new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Heros Journey, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 17 of 17

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Heros Journey in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By Candy Gourlay

|

Delivering the eulogy at LJM's wake.

Photo: Amanda Navasero |

I have been in the Philippines for the past couple of weeks. It was a research trip which coincided with the funeral of my first editor and mentor, Letty Jimenez Magsanoc. I was glad to arrive in time to deliver a

eulogy.

I also wrote in the Philippine Daily Inquirer about

her profound influence on my writing (I was one of the Inquirer's two reporters when it started as a weekly, then when it turned into a daily, I became a desk editor). When the article came out on Boxing Day, it amused me that though I haven't used my maiden name 'Quimpo' for 27 years, my former Inquirer colleagues inserted it into my by-line: 'Candy Quimpo Gourlay'.

This visit brought me back to the world that I left behind since I became a writer of novels: a world of intense deadlines, cigarette smoke, clackety typewriters, too much coffee, and the everlasting hunt for a good angle.

|

| The Inquirer newsroom pauses to remember LJM at a final remembrance service . I'm so glad I happened to be in the Philippines. |

It occurred to me that in

story terms, this was the

Ordinary World that I left behind, the way Luke Skywalker left the moisture farm in Tatooine for adventure, Dorothy left behind black and white Kansas for technicolor Oz, and Harry Potter left behind the cupboard under the stairs for magical Hogwarts.

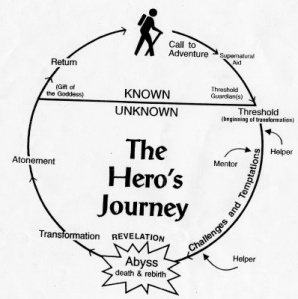

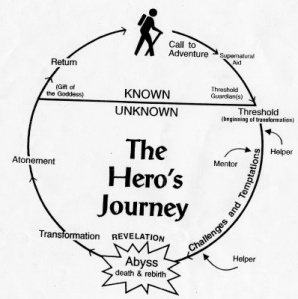

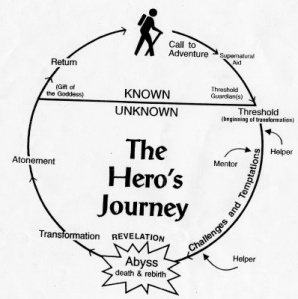

The Ordinary World is the first stage of the Hero's Journey, first articulated by Joseph Campbell in The Hero With a Thousand Faces, and later revised by Christopher Vogler, in a famous seven-page memo he wrote while working for Disney. The Ordinary World introduces the hero's world before he or she goes on an adventure.

The hero's ordinary world is essential to the reader's understanding of the story because it provides the circumstances upon which the hero's adventure can be enjoyed and understood.

One of the reasons for my current trip to the Philippines is to visit the setting of my next novel --

an isolated community in the Cordillera mountains. I came thinking that the task at hand was to feel, to smell, to see, to make the place I'd set my novel in more believable.

|

| The rice terraces of the Cordilleras at sunrise. |

|

| Walking through mountains carved into rice paddies. The tubes are to deliver water from mountain springs to the lower paddies. |

But walking on the narrow trails surrounded by magnificent rice terraces, searching for the sacred trees that stand at the edges of old villages, speaking to people who LIVE the world, I discovered much more about my story than I bargained for.

The Ordinary World is often defined as setting ... the place where a character begins an adventure. But it would be a mistake to focus on it as a bit of geography or a bit of background information.

The Ordinary World is more than geography and backstory. The Ordinary World is context.

Adventure lies in how the characters leave or change the Ordinary World. Without knowing the Ordinary World of a character, it can be hard for the reader to connect with the hero's adventure.

Readers want to be thrilled, they want to be moved, they want to care about what happens to the hero. Without seeing the contrast between the hero's Ordinary World and the world of the adventure, the reader cannot feel the heartbeat of the story.

We are extra delighted by Sophie's adventure with the Big Friendly Giant because we know that she is an orphan.

We root for Katniss Everdeen in the Hunger Games because we know how desperate life is in District 12.

We worry for Auggie in Wonder when he leaves a life of home-schooled security for real school.

When introducing your character's ordinary world, it is too easy to slip into explanation and description. What matters is whether you communicate the context from which your character is about to launch into adventure.

What I've learned from this trip to the Philippines is that in a story, even

place is all about character.

Ultimately, the question we must ask ourselves is: am I merely explaining my character's ordinary world or is he living it?

Happy Friday the 13th! But we usually don't think of this date as a happy one, do we? No, we associate Friday the 13th with dark places and scary events. And that darkness and fear is a very necessary part of being human...and telling a story.

Years ago, whenever I was creatively procrastinating upon a tough job at work, or doing my best to avoid a task that involved conflict, a guy in my office would give me some of the best advice I’ve ever gotten in life: Go where it’s scary.

The only way to work through the problem, to get to the other side, is to face it head-on. Whimping out and avoiding it, as I liked to do, truly didn’t do me any good. It just prolonged the pain.

I’ve always remembered my colleague’s advice, and that phrase, “Go where it’s scary,” comes to mind whenever I find myself dragging toward something I dread but know I must do. This is especially true with my writing. Being the polite Southern girl that I am, I often hesitate to inflict conflict upon my characters, or even worse, have them confront and deal with their innermost pains and fears.

As in life, confronting and traveling through our fears is an essential part of being human, it’s even more so with our characters, our heroes. And no part of story construction addresses “go where it’s scary” more directly than the approach to the innermost cave of the Hero’s Journey.

The Hero's Journey

The Hero’s Journey and its Abyss, or Inmost Cave, is a concept described within Joseph Campbell’s groundbreaking

The Hero With a Thousand Faces. A comparative mythologist, Campbell studied myths separated by continents, centuries, and cultures and discovered that most shared a basic framework, the hero’s quest, which he broke down into 17 steps. Christopher Vogler, a scriptwriter and film producer, simplified Campbell’s work into 12 steps in

The Writer’s Journey, making it more accessible to writers and the film industry. Campbell’s and Vogler’s Journey have been used in storytelling in everything from

Star Wars to

About a Boy to

Harry Potter to insertyourowntitlehere.

At the heart of the Hero’s Journey is the sending forth of the hero from his home clan to begin a series of trials and temptations that lead to his victory over their adversaries, which culminates in his triumphant return with a reward that enriches the clan as a whole. You can see why this basic story structure would have primordial appeal to the human psyche — it is how any human unit, whether that unit be a clan, a family, or a nation — has survived and prospered throughout millennia.

The Abyss:

The Abyss is the point in this journey where the heroine approaches her most intense conflict, her Ordeal. It is in the innermost cave that she must face and conquer both her outward foe and her own personal demons. Cave analogy harkens back to our days when the darkest places we had to fear held deadly creatures that often lurked deep in the places we called our homes. The abyss, or underworld, was the place of loss, where all bodies must eventually travel…that final, unknowable journey.

Whether in the underground, snake-filled “Well of Souls” where Indiana Jones recovers the ark but loses it to the Nazis, or the lonely, cave-like home of Will Freeman in

About a Boy where Will must confront the emptiness of his life, to the underground chamber beneath Hogwarts where Harry confronts Voldemort and the loss of his parents in

Sorcerer’s/Philosopher’s Stone — modern storytellers are still going underground/deep into their cave to set their Ordeal.

In the abyss, the hero meets death and triumphs over his deepest fears, which symbolizes his death to his old life and resurrection to the new. Victory is won — whether that triumph is achieved through vanquishing the antagonist or through atonement with his Shadow. Or, as Joseph Campbell said, “

It is by going down into the abyss that we recover the treasures of life. Where you stumble, there lies your treasure.”

Real Life:

And if our hero can do it in a story, then we can do it in real life. We live vicariously through our hero’s success. If done well, when the book is closed or the movie concluded, we then feel equipped to go back into our life and confront our own demons and monsters. This is the heart of catharsis, and this is why the bestselling books and best remembered movies are those where the hero triumphs over a tremendous obstacle with deep, personal ramifications. It does not matter whether those obstacles are pitched on the intensely personal level or the high-stakes world-wide scale.

As writers, we must remember to send our heroine into the heart of fear. She must go where it’s scariest for her to venture, face those fears head-on, triumph and be forever changed. Only in this way can she return to her world to enrich her clan and ultimately we the writer and our reader.

What abyss have you or your character recently faced and conquered? Picture credits: National Geographic, Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces and Warner Brothers’ Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.About the Author:

|

| S.P. Sipal |

Born and raised in North Carolina, Susan Sipal had to travel halfway across the world and return home to embrace her father and grandfather’s penchant for telling a tall tale. After having lived with her husband in his homeland of Turkey for many years, she suddenly saw the world with new eyes and had to write about it.

Perhaps it was the emptiness of the Library of Celsus at Ephesus that cried out to be refilled, or the myths surrounding the ancient Temple of Artemis, but she’s been writing stories filled with myth and mystery ever since.

Website |

Twitter |

Amazon

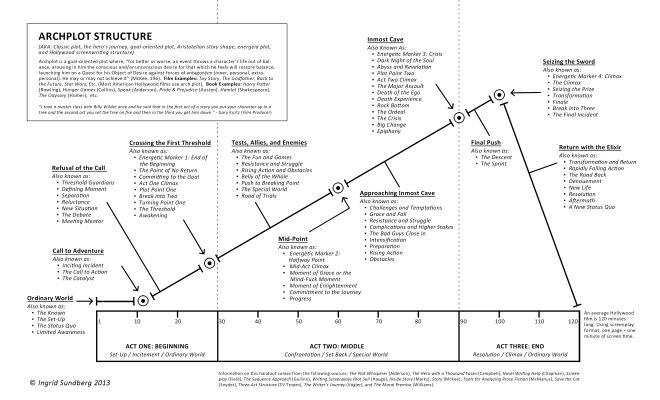

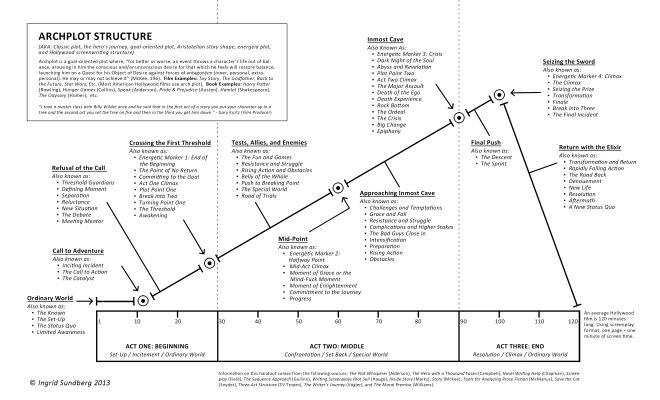

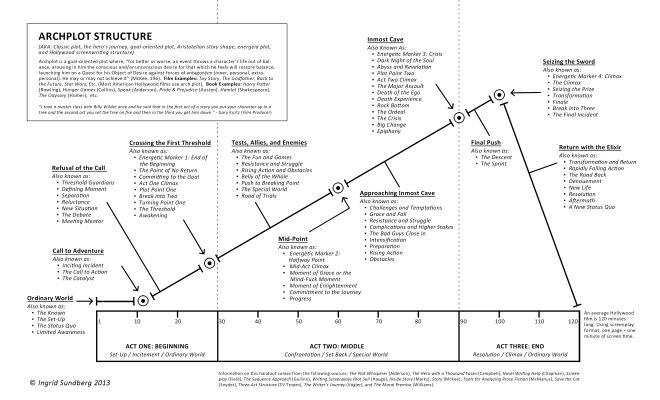

As an introduction to my series on Organic Architecture, I thought I’d start out with the ol’ granddaddy of plot structures: Arch Plot. You probably already know all about this plot structure, but to make sure we’re all on the same page, I wanted to do a quick overview.

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

- Classic plot

- The hero’s journey

- Goal-oriented plot

- Aristotelian story shape

- Energeia plot

- Three-act structure

- Hollywood screenwriting structure

- The Universal Story

Arch plot is a goal-oriented plot where, “for better or worse, an event throws a character’s life out of balance, arousing in him the conscious and/or unconscious desire for that which he feels will restore balance, launching him on a Quest for his Object of Desire against forces of antagonism (inner, personal, extra-personal). He may or may not achieve it” (McKee, 196). Film examples of arch plot include: Toy Story, The Godfather, Back to the Future, Star Wars, Etc. (Most American Hollywood films use arch plot). Book examples of arch plot include: Harry Potter (Rowling), Hunger Games (Collins), Speak (Anderson), Pride & Prejudice (Austen), Hamlet (Shakespeare), The Odyssey (Homer), etc.

A story that uses classic design has eleven basic story sections. Depending on which books you read these story beats all have different titles. I’ve culled the information below from a variety of different sources, each of whom give arch plot design their own title (i.e. classic plot, the hero’s journey, etc.), but at its core they’re all talking about the same design. For the major sequences and beats, the header titles use Joseph Campbell and Christopher Vogler’s Hero’s Journey terminology, and under that you’ll see a list of the same beat termed differently by others. Thus, what Campbell calls the Call to Action, McKee calls the Inciting Incident, and Blake Snyder calls The Catalyst.

THE ELEVEN STORY BEATS OF ARCH PLOT:

ACT ONE

The Ordinary World: The hero’s life is established in his ordinary world.

This story beat is also known as:

- The Known

- The Set-Up

- The Status Quo

- Limited Awareness

Call to Adventure: Something changes in the hero’s life to cause him to take action.

This story beat is also known as:

- TheInciting Incident

- The Call to Action

- The Catalyst

Refusal of the Call: The hero refuses to take action hoping his life with go back to normal. Which it will not.

Also known as:

- Threshold Guardians

- Defining Moment

- Separation

- Reluctance

- New Situation

- The Debate

- Meeting Mentor

Crossing the First Threshold: The hero is pushed to a point of no return where he must answer the call and begin his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 1: End of the Beginning

- The Point of No Return

- Committing to the Goal

- Act One Climax

- Plot Point One

- Break into Two

- Turning Point One

- The Threshold

- Awakening

ACT TWO

Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The journey through the special world is full of tests and obstacles that challenge the hero emotionally and/or physically.

Also known as:

- The Fun and Games

- Resistance and Struggle

- Rising Action and Obstacles

- Belly of the Whale

- Push to Breaking Point

- The Special World

- Road of Trials

Mid-Point: The energy of the story shifts dramatically. New information is discovered (for positive or negative) that commits the hero to his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 2: Halfway Point

- Mid-Act Climax

- Moment of Grace or the Mind-Fuck Moment

- Moment of Enlightenment

- Commitment to the Journey

- Progress

Approaching Inmost Cave: The hero gets closer to reaching his goal and must prepare for the upcoming battle (emotional or physical).

Also known as:

- Challenges and Temptations

- Grace and Fall

- Resistance and Struggle

- Complications and Higher Stakes

- The Bad Guys Close In

- Intensification

- Preparation

- Rising Action

- Obstacles

Inmost Cave: The hero hits rock bottom. He fails miserably and must come to face his deepest fear. This causes self-revelation.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 3: Crisis

- Dark Night of the Soul

- Abyss and Revelation

- Plot Point Two

- Act Two Climax

- The Major Assault

- Death of the Ego

- Death Experience

- Rock Bottom

- The Ordeal

- The Crisis

- Big Change

- Epiphany

ACT THREE

Final Push: The hero makes a new plan to achieve his goal.

Also known as:

Seizing the Sword: The hero faces his foe in a final climactic battle. The information learned during the crisis is essential to beating this foe.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 4: Climax

- The Climax

- Seizing the Prize

- Transformation

- Finale

- Break Into Three

- The Final Incident

Return with the Elixir: The hero returns home with the fruits of his adventure. He begins his life as a changed person, now living in the “new ordinary world”.

Also known as:

- Transformation and Return

- Rapidly Falling Action

- The Road Back

- Denouement

- New Life

- Resolution

- Aftermath

- A New Status Quo

- Return to the New Ordinary World

“I took a master class with Billy Wilder once and he said that in the first act of a story you put your character up in a tree and the second act you set the tree on fire and then in the third you get him down.” – Gary Kurtz (Film Producer)

Bibliography:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

As an introduction to my series on Organic Architecture, I thought I’d start out with the ol’ granddaddy of plot structures: Arch Plot. You probably already know all about this plot structure, but to make sure we’re all on the same page, I wanted to do a quick overview.

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

Arch plot has lots of names. In your time as a writer, you’ve probably run into arch plot under one of these titles:

- Classic plot

- The hero’s journey

- Goal-oriented plot

- Aristotelian story shape

- Energeia plot

- Three-act structure

- Hollywood screenwriting structure

- The Universal Story

Arch plot is a goal-oriented plot where, “for better or worse, an event throws a character’s life out of balance, arousing in him the conscious and/or unconscious desire for that which he feels will restore balance, launching him on a Quest for his Object of Desire against forces of antagonism (inner, personal, extra-personal). He may or may not achieve it” (McKee, 196). Film examples of arch plot include: Toy Story, The Godfather, Back to the Future, Star Wars, Etc. (Most American Hollywood films use arch plot). Book examples of arch plot include: Harry Potter (Rowling), Hunger Games (Collins), Speak (Anderson), Pride & Prejudice (Austen), Hamlet (Shakespeare), The Odyssey (Homer), etc.

A story that uses classic design has eleven basic story sections. Depending on which books you read these story beats all have different titles. I’ve culled the information below from a variety of different sources, each of whom give arch plot design their own title (i.e. classic plot, the hero’s journey, etc.), but at its core they’re all talking about the same design. For the major sequences and beats, the header titles use Joseph Campbell and Christopher Vogler’s Hero’s Journey terminology, and under that you’ll see a list of the same beat termed differently by others. Thus, what Campbell calls the Call to Action, McKee calls the Inciting Incident, and Blake Snyder calls The Catalyst.

THE ELEVEN STORY BEATS OF ARCH PLOT:

ACT ONE

The Ordinary World: The hero’s life is established in his ordinary world.

This story beat is also known as:

- The Known

- The Set-Up

- The Status Quo

- Limited Awareness

Call to Adventure: Something changes in the hero’s life to cause him to take action.

This story beat is also known as:

- TheInciting Incident

- The Call to Action

- The Catalyst

Refusal of the Call: The hero refuses to take action hoping his life with go back to normal. Which it will not.

Also known as:

- Threshold Guardians

- Defining Moment

- Separation

- Reluctance

- New Situation

- The Debate

- Meeting Mentor

Crossing the First Threshold: The hero is pushed to a point of no return where he must answer the call and begin his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 1: End of the Beginning

- The Point of No Return

- Committing to the Goal

- Act One Climax

- Plot Point One

- Break into Two

- Turning Point One

- The Threshold

- Awakening

ACT TWO

Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The journey through the special world is full of tests and obstacles that challenge the hero emotionally and/or physically.

Also known as:

- The Fun and Games

- Resistance and Struggle

- Rising Action and Obstacles

- Belly of the Whale

- Push to Breaking Point

- The Special World

- Road of Trials

Mid-Point: The energy of the story shifts dramatically. New information is discovered (for positive or negative) that commits the hero to his journey.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 2: Halfway Point

- Mid-Act Climax

- Moment of Grace or the Mind-Fuck Moment

- Moment of Enlightenment

- Commitment to the Journey

- Progress

Approaching Inmost Cave: The hero gets closer to reaching his goal and must prepare for the upcoming battle (emotional or physical).

Also known as:

- Challenges and Temptations

- Grace and Fall

- Resistance and Struggle

- Complications and Higher Stakes

- The Bad Guys Close In

- Intensification

- Preparation

- Rising Action

- Obstacles

Inmost Cave: The hero hits rock bottom. He fails miserably and must come to face his deepest fear. This causes self-revelation.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 3: Crisis

- Dark Night of the Soul

- Abyss and Revelation

- Plot Point Two

- Act Two Climax

- The Major Assault

- Death of the Ego

- Death Experience

- Rock Bottom

- The Ordeal

- The Crisis

- Big Change

- Epiphany

ACT THREE

Final Push: The hero makes a new plan to achieve his goal.

Also known as:

Seizing the Sword: The hero faces his foe in a final climactic battle. The information learned during the crisis is essential to beating this foe.

Also known as:

- Energetic Marker 4: Climax

- The Climax

- Seizing the Prize

- Transformation

- Finale

- Break Into Three

- The Final Incident

Return with the Elixir: The hero returns home with the fruits of his adventure. He begins his life as a changed person, now living in the “new ordinary world”.

Also known as:

- Transformation and Return

- Rapidly Falling Action

- The Road Back

- Denouement

- New Life

- Resolution

- Aftermath

- A New Status Quo

- Return to the New Ordinary World

“I took a master class with Billy Wilder once and he said that in the first act of a story you put your character up in a tree and the second act you set the tree on fire and then in the third you get him down.” – Gary Kurtz (Film Producer)

Bibliography:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

Somewhere in your writer’s head is a Master Plot, an idea of what a story or novel should be like, how it should progress. For writers who don’t outline–the write-by-the-seat-of-their-pants writers–the Master Plot is hard-wired into their brains.

For the rest of us, the idea of a Master Plot is helpful.

Hero’s Journey. The hero’s journey can be used for anything from Star Wars to the middle grade classic, Bridge to Terabithia.

Christopher Vogler’s explanation of the Hero’s Journey is excellent. The basic stages, along with the corresponding character arc are these:

- Ordinary World – Limited awareness of problem

- Call to Adventure – increased awareness

- Refusal of Call – reluctance to change

- Meeting the Mentor – overcoming reluctance

- Crossing the First Threshold – committing to change

- Tests, Allies, Enemies – experimenting with 1st change

- Approach to the Inmost Cave- preparing for big change

- Supreme Ordeal – attempting big change

- Reward – consequences of the attempt

- The Road Back – rededication to change

- Resurrection – final attempt at big change

- Return with Elixir – final mastery of the problem

You write comedy or humor and want a plot for a novel?

John Vorhaus, in The Comic Toolbox adapts the hero’s journey into a Comic Throughline.

Similar to the Hero’s Journey is Peter Dunne’s adaptation to a story in which two main characters influence each other, or one character drastically changes a second. The Emotional Structure details how the characters interact. This could be a sort of Rivalry story, a Love story, a Forbidden Love story, or even one of Pursuit, Rescue, or Escape. The main thing here is that two characters act upon each other. Dunne suggests that Acts 1 and 3 are about the outer plot, while Act 2 is the inner journey.

There are other “master plot” ideas, but in discussing the idea of master plots, I like one strategy that Jack M Bickham discusses in his book, SCENE AND STRUCTURE. His “scenic master plot” includes a three-chapter self-contained subplot in the middle of the story, something exciting like a chase scene.

“Chapter Seven. Hero viewpoint. He is embroiled in his three-chapter quest. . . an action sequence, preferably physical: a car chase, a face-to-face confrontation with violent words and emotions, perhaps even an attack on the hero’s life. . .The end of the chapter is at a new disaster which will allow no time for sequel [evaluating what just happened], or at some turning point in the middle of the ongoing scene. This chapter hooks instantly into the next.”

I’ve always thought this was brilliant. Right when the novel is in danger of lapsing into a sagging middle, you insert a subplot of action that resolves over three chapters, while keeping the reader engaged. Of course, it must feed back into the main story after those three chapters and be integral to the story. But it solves so many pacing problems.

Do you have a sort of “Master Plot” that you write by?

Where would you insert a 3-chapter, self-contained subplot that is mostly an action sequence?

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 10/21/2010

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

hero's journey,

write,

how to,

novel revision,

story,

Katherine Paterson,

novel,

Bridge to Terabithia,

character,

plot,

scenes,

Add a tag

Using the Hero’s Journey to Plot

At the Michigan SCBWI conference two weeks ago, I was asked to teach about the Hero’s Journey. Taken from Joseph Campbell’s classic work on folklore, the hero’s journey is a classic paradigm for plot, especially for quest stories. The best book for studying the hero’s journey is The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler.

At the Michigan SCBWI conference two weeks ago, I was asked to teach about the Hero’s Journey. Taken from Joseph Campbell’s classic work on folklore, the hero’s journey is a classic paradigm for plot, especially for quest stories. The best book for studying the hero’s journey is The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler.

While we usually see the hero’s journey used for a quest story, it can be used in many other types of stories, including contemporary children’s stories. Here’s my take on how The Bridge to Terabithia fits into the Hero’s Journey. I doubt Paterson was thinking about this paradigm as she wrote; but it’s a classic paradigm that can shortcut your plotting process and give you something great to work with.

While we usually see the hero’s journey used for a quest story, it can be used in many other types of stories, including contemporary children’s stories. Here’s my take on how The Bridge to Terabithia fits into the Hero’s Journey. I doubt Paterson was thinking about this paradigm as she wrote; but it’s a classic paradigm that can shortcut your plotting process and give you something great to work with.

ORDINARY WORLD

OPENING or BRIDGING CONFLICT: Jess wants to run, but his family doesn’t appreciate him.

Main Supporting Character hinted at: new family moving into Perkin’s old place.

Jess wants to do art, as supported by (Mentor) Miss Edmunds, but his family doesn’t think it’s worth his time to pursue.

Meets Leslie and the first week of classes, she beats all the boys at running. (Notice that Leslie doesn’t enter the story until chapter 3! The Ordinary World is often slighted by beginning writers and this is an excellent example to study for the importance of this stage.)

CALL TO ADVENTURE/REFUSAL

After the race Leslie tries to befriend him, telling him he’s the “only kid in this durned school worth shooting,” but he brushes her off brusquely, telling her, “So shoot me.”

After the race Leslie tries to befriend him, telling him he’s the “only kid in this durned school worth shooting,” but he brushes her off brusquely, telling her, “So shoot me.”

MEETING WITH MENTOR

The one bright spot on the horizon is Miss Edmunds’s weekly visit to the school.

2ND CALL TO ADVENTURE

Leslie admits to class that her family doesn’t have a TV. Jess wants to protect/comfort her, but can’t.

CROSSING THE THRESHOLD

Jess supports Leslie against girl bully, Janice Avery.

Their friendship begins.

TESTS, ENEMIES AND ALLIES

Jess and Leslie’s friendship continues to grow and deepen in the next couple of months, both in school and in Terabithia.

- Enemies: Janice Avery has a subplot of her own.

- Tests: Christmas gifts – Jess finds free puppy, Prince Terrin, for Leslie;

My last post was a bit harsh. I take it back. It is not necessary for a writer to have to go through all that.

My last post was a bit harsh. I take it back. It is not necessary for a writer to have to go through all that.

In my own defense, my purpose here is to support writers achieve their dreams of completing a worthy project. So what about all those half-written stories that end up in the trash bin or at the bottom of a cabinet drawer? Not reaching it, our dreams hound us relentlessly. We never truly forget that which we long for.

People who have faced death say they do not think about the work they missed at the end but of family and friends. Really? Don't you think for even a moment your story might flash before your face and ask, what if?

How does a resistant writer make it all the way to the end?

I wish I could say with grace and splendor but my way is messier. Commit to your own hero's journey as your protagonist embarks on hers.

Learn as much about yourself through the process as you learn about your character.

Recognize the similarities.

Invite in the antagonists.

Ask for answers.

Push yourself.

See what happens.

I'm on the edge of my seat. Will she or won't she?

I'm on the edge of my seat. Will she or won't she?

I left her last time right after she had written the Crisis. Euphoric for having faced every one of her own demons in order to send her protagonist to death -- metaphorically speaking, of course. Still, she wrote it and survived. An embarrassing mass of slop? Likely. All that matters now is getting the scenes written. Before we hang up last time, I gently coax her to face what is coming. She hears my words but does turn around and thus has no idea of the size of the mountain behind her still left to scale.

This time, when she calls, I hear it the minute she speaks. For the first time since we started working together and at the base of Climax Mountain, she hits a wall. Her voice has no energy. She sounds wary. Shell-shocked. Numb and filled with disbelief.

I scramble to assess the damage and uncover something quite unexpected.

From the time she left the middle of the Middle, I worried about her writing the scenes leading up to the Crisis around the 3/4 mark and the Crisis itself. I never even considered her real demons would hit at the End on the way up to the Climax.

Both the protagonist and the writer are drug addicts. The protagonist is killing herself because of her addiction. The writer is in recovery. Not, however, for long. "Two years," she told me. "This time." Having fought my own addictions, I shiver when I heard the second part of her answer. It implies there could be a next time.

Of course, the protagonist has to hit rock bottom at the Crisis. The fact the writer survived the writing of it herself is a tribute to her heart and her spirit.

Now what I think is happening is that because the writer herself has not experienced her own personal transformation fully nor seized her own personal power, she can't quite see the way for the protagonist here at the beginning of the End.

I encourage her to let the protagonist do what she needs to do (the writer knows exactly what she wants to happen at the Climax and thus has only to get her there for now).

Let go of trying to get in the character's head and body. Write purely action now.

Ask the protagonist to reveal herself to you as the powerhouse she can and must be.

Then let her loose, sit back and watch what comes...

Like I said, I'm on the edge of my seat.

Received the following from a writer I'm working with:

"Through our time together, I've come to realize that writing is all about stamina!! I had NO idea how much THINKING and CONNECTING goes into a story. I've done technical writing/reports/research for years but none compares with the effort necessary to craft a story. Novel writing is also much more intriguing and fulfilling."

The writer is crafting a complicated murder mystery with many suspects, thus all the "thinking" and "connecting" he has to do.

I am pleased he finds novel writing intriguing and fulfilling because as soon as he moves from plotting and planning, his true writer's journey begins.

Every protagonist embarks on a journey that sends her both externally and internally into, as yet, undiscovered places. A writer does, too.

The uncertainty of creating something out of nothing often sends a writer spiraling into depression, confusion, blocks, and frustration. The more sensitive the writer, the deeper the abyss.

"If you can do something else," an early writing instructor advised the class. "Do it."

If you can't silence the whispering, still the pen to paper, proceed with a willing heart. Trust the process. Magic happens....

The middle of the Middle is the territory of the antagonists both for the writer and for the protagonist, too.

The middle of the Middle is the territory of the antagonists both for the writer and for the protagonist, too.

Antagonists, internal and exterior, sabotage the protagonist from reaching her goals. The very same antagonists plague the writer as well.

In the Middle, the writer begins to doubt herself. Her way becomes murky. She looks to others for validation. Old beliefs of not being smart enough, good enough, or productive enough turn from a murmur to a roar. She rails against never receiving the credit she believes she is due. Accepts all the old criticisms she throws at herself. She fears. She falters. Her passion for her project wanes. The antagonists begin to win.

Rise up out of the lower energy systems to the "third eye", the place of wisdom -- of intuition.

Listen, not with your mind or through your ego, but to that deeper voice. Make time for yourself. Partner with the process. Pull your protagonist and yourself through the slog and toward the Climax. See your way clear.

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 7/14/2009

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

events,

hero's journey,

antagonist,

3 acts,

plot,

inner plot,

outer plot,

paradigms,

tension,

Add a tag

In part 1, I covered plot patterns beginning with character or beginning with a pattern such as the Hero’s Journey. This continues the discussion of 9 ways to plot.

5. Combinations of Plot Paradigms

Many descriptions of how to write plot combine a couple of these paradigms:

Overlaid with Three Act Structure.

Syd Field: Snowflake + Important Points Paradigm. Syd Field basically advises a Snowflake approach to writing plot, but overlays a paradigm that points to important events and connections among those events. His plot points aren’t labeled with reference to the hero and his journey, but with reference to the three act structure; often, however they coincide. Field works mostly with screenwriters, so is emphasis on the three act structure comes from that.

Emphasis on Inner Plot. Peter Dunne in Emotional Structure: Creating the Story Beneath the Plot likewise has a chart of events, with a variation of the hero’s journey. Dunne, however, emphasizes the difference in the inner and outer plot, relegating most of the outer story to acts one and three, leaving act two as the character or inner plot. Same story, but with a variation when you want the story to be about two people changing each other. It won’t work, though, when the main antagonist is man v. nature or man v. himself.

To emphasize the importance of both inner and outer plots, Dunne recommends you write plot points on an index card with the outer conflict on one side and the inner conflict on the other.

Major Change at Midpoint. Another idea for patterns is from David Seigel, a screenwriting, who emphasized that at the midpoint of a story, there must be a change in the main character’s goal. It’s the understanding that interesting characters grow and their needs and wants change because of events. His classic example is from The Lion King. In the first half of the story, Simba wants to be happy; in the second half, he wants to be restored to his rightful place as king of the lions. Seigel said that without this major change, stories are ineffective. He basically falls in with the hero’s journey type structure, but puts his emphasis on this major shift of the story. (Seigel had his plot paradigm on line at one time, but it’s no longer available.)

6. Emphasis on Writing in Scenes

One other variation in writing and plotting novels is the emphasis or de-emphasis on writing in scenes. Screenplays and theater plays must be written in scenes, but novels can be fuzzier about this and still succeed. However, I think there’s value in learning to write in scenes, as it keeps a story focused better. Dwight Swain’s classic Techniques of the Selling Writer, is followed by Jack Bickham’s Scene & Structure. One of the most helpful on scene writing is Sandra Scofield’s The Scene Book: A Primer for the Fiction Writer.

When you write in scenes, it’s possible to plan every scene in a novel, as Swain and Bickham recommend. But generally, you need some other paradigm of the overall structure to do a good job of it.

7. MICE quotient

There are other approaches to plot patterns that I find less helpful; nevertheless, knowing them sometimes makes it easier to be bold in doing something different. For example, Orson Scott Card in Character & Viewpoint discusses the MICE quotient: stories are governed either by their milieu (For example, fantasy which invents and explores a new world), an idea (mysteries), a character (romance or character novels) or an event (an imbalance in the world, an injustice that must be put right). The author’s focus on one of these elements determines what actually makes it into the story.

For example, on The Lord of the Rings, it could be classed as an event story, with the Dark Lord disturbing the balance of the world order. Card argues, though, that it is rightly understood as a milieu story. The story begins in the Shire, travels through Middle Earth, and as it is destroyed by the battle, it returns to the Shire; Frodo can’t remain there, though, because he’s been too damaged by his contact with evil, and takes the boat ride with the elves across the Western Sea. If it was just an event story, the story ends with the defeat of the Dark Lord. But as a milieu story, it doesn’t end until we see the end of Middle Earth.

8. Author’s idiosyncratic plot pattern

Hero’s journey overlaid with the process of grief. Pattern can also come in the shape of any process of change or growth that a human might undergo. For example, in my novel, The Wayfinder, I used the process of grief as a structure: loss, denial, acceptance, healing, You can even combine several of these structures: the process of grief overlays the hero’s journey for a more complex structure.

Patterns can come from any other source: you can think of a novel as peeling away layers of an onion; as way-stations on a long journey; as episodes.

What plot patterns work best for you?

Books Mentioned in This Series

- Bickham, Jack. Scene & Structure

- Card, Orson Scott. Character & Viewpoint

- Dunne, Peter Emotional Structure: Creating the Story Beneath the Plot

- Field, Syd.

- Noble, June & William. Steal this Plot.

- Scofield, Sandra. The Scene Book: A Primer for the Fiction Writer.

- Swain, Dwight.Techniques of the Selling Writer

- Tobias, Ronald. 20 Master Plots

- Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey.

- Vorhaus, John. The Comic Toolbox.

Websites Mentioned in This Series

Next: Enhancing the Basic Plot

Related posts:

- Plot: Characters v. Patterns

- How to Use Scenes to Plot

- Keep the Main Plot the Main Plot

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 7/13/2009

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

ally,

enemy,

novel,

character,

plot,

hero's journey,

branch,

how to write,

villain,

Joseph Campbell,

snowflake,

Add a tag

Plot: 9 Ways of Looking at Plot

I’ve been thinking about plot and looking through my library of writing books to see the big picture of how plot is discussed and taught, how writers approach plot. It seems to me that the discussions fall into about 9 camps.

1. Plot equals character. This camp says that the characters and their problems will move the story. If you know your characters well enough, they will get into and out of scraps and fights and interesting problems. Usually, but not always, this is accompanied with the encouragement to just start writing and see where the character takes you.

It seems to me that people who successfully write this way have a deeply ingrained, unconsciously competent, intuitive grasp of a story arc that includes a character facing his deepest fears and growing or changing some way as a result. As they write, they try to align the character with this inner sense of character. In Jack Bickham’s book, Scene & Structure, one appendix is of a Master Plot, detailing one particular way to conceive of the plot structure; authors who begin with character have an internal Master Plot of character.

It seems to me that people who successfully write this way have a deeply ingrained, unconsciously competent, intuitive grasp of a story arc that includes a character facing his deepest fears and growing or changing some way as a result. As they write, they try to align the character with this inner sense of character. In Jack Bickham’s book, Scene & Structure, one appendix is of a Master Plot, detailing one particular way to conceive of the plot structure; authors who begin with character have an internal Master Plot of character.

Those who are unsuccessful at this approach can create interesting characters who do interesting things, but they don’t key in to the deepest fears, don’t make the character suffer and change and grow.

Other readings about starting with character:

2. Plot is a branching structure. If you start with a single statement, you can split it to two statements, and split that to four and that to eight and so on. Examples of proponents of this method are the Randy Ingermanson’s Snowflake Method, and How to Write a Damn Good Novel by James N. Frey.

Basically, you start with the Deep Theme (Snowflake) or Premise (Frey) which could describe the entire novel in a single sentence. Then you develop it by making it two (or three) sentences. Then each of those is divided into several sentences, 4-6 sentences. And so on.

The key to this is knowing, rather than discovering, the deep theme or premise. Some people start from the thinnest of threads and need those exploratory drafts to find out about character and theme. If you fall into this camp, then use Snowflaking as a revision strategy, instead of a first draft strategy.

More reading:

3. Universal Plots. Some say there are only two plots in the world: a stranger comes to town or a character goes on a journey. Ronald Tobias’ book 20 Master Plots discusses some of the major universal plot schemes and generally lays out a structure for each; most helpful is when he designates some as character plots and others as action-oriented plots. For example the difference in a Quest and an Adventure is whether you focus on the inner or outer plot.

Other books in this vein are the classic from June & William Noble, Steal this Plot.

Or look at this 1916 book, which expresses the same idea of universality of plot:

4. Plot Patterns. Plot is a series of events that present the character with increasingly difficult choices until at the climax the conflict is resolved. This is the basic narrative arc you learned in high school. It may be enough to analyze a story by, but I’ve rarely seen it successful in leading a writer through the convolutions of plot.

However, there are patterns of plot which would fit the general idea of a narrative arc. The Hero’s Journey (orginally from Joseph Campbell, but best presented for writers by Christopher Vogler in The Writer’s Journey) establishes steps a character must face: call to action, denial, crossing the threshold, enemies & allies, approach to the inmost cave, supreme ordeal, reward, the road back, resurrection, return with elixir. John Vorhaus proposed a similar idea with his Comic Throughline in The Comic Toolbox.

I find this type pattern helpful because it fills in the smaller details left out by the English teacher’s description of plot. The Hero’s Journey is open-ended and general enough to allow for flexibility, while still being specific enough to point the writer in a useful direction. In other words, the English teacher’s plot says that the character faces a series of obstacles before reaching a final climax. The Hero’s Journey describes what some specific obstacles will look like AND it sequences those obstacles into an ideal timeline.

Books Mentioned in This Series

Websites Mentioned in This Series

Do you use one of these plot paradigms? Why that one?

Tomorrow: 4 more variations of plotting.

Related posts:

- Keep the Main Plot the Main Plot

- How to Use Scenes to Plot

- Novel Characters Transform

A local wrestler wins the state title. In the beginning, odds were against him due to internal fears and flaws. The newscast chronicles his story with a thematic flair that it's not unusual for someone to binge on toxic food when faced with possible success. Wrestler's dad seemed also to serve as antagonist in someway personal to the family itself. Mom sends the boy on a journey to an exotic land. He trains at a wrestling camp, sheds his old beliefs, practices important new steps, returns home and wins the state title.

The newcaster's easy acceptance of our often compulsive and self-sabotaging behaviors when faced with possible success was refreshingly honest...

Isn't that what writer's block is all about? Self-sabotage. Isn't that why so many writers have never finished a story? Or if they have, it sits on a bottom shelf in the dust?

Moving forward, becoming conscious, finishing, showing up takes energy and trust, study and discipline.

Discipline... When did it become associated with punishment? "You'll be disciplined for that..." Only in the past decade or so have I come to understand the other side. Root word of discipline is disciple. A writer who writes and finishes serves as a disciple of the creative force.

It takes energy and discipline to achieve our goals in life and never more so than in a writers life.

How do you keep energetically strong?? What is your discipline???

By:

Phyllis,

on 2/4/2008

Blog:

The Art of Phyllis Hornung Peacock

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

boat,

illustration,

painting,

Texas,

squirrel,

hiking,

boat,

Austin,

hike,

mangrove,

drangonfly,

mandolin,

swamp,

drangonflies,

bull creek,

hiking,

Austin,

hike,

mandolin,

mangrove,

drangonfly,

swamp,

drangonflies,

bull creek,

Add a tag

By: Mark Peter Hughes,

on 7/9/2007

Blog:

Lemonade Mouth Across America! Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

church ladies,

frank,

petey,

jonathan,

bryan,

beverly,

pettine,

austin,

stephan,

finger,

pat,

sopapillas,

francesco,

animals,

jonathan,

church ladies,

frank,

petey,

bryan,

beverly,

pettine,

austin,

stephan,

finger,

pat,

sopapillas,

francesco,

Add a tag

MARK: Today I had help from Lucy, age 8, with today’s update. I asked her to talk about our stays in Bryan and Austin, TX while I typed what she said. Full disclosure – I took what she said and changed the order of some sentences so that it goes in chronological order. Otherwise, though, this is what she said. Her comments are in the larger font.

LUCY: When we came into Texas, we were listening to a song named "After Breakfast Let’s Go to Texas.” My mom and dad are in a band that’s called the Church Ladies and it's their song.

We went to Bryan, Texas and stayed with Petey, my mom’s friend. Petey is a really nice man. We walked around Texas A and M. It was really hot out and I liked it a lot. Petey told us about butterflies and Texas Rangers and trees.

MARK: For the Texas A&M football team, there is great importance given to "The Twelveth Man." Here's Karen with her hand on the thigh of that hallowed player.

Also, in Bryan we finally got our antenna fixed! Yay! Here's a picture with Daniel from the Honda dealer. Such a nice guy!

LUCY: We went to a restaurant. It was my dad’s birthday. It was a Mexican restaurant and I tried Sopapillas and I loved them. In the Sopapillas we put a candle and sang Happy Birthday to my dad.

Another day we went to Aunt Pat and Uncle Frank’s house in Austin, Texas. We saw Suzanne and Stephen my second cousins and Francesco, which is a baby, my new cousin. Francesco was 3 months old when I met him. He was really cute. I love the way that he holded on to my finger.

MARK: Here's Zoe with lovely Francesco, and then my family:

MARK: While we were at in Austin, Lucy decided to play with my aunt’s weight set and promptly dropped a 5lb weight hard on her left ring finger. It then proceeded to turn purple and swell up. It’s still purple and swelled, but a bit better now. And she can move it around, so we’ve decided it must be okay. Yet another adventure with Lucy.

(I have a picture of Lucy's finger but Karen seems to have hidden the camera and she's asleep right now -- the nerve! -- so I can't download it. But I'll put it up here soon)

LUCY: We went to lots of bookstores and me and Zoe got these little stuffed animals and my brother got a hat. We went in the kids section and played with the trains.

MARK: We loved the beautiful state capital building -- where we arrived just in time for an amazing tour. And we remembered the Alamo...

We visited an amazing independent bookstore in Autsin called Book People. They were very kind to us!

At a Barnes and Noble in Austin we had an unlikely encounter too strange for fiction: I was standing there talking with a bookseller when I heard a woman’s voice behind me say, “Mark? Mark Hughes, is that you?” I turned around and there, out of the blue, stood a familiar face from Rhode Island. Beverly Pettine is a friend of the family who used to work with my mother. Beverly doesn’t live down here in Texas--it was just a strange coincidence that she just happened to be visiting her sister in Austin (who knew?) and just happened to be in exactly the right the bookstore with her sister and niece when she saw a sign announcing that I was going to be appearing here. She looked at the time and my appearance just happened to be exactly when she was here. If I were to put that in a story, no one would believe it. Yet, here’s the proof: Here I am with Beverly in front of our car in Austin, TX, of all places. Whoda thunk? :-)

We also had a very nice afternoon with friends of friends. Our neighbor, Jay, grew up in the Dallas area so we were very pleased to meet Brad, Holly, Katie, and Grace, who live in Austin. Lovely people and our new friends in Texas. :-)

LUCY: Yesterday we went to Stephen and Jonathan’s house and they have five dogs. Their names were Max, Casey, Billy, Toby, and Lloyd. They were cute. I loved to pick Max up. He was the littlest but he was 31 years old. We went in Stephen and Jonathan’s pool and swam. Stephen and my dad and mom threw us in. It was really fun.

Right now my brother and sister are filling their stomachs with Cheetos. We’re driving to Dallas, Texas. We’re going to stay with Gigi. We were just listening to High School Musical in the car.

MARK: A sad note: I just got some terribly disappointing news from NPR – they are not going to air the road-trip stories after all. Given their already busy line up and the fact that the producer working with me will be away in Alaska for a month starting this week, they made their decision not to go forward with the road-trip stories. I can’t tell you how disappointed I am about this. I sent out the message about NPRs decision earlier this morning and was truly touched by the many, many the kind emails people sent in reply. I’m grateful to have such a supportive network.

On the other hand, I’ve already learned a great deal from working with NPR so far, and the experience has been a lot of fun. Perhaps after the summer is over I’ll submit some commentaries in the style of the first one, where I talked about quitting my job. We’ll see.

In any case, this is so far the only significant set-back in an otherwise successful and happy road trip/book tour. And I’m determined to get over it before we reach Dallas. :-)

I appreciate your friendship.

-- Mark

LEMONADE MOUTH (Delacorte Press, 2007)

I AM THE WALLPAPER (Delacorte Press, 2005)

www.markpeterhughes.com

Today I was determined to get a new entry written and then work on subplots for STARVED. Here it is, though, past 10:30, and I'm just settling down to work. I had to contact a representative from an educational publishing company to get copyright info on a math problem that I found on the web for HUNGRY. I got a letter from him last year, but there was some technicality to look into. So . . . behind schedule!

Today I was determined to get a new entry written and then work on subplots for STARVED. Here it is, though, past 10:30, and I'm just settling down to work. I had to contact a representative from an educational publishing company to get copyright info on a math problem that I found on the web for HUNGRY. I got a letter from him last year, but there was some technicality to look into. So . . . behind schedule!

Much of my energy this week has been spent packing for our trip to Chile (leaving soon!) and working with a district committee to hammer out our English Learner program (dealing with boring stuff like forms, so all the schools in the district are on the same page).

Back to plotting: as a writer, plot is the hardest thing for me to deal with. I do outline after outline, but what seems to be logical often doesn't work when I'm actually trying to write. My good friend and mentor Bruce McAllister (a great writing coach: http://www.mcallistercoaching.com/) suggested I get the book Myth and the Movies, by Stuart Voytilla and study how the hero's journey, the archetypal "template" that all good stories follow, is applied to various film genres: science fiction, thriller, romance, romantic comedy, history, etc. The process works just as well for all stories: movies, novels, short stories.

I find that I don't enjoy a lot of movies anymore because I know what's going to happen: toward the end of the movie, the protagonist gets his or her reward which signals that the biggest hurdle is on its way. I was a little reluctant to use the process when I first read the book. Now, though, looking at it again after a year, I see what a powerful tool it is.

I've drafted the main plot of STARVED (at least I've done a first run of it) on a circle chart using the elements as described in Myth and the Movies: starting in the ordinary world, encountering a mentor, refusing the call to adventure, accepting it, crossing the threshold to a special world, facing tasks, symbolically dying through an ordeal, coming back into the ordinary world with a reward, being resurrected on the road back to the ordinary world, and returning with an elixer. There is also a character arc that correlates with plot points. Having this structure really did make the story I want to write easier to conceive.

I want to do the same process with the two subplots for STARVED later today. All three circles (or more if I have time to do character archs) will go with me to Chile. I work best when I give myself deadlines, so I've promised myself that I'll have a strong beginning for the book before I return.

Since I write about the hero journey today, the peace dove is for the young men and women in Iraq. I hate this war and don't believe in it, but my heart goes out to those who are in the middle of it. I just heard that one of my former students is headed for the army. I know that there are many kids I used to teach over there. I wish them safety, a swift return home, and peace for everyone in that tattered country.

It seems to me that people who successfully write this way have a deeply ingrained, unconsciously competent, intuitive grasp of a story arc that includes a character facing his deepest fears and growing or changing some way as a result. As they write, they try to align the character with this inner sense of character. In Jack Bickham’s book,

It seems to me that people who successfully write this way have a deeply ingrained, unconsciously competent, intuitive grasp of a story arc that includes a character facing his deepest fears and growing or changing some way as a result. As they write, they try to align the character with this inner sense of character. In Jack Bickham’s book,

Excellent analysis of archplot structure. And I have to laugh, because when you mentioned granddaddy in the first paragraph, I glanced at the little character figure in the diagram, and it looks like an old man on a cane!

Do you find that people are moving away from this model?

L.Marie, No, I don’t find people straying from this model very much. In fact, I often find myself disappointed with stories because they seem to insert this model over the story without giving it real room to breathe. Don’t get me wrong, there is a place for this model of storytelling. But many think it’s the only model and try to force their story to fit into it. More on this in coming posts!

I can’t wait for the follow up post to this, Ingrid. I love studying this classic structure, but I’m against using it as a roadmap. What you’re calling “room to breathe,” I call stretching the mold. Study it, know it and then make it malleable!

Make it malleable indeed!

Great post!

Thank you.

Hugs, Sal

I wanted to run off and become a samurai but my mother caught me and made me peel potatoes. Then there was a fire at the neighbor’s and I took the chance to run away for real.

The samurai I met laughed at me and drank a lot of sake. They were nothing like I expected. But there was one swordsman who was special. He saw my potential and taught me. I wandered as a ronin for many years, honing my skills. When Lord Satsuma heard about me I was summoned to become his tutor.I refused. I felt my own training was incomplete. The Daimyo was furious and declared me an outlaw. My arch-rival Noriyama got the post instead.

To make a long story a lot shorter, I exposed Noriyama as a traitor and slew him in a duel in front of Lord Satsuma and his retinue. Now I was ready to take up my responsibilities. I married the Lord’s daughter and continued on to the sequel.