new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: David Thorpe, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 15 of 15

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: David Thorpe in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Ever since 1962 when both Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and JG Ballard's The Drowned World (number one in his 'disaster quartet') were published, tens of thousands of non-fiction but perhaps only scores of fiction titles have addressed environmental and, specifically, climate change-related issues.

Ballard's quartet has been cited as an early example of 'climate fiction' or 'clifi', identified as a new label by the journalist Dan Bloom. Climate fiction specifically contains references to climate change. I interview Dan about it here.

I would say that there are perhaps more clifi books for children/teens than adults.

Ian McEwan's Solaror Margaret Atwood's Madaddam trilogy are examples of clifi for adults.

Love in the Time of Global Warming by Francesca Lia Block, Saci Lloyd's

The Carbon Diaries 2015,

The Ward by Jordana Frankel,

After the Snow by S. D. Crockett and Georgia Clark’s

Parched are examples of clifi books for older children. More are

here.

But can fiction ever change minds? Or does it merely confirm existing attitudes in the mind of the reader who chooses to read a book of that nature?

And are more clifi titles aimed at children because their enquiring minds are supposed to be more open?

These questions are thrown into relief by

research showing that logic and reason count for little in debates about the reality of climate change among adults.

Much clifi has concentrated on the destructive aspects of climate change, being variants of dystopian or disaster novels. New writer Paulo Bacigalupi, author of

The Water Knife, has even coined a new term: "accidental future" novels, i.e. novels that describe an unintended consequence of present human activity.

There is a greater challenge, however, that fewer writers are engaging in with fiction – although plenty have in non-fiction – and that is to create stories in which people successfully tackle climate change, devising solutions that rise to the challenges.

There are a few, beginning with Ernest Callenbach's

Ecotopia (1975) and Marge Piercy's

Woman on the Edge of Time. But can you think of any for children?

I believe it is essential that children are given hope that the future will not be necessarily full of catastrophe.

We should be empowering them. After all, so many children's books are supposed to do this, aren't they? "You can fulfil your dream. You can beat the bully. You can defeat the enemy."

But climate change is not something tangible or immediate, it is a vast and vague. It's scary and discouraging.

If we are to stimulate the imagination of the world's children so they do not feel hopeless and disempowered by the overwhelming scale and prospects of climate change, fiction must play a vital role in helping them envisage how they can successfully live in the future.

The winner of the Guardian Children's Book Prize 2014,

Piers Torday's The Last Wild is a good example of an environmental fable that gives hope, but it is not about climate change.

Such fiction might show children what a successful future could be like and even paint a picture of a good place to be in that is realistic and possible. A future where not only are children given a full part to play in society, but society itself is structured in a way that works with, not against, nature.

There are plenty of non-fiction books that do this but non-fiction is for specialists (planners, politicians, engineers, architects), and fiction, especially if translated into film, can be for the masses.

Fiction reaches places that non-fiction can never reach.

So, writers, how about it?

David Thorpe is the author of clifi YA fantasy Stormteller and the SF dystopia Hybrids.

What is it that distinguishes a book written for adults where children are the main characters and one written for children, where children are the main characters?

When I am writing for children or teenagers at the back of my mind is always this question of the difference between the two.

Here are the opening sentences of

In The Country of Men by Hisham Matar, which was shortlisted for the Man-Booker Prize and the Guardian First Book Award. The narrator is recalling a time when he was nine years old:

"I recall now that last summer before I was sent away. It was 1979 and the sun was everywhere. Tripoli lay brilliant and still beneath it. Every person, animal and and went in desperate search for shade, those occasional grey patches of mercy carved into the white of everything."

The novel describes the gradual discovery by the child of his father's involvement in anti-revolutionary activity and what this means, and his desperate love for his mother.

Here are the opening sentences of

The Bunker Diary by Kevin Brooks, which controversially won the Carnegie Medal in 2014:

"10.00 a.m."This is what I know. I'm in a low-ceilnged rectangular building made entirely of whitewashed concrete. It's about twelve metres wide and eighteen metres long. A corridor runs down the middle of the building, with a smaller corridor leading off to a lift shaft just over halfway down. There are six little rooms along the main corridor, three on either side."

Much has been written about Brooks' book and whether it is suitable for children, so I'm not going to stray into that territory. You might consider that I have chosen a non-typical example, but many children's books deal with uncomfortable themes and issues.

Both of these openings are physical descriptions which imply a sense of claustrophobia. They perfectly set the scene for what is to follow, which only gets worse.

The two books have several more things in common:

- there is no happy ending in either of them;

- very unpleasant things happen along the way;

- the main character is not conventionally likeable.

You can see other parallels from these extracts: the language in both is direct, the sentences straightforward. These stylistic points are undoubtedly a requirement for writing for children. But one can equally find instances of quite 'literary' writing in books for children, for example in the earlier novels of, say, Philip Pullman, such as

A Ruby in the Smoke.

The Bunker Diary deals with important psychological and philosophical themes, that are uncomfortable to contemplate. So does Matar's book.

One aspect which perhaps distinguishes

In The Country of Men (and other novels for adults) from most novels written for children is the retrospective angle: the narrator is now about 25 years old, and the narrative eventually catches up with him. This is less common in writing for children.

Another aspect that might signify a difference is non-linear storytelling, in which the narrative darts around in time. This is, again, less common in writing for children (however I did use this technique in my new novel Stormteller and, whilst I can't think of one at the moment, I'm sure I've read other children's books which do this).

The other observations to make about the difference between them are the setting (Gaddafi's Libya compared to contemporary London) and the degree of sophistication in the form of prior knowledge or experience that is assumed in the writing of Matar's book.

So to answer my original question, all other thngs being equal, the main aspect I am monitoring as I write for children rather than for adults is constantly gauging that level so it is pitched correctly.

I'd be very interested to know what you think about this topic?

David Thorpe is the author of Stormteller and Hybrids.

My first novel in several years is out this week – Like

Hybrids it's still YA, it's still set in the future, but it's very different in subject matter. I thought it might be interesting to talk about why I wanted to write it.

I lived in mid-Wales, where

Stormteller is set, for nearly 20 years. After separating from my first wife I eventually landed up in Taliesin, partly because I was attracted to a place named after Wales' legendary bard.

I know the landscape almost as well as I know my back garden now, having walked over much of it. I always felt when I moved to this edge of the British Isles from London that here, unlike most places, the skin of the present is thin: you can feel the vibrations from the past still reverberating down the centuries like thunder beneath your feet.

Just inland from Taliesin village is a collapsed dolmen that is given the name 'Taliesin's grave' – though it is much older than that.

Between my house at that time and the sea, lies Borth bog: you may remember the images in the media last winter when flames were leaping across it from burning peat despite the snow: spooky.

And then

Borth itself: a long sliver of a town that shouldn't be there, streamed onto a spur of land against the glint of the sea, on a section of coast that is the most vulnerable in the whole of Wales to storm surges. Again, it was in the media last winter when it was attacked by giant waves.

The spur continues to Ynys Las, a nature reserve of sand dunes opposite the Dyfi estuary from Aberdyfi – a colony of English retirees and yachting people largely immune to the influence of the past.

Above it, however, by the Bearded Lake, is allegedly a footprint left by King Arthur when he passed this way, and north of there the mountain Cader Idris, Welsh for

Seat of Arthur.

But the real stories that come from this area are older than Arthur's: the

birth of Taliesin and

Cantr'er Gwaelod, which is the tale of how the land that now lies beneath Cardigan Bay was drowned by the sea.

It's these, and the beautiful, wild and dramatic landscape, that sparked my imagination to write this novel.

Let me tell you the beginning of the first story: a mother had two children – a beautiful girl and a hideous boy with a hunched back. The girl wasn't a problem, she's not even part of the story, probably got married off to a Prince.

But the boy... the mother felt sorry for him. Perhaps the gift of wit and wisdom might make him popular so she could get him off her hands. So she laboured a year and a day to make a magic potion for him, but on the last day she left the servant boy, Gwion, in charge while she popped out. "Just stir: don't taste," she told him.

You can probably guess what happened next. The long and the short of it is that Gwion got to sample the potion and he received all the gifts intended for the son. He was the one who became Taliesin.

Nowadays, Taliesin is revered in Wales and beyond for his poetic and shamanic genius. But his talents should have belonged to someone else – the son, whose name is Afagddu. No one remembers him now, but Taliesin has a village and even an arts centre named after him.

So I thought: how would Afagddu feel? What would he want?

And this is a starting point for

Stormteller.

As a rebirthed baby, Gwion floated down the Dyfi river to Ynyslas where he was found by a local prince, who named him Taliesin. That leads into the second story....

...with a tragic ending – the flooding of the land – that it seemed to me has echoes of the threat that Borth and the whole coast of Britain faces now and in the future: rising sea levels, more storms and extreme weather caused by climate change.

We all feel threatened by

climate change. We feel powerless to do anything about it. So I wanted the novel partly to be about giving some degree of optimism. It's trying to look at the question of rewriting the endings of stories: ours – about climate change – and these two old legends.

It's easy to give into a sense of fatalism. I believe that we can all rewrite our stories, we at least have the power to do that. And this is true for the teenagers Tomos and Eira in the novel. But, as in life, there are always sacrifices to be made...

You can find out more about the

background to the novel here.

I had the pleasure last month of attending the Agents' Party at Foyles bookshop on Charing Cross Road, London, organised by the Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI).

It was called a party, but I'd say that's stretching the term; despite the free wine and nibbles, gratefully received, this was a place to pay full attention.

The agents attending were a good cross-section. Those on the panel were:

- Ella Kahn DKW Literary Agency

- Jo Williamson Antony Harwood Ltd

- Julia Churchill A.M. Heath Literary Agents

- Lauren Pearson Curtis Brown

- Penny Holroyde Caroline Sheldon Literary Agents

- Yasmin Standen Standen Literary Agency.

There were also other agents in the room:

- Alice Williams David Higham Associates

- Bryony Woods DKW Literary Agency

- Elizabeth Briggs LAW Literary Agents

- Eve White and Jack Ramm Eve White Literary Agent

- Hannah

Whitty Plum Pudding Illustration

- Louise Burns Andrew Mann Literary Agency.

In the assembly were up to 80 of us writers and illustrators. On the way in we were handed two badges to fill in and stick onto our clothing: one saying our name, and the other our favourite children's character.

I spotted at least one person who'd chosen a character from their own book. There's confidence for you.

Who did I choose? –

Skellig, the brilliant creation from David Almond's beautiful novel, a broken winged human found in a garden shed who, maybe, has miraculous powers. I thought he might bring me good luck.

Thus protected, I entered the airy new seminar room on the top floor of the wonderful new bookshop (they've moved a few doors down the hill away from the Crossrail engineering works. I went to the old bookshop first by mistake – shows how long since I was last there!)

(ASIDE: I remember the days when Foyles was completely disorganised, full of dusty piles of randomly assorted books that the overworked staff never got around to sorting out. If you wanted a book, it could take you days to burrow through them, like looking for a diamond in a snow drift, you'd have to take a whole week off work. While the old bookshop was definitely Dickensian, the new one is well into the 21st-century.)

Yes! There were a few familiar faces, very nice to see some old friends I hadn't seen for ages. (I confess I am a lapsed SCBWI-er, recently returned to the fold.)

So first of all there was a panel with Nick Cook as the ringleader, and lots of questions being asked about what agents are looking for, and how they make their choices, and then we could queue up to talk to them individually.

Here's what I took away from it:

In the younger age group, humour is popular and perhaps something with a strong literary bent. Others are looking for something more quirky, but above all they are looking for a powerful voice, something with attitude, strong and moving. Some of them were looking for a paranormal story, some for something with lots of twists.

Other keywords for older readers included dark, emotional, historical, with flow, written from the heart, and another interesting thing was said by Ella: "I know it's ready to be submitted to a publisher when I get lost in it".

That is really important in the context of answering the question: "When do I submit? – Either to a publisher or an agent". The answer is, don't send it in until you are absolutely sure it is ready for publication; is it in the form that you would like to see it in print? Because if it is, then the agent or editor receiving it will stop looking for mistakes and become absorbed, as if they were reading a book that had already been published.

And then all the agent has to do is send it straight off to their favourite editor. With absolutely no work for them. What could be better?

In connection with this, another piece of advice was: take your time. There's no rush to submit, not even when an agent gets back to you and suggests some changes. It's far better to get it right than to get right back.

That certainly good advice and probably the best thing I took away from it.

Website:

davidthorpe.info. My new book,

Stormteller, is out at the end of the month.

When I was starting out as a writer as a student and concentrating on comics I had a mental crisis that I wasn't going to make enough of a difference to the world just by writing comics.

But then I had a dream (while camping in the Bois de Boulogne, on the outskirts of Paris) which was very explicit. It said that if one person has their life changed as a result of something I write, then it would have been worthwhile.

Fine. So, eventually, I ended up working for Marvel comics, etc.

Then I started writing YA dystopias.

And I thought that by writing dystopias I was getting people to question the way the world was going and perhaps work for a better world. After all that's how it worked in my case. (I have parallel careers as an environmentalist and a writer.)

Then dystopias became two-a-penny.

And it turns out I was wrong. Firstly there's this

article which has just appeared in the Guardian Online, which appears to suggest that modern dystopic YA novel such as the

Hunger Games do nothing of the sort. This, despite the obvious satirical intention was partly a critique of mass entertainment.

I don't particularly agree with this critique, which also says that this book and

Divergent are right wing attacks on more egalitarian types of government. I think it's more than a little paranoid. I think it's more likely that readers only end up being sucked into the consumer market, instead of questioning it.

But here's something even more damning to the notion that by getting kids to read dystopic fiction we're helping to create a better world.

My friend George Marshall was researching his new book

Don't Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change and, because he is a comics fan, despite the fact that his book is about psychology, managed to wangle it that his research included going to the biggest comics convention on the East Coast, ComicCon. Well, of course.

In between looking for great graphic novels, he asked fans of dystopias what they thought the future will be like. He said: "My reasoning is this: These people are young, smart, and curious about technology and future worlds. They must have some good ideas."

But no. Marshall writes:

Brian Ferrara is selling nine-hundred-dollar replica weapons from science fiction video games. “I’m not a doomsday prophecy kind of guy, but I am a realist,” he says. So, being realistic, he doesn’t see a bright future, but he is very vague about the details. Maybe, he speculates, we will be immobilized, strapped to a chair with a feeding tube.

One couple are more politically alert, having spent time with the Occupy movement. They anticipate some kind of corporate dystopia, But, they say, there are other issues too. Overbreeding. The constant battle over fertility rights. “Yes,” says the woman, warming to the theme. “Politicians! Get out of my uterus! Leave my lady parts alone!” In her onepiece latex Catwoman outfit, she looks reasonably safe for the moment.

And climate change? In over twenty interviews, not one person mentions climate change until I prompt them to do so. Then they have lots of views. No one doubts that it is happening or is going to be a disaster. “It will escalate into catastrophe.” “If we can’t cope with that, we’ll all die like the dinosaurs.” But asked to identify when these impacts might hit, they reckon it’s still a long way off. “Maybe my great-grandchildren will have to deal with it,” Catwoman says.

It doesn't really prompt them to do anything about it. Except buy more comics.

So, I conclude, dystopias have become just another commodity, dealing out escapism. Which is a bit depressing, given that my next novel,

Stormteller, out next month, is a dystopia/fantasy about climate change.

Do you think your writing can change anything?

.jpg?picon=1806)

By:

David Thorpe,

on 8/3/2014

Blog:

An Awfully Big Blog Adventure

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

fairy tales,

nursery rhymes,

Angela Carter,

The Shadow,

Adventure Time,

David Thorpe,

Robert Bly,

the human shadow,

the subconscious,

Add a tag

Have you watched

Adventure Time? Maybe you have seen the comic or the graphic novel or some of the merchandise. It's a phenomenon, not least because of the age range it seems to appeal to. It is a show on the Cartoon Network, which the network claims tops its ratings and is watched by 2 million 2–11 year old boys – but I know many older kids, including students, who watch it avidly too.

When I first saw it I must admit I was surprised that something as violent, surreal and bizarre – and sometimes with such horrific and sexual content – was being aired for young children. It has a PG rating but that does nothing to keep it from young children's impressionable brains.

Here's a

list of extreme stuff you can find in it. It includes: "Lots of references to sex, ejaculation, viagra, sex-positions, sexual remarks and humor." And here's a

spoof web page parodying the reaction of the Christian right.

Disney it is not.

I think it's brilliant (but then I have a degree in Dada and Surrealism), and its freshness is perhaps partly because it's not written in the conventional sense (by a writer or writer team) but

produced by artists using storyboards that are then developed by a team, even going so far as deliberately to employ surrealist techniques such as the

Exquisite Corpse game in order to come up with ideas. It's also hand-drawn, each 11 minute episode taking 8–9 months to make.

Now:

"Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?" This was the line that introduced the American radio show

The Shadow in the 1930s (it later became a film, comic book series, etc etc). One answer is (besides the eponymous detective) – that children do. Children are far more preoccupied with questions about what adults call the dark side of human nature than many adults give them credit for. The best children's writers know this.

Adventure Time is therefore in the same ballpark as

Where the Wild Things Are...

... and the darkest of nursery rhymes and fairy stories....

... the kind that were explored by Angela Carter in her novels about growing up such as the

Magic Toyshop and the

Company of Wolves......stories where grandmothers turning to carnivorous beasts, the bedroom is populated by monsters, and the house next door contains versions of your own parents but with buttons for eyes (thanks, Neil)...

But it's also in the same ballpark as beautiful wonder-filled

Hayao Miyazaki films such as My Neighbour Totoro.

There is a genuine sense of beauty, spirituality and awe in many of Adventure Time's episodes or scenes, that is also shared by children who are viewing the world for the first time. It's as if the creators have been able to access their own infantile selves to identify with the way that children see the world.

My reference to The Shadow was chosen for another reason: the parts of the personality satisfied in its fans by Adventure Time and these other stories can be seen as parts of the 'shadow self', as described by the poet Robert Bly in his A Little Book on the Human Shadow.

The Jungian theory of the human shadow, itself part-derived from myths and old stories, is that babies and young children have what Bly calls a 360° personality. But much of this compass of human potential is socialised out of their behaviour during their upbringing. By the time they are around 20 years old just a slice remains. This is the socialised personality that becomes fixed as an adult.

The remaining portion is buried – the shadow – but it emerges in odd ways: our obsessions, the imaginary traits we project onto situations and other people, particularly our partners, the things we are frightened of, particularly in ourselves.

Bly says that after the age of 40 or so – the age of the midlife crisis – adults often start to unpack their shadow. Their reaction to this process determines the rest of the course of their lives.

The shadow is not bad, nor evil. Those are labels that adults put onto things. The shadow contains just what was suppressed, punished or ignored during the socialisation or upbringing process, and depends on the values held by the parents and the culture they belong too.

And this, I think, is why Adventure Time appeals to young adults as well as children. Young adults are struggling with those aspects of themselves which adults want to repress. In young adults there is a sense of nostalgia for their childhood self, that remains as a fading echo before the responsibilities of adulthood unkindly snuff it out altogether and they forget forever what being a child is like. They know this is going to happen, they regret it and they try to cling on to its last vestiges as long as possible.

The shadow is important, vital, necessary, and it is dangerous to repress it or ignore it. The makers of Adventure Time, and the Cartoon Network that commissions it, cannot be unaware of this. It is a liminal gate to the subconscious, the place where creativity thrives.

If I seem to be making rather grand claims for what is after all a children's cartoon I make no apologies. We all, as writers, are gatekeepers to this realm, aren't we? And each of us, in our own unique way, delves beyond the gate to do our work.

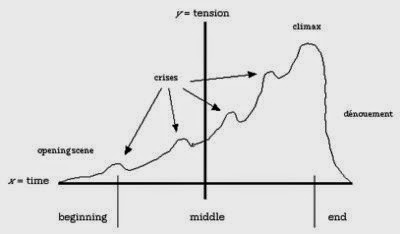

This is weird. For years I went by the standard Hollywood scriptwriting rule which says that the three act structure is god. As it was taught to me in my scriptwriting class and as I taught it to hundreds of students, in a standard drama act one finishes one quarter of the way in and act three begins one quarter before the end. There's also a midpoint where there's another not quite so pronounced change of direction or momentum.

I tested it out many times with my watch while watching movies and even when writing scripts, counting the number of pages in, to confirm that at these magical points the main plotline undergoes a major shift of direction or gear. Of course you all know this.

Plenty of stories do not quite conform to this rule (usually short or very long or episodic ones) and post-modern writers mess about with it. If there are many subplots or intertwining storylines there will also be distortion, but you can often pick apart these individual storylines and apply the same rule to them.

It's not as if this is deliberate. It seemed to be an intrinsic quality of the way the human mind appreciates the telling of a story and, correspondingly, the writing of one.

Now the novel I am principally engaged on right now has an unusual storyline: it is circular, so in principle has no beginning, middle or end. It's a story (and I don't want to give too much away) that I had been wrestling with how to tell since I first thought of the idea almost half a lifetime ago.

Many times I came to it, tried to write the opening pages and got nowhere. I put it down but it kept bothering me. I knew there was a really good idea in there somewhere. But because it was circular I couldn't get a handle on it, from a dramatic point of view. There were other issues: I needed to do research and at the time wasn't fully capable of it. Some stories have very long gestation period.

Sometimes when you are struggling with a problem like this you read another novel that is quite different and it can give you a sudden insight into your own story, and for me in this particular case it was reading

The Raw Shark Texts by Steven Hall which is a very curious book indeed. In case you haven't read it, it is about creatures which exist beneath the surface of a page when you are reading a book which have a life of their own and if you're not very careful they can devour you.

That's quite a powerful idea. It gave me another idea, also, I like to think, powerful. I put it into my mix.

The second new ingredient came from reading a non-fiction book,

The End Of Time by Julian Barbour, which argues that time does not exist – except in our consciousnesses. It's quite possible to describe the universe mathematically without recourse to time, he argues.

But if there is no time, how can a story have beginning, middle or end? In fact, how can there be stories at all? Logically, outside of our consciousnesses, stories are impossible. They do not exist 'out there'. We invent them to entertain each other and help ourselves remember stuff.

The third and final necessary ingredient for me to get a handle on my story was to determine the point of view. Up to then I did not have one, other than that of an omniscient narrator. It all fell into place when I realised that I needed a new character from whose perspective everything else was told. Once this had dawned on me, and I'd decided upon who that character was and his relationship to the other protagonists, the story could be written.

First I wrote the synopsis, then a long treatment. I needed to have it all plotted out because it was very complicated. Two years later I found the time to write the first draft and completed it by summer 2013. I left it for nearly a year and then completed the second draft last month.

I then thought I would try an experiment, and I looked at what happened precisely one quarter, one half, and three quarters of the way through the draft. Lo and behold, there were the plot points – in exactly the places where the theory said they should be.

How did this happen? I have a hypothesis, but that's all. Even though the story is circular I had to start it somewhere. Given that my narrator is deliberately telling the story for the benefit of another character in the novel, then the story begins at the most significant entry point for him. He then recounts the story until he reaches the point at which there is a suitable ending for him. This is just his perspective on the events.

Another character might have begun to describe the events at a different temporal point. Nevertheless I chose the character of the narrator, and therefore I am ultimately responsible for choosing where the novel starts to describe the circle of events, and it made total sense to start it there once I had made that choice.

I am incapable, however, of working out whether the final emergent structure is subconsciously imprinted into the novel because it is so deeply engrained in my own mind – as a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy – or whether it would have been there anyway. I know that I needed to establish the characters and the situation before the story could really take off, and I know that the pacing and dramatic intensity needed to increase as the narrative progresses. So I surmise that I had probably adopted the structure and these principles without deliberate intention.

It's vaguely satisfying to know that this happens automatically but also slightly disturbing. I have felt, at times, like dividing the chapters or episodes up and randomly shuffling them to see if anything interesting emerged from the new ordering, but intuitively I suspect that might be a waste of time. An interesting experiment nonetheless. Perhaps I still ought to do it.

I think Barbour is right, and time – therefore stories – do only exist in our minds. Story structure is a necessary consequence of consciousness because we cannot appreciate what comes later without knowing what has come before – whether the story is true, historical, or fiction. We also need to be made to care for the characters before we are motivated to turn the page.

We are prisoners of time and so bound to the logic of narrative. We seek beginnings, middles and ends even where there are none.

I wonder if any of you have similar experiences your own writing processes?

.jpg?picon=1806)

By:

Savita Kalhan,

on 6/4/2014

Blog:

An Awfully Big Blog Adventure

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

#ukyachat,

Loughborough University Literary Salon,

Teen Librarian Monthly,

The Edge blog,

Bali Rai,

The Long Weekend,

Savita Kalhan,

Maxine Linnell,

writing for teens/YA,

David Thorpe,

Add a tag

I was invited to take part in Loughborough University’s 2nd Literary Salon by Kerry Featherstone, lecturer in English. Industry professionals were invited: Walker Books and the literary agents from DKW, and another author – Maxine Linnell. The subject of the Salon was: Writing YA Fiction. We were each invited to speak, followed by a Q and A session, and, at the end of the evening, there was a Round Table. The audience comprised students, lecturers, authors and anyone in the local area interested in Teen/YA fiction. There was a great turn out and an interested and involved audience, with lots of discussions.

My talk focussed on the realities, good and bad, of being a children’s writer in the modern world, what an average advance might be, royalties, the changes in the publishing industry, and my experiences of being a teen/YA writer. I tried to give a balanced view on how difficult it is to make a living from writing, how a children’s writer today has to wear very many hats, know the industry and know how it works, while not neglecting the most important aspect of being an author: writing a book. I was a little surprised by how many students of creative writing were unaware of the realities of being a children’s writer.

I hope I didn’t put them off wanting to be writers!

The round table discussions focussed on various issues, including age banding in children’s books, the changing reading habits of children and teenagers, and diversity in children’s books. Bali Rai joined the round table and talked about how he and Malorie Blackman have been discussing the lack of diversity in children’s literature for many years, and how little has changed in that time. I’ve blogged about diversity in Teen/YA lit here on An Awfully Big Blog Adventure here and on The Edge Blog here, and for Teen Librarian Monthly here. Reading David Thorpe’s interesting post on yesterday’s blog, made me wonder about the diversity in the ethnicity of the children who had entered the 500 word story writing competition where 118,632 entries were received.

The round table discussions focussed on various issues, including age banding in children’s books, the changing reading habits of children and teenagers, and diversity in children’s books. Bali Rai joined the round table and talked about how he and Malorie Blackman have been discussing the lack of diversity in children’s literature for many years, and how little has changed in that time. I’ve blogged about diversity in Teen/YA lit here on An Awfully Big Blog Adventure here and on The Edge Blog here, and for Teen Librarian Monthly here. Reading David Thorpe’s interesting post on yesterday’s blog, made me wonder about the diversity in the ethnicity of the children who had entered the 500 word story writing competition where 118,632 entries were received.

The Literary Salon was a very good event for students who were interested in pursuing a career in writing. They got to meet a publisher, agents and writers, and to put questions to them. It was the kind of event I would have loved to have gone to when I first started writing and knew so little about the publishing world.

The Literary Salon was a very good event for students who were interested in pursuing a career in writing. They got to meet a publisher, agents and writers, and to put questions to them. It was the kind of event I would have loved to have gone to when I first started writing and knew so little about the publishing world.

|

| Book Trailer for The Long Weekend |

Savita Kalhan's website

hereSavita on Twitter

here

Who says today's children are being dumbed down? Who says the intelligence, literacy and creative ability is weakening compared to previous generations? (Could it be Michael Gove?)

I personally detest it when people put down children in this way. Any writer or teacher who goes out to meet kids in schools knows how smart they are. I believe that modern technology has made them far smarter than us oldies were at their age. They have a wider vocabulary and a much greater appreciation of the world, brought about by the broadened horizons made available by the Internet, games, books and a smörgåsbord of television channels. They probably also travel much more widely than we did 50 or more years ago.

All of this has had a marvellous effect. This is underlined by the results of BBC Radio 2's and the Oxford University Press' 500 words competition for children announced a few days ago, in which children had to compose an original work of fiction of 500 words.

They received a record-breaking, staggering 118,632 entries. Wow. Oxford University Press dictionary's team has analysed the stories to find out what words kids are using the most and the extent of their vocabulary, etc., all stuff that is of interest to us writers.

The most interesting thing first of all is the gender split. Girls outnumbered boys entering the competition by about 2 to 1. Three quarters of the entrants were in the 10 to 13 age range, the rest being nine and under. That probably means that girls in that age range are more likely to read books than any other children.

Now: how reassuring that the most common noun used in the stories is: 'mum'; and the most common adjective: 'good'.

Despite the fact that girls wrote twice as many of the stories, the main protagonist is more likely to be a boy. Now why do you think that is?

And the commonest name, used 27,321 times, is Jack, closely followed by Tom, Bob and James, all solid Anglo-Saxon names. I was certainly surprised to find that the most common girl's name is Lily/Lilly (17,981), closely followed by Lucy, then Emily and Sophie, also traditional English names.

And the most common historical figure? Adolf Hitler (used in 641 stories) followed by Queen Victoria (258).

I'd like to see Nigel Farage and his ilk use this as evidence for the insidious infiltration of multiculturalism into British culture. Actually it goes to show the opposite: there is no cause for concern, if anyone is concerned, that British culture is being watered down (although the research results are not accompanied by an ethnicity breakdown of the entrants to enable us to determine whether Celtic or Anglo-Saxon-originating Brits are unevenly represented amongst the entrants).

Looking at the keywords used in the stories, children were especially interested by this year's floods, with that single noun being by far the most commonly used (4008 uses), followed largely by non-real-world originating terms, coming from films and computer games: Lego, minion (used in Despicable Me), Minecraft and flappy (from the game Flappy Bird). Other words commonly used derived either from games or recent events such as the Winter Olympics.

What about new words? The research found that popular culture and social media have given rise to new verbs such as 'friended', 'Facebooked' and 'face-planted'. These will no doubt be finding their way into the next edition of OUP's children's dictionary.

Now for the really good news: children know - and are not afraid to use - really long words, including some that you or I may not even know: how about 'contumelious'? As used in the following context:

The girl springs to her feet losing all caution and apoplectic with outrage. "How dare you?" she cries, "Fighting them is bad enough, but capturing one to be slaughtered, as if it were a common boar, is contumelious. They will take their revenge and it will be terrible." (The War Party, girl, 13)

Or hands up who knows what '

furfuraceous' means? As used in:

Folkrinne's crown was placed on his furfuraceous head. The Basilisks applauded and cheered for the corrination of their new king of Malroiterre. (The Basilisk king, girl, 12)

(OK, so there was a spelling mistake in that, but I forgive this author because I think furfuraceous is a lovely word, conjuring up such a beautiful image in my mind).

And what about

making up words? Children are not afraid to do this because, as you and I know, it is so much fun. My favourite made-up word quoted from the stories is '

historytestaphobia' because I absolutely used to suffer from that when I was at school. I also love '

Mucaologist', which is apparently a collector of mucus.

Finally, telling stories is not just about the words you know but the order in which you put them, and these children seriously know how to

build suspense using perfectly ordinary words. As the report writers say:

If asked to write on a theme of mystery and suspense, one would not immediately think of the words door, house, step, and walk and yet the following example shows clearly how these words can be used to build suspense:

'Something had caught his eye. He turned around and saw an old, creaky house standing on its own in the middle of the woods. He took one step towards the scary house. He got closer and closer until he reached the house. Ben slowly walked up the cracked steps to reach the front door. Ben was scared out of his skin. Although on the outside he was brave. He pushed the rotten door and took a step inside the house.' (Haunted House, boy, 11)

All of this makes me happy, because it shows that there will continue to be a hungry audience for anything we writers produce, and, moreover, in a few years' time there will be more fantastically creative young adults ready to take our place.

Let's hear it for the kids.

.jpg?picon=1806)

By:

David Thorpe,

on 5/3/2014

Blog:

An Awfully Big Blog Adventure

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Neil Gaiman,

George Orwell,

comics,

Grant Morrison,

Judge Dredd,

2000AD,

Alan Moore,

Warren Ellis,

Pat Mills,

David Thorpe,

Paul Gravett,

Leo Baxendale,

Add a tag

The founding fathers would turn in their graves. The British Library is hosting an exhibition of publications in a medium once accused of undermining literacy, decency and the very establishment itself: comics.

I haven’t yet visited Comics Unmasked: Art and Anarchy in the UK, which has been curated by Paul Gravett, author of Comic Art, which I reviewed last month, but I have a shrewd idea of much of its contents because of my own involvement in the industry from the 1980s and ‘90s.

|

| Deadline 3 - which published Jamie Hewlett's Tank Girl |

Previously I’ve been

at pains to emphasise that comics are about much more than men in lycra, but we can’t ignore the lycra or the science fiction and fantasy, which is in strong evidence here. What deserves wide recognition, however, is the role of

attitude in providing the energy of iconoclastic creativity that has seen so many writers and artists whose target audience was originally children become internationally hugely influential.

British comics and their creators have an anarchic spirit. In the late nineteenth century the 'Penny Dreadfuls' were sometimes considered so subversive and dangerous to the Establishment (in fomenting an industrial dispute) that at one point printing presses used for printing them were destroyed by the authorities, as documented in Martin Barker’s book

Comics: Ideology, Power and the Critics.There is a direct line from these through Fleetway’s

Action comic to

2000AD, which in the late ‘70s and ‘80s saw the work of Pat Mills and John Wagner produce strips such as Nemesis the Warlock, which satirised corrupt organised religion, and

Judge Dredd, which satirised just about everything including a corrupt totalitarian state (although sometimes

Dredd seemed as though it was applauding the very summary dispensation of justice which it avowedly condemned).

Action was created in 1975 by Pat Mills for publishing house IPC. Soon banned for its violent content it nevertheless spawned

2000AD, the home of

Judge Dredd.

|

| Jamie's Tank Girl - whom he called a female Judge Dredd with bigger guns on speed. |

2000AD could have been deliberately designed to be the kind of left-wing comic imagined by George Orwell in

this fascinating article he wrote about the heavily middle and upper class boys’ comics like

Gem, Magnet, Hotspur, Wizard and so on.

These class-ridden, patriotic comics were produced by the ultra-conservative family-owned Scottish DC Thompson publishers, for much of the twentieth century - up until the days of punk rock as staple fare for boys, a deliberate antidote to the previous, anarchic Penny Dreadfuls. Orwell describes them in depth in the article and observes their propaganda value as follows:

“the stuff is read somewhere between the ages of twelve and eighteen by a very large proportion, perhaps an actual majority, of English boys, including many who will never read anything else except newspapers; and along with it they are absorbing a set of beliefs which would be regarded as hopelessly out of date in the Central Office of the Conservative Party.”

|

The cover of Revolver 1, which serialised Grant

Morrison's deconstruction of Dan Dare |

That aside, there is another ideological gradation that has Leo Baxendale’s

Bash Street Kids (also published by DC Thompson in the

Beano) and

2000AD at one end - produced by angry, anti-authoritarian working class writers and artists - and the middle class Frank Hampton’s neo-Imperialistic

Dan Dare at the other.

Common to both is the preoccupation with slapstick humour, fantasy and science fiction as a way of boggling minds and examining present-day trends taken to extremes.

Orwell himself notes the value of Sci-Fi (which he calls Scientifiction) in this fascinating sentence:

“Whereas the Gem and Magnet derive from Dickens and Kipling, the Wizard, Champion, Modern Boy, etc., owe a great deal to H. G. Wells, who, rather than Jules Verne, is the father of ‘Scientifiction’.”

You can even position later writers, influenced by these earlier names, on this spectrum, such as Alan Moore and Grant Morrison on the left, and Neil Gaiman more in centre-ground. Grant slyly subverted

Dan Dare himself , imagining him as an older man sadly looking back on the glory days of space empire in the pages of

Revolver in the late ‘80s.

The ‘80s was a key time, because it was then that the kids who had been brought up on the

Beano and

2000AD hit adulthood and it became cool to continue reading comics. Inspired by Moore’s

Watchmen and

V for Vendetta, and the American Frank Miller’s

Batman: Dark Knight Returns, younger artists and writers gave birth to an explosion of creativity.

|

The cover of Crisis issue 3 - probably the closest

ever to Orwell's dream of a left wing comic. |

|

Pat Mills' and Carlos Ezquerra's Third World War deliberately made

very cool heroes out of disabled, black, gay or female characters. |

Eight years after my own story in Marvel's

Captain Britain about the Northern Ireland Troubles was censored, Fleetway felt able to publish, in the overtly political

Crisis comic, Garth Ennis'

True Faith, (but even that graphic novel was scandalously withdrawn from sale, following complaints).

Crisis was largely Pat Mills' brainchild. Overtly political and radical it ran the amazing anti-American Imperialism strip

Third World War, which attacked CIA involvement in central and south American countries, a topic already tackled in comics by Alan Moore's and Bill Sienkiewicz's documentary graphic novel,

Brought to Light.

|

The cover of Doc Chaos 1 by me, Lawrence Gray and

Phil Elliott published by Escape |

Independent creator-owned comics sprang up all over the place, from my own satirical

Doc Chaos, published by Gravett's

Escape imprint, to

Deadline, from Brett Ewins and Steve Dillon, which came directly from a collision between comics and the new House music club culture, the true star of which was to become Jamie Hewlett's

Tank Girl. And most of us know what happened when Hewlett met Blur's Damon Albarn:

Gorillaz, the first band in history that was made up of comics characters.

|

Peter Stanbury's and Paul Gravett's Escape magazine

- beautifully designed, arty and hip. |

I must given a special mention to Don Melia and Lionel Gracey-Whitman for publishing

Aargh!, Heartbreak Hotel magazine with the supplement

BLAAM! Because the mere fact that this anti-homophobic publication could be a comic was testimony to how far the medium had come since the days of

Wizard and

Hotspur weekly comics in which homosexuality was a heavily suppressed element. Here is Orwell describing a cover image: “ a nearly naked man of terrific muscular development has just seized a lion by the tail and flung it thirty yards over the wall of an arena”.

|

| Heartbreak Hotel issue 5 cover by Duncan Fegredo |

|

| The first comic explicitly for black people, Sphinx |

|

| Repossession Blues from the pages of Blaam! |

|

A cover of chaos magick journal Chaos International

which shows the use of comics iconography

- the exchange of ideas went both ways. |

There was a huge amount of talent around in the ‘80s, much of which will be on evidence in the British Library show, but I find it fascinating that I, along with the far more successful Bryan Talbot, Grant Morrison, Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman, (particularly the first two) were also at the time heavily into chaos magick. We’d discuss this when we met occasionally at the bar that used to be at the foot of Centrepoint, near Titan Books’ offices where I worked, and Forbidden Planet bookshop, and at comics conventions.

Alan only went public on this more recently, but Grant overtly used his research in long-running strips such as the intensely surreal

Doom Patrol and subsequently

The Invisibles, both for DC.

It is not necessary to believe in any of the gods and forces invoked by magical ritual in chaos magick to utilise its effects. The point for all of us was that

Nothing is Forbidden, Everything is Permitted, to use Aleister Crowley’s mantra. Chaos magick provided an almost limitless kit of tools to access the far reaches of the imagination. I learned my tricks from a group that met every week in Greenwich, above Bulldog’s café, from the legendary Charlie Brewster, aka Choronzon 666.

I used this massive wellspring of creativity when writing

The Z-Men for Brendan McCarthy. Brendan was a maverick comics artist who started work in

2000AD, later becoming like many comics artists a film storyboarder, who was renowned for his psychedelic, mystical artwork.

All of us were also heavily influenced by Dada and Surrealism – this was the premier topic of my undergraduate degree. It is very obvious in Grant’s

Doom Patrol - just read my favourite story

The Painting That Ate Paris; and how else could you come up with a superhero who is an entire street (named - of course - Danny)?

|

Pure anarcho-comics: Hooligna Press & Pete Mastin's

Faction File collected from the pages of

squatting magazine Crowbar -

back full circle to the aims of the Penny Dreadfuls |

Arguably, the most successful comics writers working for American publishers in the ‘80s and ‘90s were Neil, Alan and Grant – Brits all. Frank Miller, also a giant, is American of course, and, while anarchic, is

sympathetic to the other end of anarchism – right wing libertarian, which approves the right to bear arms and use them against Commie radicals.

I attribute all of their success not just to their supreme storytelling abilities but to their political views and their involvement in anything occult, arcane and extreme, because in these genres of comics, what readers demand is out-there imagination – and it takes some serious head-space distorting tricks to cultivate a mind that can repeatedly and frequently, on demand, to a punishing production schedule, come up with the mind-boggling concepts, characters and storylines required.

These lessons were not lost on the more recent wave of massively successful British writers, such as Warren Ellis and Brian Hitch, the creators of

The Authority, (just read Warren Ellis'

Transmetropolitan for a taste of his brand of anarchy).

And I believe there are

lessons here for all writers and artists who aim at children and teens, that most demanding of all audiences, to help them feed and stoke the furnaces of creativity and imagination.

I could even attempt to sum them up in the following seven guidelines. Bear in mind that these are

methods I am suggesting, and in

no way am I advocating tackling a particular kind of subject matter. These are

ways of researching, preparing to write and draw, and of writing and drawing itself:

- Feed your mind with stuff from the far reaches of experience; and apply that to the everyday.

- You can’t be too extreme.

- JG Ballard's maxim: follow your obsessions.

- Never censor yourself – leave it to someone else.

- Boggle minds.

- Maximise drama.

- Above all - don’t take it too seriously.

Considering that I seem to be the only contributor to this site with an interest in comics I regard it as an obligation to pass on anything inspirational I come across to broaden the appeal of this amazing artform.

There are many books that acts as an introduction to comics and graphic novels. A new one has just come out that is a worthy contribution to this list. It's written by an old pal of mine, Paul Gravett, who has single-handedly carved out a unique career for himself as the British go-to expert on anything to do with comics and being called by The Times "the greatest historian of the comics and graphic novel form in this country", which is absolutely true.

The book is called, appropriately,

Comics Art, and published by Tate (the art gallery people, so it really is about art). The thing about this book is that you will hardly find any American Marvel or DC superheroes within its covers. And if you think that is all there is to comics, you're in for a big surprise. Even if you know Raymond Briggs, Hergé, Art Spiegelman and Marjene Satrapi as comics authors and artists you'll find a treasure trove of other gems herein.

Did you know, for example, that it took a panel of experts many days to decide together when the first comic was produced? The occasion was a comics festival in Italy in 1989, and the panel decided upon an issue of a newspaper strip from Sunday, 25 October 1896 in the

New York Journal called

The Yellow Kid, because, amongst its characteristics, was the

first use of speech balloons, together with a series of linear 'panels'.

This is a shame, because I thought I owned an earlier 'graphic novel', an English translation of

Mr Oldbuck's Adventures, dating from around the 1880s, but in this instance there are no word balloons, just pictures with a caption beneath them telling the story.

The book examines all the different ways in which artists have been and are continuing, particularly nowadays, to stretch the possibilities of a medium that has really come of age: trying to use visual imagery instead of language to convey emotions such as

Lighter Than My Shadow by Katie Green, about bulemia, messing around with associations, as with Seth's

George Sprott, or playing around with the subjectivity of time passing, as with

Pebble Island by Jon McNaught.

Paul is especially astute when analysing the political aspects, whether intended or not, of comics. For example, in a discussion of stereotypes in comics, he looks at ways in which comics have been used both to promote and to subvert stereotypical prejudices.

Perhaps the most courageous example of this is by Gene Yang, who challenged the offensive image of the buck-toothed Chinese stereotype and turned it to positive use as

Cousin Chin-Kee, a satire of "the worst racist prejudice".

Paul looks at graphic reportage such as

Ukrainian Notebooks by the Italian artist Igort, who spent months in that country unearthing stories about the famine engineered in 1932-3 by Stalin to enforce his farming collectivisation programme in which tens of thousands died. No wonder many Ukrainians now do not want to be part of Russia.

There has also been a massive trend recently for autobiography in comics which some feel has been overdone and itself has been subverted by a spoof autobiography (

Momon by Thomas Boivin et al. masquerading under the name Judith Forest).

Artists are still extending the vocabulary of comics. One of my favourite examples which Paul quotes is

Asterios Polyp by David Mazzuchelli, who not only introduces different typography and balloon shapes for different characters but messes around with different artistic styles for the characters at times in order to give further expression to their different points of view. Further, he deliberately limits his palate to blue and red (and their combinations) to enforce his creativity.

You can read

Comics Art just by looking at the pictures and obtain a fantastic overview of the sheer creative possibilities of comics for telling stories of every particular kind.

Comics are not a genre, they are a medium like the novel or the film, and every conceivable type of genre has been tried within the medium. They are peculiarly subjective, just like reading a book, but reaching out to more senses and more associations in the mind of the reader.

I first met Paul when we work together on a magazine with the unfortunate name of

Pssst! back in the early 80s: we were both on the editorial committee and I was a contributor. Later, with his and Peter Stanbury's

Escape imprint, he published some of my stories. Meanwhile he was amassing the most extensive library of graphic novels I have ever seen.

God knows how many he has now, but he has curated many shows and knows everybody who is anybody in the medium and industry, yet remains forever modest. This is a truly informative, inspiring and intelligent book.

.jpg?picon=1806)

By:

David Thorpe,

on 3/3/2014

Blog:

An Awfully Big Blog Adventure

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

World Book Day,

Roald Dahl,

Enid Blyton,

Matilda,

Thor,

Stan Lee,

secret identities,

David Thorpe,

Leo Baxendale,

Beano,

Add a tag

As writers spruce themselves up in preparation for entering schools on World Book Day in order to bear witness that there are - honest! - real people behind books, I've been thinking about what books I read when I was at primary-school age that really turned me on - and why.

There was a great public library down the road, and, like some kind of ravenous termite, I burrowed through titles as fast as I could: first, E. Nesbitt, Biggles, the Jennings books, Just William, the Famous Five, the Secret Seven, Swallows and Amazons, Robert Louis Stevenson and Peter Pan.

|

| Adults hated this. |

But reading these cost me nothing of my prized pocket money. If I cared about reading something enough to part with my precious cash, then I must have really wanted to read it, right? So what were these items?

Firstly, I'm almost ashamed to admit it now, but I bought the whole set of Enid Blyton's

Mystery Of... paperbacks, featuring the Five Find-Outers. These were 2/6d each (12.5p nowadays - nothing. But given that I had 6d a week pocket money that was quite a big deal!).

These books epitomise everything that is completely wrong, from an adult's point of view, about Enid Blyton, being badly written, with sterotyped characters, and containing a character called Fatty. None of that mattered to me of course.

Apart from being page-turning whodunnits, there were three important other elements that made them attractive to this 8 or 9-year old: the children knew best, they solved mysteries without adult help, and the authority figure - usually a policeman - was completely stupid. I suspect the latter reason is particularly why adults frowned upon Blyton. But you can't knock the fact that she published a staggering 752 books in her life. That must be some kind of record. Even if they did have names like

Noddy Loses His Clothes.

|

| Matilda - probably the best model reader in the world. |

There's something in the British psyche: Britons are well known for their sense of fair play combined with a healthy disrespect for authority. And I think I know why. Most children's books liked by children perpetrate the idea that children know best - and what is fair - and adults don't. Roald Dahl is the obvious example, just look at

Matilda.

Then, I'd buy the

Beano. Like thousands of other kids. You won't be surprised if I tell you that Leo Baxendale, whom I've had the pleasure to meet a few times, and who came up with the

Bash Street Kids and

Minnie the Minx, is an out and out anarchist and has been all his life. That's anarchist in the traditional British sense, going all the way back to the Levellers and Robin Hood.

|

| Leo Baxendale's Bash Street Kids: anarcho-punks in the making. |

He believed that property is theft to the extent that he eventually sued his publishers, DC Thompson, for not paying him any royalties despite the millions they were making from his work - and then settled out of court for an undisclosed sum to pay his mother's medical costs.

And I bought Marvel comics, whether imported or reprinted in the pages of comics

Wham!, Smash!, Pow!, Fantastic! or

Terrific! - hundreds of them, because they blew my mind with their sheer imagination. But in retrospect, I reflect that there was something else, something very special that made superheroes attractive to me - and to all kids who love them:

They have secret identities.

|

| Pure magic. My name is Thorpe. I WAS Thor! |

When bullied, persecuted Peter Parker became Spiderman, he left behind all of his troubles. When puny Bruce Banner transformed into the incredible Hulk, he could smash anybody. When the selfless and lame Don Blake hit his walking stick on the ground, it became Mjolnir, and he was the mighty God of Thunder, a noble Asgardian.

But all of these were secrets known only to themselves - and to me, the reader.

Stan Lee wrote all of these. He is a genius. Like Dahl, Blyton and Baxendale he knew how to create the equivalent of crystal meth on paper. Addictive or what?

These writers are not equal by the way. Today, I can't recall a single Blyton plotline. (And was she the first kids' writer to trademark her name as an instantly-recognisable signature? Is that part of her success - and should we all do this?) By contrast, very many of Stan the Man's stories and characters are burned into my brain. I'd say he was the most prolific of all these writers, and his inventions are the most successful (whether in terms of readership, sales or influence.)

Back to the subject of secret identities. It's not just that every kid longs to have special powers that could help them defeat their enemies (flying, super-strength, invisibility), it's that children have secret lives as well. For many grown-ups these secret lives are forgotten as they get older.

As a child I remember wondering why it was that adults seemed no longer to remember what it was like to be a child themselves, and vowed that I would do my best not to let the memory fade. I don't know whether I do - very well - but I certainly recall that feeling with great intensity.

The powerful idea that you have a secret self, with a special life known only to you, in which you accomplish remarkable deeds, heroic feats - and nobody else (adult) understands,

nobody must even know about this - is surely experienced by all children!

They are all, almost perpetually, engaged in one quest or another, one struggle, one battle, or one tumultuous adventure, whether it is emotional, adventurous, imaginative or intellectual. This is what's going on inside children's minds. All the time.

And this is what the best games, books, TV, films and so on both feed on, and feed into, in the fertile forming minds of children.

Always have. Always will.

I am lost in a forest of the night in a lucid nation. I awake, feeling uprooted. I find myself in a country deluded by surfaces.

Dawn offers its mechanical chorus. If I peel off the bark of the night it reveals a stark, blank-eyed whiteness.

Nothing is apparent of the frenzy within.

There was a crucial dream. It came when my life was at a junction, at University. I had nurtured a childhood fantasy: to be a writer; more specifically, of comics.

Yet, since then, the world's sicknesses had been displayed to me. Dismayed, I thought I ought to lend my life to healing them.

Torn by the thorns of this dilemma I took myself away, to Paris. I sought answers in its galleries.

In one, I witnessed, as if in another universe, a film of Max Ernst's surrealist collage novel, Une Semaine de Bonté.

I am not sure whether this is the version I saw, but the Schoenberg soundtrack is entirely appropriate (thanks, Helen). Originally published as a book, it can be argued that this is an early example of a graphic novel, and has influenced later comics writers, for example Grant Morrison, in particular his Doom Patrol

, as best exemplified by the story The Painting That Ate Paris.

Nothing could have seemed more shocking and disturbing. I was an intruder in another reality, feeling as one transported to ours from a foreign culture might feel.

I fell under its spell. Its alien logic, after a while, became as normal.

That night, under canvas on the hard ground of the Bois de Boulogne, I returned to my origin nation.

There, in a dust bowl, I met a famine-shrunken African boy:

...wrapped in torn pages from

Strange Tales 118.

|

| Stan Lee wrote both stories; Jack Kirby's dramatic pencils illustrated the first, where the Human Torch fought the Wizard with his anti-gravity discs. Steve Ditko's surreal line work on Dr Strange showed how, beneath surface reality, something sinister lurks. |

This was the first Marvel comic I ever read, as potent as a first cigarette.

I woke, convinced that the message conveyed was that: if I were to write comics, then, should one child's life be changed for the better from reading one of my stories, it would be worth my while.

Eight years later I found myself writing for Marvel comics.

|

| Taken from a recent issue of SFX magazine, containing an article on Captain Britain, including my stint on the title. |

Nowadays I find myself writing prosaic tips for combating climate change.

Yet nightly, I still bathe in the radiation from hidden worlds.

|

| Max Ernst's Europe After The Rain |

I plan to lose myself in those forests soon.

There is no writer alive who has never received a rejection slip. Or, probably, dead for that matter.

This is the test of fire; one you have to undergo time and time again. Because for every “Yes! We'd love to publish your book and give you a squillion pounds advance!" There are 100, or possibly 1,000 “Thank you for sending us your manuscript, but I am afraid it does not suit our requirements. We wish you the best of luck elsewhere".

There are several possible reactions to receiving a rejection letter:

Suicide:

Retiring to a monastery:

Falling into despair:

Taking the same manuscript around every agent and publisher in the world:

Looking again at the manuscript:

By the way, this is a page from the edited manuscript of George Orwell's

1984. Now there's a book I wish I had written.

Of the above options, my personal recommendation is for the fifth. I have tried two of the other four, but I'm not telling you which ones.

This is because, as everyone knows, persistence is the handmaiden of luck, which is the catalyst for success.

But being able to appraise and revise your own work objectively is a skill, and probably the most difficult part of writing.

Even more difficult than appearing on chat shows.

So here are my

top ten tips for revising a novel. (And by the way, I am talking mostly about novels for young adults.)

1. Go through it and look to see if

your viewpoint is consistent. If we are not following the action through one particular character's point of view, there must be a very good reason why. If you dart into another character's head or perspective, or find that you are giving your own description of a scene, during the same scene, steer it back to the primary viewpoint.

2. Are we as

close as possible to the feelings of the character? Are their feelings reported and described, or evoked and given? This is the difference between "She felt a jolt of shock" and

her shouting: "How dare she?" Don't distance the reader from the action and emotion; maximise the effect you are after.

3. Put it through a

cliché strainer. Hang the manuscript up in a net so that everything falls through the holes except the clichés. We all write clichés; they're a kind of shorthand put in at the first draft when you want to get on with the plot. Then, we don't always notice them later. Here's a list of some cliches I strained out of a recent novel:

‘makes a beeline for’ p8, ‘spot it a mile away’ p21, ‘stand out a mile’ p98, ‘head is reeling’ p22, ‘mouth falls open’ p22, ‘cold as ice’ p25, ‘knows it like the back of her hand’ p34, ‘coast is clear’ p109, ‘dead to the world’ p41.

What do you replace them with? Inspired images!

4. Apply a similar

filter for speech words. Really, the modern reader doesn't want to be held up in their appreciation of the plot by a variety of inappropriate speech verbs. Here is another list of mine, that you won't find in the latest draft of a novel:

‘trilled’ p9, ‘croaks’ p24 & p42, ‘breathes’ p45, p52, p88, p90 & p114, ‘laughs’ p46 & p89, ‘gushes’ p50, ‘giggles’ p71, ‘grins’ p76, p79 & p151, ‘weeps’ p82, ‘growls’ p88, ‘muses’ p94, ‘wheedles’ p111, ‘blurts’ p169 and ‘starts’ on p173.

5.

Check the pacing. If it feels like it's dragging, or you feel a bit bored at any point when you're reading it, cut it down. Be ruthless. Sometimes you find you have rushed where you should have taken your time to paint the scene a little. Throw in some nice imagery. Evoke that sense of place or person using all of the senses.

6.

Check the transitions. These are how a chapter ends and the next chapter begins. Each chapter should end with a cliffhanger of some sort to keep your reader up until four in the morning because they can't bear to put it down. In some way there should be a link with the beginning of the next chapter, but vary what kind of link it is. This could be a word echoed, or an image subverted. It could be similar in mood or theme, or violently contrasting. After a period of high tension, you probably want a light moment of humour, or take the opportunity to insert some vital information.

7.

Add emotion. Scare me. Shock me. Make me fall on the floor laughing. If there is any dramatic moment, make sure you have made the most of it. If there is any interesting concept, make sure you have explored it. But always do it from the point of view of your characters.

7. When you've done everything you can yourself,

pay an editorial critique service to do a professional job. It may cost £300 or so, but the business that does not invest in itself will lose out to one that does. And you are a business. You are serious about your success. Think you want to spend the money on a nice weekend at a writers' retreat? Or a glitzy conference where you rub shoulders with the famous? Fine, but do this first. You will learn far more from the detailed, specific, personal attention that you will get. Even if you disagree with it. And, you probably won't. Choose the service based on recommendation from other writers.

8.

Rewrite the beginning, then the end, then the beginning again, then the end again. Make sure that you match up the themes that you establish at the beginning at the end. Use similar imagery, for example. Make sure the opening is as arresting, direct, and suspenseful as possible.

I have learnt a lot by reading the opening three pages of bestsellers, and analysing how they achieve their effects.

9.

Print it out. Read it out loud. Reading it out loud will show up things you won't notice otherwise. Apply the

spelling filter and the

grammar filter at the same time. Don't rely on spell checks, do it properly yourself.

10.

Give it to someone else again to read. One more eye never hurts.

This is just my top 10. This list is by no means exhaustive although it might be exhausting. The perfect manuscript is an elusive creature that requires much patient nurturing to tame and train.

Of course, you will always think you did all of these things before you sent it away in the first place. The fact that you found loads of things to change means, quite simply, that you were wrong. And the reason is: you needed some time to get a fresh perspective.

Conspicuous in its absence on my list is:

11.

Take seriously any hints or advice contained in the rejection letter (if you were lucky enough not to get a standard letter).

This kind of goes without saying. But then again, I find that these letters are often written in haste, or perhaps not by someone who is particularly qualified, or contain only a general impression, not anything that is necessarily useful. Sometimes the reason given for the rejection is just an excuse thrown in and the real reason is totally different. In other words, it's not a technical response.

If, after all the above, your next draft is still rejected, then at least you will know that it's simply because the agent or editor concerned does not go for this particular type of work, or their list is already full for this category. It's not that it's not perfect!

Here is an extract from one rejection letter I had recently which illustrates just this approach:

“Should you write a comedy or another piece that has a little more light in the darkness, we'd be happy to consider it. You can clearly write."

Good luck. And by the way, if you want to compare the edited with the original version of 1984

have a look here.

May Big Brother always ignore you and your manuscript avoid Room 101.

www.davidthorpe.info

.jpg?picon=1806)

By:

David Thorpe,

on 8/5/2012

Blog:

An Awfully Big Blog Adventure

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

YA,

science fiction,

graphic novels,

e-books,

self-publishing,

Dave McKean,

print-on-demand,

Anne Rooney,

Rian Hughes,

Simon Bisley,

David Thorpe,

Add a tag

Are you e-experienced? Until a week ago I wasn't. But, in the last three weeks I have made and published my first e-book.

It feels a bit like giving birth to, I don't know, some kind of strange mutant mongrel beast, some hybrid child whose destiny is unknown, who may grow up to mock me, betray me, give me glory (but only by leave of the wayward capriciousness of viral flukeiness) or, even worse, disappear completely without trace in the infinitely absorptive sponginess that is the e-thernet.

Anyway, for what it's worth, I thought I would share my experience. Some of you may be teetering on the edge of this mysterious pool of brave new publishing opportunities, debating whether to take the plunge. I expect many of you already are e-experienced swimmers with Olympian credits. If so, you can poke fun at my ineptitude.

I kindled thoughts of these waters for a long while. Some of my books had been converted into ebooks by my publishers, but they were like the offspring of alcohol-obscured one night stands; unknown and unclaimed. The publishers didn't even tell me they had been born, I only found out by accident, and I don't have a clue about sales figures.

In a tentative way, I had previously offered PDF downloads of one or two stories or chapters for sale through my websites, but they had languished as forlorn and undownloaded as an unfertilised dandelion in a meadow of opium poppies.

I own no e-reader; nothing I cannot read in a bath without fear. Every work of fact or fiction in my library looks dissimilar from every other, and I like it like that.

What persuaded me to dip my sceptical toe in these waters was partly the persistent encouragement of a local publisher, Cambria Books, whose manager, Chris Jones, is passionate about their new business model.