By David Ball

In the Epilogue to his penetrating, well-documented study, Nazi Paris, Allan Mitchell writes “Parisians had endured the trying, humiliating, and essentially absurd experience of a German Occupation.” Odd as it may sound, “absurd” is exactly right. Both the word and the sense of absurdity come up again and again in the diary kept by a remarkable French intellectual during those “dark years,” as he called them. For the absurd is not only laughable: it can be dangerous. Here is a sampling of the absurdities Jean Guéhenno noted in his Diary of the Dark Years 1940-1944.

24 October 1940

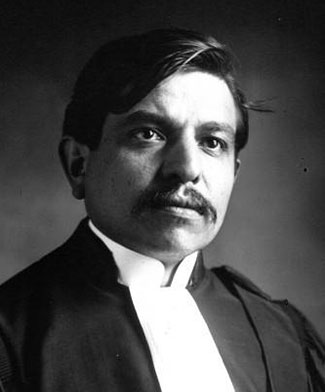

French politician Pierre Laval (1883-1945) as lawyer in 1913. Agence de presse Meurisse Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Yesterday evening all the newspapers were shouting out the great news: “M. Pierre Laval has met with the Führer.” . . . For what price did he sell us down the river? As early as 9 PM, the English radio was announcing the conditions of the deal: but what can we really know about it? Did the Marshal reject them? Are we going to be forced to put all our hopes on the resistance of that old man? This tyranny is too absurd, and its absurdity is too obvious to too many people for it to last.

For we have been plunged into vileness, that much is certain, but still more into absurdity.

29 November 1940

The newspapers are lamentably empty. This morning, however, I find the speech that Alfred Rosenberg, the high priest of Nazism, delivered yesterday from the podium of our Chamber of Deputies. For it is from there that Nazism is to hold sway over France . . . The history of the 19th century, he claims, is nothing but the struggle of blood against gold. “But today, blood is victorious at last . . . which means the racist, creative strength of central Europe.” I am recopying it exactly . . . Race? Claiming to rebuild Europe on a fable like that — how absurd!

7 January 1941

. . . my deepest reason for hope: it’s just that all this is too absurd. Something as absurd as this cannot possibly last. It seems to me I can read their embarrassment on the faces of the occupying forces. Every day, they are increasingly obliged to feel like foreigners. They don’t know what to do in the streets of Paris or whom to look at. They are sad and exiled. The jailor has become the prisoner. If he were sincere and he could speak, he would apologize for being here. No doubt that pitiable revolver he carries at his side reduces us to silence. And so? For how long will he be carrying it — will he have to carry it? For, without a revolver . . . Will he be condemned to wear it forever and live in this exile, without any other justification, any other joy than that little revolver?

10 February 1941

Every evening at the Opera, I am told, German officers are extremely numerous. At the intermissions, following the custom of their country, they walk around the lobby in ranks of three or four, all in the same direction. Despite themselves, the French join the procession and march in step, unconsciously. The boots impose their rhythm.

11 March 1941

M. Darlan is proclaiming “Germany’s generosity.” It is the height of absurdity: these vanquished generals have become our masters, and because of their very defeat, they must fear England’s victory and the restoration of France above all.

17 September 1941

I went on a trip to Brittany for a change of air and to try to get supplies of food, for life here has become increasingly wretched . . . Everywhere I found the same absurdity . . . On the sea, on the moors, in the forest, . . . just when I was going to forget about him, suddenly the gray soldier was there in front of me, with his rifle and his face of an all-powerful, barbaric moron. But it is impossible that he himself cannot feel how vain is the terror he is wielding. The sailors of Camaret make fun of him openly . . . He will go away as he came; he will have gone on a long, absurd trip.

Paris Opera Palais Garnier by Smtunli, Svein-Magne Tunli. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

22 February 1943

. . . those officers one meets around the Madeleine and the Opera in their fine linen greatcoats, with their vain, high caps, that look of proud stupidity on their faces and those nickel-plated daggers joggling around their bottoms. Then there are [the] busy little females — those mailwomen or telephone operators who look like Walkyries: one can sense their vanity and emptiness. The other day on the Place de la Concorde in front of the Ministry of the Navy I stopped to watch the sentries — those unchanging puppets who have stood there on each side of the door for more than two years, without drinking, eating or sleeping, like the symbol of deadly, mechanical [German] order right in the middle of Paris. I stood looking at them for a while as they pivoted like marionettes. But one tires of the Nuremberg clock . . .

29 May 1944

A torrent of stupidity. Two movie actors had put on Racine’s Andromaque in the Édouard VII Theater. Their interpretation of the play seemed immoral. Andromaque has been banned. This morning, the newspapers are publishing the following note: “The French Militia is concerned about the intellectual protection of France as well as public morality. That is why the regional head of the for the Militia of the Paris region notified the Prefect of Police that it was going to oppose the production of the scandalous play by Messieurs Jean Marais and Alain Cuny now playing at the Édouard VII Theater. The Prefect of Police issued a decree immediately banning the play.

David Ball is Professor Emeritus of French and Comparative Literature, Smith College. He is the editor and translator of Diary of the Dark Years, 1940-1944: Collaboration, Resistance, and Daily Life in Occupied Paris.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post “How absurd!” The Occupation of Paris 1940-1944 appeared first on OUPblog.