The question is not whether

Red Dawn is a good movie. It is a bad movie. As the crazed ghost of

Louis Althusser might say, it has always already been a bad movie. The question is: What kind of bad movie is it?

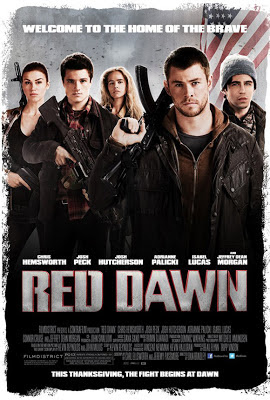

(Aside: The question I have received most frequently when I've told people I went to see

Red Dawn was actually: "Does Chris Hemsworth take off his shirt?" The answer, I'm sorry to say, is no. All of the characters remain pretty scrupulously clothed through the film. The movie's rated PG-13, a designation

significant to its predecessor, so all it can do is show a lot of carnage, not carnality. May I suggest

Google Images?)

My companion and I found

Red Dawn to be an entertaining bad movie. I feel no shame in admitting that the film entertained me; I'm against, in principal, the concept of "guilty pleasures" and am not much interested in shaming anybody for what are superficial, even autonomic, joys. (That doesn't mean we can't examine our joys and pleasures.) No generally-well-intentioned, "diversity"-loving, pinko commie bourgeois armchair lefty like me can go into a movie like

Red Dawn and expect to see a nuanced study of geopolitics. I knew what I was in for. I got what I expected: a right-wing action-adventure movie based on a

yellow peril premise.

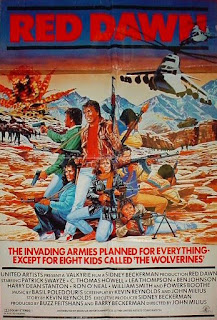

Red Dawn is an unironic remake of a

1984 movie predicated on paranoid right-wing fantasies; it's not aspiring to even the most basic

Starship Troopers-levels of intertextuality and metacommentary. There's none of the winking at the audiences that fills so many other 1980s remakes and homages (e.g.

Expendables 2, which relies on the audience's knowledge of its stars' greatest hits — the only convincing performance in the movie is that of Jean-Claude van Damme, who, apparently overjoyed to be released from the purgatory of straight-to-DVD movies, plays it all for real, and becomes the only element of any interest in the whole thing). The closest

Red Dawn comes to acknowledging its position in the cinemasphere happens when it turns the first film's very serious male-bonding moment of drinking deer blood into a practical joke, giving the characters a few rare laughs.

What are we supposed to feel good about in this movie? The 1984

Red Dawn was not even remotely a feel-good movie, but it gave us a space in which to feel proud of an idea of America that could survive even the most devastating attack by the Soviet Union (and its Latin American minions). It made a point of showing concrete objective correlatives for the abstract idea that is "American freedom" — the one that was most impressed on me by my father when we first watched

Red Dawn together was the scene where Soviet soldiers talk about going to a gun shop to collect the federal

Form 4473s, and using them to track down gun owners. This, to my father and many other people, demonstrated exactly why even the most minimal type of registration of guns is not merely annoying, but a threat to freedom. I vividly remember

my father saying, "If the Russians come, we burn those damn forms."

Red Dawn was not merely an action movie; it was a documentary.

But

Red Dawn was a movie made during a time when the U.S. was not officially at war. It appeared in U.S. theatres less than a year after the

invasion of Grenada, and just at the time when the actions that would eventually become the

Iran-Contra Scandal were making their way into the public consciousness. The hawks of the Reagan administration needed the public to be both patriotic and fearful of the Red Menace, because otherwise it was difficult to justify the massive transfer of wealth into the Pentagon.

Red Dawn did that better than any other movie of the time. (For much more on this background, see the article by J. Hoberman in the Nov/Dec 2012 issue of

Film Comment.)

Now, though? The new

Red Dawn comes as the Iraq war is winding down and the war in Afghanistan (our

longest) may be nearing some sort of end. (And then, of course, there's

Libya.) But these have been wars where we have been invaders fighting insurgents. They have been long, unfocused wars with no clear victory conditions. They began with some popularity and unanimity of public opinion, but the longer they went on, and the more that people learned about them, the less popular they became. They continued because the U.S. military is, while a huge part of the national budget, not a particularly concrete and visible part of everyday life and concern for many Americans. Without the threat of a draft, and with the rise of long-distance and drone strikes, most Americans can ignore the immediate reality of American wars, the hundreds of thousands of deaths and injuries on every side.

It's in what the new

Red Dawn makes us attach our feelings of pride, joy, and power to that it really differs from its predecessor, because the idea of America that it presents is neither particularly clear nor the product of much conviction. There are flags and some general genuflecting in the direction of "freedom", but the original

Red Dawn offered a vision of how its idea of "freedom" actually works in the world, and what threatens it. There was an attempt at creating a certain amount of plausibility and verisimilitude — one of the advisors to the original film was

Alexander Haig, Reagan's former Secretary of State, who worked with writer/director

John Milius to craft what seemed to them a relatively realistic invasion scenario, the weapons and vehicles were as realistic as could be accomplished without being able to buy actually Soviet weaponry (the CIA inquired about the tanks after seeing them being moved to the set; later, the Pentagon used images of them to train the guidance systems in spy planes), and the tone is dark, with war presented as hell for both sides. Milius made numerous references to his masculine hero Theodore Roosevelt, and the vision he presented was stark, painful, and apocalyptic, more

Hobbesian than

Amurrican. It was

Panic in Year Zero! by way of

The Battle of Algiers.Ours is the Age of the Tea Party, not the Age of Reagan, and so the new

Red Dawn is closer to the ideological vision of

The Patriot than that of its original source.

The Patriot is the story of a man in Colonial America who doesn't see much point in fighting against the British until his own family is affected, at which time he becomes a psychopathic vengeance machine, and then at the end returns home to a small community not to help build up a new government or create the idea of a common United States, but to become the leader of a little utopian plantation. (He had already been leader of a utopian plantation before the war, because the black people doing work on his property were not actually slaves, but free employees. Really. As William Ross St. George, Jr. wrote in his

review (PDF) of the film for the

Journal of American History, this must have been "the only such labor arrangement in colonial South Carolina".) What matters in

The Patriot is not country or government — all government is portrayed with contempt in the film — but rather self-reliance and, especially, family. Despite the movie's title, it's not about being a patriot, but about being a loyal, strong, independent, and avenging father.

The new

Red Dawn, much more than the original, is also a movie about families and fathers. Jed, played originally by Patrick Swayze and in the new film by Thor, is now an Iraq vet who struggled to be a good son to his father and, especially, a good brother to Matt (originally Charlie Sheen, now Josh Peck). Lots of family melodrama is alluded to. The boys don't visit their father in a re-education camp; instead, the Evil Korean Guy (whose name I thought was Captain Joe, but IMDB tells me it's Captain Cho. I prefer my version), who for some unfathomable reason recognizes from the very first moment that Teenagers Are The Enemy (he was probably a high school teacher back home), rounds up their fathers, brings them to the Evil Dead Cabin where the kids had been hiding out, and makes the fathers plead with the kids to come in. Of course, the weak and collaborating mayor pleads with them to give themselves up, but the strong and noble father of Jedmatt (in a much blander performance than the clearly unhinged and perhaps psychopathic man portrayed by Harry Dean Stanton in the original) instead tells them to fight to the death, causing Captain Joe to channel his inner

Nguyen Ngoc Loan and shoot him in the head. Oh dad, poor dad. Jed and Matt then go on to learn how to be good brothers to each other, just in time for— Well, you don't want to know the ending, do you? (For a moment, I thought it would turn out to be a movie climaxing with brotherly kisses and fellatio, but, alas, it did not. Well, not exactly. Although the more I think about it...)

We have to talk about the ending, though, because we have to talk about who lives and who dies. The original

Red Dawn was not

Rambo — while it certainly stirred up feelings of patriotism against the Soviet enemy, and admiration for the U.S. military, its tone isn't all that far away from

The Day After. The end is a downer, but it's not nihilistic. We zoom in on a memorial plaque, its words read to us on the soundtrack: "In the early days of World War III, guerrillas, mostly children, placed the names of their lost upon this rock. They fought here alone and gave up their lives, 'so that this nation shall not perish from the earth.'" The memorial asserts that these lives were lost for a great cause, and by quoting the Gettysburg Address, it connects their sacrifice to that of soldiers who fought to preserve not just some idea of Americanism, but the union itself.

The remake turns patriotic tragedy into personal tragedy — Jed is killed just at the moment when he has reconciled with his brother. Toni (

Adrianne Palicki in the remake,

Jennifer Grey in the original) and Matt both survive in this version, along with many of the other Wolverines. Well, the white Wolverines.

The new

Red Dawn isn't just a yellow peril movie, it's a vision of white supremacy. Only one nonwhite Wolverine has much of an identity (Daryl, played by

Connor Cruise), and the others die pretty quickly. Finally, Daryl is, without his knowledge, injected with some sort of tracking device that can't be removed from his body, so he's given some supplies and left to wander away, probably to be killed by the North Koreans. Almost all of the white Wolverines survive, presumably with a new understanding of the miraculous powers of their skin color.

Remember what happened to (white) Daryl in 1984? His sleazy father (the mayor) forced him to swallow a tracking device. He knew it was in him. After barely surviving the assault that followed, the Wolverines take him to the top of a freezing mesa with a captured Russian soldier and get ready to execute him. Jed and Matt fight about it, with Matt saying it will make them worse than the Russians. Jed kills the Soviet soldier, but doesn't seem to be able to kill Daryl. Robert, whose experiences have fully brutalized him, shoots Daryl. It's a wrenching, disturbing scene. Again and again, the original

Red Dawn says: War is a horrific, destructive experience for everyone involved, and it reduces us to our most animalistic natures — naming the guerrillas

Wolverines was not merely the naming of a mascot or a rallying cry, it was a statement of what they had become.

The new

Red Dawn doesn't hurt. It's superficially entertaining in a way that the original is not. Sure, it's shocking that Jed dies, but the way that scene is set up and edited highlights the shock, not the pain. In the original

Red Dawn, Jed and Matt know they're heading out on a suicide mission. Jed survives a little while longer only because the Cuban Colonel Bella (

Ron O'Neal) feels some respect or sympathy for him and is tired of the whole war. Jed1984 kills the Super Nasty Russian Bad Guy, just as Jed2012 kills Capt. Joe (with his father's gun, because they just happen to be in Dad's Police Station!), but the original film then takes the brothers to a frozen park, where, mortally wounded, they sit together on a bench and drift off to eternity.

The new

Red Dawn instead puts its concluding weight on the idea that you probably shouldn't trust the black guy, even if he's friendly and well-intentioned. He's probably got a tracking device in his blood. Even though he doesn't want to be, he's a traitor. Best to leave him in the wilderness. This in a movie that begins with a montage showing us that President Obama and his minions are ineffective at defending us from the North Koreans (and their secret Russian puppetmasters).

The original

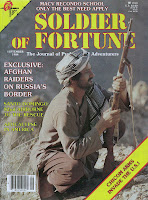

Red Dawn had an unabashed political purpose — it warned us not to let our guard down, it encouraged us to support massive increases in defense spending, it encouraged us to stockpile guns and canned goods. It especially wanted us to call our congresspeople and tell them to support funding for the Contras and similar anti-communist forces. The September 1984 issue of

Soldier of Fortune magazine includes an article about

Red Dawn's production, particularly its weaponry, that begins: "Military strategists have often discussed the repercussions of a communist takeover of Central America. One worst-case scenario has the Soviet Union training Cubans and Nicaraguans in the offensive use of advanced weapons such as the MiG 25 and T-72 tank." The article ends:

Red Dawn seriously attempts realism. Milius spent $17 million trying to give the American public a taste of what Soviet weaponry, tactics and occupation practices are all about.

Liberal critics will howl about Reagan's deleterious effect on the creative arts and scream that Red Dawn is unabashed saber-rattling propaganda. It sounds like our kind of movie.

Red Dawn opens across the country on 17 August.

So yes,

Red Dawn was propaganda in 1984. But it was not

merely propaganda; there is cleverness and even humanity to it. It's an action/survival movie, so character development isn't a particular goal, but where it spends it moments of character development are telling. Instead of just building of family melodrama, the original

Red Dawn gave humanity to some of the antagonists (particularly Colonel Bella). While the Soviet commanders are cartoons, the Russian soldiers are clearly just as trapped in the horrific logic of war as the Wolverines.

The new

Red Dawn also wants to be propaganda, as the opening montage shows us. But there are more subtle connections to not just right-wing militarism, but extremist nuttiness. The key is three letters: EMP.

How do the bad guys invade North America? They wipe out the American defense infrastructure, and apparently the entire American military, by setting off at least one

electromagnetic pulse (EMP). Now, EMPs are real. Boeing is even

developing an EMP missile. But who gets really excited at the idea of an EMP knocking out electronic infrastructures? The apocalypse addicts at

WorldNet Daily. Famed doomsayer Newt Gingrich

brought it up during the Republican primary. Right-wingers get positively giddy at the idea.

Why? Because it

justifies lots of spending on missile defense. But

according to the right wingers, President Obama is not spending nearly enough money to defend us from missiles. We could be wiped out at any moment by an EMP. But the weak, appeasing black guy in the White House is, whether he knows it or not, a traitor.

The politics of the new

Red Dawn are about as coherent as those at a Tea Party rally, where really the only unifying theme is hatred of anything that can be called "government" (and doesn't contribute to the life and happiness of the complainer), hatred of the Socialist Kenyan Muslim Manchurian President Nazi Obama, and love of weaponry.

Whatever can be said about John Milius, at least he was committed enough to his concept to have thought it through. The new

Red Dawn seemingly unintentionally opens itself to all sorts of odd moments, such as when Jed says, "When I was overseas [in Iraq], we were the good guys, we enforced order. Well, now we're the bad guys. We create chaos." In 1984, when the Wolverines went into the desert on horses, they evoked images of the

Mujahideen in Afghanistan. (The cover of that September 1984 issue of shows a guerrilla and the headline "Exclusive: Afghan Raiders on Russia's Border".) In 2012, when a character talks about the order enforced in Iraq, it's hard not to think about all the insurgents created by the chaos of the American invasion. When the Wolverines are called "terrorists" by their enemies, who doesn't think of the War on Terror? No wonder the U.S military has been disappeared by the new

Red Dawn (instead of being assisted by active duty soldiers, the Wolverines are assisted by

retired Marines). Nobody can forget that the U.S. military of the 21st century is an invading force. In 1984, the U.S. wanted to arm and train the "freedom fighters" of the world. In 2012, insurgents and terrorists "hate our freedoms".

In the nearly thirty years between the two films, gender roles seem to have become more confining. There weren't many women in the original

Red Dawn, but Toni and Erica (

Lea Thompson) in the original were interesting, active characters. They were stereotypically, tragically traumatized by something that happened with the Russians (likely, rape), so much so that their grandfather hides them in the cellar, but though they remain traumatized and quiet, they also assert themselves against the assumptions of the men, and (like the women in

Battle of Algiers) prove to be excellent, committed guerrillas, and more resilient than many of the men. When she dies, Toni makes sure she takes at least one Russian with her. The women of the original

Red Dawn do not end up as objects of our pity or our lust, but rather of our respect.

Toni and Erica both survive in the new

Red Dawn, but that's about all they have going for them. Erica is a sharp-cheeked blonde (

Isabel Lucas) whose entire job in the movie is to be gawked at and pined for — Matt is so in love with her that he repeatedly risks the safety of the Wolverines to save her. (Girls are dangerous! They make boys stupid!) Once her role as the Imperiled Love Interest is over, she mostly disappears from the movie. Toni exists primarily to help Jed get in touch with his emotions. Her costumes tend to highlight her figure (the opposite of the costumes in the original film), and though she gets to shoot stuff and blow things up like everybody else, there's little sense of her as an integral member of the unit.

One of the problems for the new film is that it doesn't really know what to do with its characters. The mayor is set up to be just as sleazy and appeasing as the original, but nothing much is made of his story. He's just another weak, naive black guy. But that's what happens when you allow black people into government, as we should have learned from

Birth of a Nation. While the original

Red Dawn ended by invoking Abraham Lincoln, the new

Red Dawn conjures the glory days of the John Birch Society.

But I'll end where I began: It is entertaining while it lasts. There's lots of action, lots of explosions. Some of the action is badly filmed — a car chase in the beginning is particularly incoherent, much to its detriment, because though part of the point of this action is to get us excited for our protagonists in peril, it also has some information to convey, and it can't do it because it's so badly shot and edited. There is moment-to-moment excitement. But though I went into the film determined to give it the benefit of the doubt, soon the entertainment was at least partially because of the film's idiocies. It's breathtakingly racist, but I also found it difficult to be disturbed by its racism, because it was so obviously stupid that it was comic, and my companion and I kept nudging each about the blatant, self-parodying silliness.

However,

as Twitter showed, plenty of people found the movie inspiring, convincing, and powerful. Its political message got through. Its racism buttressed the inherent racism of many people who went to see it during its opening week. Its ideology did some work in the world.

Thinking about that fact is very far from entertaining.

The law is based on reasoned analysis, devoid of ideological biases or unconscious influences. Judges frame their decisions as straightforward applications of an established set of legal doctrines, principles, and mandates to a given set of facts. Or so we think.

As the Supreme Court debates President Barack Obama’s landmark health care law — sometimes dubbed ObamaCare — it’s important to remember that unreasoned, impartial law is largely an illusion. As far back as 1881, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. wrote that “the felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow-men, have a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed.”

We sat down with Director of the Project on Law and Mind Sciences at Harvard Law School (PLMS) and editor of Ideology, Psychology, and Law, Professor Jon Hanson, to discuss the interaction of psychology and the law, and how they form ideologies by which we all must live.

What sparked your interest in the study of mind sciences and the law?

My interest has evolved through several stages. Although I studied economics in college, I did so with special interest in health care policy, where the life-and-death decisions have little in common with the consumption choices imagined in neoclassical economics. Purchasing an appendectomy through insurance has little in common with buying a fruit at the market.

After college, I spent a year studying the provision of neonatal intensive care in Britain’s National Health Service, attending weekly rounds with neonatologists at London hospitals, meeting with pediatricians in rural English hospitals, interviewing nurses who were providing daily care for the infants, some of whom were not viable, and speaking with parents about the profound challenges they were confronting. Those experiences strengthened my doubts regarding the real-world relevance of basic economic models for certain types of decisions.

In law school, I studied law and economics, but tended to focus on informational problems and externalities that had been given short shrift by some legal economists at the time. After attending a talk by, and then meeting with, the late Amos Tversky, I became an early fan of the nascent behavioral economics movement.

It wasn’t, however, until I spent a couple of years immersed in cigarette-industry documents in the early and mid 1990s that I felt the need to make a clean break from the law’s implied psychological models and to turn the mind sciences for a more realistic alternative.

What was it about the cigarette documents that had that effect?

Well, they made clear that the tobacco industry articulated two views of their consumers – an inaccurate public portrayal, and a more accurate private view.

The first, which the industry conveyed to their consumers and to lawmakers, was of smokers who are independent, rational, and deliberate. Smokers smoke cigarettes because they choose to, because smoking makes them happier, even considering the risks. The industry thus gave consumers a flattering view of themselves as autonomous, liberated actors while assuring would-be regulators that there was no need to be concerned about the harmful consequences of smoking. Smokers were, after all, just getting what they wanted.

The second view of the consumer, which was evident in the industry’s internal documents, was of consumers as irrational, malleable, and manipulable. The industry’s confidential marketing strategy documents, for instance, made clear that the manufacturers theorized and experimented to discover how to target, persuade, lure, and chemically hook young consumers to take up and maintain the smoking habit. That internal understanding of consumers had no

By Ervin Staub

In difficult times people need a vision of a better future to give them hope. The U.S. is experiencing difficult times. The majority of people are poorer and many are out of work, the political system is frozen and corrupted by lobbyists and institutions that have gone awry, and there are constant changes in the world that create uncertainty. We are also at war, and face the danger of attack. While pluralism – the openness and public space to express varied ideas, and for all groups in society to have access to the public domain – is important for a free society, the cacophony of shrill voices creates confusion and makes it difficult for constructive visions and policies to emerge.

In times like these, subgroups of a society – racial, ethnic, religious or political – often turn against other groups. Members of one group, often the largest or dominant group, blame others for the difficulties of life. Often, their ideology is destructive. Instead of addressing the source of societal problems, such visions frequently focus on enhanced national power, racial superiority, or a utopian degree of social equality in the society or in the world. They identify enemies that supposedly stand in the way of the fulfillment of the vision. The group turns against and engages in increasingly harmful, and eventually violent, actions against this enemy.

In response to intensely difficult conditions, destructive ideologies and movements have shaped life in many nations. In Germany the ideology stressed racial superiority, expansion, and submission to a leader. Jews and gypsies were regarded as racially inferior, Slavs both inferior and in the way of expansion. In Cambodia the vision was of total social equality, with everyone judged incapable of contributing to or living in such a society, whether the former elite, educated people or minorities as enemies. In the former Yugoslavia, for the Serbs, it was renewed nationalism, with other groups, especially Muslims in Bosnia and Kosovo as enemies. In Argentina, people stood against communism and in defense of faith and order. Everyone considered left-leaning – even people working to improve the lives of poor people – became enemies. In Rwanda “Hutu power” over the Tutsi minority, became the guiding ideology. While significant societal change is usually shaped by a number of influences, such ideologies had important roles in creating hostility and violence, ending in mass killing or genocide.

In the U.S. so far, in spite of our increasingly dysfunctional political life and shrill political rhetoric, there is no comparable destructive ideology. While we have many divisions, and ignore the harm to civilians outside the country in the wars we fight, the rights of different groups inside the country have increasingly come to be respected, especially in the last half century. However, many have turned against the current administration, and to some extent, against government in general. They affirm core American values of freedom and individuality, but in the service of tearing down, without a vision of what to create. This is one half of an ideology, the against part, without a clear aim, a for part.

Such rebellion seems to be supported, and perhaps instigated, by people in the background who finance it, and by politicized media. It thrives on people’s genuine and understandable distress, the result of the frustration of material needs, but even more, the frustration of a variety of psychological needs, uncertainty, and fear. Joining ideological groups and movements helps fulfill needs for security, community, and a feeling of effectiveness at a time when people feel powerless.

We need a constructive vision, words joined

Elvin Lim is Assistant Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. In the article below he looks at health-care reform. See Lim’s previous OUPblogs here.

Ideological purists do not believe in reconciliation. Conservatives would rather rely on private acts of kindness than the state to deliver health-care services. Hence their characterization of bureaucrats as cold and remorseless (such as when they’re on “death panels”). Liberals, for their part, believe that it is heinous to make a patient in need of care wait for private charity. Hence their tremendous faith in the helping hand of the state. For the conservatives, the market is benign but the state is monstrous; for liberals, the state is virtuous and the market is immoral.

Partisans and political parties, on the other hand, must reconcile themselves to median voters and therefore to each other if they are to have any chance of survival. That is why in their discussion of health-care reform, most Republicans and Democrats have ceded fundamental tenets of their ideology. In their concurrence with the Republicans in addressing a social issue in cost-cutting and job-creating terms and in eschewing a single-payer system, Democrats have proven that they are not really socialist. In reminding seniors of the potential cuts to Medicare should the Democrats try to cover the uninsured, Republicans have shown that they are not pure laissez faire anti-statists either.

It is in this muddied ideological context that we should view the parliamentary measure called Reconciliation which Democrats are bracing to deploy in the weeks to come to pass health-care reform. Reconciliation may be procedurally draconian because it bypasses the Senate filibuster, but it crystallizes the idea shared by Congressional leaders who pushed through the Budget and Impoundment Control Act in 1974 that legislative output (sound or unsound, one might add) is more important than consensus. It is no wonder that Reconciliation has often been used to pass legislation on the divisive issues in American politics which typically straddle the state/market-solution divide. These include health insurance portability (COBRA, 1985), expanded Medicaid eligibility (1987), welfare reform (1996), the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP, 1997), and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF, 2005). Perhaps the Democrats could have saved themselves a year of trying to make history and a lot of political capital if they had realized that almost every welfare and health-care bill passed in the last three decades was achieved via Reconciliation.

Although Republicans say it is the nuclear option, no real destruction followed after each of the 22 times the measure has been used (with two-thirds of the time by Republicans.) Reconciliation doesn’t only reconcile items on the federal budget, but its supporters on either side of the aisle (when it suits them) also believe that the measure also reconciles the Founders’ sometimes contradictory commitment to deliberation and debate and their desire for legislative output and government. Reconciliation has been used before, and it will likely be used again, rather soon.

By: Rebecca,

on 8/18/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Anti-Federalists,

Federalists,

tea-party,

Anti Federalists,

Law,

Politics,

Current Events,

American History,

A-Featured,

Barack Obama,

Obama,

Barack,

tea party,

health care,

conservative,

reform,

liberal,

partisanship,

ideology,

health-care reform,

birthers,

Add a tag

Elvin Lim is Assistant Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and  author of The Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. In the article below he looks at the health-care debate. See his previous OUPblogs here.

author of The Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. In the article below he looks at the health-care debate. See his previous OUPblogs here.

As America goes into intensive partisan-battling mode this summer over health-care reform, it may be helpful for President Barack Obama and his advisers to sit back and understand the basis of the rage against their plan. An understanding of the resurrected ghosts of Anti-Federalism in today’s conservative movement may offer him some strategies for bringing the Republicans and Blue-Dog Democrats back to the discussion table.

The rage that is out there among conservatives may seem excessive and irrational to liberals, but it is based on an ancient American quarrel. The differences between the “Birthers” and angry town-hallers and Obama precede the Democratic and Republican parties; they precede the Progressive, the Whig, and the Jeffersonian-Republican Party. They were there from the beginning. For the biggest fault-line in American politics was also the first political debate Americans ever had between themselves. It was the debate between the Federalists and the Anti-federalists about the need for a consolidated federal government with expanded responsibilities.

In 1787 and 1788, Anti-Federalists hurled charges of despotism and tyranny against those who proposed the need for a stronger federal government with expanded responsibilities than was envisioned in the Articles of Confederation. Today, the analogous charges against the neo-Federalist Obama are of fascism and socialism. As Federalists reviled the Anti-federalists for their shameless populism, Obama has likened the angry protests staged by his health-care opponents as mob-like thuggery. Conservatives, in turn, have recoiled at liberal condescension; just as Anti-Federalists fulminated against the Federalist aristocracy.

The Anti-Federalists envisioned a small republic because they could not conceive of their representatives - sent far away into a distant capital and surrounded by the temptations of a metropole - would ably be able to represent their communities. The fear of the beltway and of faceless, remorseless bureaucrats directing the lives and livelihood of honest workers and farmers struck fear into the heart of every true republican (lowercase is advised), as it does the modern conservative. Death-panels weren’t the first Anti-Federalist conspiracy theory.

Today’s “birthers” and “enemies list” conspiracy theories are not new stories in themselves other than the fact that they reveal the visceral distrust conservatives have of Barack Obama, just as many Anti-Federalists turned (Jeffersonian) Republicans accused Alexander Hamilton of illicit connections with the mother country, England. Today’s “Tea Parties” are but the modern conservative articulation that they are, like the Anti-Federalists were, the true bearers of the “spirit of ‘76.’”

As Cecilia Kenyon observed decades ago, the Anti-Federalists were “men of little faith.” This characterization is both accurate and one-sided at the same time, so it is no surprise that contemporary Democrats have taken the same line of attack, calling Republicans the “party of ‘No.’” The Anti-Federalists, like today’s conservatives, cannot bring themselves to trust the federal government or Barack Obama. Conservatives are using “scare tactics” because they are scared.

But their fears are not entirely unfounded and certainly not illegitimate, because a measure of distrust of government is the first defense against tyranny and the first implement of liberty. Liberals who have been so quick to trust the federal government should not only have a look at Medicare and Social Security, but acknowledge the mere fact that with one half of the country unconvinced (legitimately or not), the country’s faith in its government has been and will almost always be a house divided. This is a given fact of a federal republic; it is the blessed curse that is America. That is why in all areas in which there is concurrent federal and state responsibility - such as in education and immigration policy - lines of authority and execution are invariably confused and American lags behind almost every other industrialized country. In areas in which federal prerogative is clear and settled - that is to say in areas in which the federal government acts like any other non-federal, centralized government in the world - such as in foreign policy, the president can typically act very quickly (if not too quickly).

The conservative grassroots movement (staged or not) is a real threat to Obama’s health-care plan. But if the movement doth protest too much, it should ironically also be a source of comfort to the president. That there is so much anxiety and push back suggests that conservatives feel genuinely threatened. With Democratic control of all branches of government (and the open possibility of passing the health-care bill via the reconciliation process which will only need a simple majority in the Senate), conservatives believe that the liberals can transform their America into something their parents and grandparents would no longer recognize.

Here then, is the lesson to be learned. If the president wants to get anything done - he must strike at the heart of the problem: it is one of a fundamental, thorough-going(dis)trust. Barack Obama must convince Republican and Blue-Dog dissenters that he is one of them. Bowing before foreign Sultans and mouthing off about racial profiling did not endear him to conservatives, who only want to feel assured that the president is for them, not against them. These are minor gestures, which is why it won’t be tremendously costly for the president to present them as a peace offering. And calling protesters to his health-care plan a “mob” is definitely not a peace offering. It invokes the very perception of condescension the Anti-Federalists felt in 1787, reinforcing the ancient and original “us” versus “them.” To unite the county, he must transcend not only party, but ideology, and history itself. Barack Obama must break the legacy and transcend the language of our 222-year-old, bimodal politics. Quite simply, he must convince conservatives that he too can feel, and talk, and protest, and hurt, and fear, and agitate like a latter-day Anti-Federalist; and he is no less intelligent, no less rational, no less compassionate, no less constructive, and certainly no less American for trying to do so.

I love this logic: "to govern them as a distinct people was impossible, because they were as brave and as high spirited as they were fierce, and were ready to repel by arms every attempt on their independence." So you don't like being pushed around and dare to resist and fight back? Well, now, that just shows how very, very much we need to push you around.

Well said, Perry -- and more than a little hideously ironic, given how the United States moved from colony to nation.

Melissa Thompson's 2001 article in Lion & Unicorn, In a Sea of Good Intentions, is a good resource for anyone who wants to follow up on what Debbie has pointed out here about legal "literature" (including the writings of John Marshall) and children's lit.

Besides, even if these depictions of the Indian people had been accurate, it still doesn't provide a moral excuse - let alone an imperative - for taking their land. (One of my neighbours owns a big garden which he is allowing to disappear under weeds. He isn't using his garden 'well' by a gardener's standards, but that doesn't give the local gardening club the right to take it over.)