new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Plot Structure, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 18 of 18

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Plot Structure in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

My current work-in-progress (work-in-stasis might be a more accurate description) contains an important plot twist, which I’m hoping will catch people by surprise. Don’t ask me, I’m not telling; but it’s got me thinking about plot twists and their evil counterparts, spoilers.

The thing is, while part of me is rubbing my hands with delight at the thought of my twist and the effect it will have my hapless readers, another part is sniffily pointing out that plot twists are cheap tricks, and that a book that relies too heavily on them may be enjoyed once for its shock value, but will never be read twice. All the same, as a reader I enjoy a good plot twist myself, so I would like to arbitrate if I can and achieve a compromise acceptable to both parties.

Let’s start with definitions. All stories contain events, but at what point does a turn of events become a twist? A twist must of course be unexpected, but can we say more than that? One way of thinking about it – a circular one, admittedly, but we’re entering the twisted realm of the Möbius strip here anyway – is to say that a plot twist is an event that, if it were revealed ahead of time, would count as a spoiler. This of course raises the twin question: what is a spoiler? Telling a little about a book’s plot in advance needn't involve spoiling; indeed, it's the very essence of jacket blurbs, which are designed to entice readers into wanting more, not to ruin their enjoyment. At what point does an amuse bouchecease to enhance the appetite and begin to spoil it?

Do spoilers have a sell-by date?

Position within the plot is one relevant factor. A plot twist that comes early enough – say, the revelation that your uncle has murdered your father by pouring poison in his ear – can be very effective, but if it appears near the beginning of the story it merges into exposition. Probably no one would consider themselves “spoiled” by learning this fact about Hamlet, because the play centres on the consequences that flow from the revelation, not on the murder itself. At the other extreme, a plot twist that appears right at the end of a book can seem gimmicky, and successful examples are scarce outside specialized genres such as the detective story. Gene Kemp’s The Turbulent Term of Tyke Tiler (1977) is a rare exception. In general the ideal place for a really fundamental plot twist is the middle third of a story. That gives you time to weave the rug you’re going to pull out from under your readers’ feet, and also time to justify your action in what follows. Frances Hardinge’s excellent new book, Cuckoo Song (2014), is the most recent example of this kind that I have read.

Plot twists are a kind of trick played on the reader, who is led to expect or believe one thing but is then surprised by a reality that is very different. Like all practical jokes spoilers need to have some kind of point to be justified. That sea cook you’ve grown so fond of? He's really the leader of the pirates! But now you’ve let yourself become emotionally involved, and will remain so.

Twists can happen at the level of genre as well as of plot. As my friends will wearily testify, over the last couple of months I have become rather obsessed with a Japanese anime series bearing the ungainly title

Puella Magia Madoka Magica. Before it was broadcast in Japan in 2011, the series was given

this trailer, which promised a cute (not to say saccharine) story about young girls with magical powers and adorable animal friends – something also implied by the cover of the DVD. Even the first couple of episodes don’t deviate wildly from this expectation. However, at a certain point it is rather as if you have settled down with

Winnie-the-Poohand encountered this scene:

In fact, Puella Magia Madoka Magica is a tragic drama, and one of the most brutal and emotionally hard-hitting series you could wish to see. It has several very effective conventional plot twists, but perhaps the greatest is its genre twist: it looks like one kind of story (both to the viewer and, importantly, to the characters), and turns out to be quite another. As I’ve discovered, however, persuading people to watch something that looks like Madoka without spoiling the nature of the series for them can be an uphill task. And now I’ve also spoiled it for you, dear reader.

Or have I? The strange thing about spoilers is that not all of them spoil. When Sophocles wrote Oedipus Rex he was telling a story with a terrific plot twist: the hero turns out to have unwittingly killed his father and married his mother. Yet his audience were well aware of this before watching the play – those ancient Greeks knew their ancient Greek mythology, after all - and it doesn’t appear to have dimmed their enjoyment or that of subsequent generations. The easy explanation is that the play gives us much more than plot twists, and we are richly compensated in the currency of great poetry for our lack of shock. But that’s not quite right, because even when you know what Oedipus is going to discover, it’s still shocking. It’s shocking because he doesn’t know, and we feel with and for him. That is why, even when they have been “spoiled”, the great works, from Oedipus Rex to Puella Magia Madoka Magica, bear repeated readings and viewings.

Probably I should worry less about twists and spoilers, and just try to write the best book I can. If it’s good enough, it will survive whatever spoiling comes its way. Literature, as Ezra Pound, put it, is news that stays news. Or, to paraphrase Professor Kirke: “It’s all in Aristotle. Bless me, what do they teach them in these schools?”

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/8/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Novel Structure,

Three Act Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Plots,

Alternative Structures,

Designing Principle,

Classical Design,

Add a tag

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

Happy plotting, structuring, and designing, everyone!

Organic Architecture Series:

Classic Design and Arch Plot:

Alternative Plots:

Alternative Structures:

Designing Principle:

Full Bibliography for this Series:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Anderson, Tobin. “Theories of Plot and Narrative.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt Inc., 1927.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Hawes, Louise. “Desire Is the Cause of All Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Kaufman, Charlie. “Charlie Kaufman: BAFTA Screenwriting Lecture Transcript.” BAFTA Guru. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 30 Sept. 2011. Web. 18 Aug. 2012.

Larios, Julie. “Once or Twice Upon a Time or Two: Thoughts on Revisionist Fairy Tales.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Layne, Ron and Rick Lewis. “Plot, Theme, the Narrative Arc, and Narrative Patterns.” English and Humanities Department. Sandhill Community College. 11 Sept, 2009. Web. 7 May 2011.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007. McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Sibson, Laura. “Structure Serving Story: A Discussion of Alternating Narrators in Today’s Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Tobias, Ron. Twenty Master Plots: And How to Build Them. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1993.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/8/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Novel Structure,

Three Act Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Plots,

Alternative Structures,

Designing Principle,

Classical Design,

Add a tag

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

Happy plotting, structuring, and designing, everyone!

Organic Architecture Series:

Classic Design and Arch Plot:

Alternative Plots:

Alternative Structures:

Designing Principle:

Full Bibliography for this Series:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Anderson, Tobin. “Theories of Plot and Narrative.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt Inc., 1927.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Hawes, Louise. “Desire Is the Cause of All Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Kaufman, Charlie. “Charlie Kaufman: BAFTA Screenwriting Lecture Transcript.” BAFTA Guru. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 30 Sept. 2011. Web. 18 Aug. 2012.

Larios, Julie. “Once or Twice Upon a Time or Two: Thoughts on Revisionist Fairy Tales.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Layne, Ron and Rick Lewis. “Plot, Theme, the Narrative Arc, and Narrative Patterns.” English and Humanities Department. Sandhill Community College. 11 Sept, 2009. Web. 7 May 2011.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007. McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Sibson, Laura. “Structure Serving Story: A Discussion of Alternating Narrators in Today’s Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Tobias, Ron. Twenty Master Plots: And How to Build Them. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1993.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

In my last post we began our survey of alternative story structures. That post covered non-linear structure, episodic structure with an arc, wheel structure, and meandering structure.

Today we’ll continue to push past the traditional story structure idea of a mountain or triangle shape to consider branching structure, spiral structure, multiple POV structure, parallell structure, and cumulative structure!

Again, you could apply these structural ideas to a traditional mountain shape, or let them create their own rhythm and energy.

BRANCHING STRUCTURE

This structure consists of “a system of paths that extend from a few central points by splitting and adding smaller and smaller parts … Each branch usually represents a complete society in detail or a detailed stage of the same society that the hero explores” (Truby). This is a popular structure used in non-fiction books.

- Film Examples: It’s a Wonderful Life, Nashville, Traffic.

- Book Examples: Gulliver’s Travels (Swift), Phineus Gage: A Gruesome but True Story about Brain Science (Fleishman).

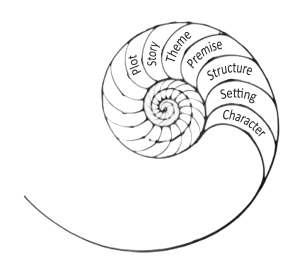

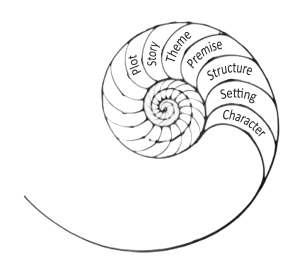

SPIRAL STRUCTURE

Spiral structure “is a path that circles inward to the center…[wherein] a character keeps returning to a single event or memory and explores it at progressively deeper levels” (Truby).

- Film Examples: Vertigo, The Conversation, Memento.

- Book Examples: Before I Fall (Oliver), How to Tell a True War Story (O’Brien).

MULTIPLE POINT-OF-VIEW STRUCTURE

This structure has multiple protagonists and provides the point-of-view (POV) of multiple characters. Variations include one character telling his/her whole story and then another character telling a different version of the story. Another popular style is alternating viewpoints (chapter-by-chapter) as the story progresses. In film, multiple POV can sometimes be accompanied by a split-screen technique.

- Film Examples: He Loves Me…He Loves Me Not, Rules of Attraction, Sliding Doors.

- Book Examples: Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist (Cohn & Levithan), The Scorpio Races (Stiefvater), Jumped (Williams-Garcia), Skud (Foon), Keesha’s House (Frost), Blink & Caution (Wynne-Jones), Tangled (Mackler).

PARALLEL STRUCTURE

(Also known as: Parallel Substitution Structure, Multiple Personality Structure)

This structure has dual or multiple storylines that mirror and reflect each other. Stories can include different protagonists or a single protagonist in different “lives.” Storylines often exist within separate time frames, dimensions, or locations. In the instance of parallel substitution structure, actual events in a protagonist’s storyline are substituted with thematic stories such as fables, religious stories, myth, or a parallel thematic scene. The reader is meant to make the thematic and causal connections through the substitution. In the case of multiple personality structure, “multiple protagonists are the same person, or different versions of the same person” (Berg). Multiple personality structure can also be considered a variant of multiple POV or branching structure.

- Film Examples: The Fountain, Sliding Doors, Identity, Fight Club.

- Book Examples: The Powerbook (Winterson), Habibi (Thompson), American Born Chinese (Yang), Revolution (Donnelly).

CUMULATIVE STRUCTURE

This structure is most often used in picture books and songs. It builds a story through a “repetitive pattern or text structure: each page repeats the text from the previous page, adding a new line/plot element. As the details pile up, the tale builds to a climax” (Carver).

- Book Examples: There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly (Mills), This is the House that Jack Built (Mother Goose).

Do you know of any other alternative story structures? I’d love to hear all about them!

Up next: Designing principals and how to make decisions on what the best plot type and story structure is best for your project!

Works Cited:

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

In my last post we began our survey of alternative story structures. That post covered non-linear structure, episodic structure with an arc, wheel structure, and meandering structure.

Today we’ll continue to push past the traditional story structure idea of a mountain or triangle shape to consider branching structure, spiral structure, multiple POV structure, parallell structure, and cumulative structure!

Again, you could apply these structural ideas to a traditional mountain shape, or let them create their own rhythm and energy.

BRANCHING STRUCTURE

This structure consists of “a system of paths that extend from a few central points by splitting and adding smaller and smaller parts … Each branch usually represents a complete society in detail or a detailed stage of the same society that the hero explores” (Truby). This is a popular structure used in non-fiction books.

- Film Examples: It’s a Wonderful Life, Nashville, Traffic.

- Book Examples: Gulliver’s Travels (Swift), Phineus Gage: A Gruesome but True Story about Brain Science (Fleishman).

SPIRAL STRUCTURE

Spiral structure “is a path that circles inward to the center…[wherein] a character keeps returning to a single event or memory and explores it at progressively deeper levels” (Truby).

- Film Examples: Vertigo, The Conversation, Memento.

- Book Examples: Before I Fall (Oliver), How to Tell a True War Story (O’Brien).

MULTIPLE POINT-OF-VIEW STRUCTURE

This structure has multiple protagonists and provides the point-of-view (POV) of multiple characters. Variations include one character telling his/her whole story and then another character telling a different version of the story. Another popular style is alternating viewpoints (chapter-by-chapter) as the story progresses. In film, multiple POV can sometimes be accompanied by a split-screen technique.

- Film Examples: He Loves Me…He Loves Me Not, Rules of Attraction, Sliding Doors.

- Book Examples: Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist (Cohn & Levithan), The Scorpio Races (Stiefvater), Jumped (Williams-Garcia), Skud (Foon), Keesha’s House (Frost), Blink & Caution (Wynne-Jones), Tangled (Mackler).

PARALLEL STRUCTURE

(Also known as: Parallel Substitution Structure, Multiple Personality Structure)

This structure has dual or multiple storylines that mirror and reflect each other. Stories can include different protagonists or a single protagonist in different “lives.” Storylines often exist within separate time frames, dimensions, or locations. In the instance of parallel substitution structure, actual events in a protagonist’s storyline are substituted with thematic stories such as fables, religious stories, myth, or a parallel thematic scene. The reader is meant to make the thematic and causal connections through the substitution. In the case of multiple personality structure, “multiple protagonists are the same person, or different versions of the same person” (Berg). Multiple personality structure can also be considered a variant of multiple POV or branching structure.

- Film Examples: The Fountain, Sliding Doors, Identity, Fight Club.

- Book Examples: The Powerbook (Winterson), Habibi (Thompson), American Born Chinese (Yang), Revolution (Donnelly).

CUMULATIVE STRUCTURE

This structure is most often used in picture books and songs. It builds a story through a “repetitive pattern or text structure: each page repeats the text from the previous page, adding a new line/plot element. As the details pile up, the tale builds to a climax” (Carver).

- Book Examples: There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly (Mills), This is the House that Jack Built (Mother Goose).

Do you know of any other alternative story structures? I’d love to hear all about them!

Up next: Designing principals and how to make decisions on what the best plot type and story structure is best for your project!

Works Cited:

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

I’ve spent a lot of time in this organic architecture series talking about plot plot plot plot. (If you’ve missed those post please check out: arch plot, alternative plots, and plot genres). But it’s time to switch gears and think about organization, rhythm, and energy.

I’ve spent a lot of time in this organic architecture series talking about plot plot plot plot. (If you’ve missed those post please check out: arch plot, alternative plots, and plot genres). But it’s time to switch gears and think about organization, rhythm, and energy.

That’s right let’s talk structure! (Which, if you don’t remember I’m obsessed with. Yes, I said obsessed).

Traditionally, we’re used to thinking about structure as a mountain or triangle with an escalating tension. But I want to break out of the triangle/mountain box and think about structure in a new way. The following ideas can be applied to a mountain structure (if you want), or they can provide a whole new guideline for rhythm and tension!

Alternative structures all be discussing include:

- Non-linear structure

- Episodic structure with an arc

- Wheel structure

- Meandering structure

- Branching structure

- Spiral structure

- Multiple point-of-view structure

- Parallel structure

- Cumulative structure

Let’s dig right in!

NON-LINEAR STRUCTURE

(Also known as: Backwards Structure, Scrambled Sequence Structure)

Non-linear structure tells events out of linear order for dramatic impact. The juxtaposition of out-of-order scenes and sequences can help the reader to create plot connections, expand character depth, or elaborate on theme. Backwards structures draw attention to causal connections, like forward-moving linear structures, but become causal mysteries, where the narrative fuel is the search for the first cause of known effects (Berg). Scrambled-sequence structures don’t “do away with the cause-and-effect chain, [they] merely suspend it for a time, eventually to be ordered by the competent spectator” (Berg). Additionally, a story with a flashback can be considered part of a non-linear structure. However, some define flashbacks as a character thinking back on an event, and thus exist within a traditional linear-story timeline.

- Film Examples: Memento, Pulp Fiction, The Limey, Out of Sight, Reservoir Dogs.

- Book Examples: Betrayal (Pinter), Habibi (Thompson), The Time Traveler’s Wife (Niffenegger), Beneath a Meth Moon (Woodson).

EPISODIC STRUCTURE WITH AN ARC

(Also known as: Television Structure, Book Series Structure)

“Episodic structure is a series of chapters or stories linked together by the same character place or theme, but also held apart by their own goals, plots, or purpose” (Schmidt). A larger multiple book or episode character-arc or plot-goal often ties together a series, as done in television and comic books.

- Film Examples: Friday Night Lights, Mad Men, Friends, Dr. Who, Game of Thrones, Battlestar Galactica, Vampire Diaries, Gossip Girl, etc.

- Singular Book Examples: The Graveyard Book (Gaiman), The New York Singles Mormon Halloween Dance (Baker), The Strange Case of Origami Yoda (Angleberger).

- Series Book Examples: The Adventures of Tintin (Herge), Sin City (Miller), Knuffle Bunny (Willems), Hunger Games (Collins).

WHEEL STRUCTURE

(Also known as: The Short Story Cycle, Hub and Spoke Structure)

In wheel structure, scenes, stories, vignettes, and poems, all revolve around a thematic center where the “hub [is] a compelling emotional event, and the narration refer[s] to this event like the spokes.” (Campbell). Additionally, “the rim of the wheel represents recurrent elements in a cycle … [and] as these elements repeat themselves, turn in on themselves, and recur, the whole wheel moves forward” (Kalmar). Many novels in verse or vignettes use this structure.

- Film Examples: Waking Life, Loss of Sexual Innocence, Chungking Express, The Tree of Life.

- Book Examples: The chapter structure of Keesha’s House (Frost), Einstein’s Dreams (Lightman), The House on Mango Street (Cisneros), Tales from Outer Suburbia (Tan).

MEANDERING STRUCTURE

(Also known as: River Structure, Winding Path Structure)

Meandering structure is a “story that follows a winding path without apparent direction” (Truby). The hero may or may not have a desire. If the hero has a desire it is not intense, and “he covers a great deal of territory in a haphazard way; and he encounters a number of characters from different levels of society” (Truby).

- Film Examples: Forrest Gump.

- Book Examples: Alice in Wonderland (Carroll), Huck Finn (Twain), Don Quixote (Cervantes).

In my next post we’ll take a look at:

- Branching structure

- Spiral structure

- Multiple point-of-view structure

- Parallel structure

- Cumulative structure

Works Cited:

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Tax-onomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

I’ve spent a lot of time in this organic architecture series talking about plot plot plot plot. (If you’ve missed those post please check out: arch plot, alternative plots, and plot genres). But it’s time to switch gears and think about organization, rhythm, and energy.

I’ve spent a lot of time in this organic architecture series talking about plot plot plot plot. (If you’ve missed those post please check out: arch plot, alternative plots, and plot genres). But it’s time to switch gears and think about organization, rhythm, and energy.

That’s right let’s talk structure! (Which, if you don’t remember I’m obsessed with. Yes, I said obsessed).

Traditionally, we’re used to thinking about structure as a mountain or triangle with an escalating tension. But I want to break out of the triangle/mountain box and think about structure in a new way. The following ideas can be applied to a mountain structure (if you want), or they can provide a whole new guideline for rhythm and tension!

Alternative structures all be discussing include:

- Non-linear structure

- Episodic structure with an arc

- Wheel structure

- Meandering structure

- Branching structure

- Spiral structure

- Multiple point-of-view structure

- Parallel structure

- Cumulative structure

Let’s dig right in!

NON-LINEAR STRUCTURE

(Also known as: Backwards Structure, Scrambled Sequence Structure)

Non-linear structure tells events out of linear order for dramatic impact. The juxtaposition of out-of-order scenes and sequences can help the reader to create plot connections, expand character depth, or elaborate on theme. Backwards structures draw attention to causal connections, like forward-moving linear structures, but become causal mysteries, where the narrative fuel is the search for the first cause of known effects (Berg). Scrambled-sequence structures don’t “do away with the cause-and-effect chain, [they] merely suspend it for a time, eventually to be ordered by the competent spectator” (Berg). Additionally, a story with a flashback can be considered part of a non-linear structure. However, some define flashbacks as a character thinking back on an event, and thus exist within a traditional linear-story timeline.

- Film Examples: Memento, Pulp Fiction, The Limey, Out of Sight, Reservoir Dogs.

- Book Examples: Betrayal (Pinter), Habibi (Thompson), The Time Traveler’s Wife (Niffenegger), Beneath a Meth Moon (Woodson).

EPISODIC STRUCTURE WITH AN ARC

(Also known as: Television Structure, Book Series Structure)

“Episodic structure is a series of chapters or stories linked together by the same character place or theme, but also held apart by their own goals, plots, or purpose” (Schmidt). A larger multiple book or episode character-arc or plot-goal often ties together a series, as done in television and comic books.

- Film Examples: Friday Night Lights, Mad Men, Friends, Dr. Who, Game of Thrones, Battlestar Galactica, Vampire Diaries, Gossip Girl, etc.

- Singular Book Examples: The Graveyard Book (Gaiman), The New York Singles Mormon Halloween Dance (Baker), The Strange Case of Origami Yoda (Angleberger).

- Series Book Examples: The Adventures of Tintin (Herge), Sin City (Miller), Knuffle Bunny (Willems), Hunger Games (Collins).

WHEEL STRUCTURE

(Also known as: The Short Story Cycle, Hub and Spoke Structure)

In wheel structure, scenes, stories, vignettes, and poems, all revolve around a thematic center where the “hub [is] a compelling emotional event, and the narration refer[s] to this event like the spokes.” (Campbell). Additionally, “the rim of the wheel represents recurrent elements in a cycle … [and] as these elements repeat themselves, turn in on themselves, and recur, the whole wheel moves forward” (Kalmar). Many novels in verse or vignettes use this structure.

- Film Examples: Waking Life, Loss of Sexual Innocence, Chungking Express, The Tree of Life.

- Book Examples: The chapter structure of Keesha’s House (Frost), Einstein’s Dreams (Lightman), The House on Mango Street (Cisneros), Tales from Outer Suburbia (Tan).

MEANDERING STRUCTURE

(Also known as: River Structure, Winding Path Structure)

Meandering structure is a “story that follows a winding path without apparent direction” (Truby). The hero may or may not have a desire. If the hero has a desire it is not intense, and “he covers a great deal of territory in a haphazard way; and he encounters a number of characters from different levels of society” (Truby).

- Film Examples: Forrest Gump.

- Book Examples: Alice in Wonderland (Carroll), Huck Finn (Twain), Don Quixote (Cervantes).

In my next post we’ll take a look at:

- Branching structure

- Spiral structure

- Multiple point-of-view structure

- Parallel structure

- Cumulative structure

Works Cited:

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Tax-onomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 6/10/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Classic Design,

Classic Plot Design,

Plot,

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Energic Plot,

Add a tag

Last week I started off my Organic Architecture series by outlining the eleven major story-beats of classical design. Before I jump into alternative structures and plots I want to make sure we understand arch plot as more than just a template for story. I want to show how this story-frame can be used, and used well.

Today I’m going to breakdown the major beats of classical design using Pixar’s film Toy Story. This film is an excellent example of how arch plot can create a satisfying story experience that moves like a well-oiled machine and every piece has a purpose. Let’s take a look at how the eleven steps outlined in my previous post are put into practice.

ACT ONE:

1) Ordinary World

In the first images of Toy Story we’re introduced to Andy and his favorite toy Sheriff Woody (our protagonist). In the first minutes we establish Woody’s ordinary world, consisting of Andy’s room. At minute four, we get the story hook: the toys come to life. At this point we’re introduced to the major players: Mr. Potato Head, Slinky-dog, Bo-Peep, etc. Relationships are hinted at and we see that Woody is the leader of this clan. The complexity of this world deepens when the first obstacle is introduced, allowing us to see how Woody normally functions in the ordinary world. The obstacle is Andy’s birthday party and a covert toy-style mission to see if there are any new, bigger and brighter, toys to be worried about. This action reveals the emotional core of the film: every toy’s deepest fear is that they will be replaced and Andy will no longer love them. In the first twelve minutes the film has set up the world, how it works, and what’s at stake.

2) The Call to Action

At minute fourteen, Buzz Lightyear shows up on screen. Something new has arrived to disrupt the ordinary world. This is what the hero’s journey calls the call to adventure. In Toy Story the call isn’t an invitation to a quest, but it is a catalyst that disrupts Woody’s status quo. Woody tells himself that this new toy isn’t going to change anything and we enter…

3) The Refusal of the Call

This is the debate section where Woody tries to keep his authority, but is slowly usurped by Buzz.

4) Crossing the First Threshold

Woody’s refusal culminates when his flaws of pride and jealousy cause him to pick a fight with Buzz. Both toys fall out of the car and Andy’s family drives away, leaving Woody and Buzz on the pavement. The two have now become LOST TOYS! This is the moment when Woody and Buzz cross the first threshold and move us into act two. This is the point of no return. Woody and Buzz are no longer in the ordinary world but the special world, which will force them to grow. The energy of the story changes here because the two have a new desire: to get home.

ACT TWO:

5) Tests, Allies, and Enemies

The next seventeen minutes of the film constitutes the fun and games section where our heroes are presented with tests, allies, and enemies. When I went to film school we called this the “trailer section.” It’s where all the gags and jokes used in a film trailer come from. This is the section of the story that fulfills the promise of your premise. Toy Story’s premise is: how do two rival toys find their way home when lost in the real world? Well, they hitch a ride to pizza planet. They get chosen by The Claw and taken home by the evil neighbor Sid. They defend themselves against cannibal toys. Each obstacle gets harder and harder. And it leads us to…

6) The Mid-Point

In the hero’s journey there isn’t actually a mid-point, but in screenwriting it has become very important story beat. It’s where the energy of the film swings up, or swings down. In Toy Story it swings down. Buzz comes upon a TV commercial selling Buzz Lightyear action figures and realizes he is not the Buzz Lightyear, but actually a TOY!

7) Approaching the In-Most Cave

The mid-point also affects Woody and propels the story into the next section. Woody continues to put out fires while Buzz has his existential crisis. This is known as approaching the in-most cave or continued obstacles and intensification.

8) The In-Most Cave

At minute 57, Woody hits rock bottom and reaches the in-most cave or crisis of the story. Both Woody and Buzz are trapped, Woody’s friends have abandoned him, and he can now see that his pride has led him astray.

ACT THREE:

9) The Final Push

Just after the crisis usually comes a change in fate. Sid takes Buzz into the backyard to blow him up and Woody realizes he must save the only friend he has left. This propels us into act three and the final push where Woody devises a rescue plan.

10) Seizes the Sword

Woody enacts his plan in the climax and seizes the sword by saving Buzz’s life!

11) The Return Home

But the return home is still wrought with tension as Woody and Buzz chase down the moving van. Some consider this a second final climax (think horror films where monsters you thought were dead jump out at the last minute). Woody grows by putting his pride aside and works together with Buzz to reunite with Andy. As the film closes Buzz and Woody have returned to the new ordinary world with the wisdom and friendship of their adventure.

This is classic design used well! It creates an emotionally engaging and well-paced story. If you like this story design I highly suggest reading Sheryl Scarborough’s guest post that continues this discussion in regards to three-act structure.

However, despite popular belief, classic design is not the only way to tell a story. My next post will outline the hidden agenda of arch plot and why we need more storytelling options!

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 6/10/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

The Hero's Journey,

Energic Plot,

Plot,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Classic Design,

Classic Plot Design,

Writing Craft,

Add a tag

Last week I started off my Organic Architecture series by outlining the eleven major story-beats of classical design. Before I jump into alternative structures and plots I want to make sure we understand arch plot as more than just a template for story. I want to show how this story-frame can be used, and used well.

Today I’m going to breakdown the major beats of classical design using Pixar’s film Toy Story. This film is an excellent example of how arch plot can create a satisfying story experience that moves like a well-oiled machine and every piece has a purpose. Let’s take a look at how the eleven steps outlined in my previous post are put into practice.

ACT ONE:

1) Ordinary World

In the first images of Toy Story we’re introduced to Andy and his favorite toy Sheriff Woody (our protagonist). In the first minutes we establish Woody’s ordinary world, consisting of Andy’s room. At minute four, we get the story hook: the toys come to life. At this point we’re introduced to the major players: Mr. Potato Head, Slinky-dog, Bo-Peep, etc. Relationships are hinted at and we see that Woody is the leader of this clan. The complexity of this world deepens when the first obstacle is introduced, allowing us to see how Woody normally functions in the ordinary world. The obstacle is Andy’s birthday party and a covert toy-style mission to see if there are any new, bigger and brighter, toys to be worried about. This action reveals the emotional core of the film: every toy’s deepest fear is that they will be replaced and Andy will no longer love them. In the first twelve minutes the film has set up the world, how it works, and what’s at stake.

2) The Call to Action

At minute fourteen, Buzz Lightyear shows up on screen. Something new has arrived to disrupt the ordinary world. This is what the hero’s journey calls the call to adventure. In Toy Story the call isn’t an invitation to a quest, but it is a catalyst that disrupts Woody’s status quo. Woody tells himself that this new toy isn’t going to change anything and we enter…

3) The Refusal of the Call

This is the debate section where Woody tries to keep his authority, but is slowly usurped by Buzz.

4) Crossing the First Threshold

Woody’s refusal culminates when his flaws of pride and jealousy cause him to pick a fight with Buzz. Both toys fall out of the car and Andy’s family drives away, leaving Woody and Buzz on the pavement. The two have now become LOST TOYS! This is the moment when Woody and Buzz cross the first threshold and move us into act two. This is the point of no return. Woody and Buzz are no longer in the ordinary world but the special world, which will force them to grow. The energy of the story changes here because the two have a new desire: to get home.

ACT TWO:

5) Tests, Allies, and Enemies

The next seventeen minutes of the film constitutes the fun and games section where our heroes are presented with tests, allies, and enemies. When I went to film school we called this the “trailer section.” It’s where all the gags and jokes used in a film trailer come from. This is the section of the story that fulfills the promise of your premise. Toy Story’s premise is: how do two rival toys find their way home when lost in the real world? Well, they hitch a ride to pizza planet. They get chosen by The Claw and taken home by the evil neighbor Sid. They defend themselves against cannibal toys. Each obstacle gets harder and harder. And it leads us to…

6) The Mid-Point

In the hero’s journey there isn’t actually a mid-point, but in screenwriting it has become very important story beat. It’s where the energy of the film swings up, or swings down. In Toy Story it swings down. Buzz comes upon a TV commercial selling Buzz Lightyear action figures and realizes he is not the Buzz Lightyear, but actually a TOY!

7) Approaching the In-Most Cave

The mid-point also affects Woody and propels the story into the next section. Woody continues to put out fires while Buzz has his existential crisis. This is known as approaching the in-most cave or continued obstacles and intensification.

8) The In-Most Cave

At minute 57, Woody hits rock bottom and reaches the in-most cave or crisis of the story. Both Woody and Buzz are trapped, Woody’s friends have abandoned him, and he can now see that his pride has led him astray.

ACT THREE:

9) The Final Push

Just after the crisis usually comes a change in fate. Sid takes Buzz into the backyard to blow him up and Woody realizes he must save the only friend he has left. This propels us into act three and the final push where Woody devises a rescue plan.

10) Seizes the Sword

Woody enacts his plan in the climax and seizes the sword by saving Buzz’s life!

11) The Return Home

But the return home is still wrought with tension as Woody and Buzz chase down the moving van. Some consider this a second final climax (think horror films where monsters you thought were dead jump out at the last minute). Woody grows by putting his pride aside and works together with Buzz to reunite with Andy. As the film closes Buzz and Woody have returned to the new ordinary world with the wisdom and friendship of their adventure.

This is classic design used well! It creates an emotionally engaging and well-paced story. If you like this story design I highly suggest reading Sheryl Scarborough’s guest post that continues this discussion in regards to three-act structure.

However, despite popular belief, classic design is not the only way to tell a story. My next post will outline the hidden agenda of arch plot and why we need more storytelling options!

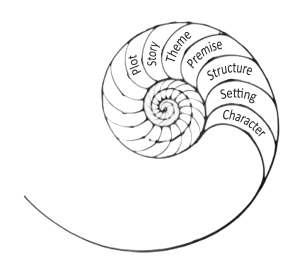

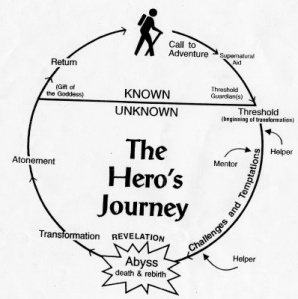

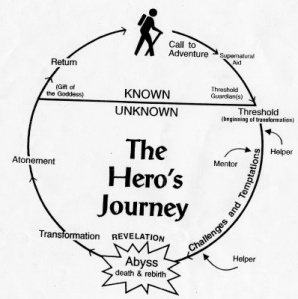

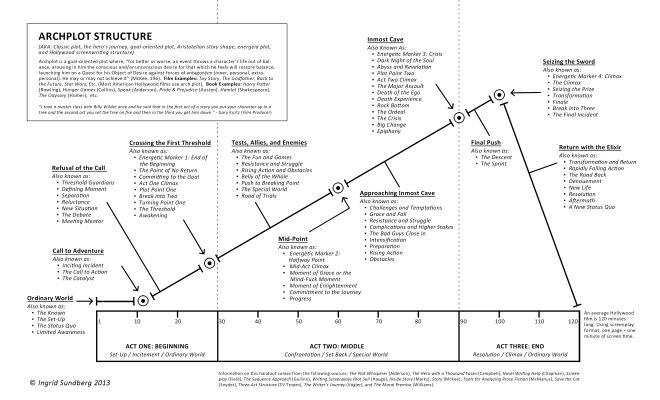

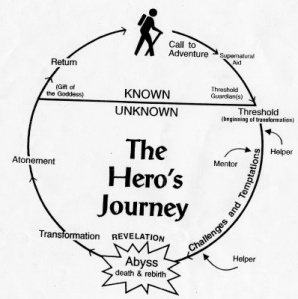

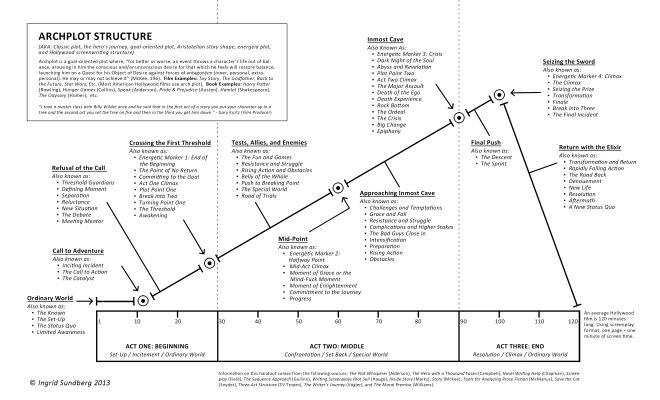

As an introduction to my series on Organic Architecture, I thought I’d start out with the ol’ granddaddy of plot structures: Arch Plot. You probably already know all about this plot structure, but to make sure we’re all on the same page, I wanted to do a quick overview.

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

- Classic plot

- The hero’s journey

- Goal-oriented plot

- Aristotelian story shape

- Energeia plot

- Three-act structure

- Hollywood screenwriting structure

- The Universal Story

Arch plot is a goal-oriented plot where, “for better or worse, an event throws a character’s life out of balance, arousing in him the conscious and/or unconscious desire for that which he feels will restore balance, launching him on a Quest for his Object of Desire against forces of antagonism (inner, personal, extra-personal). He may or may not achieve it” (McKee, 196). Film examples of arch plot include: Toy Story, The Godfather, Back to the Future, Star Wars, Etc. (Most American Hollywood films use arch plot). Book examples of arch plot include: Harry Potter (Rowling), Hunger Games (Collins), Speak (Anderson), Pride & Prejudice (Austen), Hamlet (Shakespeare), The Odyssey (Homer), etc.

A story that uses classic design has eleven basic story sections. Depending on which books you read these story beats all have different titles. I’ve culled the information below from a variety of different sources, each of whom give arch plot design their own title (i.e. classic plot, the hero’s journey, etc.), but at its core they’re all talking about the same design. For the major sequences and beats, the header titles use Joseph Campbell and Christopher Vogler’s Hero’s Journey terminology, and under that you’ll see a list of the same beat termed differently by others. Thus, what Campbell calls the Call to Action, McKee calls the Inciting Incident, and Blake Snyder calls The Catalyst.

THE ELEVEN STORY BEATS OF ARCH PLOT:

ACT ONE

The Ordinary World: The hero’s life is established in his ordinary world.

This story beat is also known as:

- The Known

- The Set-Up

- The Status Quo

- Limited Awareness

Call to Adventure: Something changes in the hero’s life to cause him to take action.

This story beat is also known as:

- TheInciting Incident

- The Call to Action

- The Catalyst

Refusal of the Call: The hero refuses to take action hoping his life with go back to normal. Which it will not.

Also known as:

- Threshold Guardians

- Defining Moment

- Separation

- Reluctance

- New Situation

- The Debate

- Meeting Mentor

Crossing the First Threshold: The hero is pushed to a point of no return where he must answer the call and begin his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 1: End of the Beginning

- The Point of No Return

- Committing to the Goal

- Act One Climax

- Plot Point One

- Break into Two

- Turning Point One

- The Threshold

- Awakening

ACT TWO

Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The journey through the special world is full of tests and obstacles that challenge the hero emotionally and/or physically.

Also known as:

- The Fun and Games

- Resistance and Struggle

- Rising Action and Obstacles

- Belly of the Whale

- Push to Breaking Point

- The Special World

- Road of Trials

Mid-Point: The energy of the story shifts dramatically. New information is discovered (for positive or negative) that commits the hero to his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 2: Halfway Point

- Mid-Act Climax

- Moment of Grace or the Mind-Fuck Moment

- Moment of Enlightenment

- Commitment to the Journey

- Progress

Approaching Inmost Cave: The hero gets closer to reaching his goal and must prepare for the upcoming battle (emotional or physical).

Also known as:

- Challenges and Temptations

- Grace and Fall

- Resistance and Struggle

- Complications and Higher Stakes

- The Bad Guys Close In

- Intensification

- Preparation

- Rising Action

- Obstacles

Inmost Cave: The hero hits rock bottom. He fails miserably and must come to face his deepest fear. This causes self-revelation.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 3: Crisis

- Dark Night of the Soul

- Abyss and Revelation

- Plot Point Two

- Act Two Climax

- The Major Assault

- Death of the Ego

- Death Experience

- Rock Bottom

- The Ordeal

- The Crisis

- Big Change

- Epiphany

ACT THREE

Final Push: The hero makes a new plan to achieve his goal.

Also known as:

Seizing the Sword: The hero faces his foe in a final climactic battle. The information learned during the crisis is essential to beating this foe.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 4: Climax

- The Climax

- Seizing the Prize

- Transformation

- Finale

- Break Into Three

- The Final Incident

Return with the Elixir: The hero returns home with the fruits of his adventure. He begins his life as a changed person, now living in the “new ordinary world”.

Also known as:

- Transformation and Return

- Rapidly Falling Action

- The Road Back

- Denouement

- New Life

- Resolution

- Aftermath

- A New Status Quo

- Return to the New Ordinary World

“I took a master class with Billy Wilder once and he said that in the first act of a story you put your character up in a tree and the second act you set the tree on fire and then in the third you get him down.” – Gary Kurtz (Film Producer)

Bibliography:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

As an introduction to my series on Organic Architecture, I thought I’d start out with the ol’ granddaddy of plot structures: Arch Plot. You probably already know all about this plot structure, but to make sure we’re all on the same page, I wanted to do a quick overview.

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

- Classic plot

- The hero’s journey

- Goal-oriented plot

- Aristotelian story shape

- Energeia plot

- Three-act structure

- Hollywood screenwriting structure

- The Universal Story

Arch plot is a goal-oriented plot where, “for better or worse, an event throws a character’s life out of balance, arousing in him the conscious and/or unconscious desire for that which he feels will restore balance, launching him on a Quest for his Object of Desire against forces of antagonism (inner, personal, extra-personal). He may or may not achieve it” (McKee, 196). Film examples of arch plot include: Toy Story, The Godfather, Back to the Future, Star Wars, Etc. (Most American Hollywood films use arch plot). Book examples of arch plot include: Harry Potter (Rowling), Hunger Games (Collins), Speak (Anderson), Pride & Prejudice (Austen), Hamlet (Shakespeare), The Odyssey (Homer), etc.

A story that uses classic design has eleven basic story sections. Depending on which books you read these story beats all have different titles. I’ve culled the information below from a variety of different sources, each of whom give arch plot design their own title (i.e. classic plot, the hero’s journey, etc.), but at its core they’re all talking about the same design. For the major sequences and beats, the header titles use Joseph Campbell and Christopher Vogler’s Hero’s Journey terminology, and under that you’ll see a list of the same beat termed differently by others. Thus, what Campbell calls the Call to Action, McKee calls the Inciting Incident, and Blake Snyder calls The Catalyst.

THE ELEVEN STORY BEATS OF ARCH PLOT:

ACT ONE

The Ordinary World: The hero’s life is established in his ordinary world.

This story beat is also known as:

- The Known

- The Set-Up

- The Status Quo

- Limited Awareness

Call to Adventure: Something changes in the hero’s life to cause him to take action.

This story beat is also known as:

- TheInciting Incident

- The Call to Action

- The Catalyst

Refusal of the Call: The hero refuses to take action hoping his life with go back to normal. Which it will not.

Also known as:

- Threshold Guardians

- Defining Moment

- Separation

- Reluctance

- New Situation

- The Debate

- Meeting Mentor

Crossing the First Threshold: The hero is pushed to a point of no return where he must answer the call and begin his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 1: End of the Beginning

- The Point of No Return

- Committing to the Goal

- Act One Climax

- Plot Point One

- Break into Two

- Turning Point One

- The Threshold

- Awakening

ACT TWO

Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The journey through the special world is full of tests and obstacles that challenge the hero emotionally and/or physically.

Also known as:

- The Fun and Games

- Resistance and Struggle

- Rising Action and Obstacles

- Belly of the Whale

- Push to Breaking Point

- The Special World

- Road of Trials

Mid-Point: The energy of the story shifts dramatically. New information is discovered (for positive or negative) that commits the hero to his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 2: Halfway Point

- Mid-Act Climax

- Moment of Grace or the Mind-Fuck Moment

- Moment of Enlightenment

- Commitment to the Journey

- Progress

Approaching Inmost Cave: The hero gets closer to reaching his goal and must prepare for the upcoming battle (emotional or physical).

Also known as:

- Challenges and Temptations

- Grace and Fall

- Resistance and Struggle

- Complications and Higher Stakes

- The Bad Guys Close In

- Intensification

- Preparation

- Rising Action

- Obstacles

Inmost Cave: The hero hits rock bottom. He fails miserably and must come to face his deepest fear. This causes self-revelation.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 3: Crisis

- Dark Night of the Soul

- Abyss and Revelation

- Plot Point Two

- Act Two Climax

- The Major Assault

- Death of the Ego

- Death Experience

- Rock Bottom

- The Ordeal

- The Crisis

- Big Change

- Epiphany

ACT THREE

Final Push: The hero makes a new plan to achieve his goal.

Also known as:

Seizing the Sword: The hero faces his foe in a final climactic battle. The information learned during the crisis is essential to beating this foe.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 4: Climax

- The Climax

- Seizing the Prize

- Transformation

- Finale

- Break Into Three

- The Final Incident

Return with the Elixir: The hero returns home with the fruits of his adventure. He begins his life as a changed person, now living in the “new ordinary world”.

Also known as:

- Transformation and Return

- Rapidly Falling Action

- The Road Back

- Denouement

- New Life

- Resolution

- Aftermath

- A New Status Quo

- Return to the New Ordinary World

“I took a master class with Billy Wilder once and he said that in the first act of a story you put your character up in a tree and the second act you set the tree on fire and then in the third you get him down.” – Gary Kurtz (Film Producer)

Bibliography:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

By:

Emma Walton Hamilton,

on 8/5/2012

Blog:

Emmasaries

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

childrens books,

plot,

series,

writing for children,

writers resources,

book series,

storyboard,

plot structure,

writing a series,

plot sequence,

Blog,

writing resources,

Add a tag

When it comes to maintaining continuity of plot details in a series, it can be helpful to create a scene chart or a storyboard for each story as well as for the overall series itself.

When it comes to maintaining continuity of plot details in a series, it can be helpful to create a scene chart or a storyboard for each story as well as for the overall series itself.

Some novelists use index cards or Post-it notes to build a storyboard, because they allow for manipulation of the sequence of events in quick and immediately visible ways – but for tracking the many elements of a series over several books, a spreadsheet may be a better choice.

Whichever method you choose, the elements to consider keeping track of include:

- Book Number / Title

- Chapter Number / Title

- Scene Number

- Time / Time Frame

- Location / Setting

- Characters

- Central Problem/ Conflict

- Action / Events

- Surprises / New Information

- Open Questions

The last item is particularly important when it comes to avoiding red herrings and tying up loose ends. Make note of any questions, puzzles or mysteries that come up in the course of a chapter so that you can track when, where and how they get resolved.

Of course tracking plot details for continuity is different than crafting a plot in the first place – but keeping a record of the myriad details can be helpful when it comes to plot development and the editing/revision process. On the Children’s Book Hub, we have spreadsheets for both crafting plot and tracking the details, but you can create your own by copying and pasting the above elements into headings on a spreadsheet.

Next up, continuity of voice…

Be sure to read the first six parts of this essay:

Defining Plot Structure:

Defining Plot Structure:

If story structure is a form of organization for a story that may or may not have a plot, what is plot structure? It’s important to note that plot structure is a type of story structure, but the two terms are not interchangeable. The most common story shape for plot structure is the Fichtean Curve (see figure 4). Talked about at length in Gardner’s book The Art of Fiction, this plot structure reflects the goal-oriented plot. In essence, the character has a goal and follows a series of three or more obstacles of increasing intensity in order to achieve that goal. The protagonist reaches an ultimate conflict called the climax and then proceeds to a resolution. This common story shape is often called the Aristotelian Story Shape. However, this may be a falsehood. Aristotle only mentioned that stories should have beginnings, middles, and ends (hence the three act structure). Aristotle had very little to say about plot structure according to author M.T. Anderson:

Structurally in terms of abstract story shape, Aristotle doesn’t really give us much of a pointer. He says ‘for every tragedy there is a complication and a denouement. By complication I mean everything from the beginning, as far as the part that immediately precedes the transformation to prosperity or affliction. And by denouement, I mean the start of the transformation to the end.’ So, it is really more of a two part thing, and he gives you no real sense of the proportion those two things should be in. It’s not actually tremendously useful.

Thus the story shape (the Fichtean curve) came later as others developed new theories of plot structure.

Another common shape is Freytag’s Pyramid, (also called Freytag’s Triangle) which many illustrate with close similarity to the Fichtean curve (see figure 5A). However, this is a distortion, and Freytag’s pyramid is actually symmetrical in its triangular form (see figure 5B), and reflects a Germanic idea of story shape (Anderson). Despite the name, this common plot-structure includes the elements of: Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and a Denouncement. It’s also very popular as Klien points out:

Another common shape is Freytag’s Pyramid, (also called Freytag’s Triangle) which many illustrate with close similarity to the Fichtean curve (see figure 5A). However, this is a distortion, and Freytag’s pyramid is actually symmetrical in its triangular form (see figure 5B), and reflects a Germanic idea of story shape (Anderson). Despite the name, this common plot-structure includes the elements of: Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and a Denouncement. It’s also very popular as Klien points out:

You can see this structure everywhere. It’s Aristotle’s Greek tragedies. It’s all six Jane Austen novels. It’s in all six Harry Potters. It’s mystery novels, romance novels, most every pop song ever written, U2, Stevie Wonder. And the reason for that is, again, catharsis: all the emotion building up through your interest in the characters and their actions, exploding at the climax, leaving you drained but renewed. (Klein, 10

Be sure to read the first four parts of this essay:

Structure – Looking at the Whole:

Structure – Looking at the Whole:

When it comes to talking about structure we need to be careful of our wording. The terms narrative structure, story structure, and plot structure seem to be intertwined and often used interchangeably, but they aren’t the same (as we’ve learned with our previous exploration of terms). First, let’s look at the idea of structure alone. The Random House Dictionary defines structure as: “a mode of building, construction, or organization; arrangement of parts, or elements.” In addition, it says “structure is a complex system considered from the point of view of the whole rather than of any single part.” Here we have the two key elements of structure. First, it’s a mode of arrangement and organization, and second, it takes into consideration the whole. Chea explains that “in examining structure, we look for patterns, for the shape that the story as a whole possesses. Plot directs us to the story in motion, structure to the story at rest”(2). Meanwhile, film teacher Judy Lewis adds “structure is the term used to describe the organization of the story, including the order in which a story is told.”

When questions of linear vs. non-linear storytelling arise, it’s important to realize that plot is always linear. But non-linear storytelling can still have a plot, but the non-linear organization is a choice of structure. Ultimately, in a non-linear story the reader will piece together the plot to create the chronological relationships, as Lisa Cowgill states in her essay on non-linear narratives:

The unconventional structure doesn’t mean audiences understand film in a new way. Viewers understand by making cause-and-effect connections between the scenes. Each beat of information must relate to what comes before and after, even if a scene transcends the chronological order of time. In nonlinear films, relationships created between the various time segments form a specific meaning when taken all together.

Additionally, choices of organization and structure also have to do with authorial intent. “Structure is important for another reason: It provides a clue to a story’s meaning… paying attention to repeated elements and recurrent details … repetition signals important connections and relationships in the story” (Chea). After all, why would someone choose to tell a story out of sequence if not to lead the reader to make a connection between the scenes? Therefore structure is form (choices of organization, patterns) with specific intent (meaning) that can be observed as part of the whole.

Structure as authorial intent can also be taken a step further to reveal audience manipulation. Structural choices, as editor Cheryl Klein points out, is “the author orchestrating the emotion.” Author An Na refers to this emotional base as the root-line in her lecture on structuring stories. She elaborates:

It’s all that darker deeper stuff t

By:

Emma Walton Hamilton,

on 5/23/2011

Blog:

Emmasaries

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Blog,

childrens books,

plot,

writing for children,

story structure,

writers resources,

plot structure,

plot development,

Writing Childrens Books,

plot sequence,

Add a tag

In my “Just Write for Kids” course, we spend quite a bit of time exploring different ways to develop plot.

In my “Just Write for Kids” course, we spend quite a bit of time exploring different ways to develop plot.

We look at basic three-act storytelling structure:

Act 1 – Set-up/Intro to character(s) and problem

Act 2 – Problem escalates to crisis or turning point

Act 3 – Resolution/Character solves problem and/or learns something, grows or changes in process

Another great way to develop or measure your plot is against the following story structure, or plot sequence:

- Something happens to someone

- Which leads to their wanting/needing something, and/or making a goal

- Which needs a plan of action

- But forces try to stop the protagonist (obstacles occur)

- Yet they move forward (because there is a lot at stake)

- But then, there’s a crisis! Things get as bad as they can

- And they learn an important lesson

- Which helps them overcome the final obstacle

- Thus satisfying the need created by something in the past.

Here’s an example of how this might work as measured against our recent picture book, The Very Fairy Princess:

- Something happens to someone – Gerry learns she will be part of a new ballet, The Crystal Princess, at her ballet school

- Which leads to their wanting/needing something, and/or making a goal – She wants to play the lead – the Crystal Princess!

- Which needs a plan of action – she offers all the reasons why she is perfect for the part (already has the costume, accessories, is a natural etc.)

- But forces try to stop the protagonist (obstacles occur) – she is cast as the Court Jester instead. Worse, she hates her costume, which makes her look like a boy.

- Yet they move forward (because there is a lot at stake) – She really wants to be in the ballet, so she swallows her pride, and plays the jester. She also hides her crown under her jesters hat, so as to still be a fairy princess underneath.

- But then, there’s a crisis! Things get as bad as they can – When it comes time to perform the ballet, everything that can go wrong, does… Gerry steps on Tiffany’s (who plays the Princess) toes, trips over her stick, and her crown slips out from under her hat. She is in serious danger of losing her ‘sparkle’ altogether. Then, Tiffany’s crown falls off and gets crushed – and the ballet mistress expects Gerry to give Tiffany HER crown!

- And they learn an important lesson – Gerry realizes that a Crystal Princess REALLY needs to sparkle, and by lending her crown to Tiffany, her own sparkle comes rushing back.

- Which helps them overcome the final obstacle – By saving the show, and the day, Gerry makes friends with Tiffany. She also gets to be seated in the front of the company photo, and to keep her jester’s stick and hat. Plus, her own crown feels ‘extra-sparkly’ when Tiffany gives it back.

- Thus satisfying the need created by something in the past. – Gerry ends up being a star after all — in a different way than she imagined, but perhaps an even more satisfying one.

This tool can be used to develop an initial plot, or

By:

Emma Walton Hamilton,

on 3/30/2011

Blog:

Emmasaries

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Blog,

childrens books,

picture books,

Maurice Sendak,

Jane Yolen,

endings,

writing for children,

resolution,

Where the Wild Things Are,

Happy Endings,

plot structure,

Writing Childrens Books,

Children's Book Endings,

Add a tag

And so we come to the last of my series of posts based on Jane Yolen’s list of “10 Words Every Picture Book Author Must Know.” Resolution… a fitting word to end the series with! Thank you, Jane, for providing us with such thought-provoking bounty (and two months worth of fodder for blog posts!)

And so we come to the last of my series of posts based on Jane Yolen’s list of “10 Words Every Picture Book Author Must Know.” Resolution… a fitting word to end the series with! Thank you, Jane, for providing us with such thought-provoking bounty (and two months worth of fodder for blog posts!)

Resolution shares its root with “resolve,” and in literary terms, it means the point within the story when the central conflict is worked out, or the problem is solved. Perhaps not exactly how the protagonist intended or hoped, but solved nonetheless, and in such a way that the hero has learned something and has changed or grown in the process.

The best resolutions satisfy a need created at the beginning of the book. This needn’t be happy – but it should feel both earned and inevitable, which is different from predictable. Rather than anticipating how the book will end, the reader should be pleasantly surprised, yet also feel “But of course it had to end that way!” And picture book endings must also be clear, as opposed to implied or left open; young readers may have difficulty choosing between possible outcomes.