new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: From the Man Who Brought You Mrs. Doubtfire (Also a Childrens Book), Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 58

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: From the Man Who Brought You Mrs. Doubtfire (Also a Childrens Book) in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

I’ve spent a lot of time in this organic architecture series talking about plot plot plot plot. (If you’ve missed those post please check out: arch plot, alternative plots, and plot genres). But it’s time to switch gears and think about organization, rhythm, and energy.

I’ve spent a lot of time in this organic architecture series talking about plot plot plot plot. (If you’ve missed those post please check out: arch plot, alternative plots, and plot genres). But it’s time to switch gears and think about organization, rhythm, and energy.

That’s right let’s talk structure! (Which, if you don’t remember I’m obsessed with. Yes, I said obsessed).

Traditionally, we’re used to thinking about structure as a mountain or triangle with an escalating tension. But I want to break out of the triangle/mountain box and think about structure in a new way. The following ideas can be applied to a mountain structure (if you want), or they can provide a whole new guideline for rhythm and tension!

Alternative structures all be discussing include:

- Non-linear structure

- Episodic structure with an arc

- Wheel structure

- Meandering structure

- Branching structure

- Spiral structure

- Multiple point-of-view structure

- Parallel structure

- Cumulative structure

Let’s dig right in!

NON-LINEAR STRUCTURE

(Also known as: Backwards Structure, Scrambled Sequence Structure)

Non-linear structure tells events out of linear order for dramatic impact. The juxtaposition of out-of-order scenes and sequences can help the reader to create plot connections, expand character depth, or elaborate on theme. Backwards structures draw attention to causal connections, like forward-moving linear structures, but become causal mysteries, where the narrative fuel is the search for the first cause of known effects (Berg). Scrambled-sequence structures don’t “do away with the cause-and-effect chain, [they] merely suspend it for a time, eventually to be ordered by the competent spectator” (Berg). Additionally, a story with a flashback can be considered part of a non-linear structure. However, some define flashbacks as a character thinking back on an event, and thus exist within a traditional linear-story timeline.

- Film Examples: Memento, Pulp Fiction, The Limey, Out of Sight, Reservoir Dogs.

- Book Examples: Betrayal (Pinter), Habibi (Thompson), The Time Traveler’s Wife (Niffenegger), Beneath a Meth Moon (Woodson).

EPISODIC STRUCTURE WITH AN ARC

(Also known as: Television Structure, Book Series Structure)

“Episodic structure is a series of chapters or stories linked together by the same character place or theme, but also held apart by their own goals, plots, or purpose” (Schmidt). A larger multiple book or episode character-arc or plot-goal often ties together a series, as done in television and comic books.

- Film Examples: Friday Night Lights, Mad Men, Friends, Dr. Who, Game of Thrones, Battlestar Galactica, Vampire Diaries, Gossip Girl, etc.

- Singular Book Examples: The Graveyard Book (Gaiman), The New York Singles Mormon Halloween Dance (Baker), The Strange Case of Origami Yoda (Angleberger).

- Series Book Examples: The Adventures of Tintin (Herge), Sin City (Miller), Knuffle Bunny (Willems), Hunger Games (Collins).

WHEEL STRUCTURE

(Also known as: The Short Story Cycle, Hub and Spoke Structure)

In wheel structure, scenes, stories, vignettes, and poems, all revolve around a thematic center where the “hub [is] a compelling emotional event, and the narration refer[s] to this event like the spokes.” (Campbell). Additionally, “the rim of the wheel represents recurrent elements in a cycle … [and] as these elements repeat themselves, turn in on themselves, and recur, the whole wheel moves forward” (Kalmar). Many novels in verse or vignettes use this structure.

- Film Examples: Waking Life, Loss of Sexual Innocence, Chungking Express, The Tree of Life.

- Book Examples: The chapter structure of Keesha’s House (Frost), Einstein’s Dreams (Lightman), The House on Mango Street (Cisneros), Tales from Outer Suburbia (Tan).

MEANDERING STRUCTURE

(Also known as: River Structure, Winding Path Structure)

Meandering structure is a “story that follows a winding path without apparent direction” (Truby). The hero may or may not have a desire. If the hero has a desire it is not intense, and “he covers a great deal of territory in a haphazard way; and he encounters a number of characters from different levels of society” (Truby).

- Film Examples: Forrest Gump.

- Book Examples: Alice in Wonderland (Carroll), Huck Finn (Twain), Don Quixote (Cervantes).

In my next post we’ll take a look at:

- Branching structure

- Spiral structure

- Multiple point-of-view structure

- Parallel structure

- Cumulative structure

Works Cited:

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Tax-onomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

I’ve spent a lot of time in this organic architecture series talking about plot plot plot plot. (If you’ve missed those post please check out: arch plot, alternative plots, and plot genres). But it’s time to switch gears and think about organization, rhythm, and energy.

I’ve spent a lot of time in this organic architecture series talking about plot plot plot plot. (If you’ve missed those post please check out: arch plot, alternative plots, and plot genres). But it’s time to switch gears and think about organization, rhythm, and energy.

That’s right let’s talk structure! (Which, if you don’t remember I’m obsessed with. Yes, I said obsessed).

Traditionally, we’re used to thinking about structure as a mountain or triangle with an escalating tension. But I want to break out of the triangle/mountain box and think about structure in a new way. The following ideas can be applied to a mountain structure (if you want), or they can provide a whole new guideline for rhythm and tension!

Alternative structures all be discussing include:

- Non-linear structure

- Episodic structure with an arc

- Wheel structure

- Meandering structure

- Branching structure

- Spiral structure

- Multiple point-of-view structure

- Parallel structure

- Cumulative structure

Let’s dig right in!

NON-LINEAR STRUCTURE

(Also known as: Backwards Structure, Scrambled Sequence Structure)

Non-linear structure tells events out of linear order for dramatic impact. The juxtaposition of out-of-order scenes and sequences can help the reader to create plot connections, expand character depth, or elaborate on theme. Backwards structures draw attention to causal connections, like forward-moving linear structures, but become causal mysteries, where the narrative fuel is the search for the first cause of known effects (Berg). Scrambled-sequence structures don’t “do away with the cause-and-effect chain, [they] merely suspend it for a time, eventually to be ordered by the competent spectator” (Berg). Additionally, a story with a flashback can be considered part of a non-linear structure. However, some define flashbacks as a character thinking back on an event, and thus exist within a traditional linear-story timeline.

- Film Examples: Memento, Pulp Fiction, The Limey, Out of Sight, Reservoir Dogs.

- Book Examples: Betrayal (Pinter), Habibi (Thompson), The Time Traveler’s Wife (Niffenegger), Beneath a Meth Moon (Woodson).

EPISODIC STRUCTURE WITH AN ARC

(Also known as: Television Structure, Book Series Structure)

“Episodic structure is a series of chapters or stories linked together by the same character place or theme, but also held apart by their own goals, plots, or purpose” (Schmidt). A larger multiple book or episode character-arc or plot-goal often ties together a series, as done in television and comic books.

- Film Examples: Friday Night Lights, Mad Men, Friends, Dr. Who, Game of Thrones, Battlestar Galactica, Vampire Diaries, Gossip Girl, etc.

- Singular Book Examples: The Graveyard Book (Gaiman), The New York Singles Mormon Halloween Dance (Baker), The Strange Case of Origami Yoda (Angleberger).

- Series Book Examples: The Adventures of Tintin (Herge), Sin City (Miller), Knuffle Bunny (Willems), Hunger Games (Collins).

WHEEL STRUCTURE

(Also known as: The Short Story Cycle, Hub and Spoke Structure)

In wheel structure, scenes, stories, vignettes, and poems, all revolve around a thematic center where the “hub [is] a compelling emotional event, and the narration refer[s] to this event like the spokes.” (Campbell). Additionally, “the rim of the wheel represents recurrent elements in a cycle … [and] as these elements repeat themselves, turn in on themselves, and recur, the whole wheel moves forward” (Kalmar). Many novels in verse or vignettes use this structure.

- Film Examples: Waking Life, Loss of Sexual Innocence, Chungking Express, The Tree of Life.

- Book Examples: The chapter structure of Keesha’s House (Frost), Einstein’s Dreams (Lightman), The House on Mango Street (Cisneros), Tales from Outer Suburbia (Tan).

MEANDERING STRUCTURE

(Also known as: River Structure, Winding Path Structure)

Meandering structure is a “story that follows a winding path without apparent direction” (Truby). The hero may or may not have a desire. If the hero has a desire it is not intense, and “he covers a great deal of territory in a haphazard way; and he encounters a number of characters from different levels of society” (Truby).

- Film Examples: Forrest Gump.

- Book Examples: Alice in Wonderland (Carroll), Huck Finn (Twain), Don Quixote (Cervantes).

In my next post we’ll take a look at:

- Branching structure

- Spiral structure

- Multiple point-of-view structure

- Parallel structure

- Cumulative structure

Works Cited:

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Tax-onomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

I want to step back for a second and clarify my own personal definitions of plot versus structure. As mentioned in my previous post on plot definitions there are many views of what plot it! Additionally, I fear that as I walked us through arch plot and classic design last week, I may have reinforced the misconceptions that plot and structure are same thing.

I want to step back for a second and clarify my own personal definitions of plot versus structure. As mentioned in my previous post on plot definitions there are many views of what plot it! Additionally, I fear that as I walked us through arch plot and classic design last week, I may have reinforced the misconceptions that plot and structure are same thing.

Plot and structure are not the same thing!

I did a previous series on plot (To Plot or Not to Plot) where I explored the differences between narrative, story, plot, and structure. I’ve since re-evaluated some of the things I said in those posts and the following are my current definitions:

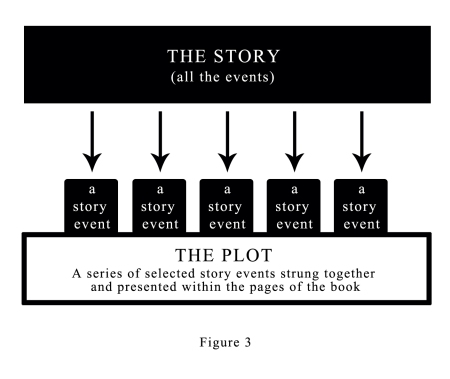

PLOT: Plot is often defined as a “sequence of actions” (Fletcher) or “the actions of the characters” (Bechard). However, plot is also the connective tissue that links events or actions with meaning. It’s not just what happens, but the causal connections of why it happens. Janet Burroway defines plot as a “series of events deliberately arranged so as to reveal their dramatic, thematic, and emotional significance … Plot’s concern is ‘what, how, and why,’ with scenes ordered to highlight cause-and-effect.”

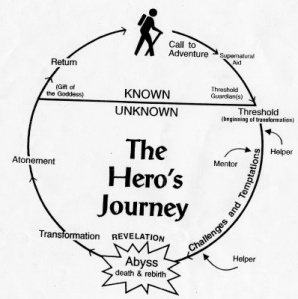

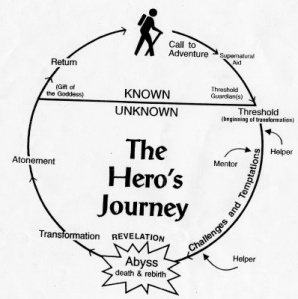

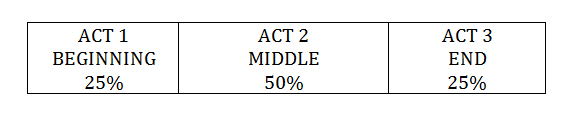

In simple terms, plot is a series of actions with a cause and effect relationship. In my explanation of arch plot, the hero’s journey is the plot.

Whereas…

STRUCTURE: Structure is the triangle or mountain shape in the diagram I used. Structure has two parts. The first is arrangement. For example, you tell scene one, then scene two, then scene three. Or you tell scene 3, then scene 1, then scene 27, etc. This is about order and organization. The second part is about patterns, rhythm, and energy. It’s about the movement and feeling your particular arrangement creates. The triangle (often called the Aristotelian story shape) is a visual metaphor for the escalating energy that is meant to come as a result of a classic design arrangement.

With structure we are looking at the arrangement and rhythm of the whole. Author, Susan Fletcher defines structure as “the organization, or overall design, or form of a particular literary work … [It is the] larger rhythm of the story.” Additionally, Chea says that “in examining story structure, we look for patterns, for the shape that the story as a whole possesses. Plot directs us to the story in motion, structure to the story at rest.”

In the coming posts, I’m going to list alternative plots and alternative structures. I wanted to clarify the difference between these terms so you would better understand how I’ve organized these lists. One is by the nature of the action (plot) while the other is about the organization and rhythm of the action (structure).

Works Cited:

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

I want to step back for a second and clarify my own personal definitions of plot versus structure. As mentioned in my previous post on plot definitions there are many views of what plot it! Additionally, I fear that as I walked us through arch plot and classic design last week, I may have reinforced the misconceptions that plot and structure are same thing.

I want to step back for a second and clarify my own personal definitions of plot versus structure. As mentioned in my previous post on plot definitions there are many views of what plot it! Additionally, I fear that as I walked us through arch plot and classic design last week, I may have reinforced the misconceptions that plot and structure are same thing.

Plot and structure are not the same thing!

I did a previous series on plot (To Plot or Not to Plot) where I explored the differences between narrative, story, plot, and structure. I’ve since re-evaluated some of the things I said in those posts and the following are my current definitions:

PLOT: Plot is often defined as a “sequence of actions” (Fletcher) or “the actions of the characters” (Bechard). However, plot is also the connective tissue that links events or actions with meaning. It’s not just what happens, but the causal connections of why it happens. Janet Burroway defines plot as a “series of events deliberately arranged so as to reveal their dramatic, thematic, and emotional significance … Plot’s concern is ‘what, how, and why,’ with scenes ordered to highlight cause-and-effect.”

In simple terms, plot is a series of actions with a cause and effect relationship. In my explanation of arch plot, the hero’s journey is the plot.

Whereas…

STRUCTURE: Structure is the triangle or mountain shape in the diagram I used. Structure has two parts. The first is arrangement. For example, you tell scene one, then scene two, then scene three. Or you tell scene 3, then scene 1, then scene 27, etc. This is about order and organization. The second part is about patterns, rhythm, and energy. It’s about the movement and feeling your particular arrangement creates. The triangle (often called the Aristotelian story shape) is a visual metaphor for the escalating energy that is meant to come as a result of a classic design arrangement.

With structure we are looking at the arrangement and rhythm of the whole. Author, Susan Fletcher defines structure as “the organization, or overall design, or form of a particular literary work … [It is the] larger rhythm of the story.” Additionally, Chea says that “in examining story structure, we look for patterns, for the shape that the story as a whole possesses. Plot directs us to the story in motion, structure to the story at rest.”

In the coming posts, I’m going to list alternative plots and alternative structures. I wanted to clarify the difference between these terms so you would better understand how I’ve organized these lists. One is by the nature of the action (plot) while the other is about the organization and rhythm of the action (structure).

Works Cited:

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 6/10/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Classic Design,

Classic Plot Design,

Plot,

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Energic Plot,

Add a tag

Last week I started off my Organic Architecture series by outlining the eleven major story-beats of classical design. Before I jump into alternative structures and plots I want to make sure we understand arch plot as more than just a template for story. I want to show how this story-frame can be used, and used well.

Today I’m going to breakdown the major beats of classical design using Pixar’s film Toy Story. This film is an excellent example of how arch plot can create a satisfying story experience that moves like a well-oiled machine and every piece has a purpose. Let’s take a look at how the eleven steps outlined in my previous post are put into practice.

ACT ONE:

1) Ordinary World

In the first images of Toy Story we’re introduced to Andy and his favorite toy Sheriff Woody (our protagonist). In the first minutes we establish Woody’s ordinary world, consisting of Andy’s room. At minute four, we get the story hook: the toys come to life. At this point we’re introduced to the major players: Mr. Potato Head, Slinky-dog, Bo-Peep, etc. Relationships are hinted at and we see that Woody is the leader of this clan. The complexity of this world deepens when the first obstacle is introduced, allowing us to see how Woody normally functions in the ordinary world. The obstacle is Andy’s birthday party and a covert toy-style mission to see if there are any new, bigger and brighter, toys to be worried about. This action reveals the emotional core of the film: every toy’s deepest fear is that they will be replaced and Andy will no longer love them. In the first twelve minutes the film has set up the world, how it works, and what’s at stake.

2) The Call to Action

At minute fourteen, Buzz Lightyear shows up on screen. Something new has arrived to disrupt the ordinary world. This is what the hero’s journey calls the call to adventure. In Toy Story the call isn’t an invitation to a quest, but it is a catalyst that disrupts Woody’s status quo. Woody tells himself that this new toy isn’t going to change anything and we enter…

3) The Refusal of the Call

This is the debate section where Woody tries to keep his authority, but is slowly usurped by Buzz.

4) Crossing the First Threshold

Woody’s refusal culminates when his flaws of pride and jealousy cause him to pick a fight with Buzz. Both toys fall out of the car and Andy’s family drives away, leaving Woody and Buzz on the pavement. The two have now become LOST TOYS! This is the moment when Woody and Buzz cross the first threshold and move us into act two. This is the point of no return. Woody and Buzz are no longer in the ordinary world but the special world, which will force them to grow. The energy of the story changes here because the two have a new desire: to get home.

ACT TWO:

5) Tests, Allies, and Enemies

The next seventeen minutes of the film constitutes the fun and games section where our heroes are presented with tests, allies, and enemies. When I went to film school we called this the “trailer section.” It’s where all the gags and jokes used in a film trailer come from. This is the section of the story that fulfills the promise of your premise. Toy Story’s premise is: how do two rival toys find their way home when lost in the real world? Well, they hitch a ride to pizza planet. They get chosen by The Claw and taken home by the evil neighbor Sid. They defend themselves against cannibal toys. Each obstacle gets harder and harder. And it leads us to…

6) The Mid-Point

In the hero’s journey there isn’t actually a mid-point, but in screenwriting it has become very important story beat. It’s where the energy of the film swings up, or swings down. In Toy Story it swings down. Buzz comes upon a TV commercial selling Buzz Lightyear action figures and realizes he is not the Buzz Lightyear, but actually a TOY!

7) Approaching the In-Most Cave

The mid-point also affects Woody and propels the story into the next section. Woody continues to put out fires while Buzz has his existential crisis. This is known as approaching the in-most cave or continued obstacles and intensification.

8) The In-Most Cave

At minute 57, Woody hits rock bottom and reaches the in-most cave or crisis of the story. Both Woody and Buzz are trapped, Woody’s friends have abandoned him, and he can now see that his pride has led him astray.

ACT THREE:

9) The Final Push

Just after the crisis usually comes a change in fate. Sid takes Buzz into the backyard to blow him up and Woody realizes he must save the only friend he has left. This propels us into act three and the final push where Woody devises a rescue plan.

10) Seizes the Sword

Woody enacts his plan in the climax and seizes the sword by saving Buzz’s life!

11) The Return Home

But the return home is still wrought with tension as Woody and Buzz chase down the moving van. Some consider this a second final climax (think horror films where monsters you thought were dead jump out at the last minute). Woody grows by putting his pride aside and works together with Buzz to reunite with Andy. As the film closes Buzz and Woody have returned to the new ordinary world with the wisdom and friendship of their adventure.

This is classic design used well! It creates an emotionally engaging and well-paced story. If you like this story design I highly suggest reading Sheryl Scarborough’s guest post that continues this discussion in regards to three-act structure.

However, despite popular belief, classic design is not the only way to tell a story. My next post will outline the hidden agenda of arch plot and why we need more storytelling options!

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 6/10/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

The Hero's Journey,

Energic Plot,

Plot,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Classic Design,

Classic Plot Design,

Writing Craft,

Add a tag

Last week I started off my Organic Architecture series by outlining the eleven major story-beats of classical design. Before I jump into alternative structures and plots I want to make sure we understand arch plot as more than just a template for story. I want to show how this story-frame can be used, and used well.

Today I’m going to breakdown the major beats of classical design using Pixar’s film Toy Story. This film is an excellent example of how arch plot can create a satisfying story experience that moves like a well-oiled machine and every piece has a purpose. Let’s take a look at how the eleven steps outlined in my previous post are put into practice.

ACT ONE:

1) Ordinary World

In the first images of Toy Story we’re introduced to Andy and his favorite toy Sheriff Woody (our protagonist). In the first minutes we establish Woody’s ordinary world, consisting of Andy’s room. At minute four, we get the story hook: the toys come to life. At this point we’re introduced to the major players: Mr. Potato Head, Slinky-dog, Bo-Peep, etc. Relationships are hinted at and we see that Woody is the leader of this clan. The complexity of this world deepens when the first obstacle is introduced, allowing us to see how Woody normally functions in the ordinary world. The obstacle is Andy’s birthday party and a covert toy-style mission to see if there are any new, bigger and brighter, toys to be worried about. This action reveals the emotional core of the film: every toy’s deepest fear is that they will be replaced and Andy will no longer love them. In the first twelve minutes the film has set up the world, how it works, and what’s at stake.

2) The Call to Action

At minute fourteen, Buzz Lightyear shows up on screen. Something new has arrived to disrupt the ordinary world. This is what the hero’s journey calls the call to adventure. In Toy Story the call isn’t an invitation to a quest, but it is a catalyst that disrupts Woody’s status quo. Woody tells himself that this new toy isn’t going to change anything and we enter…

3) The Refusal of the Call

This is the debate section where Woody tries to keep his authority, but is slowly usurped by Buzz.

4) Crossing the First Threshold

Woody’s refusal culminates when his flaws of pride and jealousy cause him to pick a fight with Buzz. Both toys fall out of the car and Andy’s family drives away, leaving Woody and Buzz on the pavement. The two have now become LOST TOYS! This is the moment when Woody and Buzz cross the first threshold and move us into act two. This is the point of no return. Woody and Buzz are no longer in the ordinary world but the special world, which will force them to grow. The energy of the story changes here because the two have a new desire: to get home.

ACT TWO:

5) Tests, Allies, and Enemies

The next seventeen minutes of the film constitutes the fun and games section where our heroes are presented with tests, allies, and enemies. When I went to film school we called this the “trailer section.” It’s where all the gags and jokes used in a film trailer come from. This is the section of the story that fulfills the promise of your premise. Toy Story’s premise is: how do two rival toys find their way home when lost in the real world? Well, they hitch a ride to pizza planet. They get chosen by The Claw and taken home by the evil neighbor Sid. They defend themselves against cannibal toys. Each obstacle gets harder and harder. And it leads us to…

6) The Mid-Point

In the hero’s journey there isn’t actually a mid-point, but in screenwriting it has become very important story beat. It’s where the energy of the film swings up, or swings down. In Toy Story it swings down. Buzz comes upon a TV commercial selling Buzz Lightyear action figures and realizes he is not the Buzz Lightyear, but actually a TOY!

7) Approaching the In-Most Cave

The mid-point also affects Woody and propels the story into the next section. Woody continues to put out fires while Buzz has his existential crisis. This is known as approaching the in-most cave or continued obstacles and intensification.

8) The In-Most Cave

At minute 57, Woody hits rock bottom and reaches the in-most cave or crisis of the story. Both Woody and Buzz are trapped, Woody’s friends have abandoned him, and he can now see that his pride has led him astray.

ACT THREE:

9) The Final Push

Just after the crisis usually comes a change in fate. Sid takes Buzz into the backyard to blow him up and Woody realizes he must save the only friend he has left. This propels us into act three and the final push where Woody devises a rescue plan.

10) Seizes the Sword

Woody enacts his plan in the climax and seizes the sword by saving Buzz’s life!

11) The Return Home

But the return home is still wrought with tension as Woody and Buzz chase down the moving van. Some consider this a second final climax (think horror films where monsters you thought were dead jump out at the last minute). Woody grows by putting his pride aside and works together with Buzz to reunite with Andy. As the film closes Buzz and Woody have returned to the new ordinary world with the wisdom and friendship of their adventure.

This is classic design used well! It creates an emotionally engaging and well-paced story. If you like this story design I highly suggest reading Sheryl Scarborough’s guest post that continues this discussion in regards to three-act structure.

However, despite popular belief, classic design is not the only way to tell a story. My next post will outline the hidden agenda of arch plot and why we need more storytelling options!

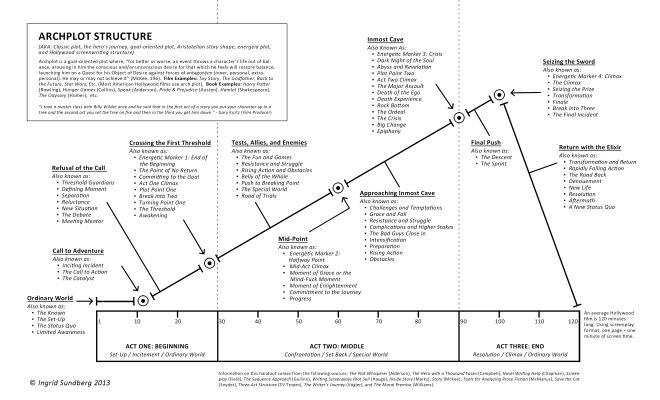

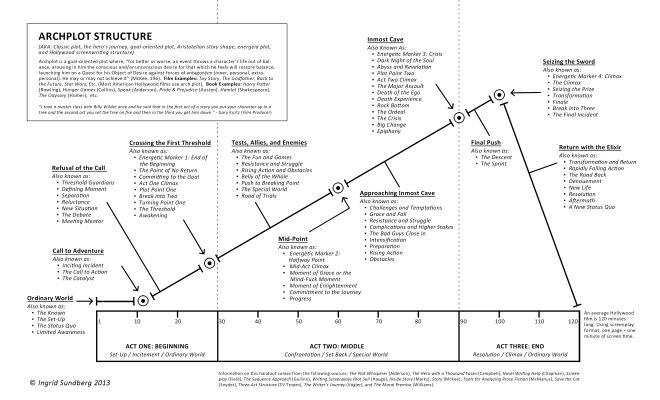

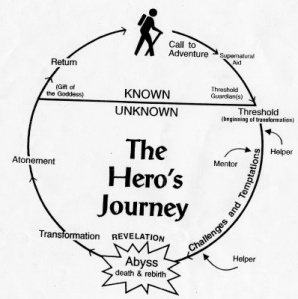

As an introduction to my series on Organic Architecture, I thought I’d start out with the ol’ granddaddy of plot structures: Arch Plot. You probably already know all about this plot structure, but to make sure we’re all on the same page, I wanted to do a quick overview.

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

- Classic plot

- The hero’s journey

- Goal-oriented plot

- Aristotelian story shape

- Energeia plot

- Three-act structure

- Hollywood screenwriting structure

- The Universal Story

Arch plot is a goal-oriented plot where, “for better or worse, an event throws a character’s life out of balance, arousing in him the conscious and/or unconscious desire for that which he feels will restore balance, launching him on a Quest for his Object of Desire against forces of antagonism (inner, personal, extra-personal). He may or may not achieve it” (McKee, 196). Film examples of arch plot include: Toy Story, The Godfather, Back to the Future, Star Wars, Etc. (Most American Hollywood films use arch plot). Book examples of arch plot include: Harry Potter (Rowling), Hunger Games (Collins), Speak (Anderson), Pride & Prejudice (Austen), Hamlet (Shakespeare), The Odyssey (Homer), etc.

A story that uses classic design has eleven basic story sections. Depending on which books you read these story beats all have different titles. I’ve culled the information below from a variety of different sources, each of whom give arch plot design their own title (i.e. classic plot, the hero’s journey, etc.), but at its core they’re all talking about the same design. For the major sequences and beats, the header titles use Joseph Campbell and Christopher Vogler’s Hero’s Journey terminology, and under that you’ll see a list of the same beat termed differently by others. Thus, what Campbell calls the Call to Action, McKee calls the Inciting Incident, and Blake Snyder calls The Catalyst.

THE ELEVEN STORY BEATS OF ARCH PLOT:

ACT ONE

The Ordinary World: The hero’s life is established in his ordinary world.

This story beat is also known as:

- The Known

- The Set-Up

- The Status Quo

- Limited Awareness

Call to Adventure: Something changes in the hero’s life to cause him to take action.

This story beat is also known as:

- TheInciting Incident

- The Call to Action

- The Catalyst

Refusal of the Call: The hero refuses to take action hoping his life with go back to normal. Which it will not.

Also known as:

- Threshold Guardians

- Defining Moment

- Separation

- Reluctance

- New Situation

- The Debate

- Meeting Mentor

Crossing the First Threshold: The hero is pushed to a point of no return where he must answer the call and begin his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 1: End of the Beginning

- The Point of No Return

- Committing to the Goal

- Act One Climax

- Plot Point One

- Break into Two

- Turning Point One

- The Threshold

- Awakening

ACT TWO

Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The journey through the special world is full of tests and obstacles that challenge the hero emotionally and/or physically.

Also known as:

- The Fun and Games

- Resistance and Struggle

- Rising Action and Obstacles

- Belly of the Whale

- Push to Breaking Point

- The Special World

- Road of Trials

Mid-Point: The energy of the story shifts dramatically. New information is discovered (for positive or negative) that commits the hero to his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 2: Halfway Point

- Mid-Act Climax

- Moment of Grace or the Mind-Fuck Moment

- Moment of Enlightenment

- Commitment to the Journey

- Progress

Approaching Inmost Cave: The hero gets closer to reaching his goal and must prepare for the upcoming battle (emotional or physical).

Also known as:

- Challenges and Temptations

- Grace and Fall

- Resistance and Struggle

- Complications and Higher Stakes

- The Bad Guys Close In

- Intensification

- Preparation

- Rising Action

- Obstacles

Inmost Cave: The hero hits rock bottom. He fails miserably and must come to face his deepest fear. This causes self-revelation.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 3: Crisis

- Dark Night of the Soul

- Abyss and Revelation

- Plot Point Two

- Act Two Climax

- The Major Assault

- Death of the Ego

- Death Experience

- Rock Bottom

- The Ordeal

- The Crisis

- Big Change

- Epiphany

ACT THREE

Final Push: The hero makes a new plan to achieve his goal.

Also known as:

Seizing the Sword: The hero faces his foe in a final climactic battle. The information learned during the crisis is essential to beating this foe.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 4: Climax

- The Climax

- Seizing the Prize

- Transformation

- Finale

- Break Into Three

- The Final Incident

Return with the Elixir: The hero returns home with the fruits of his adventure. He begins his life as a changed person, now living in the “new ordinary world”.

Also known as:

- Transformation and Return

- Rapidly Falling Action

- The Road Back

- Denouement

- New Life

- Resolution

- Aftermath

- A New Status Quo

- Return to the New Ordinary World

“I took a master class with Billy Wilder once and he said that in the first act of a story you put your character up in a tree and the second act you set the tree on fire and then in the third you get him down.” – Gary Kurtz (Film Producer)

Bibliography:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

As an introduction to my series on Organic Architecture, I thought I’d start out with the ol’ granddaddy of plot structures: Arch Plot. You probably already know all about this plot structure, but to make sure we’re all on the same page, I wanted to do a quick overview.

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

- Classic plot

- The hero’s journey

- Goal-oriented plot

- Aristotelian story shape

- Energeia plot

- Three-act structure

- Hollywood screenwriting structure

- The Universal Story

Arch plot is a goal-oriented plot where, “for better or worse, an event throws a character’s life out of balance, arousing in him the conscious and/or unconscious desire for that which he feels will restore balance, launching him on a Quest for his Object of Desire against forces of antagonism (inner, personal, extra-personal). He may or may not achieve it” (McKee, 196). Film examples of arch plot include: Toy Story, The Godfather, Back to the Future, Star Wars, Etc. (Most American Hollywood films use arch plot). Book examples of arch plot include: Harry Potter (Rowling), Hunger Games (Collins), Speak (Anderson), Pride & Prejudice (Austen), Hamlet (Shakespeare), The Odyssey (Homer), etc.

A story that uses classic design has eleven basic story sections. Depending on which books you read these story beats all have different titles. I’ve culled the information below from a variety of different sources, each of whom give arch plot design their own title (i.e. classic plot, the hero’s journey, etc.), but at its core they’re all talking about the same design. For the major sequences and beats, the header titles use Joseph Campbell and Christopher Vogler’s Hero’s Journey terminology, and under that you’ll see a list of the same beat termed differently by others. Thus, what Campbell calls the Call to Action, McKee calls the Inciting Incident, and Blake Snyder calls The Catalyst.

THE ELEVEN STORY BEATS OF ARCH PLOT:

ACT ONE

The Ordinary World: The hero’s life is established in his ordinary world.

This story beat is also known as:

- The Known

- The Set-Up

- The Status Quo

- Limited Awareness

Call to Adventure: Something changes in the hero’s life to cause him to take action.

This story beat is also known as:

- TheInciting Incident

- The Call to Action

- The Catalyst

Refusal of the Call: The hero refuses to take action hoping his life with go back to normal. Which it will not.

Also known as:

- Threshold Guardians

- Defining Moment

- Separation

- Reluctance

- New Situation

- The Debate

- Meeting Mentor

Crossing the First Threshold: The hero is pushed to a point of no return where he must answer the call and begin his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 1: End of the Beginning

- The Point of No Return

- Committing to the Goal

- Act One Climax

- Plot Point One

- Break into Two

- Turning Point One

- The Threshold

- Awakening

ACT TWO

Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The journey through the special world is full of tests and obstacles that challenge the hero emotionally and/or physically.

Also known as:

- The Fun and Games

- Resistance and Struggle

- Rising Action and Obstacles

- Belly of the Whale

- Push to Breaking Point

- The Special World

- Road of Trials

Mid-Point: The energy of the story shifts dramatically. New information is discovered (for positive or negative) that commits the hero to his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 2: Halfway Point

- Mid-Act Climax

- Moment of Grace or the Mind-Fuck Moment

- Moment of Enlightenment

- Commitment to the Journey

- Progress

Approaching Inmost Cave: The hero gets closer to reaching his goal and must prepare for the upcoming battle (emotional or physical).

Also known as:

- Challenges and Temptations

- Grace and Fall

- Resistance and Struggle

- Complications and Higher Stakes

- The Bad Guys Close In

- Intensification

- Preparation

- Rising Action

- Obstacles

Inmost Cave: The hero hits rock bottom. He fails miserably and must come to face his deepest fear. This causes self-revelation.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 3: Crisis

- Dark Night of the Soul

- Abyss and Revelation

- Plot Point Two

- Act Two Climax

- The Major Assault

- Death of the Ego

- Death Experience

- Rock Bottom

- The Ordeal

- The Crisis

- Big Change

- Epiphany

ACT THREE

Final Push: The hero makes a new plan to achieve his goal.

Also known as:

Seizing the Sword: The hero faces his foe in a final climactic battle. The information learned during the crisis is essential to beating this foe.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 4: Climax

- The Climax

- Seizing the Prize

- Transformation

- Finale

- Break Into Three

- The Final Incident

Return with the Elixir: The hero returns home with the fruits of his adventure. He begins his life as a changed person, now living in the “new ordinary world”.

Also known as:

- Transformation and Return

- Rapidly Falling Action

- The Road Back

- Denouement

- New Life

- Resolution

- Aftermath

- A New Status Quo

- Return to the New Ordinary World

“I took a master class with Billy Wilder once and he said that in the first act of a story you put your character up in a tree and the second act you set the tree on fire and then in the third you get him down.” – Gary Kurtz (Film Producer)

Bibliography:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

By Sheryl Scarborough

By Sheryl Scarborough

If the writer’s closet of useful tools could be likened to Carrie Bradshaw’s fabu walk-in, masterful accessories such as simile and metaphor would equate to exquisite Louboutin’s and Jimmy Choo’s footwear… exotic word choices would sparkle like Tiffany’s finest… and you would most likely find three-act structure in the drawer labeled: Spanx!

This is my way of saying Three-Act Structure may not be sexy, but once you try it, you’ll wonder how you ever lived without it. What exactly can Three-act structure do for you? I’m glad you asked.

- Simply organizing the main points of your manuscript into a structured beginning, middle and end will give you a comfortably shaped body of character, narrative and pace. (Spanx, baby!)

- Three-act structure streamlines the creative process, allowing you to focus on great dialog and important story points, not the organization of them. (When you’re busy being brilliant who wants to organize?)

- Which part of your story belongs in each act can be defined in enough detail that, once you learn it, you will never forget it. (Can you just give me the crib version? Yes. Read on!)

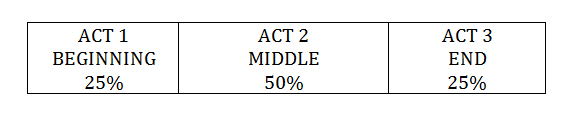

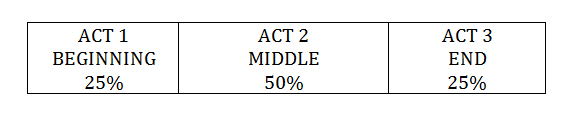

There are plenty of whole books, which define Three-Act structure and demonstrate how it works. For the purpose of this blog I’m just going to give you the basics. Three-Act structure is a specific way to balance and pace your story. The breakdown is simple:

Each Act encompasses a certain number of pages. This is the pacing part. Each act also plays a specific role in telling your story. This is the structure part.

In Act 1 the purpose is to introduce your characters and orient your reader to the setting and world you imagine.

Act 2 is where your story develops; this explains why it’s twice as long as Act 1 and Act 3.

Act 3 should be reserved for the exciting climax and conclusion of your story.

Act 1: Think of a Knight on a Quest…

Act 1 should answer WHO, WHAT, WHEN and WHERE… but not why. It should install your character in his world in a way that quickly orients your reader. Use Act 1 to identify your main character’s problems and introduce us to his friends and foes. Establish his goals and make us care about him.

If you’ve done your job, Act 1 is when your reader develops empathy with your main character. You need for this to happen… don’t blow it. The transition at the end of Act 1 is the point where your character commits to a course of action and your reader settles into her chair and thinks, “okay, here we go.”

Act 2: Facing the Two-Headed Dragon…

If Act 1 is a Quest, then Act 2 is a series of challenges… sort of like facing a two-headed dragon! In Act 1 your reader has learned WHO, WHAT, WHEN and WHERE. By the time she reaches Act 2 she wants to know WHY.

In Act-1 your job was to establish your character’s goal.

In Act 2.1, your job is to play keep away with that goal.

Just like in real life, adversity creates character. The goal of the first half of Act 2 is to throw a series of try/fail obstacles into your character’s path. With each test your character’s commitment becomes apparant. Each time he fails, you deepen his character and reveal more about him… this is how readers find out what he wants and needs and especially how invested he is in his goal.

Not only will your character come alive through these challenges, but as you raise the stakes your reader will become more involved, intrigued and invested in your story.

The length of the trial and error portion of your story is dictated by Three-Act structure. In the first half of Act 2 you are writing toward the mid-point, which is a mere 25% of your total story.

The Mid-point: It Changes Everything…

The Mid-point can be a down moment – the catastrophic end of your character’s goal. Or, it can be an up moment – a moment of shaky success that’s so tenuous and delicate your reader will be worried that this is just one more thing for the main character to lose.

Just remember, the purpose of the Mid-point is that it changes everything.

The Second Half of Act 2: Rebuild the Character’s Goal…

Depending on your Mid-point you have either destroyed your main character’s goal or you have pushed it to such a pinnacle that it is in jeopardy. In either case, the second half of Act 2 asks “now what” or “what now.” This is where you begin to rebuild your main character’s goal. To keep the reader intrigued you must keep the pressure on your main character. Achieving his goals should be hard and take real grit and determination. This is what keeps a reader in their seat.

You also want to begin to bring your storylines together in the last half of Act 2 so that you won’t crowd the climax and conclusion of your story with loose ends.

The End of Act 2: Your Character’s Darkest Moment

Pull out all the stops and really make this moment count. This is the low point your reader has been worried about for your entire novel. And now you must give it to them. Slam your story down on your main character with all the brutality you can muster and I guarantee your reader won’t be able to stop reading.

If you have built your story to this moment, the hopes and dreams that your reader has for your main character will carry them over the end of Act 2 and straight into the climax and conclusion. They won’t be able to put down your book.

Act 3: The Unexpected and Long-Anticipated…

“Act 3 begins with the unexpected and ends with the long-anticipated.“

Author, Ridley Pearson

What this means, is as you conclude your story, you want to make the ending as exciting and unexpected as possible… and yet you want to fulfill your promise to the reader and wrap up the story they expected you would tell. In most cases, your main character will achieve a satisfying goal – maybe not the goal he started out with, but one the reader will accept as a good conclusion to your story.

Example: staying with my Knight on a Quest theme, the end of my story should involve rescuing the Princess – or in my case – The Prince.

But don’t forget to keep an element of surprise… your reader will be working with you to create a successful conclusion to your story.

My surprise that my Knight was really my Princess will be all the more delicious to my reader.

Three-Act structure is writing with purpose!

For more information, check out some of these books that do a good job explaining Three-Act structure:

King, Vicki. How to Write a Movie in 21 Days. HarperCollins Publishers, 1993. Print.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: ReganBooks, 1997. Print.

Schmidt, Victoria. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest;, 2005. Kindle Edition.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat!: the Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City, CA: M. Wiese Productions, 2005. Kindle edition.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 3rd ed. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2007. Print.

Sheryl Scarborough learned Three-Act structure during her 20 year stint as an Award-winning writer for children’s television. Now, a recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in writing for children and young adults, Sheryl has turned her creative attention on writing young adult mystery/thrillers.

Sheryl Scarborough learned Three-Act structure during her 20 year stint as an Award-winning writer for children’s television. Now, a recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in writing for children and young adults, Sheryl has turned her creative attention on writing young adult mystery/thrillers.

Follow Sheryl on Twitter: @scarabs

Read more by Sheryl on her blog: Sheryl Scarborough Blog

The blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness Series.

By Sheryl Scarborough

By Sheryl Scarborough

If the writer’s closet of useful tools could be likened to Carrie Bradshaw’s fabu walk-in, masterful accessories such as simile and metaphor would equate to exquisite Louboutin’s and Jimmy Choo’s footwear… exotic word choices would sparkle like Tiffany’s finest… and you would most likely find three-act structure in the drawer labeled: Spanx!

This is my way of saying Three-Act Structure may not be sexy, but once you try it, you’ll wonder how you ever lived without it. What exactly can Three-act structure do for you? I’m glad you asked.

- Simply organizing the main points of your manuscript into a structured beginning, middle and end will give you a comfortably shaped body of character, narrative and pace. (Spanx, baby!)

- Three-act structure streamlines the creative process, allowing you to focus on great dialog and important story points, not the organization of them. (When you’re busy being brilliant who wants to organize?)

- Which part of your story belongs in each act can be defined in enough detail that, once you learn it, you will never forget it. (Can you just give me the crib version? Yes. Read on!)

There are plenty of whole books, which define Three-Act structure and demonstrate how it works. For the purpose of this blog I’m just going to give you the basics. Three-Act structure is a specific way to balance and pace your story. The breakdown is simple:

Each Act encompasses a certain number of pages. This is the pacing part. Each act also plays a specific role in telling your story. This is the structure part.

In Act 1 the purpose is to introduce your characters and orient your reader to the setting and world you imagine.

Act 2 is where your story develops; this explains why it’s twice as long as Act 1 and Act 3.

Act 3 should be reserved for the exciting climax and conclusion of your story.

Act 1: Think of a Knight on a Quest…

Act 1 should answer WHO, WHAT, WHEN and WHERE… but not why. It should install your character in his world in a way that quickly orients your reader. Use Act 1 to identify your main character’s problems and introduce us to his friends and foes. Establish his goals and make us care about him.

If you’ve done your job, Act 1 is when your reader develops empathy with your main character. You need for this to happen… don’t blow it. The transition at the end of Act 1 is the point where your character commits to a course of action and your reader settles into her chair and thinks, “okay, here we go.”

Act 2: Facing the Two-Headed Dragon…

If Act 1 is a Quest, then Act 2 is a series of challenges… sort of like facing a two-headed dragon! In Act 1 your reader has learned WHO, WHAT, WHEN and WHERE. By the time she reaches Act 2 she wants to know WHY.

In Act-1 your job was to establish your character’s goal.

In Act 2.1, your job is to play keep away with that goal.

Just like in real life, adversity creates character. The goal of the first half of Act 2 is to throw a series of try/fail obstacles into your character’s path. With each test your character’s commitment becomes apparant. Each time he fails, you deepen his character and reveal more about him… this is how readers find out what he wants and needs and especially how invested he is in his goal.

Not only will your character come alive through these challenges, but as you raise the stakes your reader will become more involved, intrigued and invested in your story.

The length of the trial and error portion of your story is dictated by Three-Act structure. In the first half of Act 2 you are writing toward the mid-point, which is a mere 25% of your total story.

The Mid-point: It Changes Everything…

The Mid-point can be a down moment – the catastrophic end of your character’s goal. Or, it can be an up moment – a moment of shaky success that’s so tenuous and delicate your reader will be worried that this is just one more thing for the main character to lose.

Just remember, the purpose of the Mid-point is that it changes everything.

The Second Half of Act 2: Rebuild the Character’s Goal…

Depending on your Mid-point you have either destroyed your main character’s goal or you have pushed it to such a pinnacle that it is in jeopardy. In either case, the second half of Act 2 asks “now what” or “what now.” This is where you begin to rebuild your main character’s goal. To keep the reader intrigued you must keep the pressure on your main character. Achieving his goals should be hard and take real grit and determination. This is what keeps a reader in their seat.

You also want to begin to bring your storylines together in the last half of Act 2 so that you won’t crowd the climax and conclusion of your story with loose ends.

The End of Act 2: Your Character’s Darkest Moment

Pull out all the stops and really make this moment count. This is the low point your reader has been worried about for your entire novel. And now you must give it to them. Slam your story down on your main character with all the brutality you can muster and I guarantee your reader won’t be able to stop reading.

If you have built your story to this moment, the hopes and dreams that your reader has for your main character will carry them over the end of Act 2 and straight into the climax and conclusion. They won’t be able to put down your book.

Act 3: The Unexpected and Long-Anticipated…

“Act 3 begins with the unexpected and ends with the long-anticipated.“

Author, Ridley Pearson

What this means, is as you conclude your story, you want to make the ending as exciting and unexpected as possible… and yet you want to fulfill your promise to the reader and wrap up the story they expected you would tell. In most cases, your main character will achieve a satisfying goal – maybe not the goal he started out with, but one the reader will accept as a good conclusion to your story.

Example: staying with my Knight on a Quest theme, the end of my story should involve rescuing the Princess – or in my case – The Prince.

But don’t forget to keep an element of surprise… your reader will be working with you to create a successful conclusion to your story.

My surprise that my Knight was really my Princess will be all the more delicious to my reader.

Three-Act structure is writing with purpose!

For more information, check out some of these books that do a good job explaining Three-Act structure:

King, Vicki. How to Write a Movie in 21 Days. HarperCollins Publishers, 1993. Print.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: ReganBooks, 1997. Print.

Schmidt, Victoria. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest;, 2005. Kindle Edition.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat!: the Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City, CA: M. Wiese Productions, 2005. Kindle edition.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 3rd ed. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2007. Print.

Sheryl Scarborough learned Three-Act structure during her 20 year stint as an Award-winning writer for children’s television. Now, a recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in writing for children and young adults, Sheryl has turned her creative attention on writing young adult mystery/thrillers.

Sheryl Scarborough learned Three-Act structure during her 20 year stint as an Award-winning writer for children’s television. Now, a recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in writing for children and young adults, Sheryl has turned her creative attention on writing young adult mystery/thrillers.

Follow Sheryl on Twitter: @scarabs

Read more by Sheryl on her blog: Sheryl Scarborough Blog

The blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness Series.

<!--[if gte mso 9]>

0

0

1

509

2903

wordswimmer

24

6

3406

14.0

<![endif]-->

<!--[if gte mso 9]>

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

<![endif]--><!--[if gte mso 9]>

This is the full bibliography for my “To Plot or Not to Plot” series:

FULL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS CITED:

Anderson, M.T. “Two Theories of Narrative.” Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008. Sound Recording.

Ashmore, Calvin. “David Bordwell: Narration in the Fiction Film.” Icosilune. 16 Feb 2009. Web. 16 May 2011.

Atwell, Amy. “It’s All a Matter of Time: Exploring Linear vs. Non-Linear Story Structure.” Romance University, 5 Nov 2010. Web. 10 May 2011. http://romanceuniversity.org/2010/11/05/its-all-a-matter-of-time-exploring-linear-vs-non-linear-story-structure/

“Basics of English Studies: Story and Plot.” English Department. Albert-Ludwigs University Freiburg. n.d. Web. 7 May 2010. http://www2.anglistik.uni-freiburg.de/intranet/englishbasics/Plot01.htm

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect’.”Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011. http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/2700073/ what_is_the_difference_between_plot.html?cat=4

Cowgill, Lisa. “Non-Linear Narratives: The Ultimate in Time Travel.” FilmmakerIQ.com, 17 Aug 2009. Web. 10 May 2011. http://filmmakeriq.com/2009/08/non-linear-narratives-the-ultimate-in-time-travel/

Da Vinci, Leonardo. The Last Supper. 1495-98. Painting. Art History: About.com. Web. 16 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure – The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Art, 2006. Print.

“The Elements of Structure – Plot.” Dramatica Theory Book. Dramatica.com: A Wright Brothers Website. 1994-2009. Web. 7 May 2011. http://www.dramatica.com/theory/theory_book/dtb_ch_16.html

Freytag’s Pyramid. N.D. Graph/Illustration. Narrative Structure: Lit Blog. Web. 16 May 2011.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers. New York: Vintage Books (A Division of Random House), 1983. Print.

Klein, Cheryl. “Talking Books: The Essentials of Plot.” CherylKlein.com. April 2006. Web. 7 May 2011. http://www.cherylklein.com/id18.html

Layne, Ron and Rick Lewis. “Plot, Theme, the Narrative Arc, and Narrative Patterns.” English and Humanities Department. Sandhi

Be sure to read the first six parts of this essay:

Defining Plot Structure:

Defining Plot Structure:

If story structure is a form of organization for a story that may or may not have a plot, what is plot structure? It’s important to note that plot structure is a type of story structure, but the two terms are not interchangeable. The most common story shape for plot structure is the Fichtean Curve (see figure 4). Talked about at length in Gardner’s book The Art of Fiction, this plot structure reflects the goal-oriented plot. In essence, the character has a goal and follows a series of three or more obstacles of increasing intensity in order to achieve that goal. The protagonist reaches an ultimate conflict called the climax and then proceeds to a resolution. This common story shape is often called the Aristotelian Story Shape. However, this may be a falsehood. Aristotle only mentioned that stories should have beginnings, middles, and ends (hence the three act structure). Aristotle had very little to say about plot structure according to author M.T. Anderson:

Structurally in terms of abstract story shape, Aristotle doesn’t really give us much of a pointer. He says ‘for every tragedy there is a complication and a denouement. By complication I mean everything from the beginning, as far as the part that immediately precedes the transformation to prosperity or affliction. And by denouement, I mean the start of the transformation to the end.’ So, it is really more of a two part thing, and he gives you no real sense of the proportion those two things should be in. It’s not actually tremendously useful.

Thus the story shape (the Fichtean curve) came later as others developed new theories of plot structure.

Another common shape is Freytag’s Pyramid, (also called Freytag’s Triangle) which many illustrate with close similarity to the Fichtean curve (see figure 5A). However, this is a distortion, and Freytag’s pyramid is actually symmetrical in its triangular form (see figure 5B), and reflects a Germanic idea of story shape (Anderson). Despite the name, this common plot-structure includes the elements of: Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and a Denouncement. It’s also very popular as Klien points out:

Another common shape is Freytag’s Pyramid, (also called Freytag’s Triangle) which many illustrate with close similarity to the Fichtean curve (see figure 5A). However, this is a distortion, and Freytag’s pyramid is actually symmetrical in its triangular form (see figure 5B), and reflects a Germanic idea of story shape (Anderson). Despite the name, this common plot-structure includes the elements of: Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and a Denouncement. It’s also very popular as Klien points out:

You can see this structure everywhere. It’s Aristotle’s Greek tragedies. It’s all six Jane Austen novels. It’s in all six Harry Potters. It’s mystery novels, romance novels, most every pop song ever written, U2, Stevie Wonder. And the reason for that is, again, catharsis: all the emotion building up through your interest in the characters and their actions, exploding at the climax, leaving you drained but renewed. (Klein, 10

Be sure to read the first five parts of this essay:

Defining Story Structure:

Defining Story Structure:

What is a story structure? To address this question let’s return to Gardner’s original comments above about non-causally related stories. We saw how a story can have a structure without a plot: “novels can be organized… juxtapositionally, when the novel’s parts have symbolic or thematic relationship but no flowing development through cause and effect; or lyrically, that is by some essentially musical principal” (Gardner, 185). Here we have two types of structure: juxtapositional structure and lyric structure. Let’s add to that non-linear structure which we mentioned above, and while we’re at it consider vignette novel structure. In her lecture on verse and vignette novels, Anindita Basu Sempere states that vignette and verse structure “creates snap-shots of characters lives. They’re layered into a collage and the reader has to link these pieces together into a cohesive story.” She goes on to quote Campbell in saying it’s “more like a wheel, with the hub a compelling emotional event, and the narration referring to this event like spokes, so everything is pointing inward to this one main theme or event” (Campbell, qtd in Sempere). Each of these would be an example of story structure: a way to organize the story events without a plot. Of course one could still add plot into the mix if they wanted. It is altogether possible to have a vignette novel with a plot, or a non-linear story with a plot. However, having a plot is not an exclusive criterion for story structure.

Up Next: Part 7 – Defining Plot Structure

** Full Bibliography will be provided at end of blog-post series.

0 Comments on

TO PLOT OR NOT TO PLOT: Part 6 – Defining Story Structure as of 1/1/1900

I’ve spent a lot of time in this organic architecture series talking about plot plot plot plot. (If you’ve missed those post please check out: arch plot, alternative plots, and plot genres). But it’s time to switch gears and think about organization, rhythm, and energy.

I’ve spent a lot of time in this organic architecture series talking about plot plot plot plot. (If you’ve missed those post please check out: arch plot, alternative plots, and plot genres). But it’s time to switch gears and think about organization, rhythm, and energy.

0 Comments on TO PLOT OR NOT TO PLOT: Part 6 – Defining Story Structure as of 1/1/1900

0 Comments on TO PLOT OR NOT TO PLOT: Part 6 – Defining Story Structure as of 1/1/1900

At CraftFest, the writing school component of

At CraftFest, the writing school component of

Thanks! Your posts always get me thinking!!

Great series of articles on Structure. I too am a structure junky. I’m looking for the perfect structural template for rapid story creation. The quest continues!

Hugh, I don’t know that “rapid story creation” exists. Or if it does, if it will have anything worthwhile to say. LOL! My philosophy is to embrace the work and the long and wonderful process of writing a novel! If you find out that secret template, please share!

If you find out that secret template, please share!

Wow. This is great! I particularly love Christopher Nolan’s use of nonlinear structure also in Batman Begins. And this technique was apparent in Man of Steel (with him as producer and story writer with David Goyer). I would love to try this structure one day.

Keep going–you have my rapt attention, Ingrid. Love form and structure.