Fox, which once considered selling "Simpsons"-branded beer "detrimental to children," has changed its tune.

Add a CommentViewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Chile, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 23 of 23

Blog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Cartoon Culture, Licensing, Fox, The Simpsons, Jeffrey Godsick, Chile, TV, Add a tag

Blog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, US, Japan, UK, Spain, Iran, Animated Fragments, Mehdi Alibeygi, AllaKinda, Estudio Pintamonos, Max Halley, Sarah Airriess, Yukie Nakauchi, Add a tag

Interesting animation is being produced everywhere you look nowadays. This evening, we’re delighted to present animated fragments from six different countries: Chile, Iran, UK, US, Japan and Spain. For more, visit the Animated Fragments archive.

“Lollypop Man—The Escape” (work-in-progress) by Estudio Pintamonos (Chile)

“Bazar” by Mehdi Alibeygi (Iran)

“Time” by Max Halley (UK)

Hand-drawn development animation for Wreck-It Ralph to “explore animation possibilities before [Gene's] model and rig were finalised” by Sarah Airriess (US)

“Rithm loops” for an iPhone/iPad app by AllaKinda (Spain)

“Against” by Yukie Nakauchi (Japan)

Blog: (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, Uncategorized, Canada, Japan, Taiwan, Amazon, Philippines, Mexico, France, Australia, India, Poland, Germany, New Zealand, Pakistan, Puerto Rico, Belgium, Spain, Slovenia, United Kingdom, Finland, South Africa, Brazil, Singapore, Nicaragua, Ireland, Netherlands, Italy, Turkey, Israel, Switzerland, Nigeria, Sweden, Indonesia, Mongolia, Thailand, Argentina, Morocco, Peru, Jamaica, Norway, Egypt, Indiebound, Iceland, Venezuela, Bahamas, Denmark, Greece, United States, Portugal, Czech Republic, Colombia, Romania, Croatia, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, Ukraine, Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Hungary, Bermuda, Ecuador, Bulgaria, Estonia, Tunisia, Trinidad and Tobago, Girls Sports, Bahrain, Lithuania, Namibia, United Arab Emirates, Grant Overstake, Inspirational Sports Stories, Maggie Vaults Over the Moon, young adult sports, KSHSAA, Pole Vault Fiction, Track and Field Stories, sports novels, Recommended sports books for teens, Watermark Books and Cafe, Kansas State High School Activities Association Journal, Austria Botswana, Insirational Sports Books, Isle of Man, Republic of Korea, Russian Federation, Add a tag

Maggie Steele, the storybook heroine who vaults over the moon, has been attracting thousands of visitors from around the world. So many visitors, in fact, that she’s using a time zone map to keep track of them all.* People are … Continue reading ![]()

Blog: Shelf-employed (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, history, book review, nonfiction, survival, J, Non-Fiction Monday, leadership, mining, picture books for older readers, miners, Add a tag

Scott, Elaine. 2012. Buried Alive! How 33 Miners Survived 69 Days Deep Under the Chilean Desert. New York: Clarion.

Though it may seem as if it were only yesterday, it's been nearly two years since the San José mine collapse in Chile's Atacama Desert. The first collapse occurred on August 5, 2010. For two days, an escape route remained open, however, the escape ladder was only 690 feet long. The distance to the surface was 2,300 feet. A subsequent and more devastating collapse occurred two days later on August 7, effectively sealing thirty-three miners underground. It was 9:55pm, October 13, 2010, when the last miner, foreman Luis Urzúa, finally emerged.

Buried Alive! offers a chronological story that is contextual and multi-faceted. Using a theme of cooperation (chapters are titled "Surviving Together," "Working Together," "Planning Together," "Living Together," and "Rejoicing Together"), Elaine Scott begins with an introduction of the various factors that draw men into the mine, including poverty, tradition, and national pride. Other chapters recount the extraordinary way that the miners, under the direction of Urzúa, known affectionately as Don Lucho, organized themselves fairly and purposefully to survive the ordeal, never knowing until they surfaced if they would survive.

Not covered much in televised accounts, was the real meaningful work that the men did to help themselves. They dug sanitary trenches, aided the drillers with useful information, and dug drainage and holding pools for the 18,421 gallons of water that were necessary to cool and lubricate the drill bits as they ground down to the mens' refuge, a 14-day project.

Scott also follows the cooperative scene at Camp Hope, the makeshift town including a school and medical facility, that sprung up to house the thousands of people living in tents above the mine - family members, would-be rescuers, Chilean military members, and more - all awaiting news of "los 33." And journalists were there to provide it,

an estimated 1,700 of them, representing thirty-three countries on five continents. The world had its eye, its ear, and most important, its heart on Camp Hope and the thirty-three men who were buried alive.The cooperative (and, in the case of the drillers, competitive) spirit of the rescuers is chronicled as well. Rescue plans and offers of assistance arrived from around the globe. The logistics of drilling so far down into the ground without mishap is explained in fascinating detail.

Most people will be familiar with the jubilant scenes of rescue, but it does not feel as "old news," rather, Scott's writing rekindles the emotions of the day.

An afterword tells the somewhat saddening stories of what has happened in the miners' lives since the rescue, but the overarching message of Buried Alive! is one of togetherness - for 69 days, the trapped miners, their families and the rest of the world were together in hopefulness.

Buried Alive! How 33 Miners Survived 69 Days Deep Under the Chilean Desert is dedicated "To the thirty-three miners and those who worked, waited, and worried until they were finally free." I count myself among the millions of people who worried about the fate of these amazing men. This is a story that will live on for many, many years to come. Elaine Scott has done a superb job in telling it.

Extensively researched, sourced and indexed with detailed author's notes. Contains numerous photographs.

Blog: Noblemania (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, Batman, Add a tag

Within my first 24 hours in Santiago, I saw more than a couple of signs that Batman is popular here, including these two:

Within my first 24 hours in Santiago, I saw more than a couple of signs that Batman is popular here, including these two:

Blog: PaperTigers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, Picture Books, picture book biography, Julie Paschkis, Bilingual books, Monica Brown, Poetry Books, Cultures and Countries, Week-end Book Reviews, Pablo Neruda: Poet of the People, Add a tag

Monica Brown, illustrated by Julie Paschkis,

Monica Brown, illustrated by Julie Paschkis,

Pablo Neruda: Poet of the People

Henry Holt, 2011.

Ages 4-8

Pablo Neruda: Poet of the People, a picture book biography by Peruvian-American scholar Monica Brown, exudes the spirit of Neruda’s poetry without quoting a single line. The work of award-winning illustrator Julie Paschkis contributes greatly to the success of the book. Beginning with his childhood love of nature and the teacher who inspired him to become a writer, Brown traces Neruda’s rich life, including the awakening of his political consciousness, his escape from Chile over the Andes, and even the houses he treasured over his lifetime. Her language has its own poetry:

“He wrote about scissors and thimbles and chairs and rings.

He wrote about buttons and feathers and shoes and hats.

He wrote about velvet cloth the color of the sea.”

Integrating streams of Spanish and English words into every illustration, Paschkis’s folk-art paintings capture Neruda’s poetic sensibility in visual form. Amidst the masks and clocks and seashells, the fruit and spectacles and pottery, that she depicts to accompany the above text, Paschkis weaves evocative and beautiful words from Neruda’s poems: alcachofa, thistle, clavos, whistle, thrum, timber, azul, apple…

To illustrate Neruda’s participation in a coal miners’ strike, Paschkis pictures people waving word-streaked banners: recoger, defend, nunca, libre, friend, corazón. “When he saw that they were cold and hungry and sick, he decided to share their story,” Brown writes. “Even when his poems made leaders angry, he would not be silenced, because he was a poet of the people.”

An author’s note at the back of the book gives a summary of Neruda’s life, including the names of some of his most famous poems. A resources page follows with a bibliography of Neruda’s poetry books and a reading list of further biographical reading.

This latest in Brown’s biographical series will be welcomed by parents and teachers eager to introduce Neruda’s magical poetry to young readers. (Brown’s earlier books for children include bilingual biographies of Gabriel García Márquez and of Neruda’s seminal teacher, Gabriela Mistral.) The sounds of the words included to illustrate the story of the beloved writer’s life capture the beauty and mystery of poetry for adults and children alike.

Charlotte Richardson

September 2011

Blog: PaperTigers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, Picture Books, Michael Foreman, Week-end Book Reviews, Week-end book review, Mia's Story, Add a tag

Michael Foreman,

Mia’s Story: A Sketchbook of Hopes and Dreams

Candlewick Press, 2006.

Ages 4-8

British author-illustrator Michael Foreman was traveling in Chile when he encountered the family on whom he based Mia’s Story. Mia lives in a “village” between Santiago and the snow-capped Andean mountains she can see in the distance. Her village has a name, but really it is a community of poor people built up on the edge of a vast trash dump, which they scour for anything they can fix and re-sell in the city. Foreman’s appealing illustrations intersperse full-page paintings and conventional text with smaller sketches accompanied by handwritten-looking text, like scrapbook entries.

Mia isn’t the poorest of the poor; she lives in a house, albeit one roofed in tin scraps, and most important, she has both her parents. Her father has a truck, and she goes to school. There is even a horse, Sancho, and eventually a puppy, Poco, who provides the plot structure for Foreman’s story. When he goes missing, Mia, wearing the traditional poncho and ear-muffed cap of Andean people, mounts Sancho and goes off looking for her dog. Gradually they climb higher and higher. “From up there she could look down on the dark cloud that always filled the valley.”

Things look scary for a moment, but when Mia and even Sancho realize that the air is clean and the snow is irresistible, they both have a good roll in it. “The sky had never been so blue and so near.” Mia doesn’t find Poco, but she does discover a field of white flowers and returns home with a clump, “roots and all,” that she plants near her house.

By the next spring, those flowers have spread into a field that provides a new source of livelihood for Mia and her family. Mia tells her city customers that the flowers “come from the stars.” She still remembers Poco, especially when packs of dogs run by the cathedral, where she sells her flowers. Happily, by the end of the story, there is a dog in Mia’s life again.

On the back flyleaf, Foreman explains that Mia’s Story was inspired by people for whom “trash was a crop to be harvested, recycled, and made useful once more.” His book subtly introduces young children to a sophisticated ecological concept through a delightful story.

Charlotte Richardson

September 2011

Blog: La Bloga (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: shamanism, menstruation, Luzclara Camus, sacred feminine, Rio Maipo, Chile, spirituality, menopause, Add a tag

tatiana de la tierra In Chile, Luzclara lives in a round wooden temple that overlooks the Maipo River and faces the Andes mountains. Buddhist flags, statues of goddesses, and an organic garden planted in the shape of a spiral lead the way to Luz del Maipo, the temple that she calls home. This is where she meditates, does yoga, prepares for ceremony, and rides on horseback into the mountains to a special retreat. But shamanic leader Luzclara Camus is a globetrotter who hasn’t been home much lately. She’s been in Poland, Spain, Portugal, and France recently, facilitating ceremonies of the sacred feminine. Her next stop is California, with weekend workshops planned in the Los Angeles area (June 17-19) and in Mount Shasta (June 24-26).

In Chile, Luzclara lives in a round wooden temple that overlooks the Maipo River and faces the Andes mountains. Buddhist flags, statues of goddesses, and an organic garden planted in the shape of a spiral lead the way to Luz del Maipo, the temple that she calls home. This is where she meditates, does yoga, prepares for ceremony, and rides on horseback into the mountains to a special retreat. But shamanic leader Luzclara Camus is a globetrotter who hasn’t been home much lately. She’s been in Poland, Spain, Portugal, and France recently, facilitating ceremonies of the sacred feminine. Her next stop is California, with weekend workshops planned in the Los Angeles area (June 17-19) and in Mount Shasta (June 24-26). A Priestess of the Goddess, Luzclara is on a mission to bring women together in old-fashioned ways. Imagine a circle of women chanting and drumming around a fire under the full moon. “It’s time for women to come together again,” she says. “This is a moment of a great awakening to the feminine, and we are responding en masse. We’ve been living in a patriarchal system for thousands of years, where we had to develop our masculine side in order to survive. We had to learn to compete, for instance, and we had to forget our feminine essence.”

A Priestess of the Goddess, Luzclara is on a mission to bring women together in old-fashioned ways. Imagine a circle of women chanting and drumming around a fire under the full moon. “It’s time for women to come together again,” she says. “This is a moment of a great awakening to the feminine, and we are responding en masse. We’ve been living in a patriarchal system for thousands of years, where we had to develop our masculine side in order to survive. We had to learn to compete, for instance, and we had to forget our feminine essence.”

I met Luzclara in a medicine journey in Chile a few years ago. That same night, after I’d met her, she came to me in a dream as a condor. Over the next few days, I participated in fire circles, sweat lodge, sound healing, and a labyrinth ceremony that she led. I learned of her ways of viewing sexuality, menstruation, manifestation, healing, Pachamama, plant medicine, menopause, and magic. I also found out that the grand Condor is her totem, and that, before going to sleep, she gives her light body permission to travel. Luzclara has unforgettable presence and I’m looking forward to her landing at Los Angeles International Airport in a few days.  Responding to an email interview while taking a break in Saint-Tropez in the French Riviera, Luzclara explains that ancient ones said that the way energy enters the planet changes every two thousand years. Masculine energy entered Earth from the Himalayas, and now feminine energy is entering from the Andes mountain range. “Feminine energy is not just for women,” she says. “It’s for everyone, and it’s time for the feminine qualities to develop once again.”

Responding to an email interview while taking a break in Saint-Tropez in the French Riviera, Luzclara explains that ancient ones said that the way energy enters the planet changes every two thousand years. Masculine energy entered Earth from the Himalayas, and now feminine energy is entering from the Andes mountain range. “Feminine energy is not just for women,” she says. “It’s for everyone, and it’s time for the feminine qualities to develop once again.”

A native of Chile, Luzclara was mentored by an indigenous Mapuche Machi (shaman), Antonia Lincolaf, after the Machi came to her in a dream in 1981. Machi Antonia taught her how to hold ceremonies and how

Blog: La Bloga (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, nature, vision quest, shamanism, Add a tag

by tatiana de la tierraThe shamans shuttled us to a grove of almond trees for a 4-day, 4-night silent vision quest. They placed us each beneath an almond tree, far apart from each other. Here, we would commune with nature, sleep upon the earth, pray and meditate. We were instructed to put an altar at the eastern entrance of our space and to hang our tobacco prayer ties around the four corners. A tiny ceramic replica of Venus del Valdivia accompanied us, along with a cornhusk-rolled tobacco, which we had swept four times through the fire at the base camp. The fire, which would be tended to at all hours, would reflect our states of being and would alert the fire keepers if anything came up.

We were to live off of two apples, one pear, one avocado, one corn on the cob, a miniature chocolate bar, a handful of almonds and a gallon of water. We would pee on the ground and, with the little plastic shovel provided, we would dig a hole in the earth for bowel movements. Two in the group of ten women were menstruating; they were to bequeath their bloods upon Mother Earth. We were told to wear skirts for ceremony and not to read any books.

I wondered how many rules I’d break, and if I could make it through even one night.As the sun set behind the mountain, I scrambled to get my space in order. A bright pink piece of plastic was the “floor” of my “house”, which consisted of a twin air mattress, a sleeping bag and travel pillow, a duffle bag for nightclothes and another for day clothes. I also had two mochilas, one for health and beauty aids/writing tools and the other for my altar. Though we had only minutes to prepare, I skillfully crammed quite a lot of stuff to bring with me, leaving nothing to chance.

It was around 8 pm after I’d finished setting up and changing into flannel pajamas. With just a bit of daylight left, I set out to make the hole for going to the bathroom. It was to be deep enough to last all four days. I walked all over, crunching dry leaves and twigs in my path, searching for just the right place to squat. A place with a view, yet out of sight, and without spiky bushes and vines in the vicinity. There were many options, but all my attempts were futile. Dry, hard and rocky, the earth was impenetrable with a little plastic shovel. If only I had a pick and a sledgehammer, maybe I could swing it. Instead of one deep hole, I made several shallow ones. Yet I wondered if the other women were able to dig deep into the earth, and if I was just a lazy, inefficient, shit-hole digger.

Vision Quest Realization #1: I don’t know how to dig holes and am pretty clueless about appropriate tools for this or other means.

Blog: Playing by the book (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, Add a tag

This isn’t at all what I expected to do with my few minutes spare this morning before the children wake up, but I’ve been so moved by the images of the miners being rescued that I felt I had to mark the occasion somehow. So here is a list of some picture books based in Chile

Mia’s Story by Michael Foreman

Mia’s Story by Michael Foreman

Mia lives with her family in a small Chilean village beneath the snowy mountains. Their house is put together from the dumped rubbish of the city – it is not much of a place. One day, Mia’s father brings her a puppy, which she calls Poco because he’s so small. When Poco runs away, Mia travels far up into the mountains to search for him. There, she finds some white mountain flowers, growing under the stars, as well as something much more powerful – hope.

Mariana and the Merchild: A Folk Tale from Chile by Caroline Pitcher , illustrated by Jackie Morris

Mariana and the Merchild: A Folk Tale from Chile by Caroline Pitcher , illustrated by Jackie Morris

Old Mariana longs for friendship, but she is feared by the village children and fearful of the hungry sea-wolves hiding in the sea-caves near her hut. Then one day she finds a Merbaby inside a crabshell and at once she loves it more than life itself – although she knows that one day, when the sea is calm again, the Merchild’s mother will come to take her daughter back.

A Pen Pal for Max by Gloria Rand, illustrated by Ted Rand

A Pen Pal for Max by Gloria Rand, illustrated by Ted Rand

Maximiliano lives with his family on a farm in Chile. His father works in a vineyard that produces grapes for worldwide distribution. One day Max slips a note with his name, address, and a request for a pen pal into a box of the fruit. Amazingly, he receives a reply from 10-year-old Maggie, who lives in the U.S. They develop a correspondence comparing their very different lives. When an earthquake strikes Max’s part of the world, Maggie and her friends send supplies to his school.

Chile’s most famous writer (at least translated into English) is Isabel Allende, and she has written at least one book for (older) children – City of the Beasts.

Maria Eugenia Coeymans has written an interesting article available on the IBBY website entitled Searching for Identity: The presence of Cultural and Ethnic Heritage in Chilean Children’s Literature. The article’s biography references several Chilean children’s books (in Spanish).

Here’s hoping that the rescue continues safely and swiftly.

Blog: Shelf-employed (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, poetry, book review, family life, racism, J, abuse, booktalks, poets, bio, stuttering, indigenous peoples, Add a tag

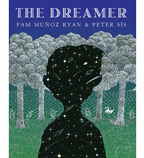

The Dreamer is a book that almost defies description. Is it poetry? Is it biography? Is it fiction? This fictional account of real life poet Pablo Neruda's childhood is all of these things. Born Neftalí Ricardo Reyes Basoalto, he was a shy, stuttering, skinny youngster with a larger-than-life domineering father. Working with Neruda's prose and poetry, along with anecdotes of his early life, Pam Muñoz Ryan invents the thoughts, hopes and dreams of the shy young man who quietly refuses to become the man his father wishes. With beautifully poetic language, she paints a portrait of a boy determined to be true to himself. This is a book for thinkers and dreamers and poets and all children who yearn to be nothing but themselves.

A better artist than Peter Sís could not possibly have been chosen for this book. The white spaces of his signature illustrations are filled with symbolism - the image of the small and frightened faces of Neftali and his sister swimming in an ocean whose shoreline is the outline of his domineering father speaks volumes without words. Illustrations are abundant throughout the book.

An illustrated, color discussion guide is available from Scholastic. Scholastic also offers this video booktalk, but this is a book that does better speaking for itself. It must be read to be appreciated.

If you've every searched for a story with a calm and caring stepmother, this is that book, too.

Other reviews @

Kids Lit

Dog Ear

Sha

Blog: La Bloga (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, travelogue, Thania Muñoz, Ruben Martinez, Add a tag

by Thania Muñoz

by Thania Muñoz

(Today's installment by Thania replaces Dan Olivas's usual Mon. post. He needed to attend to family. See Thania's first installment about her visit to South America here.)

Santiago de Chile is very cold. It has rained a few times and the city has been dealing not only with the regular winter season flu, but also the infamous “swine flu” or whatever name they have given to it now. Officials have advised people to be careful, to take care of themselves and avoid crowded places.

Not a lot people have followed this advice; everyone is out and about, downtown stores are crowded and bars and restaurants haven’t lost that much business. I’ve been taking care of myself. I avoid crowded places, but I still walk the streets of Santiago every day.

It’s funny. Santiago hasn’t changed a bit. I honestly thought I wasn’t going to be able to recognize places and people, but it hasn’t been that way; my friends say that I haven’t change a bit, either. I guess the three years since my last visit is not as long ago as I thought. I arrived on a rainy morning at “my family’s” house. They received me with warm sopaipillas, a traditional Chilean snack or appetizer that is fried and made out of flour, lard, pumpkin and salt. It's traditional for Chileans to eat them during the winter season, especially when it rains, because they are warm and delicious. It compares to having a cup of hot cocoa and cookies for us back in the states.

I arrived on a rainy morning at “my family’s” house. They received me with warm sopaipillas, a traditional Chilean snack or appetizer that is fried and made out of flour, lard, pumpkin and salt. It's traditional for Chileans to eat them during the winter season, especially when it rains, because they are warm and delicious. It compares to having a cup of hot cocoa and cookies for us back in the states.

Almost every day late in the afternoon we gather in the kitchen, waiting for the pastry to be taken out of the oil. Street vendors also sell them outside metro stops or at street corners, but as in most cases, homemade ones are exceptionally good. As I caught up with my family that morning, I had a few sopaipillas and a cup of warm tea.

The first time I went to Chile I lived with the Arteaga family for six months and after all the good times we spent together I now consider them my family. Back then they used to rent out rooms of their house to students from places like England, Haiti, Germany, Perú, Brazil and Chile.

Living with the Arteaga family is one of my most cherished memories. They taught me all there is to know about Chilean culture. The Arteaga sons were one of my many idioms--bad words included--instructors. I still remember how I used to write down words I heard in school and read the whole list to them when I got home. After a few laughs, they’d explained them to me with detail and examples. I’m a quick learner when it comes to idioms. Some easy ones include “flaite” or “cuico,” and some of the hard ones, “agarrar pa'l leseo,” “barsa,” “fome.” Any guesses?

The Arteaga family is originally from southern Chile, from a town called Los Angeles (yes, as in California), and during the summer I went on vacation with them to meet the rest of the family. Mr. Arteaga’s family has a “fundo” there, a house in the country or a rancho, with a brick oven, next to a river. I went during the summer so during the day everyone would go swimming or sunbathing at the river.

At night we sang, played the guitar and some of the older ladies even gave “cueca” lessons, Chile’s national dance. During this trip I ate and drank traditional Chilean food: warm “humitas” (similar to Mexican tamales) that are usually eaten with chopped tomatoes and sugar on top; drinks such as a homemade white wine mixed with blended strawberries, and “chicha,” a fermented drink made of grapes or other fruits.

When I started this post I didn’t intend to write about food, but being here has brought back all those wonderful memories. As of now, I’m almost done eating a cheese empanada, and later I’m going to Paseo Ahumada, a lively and crowded pedestrian street downtown to buy some sweetened warm peanuts. Enrique Lihn, a Chilean poet, has a wonderful book of poetry named after this street:

Que los que se paren,I’ll stop at this point and maybe hear the horse’s neigh.

en Ahumada con la Alameda,

escuchen si corre un poco de aire,

el relincho del caballo de Bernardo O’Higgins.

(Paseo Ahumada, 1983)

Thania Muñoz

de Santiago

p.d.: Dieting is forbidden in Chile, I swear.

________________________

Featuring Joe Garcia, with Ruben Gonzalez and John Schayer.

An evening of spoken word and music (with a band!)—material from my book-in-progress on the Desert West and Borderlands.

CENTRAL LIBRARY • Mark Taper Auditorium

Fifth & Flower Streets, Downtown L.A.

PARKING: 524 S. Flower St. Garage

Visions in the Desert: Searching for Home in the West

Writer Ruben Martinez, accompanied by his longtime musical partner, explores some of the oldest American symbols and the newest motley cast of characters to confront them.

(Please note, reservations strongly recommended!)

Peace,

Rubén Martínez

Blog: Alethea Eason (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, travel in Chile, Alethea Eason author of Hungry, travel in South America, Antofagasta, Atacama Desert, Add a tag

Lonely Planet says there's not much to see as you travel through the desert between La Serena and Antofagasta, suggesting that a night bus is a good idea. The guidebook can be helpful but is so wrong on this account. The entire trip was fascinating as the vastness of the Atacama Desert, the driest place in the world, unrolled around us.

Lonely Planet says there's not much to see as you travel through the desert between La Serena and Antofagasta, suggesting that a night bus is a good idea. The guidebook can be helpful but is so wrong on this account. The entire trip was fascinating as the vastness of the Atacama Desert, the driest place in the world, unrolled around us.

We spent the first night of our trip in La Serena, where we have visited twice before, a lovely town about seven hours north of Vina del Mar. The next day we climbed out of the city and watched the ocean fog lace the top of the hills. El Parque National Bosque de Fray Jorge is located south of La Serena and is the only rainforest on Earth where it never rains. The dense camanchaca provides enough moisture for unique trees and plants to grow. Fog is a common companion to the coast of northern Chile, modulating the heat and creating moderate temperatures along the edge of this desert.

Outside of La Serana, the hills are speckled with cactus which look like cousins to the Suroro in Arizona. They shrank as our bus went inland and away from the fog, until only mesquite was left.

Even these became more sparse and disappeared.

Memorials like this are seen every few miles.

Soon the desert was "empty." Sand stretched beneath mountains molded through geological ages. Volcanic ridges rippled at their feet. Mining in the north of Chile, especially copper mines, is what makes the Chilean economy churn. Copper prices have dropped dramatically over the last year, but there still is profit in it. We passed several operations, the only human interruptions in hours of moonscapes, and then finally arrived late in Antofagasta. The city is huge, stretching for several kilometers along the coast. Antofagasta was founded in 1869 by Bolivia to serve as its main outlet for its mining industry. Chile seized it a decade or so later, and it's still referred to as "captive province" by Bolivians. According to Wikipedia, the city receives only 4 millimeters of rain a year on average, and for forty years it never rained at all.

Mining in the north of Chile, especially copper mines, is what makes the Chilean economy churn. Copper prices have dropped dramatically over the last year, but there still is profit in it. We passed several operations, the only human interruptions in hours of moonscapes, and then finally arrived late in Antofagasta. The city is huge, stretching for several kilometers along the coast. Antofagasta was founded in 1869 by Bolivia to serve as its main outlet for its mining industry. Chile seized it a decade or so later, and it's still referred to as "captive province" by Bolivians. According to Wikipedia, the city receives only 4 millimeters of rain a year on average, and for forty years it never rained at all.

It was close to midnight, but the bus station and the streets were thick with crowds, car alarms, diesel fumes and barkers selling you-name-it. We dragge

Blog: Alethea Eason (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, ex patriates in Chile, Alethea Eason author of Hungry, New Years in Valparaiso, Fireworks in Valparaiso, Add a tag

Valparaiso's firework display for New Years is world renowned. Every year there are several displays that run up the coast for thirty or forty kilometers from Valparaiso to Concon, the community we live in. Instead of staying home, we joined our friends Norm, Charlene and Susana to view the fireworks on the rooftop of the Shuttleworth's apartment on Cerro Placeres.

This is the Esmeralda, lit up for the night. Fifteen naval cadets are chosen each year to train on her as they sail around the world. The ship is a replica of the one on which Los Heroes fought and died in the Battle of Iquique against Peru during the War of the Pacific (against both Peru and Bolivia) in 1879.

Resentments still exist as Chile, with the aid of Great Britian, after having lost the battle won the war, and annexed a huge swath of coastline that belonged to the other two countries, taking away Bolivia's access to a seaport. At that time, nitrate was being exported from huge guano deposits in this area. Chile got the coast and the revenue from the nitrate. Chile has offered Bolivia rail access to use its ports, but Bolivia has declined. I have a norteamericana friend who moved to Bolivia with her husband about the same time we came here. I asked if they would ever consider Chile. She said no, her husband's family would never forgive them.

On the roof we had plenty of champagne (as demonstrated above by Susana) which unfortunately mixed with the sewage smells wafting off the ventilation system. If we were to be here next year, Susana tells us the place to be is in the streets where people dance all night long. Still, I enjoy smaller settings and was satisfied with the view we had of the whole bay and coastline, the feast we shared, and the way we finished our evening with quiet conversation on their balcony listening to the sounds of the city below. Norm and Charlene will be returning to Canada in two weeks; both Bill and I will miss sharing our adventures and misadventures as extranjeros here. We've made friends for life.

Charlene and me

Susana, Bill and I walked down Cerro Placeres, through the dusty plaza and the streets blowing our New Years horns, which elicited a spicy comment to my husband from an elderly senora sitting on her front steps . . . much of Chilean humor has a sexual base. We past parties set on other rooftops lit with fairy lights and vibrating with loud music. The ever

Blog: Alethea Eason (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: teaching in Chile, Hungry by Alethea Eason, travel in Santiago, teaching in Chile, Hungry by Alethea Eason, travel in Santiago, Chile, Add a tag

I love the murals in Santiago. The city is covered with the same kind of tagging as any urban place in America, but the level of creativity seems to be higher here. Amid what looks like gang graffiti there are message like this. Respect is to love. The magic is in your soul. I like the vampirish like creatures looking on, as though the forces of darkness were taking heed of the message. There are occasional messages on walls proclaiming: Capitalismo es muerte. Other pictures that are intricate and fanciful lace the streets. In the Bellas Artes area, near San Cristobal, the highest part of the city, and where one of Neruda's three homes is located, the mural art is taken to the highest levels, street after street, in a neighborhood full of houses where color and whimsy cry out.

Bill and I went to the immigration office today. The nicest people work there. I was told that St. Margaret's is the "most prestigious school in Chile." Yikes! Definitely not like the Title One schools I've always taught at. We panicked when the forms and procedures were explained to even get a work permit under a tourist visa. Send my teaching credentials to the consulate in San Francisco just to get a stamp and from where they have to be mailed back to Chile?) But then I finally connected with the Sra. Avril Cooper, the director of the school, who said,"Relax, relax. Our people are working on it." Okay, sounded like good advice to us. So I'm sitting in a courytard writing now at La Casa Roja instead of dealing with bureaucracy. Que beuno! (I need to find how to transform my keyboard in a Spanish one but that's a learning curve I just can't take on right now.)

We went to lunch yesterday and today at two sidewalk cafes. A cute little dog, kind of a cocker spaniel/dachshund cross showed up at our feet yesterday. Small and sad. We thought she was a puppy until we noticed she'd recently had babies. We named her "Cute Little F . . ." Amazingly, there she was again today, at least two miles away. She had to have crossed the freeway, going up the steps and across the bridge along with people traffic. She came immediately to our table, lay down, and fell asleep again. We chose not to think of it as a sign, as we're weak where in the cute little doggy area of life. And we need to get Wiley down here. He'd probably be p.o.ed to see a strange dog in what he'd rightfully think of as his place. After today, I'm not sure how much blogging I'll do. after today My job starts Monday (trying not to panic-- I left a lot of my standby teaching material at home because of weight limitations on the airplane). Our house in Vina is cute, but not the place we want to stay forever. We don't want to connect Internet up, only for the two months we'll be there. I may spend a lot of time on the weekend at the Internet place around the corner, but I could also be correcting papers. Oh yeah, i've got another novel to finish.

One last thing! Great news. Nicole, the publicity person at HarperCollins told me that a review posted by Emily Robbins, a thirteen year old reviewers from Readers Views, was picked up by Reuters and usatoday.com. I can't stop smiling!

Blog: Alethea Eason (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: vina del mar, la casa roja, HUNGRY, teaching in foreign countries, vina del mar, la casa roja, teaching in foreign countries, Chile, HUNGRY, Add a tag

I chose this picture, though it has nothing to do with Santiago. It does have a lot to do with being willing to venture to unfamiliar places both without and within. Thank you, Mother Eve, for taking the first bite to a realized life.

We have been in Chile for just over a day. I'm sitting in an upstairs lobby of La Caja Roja, a hostel full of mostly young people from all over the world. Loud music is blasting from downstairs. Voices of guests eating their dinners on the patio blend in, along with clinking plates and laughter. Here, it doesn't feel I'm half a world away from winter, where the bells of my school ring, and my commute is driving up a mountain road. The Germanic orderliness that the United States possesses isn't found in Chile.

Bill and I stayed at this hostel for two of the weeks we spent here in July, so coming back felt like coming home in many ways. Out on the streets of the city, though, walking among the blankets spread full of bolsas and zapatos for sell, the crazy traffic, having a poor mother sing a song for some pesos to feed her baby, the reality that I have made a commitment to a strange new life is impossible to ignore.

Ice cream is a real highlight. It's simply wonderful, very similar to gelato. Most of the pastries, on the other hand, are heavy and unappealing-- which is a good thing because I have a weakness for them. I'd rather spend my dessert calories on the helados.

Took a trip to Vina del Mar today to rent a house that we found out about back home. Outside of Santiago, it becomes desert-like, similar to the few un-watered parts of southern California that remain. We passed chapparal and chemise, vineyards in the Casablanca Valley, slums on Valparaiso's hills.

Chile is a poor country with an expanding "middle class," however you might define it, and the wealthy whose homes could be anywhere in tonier areas of the states. Our new house is where a purse being snatched won't be out of the question, but that's probably the worst of worries. I wish my work clothes had deeper pockets to hide my i.d. and what little money I'll carry. I'll travel by bus or taxi to St. Margaret's, which has a gate models on Buckingham Palace, teaching girls who go home to fine houses, mas rica que mi casa.

I've stepped out of the "garden," of what I have always known, into a world where more knowledge and experience will be gained.

I need to work on my book, but so much nicer right now to put my thoughts here.

Tags: chile, hungry, la casa roja, teaching in foreign countries, vina del mar

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: chile, oxford, Geography, A-Featured, Ben's Place of the Week, map, atlas, ben, oupblog, keene, santiago, valdivia, mapocho, extremadura, conquistador, chileans, nueva, Add a tag

Santiago, Chile

Coordinates: 33 26 S 70 40 W

Population: 5,623,000 (2007 est.)

For Chileans, February 12th marks an important moment in the history of their country. On this day in 1541, Pedro de Valdivia, a Spanish conquistador, founded Santiago de Nueva Extremadura on Saint Lucia Hill overlooking the Mapocho River. Present-day Santiago eventually grew to fill most of the basin of the same name and currently ranks as the sixth largest city in South American and the tenth most populous in the Western Hemisphere. (more…)

Blog: Alethea Eason (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: HUNGRY, La Serena, Maria's Casa, Chile, HUNGRY, La Serena, Maria's Casa, Add a tag

After the Yo Yo, Marie's Casa (and that's what the sign said, not La Casa de Maria as the cab drivers would know it) was marvelous. Clean. Fresh. BUT COLD. This is where the really cold weather hit and nights were nippy! The computer was outside so fingers were freezing as they were typing! Plus, I caught a cold that I passed on to Bill the following week.

The picture above is of Pancho who is a shoemaker. He has a shop at the hostel. There's Bill, too. Pancho is fixing Bill's belt. Just as the Lonely Planet Guide Book says, Maria clucks and sweetly frets over all of her guests. Andres picks you up at the bus station if you let the hostel know you're coming, but its only two blocks away. Olga, the housekeeper, and I really bonded, as I did with Nichole, a German engineer and a frequent guest, who works on water issues in the region. It was very hard to say good bye because we were made to feel like we were home.

Blog: Alethea Eason (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: HUNGRY, travel in Chile, Santiago, Chile, HUNGRY, travel in Chile, Santiago, Add a tag

Here is my husband Bill, self proclaimed barbarian, playing guitar upstairs at La Casa Roja. Notice the high ceilings. The hostel was once a mansion, and Simon, the owner, has worked hard to restore the building and to provide all sorts of services for its guests, including ski trips to the Andes.

Here is my husband Bill, self proclaimed barbarian, playing guitar upstairs at La Casa Roja. Notice the high ceilings. The hostel was once a mansion, and Simon, the owner, has worked hard to restore the building and to provide all sorts of services for its guests, including ski trips to the Andes.

I was amazed at all the young people from England, Ireland, Australia, and Germany who are traveling around the world. It seems to be a rite of passage to finish school, or take a break during college, and to get a ticket that allows them to stop where they like, as long as they keep going in the same direction. There were VERY few Americans and Canadians, and the ones we met were generally a bit older, often teachers visiting Chile during "summer" break. I loved hearing different languages spoken as I'd walk through the halls. Snowboarders from Spain next door to our room drunkenly sang in Catalan a couple of nights. Very rowdy, but nice young men, all the same.

Most of these young people were visiting many of the countries in South America. A young woman from Israel volunteered at an animal sanctuary in Bolivia. On Bill's trip in February, he met a Danish woman who had worked at the same place whose responsibility was to walk a puma on a leash through the rain forest. Traveling from hostel to hostel, friendships are made; people meet up with each other quite frequently. Going to Bolivia seems to be must do, as well as Peru. I heard wonderful things about countries like Colombia, where I'd be hesitant to visit. A young woman from Australia said it was her favorite country and "only heard gunfire one night in my hammock."

According to the Lonely Planet Guidebook, Santiago is one of the safest big cities in South America. In certain areas, "starving students" might ask you to buy a poem that they have "written." Be aware. Take pictures, but don't be flashy as a tourist, and chances are there won't be any hassles.

The city rises on a plain up to the foothills of the Andes; the higher in elevation, the more wealthy the neighborhood. The Barrio Brasil, where we stayed, is near Santiago Central, and long ago was where the wealthy lived. Over time, it fell into decline, but now it's experiencing a revival, kind of a South of Market thing that has happened in San Francisco. I grew to love it because of the atmosphere of the neo-colonial buildings, the energy of the university students who seemed to be everywhere, the wonderful park where children played late at night, and the coffee we found in cafes.

Bill and I probably walked at least five miles a day. We'd head from La Casa Roja to Central where the Palacio De Moneda, the presidential palace, is. The financial sector and shopping areas are found here, too. I felt I was in Europe as I walked along the streets. By the way, street vendors sell wonderful sweaters, shawls, and scarves made from soft non-scratchy alpaca, as well as jewelry, often made from lapis lazuli.

We strolled down the Ahumada, a pedestrian thoroughfare full of stores, street vendors, musicians, and acrobats to the Plaza De Armas. The first day we were there, there was a gay pride celebration with a drag queen singing. Another time, there was traditional music and dancing, and the last visit we listened to the band of the Carboneros, the Chilean police.

We walked through the Mercado Central. The first building was a fish market, with restaurants. Acres of fish of all sorts. The second building had acres of fruits and vegetables. Cutting through Bellavista, we ended up at Cerro San Cristobal, the highest point in the city. This is a view of Santiago from an funicular that takes people almost to the top.

Can you see the smog? The first day I was there, I could taste it. It reminded me of growing up in southern California, but winter is the time of the year when smog gets worse. I joked that it was a southern hemisphere phenomenon where things were opposite from California. Actually, the Andes are so nearby that the cold air doesn't rise, but gets compacted in the basin. Smog settles in. Unless it rains, that is. Right before we left, a cold front came through, leaving snow in Lo Barnechea, the highest part of the city. Our last day was glorious: crisp air, bright blue skies, and I felt I could reach my arm out to touch the Andes. (Here's a shot from the fruit market. Bill bought a kilo of kiwi for about 250 pesos, about 50 cents.)

(Here's a shot from the fruit market. Bill bought a kilo of kiwi for about 250 pesos, about 50 cents.)

We climbed to the top of San Cristobal. I went into the chapel and said a centering prayer while Bill waited for me. Good thing because we then rode down the mountain in a sky bucket, a long steep ride with a magnificent view which I enjoyed as I clasped my seat with an iron grip.

Then we "landed" in Provedencia and took the subway back to Barrio Brasil. Over a million people a day ride the subway in Santiago. It's a great way to travel during off-peek hours, though I practiced breathing calmly during rush hour when we were squished. BUT that brings me to one of the things I loved the most. People were unfailingly polite. I loved hearing the gently sound of "permiso" as people squeezed through others as they got off.

Graffiti was everywhere. I started to look on the it as art, but one of the biggest pleasures was turning a corner and finding wonderful murals like this. The Bellavista area, in particular, abounded with houses that were true works of art.

Bill frequently mentions that Chile is in its springtime. Chile has the highest standard of living in South America; though poverty is a still an issue, the country has recovered from it's dark era of repression and is going at full throttle to take its place as a modern democratic country.![]()

Blog: Alethea Eason (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, home, HUNGRY, Add a tag

I've been craving chocolate. Grumpiness level moderately high. Fell asleep yesterday at four p.m. and slept (almost) through until six this morning. Sure signs summer vacation is sorely needed.

Bill's hammering, putting stained glass panels above our sink. He's been painting our house white and laying paving stones and redoing the deck. Working on the house in case we decide to move. We're off to Chile later this month to see if I fall in love with the country as much as he did when he went earlier this year. I haven't put away my winter clothes. The temperature in Santiago was down to freezing last night.

If we decided to live in Chile, it won't be for at least another year, though the changes we're doing (I'm using the royal "we" here, as Bill's the craftsman) will make it hard to give up this place. I found the countdown clock for my novel HUNGRY on my HarperCollins' page this afternoon, and I only have a millions things to do before October!

I'm a fretter by nature. Will kids really like the book? Will some parents be concerned their children are reading about a girl who might have her best friend for a snack? As charming as I think Deborah is, will others feel the same way?

At my church (come on by: http://stjohnslakeportparish.googlepages.com) or at meetings in the diocese, people ask me what the book's about, and I say, "Flesh eating aliens;" no one has crossed themselves or pulled out a crucifix. So far everyone has laughed. I always add: HUNGRY is about a girl who has to struggle with the values of her home and culture and the difficulty of doing the right thing.

I'm glad we're going away. Working on preparation for the publication in Internet cafes in South America probably is the best thing that could happen to me! Plus, I'll be in a new atmosphere to start seriously writing a new book.

Blog: La Bloga (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, poetry, Espada, Add a tag

Martín Espada's Republic of Poetry reminds me of Oscar de la Hoya's boxing. Beautiful to behold, it's unerring in its aim. Pared down to the essential--it's body blows to the chest, to the gut, head blows that annihilate the opponent and leave the viewer stunned, reeling, gasping for air.

Democracy subverted in Chile and by implication, everywhere, reverberates on every page. The Republic of Poetry is not an elegy, it's an upper cut to complacency, a left hook to amnesia. Wake up, remember what was, see what's happening right in front of you.

The comparison of Espada to Neruda, to Whitman are many, but to me, what comes to mind is poet warrior, able to fight and raise an army with the power of his words. But in case you're not convinced, here is some additional praise for this remarkable book.

“What a tender, marvelous collection. First, that broken, glorious journey into the redemptive heart of my Chile, and then, as if that had not been enough, the many gates of epiphanies and sorrows being opened again and again, over and over.” —Ariel Dorfman

“Martín Espada is a poet of annunciation and denunciation, a bridge between Whitman and Neruda, a conscientious objector in the war of silence.” —Ilan Stavans

“Martín Espada’s big-hearted poems reconfirm ‘The Republic of Poetry’ that (dares) to insist upon its dreams of justice and mercy even during the age of perpetual war.” —Sam Hamill

“Martín Espada is indeed a worthy prophet for a better world.” —Rigoberto González

This is tight, muscular writing. Espada make his point with an economy of language, concealing a dense terrain of imagery and meaning. In this universe, the dead are not ghosts, but fully fleshed--staving off the soldiers, marching in the battlefield, struggling in the streets, and inspiring new generations. Read these and you'll see what I mean.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Soldiers in the GardenIsla Negra, Chile, September 1973

After the coup,

the soldiers appeared

in Neruda’s garden one night,

raising lanterns to interrogate the trees,

cursing at the rocks that tripped them.

From the bedroom window

they could have been

the conquistadores of drowned galleons,

back from the sea to finish

plundering the coast.

The poet was dying:

cancer flashed through his body

and left him rolling in the bed to kill the flames.

Still, when the lieutenant stormed upstairs,

Neruda faced him and said:

There is only one danger for you here: poetry.

The lieutenant brought his helmet to his chest,

apologized to señor Neruda

and squeezed himself back down the stairs.

The lanterns dissolved one by one from the trees.

For thirty years

we have been searching

for another incantation

to make the soldiers

vanish from the garden.

The soldier leaves, not because the poet is super human, but because he's supremely human. Poetry taps into a power that no bullet can halt nor cancer eat away. Armies of everyday people have been set loose with words like Neruda's. Then and now, the men in power with bloody hands know it's dangerous, know it's subversive. But in the end, it remains unstoppable.

Black Islands

for Darío

At Isla Negra,

between Neruda’s tomb

and the anchor in the garden,

a man with stonecutter’s hands

lifted up his boy of five

so the boy’s eyes could search mine.

The boy’s eyes were black olives.

Son, the father said, this is a poet,

like Pablo Neruda.

The boy’s eyes were black glass.

My son is called Darío,

for the poet of Nicaragua,

the father said.

The boy’s eyes were black stones.

The boy said nothing,

searching my face for poetry,

searching my eyes for his own eyes.

The boy’s eyes were black islands.

What possibility dwells in those black eyes? What page of history will be written for him to read, and what page will he write himself? Knowing that Espada is a father, I can only imagine how many times he's asked himself those questions in the still hours of the night, watching his own child sleep. Toward the end of The Republic of Poetry, Espada meditates on the "smaller" world of family and relationships, personal joy and private grief. Every fighter has his scars, and every poet, his pleasures.

Now, stop reading this, it won't get the job done. Go. Get the book. Read that instead. It's time to wake up.

Republic of Poetry

W. W. Norton

- ISBN-10: 0393062562

- ISBN-13: 978-0393062564

READINGS:

Admission is free but reservations are required.

March 15: Reading, 6 PM

Poetry Off the Shelf

sponsored by the Poetry Foundation

Newberry Library

60 W. Walton Street

Chicago, IL

Contact: Steve Young

(312) 787-7070

March 16: Reading, 8 PM

English Language and Literature Conference

St. Francis University

500 Wilcox Street

Moser Performing Arts Center Auditorium

Joliet, IL

Contact: Marcia Marzec

(800) 735-7500

March 17: Plenary, 9 AM

English Language and Literature Conference

St. Francis University

500 Wilcox Street

Moser Performing Arts Center Auditorium

Joliet, IL

Contact: Marcia Marzec

(800) 735-7500

written by: Lisa Alvarado

Blog: La Bloga (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Chile, poetry, community building, social commentary, Add a tag

La Bloga is pleased to offer you our discussion with Martín Espada, whom Sandra Cisneros called "the Pablo Neruda of North American authors."

In his eighth collection of poems, Martín Espada celebrates the power of poetry itself. The Republic of Poetry is a place of odes and elegies, collective memory and hidden history, miraculous happenings and redemptive justice. Here poets return from the dead, visit in dreams, even rent a helicopter to drop poems on bookmarks. (from the publisher)

Espada was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1957. He has published thirteen books in all as a poet, essayist, editor and translator. His eighth collection of poems, The Republic of Poetry, was published by Norton in October, 2006. Of this new collection, Samuel Hazo writes: "Espada unites in these poems the fierce allegiances of Latin American poetry to freedom and glory with the democratic tradition of Whitman, and the result is a poetry of fire and passionate intelligence."

His last book, Alabanza: New and Selected Poems, 1982-2002 (Norton, 2003), received the Paterson Award for Sustained Literary Achievement and was named an American Library Association Notable Book of the Year. An earlier collection, Imagine the Angels of Bread (Norton, 1996), won an American Book Award and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Other books of poetry include A Mayan Astronomer in Hell’s Kitchen (Norton, 2000), City of Coughing and Dead Radiators (Norton, 1993), and Rebellion is the Circle of a Lover’s Hands (Curbstone, 1990).

He has received numerous awards and fellowships, including the Robert Creeley Award, the Antonia Pantoja Award, an Independent Publisher Book Award, a Gustavus Myers Outstanding Book Award, the Charity Randall Citation, the Paterson Poetry Prize, the PEN/Revson Fellowship and two NEA Fellowships. He recently received a 2006 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship.

His poems have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times Book Review, Harper’s, The Nation, and The Best American Poetry. He has also published a collection of essays, Zapata’s Disciple (South End, 1998); edited two anthologies, Poetry Like Bread: Poets of the Political Imagination from Curbstone Press (Curbstone, 1994) and El Coro: A Chorus of Latino and Latina Poetry (University of Massachusetts, 1997); and released an audiobook of poetry on CD, called Now the Dead will Dance the Mambo (Leapfrog, 2004).

Much of his poetry arises from his Puerto Rican heritage and his work experiences, ranging from bouncer to tenant lawyer. Espada is a professor in the Department of English at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, where he teaches creative writing and the work of Pablo Neruda.

In next week's column, I'll review The Republic of Poetry and let you in on exactly why the work of Martín Espada is an object lesson in writing.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Mainstream American history is, more often than not, a kind of forced amnesia. Do you agree/disagree? What to you think the role of the poet is regarding this? Can you talk about the significance of the title, The Republic of Poetry, in this vein?

The American history taught and published in this country all too often resembles a consensus on what to forget. This is especially true when it comes to Latinos, Latin America, and their history. I believe that a poet can be a historian when the need is there.

There is a tradition of poet as historian in Latin America. Pablo Neruda’s Canto General is a history of Latin America in verse, magnificent and sweeping in scale. Ernesto Cardenal wrote epic poems about the history of Nicaragua, the Somoza dynasty and the rise of Sandino, the invasion of William Walker. This is not the official history. This is hidden history, history from below, a poet’s history. Likewise, in The Republic of Poetry I write about the coup in Chile, struggle for democracy in that country, and the dynamic presence of poetry in the transition of democracy. The Republic of Poetry is, on the most literal level, a reference to Chile, but the Republic of Poetry is everywhere people write and speak and sing their hidden or forgotten history.

What, in your opinion, is the importance of revisiting the Chilean overthrow, particularly, given current U.S. foreign policy?

Most people in the U.S. never knew what happened in Chile. Others knew and forgot. It’s been more than thirty years, since September 11th, 1973, “the first 9/11.” We never hear about Nixon, Kissinger, and the CIA as co-conspirators in the overthrow of a democratically elected president—Salvador Allende—in Chile. We never hear about their complicity in the murder of more than 3000 people, the torture and imprisonment of thousands more. Kissinger is still hailed as a hero by the fawning media in this country. Meanwhile, no one mentions Victor Jara, the great singer and songwriter executed by the Chilean military in the days following the coup.

There are, of course, parallels with current U.S. foreign policy. As U.S. citizens, too many of us are detached and distant from the suffering our government causes half a world away, and we pay for it with our tax dollars. There are other parallels as well. The current debate over the practice of torture and arbitrary imprisonment in the name of security, illusory as it is, has eerie echoes of the Chilean coup and the Pinochet dictatorship. Today we stand by and allow our civil liberties to be eroded and delude ourselves with a mantra: It can’t happen here. Keep in mind that Chile had a long tradition of democracy before the coup. It couldn’t happen there, either. We have much to learn from Chile in its transition from dictatorship to democracy, their arc of creation, destruction and redemption.

You held many different jobs along the way. How do you think that's influenced how you look at the world, as well as the role of the poet/writer. In the same vein, do you think there is a working class aesthetic? If so, how would you define it and describe its importance?

It’s true I’ve held many jobs along the way. I was a bouncer in a bar; I was a door-to-door encyclopedia salesman; I was a janitor at Sears; I was a gas-station attendant; I was a pizza cook and dishwasher. I even worked in a primate lab, taking care of baby monkeys. I’m the only poet you’ll ever meet who has been bitten by a monkey. These work experiences have had a profound impact on my poetry, both in terms of subject matter and perspective. For many years, I was a poet-spy. I was invisible, like many working class people. People would say or do absolutely anything right in front of me, since I wasn’t really there. And I would write it all down.

I would say that there is definitely a working-class aesthetic. (To see what I mean, check out the anthology called American Working Class Literature, edited by Coles and Zandy for Oxford University Press.) As the term implies, working-class poets write about work and they write about class, as physical, emotional and intellectual landscapes. There is protest, but there is also pride in the job well-done; there is humiliation, but there is also dignity; there is anger, but there is also humor, all from the perspective of those who create and produce, but who do not control the system of creation and production. They speak from experience, and speak for the experiences of others who have been silenced or who silence themselves. Working-class poets make the invisible visible. A century ago there were Wobbly bards, poets and songwriters like Joe Hill and Ralph Chaplin; in the 1970s we saw the emergence of Chicano bards writing from the farmworker experience, such as Gary Soto and Tino Villanueva; now the bards will come from the immigrants and their children who increasingly make up new working class in this country today.

A poet labors over a message until it feels just right, then sends the words out to be read, understood, misunderstood, distorted, cavorted with. Who's responsible for how a poem means, the reader or the writer? A related question: To whom does a poem belong, the reader or the writer?

I would say that the writer is primarily responsible for “how a poem means.” As a poet, I have a responsibility to communicate. As I’ve said elsewhere, how could I know what I know and not tell what I know? Personally, I strive for clarity and concreteness, though I don’t feel the need to sacrifice complexity in the process. I rely on the image, the five senses on paper, to drive the narrative. I believe, as Julio Marzan has said, that the poem must be portable. It must be able to travel without the poet. I can’t be there to read the poem aloud to everyone, to explain it, to answer questions about it. The poem must be able to stand on its own, independently, and that’s my job.

Having said that, I would also say that once the poem leaves me and takes flight, it belongs to the reader. I want my poems to be useful. I’m gratified when my poems go where I can’t go, to weddings or funerals, to prison, to other countries in other languages. (I’ve been translated into Turkish!) Sometimes readers let me know, in dramatic ways, that the poems belong to them. I met a young journalist at a reading in New York who had a quote from “Imagine the Angels of Bread” tattooed on his leg.

It's obvious that Neruda's work is bedrock for you. Who are other writers that have significantly influenced you?

Neruda is part of a great tradition going back to Whitman. I’m part of that tradition too. Whitman has significantly influenced me, as have others in Whitman’s lineage: Hughes, Sandburg, Masters, Ginsberg, Cardenal. I should also cite the Puerto Rican poet Clemente Soto Velez. He spent six years in prison for his role in the Puerto Rican independence movement, and later mentored generations of writers and artists in the community, myself included. My wife and I named our son after him.

How has being a father and husband influenced your life as a poet and vice versa?

Being a father and husband have certainly influenced my life as a poet, as any important and intimate relationships would. Being a husband and father gives me a far greater stake in a more just world, and this is reflected in my work.

I’ve written many poems about them. There is a poem about my son’s birth, and another about my wife’s stroke. For them this is a mixed blessing, as anyone who has been the subject of such a poem can attest. My life as a poet, doing readings and workshops on the road, also takes me away from my family. The unfortunate truth is that people pay me to go away.

What's something you'd like your readership to know about you that isn't in the official bio?

I am the inventor of the all-pork diet.

(photo credit: Paul Shoul)

READINGS:

Admission is free but reservations are required.

March 15: Reading, 6 PM

Poetry Off the Shelf

sponsored by the Poetry Foundation

Newberry Library

60 W. Walton Street

Chicago, IL

Contact: Steve Young

(312) 787-7070

March 16: Reading, 8 PM

English Language and Literature Conference

St. Francis University

500 Wilcox Street

Moser Performing Arts Center Auditorium

Joliet, IL

Contact: Marcia Marzec

(800) 735-7500

March 17: Plenary, 9 AM

English Language and Literature Conference

St. Francis University

500 Wilcox Street

Moser Performing Arts Center Auditorium

Joliet, IL

Contact: Marcia Marzec

(800) 735-7500

interview: Lisa Alvarado

Blog: La Bloga (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Isabel Allende, Chile, guest columnist, Add a tag

Author: Isabel Allende

Publisher: HarperCollins Rayo

ISBN 13: 978-0061161537

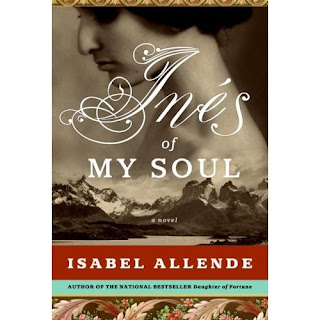

I’m a Chicana. I am a Danzante Azteca, an Aztec Dancer. To me, all conquistadors were monsters. I’ve hated them, Hernan Cortez in particular for as long as I can remember. I knew nothing about the conquistadores of Chile, nor did I care to. I knew all I wanted to about the conquistadores, their brutality, the violence and genocide done to my people 500 years ago. I knew all I wanted to and that was the end of it. Or so I thought.

I took my time about reading Inés of My Soul. I wanted to read it, it sat in my shelf for more than a month but something always stopped me. Then one day as I was getting ready for work, I picked it up and turned the page. That was it for me. Needless to say, I never did make it in to work that day. I stayed in my room and read Inés’ story until I finished the book. Then I read it again. Isabel Allende has that effect on me. Her books make me think, make me absorb them, take them in until the words almost become part of my DNA. I am always in awe of her writing, always amazed and always, always transfixed and held captive in her world of words. Inés of My Soul did that to me. Not only that, it did something bigger. Huge.

Inés of My Soul was an epiphany for me. It made me think of the conquistadores in a radically different way. It made me see their humanity. Los Conquistadores human? That they had beliefs, loves, losses, dreams and hopes. Wow. It had never before entered my mind that they would have feelings. To me, they were just the monsters that came, stole, raped and pillaged. I never once considered that they were human beings. I still think they were wrong and I still believe they were murderers and rapists. The only change was that I know see their humanity.

Inés of My Soul is the story of Doña Inés Suárez (1507– 1580), a poor seamstress in Spain who goes to Peru to track down her cheating husband only to find that he has died in battle and then goes on to become the first lady of Chile. In this grand historical fiction, she is writing her memoirs in the year of her death. She tells of her girlhood in Spain, of her love for the cheating husband Juan de Málaga “one of those handsome, happy men no woman can resist at first, but later wishes another woman would win away because he causes so much pain" and of her decision to stay in Peru. She travels, she fights, becomes a nurse to the wounded, even fights in battle against various indigenous tribes.

There are bloody and vicious battles, romance, cruelty, trials and tribulations. Inés then falls in love with Pedro de Valdivia and travels with him to Chile where they set about conquering the land and making a home there. She tells her stepdaughter from her second marriage, "I beg you to have a little patience, Isabel. You will soon see that this disorderly narrative will come to the moment when my path crosses that of Pedro de Valdivia and the epic I want to tell you about begins. Before that, I had been an insignificant seamstress in Plasencia, like the hundreds and hundreds of hardworking women who came here before and will come after me. With Pedro de Valdivia I lived a life of legend, and with him I conquered a kingdom. Although I adored Rodrigo de Quiroga, your father, and lived with him thirty years, the only real reason for telling my story is the conquest of Chile, which I shared with Pedro de Valdivia."

It’s an amazing story and a book I find myself picking up again and again. I found myself really liking Inés even when I was horrified at her brutality.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

This week La Bloga welcomes our guest contributor Lisa Alvarado who will be our Thursday columnist while compadrito Rudy is out tilting at windmills and slaying dragons.

The Housekeeper’s Diary, which dealt with her experiences as a domestic for one of Chicago’s wealthiest families, premiered nationally in Washington, D.C. in 2001, as a co-production with Sol y Soul and Gala Hispanic Theater. She has performed through out the U.S. and in Ajijic, Jalisco in Mexico. Lisa and her work have been featured in the Reader, The Chicago Tribune, Latino USA/National Public Radio, and Public Radio International. Her writing also received critical acclaim from such authors as Luis J. Rodriguez, who wrote..."...she is a fine poet, able to addresses deep concerns in crisp, trenchant language...The Housekeeper’s Diary...casts its spell on you...You will never see domestic work with the same eyes....”

Lisa has also completed an ambitious trilogy of performance pieces, REM/Memory, Bury The Bones and Resurgam, whose themes are the culture of violence, popular culture and personal redemption.

Her first novel, Sister Chicas (written with Ann Hagman Cardinal and Jane Alberdeston) has been bought by Penguin/NAL, and was released in April 2006. Sister Chicas is a coming of age story concerning the lives of three young Latinas living in Chicago.

This does look interesting, but I wonder how long the students will pick this one up after the memory of the event fades. (Says someone who cannot bear to get rid of her Mt. St. Helens books!)

Hopefully, this story will remain relevant and compelling(and, as someone who breathed in the dust of the Mt. St. Helens eruption, I know that story is compelling as well!) simply because it is a very human and uplifting story. Sadly, as I recall, there were no dramatic tales of survival after Mt. St. Helens.

Two years already! I love it when nonfiction youth tales are also the source of inspiration. These men did the world proud.

A very timely book. I am amazed at how quickly 'more recent' events (I noted that this event already happened two years back) can now be published in this format for students to discuss and mull over in school. If I look back during my younger years, this would have taken years and years and years to happen.