A well-planned word wall allows students to quickly access familiar high frequency words from word study instruction. As they are writing, they can simply glance up, find the word, and continue to write. With… Continue reading ![]()

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: G.P. Putnams Sons, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 39

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: spelling, writing workshop, word study, word walls, Add a tag

Blog: Teach with Picture Books (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: vocabulary, spelling, game, phonics, Big Words, word work, ELA game, Add a tag

If you're looking for a game that students will beg to play every week, this is it. I've used it in classrooms and academic enrichment programs at summer camp with fantastic results. Add this to Bug and The Mysterious Box of Mystery, and you have three solid sure-fire games for your ELA toolbox.

Big Words is an activity which promotes an increase in phonetic awareness, spelling accuracy, and vocabulary development. The game I describe below was inspired by authors Patricia M. Cunningham and Dorothy P. Hall in their book Making Big Words. The copy I purchased over ten years ago encouraged me to turn their ideas into a class-wide game which has been a huge hit ever since.

The first objective of the game is to create as many words as possible from a given set of letters. To play, each student is given an envelope containing a strip of letters in alphabetical order, vowels listed first and then consonants. The student cuts these apart so that the individual letters can be easily manipulated on the desktop. Moving the letters about, students attempt to form as many words as possible. Beginners may only be able to form two-, three-, and four-letter words, but with time and practice will be able to use knowledge of word parts and blends to form much longer words.

The second objective is to spell a single word (the Big Word!) with all the letters. In my class, that Big Word very often relates to an upcoming trip, project, or special event, and thus serves double-duty to build excitement and enthusiasm.

As Big Words is used on a regular basis, the teacher can discuss strategies for increasing word counts. Some of these strategies include rhyming, changing single letters at the beginning or ending of each word, using blends, homophones, etc. Many additional words can also be generated through the use of -s to create plurals, and -e to create long vowel sounds. Some students will discover that reading their words backwards prompts additional ideas. Additionally, the teacher can discuss word parts which can help students to understand what they read (such as how the suffix -tion usually changes a verb to a noun, as in the word relaxation).

While the book emphasizes individual practice, we prefer to play Big Words as a class game. I've outlined our procedures below. You can also access these directions as a printable Google Doc.

BIG WORDS Game Play

- Have students cut apart the letters, and then begin forming as many words as possible using those letters. Remind them to not share ideas with partners, and to not call out words as they work (especially the Big Word).

- After about fifteen minutes, have students draw a line under their last word, and then number their list. They cannot add to or change their lists, but new words that they hear from classmates should be added once the game starts.

- Divide the class into two teams. Direct students to use their pencil to “star” their four best words which they would like to share. These should be words which the other team might not have discovered.

- Determine how the score will be kept (on a chalkboard, interactive whiteboard, etc.). The teacher should also have a way to publicly write words as they're shared so that students can copy them more easily. Here are links to a PowerPoint scoreboard or an online scoreboard.

- Hand a stuffed animal or other object to the first student from each team. This tangible item will help the students, and you, to know whose turn it is to share. Tell students that only the player holding the stuffed animal may speak. Other players who talk out of turn will cost their team one penalty point. These penalty points should be awarded to the opposing team, not subtracted from a score. This will greatly reduce unnecessary noise.

- Play takes place as follows: The first student shares a word, nice and loud. He or she spells it out. If any player on the opposing team has that word, they raise their hand quietly and the teacher checks to see that it is the same word. (It doesn't matter if any student on the speaker's team has the word or not). Every player who has it should check it off, and every player who does not have it should write it into their notebook.

- If no player on the opposing team has the word, then the team scores 3 points. If anyone on the opposing team has the word, then only 1 point is scored.

- If a player shares a word which has already been given aloud, their team is penalized 2 points! This helps everyone to pay better attention to the game.

- Ironically, the Big Word counts for as many points as any other word. Feel free to change that if you prefer, but I discovered that if I make it worth more points, students waste an extraordinary amount of time trying to form the Big Word alone, while ignoring the creation of any smaller words.

- Play until a predetermined time, and then if the Big Word hasn't been formed yet, provide students with the first two or three letters to see who can create it.

Blog: Teach with Picture Books (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: vocabulary, spelling, game, phonics, ELA, phonemes, Add a tag

Games are the most elevated form of investigation. ~ Albert Einstein

I just finished reading Cathy N. Davidson's wonderful Now You See It: How the Brain Science of Attention Will Transform the Way We Live, Work and Learn. I'll need to reread it, to be honest, because too often my mind began drifting to my own classroom as I read. I began asking myself if I was doing all that I could to engage students, and the answer was a sad and resounding no. My classes are severely lacking in game play.

According to Davidson, "Games have long been used to train concentration, to improve strategy, to learn human nature, and to understand how to think interactively and situationally." In the classroom, games capture and focus attention, increase motivation, and allow for complete, overt engagement.

My most often downloaded resource, in fact, is a Theme Game I created on Google Slides. At least one of my readers a day downloads this activity, which means that other teachers are seeing the value of game play in the classroom.

I readily admitted to my students that I created Bug, and it would have some, well, "bugs" that needed to be worked out. But students were eager to help in this regard, and our finished game is best described through the Google Slides presentation below.

What We Learned Together

1) We decided that certain modifications were allowed (simple switch, blend mend, one letter better) since they were sophisticated and advanced the game, while others were not allowed (adding a simple s to create a plural, adding both a vowel and a consonant together, reconstructing a word that has already been spelled). Students likewise dismissed the possibility of allowing prefixes and suffixes, deciding that those modifications didn't truly change the words enough.

2) We learned that four to five minutes was a suitable time for each round of play. Once each round finished, players could challenge their current partner if the match ended in a tie, or winners could challenge other winners and losers could challenge other losers, or, simply, anyone else could challenge any other classmate. Students didn't care whom they played; students simply wanted to play! My period one class of only eight students played using a traditional bracket to decide a final winner, but other classes were content to engage in free range play.

3) Students did begin to employ strategies. One clever student used "shrug" as her first word each time, instantly earning a power up and leaving her partner with a difficult word to manage. When her second partner countered with "shrub," this student needed to quickly adapt and used her earned power down to create "scrum." Scrum? Yes, this game encourages vocabulary development as well.

4) By game's end we concluded that, catchy name aside, every new game couldn't begin with "bug." Too many students were trying to play the same words each round, and too many rounds fell into the same predictable list of words. We decided that each new game should start with a different three letter word.

5) We played our games with large (12 x 18) paper and colored markers, but for a future game we're likely to play with standard sized paper and colored pencils. Students liked the visual separation that two colors provided, but the size format probably won't be needed in the future.

We would love to hear your recommendations, variations, and success stories!

Blog: Teach with Picture Books (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: vocabulary, spelling, game, phonics, ELA, phonemes, Add a tag

Games are the most elevated form of investigation. ~ Albert Einstein

I just finished reading Cathy N. Davidson's wonderful Now You See It: How the Brain Science of Attention Will Transform the Way We Live, Work and Learn. I'll need to reread it, to be honest, because too often my mind began drifting to my own classroom as I read. I began asking myself if I was doing all that I could to engage students, and the answer was a sad and resounding no. My classes are severely lacking in game play.

According to Davidson, "Games have long been used to train concentration, to improve strategy, to learn human nature, and to understand how to think interactively and situationally." In the classroom, games capture and focus attention, increase motivation, and allow for complete, overt engagement.

My most often downloaded resource, in fact, is a Theme Game I created on Google Slides. At least one of my readers a day downloads this activity, which means that other teachers are seeing the value of game play in the classroom.

I readily admitted to my students that I created Bug, and it would have some, well, "bugs" that needed to be worked out. But students were eager to help in this regard, and our finished game is best described through the Google Slides presentation below.

What We Learned Together

1) We decided that certain modifications were allowed (simple switch, blend mend, one letter better) since they were sophisticated and advanced the game, while others were not allowed (adding a simple s to create a plural, adding both a vowel and a consonant together, reconstructing a word that has already been spelled). Students likewise dismissed the possibility of allowing prefixes and suffixes, deciding that those modifications didn't truly change the words enough.

2) We learned that four to five minutes was a suitable time for each round of play. Once each round finished, players could challenge their current partner if the match ended in a tie, or winners could challenge other winners and losers could challenge other losers, or, simply, anyone else could challenge any other classmate. Students didn't care whom they played; students simply wanted to play! My period one class of only eight students played using a traditional bracket to decide a final winner, but other classes were content to engage in free range play.

3) Students did begin to employ strategies. One clever student used "shrug" as her first word each time, instantly earning a power up and leaving her partner with a difficult word to manage. When her second partner countered with "shrub," this student needed to quickly adapt and used her earned power down to create "scrum." Scrum? Yes, this game encourages vocabulary development as well.

4) By game's end we concluded that, catchy name aside, every new game couldn't begin with "bug." Too many students were trying to play the same words each round, and too many rounds fell into the same predictable list of words. We decided that each new game should start with a different three letter word.

5) We played our games with large (12 x 18) paper and colored markers, but for a future game we're likely to play with standard sized paper and colored pencils. Students liked the visual separation that two colors provided, but the size format probably won't be needed in the future.

We would love to hear your recommendations, variations, and success stories!

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: spelling, writing workshop, word study, Add a tag

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: The Teaching Channel, spelling, writing workshop, primary grades, Add a tag

How can we encourage our youngest writers to use brave spelling? How can we help them overcome their fear of getting it wrong?![]()

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: *Featured, Dictionaries & Lexicography, hameau, initial group dw-, Slavic mir, word origins, spelling reform, thresh thrash threshold, Books, Language, Oxford Etymologist, spelling, House, etymology, anatoly liberman, Linguistics, Add a tag

One month is unlike another. Sometimes I receive many letters and many comments; then lean months may follow. February produced a good harvest (“February fill the dyke,” as they used to say), and I can glean a bagful. Perhaps I should choose a special title for my gleanings: “I Am All Ears” or something like it.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for February 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Books, grammar, Language, Oxford Etymologist, word origins, spelling, oed, oxford english dictionary, etymology, anatoly liberman, monthly gleanings, *Featured, james murray, Dictionaries & Lexicography, John Vanbrugh, Word Origins And How We Know Them, Add a tag

As always, I want to thank those who have commented on the posts and written me letters bypassing the “official channels” (though nothing can be more in- or unofficial than this blog; I distinguish between inofficial and unofficial, to the disapproval of the spellchecker and some editors). I only wish there were more comments and letters. With regard to my “bimonthly” gleanings, I did think of calling them bimestrial but decided that even with my propensity for hard words I could not afford such a monster. Trimestrial and quarterly are another matter. By the way, I would not call fortnightly a quaint Briticism. The noun fortnight is indeed unknown in the United States, but anyone who reads books by British authors will recognize it. It is sennight “seven nights; a week,” as opposed to “fourteen nights; two weeks,” that is truly dead, except to Walter Scott’s few remaining admirers.

The comments on livid were quite helpful, so that perhaps livid with rage does mean “white.” I was also delighted to see Stephen Goranson’s antedating of hully gully. Unfortunately, I do not know this word’s etymology and have little chance of ever discovering it, but I will risk repeating my tentative idea. Wherever the name of this game was coined, it seems to have been “Anglicized,” and in English reduplicating compounds of the Humpty Dumpty, humdrum, and helter-skelter type, those in which the first element begins with an h, the determining part is usually the second, while the first is added for the sake of rhyme. If this rule works for hully gully, the clue to the word’s origin is hidden in gully, with a possible reference to a dupe, a gull, a gullible person; hully is, figuratively speaking, an empty nut. A mere guess, to repeat once again Walter Skeat’s favorite phrase.

The future of spelling reform and realpolitik

Some time ago I promised to return to this theme, and now that the year (one more year!) is coming to an end, I would like to make good on my promise. There would have been no need to keep beating this moribund horse but for a rejoinder by Mr. Steve Bett to my modest proposal for simplifying English spelling. I am afraid that the reformers of our generation won’t be more successful than those who wrote pleading letters to journals in the thirties of the nineteenth century. Perhaps the Congress being planned by the Society will succeed in making powerful elites on both sides of the Atlantic interested in the sorry plight of English spellers. I wish it luck, and in the meantime will touch briefly on the discussion within the Society.

In the past, minimal reformers, Mr. Bett asserts, usually failed to implement the first step. The first step is not an issue as long as we agree that there should be one. Any improvement will be beneficial, for example, doing away with some useless double letters (till ~ until); regularizing doublets like speak ~ speech; abolishing c in scion, scene, scepter ~ scepter, and, less obviously, scent; substituting sk for sc in scathe, scavenger, and the like (by the way, in the United States, skeptic is the norm); accepting (akcepting?) the verbal suffix -ize for -ise and of -or for -our throughout — I can go on and on, but the question is not where to begin but whether we want a gradual or a one-fell-swoop reform. Although I am ready to begin anywhere, I am an advocate of painless medicine and don’t believe in the success of hav, liv, and giv, however silly the present norm may be (those words are too frequent to be tampered with), while til and unskathed will probably meet with little resistance.

I am familiar with several excellent proposals of what may be called phonetic spelling. No one, Mr. Bett assures me, advocates phonetic spelling. “What about phonemic spelling?” he asks. This is mere quibbling. Some dialectologists, especially in Norway, used an extremely elaborate transcription for rendering the pronunciation of their subjects. To read it is a torture. Of course, no one advocates such a system. Speakers deal with phonemes rather than “sounds.” But Mr. Bett writes bás Róman alfàbet shud rèmán ùnchánjd for “base Roman alphabet should remain unchanged.” I am all for alfabet (ph is a nuisance) and with some reservations for shud, but the rest is, in my opinion, untenable. It matters little whether this system is clever, convenient, or easy to remember. If we offer it to the public, we’ll be laughed out of court.

Mr. Bett indicates that publishers are reluctant to introduce changes and that lexicographers are not interested in becoming the standard bearers of the reform. He is right. That is why it is necessary to find a body (The Board of Education? Parliament? Congress?) that has the authority to impose changes. I have made this point many times and hope that the projected Congress will not come away empty-handed. We will fail without influential sponsors, but first of all, the Society needs an agenda, agree to the basic principles of a program, and for at least some time refrain from infighting.

The indefinite pronoun one once again

I was asked whether I am uncomfortable with phrases like to keep oneself to oneself. No, I am not, and I don’t object to the sentence one should mind one’s own business. A colleague of mine has observed that the French and the Germans, with their on and man are better off than those who grapple with one in English. No doubt about it. All this is especially irritating because the indefinite pronoun one seems to owe its existence to French on. However, on and man, can function only as the subject of the sentence. Nothing in the world is perfect.

Our dance around pronouns sometimes assumes grotesque dimensions. In an email, a student informed me that her cousin is sick and she has to take care of them. She does not know, she added, when they will be well enough, to allow her to attend classes. Not that I am inordinately curious, but it is funny that I was protected from knowing whether “they” are a man or a woman. In my archive, I have only one similar example (I quoted it long ago): “If John calls, tell them I’ll soon be back.” Being brainwashed may have unexpected consequences.

Earl and the Herulians

Our faithful correspondent Mr. John Larsson wrote me a letter about the word earl. I have a good deal to say about it. But if he has access to the excellent but now defunct periodical General Linguistics, he will find all he needs in the article on the Herulians and earls by Marvin Taylor in Volume 30 for 1992 (the article begins on p. 109).

The OED: Behind the scenes

Many people realize what a gigantic effort it took to produce the Oxford English Dictionary, but only insiders are aware of how hard it is to do what seems trivial to a non-specialist. Next year we’ll mark the centennial of James A. H. Murray’s death, and I hope that this anniversary will not be ignored the way Skeat’s centennial was in 2012. Today I will cite one example of the OED’s labors in the early stages of work on it. In 1866, Cornelius Payne, Jun. was reading John Vanbrugh’s plays for the projected dictionary, and in Notes and Queries, Series 3, No. X for July 7 he asked the readers to explain several passages he did not understand. Two of them follow. 1) Clarissa: “I wish he would quarrel with me to-day a little, to pass away the time.” Flippanta: “Why, if you please to drop yourself in his way, six to four but he scolds one Rubbers with you.” 2) Sir Francis:…here, John Moody, get us a tankard of good hearty stuff presently. J. Moody: Sir, here’s Norfolk-nog to be had at next door.” Rubber(s) is a well-known card term, and it also means “quarrel.” See rubber, the end of the entry. Norfolk-nog did not make its way into the dictionary because no idiomatic sense is attached to it: the phrase means “nog made and served in Norfolk” (however, the OED did not neglect Norfolk). Such was and still is the price of every step. Read and wonder. And if you have a taste for Restoration drama, read Vanbrugh’s plays: moderately enjoyable but not always fit for the most innocent children (like those surrounding us today).

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for November 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: spelling, writing workshop, Add a tag

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: spelling, writing workshop, Add a tag

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: beta readers, links, grammar, book marketing, spelling, author website, Add a tag

This month-long series of blog posts will explain author websites and offer tips and writing strategies for an effective author website. It alternates between a day of technical information and a day of writing content. By the end of the month, you should have a basic author website up and functioning. The Table of Contents lists the topics, but individual posts will not go live until the date listed. The Author Website Resource Page offers links to tools, services, software and more.

Calling All Grammar Witches: Beta Readers for Your Site

You’re just days away from launching your new and improved Author Website. Now’s the time to proofread, test links and make sure everything is working! Recruit friends (and enemies?) to click around and make sure the site works.

- Links. Click on every single link to make sure it works.

- Grammar and Spelling. Grammar Witches, i love you. I’ll do everything you tell me to do.

- Photos. Add photos to every page, because it makes it more appealing.

- Tweak posts. OK, you’re a writer. You will be tweaking every single post. Just don’t stress out over this; write the best you can and let it go.

Fix everything that is reported to you. Make sure everything is in order for launch.

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: grammar, style, copy edit, spelling, novel revision, chicago manual of style, Add a tag

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Start Your Novel

by Darcy Pattison

Giveaway ends October 01, 2013.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

I had to laugh this week when I got a spam email with the title, “Loose 8 Ponds Quickly!” Wow, did this spammer need a copy editor.

A copy editor finds all the pesky little errors of grammar and spelling. Many publishers use the Chicago Manual of Style as their style guide. Because here’s a secret they don’t teach in high school: grammar and to an extent spelling, is a matter of convention. Grammar is an agreed-upon set of rules for how we punctuation, conjugate and parse our language. There are different style guides and each has slightly different rules. And the language is evolving.

For example, I heard recently that quotation marks as a way to indicate speech are being disregarded in some new publications. That doesn’t make sense to me! I’m conventional. But for an edgy YA novel, maybe it would draw in a few new readers, which is language in the service of the story.

Do you need to study the Chicago Manual of Style? It wouldn’t hurt; but it’s unlikely that most writers need to do that intensive study. You do need a solid grounding of grammar, though. Unless your character is uneducated, speaks in a dialect, or is sick, s/he should speak in standard English. If you can’t manage that, then you should take a class somewhere.

I recently read a story that started, “Because him and his whole family were going out to do some camping.”

Wow. Embarrassing. Here’s how to keep from being embarrassed.

Spell Check. I’ve been lax lately about running a spell check on everything that goes out. But I was recently embarrassed by an obvious spelling error and it jerked me back to reality. Everyone can make mistakes, so you should use the tools available to write as cleanly as possible. Use your word processor’s spell check! Then run over it again to catch things like he/eh, for/four/fore, their/there, etc.

Grammar Check. Likewise, run your word processor’s grammar check. Always.

Study E.B. White’s Elements of Style. If you constantly find yourself mixing up things like for/four/fore or loose/lose, then you need to brush up on your skills. White’s book has a long list of easily confused words and is a handy reference. Or try the variations on this classic, Elements of Style: Illustrated, or The Elements of Style: Updated for Present-Day Use.

Use the online Chicago Manual of Style. Not sure what word usage is correct or how to punctuate something? Use the online Chicago Manual of Style to answer all questions.

Want to go farther and test the limits? OK. Once you know the standards, feel free to play. Here are some helpful books.

Eats, Shoots, and Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation

Eats, Shoots, and Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation It Was the Best of Sentences, It Was the Worst of Sentences

It Was the Best of Sentences, It Was the Worst of Sentences The Elephants of Style: A Trunkload of Tips on the Big Issues and Gray Areas of Contemporary American English

The Elephants of Style: A Trunkload of Tips on the Big Issues and Gray Areas of Contemporary American English

Spunk and Bite

Spunk and Bite

What are your favorite grammar and style books?

And what standard grammar rules are being challenged by contemporary publishing?

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: cathy butler, initial teaching alphabet, spelling, Add a tag

Blog: Schiel & Denver Book Publishers Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Spelling, Add a tag

Open, hyphenated, or closed? Usage guides, dictionaries, and style manuals may differ in their treatment of the following words, so there’s not necessarily one right answer — except for the purposes of this exercise: Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. All terms in this list are treated as open compounds. Which ones should be left as is, and which should be hyphenated or closed, and in which usages? The correct forms according to Merriam-Webster are listed at the bottom of the page.

1. Air borne

2. Anti social

3. Audio visual

4. Back log

5. Blood pressure

6. Book keeping

7. Bull’s eye

8. By law

9. Catch all

10. Check book

11. Child like

12. Clearing house

13. Court martial

14. Crew neck

15. Cross reference

16. Dog sled

17. Father land

18. Far reaching

19. First hand

20. Free style

21. Freeze dried

22. Fresh water

23. Go between

24. Great uncle

25. Half brother

26. High school

27. Higher ups

28. House hold

29. Inter agency

30. Key word

31. Jewel like

32. Land mass

33. Life size

34. Light year

35. Long term

36. Lower case

37. Main frame

38. Mass produced

39. Mid week

40. Mother ship

41. Multi purpose

42. Near collision

43. North west

44. Off shore

45. On site

46. Over supply

47. Pine cone

48. Pipe line

49. Policy maker

50. Post war

51. Pre existing

52. President elect

53. Pro life

54. Pseudo intellectual

55. Quasi realistic

56. Real time

57. Record breaker

58. River bed

59. Sea coast

60. Self control

61. Semi final

62. Shell like

63. Six pack

64. Snow melt

65. Socio economics

66. Step mother

67. Stomach ache

68. Strong hold

69. Toll free

70. Two fold

71. Under water

72. Vice president

73. Wild life

74. World wide

75. Year round

Answers

1. Airborne

2. Antisocial

3. Audiovisual

4. Backlog

5. Blood pressure (in the dictionary, so never hyphenate, except when combined with another adje

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Oxford Etymologist, word origins, spelling, etymology, anatoly liberman, *Featured, Lexicography & Language, kn sound, mb sound, oddest english spellings, silent b, silent k, Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman In those rare cases in which people ask my advice about good writing, I tell them not to begin (to not begin?) their works with epigraphs from Mark Twain or Oscar Wilde, for the rest will look like an insipid anticlimax, and, disdainful of ground-to-dust buzzwords and familiar quotations, I also suggest that people avoid (naturally, like the plague) such titles as “A Tale of Two Friendships/ Losses/ Wars,” etc. and resist the temptation to

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Old English, modern english, monthly gleanings, english literature, *Featured, Lexicography & Language, learning english, misspelling, teetotal, Reference, words, Oxford Etymologist, Dictionaries, word origins, spelling, dictionary, anatoly liberman, Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Question: How large is an average fluent speaker’s vocabulary?

Answer: I have often heard this question, including its variant: “Is it true that English contains more words than any other (European) language?” The problem is that “an average fluent speaker” does not exist. Also, it is important to distinguish between how many words we recognize (our so-called passive vocabulary) and how many we use in everyday communication (active vocabulary). The size of people’s active vocabulary depends on their needs, but it is rarely large. Thus, five-year olds can say everything they want, but if they are read to and if grownups speak to them all the time, they understand complicated tales and the content of their parents’ conversation amazingly well (oftentimes much better than one could wish for). Some people cultivate their conversational skills and make an effort to use “sophisticated” words in their dealings with the outside world; others are happy to remain at the level of first-graders. One of the most memorable events in my teaching career happened about thirty years ago when a student approached me after a lecture and, having complimented me (they always do in such cases), added: “But I don’t understand half of the words you use.” Ever since that day I have worked systematically on reducing my “public” vocabulary but sometimes still forget myself.

Our passive vocabulary depends on our reading habits. Since “great classics” are being frowned upon as elitist, the younger generation has trouble understanding even 19th-century English (Jane Austen, Dickens, Thackeray, and so on, through Henry James and the utterly forgotten Galsworthy), while publishers promote books written more or less in Basic English. Students get tired of following those authors’ synonyms, idioms, and convoluted syntax (their greatest compliments are matter of fact and down to earth, while all digressions are castigated as rambling). The same is true, to an even greater extent, of their attempts to read Defoe, Fielding, and Swift. For some Americans of college age even the vocabulary of Mark Twain poses difficulties. It is hard to believe that Mark Twain, like Jack London and Charles Dickens, was self-taught. Yet quite a few of our best and brilliantly educated writers did not make use of an extensive vocabulary. Oscar Wilde is a typical example. Others, like Dickens and Meredith, let alone James Joyce, made a heroic effort to use as many rare and learned words as possible.

Good dictionaries of English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Swedish, etc. seem to be equally thick. In a dictionary containing about 60,000 words one can find practically everything one needs. Webster’s Unabridged features seven or eight times more. Obviously, none of us needs to know so much. But perhaps two features distinguish English from its neighbors: an overabundance of synonyms (because of the partly unhealthy influx of Romance words) and the ubiquity of slang. French also overflows with argot, but English dictionaries of slang (British, American, Canadian, Australian) are almost unbelievably thick. This makes it harder to master current English than, for example, German, but each language has its difficulties. English resorts to all the usual international words (music, radio, antibiotic, and the like), while Icelandic prefers native coinages for such concepts. It appears that whether you want to learn a foreign language or your own you have to make a sustained effort. But then this is what the sweat of one’s brow is for. Only Adam had an easy life: none of the objects around him had a name, and he was instructed to call them something (presumably he remembered his own neologisms). His offspring ca

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Oxford Etymologist, jewish, word origins, spelling, yiddish, etymology, anatoly liberman, jack london, *Featured, Lexicography & Language, east end, highfalutin, Reference, Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Allegedly a nineteenth-century Americanism, highfalutin is now known everywhere in the English speaking world, but, as could be expected, its etymology has not been discovered—“as could be expected,” because the origin of such words is almost impossible to trace. Many years ago, while investigating the history of skedaddle, I think I found a reasonable source of this verb. I was neither the first nor the second to discover it, but I put some polish (“kibosh,” as sculptors said 150 years ago) on it. My thoughts on highfalutin are low-key for an obvious reason. As will be seen, I have only one feeble idea and am offering it in the hope that, despite the lack of a persuasive solution, it may redirect the search for the source of this enigmatic adjective. But before sharing my small treasure with the world, I would like to quote the explanation given in John Hotten’s Slang Dictionary (the spelling and punctuation of the original have been retained): “Highfaluten, showy, affected, tinselled, affecting certain pompous or fashionable airs, stuck-up—‘Come, none of your highfaluten games:’ American Slang, now common in Liverpool and the East End of London, from the Dutch Verlooten. Used recently by The Times in the sense of fustian, highsounding unmeaning eloquence, bombast.” (Note how often the names of cloths end up meaning ‘pompous speech’: here fustian and bombast, both reflecting the idea of padding.) Hotten’s dictionary appeared in 1859, but I was quoting from the third edition (1864).

We notice three things in Hotten’s entry: the spelling (highfaluten), the use of the word in Liverpool and London, and the proposed etymology. The etymology is fanciful. Dutch verlooten (now spelled verloten) is a verb (the infinitive) meaning “to dispose of a thing by lottery, raffle.” There is also Dutch loot “shoot; offspring.” No connection can be established between either of them and highfalutin. The ghost of a Dutch etymon was raised once again in 1902, when a contributor to Notes and Queries traced -faluting to verluchting “an airing” (luchtig “airy, thin, light; unsubstantial, etc.”)—thus, “flighty talk,” another dead-end proposal. Unfortunately, Hotten’s derivation has been repeated in several popular books in which verloten was upgraded to an adjective meaning “high-flown, stilted.” But two other features of Hotten’s comment have hardly been discussed at all. I cannot imagine that by the middle of the 19th century an Americanism mainly used at home in reference to the inanity and shallowness of official orations (this is the impression the earliest quotations make) reached Liverpool and even the East End of London. The parents of those whom Jack London met and described in his 1902 book The People of the Abyss (it is about the slums of the East End) would hardly have known and appropriated this piece of American political slang. I also doubt that The Times would have used it then; in the middle and even at the end of the 19th century it was customary in England to pity the coarseness of “our American cousins” and resent Americanisms. So I risk suggesting that the word is British, even though the first recorded examples are from the United States. Finally, we see that Hotten did not hyphenate the word and spelled it highfaluten, not highfalutin, let alone high-faluting or high-falutin’. He probably did not think that the second element of the compound was a participle.

The other conjectures on the derivation of highfalutin

Blog: What's New (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: games, activities, vocabulary, spelling, computer games, Add a tag

I just discovered some very cool word games at Merriam-Webster's Word Central. The games are specifically designed for kids with fun sounds and cool graphics.

In Alpha-Bot, a robot challenges you to a spelling contest.

In Robo-Bee, a bee sends you flying after just the right word--synonyms, antonyms, and more.

Bigbot involves hand-eye coordination as well as a good command of vocabulary, as you try to feed the ravenous robot.

And finally, my favorite game--JUMBLE KIDS. I tried to do my own version on July 27.

You'll love the Merriam-Webster version. You earn puzzle points and play against the clock.

Don't wait to explore the possibilities...

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: A-Featured, Oxford Etymologist, Lexicography, word origins, spelling, etymology, anatoly liberman, history of english, Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Tier, tear (noun), tear (verb), tare, wear, weary, and other weird words

Even the staunchest opponents of spelling reform should feel dismayed at seeing the list in the title of this essay. How is it possible to sustain such chaos, now that sustainable has become the chief buzzword in our vocabulary? Never mind foreigners—they chose to study English and should pay for their decision, but what have native speakers done to deserve this torture? The answer is clear: they are too loyal to a fickle tradition.

Nowadays not only the “public” but also prospective linguists have insufficient exposure to the history of language, while English majors, who are taught to view every text through multiple “lenses” (another great academic buzzword), may graduate without any knowledge of the development of English, for no optical tools have been invented for examining this subject. Even the few graduate students who choose the past stages of language as their main area of expertise and risk staying independent scholars (this means “unemployed”) for the rest of their lives will usually study Old and Middle English but come away with the haziest idea of what happened between the 16th and the 19th century, though it was during the early modern period that the system of English vowels was hit the hardest. This holds not only for the so-called Great Vowel Shift that gave long a, e, i, o and u their present values and drove a wedge between the pronunciation of letter names in English and the rest of Europe. All vowels before r were also caught in this storm

To begin with, er turned into ar. We are dimly aware of this process because we still have Clark, parson, and varsity alongside clerk, person, and university. Providentially, some words like star and far are now spelled with ar, but in the past they too had er. Later, er reemerged in English and stayed unchanged for some time. Our vowels are still called short and long, but these terms are misleading, because the sounds designated by a, e, i, o, and u in mat, pet, bit, not, and us are not simply shorter than those in mate, Pete, bite, note, and use: they are quite different. One gets an idea of short versus long (as in Latin, Italian, Finnish, Swedish, and many other languages), while comparing Engl. wood and wooed. Several pairs of such vowels existed in early English. One more factor played an outstanding role in the history of words like tier and tear. There were two long e’s: closed (approximately as in pet) and mid-open (approximately like e in where), but having greater duration than in those modern words.

Although neither of the two e’s has continued into present day English unchanged, we can guess which stood where while comparing the spelling of meet and meat. To the extent that our erratic spelling reflects an older norm, ee points to closed long e and ea to its more open partner. But in the absence of a recognized standard, many words were not spelled in accordance with their pronunciation. Besides, as far as we can judge, a great deal of vacillation characterized the use of mid-open and closed long e. Apparently, the two vowels we

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Reference, A-Featured, Oxford Etymologist, Lexicography, Dictionaries, word origins, spelling, tattoo, kibosh, anatoly liberman, arctic, hoosier, cabaret, tatoo, yeo, Add a tag

by Anatoly Liberman

HOOSIER.

Almost exactly two years ago, on July 30, 2008, I posted an essay on the origin of the nickname Hoosier. In it I expressed my cautious support of R. Hooser, who derived the “moniker” for an inhabitant of Indiana from a family name. I was cautious not because I found fault with his reasoning but because it is dangerous for an outsider to express his opinion on a special subject; American onomastics (a branch of linguistics devoted to the study of names) is not my area. The bibliographers who had done outstanding work in listing the documents pertaining to Hoosier seem to have missed the article in Eurasian Studies Yearbook, 1999, 224-231. However, none of them reacted to my defense of the Hauser/Hoosier hypothesis either. Perhaps they missed that post: it is impossible to follow everything that appears in the Internet. Only Mr. J. Vanhoosier wrote a few words about the history of his family. His comment dates to February 2009. Mr. Randall Hooser (in Yearbook, his full name was not given) noticed my post in June 2010 and responded in some detail. Comments that are added so late have no chance of attracting my attention, because this weekly blog has existed for more than four years, but Mr. Hooser contacted me and sent me numerous supporting materials. His interpretation of historical evidence does not seem to be controversial, and I will deal only with the etymology of the nickname.

Mr. Hooser is not a linguist, and this is why he made too much of the fact that the High German au corresponds to long u (transliterated as Engl. oo) in Alsace, the homeland of the Hausers/Hoos(i)ers. But this correspondence needs no proof. In Middle High German, long i and u (transliterated by Engl. ee and oo) underwent diphthongization, which spread from Austrian Bavarian dialects in the 12th century and later became one of the most important features of the Standard. The “margins” of the German speaking world were unaffected by the change, so that the north (Low German) and the south (Alsace and Switzerland) still have monophthongs where they had them in the past. What has not been accounted for is the variant Hoosier as opposed to Hooser. In my 2008 post, I referred to such enigmatic American pronunciations as Frasier for Fraser and groshery for grocery, but analogs have no explanatory value. However, according to Mr. Hooser, linguists from Kentucky informed him that in the Appalachian area this type of phonetic change is regular, so that Moser becomes Mosier, and so forth. The cause of the change remains undiscovered. Although in this context the cause is irrelevant, I may note that in many areas of the Germanic speaking world one hears sh-like s, notably in Icelandic and Dutch, but not only there. Sh for s and zh (the latter as in Engl. pleasure, as you, and genre) for z characterized the earliest pronunciation of German. The Proto-Indo-European s was, in all likelihood, also a lisping sound. Perhaps the area from which the Hoosers migrated to America has just such a sibilant.

The original derogatory meaning of Hoosier is certain. Yet the word’s adoption by Indiana should cause no surprise; compare Suckers and Pukes for the inhabitants

Blog: Teachers Are Sparklighters for Literacy Everyday! (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing, ideas, families, spelling, kindergarten, Letter Learning, Ellen Richard, Add a tag

Via the Internet, I recently met an amazing teacher and innovative entrepreneur and she has some terrific ideas so I asked her to post a guest blog. Here she is with her husband and their new baby (Ellen took a bit of time off from teaching when their baby was born and she put her educator energies to good use). I've also posted similar comments on this subject at my blog for parents so feel free to share it with moms and dads, grandmas, uncles and other family members who interact with young children. So without further adieu, here's Ellen:

I think we'd all agree as teachers that spelling is tough. But, as a teacher from down in the trenches, I can tell anyone that demanding that kids write the same words over and over and over again is not the most productive use of your or the children's time. Smart teachers have shifted away from rote memorization and endless tracing of inconsequential spelling lists and, instead, are spending their time figuring out ways to engage students. It's my experience that kids who truly are excited about any subject matter learn more and learn it faster. So how do we get them excited about spelling?

A Sidebar of Sorts

Before we talk about that, I want to digress for a moment and talk about students who have issues memorizing (there are many out there, not even counting those with identified learning disabilities). You know at least one student like this I'm sure and they are in a real pickle. There is no context for the words and there are no connections made. Now, in all fairness, sometimes the spelling words provided by the textbook you use rhyme, but more often than not, they are just a group of words that a publisher of curriculum happens to think were appropriate for students at that grade level. One size doesn't fit all. There are so many kids whose brains just work a little differently and, for those kids, spelling can be a huge problem.

Now back to the question:

How do we get them excited about spelling?

It starts with authentic learning experiences.

Kids need engagement in what they are doing. They need to see how and why spelling is so important. When we write something important, something we want to communicate, proper spelling is the common ground that helps our readers understand what we want them to know or feel or "get". Tracing a list of words does not help students make essential connections that they need to make to learn how to spell words, or retain that information. It doesn't help them be able to communicate clearly.

TRACING AS A TOOL

I believe it's just fine to have young kids trace words to help them learn how to spell but here's the catch -- the words have to be meaningful. A list of random words is not meaningful. A letter to a friend, on the other hand, often is. A story written by the child himself is meaningful. An article about the child's favorite sport or musician is meaningful. It's our job as educators to find out what interests our students so we can help them make those connections.

You can certainly use the tracing idea and even get a few volunteers from among your parents to help you create the "traceable" letters with a

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: etymology, anatoly liberman, Bosom, hrether, Reference, language, Breast, A-Featured, Oxford Etymologist, Lexicography, Dictionaries, spelling, Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

In today’s English, the letters u and o have the same value in mutter and mother, and we have long since resigned ourselves to the fact that lover, clover, and mover are spelled alike but do not rhyme. (Therefore, every less familiar word, like plover, is a problem even to native speakers.) Those who want to know more about the causes of this madness will find an answer in any introduction to the history of English. I will state only a few essentials. For example, the vowel of mother was once long, as in school, but, unlike what happened in school, it became short and later acquired its modern pronunciation, as happened, for example, in but. We still spell mother as in the remotest past. Medieval scribes had trouble with combinations uv/vu and um/mu (too many vertical strokes, “branches”) and preferred ov and om. That is why we write love and come instead of luv and cum (or kum). If I may give one more blow to a dead horse, these are the words that spelling reform should leave untouched: love and come are so frequent that tampering with them will produce chaos, even though luv appears in all kinds of parody.

Bosom, with its first o before s, looks odd even against this checkered background, though from a phonetic point of view it is not more exotic than mother. (The difference is that we become familiar with the written image of mother early in our education; also, other and smother produce a semblance of order, whereas bosom is unique in its appearance and is close to a poeticism.) Both mother and bosom had long o, as in Modern Engl. awe and ought in the speech of those who distinguish between Shaw and Shah (isn’t it a pleasure to have the privilege of choosing among aw, au, augh, and ough—compare taw, taut, taught, and ought—for rendering the same sound? In British English they also have or and our, as in short and court, on their menu). Consequently, if bosom were today pronounced like buzz’em, we might perhaps feel less baffled. And at one time it was pronounced so.

The first vowel in bosom alternated with its long partner as in booze and with u as in buzz until at least the end of the 18th century. The Standard Dictionary (Funk and Wagnalls), published in the United States in 1913, recommended the vowel of booze in bosom. Nor is this word an exception. Today it is hard to believe that the pronunciation of soot used to vacillate in the same way and could rhyme not only with loot but also with shut. Professionals, who dealt with soot on a daily basis, preferred the vowel of shut, but the tastes of their cleaner superiors prevailed. In British dialects, book, cook, look, and took often have the vowel of Luke. In what is called Standard English, bosom is now pronounced with a short vowel, and, all the historical elucidations notwithstanding, its spelling produces the impression of a typo. I have not yet met a beginner who would not mispronounce this word, though foreigners studying English are enjoined never to trust what they see, even when the word has the most innocent appearance imaginable (for example, one, gone, done, lone, pint, lead, read, steak, Reagan, and pothole, the latter somewhat reminiscent of Othello).

The etymology of bosom, from bosm, an old word with a long vowel, as noted, has not been found, even though the other West Old Germanic languages (this type of grouping excludes

Blog: Amsco Extra! (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: English Language Arts, Spelling, Add a tag

The annual National Spelling Bee has received serious media attention over the past decade, even inspiring two Hollywood films: Akeelah and the Bee and Spellbound. Just yesterday, in the weekly e-mail Amsco receives from the National Council of Teachers of English, I was reading about a book written by James aguire on the national spelling bee. The book is titled The American Bee: The National Spelling Bee and the Culture of Word Nerds.

The annual National Spelling Bee has received serious media attention over the past decade, even inspiring two Hollywood films: Akeelah and the Bee and Spellbound. Just yesterday, in the weekly e-mail Amsco receives from the National Council of Teachers of English, I was reading about a book written by James aguire on the national spelling bee. The book is titled The American Bee: The National Spelling Bee and the Culture of Word Nerds.  Once students arrive in D.C., students take a 25-word written test, which eliminates about two-thirds of them from the contest. The written test is combined with a session in which each student has to spell at least one word on stage. The Scripps-Howard Foundation does this so that each student can feel as if he or she participated in the celebrity of the National Spelling Bee, even if he or she is eliminated in the first round.

Once students arrive in D.C., students take a 25-word written test, which eliminates about two-thirds of them from the contest. The written test is combined with a session in which each student has to spell at least one word on stage. The Scripps-Howard Foundation does this so that each student can feel as if he or she participated in the celebrity of the National Spelling Bee, even if he or she is eliminated in the first round.Blog: HOMESPUN LIGHT (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: crafts, valentine's day, homeschool, spelling, gifts, writing, crafts for kids, importance of family, Add a tag

I know there are lots of mushy books out there you could use. This book, You and Me by Martine Kindermans, works well because the simple color scheme is used throughout the book.

It was a fun project. Bubs and Welly didn't even realize they were practicing their writing and spelling. ;)

Blog: First Book (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: hollywood, spelling, Books & Reading, Love You Forever, text message, Literacy Links and Articles, Poets House, WNYC, achievement gap, Early Learning Challenge Fund, Rober Munsch, Add a tag

Early Start for Reading

Read and listen to WNYC’s report on a new literacy curriculum being piloted in New York City shows signs of promise in closing the gap in reading scores between low-income and middle class students.

Read All About It: National Book Festival

For those in the D.C. area, check this out from Express Night Out: “Bibiophiles should head down to the National Mall on Saturday for the ninth annual National Book Festival, which is bringing dozens of notable authors to D.C.”

Classic children’s books we’d like to see receive the Hollywood treatment

Entertainment Weekly’s Shelf Life blog features four children’s books they’d like to see get made into a movie, complete with casting suggestions and sample dialogue.

Initiative Focuses on Early Learning Programs

A legislative effort already passed by the House proposes funding to establish the Early Learning Challenge Fund, channeling $8 billion to states with plans to improve standards, training and oversight of programs serving infants, toddlers and preschoolers.

Text message speak ‘not harmful to children’s spelling’, says research

The Telegraph reports on new research that suggests using text message language (like OMG, lol and 2mro) does not harm children’s spelling abilities and may even be a good sign.

A long overdue ode to Robert Munsch

Last weekend, Canadian author Robert Munsch, best known for his book Love You Forever, was inducted into Canada’s 2009 Walk of Fame.

Transparent New Home for Poetry

Today, Poets House, a national poetry library and literary center, opens its spacious new home in Battery Park City, New York.

View Next 13 Posts

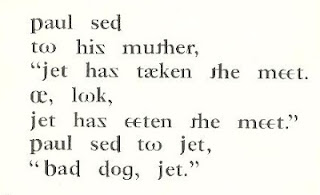

It's all a bit vague, as I learned ita fast, and then learned conventional reading within about two weeks of that. As to whether it wrecked my spelling, for years we thought that was the case, but it turned out what it actually did was mask the dyslexia (diagnosed at 20) as I seem to have learned "look say" naturally, happily switching between ita, English and Hebrew (which is phonetic) without ever quite grasping the notion of phonemes.

It's all a bit vague, as I learned ita fast, and then learned conventional reading within about two weeks of that. As to whether it wrecked my spelling, for years we thought that was the case, but it turned out what it actually did was mask the dyslexia (diagnosed at 20) as I seem to have learned "look say" naturally, happily switching between ita, English and Hebrew (which is phonetic) without ever quite grasping the notion of phonemes.

My abiding memory of ITA was how boring and tedious the reading books were - no mysterious words, humour or poetry just Jet and his sodding car. it was a relief to stop.

I had to use ITA on my first teaching practice with six-year-olds in 1971. It was easy to learn, the children could all read, and the headmaster said they would transfer with no trouble. However,the big disadavantage, it seemed to me, was that until they were about seven they couldn't go home or to the library and pick up and read anything they fancied.

I never did become a teacher, but I do hold a Bronze Medal in Pitman's Shorthand! I think shorthand has been of more lasting use than ITA.

It always seemed a bit odd to me: surely it teaches you how to read one way, then you in effect have to learn all over again. Not that I know as I'm not a teacher and so have no professional or first hand experience of it. When I look at phonetic passages, I struggle to read the text!

Yet I do enjoy reading the odd and entirely variable spellings of early writing, and which don't trip me up at all, straunge and wunderful to relate ...

No comments on ITA, but I don't agree with you, Cathy, about spelling, and in fact I've written a whole ABBA post on the subject! http://awfullybigblogadventure.blogspot.co.uk/2011/03/down-with-spelling.html

You say children have generally muddled through despite our best efforts and there's where I disagree. Lots of children don't muddle through. Even where they do, they have spent hours and hours of their primary school lives mugging up on spellings and being tested on it. Whereas in a phonetic system, like Italian, they can move on to actually reading books they enjoy!

Lovely image of the fossil being cracked open - but I reckon fossils are for scholars - language is for communication and should be as clear as transparent as possible!

Luckily, missed out on teaching ITA.

Yes, it sounded "logical" but I am not sure how many children it truly helped or how many its coded system muddled or held back, especially with its need for special reading books too.

Literacy is about more more than the phonic code, but even real books can be overused in the need for definite educational outcomes. For example, a small 8 year old holidaying person has been totally engrossed in reading & re-reading The Jolly Pocket Postman to herself over three days.

We chatted. She said (with a shrug and a look of sadness and boredom) that yes, she knew the Jolly Postman because a Year 1?/Year 2? teacher had showed it to them in class so that they could learn about letters.

What children need is a full experience of language - and that includes playful activities like the word games/songs that young person and younger brother were making up in the car on the way to swimming, not just an easy-to-mark phonic code.

I get worried that emphasis on one set of skills is absorbing the time that should be used for enrichment too.

Also, wasn't ITA a fashion/feature of an age with fewer visual distractions than children have at their fingertips now? Aren't there so many other ways to meet the need for story and information that reading answers?

Emma, I think we clashed swords (or sords) in the comments on that post, too!

I suspect we're divided by ideological differences on this one, but even at a practical level, spelling reforms are very difficult to implement. Not only would phonetic spelling necessarily stamp one particular way of speaking English as "correct" (and who gets to choose which one?), it would render the entirety of existing literature more or less incomprehensible. Lack of a native literature has always been the stumbling block for new languages such as Esperanto (I speak as the grandchild of an Esperanto translator), and many of the same problems would apply to reformed spelling, at least of a thoroughgoing variety (and what's the point of a half-hearted reform? That after all is something we already have in the form of American spelling, thanks to Noah Webster).

Have you ever come across John Wilkins' Essay towards a Philosophical Language and Real Character? It's charming, but a cautionary tale...

blogwalking mr.

One trouble with phonetic spelling is that both US and British English are spoken so differently in different parts of the country. That this can sometimes cause a lot of problems, I realised when trying to teaching reading (in the US) to a lady in her fifties whose pronunciation of 'hat' sounded like 'HAY-at'.

I take your point, Cathy. But it's sad, watching those children who are really struggling to get to grips with an incredibly illogical system.

It's not about spelling per se, but I thought this article by Vivian French article was very inspiring and insightful about the difficulties that so many children - however imaginative and articulate - have getting to grips with the written word.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/aug/15/vivian-french-dyslexia