Here are three types of story arcs: change, failed, and static.

http://www.adventuresinyapublishing.com/2016/10/solving-fiction-problems-three-kinds-of.html#.WAuJGeArJlY

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Plot, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 298

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, Add a tag

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, Add a tag

Create a roadmap of the scenes in your book to make sure it all works together.

http://www.adventuresinyapublishing.com/2016/07/martina-boone-on-mapping-your-book-to.html#.V4kbzrgrJlY

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, Add a tag

For a great plot twist at the end of the story, you need to provide clues and misdirections along the way.

http://www.katemessner.com/teachers-write-7-19-16-tuesday-quick-write-with-kat-yeh/

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, Add a tag

All the elements for your plot twist have to already have appeared in your manuscript.

https://warriorwriters.wordpress.com/2016/05/25/how-to-write-mind-blowing-plot-twists-twisting-is-not-twerking/

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: nonfiction, plot, Add a tag

Just because you're writing nonfiction, doesn't mean you can get away without a story arc.

https://eerdlings.com/2016/04/28/greatest-hits-four-tips-for-writing-nonfiction-plots/

Blog: Kidlit Contest (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing, Advice, Character, Plot, World Building, Add a tag

I’ve worked with a few manuscripts recently where the writers established and then promptly forgot about important threads. In my book, I talk about shining a spotlight. If something is important, it’s your job as a writer to shine the spotlight on it. You pick where to aim that light, and how bright it is.

What do I mean about dropping threads? Well, let’s say that your character is a musician. They speak in musical metaphors and seem to see the world through a Beautiful Mind-esque musical lens. Until this fades from the manuscript about a third of the way through. And music doesn’t really factor into the plot itself.

I often see this in manuscripts. Just like voice sometimes fades in and out (the writer is focusing on voice when they’re writing certain passages, then they shift focus to something else and the narrative tone changes), so do various other elements of novel craft.

Character attributes (musicality), secondary characters (a supposed best friend disappears for 50 pages and nobody thinks anything of it), world-building elements (the world is on the brink of war and yet there’s no danger or news of danger in the middle of a story), and plot points (the character says their objective is to seek something, then they get wrapped up in a romance and the desired object seems to fade into the background) can all be lost in the shuffle.

Your job as a writer is to analyze your story and see if you’re dropping any threads. Are you swearing up and down that something is important, then abandoning it? Does everything that’s vital to the story and introduced at the beginning wrap up by the end? Do all of the important elements get some kind of closure?

This is a common note that I give. “Whatever happened to XYZ?” Make sure your story feels cohesive from beginning to end, leaving nothing/nobody of note behind.

Add a CommentBlog: Notes from the Slushpile (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Learning, Plot, Structure, Pacing, Margo Lanagan, confessions, Michelle Magorian, Bernard Beckett, Sarah Waters, Jo Wyton, Elizabeth Wein, Amy Butler Greenfield, Add a tag

Writing exists around that other time-consuming thing in my life: a full time job. And I love my job, so that’s OK by me.

But is does mean that when I come to work on a manuscript, I feel under pressure to do something Great with it.

I jump right in. Maybe I re-read the last few paragraphs I wrote, maybe I just get on with it. Maybe I pick up an existing scene, maybe I write a new one. Maybe it’s planned, maybe it’s not.

Whilst I have usually planned the plot out, I have always been someone more comfortable with winging it than properly planning it.

And that’s fine, except that I was reading Candy Gourlay’s post from a few weeks ago and felt the need to try to do things a little differently.

Why don’t I plan more? Is it because it doesn’t work for me, or because in the limited time I have I prioritise the writing itself? Or is it – gulp – because I’ve never taken the time to learn how?

In an odd turn of events, I currently have the time, and it’s coincided wonderfully with having the inclination. Sitting next to me on my desk: Story by Robert McKee, Writing Children’s Fiction by Yvonne Coppard and Linda Newbery (from whom I have already been lucky enough to glean pearls of wisdom and kindness generously gifted on an Arvon course), On Writing by Stephen King and Reading Like a Writer by Francine Prose.

Just as importantly I have surrounded myself by my favourite books, and have gone through each wondering for the first time why exactly they stick in my mind as favourites. Michelle Magorian's Goodnight Mister Tom and Elizabeth Wein's Code Name Verity for the depth of friendship invoked, Margo Lanagan's Tender Morsels and Bernard Beckett's August for their wondrous use of language, Amy Butler Greenfield's Chantress for its use of setting to reflect the characters perfectly – the list goes on.

Reading these books again and trying to break them down goes against instinct, but as Sarah Waters wrote in a 2010 Guardian article, “Read like mad. But try to do it analytically – which can be hard, because the better and more compelling a novel is, the less conscious you will be of its devices. It’s worth trying to figure those devices out, however: they might come in useful in your own work.”

Diving head-first into learning how to write better, rather than spending the time writing the manuscript itself, feels somewhat intimidating, but cometh the time, cometh the writer. Probably.

Blog: Kidlit Contest (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Interiority, Writing, Advice, Character, Plot, Add a tag

This is a great question that came via email from Matt:

Is there a writing principle about how much interiority should be within a scene?

As with all great writing debates, I’m here to say that there’s no set guideline. Womp womp. Sorry to not have something more concrete, but I do have some food for thought that might help you choose your own approach.

My rule of thumb, however, is to use what’s necessary and find a balance. As with anything, balance doesn’t come easily. Some writers err on the side of too much interiority, some writers barely scratch the surface of their character’s rich inner lives, even in first person.

The imbalance of too much interiority is especially apparent when nothing is happening, plot-wise. Alternately, nothing happens because there’s too much interiority, or internal conflict, rather than external conflict. If you have your character thinking about everything, maybe you’re on this end of the spectrum. Know that, while a level of interiority is desirable, you also need to focus on the things that come less naturally to you, namely pacing and plot. It’s very important to know how a character reacts to what’s happening, but it can’t be the end-all and be-all. To be fair, I see this imbalance less than its opposite.

The more common imbalance is seeing little interiority in big moments, when connection to the character should naturally increase in order to keep from alienating the reader. Writers who fall into this category tend to be very comfortable with plot. When they do talk about emotion, maybe they simply name what a character is feeling, or talk about the feelings by using clichés that detail emotions in a character’s body. These are offshoots of telling, and, as you’ve heard me say many times, interiority is quite different from telling, though the distinction can be subtle for a lot of people. Characters with too little interiority are also prone to being stuck, or to being in denial.

As you can see, there are many more links discussing a lack of interiority or issues with inadequate interiority than there are dealing with too much of it. This is yet another reflection of the fact that I see writers end up toward this end of the issue a lot more.

If that’s not the case for you, and you think you’re somewhere in the middle as an interiority-user, I would still suggest analyzing how you’re striking that balance. Make sure the reader feels connected to important moment, and use enough interiority to highlight the things that are truly important. When something big happens that your character should be reacting to, ask yourself: And? So? Some recent thoughts questions that help develop interiority can be found here.

Next, think about how interiority and plot intersect. Use interiority to plant the seeds of tension as you develop your plot. It’s not enough to have a character feel afraid, for example. They’re usually afraid of something very specific, or a worst case scenario. To help tension along, let their minds go to those darker places, especially if the plot hasn’t caught up yet. More thoughts on that here.

This is such an important facet of the fiction writing craft that I really hope you never stop exploring this fascinating topic, and figuring out how to best use this tool.

Add a CommentBlog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: nonfiction, plot, Add a tag

Here are some things to consider when deciding how to plot your nonfiction book.

http://eerdlings.com/2015/11/12/from-the-editors-desk-four-tips-for-writing-nonfiction-plots/

Blog: Pub(lishing) Crawl (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Plot, Structure, Jane Austen, Outlining, Drafting, Middles, Pride & Prejudice, Beginner Resources, Writers Toolbox, Add a tag

A couple of months ago, I wrote a post about Inciting Incidents that seemed to be helpful for a lot of our readers at PubCrawl, and I’ve had a few requests to continue dissecting story beats. So I’ve decided to tackle the next one on my list: The Midpoint.

I know a lot of writers struggle with middles, but I’m actually not one of them. For me, the middle of the novel is simply an extension of the beginning, and in fact, I tend to think of my books more or less in halves: the beginning, and then the end. The point that delineates the beginning from the end is the midpoint.

First of all, let me say: there is no wrong way to write a novel. Write however works best for you. For me, my stories tend to naturally structure themselves into four acts, with three inflection points: Revelation (end of Act I), Realization (end of Act II), and Resolution (end of Act III). The Realization (end of Act II) generally tends to be my Midpoint.1

So what is the Midpoint, exactly? Why is it given such emphasis in all these story structure/plot books? I mean, a middle is just the boring bridge between the opening and the ending, right?

Personally, for me, the Midpoint is the moment of greatest change; in fact, I would argue it is the top of the mountain of your story arc. Everything builds up to it, and then everything unravels from it. The Midpoint is what the beginning of your novel is working towards and what the ending of your novel is working from. Because of this, I actually think the Midpoint of your novel is where your story reveals itself.

What do I mean by that? I mean that the sort of plot point/character development that is your Midpoint2 reveals the type of story you’re writing. The “point” of your book, as it were.

For example, in Pride & Prejudice, the Midpoint of the novel is when Darcy sends Lizzy a letter, explaining himself after she has turned down his offer of marriage. Until she reads his letter, Lizzy has been staunch in her prejudice against Mr. Darcy based on a bad first impression, despite mounting evidence to the contrary. Suddenly, she realizes she has interpreted all his actions incorrectly due to a mistaken pride in her own cleverness.

And there you have it, the entire point of Pride & Prejudice, as neatly summarized by the Midpoint.

The Midpoint is often referred to as a Midpoint Reversal, because there is often some sort of reversal of fortune or big twist or some other reveal that changes the entire context of the story (as in the case of Pride & Prejudice). However, not all Midpoints involve a reversal of some kind. For example, the Midpoint of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s/Sorcerer’s Stone3 is when Harry discovers just what Hogwarts has been protecting: the eponymous stone itself. And there you have it: the point of the first Harry Potter book.

All stories, regardless of how they’re structured, have Midpoints. They may not fall in the exact middle of your book, but they are in that neighborhood nonetheless. Without them, you have a “sagging middle” and, I would argue, no actual point to your story.

So there you have it: Midpoints! Are there any other story beats you guys would like for me to cover? Sound off in the comments!

- There are many, many, MANY ways to structure your novel. Traditionally, Western movies and screenplays are divided into three acts. Plays are often one or two acts. Tragedies can be five acts. Far Eastern narrative structure tends to fall into four acts. ↩

- And to be honest, the Midpoint is the one of the few places in your manuscript where the plot point and character development should be the same thing. ↩

- I HATE that the title was changed for the U.S. edition; it makes absolutely no sense to call it a “sorcerer’s stone” when a philosopher’s stone is a real thing. ↩

Blog: Kidlit Contest (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing, Advice, Plot, Etc., Description, Add a tag

Back in college, I did a few freelance articles for a photography trade magazine. Mostly wedding photographer profiles. A woman I’d become close friends with in a creative writing course happened to be an editor for this publication, and she gave me some assignments for fun. By about the third piece I turned in, she sent me a very friendly email that haunts me to this day. She basically said, “Hey Mary, I’m noticing that all of your articles follow the same pattern. You start with the photographer’s youth and then the event that made them fall in love with photography, then you cover their education and development as a photographer, and their you end with their current work. Maybe you could, yanno, mix it up a little bit.”

She was right. Of course she was. I’m no journalist and I had no idea what I was doing or how to organize a compelling non-fiction article, so I picked the easiest possible organizational strategy when talking about a person: the resume, or, in other words, “Started from the bottom, now we here.” And by golly, I was going to drive it into the ground until somebody stopped me because I didn’t know what else to do. And, to my *ahem* credit, I thanked her profusely for the feedback…and was so mortified that I stopped writing for the photography magazine shortly thereafter. A writer’s ego is a strange creature.

But I figured out the lesson in her wise words eventually. Yes, a decade, give or take, counts as “eventually,” guys. There are patterns in writing. Some are good patterns, some are individual patterns that maybe keep us from growing in the craft.

An example of a good pattern is a larger organizing principle or story theory, for example, Joseph Campbell’s hero cycle. While this is an oldie, it’s very much a goodie, since its wisdom applies to any number of stories, in any number of ways. Chronological order is also an old standard that can’t be beat when writing a novel. Sure, you want to jump back in time to fill in some backstory and context every once in a while, but moving from point A to point B as the character grows and time marches forward is an idea that will never go away.

The reason I like these two is that they’ve vague and versatile. They dictate a general idea and then it’s up to you to apply it in your own style. You’ll notice that I talk about story theory in my book, Writing Irresistible Kidlit. But I try to leave much of it up to the writer. I recently ordered a slipcover for my sectional because the upholstery we originally got clings to pet hair like it’s pirate treasure. The slipcover fabric is so stretchy that it was able to fit my couch and look custom-made without any measurement. I was dubious until it arrived, since it purported to fit couches from 66″ to 96″ and that seems like a pretty big spread. But it’s really quite amazing, fits perfectly, and now the dogs can drool and shed on it with abandon. All this is to say that I try to give writing guidelines as if I were that slipcover (stay with me here, folks, this is getting weird…). Your story is the couch. You pick its overall shape and dimensions. The organizing principle’s job is to cover it and mold to what you want to do, all while giving it a cohesive look and function.

Now, there are writing teachers out there who like to dictate patterns in much more specific terms. I’ve had many writers, believe it or not, come to me and ask, “Well, in So and So’s Story Theory, he says I have to include the inciting incident by the 5% mark, then the first conflict by 10%, then the first major loss by 25%. The cousin dies, but it’s at 27% and I don’t know what to do.” This kind of teaching-writing-with-an-iron-fist always baffles me. I like the broader, sweeping guidelines, not micromanaging a manuscript down to the nth percentile. In my world, a rigid story theory is great for people who have never written a novel before. It gives them valuable scaffolding to cling to. But once you’ve written one, and internalized some basic principles, I think most guidelines can take a backseat to how you want to tell the story.

So, basically, I like the big writing patterns. Like chronological order for a novel. Or the pattern of emotional development that I outline in my book.

But every writer has other patterns. And before you know what you should do about your patterns, if they’re helpful or hampering, you should at least become aware of them. (Hopefully without becoming mortified and quitting.) This post was inspired by a client of mine who starts many chapters in exactly the same way: scene-setting and talk of the weather. I applaud the scene-setting. Many writers who simply leap into a scene with dialogue or a plot point fail to ground the reader in time and place. But this pattern for this writer was almost formulaic. Weather. Scene. Then the chapter starts. Over and over.

What happens when a reader detects an underlying pattern in your work is they become less engaged. By the fifth weather/scene/start chapter, I’m going to check out at the beginning a little bit. Unless the descriptions of the weather are building up to something massive (it’s a book about a big storm, or a person with weather-related superpowers), there needs to be variety. The pattern cannot take over the narrative.

This reminds me of picture book writers who are working in rhyme. Sometimes I see writers twisting their syntax into crazy sentence pretzels just so they can make a line rhyme. This begs the question: Is the story in the service of the rhyme, or the other way around? You always want to be putting the story first. If you find that writing in rhyme warps your natural voice, makes you write like a Victorian schoolmarm, and leads to all sorts of other problems, then it’s the pattern that needs to go, and you need to free yourself up to tell the story the best way you can. Patterns. They’re all around. Sometimes they’re good, sometimes they’re hindrances.

What are your specific writing patterns? Are you trying to break them or are you working with them? Discuss.

Add a CommentBlog: Kidlit Contest (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing, Advice, Character, Plot, Tension, Stakes, Add a tag

Don’t worry, this isn’t a post about dress code for writers. If there was such a thing, 3/4 of my wardrobe would be out the window. I’m basically in my pajamas right now, with an additional layer of dog hair to make the outfit fancy. This is a post inspired by several editorial client manuscripts where I’m noticing characters going about their business with an overall lack of tension. This post builds on the idea introduced in last week’s post, about making subtle changes that could yield more tension. If you haven’t read that one, go check it out, then read on here.

You don’t want a character who is freaking out all the time, because that will be exhausting. They care too much about everything, and everything is a big deal. if you find yourself with this type of character on your hands, this is going to backfire pretty quickly. If everything is at a level 11, you lose the ability to make it matter after a while due to the Law of Diminishing Returns. As they say in The Incredibles, “If everyone is special, then no one is.”

That leaves us with a character who doesn’t care as much as they could. They are too casual. There are two ways to be too casual: about things that don’t matter, and about things that do. You may have one of these characters if people have told you that they’re having a hard time relating to the story or getting worked up about its events. If you’ve received the comment that your readers are having trouble caring.

First, your issue could be a character who is mellow in a mellow situation. For example, a character named Jane is about to take a test. It could go like this:

There was an exam coming up in pre-calc. Whatever. Not only did she have no plans to ever touch a math textbook again, but the teacher had offered to drop everyone’s lowest test grade. Jane didn’t even break a sweat, and went back to scribbling in her art notebook.

If Jane doesn’t care, why should we? The outcome doesn’t matter, she doesn’t seem at all worried, it’s a non-issue. The fix would be to make Jane care, even a little bit. Even if she wants to seem like she doesn’t. Inject tension into how Jane feels versus how she’s behaving. Compare this example to the original:

Jane scribbled in her art notebook but she couldn’t help watching the clock out the corner of her eye. Pre-calc was coming up, and that damn midterm. Whatever. At least that’s what she tried to think. Even though she didn’t care about math, her mom would. And she didn’t want to fail, because that meant more math practice, maybe a tutor. Jane sighed and stopped drawing. Maybe she could cram a few more minutes of studying in. Everyone else was doing it.

Here, we get a subtle shift in Jane’s thinking. She really doesn’t care, but there’s tension now because she won’t let herself fail the exam on principle. Whatever her real reasons are, there’s now a little battle going on. She feels conflicted. There’s tension. Jane’s overall stance on the exam hasn’t changed–it hasn’t suddenly become the Everest of her high school career. But at least she cares now, and notice also that the very fact that she does care bothers her. Or she feels like she’s forced to care. Either way, there are multiple layers of tension.

Tension comes from uncertainty, fear, anxiety. With the revised example, I’ve added an undercurrent of doubt. She knows this exam isn’t the end all and be all, but she wants to do well on it anyway, and she worries she won’t. Even if a character feels confident, you can always add a shade of tension. We all have these darker feelings, even in moments of great light. Use that to your advantage. Friction means tension means stakes means reader engagement!

This brings me to my next, more obvious, idea. You can certainly dial up the tension by changing the character’s attitude toward something. Why not take it one step further and change the something to have higher stakes? Instead of blowing the exam off (too casual), she has a more complex and interesting relationship with it. If you’re not going to present the event in a layered way, why even bother describing it? You’re giving a lot of manuscript real estate to what amounts to a throwaway. Surely there are other things you could be narrating that stand to get more of a rise out of Jane. Maybe an art competition.

One of my favorite things to remind writers is that they are creating a world from scratch. They make up the characters, the events, the circumstances. If a character is bored, they are also boring the reader. If they don’t care, the reader has to struggle to latch on to the story.

If you suspect that a character is either being too casual about their circumstances or stuck in circumstances that are too casual, take control, add some small tension, and beef up the moment. Or cut or change it. But don’t let the story tension peter out. If all else fails, have them thinking about something else that’s coming up, and plant the seeds for tension down the road.

Add a CommentBlog: Pub(lishing) Crawl (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Conflict, Young Adult, Motivation, Advice, Plot, Tension, Jodi Meadows, Beginner Resources, Writers Toolbox, Add a tag

Sometimes, terrible things happen to characters. It’s just a fact of fiction.

But as authors, sometimes we want pull back before things get too awful for our sweet, precious characters. Sometimes we want to make things easy because we love them.

My dear writer friends, that is not how our characters grow. Like mama birds shoving their chicks out of the nest to make them fly, we must make everything just awful so their true potential can shine.

Here are a few ways I like to shove my character birdies out of the nest:

- Take away something they love.

- Give them something they want. Take it away.

- Make it impossible for them to have something they want because of their own action/inaction.

- Do the opposite of what they want. If they want to go right, force them left.

- Make someone else want the thing your character wants so they have to race for it.

- Give someone else the thing your character wants.

- Use one goal against another in a battle of What’s Most Important?

- Destroy the thing they want so that no one can have it. (Cackling encouraged.)

Okay, lots of my ways to ruin lives involve waving what they want in front of them—then snatching it away. That sounds really, really mean, but believe me, properly motivated characters are characters willing to take action. And the closer they get to what they want, the harder they work.

And if the thing they want is gone/impossible to get, the character might have to reach higher for a new goal— something they didn’t know they wanted until everything else was stripped away. Maybe they couldn’t see it before. Maybe their focus was divided.

Don’t limit their goals to one thing, though! Give them a few things to desire, even if they mostly take action toward one thing. Keeping loved ones safe is always a good goal. Going after their personal dreams is another good one. Family and dreams can be good at conflicting with one another. (Sometimes families want characters to be a blacksmith, but the character wants to be a candlemaker! And sometimes characters have to choose between saving the blacksmith family from a tragic goat stampede . . . and going to the chandler convention in the next town over.)

And heck, definitely use combinations of the above list. Don’t limit yourself to one trick. Push until those little character birdies fly.

How else do you like to ruin your characters’ lives motivate your characters to take action?

Blog: Kidlit Contest (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing, Motivation, Advice, Character, Plot, Revision, Add a tag

I’m working with a client on a Synopsis Overhaul right now. Quick plug: If you haven’t checked out my freelance editorial website in a while, I have added this new service, as well as Reader Reports. I won’t bulk up this post by describing them here, but they’re two great options for getting feedback on your novel’s development as or before you write it (in the case of the Synopsis Overhaul) or getting my eyes on your entire manuscript, along with comprehensive notes, but without the investment of a Full Manuscript Edit. Check them out!

There’s a proposed scene in my client’s outline that doesn’t quiiiite work. Of course, she is free to write it and see if she can make it work as she develops her draft, but I had a reservation about it. Basically, her protagonist, let’s call him Sam, does something illogical. The issue is, he has been planning this illogical move for a while. He’s a smart kid in a heavily guarded environment, and, for a smart kid in a heavily guarded environment, the plan makes no sense because he should know better, and he would get caught immediately.

But in the manuscript she’s planning, he completely ignores common sense and does his plan anyway. I told her in the synopsis edit that I didn’t buy it. The plan is so foolhardy and out of character, and so improbable in his environment, that I really would struggle believing its feasible. I called it the Improbable Thing.

In writing fiction, we create the fictive dream, right? We create a world and a character and a set of circumstances and actions that function with a certain logic. There’s enough logic there that the reader can suspend disbelief and “go there” with the story. Here, I was having trouble “going there” because my own logic kept calling out that this was too far out to believe.

My client is really attached to this plot point, and she doesn’t want to remove it from the story, which I completely understand. First of all, I’m not going to tell her to axe it at this early juncture. When I work with clients on developing a novel outline, I don’t rule anything out. They are free to write a draft of the novel as they wish, and see if it works. It’s tough to work with just an outline, because I don’t get to really see the manuscript in question. I just get to see its bones. Who knows how the final version could flesh out? But that’s what makes synopsis work exciting! It’s all about possibilities and tweaking things so that the actual manuscript comes into sharper focus.

So, if it’s not fair to say, “Yeah, cut it, it’s a disaster” at this point, then what? How do you work around a plot point or character development that seems improbable? In writing her back about whether or not to axe her beloved plot point, I had a great idea for this post.

If you’re faced with an instance in your story that people aren’t “buying” (or you’re worried they won’t buy), it’s time to think about the context. The present may still be good, but what if you put it in a different wrapper? A brilliant potential solution.

What if, in this case, Sam doesn’t plot the Improbable Thing in advance? He wants to accomplish XYZ, but he doesn’t think that it’s possible. Then, he is in the right place at the right time, and the opportunity to do an Improbable Thing comes up. He only has an instant to think, and so he thinks, “What if this is crazy enough to work?” This could be just the new context my client needs. It accomplishes two things:

First, it adds a layer of impulsiveness to the Improbable Thing. It wouldn’t have worked as a plan, because it makes no sense as a plan (too many holes). But it could totally be sold as a last-ditch, impulsive, emotional effort, and I’d buy it because if Sam is being impulsive, then he’s not thinking clearly.

Second, if Sam is right there saying, “This is too crazy to work, but I have no other choice,” then the reader feels reassured. We see him questioning it, right as we’re questioning it, so the reader and protagonist are on the exact same page! We’re a team! Nobody thinks this could work, which opens up the possibility that…well…maybe it could! It’s that leap that will help the reader suspend disbelief. And then I’m “going there” with Sam instead of rejecting the Improbable Thing.

If there are moments in your manuscript that you’re really struggling to sell, if you think they’re too far out there to make sense with plot or character, but you like or need them, think about context. By changing the wrapper, you can still give the reader the present, it will just be surrounded by a different situation or motivation or expectation. It’s up to you to create that experience and make it believable.

Of course, some things are just not going to be a good fit, no matter how hard you try. But others might just be, well, crazy enough to work, as long as you frame them right.

Add a CommentBlog: Pub(lishing) Crawl (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Giveaways, Guest Post, Industry Life, Julie Czerneda, Interviews, Reading, Writing Life, Plot, Science-Fiction, Critique Partners, Add a tag

So without further ado, welcome Julie!

Science fiction folks know. What they like and don’t like. Most particularly, they know what they love. All about what they love. I’ve been to conventions. Trust me. You can count me among them for I’m just as cautious about a “new” take on a beloved film or tv series. Hopeful, yes, because I want more. But cautious.

Because, seriously. What if They mess it up?

There’s no mysterious and plural They involved in my books. There’s just me. My publisher, quite rightly, expects me to know what I’m doing. My readers do too. So when I returned to write more about Morgan and Sira, I understood the stakes. I had to get it right. Me. All by myself.

Unless…I had help. What if I could find another set of expert eyeballs? Someone who’d recently reread the first six books of the series. Someone who cared about details. Someone who loved the story enough to tell me if I messed up their hopes for it.

Impossible, I thought, but nothing ventured, nothing gained. Having received permission from my publisher to grant access to the unpublished manuscript, I set up a webpage with quiz questions drawn from the series, and launched a Betareader Competition. (You can try it yourself, with answers!)

EGAD! People leapt to participate. It was amazing. I took the top ten respondents and grilled them with a second, tougher quiz. At the end, I’d found my readers. I’m delighted to introduce Carla Mamone and Lyndsay Stuart, winners of a tough job and official betareaders of the first draft of This Gulf of Time and Stars.

Julie: Ladies, whatever made you do all this?

Carla: When I heard about the betareader competition, I thought it sounded really fun and interesting. I’m a very meticulous person, so I knew I could (hopefully) do a good job. Plus, I couldn’t pass up an opportunity to work with one of my favourite authors.

Lyndsay: I was spending a lot of time stuck in a chair with a new baby and needed to set my mind to some work or go crazy. It was a chance to use my powers for good. Besides, how could I live with myself if I let the chance go by without even testing myself on the quiz?

Who am I kidding? While all that is true, the draw was the chance to read the book early! I’m terribly impatient and all the work was worth it!

Julie: I have to admit, it was wonderful knowing you were both so excited to do this. But it was work. What did you find the hardest part?

Carla: Not being able to tell anyone about the story. I love talking about the books that I am reading, so it was really hard not to talk about such an exciting story. My husband would ask me what was so funny or why I was crying and I couldn’t tell him about any of it. That was definitely the hardest part.

Lyndsay: The characters and the story aren’t mine so who am I to say when they aren’t right?! It was a bit tough to look at things a little more critically than usual – especially when the story was so interesting & exciting that the last thing I wanted to do was flip back and double check things! In a few places I had to highlight the text and admit that I didn’t understand the reasons underlying particular tensions or a character’s reaction to ::cough, cough:: circumstances.

Julie: Carla, you went above and beyond. I do believe I would have trusted your husband. But thank you for being so good about the non-disclosure thing. (Sorry about the tears, but it did help to know where the story had impact.) Lyndsay, when you showed me what you didn’t get, that was great. Very often I’d been obtuse, or found a different way to tweak. Now, I’ll feel less guilt once you’ve told us what was the most fun.

Carla: Not having to wait until November to see what happens next to Sira and Morgan. I also really enjoyed working with you and Lyn. You’re both so kind, I couldn’t ask for better people to work with.

Lyndsay: I bounce-floated around the house for a month, the surprises in the story are so good! Julie doesn’t just dish out surprises, she’s given us clues about the next book too! I have my guesses and can’t wait until you guys read the book. There is much to discuss.

Julie: Back at you, Carla. And the wait’s over now! One thing I’d asked, and you provided, were any bits you especially enjoyed. Thank you both for those.

The crucial factor, for me, in choosing a betareader wasn’t only expertise, for many people had that, but how well—and quickly–you could communicate my mistakes to me. Time was of the essence, as I had only the gap between my submitting first draft and the final galleys in which to make corrections. You were both amazing, but be honest, how hard was it to squeeze this into your lives?

Carla: The timing actually worked out perfectly. I was in the middle of planning my wedding and was getting pretty stressed and overwhelmed. Betareading gave me an excuse to take a break from wedding planning for a few weeks. So, after I was finished, I was excited to get back to planning and didn’t feel as overwhelmed.

Lyndsay: When this competition began I had a 2 month old baby and a 2 year old toddler, all my reading, studying and annotation couldn’t happen until nap time and I knew Julie was depending on me. Eek! I learned that diapers and reading tablets do not mix with pleasing results.

Thankfully it seems that my real world job experience reviewing written material paid off and for once I got to offer helpful suggestions on something I love. Is this what we call a Unicorn? It’s at least Cinderella getting to go to the ball.

Julie: Congratulations again, Carla! And how lovely being a reader was something good at the time. Whew! Lyndsay, as a person who started full time writing with a 6 month old and a 2 and a bit, I tip my hat. It’s hard enough to get to the bathroom, let alone think. Bravo, both.

Both, you see, because I decided to have two betareaders. (As well as a trusty standby third in case.) Why? Firstly, so you could, if you wanted, talk about me behind my back. The main reason, however, was because I saw from your quiz answers regarding the sample scene that you each identified different problems to bring to my attention. I’m not sure you knew that, but I knew I should have you both. How did you choose what to point out to me?

Carla: I tried to find anything that didn’t match the characters’ personalities or descriptions from the previous novels. I didn’t include anything that was specific only to Gulf, unless I felt that it was necessary.

Lyndsay: Hmm, how to answer without spoilers? For example, there was a section where the timeline had a tiny hiccup. A discrepancy of +/- a few hours doesn’t usually jog a reader out of the story, but in this book I had to point it out. It mattered because the characters can’t go out in the dark so the timing issue created an impossible situation.

Julie: Humbled, I was. Grateful, most of all. Thank you, Carla and Lyndsay, from the bottom of my heart. Gulf wouldn’t be the book it is without you, and you gave me the confidence to send it forth knowing those who’ve loved the series will continue to do so. It’s only fair to let you two have the last word!

Carla: I just want to thank you, Julie, for your wonderful books and for letting me be a part of this one. I had a great time!

Lyndsay: To Julie & DAW, I’m very glad to have gotten this opportunity and thankful to all who helped make it happen.

To you, Readers, I must say that at the end of Rift in the Sky Julie promised all of us we “ain’t seen nothing yet.” Julie knows exactly who and what we love and she’s filled this book up with all of it. Wondering what’s next to come is killing me! Until then it’ll be a big treat to read the final, polished version of This Gulf of Time and Stars.

Julie: Thanks again! A last, last word. (I get to do that.) Invaluable as my betareaders’ expert eyes proved–followed by those of my alert editor, copyeditor, and proof readers–please remember the responsibility for consistency and continuity in the Clan Chronicles is mine alone.

As it should be. Enjoy this new installment!

And now, the giveaway! Enter to win a free copy of This Gulf of Time and Stars, open to participants in the US and Canada. If audio books are more your thing, we’re giving away one of those, too! Listen now to a sample from the audiobook of This Gulf of Time and Stars narrated by Allyson Johnson, courtesy of audible.com

Cover Credit: Matt Stawicki

The Clan Chronicles is set in a far future with interstellar travel where the Trade Pact encourages peaceful commerce among a multitude of alien and Human worlds. The alien Clan, humanoid in appearance, have been living in secrecy and wealth on Human worlds, relying on their innate ability to move through the M’hir and bypass normal space. The Clan bred to increase that power, only to learn its terrible price: females who can’t help but kill prospective mates. Sira di Sarc is the first female of her kind facing that reality. With the help of a Human starship captain, Jason Morgan, Sira must find a morally acceptable solution before it’s too late. But with the Clan exposed, her time is running out. The Stratification trilogy follows Sira’s ancestor, Aryl Sarc, and shows how their power first came to be as well as how the Clan came to live in the Trade Pact. The Trade Pact trilogy is the story of Sira and Morgan, and the trouble facing the Clan. Reunification will conclude the series and answer, at last, #whoaretheclan.

Since 1997, Canadian author/editor Julie E. Czerneda has shared her love and curiosity about living things through her science fiction, writing about shapechanging semi-immortals, terraformed worlds, salmon researchers, and the perils of power. Her fourteenth novel from DAW Books was her debut fantasy, A Turn of Light, winner of the 2014 Aurora Award for Best English Novel, and now Book One of her Night`s Edge series. Her most recent publications: a special omnibus edition of her acclaimed near-future SF Species Imperative, as well as Book Two of Night`s Edge, A Play of Shadow, a finalist for this year’s Aurora. Julie’s presently back in science fiction, writing the finale to her Clan Chronicles series. Book #1 of Reunification, This Gulf of Time and Stars, will be released by DAW November 2015. For more about her work, visit www.czerneda.com or visit her on Facebook, Twitter, or Goodreads.

Since 1997, Canadian author/editor Julie E. Czerneda has shared her love and curiosity about living things through her science fiction, writing about shapechanging semi-immortals, terraformed worlds, salmon researchers, and the perils of power. Her fourteenth novel from DAW Books was her debut fantasy, A Turn of Light, winner of the 2014 Aurora Award for Best English Novel, and now Book One of her Night`s Edge series. Her most recent publications: a special omnibus edition of her acclaimed near-future SF Species Imperative, as well as Book Two of Night`s Edge, A Play of Shadow, a finalist for this year’s Aurora. Julie’s presently back in science fiction, writing the finale to her Clan Chronicles series. Book #1 of Reunification, This Gulf of Time and Stars, will be released by DAW November 2015. For more about her work, visit www.czerneda.com or visit her on Facebook, Twitter, or Goodreads.Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, Add a tag

These four steps can help you turn your plot ideas into a plot.

http://jodyhedlund.blogspot.co.uk/2015/08/4-steps-for-organizing-plot-ideas-into.html

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: scene, revise, turning point, pivot point, Plot, Add a tag

I’m revising my WIP novel one scene at a time and finding places where I need to do lots of work. Specifically, I want scenes that pivot.

A scene is self-contained section of the story. Characters come into a scene with a goal and they either reach their goal or not. The scene should have a beginning, middle and end. And, according to THE SCENE BOOK by Sandra Scofield, your scene also needs a pivot point.

Scofield says that characters go into a scene with a goal, with something they are fighting for. But at some point the story twists, deepens, or changes in a fundamental way.

If you don’t have one, the scene is boring. Think about where the scene’s essence lies: the point at which everything changes. There if Before X and After X. X is the focal point. – Sandra Scofield, p. 54, The Scene Book

It’s a hard concept in some ways to talk about, but you know it when you see it. In this short scene from the movie,”Good Will Hunting,” the focal point, pivot point, hot spot, turning point, or apex is when Will steps in to help his friend. This is a great example because it shows the character in action, doing something that matters.

If you can’t see this video, click here.

By contrast, some scenes in my WIP just sit on the page. For example, I have one scene where the main character meets the romantic interest character. There’s a lot of characterization going on; they are at a coffee shop where she’s a barista and he’s ordering a special coffee drink; there’s some humor. But the scene still felt flat. Until I realized that there’s no real pivot point, no fulcrum for the scene. To change it, he asks a simple question, “Who are you?” That launches her into a humorous, but character-revealing pseudo-tirade, which results in him really paying attention to her and finding that he’s VERY attracted. Before the tirade, he’s not interested; after the tirade; he’s hooked.

To revise your scenes, fill in the blanks:

Before _____________(Pivot Point), my character _______________; AFTER _______________(Pivot Point), my character ____________________.

Find a way to pivot somewhere in each scene–and you’ll hook me as a reader!

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, Add a tag

Having a detailed chart of your scenes makes it much easier to understand your plot.

http://nerdychickswrite.com/2015/07/29/yvonne-ventresca-plot-revision-table-and-giveaway/

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, Add a tag

Find out how to use spidergrams in plotting your book.

http://nerdychickswrite.com/2015/07/28/leeza-hernandez-plotting-with-spidergrams-and-giveaway/

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, Add a tag

Find out how to use spidergrams in plotting your book.

http://nerdychickswrite.com/2015/07/28/leeza-hernandez-plotting-with-spidergrams-and-giveaway/

Blog: Ken Baker: Children's Author (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: characters, plot, writing class, writing tips, relationships, Add a tag

Tonight in the night class I teach at a local university on writing children's books, we'll be talking about how the relationships your characters have can deepen your story's plot, enhance the connection between your characters and readers, raise tension, complicate conflicts, and much more.

The following are 8 ways you can use relationships between your characters to enhance the stories you write:

- Create resonance with your audience by putting your characters in relationships that matter most to and intrigue your readers

- Use your character relationships to better reveal your characters’ personality and inner conflicts

- Use character relationships to pull your readers deeper into the story and your characters’ lives

- Use your character interactions to give your characters more profound opportunities to experience growth or change

- Deepen your plot with character relationships that increase the conflict, tension and emotional/physical stakes of the story

- Deepen your plot with character relationships that impede, thwart or help the protagonists’ success, or distract the protagonist from the end goal

- Raise the emotional tension of your stories by creating relationship events or taking character relationships in a direction that terrify your readers

- Increase the emotional connection between your readers and characters by creating relationship events or taking character relationships in a direction that makes readers worry, sad and/or happy

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, Add a tag

When something happens in a scene (stimulus), your characters need to have a reaction (response).

http://www.adventuresinyapublishing.com/2015/06/stimulus-and-response-finding-your-way.html

Blog: The Open Book (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plotlines, New Voices Award, Writer Resources, As Fast As Words Could Fly, Pamela Tuck, Lee & Low Likes, New Voices/New Visions Award, jennifer torres, Interviews with Authors and Illustrators, finding the music, plotting a story, Awards, plot, plotting, Add a tag

This year marks our sixteenth annual New Voices Award, Lee & Low’s writing contest for unpublished writers of color.

This year marks our sixteenth annual New Voices Award, Lee & Low’s writing contest for unpublished writers of color.

In this blog series, past New Voices winners gather to give advice for new writers. This month, we’re talking about tools authors use to plot their stories.

Pamela Tuck, author of As Fast As Words Could Fly, New Voices Winner 2007

One tip I learned from a fellow author was that a good story comes “full circle”. Your beginning should give a hint to the ending, your middle should contain page-turning connecting pieces, and your ending should point you back to the beginning.

The advantage I had in writing As Fast As Words Could Fly, is that it was from my dad’s life experiences, and the events were already there. One tool that helped me with the plot was LISTENING to the emotions as my dad retold his story. I listened to his fears, his sadness, his excitement, and his determination. By doing this, I was able to “hear” the conflict, the climax, and the resolution.

One major emotion that resonates from my main character, Mason, is confidence. I drew this emotion from a statement my dad made: “I kept telling myself, I can do this.” The challenging part was trying to choose which event to develop into a plot. My grandfather was a Civil Rights activist, so I knew my dad wrote letters for my grandfather, participated in a few sit-ins, desegregated the formerly all-white high school, learned to type, and entered the county typing tournament. Once I decided to use his typing as my focal point, the next step was to create a beginning that would lead up to his typing. This is when I decided to open the story with the idea of my dad composing hand-written letters for his father’s Civil Rights group. I threw in a little creative dialogue to explain the need for a sit-in, and then I decided to introduce the focal point of typing by having the group give him a typewriter to make the letter writing a little easier. To build my character’s determination about learning to type, I used a somewhat irrelevant event my dad shared: priming tobacco during the summer. However, I used this event to support my plot with the statement: “Although he was weary from his day’s work, he didn’t let that stop him from practicing his typing.” His summer of priming tobacco also gave me an opportunity to introduce two minor characters who would later add to the tension he faced when integrating the formerly all-white school.

The second step was to concentrate on a middle that would show some conflict with typing. This is when I used my dad’s experiences of being ignored by the typing teacher, landing a typing job in the school’s library and later being fired without warning, and reluctantly being selected to represent his school in the typing tournament.

Lastly, I created an ending to show the results of all the hard work he had dedicated to his typing, which includes a statement that points back to the beginning (full circle).

Although the majority of the events in As Fast As Words Could Fly are true, I had to carefully select and tweak various events to work well in each section, making sure that each event supported my plot.

Jennifer Torres, author of Finding the Music, New Voices Winner 2011

I’m a huge fan of outlines and have a hard time starting even seemingly simple stories without one. An outline gives me and my characters a nice road map, but that’s not always enough. Once I had an outline for Finding the Music, it was really helpful to visualize the plot in terms of successive scenes rather than bullet points. I even sketched out an actual map to help me think about my main character Reyna’s decisions, development and movement in space and time.

Still, early drafts of the story meandered. There were too many characters and details that didn’t move the plot forward. When stories begin to drift like that, I go back to my journalism experience: Finding the Music needed a nut graph, a newspaper term for a paragraph that explains “in a nutshell” what the story is really about, why it matters. Finding the Music is about a lot of things, but for me, what it’s *really* about is community—the community Reyna’s abuelo helped build through this music and the community Reyna is part of (even though it’s sometimes noisier than she’d like). I think Reyna’s mamá captures that idea of community when she says, “These are the sounds of happy lives. The voices of our neighbors are like music.”

Once I found the heart of the story, it was a lot easier to sharpen up scenes and pull the plot back into focus.

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, flashback, Add a tag

You can play around with time in your story, but be careful not to confuse your reader.

https://warriorwriters.wordpress.com/2015/06/15/understanding-the-flashback-bending-time-as-a-literary-device/

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, Plot, surprise, emotion, Novel Revision, write a novel, revise a novel, enrich, Add a tag

Abayomi Launches in Brazil

Click cover to see the photo gallery.

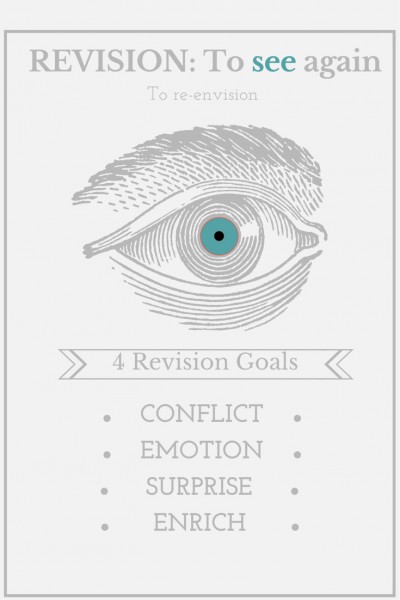

For the next month, my writing goals for my work-in-progress novel trilogy are clear: conflict, emotion, surprise, enrich.

The trilogy is tentatively called, The Blue Planets, and is an early-teen or YA science fiction. Book 1, The Blue Marble, has a complete draft; for Books 2 and 3, I have complete outlines. I’m happy with all of it, but I know it needs to go much farther before anyone sees it. For the next month, I’ll work simultaneously on revising Book 1 and the outlines, trying to weave them into a more coherent whole.

4 Revision Goals

Conflict. The first goal in revising The Blue Planets is to up the conflict.

No conflict = no story, no readers.

Small conflict = small readership.

Big conflict = bigger readership.

Huge, gut-wrenching, moral-decison-making conflict = huge, engaged readership.

I’ll be looking at conflict globally and in each scene. Man v. nature is built into the story in powerful ways already. But I need to look at man v. man, both overall and in each scene. How can I put people at odds in more ways and in more interesting ways?

Emotion. Always my weakest point, I’ll go scene by scene and ask questions:

What emotional things happened just before this scene? What’s the attitude of each character coming in?

What is the worst thing–emotionally–that could happen to the main character? That’s what I must confront him with.

What is the emotional arc of the scene?

What else can I do to deepen the emotional impact?

Surprise. Readers read for entertainment. If they can predict exactly what happens in a story, they’re bored. I’ll go through–especially the outlines–and ask, “What does the reader expect here?” I’ll look for ways to twist that expectation to fulfill it, but with a twist.

Enrich. I’m excited about enriching the stories, because this part gets past the basic plotting and into fun stuff. Where can I add humor? Here are previous posts on 3 humor techniques and then 5 more. I’m hoping for a running gag, at least. I’ll be working to tie the three books together through scene, character, bits of dialogue, running gags, perhaps a bit of clothing, or a mug of triple-shot venti mocha–something. Enrichment might be adding bits of scientific information artfully, without doing an information dump. Making the characters quirkier and more fun to be around. Loosening up on dialogue.

By the middle to end of July, I expect the BLUES to be in shape to send out. I’m excited.

What are your goals for summer writing?

View Next 25 Posts