new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Stephen Crane, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Stephen Crane in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

When I wrote about The Scarlet Letter I mentioned that is was part of a project I began (and then ended) to reread a number of the books I read in high school and have not read since. Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane was the other book I read in the project. When I began reading it I was already wavering on the project and the book cemented my decision to not continue. I figure if I have not read a book since high school there was probably a good reason for that.

So, Red Badge of Courage. One of the few books I read in high school that I recall not liking at all. I hoped with time and maturity the reread would reveal the book to be amazing. Nope. While I can certainly appreciate it in a way I did not when I was 14, I still found it to be a very dull book.

First published in 1895, the book is a shining example of realism. Told from the limited third person perspective of Henry Fleming, a young man who joins up to fight in the American Civil War. His idea of what war is does not match the reality. Before he leaves, and even for a long time before he experiences battle he thinks,

It must be some sort of a play affair. He had long despaired of witnessing a Greek like struggle. Such would be no more, he had said. Men were better, or more timid.

When his regiment is finally sent out into the field they spend quite a lot of time walking and walking and walking, camping, walking some more as they are ordered to a new position, camping, waiting, waiting, waiting, only to have to move again. It is a tedious affair and the longer Henry has to wait for a battle the more he begins to worry that he will be a coward and turn and run. He becomes so obsessed by this worry that he starts asking his comrades probing questions in an attempt to find out what they think of the matter and succeeds only in annoying them.

When the battle finally comes, Henry does fine on the first assault but the enemy regroups and charges and breaks part of the line. Henry, seeing some of his comrades falling back in retreat, panics and turns tail and runs as fast and far away as he can.

He spends quite a long time wandering and berating himself for running while also trying to justify his actions. Eventually he falls in with wounded soldiers who are moving away from the lines because they can no longer fight. Among them is his friend Jim Conklin who was badly wounded, delirious, and eventually dies. During this time Henry is repeatedly asked where his wound is but avoids answering the question.

He does eventually get a wound but it doesn’t come from battle. He is whacked in the head with the butt of a riffle when he gets mixed up in a column of retreating soldiers. When he makes it back to his own regiment they all think he has been grazed in the head by a bullet and treat him kindly. Henry does not tell them the truth.

All this takes up a large portion of the book and I was beginning to think that perhaps this was an anti-war novel since the horrors are so brutally graphic and revelatory in just how much the lives of men like Henry are mere fodder.

But then the final part of the book is battle after battle and Henry, in an attempt to atone for his previous cowardice and desertion, fights valiantly and even becomes standard bearer when the previous one falls, leading his regiment to victory. During this time Henry acts almost entirely on fear, adrenaline and rage. He needs to prove himself and prove that he and his comrades are not useless and good for nothing like he overheard some officers saying they were.

And suddenly the book does not seem so anti-war any longer. It is blood and courage and glory. Henry survives the battle. His regiment regroups and gets new marching orders. As they march off, Henry thinks:

He had been to touch the great death, and found that, after all, it was but the great death. He was a man.

And it rains. And they trudge through mud. And the book ends:

Yet the youth smiled, for he saw that the world was a world for him, though many discovered it to be made of oaths and walking sticks. He had rid himself of the red sickness of battle. The sultry nightmare was in the past. He had been an animal blistered and sweating in the heat and pain of war. He turned now with a lover’s thirst to images of tranquil skies, fresh meadows, cool brooks–an existence of soft and eternal peace.

Over the river a golden ray of sun came through the hosts of leaden rain clouds.

What the heck are we supposed to make of that? Is Henry just as delusional now as he was before he went to join the army? Does he think the tranquility is going to be real? Or has he faced death and, knowing there are more battles ahead and he is likely to die, looking forward to a heavenly reward? I apparently am not the only one to wonder as the interwebs tell me scholars have been debating the ambiguous ending for a very long time. Well and so.

The thing I remember most from high school about this book was my teacher going on and on about Christ figures. I had misremembered it as being Henry and while reading I was so confused because I just could not see it. Turns out, the Christ figure is supposedly Henry’s friend Jim Conklin, the one he finds wounded and delirious. I am almost 100% certain that when I read that, I made the same face I did in high school when my teacher said as much.

The difference between then and now (ok there are a lot of differences, but don’t quibble with me on this) is that then there was only Cliff’s Notes and now there is the all-knowing Google. I don’t recall Cliff as being especially helpful in this case. Google, however, tells me this whole Christ figure thing is hotly disputed because no one seems to know what the book means and so a group of scholars decided it was an allegory even though the evidence for this is thin. I don’t remember if says Cliff anything about this or not, but since my entire class realized early on in the first semester that the teacher was cribbing almost everything from Cliff, I wouldn’t be surprised if it did.

It also goes a long way in explaining why I was so garsh durned baffled about this idea and how it set me up for repeated “Christ figure” traumas throughout my freshman, and most of my high school, English classes. When mixed with the basic narrative conflicts drilled into my head (man against nature, man against society, man against man, man against self) it made for a pretty murky five-paragraph essay soup. How I survived high school English and majored in English literature at University is a mystery I will never be able to solve. My only guess is that I loved reading and books so much before I got to high school that there was nothing they could do ruin it for me. And thank heavens for that!

Filed under:

Books,

Rereading,

Reviews Tagged:

Civil War,

Cliff's Notes,

Horrors of high school English,

Stephen Crane

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 5/2/2015

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Suzan-Lori Parks,

teaching,

Delany,

syllabi,

pedagogy,

Edgar Rice Burroughs,

canons,

Octavia Butler,

Stephen Crane,

Add a tag

This term, I taught an American literature survey for the first time since I was a high school teacher, and since the demands of a college curriculum and schedule are quite different from those of a high school curriculum and schedule, it was a very new course for me. Indeed, I've never even

taken such a course, as I was successful at avoiding all general surveys when I was an undergrad.

As someone who dislikes the

nationalism endemic to the academic discipline of literature, I had a difficult time figuring out exactly what sort of approach to take to this course — American Literature 1865-present — when it was assigned to me. I wanted the course to be useful for students as they work their way toward other courses, but I didn't want to promote and strengthen the assumptions that separate literatures by national borders and promote it through nationalistic ideologies.

I decided that the best approach I could take would be to highlight the forces of canonicity and nationalism, to put the question of "American literature" at the forefront of the course. This would help with another problem endemic to surveys: that there is far more material available than can be covered in 15 weeks. The question of what we should read would become the substance of the course.

The first choice I made was to assign the appropriate volumes of the

Norton Anthology of American Literature, not because it has the best selection, but because it is the most powerfully canonizing anthology for the discipline. Though the American canon of literature is not a list, the table of contents of the

Norton Anthology is about as close as we can get to having that canon as a definable, concrete object.

Then I wanted to add a work that was highly influential and well known but also not part of the general, academic canon of American literature — something for contrast. For that, I picked

A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs in the

Library of America edition, which has an excellent, thorough introduction by Junot Díaz. I also wanted the students to see how critical writings can bolster canonicity, and so I added

The Red Badge of Courage in

the Norton Critical Edition. Next, I wanted something that would puzzle the students more, something not yet canonized but perhaps with the possibility of one day being so, and for that I chose

Wild Seed by Octavia Butler (who is rapidly becoming an academic mainstay, particularly with her novel

Kindred). Finally, I thought the Norton anthology's selection of plays was terrible, so I added Suzan-Lori Parks's

Red Letter Plays, which are both in direct dialogue with the American literary canon and throwing a grenade at it.

The result was

this syllabus. As with any first time teaching a course, I threw a lot against the wall to see what might stick. Overall, it worked pretty well, though if I teach the course again, I will change quite a bit.

The students seemed to like the idea of canonicity and exploring it, perhaps because half of them are English Teaching majors who may one day be arbiters of the canon in their own classrooms. Thinking about why we read what we read, and how we form opinions about the respectability of certain texts over others, was something they seemed to enjoy, and something most hadn't had a lot of opportunity to do in a classroom setting before.

Starting the course with three articles we could return to throughout the term was one of the best choices I made, and the three all worked well: Katha Pollitt's “Why We Read: Canon to the Right of Me” from

The Nation and

Reasonable Creatures; George E. Haggerty's

“The Gay Canon” from

American Literary History; and Arthur Krystal's

“What We Lose If We Lose the Canon” from

The Chronicle of Higher Education. We had to spend some real time working through the ideas in these essays, but they were excellent touchstones in that they each offered quite a different view of the canon and canonicity.

I structured the course in basically two halves: the first half was mostly prescriptive on my part: read this, this, and this and talk about it in class. It was a way to build up a common vocabulary, a common set of references. But the second half of the course was much more open. The group project, in which students researched and proposed a unit for an anthology of American literature of their own, worked particularly well because it forced them to make choices in ways they haven't had to make choices before, and to see the difficulty of it all. (One group that said their anthology unit was going to emphasize "diversity" ended up with a short story section of white men plus Zora Neale Hurston. "How are you defining diversity for this section?" I asked. They were befuddled. It was a good moment because it highlighted for them how easy it is to perpetuate the status quo if you don't pay close attention and actively try to work against that status quo [assuming that working against the status quo is what you want to do. I certainly didn't require it. They could've said their anthology was designed to uphold white supremacy; instead, they said their goal was to be diverse, by which they meant they wanted to include works by women and people of color.])

Originally, there were quite a few days at the end of the term listed on the schedule as TBA. We lost some of these because we had three classes cancelled for snow in the first half of the term, and I had to push a few things back. But there was still a bit of room for some choice of what to read at the end, even if my grand vision of the students discovering things through the group project that they'd like to spend more time on in class didn't quite pan out. I should have actually built that into the group project: Choose one thing from your anthology unit to assign to the whole class for one of our TBA days. The schedule just didn't work out, though, and so I fell back on asking for suggestions, which inevitably led to people saying they were happy to read anything but poetry. (They

hate poetry, despite all my best efforts to show them how wonderful poetry can be. The poetry sections were uniformly the weakest parts of the proposed anthology units, and class discussions of even the most straightforward poems are painfully difficult. I love teaching poetry, so this makes me terribly sad. Next time I teach this course, I'm building even more poetry into it! Bwahahahahaaaa!) A couple of students are big fans of popular postmodernist writers (especially David Foster Wallace), so they wanted to make sure we read Pynchon's "Entropy" before the course ended, and we're doing that for our last day.

Though they haven't turned in their term papers, I've read their proposals, and it's interesting to see what captured their interest. Though we read around through a bunch of different things in the Norton anthology, at least half of the students are gravitating toward

Red Badge of Courage, Wild Seed, or

The Red Letter Plays. They have some great topics, but I was surprised to see that most didn't want to go farther afield, or to dig into one of the areas of the Norton that we hadn't spent much time on. Partly, this is probably the calculus of getting work done at the end of the term: go with what you are not only most interested in, but most confident you know what the person grading your paper thinks about the thing you're writing about. I suppose I could have required that their paper be about something we haven't read for class, but at the same time, I feel like we flew through everything and there's tons more to be discussed and investigated in any of the texts. They've come up with good topics and are doing good research on them all, so I'm really not going to complain.

In the future, I might be tempted to cut

Wild Seed, even though the students liked it a lot, and it's a book I enjoy teaching. It just didn't fit closely enough into our discussions of canonicity to be worth spending the amount of time we spent on it, and in a course like this, with such a broad span of material and such a short amount of time to fit it all in, the readings should be ruthlessly focused. It would have been better to do the sort of "canon bootcamp" that Crane and Burroughs allowed and then apply the ideas we learned through those discussions to a bunch of different materials in the Norton. We did that to some extent, but with the snow days we got really off kilter. I especially wish we'd had more time to discuss two movements in particular: the Harlem Renaissance and Modernism. Each got one day, and that wasn't nearly enough. My hope was that the groups would investigate those movements (and others) more fully for their anthology projects, but they didn't.

One of our final readings was Delany's

"Inside and Outside the Canon", which is dense and difficult for undergrads but well worth the time and effort. In fact, I'd be tempted to do it a week or so earlier if possible, because we needed time to apply some of its ideas more fully before students plunged into the term paper. I wonder, in fact, if it would be better as an ending to the first half of the course than the second... In any case, it's a keeper, but definitely needs time for discussion and working through.

If I teach the course again, I would certainly keep the Crane/Burroughs pairing. It worked beautifully, since the similarities and differences between the books, and between the writers of those books, were fruitful for discussion, and the Díaz intro to

Princess of Mars is a gold mine. We could have benefitted from one more day with each book, in fact, since there was so much to talk about: constructions of masculinity, race, heroism; literary style; "realism"...

I would be tempted to add a graphic narrative of some sort to the course. The Norton anthology includes a few pages from

Maus, but I would want a complete work. I'd need to think for a while about exactly what would be effective, but including comics of some sort would add another interesting twist to questions of canonicity and "literature".

Would I stick with the question of canonicity as a lens for a survey class in the future? Definitely. It's open enough to allow all sorts of ways of structuring the course, but it's focused enough to give some sense of coherence to a survey that could otherwise feel like a bunch of random texts strung together in chronological order for no apparent reason other than having been written by people somehow associated with the area of the planet currently called the United States of America.

Confession: There are a lot of us who die many small deaths during the act of promoting our books. We wish we didn't have to. We wish we were Michael Ondaatje or Alice McDermott or Colum McCann or any of the greats for whom the world both spins and waits, and not us, ourselves and ourselves only, who are easily forgotten, or never actually known.

Book promotion. It can involve embarrassing displays of self-involvement (for the next sixty minutes I will be doing all the talking, thank you very much), nasty tricks (remember the writer who recently shipped her dead husband's ashes around with the galleys?), indulgent wardrobing (you will remember me, you must remember me, won't you remember me?), and bold pronouncements about one's own talent (eeewww). We are asked to do many things. We do what we can. We close our eyes, we (maybe) grin and (barely) bear it, and then, mercifully, the promotion season has passed. We can be ourselves again.

We can buy and celebrate the books of others.

I'm not a touring writer. I'm not a famous one. This here blog, which is dedicated primarily to writerly musings and the works of others during the bulk of the year and to the news it seems right to share following the release of the small books I write (forgive me, I beg you, forgive me), is my home base, my foundation, my brand, my world, my virtual me. There is also, for the record, a flesh and blood me—a somewhat innocuous middle-aged woman who has little to say in real life and surprises people who meet her for the first time.

Just ask dear Debbie who could not, on Tuesday night, at Books of Wonder, get over how short I actually am.

(You might have thought I was tall? You might have thought I was glamorous? Ha! Wrong on both counts. Plus, I don't have a memorable wardrobe.)

I think about this promotion thing sometimes. Indeed, not long ago, musing out loud, I told my agent that I had begun to feel pressure not to speak of myself anymore on my blog. That, if only I had much more time than I do, I'd spend all the blog language on others.

"But it's your own blog," she said, "and you have responsibilities to your books."

"I know," I said. "But. Still. People are talking."

I'm talking about all of this right now because I just read Caleb Crain's piece on Stephen Crane in this week's

The New Yorker, "The Red and the Scarlet." It's a fine piece of biography and it doesn't need much of a preface; it stands, wildly, on its own.

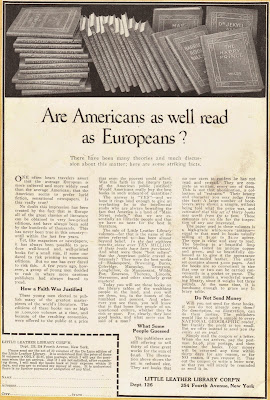

But here's the part I'd like to excerpt for you. It's the late 1800s. We're looking at self publishing and self-promotion. Seriously. Has anything changed?

Unable to find a publisher, Crane scraped together the money for "Maggie" to be printed. He chose yellow covers and the pseudonym Johnston Smith, and his friends threw him a raucous party....

To advertise the book, Crane hired four men to read it as conspicuously as possible on the elevated train, which, unfortunately, had little effect on sales. "It fell flat," he later admitted."

Self promotion. It's a terrifying term.

I'm going to be taking a small respite from the blog for the next few days, for I have several books I've bought and am planning to read. I need a little reading time and space. And then I'm going to report back here, as my short and unglamorous self. I hope you'll return when I do.

By: Alice,

on 2/26/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

classic,

joyce,

William Carlos Williams,

OWC,

modernism,

Tom Stoppard,

henry james,

Oxford World's Classics,

Gertrude Stein,

Robert Lowell,

ezra pound,

Ernest Hemingway,

first world war,

Joseph Conrad,

Humanities,

Jean Rhys,

Theodore Dreiser,

Benedict Cumberbatch,

*Featured,

Stephen Crane,

TV & Film,

Susanna White,

Arts & Leisure,

e. e. cummings,

Ford Madox Ford,

Good Soldier,

Max Saunders,

Parade’s End,

A Dual Life,

British novel,

Christopher Tietjens,

D. H. Lawrence,

Rebecca Hall,

Stella Bowen,

Valentine Wannop,

Wyndham Lewis,

Add a tag

By Max Saunders

One definition of a classic book is a work which inspires repeated metamorphoses. Romeo and Juliet, Gulliver’s Travels, Frankenstein, Dracula, The Great Gatsby don’t just wait in their original forms to be watched or read, but continually migrate from one medium to another: painting, opera, melodrama, dramatization, film, comic-strip. New technologies inspire further reincarnations. Sometimes it’s a matter of transferring a version from one medium to another — audio recordings to digital files, say. More often, different technologies and different markets encourage new realisations: Hitchcock’s Psycho re-shot in colour; French or German films remade for American audiences; widescreen or 3D remakes of classic movies or stories.

Cinema is notoriously hungry for adaptations of literary works. The adaptation that’s been preoccupying me lately is the BBC/HBO version of Parade’s End, the series of four novels about the Edwardian era and the First World War, written by Ford Madox Ford. Ford was British, but an unusually cosmopolitan and bohemian kind of Brit. His father was a German émigré, a musicologist who ended up as music critic for the London Times. His mother was an artist, the daughter of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown. Ford was educated trilingually, in French and German as well as English. When he was introduced to Joseph Conrad at the turn of the century, they decided to collaborate on a novel, and went on over a decade to produce three collaborative books. He also got to know Henry James and Stephen Crane at this time — the two Americans were also living nearby, on the Southeast coast of England. Americans were to prove increasingly important in Ford’s life. He moved to London in 1907, and soon set up the literary magazine that helped define pre-war modernism: the English Review. He had a gift for discovering new talent, and was soon publishing D. H. Lawrence and Wyndham Lewis alongside James and Conrad. But it was Ezra Pound, who he also met and published at this time, who was to become his most important literary friend after Conrad.

Cinema is notoriously hungry for adaptations of literary works. The adaptation that’s been preoccupying me lately is the BBC/HBO version of Parade’s End, the series of four novels about the Edwardian era and the First World War, written by Ford Madox Ford. Ford was British, but an unusually cosmopolitan and bohemian kind of Brit. His father was a German émigré, a musicologist who ended up as music critic for the London Times. His mother was an artist, the daughter of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown. Ford was educated trilingually, in French and German as well as English. When he was introduced to Joseph Conrad at the turn of the century, they decided to collaborate on a novel, and went on over a decade to produce three collaborative books. He also got to know Henry James and Stephen Crane at this time — the two Americans were also living nearby, on the Southeast coast of England. Americans were to prove increasingly important in Ford’s life. He moved to London in 1907, and soon set up the literary magazine that helped define pre-war modernism: the English Review. He had a gift for discovering new talent, and was soon publishing D. H. Lawrence and Wyndham Lewis alongside James and Conrad. But it was Ezra Pound, who he also met and published at this time, who was to become his most important literary friend after Conrad.

Ford served in the First World War, getting injured and suffering from shell shock in the Battle of the Somme. He moved to France after the war, where he soon joined forces with Pound again, to form another influential modernist magazine, the transatlantic review, which published Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Jean Rhys. Ford took on another young American, Ernest Hemingway, as his sub-editor. Ford held regular soirees, either in a working class dance-hall with a bar that he’d commandeered, or in the studio he lived in with his partner, the Australian painter Stella Bowen. He found himself at the centre of the (largely American) expatriate artist community in the Paris of the 20s. And it was there, and in Provence in the winters, and partly in New York, that he wrote the four novels of Parade’s End, that made him a celebrity in the US. He spent an increasing amount of time in the US through the 20s and 30s, based on Fifth Avenue in New York, becoming a writer in residence in the small liberal arts Olivet College in Michigan, spending time with writer-friends like Theodore Dreiser and William Carlos Williams, and among the younger generation, Robert Lowell and e. e. cummings.

Parade’s End (1924-28) has been dramatized for TV by Sir Tom Stoppard. It has to be one of the most challenging books to film; but Stoppard has the theatrical ingenuity, and experience, to bring it off. It’s a classic work of Modernism: with a non-linear time-scheme that can jump around in disconcerting ways; dense experimental writing that plays with styles and techniques. Though it includes some of the most brilliant conversations in the British novel, and its characters have a strong dramatic presence, much of it is inherently un-dramatic and, you might have thought, unfilmable: long interior monologues, descriptions of what characters see and feel; and — perhaps hardest of all to convey in drama — moments when they don’t say what they feel, or do what we might expect of them. Imagine T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’, populated by Chekhovian characters, but set on the Western Front.

I’ve worked on Ford for some years, yet still find him engaging, tantalising, often incomprehensibly rewarding, so I was watching Parade’s End with fascination. [Warning: Spoilers ahead.]

Click here to view the embedded video.

Stoppard and the director, Susanna White, have done an extraordinary job in transforming this rich and complex text into a dramatic line that is at once lucid and moving. Sometimes where Ford just mentions an event in passing, the adaptation dramatizes the scene for us. The protagonist is Christopher Tietjens, a man of high-Tory principle — a paradoxical mix of extreme formality and unconventional intelligence – is played outstandingly by Benedict Cumberbatch, with a rare gift to convey thought behind Tietjens’ taciturn exterior. In the novel’s backstory, Christopher has been seduced in a railway carriage by Sylvia, who thinks she’s pregnant by another man. The TV version adds a conversation as they meet in the train; then cuts rapidly to a sex scene. It’s more than just a hook for viewers unconcerned about textual fidelity, though. What it establishes is what Ford only hints at through the novel, and what would be missed without Tietjen’s brooding thoughts about Sylvia: that her outrageousness turns him on as much as it torments him. In another example, where the novelist can describe the gossip circulating like wildfire in this select upper-class social world, the dramatist needs to give it a location; so Stoppard invents a scene at an Eton cricket match for several of the characters to meet, and insult Valentine Wannop, while she and Tietjens are trying not to have the affair that everyone assumes they are already having. Valentine is an ardent suffragette. In the novel, she and Tietjens argue about women and politics and education. Stoppard introduces a real historical event from the period — a Suffragette slashing Velasquez’s ‘Rokeby Venus’ in the National Gallery — as a way of saying it visually; and then complicating it beautifully with another intensely visual interpolated moment. In the book Ford has Valentine unconcsciously rearranging the cushions on her sofa as she waits to see Tietjens the evening before he’s posted back to the war. When she becomes aware that she’s fiddling with the cushions because she’s anticipating a love-scene with him, the adaptation disconcertingly places Valentine nude on her sofa in the same position as the ‘Rokeby Venus’ — in a flash both sexualizing her politics and politicizing her sexuality.

Such changes cause a double-take in viewers who know the novels. But they’re never gratuitous, and always respond to something genuine in the writing.

Perhaps the most striking transformation comes during one of the most amazing moments in the second volume, No More Parades. Tietjens is back in France, stationed at a Base Camp in Rouen, struggling against the military bureaucracy to get drafts of troops ready to be sent to the Front Line. Sylvia, who can’t help loving Tietjens though he drives her mad, has somehow managed to get across the Channel and pursue him to his Regiment. She has been unfaithful, and he is determined not to sleep with her; but because his principles won’t let a man divorce a woman, he feels obliged to share her hotel room so as not to humiliate her publicly. She is determined to seduce him once more; but has been flirting with other officers in the hotel, two of whom also end up in their bedroom in a drunken brawl. It’s an extraordinary moment of frustration, hysteria, terror (there has been a bombardment that evening), confusion, and farce. In the book we sense Sylvia’s seductive power, and that Tietjens isn’t immune to it, even though by then in love with Valentine. He resists. But in the film version, they kiss passionately before being interrupted.

Valentine and Christopher. Adelaide Clemens and Benedict Cumberbatch in Parade’s End. (c) BBC/HBO.

The scene may have been changed to emphasize the power she still has over Tietjens: as if, paradoxically, he needs to be seen to succumb for a moment to make his resistance to her the more heroic. The change that’s going to exercise enthusiasts of the novels, though, is the way three of the five episodes were devoted to the first novel, Some Do Not…; and roughly one each to the second and third; with very little of the fourth volume, Last Post, being included at all. The third volume, A Man Could Stand Up — ends where the adaptation does, with Christopher and Valentine finally being united on Armistice night, a suitably dramatic and symbolic as well as romantic climax. Last Post is set in the 1920s and deals with post-war reconstruction. One can see why it would have been the hardest to film: much of it is interior monologue, and though Tietjens is often the subject of it he is absent for most of the book. Some crucial scenes from the action of the earlier books is only supplied as characters remember them in Last Post, such as when Syliva turns up after the Armistice night party lying to Christopher and Valentine that she has cancer in an attempt to frustrate their union. Stoppard incorporates this into the last episode, but he writes new dialogue for it to give it a kind of closure the novels studiedly resist. Valentine challenges her as a liar, and from Tietjens’ reaction, Sylvia appears to recognize the reality of his love for her and gives her their blessing.

Rebecca Hall, playing Sylvia, has been so brilliantly and scathingly sarcastic all the way through that this change of heart — moving though it is — might seem out of character: even the character the film gives her, which is arguably more sympathetic than the one most readers find in the novel. Yet her reversal is in Last Post. But what triggers it there, much later on, is when she confronts Valentine but finds her pregnant. Even the genius of Tom Stoppard couldn’t make that happen before Valentine and Christopher have been able to make love. But there are two other factors, which he was able to shift from the post-war time of Last Post into the war’s endgame of the last episode. One is that Sylvia has focused her plotting on a new object. Refusing the role of the abandoned wife of Tietjens, she has now set her sights on General Campion, and begun scheming to get him made Viceroy of India. The other is that she feels she has already dealt Tietjens a devastating blow, in getting the ‘Great Tree’ at his ancestral stately home of Groby cut down. In the book she does this after the war by encouraging the American who’s leasing it to get it felled. In the film she’s done it before the Armistice; she’s at Groby; Tietjens visits there; has a Stoppard scene with Sylvia arranged in her bed like a Pre-Raphaelite vision in a last attempt to re-seduce him, which fails partly because of his anger over the tree. In the books the Great Tree represents the Tietjens family, continuity, even history itself. Ford writes a sentence about how the villagers “would ask permission to hang rags and things from the boughs,” but Stoppard and White make that image of the tree, all decorated with trinkets and charms, a much more prominent motif, returning to it throughout the series, and turning it into a symbol of superstition and magic. But then Stoppard characteristically plays on the motif, and has Christopher take a couple of blocks of wood from the felled tree back to London. One he gives to his brother, in a wonderfully tangible and taciturn gesture of renouncing the whole estate and the history it stands for. The other he uses in his flat, throwing whisky over it in the fireplace to light a fire to keep himself and Valentine warm. That gesture shows how it isn’t just Sylvia who is saying ‘Goodbye to All That’, but all the major characters are anticipating the life that, though the series doesn’t show it, Ford presents in the beautifully elegiac Last Post.

Max Saunders is author of Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life (OUP, 1996/2012), and editor of Some Do Not . . ., the first volume of Ford’s Parade’s End (Manchester: Carcanet, 2010) and Ford’s The Good Soldier (Oxford: OUP, 2012). He was interviewed by Alan Yentob for the Culture Show’s ‘Who on Earth was Ford Madox Ford’ (BBC 2; 1 September 2012), and his blog on Ford’s life and work can be read on the OUPblog and New Statesman.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Portrait of Ford Madox Ford (Source: Wikimedia Commons); (2) Still from BBC2 adaption of Parade’s End. (Source: bbc.co.uk).

The post Ford Madox Ford and unfilmable Modernism appeared first on OUPblog.

I've cooled off after yesterday's tirade. I guess I'm just a little tired of all the flag waving. The image above is from a cover of The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane. One of the key scenes involves several standard bearers falling in battle until Henry, the protagonist, picks up the flag and leads his unit to victory. So much death just to keep a flag flying.

Sigh.

I'm a writer. Writers write. When stereotypes are tossed around (self-published writers are __________; literary agents are __________), no one wins. Writers write.

I've almost finished the extended "Spider and I". At around 16,000 words, I'm not sure what I'm going to do with it. Maybe I'll make it available in e-format for free. Maybe I'll do my own art and try to sell a limited number of hand-made chapbooks. Maybe I'll send it to a dozen markets and receive a dozen rejection letters. I don't know. Yet. But I wrote it because it was a story I wanted to tell.

I do know (from "Spider and I"):

Night was coming, and Jack was afraid.

I'm off the soapbox and in the trenches. Writers write. Period.

I recommend you market "Spider and I" and see what happens. Of course, I know only too well what an awkward length 16,000 words is. But if you can't find a market for it, there's always DIY. Good luck, either way.

Very best of luck with this - no matter what you decide to do... I know how difficult it is in this day and age to corner a market - especially when it's a betweeny length. But as you say it was something you really wanted to write and sometimes maybe that has to be enough??

You got that write, dude.

We do indeed write...because we love it, because it's part of who we are, no different to breathing or eating.

So perfectly true! I write because I have no more choice in doing it than I do sleeping. I can put it off but eventually I have to give in or suffer.

Love Spider.

By the way, I'm about halfway through The House Eaters and I'm lovin' it.