new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: french literature, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 17 of 17

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: french literature in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Priscilla Yu,

on 11/26/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Literature,

France,

BBC,

drama,

OWC,

Oxford World's Classics,

Impressionism,

french literature,

nineteenth century,

Timelines,

Emile Zola,

French History,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

rougon-macquart,

Arts & Humanities,

Glenda Jackson,

l'assommoir,

BBC Radio Four,

Dreyfus,

Add a tag

To celebrate the new BBC Radio Four adaptation of the French writer Émile Zola's, 'Rougon-Macquart' cycle, we have looked at the extraordinary life and work of one of the great nineteenth century novelists.

The post The life and work of Émile Zola appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Connie Ngo,

on 7/6/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Literature,

Videos,

adaptation,

film adaptations,

Oxford World's Classics,

Gustave Flaubert,

french literature,

nineteenth century,

Madame Bovary,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

flaubert,

book vs movie,

Bovary,

Emma Bovary,

Emma Rouault,

Add a tag

The tragic story of Madame Bovary has been told and retold in a number of adaptations since the text's original publication in 1856 in serial form. But what differences from the text should we expect in the film adaptation? Will there be any astounding plot points left out or added to the mix?

The post Capturing the essence of Madame Bovary appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 7/14/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

reading list,

VSI,

very short introduction,

Europe,

French Revolution,

Bastille Day,

french literature,

UPSO,

*Featured,

John Phillips,

bastille,

university press scholarship online,

Online products,

william doyle,

and the French Revolution,

Bryant T. Ragan,

Dan Edelstein,

Homosexuality in Modern France,

Jeremy Jennings,

Jeremy Merrick,

John D. Lyons,

Keith Reader,

Le quatorze juillet,

Modern France,

Revolution and the Republic: A History of Political Thought in France since the Eighteenth Century,

the Cult of Nature,

The Marquis de Sade,

The Place de la Bastille: The Story of a Quartier,

The Terror of Natural Right: Republicanism,

Vanessa R. Schwartz,

History,

Add a tag

Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.

– Jean-Jacques Rousseau

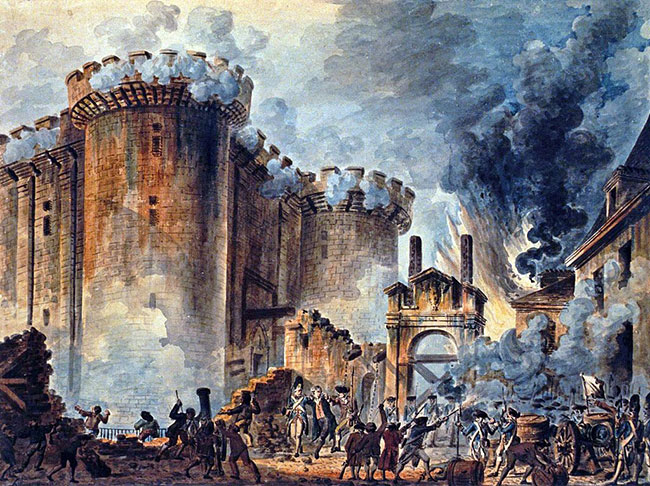

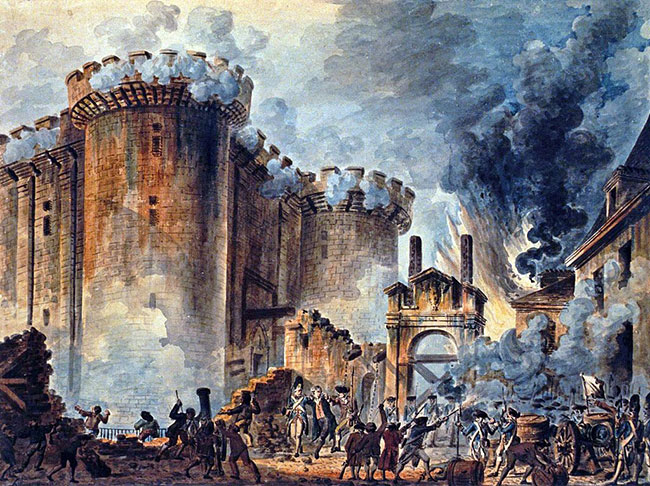

The Bastille once stood in the heart of Paris — a hulking, heavily-fortified medieval fortress, which was used as a state prison. During the 18th century, it played a key role in enforcing the government censorship, and had become increasingly unpopular, symbolizing the oppressiveness and the costly inefficiency of the reigning monarchy and the ruling classes.

On 14 July 1789, the prison of Bastille was stormed by revolutionaries. It housed, at the time, only seven prisoners — including two “lunatics” and one “deviant” aristocrat — but the storming of the fortress was not just a tactical victory. Its fall at the hands of the Parisian militia and the city’s peasants was a symbolic and ideological victory for the revolutionary cause, and became the flashpoint for one of the most tumultuous periods of European history. With the fall of the Bastille, the French Revolution had begun, which would eventually culminate in the bloody toppling of a regime which had existed for nearly 800 years. This day is celebrated across France as Le quatorze juillet, the first milestone along the road to the French Republic. In English-speaking countries, it is called Bastille Day.

To mark Bastille Day, and the 225th anniversary of the French Revolution, we’ve made a selection of informative scholarly articles free to read on the Very Short Introductions online resource and University Press Scholarship Online. Want to find out about the French Revolution, how it began, what happened, and why it is perhaps one of the most pivotal events in modern European history? Then carry on reading.

The Storming of the Bastille by Jean-Pierre Houël (1735-1813). Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Why did the French Revolution happen?

“Why it happened” in The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction by William Doyle

The years of build up to the French Revolution were full of uncertainty and confusion. Why the Revolution happened was not because of a single event, but instead it was caused by a number of developments at the end of the 1780s. This chapter provides a brief overview of these events, taking a look at how important the financial problems were in causing the initial unrest and the significance of the role of the monarchy.

What happened at the Storming of the Bastille?

“‘Thought blew the Bastille apart’: The Fall of the Fortress and the Revolutionary Years, 1789-1815“ in The Place de la Bastille: The Story of a Quartier by Keith Reader

During the late 1780s, France was suffering under a crippling economic crisis, throwing the lavish expenditures of the ruling classes and the economic incompetence of the state into bass relief. The Bastille, incredibly costly to maintain and a symbol of state oppression, had become increasingly unpopular with the masses for this reason, among others. This chapter focuses on the events which culminated in the storming and eventual ruin of the fortress, and the ensuing revolutionary years.

How has the Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen been used throughout French history?

“Rights, Liberty, and Equality“ in Revolution and the Republic: A History of Political Thought in France since the Eighteenth Century by Jeremy Jennings

The Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen (The Deceleration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen) was passed in August 1789 by France’s National Constituent Assembly. It was a cornerstone of the Revolution, and set out the rights of man as “liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression,” and is one of the most important documents in the history of human rights. Exploring the content of the Déclaration, this chapter goes on to examine how the language of rights it set out was used in key, formative moments in subsequent French history.

What were the Marquis de Sade’s politics during the French Revolution?

“Sade and the French Revolution” in The Marquis de Sade: A Very Short Introduction by John Phillips

Donatien Alphonse François de Sade, or the Marquis de Sade, was a French aristocrat, politician, and writer accused by many of political opportunism during the Revolution. He portrayed himself as both a feudal lord and the “liberator” of Bastille, when he called for revolution from his cell. He was a theatrical man with many opportunities to self-dramatize during the Revolution, making it difficult to clearly understand his political position. This chapter examines this through his thoughts and writings during the Revolution.

How was Marie-Antoinette represented?

“Pass as a Woman, Act like a Man: Marie-Antoinette as Tribade in the Pornography of the French Revolution“ in Homosexuality in Modern France ed. by Jeremy Merrick and Bryant T. Ragan

Marie-Antoinette, the ill-fated Austrian princess who married Louis XVI, and who met her fate under the guillotine in 1793 at the present-day Place de la Concorde, has long been a much-maligned figure of the Revolution — her name now synonymous with large wigs, “let them eat cake,” and cold indifference to the plight of the poor and disenfranchised. In this chapter, the pornographic pamphlets distributed about the Queen during the Revolution are analysed, paying particular attention to her supposed homosexuality and licentiousness, and the role this took in the anti-monarchist propaganda of the period.

What literature was inspired by the Revolution?

“Around the Revolution” in French Literature: A Very Short Introduction by John D. Lyons

Throughout the 1700s many in France grew more and more sceptical: about the absolute nature of the monarchy and around the idea that authority was established by divine providence. This chapter looks at how the literature of the time was inspired by and reflected this dissatisfaction, including Pierre Caron de Beaumarchais’s The Marriage of Figaro and The Marquis de Sade’s Justine ou les Malheurs de la Vertu.

What was the Terror?

“Off with their Heads: Death and the Terror“ in The Terror of Natural Right: Republicanism, the Cult of Nature, and the French Revolution by Dan Edelstein

The guillotine has come to embody the darker side of the French Revolution, especially during the Reign of Terror which lasted from September 1793 to July 1794. The death toll of The Terror is almost incomprehensible, with 16,500 victims meeting their ends under the guillotine. Maximilien Robespierre is the figure most closely associated with this bloody period, and yet, “in one of the more bitter ironies of history” as this chapter says, he started his career as an outspoken opponent of the death penalty. Here, the genesis of The Terror is detailed, the differences between the French and American Revolutions set out, and the concept of the hostis humani generis (enemy of humanity) introduced — an enemy who could only be met with death.

How did the French Revolution change France?

“The French Revolution, politics, and the modern nation” in Modern France: A Very Short Introduction by Vanessa R. Schwartz

The French Revolution, unlike others, managed to effect change from within, with the new government making some radical changes, even starting a new calendar, to differentiate themselves from the old regime. This chapter looks at how history and symbols were used by this new government to symbolize and mythologize their nation.

University Press Scholarship Online (UPSO) brings together the best scholarly publishing from around the world. Aggregating monograph content from leading university presses, UPSO offers an unparalleled research tool, making disparately published scholarship easily accessible, highly discoverable, and fully cross-searchable via a single online platform. Research that previously would have required a user to jump between a variety of books and disconnected websites can now be concentrated through the UPSO search engine.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A reading list on the French Revolution for Bastille Day appeared first on OUPblog.

When you have read of the secret sorrows of old Goriot you will dine with unimpaired appetite, blaming the author for your callousness, taxing him with exaggeration, accusing him of having given wings to his imagination. But you may be certain that this drama is neither fiction nor romance. All is true, so true that everyone can recognize the elements of the tragedy in his own household, in his own heart perhaps.

So Balzac lets us know what to expect within the first couple pages of Old Goriot (or Pere Goriot depending on the translation). But while Goriot is the pivot around which the story revolves, the story itself belongs to Eugène de Rastignac, student of law, poor, ambitious. He has come to Paris from the country to study and make something of himself. His family scrimps and saves and goes without in order to send him as much money as they can. Rastignac takes up residence in the shabby but genteel boardinghouse of Madame Vauquer. Everyone at the boardinghouse makes fun of old Goriot, a quiet gentle man who keeps to himself. They see him occasionally with a well-dressed woman and assume he has spent all his money on mistresses. Rastignac, however, discovers the truth.

Eager to make a name for himself, Rastignac takes advantage of a family connection, his cousin the Viscountess Madame de Beauséant. Rastignac is like a cute puppy peeing on the carpet because he is so very excited and wants only to please. The Viscountess takes a liking to him and agrees to introduce him into society and teach him a thing or two.

It turns out that Goriot’s mistresses are actually his two beloved daughters. He has given then all his money and lives in increasing poverty as he gradually sells off all his remaining valuables in order to help them out of debts and buy their love. For he loves them very much and has deluded himself into believing they love him just as much in return. Rastignac falls in love with one of the daughters, Delphine, who, like her sister, is in a loveless marriage to a husband who has used her fortune badly.

This being Paris high society, everyone has affairs and as long as appearances are kept up that all is proper between husband and wife, nobody really cares. Rastignac and Delphine with full knowledge and encouragement from Goriot, launch themselves into a romance.

But poor Rastignac, he has two angels sitting on his shoulders. Goriot is the good angel and Vautrin the bad. Vautrin is a rich and ruthless dandy who ingratiates himself with everyone. All the residents at the boardinghouse love him. He offers to be like a father to Rastignac, lending him all the money he needs and teaching him everything he needs to know about how to be a success and become rich. Vautrin with his “basilisk glance” offers so many temptations to Rastignac that he finds himself on the brink of giving in and sacrificing any conscience he might have remaining to him.

But Goriot saves Rastignac by dying. Goriot’s death reveals to Rastignac the true nature of Delphine and her sister, their selfishness, insincerity and lack of conscience and duty. He had thought high society was just a game but now he understands just how depraved it all is. His response is to declare war, though what that means exactly, we are left to wonder, at least at the end of Old Goriot.

I have never read Balzac before so this was an interesting experience. He sticks hard to the realism, no flights of fancy, no romance, no dreamy moments. He shines a very bright light into all the dark corners revealing the dirt and the flaws, no one and nothing is spared, not even Goriot, the most sympathetic of all the characters. Balzac is given to making narrative intrusions and providing opinions. But at the same time he can turn out a marvelous description like this one of the lodgers at the boardinghouse:

Although their cold, hard faces were worn, like those on coins withdrawn from circulation, their withered mouths were armed with avid teeth.

The book is not a fast read nor is it especially compelling. However, it is a well-written, well-told story that is worth the effort. I read the book along with Danielle which was nice because we kept each other going. Be sure to hop over to her blog and read her thoughts on the book.

Filed under:

Books,

French Literature,

Reviews Tagged:

Balzac

By: Kirsty,

on 4/16/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Humanities,

french literature,

Emile Zola,

*Featured,

zola,

rougon-macquart,

saccard,

bourse,

sigismond,

Literature,

money,

paris,

translation,

Finance,

OWC,

banking,

Oxford World's Classics,

Add a tag

By Valerie Minogue

Money is a tricky subject for a novel, as Zola in 1890 acknowledged: “It’s difficult to write a novel about money. It’s cold, icy, lacking in interest…” But his Rougon-Macquart novels, the “natural and social history” of a family in the Second Empire, were meant to cover every significant aspect of the age, from railways and coal-mines to the first department stores. Money and the Stock Exchange (the Paris Bourse) had to have a place in that picture, hence Money, the eighteenth of Zola’s twenty-novel cycle.

The subject is indeed challenging, but it makes an action-packed novel, with a huge cast, led by a smaller group of well-defined and contrasting characters, who inhabit a great variety of settings, from the busy, crowded streets of Paris to the inside of the Bourse, to a palatial bank, modest domestic interiors, houses of opulent splendour — and a horrific slum of filthy hovels that makes a telling comment on the social inequalities of the day.

Dominating the scene from the beginning is the central, brooding figure of Saccard. Born Aristide Rougon, Saccard already appears in earlier novels of the Rougon-Macquart, notably in The Kill, which relates how Saccard, profiting from the opportunities provided by Haussman’s reconstruction of Paris, made – and lost – a huge fortune in property deals. Money relates Saccard’s second rise and fall, but Saccard here is a more complex and riveting figure than in The Kill.

Émile Zola painted by Edouard Manet

It is Saccard who drives all the action, carrying us through the widely divergent social strata of a time that Zola termed “an era of folly and shame”, and into all levels of the financial world. We meet gamblers and jobbers, bankers, stockbrokers and their clerks; we get into the floor of the Bourse, where prices are shouted and exchanged at break-neck speed, deals are made and unmade, and investors suddenly enriched or impoverished. This is a world of insider-trading, of manipulation of share-prices and political chicanery, with directors lining their pockets with fat bonuses and walking off wealthy when the bank goes to the wall — scandals, alas, so familiar that it is hard to believe this book was written back in 1890! Saccard, with his enormous talent for inspiring confidence and manipulating people, would feel quite at home among the financial operators of today.

Saccard is surrounded by other vivid characters – the rapacious Busch, the sinister La Méchain, waiting vulture-like for disaster and profit, in what is, for the most part, a morally ugly world. Apart from the Jordan couple, and Hamelin and his sister Madame Caroline, precious few are on the side of the angels. But there are contrasts not only between, but also within, the characters. Nothing and no-one here is purely wicked, nor purely good. The terrible Busch is a devoted and loving carer of his brother Sigismond. Hamelin, whose wide-ranging schemes Saccard embraces and finances, combines brilliance as an engineer with a childlike piety. Madame Caroline, for all her robust good sense, falls in love with Saccard, seduced by his dynamic vitality and energy, and goes on loving him even when in his recklessness he has lost her esteem. Saccard himself, with all his lusts and vanity and greed, works devotedly for a charitable Foundation, delighting in the power to do good.

Money itself has many faces: it’s a living thing, glittering and tinkling with “the music of gold”, it’s a pernicious germ that ruins everything it touches, and it’s a magic wand, an instrument of progress, which, combined with science, will transform the world, opening new highways by rail and sea, and making deserts bloom. Money may be corrupting but is also productive, and Saccard, similarly – “is he a hero? is he a villain?” asks Madame Caroline; he does enormous damage, but also achieves much of real value.

Fundamental questions about money are posed in the encounter between Saccard and the philosopher Sigismond, a disciple of Karl Marx, whose Das Kapital had recently appeared — an encounter in which individualistic capitalism meets Marxist collectivism head to head. Both men are idealists in very different ways, Sigismond wanting to ban money altogether to reach a new world of equality and happiness for all, a world in which all will engage in manual labour (shades of the Cultural Revolution!), and be rewarded not with evil money but work-vouchers. Saccard, seeing money as the instrument of progress, recoils in horror. For him, without money, there is nothing.

If Zola vividly presents the corrupting power of money, he also shows its expansive force as an active agent of both creation and destruction, like an organic part of the stuff of life. And it is “life, just as it is” with so much bad and so much good in it, that the whole novel finally reaffirms.

Valerie Minogue has taught at the universities of Cardiff, Queen Mary University of London, and Swansea. She is co-founder of the journal Romance Studies and has been President of the Émile Zola Society, London, since 2005. She is the translator of the new Oxford World’s Classics edition of Money by Émile Zola.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Émile Zola by Edouard Manet [public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Money matters appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 3/13/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

christopher betts,

jean de la fontaine,

selected fables,

the fisherman and the little fish,

the lion and the fly,

the wolf in shepherd's clothing,

betts,

smock,

fontaine,

Literature,

aesop's fables,

Humanities,

*Featured,

wolf,

fables,

sheep,

bagpipes,

french literature,

Add a tag

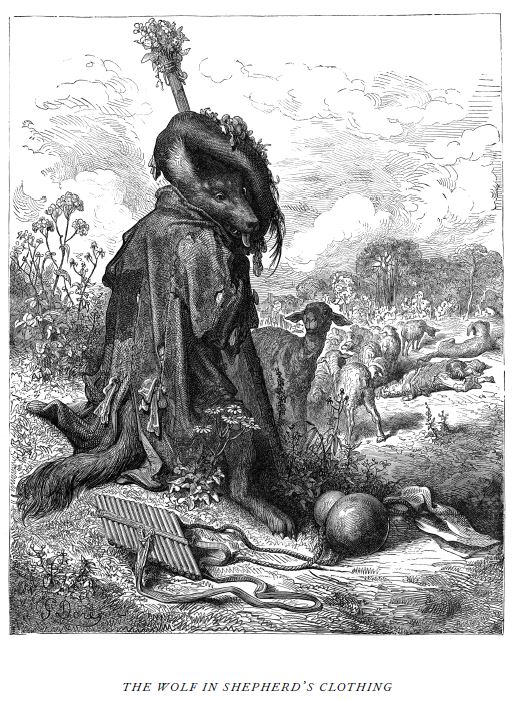

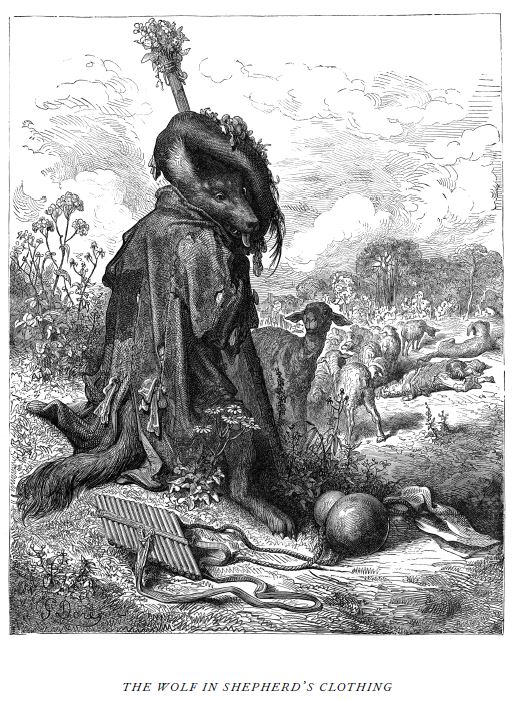

Jean de La Fontaine’s verse fables turned traditional folktales into some of the greatest, and best-loved, poetic works in the French language. His versions of stories such as ‘The Wolf in Shepherd’s Clothing’ and ‘The Lion and the Fly’ are witty and sophisticated, satirizing human nature in miniature dramas in which the outcome is unpredictable. The behaviour of both animals and humans is usually centred on deception and cooperation (or the lack of it), as they cheat and fight each other, arguing about life and death, in an astonishing variety of narrative styles. To get a flavour of the fables, here are two taken from Selected Fables by Jean de La Fontaine, translated by Christopher Betts.

The Wolf in Shepherd’s Clothing

A wolf had hunted sheep from local fields,

but found the hunt was giving lower yields.

He thought to take a leaf from Reynard’s book:

disguise himself by changing what he wore.

He donned a smock, and took a stick for crook;

the shepherd’s bagpipes too he bore.

The better to accomplish his design,

he would have wished, had he been able,

to place upon his hat this label:

‘My name is Billy and these sheep are mine.’

His alterations now complete,

he held the stick with two front feet;

then pseudo-Billy gently stepped

towards the flock, and while he crept,

upon the grass the real Billy slept.

His dog as well was sound asleep,

his bagpipes too, and almost all the sheep.

The fraudster let them slumber where they lay.

By altering his voice to suit his dress,

he meant to lure the sheep away

and take them to his stronghold in the wood,

which seemed to him essential to success.

It didn’t do him any good.

He couldn’t imitate the shepherd’s speech;

the forest echoed with his wolfish screech.

His secret was at once undone:

his howling woke them, every one,

the lad, his dog, and all his flock.

The wolf was in a sorry plight:

amidst the uproar, hampered by his smock,

he could not run away, nor could he fight.

Some detail always catches rascals out.

He who is a wolf in fact

like a wolf is bound to act:

of that there ’s not the slightest doubt.

The Fisherman and the Little Fish

A little fish will bigger grow

if Heaven lets it live; but even so

to set one free, and wait until it’s fat,

then try again: I see no sense in that;

I doubt that it will let itself be caught.

An angler at the river’s edge one day

had hooked a carp. ‘A tiddler still,’ he thought,

but then reflected, looking at his prey:

‘Well, every little helps to make a meal,

perhaps a banquet; in the creel

is where you’ll go, to start my store.’

As best it could, the fish replied:

‘What kind of meal d’you think that I’ll provide?

I’d make you half a mouthful, not much more.

I’ll grow much bigger if you throw me back;

then catch me later on; I’d fill a sack.

A full-grown carp’s a fish that you can sell;

some greedy businessman will pay you well.

But now, you’d need a hundred fish

the size that I am now, to fill a single dish.

Besides, what sort of dish? Hardly a feast.’

‘No feast? quite so,’ replied the man;

‘it’s something, though, at least.

You prate as well as parsons can,

my little friend; but though you talk a lot

this evening it’s the frying-pan for you.’

A bird in the hand, as they say, is worth two

in the bush; the first one is certain, the others are not.

Jean de La Fontaine (1621-95) followed a career as a poet after early training for the law and the Church. He came under the wing of Louis XIV’s Finance Minister, Nicolas Fouquet, and later enjoyed the patronage of the Duchess of Orléans and Mme de La Sablière. His Fables were widely admired, and he was already regarded in his lifetime as one of the greatest poets of his age. Christopher Betts was Senior Lecturer in the French Department at Warwick University. In 2009 he published an acclaimed translation of Perrault’s The Complete Fairy Tales with OUP.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Both images are from Gustave Doré’s engravings, which are included in the edition, and are in the public domain.

The post Selected fables about wolves and fishermen appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 2/17/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

OWCs,

french theatre,

maya slater,

moliere,

tartuffle,

the misanthrope,

the school for wives,

molière’s,

molière,

molière…,

mignard,

Literature,

drama,

OWC,

Oxford World's Classics,

Humanities,

french literature,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Theatre & Dance,

Arts & Leisure,

Add a tag

By Maya Slater

The farce is at its height: the old clown in the armchair is surrounded by whirling figures in outlandish doctors’ costumes, welcoming him into their brotherhood with a mock initiation ceremony. He takes the Latin oath: ‘Juro’, falters. His face crumples. The audience gasps – is something wrong? But the clown is grinning now, all is well, the dancing grows frenzied, the play rushes on to its end.

Not till the next day will the audience find out what happened afterwards. They carried the clown off the stage in his chair, and rushed him home. He was coughing blood, dying. He asked for his wife, and for a priest to confess him. They failed to arrive before he died.

It happened 340 years ago, on 17 February 1673, but his magnificently ironic death is still central to the French understanding of Molière. He is their greatest comic playwright, unique in that he also directed his own plays and wrote his greatest parts for himself. Centuries later, this still gives the modern audience a frisson. In The Hypochondriac, sick with TB (he had his fatal seizure during the fourth performance), Molière himself spoke the following words:

‘Your Molière’s an impertinent fellow… If I were a doctor, I’d have my revenge… when he fell ill, I’d let him die without helping him. I’d say: “Go on, drop dead!”

Writing those words anticipating his own death was surely tempting fate, but long before his last play, audiences had got used to seeing Molière on stage speaking lines which seemed to cast an ironic light on his own life. Nine years earlier, in The School for Wives (1662), the first of his great verse comedies, he played the part of a ridiculous old bachelor determined to marry an innocent young girl decades younger than him. Instead, the girl escapes with a young man her own age. The audience knew that Molière himself had recently married Armande – he was 40, she was 22. What must they have thought when he portrayed a thwarted older lover, gnashing his teeth in rage and frustration as his young bride escaped from his clutches?

Writing those words anticipating his own death was surely tempting fate, but long before his last play, audiences had got used to seeing Molière on stage speaking lines which seemed to cast an ironic light on his own life. Nine years earlier, in The School for Wives (1662), the first of his great verse comedies, he played the part of a ridiculous old bachelor determined to marry an innocent young girl decades younger than him. Instead, the girl escapes with a young man her own age. The audience knew that Molière himself had recently married Armande – he was 40, she was 22. What must they have thought when he portrayed a thwarted older lover, gnashing his teeth in rage and frustration as his young bride escaped from his clutches?

A year later, Molière’s self-mockery has grown more explicit. The new play is The School for Wives Criticised, a short, informal sketch, ridiculing Molière’s critics in an argument about The School for Wives. Significantly, Molière didn’t defend his own play onstage. Instead, he himself played an absurd Marquis, who attacks Molière and his work: ‘I’ve just been to see it… It’s detestable.’ ‘Talk to us about its faults,’ says someone. ‘How should I know? I didn’t even bother to listen,’ replies the Marquis.

Molière’s second riposte to his critics, which again took the form of a short polemic play, The Impromptu at Versailles, was strikingly new, and still feels fresh and exciting today. We see Molière (who just this once played himself) and his troupe in rehearsal, trying desperately to get a performance together for the King and Court to see. The actors are uncooperative and annoying, which enables Molière to show himself trying to cope with them. He presents himself as unable to keep control of his unruly cast, breaking out in frustration: ‘Don’t you realise, I’m the one who carries the can…?’ When they finally start their rehearsal, Molière interrupts it to comment on The School for Wives, and to make some interesting general observations on acting. The play they are rehearsing is a conversation between two stupid courtiers. Molière again takes the part of the silly Marquis, and once more launches a comic attack on himself: ‘You’re desperate to justify Molière… don’t you think your Molière is played out [?]’ And then comes a moment unique in his work, where he takes over another actor’s part, and speaks as himself, in defence of his own art: ‘Wait a minute, You want to say all that a bit more emphatically. Listen, this is how I want it spoken…’

Of course the burning question must be: what was Molière like as an actor, and how did he perform his roles? We know he wore a heavy black moustache. We can assume that he excelled at portraying comic rage and frustration, from the number of furious outbursts he wrote for himself to perform. He put himself in ridiculous situations, hiding under the table in Tartuffe, performing a clumsy dance in The Bourgeois Gentleman, fleeing in terror dressed as a woman in M. de Pourceaugnac. But perhaps the most vivid account of his acting is found in a malicious satirical portrait written by the son of a rival actor:

‘He enters, nose to the wind, on bow legs, one shoulder thrust forward. His wig trails behind, stuffed full of bayleaves like a ham. He dangles his hands rather carelessly by his sides. His head sits on his back like a pack on a mule. He rolls his eyes. When he speaks his lines, the words are punctuated by endless hiccoughs.’

By the end, racked with TB, his performances had become less physically demanding. And performing the role which killed him that February night 350 years ago, that of the ludicrous hypochondriac, he was having to insert lines to excuse his own coughing, and played the part sitting in the red velvet chair which is still preserved as their most precious relic by the Comédie française theatre.

Maya Slater is Senior Reseach Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. She also writes fiction and reviews theatre and books. She is the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Misanthrope, Tartuffe, and Other Plays by Molière.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Molière as Julius Cesar by Nicolas Mignard [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post The tragic death of an actor appeared first on OUPblog.

The latest addition to our Reviews Section is a piece by Katie Assef on Jean-Philippe Toussaint’s The Truth about Marie, translated from the French by Matthew B. Smith and available from Dalkey Archive Press.

Katie Assef is another of Susan Bernofsky’s students who very kindly offered to write reviews for Three Percent. Here’s the opening of her review:

In The Truth about Marie, Belgian writer Jean-Philippe Toussaint takes us on a journey from Paris to Tokyo, with a sensuous detour to the island of Elba. It’s a book that begins with a thunderstorm and ends in massive forest fires, a love story examined through the lens of a tumultuous breakup. When the novel opens, Marie is spending a night with her new lover, Jean-Christophe, in the apartment she and the unnamed narrator formerly shared. At the same moment, in his apartment a few blocks away, the narrator is making love to a woman about whom we learn only that she, too, is named Marie. A drama will unfold this evening, bringing the ex-lovers back together, if only long enough to move a dresser out of a bedroom.

Readers familiar with Toussaint’s œuvre will recognize these characters: though the book is not exactly a sequel, it is narratively linked to the 2005 novel Fuir (published in the U.S. in 2009 as Running Away, also translated by Matthew B. Smith). The earlier book focuses on the disintegration of the couple’s relationship during a trip to Japan, and The Truth about Marie begins months after their breakup proper. Toussaint beautifully renders that period—for some of us, indefinite—when a relationship has ended, but we continue to live in its atmosphere. The “truth” he describes has little to do with Marie herself; rather, it speaks to the idea that the only stability in love is instability. “I loved her, yes,” the narrator tells us, “It may be very imprecise to say I loved her, but nothing could be more precise.”

Click here to read the entire review.

By: Chad W. Post,

on 4/2/2012

Blog:

Schiel & Denver Book Publishers Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

douglas & mcintyre,

quebecois literature,

btba 2012,

25 days of the btba,

dany laferrière,

haitian literature,

i am a japanese writer,

matt jakubowski,

french literature,

Add a tag

As with years past, we’re going to spend the next week highlighting the rest of the 25 titles on the BTBA fiction longlist. We’ll have a variety of guests writing these posts, all of which are centered around the question of “Why This Book Should Win.” Hopefully these are funny, accidental, entertaining, and informative posts that prompt you to read at least a few of these excellent works.

Click here for all past and future posts in this series.

I Am a Japanese Writer by Dany LaFerrière, translated by David Homel

Language: French

Country: Haiti/Canada

Publisher: Douglas & McIntyre

Why This Book Should Win: On one level this is a calmly experimental and defiant novel that dismisses the label “world literature” as a cheap marketing ploy. It’s also a loving reminiscence of formative readings experiences that continue to haunt and fuel the writer’s life.

Today’s post is by Matthew Jakubowski, a writer and literary journalist who’s written for Bookforum, The Cleveland Plain Dealer, The Quarterly Conversation, Barrelhouse, and BOMB. He lives in West Philadelphia.

Laferrière fled to Montreal from Haiti during the Duvalier regime after some of his fellow journalists were killed. Throughout his career, he’s refused to let race or nationality define him or his work and I Am a Japanese Writer, blends fiction and autobiography as its writer-narrator, also a black writer from Haiti living in Montreal, causes a small international incident after he tells his publisher his new novel, which he has yet to start writing, will be called I Am a Japanese Writer.

I made a case for this potent little novel in my positive review for The National, a book which Laferrière dedicates to “everyone who would like to be someone else.” This phrase is meant somewhat literally, in that it’s directed at book lovers, implying that in Laferrière’s view we read with the silent hope or expectation that at some point we forget our own life and have the chance to feel like someone else.

One of the best aspects of this book is the comforting rhythm and ease with which Laferrière assembles an increasingly madcap plot and various digressions about his writing career, switching perspectives and tone so easily and assuredly that after the first few short chapters it doesn’t matter what aspects are true or completely invented.

The result is a funny yet sharp and experimental novel that meanders with purpose, intercut with memories from the narrator’s early life in Haiti, and riffs on the influence of Basho, Borges, and Baudrillard.

The plot’s fairly simple: pressed for time, the writer throws out a crazy book title to his publisher, who loves it and cuts the writer a check, who leaves the office laughing. Complications follow as the writer tries to research the book, and things get out of hand when a Japanese consul tries to intervene.

But the writer’s joke on his publisher turns out not to be a joke, because he says, “I really do consider myself a Japanese writer.” But how can a Haitian writer living in Montreal claim to be Japanese? Eventually, Laferrière gives one form of answer: “Years later, when I became a writer and people asked me, ‘Are you a Haitian writer, a Caribbean writer,

The latest addition to our Reviews Section is a piece by Vincent Francone on Jacques Dupin’s Of Flies and Monkeys, which is translated from the French by John Taylor and available from Bitter Oleander Press. (Probably easiest to order this directly from SPD.)

“Vincent Francone” is one of our regular contributors. (In fact, he has a “25 Days of the BTBA” piece coming out on Friday.) Additionally, he’s a writer and a reader for TriQuarterly Online.

Here’s the opening of his piece:

My head hasn’t been in poetry lately. Call it burn out—last year I read mostly poems—or attribute it to grad school killing my love for poetry, but I have been reading more prose as of late. Subsequently, my recent poetry reading has mostly been out of obligation.

That being said, it takes a lot to get me excited about poetry. Jacques Dupin’s work is, thankfully, the kind of poetry that does intrigue, delight, and reward, making it the ideal poetry to reignite my old love. The recent release of three of his works, collected under the title Of Flies and Monkeys, makes the case for Dupin’s importance in the world of contemporary poetry. Dupin is an interesting figure. A contemporary of Yves Bonnefoy and follower of Francis Ponge, his name is not bandied about with the regularity of his peers. Add to that, his poems ride the crest between the legacy of surrealism and the state sanctioned aesthetic of political rumination. Neither of these trends suited Dupin, whose work is at once immediate and startling (“a clearing sodomoy / her saintly hem fucked / under the same low leaves”) even when the images veer into the obscure (“As if I were the moist imprint of her voice. The oil and the gathering of her endless worm-screws in the air”). Dupin’s images are both strong and subtle, suggesting a modern-day Artuad who pulls back just before his poems become clouded by the grotesque. This is a writer who understands his craft, and while he refuses to adhere to trends his work has the balance and grace of a trained master.

Click here to read the entire review.

As with years past, we’re going to spend the next three weeks highlighting the rest of the 25 titles on the BTBA fiction longlist. We’ll have a variety of guests writing these posts, all of which are centered around the question of “Why This Book Should Win.” Hopefully these are funny, accidental, entertaining, and informative posts that prompt you to read at least a few of these excellent works.

Click here for all past and future posts in this series.

Demolishing Nisard by Eric Chevillard, translated by Jordan Stump

Language: French

Country: France

Publisher: Dalkey Archive Press

Why this book should win: The pleasure-to-page-count ratio. Because Dalkey Archive is overdue. Because if this book doesn’t win, it’s a victory for Nisard.

Today’s piece is by Eric Lundgren, a graduate of the Writing Program at Washington University in St. Louis and the author of the chapbook The Bystanders (All Along Press).

Demolishing Nisard asks us to believe that a literary critic poses a grave threat to our world. It’s a rich premise. Who is Désiré Nisard? A notorious bore, pedant, and careerist, author of a fusty four-volume history of French literature, sporting muttonchop whiskers and an Academie Française robe. Oh yeah, and he has been dead for over a century. An unlikely enemy to say the least, but Eric Chevillard’s seductive narrator will quickly convert you to his cause.

I want to call this book something other than a novel. Chevillard uses the term “broadside,” which just about does justice to its sustained antagonism. There’s a plot of sorts (the narrator’s hunt for Nisard’s suppressed and saucy-sounding fiction A Milkmaid Succumbs) but Chevillard isn’t all that invested in conventional storytelling. This book is anchored in voice and style. It doesn’t so much develop as intensify, gathering complication and depth along the way. Fans of books that relentlessly pursue their subjects, like U and I or The Loser, will feel right at home here.

Instead of the careful embroidery of well-made fiction, Demolishing Nisard offers rough edges of trash talk raised to an art. It’s tempting to quote whole reams of Jordan Stump’s translation. Do I choose the part where the narrator laments Nisard’s facial hair, because it doesn’t cover enough of his face? The catalog of suggested assaults, which includes “spray herbicide on his golf course”? The beautiful passage in praise of birds, because they carry feathers (i.e. pen quills) away from Nisard? Chevillard is a master stylist and he writes coiled, serpentine sentences that unfold at just the right heat and pace. In English lit you have to reach back to Pope or Swift to find invective of this quality:

He is the slime at the bottom of every fountain. Irretrievably, there has been Nisard. How can we love benches, knowing that Nisard often pressed them into service? Gently stroking a cat’s silken fur, my hand inevitably reproduces a gesture once made by Nisard . . . Did Nisard ever make one move that we might want to follow or imitate? Did he ever incarnate anything other than the tedium of being Désiré Nisard, definitively, forever and ever?

Like the allergens and vermin to which he’s often compared, Nisard invades the book. His name appears in a series of contemporary newspaper columns quoted by the narrator. In these columns, Nisard morphs into a drunk drive

As with years past, we’re going to spend the next three weeks highlighting the rest of the 25 titles on the BTBA fiction longlist. We’ll have a variety of guests writing these posts, all of which are centered around the question of “Why This Book Should Win.” Hopefully these are funny, accidental, entertaining, and informative posts that prompt you to read at least a few of these excellent works.

Click here for all past and future posts in this series.

Upstaged by Jacques Jouet, translated by Leland de la Durantaye (which sounds like an Oulipian pseduonym)

Language: French

Country: France

Publisher: Dalkey Archive Press

Why This Book Should Win: Oulipians have the most fun.

Today’s post is written by John Smieska, MPAS PA-C, whom I met when working at Schuler Books & Music approximately 29 years ago.

When you read any text produced by a member of the Oulipo group, there is an invitation to read with an awareness of the construction, an alertness in the background of the experience. Oulipo is an exclusive challenge-society, a think-tank that seeks to generate narrative constraints; these constraints spur the private literary ambitions of its members, and subvert the aesthetic traditions of narrative and language. Some works of this group are front-loaded, with the constraint or device announced in tandem with the debut of the text—this allows the act of reading to be textured with an editorial or fact-checker’s spectatorship. In other works, like Upstaged, the constraint is not made explicit, which allows the act of reading to be infused with a cryptographic undercurrent, a puzzler’s inquiry.

Upstaged by Jacques Jouet, to my best reckoning, is about a theatre and its doubles. (Indeed, there is some vulnerability in publicly proposing a solution to any puzzle that may or may not be absolutely correct.) The narrative folds around pairs; it splits and replicates like a feral blastomere, or like a work of dialectic origami. The narrator is the director’s assistant (herself, the self described factotum/factota of the playwright/director) during a routine performance of a play that becomes unsuspectingly vitalized when an unknown performer, known as “the Usurper,” invades the zona pellucida of a principle actor’s dressing room, and in the tender moments before his entrance, binds him naked to a chair and proceeds to hijack his role. (This all occurs in the national theatre of a Republic that is a double of the real—as much as politics are fictions used to organize, compel, and interpret events.) The play is a political play about a leader who disguises himself in order to mingle with the citizens, but who, while soliciting prostitutes (the doubles of intimacy?), encounters his estranged brother who was once united in a common cause, but has now split to lead the rebel faction.

The Usurper disrupts the timing (the seconds?), the delivery and finally the plot—which forces improvisations and the continued splitting and shifting of roles. At the end of the second act (rescued from chaos by the improvisational skill of the second prostitute) the Principle actor is released from his bondage, and the Usurper has disappeared (along with the second prostitute who may or may not have been in her dressing room). The show must go on, and the troupe must coalesce, and take new roles, the director and assistant even take to the stage as actors, to salv

As with years past, we’re going to spend the next four weeks highlighting the rest of the 25 titles on the BTBA fiction longlist. We’ll have a variety of guests writing these posts, all of which are centered around the question of “Why This Book Should Win.” Hopefully these are funny, accidental, entertaining, and informative posts that prompt you to read at least a few of these excellent works.

Click here for all past and future posts in this series.

Suicide by Edouard Levé, translated by Jan Steyn

Language: French

Country: France

Publisher: Dalkey Archive Press

Why This Book Should Win: The crazy intense backstory. The fact that Dalkey—one of the leading publishers of literature in translation—has yet to win a BTBA award.

Today’s post is written by Tom McCartan, who writes, works, and, lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He recently edited the collection Kurt Vonnegut: The Last Interview and Other Conversations for Melville House Publishing. His fiction has been published in Unsaid, the upcoming issue of which contains both Tom McCartan and Edouard Leve.

Despite my best efforts, it has proven somewhat impossible to discuss Edouard Levé’s Suicide without discussing Eduard Levé’s suicide. Let’s get it out of the way. Levé delivered Suicide to his editor ten days before taking his own life. This fact, as macabre as it is, is the house in which the novel lives and every review or blurb about Suicide from now to eternity will mention it. This is kind of a shame because Levé’s prose is good enough on its own. However, those inclined towards the postmodern are probably salivating over the idea, for it would be hard for a book to be more self-aware than Suicide. Some have even suggested that Suicide was Levé’s suicide note. I really hope that wasn’t the case, it would ruin the delicacy. Regardless, we’ll never know.

The novel does not have a plot, but rather its narrator (who could or could not be Levé) addresses a friend (wait, maybe the friend is Levé) who committed suicide twenty years ago. The result is homage in pointillist prose to a troubled soul explored in minute detail. It is a glimpse into the psychology of suicide. The narrator recounts the instances of his friend’s life in which he felt disassociated and addresses them back to his friend as if to absolve him of his suicide, although the narrator never claims to understand his friend’s pathos fully. We are only given the images and are left to wonder at reasons.

Suicide reads like a photo album. This is no surprise, considering that Levé was as much an accomplished photographer as he was anything else. The prose is clipped, almost terse; while each line can be seen to represent a single idea in just the same way a photo in an album represents one moment in time. These ideas, like collections of photos in an album, create events and distinct sections in a book where there are no chapters. Praise must be given to translator Jan Steyn who deftly maintained the integrity of each line/photograph while keeping the entire piece cohesive.

Suicide is at times beautiful, immensely sad at others, and in more moments than one might want to admit there is the potential in the text to be deeply relatable. I will not sit here and say, however, that Levé uses suicide as some sort of literary device for to teach us truth and/or bea

As with years past, we’re going to spend the next five weeks highlighting all 25 titles on the BTBA fiction longlist. We’ll have a variety of guests writing these posts, all of which are centered around the question of “Why This Book Should Win.” Hopefully these are funny, accidental, entertaining, and informative posts that prompt you to read at least a few of these excellent works.

Click here for all past and future posts in this series.

Zone by Mathias Enard, translated by Charlotte Mandell

Language: French

Country: France

Publisher: Open Letter Books

Why This Book Should Win: It’s a 517-page one-sentence novel. (Kind of.) How many other 517-page one-sentence novels have you ever heard of? That’s the kind of monumental project that should be rewarded.

Like with My Two Worlds, this Open Letter title has a pretty fun backstory. I heard about this via a review online and a quote from Claro claiming that it was “the novel of the decade, if not of the century.” (Realizing now that I’m sort of a sucker for respectable authors using that “X is the X of this [long time period]” mode of recommendation. Hmm.)

Anyway, based on a review, a hyperbolic blurb, and a relatively short sample (which erroneously ended with a period, but the less said about that the better), we made an offer on the book right before the Frankfurt Book Fair. Of course, the French publisher was hoping for a bidding war (they always are) and some Exorbitant Big Press Advance (who isn’t?), so they held our offer in check. Aannnddd then the economy collapsed and the Jonathan Littell book underperformed and the idea of a 517-page one-sentence novel sounded like a Bad Business Decision.

Which was awesome for us. Rights secured, we told Publishers Weekly who ran this as a notable Frankfurt acquisition, which led to the Chicago Tribune running this piece, cautiously titled: “The Longest Literary Sentence,” and which contained the dumbest quote (or at least one of the ten dumbest?) I’ve ever given:

But is the record-setter gibberish? Not at all, says Post.

“It’s told from inside this guy’s mind as he takes a train trip,” he says. “It has a lot of commas.”

Lot of . . . Jesus. Well, it does have commas by the truckful, and semicolons, em-dashes, and a whole slew of non-period punctuation. (Except the hyphellipses. If only . . .)

Anyway, that all happened well in advance of publishing the book. And in terms of the book itself, this truly is Epic Literature. It’s about the violence in the latter part of the twentieth century and is narrated by a former information agent who has decided to give it all up and is on a 517-kilometer long train ride to hand over all his secrets to the Vatican. During the train ride he has a little time to think, about his wartime experiences, about info gathering, about women he’s been with, about, well, basically everything. He also reads a book while he’s on the train, which serves as the sort of clinamen to this whole “one-sentence” thing.

But speaking of that—I may have praised it above, using this unique trait as a reason why this book deserves the

As with years past, we’re going to spend the next five weeks highlighting all 25 titles on the BTBA fiction longlist. We’ll have a variety of guests writing these posts, all of which are centered around the question of “Why This Book Should Win.” Hopefully these are funny, accidental, entertaining, and informative posts that prompt you to read at least a few of these excellent works.

Click here for all past and future posts in this series.

Lightning by Jean Echenoz, translated by Linda Coverdale

Language: French

Country: France

Publisher: The New Press

Why This Book Should Win: Tesla, duh. And Linda Coverdale. But mostly Tesla.

This was one of the first books we included in the currently-on-hiatus “Read This Next” project. As part of that, we ran a preview of the book, and interviewed Linda Coverdale, and ran a review of the book. And then, on the the Three Percent podcast on the Best Fiction of 2011, I plugged this again. As I did in last week’s podcast. In other words, I am fond of this book. (Worth noting that on last week’s podcast, Tom chose this as the book he thinks will win the award.)

Unlike similarly constructed sentences, such as “everyone likes a reenactment,” or “haven’t you always wondered what it would be like to live in Ireland in the 1800s?,” it’s FACT that everybody is interested in Tesla.

Just look at that shit! That is totally wicked insane. And named after TESLA. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg—this guy invented EVERYTHING.

In addition to all the awesomeness of his experiments (dude almost destroyed most of New York when he was just fucking around) and his strange obsessions with electricity and pigeons, one of the reasons Tesla keeps resurfacing every few years (most recently in Samantha Hunt’s The Invention of Everything Else) and seizing the public imagination is his captivating life story and how it can be interpreted into so many different archetypal myths.

For instance, there’s the idea of the solitary, eccentric inventor. Someone who is maybe a bit socially awkward (recluse), has some odd quirks (pigeons obsession), but can see the world in ways that no one else ever has (death ray).

Also, the thing that struck me in reading this book, and in reading about Tesla in general, is how he was one of the last pure inventors outside of the corporate world. Part of that was because he was THE WORST at business matters, some of that is because Edison was a total bastard (electrocuted an elephant), and because capitalist assholes have seemingly always taken advantage of the brain-muddled and trustworthy.

Getting to the book itself, this is part of Echenoz&rsquo

One of the precursors to the Oulipo, and cult-author extraordinaire, Raymond Roussel is one of those authors that everyone of a certain aesthetic leaning likes to rave about. He is the admiration of many a literary fan-boy, and if there was an international fiction cosplay festival, his hat, cane, and ‘stach would adorn many a nerd.

That said, his books still aren’t as widely read as they should be. Part of that is due to the fact that for the longest time Calder was the only publisher of Locus Solus and Impressions of Africa. Calder is a great home for both of these books (the quality of the Calder list taken as a whole will likely never be replicated), but there were various distribution and availability issues.

Thankfully, last summer Dalkey Archive issued Impressions of Africa in Mark Polizzotti’s new translation.

I haven’t read this version, but knowing the book, and knowing Mark, I’m 100% sure that it’s brilliant. And for those of you unfamiliar with this book, here’s the Dalkey description:

In a mythical African land, some shipwrecked and uniquely talented passengers stage a grand gala to entertain themselves and their captor, the great chieftain Talou. In performance after bizarre performance—starring, among others, a zither-playing worm, a marksman who can peel an egg at fifty yards, a railway car that rolls on calves’ lungs, and fabulous machines that paint, weave, and compose music—Raymond Roussel demonstrates why it is that André Breton termed him “the greatest mesmerizer of modern times.” But even more remarkable than the mindbending events Roussel details—as well as their outlandish, touching, or tawdry backstories—is the principle behind the novel’s genesis, a complex system of puns and double-entendres that anticipated (and helped inspire) such movements as Surrealism and Oulipo. Newly translated and with an introduction by Mark Polizzotti, this edition of Impressions of Africa vividly restores the humor, linguistic legerdemain, and conceptual wonder of Raymond Roussel’s magnum opus.

Anyway, the main point of this post is to gush on about Roussel in context of this fantastic essay by Alice Gregory that went up on the Poetry Foundation website earlier this week.

First of all, anything with the subtitle “the upside of crazy” is effing awesome in my book. But more importantly, this is a really interesting look at Roussel’s odd being and its relation to his very strange works. You really have to read the whole article, but here are a few bits:

“Whatever I wrote was surrounded by rays of light,” a young Raymond Roussel told his psychoanalyst, Pierre Janet. “I used to close the curtains, for I was afraid that the shining rays emanating from my pen might escape into the outside world through even the smallest chink; I wanted suddenly to throw back the screen and light up the world.” Roussel was speaking literally, and Janet, who would treat Roussel for years, was taking notes.

Though nobody knows for sure, it’s suspected that Roussel first started seeing Janet in the years just before World War I, almost a decade after that first ecstatic experience he described in their early sessions. The manic spell coincided with the editing of La Doublure, a novel in verse that took most of Roussel’s adolescence to complete and that he believed “would illuminate the entire universe” when it was published. When it finally was published in 1897, La Doublure was ignored by critics. The reception to his obsessively detailed and obviously unsal

The latest addition to our Reviews Section is a piece by contributing reviewer Larissa Kyzer on Jacques Poulin’s Mister Blue, which just came out from Archipelago Books in Sheila Fischman’s translation.

Larissa Kyzer is a regular reviewer for us who has a great interest in all things Scandinavian and Icelandic. Mister Blue doesn’t quite fit that, but it does sound like a really fun book:

The fictional world of Québécois novelist Jacques Poulin can, poetically speaking, be likened to a snow globe: a minutely-detailed landscape peppered with characters who appear to be frozen in one lovely, continuous moment. Mister Blue, recently published in a new English translation, captures this timelessness in a fluid and deceptively simple story about the complex bonds that can develop between completely unlike people, if only they are allowed to.

Brooklyn’s Archipelago Books has previously released two Poulin novels—Spring Tides and Translation is a Love Affair—both of which share some basic fundamentals with Mister Blue. Each of these slender novels feature reclusive literary types (authors and translators), their beloved cats (all with names worthy of T.S. Eliot’s Practical Cats: Matousalem, Mr. Blue, Charade, Vitamin), and enigmatic strangers who quickly insinuate themselves into the lives and imaginations of the aforementioned writers. But although Poulin frequently returns to the same themes, the same hyper-specific scenarios and characters in his work, each of his novels retain a freshness and idiosyncratic sweetness that reward readers with small revelations and happy coincidences.

Click here to read the entire piece.