new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: this day in history, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 51 - 75 of 141

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: this day in history in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Kirsty,

on 8/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

Belgium,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

belgian,

wwi,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

Sir Edward Grey,

Poincaré,

the july crisis,

declaration of war,

august 1914,

British cabinet,

coasts,

garitan,

brocqueville,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

At 7 a.m. Monday morning the reply of the Belgian government was handed to the German minister in Brussels. The German note had made ‘a deep and painful impression’ on the government. France had given them a formal declaration that it would not violate Belgian neutrality, and, if it were to do so, ‘the Belgian army would offer the most vigorous resistance to the invader’. Belgium had always been faithful to its international obligations and had left nothing undone ‘to maintain and enforce respect’ for its neutrality. The attack on Belgian independence which Germany was now threatening ‘constitutes a flagrant violation of international law’. No strategic interest could justify this. ‘The Belgian Government, if they were to accept the proposals submitted to them, would sacrifice the honour of the nation and betray at the same time their duties towards Europe.’

When the British cabinet reconvened later that morning at 11 a.m. there were now four ministers prepared to resign over the issue of British intervention. Their discussion lasted for three hours, at the end of which they agreed on the line to be taken by Sir Edward Grey when he addressed the House of Commons at 3 p.m. ‘The Cabinet was very moving. Most of us could hardly speak at all for emotion.’

Grey began his address to the House by explaining that the present crisis differed from that of Morocco in 1912. That had been a dispute which involved France primarily, to whom Britain had promised diplomatic support, and had done so publicly. The situation they faced now had originated as a dispute between Austria and Serbia – one in which France had become engaged because it was obligated by honour to do so as a result of its alliance with Russia. But this obligation did not apply to Britain. ‘We are not parties to the Franco-Russian Alliance. We do not even know the terms of that Alliance.’

But, because of their now-established friendship, the French had concentrated their fleet in the Mediterranean because they were secure in the knowledge that they need not fear for the safety of their northern and western coasts. Those coasts were now absolutely undefended. ‘My own feeling is that if a foreign fleet engaged in a war which France had not sought, and in which she had not been the aggressor, came down the English Channel and bombarded and battered the undefended coasts of France, we could not stand aside and see this going on practically within sight of our eyes, with our arms folded, looking on dispassionately, doing nothing!’ The government felt strongly that France was entitled to know ‘and to know at once!’ whether in the event of an attack on her coasts it could depend on British support. Thus, he had given the government’s assurance of support to the French ambassador yesterday.

There was another, more immediate consideration: what should Britain do in the event of a violation of Belgian neutrality? He warned the House that if Belgium’s independence were to go, that of Holland would follow. And what…

‘If France is beaten in a struggle of life and death, beaten to her knees, loses her position as a great Power, becomes subordinate to the will and power of one greater than herself’? If Britain chose to stand aside and ‘run away from those obligations of honour and interest as regards the Belgian Treaty, I doubt whether, whatever material force we might have at the end, it would be of very much value…’

‘I do not believe for a moment, that at the end of this war, even if we stood aside and remained aside, we should be in a position, a material position, to use our force decisively to undo what had happened in the course of the war, to prevent the whole of the West of Europe opposite to us—if that had been the result of the war—falling under the domination of a single Power, and I am quite sure that our moral position would be such as to have lost us all respect.’

While Grey was speaking in the House the king and queen were driving along the Mall to Buckingham Palace in an open carriage, cheered by large crowds. In Berlin the Russian ambassador was being attacked by a mob wielding sticks, while the German chancellor was sending instructions to the ambassador in Paris to inform the French government that Germany considered itself to now be ‘in a state of war’ with France. At 6 p.m. the declaration was handed in at Paris:

‘The German administrative and military authorities have established a certain number of flagrantly hostile acts committed on German territory by French military aviators. Several of these have openly violated the neutrality of Belgium by flying over the territory of that country; one has attempted to destroy buildings near Wesel; others have been seen in the district of the Eifel, one has thrown bombs on the railway near Karlsruhe and Nuremberg.’

The French president welcomed the declaration. It came as a relief, Poincaré said, given that war was by this time inevitable.

‘It is a hundred times better that we were not led to declare war ourselves, even on account of repeated violations of our frontier…. If we had been forced to declare war ourselves, the Russian alliance would have become a subject of controversy in France, national [élan?] would have been broken, and Italy may have been forced by the provisions of the Triple Alliance to take sides against us.’

When the British cabinet met again briefly in the evening they had before them the text of the German ultimatum to Belgium and the Belgian reply to it. They agreed to insist that the German government withdraw the ultimatum. After the meeting Grey told the French ambassador that if Germany refused ‘it will be war’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 8/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

Lloyd George,

*Featured,

Luxembourg,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

Asquith,

Sir Edward Grey,

the july crisis,

Paul Cambon,

Treaty of London of 1867,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Confusion was still widespread on the morning of 2 August 1914. On Saturday Germany and France had joined Austria-Hungary and Russia in announcing their general mobilization; by 7 p.m. Germany appeared to be at war with Russia. Still, the only shots fired in anger consisted of the bombs that the Austrians continued to shower on Belgrade. Sir Edward Grey continued to hope that the German and French armies might agree on a standstill behind their frontiers while Russia and Austria proceeded to negotiate a settlement over Serbia. No one was certain what the British would do – especially not the British.

Shortly after dawn Sunday German troops crossed the frontier into the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Trains loaded with soldiers crossed the bridge at Wasserbillig and headed to the city of Luxembourg, the capital of the Grand-Duchy. By 8.30 a.m. German troops occupied the railway station in the city centre. Marie-Adélaïde, the grand duchess, protested directly to the kaiser, demanding an explanation and asking him to respect the country’s rights. The chancellor replied that Germany’s military measures should not be regarded as hostile, but only as steps to protect the railways under German management against an attack by the French; he promised full compensation for any damages suffered.

The neutrality of Luxembourg had been guaranteed by the Powers in the Treaty of London of 1867. The prime minister immediately protested the violation at Berlin, Paris, London, and Brussels. When Paul Cambon received the news in London at 7.42 a.m. he requested a meeting with Sir Edward Grey. The French ambassador brought with him a copy of the 1867 treaty – but Grey took the position that the treaty was a ‘collective instrument’, meaning that if Germany chose to violate it, Britain was released from any obligation to uphold it. Disgusted, Cambon declared that the word ‘honour’ might have ‘to be struck out of the British vocabulary’.

The cabinet was scheduled to meet at 10 Downing Street at 11 a.m. Before it convened Lloyd George held a small meeting of his own at the chancellor’s residence next door with five other members of cabinet. They were untroubled by the German invasion of Luxembourg and agreed that, as a group, they would oppose Britain’s entry into the war in Europe. They might reconsider under certain circumstances, however, ‘such as the invasion wholesale of Belgium’.

When they met the cabinet found it almost impossible to decide under what conditions Britain should intervene. Opinions ranged from opposition to intervention under any circumstances to immediate mobilization of the army in anticipation of despatching the British Expeditionary Force to France. Grey revealed his frustration with Germany and Austria-Hungary: they had chosen to play with the most vital interests of civilization and had declined the numerous attempts he had made to find a way out of the crisis. While appearing to negotiate they had continued their march ‘steadily to war’. But the views of the foreign secretary proved unacceptable to the majority of the cabinet. Asquith believed they were on the brink of a split.

After almost three hours of heated debate the cabinet finally agreed to authorize Grey to give the French a qualified assurance. The British government would not permit the Germans to make the English Channel the base for hostile operations against the French.

While the cabinet was meeting in the afternoon a great anti-war demonstration was beginning only a few hundred yards away in Trafalgar Square. Trade unions organized a series of processions, with thousands of workers marching to meet at Nelson’s column from St George’s circus, the East India Docks, Kentish Town, and Westminster Cathedral. Speeches began around 4 p.m. – by which time 10-15,000 had gathered to hear Keir Hardie and other labour leaders, socialists and peace activists. With rain pouring down, at 5 p.m. a resolution in favour of international peace and for solidarity among the workers of the world ‘to use their industrial and political power in order that the nations shall not be involved in the war’ was put to the crowd and deemed to have carried.

If the British cabinet was divided, so however were the people of London. When the crowd began singing ‘The Red Flag’ and the ‘Internationale’ they were matched by anti-socialists and pro-war demonstrators singing ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Rule Britannia’. When a red flag was hoisted, a Union Jack went up in reply. Part of the crowd broke away and marched a few hundred feet to Admiralty Arch where they listened to patriotic speeches. Several thousand marched up the Mall to Buckingham Palace, singing the national anthem and the Marseillaise. The King and the Queen appeared on the balcony to acknowledge the cheering crowd. Later that evening demonstrators gathered in front of the French embassy to show their support.

The anti-war sentiment, which was still strong among labour groups and socialist organizations in Britain, was rapidly dissipating in France. On Sunday morning the Socialist party announced its intention to defend France in the event of war. The newspaper of the syndicalist CGT declared ‘That the name of the old emperor Franz Joseph be cursed’; it denounced the kaiser ‘and the pangermanists’ as responsible for the war. In Germany three large trade unions did a deal with the government: in exchange for promising not to go on strike, the government promised not to ban them. In Russia, organized opposition to war practically disappeared.

Shortly before dinner that evening the British cabinet met once again to decide whether they were prepared to enter the war. The prime minister had received a promise from the leader of the Unionist opposition, Andrew Bonar Law, that his party would support Britain’s entry into the war. Now, if the anti-war sentiment in cabinet led to the resignation of Sir Edward Grey – and most likely of Asquith, Churchill and several others along with him – there loomed the likelihood of a coalition government being formed that would lead Britain into war anyway.

While the British cabinet were meeting in London they were unaware that the German minister at Brussels was presenting an ultimatum to the Belgian government at 7.00 p.m. The note contained in the envelope claimed that the German government had received reliable information that French forces were preparing to march through Belgian territory in order to attack Germany. Germany feared that Belgium would be unable to resist a French invasion. For the sake of Germany’s self-defence it was essential that it anticipate such an attack, which might necessitate German forces entering Belgian territory. Belgium was given until 7 a.m. the next morning – twelve hours – to respond.

Within the hour the prime minister took the German note to the king. They agreed that Belgium could not agree to the demands. The king called his council of ministers to the palace at 9 p.m. where they discussed the situation until midnight. The council agreed unanimously with the position taken by the king and the prime minister. They recessed for an hour, resuming their meeting at 1 a.m. to draft a reply.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 8/1/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

war,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

The choice between war and peace hung in the balance on Saturday, 1 August 1914. Austria-Hungary and Russia were proceeding with full mobilization: Austria-Hungary was preparing to mobilize along the Russian frontier in Galicia; Russia was preparing to mobilize along the German frontier in Poland. On Friday evening in Paris the German ambassador had presented the French government with a question: would France remain neutral in the event of a Russo-German war? They were given 18 hours to respond – until 1 p.m. Saturday. In St Petersburg the German ambassador presented the Russian government with another demand: Russia had 12 hours – until noon Saturday – to suspend all war measures against Germany and Austria-Hungary or Germany would mobilize its forces.

But they were also extraordinarily close to peace. Russia and Austria had resumed negotiations in St Petersburg at the behest of Britain, Germany, and France. Austria had declared publicly and repeatedly that it did not intend to seize any Serbian territory and that it would respect the sovereignty and independence of the Serbian monarchy. Russia had declared that it would not object to severe measures against Serbia as long its sovereignty and independence were respected. Surely, when the two of them were agreed on the fundamental principles involved, a settlement was still within reach?

In London the cabinet met at 11 a.m. for 2 1/2 hours. The discussion was devoted exclusively to the crisis. Ministers were badly divided. Winston Churchill was the most bellicose, demanding immediate mobilization. At the other extreme were those who insisted that the government should declare it would not enter the war under any circumstances. According to the prime minister, Asquith, this was ‘the view for the moment of the bulk of the party’. Grey threatened to resign if the cabinet adopted an uncompromising policy of non-intervention.

One cabinet minister proposed a solution to their dilemma: they should put the onus on Germany. Intervention should depend on whether Germany launched a naval attack on the northern coast of France or violated the independence of Belgium. But his suggestion raised more questions: did Britain have the duty, or merely the right, to intervene if Belgian neutrality were violated? If German troops merely ‘passed through’ Belgium in order to attack France, would this constitute a violation of neutrality? The meeting was inconclusive.

In Berlin the Kaiser was approving the note to be handed to Russia later that day, if it failed to respond positively to the demand that it demobilize: ‘His Majesty the Emperor, my August Sovereign, accepts the challenge in the name of the Empire, and considers himself as being in a state of war with Russia’.

An hour after despatching this telegram another arrived in Berlin from the tsar. Nicholas said he understood that, under the circumstances, Germany was obliged to mobilize, but he asked Wilhelm to give him the same guarantee that he had given Wilhelm: ‘that these measures DO NOT mean war’ and that they would continue to negotiate ‘for the benefit of our countries and universal peace dear to our hearts’.

After meeting with the cabinet, Grey continued to believe that peace might be saved if only a little time could be gained before shooting started. He wired Berlin to suggest that mediation between Austria and Russia could now commence. While promising that Britain abstain from any act that might precipitate matters, he refused to promise that it would remain neutral.

But Grey also refused to promise any assistance to France: Germany appeared willing to agree not to attack France if France remained neutral in a war between Russia and Germany. If France was unable to take advantage of this offer ‘it was because she was bound by an alliance to which we were not parties, and of which we did not know the terms’. Although he would not rule out assisting France under any circumstances, France must make its own decision ‘without reckoning on an assistance that we were not now in a position to give’.

The French ambassador was shocked. He refused to transmit to Paris what Grey had told him, proposing instead to tell his government that the British cabinet had yet to make a decision. He complained that France had left its Atlantic coast undefended because of the naval convention with Britain in 1912 and that the British were honour-bound to assist them. His complaint fell on deaf ears. He staggered from Grey’s office into an adjoining room, close to hysteria, ‘his face white’. Immediately after the meeting he met with two influential Unionists, bitterly declaring ‘Honour! Does England know what honour is’? ‘If you stay out and we survive, we shall not move a finger to save you from being crushed by the Germans later.’

Earlier in Paris General Joffre, chief of the general staff, threatened to resign if the government refused to order mobilization. He warned that France had already fallen two days behind Germany in preparing for war. The cabinet, although divided, agreed to distribute mobilization notices that afternoon at 4 p.m. They agreed, however, to maintain the 10-kilometre buffer zone: ‘No patrol, no reconnaissance, no post, no element whatsoever, must go east of the said line. Whoever crosses it will be liable to court martial and it is only in the event of a full-scale attack that it will be possible to transgress this order’.

By 4 p.m. Russia had yet to reply to the German ultimatum that expired at noon. Falkenhayn, the minister of war, persuaded Bethmann Hollweg to go with him to see the Kaiser and ask him to promulgate the order for mobilization. At 5 p.m., at the Berlin Stadtschloss, the mobilization order sat on a table made from the timbers of Nelson’s Victory. As the Kaiser signed it, Falkenhayn declared ‘God bless Your Majesty and your arms, God protect the beloved Fatherland’.

News of the German declaration of war on Russia spread quickly throughout St Petersburg immediately following the meeting between Pourtalès and Sazonov. Vast crowds began to gather on the Nevsky Prospekt; women threw their jewels into collection bins to support the families of the reservists who had been called up. By 11.30 that night around 50,000 people surrounded the British embassy calling out ‘God save the King’, ‘Rule Britannia’, and ‘Bozhe Tsara Khranie’ [God save the Tsar].

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/31/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

World,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Berchtold,

Sir Edward Grey,

René Viviani,

Bethmann Hollweg,

Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf,

Helmuth Johann Ludwig von Moltke,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Although Austria had declared war, begun the bombardment of Belgrade, and announced the mobilization of its army in the south, negotiations to reach a diplomatic solution continued. A peaceful outcome still seemed possible: a settlement might be negotiated directly between Austria and Russia in St Petersburg, or a conference of the four ‘disinterested’ Great Powers in either London or Berlin might mediate between Austria and Russia.

The German chancellor worried that if Sir Edward Grey succeeded in restraining Russia and France while Vienna declined to negotiate it would be disastrous; it would appear to everyone that the Austrians absolutely wanted a war. Germany would be drawn in, but Russia would be free of responsibility. ‘That would place us in an untenable situation in the eyes of our own people’. He instructed the ambassador in Vienna to advise Austria to accept Grey’s proposal.

In Vienna at 9 a.m. Berchtold convened a meeting of the common ministerial council, explaining that the Grey proposal for a conference à quatre was back on the agenda and that the German chancellor was insisting that this must be carefully considered. Bethmann Hollweg was arguing that Austria’s political prestige and military honour could be satisfied by the occupation of Belgrade and other points, while the humiliation of Serbia would weaken Russia’s position in the Balkans.

Berchtold warned that in such a conference France, Britain, and Italy were likely take Russia’s part and that Austria could not count on the support of the German ambassador in London. If everything that Austria had undertaken were to result in no more than a gain in ‘prestige’, its work would have been in vain. An occupation of Belgrade would be of no use; it was all a fraud. Russia would pose as the saviour of Serbia – which would remain intact – and in two or three years they could expect the Serbs to attack again in circumstances far less favourable to Austria. Thus, he proposed to respond courteously to the British offer while insisting on Austria’s conditions and avoiding a discussion of the merits of the case. The ministers agreed.

The British cabinet also met in the morning to consider France’s request for a promise of British intervention before Germany attacked. The cabinet divided into three factions: those who opposed intervention, those who were undecided, and those who wished to intervene. Only two ministers, Grey and Churchill, favoured intervention. Most agreed that public opinion in Britain would not support them going to war for the sake of France. But opinion might shift if Germany were to violate Belgian neutrality. Grey was instructed to request – from both Germany and France – an assurance that they would respect the neutrality of Belgium. They were not prepared to give France the promise of support that it had asked for; one of them concluded ‘that this Cabinet will not join in the war’.

Grey wired to Berlin to ask whether Germany might be willing to sound out Vienna, while he sounded out St Petersburg, on the possibility of agreeing to a revised formula that could lead to a conference. Perhaps the four disinterested Powers could offer to Austria to undertake to see that it would obtain ‘full satisfaction of her demands on Servia’ – provided that these did not impair Serbian sovereignty or the integrity of Serbian territory. Russia could then be informed by the four Powers that they would undertake to prevent Austrian demands from going to the length of impairing Serbian sovereignty and integrity. All Powers would then suspend further military operations or preparations.

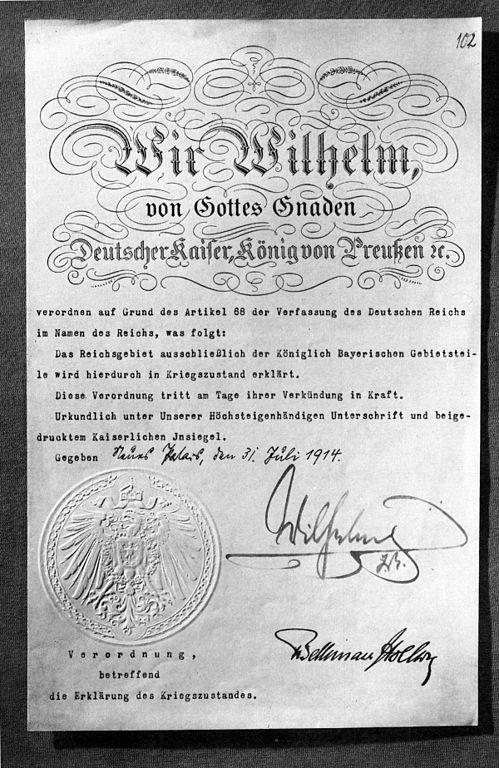

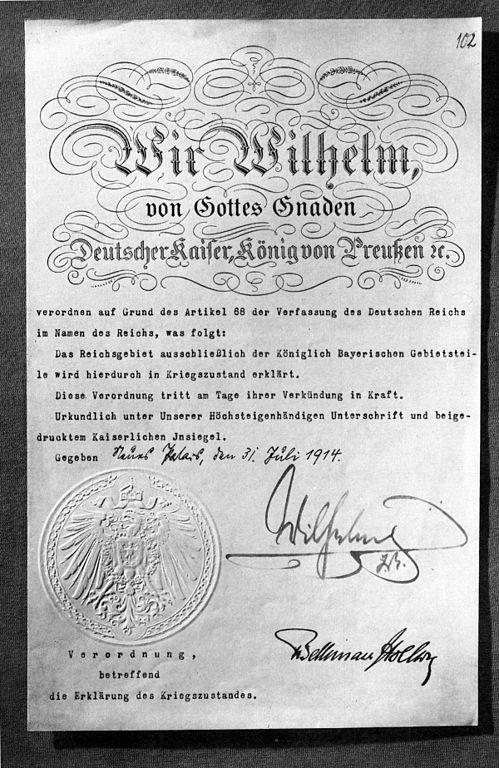

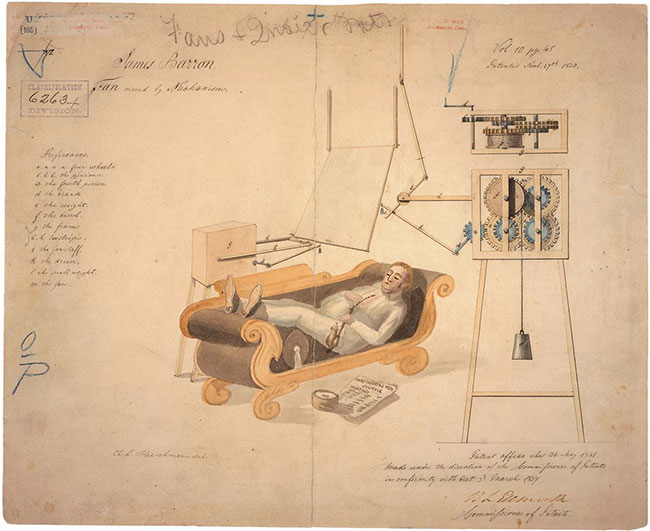

Declaration of war from the German Empire 31 July 1914. Signed by the German Kaiser Wilhelm II. Countersigned by the Reichs-Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Germany’s response was that it could not consider such a proposal until Russia agreed to cease its mobilization. In Berlin at 2 p.m. the the drohenden Kriegszustand (‘imminent peril of war’) was announced. At 3.30 p.m. Bethmann Hollweg instructed the ambassador in St Petersburg to explain that Germany had been compelled to take this step because of Russia’s mobilization. Germany would mobilize unless Russia agreed to suspend ‘every war measure’ aimed at Austria-Hungary and Germany within twelve hours. The time clock was to begin ticking from the moment that the note was presented in St Petersburg.

At 4.15 p.m. Conrad, the chief of the Austrian general staff, telephoned the office of the general staff in Berlin to explain the Austrian position: the emperor had authorized full mobilization only in response to Russia’s actions and only for the purpose of taking precautions against a Russian attack. Austria had no intention of declaring war against Russia. In other words, Russia could mobilize along the Austrian frontier and Austria could match this on the other side. And there the two forces could wait, without going to war.

This prospect terrified Moltke. He replied immediately that Germany would probably mobilize its forces on Sunday and then commence hostilities against Russia and France. Would Austria abandon Germany? Conrad asked if Germany thus intended to launch a war against Russia and France and whether he should rule out the possibility of fighting a war against Serbia without coming to grips with Russia at the same time. Moltke told him about the ultimatums being presented in St Petersburg and Paris, which required answers by 4 p.m. the next day.

At 6.30 p.m. the Kaiser addressed a crowd of thousands gathered at the pleasure gardens in front of the imperial palace. He declared that those who envied Germany had forced him to take measures to defend the Reich. He had been forced to take up the sword but had not ceased his efforts to maintain the peace. If he did not succeed ‘we shall with God’s help wield the sword in such a way that we can sheathe it with honour’.

In London and Paris they continued to hope that a negotiated settlement was possible. Grey suggested that Russia cease its military preparations in exchange for an undertaking from the other Powers that they would seek a way to give complete satisfaction to Austria without endangering the sovereignty or territorial integrity of Serbia. Viviani, the French premier and foreign minister, agreed. He would tell Sazonov that Grey’s formula furnished a useful basis for a discussion among the Powers who sought an honourable solution to the Austro-Serbian conflict and to avert the danger of war. The formula proposed ‘is calculated equally to give satisfaction to Russia and to Austria and to provide for Serbia an acceptable means of escaping from the present difficulty’.

In St. Petersburg that evening the German ambassador, in a private audience with Tsar Nicholas, warned that Russian military measures might already have produced ‘irreparable consequences’. It was entirely possible that the decision to mobilize when the kaiser was attempting to mediate the dispute might be regarded by him as offensive – and by the German people as provocative. ‘I begged him…to check or to revoke these measures’. The Tsar replied that, for technical reasons, it was not now possible to stop the mobilization. For the sake of European peace it was essential, he argued, that Germany influence, or put pressure on, Austria.

In Paris the German ambassador was to ask the French government if it intended to remain neutral in the event of a Russo-German war. An answer was required within 18 hours. In the unlikely case that France agreed to remain neutral, France was to hand over the fortresses of Verdun and Toul as a pledge of its neutrality. The deadline by which France must agree to this demand was set for 4 p.m. the next day

In St. Petersburg, at 11 p.m., the German ambassador presented the 12-hour ultimatum to Sazonov. If Russia did not abandon its mobilization by noon Saturday Germany would mobilize in response. And, as Bethmann Hollweg had already declared, ‘mobilization means war’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Friday, 31 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/30/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Sir Edward Grey,

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg,

Sazonov,

Kaiser Wilhelm,

Joffre,

King George,

History,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

world war I,

diplomatic solution,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

As the day began a diplomatic solution to the crisis appeared to be within sight at last. The German chancellor had insisted that Austria agree to negotiate directly with Russia. While Germany was prepared to fulfill the obligations of its alliance with Austria, it would decline ‘to be drawn wantonly into a world conflagration by Vienna’. Bethmann Hollweg was also promising to support Sir Edward Grey’s proposed conference to mediate the dispute. He told the Austrians that their political prestige and military honour could be satisfied by an occupation of Belgrade. They could enhance their status in the Balkans while strengthening themselves against the Russians through the humiliation of Serbia.

But a third initiative, the direct line of communication between the Kaiser and the Tsar, was running aground. Attempting to reassure Wilhelm, Nicholas explained that the military measures now being undertaken had been decided upon five days ago – and only as a defence against Austria’s preparations. ‘I hope from all my heart that these measures won’t in any way interfere with your part as mediator which I greatly value.’

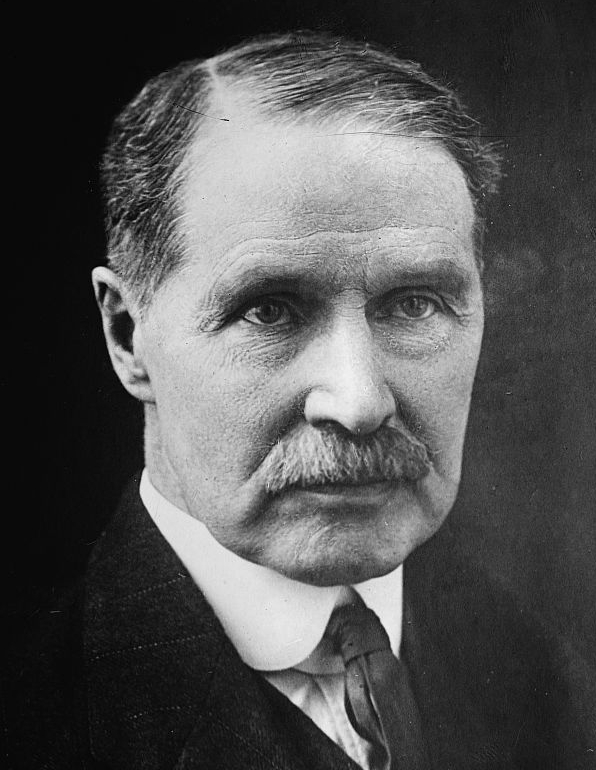

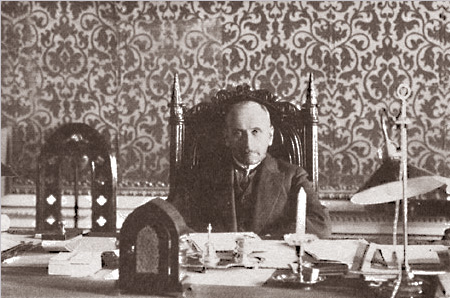

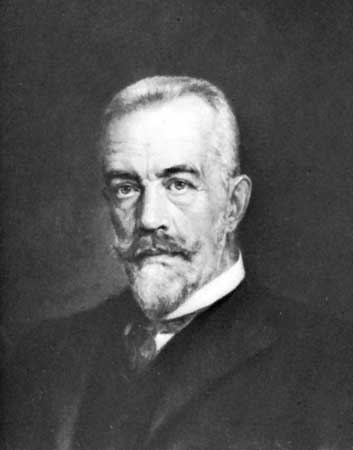

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, Chancellor of the German Empire, 1909-1917. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Wilhelm erupted. He was shocked to discover first thing on Thursday morning that the ‘military measures which have now come into force were decided five days ago’. He would no longer put any pressure on Austria: ‘I cannot agree to any more mediation’; the Tsar, while requesting mediation, ‘has at the same time secretly mobilized behind my back’.

The German ambassador in Vienna presented Bethmann’s directive to a ‘pale and silent’ Berchtold over breakfast. Austria, with guarantees of Serbia’s good behaviour in the future as part of the mediation proposal, could attain its aims ‘without unleashing a world war’. To refuse mediation completely ‘was out of the question’.

Berchtold did as he was told. He explained to the Russians that his apparent rejection of mediation talks was an unfortunate misunderstanding and that he was now prepared to discuss ‘amicably and confidentially’ all questions directly affecting their relations. He warned, however, that he would not yield on any of points in the note to Serbia.

At noon, Russia announced that it was initiating a partial mobilization. But the Austrian ambassador assured Vienna that this was a bluff: Sazonov dreaded war ‘as much as his Imperial Master’ and was attempting ‘to deprive us of the fruits of our Serbian campaign without going to Serbia’s aid if possible’.

In Berlin, the chief of the German general staff began to panic. A few hours after the Russian announcement he pleaded with the Austrians to mobilize fully against Russia and to announce this in a public proclamation. The only way to preserve Austria-Hungary was to endure a European war. ‘Germany is with you unconditionally’. Moltke promised that a German mobilization would immediately follow Austria’s.

In St. Petersburg the war minister and the chief of the general staff tried to persuade Nicholas over the telephone that partial mobilization was a mistake. The Tsar refused to budge. When Sazonov met with the Tsar at Peterhof at 3 p.m. he argued that general mobilization was essential; war was almost inevitable because the Germans were resolved to bring it about. They could easily have made the Austrians see reason if they had desired peace. The Tsar gave way. At 5 p.m. the official decree announcing general mobilization was issued.

In Paris the French cabinet was also deciding to take military steps. They agreed that – for the sake of public opinion – they must take care that ‘the Germans put themselves in the wrong’. They would try to avoid the appearance of mobilizing while consenting to at least some of the requests being made by the army. Covering troops could take up their positions along the German frontier from Luxembourg to the Vosges mountains, but were not to approach closer than 10 kilometres. No train transport was to be used, no reservists were to be called up, no horses or vehicles were to be requisitioned. Joffre, the chief of the general staff, was displeased. These measures would make it difficult to execute the offensive thrust of his war plan. Nevertheless, the orders went out at 4.55 p.m.

In London Grey bluntly rejected Bethmann’s neutrality proposal of the day before: ‘that we should bind ourselves to neutrality on such terms cannot for a moment be entertained’. Germany was asking Britain to stand by while French colonies were taken and France was beaten in exchange for Germany’s promise to refrain from taking French territory in Europe. Such a proposal was unacceptable ‘for France could be so crushed as to lose her position as a Great Power, and become subordinate to German policy’. On the other hand, if the current crisis passed and the peace of Europe preserved, Grey promised to endeavour to promote an arrangement by which Germany could be assured ‘that no hostile or aggressive policy would be pursued against her or her allies by France, Russia, and ourselves, jointly or separately’.

Shortly before midnight a telegram from King George arrived at Potsdam. Responding to an earlier telegram from the Kaiser’s brother, the King assured him that the British government was doing its utmost to persuade Russia and France to suspend further military preparations. This seemed possible ‘if Austria will consent to be satisfied with [the] occupation of Belgrade and neighbouring Servian territory as a hostage for [the] satisfactory settlement of her demands’. He urged the Kaiser to use his great influence at Vienna to induce Austria to accept this proposal and prove that Germany and Britain were working together to prevent a catastrophe.

The Kaiser ordered his brother to drive into Berlin immediately to inform Bethmann Hollweg of the news. Heinrich delivered the message to the chancellor at 1.15 a.m. and had returned to Potsdam by 2.20. Wilhelm planned to answer the King on Friday morning. The Kaiser noted, happily, that the suggestions made by the King were the same as those he had proposed to Vienna that evening.

Surely a peaceful resolution was at hand?

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/29/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

The Great War,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Sir Edward Grey,

Kaiser Wilhelm,

Bethmann Hollweg,

Leopold Berchtold,

Sergey Sazonov,

Tsar Nicholas II,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Before the sun rose on Wednesday morning a new hope for a negotiated settlement of the crisis was initiated. The Kaiser, acting on the advice of his chancellor, wrote directly to the Tsar. He hoped that Nicholas would agree with him that they shared a common interest in punishing all of those ‘morally responsible’ for the dastardly murder of the Archduke, and he promised to exert his influence to induce Austria to deal directly with Russia in order to arrive at an understanding.

At 1 a.m. Nicholas appealed to Wilhelm for his assistance: ‘An ignoble war has been declared on a weak country.’ The indignation that this had caused in Russia was enormous and he anticipated that he would soon be overwhelmed by the pressure being brought to bear upon him, forcing him to take ‘extreme measures’ that would lead to war. To avoid this terrible calamity, he begged Wilhelm, in the name of their old friendship, ‘to do what you can to stop your allies from going too far.’

The question of the day on Wednesday was whether Austria-Hungary and Russia might undertake direct discussions to settle the crisis before further military steps turned a local Austro-Serbian war into a general European one.

The German general staff summarized its view of the situation: the crime of Sarajevo had led Austria to resort to extreme measures ‘in order to burn with a glowing iron a cancer that has constantly threatened to poison the body of Europe’. The quarrel would have been limited to Austria and Serbia had not Russia begun making military preparations. Now, if the Austrians advanced into Serbia, they would face not only the Serbian army but the vastly superior strength of Russia. Thus, they could not contemplate fighting Serbia without securing themselves against an attack by Russia. This would force them to mobilize the other half of their army – at which point a collision between Austria and Russia would become inevitable. This would force Germany to mobilize, which would lead Russia and France to do the same – ‘and the mutual butchery of the civilized nations of Europe would begin’.

In other words, unless a negotiated settlement could be reached quickly, war seemed inevitable.

Berchtold pleaded with Berlin that only ‘plain speech’ would restrain the Russians, i.e. only the threat of a German attack would stop them from taking military action against Austria. And there were signs that Russia was wary of war. The Austrian ambassador reported that Sazonov was desperate to avoid a conflict and was ‘clinging to straws in the hope of escaping from the present situation’. Sazonov promised that if they were to negotiate on the basis of Sir Edward Grey’s proposal, Austria’s legitimate demands would be recognized and fully satisfied.

At the same time, Sazonov was pleading for British support: the only way to prevent war now was for Britain to warn the Triple Alliance that it would join its entente partners if war were to break out.

But Grey refused to make any promises. When he met with the French ambassador later that afternoon, he warned him not to assume that Britain would again stand by France as it had in 1905. Then it had appeared that Germany was attempting to crush France; now, ‘the dispute between Austria and Serbia was not one in which we felt called to take a hand’. Earlier that day the British cabinet had decided not to decide; Grey was to inform both sides that Britain was unable to make any promises.

At 4 p.m. the German general staff received intelligence that Belgium was calling up reservists, raising the numbers of the Belgian army from 50,000 to 100,000, equipping its fortifications and reinforcing defences along the frontier. Forty minutes later a meeting at the Neue Palais in Potsdam, the Kaiser and his advisers decided to compose an ultimatum to present to Belgium: either agree to adopt an attitude of ‘benevolent neutrality’ towards Germany in a European war or face dire consequences.

Simultaneously, Bethmann Hollweg decided to launch a bold new initiative. He proposed to the British ambassador that Britain agree to remain neutral in the event of war in exchange for a German promise not to seize any French territory in Europe when it ended. He understood that Britain would not allow France to be crushed, but this was not Germany’s aim. When asked whether his proposal applied to French colonies as well, the chancellor replied that he was unable to give a similar undertaking concerning them. Belgium’s integrity would be respected when the war ended –as long as it had not sided against Germany.

Yet another German initiative was taken in St Petersburg. At 7 p.m. the German ambassador transmitted a warning from the chancellor that if Russia continued with its military preparations Germany would be compelled to mobilize, in which case it would take the offensive. Sazonov replied that this removed any doubts he may have had concerning the real cause of Austria’s intransigence.

The Russians found this confusing, as they had just received another telegram from the Kaiser containing a plea that he should not permit Russian military measures to jeopardize German efforts to promote a direct understanding between Russia and Austria. It was agreed that the Tsar should wire Berlin immediately to ask for an explanation of the apparent discrepancy. At 8.20 p.m. the wire asking for clarification was sent. Trusting in his cousin’s ‘wisdom and friendship’, Tsar Nicholas suggested that the ‘Austro-Serbian problem’ be handed over to the Hague conference.

A message announcing a general mobilization in Russia had been drafted and ready to be sent out by 9 p.m. Then, just minutes before it was to be sent out, a personal messenger from the Tsar arrived, instructing that it the general mobilization be cancelled and a partial one re-instituted. The Tsar wanted to hear how the Kaiser would respond to his latest telegram before proceeding. ‘Everything possible must be done to save the peace. I will not become responsible for a monstrous slaughter’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Wednesday, 29 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/28/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

declaration of war,

Kaiser Wilhelm,

austro,

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

world war I,

British,

Diplomacy,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

belgrade,

first world war,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Kaiser Wilhelm received a copy of the Serbian reply to the Austrian demands in the morning. Reading it over, he concluded that the Habsburg monarchy had achieved its aims and that the few points Serbia objected to could be settled by negotiation. Their submission represented a humiliating capitulation, and with it ‘every cause for war’ collapsed. A diplomatic solution to the crisis was now clearly within sight. Austria-Hungary would emerge triumphant: the Serbian reply represented ‘a great moral success for Vienna’.

In order to assure Austria’s success, to turn the ‘beautiful promises’ of the Serbs into facts, the Kaiser proposed that Belgrade should be taken and held hostage by Austria. ‘The Serbs,’ he pointed out, ‘are Orientals, and therefore liars, fakers and masters of evasion.’ An occupation of Belgrade would guarantee that the Serbs would carry out their promises while satisfying satisfying the honour of the Austro-Hungarian army. On this basis the Kaiser was willing to ‘mediate’ with Austria in order to preserve European peace.

In Vienna that morning the German ambassador was instructed to explain that Germany could not continue to reject every proposal for mediation. To do so was to risk being seen as the instigator of the war and being held responsible by the whole world for the conflagration that would follow.

Berchtold began to worry that German support was about to evaporate. He responded by getting the emperor to agree to issue a declaration of war on Serbia just before noon. For the first time in history war was declared by the sending of a telegram.

The bombardment of Belgrade by Austro-Hungarian monitor. By Horace Davis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The German chancellor undertook a new initiative to place the responsibility for a European war on Russia: he encouraged Kaiser to write directly to the Tsar, to appeal to his monarchical sensibilities. Such a telegram would ‘throw the clearest light on Russia’s responsibility’. At the same time he rejected Sir Edward Grey’s proposal for a conference in London in favour of ‘mediation efforts’ at St Petersburg, and trusted that his ambassador in London could get Grey ‘to see our point of view’.

At the Foreign Office in London they were skeptical. Officials concluded that the Austrians were determined to find the Serbian reply unsatisfactory, that if Austria demanded absolute compliance with its ultimatum ‘it can only mean that she wants a war’. What Austria was demanding amounted to a protectorate. Grey denied the German complaint that he was proposing an ‘arbitration’ – what he was suggesting was a ‘private and informal discussion’ that might lead to suggestion for settlement. But he agreed to suspend his proposal as long as there was a chance that the ‘bilateral’ Austro-Russian talks might succeed.

The news that Austria-Hungary had declared war on Serbia reached Sazonov in St Petersburg late that afternoon. He immediately arranged to meet with the Tsar at the Peterhof. After their meeting the foreign minister instructed the Russian chief of the general staff to draft two ukazes – one for partial mobilization of the four military districts of Odessa, Kiev, Moscow and Kazan, another for general mobilization. But the Tsar, who remained steadfast in his determination to do nothing that might antagonize Germany, would go no further than authorize a partial mobilization aimed at Austria-Hungary. He did so in spite of the warnings from his military advisers who told him that such a mobilization was impossible: a partial mobilization would result in chaos, make it impossible to prosecute a successful war against Austria-Hungary and render Russia vulnerable in a war with Germany.

A partial mobilization would, however, serve the requirements of Russian diplomacy. Sazonov attempted to placate the Germans by assuring them that the decision to mobilize in only the four districts indicated that Russia had no intention of attacking them. Keeping the door open for negotiations, he decided not to recall the Russian ambassador from Vienna – in spite of Austria’s declaration of war on Serbia. Perhaps there was still time for the bilateral talks in St Petersburg to save the situation.

That night Belgrade was bombarded by Austro-Hungarian artillery: two shells exploded in a school, one at the Grand Hotel, others at cafés and banks. Offices, hotels, and banks had been closed. The city had been left defenceless.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

By the time the diplomats, politicians, and officials arrived at their offices in the morning more than 36 hours had elapsed since the Austrian deadline to Serbia had expired. And yet nothing much had happened as a consequence: the Austrian legation had packed up and left Belgrade; Austria had severed diplomatic relations with Serbia and announced a partial mobilization; but there had been no declaration of war, no shots fired in anger or in error, no wider mobilization of European armies. What action there was occurred behind the scenes, at the Foreign Office, the Ballhausplatz, the Wilhelmstrasse, the Consulta, the Quai d’Orsay, and at the Chorister’s Bridge.

Some tentative, precautionary, steps were taken. In Russia, all lights along the coast of the Black Sea were ordered to be extinguished; the port of Sevastopol was closed to all but Russian warships; flights were banned over the military districts of St Petersburg, Vilna, Warsaw, Kiev, and Odessa. In France, over 100,000 troops stationed in Morocco and Algeria were ordered to metropolitan France; the French president and premier were asked to sail for home immediately. In Britain the cabinet agreed to keep the First and Second fleets together following manoeuvres; Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, notified his naval commanders that war between the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente was ‘by no means impossible’. In Germany all troops were confined to barracks. On the Danube, Hungarian authorities seized two Serbian vessels.

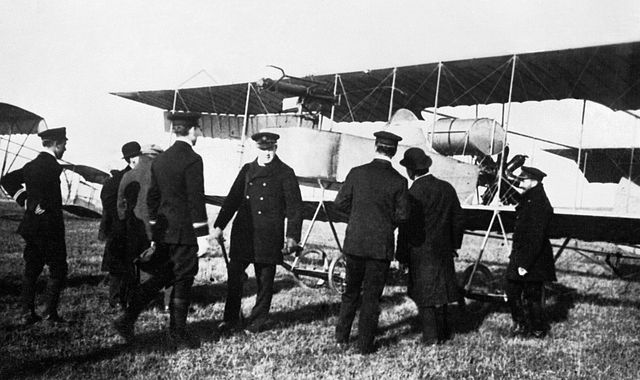

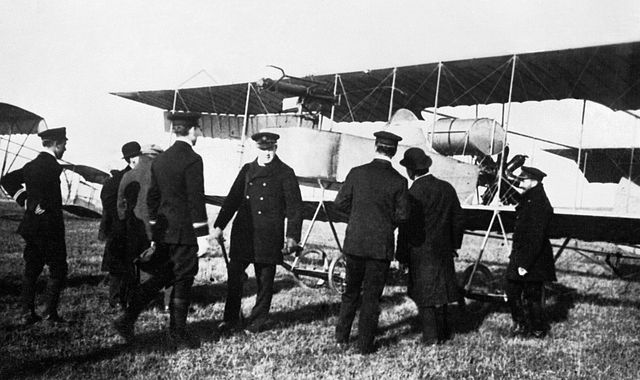

Winston Churchill with the Naval Wing of the Royal Flying Corps, 1914. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Throughout the day the Serbian reply to the Austrian ultimatum was communicated throughout Europe. Austria appeared to have won great diplomatic victory. Sir Edward Grey thought the Serbs had gone farther to placate the Austrians than he had believed possible: if the Austrians refused to accept the Serbian reply as the foundation for peaceful negotiations it would be ‘absolutely clear’ that they were only seeking an excuse to crush Serbia. If so, Russia was bound to regard it as a direct challenge and the result ‘would be the most frightful war that Europe had ever seen’.

The German chancellor concluded that Serbia had complicated things by accepting almost all of the demands and that Austria was close to accomplishing everything that it wanted. The Kaiser who arrived in Kiel that morning, presided over a meeting in Potsdam at 3 p.m. where he, the chancellor, the chief of the general staff, and several more generals reviewed the situation. No dramatic decisions were taken. General Hans von Plessen, the adjutant general, recorded that they still hoped to localize the war, and that Britain seemed likely to remain neutral: ‘I have the impression that it will all blow over’.

The question of the day, then, was whether Austria would be satisfied with a resounding diplomatic victory. Russia seemed prepared to offer them one. In St Petersburg on Monday Sazonov promised to go ‘to the limit’ in accommodating them if it brought the crisis to a peaceful conclusion. He promised the German ambassador that he would they ‘build a golden bridge’ for the Austrians, that he had ‘no heart’ for the Balkan Slavs, and that he saw no problem with seven of the ten Austrian demands.

In Vienna however, Berchtold dismissed Serbia’s promises as totally worthless. Austria, he promised, would declare war the next day, or by Wednesday at the latest – in spite of the chief of the general staff’s insistence that war operations against Serbia could not begin for two weeks.

Grey was distressed to hear that Austria would treat the Serb reply as if it were a ‘decided refusal’ to comply with Austria’s wishes. The ultimatum was ‘really the greatest humiliation to which an independent State has ever been subjected’ and was surely enough to serve as foundation of a settlement.

By the end of the day on Monday, uncertainty was still widespread. Two separate proposals for reaching a settlement were now on the table: Grey’s renewed suggestion for à quatre discussions in London, and Sazonov’s new suggestion for bilateral discussions with Austria in St Petersburg. Germany had indicated that it was encouraging Austria to consider both suggestions. The German ambassador told Berlin that if Grey’s suggestion succeeded in settling the crisis with Germany’s co-operation, ‘I will guarantee that our relations with Great Britain will remain, for an incalculable time to come, of the same intimate and confidential character that has distinguished them for the last year and a half’. On the other hand, if Germany stood behind Austria and subordinated its good relations with Britain to the special interests of its ally, ‘it would never again be possible to restore those ties which have of late bound us together’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

war,

military history,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

*Featured,

kaiser,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

When day dawned on Sunday, 26 July, the sky did not fall. Shells did not rain down on Belgrade. There was no Austrian declaration of war. The morning remained peaceful, if not calm. Most Europeans attended their churches and prepared to enjoy their day of rest. Few said prayers for peace; few believed divine intervention was necessary. Europe had weathered many storms over the last decade. Only pessimists doubted that this one could be weathered as well.

In Austria-Hungary the right of assembly, the secrecy of the mail, of telegrams and telephone conversations, and the freedom of the press were all suspended. Pro-war demonstrations were not only permitted but encouraged: demonstrators filled the Ringstrasse, marched on the Ballhausplatz, gathered around statues of national heroes and sang patriotic songs. That evening the Bürgermeister of Vienna told a cheering crowd that the fate of Europe for centuries to come was about to be decided, praising them as worthy descendants of the men who had fought Napoleon. The Catholic People’s Party newspaper, Alkotmány, declared that ‘History has put the master’s cane in the Monarchy’s hands. We must teach Serbia, we must make justice, we must punish her for her crimes.’

Kaiser Wilhelm

Just how urgent was the situation? In London, Sir Edward Grey had left town on Saturday afternoon to go to his cottage for a day of fly-fishing on Sunday. The Russian ambassadors to Germany, Austria and Paris had yet to return to their posts. The British ambassadors to Germany and Paris were still on vacation. Kaiser Wilhelm was on his annual yachting cruise of the Baltic. Emperor Franz Joseph was at his hunting lodge at Bad Ischl. The French premier and president were visiting Stockholm. The Italian foreign minister was still taking his cure at Fiuggi. The chiefs of the German and Austrian general staffs remained on leave; the chief of the Serbian general staff was relaxing at an Austrian spa.

Could calm be maintained? Contradictory evidence seemed to be coming out of St Petersburg. It seemed that some military steps were being initiated – but what these were to be remained uncertain. Sazonov, the Russian foreign minister, met with both the German and Austrian ambassadors on Sunday – and both noted a significant change in his demeanour. He was now ‘much quieter and more conciliatory’. He emphatically insisted that Russia did not desire war and promised to exhaust every means to avoid it. War could be avoided if Austria’s demands stopped short of violating Serbian sovereignty. The German ambassador suggested that Russia and Austria discuss directly a softening of the demands. Sazonov, who agreed immediately to suggest this, was ‘now looking for a way out’. The Germans were assured that only preparatory measures had been undertaken thus far – ‘not a horse and not a reserve had been called to service’.

By late Sunday afternoon, the situation seemed precarious but not hopeless. The German chancellor worried that any preparatory measures adopted by Russia that appeared to be aimed at Germany would force the adoption of counter-measures. This would mean the mobilization of the German army – and mobilization ‘would mean war’. But he continued to hope that the crisis could be ‘localized’ and indicated that he would encourage Vienna to accept Grey’s proposed mediation and/or direct negotiations between Austria and Russia.

By Sunday evening more than 24 hours had passed since the Austrian legation had departed from Belgrade and Austria had severed diplomatic relations with Serbia. Many had assumed that war would follow immediately, but there had been no invasion of Serbia or even a declaration of war. The Austrians, in spite of their apparent firmness in refusing any alteration of the terms or any extension of the deadline, appeared not to know what step to take next, or when additional steps should be taken. When asked, the Austrian chief of staff suggested that any declaration of war ought to be postponed until 12 August. Was Europe really going to hold its breath for two more weeks?

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Kaiser Wilhelm, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/25/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

the july crisis,

WWI centenary,

ischl,

kaiservilla,

tornadoo,

kaiserville,

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

world war I,

austria,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

serbia,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Would there be war by the end of the day? It certainly seemed possible: the Serbs had only until 6 p.m. to accept the Austrian demands. Berchtold had instructed the Austrian representative in Belgrade that nothing less than full acceptance of all ten points contained in the ultimatum would be regarded as satisfactory. And no one expected the Serbs to comply with the demands in their entirety – least of all the Austrians.

When the Serbian cabinet met that morning they had received advice from Russia, France, and Britain urging them to be as accommodating as possible. No one indicated that any military assistance might be forthcoming. They began drafting a ‘most conciliatory’ reply to Austria while preparing for war: the royal family prepared to leave Belgrade; the military garrison left the city for a fortified town 60 miles south; the order for general mobilization was signed and drums were beaten outside of cafés, calling up conscripts.

Kaiservilla in Bad Ischl, Austria: the summer residence of Emperor Franz Joseph I. Kaiserville, Bad Ischl, Austria. By Blue tornadoo CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

How would Russia respond? That morning the tsar presided over a meeting of the Russian Grand Council where it was agreed to mobilize the thirteen army corps designated to act against Austria. By afternoon ‘the period preparatory to war’ was initiated and preparations for mobilization began in the military districts of Kiev, Odessa, Moscow, and Kazan.

Simultaneously, Sazonov tried to enlist German support in persuading Austria to extend the deadline beyond 6 p.m., arguing that it was a ‘European matter’ not limited to Austria and Serbia. The Germans refused, arguing that to summon Austria to a European ‘tribunal’ would be humiliating and mean the end of Austria as a Great Power. Sazonov insisted that the Austrians were aiming to establish hegemony in the Balkans: after they devoured Serbia and Bulgaria Russia would face them ‘on the Black Sea’. He tried to persuade Sir Edward Grey that if Britain were to join Russia and France, Germany would then pressure Austria into moderation.

How would Britain respond? Sir Edward Grey gave no indication that Britain would stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the Russians in a conflict over Serbia. His only concern seemed to be to contain the crisis, to keep it a dispute between Austria and Serbia. ‘I do not consider that public opinion here would or ought to sanction our going to war over a Servian quarrel’. But if a war between Austria and Serbia were to occur ‘other issues’ might draw Britain in. In the meantime, there was still an opportunity to avert war if the four disinterested powers ‘held the hand’ of their partners while mediating the dispute. But the report he received from St Petersburg was not encouraging: the British ambassador warned that Russia and France seemed determined to make ‘a strong stand’ even if Britain declined to join them.

When the Austrian minister received the Serb reply at 5:58 on Saturday afternoon, he could see instantly that their submission was not complete. He announced that Austria was breaking off diplomatic relations with Serbia and immediately ordered the staff of the delegation to leave for the railway station. By 6:30 the Austrians were on a train bound for the border.

That evening, in the Kaiservilla at Bad Ischl, Franz Joseph signed the orders for mobilization of thirteen army corps. When the news reached Vienna the people greeted it with the ‘wildest enthusiasm’. Huge crowds began to form, gathering at the Ringstrasse and bursting into patriotic songs. The crowds marched around the city shouting ‘Down with Serbia! Down with Russia’. In front of the German embassy they sang ‘Wacht am Rhein’; police had to protect the Russian embassy against the demonstrators. Surely, it would not be long before the guns began firing.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Saturday, 25 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/24/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

austria,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

hungary,

Serbia,

*Featured,

serbian,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

july crisis,

Berchtold,

Edward Grey,

Austria-Hungary,

Austrian ultimatum,

Sazonov,

sergey,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

By mid-day Friday heads of state, heads of government, foreign ministers, and ambassadors learned the terms of the Austrian ultimatum. A preamble to the demands asserted that a ‘subversive movement’ to ‘disjoin’ parts of Austria-Hungary had grown ‘under the eyes’ of the Serbian government. This had led to terrorism, murder, and attempted murder. Austria’s investigation of the assassination of the archduke revealed that Serbian military officers and government officials were implicated in the crime.

A list of ten demands followed, the most important of which were: Serbia was to suppress all forms of propaganda aimed at Austria-Hungary; the Narodna odbrana was to be dissolved, along with all other subversive societies; officers and officials who had participated in propaganda were to be dismissed; Austrian officials were to participate in suppressing the subversive movements in Serbia and in a judicial inquiry into the assassination.

When Sazonov saw the terms he concluded that Austria wanted war: ‘You are setting fire to Europe!’ If Serbia were to comply with the demands it would mean the end of its sovereignty. ‘What you want is war, and you have burnt your bridges behind you’. He advised the tsar that Serbia could not possibly comply, that Austria knew this and would not have presented the ultimatum without the promise of Germany’s support. He told the British and French ambassadors that war was imminent unless they acted together.

But would they? With the French president and premier now at sea in the Baltic, and with wireless telegraphy problematic, foreign policy was in the hands of Bienvenu-Martin, the inexperienced minister of justice. He believed that Austria was within its rights to demand the punishment of those implicated in the crime and he shared Germany’s wish to localize the dispute. Serbia could not be expected to agree to demands that impinged upon its sovereignty, but perhaps it could agree to punish those involved in the assassination and to suppress propaganda aimed at Austria-Hungary.