new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: phonics, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 10 of 10

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: phonics in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

If you're looking for a game that students will beg to play every week, this is it. I've used it in classrooms and academic enrichment programs at summer camp with fantastic results. Add this to

Bug and

The Mysterious Box of Mystery, and you have three solid sure-fire games for your ELA toolbox.

Big Words is an activity which promotes an increase in phonetic awareness, spelling accuracy, and vocabulary development. The game I describe below was inspired by authors Patricia M. Cunningham and Dorothy P. Hall in their book

Making Big Words. The copy I purchased over ten years ago encouraged me to turn their ideas into a class-wide game which has been a huge hit ever since.

The first objective of the game is to create as many words as possible from a given set of letters. To play, each student is given an envelope containing a strip of letters in alphabetical order, vowels listed first and then consonants. The student cuts these apart so that the individual letters can be easily manipulated on the desktop. Moving the letters about, students attempt to form as many words as possible. Beginners may only be able to form two-, three-, and four-letter words, but with time and practice will be able to use knowledge of word parts and blends to form much longer words.

The second objective is to spell a single word (the Big Word!) with all the letters. In my class, that Big Word very often relates to an upcoming trip, project, or special event, and thus serves double-duty to build excitement and enthusiasm.

As Big Words is used on a regular basis, the teacher can discuss strategies for increasing word counts. Some of these strategies include rhyming, changing single letters at the beginning or ending of each word, using blends, homophones, etc. Many additional words can also be generated through the use of

-s to create plurals, and

-e to create long vowel sounds. Some students will discover that reading their words backwards prompts additional ideas. Additionally, the teacher can discuss word parts which can help students to understand what they read (such as how the suffix

-tion usually changes a verb to a noun, as in the word

relaxation).

While the book emphasizes individual practice, we prefer to play Big Words as a class game. I've outlined our procedures below.

You can also access these directions as a printable Google Doc.BIG WORDS Game Play

- Have students cut apart the letters, and then begin forming as many words as possible using those letters. Remind them to not share ideas with partners, and to not call out words as they work (especially the Big Word).

- After about fifteen minutes, have students draw a line under their last word, and then number their list. They cannot add to or change their lists, but new words that they hear from classmates should be added once the game starts.

- Divide the class into two teams. Direct students to use their pencil to “star” their four best words which they would like to share. These should be words which the other team might not have discovered.

- Determine how the score will be kept (on a chalkboard, interactive whiteboard, etc.). The teacher should also have a way to publicly write words as they're shared so that students can copy them more easily. Here are links to a PowerPoint scoreboard or an online scoreboard.

- Hand a stuffed animal or other object to the first student from each team. This tangible item will help the students, and you, to know whose turn it is to share. Tell students that only the player holding the stuffed animal may speak. Other players who talk out of turn will cost their team one penalty point. These penalty points should be awarded to the opposing team, not subtracted from a score. This will greatly reduce unnecessary noise.

- Play takes place as follows: The first student shares a word, nice and loud. He or she spells it out. If any player on the opposing team has that word, they raise their hand quietly and the teacher checks to see that it is the same word. (It doesn't matter if any student on the speaker's team has the word or not). Every player who has it should check it off, and every player who does not have it should write it into their notebook.

- If no player on the opposing team has the word, then the team scores 3 points. If anyone on the opposing team has the word, then only 1 point is scored.

- If a player shares a word which has already been given aloud, their team is penalized 2 points! This helps everyone to pay better attention to the game.

- Ironically, the Big Word counts for as many points as any other word. Feel free to change that if you prefer, but I discovered that if I make it worth more points, students waste an extraordinary amount of time trying to form the Big Word alone, while ignoring the creation of any smaller words.

- Play until a predetermined time, and then if the Big Word hasn't been formed yet, provide students with the first two or three letters to see who can create it.

Enjoy the game! I know your students will.

Games are the most elevated form of investigation. ~ Albert Einstein

I just finished reading Cathy N. Davidson's wonderful

Now You See It: How the Brain Science of Attention Will Transform the Way We Live, Work and Learn. I'll need to reread it, to be honest, because too often my mind began drifting to my own classroom as I read. I began asking myself if I was doing all that I could to engage students, and the answer was a sad and resounding no. My classes are severely lacking in game play.

According to Davidson, "Games have long been used to train concentration, to improve strategy, to learn human nature, and to understand how to think interactively and situationally." In the classroom, games capture and focus attention, increase motivation, and allow for complete, overt engagement.

My most often downloaded resource, in fact, is a Theme Game I created on Google Slides. At least one of my readers a day downloads this activity, which means that other teachers are seeing the value of game play in the classroom.

I readily admitted to my students that I created Bug, and it would have some, well, "bugs" that needed to be worked out. But students were eager to help in this regard, and our finished game is best described through the Google Slides presentation below.

What We Learned Together1) We decided that certain modifications were allowed (

simple switch,

blend mend,

one letter better) since they were sophisticated and advanced the game, while others were not allowed (adding a simple s to create a plural, adding both a vowel and a consonant together, reconstructing a word that has already been spelled). Students likewise dismissed the possibility of allowing prefixes and suffixes, deciding that those modifications didn't truly change the words enough.

2) We learned that four to five minutes was a suitable time for each round of play. Once each round finished, players could challenge their current partner if the match ended in a tie, or winners could challenge other winners and losers could challenge other losers, or, simply, anyone else could challenge any other classmate. Students didn't care whom they played; students simply wanted to play! My period one class of only eight students played using a traditional bracket to decide a final winner, but other classes were content to engage in free range play.

3) Students did begin to employ strategies. One clever student used "shrug" as her first word each time, instantly earning a power up and leaving her partner with a difficult word to manage. When her second partner countered with "shrub," this student needed to quickly adapt and used her earned power down to create "scrum." Scrum? Yes, this game encourages vocabulary development as well.

4) By game's end we concluded that, catchy name aside, every new game couldn't begin with "bug." Too many students were trying to play the same words each round, and too many rounds fell into the same predictable list of words. We decided that each new game should start with a different three letter word.

5) We played our games with large (12 x 18) paper and colored markers, but for a future game we're likely to play with standard sized paper and colored pencils. Students liked the visual separation that two colors provided, but the size format probably won't be needed in the future.

We would love to hear your recommendations, variations, and success stories!

Games are the most elevated form of investigation. ~ Albert Einstein

I just finished reading Cathy N. Davidson's wonderful

Now You See It: How the Brain Science of Attention Will Transform the Way We Live, Work and Learn. I'll need to reread it, to be honest, because too often my mind began drifting to my own classroom as I read. I began asking myself if I was doing all that I could to engage students, and the answer was a sad and resounding no. My classes are severely lacking in game play.

According to Davidson, "Games have long been used to train concentration, to improve strategy, to learn human nature, and to understand how to think interactively and situationally." In the classroom, games capture and focus attention, increase motivation, and allow for complete, overt engagement.

My most often downloaded resource, in fact, is a Theme Game I created on Google Slides. At least one of my readers a day downloads this activity, which means that other teachers are seeing the value of game play in the classroom.

I readily admitted to my students that I created Bug, and it would have some, well, "bugs" that needed to be worked out. But students were eager to help in this regard, and our finished game is best described through the Google Slides presentation below.

What We Learned Together1) We decided that certain modifications were allowed (

simple switch,

blend mend,

one letter better) since they were sophisticated and advanced the game, while others were not allowed (adding a simple s to create a plural, adding both a vowel and a consonant together, reconstructing a word that has already been spelled). Students likewise dismissed the possibility of allowing prefixes and suffixes, deciding that those modifications didn't truly change the words enough.

2) We learned that four to five minutes was a suitable time for each round of play. Once each round finished, players could challenge their current partner if the match ended in a tie, or winners could challenge other winners and losers could challenge other losers, or, simply, anyone else could challenge any other classmate. Students didn't care whom they played; students simply wanted to play! My period one class of only eight students played using a traditional bracket to decide a final winner, but other classes were content to engage in free range play.

3) Students did begin to employ strategies. One clever student used "shrug" as her first word each time, instantly earning a power up and leaving her partner with a difficult word to manage. When her second partner countered with "shrub," this student needed to quickly adapt and used her earned power down to create "scrum." Scrum? Yes, this game encourages vocabulary development as well.

4) By game's end we concluded that, catchy name aside, every new game couldn't begin with "bug." Too many students were trying to play the same words each round, and too many rounds fell into the same predictable list of words. We decided that each new game should start with a different three letter word.

5) We played our games with large (12 x 18) paper and colored markers, but for a future game we're likely to play with standard sized paper and colored pencils. Students liked the visual separation that two colors provided, but the size format probably won't be needed in the future.

We would love to hear your recommendations, variations, and success stories!

By: Nicola,

on 1/3/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Social Sciences,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

and the ugly,

Science & Medicine,

mike anderson,

Neuroscience in education,

sergio della sala,

the bad,

the good,

number nclc,

05276,

teaching,

Education,

Psychology,

neuroscience,

phonics,

neuro,

Add a tag

By Sergio Della Sala & Mike Anderson

In the past ten years, there has been growing interest in applying our knowledge of the human brain to the field of education, including reading, learning, language, and mathematics. Teachers themselves have embraced the neuro revolution enthusiastically. A recent investigation in the US-based journal Mind, Brain, and Education showed that almost 90% of teachers consider knowledge about brain functioning relevant for the planning of education programmes.

This has resulted in the development of a number of new practices in education: some good, some bad, and some just crazy. Too often, people with the clout to make decisions about which practice is potentially profitable in the classroom setting, ignore evidence in favour of gut feelings, the authority of ‘gurus’, or unwarranted convictions. In short, opinions rather than data too often inform implementations in schools. Hence we have had theories suggesting that listening to Mozart can boost intelligence, foot massages can help unruly pupils, fish oil can boost brain power, and even the idea that breathing through your left nostril can enhance creativity! Sadly, it is often scientists themselves who promulgate unsubstantiated procedures.

We shouldn’t ignore the good practices and innovations in education thanks to the developing neuro revolution. A popular example might be the neuroscience data suggesting a strong neural link between fingers and numbers. This is testified by the observation that 6 year old children who are good in recognizing their fingers when touched will later also be better at arithmetical performances. However, more often than not “the good” classroom developments are actually centered around more mainstream cognitive findings. One such finding, named spaced practice, has been replicated many times; it shows that distributing learning over time is more efficient than massing it all together. For example, if students stockpile learning just before an exam, they may do well enough, but if they want to retain the material in the long term, then retrieving it via multiple tests is much better.

Inevitably, we are drawn to discussing “the bad” developments: one of our favourite examples is the use of ineffective coloured lenses to aid reading. This and several other unproven “aids” are potentially damaging the whole idea that knowledge of the mind-brain may contribute to efficacious educational practice. And of course much of current enthusiasm for neuroeducation involves ugly mistranslations of excellent research into an educational arena. Take for instance the misapplication of the well developed theory of reading (the so called dual-route theory) which has been caricatured and wrongly applied in education to justify an ideological stance from teachers preferring a whole-reading (or holistic) approach at the expense of phonics-based teaching. Briefly, the dual-route theory says that single-word reading can be accomplished through a route of letter to sound conversion (phonics) or through a route of direct visual recognition (whole word reading). It does not say that both are equally effective in teaching children to read. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated that phonics is a more effective method; yet the holistic approach to learning to read rages in the classrooms.

The neuro- prefix is very fashionable nowadays, and neuroeducation is just one of the myriad offsprings. Neuroscience offers an invaluable contribution to assess, diagnose, and perhaps manage pathologies, including pathologies of learning in children and adolescents. However, neuroscience as such has so far proved to have little to offer to everyday, normal education. The discipline which has most to offer is instead cognitive psychology, and from this comes some of the “good” that scientists could endow education with. Some of the findings from cognition are solid and counter-intuitive; for example, retrieval practice that, though receiving little support by pedagogists, has proved effective in improving pupils’ learning. This practice is based on the finding that retrieving material through several testing enhances learning of that material more than studying it over and over again.

The psychology of learning could prove efficacious in an educational context. However, science should never be prescriptive; it offers possible windows of knowledge which may or may not be applicable or relevant in specific contexts such as the classroom. There are no ready-made recipes when it comes to mastering the relevance of brain functioning to teaching today. The last thing teachers need is to be superficially trained in neuroscience, but they should certainly watch this space.

Sergio Della Sala is a Clinical Neurologist, Professor of Human Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Edinburgh, UK. He is co-editor with Mike Anderson of Neuroscience in Education: the good, the bad, and the ugly, and editor of Cortex. His research focuses on the cognitive deficits associated with brain damage.

Mike Anderson is a Professor of Psychology and Director of the Neurocognitive Development Unit at the University of Western Australia. His research focuses on the influence of the developing brain on intellectual functions in children.

Image credit: Photograph of boy studying by Lewis Wickes Hine, ca. 1924, via Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Child Labor Committee Collection, [image number nclc.05276].

The post Neuroscience in education appeared first on OUPblog.

I have no teaching qualifications. I'm not an educational expert. But simply through being a children’s writer (and in addition, a parent) I’ve been drawn into taking an interest in the latest raft of proposals about our children’s education.

It started with a phone call from my local radio station, BBC Radio Leeds. What did I think about children learning poetry by heart, they asked. Huh? Was my highly articulate reply. The truth was I didn’t have a worked out opinion, but learning poetry by heart is one of the proposals in the new Gove paper on primary education, and so (the radio station reckoned, not unreasonably) as a children’s writer, and one who regularly goes into schools, I really ought to have a view.

So, I read the proposals. I went on air. And I’ve been stunned by the conviction – almost vitriol – that seems to characterise the debate. Learning poetry was an essential art, inducting children into the rhythm of the language, giving them discipline and the lasting gift of verse that their grandparents enjoyed, one side thundered. Drilling kids in poetry was a regressive step, designed to humiliate them, and destroy their love of learning, thundered the other. The trouble is, as with most educational debates, it never seems to me as cut and dried as the opposing camps suggest. It could be a good idea. But a lot depends on the way it’s done.

Around the same time, the Children’s Laureate, Michael Rosen, was circulating a petition for children’s writers to sign, condemning the provisions on phonics in the same government document. (Read the petition here.) Once more, I felt uncomfortable. Rosen is one of the most articulate critics of Gove’s approach to education in general.

But...my own impression is that phonics can be helpful. I doubt that - as Rosen sometimes seems to imply – exposure to storytelling and being surrounded by books is enough to get kids reading. Not at first. I’ve watched my own child learn to read. I’ve talked to other parents. And I’ve talked to dyslexia tutors, who often advocate a structured approach.

Above all, as a writer, I’ve visited plenty of primary schools, and met the children who are struggling to read at a level appropriate to their age. That’s desperately sad.

It’s left me feeling that, as a children’s writer, I’m not confident to weigh in on reading methodologies. The important thing is not ideology, but what works. I’d like others to make that decision, based on the very best evidence out there. (Not an easy task I know.)

Where I DO have a strong conviction, and where I strongly agree with Michael Rosen’s petition, is on the importance of reading for pleasure. Once children have mastered the basics of reading – by whatever methodology – they need to enjoy it. Otherwise they won’t read. And they must, if they are to become truly literate, educated people, capable of understanding the world around them – the world that lies beyond their own narrow experience.

As many people, including Michael Rosen and the Society of Authors, have pointed out, it is scandalous that the government, which is so ready to impose targets and objectives generally, is prepared to give no more than lip-service to the idea of “reading for pleasure”. The government acknowledges the vast body of research supporting its importance. Every school should be encouraging it, they say. Yet none of the concrete measures needed to encourage it are in place.

What is needed? It’s simple really.

- Every school should have a library. Schools make space for computers – but books are far cheaper, and what children need if they are going to read is books.

- Every school should have a librarian.Somebody on the staff of every school should have the job of understanding which children’s books are out there, choosing the stock, and guiding the children to the books that might interest them. That also means they need the budget and the training. It shouldn’t depend on luck – that there is somebody on the teaching team that has that special interest – as it does at the moment.

It would make such a huge difference. It really would. So, I say forget about the ideology. The arguments about whether six year olds should be reciting Longfellow, or following whichever brand of phonics.

GET THE BOOKS TO THE CHILDREN

It’s not rocket science. It’s something surely on which we can all agree.

Emma's web-siteEmma's latest book is Wolfie.

An early reader who knows some common two letter phonograms will be able to decode or sound out more words. This will maybe prevent the habit of guessing at too many words. Most children I've tutored with reading had a habit at guessing at words and ignoring most letters. It's hard to unlearn this habit. Guessing at words works with early reader books with lots of picture clues. Readers with

Many phonics books have short vowel words. My last post shared a good phonics book set with short vowel words. There are 10 short vowel phonics stories in the Playful Pals book set. I added an extra way to practice reading short vowel words to that post. You may want to go back and check it out. You can find free online short vowel phonics books at Starfall, Progressive Phonics, and

Tonka Phonics Reading Program: A Comprehensive reading program containing 12 all-new books, 15 flash cards, and a parent letter. Published by Scholastic.

I was a bit of a skeptic on this one, I admit. Perhaps because I'm a bit skeptic about phonics. Don't get me wrong. I came of age (began kindergarten) when phonics reigned supreme. (I know this changes back and forth and back and forth through the years.) We had "phonics" through second grade. (Which seemed a little like overkill to me, to be honest.) I remember going through the drills "st" in "stop" "gl" in "glue" "squ" in "squeak" or whatever it was for squ. And in kindergarten we spent months learning ba, be, bi, bo, bu (etc.) before we ever tackled words--like cat, bat, mat, hat, etc. I remember the 'joy' of reading such great books Matt the Rat, Pig in the Wig. But each phonics program, I believe, is a little different. And phonics doesn't have to mean that you divorce all meaning from the process.

The books are simple stories about trucks being trucks and doing truckish things on the road and on construction sites. My favorites are probably Truck It In! and Trash Dash. For preschoolers who are truck enthusiasts these books may be a lot of fun. They do include plenty of sound effects like beep, crash, splash, etc.

Tractor Tracks = short a

Get Set to Wreck = short e

Mix it up = short i

Stop! Road Block! = short o

Dump Truck Dump! = short u

Raise the Crane = long a

Beep! Beep! = long e

Fire Siren = long i

Slow Tow Home = long o

Go, Trucks, Go! = plurals

Trash Dash = sh

Truck it In! = ck

Sample text from the books:

I am a tractor.

I drag my plow

across the land.

I can plant the seeds.

Let's get set to wreck!

Let's send the

metal ball flying.

I am a big

mixer truck.

I have a big list

of things to do.

I am a dump truck.

I lug and dump stuff.

I hum as I run.

Hum! Hum! Hum!

A rock is stuck

in the muck.

We need a truck!

They bold the text that (supposedly) at least illustrates the new concept. They don't always get it right. Sometimes they bold something that doesn't make the right sound. (Across doesn't have a short a sound. Send doesn't have a short e sound, at least it doesn't to my ears.) Sometimes something makes the right sound, but doesn't get bolded.

Firefighters climb

up my sides.

They hold on tight.

My siren is loud.

My lights shine.

Climb has a long i sound as does my. And I'm not sure why they didn't include shine.

I'm not sure why they didn't include a long u book other than the fact that maybe they couldn't think of anything truck or construction related to go with a long u sound. (I can't think of anything off hand either.) They're not perfect books, but they're fun books.

© Becky Laney of

Young Readers

Do any of you remember how you learnt to read your name? I learnt mine by seeing it written again and again… in print, in cursive and in capitals… on books, on scraps of paper, in the steam on our kitchen window at breakfast in winter. And I recognised my name without resorting to any form of phonics. In fact if I’d tried to sound it, I’d never have managed. Nor would I have managed to read Pinocchio because unless you’re Italian how would you know to say ‘kee’ instead of ‘chee’ as in church.

Do any of you remember how you learnt to read your name? I learnt mine by seeing it written again and again… in print, in cursive and in capitals… on books, on scraps of paper, in the steam on our kitchen window at breakfast in winter. And I recognised my name without resorting to any form of phonics. In fact if I’d tried to sound it, I’d never have managed. Nor would I have managed to read Pinocchio because unless you’re Italian how would you know to say ‘kee’ instead of ‘chee’ as in church.

The point I’m trying to make is that we learn to read in spite of ourselves by recognising shapes of words and reading them as a whole word in the context of a story. The more a child is exposed to words by hearing the words repeated and seeing them in print, the more a child can absorb words. They become part of an embedded, dynamic, rhythmic pattern. Seeing pattern and shape and texture is inherent in all of us. Yet children are being taught the phonics method.

It was brought home to me yesterday during a visit to a reception class where I put up a cover of one of my picture books and listened to a boy trying with excruciating difficulty to sound Dianne Hofmeyr… impossible! There will be many views on this one. Some might argue that phonics give children the tool to break down words. But I think the eye of the child is intelligent enough to see pattern. Once the entire word is spoken and it's shape recognised again and again and again, it’ll be remembered – whether in a book, or on a cereal box, or in the steam on a kitchen window.

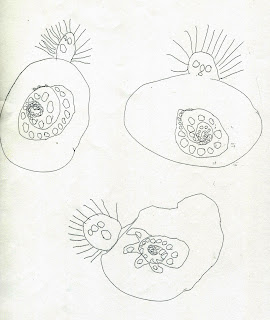

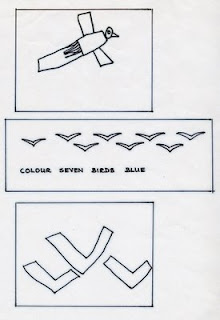

The eye of the child is frighteningly observant. The drawing to the left demonstrates this… a child’s drawing of a bird, flying with enormous energy and imagination and then the same child drawing a bird after having been exposed to a workbook.

Children of four should be playing, drawing, and enjoying books, not learning to spell their name and colouring in their workbooks. ‘Colouring in’ books were banished in our house. All that's needed to give freedom to the power of a child’s imagination, is a surface and something that makes a mark, because a child who is allowed to ‘story’ in his head by drawing, is a child who is opening up to the world of both oral and written stories.

I’m no longer sure what inspired my son at age three to do the drawing, ‘Taking my Snail for a Walk’, but it must have been some intense experience. If only we are able to keep those intense experiences alive for children… an intense experience of story. I can still almost smell the forest and hear the sound, as I recall the picture of Pookie the rabbit and the long line of his friends thumping their back legs to frighten off the wood-cutters.

Don’t let’s limit children and their imagination in any form… let’s banish phonics.

You put it all very clearly, Emma. I can never see why they don't make these decisions based on evidence, rather than conviction - and I'd prefer the evidence to be presented by educational psychologists who are skilled in interpreting it, rather than by politicians who are very good at being impassioned and rousing emotion.

Great post, Emma; and I think your 3rd paragraph cuts to the heart of the matter. Learning poetry is a terrific thing to do. Forcing teachers to drill children in poetry is a terrible and destructive idea.

It all depends on the way it's done.

Likewise with phonics, a hugely important tool in the primary teacher's toolbox. But then there's this.

And as you and Sue both point out - there's strong evidence out there about what works, which gets ignored in favour of ideology. It makes me so cross!!!

(And not only do children need school libraries - they need local libraries, which Mr Gove's colleague Ed Vaizey is doing such a fine job of neglecting)

Great post - and how can anyone possibly quibble with the need for every school to have a library?

As opposed to reading schemes, and learning poetry - what i question is the 'one size fits all' approach. Some children respond to phonics, others need a different approach. For some learning poetry will open magical doors while others will squirm week after week when they simply can't remember them.

We understand the complexity of adults - we are all different, with different needs and learning styles, yet somehow insist that children fit into the one learning box - how does that make sense?

Really good post, Emma. Trouble comes when politicians who don't really know what they're talking about try to impose all-or-nothing structures on education. I believe that children do need a structure to start off with - then reading for pleasure will come. I remember the bad old days in the eighties of 'real books' and the hordes of children who failed to pick up reading skills by osmosis.

Libraries/Librarians - good. No Libraries/Librarians - bad.

Thanks for your interesting comments, everyone.

John and Sue - I suppose one of the problems is that the evidence is always subject to different interpretations. What is depressing, is that interpretation seems often to be part of some larger ideological/political battle.

And as John points out, the decline in public libraries makes the school libraries even more vital for children to get hold of books.

And the thing is, getting books to children seems to me actually quite cheap, as well plainly A GOOD THING - books are so much cheaper than many of the other things that schools have to spend their money on.

Emma: "I suppose one of the problems is that the evidence is always subject to different interpretations. What is depressing, is that interpretation seems often to be part of some larger ideological/political battle."

Couldn't agree more! And misinterpretation of the evidence for ideological reasons is a huge problem.

I should also point out there is mass lobby for school librarians: There will be a Mass Lobby for School libraries in London and in Edinburgh:

On Monday 29 October- Houses of Parliament, in London

On Saturday 27th October at the Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh

Have a look at Linda Strachan's post a few days ago for more on the vital role of school libraries/librarians http://awfullybigblogadventure.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/school-libriaries-and-librarians.html

Great post! Spot on.

I feel sorry for the children who are experimented on every few years, when politicians decide to push out yet another different way of teaching kids to read.

If they change it, does that mean the last way they instructed teachers to teach reading was not working? if so why revert back to something that was taught before that, because if it worked so well, why did they stop using it?

It seems an endless cycle and the only people at risk are the children.

But there is one thing that is indisputable - children need books, lots of different kinds of books. They need interesting and stimulating books that develop a love of reading and stories.

They need libraries with librarians, people with the enthusiasm and skill to help find the right book for each child.

Often a child who has some level of reading skill but does not read much, has just not found the book that has something to say to them, and when they do it can change their life.

I did teacher training a few years ago and you're absolutely right - reading for pleasure has been put on the backburner. Storytime often had to be planned into the day - no spontaneous stories there - and the worst incident was when I overheard my Year 1's comparing Oxford Reading Tree levels with one another. Surely they shouldn't be thinking about that at all, much less proudly stating to their friend 'I'm a level 5 now, which level are you on?'

Watching the education debate for the last few years, I've come to the conclusion that there's no sure-fire, guaranteed to work, one size fits all way to teach children to read. Some swear by phonics, while others swear by word recognition, while others swear by spelling it all out. Why stick to just one method, when you could combine multiple ones together and each child could find a way to read that suited them?

Good on you, Emma. The death of the school library would be a dreadful, dreadful thing. As for phonics, I'm not qualified either but I do see some value in them, too. When used in combo with lots of other methods, etc. And reading for pleasure is THE THING WE MUSTN'T FORGET!!

Well folks, next week is Children's Book Week. No better time for children (and their respective grown-ups) to pick up a book for no reason other than sheer joy of reading!

Hi Emma, this is a really enjoyable post to read. I am a primary teacher and I like to think that I do have a good understanding of how children learn to read and like Michael Rosen says FOREMOST you have to get children to love reading and you do that by reading. Once they love reading, then they want to learn and then you can do all the phonics and sight words and what not to give them the skill.

I no longer live in the UK and thankfully no longer teach the national curriculum (which was one of the factors that led me to bugger off in the first place). Personally I think that the day that the UK stops having Government think tanks dictating education and hand it back to the experts will be the day that the British education system will start improving. For now please keep writing great books so that us 'parents' have some good stuff to share with our kids.

Michele - thanks for your comment. Like I say, I don't feel qualified to comment on many educational debates, but the evidence that "reading for pleasure" is beneficial is so strong, that surely more should be done.

I had a wonderful visit to a school yesterday where the children were so welcoming and so enthusiastic about my books. Despite all the modern distractions, children do love books - they need the time to read and the opportunity to find the books that appeal to them.