new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Academic Painters, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 202

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Academic Painters in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

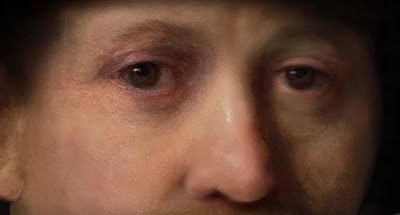

A team of scientists used statistical analysis, deep learning algorithms, and 3D printers to create an image that is intended to look like a typical Rembrandt.

Here's how they did it (Link to YouTube)

Read about the process on The GuardianThanks, Dan

|

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Self-Portrait, ca. 1620–21

oil/canvas 47 1/8 × 34 5/8 in. (119.7 × 87.9 cm) |

The exhibition contains about 100 drawings and paintings, making it the largest US exhibition of his work in over 20 years.

The show includes many of his supremely elegant finished portraits from Italy, France, Flanders, and England. But it also delves into his sketches and drawings, with considerable scholarship devoted to his preparatory sketches and working methods.

|

Anthony Van Dyck Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1640

29 7/8 × 23 1/4 in. (75.9 × 59.1 cm)

Speed Art Museum |

About the portrait above, for example, the curators note:

"The treatment of the face is highly finished and refined, but the woman’s bust and hand await finishing glazes, and there are extensive areas of unpainted canvas that suggest a shawl wrapped around her body. As with many other works from his London studio, Van Dyck must have painted his sitter’s face from life, resulting in a halo still visible around her head. A workshop assistant would probably have completed the painting of the background and draperies before Van Dyck applied a few final touches."

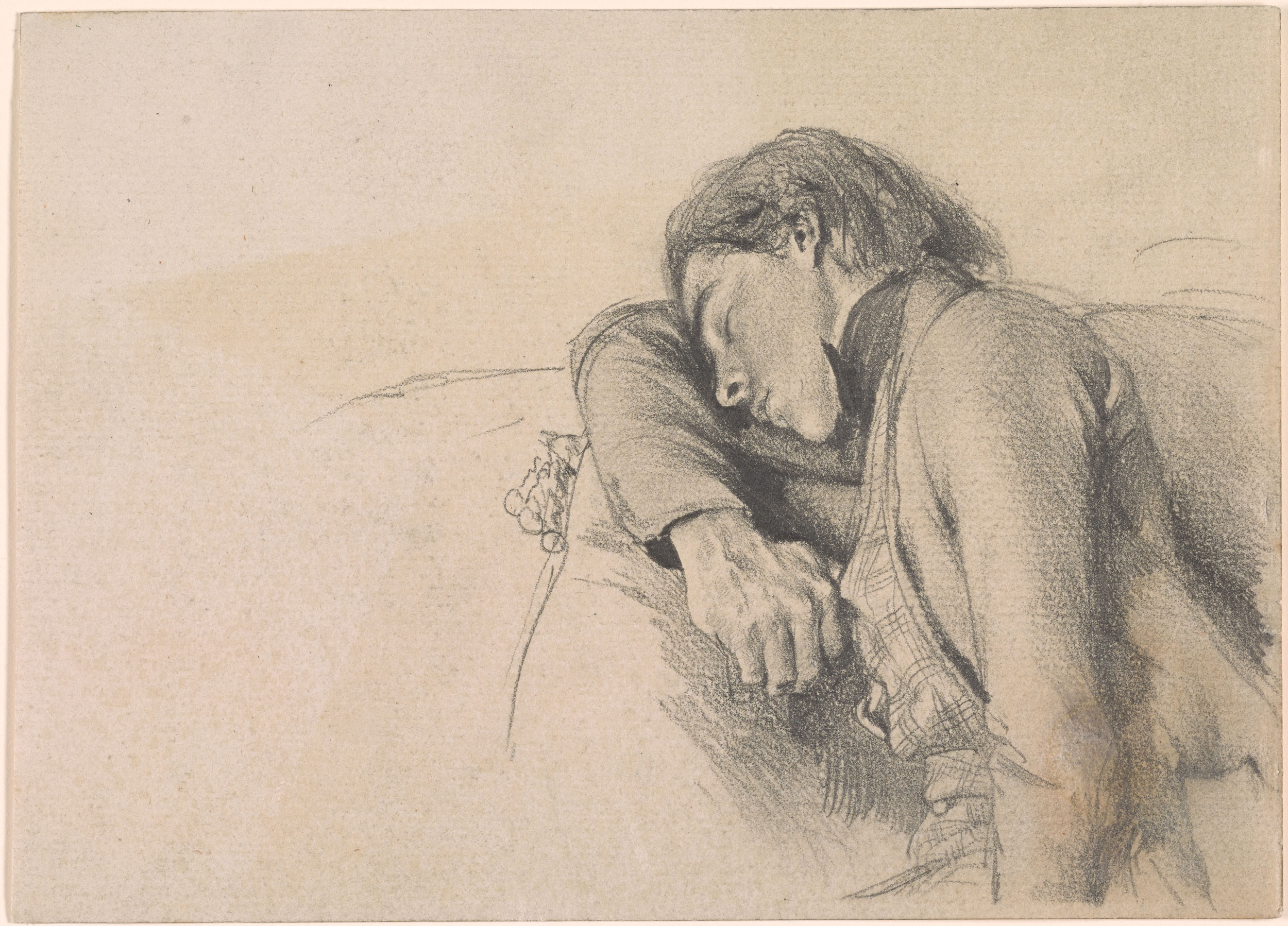

For larger and more complex group portraits, Van Dyck painted individual studies from life. This one was only rediscovered in 2000 during an

episode of Antiques Roadshow.

|

Van Dyck, drawing of Sebastiaan Vrancx, ca. 1628–31

7 x 10 inches, black chalk |

The show includes his informal sketches of fellow artists, which conveys the spirit of camaraderie that must have prevailed among working artists. Sebastiaan Vrancx was known for his landscapes and battle scenes, as well as being a poet, playwright, and book illustrator.

----

Catalogue:

Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture

Online:

Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture, March 2, 2016 to June 5, 2016

Survey the exhibition in expandable thumbnails at their

Visual indexVideo lecture by

Stijn Alsteens: "Drawing for Portraits"

Today we'll continue Chapter 9: "Painting from the Life" from Harold Speed's 1924 art instruction book Oil Painting Techniques and Materials

Today we'll continue Chapter 9: "Painting from the Life" from Harold Speed's 1924 art instruction book Oil Painting Techniques and Materials .

.

I'll present Speed's main points in boldface type either verbatim or paraphrased, followed by my comments. If you want to add a comment, please use the numbered points to refer to the relevant section of the chapter.

Today we'll cover pages 173-180 of the chapter on "Painting from the Life," where he talks about Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, Frans Hals, and Rembrandt van Rijn.

|

| Sir Joshua Reynolds unfinished portrait |

Reynolds

1. Reynolds executed his portraits in monochrome and then glazed the color over it.The unfinished portrait above shows how his portraits must have looked in progress.

2. Reynolds' business approach for portraitsHe'd charge half on commencement and the second half on satisfaction. But "he had a room full of rejected portraits in his house when he died." According to Speed, he produced 150 portraits per year.

3. "The smaller the source of light, the less half-tones you get."Sharp, small lights create a sharp division of light and shadow. Soft light, which comes from large light sources (large windows or exposure of sky) leads to a more gradual shift from light to shadow.

Speed argues that smaller sources are more flattering, but that's generally not the consensus among portrait painters and photographers. Photographers of women in particular routinely use softer or more diffused lights, that is lights that emanate from a larger area. This soft light downplays highlights and unwanted lines and texture in the halftones.

4. Simplifying the modeling will flatter a face, even without changing the features or proportions at all. Powdering has the same effect by reducing highlights."The artist is not obliged to catalogue all these details." He says that a "mean vision," (meaning one that focuses on small, trivial forms) misses out on the larger, nobler vision.

I think what Speed is recommending is using a relatively smaller source of light, but ignoring or downplaying the minor details of wrinkles and highlights.

|

| Gainsborough The Painter's Daughters (with ghost cat) |

Gainsborough

5. Method: paint thinned with turps and linseed oil. Commenced by rubbing in with burnt umber cooled with terra vert (green).This produces cool half-tones, into which reds and yellows are added into the lights, followed by darker accents. Note the drawing with the brush on the toned canvas. Also note the ghost cat.

In ateliers, the coloring of the first painting is called "dead coloring," and it is brought to life with warm glazes later.

6. "Swift unity of impression is one of the secrets of the charm, a thing that must always be caught on the wing."Painting children is always improvisational, even in Gainsborough's day.

|

| Hals 30 Year Old Man with a Ruff, London |

Frans Hals

7. Spontaneous handling, painted with a simple palette. Painted with soft brushes, not hog hair (bristle). Speed speculates that a painting like the one above was accomplished in one sitting.

8. Blacks: thin painting over a warm ground.Note the brushwork in the ruff. Speed notes that it was painted with a gradated middle tone into which he has flicked lights and darks.

|

| Rembrandt Head of an Old Man |

Rembrandt

9. Analyzing R. is more difficult because of his variety of handling.Paint laid in with broken color and glazes, and sometimes with direct opaque handling. Generally Rembrandt reserves the thick paint for the lights, and keeps his darks smooth and transparent.

10. Color: "Rembrandt was a great master of getting the utmost variety out of a few earth colors."That was true of most of the old masters. Ultramarine blue, so common today because it has been chemically synthesized, was more expensive than gold, and was usually reserved for the cloak of the Virgin Mary.

Next week— Tone and Color Design

-----

----

GurneyJourney YouTube channel

My Public Facebook page

GurneyJourney on Pinterest

JamesGurney Art on Instagram

@GurneyJourney on Twitter

In the foreground there's a full range of values used to model the foliage. The leaves and branches are painted individually, with considerable variation of value.

In the middle distance, all foliage is divided into masses of light and shadow, with the shadow rising to the mid-range. The warm greens in the light side are grayed down as the distance increases. Shadows get cooler as you go back, and detail in the shadow is greatly reduced.

In the far distance the values step back even further. Light and dark values become very close. In the last range of hills, they merge into a single tone just a shade darker than the sky color.

When painting landscapes in oil, it helps to mix batches of each of these value steps on the palette and make sure they progress evenly.

-----

There's also a double gradation going on in the sky. More on

Sky Gradations on a previous GurneyJourney postand more of this kind of stuff in my book

Color and Light: A Guide for the Realist Painter

|

Meissonier, Portrait of a Sergeant, 1874, Kunsthalle Hamburg

Height: 73 cm (28.7 in). Width: 62 cm (24.4 in). |

"What a magnificent collection of different degrees of attention: that of the portrait painter as he studies his model standing in front of him on the pavement, in his finest uniform and his finest pose,"

"that of the model intent only upon doing nothing to disturb his ultra-martial bearing, his gaze menacing, staring, fixed...

"...that of the spectators, some of them drawing near, fascinated, another who casts an amused glance at the picture as he passes by, with some sarcastic remark on his lips; another who no doubt has just been looking, and for the moment, with pipe between his teeth, is thinking of something else as he sits on a bench with his back to the wall and his legs extended in front of him."

"Meissonier rediscovered the decent folk of that period, which was not made up exclusively of mighty lords and fallen women, and of which we get, through Chardin, a glimpse on its honest, settled bourgeois side."

"Meissonier introduces us into modest interiors, with woodwork of sober gray, furniture without gilding, the homes of worthy folk, simple and substantial, who read and smoke and work, look over prints and etchings, or copy them, or chat sociably, with elbows on table, separated only by a bottle brought out from behind the faggots."

----

Jean-Louis Meissonier, 1914, free online book by Frederic Cooper

Jean-Louis Meissonier on Wikipedia

Portrait of the Sergeant on Wikipedia Commons

Today we'll continue Chapter 9: "Painting from the Life" from Harold Speed's 1924 art instruction book Oil Painting Techniques and Materials

Today we'll continue Chapter 9: "Painting from the Life" from Harold Speed's 1924 art instruction book Oil Painting Techniques and Materials .

.

I'll present Speed's main points in boldface type either verbatim or paraphrased, followed by my comments. If you want to add a comment, please use the numbered points to refer to the relevant section of the chapter.

Today we'll cover pages 164-173 of the chapter on "Painting from the Life," where he talks about Velázquez.

1. Velázquez Man with a Ruff

Notes of Speed's main points: Early Velázquez-- Simple handling of tuft of beard. A lot of searching and labor over the edges of the ruff.

V- "hasn't yet arrived at the largeness of perception." I think Speed means his tones are more choppy and modeled on a small scale rather then conceived as larger tonal unit.

2. Velázquez Portrait of young Philip IV

Speed's notes summarized: Head study. Added armor and costume later. Preoccupied with contours of tone masses, but larger effect accomplished. But still tight and "searched out."

3. Pope Innocent X

V. had been traveling in Italy studying painters there. Pope was a difficult subject; Italian painters hadn't succeeded. Painted a study first. Color richer than normal for V. Still interested in edges of tonal masses, but effect is subtler and richer and simpler. Preoccupation with overall visual impression. Very subtle touches to the corners of the eye. Many different brushes in evidence.

4. Court Buffoon (Don Juan de Austria)

Painted to please himself to experiment with new painting ideas. Simple modeling, but good knowledge of skull and structure. Keeps attention on all-embracing unity of impression. "Painted on the same scheme of working from carefully wrought middle tones up to the accents of the lights and the darks, which are the last touches put on."

|

| Velázquez Philip IV of Spain (detail) |

5. Velázquez Philip IV of Spain

Speed calls this painting the "despair of painters." V had painted the king many times before. Knew his subject. Head well planted in collar. Lack of hard definition throughout. Vertical edge of hair at left and shadow line of eyelid on right echoes vertical structure.

Speed tries to analyze the method V. used: First sitting: rubbed in the head with simple colors, thin paint, and simple tones. Next sitting scumbled with bone brown. Scumbling all over.

6. Speed's allegation that the National Gallery overcleaned the painting.

Speed says that the conservators took away some key glazes and details, and shows comparative photos to demonstrate his charge.

JG again: Velázquez was the object of extreme interest among academic painters both in France and England at the time Speed wrote his book, and Velázquez was much admired when Sargent was studying with Carolus Duran. Much of the academic theory was based on his method. Check out the book The Art of Velázquez by R. A. Stevenson, also from the time of Speed's book. It's

available free online at Archive.org.

Next week— Reynolds and beyond.

-----

----

GurneyJourney YouTube channel

My Public Facebook page

GurneyJourney on Pinterest

JamesGurney Art on Instagram

@GurneyJourney on Twitter

Today we'll continue Chapter 9: "Painting from the Life" from Harold Speed's 1924 art instruction book Oil Painting Techniques and Materials

Today we'll continue Chapter 9: "Painting from the Life" from Harold Speed's 1924 art instruction book Oil Painting Techniques and Materials .

.

I'll present Speed's main points in boldface type either verbatim or paraphrased, followed by comments of my own. If you want to add a comment, please use the numbered points to refer to the relevant section of the chapter.

Today we'll cover pages 144-157, "On Painting a Head."

1. "Before commencing, select the colors you will need and choose the fewest that will serve your purpose."This is good advice that will reduce confusion, eliminate habits of color mixing, and yield harmony in the final result.

2. Don't take the colors as they come from the tube; Mix your own colors.Also a good idea. You can create your gamut primaries, instead of using the colors as they happen to come from the tube. So here you're not mixing the particular notes of your scene, but rather you're mixing the

ingredients of your color scheme. Instead of using yellow ochre and cad yellow as separate palette colors you can mix the two, and then use that mixture as your gamut anchor. For example he recommends mixing Indian red and burnt sienna. This is what the manufacturers do, mixing pigments to get convenience colors.

3. "The paint as supplied in tubes is a little stiffer than is always comfortable to paint with, and it is as well to thin the white by mixing up some of your medium with it."I find the opposite is often a problem with modern paint. Paint often comes out of the tube too runny. In that case you can stiffen tube colors by first placing them on blotter paper (or other absorbent paper or cardboard) a few hours before you need to use them. As Speed suggests, it's good to have some "stiff white" about the consistency of butter always available on your palette for impasto-rich highlights.

4. Sequence: background, hair, forehead (middle tone), planes of lower face, eye socket, nose, highest light in forehead, etc.It might seem difficult to follow this procedure in the form of text, given that we're used to seeing videos that show the process much more clearly. But try to visualize it. This is close as we're going to get to a time machine back to the Royal Academy.

5. "In the case of a short portrait sitting...do not attempt any more complications in your tones. Keep them flat and simple at first."Put your work into refining the edges instead of refining the tones. I would say to think of the head as a roughly carved block at this stage, and rejoice that there aren't too many details to worry about.

6. "Always paint with the least amount of paint that will get the effect you want. Reserve thick paint for those occasions when you want to make a crisp touch quite separate from what it is painted into."For beginning painters there's a lot to think about when you mix a color: value, color temperature, hue, chroma, and now you've got to think about paint thickness, not to mention what brush to use, etc. As you read Speed talking about his thought process, note what considerations are foremost at each stage. Value judgments are most important at first, then edges become vitally important, then he's thinking about warm versus cool differences.

7. Carefully define the eye sockets before detailing the eye.Speed probably learned this method from watching Sargent, who was said to paint an eye in this way, like making a frying pan (eye socket) and dropping an eye into it (the egg). Later Speed says: "Remember the eye is a cavity, through which is pushed the globe of the eye, on which the eyelids are placed. The eyelids therefore partake of the spherical form, as do also the 'whites' of the eye."

8. "You should always talk to your sitters if you want to keep them alive."Many first hand sources attest to the fact that portrait painters of the past talked to their models while they painted them. This is one of the most important points that is generally missed by modern practitioners. It makes all the difference in the disposition of the face and the expression of the model. Sleepy, dull models yield sleepy, dull portraits. Talking models yield portraits that are alive. There's no getting around it. Here's a

previous blog post "Talking Models" on the topic and

another post "Speaking Likeness" on the same subject.

|

| Detail of a portrait by Velazquez |

9. The under eyelid: "I know of no part of a head that so easily shows the hand of a master as the painting of the under eyelid."To find some examples of plane breakdowns as suggested in the detailed discussion on pages 153-155, such as the "three cherries" of the lips, etc. I recommend the anatomy books by Vanderpoel, Loomis, Peck, and others.

10. "Having laid in your work with the muted middle tones, you will be able to use much purer colour in the later stages, as they will be quieted by mixing with the middle tones already there."

11. "Finish is not necessarily the addition of details, but of refinements."Try to accomplish what Speed calls oneness of impression, and look for that quality in the great portraits of Sargent, Velazquez, and Rembrandt. Accents are last, and you can think of the whole head painting as a setup for those last highlights and accents.

Next week—we'll continue with the chapter with the section beginning on 157.

-----

----

GurneyJourney YouTube channel

My Public Facebook page

GurneyJourney on Pinterest

JamesGurney Art on Instagram

@GurneyJourney on Twitter

Today marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of the German artist

Adolph Menzel.

Adolph Menzel’s drawing supplies accompanied him everywhere, whether on a short walk or a long journey. He was always prepared to draw. One of his overcoats had eight pockets, each filled with sketchbooks of different sizes. On the lower left side of his coat was an especially large pocket which held a leather case with a big sketchbook, some pencils, a couple of shading stumps, and a gum eraser.

His personal motto was “Nulla dies sine linea” (”Not a day without a line”). He drew ambidextrously, alternating between the left and the right, sometimes on the same drawing. If he was ever caught without drawing paper, he sketched on whatever was available, even a formal invitation to a court ball. Whenever he was spotted at a social event, the whispered word went abroad that “Menzel is lurking about.”

He was known to interrupt an important gathering by pulling out his sketchbook, sharpening his pencil, casting an eye around the room, and focusing on a coat, a chair, or a hand. This sometimes brought the proceedings to a halt until he finished. He preferred to draw people unawares, often catching them in unflattering moments of eating, gossiping, or dozing. Once his friend Carl Johann Arnold awoke from a nap to find the artist busily drawing his portrait. “You just woke up five minutes too early,” Menzel told him.

The above teaser excerpt is taken from an introduction that I wrote for a book on Menzel's

Drawings and Paintings

that will be coming out next year. About that, more later. But for now, There's an

exhibition at the Stiftung Stadtmuseum in Berlin to mark the occasion.

If you do a sketch today, do it in honor of Mr. Menzel. It's always good to have his ghost on your side.

----

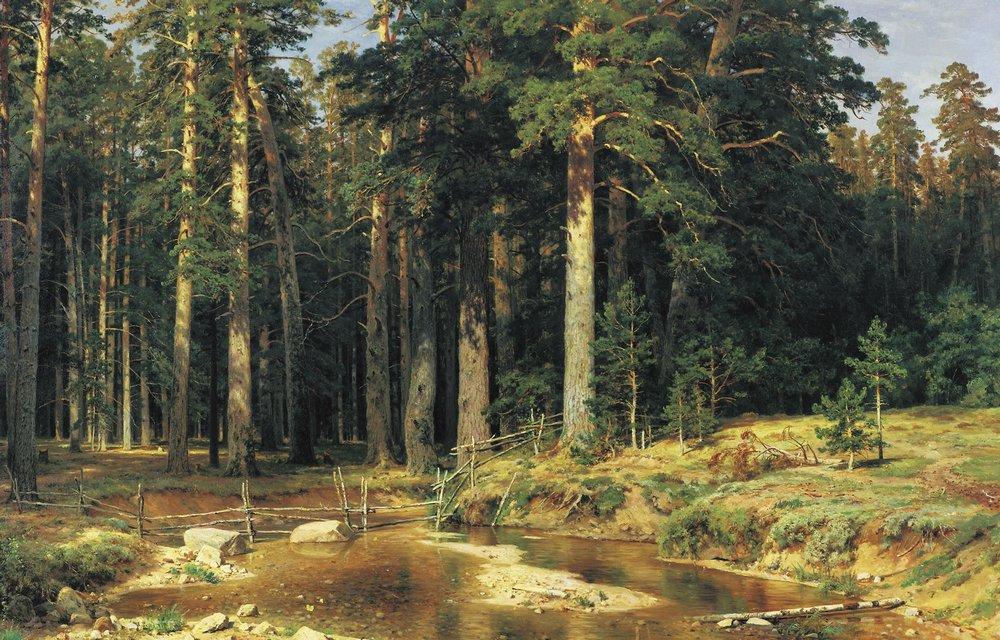

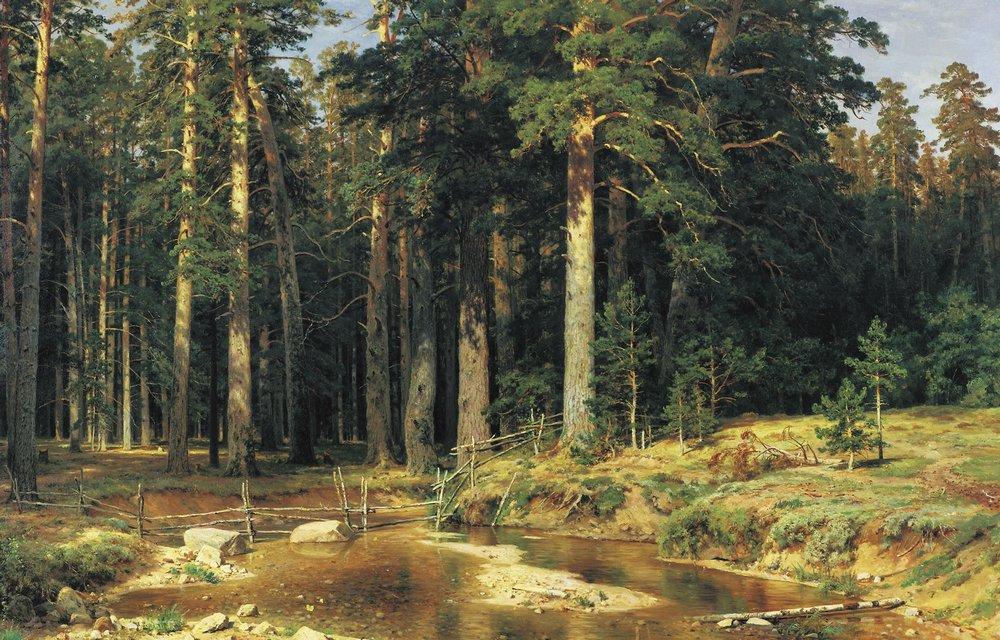

A couple of months ago we took a look at

Ivan Shishkin's opinion of photo reference in his landscape painting. Now let's examine more about his specific working methods.

Preliminary Drawings

He would advise his students: "Before starting the painting, you have to do a sketch to clarify the idea and plan what you're going to be doing on a big canvas."

Note in the sketch at left, Shishkin draws a grid, probably to help him enlarge the composition onto the canvas.

Shishkin continues: "It's also important to do a preliminary drawing [on the canvas] with charcoal. Put a layer of charcoal on a clean canvas and wipe it with a dry tissue. You'll have a smooth base tone, and you can draw over that with more charcoal. You can erase off halftones and lights using an eraser made from a chunk of black bread. If you do that you will get the effect of lighting you need, and then you're ready to continue with the final painting."

Shishkin typically used ink to clarify the outlines of the trees in his preliminary drawings. Once the preliminary drawing was finished, he would proceed to do a tonal underpainting in monochrome before painting in full color.

Paint and palette organization

"He carefully mixed organized groups of colors on his palette. All the colors must be prepared in groups in advance on the palette. He began by applying the darkest tones of paint. Then he proceeded to the halftones, and so on up to the light." (From a letter from Ivan Shishkin, St. Petersburg, 1896).

Shishkin studied in

Düsseldorf, so it's not surprising that he used primarily German paints. "He used zinc whites for big studio paintings and lead whites during his traveling and for outdoor painting, because they dry more quickly. He painted on canvases from Dresden if he could."

"He used to buy a lot of different paints. But if he didn't know the specifications of a given kind of paint, such as lightfastness and durability, he avoided it."

"Because of this he completely stopped using carmine oil paint after

[Vasily] Polenov showed him a chart of paints that was left in the sun for 10 years, and carmine completely disappeared."

|

| Ivan Shishkin and A. Guinet in the studio on the island of Valaam |

Here's a list of Shishkin's paints:

Red paints:

English red, Chinese vermilion, rose madder, and rose doré, mostly used for glazing. Burnt sienna was his favorite.

Yellows:

Yellow ocher, cadmium yellows and oranges, zinc yellow (for backgrounds and leaves in the sunlight), raw sienna, chrome yellow (rarely), and Indian yellow (for glazing). He never used gamboge or aureolin. Sometimes he used Naples yellow for sand and roots. Occasionally for foreground textures he would mix fine sand into the paints.

Blues:

Sky blue (?) and Prussian blue.

Greens:

He used a lot of different ones, including: permanent green, cobalt green, chrome green, vermilion green, emerald green, and others.

Blacks: Ivory black and lamp black oil paint.

-----

We continue the Friday Book Club with Chapter 2, "Modern Art" in Harold Speed's 1924 art instruction book The Science and Practice of Oil Painting

We continue the Friday Book Club with Chapter 2, "Modern Art" in Harold Speed's 1924 art instruction book The Science and Practice of Oil Painting .

.

Let's take Roberto's suggestion of breaking this chapter into two parts, so we'll stop at page 20. I'll present Speed's main points in boldface type either verbatim or paraphrased, followed by comments of my own. If you want to add a comment, you can use the numbered points to refer to the relevant section of the chapter.

1. "A considerable body of artists have deliberately set aside fine craftsmanship in order to express themselves more freely...there has been such a fashion for the crude methods of savages and primitive peoples."

Speed's racist comments, coming at the beginning of his book, have probably turned off a lot of readers to the useful material that comes later in his treatise on painting. That's unfortunate. But let's take a look at his views one by one and see whether there's anything that makes sense to us today.

England after World War 1 was seeing its empire rapidly eroding. Because of widespread press and travel, the doors were thrown open to an awareness of non-European cultures and art.

|

| Andre Derain, The Dance, 1905-6 |

At the same time, Modern Art, which was primarily a European phenomenon, presented a direct threat to an artist with academic skills. The fact that Speed invokes "savages" and "primitive peoples" and he shows illustrations of African carvings is not altogether surprising since some of the European Moderns around Speed were called "fauvists" (which means wild animals). He was writing not long after the scandalous premieres of such works as

The Rite of Spring by Stravinsky, which deliberately evoked primordial rituals of non-European cultures.

|

Ivory Coast, Spirit Spouse.

Wood, Ht: 18."

Baule ethnic group,

early 20th Century. |

I think most everyone nowadays would recognize that the art from non-European cultures—whether African or Pacific-Ocean or Native American — presents no threat whatsoever to traditional European academic painting. On the contrary, personally I find them hugely inspiring because of their language of abstraction.

In my mind non-Western art occupies a completely different category than Modern art does, despite the fact that many Modern artists used it as a jumping-off point. One can copy the outward style of any type of art, and that's totally fine. But if an artist doesn't know much about the culture or mind that produced that "exotic" art, it will be different from the original article.

Speed admits that some 19th century painters became overly concerned with naturalism, which he says led to "enfeeblement," so he has left the door open a bit to recognizing the value of Modernism.

Speed then proposes some sociological reasons for the rise of modernism:

2. Mass culture sets the dominant cultural note of the modern ageSpeed suggests that there's a dominant cultural note in every age, such as that set by aristocratic patrons in the 18th century, and realism in the 20th century when middle-class values were in the ascendancy.

In other words, the power that

buys the art

shapes the art.

He then chalks up the trends of what he sees as crudeness in art to the rise of the power of the middle and lower classes. He says, "a great deal of the unrest and fretful violence that is disturbing the traditions of culture in all directions is due to the coming of this new cruder element into the cultural feast."

This argument strikes me not only as elitist, but wrong. If anything, it has been the cultural elite—especially academics, critics, and investors—that have promoted and supported Modernism.

Modernism has never been terribly popular in a widespread way among the lower and middle classes, compared to the art in comic books and magazines. What has truly captured the imagination of all socioeconomic classes in the West, from poor to rich, has been the "other" modern art movements found in comics, animation, and illustration.

3. "Now nobody waits until he has developed his mind before expressing an opinion."What would he think of the Internet?

4. "The greatest works of art have been produced by small communities, such as existed in Athens and the independent states of Italy in the Renaissance." Interesting point, and perhaps it has a grain of truth to it, but I'm not sure that's always true. I believe art of great quality can appear anywhere, including in commercialized mass culture.

5. "It is only those whose work shouts at you, who have much chance of any immediate notice."Speed equates bright colors with swearing and other inflated forms of language. He raises an interesting question for our time: Can art with quiet, sober virtues find an audience in our own age of ubiquity and image overload?

Speed observes that as Modernism began to emerge, artists were interested in the exotic. He says, "Whistler, Aubrey Beardsley, Conder, and the exquisite decadent art of the

fin de siècle was the fashionable note. This has been followed by the craze for Cézanne, Van Gogh, Matisse, and Picasso."

He predicted that people would grow bored with such novelties. But history has proven otherwise, at least in the realm of the auction market and the museums. What may have surprised Speed were he to visit us today is how polymorphous the art world is. Whatever stuff you like, you'll find someone doing it.

6. "anaemic people painted life-size drinking the blood of freshly killed bullocks"Speed makes reference to a specific painting at the (French?) Salon. Anyone know what painting he's referring to?

7. "I am not at all sure that the columns of literature it has produced, are not of much greater value than the works of which they are supposed to treat."This is reminiscent of the point of Tom Wolfe's book

The Painted Word ,

, which argued that modern paintings serve primarily as illustrations of ideas that have their real life in print, and that the cart is driving the horse.

Tip to young artists: give critics and historians something to write about.

8. Quotes from Roger Fry on page 16 and 17.Roger Fry was an interesting character in all this, a promoter of Post-Impressionism and a detractor of Sargent. Rather than try to explain him further, here's the

Wikipedia page on him.

9. "The great influence the Press has on modern life has brought into existence a new variety of artist, one who ministers to the demands of art critics."There were publications cropping up everywhere in Speed's day which acted as tastemakers and gatekeepers. With those publications, Speed argues, comes a professional class of art critics who never existed before. He suggests that "the art-critics have strengthened their position recently by the control they have been able to exercise upon the purchasing departments of our public galleries."

Food for discussion:

a) There are still art critics in newspapers and magazines, but do they have the cultural influence they once did?

b) Has social media made art critics irrelevant?

c) What kind of artworks or artists are being fostered by the proliferation of forums like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Blogger?

10. "Good craftsmanship is a healthier soil for art to grow in than fine theories about aesthetics."This is a fascinating point, that art is the finest flower growing on a base of craftsmanship running through all of a culture's production. Can there be fine painting without a corresponding value placed on fine furniture and architecture and wallpaper and typography? This idea is reminiscent of William Morris, who believed that all things in a person's world should be conceived artistically.

We'll cover the second half, starting at "Technical Influences," next week.

-----

|

| Adolph Menzel The Balcony Room, oil, 1845 |

Adolph Menzel was painting from life in oil many years before the Impressionists. His friend Paul Meyerheim described his way of working: “Especially in the time where the whole world was painting out of that brown soup, it was Menzel's characteristic to put every tone correctly mixed and thickly into the right place."

Meyerheim continues: "He never performed the method of glazing. He always painted differently than his contemporaries and as a result the world wasn't familiar with his technique."

"He compared glazing or similar transitions with transparent colors to the use of the pedal on the piano, stating that a good pianist can play everything as if he was using the pedal. Yet as a matter of fact everything has to be played on the keys themselves without the tones getting blurred.”

-----

Thanks to

Christian Schlierkamp and

Christoph Heuer for help with the translation.

From

Paul Meyerheim

Gouache is an effective medium for portraits. Here are some examples by Valentin Serov (1865-1911) to serve as inspiration.

|

| Portrait of Henrietta Girshman. 1904. Gouache on cardboard. 100.8 × 70 cm. Tretyakov Gallery |

Gouache lends itself to exploratory studies, allowing you to try out a composition quickly and efficiently. The board chosen can be a light brown, approximately equal to the dark halftone of the model's skin. Skin tones can be modeled with gossamer layers above and below that base tone.

Gouache can also be handled as a finished medium in its own right. This 1909 portrait of Yelena Oliv is 37 x 26 inches, and combines gouache, watercolor, and pastel on cardboard.

|

| Portrait of Alexei Morozov. 1909. Gouache and pastel on cardboard. 37 x 23.5 in. |

Serov loved water media and drawing media because they lend themselves to simplification, to finding the essence of a sitter. In his later years, Serov was obsessed with the purest expression of line and shape, not for caricature, but for truthful, simple character.

According to a recent article in the

Tretyakov Gallery Magazine, he also used tracing-paper to help find the essential statement: "Having drawn a figure on a semi-transparent sheet, he would put another such sheet over the drawing and, having traced the best lines, continue to draw on this new base."

Starting at age 9, Serov was a student of the great Russian portrait painter Ilya Repin. He also studied in Paris, where gouache was quite popular.

According to Igor Grabar, "Serov believed that the artist ought to be adept in every available medium because nature itself is infinitely diverse and inimitable, just as the artist's mood and feelings differ from one day to another: today he wants to work in one way, tomorrow in another."

"For this reason he worked with oil paint, watercolours, gouache, tempera, pastel and coloured hard pencils, recommending his students to follow suit."

An exhibition of the work of Valentin Serov, in honor of the 150th anniversary of his birth, is

currently on view at the Tretyakov Gallery through January 17, 2016. The show takes up three floors of the museum, with extensive areas devoted to watercolors and drawings.

I've been reading about 19th century Russian painting, and several books on the topic have mentioned that the artists were influenced by an 1853 essay called "The Aesthetic Relations of Art to Reality" by Nicolas Chernyshevsky.

By all accounts this essay was a kind of manifesto for the Russian painters and was a particularly significant influence on its leaders, such as Ilya Repin, Ivan Shishkin and Kramskoy. It explains why realism flourished longer there than it did in Western Europe.

|

| Ivan Shishkin, Mast Tree Grove, 1898 |

For example, compare this painting by Shishkin in Russia in 1898....

|

| Paul Cezanne, The Bathers, 1898-1905 |

...to this one by Paul Cezanne in France at the same time. What was different about the aesthetic philosophy in Russia?

The central notion of Chernyshevsky's essay is that reality is greater than art. At best, art is an attempt to replicate or reproduce reality, and therefore art is on a plane lower than reality.

This is a very different idea from the aestheticism of J.M.W. Whistler and others who suggested that it is the business of art to improve on nature.

Whistler said, "

Nature is very rarely right, to such an extent, even that it might almost be said that Nature is usually wrong."

Around the same time that Chernyshevsky's influential essay was published in Russia, related ideas were published in England and America. John Ruskin's

Modern Painters and Asher B. Durand's

Letters on Landscape Painting (1855) preached a version of Truth to Nature that had a great influence on the movements Pre-Raphaelitism and the Hudson River School in English speaking countries. The main difference with Chernyshevsky is that he seems to lack the moralizing tone of Durand and Ruskin.

|

| Ilya Repin, Portrait of Aleksei Pisemsky. 1880 |

All these thinkers advocated that the artist should have a reverence for the concrete facts of reality and to allow as much as possible for the painting to be a clear window to that reality. Repin's portrait of Pisemsky is a good example, where the technique is subordinated to the force of personality, made manifest in concrete facts.

Ruskin, Durand, and Chernyshevsky all advocated that artists—students especially— paint as faithfully from nature as possible, but since absolute leaf-for-leaf imitation of external details is impossible, artists should re-create (Durand used the word "represent") on canvas the truth they have experienced, penetrating to the Platonic essence.

In Shishkin's case this meant painting scenes that seemed "found" or "photographic" to the untrained eye, but were in fact carefully constructed using his deep knowledge of natural effects and avoiding picturesque conventionalism.

Many contemporary realists place a great value on the aesthetics of brushwork, paint texture, and composition, but Chernyshevsky would have regarded this preoccupation as a foolish distraction, like focusing on the scratches and skips on a phonograph record instead of listening to the music. Just as a phonograph record aspires to deliver the experience of a live concert, a painting aspires to the fullness and presence of reality.

Here are some excerpts of Chernyshevsky:

- A reproduction must as far as possible preserve the essence of the thing reproduced; therefore, a work of art must contain as little of the abstract as possible.

- Art expresses an idea not through abstract concepts, but through a living, individual fact.

- The essential purpose of art is to reproduce what is of interest to man in real life.

- Reality stands higher than dreams.

In order to grapple with these ideas, I imagined a conversation between myself and Chernyshevsky.

Me: Can a camera or a high resolution motion picture achieve this result?

Cherny: No. The excitement that the human being experiences in the presence of reality can only be evoked by an artist with an inquiring mind who can imaginatively see into the structure and essential features of the subject, and express what it is about that subject that makes it interesting.

Me: Is the imitation of reality what we're after?Cherny: No, the mere copying of external features will only lead to boredom, both for the artist and the viewer. There's a big difference between mindless copying and insightful reproduction of nature.

Me: Aren't such insights highly subjective? Science in recent decades has shown that there is no such thing as objective reality. Our perception of the world around us is a construct of our perceptual systems. Therefore, shouldn't we paint the world in a personal style that matches our own subjective view of the world?

Cherny: You make too much of that. Painting in the way you suggest is just an excuse for laziness. Two careful artists with good training will produce studies that match each other very closely. But such studies are just the beginning. It takes a lifetime to create works that address the deep experiences of life.

Me: What about the Surrealist's goal of painting what is inside the mind, the world of dreams and nightmares?

Cherny: Your dreams ultimately come from reality. Imagination plays a key role, but the aim of the artist is to use the imagination to see into the heart of reality itself, which is the source of everything in its fullest and purest form. Reality is also full of latent mystery that cannot be fully understood by either the poetic avenue of art or the fact-based avenue of science.

Me: If reality is greater than art, of what value is a visit to the art museum?

Cherny: If it's a choice between the two, artists should look to reality for their chief inspiration; otherwise their work will become second-hand and mannered. But it is extremely valuable to study the means by which great artists of the past have expressed the essence of reality. Look for artwork that brings you closest to the feeling that you are in the presence of real life, and then try to understand how those effects are achieved. The challenge when you leave the art museum is to leave behind the conventions of past art movements, and to see reality for yourself without preconceptions.

Me: What categories of art are most worthy—sublime, comic, tragic, or beautiful?

They are all important. A sensitive person will respond to the problems presented by life, and will want to create art that speaks to those problems, so that a fellow human can gain wisdom and insight from the art. Those impulses can run the gamut of emotions. Whatever way you respond to nature should be the subject of your art, but it should be conveyed in concrete, material terms.

My concluding thoughts: I don't think Chernyshevsky's idea is completely tenable intellectually for me. I can't get past the idea that "reality" is a provisional thing, constructed in our own minds, and subject to the whims of our very selective and subjective visual systems. I also resist the notion that abstraction must always be avoided. Of course I love the Russian realists, but I also feel that a pulsing sense of life can emerge from certain highly abstracted forms of art, such as hand-drawn animation or comic art.

But Cherny's idea that reality stands on a plane above art is for me an extremely useful driving concept that helps focus my mind when I'm out painting from nature. I often achieve my best results when I try to capture what's in front of me without trying to "improve" on it in any way. When I compare the immense complexity, subtlety, and richness of the real world to my own paltry efforts, I'm left with a sense of how far I have fallen short of the truth in front of me.

-----

"

The Aesthetic Relations of Art to Reality" by Nicolas Chernyshevsky.

Nicolas Chernyshevsky on Wikipedia

Recommended book:

The Russian Vision: The Art of Ilya Repin

by David Jackson

The revival of academic drawing and painting in America and Europe has largely been guided by the republication of the book by

Charles Bargue and Jean-Léon Gérôme.

But there are other ways of approaching the teaching of academic drawing, most notably the Russian tradition, which has more of a focus on spirit and construction, rather than the outward appearance of the form. I discussed some of the differences between the two approaches in an earlier post

when I interviewed Professor Sergey Chubirko

who teaches at the Russian Academy in Florence.

For those interested in Russian academic methods, there are two recent books by a living Russian master named Vladimir Mogilevtsev. He is the head of the Drawing Department of the

Russian Academy of Arts (also known as the Repin Institute) in St. Petersburg.

Mr. Mogilevtsev's primary books are

Fundamentals of Drawing

(first published in 2007) and

Fundamentals of Painting

(2012). They were published in Russian, but they have been translated into English, and I've had a chance to read through a PDF version of the English edition, alongside the Russian print editions.

I was interested in the drawings, of course, but even more interested in the thinking behind the drawings, and these books provide an excellent window into the mind of the Russian academy.

The way the book is organized is that there's a step by step sequence that plays out on the right hand page. On the left hand page is a commentary, along with examples by masters of the past, often including Russian artists such as Repin, Serov and Fechin.

In both the drawing and painting books, Mr. Mogilevtsev places great emphasis on beginning with a strong concept of the subject, analyzing what feeling the subject evokes in the artist, and thinking how best that can be expressed.

He also analyzes the form into its blocky forms, the skeletal foundation, and the individual muscles beneath the skin. The examples from old master drawings, sculptures, and paintings clarify his observations, and deepen the appreciation of the way our predecessors solved similar problems.

Fundamentals of Painting

follows a similar structure, with extended step-by-step demos, beginning with a head portrait, a half-figure portrait with hands, a standing nude and a copy of a Rembrandt.

The quotes from the text are refreshing:

"Sometimes students complain that they don't like a scene. This is a sign of laziness and limitation of an artist's imagination. There is a person, and a person is the whole world. Revealing this world is a huge task for any artist."

|

| Sketches and finished portrait by Valentin Serov |

There's a lot of emphasis on planning with sketches to capture the quality of the subject that attracted the artist, and in maintaining that perception throughout the arduous process. The text emphasizes seeing the whole, contrasting warm and cool, and establishing a hierarchy of details, with not all details being equal.

In their print form,

Fundamentals of Drawing

and

Fundamentals of Painting

are available from Amazon, but the print copies are currently only in Russian. They're big books (13 3/4" x 9 3/4"), and the quality of the reproductions is outstandingly good. Currently, if you buy them in this form, they will send you the PDF of the English translation. The English translation is also excellent. I'm told the English print editions are soon to come, and I'll update this post when they become available.

I have also been told by the publisher that the drawing book is in the process of being translated into French, Italian, Spanish and Turkish languages. They also already have a Chinese translation a Finnish version.

I also highly recommend

Academic Drawings and Sketches (Fundamentals Teaching Aids) (shown at left). Instead of showing a couple of drawings taken through a long series of stages, this is a large collection of finished examples of Russian academic figure drawings. They're mostly nudes, drawn by the instructors and students over the last 25 years.

It also includes some more informal sketchbook drawings of fellow students and landscapes.

This book is mostly pictures, with high quality reproductions. It has minimal text at the beginning, an introduction by Vladimir Mogilevtsev in both Russian and English. The captions in this book are in both Russian and English.

Academic Drawings and Sketches is 168 pages, softcover, 9.5" x 13.5".

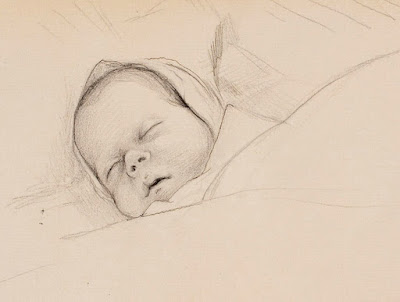

The Finnish National Art Gallery has released online the sketchbooks of Albert Edelfelt (1854-1905).

Since the 104 sketchbooks are in chronological order, you can trace the journey of his mind and see the people he met and the moments he lived.

The books begin in his youth and reflect his early exposure to academic drawing at the Drawing School of the Finnish Art Society. He also studied with

Adolf von Becker and later with

Jean-Léon Gérôme at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts in

Paris (1874-1878).

There are babies newly born and relatives on their death bed, both common subjects of 19th century artists.

Edelfelt had a special gift for painting children. His sketchbooks reflect unselfconscious moments of children's lives, such as musical evenings, and kids at play.

Here's one of his finished paintings of children, for which he is justly revered not only in Finland, but around the world.

Don't miss his copies of Sargent in #19, dissections ub #22, studies at the Prado in #27, and testing out a watercolor set in #100 (above).

-----

Thanks to the

Finnish National Gallery for making these works accessible to the public, and thanks to Finnish illustrator

Ossi Hiekkala (check out his work) for letting me know about it.

|

| John Singer Sargent, Ambrogio Raffele, 1904 |

An exhibition of John Singer Sargent's portraits of artists friends has opened at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and will be on view through October 4.

-----

Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends

In Ye Good Old Days, artists formed social events called "Sketch Clubs." The purpose of these social groups was conversation, smoking, music, conversation, comic speeches, and imaginative picture-making.

There were similar men-only sketch clubs in New York and Philadelphia, both of which are still active today, though perhaps with different agendas. Membership in the

London Sketch Club included newspaper illustrators and cartoonists like

Cecil Aldin and

Phil May, profiled earlier on the blog.

Howard Pyle had a similar

sketch club for his students, a stag evening with ginger ale, beer, food, and a sketch competition. The winning sketch received the drawing that Mr. Pyle did that evening.

The sketching activity wasn't focused on observational sketching, such as the plein-air practice or urban sketching we think of today, but rather pen-and-ink or pencil sketches of assigned topics.

Pamphlets from the Slade School of Art in London describe how to enter artwork in each month's competition. Sketches would be submitted on or before the first Monday of the month, and they must be marked with the member's number on the lower left-hand corner with no other indication of the artist's name. Monetary prizes were awarded.

Each month, the Slade Sketch Club assigned subjects in five categories. Here are some examples of topics:

Special Figure: (Pluto carrying off Prosperine, Rape of Europa, Atalanta's Race)

Figure: (A Ball Room, The Music Lesson, A Family Group, Reconciliation)

Animal: (The Chase, Milking Time, At the Zoo, Danger, A Market)

Landscape: (Windy Day, Winter, River Scene, A Ruin, Seascape with Stormy Sky)

Modelling (Sculpture): (Door Knocker, Clasp, Letter-Box, Lectern)

The idea is still good—though maybe we can invite the ladies and forgo the smoking. There's no substitute for hanging out in a clubhouse with other kinds of artists—painters, cartoonists, illustrators, animators—and drawing from the imagination just for fun, in a low-risk setting. When I was an art student, we had similar gatherings at the

Golden Palms Apartment. Sometime I'll have to show you the "E.T. Sketchbook"�wacky drawings of "rejected concept sketches for E.T." by Thomas Kinkade, Paul Chadwick, Syd Mead, and others.

W.M.R. French, Director of the Art Institute of Chicago, wrote about the importance of imaginative sketching in the context of a complete artist's education. "From the beginning," he said, "a student should practice composition or picture-making, even in a rude way, in the classes of illustration and composition. Memory drawing should be stimulated by the assignment of subjects for illustration in which the student relies upon material accumulated in his studies elsewhere. He should learn to present a given subject in agreeable form with regard to line, arrangement, and balance of light-and-shade. This study gradually develops until it eventuates in a completed picture."

-----

Howard Pyle's Sketch Club on the Howard Pyle blog

London Sketch Club's current website

Slade Archive Project, which is archiving ephemera

Previous related posts:

Cecil Aldin,

Phil May,

Drawn Together,

Golden PalmQuote by Mr. French from

Art Education in America by W. M. R. French, "Brush and Pencil" Vol. 8, No. 4 (Jul., 1901), pp. 197-206

|

| Sir Edwin Landseer, Study of a Lion, 1862, oil, 914 x 1378 mm, Tate |

British animal painter

Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) developed remarkable skills of speed and dexterity.

According to one

one account, "It was Landseer's custom to place a clean canvas, or panel, upon his easel and leave it there untouched for several days, or until he had completely thought out the subject that he was to paint. This done, he would take up his palette and brushes and set to work, and in an astonishingly short space of time the picture would be finished."

There are many stories of him painting large oil studies of animals in less than an hour. He painted the portrait of the spaniel and the wounded rabbit in two-and-a-half hours.

One houseguest recalled leaving for church on a Sunday morning as Landseer set a blank canvas on his easel. Landseer skipped church that day, and when the guest returned from the service, the painting was finished.

Another story of his prodigious ability comes from a dinner party in London. A lady remarked that it would be impossible for someone to draw two things at once. "Oh, I can do that," Landseer said quietly; "give me two pencils and I will show you."

Landseer took a pencil in each hand, and then "drew simultaneously and unhesitatingly the profile of a stag's antlered head with one hand, and with the other the perfect outline of the head of a horse. Both drawings were strong and vigorous; that drawn with the left hand in no way inferior to its companion sketch."

-----

Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) was a self-taught and independent-minded Anglo-Welsh painter, etcher and muralist who was also a mentor for Dean Cornwell.

"We must never forget that the great artists of the past were, first and foremost, honest, capable craftsmen, who worked to the order of various patrons and clients. Isn't it nonsense to talk, as the 'highbrows' do, of 'prostituting your art' when you work for a businessman? Obviously you only prostitute Art when you do it badly. As to selling your work, it is quite immaterial whether your client is a king, a bishop or a soap-boiler, as long as your work is really worthy of you.

"There should be a lot more commonsense in Art, and less affectation; and perhaps the worst affectation is this nonsense about 'vulgarising' Art by associating it with commerce. I want to see it used a great deal more, not only for Commerce, but for

Life. I want it to be more useful and comforting to the people. What is Art, if it is not a message that everybody can understand?

"Did Rubens, or Titian, or Rembrandt mystify the public or sneer at them? They did not. Did they set themselves on pedestals—or pose—or paint down to the public level? They did not. The public is quite ready for the finest Art that any living artist can offer. And we shall certainly get more commonsense into Advertising when the Artist and the Businessman are better friends."

-------

Quote is from

Phil May: The Artist and His Wit

by David Cuppleditch

Website sampling from Brangwyn's Art

|

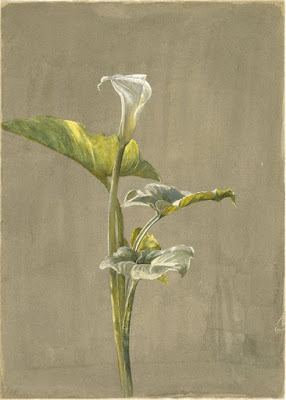

| Fidelity Bridges, Milkweeds, 1876. Watercolor and gouache on paper |

Fidelia Bridges (1834 - 1923) was known for her meticulous botanical studies, many of which were painted outdoors in nature.

Both of her parents died when she was in her teens. She never married, but had a small circle of friends, including Mark Twain, for whom she served for a time as a governess of his daughters.

She lived by herself in a home in Canaan, Connecticut, overlooking a stream and a flower garden filled with birds and butterflies. A writer of the time described her this way:

"She soon became a familiar village figure, tall, elegant, beautiful even in her sixties, her hair swept back, her attire always formal, even when sketching in the fields or riding her bicycle through town. Her life was quiet and un-ostentatious, her friends unmarried ladies of refinement and of literary and artistic task who she joined for woodland picnics and afternoon teas."

|

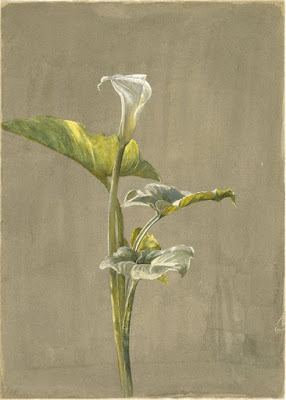

| Fidelia Bridges, Calla Lily, 1875 |

She was inspired by reading John Ruskin's Modern Painters, which preached truth to nature. She found her way to study under William Trost Richards, who became a lifelong mentor. Her early studies in watercolor and gouache, such as this one of a calla lily, show a patient and observant eye.

Bridges was one of only seven women who became members of the American Watercolor Society in the 19th century. She worked for the Prang company in her later career, and her work was often reproduced on greeting cards.

-----

Late in his life, academic painter and teacher

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) wrote a statement of his beliefs about art.

"The fact is that truth is the one thing truly good and beautiful; and, to render it effectively, the surest means are those of mathematical accuracy. Nature alone is audacious above anything human; she alone is original and picturesque. It is, then, to her that we must become attached if we wish to interest and enthuse the spectator."

|

| Illustration by Howard Pyle |

"The art of illustration has made progress. It is more documentary, but none the less artistic. From this point of view the Americans excel. They have learned how to make use of the document and to make it serve their purpose. In this, instantaneous photography has been of inestimable assistance…. From all this one must conclude that our sense of sight is not as well developed as that of the Greeks or of the Japanese, and that it is not one of our gifts to observe with sufficient attention the various aspects of nature when in rapid motion."

"When one is young and inexperienced one prefers the art of sentiment, and has even the false idea that too much study, too much truth, take away from work its light and its movement. When one has grown old in the harness, when one has worked for many years, observed well, compared well, ideas change. The artist should be a poet in conception, a determined, honest, and sincere workman in the execution. One must put into his work an artistic probity, and, above all, work, work. But there can be no serious and durable work if it is not based upon reason and mathematical accuracy.—if, in a word, art is not allied to science."

|

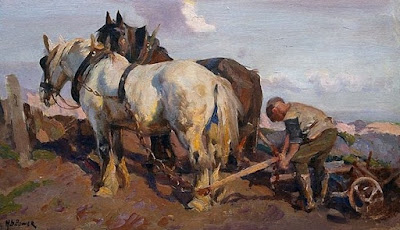

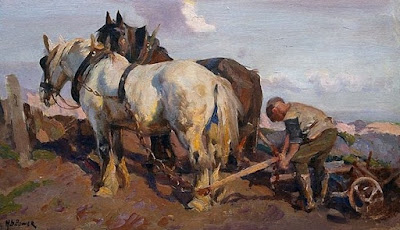

| Septimus Power, The End of the Day |

H. Septimus Power (1877-1951) was a New-Zealand-born Australian artist who was always fascinated with horses.

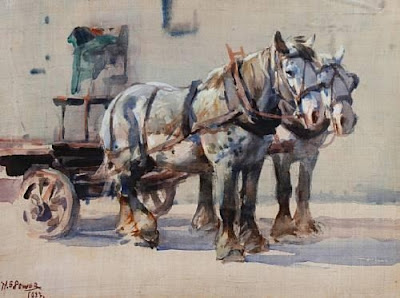

|

| H. Septimus Power, Horse Cart, Watercolor |

He got an early job painting animal heads on butchers' delivery vans, and later worked for a veterinarian.

He studied at the

Académie Julian in Paris and then moved to London, exhibiting at the Royal Academy.

Arthur Streeton said of him: "One is impressed first by a tremendous display of colour and a dauntless feeling of optimism … He displays remarkable knowledge and vigour in his paintings of animals."

|

| H. Septimus Power, Bringing Up the Guns |

In World War I he worked as a war artist, specializing in scenes with horses. The biplane is almost a ghost in the distance.

----

The landscapes of Ivan Shishkin (Russian, 1832-1898) are notable for their truth to nature. He knew a lot about botany and painted outdoors on a regular basis. This autumn landscape in oil is about 16 x 26 inches.

A detail suggests three things to my eye.

1. The sky must have been dry or nearly dry from a previous session, rather than painted all wet together. If it was previously painted, it then have been "oiled out" with a very thin layer of painting medium to make it receptive.

2. He must have had a wide variety of brushes, and switched between them as he built up the foliage and branch textures. A big old, splayed brush, dabbed against the canvas, could have provided the foliage textures.

3. The branches are painted with a very thin round brush, and some of the lighter branches in the lower right of this detail seem to be scraped out of the wet paint with a knife or a brush.

4. The foreground leaf masses are laid on quite thickly. The full effect is loose and direct, but not "brushy"�that is, it doesn't look like a collection of brushstrokes.

-----

The Shishkin painting is

Lot #1 in an upcoming Sotheby's sale of Russian pictures in London on June 2.

One of the masters of gouache painting was the French academician Jehan Georges Vibert (1840-1902). All the paintings in this post are in watercolor / gouache.

|

| Jehan Georges Vibert The Ant and the Grasshopper, 1875 |

Vibert had a special gift for storytelling. Here he interprets the classic folktale of the wanton "grasshopper" falling on hard times and asking for a handout from the industrious "ant." Notice the heavily laden pack animals, the broken shoe of the troubadour, and the dismissive gesture of the monk.

|

Jehan Georges Vibert Peeping Roofers

|

Roofers pause from their work to peep inside a building. The figures are carefully studied from models who were probably real roofers.

|

Jehan Georges Vibert Spanish Saddlemaker

|

He traveled to Spain and took inspiration for many of his paintings from there. The careful drawing is reminiscent of Meissonier or Gérôme.

|

Jehan Georges Vibert Cardinal Reading a Letter

|

Vibert is best known for his gently mocking paintings of cardinals. This one seems to be reading a love letter; the one below is reading some baudy bit from Rabelais.

|

Jehan Georges Vibert Reading Rabelais

|

It is deliciously ironic that one of the largest collections of his work was given by the Maytag heiress to a seminary (the

St. John Vianney seminary in Florida).

|

Jehan Georges Vibert On the Ramparts

|

Vibert was equally comfortable with historical and costume pictures. As a playwright and dramatist, he had access to a large supply of costumes. I'm not sure exactly what period this depicts, but I'm guessing 17th century Holland, around the time of the Tulip Wars?

|

Jehan Georges Vibert Trial of Pierrot

|

The Art Institute of Chicago owns this painting of "The Trial of Pierrot," but it's not on display. The original gouache is about 18 x 24 inches.

He also painted it in oil. The painting is based on a farce about spurned lovers, and Vibert peoples it with characters from the

commedia dell'arte. The paint appears to be fairly thin and transparent in the outer areas, but built up in opaques in the faces.

|

| Jehan Georges Vibert |

Vibert also had a love of the fantastic and bizarre. Note the pet tarantula and the rider of the bat-winged creature.

|

Jehan Georges Vibert At the Breakfast Table

|

Wikipedia on

Jehan Georges VibertArticle on Vibert in the Aldine

There's a double page spread of Vibert's

Gulliver in my book:

Imaginative Realism: How to Paint What Doesn't Exist

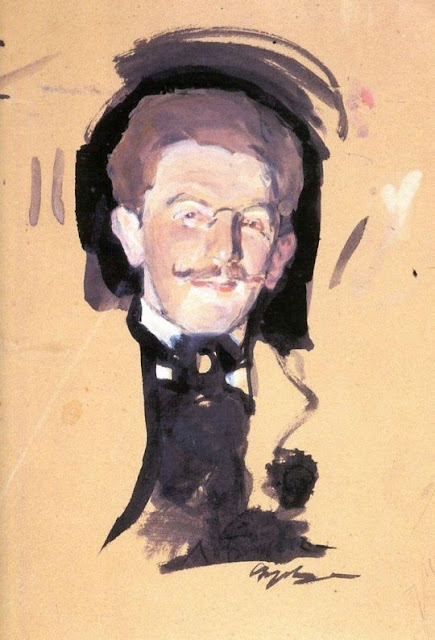

A scandal about a displeased portrait client damaged the career of the most famous painter of his day,

Ernest Meissonier (French 1815-1891), and ended with the portrait thrown onto a fire.

|

| Ernest Meissonier, Self Portrait |

Despite his celebrity and the vast sums paid for his work, Meissonier had painted few images of women, and few portrait likenesses. This commission came in the last decade of his life and at the pinnacle of his international success.

The sitter was Mrs. J. W. Mackay, of California. After seeing the portrait nearly finished, she rejected it, and at first her husband refused to pay for it. The price was vast for 1884, estimated between ten and twenty-five thousand dollars. Meissonier responded by vowing to keep the painting and he put it on exhibition, where the public would be the judge.

In his view he had simply painted a picture that was too accurate. In her view he had made her look coarse, and made up like a painted doll.

"It seems that after Meissonier had painted the portrait, Mrs. Mackay criticised it a little and wanted it just a little more finished. It was not finished then when she went into the country, and she wrote him she would come up anytime he wanted to finish it."

"He never said a word, but finished the hands from a model of a big, coarse woman with ugly hands, and made the cheeks and lips powdered and painted frightfully, and left the neck yellow, just because he was so angry that she should dare to criticise such a great master as himself."

"Now Mrs. Mackay thought, with good reason I think, that she ought to have been the model to her own portrait, and that she could ask at least for a faint resemblance, especially as she would have to pay $15,000 for the picture."

"Without informing Mrs. Mackay as to his intentions or asking her consent, he simply sent the picture to the exhibition, where her friends saw it and told her of it. She wrote and asked for the picture, and at the close of the exhibition it was sent to her, with a bill."

"Mr. Mackay was so provoked that he wanted to make a fuss about it, but his friends persuaded him to pay it and say nothing more about it. This he did, and threw the picture in the fire. But on the same day Mr. Mackay left for America the papers: came out with the story, abusing Mrs. Mackay, and the French artists are to meet and have an indignation meeting that a canvas immortalized by Meissonier should be burned by a vulgar American."

The debate about who was in the right was taken up in all the papers on both sides of the Atlantic. An early writer

about the incident said that "Meissonier, by the haughtiness of his manner, his artistic independence, and, most of all, by his unpardonable success, had been sowing dragons teeth for half a century. And now armed enemies sprang up, and sided with the woman from California. They made it an international episode: less excuses have involved nations in war in days agone....The tide of Meissonier's prosperity began to ebb: prospective buyers kept away; those who had given commissions canceled them."

Sources:

View Next 25 Posts

.jpg)