new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Three Act Structure, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Three Act Structure in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

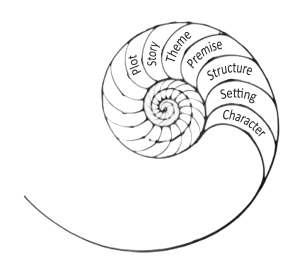

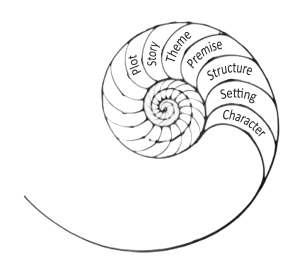

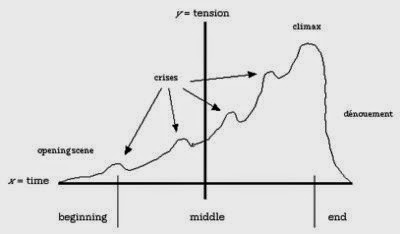

This is weird. For years I went by the standard Hollywood scriptwriting rule which says that the three act structure is god. As it was taught to me in my scriptwriting class and as I taught it to hundreds of students, in a standard drama act one finishes one quarter of the way in and act three begins one quarter before the end. There's also a midpoint where there's another not quite so pronounced change of direction or momentum.

I tested it out many times with my watch while watching movies and even when writing scripts, counting the number of pages in, to confirm that at these magical points the main plotline undergoes a major shift of direction or gear. Of course you all know this.

Plenty of stories do not quite conform to this rule (usually short or very long or episodic ones) and post-modern writers mess about with it. If there are many subplots or intertwining storylines there will also be distortion, but you can often pick apart these individual storylines and apply the same rule to them.

It's not as if this is deliberate. It seemed to be an intrinsic quality of the way the human mind appreciates the telling of a story and, correspondingly, the writing of one.

Now the novel I am principally engaged on right now has an unusual storyline: it is circular, so in principle has no beginning, middle or end. It's a story (and I don't want to give too much away) that I had been wrestling with how to tell since I first thought of the idea almost half a lifetime ago.

Many times I came to it, tried to write the opening pages and got nowhere. I put it down but it kept bothering me. I knew there was a really good idea in there somewhere. But because it was circular I couldn't get a handle on it, from a dramatic point of view. There were other issues: I needed to do research and at the time wasn't fully capable of it. Some stories have very long gestation period.

Sometimes when you are struggling with a problem like this you read another novel that is quite different and it can give you a sudden insight into your own story, and for me in this particular case it was reading

The Raw Shark Texts by Steven Hall which is a very curious book indeed. In case you haven't read it, it is about creatures which exist beneath the surface of a page when you are reading a book which have a life of their own and if you're not very careful they can devour you.

That's quite a powerful idea. It gave me another idea, also, I like to think, powerful. I put it into my mix.

The second new ingredient came from reading a non-fiction book,

The End Of Time by Julian Barbour, which argues that time does not exist – except in our consciousnesses. It's quite possible to describe the universe mathematically without recourse to time, he argues.

But if there is no time, how can a story have beginning, middle or end? In fact, how can there be stories at all? Logically, outside of our consciousnesses, stories are impossible. They do not exist 'out there'. We invent them to entertain each other and help ourselves remember stuff.

The third and final necessary ingredient for me to get a handle on my story was to determine the point of view. Up to then I did not have one, other than that of an omniscient narrator. It all fell into place when I realised that I needed a new character from whose perspective everything else was told. Once this had dawned on me, and I'd decided upon who that character was and his relationship to the other protagonists, the story could be written.

First I wrote the synopsis, then a long treatment. I needed to have it all plotted out because it was very complicated. Two years later I found the time to write the first draft and completed it by summer 2013. I left it for nearly a year and then completed the second draft last month.

I then thought I would try an experiment, and I looked at what happened precisely one quarter, one half, and three quarters of the way through the draft. Lo and behold, there were the plot points – in exactly the places where the theory said they should be.

How did this happen? I have a hypothesis, but that's all. Even though the story is circular I had to start it somewhere. Given that my narrator is deliberately telling the story for the benefit of another character in the novel, then the story begins at the most significant entry point for him. He then recounts the story until he reaches the point at which there is a suitable ending for him. This is just his perspective on the events.

Another character might have begun to describe the events at a different temporal point. Nevertheless I chose the character of the narrator, and therefore I am ultimately responsible for choosing where the novel starts to describe the circle of events, and it made total sense to start it there once I had made that choice.

I am incapable, however, of working out whether the final emergent structure is subconsciously imprinted into the novel because it is so deeply engrained in my own mind – as a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy – or whether it would have been there anyway. I know that I needed to establish the characters and the situation before the story could really take off, and I know that the pacing and dramatic intensity needed to increase as the narrative progresses. So I surmise that I had probably adopted the structure and these principles without deliberate intention.

It's vaguely satisfying to know that this happens automatically but also slightly disturbing. I have felt, at times, like dividing the chapters or episodes up and randomly shuffling them to see if anything interesting emerged from the new ordering, but intuitively I suspect that might be a waste of time. An interesting experiment nonetheless. Perhaps I still ought to do it.

I think Barbour is right, and time – therefore stories – do only exist in our minds. Story structure is a necessary consequence of consciousness because we cannot appreciate what comes later without knowing what has come before – whether the story is true, historical, or fiction. We also need to be made to care for the characters before we are motivated to turn the page.

We are prisoners of time and so bound to the logic of narrative. We seek beginnings, middles and ends even where there are none.

I wonder if any of you have similar experiences your own writing processes?

I am facing a difficult revision, not because I don’t know what needs to be done or that I can’t do it. It’s just that I’m not sure I agree with the critiquer wholeheartedly.

A novel revision has all sorts of questions attached:

Who are you revising for? One certain reader/editor? To connect with readers better?

For yourself? To become a perfect model book?

The critique of the manuscript was thorough and opinionated. I liked that. Here are some of their thoughts, which just represent one opinion:

- The theme being too didactic and preachy.

- The structure seems off: a major plot point takes place at the midpoint, but the critiquer suggested it should be at the end of Act 1 instead. That would also take care of pacing problem in the first half of the novel. That would mean I need an totally new Act 2.

- Characterization needs to be beefed up.

- The story line includes a curse; once under the curse the main character has difficulty distinguishing reality from fiction. The critiquer says SHE had trouble keeping things straight, too.

All of this sounds reasonable to me, until I start to write. Then I realize that I put that major plot point midway through the novel for good structural reasons. If I cut a lot and move it to the end of Act 1, well, what will I do for Act 2. It means a totally new story.

Who am I revising for? A reader who has an opinion, but do I agree with that opinion?

I agree that the characterization needs work. No problem there.

I am revising for the reader to make this work better.

If the critiquer had problems keeping things straight, that is a valid reader-concern. Clarity should rule for the reader, even when the main character is totally confused. I agree. I will revise for the reader.

The main question remains: reorganize the Acts/structure of the story and write a totally new Act 2. Who am I revising for?

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/8/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Novel Structure,

Three Act Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Plots,

Alternative Structures,

Designing Principle,

Classical Design,

Add a tag

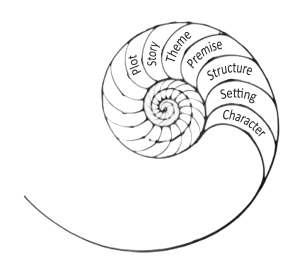

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

Happy plotting, structuring, and designing, everyone!

Organic Architecture Series:

Classic Design and Arch Plot:

Alternative Plots:

Alternative Structures:

Designing Principle:

Full Bibliography for this Series:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Anderson, Tobin. “Theories of Plot and Narrative.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt Inc., 1927.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Hawes, Louise. “Desire Is the Cause of All Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Kaufman, Charlie. “Charlie Kaufman: BAFTA Screenwriting Lecture Transcript.” BAFTA Guru. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 30 Sept. 2011. Web. 18 Aug. 2012.

Larios, Julie. “Once or Twice Upon a Time or Two: Thoughts on Revisionist Fairy Tales.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Layne, Ron and Rick Lewis. “Plot, Theme, the Narrative Arc, and Narrative Patterns.” English and Humanities Department. Sandhill Community College. 11 Sept, 2009. Web. 7 May 2011.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007. McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Sibson, Laura. “Structure Serving Story: A Discussion of Alternating Narrators in Today’s Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Tobias, Ron. Twenty Master Plots: And How to Build Them. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1993.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/8/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Novel Structure,

Three Act Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Plots,

Alternative Structures,

Designing Principle,

Classical Design,

Add a tag

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

Happy plotting, structuring, and designing, everyone!

Organic Architecture Series:

Classic Design and Arch Plot:

Alternative Plots:

Alternative Structures:

Designing Principle:

Full Bibliography for this Series:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Anderson, Tobin. “Theories of Plot and Narrative.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt Inc., 1927.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Hawes, Louise. “Desire Is the Cause of All Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Kaufman, Charlie. “Charlie Kaufman: BAFTA Screenwriting Lecture Transcript.” BAFTA Guru. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 30 Sept. 2011. Web. 18 Aug. 2012.

Larios, Julie. “Once or Twice Upon a Time or Two: Thoughts on Revisionist Fairy Tales.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Layne, Ron and Rick Lewis. “Plot, Theme, the Narrative Arc, and Narrative Patterns.” English and Humanities Department. Sandhill Community College. 11 Sept, 2009. Web. 7 May 2011.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007. McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Sibson, Laura. “Structure Serving Story: A Discussion of Alternating Narrators in Today’s Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Tobias, Ron. Twenty Master Plots: And How to Build Them. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1993.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

By Sheryl Scarborough

By Sheryl Scarborough

If the writer’s closet of useful tools could be likened to Carrie Bradshaw’s fabu walk-in, masterful accessories such as simile and metaphor would equate to exquisite Louboutin’s and Jimmy Choo’s footwear… exotic word choices would sparkle like Tiffany’s finest… and you would most likely find three-act structure in the drawer labeled: Spanx!

This is my way of saying Three-Act Structure may not be sexy, but once you try it, you’ll wonder how you ever lived without it. What exactly can Three-act structure do for you? I’m glad you asked.

- Simply organizing the main points of your manuscript into a structured beginning, middle and end will give you a comfortably shaped body of character, narrative and pace. (Spanx, baby!)

- Three-act structure streamlines the creative process, allowing you to focus on great dialog and important story points, not the organization of them. (When you’re busy being brilliant who wants to organize?)

- Which part of your story belongs in each act can be defined in enough detail that, once you learn it, you will never forget it. (Can you just give me the crib version? Yes. Read on!)

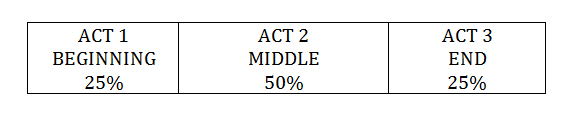

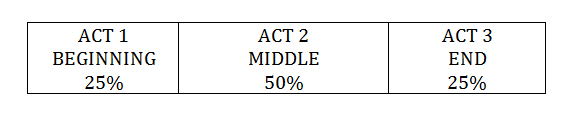

There are plenty of whole books, which define Three-Act structure and demonstrate how it works. For the purpose of this blog I’m just going to give you the basics. Three-Act structure is a specific way to balance and pace your story. The breakdown is simple:

Each Act encompasses a certain number of pages. This is the pacing part. Each act also plays a specific role in telling your story. This is the structure part.

In Act 1 the purpose is to introduce your characters and orient your reader to the setting and world you imagine.

Act 2 is where your story develops; this explains why it’s twice as long as Act 1 and Act 3.

Act 3 should be reserved for the exciting climax and conclusion of your story.

Act 1: Think of a Knight on a Quest…

Act 1 should answer WHO, WHAT, WHEN and WHERE… but not why. It should install your character in his world in a way that quickly orients your reader. Use Act 1 to identify your main character’s problems and introduce us to his friends and foes. Establish his goals and make us care about him.

If you’ve done your job, Act 1 is when your reader develops empathy with your main character. You need for this to happen… don’t blow it. The transition at the end of Act 1 is the point where your character commits to a course of action and your reader settles into her chair and thinks, “okay, here we go.”

Act 2: Facing the Two-Headed Dragon…

If Act 1 is a Quest, then Act 2 is a series of challenges… sort of like facing a two-headed dragon! In Act 1 your reader has learned WHO, WHAT, WHEN and WHERE. By the time she reaches Act 2 she wants to know WHY.

In Act-1 your job was to establish your character’s goal.

In Act 2.1, your job is to play keep away with that goal.

Just like in real life, adversity creates character. The goal of the first half of Act 2 is to throw a series of try/fail obstacles into your character’s path. With each test your character’s commitment becomes apparant. Each time he fails, you deepen his character and reveal more about him… this is how readers find out what he wants and needs and especially how invested he is in his goal.

Not only will your character come alive through these challenges, but as you raise the stakes your reader will become more involved, intrigued and invested in your story.

The length of the trial and error portion of your story is dictated by Three-Act structure. In the first half of Act 2 you are writing toward the mid-point, which is a mere 25% of your total story.

The Mid-point: It Changes Everything…

The Mid-point can be a down moment – the catastrophic end of your character’s goal. Or, it can be an up moment – a moment of shaky success that’s so tenuous and delicate your reader will be worried that this is just one more thing for the main character to lose.

Just remember, the purpose of the Mid-point is that it changes everything.

The Second Half of Act 2: Rebuild the Character’s Goal…

Depending on your Mid-point you have either destroyed your main character’s goal or you have pushed it to such a pinnacle that it is in jeopardy. In either case, the second half of Act 2 asks “now what” or “what now.” This is where you begin to rebuild your main character’s goal. To keep the reader intrigued you must keep the pressure on your main character. Achieving his goals should be hard and take real grit and determination. This is what keeps a reader in their seat.

You also want to begin to bring your storylines together in the last half of Act 2 so that you won’t crowd the climax and conclusion of your story with loose ends.

The End of Act 2: Your Character’s Darkest Moment

Pull out all the stops and really make this moment count. This is the low point your reader has been worried about for your entire novel. And now you must give it to them. Slam your story down on your main character with all the brutality you can muster and I guarantee your reader won’t be able to stop reading.

If you have built your story to this moment, the hopes and dreams that your reader has for your main character will carry them over the end of Act 2 and straight into the climax and conclusion. They won’t be able to put down your book.

Act 3: The Unexpected and Long-Anticipated…

“Act 3 begins with the unexpected and ends with the long-anticipated.“

Author, Ridley Pearson

What this means, is as you conclude your story, you want to make the ending as exciting and unexpected as possible… and yet you want to fulfill your promise to the reader and wrap up the story they expected you would tell. In most cases, your main character will achieve a satisfying goal – maybe not the goal he started out with, but one the reader will accept as a good conclusion to your story.

Example: staying with my Knight on a Quest theme, the end of my story should involve rescuing the Princess – or in my case – The Prince.

But don’t forget to keep an element of surprise… your reader will be working with you to create a successful conclusion to your story.

My surprise that my Knight was really my Princess will be all the more delicious to my reader.

Three-Act structure is writing with purpose!

For more information, check out some of these books that do a good job explaining Three-Act structure:

King, Vicki. How to Write a Movie in 21 Days. HarperCollins Publishers, 1993. Print.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: ReganBooks, 1997. Print.

Schmidt, Victoria. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest;, 2005. Kindle Edition.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat!: the Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City, CA: M. Wiese Productions, 2005. Kindle edition.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 3rd ed. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2007. Print.

Sheryl Scarborough learned Three-Act structure during her 20 year stint as an Award-winning writer for children’s television. Now, a recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in writing for children and young adults, Sheryl has turned her creative attention on writing young adult mystery/thrillers.

Sheryl Scarborough learned Three-Act structure during her 20 year stint as an Award-winning writer for children’s television. Now, a recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in writing for children and young adults, Sheryl has turned her creative attention on writing young adult mystery/thrillers.

Follow Sheryl on Twitter: @scarabs

Read more by Sheryl on her blog: Sheryl Scarborough Blog

The blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness Series.

By Sheryl Scarborough

By Sheryl Scarborough

If the writer’s closet of useful tools could be likened to Carrie Bradshaw’s fabu walk-in, masterful accessories such as simile and metaphor would equate to exquisite Louboutin’s and Jimmy Choo’s footwear… exotic word choices would sparkle like Tiffany’s finest… and you would most likely find three-act structure in the drawer labeled: Spanx!

This is my way of saying Three-Act Structure may not be sexy, but once you try it, you’ll wonder how you ever lived without it. What exactly can Three-act structure do for you? I’m glad you asked.

- Simply organizing the main points of your manuscript into a structured beginning, middle and end will give you a comfortably shaped body of character, narrative and pace. (Spanx, baby!)

- Three-act structure streamlines the creative process, allowing you to focus on great dialog and important story points, not the organization of them. (When you’re busy being brilliant who wants to organize?)

- Which part of your story belongs in each act can be defined in enough detail that, once you learn it, you will never forget it. (Can you just give me the crib version? Yes. Read on!)

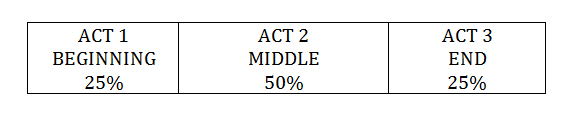

There are plenty of whole books, which define Three-Act structure and demonstrate how it works. For the purpose of this blog I’m just going to give you the basics. Three-Act structure is a specific way to balance and pace your story. The breakdown is simple:

Each Act encompasses a certain number of pages. This is the pacing part. Each act also plays a specific role in telling your story. This is the structure part.

In Act 1 the purpose is to introduce your characters and orient your reader to the setting and world you imagine.

Act 2 is where your story develops; this explains why it’s twice as long as Act 1 and Act 3.

Act 3 should be reserved for the exciting climax and conclusion of your story.

Act 1: Think of a Knight on a Quest…

Act 1 should answer WHO, WHAT, WHEN and WHERE… but not why. It should install your character in his world in a way that quickly orients your reader. Use Act 1 to identify your main character’s problems and introduce us to his friends and foes. Establish his goals and make us care about him.

If you’ve done your job, Act 1 is when your reader develops empathy with your main character. You need for this to happen… don’t blow it. The transition at the end of Act 1 is the point where your character commits to a course of action and your reader settles into her chair and thinks, “okay, here we go.”

Act 2: Facing the Two-Headed Dragon…

If Act 1 is a Quest, then Act 2 is a series of challenges… sort of like facing a two-headed dragon! In Act 1 your reader has learned WHO, WHAT, WHEN and WHERE. By the time she reaches Act 2 she wants to know WHY.

In Act-1 your job was to establish your character’s goal.

In Act 2.1, your job is to play keep away with that goal.

Just like in real life, adversity creates character. The goal of the first half of Act 2 is to throw a series of try/fail obstacles into your character’s path. With each test your character’s commitment becomes apparant. Each time he fails, you deepen his character and reveal more about him… this is how readers find out what he wants and needs and especially how invested he is in his goal.

Not only will your character come alive through these challenges, but as you raise the stakes your reader will become more involved, intrigued and invested in your story.

The length of the trial and error portion of your story is dictated by Three-Act structure. In the first half of Act 2 you are writing toward the mid-point, which is a mere 25% of your total story.

The Mid-point: It Changes Everything…

The Mid-point can be a down moment – the catastrophic end of your character’s goal. Or, it can be an up moment – a moment of shaky success that’s so tenuous and delicate your reader will be worried that this is just one more thing for the main character to lose.

Just remember, the purpose of the Mid-point is that it changes everything.

The Second Half of Act 2: Rebuild the Character’s Goal…

Depending on your Mid-point you have either destroyed your main character’s goal or you have pushed it to such a pinnacle that it is in jeopardy. In either case, the second half of Act 2 asks “now what” or “what now.” This is where you begin to rebuild your main character’s goal. To keep the reader intrigued you must keep the pressure on your main character. Achieving his goals should be hard and take real grit and determination. This is what keeps a reader in their seat.

You also want to begin to bring your storylines together in the last half of Act 2 so that you won’t crowd the climax and conclusion of your story with loose ends.

The End of Act 2: Your Character’s Darkest Moment

Pull out all the stops and really make this moment count. This is the low point your reader has been worried about for your entire novel. And now you must give it to them. Slam your story down on your main character with all the brutality you can muster and I guarantee your reader won’t be able to stop reading.

If you have built your story to this moment, the hopes and dreams that your reader has for your main character will carry them over the end of Act 2 and straight into the climax and conclusion. They won’t be able to put down your book.

Act 3: The Unexpected and Long-Anticipated…

“Act 3 begins with the unexpected and ends with the long-anticipated.“

Author, Ridley Pearson

What this means, is as you conclude your story, you want to make the ending as exciting and unexpected as possible… and yet you want to fulfill your promise to the reader and wrap up the story they expected you would tell. In most cases, your main character will achieve a satisfying goal – maybe not the goal he started out with, but one the reader will accept as a good conclusion to your story.

Example: staying with my Knight on a Quest theme, the end of my story should involve rescuing the Princess – or in my case – The Prince.

But don’t forget to keep an element of surprise… your reader will be working with you to create a successful conclusion to your story.

My surprise that my Knight was really my Princess will be all the more delicious to my reader.

Three-Act structure is writing with purpose!

For more information, check out some of these books that do a good job explaining Three-Act structure:

King, Vicki. How to Write a Movie in 21 Days. HarperCollins Publishers, 1993. Print.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: ReganBooks, 1997. Print.

Schmidt, Victoria. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest;, 2005. Kindle Edition.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat!: the Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City, CA: M. Wiese Productions, 2005. Kindle edition.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 3rd ed. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2007. Print.

Sheryl Scarborough learned Three-Act structure during her 20 year stint as an Award-winning writer for children’s television. Now, a recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in writing for children and young adults, Sheryl has turned her creative attention on writing young adult mystery/thrillers.

Sheryl Scarborough learned Three-Act structure during her 20 year stint as an Award-winning writer for children’s television. Now, a recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in writing for children and young adults, Sheryl has turned her creative attention on writing young adult mystery/thrillers.

Follow Sheryl on Twitter: @scarabs

Read more by Sheryl on her blog: Sheryl Scarborough Blog

The blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness Series.

by Maureen Lynas

WARNING! If you follow these steps you may never enjoy a book or film ever again. You may even experience marital and family discord.

Now read on.

Candy's post on the First Page Panel in Singapore reminded of an activity I attempted (and failed) years ago.

I'd just bought my very first 'how to' book - James Scott Bell's

fabulous and essential Plot and Structure. The

[…] First off, Ingrid Sundberg. Ingrid Sundberg is a fellow VCFA alum. She recently posted a fabulous series taken from her thesis on story architecture. If you only saw bits, or missed the whole thing, bookmark this page which includes the links for the entire series. Organic Architecture: Links to the Whole Series […]

Thank you for this marvelous and informative series! Bookmarking this page for future reference!

Thanks for this wrap-up! You did such an awesome job with this!!!

Thank you for this amazing series, Ingrid! I haven’t thanked you often enough, but yours is the one blog I always read.

You are awesome!

Very impressed by what you’ve managed to put together here.