new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: French History, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 10 of 10

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: French History in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Eleanor Jackson,

on 3/3/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Religion,

Politics,

France,

pork,

Europe,

Gustave Flaubert,

French History,

secularism,

*Featured,

separation of church and state,

Arts & Humanities,

laïcité,

anticlericalism,

church and state,

Ernest Renan,

French Catholic,

front national,

Reading Writing and Religion in Nineteenth-Century France,

Robert D. Priest,

The Gospel According to Renan,

Add a tag

In France today, pork has become political. A series of conservative mayors have in recent months deliberately withdrawn the pork-free option from school lunch menus. Advocates of the policy claim to be the true defenders of laïcité, the French secular principle that demands neutrality towards religion in public space.

The post Secularism and sausages appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Michelle Mangione,

on 2/20/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

King Louis XVI,

Armand-Louis de Gontaut,

Claudine Guérin de Tencin,

David A. Bell,

François de Pâris,

French Revolutionary Figures,

Henri Grégoire,

History of French Revolution,

National Assembly of the French Revolution,

Reflections on France Past and Present,

Shadows of Revolution,

Books,

Europe,

European history,

French History,

*Featured,

Add a tag

While the French revolutionary era is a period of the past, it remains one of the most defining moments in the country’s legacy and history. The major victors and vices are well known in these moments of violence and change—but what about the forgotten? From radical cleric Henri Grégoire to military leader Armand-Louis de Gontaut, David A. Bell, author of Shadows of Revolution: Reflections on France, Past and Present, explores the overlooked figures of the French Revolution.

The post Four (mostly) forgotten figures from eighteenth-century France appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Priscilla Yu,

on 11/26/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Literature,

France,

BBC,

drama,

OWC,

Oxford World's Classics,

Impressionism,

french literature,

nineteenth century,

Timelines,

Emile Zola,

French History,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

rougon-macquart,

Arts & Humanities,

Glenda Jackson,

l'assommoir,

BBC Radio Four,

Dreyfus,

Add a tag

To celebrate the new BBC Radio Four adaptation of the French writer Émile Zola's, 'Rougon-Macquart' cycle, we have looked at the extraordinary life and work of one of the great nineteenth century novelists.

The post The life and work of Émile Zola appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Samantha Zimbler,

on 11/16/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

marie antoinette,

Europe,

French Revolution,

French politics,

French History,

*Featured,

Online products,

King Louis XVI,

OHO,

oxford handbooks online,

Arts & Humanities,

franco-Austrian relations,

Joseph II,

Oxford Handbook of the Ancien Regime,

Oxford Handbooks in History,

The Old Regime,

Thomas E. Kaiser,

Thomas Kaiser,

History,

Add a tag

Although most historians of the French Revolution assign the French queen Marie-Antoinette a minor role in bringing about that great event, a good case can be made for her importance if we look more deeply into her politics than most scholars have.

The post Marie-Antoinette and the French Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kim Behrens,

on 10/19/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

english literature,

French History,

*Featured,

Anne Curry,

UKpophistory,

Arts & Humanities,

English history,

1415,

Azincourt,

Hundred Year War,

Books,

Literature,

shakespeare,

Henry V,

Dr Who,

Europe,

Agincourt,

Bernard Cornwell,

Add a tag

In the six hundred year since it was fought the battle of Agincourt has become an exceptionally famous one, which has generated a huge and enduring cultural legacy. Everybody thinks they know what the battle was about but is the Agincourt of popular image the real Agincourt, or is our idea of the battle simply taken from Shakespeare's famous depiction of it?

The post “The Created Agincourt in Literature” extract from Agincourt appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alex Beaumont,

on 9/23/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Journals,

Politics,

France,

Europe,

French politics,

French History,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

Arts & Humanities,

french democracy,

malcolm crook,

protest voting,

second republic,

spoilt ballots,

Add a tag

You might not guess, but the image below celebrating the Second Republic of 1848 was cast at Dijon as a negative vote in the referendum of 1851, which sought approval for the coup d’état that brought Louis-Napoleon (nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte) to power in France. The overwhelming majority voted positively but, among a minority of dissenters, there were those who chose to graphically illustrate their opposition. Others made adverse written comments on their papers and still more defaced the ballot they had been instructed to use by the newly installed Napoleonic authorities, or submitted blank pieces of paper to the ballot box.

The post Subversive voting, or how the French spoil their ballot papers appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Amelia Carruthers,

on 7/26/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

France,

facts,

marie antoinette,

Europe,

Revolution,

French Revolution,

guillotine,

French History,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Bastille,

Robespierre,

Arts & Humanities,

listicle,

Brissot,

Choosing Terror,

facts about french revolution,

Girondins,

historical facts,

Jacobins,

Let them eat cake,

Marisa Linton,

Thermidor,

Books,

History,

myths,

Add a tag

The French Revolution was one of the most momentous events in world history yet, over 220 years since it took place, many myths abound. Some of the most important and troubling of these myths relate to how a revolution that began with idealistic and humanitarian goals resorted to ‘the Terror’.

The post Ten myths about the French Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 8/4/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

peace,

war,

Europe,

French Revolution,

European history,

Napoleon,

French History,

*Featured,

munro,

tuileries,

UKpophistory,

King Louis XVI,

Munro Price,

Napoleon the end of glory,

schwarzenberg,

schwarzenberg’s,

napoleon’s,

delaroche,

Add a tag

By Munro Price

On 9 April 1813, only four months after his disastrous retreat from Moscow, Napoleon received the Austrian ambassador, Prince Schwarzenberg, at the Tuileries palace in Paris. It was a critical juncture. In the snows of Russia, Napoleon had just lost the greatest army he had ever assembled – of his invasion force of 600,000, at most 120,000 had returned. Now Austria, France’s main ally, was offering to broker a deal – a compromise peace – between Napoleon and his triumphant enemies Russia and England. Schwarzenberg’s visit to the Tuileries was to start the negotiations.

Schwarzenberg’s description of the meeting is one of the most revealing insights into Napoleon’s character from any source. In place of the imperious conqueror of only ten months before, Schwarzenberg now saw a man who feared ‘being stripped of the prestige he [had] previously enjoyed; his expression seemed to ask me if I still thought he was the same man.’

To Schwarzenberg’s dismay, when it came to peace Napoleon still showed his old obstinacy and unwillingness to make concessions. The reason for this, however, was unexpected. It concerned not diplomacy or the military situation, but Napoleon’s domestic position in France. He told Schwarzenberg:

“If I made a dishonourable peace I would be lost; an old-established government, where the links between ruler and people have been forged over centuries can, if circumstances demand, accept a harsh peace. I am a new man, I need to be more careful of public opinion … If I signed a peace of this sort, it is true that at first one would hear only cries of joy, but within a short time the government would be bitterly attacked, I would lose … the confidence of my people, because the Frenchman has a vivid imagination, he is tough, and loves glory and exaltation.”

Napoleon’s reluctance to make peace at this key moment has been generally ascribed to his gambling instinct, a refusal to accept that Destiny might desert him, and a desperate belief he could still defeat his enemies in battle even now. The idea that fear might also have played a part seems so alien to Napoleon’s character that it has rarely been considered.

Napoleon was convinced, as his words to Schwarzenberg made clear, that the best way of anchoring any new régime was through military glory. Nowhere was this truer, he felt than in France, which had just undergone a revolution of unprecedented scale and violence. He genuinely feared that a sudden loss of international prestige could reopen the divisions he had spent fifteen years trying to close.

This fear may well have originated in a particular early experience. On 10 August 1792, as a young officer, Napoleon had witnessed one of the climactic moments of the French Revolution, the storming of the Tuileries by the Paris crowd and the overthrow of King Louis XVI. It was the first fighting he had ever seen. He had been horrified by the subsequent massacre of the Swiss Guards and the accompanying atrocities. For Napoleon, this trauma also held a political lesson. Louis XVI had been dethroned because he had failed to show sufficient enthusiasm for a revolutionary war, and because his people had come to susepct his patriotism. Napoleon’s words to Schwarzenberg two decades later show his determination not to make the same mistake.

Significantly, when the prospect of a compromised peace appeared close during 1813 and 1814, Napoleon always used this same argument to counter it: his own rule over France would not survive an inglorious peace. He did this most dramatically on 7 February 1814. With France already invaded, his enemies offered to let him keep his throne if he renounced all of France’s conquests since the Revolution. His closest advisers urged him to accept, but he burst out: “What! You want me to sign such a treaty … What will the French people think of me if I sign their humiliation? … You fear the war continuing, but I fear much more pressing dangers, to which you’re blind.” That night, he wrote an apocalyptic letter to his brother Joseph, making it clear that he preferred his own death, and even that of his son and heir, to such a prospect.

Napoleon himself obviously believed that peace without victory would seriously threaten his dynasty. Was he right? My own view, based on researching the state of French public opinion at the time, is that he was not. The overwhelming majority of reports show the French people in 1814 as exhausted by endless war and its burdens. They were desperate for peace. Ironically, it was not concessions for the sake of peace, but his determination to go on fighting, that eventually undermined Napoleon’s domestic support. By refusing to recognize this, Napoleon did indeed cause his own downfall.

Munro Price is a historian of modern French and European history, with a special focus on the French Revolution, and is Professor of Modern European History at Bradford University. His publications include The Fall of the French Monarchy: Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and the baron de Breteuil, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions, and The Road to Apocalypse: the Extraordinary Journey of Lewis Way (2011). Napoleon: The End of Glory publishes this month.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Did Napoleon cause his own downfall? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 7/21/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

WWII,

World War II,

Europe,

Second World War,

Jean Marais,

French History,

*Featured,

Alfred Rosenberg,

Pierre Laval,

David Ball,

Diary of the Dark Years,

Jean Guehenno,

Alain Cuny,

Francois Darlan,

Jean Racine,

Occupation of Paris,

laval,

Add a tag

By David Ball

In the Epilogue to his penetrating, well-documented study, Nazi Paris, Allan Mitchell writes “Parisians had endured the trying, humiliating, and essentially absurd experience of a German Occupation.” Odd as it may sound, “absurd” is exactly right. Both the word and the sense of absurdity come up again and again in the diary kept by a remarkable French intellectual during those “dark years,” as he called them. For the absurd is not only laughable: it can be dangerous. Here is a sampling of the absurdities Jean Guéhenno noted in his Diary of the Dark Years 1940-1944.

24 October 1940

French politician Pierre Laval (1883-1945) as lawyer in 1913. Agence de presse Meurisse Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Yesterday evening all the newspapers were shouting out the great news: “M. Pierre Laval has met with the Führer.” . . . For what price did he sell us down the river? As early as 9 PM, the English radio was announcing the conditions of the deal: but what can we really know about it? Did the Marshal reject them? Are we going to be forced to put all our hopes on the resistance of that old man? This tyranny is too absurd, and its absurdity is too obvious to too many people for it to last.

For we have been plunged into vileness, that much is certain, but still more into absurdity.

29 November 1940

The newspapers are lamentably empty. This morning, however, I find the speech that Alfred Rosenberg, the high priest of Nazism, delivered yesterday from the podium of our Chamber of Deputies. For it is from there that Nazism is to hold sway over France . . . The history of the 19th century, he claims, is nothing but the struggle of blood against gold. “But today, blood is victorious at last . . . which means the racist, creative strength of central Europe.” I am recopying it exactly . . . Race? Claiming to rebuild Europe on a fable like that — how absurd!

7 January 1941

. . . my deepest reason for hope: it’s just that all this is too absurd. Something as absurd as this cannot possibly last. It seems to me I can read their embarrassment on the faces of the occupying forces. Every day, they are increasingly obliged to feel like foreigners. They don’t know what to do in the streets of Paris or whom to look at. They are sad and exiled. The jailor has become the prisoner. If he were sincere and he could speak, he would apologize for being here. No doubt that pitiable revolver he carries at his side reduces us to silence. And so? For how long will he be carrying it — will he have to carry it? For, without a revolver . . . Will he be condemned to wear it forever and live in this exile, without any other justification, any other joy than that little revolver?

10 February 1941

Every evening at the Opera, I am told, German officers are extremely numerous. At the intermissions, following the custom of their country, they walk around the lobby in ranks of three or four, all in the same direction. Despite themselves, the French join the procession and march in step, unconsciously. The boots impose their rhythm.

11 March 1941

M. Darlan is proclaiming “Germany’s generosity.” It is the height of absurdity: these vanquished generals have become our masters, and because of their very defeat, they must fear England’s victory and the restoration of France above all.

17 September 1941

I went on a trip to Brittany for a change of air and to try to get supplies of food, for life here has become increasingly wretched . . . Everywhere I found the same absurdity . . . On the sea, on the moors, in the forest, . . . just when I was going to forget about him, suddenly the gray soldier was there in front of me, with his rifle and his face of an all-powerful, barbaric moron. But it is impossible that he himself cannot feel how vain is the terror he is wielding. The sailors of Camaret make fun of him openly . . . He will go away as he came; he will have gone on a long, absurd trip.

Paris Opera Palais Garnier by Smtunli, Svein-Magne Tunli. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

22 February 1943

. . . those officers one meets around the Madeleine and the Opera in their fine linen greatcoats, with their vain, high caps, that look of proud stupidity on their faces and those nickel-plated daggers joggling around their bottoms. Then there are [the] busy little females — those mailwomen or telephone operators who look like Walkyries: one can sense their vanity and emptiness. The other day on the Place de la Concorde in front of the Ministry of the Navy I stopped to watch the sentries — those unchanging puppets who have stood there on each side of the door for more than two years, without drinking, eating or sleeping, like the symbol of deadly, mechanical [German] order right in the middle of Paris. I stood looking at them for a while as they pivoted like marionettes. But one tires of the Nuremberg clock . . .

29 May 1944

A torrent of stupidity. Two movie actors had put on Racine’s Andromaque in the Édouard VII Theater. Their interpretation of the play seemed immoral. Andromaque has been banned. This morning, the newspapers are publishing the following note: “The French Militia is concerned about the intellectual protection of France as well as public morality. That is why the regional head of the for the Militia of the Paris region notified the Prefect of Police that it was going to oppose the production of the scandalous play by Messieurs Jean Marais and Alain Cuny now playing at the Édouard VII Theater. The Prefect of Police issued a decree immediately banning the play.

David Ball is Professor Emeritus of French and Comparative Literature, Smith College. He is the editor and translator of Diary of the Dark Years, 1940-1944: Collaboration, Resistance, and Daily Life in Occupied Paris.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post “How absurd!” The Occupation of Paris 1940-1944 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 3/22/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

tapestry,

magna carta,

bates,

david bates,

the normans and empire,

tournai marble,

civilising,

History,

France,

British,

normandy,

bayeux,

normans,

empire,

British history,

French History,

*Featured,

the normans,

Add a tag

By David Bates

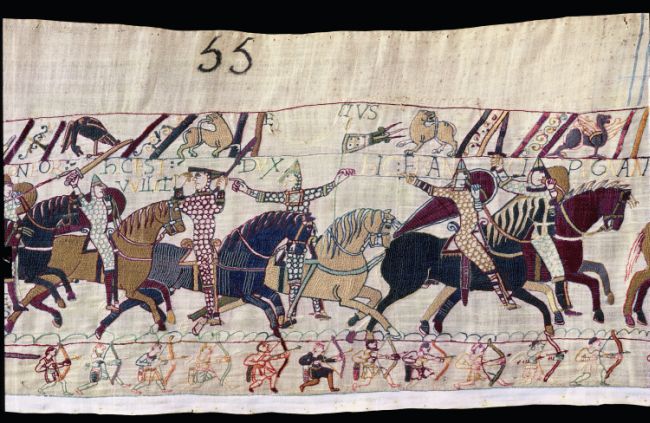

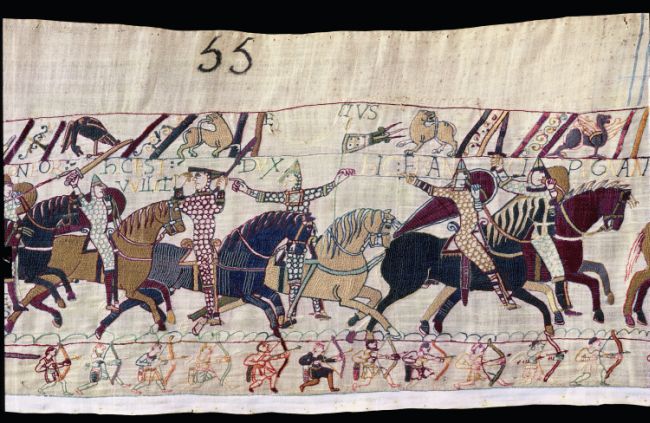

The expansion of the peoples calling themselves the Normans throughout northern and southern Europe and the Middle East has long been one of the most popular and written about topics in medieval history. Hence, although devoted mainly to the history of the cross-Channel empire created by William the Conqueror’s conquest of the English kingdom in 1066 and the so-called loss of Normandy in 1204, I wanted to contribute to these discussions and to the ongoing debates about the impact of this expansion on the histories of the nations and cultures of Europe. That peoples from a region of northern France should become conquerors is one of the apparently inexplicable paradoxes of the subject. The other one is how the conquering Normans apparently faded away, absorbed into the societies they had conquered or within the kingdom of France.

In 1916 Charles Homer Haskins’ made the statement that the Normans represented one of the great civilising influences in European – and indeed world – history. If, a century later, hardly anyone would see it thus, the same imperatives remain, namely to locate the Normans within a context in which it remains popular to write national histories, and, for some, in the midst of debates about the balance of the History curriculum, to see them as being of paramount importance. The history of the Normans cuts across all this, but is an inescapable subject in relation to the histories of the English, French, Irish, Italian, Scottish, and Welsh. Those currently fashionable concepts – and rightly so – ‘The First English Empire’ and ‘European change’ are also at the centre of the debates.

As a concept, empire is nowadays both fashionable and much argued about, a universal phenomenon of human history that has been the subject of several major television programmes. It is a subject that requires a multidisciplinary approach. Over the last two millennia, statements by both contemporaries and subsequent commentators have often set a proclaimed imperial civilising mission as a positive feature against the impact of violence and the social and cultural subjugation of the subjects of an empire. Seen thus, the concept of empire has an obvious relevance to the subject of the Normans. And, in relation to the pan-European expansion of the Normans, and, in particular, to the creation of the kingdom of Sicily, the term diaspora, as it is understood in the social sciences, constitutes a persuasive framework of analysis. Taken together, the two terms empire and diaspora create a world in which individuals and communities had to adapt rapidly to new forms of power and cultures and in which identities are multiple, flexible, and often uncertain. For this reason, the telling of life-histories is of central importance rather than simplified notions of social and cultural identity. One consequence must be the abandonment of the currently popular and unhelpful word Normanitas. The core of this book is a history of power, diversity and multiculturalism in the midst of the complexities of a changing Europe.

The use of terms such as hard power, soft power, hegemony, core and periphery, and cultural transfer can be used to frame interpretations of many national histories, including Welsh, Scottish, and Irish, as well as English. The crucial points in all cases are the mixture of engagement with the dominant imperial power and the perpetuation of difference and diversity through the exercise of agency beyond the core. The framework is one that works especially well in relation to the evolving histories of the Welsh kingdoms/principalities and of the kingdom of Scots. It also means that the so-called ‘anarchy’ of 1135 to 1154, the succession dispute between King Stephen and the Empress Matilda becomes a civil war which needs to be set in a cross-Channel context and through which there were many continuities. And Magna Carta (1215), of which the eight-hundredth anniversary is fast approaching, becomes a consequence of imperial collapse. However, a focus on England and the British Isles just does not work. Normandy’s centrality to the history of the cross-Channel empire created in 1066 is of basic importance. Both morally and militarily the creation of the cross-Channel empire brought problems of a new kind that were for some living, or mainly domiciled, in Normandy a source of anguish. The book’s cover has indeed been chosen with this in mind. It shows troubled individuals who have narrowly escaped disaster at sea, courtesy of St Nicholas. But they successfully made the crossing. And so, of course, did the Tournai marble on which they are carved.

Professor David Bates took his PhD at the University of Exeter, and over a professional career of more than forty years, he has held posts in the Universities of Cardiff, Glasgow, London (where he was Director of the Institute of Historical Research from 2003 to 2008), East Anglia, and Caen Basse-Normandie. He has worked extensively in the archives and libraries of Normandy and northern France and has always sought to emphasise the European dimension to the history of the Normans. ‘He currently holds a Leverhulme Trust Emeritus Fellowship to enable him to complete a new biography of William the Conqueror in the Yale University Press English Monarchs series. His latest book is The Normans and Empire.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Section of the Bayeaux Tapestry, courtesy of the Conservateur of the Bayeux Tapestry. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post The Normans and empire appeared first on OUPblog.

What could philosophy have to do with odors and perfumes? And what could odors and perfumes have to do with Art? After all, many philosophers have considered smell the lowest and most animal of the senses and have viewed perfume as a trivial luxury.

The post Perfumes, olfactory art, and philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

Novelists are used to their characters getting away from them. Tolstoy once complained that Katyusha Maslova was “dictating” her actions to him as he wrestled with the plot of his last novel, Resurrection. There was a story that after reading Mikhail Sholokhov’s And Quiet Flows the Don, Stalin praised the work but advised the author to “convince” the main character, Melekhov, to stop loafing about and start serving in the Red Army.

The post An educated fury: faith and doubt appeared first on OUPblog.

The very look and feel of families today is undergoing profound changes. Are public policies keeping up with the shifting definitions of “family”? Moreover, as the population ages within these new family dynamics, how will families give or receive elder care? Below, we highlight just a few social changes that are affecting the experiences of aging families.

The post When aging policies can’t keep up with aging families appeared first on OUPblog.