, a feeling of extreme well being. If one feels good about themselves and where they are at, it doesn’t encourage a strong desire for change, does it?

Gratitude + a look within

Gratitude is thankfulness, an appreciation for others and what one has. Because again, gratitude creates contentment, feeling “full” and thankful, it doesn’t make the best catalyst for change. However, if you were to pair it with something like relief (such as being given a second chance), then gratitude over being spared something negative could lead to resolving to change.

Gratitude is thankfulness, an appreciation for others and what one has. Because again, gratitude creates contentment, feeling “full” and thankful, it doesn’t make the best catalyst for change. However, if you were to pair it with something like relief (such as being given a second chance), then gratitude over being spared something negative could lead to resolving to change.

Excitement + a look within

Excitement is the feeling of being energized to the point one feels compelled to act. On the outside, this looks like a good candidate for change, but it depends on the type of excitement. Is the “high” a character feels something that distracts them from self reflection (such as being caught up in the experience of a rock concert) or does it inspire (such as the thrill of meeting one’s sports hero in person)? If one’s excitement propels one to want to become something better, then change can be achieved.

Satisfaction + a look within

Satisfaction is a feeling of contentment in a nutshell. It is feeling whole and complete. As such, looking within while satisfied likely won’t lead to a desire to change anything–in fact it might do just the opposite: encourage the character to remain the same.

Common negative emotions, again right from The Emotion Thesaurus:

Fear + a look within

Fear is the expectation of threat or danger. Feeling afraid is very uncomfortable, something almost all people wish to avoid. Some even try to make deals with the powers that be, so deep is their desperation: if I win this hand, I’ll give up gambling, I swear. So, combining this emotion with some self reflection could definitely create the desire to change.

Frustration + a look within

Feeling stymied or hemmed in is something all people are familiar with and few can tolerate for long. By its very nature, frustration sends the brain on a search for change: how can I fix this? How can I become better/more skilled/adapt? How can I succeed?

Feeling stymied or hemmed in is something all people are familiar with and few can tolerate for long. By its very nature, frustration sends the brain on a search for change: how can I fix this? How can I become better/more skilled/adapt? How can I succeed?

Characters who are frustrated are eager to look within for answers.

Embarrassment + a look within

Embarrassment is another emotion that is very adept at making characters uncomfortable. Self-conscious discomfort is something all usually avoid because it triggers vulnerability. When one feels embarrassed, it is easy to look within and feel the desire to make a change so this experience is not repeated.

Shame + a look within

Disgrace isn’t pretty. When a person knows they have done something improper or dishonorable, it hurts. Shame creates the desire to rewind the clock so one can make a different choice or decision that does not lead to this same situation. It allows the character to focus on their shortcomings without rose-colored glasses, and fast tracks a deep need for change.

* ~ * ~ *

These are only a sampling of emotions, but the exercise above suggests it might be easier to bring about this mirror moment through negative emotions. But, does this mean all positive emotions don’t lead to change while all negative ones do? Not at all!

Love + a look within could create a desire to become more worthy in the eyes of loved ones. And emotions such as Denial or Contempt, while negative, both resist the idea of change. Denial + a look within, simply because one is not yet in a place where they can see truth. Contempt + a look within, because one is focused on the faults of others, not on one’s own possible shortcomings. Overall however, negative emotions seem to be the ones best suited to lead to that mirror moment and epiphany that one must change or become stronger and more skilled in order to succeed.

So there you have it–when you’re working on this critical moment in your story when your character realizes change is needed, think carefully about which emotion might best lead to this necessary internal reflection and change.

So there you have it–when you’re working on this critical moment in your story when your character realizes change is needed, think carefully about which emotion might best lead to this necessary internal reflection and change.

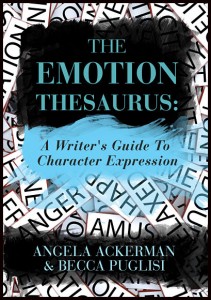

(And of course, we profile 75 emotions in The Emotion Thesaurus: a Writer’s Guide to Character Expression, so that’s just one more way for you to use it!)

The post Story Midpoint & Mirror Moment: Using Heroes’ Emotions To Transform Them appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.

I like to look for treasures on YouTube.

It's a bit like looking for treasures at the dump. The amount of junk one must sort through is appalling. Thank heaven for decent search engines.

I want to share with you now some of my favorite YouTube goodies that I found in the last month.

1. Howard Tayler on 'Who Needs Talent?'

This is only the first part. But watch all four parts. It completely changed the way I think about writing, 'talent', and what I have potential to do.

2. Dan Wells on 'Seven Point Story Structure'.

This is an AWESOME seminar that helped me a lot. I'm a budding outliner (I used to think I was a freewriter, but I think I'm changing with age) and having only ever freewritten my entire life, I was lost as to how to begin. This helped me through. First of five parts.

3. The Definition of Steampunk

Brilliant. Just brilliant.

4. World's Fastest Gun Disarm

Because maybe one of your characters needs to be able to do this. There are tutorials, but I'm fairly certain most of us can't be as fast as this dude.

Speaking of gun tutorials: do you have a character who needs to know how to intelligently use a firearm?

5. This guy has a channel with, like, 900 videos on how to shoot a gun, for newbies. He's got stuff from the difference between smoky and smokeless powder, to reasons why not to put your thumb behind the slide on a semi-automatic... which is what the next video is about. If you want details,

this guy will give you details.

Hope something in this grab bag of a post was useful to you! Tell me about it in the comments, if you did.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/8/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Novel Structure,

Three Act Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Plots,

Alternative Structures,

Designing Principle,

Classical Design,

Add a tag

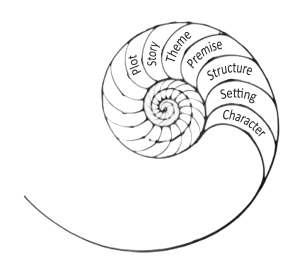

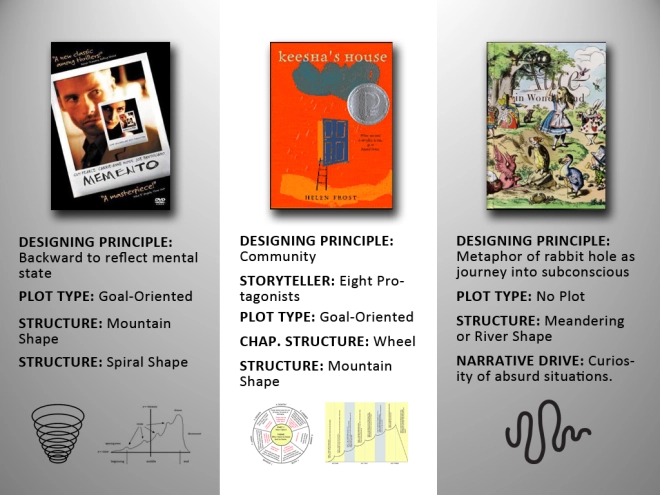

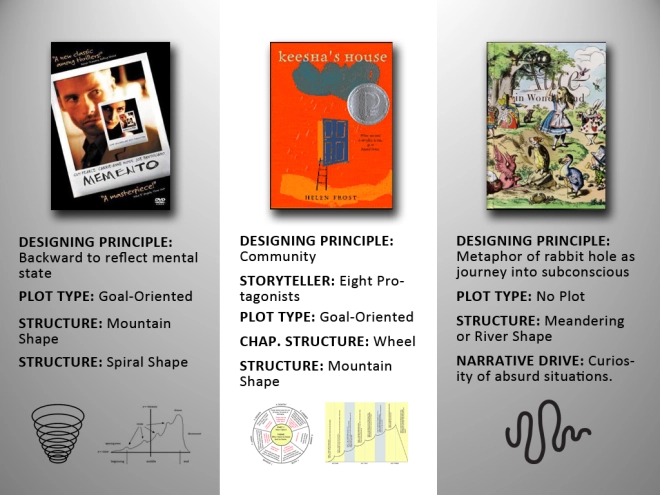

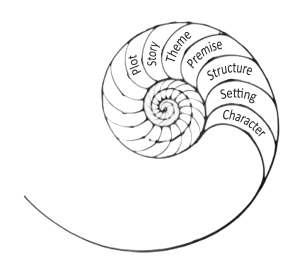

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

Happy plotting, structuring, and designing, everyone!

Organic Architecture Series:

Classic Design and Arch Plot:

Alternative Plots:

Alternative Structures:

Designing Principle:

Full Bibliography for this Series:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Anderson, Tobin. “Theories of Plot and Narrative.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt Inc., 1927.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Hawes, Louise. “Desire Is the Cause of All Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Kaufman, Charlie. “Charlie Kaufman: BAFTA Screenwriting Lecture Transcript.” BAFTA Guru. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 30 Sept. 2011. Web. 18 Aug. 2012.

Larios, Julie. “Once or Twice Upon a Time or Two: Thoughts on Revisionist Fairy Tales.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Layne, Ron and Rick Lewis. “Plot, Theme, the Narrative Arc, and Narrative Patterns.” English and Humanities Department. Sandhill Community College. 11 Sept, 2009. Web. 7 May 2011.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007. McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Sibson, Laura. “Structure Serving Story: A Discussion of Alternating Narrators in Today’s Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Tobias, Ron. Twenty Master Plots: And How to Build Them. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1993.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/8/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Novel Structure,

Three Act Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Plots,

Alternative Structures,

Designing Principle,

Classical Design,

Add a tag

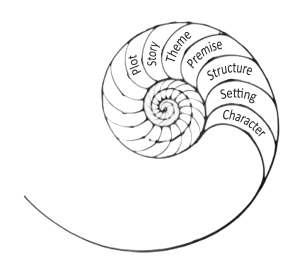

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

Happy plotting, structuring, and designing, everyone!

Organic Architecture Series:

Classic Design and Arch Plot:

Alternative Plots:

Alternative Structures:

Designing Principle:

Full Bibliography for this Series:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Anderson, Tobin. “Theories of Plot and Narrative.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.