new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: free online novel, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 108

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: free online novel in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Eds. note: This graphic novel--like many in the genre--can be used with a wide range of ages, from students in middle grade, on up to college.

Comics! Graphic novels! Are you reading them? You should be! They're outstanding... for what you can learn about!

Years ago, I learned about the Code Talkers. I don't recall when or how, but I knew about them. With each year, a growing number of Americans are learning about who they were, and their role in WWI and WWII.

A few years ago, I started reading about comic books--written by Native people--about Code Talkers. Then, I got a couple of those comic books and was deeply moved by what I read.

The two that I read (described below) are in Volume One of Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers. Given the popularity of graphic novels, Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers is an excellent way for teens to learn about the Code Talkers--from people who are Native.

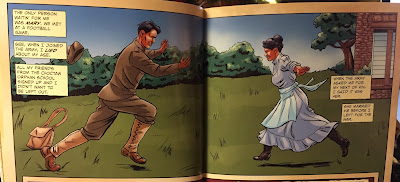

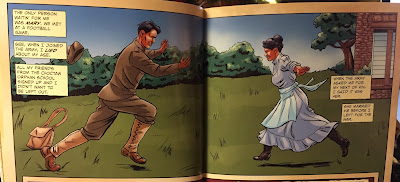

Back in June of 2014, I wrote about Arigon Starr's Annumpa Luma--Code Talkers about Choctaw code talkers from WWI. It was a stand-alone, then, and is now one of the many stories in Volume One. An image from Annumpa Luma stayed with me. Here it is:

|

| From Annumpa Luma by Arigon Starr |

That page warms my heart. So many of my relatives were--and are--in the service. They are people whose ancestors fought to protect their families and homelands. The code talkers, like soldiers everywhere, were/are... husbands. Wives. Parents. Children... on homelands, or, carrying those homelands in their hearts.

That seemingly obvious fact is brought forth in the stories in

Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers. In the prologue--

Homeplace--we read the words of Lee Francis III. He

founded Wordcraft Circle in 1992 to promote the work of Native writers and storytellers. He passed away in 2003. Where, I wondered, was

Homeplace first published? After poking around a bit, I found it in his son's doctoral dissertation. That son, Lee Francis IV, founded Native Realities Press.

Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers is published by that press. Knowing all this gives this collection depth and a quality that is hard to put into words. It is something to do with family, community, nation, conflict, commitment, perseverance... shimmering, with love.

~~~~~

After

Homeplace, is Roy Boney's

We Speak in Secret, which

I read/reviewed as a stand-alone in December of 2014 and Arigon Starr's

Anuuma Luma.

They're followed by several others that expand what we know. Did you know, for example, that Native women were in those wars? That may seem obvious, too, but one story in

Tales of the Mighty Code Talker focuses on a Native woman.

Code: Love by Lee Francis IV is about Sheila, a Kiowa woman who is a nurse. A soldier is brought to the field hospital where she's working. His eyes are bandaged. She's walking past and hears him call out for tohn. She approaches his bed, but a guard stops her because that soldier is "some sort of radio man. Command wants him under guard." Sheila's mind goes back home--to Anadarko, Oklahoma--as she remembers a boyfriend who enlisted in the war. This injured soldier, we understand, is a Native man speaking his language, and thinking of his own home. Of course, Sheila figures out a way to get him some water.

Each story in Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers is memorable.

I highly recommend it to teachers, everywhere.

Libraries ought to get several copies.

The closing pages include a lesson plan, a history of the Code Talkers, a bibliography, and biographies of the writers whose work is in the book. Here's the cover, and the Table of Contents:

- Forward, by Geary Hobson

- Publisher's Note, by Lee Francis IV

- Prologue, written by Lee Francis III; artwork by Arigon Starr

- We Speak in Secret, written and illustrated by Roy Boney, Jr.

- Annumpa Luma: Code Talker, written and illustrated by Arigon Starr

- Code: Love, written by Lee Francis IV; illustrated by Arigon Starr

- PFC Joe, written and illustrated by Jonathan Nelson; Additional colors and letters by Arigon Starr

- Mission: Alaska, written and illustrated by Johnnie Diacon; Colors and letters by Arigon Starr

- Trade Secrets, Pencils and Inks by Theo Tso; Story, color, and letters by Arigon Starr

- Korean War Caddo, original story concept by Michael Sheyahshe; Story, art, color and letters by Arigon Starr

- Epilogue, illustrated by Renee Nejo; written by Arigon Starr

- The History of the Code Talkers, by Lee Francis IV

- Coding Stories, by Lee Francis IV, illustrated by Weshoyot Alvitre

- Bibliography

- Editor's Note

- Biographies

~~~~~

Native America Calling's segment

on December 14 was all about

Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers. One of the early callers was a Tlingit man, calling in from Alaska, to say that there were Tlingit code talkers, too. In response to his call, Arigon Starr said that his story is precisely why

Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers is subtitled "Volume One."

There's more to know. I look forward to Volume Two. In the meantime,

get several copies of Volume One, directly, from Native Realities Press.

Marcie Rendon's "Worry and Wonder" is a short story in Sky Blue Water: Great Stories for Young Readers, edited by Jay D. Peterson and Collette A. Morgan. Here's a screen cap of the cover and a partial listing of the Table of Contents:

Published in 2016 by the University of Minnesota Press, Worry and Wonder is one of those stories where a character is going to be with me for a long time. I could call Worry and Wonder a story about the Indian Child Welfare Act--or, "ick waa waa." That's what Amy is calling it when the story opens. She's a seventh grader, sitting in her social studies class, doodling "ick waa waa" on her notebook as her teacher talks about the environment, and the importance of water.

Amy's thinking back to the day before, when she'd been in court and the judge said she'd have to wait another three months before going to live with her dad. Amy's "ick waa waa" and images she draws by those words capture her frustration with ICWA. In those three months, however, she spends more and more time with her dad.

Are you wondering about ICWA? In the story, Amy's dad tells her about it:

He explained that ICWA stood for the Indian Child Welfare Act. He told her how in the 1950s and 1960s Indian children were taken from their families and placed with white families. How those children had grown up and fought to have federal legislation passed so that Indian kids, if they needed to be placed in foster care, would be placed with Indian families, like the home Amy was in, and how it was federal law, tribal law, that the courts and the tribes had to try and find immediate family for children to be reunited with, which is why the courts had found him and told him to come home to raise Amy.

Some of you know that ICWA was in the news in 2016. Five years ago, a Choctaw child was placed with a white foster home in California. Since then, her Choctaw father had been trying to get her back, but the white family had been fighting to keep her. In the end, her father prevailed. In March, when child services went to pick up the six-year-old child, the home was surrounded by media and protestors who thought the white family ought to be able to keep her. That family turned the case into a media frenzy, with one major news source after another

misrepresenting ICWA, tribal sovereignty, and tribal citizenship. Right around then, I read Emily Henry's

The Love That Split the World. In it, a white couple finds a work-around to ICWA and adopts a Native infant. That character's Native identity is central to that story, which draws heavily from a wide range of unattributed an detribalized Native stories that guide that character. As you may surmise, I do not recommend Henry's novel.

The case of the Choctaw child and Emily Henry's young adult novel were in my head as I started reading Rendon's story of Amy.

Rendon--who is White Earth Anishinabe--gives us a story that doesn't misrepresent ICWA or Native identity, or nationhood. My heart ached for Amy as I read, and it soared, too. Rendon's story is infused with Native content. Some, like the water ceremony, are explicit. That part of the story is sure to tug on the heart strings of those who are following the

Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's fight to protect their water from Big Oil. There are other things in the story, too, that Native readers will discern.

Rendon's Worry and Wonder

is filled with mirrors for Native readers.

From start to finish, Rendon's short story is deeply touching. I highly recommend it and look forward to more from her. In my not-yet read pile is

Murder on the Red River, due out in 2017 from Cinco Puntos Press. It may be one of the books I'll recommend as a crossover (marketed to adults, but one that teens will enjoy).

Above I showed you a partial listing of the Table of Contents. I've yet to read Anne Ursu's story, but I look forward to it. Her character, Oscar, in

The Real Boy is like Amy. In my heart. Get a copy of

Sky Blue Water.

If you follow Native news, you know that suicide rates in our communities are high. Here's a table from a 2015 report by the Center for Disease Control:

That is data for the U.S. If you do an internet search, you'll find news stories about youth suicides in Canada.

Richard Van Camp's

Spirit is--as he said in a tweet in September of 2016--a suicide prevention comic book.

It opens with a mom, shucking corn. Nearby, a baby is sleeping. That baby's spirit rises from its body, and flies out the window, and over several pages, we see the baby fly over a Native community of kids and elders. She flies to a house where, inside, a young man in tears is reaching for pills. He looks up, surprised to see her, and drops the pills, and holds her to him. On the next page, we see people gathered round a table, praying. The door opens, and in walks the young man. They call out "Surprise!" together. They're having a feast for him, because they know he's having a rough time. His grandfather gives him some snowshoes and talks about going to their cabin. His grandmother tells him a story about his birth.

His Native family and community, in short, have gathered to help him. With its Native content, it is a powerful message about Native community. While it is crucial that teachers and librarians have books like

Spirit in their collections, it is also important to remember that--unless you've got training to work with someone who is contemplating suicide--you may not be the right person to help.

Spirit is published by the

South Slave Divisional Education Council, which serves several First Nations communities. It is available in several different First Nations languages. I've written to Richard to ask where people can buy it. As soon as I hear back, I'll add that information, here.

Regular readers of American Indians in Children's Literature know that I emphasize several points when reviewing children's or young adult books, especially:

- Is the book by a Native author or illustrator?

- Does the book, in some way, include something to tell readers that we are sovereign nations?

- Is the book tribally specific, and is the tribally specific information accurate?

- Is it set in the present day? If it is historical in structure, does it use present tense verbs that tell readers the Native peoples being depicted are part of today's society?

John Herrington's

Mission to Space has all of that... and more! Herrington is an astronaut. He was on space shuttle Endeavor, in 2002.

Mission to Space begins with his childhood, playing with rockets, and ends with Endeavor's safe return to Earth.

Here's the cover:

That is Herrington on the cover. Here's a page from inside that tells readers he is Chickasaw.

While he and the crew were waiting for Endeavor to blast off, the governor and lieutenant governor of the

Chickasaw Nation presented a blanket to NASA.

Those are two of the pages specific to Herrington being Chickasaw, but there's photos of him, training to be an astronaut, too. There's one of him, for example in a swimming pool, clad in his gear. And there's one that is way cool, of his eagle feather and flute, floating inside the International Space Station:

I absolutely love this book. There is nothing... NOTHING like it.

Native writer? Yes.

Sovereignty? Yes.

Tribally specific? Yes.

Present day? Yes.

The final two pages are about the Chickasaw language. In four columns that span two pages, there are over 20 words in English, followed by the word in Chickasaw, its pronunciation, and its literal description. And, of course, there's a countdown... in English and in Chickasaw.

Published in 2016 by the Chickasaw Nation's White Dog Press, they created a terrific

video about the book. You can

order it at their website. It is $14 for paperback; $16 for hardcover.

I highly recommend it! Hands down, it is the best book I've seen all year long.

In the last month or so I've been using the phrase "being loved by words" or "being loved by a book." I don't know if that works or not. Some might think it sounds goofy. It does, however, capture how I felt, reading the stories in Love Beyond Body, Space, and Time: An LGBT and Two Spirit Science Fiction Anthology. It is definitely a book I recommend to young adults.

The emotions it brought forth in me are spilling over again and again, of late. I don't know what to make of that tenderness that I feel, but it is real.

Around the same time that I read the anthology, I got an electronic copy of We Sang You Home by Richard Van Camp and Julie Flett. I had that same response to it. Indeed, there were moments when I was blinking back tears! Now, I've got a copy:

I've thought about it a lot since first reading it, trying to put words to emotions. Richard Van Camp and Julie Flett are Native. I've read many of their books and recommend them over and over. Working together on this one (their first one is

Little You), or apart, the books they give us are the mirrors that Native children need.

Just look at the joy and the smile of the child on the cover! That kid is loved, and that's what I want for Native kids! To feel loved by words, by story, by books.

We Sang You Home is a board book that, with very few words on each page, tells a child about how they were wanted, and how they came to be, and how they were, as the title says, sang home where they'd be kissed, and loved, and... where they, too, would sing.

Here's me, holding

We Sang You Home. See the joy on my face? Corny, maybe, but I wanna sing. About being loved, by this dear board book.

I highly recommend

We Sang You Home. Published by Orca in 2016, it is going to be gifted to a lot of people in the coming years.

When We Were Alone is one of those books that brought forth a lot of emotion as I read it. There were sighs of sadness for what Native people experienced at boarding schools, and sighs of--I don't know, love, maybe--for our perseverance through it all.

Written by David Alexander Robertson and illustrated by Julie Flett,

When We Were Alone will be released in January of 2017 from Highwater Press. I read the ARC and can't wait to hold the final copy of this story, of a young children asking her grandmother a series of questions, in my hands.

The story is meant for young children, though of course, readers of any age can--and should--read it.

It opens with the little girl saying:

Today I helped my kókom in her flower garden. She always wears colourful clothes. It's like she dresses in rainbows. When she bent down to prune some of the flowers, I couldn't even see her because she blended in with them. She was like a chameleon.

"Nókom, why do you wear so many colours?" I asked.

That child, wondering about something and then asking that "why" question is the format for the story. To this first question, her grandmother says that she had to go to school, far away, and that all the children had to wear the same colors. They couldn't wear the colourful clothes they did before they went to that school. Here's Julie Flett's illustration of the children, at school. I can't look at this illustration without my heart twisting:

Twisting at the expressions on their faces and wondering what they felt, and then I feel a different kind of emotion as I read the next page and look at the next illustration, because the grandma tells the child what they did to be colourful again. They rolled in the leaves, when they were alone:

There's a page about why she wears her hair so long, now, and why she speaks Cree, now. And, a page about being with family. Each one evokes the same thing. Tenderness. And a quiet joy at the power of the human spirit, to survive and persevere in the face of horrific treatment--in this case--by the Canadian government.

Stories of life at residential or boarding school are ones that Native people in the US and Canada tell each other. In Canada, because of the Truth and Reconciliation project, there's an effort to get these stories into print. I'm glad of that. We haven't seen anything like the Truth and Reconciliation project in the U.S., but teachers and libraries need not wait for something similar to start putting these books into schools, and into lesson plans.

When We Were Alone is rare. It is exquisite and stunning, for the power conveyed by the words Robertson wrote, and for the illustrations that Flett created. I highly recommend it.

Last year, Ashley Hope Perez's

Out of Darkness got a lot of buzz in my networks. Here's the synopsis:

"This is East Texas, and there's lines. Lines you cross, lines you don't cross. That clear?"

New London, Texas. 1937. Naomi Vargas and Wash Fuller know about the lines in East Texas as well as anyone. They know the signs that mark them. They know the people who enforce them. But sometimes the attraction between two people is so powerful it breaks through even the most entrenched color lines. And the consequences can be explosive.

Ashley Hope Pérez takes the facts of the 1937 New London school explosion—the worst school disaster in American history—as a backdrop for a riveting novel about segregation, love, family, and the forces that destroy people.

I got a copy and started reading. Then, I got to page 98 and paused at "I'm a low man on the totem pole." Prior to that reading, I'd had very limited--but positive--interactions with Ashley. So, I wrote to her about that line. Was it possible, I wondered, to take out or revise that one line in the next printing? Ashley wrote back, saying that she'd try.

Well... Ashley talked with her editor, and when the next printing was done, the line was changed. Ashley created a photo showing the change and shared it on social media, and she referenced our conversation. With her permission, I'm sharing her photo here:

I was--and am--gripped by, and deeply moved by the story she tells in

Out of Darkness. It got starred reviews and went on to win awards. With that change ("Nah, I'm a low man on the totem pole" was replaced with "Nah, no suck luck.", I can enthusiastically and wholeheartedly recommend it.

Here's my heartfelt thank you to Ashley for hearing my concern. For not being defensive. For not saying "but..." or any of the things people say instead of "ok." And of course, a shout out to her editor, Andrew Karre, and her publisher, Carolrhoda, for making the change.

Out of Darkness doesn't have any Native content. I'm recommending it because it is an excellent story, and because it is an example of what is possible when people speak up and others hear what they say.

Is

Out of Darkness in your library yet? If not, order it today.

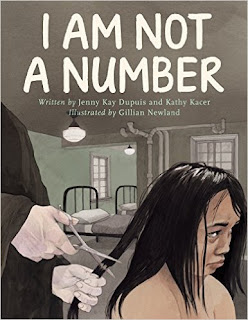

Jenny Kay Dupuis and Kathy Kacer's

I Am Not A Number, illustrated by Gillian Newland and due out from Second Story Press on October 4th of this year (2016), is one of the books I will recommend to teachers and librarians.

Dupuis is a member of the

Nipissing First Nation.

In 1928, Dupuis's grandmother, Irene Couchie Dupuis, was taken to a residential school in Canada. "Residential" is the term used in Canada for the schools created by the Canadian government. They are similar to the government boarding schools in the U.S. These were schools designed to "christianize" and "civilize" Native children. Some of them were mission schools where efforts were made to convert the children to whatever denomination ran the school.

I Am Not A Number opens with a frightening moment. An Indian agent is at their door, to take Irene and her brothers to residential school. When Irene's mother tries to keep Irene, the agent says "Give me all three or you'll be fined or sent to jail." Irene's parents, like many Native parents, were coerced into giving up their children.

When Irene arrives at the school and tells the nun (it is a mission school run by the Catholic Church) her name, she's told "We don't use names here. All students are known by numbers. You are 759." Irene thinks to herself that she is not a number, hence, the title for the book.

Her hair, as the cover shows, was cut. That happened to children when they arrived at the schools. It was one in a long string of traumatic moments that Native children experienced at residential or boarding schools.

Another was being punished for using their own language. At one point, Irene gives another girl a piece of bread. The girls speak briefly to each other in their language, Ojibwe. One of the nuns hits Irene with a wooden spoon, telling her "That's the devil's language." The nun drags Irene away for "a lesson." The lesson? Using a bedpan filled with hot coals to burn Irene's hands and arms. It was one kind of abuse that children received, routinely.

Irene's story ends on a different note than many of the residential and boarding school stories. She and her brothers go home for the summer. What she tells her parents about her time at the school moves them to make plans so that Irene and her brothers don't go back. When the agent shows up in the fall, the children hide in their dad's workshop. The agent looks for them, but Irene's dad challenges the agent, saying "Call the police. Have me arrested." In a low, even voice, he tells the agent that he (the agent) will never take his children away again. In the Afterword, Dupuis writes that her grandmother was only at the school for that one year. Her father's resistance worked. She was able to stay home, with her family.

Residential and boarding school stories are hard to read, but they're vitally important. In the back matter, Dupuis and Kacer provide historical information about the residential school system. They reference the report the

Truth and Reconciliation Commission (the TRC) released in 2015, too. The work of the TRC is being shared in Canada, and books like

I Am Not A Number should be taught in schools in Canada, and the U.S., too. In my experience, schools don't hesitate to share stories of "savage Indians" who "massacre" those "innocent settlers." In fact, the Native peoples who fought those settlers were fighting to protect their own families and homelands. Depicting them as aggressors is a misrepresentation of history. The history of the US and Canada is far more complex than is taught. It is way past time that we did a better job of teaching children the facts.

I'll end with this: I'm thrilled whenever I see books in which the author/publisher have opted not to use italics for the words that aren't English ones. There's no italics when we read miigwetch (thank you) and other Ojibwe words in

I Am Not A Number. Kudos to Second Story Press for not using italics.

Editor's Note: Beverly Slapin submitted this review essay of Anne M. Dunn's Fire in the Village. It may not be used elsewhere without her written permission. All rights reserved. Copyright 2016. Slapin is currently the publisher/editor of De Colores: The Raza Experience in Books for Children.

Dunn, Anne M. (Anishinabe-Ojibwe), Fire in the Village: New and Selected Stories. Holy Cow! Press, 2016.

Everyone knows a circle has no beginning and no end. In Fire in the Village, Anishinabe elder and wisdom-sharer Anne M. Dunn shows us a world in which everything in Creation has life, in which everything has volition, in which everything needs to be thanked and respected. It’s a world inhabited by mischievous Little People and wise elders; by four-leggeds, two-leggeds, flying nations, swimmers and those who creep; by hovering spirits and the children who can see them, and by haunting flashbacks that just won’t go away. Like points in a circle, each story has a place that informs the whole.

Here are 75 stories of how things came to be and how the humans (some of them, anyway) came to understand their responsibilities to all Creation. Stories of how the Little People can make huge things happen and how elders and children may be the only ones who understand and respect them. Stories about why butterflies are beautiful but can’t sing, why Tamarack drops its needles in winter, and why, every season, Anishinabeg give great thanks to the sap-giving maple trees. And gut-wrenching stories of the horrors inflicted on innocent little children in the Indian residential schools and stories of internalized racism and stories of good, loving parents who have alcoholism.

One of my favorite of Anne’s not-so-subtle stories (that reminds me of the US and Canadian governments’ failed attempts at cultural erasure of Indian peoples) involves an elder woman’s dreams to create a monument to fry bread, and the Department of Fry Bread Affairs—“suspicious that the women were engaged in resistance and eager to crush any possibility of dissent”—finds a way to destroy their Great Fry Bread Mountain and outlaw the women’s Fry Bread dances. But, if you know any history, you know that the struggle continues.

Without didacticism, without polemic, Anne gives each story the attention it needs so it can speak its own truth. How a little boy finds the perfect gift for his grandma. How a bear reciprocates for an elder woman’s generosity. How the Little People encourage an old man on his final journey. How a drum dreamed by a woman long ago can bring healing to the community.

Ojibwe artist Annie Humphrey’s beautifully detailed black-and-white pen-and-ink interior illustrations, together with the cover’s bright eye-catching colors in Prismacolor colored pencil, complement Anne’s tellings and will draw readers into the stories.

Children can enjoy acting out many of Anne’s stories about how things came to be, and some of the others as well. But, please—pitch the fake “Indians” with costumes, headdresses, wigs and face paint; also, the “woo-woos,” “hows,” “ughs,” and “hop-hop” dances. The most effective “costumes” I’ve seen were plain t-shirts and jeans for the two-legged characters, and minimal decorations to denote the four-leggeds, flying ones, swimming nations and those who creep.

In her Foreword, Anne writes:

The storyteller is usually a recognized member of the community, one who carries the stories that must be told. Perhaps young tellers will arrive to carry them forward. So our stories will continue to be passed from generation to generation.

“Some stories are told more often, she also writes, “because those are the stories that wantto be told. They are the ones that teach the vital lessons of our culture and traditions.” Depending on what lessons are being imparted, some stories may be for everyone, some for children, some for initiates, and some for adults. I would encourage parents, classroom teachers and librarians to use the same caution with this written collection.

As in the old times, when the people were taught by example and by stories, Anne sits in a circle with her audience and relates teachings and events from the long ago, from the distant past, from almost yesterday, and from now and beyond tomorrow—because every day, you know, brings a new story. If you listen for it. As Anne ends some of her stories, “That’s the way it was. That’s the way it is.”

‘Chi miigwech, Anne. I’m honored to call you friend.

Editor's Note: Beverly Slapin submitted this review essay of Joseph Bruchac's The Hunter's Promise. It may not be used elsewhere without her written permission. All rights reserved. Copyright 2016. Slapin is currently the publisher/editor of De Colores: The Raza Experience in Books for Children.

~~~~~

Bruchac, Joseph (Abenaki), The Hunter’s Promise: An Abenaki Tale, illustrated by Bill Farnsworth. Wisdom Tales (2015), kindergarten-up

Without didacticism or stated “morals,” Indigenous traditional stories often portray some of the Original Instructions given by the Creator, and children (and other listeners as well), depending on their own levels of understanding, may slowly come to know the stories and their embedded lessons.

Bruchac’s own retelling of the “Moose Wife” story, traditionally told by the Wabanaki and Haudenosaunee peoples of what is now known as the Northeastern US and Canada, is a deep story that maintains its important teaching elements in this accessible children’s picture book.

Here, a young hunter travels alone to winter camp to bring back moose meat and skins. Lonely and wishing for companionship, he finds the presence of someone who, unseen, has provided for his needs: in the lodge a fire is burning, food has been cooked, meat has been hung on drying racks and hide has been prepared for drying. On the seventh day, a mysterious woman appears, but is silent. The two stay together all winter and, when spring arrives and the hunter leaves for his village, the woman says only, “promise to remember me.”

As the story continues, young readers will intuit some things that may not make “sense.” Why does the hunter travel alone to and from winter camp? Why doesn’t the woman return with the hunter to the village? Why do their children grow up so quickly? Why does she ask only that the hunter promise to remember her? Who is she really? The story’s end is deeply satisfying and will evoke questions and answers, as well as ideas about how this old story may have connections to contemporary issues involving respect for all life.

Farnsworth’s heavily saturated oil paintings, with fall settings on a palette of mostly oranges and browns; and winter settings in mostly blues and whites, evoke the seasons in the forested mountains and closely follow Bruchac’s narrative. Cultural details of housing, weapons, transportation and clothing are also well done. The canoes, for instance, are accurately built (with the outside of the birch bark on the inside); and the women’s clothing display designs of quillwork and shell rather than beadwork (which would have been the mark of a later time).

That having been said, it would have been helpful to see representations of individual characteristics and emotion in facial expressions here. While Farnsworth’s illustrations aptly convey the “long ago” in Bruchac’s tale, this lack of delineation evokes an eerie, ghost-like presence that may create an unnecessary distance between young readers and the Indian characters.

Bruchac’s narrative is circular, a technique that might be unfamiliar with some young listeners and readers who will initially interpret the story literally as something “only” about loyalty and trust in human familial relationships; how these ethics encompass the kinship of humans to all things in the natural world might come at another time. I would encourage classroom teachers, librarians and other adults who work with young people to allow them to sit with this story. They’ll probably “get” it—if not at the first reading, then later on.

And I would save Bruchac’s helpful Author’s Note for afterthe story, maybe even days or weeks later:

It’s long been understood among the Wabanaki…that a bond exists between the hunter and those animals whose lives he must take for his people to survive. It is more than just the relationship between predator and prey. When the animal people give themselves to us, we must take only what we need and return thanks to their spirits. Otherwise, the balance will be broken. Everything suffers when human beings fail to show respect for the great family of life.

—Beverly Slapin

I've read My Heart Fills With Happiness by Monique Gray Smith, illustrated by Julie Flett, many times. I can't decide--and don't need to, really--which page is my favorite!

For now--for this moment--I just got off the phone with my daughter, Liz. She's not a little girl anymore. She's an adult, making plans for the the coming months as she finishes law school. She makes me so darn happy! When she was little, she liked "spinny skirts." We made several so she'd always have a clean one to wear to school. So, the cover of My Heart Fills With Happiness reminds me of those days with Liz, as she spun about in her spinny skirts.

Like I said, though, I just got off the phone with her, and as I think of her walking about in the many places she's going to be in May and June and July, I'm reminded of holding her hand as the two of us walked here, and there, oh those years ago! That memory, and this page, are so dear!

I love the page that shows a little girl dancing, her shawl gorgeously depicted as she moves. I love the page where the little boy holds a drumstick in his hand and sits at the drum. I love the page of the kids waiting for their bannock to be ready to eat. I'd love to meet the two Native women who created this book so I could thank them, in person.

My Heart Fills With Happiness got a

starred review from Publisher's Weekly and another one from

School Library Journal. From me, it gets all the stars in the night sky. Today is its birthday (to use the language I see on twitter). Get a copy, or two, from your favorite independent store.

Debby Slier's Loving Me is a delightful board book! Published in 2013 by Star Bright Books, it is definitely one I'll be recommending!

Here's the cover:

The very last page in the book tells us the woman and baby on the cover are Shoshone Bannock. Indeed, with that page we learn that the other photographs in the book are of children and family members who are Lakota Sioux, Navajo, Iroquois, and Potawatomi.

On the first page, we see a mom and baby. The text is "My mother loves me." That pattern is repeated over the rest of the book. A dad, a brother, a sister, an aunt, an uncle, a grandma, a grandpa, and a great grandma... embracing a child. They're clad in a range of clothing, from jeans and t-shirts to traditional clothing, but all of it in the day-to-day life of the individuals being shown. Slier's photo essay is a terrific mirror for Native kids, and, it'll help children and adults who aren't Native see us as in the fullness of our lives as Native people.

I heartily recommend Slier's

Loving Me, published by Star Bright Books.

Yesterday (Feb 6 2016), the American Indian Library Association (AILA) announced the winners of its 2016 Youth Literature Awards. Recipients of the awards will be formally recognized at the American Library Association's Annual Conference this summer, in Orlando, Florida.

The winner in the Young Adult category is House of Purple Cedar, by Choctaw writer, Tim Tingle. I asked him to tell me about the book and his thoughts upon hearing the news. Here, I share his generous and moving response.

~~~~~

From 1998 to 2013 I worked almost every day on “House of Purple Cedar.” That’s what happens when you’re a 50 year-old man writing in the voice of a 12 year-old girl. Don’t ask me why, I might say something like, “She was the ghost talking to me.” And it might be true. A life changes over 15 years, and many eye-opening events worked their way into the narrative; theft from an old man with dementia, which I witnessed. A major theme throughout the book, alcohol and the accompanying spousal abuse, I saw first-hand growing up.

In truth, I know and love every character in HOPC. Roberta Jean, the teenage girl with four bratty brothers, is my real-life sister Bobby Jean. Samuel, the quiet son of the preacher, is my brother Danny, who flipped his kayak and drowned a few years before I began the book. One-legged Maggie was a combo of my 7th grade history teacher, Mr. Beeson, who limped on a wooden leg; and his stubborn and hilarious counterpart, my reading teacher Mrs. Deemer. And as all Choctaws know, the Bobb brothers honor Bertram Bobb, our esteemed Choctaw chaplain.

As I reflect on where I was and why I included certain scenes and characters, I realize that so many of my friends are gone. Jay MacAlvain, a retired prof from Seminole State College, nurtured and coached me through my M.A. thesis, and a late-night story of his inspired the book. He told of a drunken sheriff in small town Oklahoma who, after an argument with his wife, boarded a train and shot dead the first Indian he saw. The dead Indian was Jay’s uncle, whom he never met. The sheriff knew no one would report him or complain. Until 1929, it was against the law in Oklahoma for an Indian to bear witness against a white man.

Reports of the suspected arson of New Hope Academy on New Year’s Eve, 1896, gave this story a home: Skullyville, once a bustling city in eastern Oklahoma. Skullyville became my second home. I walked the nearby railroad tracks for miles, sat amongst the gravestones, sang Choctaw songs—and listened.

My gone-before Choctaw friend, storyteller/writer Greg Rodgers, and I spent many days at Robber’s Cave, near Wilburton, OK, as I wrote and he revised at a furious pace. We walked over so many graveyards I felt more at ease among their residents than in town. I grew to trust my flying fingers.

I so longed that the stories I carried from these excursions would finally be told. I wanted the little girls of New Hope Academy to be honored, a century later. I wanted every woman who suffered from abuse to know they did not bring it upon themselves.

And I wanted non-Indian readers to experience the world from the viewpoint of the persecuted; the bruises on Amafo’s cheek, the tender touch of Pokoni….oh how I love those elders. The power and strength to forgive.

Yea though I walk through the valley of the sometimes heartless, I will walk the road of goodness, wave the light of forgiveness, and smile warm jokes along the way, as so many of my Choctaw kinfolks did.

~~~~~

This is the sixth set of books the American Indian Library Association has selected for its awards. The committee members change each time. In nearly every year, Tim's books are amongst the winners.

Crossing Bok Chitto won in the picture book category in 2008.

Saltypie: A Choctaw Journey from Darkness into Light was selected as an Honor Book in 2012. In 2014 his

How I Became a Ghost won the Middle Grade Award, and his

Danny Blackgoat: Navajo Prisoner won the Middle Grade Honor.

I am thrilled to see the winners of the 2016 American Indian Library Association's Youth Literature Awards!

Here's the graphic with the award winning books:

Picture Book Award Winner

Little You

Written by Richard Van Camp

Illustrated by Julie Flett

Published in 2013 by Orca Book Publishers

Picture Book Honor

Sitting Bull: Lakota Warrior and Defender of His People

Written and illustrated by S.D. Nelson

Published in 2015 by Abrams Books for Young Readers

Middle School Award Winner

In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse

by Joseph Marshall III

Written by Joseph Marshall III

Published in 2015 by Amulet Books

Middle School Honor

Dreaming in Indian: Contemporary Native Voices

Edited by Lisa Charleyboy and Mary Beth Leatherdale

Published in 2014 by Annick Press

Young Adult Winner

House of Purple Cedar

Written by Tim Tingle

Published n 2013 by Cinco Puntos Press

Young Adult Honor

Her Land, Her Love

Written by Evangeline Parsons Yazzie

Published in 2016 by Salina Bookshelf

From the announcement:"The American Indian Youth Literature Awards are presented every two years. The awards were established as a way to identify and honor the very best writing and illustrations by and about American Indians. Books selected to receive the award will present American Indians in the fullness of their humanity in the present and past contexts."

The jury for the award:

Naomi Bishop (Akimel O'odham) ChairGrace Slaughter (Cheyenne of Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma)Jolena Tillequots (Yakama)Linda Wynne (Tlingit/Haida)Melanie S. Toledo (Navajo Nation)Sunny Real Bird (Apsaalooke Crow Tribe)Angela Thornton (Cherokee Nation)

Congratulations to the winners.

These are outstanding books!

I read Alaya Dawn Johnson's Love is the Drug in 2014 when it came out. I think Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, or maybe Edith Campbell, told me about it. Elsewhere, I've written about books with a problematic line about Native people or culture, or, what we could call a microaggression.

Johnson's book is not about Native people or culture, but she does have a few lines in it that I want to call attention to--because they are the opposite of a microaggression. Indeed, I find them affirming.

They're about the Washington DC professional football team. You know the one I mean: the Redskins. On page 44, Emily and her dad are talking about the team's losing streak. He tells her it is because of their name, that it gives them bad luck. She's a bit skeptical. She thinks it is more about the players and their abilities. I enjoy their banter. He also makes the point that the team name is offensive, when he asks her if the team could get away with calling themselves the Washington Niggers. Pretty bold, but also quite effective.

Later, there's a part where one of the bad-guy-characters is talking about Thanksgiving--and the football game scheduled for that day. He says (p. 215):

"I hear the Redskins are going to play Dallas in a demonstration game. The good American spirit, cowboys versus Indians. The Indians will lose, of course. Everything is going back to normal."

I won't spoil the book for you by elaborating on what "normal" is... Here's the synopsis:

From the author of THE SUMMER PRINCE, a novel that's John Grisham's THE PELICAN BRIEF meets Michael Crichton's THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN set at an elite Washington D.C. prep school. Emily Bird was raised not to ask questions. She has perfect hair, the perfect boyfriend, and a perfect Ivy-League future. But a chance meeting with Roosevelt David, a homeland security agent, at a party for Washington DC's elite leads to Bird waking up in a hospital, days later, with no memory of the end of the night. Meanwhile, the world has fallen apart: A deadly flu virus is sweeping the nation, forcing quarantines, curfews, even martial law. And Roosevelt is certain that Bird knows something. Something about the virus--something about her parents' top secret scientific work--something she shouldn't know. The only one Bird can trust is Coffee, a quiet, outsider genius who deals drugs to their classmates and is a firm believer in conspiracy theories. And he believes in Bird. But as Bird and Coffee dig deeper into what really happened that night, Bird finds that she might know more than she remembers. And what she knows could unleash the biggest government scandal in US history.

I enjoyed the story. Published by Scholastic.

My grandfather, Rex Sotero Calvert, was Hopi. We never called him grandpa or grandfather. We called him Thehtay, which is the Tewa word for grandfather (Tewa is our language at Nambe Pueblo). Calvert is the name he was given when he went to boarding school, at Santa Fe Indian School. Before that, he was Rex Sotero Sakiestewa. He was born in 1895 at Mishongnovi Village.

At SFIS, he met my grandmother, Emilia Martinez. She was from Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo). They lived at Ohkay Owingeh and had six children: Delfino, Francis, Marcelino, Edward, Andrea, and Cecilia. To me, they were Uncle Del, Uncle Francis, Uncle Mars, and Aunt Cecilia. Edward--we call him Uncle John. He still lives there, at Ohkay Owingeh. Andrea--we call her mom.

When I talk with my mom, we sometimes talk about Thehtay. He lived with us at Nambe Pueblo when I was growing up. I remember him being out back, working the garden with a hoe... Suddenly he'd yell "The beans!" We'd have been playing in the garden as he worked, no doubt un-doing the work he'd been doing to irrigate that garden as we made little dams to divert the irrigation water! Remembering the beans, he'd throw down the hoe and run inside the house to add water to the pot of beans on the stove. When he was older, he'd sit in his wheelchair, softly singing Hopi songs to himself. I wish I'd listened to them, and that I'd learned some of them. What I do have are warm memories of him, of being with him, of his humor.

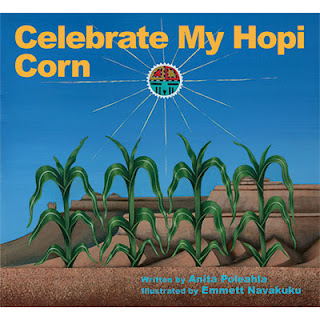

This morning as I read My Hopi Corn and My Hopi Toys, my thoughts, understandably, turned to Thehtay. Written by Anita Poleahla and illustrated by Emmett Navakuku, the two are board books from Salina Press.

Celebrate My Hopi Corn begins with a single corn kernel telling the reader that she has many sister kernels on an ear of corn, that they grow under a warm sun, and that as the days begin to shorten, the kernels take on different colors. Some are yellow, while others are blue or red or white. After they're harvested, the kernels are shelled off the cobs. For that, we're shown a Hopi girl in traditional clothes shelling the kernels off the cobs. Some kernels are ground into flour to make piki (a traditional food that is exquisite in form and flavor. In form it looks like a rolled up newspaper, with the paper itself being the piki, which is kind of like filo dough in its flakey texture). Some corn is used for dances, and, some is kept inside for the next planting season, when a Hopi man plants corn. That page, especially, made me think of Thehtay:

I don't have a memory of Thehtay planting seeds. My memory is of him in a button down shirt and jeans (nothing on his head; not wearing a belt or mocs as shown in the illustration) using a hoe to rid the garden of weeds.

As you see by the illustration, the text in

Celebrate My Hopi Corn is in two languages: Hopi, and English. The illustrations are a blend of realistic depictions of people, and, Hopi images like the one of the sun, and later, one of rain clouds. The book ends with a double paged spread of corn maidens:

Corn. Community. Ceremony. Planting. All are important to who the Hopi people are. I really like this little book and wish I could share it with Thehtay. Poleahla and Navakuku's second book,

Celebrate My Hopi Toys is a counting book of items used for play, but also for dance. I like it very much, too. Like

Celebrate My Hopi Corn, it is bilingual and shows items specific to Hopi people. Poleahla has been working on language instruction for many years. These little books will, no doubt, be much loved by Hopi children, but they're terrific for any child. For children who aren't Hopi, they provide a window to Hopi culture. A window--I will also note--that is provided by insiders who know just what can be shared with everyone.

They are available from

Salina Press.

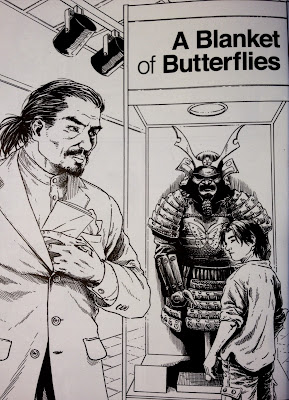

Check out the cover for Richard Van Camp's A Blanket of Butterflies:

Gorgeous, isn't it?

A Blanket of Butterflies, illustrated by Scott B. Henderson, is new this year (2015) from Highwater Press, an imprint of Portage & Main Press in Canada. That sword? It is a key piece of this story.

When you open the cover, here's the first page:

As the story opens, Sonny is at the

Northern Life Museum in Fort Smith, Northwest Territory. He's looking at a samurai suit of armor when he notices a man who is also looking at it. The man's name is Shinobu. See the paper he's pulling from his coat? He's at the museum with a specific purpose: to pick up that suit. It belongs to his family. The museum staff worked to identify who it belongs to, and then got in touch with Shinobu's family.

I gotta say--I love how Van Camp's story gets going--and here's why. So many things in museums are there due to theft and exploitation. Grave robbing of Native graves is rampant. Native protests led Congress to take action. In 1990, Congress wrote the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act to help tribal peoples reclaim remains and artifacts (see the

FAQ). That law, and

A Blanket of Butterflies, is all about dignity and humanity, for all peoples.

Back to the story...

There's something missing from the display. A sword. Shinobu learns where it is and sets out to get it, but Sonny knows where it is, too, and he also knows that it is risky for Shinobu to go there alone. Sonny follows him, and strikes up a conversation, noting that Shinobu has a butterfly tattoo on his hand. Things don't go well. Shinobu gets hurt...

Yesterday (Friday, November 14) I listened to

Acimowin on CJSR, an independent radio station in Edmondton, Canada. The guest? Richard Van Camp. I listened to him talk about

A Blanket of Butterflies and wish you could have heard him, too. There's a grandma in this story. She's the hero. Hearing him talk about her... awesome.

Get a copy of

A Blanket of Butterflies for your library or classroom, or for your own young readers. I really like it and highly recommend it.

And--check out that weekly radio show,

Acimowin, too, on Friday mornings. You can listen online. One of the best things people who write, review, edit, or publish children's and young adult literature can do, is listen to Native voices. Learn who we are, and what we care about. It'll help you do a better job at writing, or reviewing, or editing, or selecting, or... deselecting! Acimowin is hosted by Jojo, who tweets from @acimowin. I laughed out loud more than once, listening to the banter between these First Nations people... (Note: the radio show is not for young kids.) Love the graphics for the show!

The main character in

Whistle is a familiar one. Readers met him before. When Richard Van Camp's

The Lesser Blessed opens, it is the first day of school. Larry, the protagonist is cautious as he makes his way through the building, thinking "I'm Indian and I gotta watch it" (p. 2). One of the people he has to be cautious about is Darcy McMannus. Larry describes Darcy as the "most feared bully in town" (p. 19).

Van Camp's

Whistle is about Darcy--but he's not at school anymore. He's in a detention facility and writing letters to Brody, a character he beat up. The letters to Brody are part of a restorative justice framework for working with youth. I found that I needed time as I read

Whistle. Time to think about Darcy. He felt so real, and people with troubles like his require me to slow down and think about young people.

I highly recommend

Whistle for young adults. Published by Pearson as one of the titles in its

Well Aware series, you can

write to Van Camp and get it directly from him.

(My apologies! I'm behind on writing reviews of the depth that I prefer. Rather than wait, I'm uploading my recommendations and hope to come back later with a more in-depth look.)

I am happy to recommend The Apple Tree by Sandy Tharpe-Thee and Marlena Campbell Hodson. Published this year by Road Runner Press, the story is about Cherokee boy who plants an apple seed in his backyard.

Here's the cover:

Here's the little boy:

And here's the facing page for the one of the little boy:

I like this anthropomorphized story very much and think it is an excellent book all on its own, and would also be terrific for read-aloud sessions when introducing kids to stories about planting, or patience, or... apples!

When the apple tree sprouts and is a few inches high, the little boy puts a sign by it so that people will see it and not accidentally step on it. That reminds me of my grandmother. She did something similar. To protect a new cedar tree that sprouted near a roadside on the reservation, she make a ring of stones around it so people wouldn't run over it. The apple tree in Tharp-Thee's story grows, as does the boy, and eventually the tree produces apples.

When you read it, make sure you show kids the Cherokee words, and show them the Cherokee Nation's website, too. Help your students know all they can about the Cherokee people. Published in 2015 by The Road Runner Press. The author, Sandy Tharpe-Thee, is a tribal librarian and received the

White House Champion of Change award for her work. She is an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation.

A couple of years ago at a library conference, a friend (she is white) told me about conversations she's had with people who say "Debbie Reese hates white people." She tells them that isn't true, and I'm grateful to her for doing that. It seems silly to say it isn't true, but unfortunately, it needs saying!

They say that, I suspect, because I've been critical of a book they like, or because they're friends with an author whose book I've critiqued.

There's a perception that I'll criticize books with Native characters if the author or illustrator isn't Native. That isn't true, either.

For those who need proof, below is a list of books I like that are by writers who are not Native. Some are books categorized as being about Native people, while others are ones that include Native content but aren't categorized as being about Native people. Some of these are books on an extensive list I created with Jean Mendoza in 2006 and some are ones I've written about, or recommended, elsewhere.

- Powwow by George Ancona, published in 1993 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Earth Daughter: Alicia of Acoma Pueblo by George Ancona, published in 1995 by Macmillan.

- The Impossible Knife of Memory by Laurie Halse Anderson, published in 2014 by Viking.

- Very Last First Time by Jan Andrews, illustrated by Ian Wallace, published in 1998 by Aladdin.

- Who Will Tell My Brother? by Marlene Carvell, published in 2004 by Hyperion.

- Whale Snow by Debby Dahl Edwardson, illustrated by Annie Patterson, published in 2004 by Charlesbridge.

- My Name Is Not Easy, by Debby Dahl Edwardson, published in 2013 by

- On the Move by K.V. Flynn, published in 2014 by Wynnpix Productions.

- Daughter of Suqua by Diane Hamm Johnson, published in 1997 by Albert Whitman.

- Shadowshaper by Daniel José Older, published in 2015 by Arthur A. Levine.

- A Children's Guide to Arctic Birds by Mia Pelletier, illustrated by Danny Christopher, published in 2014 by Inhabit Media.

- Cradle Me by Debbie Slier, published in 2012 by Starbright Books.

I read a lot of other books, too, that aren't about Native people. A recent one that I read and love is Zetta Elliot's

Dayshaun's Gift.

And, Matt de la Pena's

The Living. And

Fake ID by Lamar Giles. And

Ash by Malinda Lo.

When Reason Breaks by Cindy L. Rodriguez! And Benjamin Alire Saenz's

Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, and Aisha Saeed's

Written in the Stars. Back when I was teaching first grade, Eric Carle's books were amongst my favorites to read aloud at storytime. And we have a dear video from 1992 when I was reading Galdone's

Over in the Meadow to our then-baby, Liz. The dear part is her chiming in as I read.

Right now, I'm partway through

All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely.

And I can't wait for my copy of Don Tate's

The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton: Poet. Did you watch the video yet?

If you're one of the people who hears other people say "Debbie Reese hates white people," I hope you'll tell them to go to my site and look for a post titled "Debbie Reese hates white people."

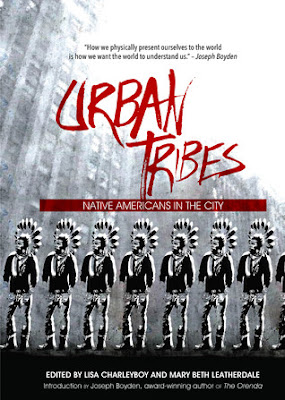

Did you read Dreaming in Indian, edited by Lisa Charleyboy and Mary Beth Leatherdale? It came out last year to much acclaim, and last week, it received an award from Wordcraft Circle. Awards from ones own community are especially valuable. They signal to a reader that people who know a people, from the inside, find the book to be amongst the very best available.

Charyleyboy and Leatherdale's new book, Urban Tribes: Native Americans in the City, also published by Annick Press, was released in August of this year.

Isn't that cover exquisite? Inside you'll find art, and stories, and poems written by Native people. There's joy, for example, in the photographs of actor Tatanka Means. You may have

seen him in Tiger Eyes, the film adaptation of Judy Blume's story. Photographs of him in

Urban Tribes include one of his dad, Russell Means, braiding his hair, and several of him holding a mic.

Talong Long, an 8th grader in Phoenix, who is Sicangu Lakota, Diné, writes about how hard it is "to convince people--adults especially" what his life is like. He writes:

There are also a lot of other people here who aren't Native and don't know about Natives. They say things like 'You live in the city? I thought you lived on a reservation. You have a house? I thought you lived in a teepee.'

I find his words striking as I read them this week in light of ongoing arguments made by adults who think kids can spot stereotyping and bias. Long also writes about the Native community in Phoenix that sustains him. Fifteen year old Maggie, and 17 year old Michaela are Cree/Dene. Their thoughts on going back and forth from Meadow Lake, Saskatchewan to Beauval, on the English River First Nation, are spread over six delightful, gorgeous pages.

Urban Tribes includes

Dear Native College Student, You Are Loved, an essay by Dr. Adrienne Keene that circulates widely in Native networks online and a two-page spread of the Faceless Doll Project created by students at the Eric Hamber Secondary School in Vancouver, through which students use collage to call attention to the missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada.

And, it includes a two-page spread full of information about Native peoples in the US and Canada.

As with

Dreaming in Indian, I find myself studying it, pausing, and thinking about the young Native people who will study it, too, finding possible selves in the pages of

Urban Natives. I highly recommend it.

~~~~~

Shuck, Kim (Tsalagi, Sauk/Fox, Polish), Smuggling Cherokee. Greenfield Review Press, 2005; grades 7-up

Smuggling Cherokee is full of powerful insight: part autobiography, part musing, part outrageous wit, and part punch-in-the-gut startling. Kim Shuck is a visionary: she knows who she is, what she comes from, and what she’s been given to do. Her poems are honest and passionate, and, without polemic, will shatter just about every stereotype about Indians that anyone has ever espoused: The man asks me,/ “Do you speak Cherokee?”/ But it’s all I ever speak/ The end goal of several generations of a/ smuggling project./ We’ve slipped the barriers,/ Evaded border guards./ I smile,/ “Always.”

Some of Kim’s poems are tenderly, achingly beautiful: The water I used to drink spent time/ Inside a pitched basket/ It adopted the internal shape/ Took on the taste of pine/ And changed me forever. And for those who didn’t know, or didn’t care to know, the many faces of depredation:

I call the slave master

Who lost track of my ancestor

A blanket for you

In gratitude.

I call the soldier

With a tired arm

Who didn’t cut deeply enough

Into my great-great grandfather’s chest to kill clean.

I return your axehead

Oiled and sharpened

Wield it against others with equal skill.

Will the boarding school officer come up?

The one who didn’t take my Gram

Because of her crippled leg.

No use as a servant – such a shame with that face…

Finally the shopkeeper’s wife

Who traded spoiled cans of fruit

For baskets that took a year each to make.

Thank you, Faith, for not poisoning

Quite all

Of my

Family.

Blankets for each of you,

And let no one say

That I am not

Grateful for your care.

Smuggling Cherokee, as with all of Kim Shuck’s poems, will resonate with Indian middle and high school readers. Students who are not Indian may not “get” some of them the first time around, but they will, eventually, if given the space to sit with them.

Kim Shuck—a poet, teacher, fine artist and parent of at least three—teaches college courses in Native Short Literature, creates phenomenal beadwork and basketry, curates museum collections, teaches origami to young children as an introduction to geometry, grows vegetables, converses with trees, takes long walks, and meditates while doing piles of laundry. She won the Native Writers of the Americas First Book Award for Smuggling Cherokee, as well as the Diane Decorah Award for Poetry, she has a fierce and gentle heart, and I’m honored to call her “friend.”

—Beverly Slapin

(Note: Smuggling Cherokee can be ordered from [email protected]. Discount for class sets, free shipping.)

Two years ago I read--and recommended--Kamik: An Inuit Puppy Story, a delightful story about a puppy named Kamik and his owner, a young Inuit boy named Jake. In it, Jake is trying to train Kamik, but--Kamik is a pup--and Jake is frustrated with the pup's antics. Jake's grandfather is in the story, too, and tells him about sled dogs, imparting Inuit knowledge as he does.

Today, I'm happy to recommend another story about Kamik and Jake. The author of Kamik: An Inuit Puppy Story is Donald Uluadluak. This time around, the writer is Matilda Sulurayok. Like Uluadluak, Sulurayok is an Inuit elder.

As the story opens, the first snow of the season has fallen. Jake thinks that, perhaps, he can start training Kamik to be a sled dog, but Kamik just wants to play with the other dogs. Of course, Jake is not liking that at all! Anaanatsiaq (it means grandmother) sees all this going down. She reminisces about her childhood, telling Jake how her dad taught her to train sled dog pups--by playing with them:

In her storytelling of those memories, Anaanatsiaq is teaching Jake. Then she fastens a small bundle on Kamik and suggests Jake take Kamik out, away from the other dogs, for a picnic. They set off walking.

After awhile, Jake opens the picnic bundle. Inside, he finds things to eat, but he also finds a sealskin and a harness.

Playtime training, then, is off and running!

Things get tense, though, when Kamik takes off after a rabbit in the midst of a darkening sky, and Jake realizes he hasn't taught him the command to stop. The rabbit, as you can see, gets away.

Jake is scared, but in the end, Kamik gets him home, where he learns a bit more about sled dogs and their sense of smell.

Through Kamik, Jake, and his grandparents, kids learn about Inuit life, and they learn some Inuit words, too. A strength of both these books is the engaging, yet matter-of-fact, manner in which elders pass knowledge down to kids. Nothing exotic, and nothing romanticized, either.

I highly recommend

Kamik's First Sled, published in 2015 by Inhabit Media.

When I get a book written by a Native person, my heart soars with delight.

In the mail yesterday, I got a copy of Robbie Robertson's Hiawatha and the Peacemaker.

For now, I'm focusing on the words. To start, I flipped to the back pages and read the two-page Author's Note, in which Robertson tells us that he was nine years old when he was told the story of Hiawatha and the Peacemaker. Here's the last paragraph in Robertson's note. When I read it, my delight grew:

Some years later in school, we were studying Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem about Hiawatha. I think I was the only one in the class who knew that Longfellow got Hiawatha mixed up with another Indian. I knew his poem was not about the real Hiawatha, whom I had learned about years ago, that day in the longhouse. I didn't say anything. I kept the truth to myself.. till now.

Robertson has done us all a huge service. Teachers and librarians everywhere can ditch all those books with "gitchee gumee" in them. With

Hiawatha and the Peacemaker, young people can--as Robertson said--learn about the real Hiawatha. And, given that Robertson includes the fact that Peacemaker had a speech impediment, I think people within the special needs community will find Robertson's book an invaluable addition to their shelves.

I would love to be at the American Library Association's annual conference next week. At the closing session on Tuesday, June 30th, Robertson and Shannon will have a conversation with Sari Feldman, the incoming president of the association:

Before I sign off on this post (I'll be back with a more in-depth look at the book later), do make sure you get a copy of Sebastian Robertson's biography of his dad:

Rock and Roll Highway: The Robbie Robertson Story! It is terrific.

Joseph Marshall III is an enrolled member of the Sicangu Lakota (Rosebud Sioux) tribe. Born and raised on the Rosebud Sioux reservation, he is the author of several books about Lakota people. Last year, I read his The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History. I highly recommend it. In 2011, Marshall's book was selected for the One Book South Dakota project. Over 2400 Native high school students in South Dakota were given a copy of it. How cool is that? (Answer: very cool, indeed!)

Yesterday, I finished his

In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse. First thing I'll say? Get it. Order it now. It won't hit the bookstores till later this year, but pre-order it for your own kids and your library. Like

The Journey of Crazy Horse, it provides insights and stories that you don't get from academic historians.

To my knowledge, there is nothing like it for kids. Some of the reasons I'm keen on it?

First, it is set in the present day on the

Rosebud Sioux reservation. Regular readers of AICL know that I think it is vitally important that kids read books about Native people, set in the present day. Such books provide Native kids with characters that reflect our existence as people of the present day, and they help non-Native kids know that--contrary to what they may think--we weren't "all killed off" by each other, by White people, or by disease, either.

Second, the protagonist, Jimmy McClean, is an eleven-year old Lakota boy with blue eyes and light brown hair. Blue eyes? Light brown hair?! Yes. His dad's dad was White. Those blue eyes and light brown hair mean he gets teased by Lakota kids and White ones, too.

Third, it is a road trip book! I love road trips. Don't you? In this one, his grandfather (his mom's dad) takes him, more or less, in the footsteps of Crazy Horse. Along the way, he learns a lot about Crazy Horse, who--like Jimmy--had light brown hair. When his grandfather is in storytelling mode, giving him information about Crazy Horse, the text is in italics.

Fourth, Jimmy's mom is a Head Start teacher! That is way cool. My little brother and my little sister went to Head Start! When I was in high school, I'd cut school and volunteer at the Head Start whenever I could. But you know what? I can't think of a single book I've read in which one of the characters is a head start teacher, but for goodness sake! Head Start is a big deal! It is reality for millions of people. We should have books with moms or dads who work at Head Start!

Fifth, Jimmy's grandfather imparts a lot of historical information as they drive. At one point, Grandpa Nyles asks him if he's heard of the Oregon Trail. Jimmy says yes, and his grandpa says (p. 29):

"Before it was called the Oregon Trail, it was known by the Lakota and other tribes as Shell River Road. And before that, it was a trail used by animals, like buffalo. It's an old, old trail."

I love that information! It tells readers that Native peoples were here first, and we had names for this and that place.

Sixth, they visit a monument. His grandpa tells him that the Lakota people call it the Battle of the Hundred in the Hands, and that others call it the Fetterman Battle or the Fetterman Massacre. They read the inscription on the monument. See the last line? It reads "There were no survivors." That is not true, his grandpa tells him. Hundreds of Lakota and Northern Cheyenne survived that battle. It is a valuable lesson, for all of us, about perspective, words, who puts them on monuments, why those particular ones are chosen, etc.

Last reason I'll share for now is that Marshall doesn't soft pedal wartime atrocities. Through his grandfather, Jimmy learns about mutilations done by soldiers, and by Lakota people, too. It isn't done in a gratuitous way. It is honest and straightforward, and, his grandfather says "it's a bad thing no matter who does it."

The history learned by reading

In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse and the growth Jimmy experiences as he spends time on that road trip with his grandfather make it invaluable.

In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse, with illustrations by Jim Yellowhawk, is coming out in November from Amulet Books (an imprint of Abrams). Pitched at elementary/middle grade readers, I highly recommend it.

View Next 25 Posts

So excited for this! I just have one question...what is the lower end of the age recommendation you have for this book? I can only order up to grades 6, and want to make sure that it is appropriate (otherwise I will send this link up to our teen librarian!).

Maeve,

Lower age --- upper, too --- is dependent on the reader, and the adults around that reader.

Get a copy and see what you think. The lesson plan in back is designated as being for grades 5-7, which means roughly 11 years at the young end, and 13 at the upper end, but without a doubt--the book can be used with teens, college students...

Debbie