new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: guns, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 30

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: guns in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: KatherineS,

on 10/21/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

war,

Technology,

military history,

guns,

weapons,

Very Short Introductions,

gunpowder,

*Featured,

Alex Roland,

carbon age,

chemical age,

George Armstrong Custer,

history of technology,

Little Big Horn,

Maxim gun,

Norbert Elias,

War and Technology: A Very Short Introduction,

Add a tag

Few inventions have shaped history as powerfully as gunpowder. It significantly altered the human narrative in at least nine significant ways. The most important and enduring of those changes is the triumph of civilization over the “barbarians.” That last term rings discordant in the modern ear, but I use it in the original Greek sense to mean “not Greek” or “not civilized.” The irony, however, is not that gunpowder reduced violence.

The post The irony of gunpowder appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Lizzie Furey,

on 2/7/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Politics,

Barack Obama,

guns,

Obama,

President Obama,

gun control,

*Featured,

Matthew Flinders,

Gun Violence,

Political Spike with Matthew Flinders,

political spike,

gun legistlation,

Add a tag

It would seem that President Obama has a new prey in his sites. It is, however, a target that he has hunted for some time but never really managed to wound, let alone kill. The focus of Obama’s attention is gun violence and the aim is really to make American communities safer places to live.

The post Bang, bang — democracy’s dead: Obama and the politics of gun control appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Franca Driessen,

on 11/29/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Immanuel Kant,

a priori,

Arts & Humanities,

Cognition Content and the A Priori,

robert hanna,

Ferguson unrest,

Kantian philosophy,

Books,

Law,

Philosophy,

guns,

violence,

capital punishment,

death penalty,

gun control,

Second Amendment,

*Featured,

Add a tag

In this post, starting again with a few highly-plausible Kantian metaphysical, moral, and political premises, I want to present two new, simple, step-by-step arguments which prove decisively that the ownership and use of firearms (aka guns) and capital punishment (aka the death penalty) are both rationally unjustified and immoral.

The post A world with persons but without guns or the death penalty appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

Heidi MacDonald,

on 10/18/2015

Blog:

PW -The Beat

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

shootings,

Helloween!,

Top News,

The Legal View,

Top Comics,

SDCC '14,

ZombiCon,

Comics,

Sociology,

Legal Matters,

Conventions,

Culture,

Image,

Breaking News,

guns,

Walking Dead,

crowds,

Add a tag

Gunfire at the Ft. Myers charitable event created a real-life running zombie herd, but the organizers’ security safeguards may have helped prevent further harm. Shootings have become a depressing fact of life here in the U.S. — and for those of you who spent a fair amount of time in New York and other large […]

"In other words, yes, we really do want to take your guns. Maybe not all of them. But a lot of them."

—Josh Marshall, Talking Points Memo

Okay. All I've got's an antique rifle that would likely explode if fired, so no big deal to me. I would love to live in a country with far, far fewer guns. One of the reasons I think the NRA should be considered complicit with murder is their careful collusion over the last few decades with gun manufacturers to keep a flooded market profitable by using every scare tactic they could imagine to encourage people to keep buying. (I've written about all this, and other aspects of gun culture, plenty of times

before.) I'm quite comfortable around guns, since I grew up with them as an everyday object (everything from .22 pistols to fully-automatic machine guns), and I have many friends who are gun owners, even

gun nuts. But though I sometimes find guns attractive, even fascinating, I don't

like them and I wish there were vastly fewer. The Oregon shooting happened at a place I'm familiar with, half an hour from the home of one of my best, most beloved friends. The present reality of mass shootings in the US is grotesque, and the easy availability of guns is a major part of the problem.

But I think Josh Marshall is delusional. No matter how much you wish for it, the guns in the United States are not going to be confiscated, and not just because of a lack of political will. The NRA sells the fear of confiscation to gun nuts all the time, but it is not just unlikely and not just politically difficult — given the amount of guns in the US, it is as close to impossible to achieve as any such thing is. The horse left the barn at least forty years ago.

Certainly, it's valuable for activists to come out and say what they want rather than to lie or, at best, hedge their commentary to appear less radical. I like radicals, especially nonviolent ones, so I'm all for being openly radical.

And the idealism in Marshall's blog post is nice. I understand the feeling. But it's fairy-tale utopian. You want to think big, to be honest about your ultimate goals, and so you want to stop talking about things that might actually be able to be accomplished like universal background checks and maybe some restrictions on certain sizes of magazines and certain styles of rifles. I get it. I would like to stop talking about how I'll pay next month's bills and instead dream about winning the lottery.

But at a certain point you have to explain how you want to go about achieving your dream. What are the actual mechanics? What are the mechanisms that would bring your dream to reality? The fact is, I have a vastly better chance of winning the lottery than the US has any chance of significant gun confiscation.

Let's pretend we live in a fairy land where somehow the government would pass laws like the ones Australia famously passed. For basic background on that and how it worked,

here's an overview from Vox. There are a bunch of things in there that are pretty much politically inconceivable in the US, even if

they would likely survive challenge in the courts. But we're playing Let's Pretend.

So let's pretend those laws pass. We can't, though, forget the fundamental, awful, maddening, bizzaro truth: including both legal and illegal weapons, by even conservative estimates, there are somewhere around as many guns as people in the U.S. Numbers are notoriously difficult to get, but let's say 300 million, just to have a nice even number to play with. (It could be 250 million, it could be 350 million. What's fifty million here or there when counting deadly weapons?)

Let's pretend Australian-style laws pass, which would mean the goal is to get to 20% of guns bought back, as Australia apparently

did. We're talking, then, somewhere around 60 million guns. (Router and Mouzos in their study of Australia say it would be 40 million, but, again, estimates always differ, and a lot depends on whether you're also including the black market, antique guns [some of which, unlike mine, shoot quite well], etc.)

How do you collect and destroy between 40 and 60 million guns?

If it's a buyback, how do you pay for the guns you're buying back? In 1996 in Australia, the average price paid was US$359. For 60 million guns, that would be $21,540,000,000. Not an impossible amount, given that we casually spent at least that per month of war in Iraq, but still. Twenty-one-and-a-half billion dollars is not small change, and that's 1996 dollars.

What do you do with people who won't turn their guns in? I could be wrong, but I doubt most American gun owners would turn in their guns, at least not the guns they cared about. Sure, they might turn in stuff that was in bad shape, or that they didn't especially want anymore. You want to give me good market value for a gun I don't care about? Great! Here it is. Enjoy. Thanks for the cash.

What about the rest? The guns you want to confiscate are not the ones most gun owners are likely to turn in for even a mandatory buyback. And what does

mandatory mean? How do you make it mandatory? Who enforces it? How?

You'd need a registry, but how would you create a registry? You could mandate a registry of all new sales of guns, but that doesn't do anything about the 300 million, give or take 50 million, already out there. You could try using data from

Form 4473, but by the time all the laws get passed and Federal Firearms License holders are notified that they have to turn all of their 4473 info over to the ATF, most of those forms, I expect, will have somehow mysteriously gotten destroyed in floods and fires, have been misplaced, etc. You could say, "All gun owners are now required to register their weapons!" and the laughter would be cacophonous.

So what will you do about civil disobedience?

Send the police!

Great idea. The police. The nice (white) liberal's fallback answer to every problem. Tut tut occasionally about the cops' embarrassing habit of killing black men every day, then turn around and advocate for giving the police even more power.

The fact is, to collect even a small percentage of the guns currently in circulation in the US, you would have to institute highly authoritarian laws, strongly empower the police and military to take action against otherwise law-abiding citizens, punish any disobedient police and military members strongly (and there would be a lot of disobedience within the ranks, I expect), and violate a bunch of civil liberties so you could find out who owned what weapons. And imprison lots of people. (Yay,

prisons!)

If you're going to be honest about what you want, then you have to be honest about how you would like to get what you want. The complete statement Josh Marshall and others should make is this one: "We really do want to take your guns, and we are willing to empower the state to do so via the police and, if necessary, the military. If you resist, we will imprison you."

Not quite so rosy a fairy tale now, is it?

Do I have a better fairy tale? Not really. I have no solution, certainly nothing short term. Various small, achievable regulations might do a little bit of good. The best I can imagine is a change in culture, a change in attitudes where gun ownership is viewed the way smoking is today, as an unfortunate, smelly, lethal vice/addiction, that, despite whatever momentary pleasures it may offer, is harmful to individuals and society.

Start pitying gun nuts. Listen to their macho power fantasies and nod your head sadly and say, "I'm truly sorry you feel so terrified all the time, so inadequate. I'm so sorry that you feel the only way to get through your days is to keep the power of life or death over other people with you at all times. If you ever want help, please ask. I know the withdrawal will be incredibly hard and painful, but the results will be worth it. We'll all get to live a little longer."

Imagine encouraging doctors to talk to people about the statistics on guns and

public health. (Imagine better funding for research on guns and public health!)

Imagine interventions for people with NRA Derangement Syndrome (the mental disorder that results in a person believing NRA propaganda, needing to stockpile tens of thousands of rounds, needing to own dozens and hundreds of guns just in case one day the gun grabbers succeed with their nefarious plans and/or the zombie apocalypse occurs).

Imagine cognitive behavioral therapy for hoarders of deadly weapons.

Imagine alternatives to toxic masculinity and warrior dreams.

Imagine movies and TV shows and video games where guns are portrayed not as sexy and awesome, but as the last refuge of the weak and deranged.

Imagine— Well, go ahead, we're talking fairy tales, so imagine whatever you want. But think, too, about how we get to fairyland.

With cons and fan events growing in popularity, and shooting an almost everyday occurrence here in the US, one wonders if there will ever be an "incident" at a con. Well here's one that MAY have been thwarted. It seems two invited participants in the Pokémon World Championships were arrested after making some online threats and showing up armed to the teeth:

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 6/18/2015

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Africa,

politics,

culture,

South Africa,

terrorism,

guns,

violence,

white supremacy,

Rhodesia,

Add a tag

When the suspect in the

attack on the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in South Carolina was identified, the authorities circulated a photograph of him wearing a jacket adorned with the flags of apartheid-era

South Africa and post-

UDI Rhodesia.

The symbolism isn't subtle. Like the

confederate flag that flies over the South Carolina capitol, these are flags of explicitly white supremacist governments.

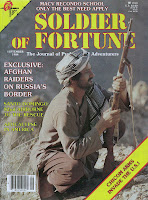

Rhodesia plays a particular role within right-wing American militia culture, linking anti-communism and white supremacy. The downfall of white Rhodesia has its own sort of lost cause mythic power not just for avowed white supremacists, but for the paramilitarist wing of gun culture generally.

The power of Rhodesia for paramilitarists is evident throughout the history of

Soldier of Fortune magazine, a magazine that in the 1980s especially achieved real prominence. The first issue of

SoF was published in the summer of 1975, and its cover story, titled "American Mercenaries in Africa", was publisher

Robert K. Brown's tale of his visit to Rhodesia in the spring of 1974. (You can see

the whole issue here on Scribd.

Warning: There's a gruesome and disturbing picture of a corpse with a head wound accompanying the article.) For Brown's perspective on his time in Rhodesia, see

this post at Ammoland.

SoF continued to publish articles on Rhodesia throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s. They also published articles about South Africa. Here's a two-page spread from the August 1985 anniversary issue (click to enlarge):

The introduction to the first article states:

SOF made quite a reputation in the early years of publication for fearless, firsthand reporting from the bloody battlefields of Rhodesia. Our efforts in that ill-fated African nation and our support of the Rhodesian government in operations against communist insurgents gained us two unfortunate, undeserved labels: racists and mercenaries. We are neither. On the other hand, we have never avoided consorting with genuine mercs to insure readers get the look and feel of Third World battlefields.

It's true that anti-communism was the primary ideology of

SoF in the 1970s and 1980s and that they would take the side of anyone they considered anti-communist regardless of their race or nationality — they published countless articles supporting the mujahideen in Afghanistan, the

Karen rebels in Burma (heroes of

Rambo 4), and the contras in Nicaragua. (Ronald Reagan, he of the Iran-Contra scandal, supported white Rhodesia even longer than Henry Kissinger, causing them to have their first public disagreement. See Rick Perlstein's

The Invisible Bridge pp. 671-673.) But the kind of anti-communism that supported

Ian Smith's Rhodesia and apartheid South Africa was an anti-communism that supported white supremacist government.

The second page there begins an article written by a veteran of the South African anti-insurgency campaigns, and it sings the praises of the brutal

Koevoet (crowbar) unit in Namibia. Here's a passage from the next page: "It doesn't pay to play insurgency games with Koevoet.

SWAPO had felt the force of the crowbar designed to pry them out of Ovamboland."

It's no great mystery why such campaigns would appeal to white supremacist groups, and why white supremacists would use the examples of Rhodesia and South Africa to stoke the fears and passions of their followers.

Consider the

Greensboro massacre of November 1979. Tensions between the Communist Workers Party and the Ku Klux Klan led to the Klan and the American Nazi Party killing 5 activists. The neo-Nazi and Klan members accused of the crimes were acquitted. The head of the North Carolina chapter of the National Socialist (Nazi) Party of America in 1979 was Harold Covington, who was implicated in the massacre but never faced criminal charges. Covington loved to brag that he'd been a mercenary in Rhodesia, though his brother

claimed that wasn't quite accurate:

I suppose he wanted to move someplace where everything was white and bright, so after a yearlong stint at the Nazi Party headquarters, he wound up going to Rhodesia, and he joined the Rhodesian Army. In different blogs and writings, he was always bragging, "Oh, I was a mercenary in Rhodesia and I went out and did all this fighting." But to the best of my knowledge, according to the letters he wrote to my parents, he was a file clerk. He certainly never fired a shot in anger. He started agitating over there, and the [white-led] Ian Smith government said, "We have problems enough without this nutcase," and they bounced him.

The myth of the lost white land of Rhodesia has proved resilient for the paramilitary right. It plays into macho adventure fantasies as well as terror fantasies of black hordes wiping out virtuous white minorities. Rhodesia sits comfortably among the other icons of militia culture, as James William Gibson showed in his 1994 book

Warrior Dreams, in which he described a visit to a

Soldier of Fortune convention:

All the T-shirts had their poster equivalent, but much else was available, too. John Wayne showed up in poses ranging from his Western classics to The Sands of Iwo Jima (1949) and The Green Berets (1968). Robocop and Clint Eastwood's Dirty Harry decorated many a vendor's stall. An old Rhodesian Army recruiting poster with the invitation "Be a Man Among Men" hung alongside a "combat art" poster showing a helicopter door gunner whose wolf eyes stared out from under his helmet; heavy body armor and twin machine gun mounts hid his mortal flesh. (157-158)

Anti-communism doesn't have much resonance these days, and so the support of Rhodesia or apartheid South Africa can no longer be couched in any terms other than ones of white supremacy — terms that were previously always at least in the shadows. Militarism, machismo, and white supremacy have no objection to hanging out together, and the result of their association is often deadly.

See also: "The connection between terrorist Dylann Roof and white-supremacist regimes in Africa runs through the heart of US conservatism" from Africa as a Country.

A friend pointed me toward

Sigrid Nunez's New York Times review of Emily St. John Mandel's popular and award-winning novel

Station Eleven. He said it expressed some of the reservations that caused me to stop reading the book, and it does — at the end of her piece, Nunez says exactly what I was thinking as I put the book down with, I'll confess, a certain amount of disgust:

If “Station Eleven” reveals little insight into the effects of extreme terror and misery on humanity, it offers comfort and hope to those who believe, or want to believe, that doomsday can be survived, that in spite of everything people will remain good at heart, and that when they start building a new world they will want what was best about the old.

I don't mean this post to be about

Station Eleven, because I didn't finish reading it and for all I know, if I'd finished reading it I might disagree with Nunez. I bring it up because even if, somehow, Nunez is wrong about

Station Eleven, her points are important ones in this age of popular apocalypse stories.

Let me put my cards on the table. I have come to think stories that give readers hope for tolerable life after an apocalypse are not just inaccurate, but despicable.

We are living in an apocalypse. Unless massive changes are made in the next few decades, it's highly likely that the Earth's biosphere will alter drastically enough to kill off most forms of life. At the least, life in the next 100-200 years is likely to be less pleasant than life now (if you think life now is pleasant). Writing apocalypse stories that mitigate these facts lulls us into complacency. Such stories are their own form of global warming denialism. (Of course, if you are a global warming denialist, go right ahead — write and enjoy such stories!)

Tales of surviving an apocalypse give us comfort fiction, a fiction predicated on identifying with the survivors and giving the survivors something worth surviving for.

It is highly unlikely that you, I, or anybody else would be a survivor of an actual apocalypse, and it is even more unlikely that, were we to survive, the post-apocalyptic world would be worth staying alive to see. To imagine yourself as a survivor is to evade the truth and to indulge in a ridiculous fantasy. To imagine yourself as a

successful survivor — someone who doesn't suffer terribly before finally, painfully dying — is even worse.

To tell stories of apocalypse that seek to be at least somewhat realistic and yet are not as painful as stories of actual, historical catastrophes is sheer escapist fantasy. Apocalypse stories that do not want to be escapist fantasies must be as harrowing and painful as the most awful stories of the Nazi Holocaust, the Khmer Rouge's atrocities in Cambodia, the Rwandan genocide.

I'd think this would be obvious, but many people ignore the fact: to tell a story of an apocalypse is to tell a story in the midst of mass death.

To tell a story of apocalypse that is not limited to a small area — to tell a story of the end of the whole world — is to tell a story about mass death on a scale far beyond the worst historical atrocities.

To tell a story of apocalypse in which people's lives are not even as difficult or painful as the lives of millions and millions of people currently alive on Earth moves beyond escapist fantasy and into the realm of idiotic irresponsibility. (This, perhaps, is why some of the better apocalypse/dystopia stories are written by people who are not middle-class white Americans.)

In

Eyes Wide Open, Frederic Raphael reported Stanley Kubrick's assessment of

Schindler's List: "Think that was about the Holocaust? That was about success, wasn’t it? The Holocaust is about six million people who get killed.

Schindler’s List was about six hundred people who don’t."

Obviously, the appeal of such stories is that they let us indulge in the fantasy of success. We love rags-to-riches stories for the same reason. We love stories about our soldiers wiping out lots of evil enemies because we escape imagining ourselves to be the enemy in the sniper's sights.

Who is this "we"? That's a good question for any story that aims for an audience to identify with protagonists, but it's especially good to ask of apocalypse stories. Do you read

Left Behind imagining yourself to be one of the good, one of the saved? Do you read

Station Eleven imagining that yes, you too could find a way to make a life for yourself in this world?

Or do you imagine yourself among the diseased, the tortured, the suffering, the unsaved, the dead?

"But," you say, "such stories offer us visions of human goodness even in the face of adversity! They alleviate pessimism. They help us to hope."

And that is why they are detestable.

The popular Anne Frank

statement that Nunez alludes to in her

Station Eleven review — "I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart" — was not written in

Bergen-Belsen. The story of Anne Frank is not complete until you tell the story of her and her family's suffering and slow death in a concentration camp. A survivor who claimed to have talked with Anne said she was weak, emaciated; that she suspected her parents to be dead; that she did not want to live any longer.

(If you want a happy ending, stop your story before the end.)

To write a story in which apocalypse is not especially awful — or is, even worse, somehow desireable — does nothing to help prevent the apocalypse we face, the apocalypse we live in.

Mass death should not be a self-help allegory.

I may feel so strongly about this because I grew up amidst (and still live around) militia culture, and militia cultists love to fantasize about the end of the world. They don't just dream; they try to live it. They stockpile food, ammo, weapons. They build shelters. They imagine all the ways they'll be heroes when the end comes. For some, it's literally a dream of The Rapture; for the less Christian fundamentalist among them, it's a kind of Rapture allegory, providing the same pleasures, the same confirmation of your own correctness. Apocalypse becomes not a horror but the opportunity to create the best of all possible worlds. Genocidaires always think their violent dreams are necessary, justified, virtuous.

The Walking Dead is popular with a lot of these folks. Step into a gun shop and you're plenty likely to hear at least one person talking about "the zombie apocalypse". It's a code phrase and an allegory: a code for the end of the boring world, an allegory for the time when the well-prepared (white, patriarchal) militia will ascend to its rightful place of honor, when the weak liberals and anti-gunners will die the sad deaths they so deserve, when it will be open season on all the zombies (read: immigrants, black people, etc.). Dreamers dream themselves among the survivors. They dream themselves into heroism. Instead of boring everyday life, they get to show their courage and strength and preparation.

Don't feel your life lets you express your inner heroism? Imagine yourself a survivor of apocalypse. Now you have a hero story.

Imagine yourself finally getting to use those tens of thousands of 5.56 rounds you stockpiled back when ammo was cheap. (You were one of the smart ones. Where are all the people who made fun of you now? They're dead, you're alive. You're the real man. Good for you. You win!)

Don't imagine yourself dying slowly, painfully. Don't imagine yourself wanting to die. Don't imagine disease, starvation, brutality.

We want stories to make us feel good about humanity, or at least about ourselves. We don't want realistic apocalypse stories.

That's what's behind so much of this dreck, isn't it? That somehow we know we're facing doom, and we don't want to feel bad about our own participation in that doom. We want doom to be on our own terms.

For the militia type, apocalypse stories are a way to imagine yourself into heroism. For the relatively wealthy and privileged, apocalypse stories are an opportunity to imagine our way out of the oppressions we benefit from.

(When I've assigned students to read Octavia Butler's

Parable of the Sower, there's always been someone who says, "This doesn't feel like science fiction. This feels real." True. And it's a real that hurts. Because it should.)

If you want to tell an apocalypse story, tell a story about well-intentioned people suffering and dying. Tell a story about people like yourself not only being helpless in the face of catastrophe, but being witless progenitors of it.

(One of my favorite apocalypse stories is Wallace Shawn's

The Fever. It's a story of the apocalypse of a well-intentioned man.)

Don't tell a story about how people like yourself are such great survivors. In truth, they probably aren't, and indulging in a fantasy of your own people's survival is breathtakingly arrogant in a story set amidst mass death.

(If the effects of your imagined apocalypse are less painful than the effects of Hurricane Katrina, you are writing despicable kitsch.)

I'm not saying tales of apocalypse are inevitably drivel, or even that they have to be a parade of endless horror, brutality, and suffering (though they should probably be mostly that). I'm saying we don't need apocalypse kitsch any more than we need Holocaust kitsch.

Watch the movies

Grave of the Fireflies and

Time of the Wolf. One is a historical film about the firebombing of Tokyo, the other is about a near-future apocalypse, its cause unknown, its effect coruscatingly clear. It's these films' affect that is most interesting to me, the ways they show disaster and the response to disaster, the ways they make you feel, and what those feelings are. These are not nihilistic stories, they don't deny human compassion and even goodness, but they also don't soft-pedal the suffering that happens with the end of a world.

Or think of it this way: If you had a time machine and could go back to Anatolia before 1915, Germany in the mid-'30s, Cambodia in the early '70s, Rwanda in the early '90s — if you could go back to those times and write stories, what sort of stories would you write? Stories of people surviving impending apocalypse?

If you want to tell stories to help prevent the extinction of the biosphere, don't tell stories that make that extinction seem bearable.

If you want to imagine the end of the world, realize what you are imagining.

It bothers me when I read something in a book that I know is wrong. Wrong and Google-able. (I started writing before the Internet, or at least before a widely available Internet, when it was not quite so easy to check things out. Twenty years ago, I felt more comfortable just guessing or making stuff up. No longer.)

(Guess what doesn't have a safety? That was the end of this book for me.)

With a little bit of time, you can figure out nearly anything without having to step away from your computer. Like:

- Do red-tailed hawks eat road kill? (If fresh, yes).

- Does Oregon pay for braces for kids in foster care? (No.)

- What time are trial advocacy classes at the University of Washington. (Late afternoon.)

- What testimony did the original grand jury hear in the Phoebe Prince case? (Actually, I couldn’t find that, which makes sense. Grand jury testimony is sealed. Still I would like to know more.)

One of the absolute best parts about my job as a mystery and thriller writer is doing research. In the past couple of years, I've:

Taken a class in fighting in close quarters. At the end, someone sat behind you in your car and attacked you with a training gun, a training knife, a plastic bag, and a rope.

Pulled out everything from underneath my kitchen sink, crawled into the space, and taken a picture to prove to one of my editors that yes, a body would fit under there.

Asked my kajukenbo instructor to drag me across the room, his hands underneath my arms, so that together we could figure out how a character could fight and get away.

Spent a day with a criminalist at Forensics Division of the Portland Police.

Faced down armed muggers, home invaders, crazy people, and robbers - all while armed with a modified Glock that uses lasers instead of real bullets. I did this at a firearms training simulator facility (the only one like it in the world that is open to civilians) which, lucky me, is just 20 minutes from my home. You interact with life-sized scenarios filmed in HD. The scenarios change depending on what you say (for example, “Hands in the air!”) and where your shots hit (a shot that disables versus one that injures). Meanwhile, the bad guys are shooting back. If you choose - and I do - you can wear a belt that gives you a 5000-volt shock if you’re shot. The facility even offers a simulation that is nearly 360 degrees, so you feel like you are standing in the middle of, say, the convenience store or the parking lot. This teaches you to look behind you for that second or third bad guy.

Every year, I go the Writers Police Academy, which is in North Carolina at a real police and fire academy. I also graduated from the FBI’s Citizen Academy, which is taught by real FBI agents and included a stint at a real gun range where I shot a submachine gun. I’m a member of Sisters in Crime, and my local chapter has experts speak every month (the blood spatter expert was particularly interesting). And I’m an online member of Crime Scene Writers, which has lots of retired or even active law enforcement personnel who answer questions.

By: Sarah Hansen,

on 6/13/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

goss,

Philip Cook,

The Gun Debate,

Law,

Sociology,

Politics,

Current Affairs,

guns,

gun control,

What Everyone Needs To Know,

*Featured,

homicide,

gun laws,

WENTK,

gun debate,

Kristin Goss,

polito,

suicides,

Add a tag

By Philip J. Cook and Kristin A. Goss

The debate over gun control generates more heat than light. But no matter how vigorously the claims and counterclaims are asserted, the basic facts are not just a matter of personal opinion. Here are our conclusions about some of the factual issues that are at the heart of the gun debate.

- Keeping a handgun to guard against intruders is now a Constitutional right. In Heller vs. District of Columbia (2008) and McDonald vs. Chicago (2010) the US Supreme Court ruled by a 5-4 majority that the Second Amendment provides a personal right to keep guns in the home. States and cities are hence not allowed to prohibit the private possession of handguns. However, the Court made it clear in these decisions that the Second Amendment does not rule out reasonable regulations of gun possession and use.

- Half of gun owners indicate that the primary reason they own a gun is self-defense. In practice, however, guns are only used in about 3% of cases where an intruder breaks into an occupied home, or about 30,000 times per year. That compares with over 42 million households with guns. One way to understand just how rare gun use is in self-defense of the home is to look at it this way: on average, a gun-owning household will use a gun to defend against an intruder once every 1,500 years.

- As many Americans die of gunshot wounds as in motor-vehicle crashes (around 33,000). In the last 30 years, over 1 million Americans have died in civilian shootings — more than all American combat deaths in all wars in the last century.

Non violence sculpture by Carl Fredrik Reutersward, Malmo, Sweden. Photo by Francois Polito. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

- Most gun deaths in the United States are suicides. There are 20,000 gun suicides per year, compared with 11,000 gun homicides and 600 fatal accidents. While there are hundreds of thousands of serious suicide attempts each year, mostly with drugs and cutting instruments, half of the successful suicides are with guns. The difference is in lethality — the case-fatality rate with guns is 90%, far higher than for the other common means. Availability influences choice of weapon; states with the highest prevalence of gun ownership have four times the gun suicide rate as the states with the lowest prevalence.

- The homicide rate today is half of what it was in 1991. That is part of the good news in the United States — violent crime rates of all kinds have plunged since the early 1990s, and violent crime with guns has declined in proportion. (Two thirds of all homicides are committed with guns.) Still, homicide remains a serious problem — homicide is the second leading cause of death for American youths. Our homicide rates remain far higher than those of Canada, the UK, Australia, France, Israel, and other wealthy countries. We are not an exceptionally violent nation, but criminal violence in America is much more likely to involve guns and hence be fatal.

- The widespread availability of guns in America does not cause violence, nor does it prevent violence. Generally speaking there is little statistical relationship between the prevalence of gun ownership in a jurisdiction and the overall rate of robbery, rape, domestic violence, or aggravated assault. But where gun ownership is common, the violence is more likely to involve guns and hence be more deadly than in jurisdictions where guns are scarcer. In place of the old bumper strip, we’d say: “Guns don’t kill people, they just make it real easy.”

- The primary goal of gun regulation is to save lives by separating guns and violence. Federal and state laws regulate who is allowed to possess them, the circumstances under which they can be carried and discharged in public, certain design features, the record-keeping required when they are transferred, and the penalties for criminal use. The goal is to make it less likely that criminal assailants will use a gun. The evidence is clear that some of these regulations are effective and do save lives.

- Gun violence can also be reduced by reducing overall violence rates. Gun violence represents the intersection of guns and violence. Effective action to strengthen our mental health, education, and criminal justice systems would reduce intentional violence rates across the board, including gun violence (both suicide and criminal assault). But there is no sense in the assertion that we should combat the causes of violence instead of regulating guns. The two approaches are quite distinct and both important.

Kristin A. Goss is Associate Professor of Public Policy and Political Science at Duke University. She is the author of Disarmed: The Missing Movement for Gun Control in America. Philip J. Cook is ITT/Terry Sanford Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics and Sociology at Duke University. He is the co-author (with Jens Ludwig) of Gun Violence: The Real Costs. Kristen A. Goss and Philip J. Cook are co-authors of The Gun Debate: What Everyone Needs to Know®.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Eight facts about the gun debate in the United States appeared first on OUPblog.

At the

Daily Beast, Cliff Schechter has a piece titled

"How the NRA Enables Massacres", which, despite some hyperbolic language, is worth reading for the general information, as is his piece on

a visit to the recent NRA convention. Schechter isn't reporting anything new, and the pieces are superficial compared to some earlier writings on all this, but it's always worth reminding ourselves that gun massacres in the US are part of a culture that has been carefully manufactured, protected, nurtured, enflamed.

I've written a lot about guns and gun culture here over the past few years. Writing those posts from scratch now, I would change occasional wording in some of them, clarify a few points, etc. (the hazards of writing on the fly), but you could take almost anything I've written previously and apply it to

the latest massacre.

The place of hegemonic masculinity in this type of event is

especially clear this time, but it's been present before and is a common component to why this sort of thing happens. It's a racialized hegemonic masculinity, too, the deadly scream of the angry white man — a sense of entitlement thwarted. In the book

Angry White Men: American Masculinity at the End of an Era, Michael Kimmel writes: "As men experience it, masculinity may not be the experience of power. But it is the experience of

entitlement to power" (185).

The NRA and the gun manufacturers have become experts at stoking that sense of entitlement and profiting off of it. At every possible moment, the NRA, the manufacturers, and their minions point out as many threats to power as they can imagine, and then they offer their commodities as tools for stabilizing and strengthening that power.

The patterns have been in play at least since the 1980s. James William Gibson's

Warrior Dreams: Paramilitary Culture in Post-Vietnam America was published 20 years ago, but it's at least as relevant today as it was then. Consider, for instance, his discussion of mass murderers:

Although several of these paramilitary killers went after former co-workers and bosses, and some even killed their families, most targeted a distinct social group... Thus, Huberty seems to have considered the Latinos at the San Ysidro McDonald's to be Vietnamese. Patrick Purdy was found to have been a white supremacist; his choice of Asian schoolchildren was not an accident. Canadian Marc Lepine shot only women. (237)

Gibson's chapter "Bad Men and Bad Guns: The Symbolic Politics of Gun Control" is useful reading for these conversations, and reminds us of the deep history here. Most importantly, it helps show why so many past efforts have been ineffective (though profitable for both the NRA and the gun control organizations). What would have stopped the mass shootings? he wonders. Most of the proposed and enacted legislation would not have. A more accessible and effective mental health system might have helped in some cases. But:

Most of all, stopping the madmen would have required understanding that they were not isolated "deviants" who simply invented their mayhem out of thin air and looked and acted completely differently from the "ordinary" people in the mainstream of American culture. On the contrary, in their killings they gave expression to some of the most basic cultural dynamics of the decade — in the face of either real or imaginary problems, declare an enemy responsible and go to war....

To argue, then, that many of these murderers could have been stopped solely by increased gun control is to pretend that the social and political crises of post-Vietnam America never occurred and that the New War did not develop as the major way of overcoming those disasters. Paramilitary culture made military-style rifles desirable, and legislation cannot ban a culture. The gun-control debate was but the worst kind of fetishism, in which focusing on a part of the dreadful reality of the decade — combat weapons — became a substitute for confronting what America had become. (263-264)

A year after Gibson's book was published, Timothy McVeigh

drove to Oklahoma City and showed exactly what the angry white male paramilitary culture stood for.

Siege imagery pervades and energizes that culture, as

demonstrated with the Cliven Bundy affair. One shift it has taken after the end of the Cold War is toward a more general apocalypticism. Instead of yearning for war with the Russians, now the paramilitarists yearn for the breakdown of contemporary society. Like the world's most overzealous Boy Scouts, they are

prepared. This is a power fantasy and a religious fantasy: all the "bad" people will be wiped from the Earth, and the "good" people (prepared, armed, ready) will inherit it and thrive. Or something. The details of eschatology don't matter as much as the process of preparation, because that process is a way of reclaiming some sense of power and protecting a feeling of entitlement:

I will survive because I deserve to. There's also a sense of revenge in apocalyptic yearning, too:

Once the apocalypse comes, you'll no longer be able to laugh at me, dismiss me, devalue me. You'll need me, because I will be ready and you will be miserable.What's really under siege is the sense of entitlement. That sense is part of a mythology, one killers feed on. Here's part of

a conversation between Bill Moyers and the historian Richard Slotkin, whose work has done a lot to delineate the history of the murderous mythology:

RICHARD SLOTKIN: We produce the lone killer. That is to say the lone killer is trying to validate himself or herself in terms of the, I would call the historical mythology, of our society, wants to place himself in relation to meaningful events in the past that lead up to the present.

BILL MOYERS: You say “or her”, but the fact of the matter is all of these killers lately have been males.

RICHARD SLOTKIN: Yes, yeah, pretty much always are.

BILL MOYERS: And most of them white?

RICHARD SLOTKIN: Yeah. Yeah, I think, again this is because each case is different, but the tendency that you've pointed out is true and I've always felt that it has something to do, in many cases, with a sense of lost privilege, that men and white men in the society feel their position to be imperiled and their status called into question. And one way to deal with an attack on your status in our society is to strike out violently.

American gun culture has always been racialized and gendered. From later in the conversation with Slotkin:

RICHARD SLOTKIN: ...And Colt-- one of Colt's original marketing ploys was to market it to slave owners. Here you are, a lone white man, overseer or slave owner, surrounded by black people. Suppose your slaves should rise up against you. Well, if you've got a pair of Colt's pistols in your pocket, you are equal to twelve slaves. And that's “The Equalizer,” that it's not all men are created equal by their nature. It's that I am more equal than others because I've got extra shots in my gun.

BILL MOYERS: But you write about something you call “the equalizer fallacy.”

RICHARD SLOTKIN: Yes, the equalizer doesn't produce equality. What it produces is privilege. If I have six shots in my gun and you've got one, I can outvote you by five shots. Any man better armed than his neighbors is a majority of one.

And that's the equalizer fallacy. It goes to this notion that the gun is the guarantor of our liberties. We're a nation of laws, laws are the guarantors of our liberties. If your rights depend on your possession of a firearm, then your rights end when you meet somebody with more bullets or who's a better shot or is meaner than you are.

BILL MOYERS: And yet the myth holds--

RICHARD SLOTKIN: And yet--

BILL MOYERS: --stronger than the reality?

RICHARD SLOTKIN: Well, yes, the myth holds. And it is stronger than the reality. Because those guns, particularly the Colt is associated with one of the most active phases and most interesting phases of expansion. And therefore it has the magic of the tool, the gun that won the west, the gun that equalized, the whites and the Indians, the guns that created the American democracy and made equality possible.

The angry white men may be a minority of gun owners, and just one of the audiences for the NRA and the manufacturers, but they are the audience most valued, because they are the people who will keep buying no matter what, the people who will, from fear and anger, amass a hoard of deadly tools. The NRA and the manufacturers have cultivated that audience, have encouraged that fear and anger, and have profited greatly from the murders. We should give no credence to their crocodile tears; every massacre means they can return to their favorite profit lines:

Now the liberals and feminists and Obama-lovers will come for your guns. Now you will lose your power. Now you will be robbed of what you deserve. Stock up. Prepare. Defend yourself. Be a man. Ready — aim — fire—

I like to look for treasures on YouTube.

It's a bit like looking for treasures at the dump. The amount of junk one must sort through is appalling. Thank heaven for decent search engines.

I want to share with you now some of my favorite YouTube goodies that I found in the last month.

1. Howard Tayler on 'Who Needs Talent?'

This is only the first part. But watch all four parts. It completely changed the way I think about writing, 'talent', and what I have potential to do.

2. Dan Wells on 'Seven Point Story Structure'.

This is an AWESOME seminar that helped me a lot. I'm a budding outliner (I used to think I was a freewriter, but I think I'm changing with age) and having only ever freewritten my entire life, I was lost as to how to begin. This helped me through. First of five parts.

3. The Definition of Steampunk

Brilliant. Just brilliant.

4. World's Fastest Gun Disarm

Because maybe one of your characters needs to be able to do this. There are tutorials, but I'm fairly certain most of us can't be as fast as this dude.

Speaking of gun tutorials: do you have a character who needs to know how to intelligently use a firearm?

5. This guy has a channel with, like, 900 videos on how to shoot a gun, for newbies. He's got stuff from the difference between smoky and smokeless powder, to reasons why not to put your thumb behind the slide on a semi-automatic... which is what the next video is about. If you want details,

this guy will give you details.

Hope something in this grab bag of a post was useful to you! Tell me about it in the comments, if you did.

hazy and humid

This cartoon is one of my thoughts about the effect of our second amendment, as interpreted by the Supreme Court. They have held that it isn't just a right for ensuring state militia power against the federal government, but provides an individual right to gun ownership. Our legislators are so cowed by NRA lobbyists that they have failed to legislate meaningful limits on gun ownership. And so the combination of the 2nd amendment right and the lack of other countervailing restrictions has made our other rights the target of abuse. The very life of citizens is at issue, as so terribly demonstrated by the murder of 20 innocent 6 and 7 year old school children at Sandy Hook. Who can exercise liberty rights when it isn't safe to even attend school or go to a mall or otherwise live in America. What pursuit of happiness exists, other than the happiness of a warm gun? For those of us who do not enjoy gun ownership, we are left without the same freedoms.

The very suggestion that everyone needs to own a gun, that schools should have armed guards, that more guns are the solution to the unacceptable gun violence is total insanity. This

opinion by Fareed Zakaria does a good job of explaining.

20 little children killed in one morning, along with the 6 adults at the school, the very disturbed young man who was the shooter and his mother--so many senseless deaths. We can only have them make sense if we now use this to fuel real debate and change.

Yesterday's massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School was the

sixteenth mass shooting in the U.S. in 2012.

Looking back on my post about

"Utopia and the Gun Culture" from January 2011, when Jared Loughner killed and wounded various people in Arizona, I find it still represents my feelings generally. A lot of people have died since then, killed by men with guns. I've already

updated that post once before, and I could have done so many more times.

Focusing on guns is not enough. Nothing in isolation is. In addition to calls for better gun control, there have been calls for better mental health services. Certainly, we need better mental health policies, and we need to stop using prisons as our de facto mental institutions, but that's at best vaguely relevant here. Plenty of mass killers wouldn't be caught by even the most intrusive psych nets, and potential killers that were would not necessarily find any treatment helpful. Depending on the scope and nuance of the effort, there could be civil rights violations, false diagnoses, and general panic. (Are you living next door to a potential mass killer? Is your neighbor loud and aggressive? Quiet and introverted? Conspicuously normal? Beware! Better report them to the FBI...)

That said, I expect there are things that could be done, systems that could be improved, creative and useful ideas that could be implemented. I'd actually want to broaden the scope beyond just mental health and toward a strengthening of social services in general. I'm on the board of my local domestic violence/sexual assault crisis center, where demand for our services is up, but we're hurting for resources and have had to curtail and strictly prioritize some of those services. It's a story common among many of our peers not just in the world of anti-violence/abuse programs, but in the nonprofit social service sector as a whole.

What we have is a bit of a gun control problem, a bit more of a social services problem, and a lot of a cultural problem.

One of the best books I've encountered on this subject is James William Gibson's

Warrior Dreams: Paramilitary Culture in Post-Vietnam America. It's from 1994, but is in some ways even more relevant now.

Gibson ends a chapter called "Bad Men and Bad Guns: The Symbolic Politics of Gun Control" with these words:

To argue ... that many of these murderers could have been stopped solely by increased gun control is to pretend that the social and political crises of post-Vietnam America never occurred and that the New War did not develop as the major way of overcoming those disasters. Paramilitary culture made military-style rifles desirable, and legislation cannot ban a culture. The gun-control debate was but the worst kind of fetishism, in which focusing on a part of the dreadful reality of the decade — combat weapons — became a substitute for confronting what America had become.

We seem to be a generally

less violent country than in the past, and yet this specific type of crime (mass killing) is on the rise.

Coverage of killers in the media certainly adds to the attraction of these acts for people who seek such glory. More broadly, mass killings such as this should cause us to consider

hegemonic masculinity, a

culture of child-killing, and the

privileges of

white male terrorists. (Those last 4 links via

Shailja Patel.) We should remember that the President who shed tears for the deaths of children in Connecticut authorized

drone strikes that have killed many times more children.

The desire to get rid of all the guns is understandable, but it is useless and counterproductive. 300 million (or more!) guns aren't going away, sales have been

strong for at least 10 years, with at least 1 million guns sold legally every month (good luck finding reliable statistics on illegal guns).

Meaningful policy needs to be pragmatic. We've got

tons of

laws already. Additionally, the utopian desire to get rid of all guns only plays into the paranoid narrative the NRA uses to keep fundraising strong: "The liberals want to take your guns! Send us money to stop them! Meanwhile, stockpile because the liberals always win and they're going to ban all gun sales next week!"

Many people have called for a renewal of the

assault weapons ban. I expect the gun manufacturers would be thrilled. First, because it would incite panic buying. Second, because it's primarily based on particular rifles' aesthetics, and the last time the ban was in place, the manufacturers found easy loopholes. So they get the best of all possible worlds: increased demand, which allows them to raise prices on items they've already manufactured, and then relatively easy design changes that don't cost them a whole lot of money and still allow them to sell lots of guns. Indeed, if anything, the ban increases the aura around such weapons, making them even more desireable to would-be killers. The NRA would love it, too, because they would finally be able to pin some actual gun control measures on the Obama administration, and their fundraising would skyrocket. They'd never say it publicly, but the gun industry and the gun lobby might as well stand there just waiting for the assault weapons ban to be renewed, saying, "Go ahead. Make our day."

Probably the most practically effective part of the ban has nothing to do with the guns themselves, but rather how much ammo they can hold before reloading: the magazine capacity limits. Ban all magazines beyond a certain capacity and no matter how scary the gun looks or how light the trigger action is, it's not going to be able to fire lots of bullets. To control guns in the US most effectively may mean controlling not the guns themselves so much as their components and ammunition.

Which brings us to a worthwhile question: What sort of practical gun policies might have prevented what happened in Newtown, Connecticut? The sad, frustrating answer seems to be: maybe none. Even a fantastically perfect system for preventing potentially mentally ill people from buying guns wouldn't have worked: the killer used his

mother's guns. She bought them legally. She could, presumably, pass any background check. I'm all for better funding and implementation for the background check system, but let's not pretend it would have done anything in this case.

What about bans on high-capacity magazines? That has more potential. Such magazines would still exist, so the effect of a ban would not be immediate. It would have been entirely possible for the killer's mother to have some high-capacity mags that she'd bought some time before the ban, or bought second-hand. There are hundreds of thousands, or perhaps millions, of such magazines out there. Even a draconian confiscation system wouldn't eradicate all banned magazines; it would create a black market. Still, we know from experience that high-capacity magazine bans do generally cause prices to rise and supply to fall.

Then there are the arguments from the other side of the issue:

More guns! If you don't regularly spend your time among the core gun-rights-at-all-costs activists, you might think such a suggestion is a joke. It's not. It's the only direction in which the absolutist philosophy of the NRA, Gun Owners of America, and similar groups can go. And there's a core of a truth-like substance to it: crime rates generally have been falling. (But individual gun ownership

may also be falling.) The fundamental problem with the MORE GUNS! argument is that it is based on a wild west mystique that assumes far too much competence among people in crisis moments and ignores how easy it is for mistakes to become deadly when guns are involved. Even if the premises of the argument were reasonable and desireable, it doesn't take a lot of deep thought for the practicalities to show their problems.

That's not to say that people don't successfully defend themselves with guns, or

reduce the number of casualties in some situations, or even that the presence of guns does not deter some crimes. In plenty of such situations, though, if everyone were armed, the likelihood of the moment escalating into total, even more deadly chaos would increase. I'm completely in favor of more gun safety training (in a nation of guns, it makes sense for as many people as possible not to freak out when they encounter one), but I don't want to live in a world where everybody feels the need to be armed.

An important point to note, though, is that the current situation didn't just pop up out of nowhere. It was constructed over the course of decades, and the NRA is partly to blame. But they couldn't have done it alone.

There's

an insightful post at Talking Points Memo, a letter from a reader who, much like me, grew up in the gun culture. The reader notes the rise in popularity of military-style weaponry since the mid-1980s.

I can’t remember seeing a semi-automatic weapon of any kind at a shooting range until the mid-1980’s. Even through the early-1990’s, I don’t remember the idea of “personal defense” being a decisive factor in gun ownership. The reverse is true today: I have college-educated friends - all of whom, interestingly, came to guns in their adult lives - for whom gun ownership is unquestionably (and irreducibly) an issue of personal defense. For whom the semi-automatic rifle or pistol - with its matte-black finish, laser site, flashlight mount, and other “tactical” accoutrements - effectively circumscribe what’s meant by the word “gun.” At least one of these friends has what some folks - e.g., my fiancee, along with most of my non-gun-owning friends - might regard as an obsessive fixation on guns; a kind of paraphilia that (in its appetite for all things tactical) seems not a little bit creepy. Not “creepy” in the sense that he’s a ticking time bomb; “creepy” in the sense of…alternate reality. Let’s call it “tactical reality.”

Some of these people are my friends and acquaintances; indeed, when I inherited a gun shop and got an

FFL to sell off the inventory, I sold some of those tactical guns to my friends, the fetishists. I certainly don't think they'll go on a rampage, but I do think they live in an alternate reality — a reality my father was very much part of, where black helicopters fly over the house to spy on us, where conspiracies and threats lurk in every social crevice, and where anybody without a

bug-out bag is a moron who will die in the ever-impending apocalypse.

The TPM reader who notes this proposes the change in US culture happened sometime between 1985 and 1995. It's probably a few years earlier, but in general that seems right to me (and fits with the information and argument in

Warrior Dreams). It was in the early 1980s that my father started selling fully-automatic machine guns, then moved to primarily military-style semi-automatics after the

1986 Firearms Owners Protection Act banned the civilian ownership of new machine guns and added a lot of regulation and taxes to existing machine guns, turning them essentially into collectors' items (many cars are cheaper to buy than a legal machine gun these days). Business was very good for a while, and the threat of the assault weapons ban helped sales considerably. When the ban was in place, those guns became even more desirable — much like banned books or banned movies, once somebody says, "No, you can't have that!" then people who never wanted it before suddenly become interested.

I haven't been able to find any reliable statistics on gun sales in the 1980s (good data on gun sales isn't easy to get, for various

reasons), but 1984/1985 seems plausible as a critical mass point for the shift in gun culture — conservatives' push within the NRA to shift the organization's tone and political attitude had succeeded*, Reagan was President (the first President endorsed by the NRA), TV shows like

The A-Team and

Airwolf were popular,

G.I. Joe and other military comics were common, various paramilitary books and magazines filled newsstands, and Hollywood had started making movies like

Red Dawn and

Rambo II.

The last fact is significant. When

Dirty Harry came out in 1971, sales of the

Smith & Wesson Model 29 increased significantly. But that was just a big revolver. In 1985,

Rambo II seemed to do wonders for sales of the

H&K 94 and MP 5. Warrior guns.

It would be facile for me to end by pretending I have any easy or immediate solutions. I don't. Perhaps we need some feel-good measures, but I fear they make us think we've accomplished something when we haven't. There's a strong desire right now, it seems, to

do something. But symbolic laws and security theatre won't help us.

Here's the final paragraph of Gibson's introduction to

Warrior Dreams:Only at the surface level, then, has paramilitary culture been merely a matter of the "stupid" movies and novels consumed by the great unwashed lower-middle and working classes, or of the murderous actions of a few demented, "deviant" men. In truth, there is nothing superficial or marginal about the New War that has been fought in American popular culture since the 1970s. It is a war about basics: power, sex, race, and alienation. Contrary to the Washington Post review, Rambo was no shallow muscle man but the emblem of a movement that at the very least wanted to reverse the previous twenty years of American history and take back all the symbolic territory that had been lost. The vast proliferation of warrior fantasies represented an attempt to reaffirm the national identity. But it was also a larger volcanic upheaval of archaic myths, an outcropping whose entire structural formation plunges into deep historical, cultural, and psychological territories. These territories have kept us chained to war as a way of life; they have infused individual men, national political and military leaders, and society with a deep attraction to both imaginary and real violence. This terrain must be explored, mapped, and understood if it is ever to be transformed.

---------------------------------------

*

Jill Lepore in The New Yorker sums up the change:

In the nineteen-seventies, the N.R.A. began advancing the argument that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual’s right to carry a gun, rather than the people’s right to form armed militias to provide for the common defense. Fights over rights are effective at getting out the vote. Describing gun-safety legislation as an attack on a constitutional right gave conservatives a power at the polls that, at the time, the movement lacked. Opposing gun control was also consistent with a larger anti-regulation, libertarian, and anti-government conservative agenda. In 1975, the N.R.A. created a lobbying arm, the Institute for Legislative Action, headed by Harlon Bronson Carter, an award-winning marksman and a former chief of the U.S. Border Control. But then the N.R.A.’s leadership decided to back out of politics and move the organization’s headquarters to Colorado Springs, where a new recreational-shooting facility was to be built. Eighty members of the N.R.A.’s staff, including Carter, were ousted. In 1977, the N.R.A.’s annual meeting, usually held in Washington, was moved to Cincinnati, in protest of the city’s recent gun-control laws. Conservatives within the organization, led by Carter, staged what has come to be called the Cincinnati Revolt. The bylaws were rewritten and the old guard was pushed out. Instead of moving to Colorado, the N.R.A. stayed in D.C., where a new motto was displayed: “The Right of the People to Keep and Bear Arms Shall Not Be Infringed.”

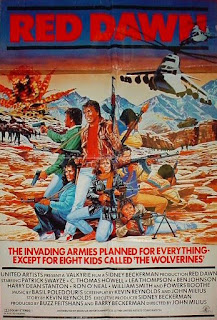

The question is not whether

Red Dawn is a good movie. It is a bad movie. As the crazed ghost of

Louis Althusser might say, it has always already been a bad movie. The question is: What kind of bad movie is it?

(Aside: The question I have received most frequently when I've told people I went to see

Red Dawn was actually: "Does Chris Hemsworth take off his shirt?" The answer, I'm sorry to say, is no. All of the characters remain pretty scrupulously clothed through the film. The movie's rated PG-13, a designation

significant to its predecessor, so all it can do is show a lot of carnage, not carnality. May I suggest

Google Images?)

My companion and I found

Red Dawn to be an entertaining bad movie. I feel no shame in admitting that the film entertained me; I'm against, in principal, the concept of "guilty pleasures" and am not much interested in shaming anybody for what are superficial, even autonomic, joys. (That doesn't mean we can't examine our joys and pleasures.) No generally-well-intentioned, "diversity"-loving, pinko commie bourgeois armchair lefty like me can go into a movie like

Red Dawn and expect to see a nuanced study of geopolitics. I knew what I was in for. I got what I expected: a right-wing action-adventure movie based on a

yellow peril premise.

Red Dawn is an unironic remake of a

1984 movie predicated on paranoid right-wing fantasies; it's not aspiring to even the most basic

Starship Troopers-levels of intertextuality and metacommentary. There's none of the winking at the audiences that fills so many other 1980s remakes and homages (e.g.

Expendables 2, which relies on the audience's knowledge of its stars' greatest hits — the only convincing performance in the movie is that of Jean-Claude van Damme, who, apparently overjoyed to be released from the purgatory of straight-to-DVD movies, plays it all for real, and becomes the only element of any interest in the whole thing). The closest

Red Dawn comes to acknowledging its position in the cinemasphere happens when it turns the first film's very serious male-bonding moment of drinking deer blood into a practical joke, giving the characters a few rare laughs.

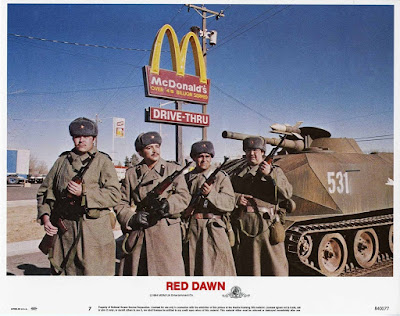

What are we supposed to feel good about in this movie? The 1984

Red Dawn was not even remotely a feel-good movie, but it gave us a space in which to feel proud of an idea of America that could survive even the most devastating attack by the Soviet Union (and its Latin American minions). It made a point of showing concrete objective correlatives for the abstract idea that is "American freedom" — the one that was most impressed on me by my father when we first watched

Red Dawn together was the scene where Soviet soldiers talk about going to a gun shop to collect the federal

Form 4473s, and using them to track down gun owners. This, to my father and many other people, demonstrated exactly why even the most minimal type of registration of guns is not merely annoying, but a threat to freedom. I vividly remember

my father saying, "If the Russians come, we burn those damn forms."

Red Dawn was not merely an action movie; it was a documentary.

But

Red Dawn was a movie made during a time when the U.S. was not officially at war. It appeared in U.S. theatres less than a year after the

invasion of Grenada, and just at the time when the actions that would eventually become the

Iran-Contra Scandal were making their way into the public consciousness. The hawks of the Reagan administration needed the public to be both patriotic and fearful of the Red Menace, because otherwise it was difficult to justify the massive transfer of wealth into the Pentagon.

Red Dawn did that better than any other movie of the time. (For much more on this background, see the article by J. Hoberman in the Nov/Dec 2012 issue of

Film Comment.)

Now, though? The new

Red Dawn comes as the Iraq war is winding down and the war in Afghanistan (our

longest) may be nearing some sort of end. (And then, of course, there's

Libya.) But these have been wars where we have been invaders fighting insurgents. They have been long, unfocused wars with no clear victory conditions. They began with some popularity and unanimity of public opinion, but the longer they went on, and the more that people learned about them, the less popular they became. They continued because the U.S. military is, while a huge part of the national budget, not a particularly concrete and visible part of everyday life and concern for many Americans. Without the threat of a draft, and with the rise of long-distance and drone strikes, most Americans can ignore the immediate reality of American wars, the hundreds of thousands of deaths and injuries on every side.

It's in what the new

Red Dawn makes us attach our feelings of pride, joy, and power to that it really differs from its predecessor, because the idea of America that it presents is neither particularly clear nor the product of much conviction. There are flags and some general genuflecting in the direction of "freedom", but the original

Red Dawn offered a vision of how its idea of "freedom" actually works in the world, and what threatens it. There was an attempt at creating a certain amount of plausibility and verisimilitude — one of the advisors to the original film was

Alexander Haig, Reagan's former Secretary of State, who worked with writer/director

John Milius to craft what seemed to them a relatively realistic invasion scenario, the weapons and vehicles were as realistic as could be accomplished without being able to buy actually Soviet weaponry (the CIA inquired about the tanks after seeing them being moved to the set; later, the Pentagon used images of them to train the guidance systems in spy planes), and the tone is dark, with war presented as hell for both sides. Milius made numerous references to his masculine hero Theodore Roosevelt, and the vision he presented was stark, painful, and apocalyptic, more

Hobbesian than

Amurrican. It was

Panic in Year Zero! by way of

The Battle of Algiers.Ours is the Age of the Tea Party, not the Age of Reagan, and so the new

Red Dawn is closer to the ideological vision of

The Patriot than that of its original source.

The Patriot is the story of a man in Colonial America who doesn't see much point in fighting against the British until his own family is affected, at which time he becomes a psychopathic vengeance machine, and then at the end returns home to a small community not to help build up a new government or create the idea of a common United States, but to become the leader of a little utopian plantation. (He had already been leader of a utopian plantation before the war, because the black people doing work on his property were not actually slaves, but free employees. Really. As William Ross St. George, Jr. wrote in his

review (PDF) of the film for the

Journal of American History, this must have been "the only such labor arrangement in colonial South Carolina".) What matters in

The Patriot is not country or government — all government is portrayed with contempt in the film — but rather self-reliance and, especially, family. Despite the movie's title, it's not about being a patriot, but about being a loyal, strong, independent, and avenging father.

The new

Red Dawn, much more than the original, is also a movie about families and fathers. Jed, played originally by Patrick Swayze and in the new film by Thor, is now an Iraq vet who struggled to be a good son to his father and, especially, a good brother to Matt (originally Charlie Sheen, now Josh Peck). Lots of family melodrama is alluded to. The boys don't visit their father in a re-education camp; instead, the Evil Korean Guy (whose name I thought was Captain Joe, but IMDB tells me it's Captain Cho. I prefer my version), who for some unfathomable reason recognizes from the very first moment that Teenagers Are The Enemy (he was probably a high school teacher back home), rounds up their fathers, brings them to the Evil Dead Cabin where the kids had been hiding out, and makes the fathers plead with the kids to come in. Of course, the weak and collaborating mayor pleads with them to give themselves up, but the strong and noble father of Jedmatt (in a much blander performance than the clearly unhinged and perhaps psychopathic man portrayed by Harry Dean Stanton in the original) instead tells them to fight to the death, causing Captain Joe to channel his inner

Nguyen Ngoc Loan and shoot him in the head. Oh dad, poor dad. Jed and Matt then go on to learn how to be good brothers to each other, just in time for— Well, you don't want to know the ending, do you? (For a moment, I thought it would turn out to be a movie climaxing with brotherly kisses and fellatio, but, alas, it did not. Well, not exactly. Although the more I think about it...)

We have to talk about the ending, though, because we have to talk about who lives and who dies. The original

Red Dawn was not

Rambo — while it certainly stirred up feelings of patriotism against the Soviet enemy, and admiration for the U.S. military, its tone isn't all that far away from

The Day After. The end is a downer, but it's not nihilistic. We zoom in on a memorial plaque, its words read to us on the soundtrack: "In the early days of World War III, guerrillas, mostly children, placed the names of their lost upon this rock. They fought here alone and gave up their lives, 'so that this nation shall not perish from the earth.'" The memorial asserts that these lives were lost for a great cause, and by quoting the Gettysburg Address, it connects their sacrifice to that of soldiers who fought to preserve not just some idea of Americanism, but the union itself.

The remake turns patriotic tragedy into personal tragedy — Jed is killed just at the moment when he has reconciled with his brother. Toni (

Adrianne Palicki in the remake,

Jennifer Grey in the original) and Matt both survive in this version, along with many of the other Wolverines. Well, the white Wolverines.

The new

Red Dawn isn't just a yellow peril movie, it's a vision of white supremacy. Only one nonwhite Wolverine has much of an identity (Daryl, played by

Connor Cruise), and the others die pretty quickly. Finally, Daryl is, without his knowledge, injected with some sort of tracking device that can't be removed from his body, so he's given some supplies and left to wander away, probably to be killed by the North Koreans. Almost all of the white Wolverines survive, presumably with a new understanding of the miraculous powers of their skin color.

Remember what happened to (white) Daryl in 1984? His sleazy father (the mayor) forced him to swallow a tracking device. He knew it was in him. After barely surviving the assault that followed, the Wolverines take him to the top of a freezing mesa with a captured Russian soldier and get ready to execute him. Jed and Matt fight about it, with Matt saying it will make them worse than the Russians. Jed kills the Soviet soldier, but doesn't seem to be able to kill Daryl. Robert, whose experiences have fully brutalized him, shoots Daryl. It's a wrenching, disturbing scene. Again and again, the original

Red Dawn says: War is a horrific, destructive experience for everyone involved, and it reduces us to our most animalistic natures — naming the guerrillas

Wolverines was not merely the naming of a mascot or a rallying cry, it was a statement of what they had become.

The new