new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: osama bin laden, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 16 of 16

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: osama bin laden in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: DanP,

on 10/6/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Religion,

Politics,

India,

pakistan,

middle east,

Islam,

Asia,

taliban,

Moses,

osama bin laden,

Muslin,

jihad,

islamic history,

qur'an,

*Featured,

Pakistani Taliban,

Dr. Mona Kanwal Sheikh,

drone attacks,

Faith Militant,

jihadi,

middle eastern history,

muslim counrties,

pakistan history,

Add a tag

All simplistic hypothesis about “what drives terrorists” falter when there is suddenly in front of you human faces and complex life stories. The tragedy of contemporary policies designed to handle or rather crush movements who employ terrorist tactics, are prone to embrace a singular explanation of the terrorist motivation, disregarding the fact that people can be in the very same movement for various reasons.

The post The different faces of Taliban jihad in Pakistan appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Lizzie Furey,

on 11/27/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

9/11,

terrorism,

osama bin laden,

*Featured,

saddam hussein,

Abbottabad,

Bin Laden,

Bin Laden Tapes,

Flagg Miller,

The Audacious Ascetic,

What the Bin Laden Tapes Reveal About Al-Qa'ida,

Add a tag

In the months following the Taliban's evacuation of Kandahar, Afghanistan, in December 2001, cable news networks set up operations in the city in order to report on the war. In the dusty back rooms of a local recording studio, a CNN stringer came across an extraordinary archive: roughly 1,500 audiotapes taken from Osama bin Laden's residence, where he had lived from 1997-2001, during al Qaeda's most coherent organizational momentum.

The post What I learned about al Qaeda from analyzing the Bin Laden tapes appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 11/25/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Anders Breivik,

Clifford R. Backman,

greater west,

middle east history,

religious ideology,

Books,

History,

Religion,

politics,

american history,

Iraq,

Middle East,

Afghanistan,

America,

Islam,

christianity,

terrorism,

British,

judaism,

Syria,

ideology,

osama bin laden,

British history,

*Featured,

Timothy McVeigh,

american politics,

extremism,

religious history,

Add a tag

At its root, Islam is as much a Western religion as are Judaism and Christianity, having emerged from the same geographic and cultural milieu as its predecessors. For centuries we lived at a more or less comfortable distance from one another. Post-colonialism and economic globalization, and the strategic concerns that attended them, have drawn us into an ever-tighter web of inter-relations.

The post The “Greater West” and sympathetic suffering appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Heather Saunders,

on 11/2/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Law,

Journals,

Media,

terrorism,

human rights,

torture,

CIA,

osama bin laden,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

international law,

oxford journals,

Zero Dark Thirty,

US government,

London Review of International Law,

LRIL,

Daniel Joyce,

Gabrielle Simm,

Add a tag

It is said in the domestic practice of law that the facts are sometimes more important than the law. Advocates often win and lose cases on their facts, despite the perception that the law’s formalism and abstraction are to blame for its failures with regards to delivering justice.

The post The killing of Osama bin Laden: the facts are hard to come by, and where is the law? appeared first on OUPblog.

The United States has declassified a number of documents that were confiscated during the raid on Bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan during which he was assassinated. Among the trove of documents, there were also 39 English-language books on his book shelves.

The former Al-Quaeda leader owned a number of titles by Western writers that were critical of the United States, as well as books on Islam. His reading list included: “Obama’s Wars” by Bob Woodward; “America’s Strategic Blunders” by Willard Matthias; “America’s ‘War on Terrorism” by Michel Chossudovsky; and “New Pearl Harbor: Disturbing Questions about the Bush Administration and 9/11″ by David Ray Griffin, among others.

Follow this link to check out the entire list.

By: Alice,

on 5/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

justice,

revenge,

osama bin laden,

laden’s,

*Featured,

osama,

laden,

David Jenkins,

How 9/11 Changed the Law,

Long Decade,

war or terror,

pesavento,

Books,

Law,

Add a tag

By David Jenkins

On 2 May 2011, as news spread that a US Navy SEAL team had killed Osama bin Laden, Americans across the country erupted in spontaneous celebrations. Cameras showed the world images of jubilant crowds in Washington, DC and at New York City’s Ground Zero, reveling in the long-awaited payback against America’s nemesis. With bin Laden’s death, nearly ten years after the fall of the Twin Towers, a conflict-weary nation had its revenge. Many now expected closure to the trauma of 9/11 and the costly, decade-long “war on terror.”

But would Americans find the closure they sought in bin Laden’s demise? A new psychological study by international researchers indicates that some haven’t. According to it, many Americans indeed reported feeling that the killing of bin Laden was “vicarious revenge” for the victims of the 9/11 attacks and that justice had been served. These respondents were not just satisfied with bin Laden’s death itself, but were especially pleased that American forces — not accident, natural causes, or allies — had finally gotten him. Interestingly, however, the study concluded that those who expressed these sentiments the strongest desired further retribution against any others deemed somehow responsible for those September atrocities. So, three years on, bin Laden’s killing has not wholly slaked the collective thirst for revenge. This study’s findings suggest that the “long decade” after 9/11 has an additional psychological component that goes beyond the themes discussed by that volume’s contributors. If this is so, the changes in law occurring over this transformative period could be manifestations not just of a pervasive fear of another attack, but of a latent, still aggressive revanchism.

Flag-waving in Times Square on the night Osama bin Laden killed. Photo by Josh Pesavento. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Thus, while public attitudes towards the “war on terror” continue to shift, it remains uncertain just how they relate to the significant, long-term legal developments brought about by that conflict. In the years immediately after 2001 — alongside the military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan — the United States and Britain, in particular, introduced controversial counter-terrorism measures as part of a transnational effort to fight the unconventional threat of terrorism, prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and reassert national security interests in a globalized world where the nation-state had suddenly lost its monopoly on highly destructive, political violence. While these challenges were clear after 9/11, the best means of tackling them were not — especially in ways compatible with existing norms of liberal democracy, such as a respect for constitutional governance, the rule of law, and human rights. Extreme, often covert measures like military detention, torture, and extraordinary rendition directly challenged and raised doubts about our commitments to these fundamental principles. While the worst practices have since come to an end, other controversial, if less dramatic, counter-terrorism measures remain in effect. Preventive restrictions on liberty, use of secret courtroom evidence, drone strikes, and widespread surveillance, for example, are just some of the national security powers that have taken root over this long decade. Once touted by politicians as necessary but temporary, such powers now appear to be permanent with no sign of rollback. By and large, the public has accepted and sometimes welcomed many of these strategies for defeating terrorism, even as its skepticism towards government security policies has grown.

At this point, it might be too simplistic to say that these legal changes persist because the “war on terror” also does; to do so is to imagine that the pre-9/11 world can somehow be recaptured, that we remain in a suspended state of exception from the normal, and that this conflict with terrorism still has a definite, if yet un-seeable, end. Sadly, as the aftermath of Osama bin Laden’s death shows, this is all probably untrue. The threat of terrorism is likely inextricable from the globalized world in which we now live and the increasing securitization of our democracies belie a return to liberal norms as once understood. Military withdrawals from Iraq and Afghanistan signal an end neither to political instability nor insecurity in the region. Al Qaeda and Islamists still call for jihad against the West three years after the fall of bin Laden, their martyred standard-bearer. Nor does it seem that the fires of revenge for 9/11 have yet gone cold in us since his killing; if those coals still smolder — as researchers claim they do — then we risk embracing a new age of perpetual conflict and suspicion. In this age, neither victory nor justice will be achievable, but what we were fighting for will have been forever lost.

David Jenkins is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Copenhagen. He holds a JD from Washington & Lee School of Law and a Doctor of Civil Law degree from the McGill University Institute of Comparative Law. Along with Amanda Jacobsen and Anders Henriksen he is the Editor of The Long Decade: How 9/11 Changed the Law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Justice, revenge, and the law after Osama bin Laden appeared first on OUPblog.

Former U.S. Secretary of Defense and CIA director Robert M. Gates will publish his memoir with Random House’s Alfred A. Knopf.

Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War will come out in January 2014 with a first printing of 200,000 copies. The book will talk about the country’s fight against al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, but also tackle his domestic struggles. Here is an excerpt from the introduction:

this book is also about my political war with Congress each day I was in office … and the dramatic contrast between my public respect, bipartisanship, and calm, and my private frustration, disgust, and anger. There were also political wars with the White House, staff, and occasionally with the presidents themselves and often with their Vice Presidents, Dick Cheney and Joe Biden. And finally, there was my bureaucratic war with the Department of Defense and the military services, aimed at transforming a department organized to plan for war into one that could wage war, changing the military forces we had into the military forces we needed to succeed.

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

By: KimberlyH,

on 2/23/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Religion,

politics,

borders,

Current Affairs,

CNN,

Afghanistan,

Oxford University Press,

negotiation,

taliban,

terror,

United States,

osama bin laden,

Kandahar,

gopal,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

khan,

Anand Gopal,

Carnegie Council,

Hajji Burget Khan,

New America Foundation,

Peter Bergen,

Talibanistan,

bergen,

anand,

burget,

hajji,

Add a tag

CNN National Security Analyst Peter Bergen visited the Carnegie Council in New York City late last year to discuss Talibanistan, a collection he recently edited for Oxford University Press. Bergen, who produced the first television interview with Osama bin Laden in 1997, discussed the positive changes in Afghanistan over the past ten years: “Afghans have a sense that what is happening now is better than a lot of things they’ve lived through…”

Bergen was joined at the event by Anand Gopal, who wrote the first chapter in Talibanistan. Gopal recounts the story of Hajji Burget Khan, a leader in Kandahar who encouraged his fellow Afghans to support the Americans after the fall of the Taliban. But after US forces received bad intelligence, perceiving Hajji Burget Khan as a threat, he was killed in May 2002, which had a disastrous effect in the area, leading many to join the insurgency.

Peter Bergen on Afghanistan:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Anand Gopal on the tragic mistake made by the American military:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Peter Bergen is the director of the National Securities Studies Program at the New America Foundation, and is National Security Analyst at CNN. He is the author of Manhunt, The Longest War and The Osama Bin Laden I Know. Anand Gopal is a fellow at the New America Foundation and a journalist who has reported for the Wall Street Journal, the Christian Science Monitor, and other outlets on Afghanistan. Talibanistan: Negotiating the Borders Between Terror, Politics, and Religion was edited by Peter Bergen and Katherine Tiedemann and includes contributions from Anand Gopal.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Have conditions improved in Afghanistan since 2001? appeared first on OUPblog.

Simon & Schuster’s Gallery Books partnered with indie comics publisher Bluewater Productions to create a graphic novel entitled Killing Geronimo: The Hunt for Osama Bin Laden.

Simon & Schuster’s Gallery Books partnered with indie comics publisher Bluewater Productions to create a graphic novel entitled Killing Geronimo: The Hunt for Osama Bin Laden.

The book focuses on the Navy SEAL Team Six mission that killed Osama Bin Laden. The book has been released today. Artist James Boulton illustrated. Writers Jerome Maida and Darren G. Davis collaborated wrote the story.

Maida had this statement in the release: “This is an epic story nearly ten years in the making. It’s like a true-to-life Jason Bourne novel. And like those Ludlum books, it’s a complex labyrinth of intrigue, danger and politics culminating in an action-packed ending.” (Via CNN)

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

By: Alice,

on 9/4/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

World War II,

Lincoln,

civil war,

Barack Obama,

Vietnam,

gulf war,

George Bush,

fdr,

Nixon,

kissinger,

osama bin laden,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

Mark Owen,

American Presidency at War,

Andrew Polsky,

Elusive Victories,

Navy SEALs,

No Easy Day,

Add a tag

By Andrew J. Polsky

No Easy Day, the new book by a member of the SEAL team that killed Osama bin Laden on 30 April 2011, has attracted widespread comment, most of it focused on whether bin Laden posed a threat at the time he was gunned down. Another theme in the account by Mark Owen (a pseudonym) is how the team members openly weighed the political ramifications of their actions. As the Huffington Post reports:

Though he praises the president for green-lighting the risky assault, Owen says the SEALS joked that Obama would take credit for their success…. one SEAL joked, “And we’ll get Obama reelected for sure. I can see him now, talking about how he killed bin Laden.”

Owen goes on to comment that he and his peers understood that they were “tools in the toolbox, and when things go well [political leaders] promote it.” It is an observation that invites only one response: Duh.

Of course, a president will bask in the glow of a national security success. The more interesting question, though, is whether it translates into gains for him and/or his party in the next election. The direct political impact of a military victory, a peace agreement, or (as in this case) the elimination of a high-profile adversary tends to be short-lived. That said, events may not be isolated; they also figure in the narratives politicians and parties tell. For Barack Obama and the Democrats in 2012, this secondary effect is the more important one.

Wartime presidents have always been sensitive to the ticking of the political clock. In the summer of 1864, Abraham Lincoln famously fretted that he would lose his reelection bid. Grant’s army stalled at Petersburg after staggering casualties in his Overland campaign; Sherman’s army seemed just as frustrated in the siege of Atlanta; and a small Confederate army led by Jubal Early advanced through the Shenandoah Valley to the very outskirts of Washington. So bleak were the president’s political fortunes that Republicans spoke openly of holding a second convention to choose a different nominee. Only the string of Union victories — at Atlanta, in the Shenandoah Valley, and at Mobile Bay — before the election turned the political tide.

Election timing may tempt a president to shape national security decisions for political advantage. In the Second World War, Franklin Roosevelt was eager to see US troops invade North Africa before November 1942. Partly he was motivated by a desire to see American forces engage the German army to forestall popular demands to redirect resources to the war against Japan, the more hated enemy. But Roosevelt also wanted a major American offensive before the mid-term elections to deflect attention from wartime shortages and labor disputes that fed Republican attacks on his party’s management of the war effort. To his credit, he didn’t insist on a specific pre-election date for Operation Torch, and the invasion finally came a week after the voters had gone to the polls (and inflicted significant losses on his party).

The Vietnam War illustrates the intimate tie between what happens on the battlefield and elections back home. In the wake of the Tet Offensive in early 1968, Lyndon Johnson came within a whisker of losing the New Hampshire Democratic primary, an outcome widely interpreted as a defeat. He soon announced his withdrawal from the presidential race. Four years later, on the eve of the 1972 election, Richard Nixon delivered the ultimate “October surprise”: Secretary of State Henry Kissinger announced that “peace is at hand,” following conclusion of a preliminary agreement with Hanoi’s lead negotiator Le Duc Tho. In fact, however, Kissinger left out a key detail. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu balked at the terms and refused to sign. Only after weeks of pressure, threats, and secret promises from Nixon, plus renewed heavy bombing of Hanoi, did Thieu grudgingly accept a new agreement that didn’t differ in its significant provisions from the October version.

But national security success yields ephemeral political gains. After the smashing coalition triumph in the 1991 Gulf War, George H. W. Bush enjoyed strikingly high public approval ratings. Indeed, he was so popular that a number of leading Democrats concluded he was unbeatable and decided not to seek their party’s presidential nomination the following year. But by fall 1992 the victory glow had worn off, and the public focused instead on domestic matters, especially a sluggish economy. Bill Clinton’s notable ability to project empathy played much better than Bush’s detachment.

And so it has been with Osama and Obama. Following the former’s death, the president received the expected bump in the polls. Predictably, though, the gain didn’t persist amid disappointing economic results and showdowns with Congress over the debt ceiling. From the poll results, we might conclude that Owen and his Seal buddies were mistaken about the political impact of their operation.

But there is more to it. Republicans have long enjoyed a political edge on national security, but not this year. The death of Osama bin Laden, coupled with a limited military intervention in Libya that brought down an unpopular dictator and ongoing drone attacks against suspected terrorist groups, has inoculated Barack Obama from charges of being soft on America’s enemies. Add the end of the Iraq War and the gradual withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan and the narrative takes shape: here is a president who understands how to use force efficiently and with minimal risk to American lives. Thus far Mitt Romney’s efforts to sound “tougher” on foreign policy have fallen flat with the voters. That he so rarely brings up national security issues demonstrates how little traction his message has.

None of this guarantees that the president will win a second term. The election, like the one in 1992, will be much more about the economy. But the Seal team operation reminds us that war and politics are never separated.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

By: John,

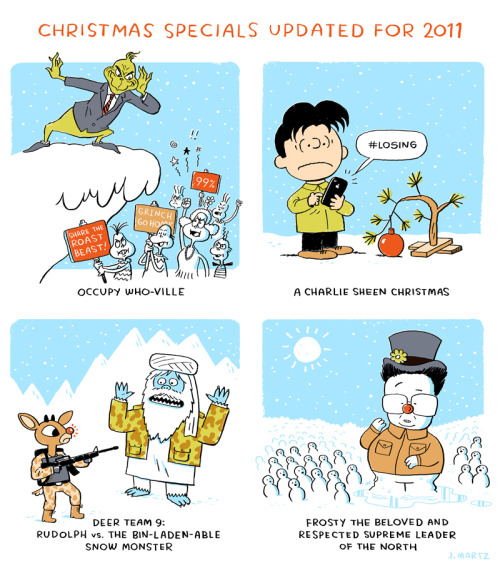

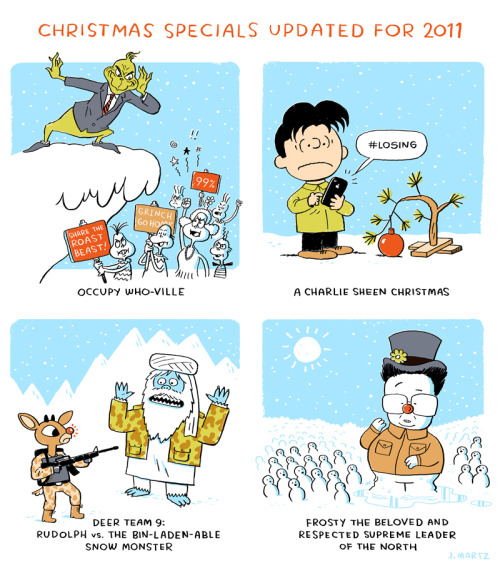

on 12/23/2011

Blog:

DRAWN!

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

christmas,

cartoon,

john martz,

rudolph,

specials,

grinch,

osama bin laden,

charlie sheen,

kim jong il,

Add a tag

Our beloved John Martz keeps hitting these strips out of the park. Merry Christmas, everyone!

johnmartz:

From the Globe and Mail, December 24, 2011.

By: Lauren,

on 5/4/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Events,

Middle East,

United Nations,

terrorism,

Military,

legal,

nato,

Al-Qaeda,

osama bin laden,

killing,

assassination,

*Featured,

Louis René Beres,

gaddafi,

michael scheuer,

international law,

Law & Politics,

gadhafi,

US,

Add a tag

By Louis René Beres

Osama bin Laden was assassinated by U.S. special forces on May 1, 2011. Although media emphasis thus far has been focused almost entirely on the pertinent operational and political issues surrounding this “high value” killing, there are also important jurisprudential aspects to the case. These aspects require similar attention. Whether or not killing Osama was a genuinely purposeful assassination from a strategic perspective, a question that will be debated for years to come, we should now also inquire: Was it legal?

Assassination is ordinarily a crime under international law. Still, in certain residual circumstances, the targeted killing of principal terrorist leaders can be defended as a fully permissible example of law-enforcement. In the best of all possible worlds, there would never be any need for such decentralized or “vigilante” expressions of international justice, but – we don’t yet live in such a world. Rather, enduring in our present and still anarchic global legal order, as President Barack Obama correctly understood, the only real alternative to precise self-defense actions against terrorists is apt to be a worsening global instability, and also escalating terrorist violence against the innocent.

Almost by definition, the idea of assassination as remediation seems an oxymoron. At a minimum, this idea seemingly precludes all normal due processes of law. Yet, since the current state system’s inception in the seventeenth century, following the Thirty Years’ War and the resultant Peace of Westphalia (1648), international relations have not been governed by the same civil protections as individual states. In this world legal system, which lacks effective supra-national authority, Al Qaeda leader bin Laden was indisputably responsible for the mass killings of many noncombatant men, women and children. Had he not been assassinated by the United States, his egregious crimes would almost certainly have gone entirely unpunished.

The indiscriminacy of Al Qaeda operations under bin Laden was never the result of inadvertence. It was, instead, the intentional outcome of profoundly murderous principles that lay deeply embedded in the leader’s view of Jihad. For bin Laden, there could never be any meaningful distinction between civilians and non-civilians, innocents and non-innocents. For bin Laden, all that mattered was the distinction between Muslims and “unbelievers.”

As for the lives of unbelievers, it was all very simple. These lives had no value. They had no sanctity.

Every government has the right and obligation to protect its own citizens. In certain circumstances, this may even extend to assassination. The point has long been understood in Washington, where every president in recent memory has given nodding or more direct approval to “high value” assassination operations. Of course, lower-value or more tactical assassination efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan have become a very regular feature of U.S. special operations.

There are some points of legal comparison with the recent NATO strike that killed Moammar Gadhafi’s second-youngest son, and his three grandchildren. While this was a thinly-disguised assassination attempt that went awry, the target, although certainly a supporter of his own brand of terrorists, had effectively been immunized from any deliberate NATO harms by the U.N. Security Council’s limited definition of humanitarian intervention.

It is generally

Like many other people around the world, I am trying to make my own sense about the recent news of the death and burial of Osama Bin Laden.

Upon hearing the news of the killing of Bin Laden, my first reaction was surprise. His name is a haunt from another time, suddenly recalled. His death noteworthy but not immediately meaningful.

As details came out, I felt conflicted. I am enormously proud of our US President Barack Obama who could decide on a priority and follow-through with it. Bin Laden was the master-mind behind the horrible attacks on the US that resulted in thousands of deaths. He was an enemy of all peace-loving people and needed to be brought to justice. But we have evolved from the days of the wild-west, I hope. We have trials and due process. Yet in seeking Bin Laden, the President’s poster might have read “Osama Bin Laden-wanted dead or alive.” And it did not seem likely that Bin Laden would ever have come willingly, so this priority, this determination to get Bin Laden would effectively be a death warrant.

The contrast with George W. Bush, our past president, and his “mission accomplished” was startlingly clear. He went after Saddam Hussein with the same kind of determination, using false claims to justify the use of US force against Hussein. But Hussein was eventually brought out alive, a desperate, mentally confused and physically ill man, but alive. He was tried for specified crimes. He was not the direct enemy of the US and had no part in the September 11 terror attacks, but he had committed crimes against his own people, had a trial, and was sentenced to death. For some of us, the death sentence is always wrong. We believe the decision for death is a decision that should belong to God or nature alone. But if we are going to defend death as a lawful element within our justice system, then certainly we must have the full panoply of justice rights at the least; certainly we must have a trial. We must have some compelling basis for the use of lethal force.

Despite the strong evidence against Bin Laden, there has been no trial. He was not picked off in the midst of threatening or terroristic activity, where our right to self-defense is imperative. He was hiding out in relative peace and comfort and then targeted and attacked in a quick and direct assault. This was an assassination, plain and simple. This was the US saying, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.

Even if his death can be defended as "justice," I am troubled by the exercise of US power to enter a foreign country and kill someone without official sanction or cooperation from the host country. Pakistan had insisted it is our ally in a fight against terrorism and particularly against Bin Laden and Al Qaida. Could the US imply consent to its actions from such political speech? Of course, the suspicion that Pakistani insiders would leak confidential information to aid Bin Laden’s escape again made sharing the covert operation in advance inadvisable. The immediate aftermath in which Pakistan officials claimed some share of the responsibility for the US’s mission seems like ratification of the US's use of power. Perhaps our entry into Pakistan for this mission is not a great abuse of power in light of all circumstances, although it feels like it crosses the line.

We buried his body at sea. This troubles me, more than anything. I am not so concerned about all those who will criticize our President with lies and accusations that we didn’t really kill the right man—there are always naysayers who deny the truth (like the Holocaust deniers) simply because it does not serve their political ends. But assurances that Bin Laden’s body was handled according to Muslim custom notwithstanding, was this our body to dispose of? Did we have the right to decide what to do with it? No doubt we did not want his body to become the subject of international debate; we did not want to see a shrine built on Bin Laden’s tomb with pilgrimages and homage. But

By: Michelle,

on 3/9/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Politics,

Current Events,

Middle East,

Afghanistan,

9/11,

terrorism,

colbert,

archive,

CIA,

colbert report,

osama bin laden,

The Oxford Comment,

oxford comment,

ben daniels band,

*Featured,

michael scheuer,

scheuer,

osama,

laden,

counterterrorism,

cia’s,

podcast,

Biography,

Add a tag

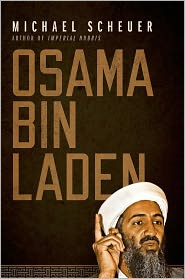

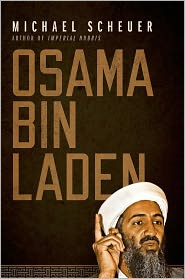

What does Osama bin Laden really want from us? Listen to this podcast and find out.

Want more of The Oxford Comment? Subscribe and review this podcast on iTunes!

You can also look back at past episodes on the archive page.

Featured in this Episode:

Michael Scheuer was the chief of the CIA’s bin Laden unit from 1996 to 1999 and remained a counterterrorism analyst until 2004. He is the author of many books, including the bestselling Imperial Hubris: Why the West is Losing the War on Terrorism (recommended by bin Laden himself). His latest book is the biography Osama bin Laden which he recently discussed on The Colbert Report (and this podcast!).

Michael Scheuer was the chief of the CIA’s bin Laden unit from 1996 to 1999 and remained a counterterrorism analyst until 2004. He is the author of many books, including the bestselling Imperial Hubris: Why the West is Losing the War on Terrorism (recommended by bin Laden himself). His latest book is the biography Osama bin Laden which he recently discussed on The Colbert Report (and this podcast!).

* * * * *

The Ben Daniels Band

By: Lauren,

on 3/2/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

newsweek,

muslim,

morrison,

CIA,

colbert report,

Al-Qaeda,

osama bin laden,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

michael scheuer,

scheuer,

colbertnation,

patt,

osama,

laden,

US,

Current Events,

Iraq,

stephen colbert,

Media,

Middle East,

Afghanistan,

Islam,

terrorism,

Military,

terrorist,

colbert,

Add a tag

Michael Scheuer was the chief of the CIA’s bin Laden unit from 1996 to 1999 and remained a counterterrorism analyst until 2004. He is the author of many books, including the bestselling Imperial Hubris: Why the West is Losing the War on Terrorism. His latest book is the biography Osama bin Laden, a much-needed corrective, hard-headed, closely reasoned portrait that tracks the man’s evolution from peaceful Saudi dissident to America’s Most Wanted.

Among the extensive media attention both the book and Scheuer have received so far, he was interviewed on The Colbert Report just this week.

Interested in knowing more? See:

0 Comments on Michael Scheuer sits down with Stephen Colbert as of 1/1/1900

By Alia Brahimi

The air freight bomb plot should be understood as part of al-Qaeda’s pervasive weakness rather than its strength. The intended targets, either a synagogue in Chicago and/or a UPS plane which would explode over a western city, were chosen as part of the attempt to re-focus al-Qaeda’s violence back towards western targets and pull the jihad away from the brink.

Indeed, things haven’t worked out the way Osama bin Laden hoped they would.

Quoting such diverse sources as Carl von Clausewitz, Mao Zedong, Vo Nguyen Giap and Peter Paret, al-Qaeda strategists had repeatedly emphasised the pivotal importance of attracting the support of the Muslim masses to the global jihad. For Abu Ubeid al-Qurashi, the absence of popular support meant that the mujahidin would be no more than a criminal gang. ‘It is absolutely necessary that the resistance transforms into a strategic phenomenon’, argued Abu Mus’ab al-Suri, time and time again.

However, despite the open goal handed to bin Laden by the US-led invasion of Iraq and the increased relevance and resonance of his anti-imperial rhetoric from 2003-2006, he failed to find the back of the net. His crow to Bush about Iraq being an ‘own goal’ was decidedly premature. The credibility of bin Laden’s claim to be acting in defence of Muslims exploded alongside the scores of suicide bombers dispatched to civilian centres with the direct intention of massacring swathes of (Muslim) innocents.

Moreover, where al-Qaeda in Iraq gained control over territory, as in the Diyala and Anbar provinces, the quality of life offered to the Iraqi people was a source of further alienation: music, smoking and shaving were banned, women were forced to take the veil, punishments for disobedience included rape, the chopping of hands and the beheading of children. Brutality was blended with farce as female goats were killed because their parts were not covered and their tails turned upward.

In the end, bin Laden’s ideology, which relied first and foremost on a (poetic) narrative of victimhood, became impossible to sustain. Bin Laden’s project is profoundly moral. He casts himself as the defender of basic freedoms. He eloquently portrays his jihad as entirely defensive and al-Qaeda as the vanguard group acting in defence of the umma. He maintains that all the conditions for a just war have been met.

In reality, however, all of his just war arguments – about just cause, right authority, last resort, necessity, the legitimacy of targeting civilians – are based on one fundamental assumption: that al-Qaeda is defending Muslims from non-Muslim aggressors. As such, it is essential that (1) al-Qaeda stops killing Muslims and (2) al-Qaeda starts hitting legitimate western targets and the regimes which enable the alleged western encroachment.

The emergence of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula in January 2009 can be viewed as part of this end (much as the al-Qaeda-affiliated GSPC in Algeria formed in opposition to the moral bankruptcy of the GIA). Their publications favour targeted violence such as political assassinations and attacks within US military barracks such as that perpetrated by Major Nidal Hasan at Fort Hood. Their most high-profile operations have been an assault on the US embassy in Sana’a, an attempt to assassinate the Saudi security chief Mohammed bin Nayef, and the bid by the ‘underpants bomber’ to blow up a flight from Amsterdam to Detroit.

In Yemen, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQIP) have internalised lessons from Iraq and are seeking to keep the population and the tribes on side. Their statements articulate the political and social discontent of the populace. The leadership seems to subscribe to bin Laden’s argument that violence must be used strategically and not w

Simon & Schuster’s Gallery Books partnered with indie comics publisher Bluewater Productions to create a graphic novel entitled Killing Geronimo: The Hunt for Osama Bin Laden.

Simon & Schuster’s Gallery Books partnered with indie comics publisher Bluewater Productions to create a graphic novel entitled Killing Geronimo: The Hunt for Osama Bin Laden.