new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Garden Painter Art, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 167

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Garden Painter Art in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

I’m revising my WIP novel one scene at a time and finding places where I need to do lots of work. Specifically, I want scenes that pivot.

A scene is self-contained section of the story. Characters come into a scene with a goal and they either reach their goal or not. The scene should have a beginning, middle and end. And, according to THE SCENE BOOK by Sandra Scofield, your scene also needs a pivot point.

Scofield says that characters go into a scene with a goal, with something they are fighting for. But at some point the story twists, deepens, or changes in a fundamental way.

If you don’t have one, the scene is boring. Think about where the scene’s essence lies: the point at which everything changes. There if Before X and After X. X is the focal point. – Sandra Scofield, p. 54, The Scene Book

It’s a hard concept in some ways to talk about, but you know it when you see it. In this short scene from the movie,”Good Will Hunting,” the focal point, pivot point, hot spot, turning point, or apex is when Will steps in to help his friend. This is a great example because it shows the character in action, doing something that matters.

If you can’t see this video, click here.

By contrast, some scenes in my WIP just sit on the page. For example, I have one scene where the main character meets the romantic interest character. There’s a lot of characterization going on; they are at a coffee shop where she’s a barista and he’s ordering a special coffee drink; there’s some humor. But the scene still felt flat. Until I realized that there’s no real pivot point, no fulcrum for the scene. To change it, he asks a simple question, “Who are you?” That launches her into a humorous, but character-revealing pseudo-tirade, which results in him really paying attention to her and finding that he’s VERY attracted. Before the tirade, he’s not interested; after the tirade; he’s hooked.

To revise your scenes, fill in the blanks:

Before _____________(Pivot Point), my character _______________; AFTER _______________(Pivot Point), my character ____________________.

Find a way to pivot somewhere in each scene–and you’ll hook me as a reader!

By: Metin Seven,

on 4/7/2015

Blog:

Sugar Frosted Goodness

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

illustration,

art,

classic,

metin seven,

landscape,

retro,

scene,

Artwork,

desert,

pixel art,

minimalism,

vulture,

minimalistic,

Add a tag

Desert scene in a minimalistic pixel art style, for a Talk Retro site redesign.

Available as a high quality art print.

More images: MetinSeven.com.

By: Metin Seven,

on 3/31/2015

Blog:

Sugar Frosted Goodness

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

character,

animation,

metin seven,

scene,

3d,

amigurumi,

texture,

crochet,

figure,

crocheting,

crocheted,

Add a tag

3D version and animation scene mockup of a crocheted Dendennis amigurumi figure.

More: MetinSeven.com.

Join Leslie Helakoski and Darcy Pattison in Honesdale PA for a spring workshop, April 23-26, 2015. Full info

here.

COMMENTS FROM THE 2014 WORKSHOP:

- "This conference was great! A perfect mix of learning and practicing our craft."�Peggy Campbell-Rush, 2014 attendee, Washington, NJ

- "Darcy and Leslie were extremely accessible for advice, critique and casual conversation."�Perri Hogan, 2014 attendee, Syracuse,NY

Today, I worked on a difficult scene. It wasn’t a big action-packed scene; those are easy. Instead, it was a transition scene that moved the story along a week and had the potential to lose the reader with it’s lack of tension.

Donald Maass, in his Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook, repeats this signature mantra, “Tension on every page.”

He points out three types of scenes that can be a trap for the lazy writer: Tea time or any time people eat together; transporting characters from one spot to another; and dialogue. Maass recommends that you cut these scenes:

The most controversial part of my Writing the Blockbuster Novel workshop pis this exercise, in which I direct authors to cut scenes set in kitchens or living rooms or cars driving from one place to another, or that involve drinking tea or coffee or taking showers or baths, particularly in a novel’s first fifty pages. Participants look dismayed when they hear this directive, and in writer’s chat rooms on the Web it is debated in tones of alarm. No one wants to cut such material.

Unless you give these scenes careful attention, they can wind up as BORING!

Strategies for Dealing with Low Tension Scenes

In working through my scene, I focused on a couple strategies for approaching such Bore-Traps.

The moment before. What happened right before this scene? Characters don’t go into a scene neutral. Sometimes, just thinking about the moment before will help you get a handle on what tensions or conflicts could be built into the scene. For example, if Jillian and Dad step out of the car at a used-car dealership and talk to a salesman about the 2012 Toyota Camry, it could be boring: How much is it? Do you finance? Want to take a test drive?

If, however, you take a moment to explore the moment before, you might find some interesting points of tension:

Our salesman, William, has just learned that his brother was in a motorcycle wreck and while he lived, William is now obsessing about car safety. Jillian has been trying to convince her Dad to get her a new car and is angry that he’s stopping at the used car shop, while Dad is worried because Mom just told him she’s filing for divorce and Dad doesn’t know how he can afford to buy Jillian any kind of car, what with the upcoming lawyer bills. Try writing that scene again, after all of THAT!

Character’s attitudes going into a scene. Similar, but slightly different is an emphasis on character attitudes going into a discussion. For William, we could choose from several attitudes: obsessing over safety, anxious to get done and get to the hospital so he speeds through everything, angry with brother because William just convince his wife to get a motorcycle and his blockhead brother just messed up that deal. Jillian could be pleading, sarcastic, grateful, or even indifferent. Dad could be generous, angry, stingy, resentful and more. Decide on the character’s attitudes, making sure that they are coming into the discussion at tangents.

Small moments of tension. This may seem obvious, but what I mean by this is to look for things or situations within the scene that could go wrong. For example, in my current story, the kids are in a cafeteria, and when the boy opens his coke, the carbonation explodes all over. It’s a small thing, a common thing. But it’s conflict. What is present in your situation/scene that could spill over with some small conflict?

Foreshadow something that is coming – look forward. Another reason the coke explosion worked for me is that the story involves volcanoes! It’s a minor foreshadowing of what’s coming. Look ahead in your story to see if you can provide even a minor foreshadowing.

Refer back to something – look backward. Don’t just look forward. Also look back to previous chapters and try to echo something. Can you echo it with some kind of progression? Make it faster, higher, bigger, etc? And plan another time to use that element and make it the fastest, biggest, highest, etc.?

My scene, which started as a bore, is much tighter and has more tension. It’s a collection of small moments of tension that adds up to an important transition scene that keeps the reader turning the pages.

Join Leslie Helakoski and Darcy Pattison in Honesdale PA for a spring workshop, April 23-26, 2015. Full info

here.

COMMENTS FROM THE 2014 WORKSHOP:

- "This conference was great! A perfect mix of learning and practicing our craft."�Peggy Campbell-Rush, 2014 attendee, Washington, NJ

- "Darcy and Leslie were extremely accessible for advice, critique and casual conversation."�Perri Hogan, 2014 attendee, Syracuse,NY

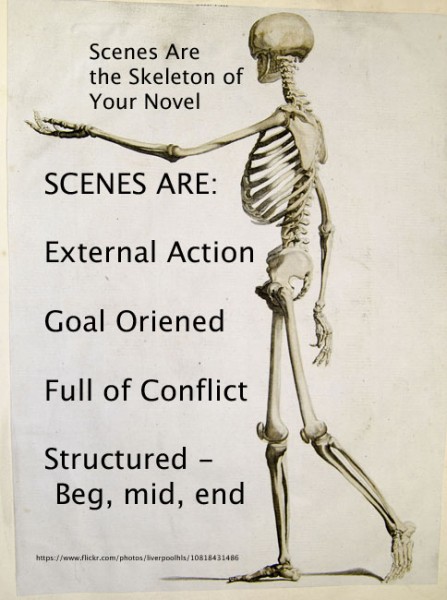

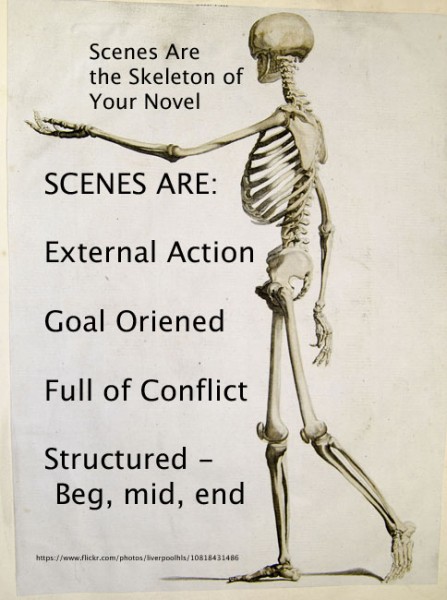

You’re a human being: you can stand up, sit down, or do a somersault. That’s because you have a skeleton that gives your soft tissue a structure.

Likewise, it’s important to give your novel a structure that will hold all the soft murmurings about characters, places and events. It begins with understanding the structure of a scene. First, let’s answer the question: do you have to write in scenes? No. There’s a continuum from those who write strictly in scenes to those who don’t. However, for beginning to intermediate writers, you’ll see more improvement in your writing if you move closer to the strictly writing in scenes end of that continuum. Early in a career, writers need discipline to add structure that may come more easily with experience.

External Action. A scene is a unit or section of a story that hangs together because of the action or event. Scenes are not internal, but external. Something must physically happen.

Something Changes. Something important must happen in a scene; after the scene is over, the situation must be different for the character’s lives. The definition of “important” and “different,” of course, will change with the genre, but still, we recognize that something important has created a difference.

Goal Oriented. The strongest scenes begin with a character wanting something and encountering difficulties in achieving his/her goal. The goal can change or develop over the course of a story, but it must be there.

Conflict. If your character wants something (Goal), and they have instant gratification (Result), that’s not a scene. Every Goal must meet with obstacles that prevent the character from achieving the goal. This is the basic promise of all fiction, that life will encounter problems that won’t be solved till the last page.

Beyond these requirement, strong scenes add a deeper structure. It’s not required, for those who only write loosely in scenes, but it helps.

Scenes can be divided into three or four sections: beginning, middle, turning point or pivot, ending.

Beginning: This sets up the situation, setting, characters and the goal.

Middle: Conflict piles on conflict as the goal gets farther and farther away.

Turning point/Pivot: Something happens to spin the story in a different direction. Scenes without a pivot are possible, but scenes WITH a pivot are more interesting.

Ending: What has changed?

Good Will Hunting: Bar Scene Analyzed

A good way to see the structure of a scene is to watch the “Bar Scene” from the movie, Good Will Hunting. If you can’t see this video, click here.

Beginning: Will and his friends enter the bar, choose a table, order a beer.

Goal: These “Southies” want to experience a Harvard Bar and maybe pick up a girl.

Middle: Chuckie goes over to check out a girl. But a Harvard man steps in to put him down.

Pivot point: Will takes over the conversation with his superior intellect.

Ending: Will meets the love interest. The conversation with the Harvard man is a win/lose: Will wins because he manages to make his point that a college education isn’t everything; however, listen carefully to the deeper conversation about class distinctions and you’ll see that Will still faces challenges.

For more on scenes, I always recommend Sandra Scofield’s excellent book, The Scene Primer. Or see my series, 30 Days to a Stronger Series.

Last week, we looked at different options for scene and overall story goals. This week, we'll look at examples that illustrate the theory. Scenes are stonger if the characters involved have opposing goals that create tension. Conflict does not have to be a knock-down, drag-out fight scene.

1. At the overall story level, if Dick wants to marry Jane, the antagonistic forces try to keep them apart. Each scene involves a combination of characters fighting to make it happen or keep it from happening. Friends and foes may have their own goals that help or hinder their relationship. Sally is in love with Dick, so she does everything she can to capture his attention, until she feels forced to kidnap him.

2. Ted might decide that Jane isn’t really good for Dick. He can interfere by relating harmful gossip about Jane or by inserting himself into Dick and Jane’s date at scene level. He can try to make it look like Jane cheated on Dick.

3. Sally might want to own Spot because Spot is a perfect example of his breed and is worth gazillions in breeding fees. Sally might kidnap Spot or try to fool Dick by switching Spot with a dog that looks similar. Sally will either succeed or fail. Every time the antagonist fails in her goal, she is forced to come up with new tactics.

4. Dick might fight to keep a law because it is beneficial to him. Dick and Jane will fiercely debate their sides of the thematic argument with each other and with their friends and foes. They will gain support and lose support. At the climax of the conflict, the law will either be upheld or overturned.

5. Sally may not want Jane to leave the company because doing so would make it a lonelier place to work. Sally will take steps to convince Jane to stay. The steps can be comic, touching or obsessively creepy. Sally will either succeed or fail. Jane will leave, stay, or escape death by a hair’s breadth.

6. Jane believes in fairies. Everyone at school thinks she is crazy. She will attempt to prove her belief is valid. Her evidence will be convincing, or not. The more unsubstantiated the proof she offers, the crazier she appears. She may find allies in students who want to believe or who had unusual encounters themselves. The school authorities and other students will do everything they can to make her look insane. If the fairy queen is killing people, Jane might be blamed for the deaths. It will be even more important for her to prove she is innocent and the reader will be rooting for her to succeed. In the final climactic moment, the fairy queen appears and vaporizes half the school. They believe Jane, but it’s too late for most of them. She succeeds but others pay for their disbelief.

7. At the scene level, if Jane wants the corner office, Dick will refuse to give it up. Jane might appeal to their boss, stating she has the greater talent. She might undermine Dick's current project to make him look bad. If that doesn't work, she may try to bribe Dick. If that doesn’t work, she can threaten to kill him if he doesn't step down.

8. Sally is confronted with a situation that she can either allow or avert. Sally knows someone plans to embarrass Dick at a party. If she likes Dick, she will warn him or do something to change the situation so Dick isn’t embarrassed. If she hates Dick, she will sit back and enjoy the spectacle. If the reader likes Dick, they will feel bad. If they hate Dick, they will enjoy it with her.

9. Jane may need to tell Dick something important about Sally. Sally overhears Jane’s opening conversational salvo, “Dick, do you remember last week when you thought your office door had been locked, but you found it open?” Sally realizes Jane is about to tell Dick she saw Sally leaving Dick’s office. As Jane attempts to deliver the information, Sally distracts Dick so that he can’t listen. She might talk over Jane. She might try to steer Dick away from Jane. She may employ a full-frontal verbal assault that forces Jane to defend herself instead of delivering the important information to Dick. Jane can successfully dodge Sally’s attempts and succeed, or she will leave the field and attempt to tell Dick another day. If she fails, the scene goal isn’t satisfied and Jane will have to make another attempt to achieve it. A further complication has been created and Sally will have to find a way to silence Jane. Sally may bribe or threaten her in a subsequent scene.

10. Dick may believe that Sally is lying about where she went the night before. Dick needs reassurance. His mental security center is under attack. He will ask probing questions. If Sally is telling the truth, she will answer him calmly, but with a touch of irritation because she hates having her integrity questioned. If she is lying, she will have to invent the story on the fly. The more specific the questions, the more awkward and convoluted her answers will become. Sally will either storm off or turn the tables and accuse Dick of everything from leaving the toilet seat up to being the lone gunman who shot JFK. Dick will either back down or give her an ultimatum, “Tell me the truth or we’re done.” Dick will either succeed at his scene goal or fail. The reader will be rooting for Dick to hear the truth if they dislike Sally. They will be rooting for him to be wrong if they like Sally.

Coming up with scenes that keep the reader engaged is easy once you start thinking of them in this way. There are many subtle ways to build conflict and tension with opposing goals.

Coming up with a scene or story goal sounds momentous and difficult.

It isn’t.

Your character doesn’t need to have a million dollar sales goal or desire to scale Mount Everest.

Writers pick goals for their characters instinctively, if not consciously. When you sit down to write a scene, your characters do and say things. What they do and say should have purpose. Their actions and words should move the story forward or cause complications or reversals.

Every story should have a central conflict at the heart of it that is easily summarized in a one-sentence logline.

A strong scene has a central conflict too. That doesn't mean only one thing happens in a scene or that only one character has a goal in each scene. It means the point of view character for each scene has a reason for being there and that he is earning his page time.

Think of a story or scene goal as having a subject, object, verb, and outcome.

The subject is the point of view character.

The verb is the motion toward or away from the object.- Obtain or get rid of it.

- Hold onto or release it.

- Reach or escape it

- Hide or reveal it.

- Change or keep from changing it.

- Tell or not tell it.

- Evade or capture it.

- Avert or allow it.

- Define or obscure it.

- Prove or disprove it.

- Evaluate or decide it.

The object is the target or focus of the words and actions.- Person

- Place

- Thing

- Information

- Situation

- Physical Task

- Mental Task

- Need

- Want

- Emotion

- Belief

- Prejudice

For every struggle there is an outcome.- The character can succeed in his goal and feel good about it or bad about it.

- The character can achieve his goal only to find out it was the wrong goal.

- The character can achieve his goal and find they have created a bigger problem.

- The character can fail and feel good about it or bad about it.

- The character can fail and realize he was after the wrong goal, so his failure was really a success.

The goal of the antagonist, or antagonistic forces, is to keep the protagonist from obtaining the object and make the verb challenging.

Friends and foes provide stumbling blocks and step ladders to keep the character moving toward and away from the object and make the verb more difficult or easier.

Providing stiff opposition and high stakes equals high tension.

Movement toward and away from the scene and story goals creates satisfying S-curves readers enjoy cruising, or racing, through to reach the story’s end. It adds the requisite tension to keep the reader turning pages.

If you can complete one sentence for your entire story, you have a solid logline.

Character (subject) wants to (verb) the (object) and (outcome).

If you can complete one sentence for every chapter, you have a solid synopsis.

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 7/22/2014

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

novel,

scene,

plotting,

write,

revise,

action,

Novel Revision,

plot points,

off-stage,

Add a tag

The ALIENS have landed!

"amusing. . .engaging, accessible," says Publisher's Weekly

|

|

|

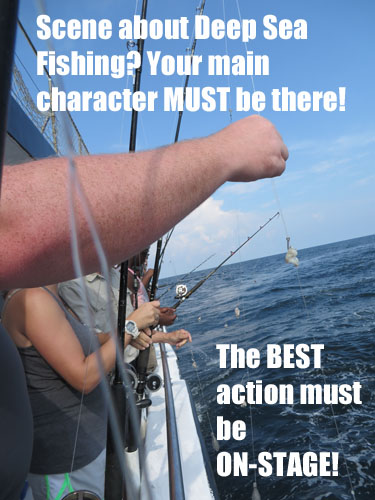

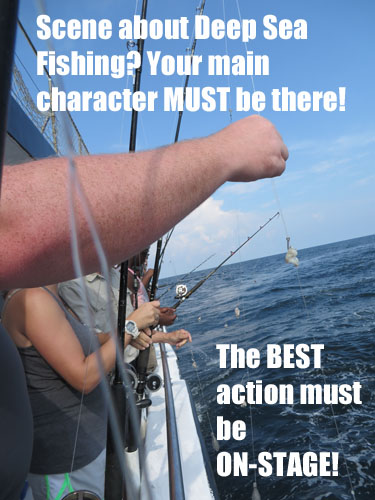

Here’s a common problem that I see in first drafts: the main action has happened off-stage.

Think about Scarlett O’Hara and the other southern women sitting at home waiting; in an attempt to avenge his wife, Frank and the Ku Klux Klan raid the shanty town whereupon Frank is shot dead. But the raid takes place off-stage.

Or, think about times when a weaker character stays home, while the adventurous character is off doing something. Sports stories are hard when the POV character is watching the on-field action.

This can be a real trap for children’s novels if an older sibling or parent is doing something fun/exciting/scary/etc off stage.

Another challenging situation is when a bully is planning something and the POV victim is just trying to avoid that.

Or, maybe you’ve planned a great scene, and the main character is present, but you don’t write that scene. Instead, what you write is something like this: “The next morning, Elise lay in bed and went over the previous night in her head.”

No. That doesn’t work!

Does this always need to be changed? No. But it’s a major problem and challenge as you revise. Here are some tips.

Recognize the problem. As you write the first draft and revise it, you should be evaluating the scenes. Ask: Who hurts the most in this scene. It should almost always be the main character. If it’s someone else, why isn’t THAT character the hero/ine of the story?

Put the POV Character in the action. When you find a scene where the main action is off-stage, look for ways to rethink the plot and scenes and put the main character in the thick of the action. It’s why Captain Kirk leaves the Enterprise and goes down to the planet over and over and over. Really? No Captain would be allowed to jeopardize his life that much and give over the control of the ship to a junior officer. It’s unrealistic–but great storytelling.

Make the story about how the off-stage action affects the POV character. In Gone with the Wind, Frank and the other men go off to avenge Scarlett’s honor, but the POV stays firmly with Scarlett. It’s about her growing realization of what the men have gone off to do, the opinion of the other women, and eventually the women’s reactions when the men come back. This is a risky way to write a scene, because the real stuff happens off stage; but it can work if you keep the focus right.

Write the scene. If your character is just thinking about what happened last night, it’s a simple fix. Write the @#$@#$@# scene! Sometime this happens when the author is afraid of the emotions in a powerful scene; the author avoids writing that scene and tries to jump forward in time. It never works. You must write the scene that you fear. you must write the exciting scene because your reader demands it; that is the exact reason why they come to your story. Don’t cheat them out of the emotionally experience.

.png.jpg?picon=4257)

By: Diana Hurwitz,

on 9/6/2013

Blog:

Game On! Creating Character Conflict

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

craft,

maps,

scene,

description,

setting,

howto,

tours,

location,

pictures.,

fiction,

writing,

Add a tag

Just as a film director scouts locations for his film, you can scout locations for your book. Whether you are an organic, planner, or hybrid writer, your scenes will be set somewhere.

When you are planning or writing your novel, it helps to have visual images to look at when describing your scenes. You may have chosen a gritty urban streetscape, a desert SciFi terrain, a remote manor house in the Scottish Highlands, or a sheep farm down under. If you are lucky enough to be able to travel to the place and truly absorb the sights, smells, and sounds, you are ahead of the game.

If not, the beautiful thing about the internet age is you don’t have to leave your house to research them. There are travel channels and brochures, DVDs, and movies set in specific locales for you to investigate. It won’t give you the smells, sounds, and tastes, but it is better than making it up entirely in your head.

Thanks to Google Maps and other satellite mapping programs, you can now zoom in and do a 360-degree pan of the area. While it doesn’t allow you to peek inside the windows, you can stroll through a neighborhood in Paris, London, or Peoria for free.

For interior scenes, you can find images through internet search engines. You can find examples of log cabins, Victorian parlors, industrial warehouses, and suburban homes. Tourist sites and real estate sites offer visual tours.

For my current project I needed a Victorian stage and the exterior and interior of a Victorian manor house. Some tours of stately homes offered floor plans. I will create a fictional manor house utilizing the rich details I discovered.

By zooming along England’s coast I found the town of Graves End. Perfect location name for a mystery and close enough to London that my investigators could easily go there by coach. A little more digging and I found it was on the coach line and had people arriving from London several times a day. Of course, Google maps shows a very modern Graves End, but I did find an early map of it as well as illustrations.

Sadly, I cannot afford to go to Graves End and I’d need the Tardis to return to Victorian times. I’ll have to settle for imagining the way it smells and sounds and the way it might have been. But if I hadn’t been scouting for locations, I would never have known it was there.

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 6/24/2013

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

novel,

scene,

darcy's books,

chapter,

how to write,

opening,

start,

begin,

opening line,

Add a tag

START YOUR NOVEL

Six Winning Steps Toward a Compelling Opening Line, Scene and Chapter

- 29 Plot Templates

- 2 Essential Writing Skills

- 100 Examples of Opening Lines

- 7 Weak Openings to Avoid

- 4 Strong Openings to Use

- 3 Assignments to Get Unstuck

- 7 Problems to Resolve

The Math adds up to one thing: a publishable manuscript.

Download a sample chapter on your Kindle.

My latest Fiction Notes book is now available!

Six Winning Steps Toward a Compelling Opening Line, Scene and Chapter

You want to write a novel, but you don’t know where to start. You have a great idea and—well, that’s all. This book explains the writing process of starting a novel in six winning steps.

CHAPTERS

- Starting the Journey

- Why Editors Focus on Page 1

- STEP ONE: Clarify Your Idea

- STEP TWO: Review Your Skills

- STEP THREE: Plan the Opening Chapter

- STEP FOUR: Plan the Opening Line

- STEP FIVE: Now, Write!

- STEP SIX: Revise

Writing teacher and author, Darcy Pattison, is the author of NOVEL METAMORPHOSIS: Uncommon Ways to Revise, How to Write a Children’s Picture Book, and The Book Trailer Manual. She brings extensive experience in teaching writing to this exciting new book and helps you get started with the creative writing process.

Read a Sample Chapter

Jane Friedman posted Chapter 2 on June 10, 2013 and you can read on her blog. Or go here to download a sample chapter on your Kindle.

Confidence to Begin Your Novel

- 29 Plot Templates

- 2 Essential Writing Skills

- 100 Examples of Opening Lines

- 7 Weak Openings to Avoid

- 4 Strong Openings to Use

- 3 Assignments to Get Unstuck

- 7 Problems to Resolve

The Math adds up to one thing: a publishable manuscript.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

In 1999, Darcy Pattison started working with fiction authors on revising their novels. In order to come to a Novel Revision Retreat, participants need a complete draft of a novel and we spent an intensive weekend revising. The results? Many published novels, including Hattie Big Sky by Kirby Larson, winner of the Newbery Honor award.

Now, I am turning to beginning writers and bringing order to the writing process. If you start well, you have a better chance of writing a publishable manuscript—and needing fewer revisions. Start Your Novel is a natural extension of my teaching of fiction and will get you past the terror of the blank page.

Now available:

Please do me a favor!

As you know, reviews are extremely important! Please, post your honest opinion about the book on Amazon, GoodReads, B&N or other online sites. It isn’t necessary to enjoy and profit from the writing help you’ll find in the book. But I would appreciate it. Thanks! Darcy

Your characters enter a scene. Something happens, preferably conflict. Now, stop and ask yourself, "What primed the pump?"

Hopefully one conflict scene leads to another conflict scene, but what if you are moving from one POV character to another or a great deal of time has elapsed in between scenes?

After you write a scene, take another look at it and consider what primed the pump. No one enters a situation as a blank canvas.

1) What was Dick doing or feeling immediately prior?

It may be obvious if Dick is moving between consecutive scenes. Whatever happened in Scene 3 primes Scene 4. A plot hole occurs when something happens in scene 3 and is never addressed again. You don’t have to waste a lot of page time explaining what happened in between if it isn’t essential. However, if Dick was upset in Scene 3 and is perfectly calm when we see him again in Scene 7, then something happened to diffuse his mood. You should probably reference it with a line of dialogue or interiority during the opening transition paragraph of the new scene.

2) What is each character’s mindset as the scene progresses?

Every character entering a scene has thoughts and feelings. Are they having a good day or bad day? It affects their receptiveness. Whatever happened in prior scenes could have bearing on the current scene. Conflicting emotions and situations prime the conflict pump. If Jane is happy and Dick is angry, they could trade moods quickly.

3) Has your scene been properly set up?

Have you brought up an important point that you let lapse? Are the characters conflicted over something that makes no sense because you forgot to mention it in a previous scene? You may have cause and effect plot holes. If so, you have some revision to do. Beta readers or critique partners can be invaluable in catching these. My groups calls it the "read the book in my head, not the one on paper" syndrome.

4) Where does your scene take place? Why?

Settings are often bland and add nothing. You add value when you set the scene in a place that heightens tension. It has to be logical and organic. Don’t do it because “the script called for it.” If your couple is having an argument at home in the kitchen, it is realistic but is it interesting? Is the kitchen the best place for the argument? Can you make the setting more awkward for them? Say, a PTA meeting or on a crowded bus ride home?

5) Who is present?

You can have intense dialogue between two characters while they are alone. You add tension when they are striving to not be overheard or are wearing forced smiles at a formal function surrounded by family or coworkers. When two people are focused on each other, the crowd has a way of disappearing. They sometimes forget that other ears are listening. Being overheard can create future conflict. Having to behave decorously can force them to resume the conversation at another time, thus priming the pump for a future scene.

Consider not only the timeline of your story but how the timeline of the conflicts prime the pump. What happens immediately before can be as important as what happens during and immediately after.

Conflict occurs between characters when there is a breakdown in communication. You don’t need a broken cell phone or a disabled internet to create problems for your characters. When someone’s life or emotional welfare is at stake, breakdowns in communication are treacherous.

Use communication failures to ratchet the tension and create obstacles that are resolved in future scenes.

1) Mental block.

If Jane or Sally offers an important bit of information, Dick may dismiss it outright because it doesn’t fit within his belief system. They can talk all day. It won’t matter. Use this to point Dick in the wrong direction. Later, when he is more willing to listen, their information could save the day.

2) Different meanings.

Terms such as coward/courageous, allowed/ forbidden, acceptable/unacceptable, relationship/friendship, good/bad could have entirely different meanings for Dick, Sally, and Jane. Misunderstandings in this realm create hurt feelings, perhaps the desire for retaliation. Use this misunderstanding to turn a friend into an enemy or a helper into a hinderer. When you want to turn the story around, resolve it.

3) Too much information.

Sometimes less really is more. The more options and information thrown at Dick, the harder it can be for him to decide or act. He can’t possibly keep it all straight. Friends and foes can later supply Dick with information he overlooked or details he forgot. Plant the seed in one scene, sprout it in another, perhaps appreciate the fully beauty of it in a third.

4) Distraction.

Dick may not listen when his mind is on something else, missing the fact that Sally or Jane offered him an important piece of the puzzle. They can later remind him of it when it is crucial, with or without the “I told you so.”

5) Time crunch.

If Dick is in a rush, he might forget to say the right thing, tell the correct people, or leave out important facts. His terse delivery may chafe. This can infuriate and confuse Sally or Jane. It could leave them unwilling to help him or create negative backlash in a future scene.

6) Emotion Commotion.

If Sally or Jane approaches Dick in a heightened state of emotion — be it anger, passion, exhaustion, sadness, or drunkenness — Dick may dismiss the content as irrational. In a later scene, you can make Dick wish he had listened.

Communication breakdowns create interpersonal conflict at scene and overall story level and believable tension between characters. Have fun with it, but make it count.

It's becoming somewhat of an obsession but one in which Joe McKenna and his friends would most likely approve.

Added some more dialogue to "Old Soldiers" play today, although the ending is still up in the air. Wondering if it will ever have any solid substance.

"Really, Eleanor - we deserve better than this," Joe would comment upon my somewhat limited progress. "How much longer do we have to wait. It's been almost four years, now."

It's not for lack of trying. During sleepless nights, Joe and his friends plus the other characters pop in to say hello. Too bad that can't offer advice.

I'm fortunate to be a visual writer and see my words actually come to life and play out in the various scenes. Problems arise when I re-read the existing story line and the realization that something is awry. For example, my dilemma today was whether or not it's logical for a young character to be a great grandson and how old should he be? Then there is the issue of which war Joe and his friends were in.

This is followed by the dreaded 2-R's - Re-write and a Re-thinking - after which ennui sets in accompanied by self-doubt as to whether it will ever be finished. The problem is that I can't let it go for whatever reason. In writing my two other full plays that took approximately a year and-a-half to two years to complete, they seemed to write themselves. The two are so familiar to me that I can quote lines and passages from both.

One of my biggest concerns as expressed on numerous occasions that may be a contributing factor to the delay, is using the format for radio. The issue of having sufficient sound effects is always there. The dialogue is strong and if it was performed on stage would offer an interesting piece of theatre. However, my main objective is, as it always has been, to finish the play once and for all. And therein lays the problem.

By:

Paula Becker,

on 12/17/2012

Blog:

Whateverings

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Links,

kids,

winter,

comics,

Christmas,

Illustration Friday,

snow,

cartoon,

General Illustration,

angel,

trees,

scene,

xmas,

paula j. becker,

paula becker,

childrens,

Cartoons & Comics,

season,

snowing,

paulajbecker,

Add a tag

A very apt Illustration Friday prompt for this week, as the snow begins to fall. Below if my contribution. Check out the others by clicking on the link above!

Every scene must end in disaster. Really? EVERY scene?

OK. Most scenes.

I only say that every scene must end in disaster because if I give writers wriggle room, they run with it. So, yes, let’s work on the premise that every scene must end in disaster. What disaster? How do you choose?

Progressions. In general, your disasters need to be some sort of progression from bad to worse to absolute worst. Look at your story to find the natural progressions and then try to exaggerate a bit. For example, if a ballerina wants to try out for a dance part, what would be the absolute worst? Showing up drunk, out of shape and sloppily dressed–looking and acting like a bum.

Is that too extreme? Probably. So, back off the Worst scenario to find something reasonable: an injured Achilles tendon; just recovering from emergency appendectomy; a secret habit of drinking; grieving from a family death or tragedy. I like to plan the worst possible then back off from that for about mid-story and back off from that for the story opening. Working backward from Worst seems to ensure for me that I actually GO to the Worst and don’t try to avoid it.

Multiple Disasters. Also think about the subplots and how each of their narrative arcs can add to the overall disasters. By the time you slot into your story plan the Bad/Worse/Worst for the main plot and for a couple subplots, then you’re on your way to every scene ending in disaster. Then, you’ll just have to find ways to create disasters for the extra needed scenes of your story.

Ambiguous Disasters

One tool in your toolbox should be the ambiguous disaster. This is when the character appears to win, but in the end, s/he doesn’t. In this scene from Good Will Hunting, Will, Chuckie and their gang go into a Harvard bar (warning: PG-13 for language). Chuckie tries to pick up a couple girls and a Harvard guy steps in to humiliate him. Will steps in, though, to humiliate the Harvard guy. On the surface, Will’s intelligence wins out; but in the end, the Harvard guy wins simply because society recognizes a Harvard degree over native intelligence. It’s a great example of an ambiguous disaster: Will wins on one level but utterly fails on another. It demonstrates (Show-Don’t-Tell) exactly what Will faces in the rest of the story: society’s expectations about intelligence and the role of a college education in getting jobs.

If you can’t see this video, click here.

So, while you must end each scene in a disaster, you can let your character have some level of success–just don’t let it go too far, too early. Remember the mantra: Bad, Worse, Worst.

You are thinking you need a fight scene in your novel. The most important question is “Why?” Your novel and the specific situation in a particular scene must demand some sort of physical interaction between characters. But don’t think that the physical is the end-all of the scene; instead, a fight scene is an opportunity to reveal character as the characters interact in a physical way. As with any scene, there should be a beginning, middle and end and somewhere in there, a pivot point where the story changes direction.

Let’s Fight: Basics of a Fight Scene

First, a fight scene must move the novel or story forward. The outcome of the fight must matter on a large enough scale, and yet on a small enough scale, too. That is, not so big that the story ends abruptly, but enough that something important changes. What is at stake (other than dying) and why is it important to the story?

It’s all about character. The stakes of the scene should be rooted in character, the fighters and/or the observers. It must reveal something about your character as the scene progresses. (beliefs, what is worth fighting for, fears, cowardice, courage, what the character is willing to do and what s/he won’t do, etc.). It can’t just be whacking each other over the head. It must matter to the story and to the character, both internal and external arcs.

Make it hard for the characters. Give the characters equal skills, so the fight relies on character qualities for its outcome. Be realistic here. For example, a child or teen may not be as strong as a burly man, but they may be faster. Think about how different skills can offset the opponent’s strength. You’ll ultimately have to figure out how the underdog might defeat a stronger foe; but it must be hard and must be believable.

Final Showdown. Hero must barely survive and must run out of options as the fight progresses.

In the final showdown, the Hero must go beyond his normal abilities, face some fear or do the unthinkable or impossible to survive. This isn’t a waltz. It’s a waltz of death. Maybe the death of a hope, a fear, an alternative, a love.

How to Write a Fight Scene

List possible actions. If you are doing a sword fight, they can thrust, jab, parry, dodge and so on. Are there alternate weapons, alternate settings, alternate methods? If so, list these and then rank them in order of danger or what is at stake. You’ll start the fight with the gentlest, most benign fighting and move toward more deadly methods. Rank not just weapons, but also settings and other methods of fighting. For example, settings may be more dangerous if the fight is in a swamp (deadly footing), a rainstorm (visibility and footing), an alley (dark, close quarters), etc. Be sure to consider all variables and start with the easiest and work up to the hardest. It may mean that one fight escalates through all these stages, or it may mean that early fights in a series of conflicts are easy lea

What is you realize that your opening scene is not working, but really, you can’t think of what to do next? You’re STUCK on that opening that you wrote and can’t imagine what to do next.

The problem is the same as always. The first draft of a story is to tell you what story you want to tell; every draft after that is to help you find the most dramatic way to tell that story.

Here’s one way to approach the problem of what scenes need to be included.

If you are writing a story about the Three Little Pigs, let’s make a list of possible scenes for the story.

Momma and Poppa pig meet

Momma and Poppa Pig court (sharing slops, watching the rooster, taking a roll in the mud togehter)

Momma and Poppa Pig marry

Momma and Poppa Pig enjoy their marriage night (Anything from G to X rated!

Momma Pig discovers she is expecting

Momma Pig tells Poppa Pig he’s going to be a Daddy

The birth of the three babies.

The babyhood of the babies (first time they suckle, weight at one month, first time they eat solid food, first time they fight over slops)

The teenage years of the three pigs (fighting over slops, barnyard tricks, etc.)

Momma and Poppa Pig decide to kick them out of the house

Telling the three little pigs they must leave

Three Pigs decide which road each will take

And so on and so on.

Usually, the story just jumps in when the pigs leave the house. But you COULD do any of this back story as a scene. And we could give just as detailed a list for the actual story.

And that’s the technique. Make a list of POSSIBLE scenes.

As you do this, think about which scenes will give the best range of developing the story you want to tell, with the emphasis you want.

If you are stuck on what opening scene you should write, list the ones that are possible, given the story you want to tell. The richer the list the stronger the possibilities, the better.

If you can’t tell immediately which scenes will work, well, at least you have some places to start writing. Start working through the scenes until you find the ones that excite you. Where do the characters hurt the most? Where is the conflict sharpest? Which is the most unusual?

In short, which is the most dramatic choice?

My novel is growing chapter by chapter.

Getting a chapter done.

Here’s a look at a typical process for writing a chapter of a book.

First, I look at the plot synopsis that I have already written. It tells me the bare bones of what happens in this chapter, but often few specifics. I have to decide setting, characters present, the scenes that will Show-Don’t-Tell the plot and get a certain tone or voice in my head.

Setting is often the first thing for me. I want the story to be grounded in a specific place. Not just “my house.” It needs to be the kitchen right after Mom has just burned toast. A specific place and a specific time. This includes time of year and for a historical or futuristic novel, might include the year and the culture around that year. Just deciding this helps ground me in where the scene takes place and what sorts of actions make sense here. In the smelly kitchen, it’s unlikely to find characters dressed up in evening clothes or pirates with treasure.

Next, I decide on a goal for a scene. Often by this time, I am writing notes to myself. I find that 750words.com exercises to be helping in sorting out what is important in this section of the story. What does my character want in this scene? Can I make it a deeper need, raise the stakes? What is the disaster at the end of the scene? What happened just before this scene (Mom burned the toast!)?

My writing process is messy, circular, imperfect.

Sometimes, the setting and

scene structure is clear and I just start writing and let the actions unfold as they will. Sometimes, though, I write out possible beats: what small actions could these characters take that will add up to the character seeking his/her goal?

Often, I write just a section of the scene and have to leave off because of time, or because I need more information. If needed, I research setting, events, actions, props; I free-write dialogue that might take place; I experiment and write a draft that I know is just a place-holder until I get something better done.

I like to write the scenes needed for a chapter before I stop to go back and reread. For this novel, that’s 1-3 scenes per chapter.

Later–maybe the next day–I come back and re-read everything and edit, change, omit, totally rewrite, rearrange: in short, I revise.

Then, I read everything from the beginning, looking for flow and pacing and trying to make sure the story has consistency in it’s tone and voice.

Finally, I start a new scene or chapter.

The process is messy, circular and imperfect. But in the end, it does produce a first draft. First drafts are to tell you what the story is about; second drafts are to figure out the most dramatic way to tell that story. I’m still figuring out the story of my WIP and for now, it’s going well. The process is working.

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 1/22/2012

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

zoom, scene, how to write, novel revision, sensory details, panorama, scan, focal length, novel, Add a tag

Have you signed up for 750words.com yet? Or will you try doing 750 words on paper? I’ve just completed my 20th day of doing 750 words! Have you signed up for 750words.com yet? Or will you try doing 750 words on paper? I’ve just completed my 20th day of doing 750 words!

Here’s another creative writing prompt for your 750 words, a challenge to write 750 words each day in January to better Think Like a Writer. The next three days of Thinking Like a Writer are all connected and I’ll explain it here, then just remind you of the prompts for the next two days.

A scan is a way to show a crowd scene economically, yet in an interesting way. It involves a series of small zooms: the quarterback’s mother is taping the game with a new video camera that she borrowed money to buy; the coach’s pencil is hovering over two names, trying to decide if he’ll start the injured quarterback or his backup; the head cheerleader is trying to shake off a headache and wondering if that red pill the quarterback gave her would help or not. In a short paragraph, you get the complexities of the crowd!

As always, start with the basic sensory details list, but this time you skip around. You can do full details for the coach, the quarterback’s mother, the quarterback, and the head cheerleader if you want; or you can do partials for each, but focus on getting great “telling details.” If you’re rusty on doing sensory details–and you have to fill out your 750 words anyway–go ahead and do the full sensory details list for each. Then you’ll have a wide selection to choose from as you Think Like a Writer.

And when would you use a Scan?

| |

NEW EBOOK

Available on

|

For more info, see writeapicturebook.com

Conflict is always good. It's good for our characters, and it's good for us as writers. Pushing ourselves through the hard scenes, the hard revisions, the tough first drafts, that's conflict. Overcoming conflict in ourselves and our writing forces us to become better at our craft the same way conflict forces our characters to become better, stronger, more interesting to our readers. And just as our characters don't always choose the right fork in the road, it often takes trial and error--and an eventual alignment of whatever planets guide our writerly feet--for us to find the right path through a story. As writers, we learn by reacting to a set of stimuli: a book read, a scene written, feedback received, or perhaps just the right combination of all of the above. Our characters learn because we put them in conflict with an antagonist, stick their butts in moral or mortal danger, and force them to fight their way back out. Learning how to do that to our characters credibly is the greatest thing we writers can learn. Because, in the end, for us and our characters both, fiction comes down to the credibility of stimulus and response. From the first page we write, our main character must want or need something specific. She either has a goal or a problem. The antagonist, on the other hand, wants something that will prevent the main character from getting what she wants. The battle between the two will wage, nearly equal, until it results in a climax that pits all the strength of one against all the intelligence and cunning of the other. How do we, as writers, get them to that point though? That's the trick. Pulling the reader by the heart from the beginning of the book to that climax, scene by scene, is the key to successful writing. Ultimately, a book isn't about beautiful descriptions or sparkling prose. It's about action and reaction, which is all a response to conflict. I like to reread craft books. I usually try to get through one a month, even if it is one that I have read before, because I get something new out of it every time. Just forcing myself to think about craft in a new way gives me time to think about whatever story I am working on from a different perspective. This weekend, I picked up Jack M. Bickham's SCENE AND STRUCTURE, which approaches conflict from the approach of both logical and emotional stimulus and response. Although Bickham focuses largely on scene, he also starts covers the cause and effect sequences that form the smallest elements of a story, the individual steps that begin to build the climb toward the climax. From the first scene in the book where the protagonist's journey begins with a the inciting incident, a stimulus, we writers have to provide a sound motivation for every action by every character. The more deeply motivated we can make the goals or problems, the more satisfying we can make the reader's experience, and ultimately, the more the reader will care about the outcome of the dilemma. Even less likeable characters are readable and redeemable so long as they are striving for something they desperately care about. One of the basic tenets of creating a powerful story is that the protagonist must want something external and also need something internal one or both of which need to be in opposition to the antag's goals and/or needs. By the time the book is over, a series of setbacks devised by the antag will have forced a choice between the protag's external want and that internal need to maximize the conflict. The protagonist must react credibly to each of those setbacks, and take action based on her perception and understanding of each new situation. Bickham points out that credibility results from understanding the stages of response. Ch

Here’s a question from a reader:

Is it ok to use dialogue to tell the main character about the fantasy world she just entered via her sidekick who lives there? I’m not sure how else to do it. Is there such a thing as too much dialogue?

Thanks for the question!

Where to Include Exposition

You’re really asking about a couple things. Exposition is the explanatory text that tells the reader about the setting, the time period, backstory, etc. It’s important that the reader know what’s going on and the tendency is to try to explain everything. You’re really asking about a couple things. Exposition is the explanatory text that tells the reader about the setting, the time period, backstory, etc. It’s important that the reader know what’s going on and the tendency is to try to explain everything.

But think about this: when you first meet someone, you know nothing of their back story, their history, how they reacted the first time they ate cotton candy, or whether or not they are scared of dogs. You don’t know their family history, or anything about their job or how well they do in school. You only know the immediate situation.

That’s what you must focus on, is the unfolding of scenes that tell you story.

But, you want to know how to get all that other stuff in there. Is it okay to tell it in dialogue? Maybe.

Unfortunately, little in fiction is set in stone. In general, though, you should trust your reader to understand implications of what you write. Maybe add in a line here or there of explanation, or occasionally a paragraph of description or just plain explanation. But overall, the exposition must be naturally worked into a story AS A SCENE UNFOLDS.

I’m emphasizing the use of scenes. A scene is something immediate happening; it includes action; it includes conflict; it includes immediate consequences. Nothing can interrupt the flow of that scene. In the aftermath of a scene, when the reader is following the character’s reactions to the scene, you might slip in a memory or flashback–if and only if it directly relates to the decision the character must make at this time.

Otherwise, sorry, the exposition must flow naturally.

Examples of Using Exposition

From The Green Glass Sea, by Ellen Klages, p. 43.

This is a story about the families of scientists who are developing the atom bomb. “The Hill” is the research facility in New Mexico where much of the action is set. Suze has just had lunch with mom and is trying to decide what to do for the afternoon:

Both her parents had always worked. Back in Berkeley, though, where they’d been professors at the university, they’d had regular hours. Here on the Hill, she was never sure when she would see them. Especially Mom. Suze missed having her around, which was unpatriotic, because whatever the scientists were working on was going to end the war, and she knew that was more important than playing cards.

Here, the exposition is slipped into the scene and also does a good job of characterizing Suze, who both misses her Mom and Dad, and feels the conflict of their patriotic duty. Usually, it’s better to just put the exposition into a paragraph like this, instead of trying to fit it into dialogue.

On the other hand, here’s a bit from The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, p. 91-92. In this futuristic reality TV show, children are supposed to kill each other in order to gain food for

Since Marissa and I are still on blog hiatus, we're not picking contest winners until we get back. In the meantime, here's a repost of an earlier article I wrote while I was thinking about bringing scenes to life in a novel. For me, the best scenes are visual. The truly great scenes, the ones I remember from novels by other writers, play in my mind like a film. I can see the action, but unlike film, a novel also lets me smell the coffee, and taste the fear or sorrow. I can get closer to the character than I would in a film, so the emotion is right there close to my heart, and it stays there. But how do I get to that point as a writer? How does any writer create scenes that are memorable, visual, and visceral? First, the StructureWhat is a scene? A scene is a segment of a novel. It should: - Establish a specific goal the main character wants to achieve.

- Develop conflict that blocks the character from getting what she wants.

- Add complications to the plot as the character fails to reach her goal and must react to disaster.

Along the way, it also: - Shows action as it unfolds.

- Has a beginning, middle, and end.

- Contains concrete turning points, both external and internal.

- Moves the story forward within the overall conflict and dilemma of the novel.

- Provides one or more pieces of new information.

- Introduces characters or reveals something about characters previously introduced.

- Advances the theme.

- Leaves the reader with a specific emotion and a reason to continue reading.

The scene is then followed by the aftermath: - The emotional response the character has to the failure she just experience before she dusts herself off and looks for a new solution.

- The dilemma posed when none of the possible solutions available will solve the problem.

- The risky decision she finally reaches that seems like the lesser among the available evils.

These days, the aftermath may occur within the scene, and it may occur at each of the turning points. Of course, the risky decision leads to a new goal, which initiates and helps us anticipate what will happen in a new scene, and so on. But even within a scene or aftermath, characters constantly gain new goals as complications are piled on. They emote, react, and make decisions based on those goals while still trying to attain the overall objective. All of this creates suspense, tension, and an urgent need for the reader to turn the pages. Then, the SettingOnce you know what's happening in your scene and why, you need to decide where the scene takes place. That's one of the good things about being a writer--you can travel anywhere with a few strokes on your keyboard. But there are a few places you shouldn't set a scene. Don't set it in: - Empty air.

- A generic version of a location.

- An unpopulated or unfurnished location.

- The same location you've already used for fifty other scenes.

- A place that won't add meaning to your story.

Great settings are specific and unique, but they aren't just window dressing. The best overall settings for a novel are in a state of change. Effective scene settings can represent and underscore the stakes of that change. Settings are the workhorses of your scene. Chosen well, scene settings: - Create atmosphere.

- Help advance the plot.

- Illuminate your characters.

- Add complications and impediments to keep characters from reaching their goals.

- Underscore the potential consequences of failing to fix the overall novel issue or problem.

- Provide a framework wit

.png.jpg?picon=4257)

By: Diana Hurwitz,

on 6/17/2011

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

conflict, fiction, writing, characters, craft, optimism, scene, tension, decisions, pessimism, Add a tag

Is the glass half empty or half full? It depends on your outlook, unless your character is nit-picking and breaks out a ruler to measure fractions of millimeters to prove it one way or the other. It is conjectured that optimism drew us forth from caves to explore the wild. We would not have evolved without it and would not continue to thrive without it. Imagining a better world inspires us to work toward one. Optimism allows us to take a seat in a car, train or plane. It encourages us to date, walk down the aisle and parent. It inspires inventions, technology and religions. Optimism is based on hopes of a future reward whether it is tied to a relationship, a resource, or global climate change. If there is no hope, why bother? Ironically, not all religions are fueled by optimism. Some take a very pessimistic view of the world. It is only by jumping through a certain set of hoops in this world that you can achieve ascendance to a better world. It offers the carrot of eternal life in a beautiful world while existing in a terrible world. Optimism allows Dick to project positively into the future and to examine “what happens next” before it happens. The mind is capable of considering what has happened, what is happening now and what will happen in the future. The more positive Dick feels, the more likely he is to attempt something. The more negative he feels, the less likely he is to attempt it. Your protagonist, antagonist, friends and foes can view the overall story problem and scene obstacle from one of two positions: (1) They can believe they will be successful no matter how many attempts it takes, or (2) They can believe they will fail and will be frustrated by how many attempts are made. Overturning what they believed creates tension and new complications. Pair an optimist and a pessimist and they will disagree and irritate each other as they work to overcome the obstacle. Optimism and pessimism can be the obstacle in a tense conversation. If Dick needs Sally to adopt his point of view, she can fight it tooth and nail out of fear of negative outcome. They can be talking about breaking into someone’s office, taking a vacation to Istanbul or trying to stop a serial killer from reaching his next target. The level of optimism Dick has will affect his decisions when he is faced with choices. It’s easy if Dick has to choose between a perceived negative and a perceived position option. He will, of course, jump on the positive option even if it ends up being the wrong thing. If his perception is faulty, you have further complications. It’s interesting to give Dick two negative options (both with impossible outcomes) or two positive options (both with favorable outcomes). You define his character by showing how he reaches a conclusion. Most of the time, once Dick has decided on an option, he will feel better. He will reinforce, in his own mind, the rightness of choice A and will begin to devalue choice B.

By: Heather Hedin Singh,

on 2/4/2011

Blog: StorySleuths

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Scene, Touch Blue, Add a tag

Dear Allyson, I’m so happy to be back to StorySleuths after our hiatus this fall. I hope your writing has been going well.

This month, we’re reading Touch Blue by Cynthia Lord, which starts when Tess Brooks and her family bring a foster child named Aaron into their home on the island of Bethsaida, Maine. This is a story about belonging, family, community, and luck.

Speaking of luck, the timing for me to dig into this month’s book couldn’t be more perfect. Touch Blue features several “big scenes” similar to the scene I’m currently writing in my novel.

What is a big scene? Sandra Scofield, author of The Scene Book, describes big scenes as “scenes that have many characters.” These would include parties, weddings, holidays, and other gatherings.

These scenes are difficult to write, even for masters. Here, Scofield shares a snippet from a letter by Gustave Flaubert describing his challenge in creating a scene in Madame Bovary: “Never in my life have I written anything more difficult than what I am doing now—trivial dialogue. I have to portray, simultaneously and in the same conversation, five or six characters who speak, several others who are spoken about, the scene, and the whole town… and in the midst of all that, I have to show a man and a woman who are beginning… to fall in love with each other…” (Scofield, p. 156).

A lot to accomplish!

Scofield says that big scenes take as much planning as “the preparation of a huge Christmas dinner, a school play, or any other event that has many components.” Who is there? Where are they? Why have they gathered? What are they doing?

Chapter Two of Touch Blue, Aaron’s arrival on the island, is an ambitious big scene. Let’s step through the scene beat by beat to see how Lord introduces the reader to the characters, the situation, and the island.

1. Libby and Tess arrive at the crowded wharf.

0 Comments on BIG SCENES: Touch Blue (Post #1) as of 1/1/1900

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 11/30/2010

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

novel, character, plot, scene, write, revise, edit, how to, novel revision, 30 days, stronger, Add a tag

View Next 25 Posts

|

Used to pay attention to this, now, thankfully, it comes naturally. Or so I'd like to think. :0)

Carole, ah the joys of unconscious mastery. :) Excellent!

Wonderful post! I tend to agree with Carole. I don't think I'm exactly where she is yet, but recognizing the need or lack of some of what you mentioned above comes naturally now. Makes a world of difference.

Happy Thanksgiving, ladies!

Sherry, Happy Thanksgiving! I hope you're doing something amazing. Take the time to celebrate coming so far in the writing, too! :D

Great post. I love the idea that you can deviate from expected norms, but your craft has to be good enough to execute it. Something to strive for!

Bluestocking, that's always the risk, isn't it? :Q You have to know when you can pull it off, and you need a compelling reason to try it that way. There's always the chance that you'll fail. But when you nail it, there's room for magic.

I think I've done it unconsciously at first, and many times not correctly, but the more I read books on writing, the more I see why and how to manipulate scenes. I also think that as a writer absorbs craft books and does a lot of writing, it goes back to being an unconscious act—like the development of good habits.

Nice post, but "2. no, the protag" looks like an unfinished sentence. I'm not sure if it's a typo, a victim of copy-and-paste, or what.

Interesting about the "hierarchy" of reactions. Lately, I'm concentrating more on the emotions, which can be a delicate operation.

Beth, absolutely it becomes unconscious to a certain point, but its really easy to accidentally reverse those stimulus response pairs. Simultenaety especially ends up leaving small holes. Or we go in to change up our sentence construction, and inadvertently put the response ahead of the stimulous in a sentence. I just crawled over a couple of chapters and found an instance. It all depends on how carefully we look, or I guess how attentive we are, or what we happen to be focusing on during our edits.

CO -- Great catch! Thank you. I did have a formatting and cut/paste issue this morning.

Catherine, emotions are tough. Hitting them just right can make or break a piece of writing. Good luck!

PLEASE PLEASE...can you re-post this article on Stimulus and Response: The Writer's Path through Story. All I get is a blank page when I try to follow your link. It was so informative and now I can't find it again to refer to.

Sheri,

I'm so sorry you are having problems. Can you see it yet?