new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: picture book biographies, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 48

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: picture book biographies in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

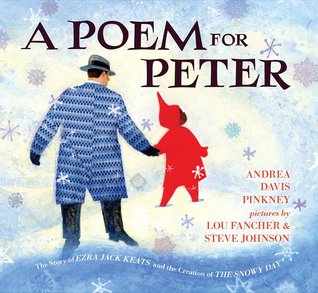

Children's picture book nerds have a few saints; Eric Carle, Leo Lionni, Trina Schart Hyman -(don't get me started. What about the Petershams and Tomie DePaola and Frank Asch?...Of course, I am showing my age.)

But chief among them, for his groundbreaking work in diversity, is Ezra Jack Keats. (Is that not a most poetic name?) His books about Peter and Peter's neighborhood brought the children of Keats' neighborhood,- black children, brown children, tan and white children - into mainstream publishing.

Everybody knows

The Snowy Day. Now thank to Andrea Davis Pinkney, and illustrators Steve Johnson and Lou Fancher, we get the story behind that book's creation - the story of Ezra Jack Keats.

A Poem for Peter hits the shelves on November 1st. I can't wait to read it.

Check out

the Ezra Jack Keats Foundation, while we wait for this book to arrive.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 10/5/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Misuzu Kaneko,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 poetry,

2016 picture book biographies,

David Jacobson,

Michiko Tsuboi,

Toshikado Hajiri,

Reviews,

poetry,

Best Books,

picture book biographies,

Sally Ito,

funny poetry,

middle grade poetry,

Add a tag

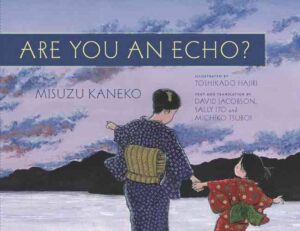

Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko

Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko

Narrative and Translation by David Jacobson, Sally Ito, and Michiko Tsuboi

Illustrated by Toshikado Hajiri

Chin Music Press

$19.50

ISBN: 9781634059626

Ages 5 and up

On shelves now

Recently I was at a conference celebrating the creators of different kinds of children’s books. During one of the panel discussions an author of a picture book biography of Fannie Lou Hamer said that part of the mission of children’s book authors is to break down “the canonical boundaries of biography”. I knew what she meant. A cursory glance at any school library or public library’s children’s room will show that most biographies go to pretty familiar names. It’s easy to forget how much we need biographies of interesting, obscure people who have done great things. Fortunately, at this conference, I had an ace up my sleeve. I knew perfectly well that one such book has just been published here in the States and it’s a game changer. Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko isn’t your typical dry as dust retelling of a life. It crackles with energy, mystery, tragedy, and, ultimately, redemption. This book doesn’t just break down the boundaries of biography. It breaks down the boundaries placed on children’s poetry, art, and translation too. Smarter and more beautiful than it has any right to be, this book challenges a variety of different biography/poetry conventions. The fact that it’s fun to read as well is just gravy.

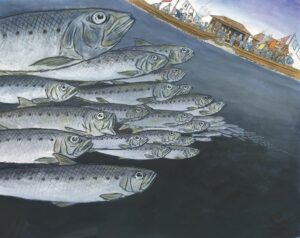

Part biography, part poetry collection, and part history, Are You an Echo? introduces readers to the life and work of celebrated Japanese poet Misuzu Kaneko. One day a man by the name of Setsuo Yazaki stumbled upon a poem called “Big Catch”. The poet’s seemingly effortless ability to empathize with the plight of fish inspired him to look into her other works. The problem? The only known book of her poems out there was caught in the conflagration following the firebombing of Tokyo during World War II. Still, Setsuo was determined and after sixteen years he located the poet’s younger brother who had her diaries, containing 512 of Misuzu’s poems. From this, Setsuo was able to piece together her life. Born in 1902, Misuzu Kaneko grew up in Senzaki in western Japan. She stayed in school at her mother’s insistence and worked in her mother’s bookstore. For fun she submitted some of her poems to a monthly magazine and shockingly every magazine she submitted them to accepted them. Yet all was not well for Misuzu. She had married poorly, contracted a disease from her unfaithful husband that caused her pain, and he had forced her to stop writing as well. Worst of all, when she threatened to leave he told her that their daughter’s custody would fall to him. Unable to see a way out of her problem, she ended her life at twenty-six, leaving her child in the care of her mother. Years passed, and the tsunami of 2011 took place. Misuzu’s poem “Are You an Echo?” was aired alongside public service announcements and it touched millions of people. Suddenly, Misuzu was the most famous children’s poet of Japan, giving people hope when they needed it. She will never be forgotten again. The book is spotted with ten poems throughout Misuzu’s story, and fifteen additional poems at the end.

There’s been a lot of talk in the children’s literature sphere about the role of picture book biographies. More specifically, what’s their purpose? Are they there simply to inform and delight or do they need to actually attempt to encapsulate the great moments in a person’s life, warts and all? If a picture book bio only selects a single moment out of someone’s life as a kind of example, can you still call it a biography? If you make up dialogue and imagine what might have happened in one scene or another, do those fictional elements keep it from the “Biography” section of your library or bookstore, or is there a place out there for fictionalized bios? These questions are new ones, just as the very existence of picture book biographies, in as great a quantity as we’re seeing them, is also new. One of the takeaways I’ve gotten from these conversations is that it is possible to tackle difficult subjects in a picture book bio, but it must be done naturally and for a good reason. So a story like Gary Golio’s Spirit Seeker can discuss John Coltrane’s drug abuse, as long as it serves the story and the character’s growth. On the flip side, Javaka Steptoe’s Radiant Child, a biography of Basquiat, makes the choice of discussing the artist’s mother’s fight with depression and mental illness, but eschews any mention of his own suicide.

There’s been a lot of talk in the children’s literature sphere about the role of picture book biographies. More specifically, what’s their purpose? Are they there simply to inform and delight or do they need to actually attempt to encapsulate the great moments in a person’s life, warts and all? If a picture book bio only selects a single moment out of someone’s life as a kind of example, can you still call it a biography? If you make up dialogue and imagine what might have happened in one scene or another, do those fictional elements keep it from the “Biography” section of your library or bookstore, or is there a place out there for fictionalized bios? These questions are new ones, just as the very existence of picture book biographies, in as great a quantity as we’re seeing them, is also new. One of the takeaways I’ve gotten from these conversations is that it is possible to tackle difficult subjects in a picture book bio, but it must be done naturally and for a good reason. So a story like Gary Golio’s Spirit Seeker can discuss John Coltrane’s drug abuse, as long as it serves the story and the character’s growth. On the flip side, Javaka Steptoe’s Radiant Child, a biography of Basquiat, makes the choice of discussing the artist’s mother’s fight with depression and mental illness, but eschews any mention of his own suicide.

Are You An Echo? is an interesting book to mention alongside these two other biographies because the story is partly about Misuzu Kaneko’s life, partly about how she was discovered as a poet, and partly a highlight of her poetry. But what author David Jacobson has opted to do here is tell the full story of her life. As such, this is one of the rare picture book bios I’ve seen to talk about suicide, and probably the only book of its kind I’ve ever seen to make even a passing reference to STDs. Both issues informed Kaneko’s life, depression, feelings of helplessness, and they contribute to her story. The STD is presented obliquely so that parents can choose or not choose to explain it to kids if they like. The suicide is less avoidable, so it’s told in a matter-of-fact manner that I really appreciated. Euphemisms, for the most part, are avoided. The text reads, “She was weak from illness and determined not to let her husband take their child. So she decided to end her life. She was only twenty-six years old.” That’s bleak but it tells you what you need to know and is honest to its subject.

But let’s just back up a second and acknowledge that this isn’t actually a picture book biography in the strictest sense of the term. Truthfully, this book is rife, RIFE, with poetry. As it turns out, it was the editorial decision to couple moments in Misuzu’s life with pertinent poems that gave the book its original feel. I’ve been wracking my brain, trying to come up with a picture book biography of a poet that has done anything similar. I know one must exist out there, but I was hard pressed to think of it. Maybe it’s done so rarely because the publishers are afraid of where the book might end up. Do you catalog this book as poetry or as biography? Heck, you could catalog it in the Japanese history section and still be right on in your assessment. It’s possible that a book that melds so many genres together could only have been published in the 21st century, when the influx of graphic inspired children’s literature has promulgated. Whatever the case, reading this book you’re struck with the strong conviction that the book is as good as it is precisely because of this melding of genres. To give up this aspect of the book would be to weaken it.

But let’s just back up a second and acknowledge that this isn’t actually a picture book biography in the strictest sense of the term. Truthfully, this book is rife, RIFE, with poetry. As it turns out, it was the editorial decision to couple moments in Misuzu’s life with pertinent poems that gave the book its original feel. I’ve been wracking my brain, trying to come up with a picture book biography of a poet that has done anything similar. I know one must exist out there, but I was hard pressed to think of it. Maybe it’s done so rarely because the publishers are afraid of where the book might end up. Do you catalog this book as poetry or as biography? Heck, you could catalog it in the Japanese history section and still be right on in your assessment. It’s possible that a book that melds so many genres together could only have been published in the 21st century, when the influx of graphic inspired children’s literature has promulgated. Whatever the case, reading this book you’re struck with the strong conviction that the book is as good as it is precisely because of this melding of genres. To give up this aspect of the book would be to weaken it.

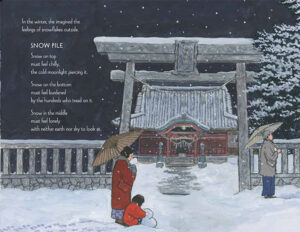

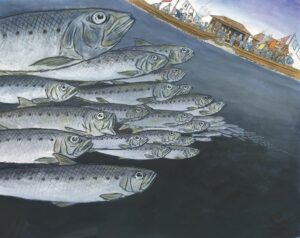

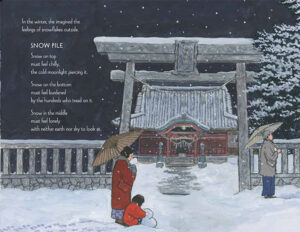

Right off the bat I was impressed by the choice of poems. The first one you encounter is called “Big Catch” and it tells about a village that has caught a great number of fish. The poem ends by saying, “On the beach, it’s like a festival / but in the sea they will hold funerals / for the tens of thousands dead.” The researcher Setsuo Yazaki was impressed by the poet’s empathy for the fish, and that empathy is repeated again and again in her poems. “Big Catch” is actually one of her bleaker works. Generally speaking, the poems look at the world through childlike eyes. “Wonder” contemplates small mysteries, in “Beautiful Town” the subject realizes that a memory isn’t from life but from a picture in a borrowed book, and “Snow Pile” contemplates how the snow on the bottom, the snow on the top, and the snow in the middle of a pile must feel when they’re all pressed together. The temptation would be to call Kaneko the Japanese Emily Dickenson, owing to the nature of the discovery of her poems posthumously, but that’s unfair to both Kaneko and Dickenson. Kenko’s poems are remarkable not just because of their original empathy, but also because they are singularly childlike. A kid would get a kick out of reading these poems. That’s no mean feat.

Mind you, we’re dealing with a translation here. And considering how beautifully these poems read, you might want a note from the translators talking about their process. You can imagine, then, how thrilled I was to find a half-page’s worth of a “Translators’ Note” explaining aspects of the work here that never would have occurred to me in a million years. The most interesting problem came down to culture. As Sally Ito and Michiko Tsuboi write, “In Japanese, girls have a particular way of speaking that is affectionate and endearing . . . However, English is limited in its capacity to convey Misuzu’s subtle feminine sensibility and the elegant nuances of her classical allusions. We therefore had to skillfully work our way through both languages, often producing several versions of a poem by discussing them on Skype and through extensive emails – Michiko from Japan, Sally from China – to arrive at the best possible translations in English.” It makes a reader really sit back and admire the sheer levels of dedication and hard work that go into a book of this sort. If you read this book and find that the poems strike you as singularly interesting and unique, you may now have to credit these dedicated translators as greatly as you do the original subject herself. We owe them a lot.

Mind you, we’re dealing with a translation here. And considering how beautifully these poems read, you might want a note from the translators talking about their process. You can imagine, then, how thrilled I was to find a half-page’s worth of a “Translators’ Note” explaining aspects of the work here that never would have occurred to me in a million years. The most interesting problem came down to culture. As Sally Ito and Michiko Tsuboi write, “In Japanese, girls have a particular way of speaking that is affectionate and endearing . . . However, English is limited in its capacity to convey Misuzu’s subtle feminine sensibility and the elegant nuances of her classical allusions. We therefore had to skillfully work our way through both languages, often producing several versions of a poem by discussing them on Skype and through extensive emails – Michiko from Japan, Sally from China – to arrive at the best possible translations in English.” It makes a reader really sit back and admire the sheer levels of dedication and hard work that go into a book of this sort. If you read this book and find that the poems strike you as singularly interesting and unique, you may now have to credit these dedicated translators as greatly as you do the original subject herself. We owe them a lot.

In the back of the book there is a note from the translators and a note from David Jacobson who wrote the text of the book that didn’t include the poetry. What’s conspicuously missing here is a note from the illustrator. That’s a real pity too since biographical information about artist Toshikado Hajiri is missing. Turns out, Toshikado is originally from Kyoto and now lives in Anan, Tokushima. Just a cursory glance at his art shows a mild manga influence. You can see it in the eyes of the characters and the ways in which Toshikado chooses to draw emotions. That said, this artist is capable of also conveying great and powerful moments of beauty in nature. The sunrise behind a beloved island, the crush of chaos following the tsunami, and a peach/coral/red sunset, with a grandmother and granddaughter silhouetted against its beauty. What Toshikado does here is match Misuzu’s poetry, note for note. The joyous moments she found in the world are conveyed visually, matching, if never exceeding or distracting from, her prowess. The end result is more moving than you might expect, particularly when he includes little human moments like Misuzu reading to her daughter on her lap or bathing her one last time.

Here is what I hope happens. I hope that someday soon, the name “Misuzu Kaneko” will become better known in the United States. I hope that we’ll start seeing collections of her poems here, illustrated by some of our top picture book artists. I hope that the fame that came to Kaneko after the 2011 tsunami will take place in America, without the aid of a national disaster. And I hope that every child that reads, or is read, one of her poems feels that little sense of empathy she conveyed so effortlessly in her life. I hope all of this, and I hope that people find this book. In many ways, this book is an example of what children’s poetry should strive to be. It tells the truth, but not the truth of adults attempting to impart wisdom upon their offspring. This is the truth that the children find on their own, but often do not bother to convey to the adults in their lives. Considering how much of this book concerns itself with being truthful about Misuzu’s own life and struggles, this conceit matches its subject matter to a tee. Beautiful, mesmerizing, necessary reading for one and all.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Misc: An article in PW about the translation.

Last week I was sick. Sick as a dog sick. Sick in that way where you feel the cool breezes coming through your window and have a fleeting glimpse of how lucky you are to be sick at the end of the summer rather than even a week earlier when your misery could have only have been compounded by hot winds and bright, horrible, happy sunlight.

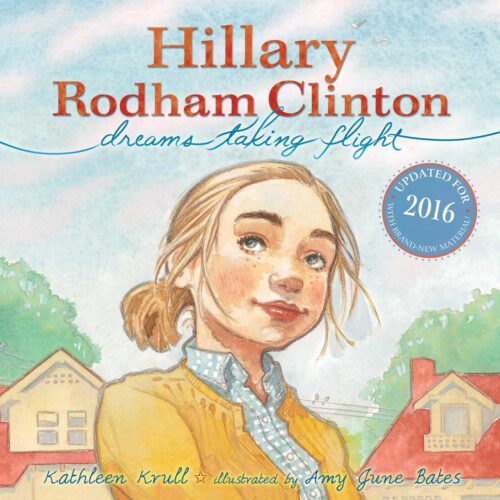

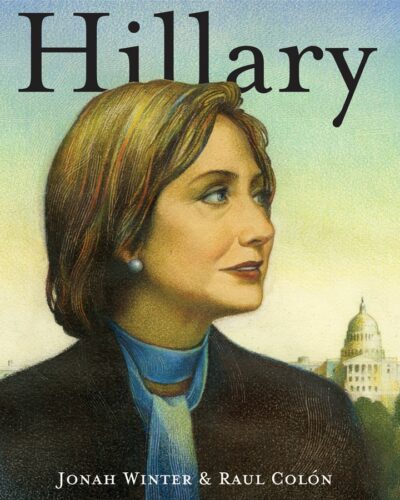

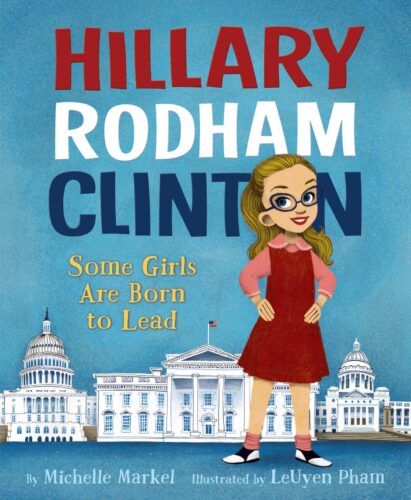

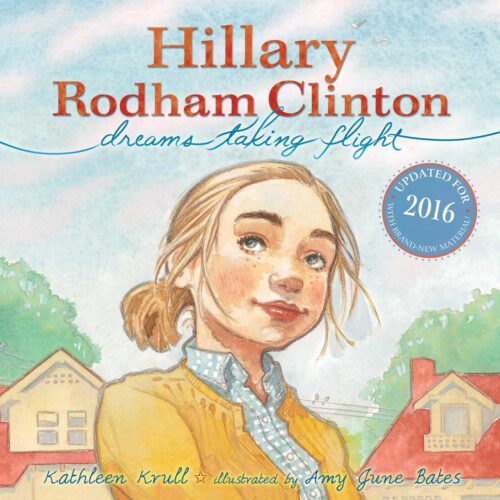

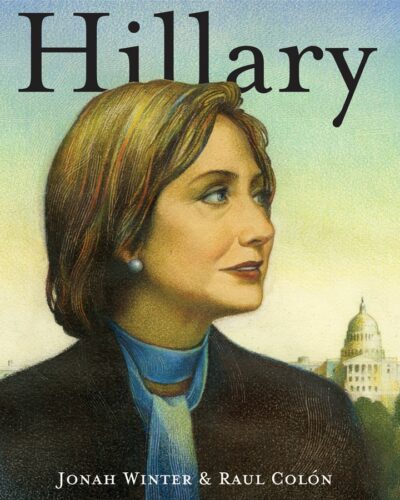

In the midst of all this lovely blah-ness I was given the chance to speak with a German reporter about political picture book biographies. Thanks to the fever I’ve only a mild inkling of what I said (we’ll all find out together, yay!) but I do remember a long discussion of American picture book biographies and nuance. Look at the bios of Hillary out there for kids and you’re not going to find much within them beyond praise. How true is that of other picture book biographies? Are they capable of showing several sides of an individual or are they, by definition, only able to show the good sides of their subjects and never the bad?

I’ve been pondering this for the past week and I don’t know if I’m any closer to an answer. A picture book biography by its very nature is supposed to tell a child more about a subject. Moreover, that subject is supposed to be someone that child should learn and grow from as well as emulate in their own lives. You will not find picture book biographies of Hitler or Ted Bundy because that flies in the face of a picture book bio’s purpose in life. The only time you can come close is when you write a parody for adults like A Child’s First Book of Trump.

But is that actually true? I mean, if a kid is supposed to emulate a picture book biography’s subject and you don’t show their flaws and failures, doesn’t that automatically make the subject seem otherworldly and perfect? Isn’t there value in displaying the problematic areas and showing how someone surmounted them?

I set out to locate a couple picture book biographies of people who led complicated lives. How did their picture book biographers choose to handle their less than stellar personal qualities? When drawing up the list, I was surprised to find that the most examples involve drugs. I made a conscious effort to include some of those, but to come up with other personal failings as well.

Jimi Hendrix

Personal Difficulty: Died of drug overdose

Does the Book Address This? Sure, but not in the text for kids. Since the text pretty much just shows him as a kid, that was a given. Now one way these books get around the problem of a problematic life is simply to put all the less-than-stellar stuff in the backmatter. If a book does that, can you honestly say that it’s discussing a subject’s complicated life head-on? By the same token, it’s obviously there and has the additional advantage of being readily available to a teacher or parent IF and only IF they want to share it. In this case, mentioning Jimi’s death wouldn’t have made sense in the main body of the text.

Coco Chanel

Personal Difficulty: Got cozy with a Nazi

Do These Books Address This? Ah, nope. But I’ve a theory on this one anyway. Seems to me that when a person’s personal life involved drug abuse, or even physical violence, that’s something a picture book biography can work with. Sex, in any form, is far more difficult. Read on and you’ll see what I mean a little later.

John Coltrane

Personal Difficulty: Drug addiction

Does the Book Address This? Yes. In fact, this turned out to be one of the very few picture book biographies I could find where the text written for kids discussed the fact that the subject of the book had personal failings. As I wrote in my review, “You see the days when his deep sadness caused him to start drinking early on. You see his experiments with drugs and the idea some musicians harbored that it would make them better.” There’s even an in-depth “Author’s Note: Musicians and Drug Use” section at the end. Now the author of this book, Gary Golio, also wrote the aforementioned Jimi Hendrix biography so he’s no stranger to writing about complicated men. If you seek complexity in a picture book biography, this is where you start.

Johnny Cash

Personal Difficulty: Several, but let’s just stick with the fact that he left his wife for Rosanne.

Does the Book Address This? Not really. It definitely mentions Rosanne and how much Johnny admired her, but the storyline stops strategically before they get togehter. If you want to get into the sticky subject of infidelity the text of the book won’t help you out. But could it even? Could any picture book biography tackle infidelity in any manner without the topic tipping everything in the text in only that direction? Can we state for the record, then, that infidelity cannot ever be discussed in a picture book biography?

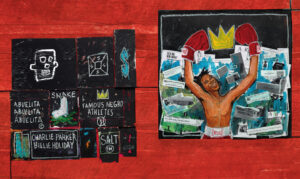

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Personal Difficulty: Family mental issues and drug addiction

Does the Book Address This? Yep. The problems with his mother are discussed at length in the text. The drug problems come up in the backmatter. This is a pretty good example of a book that has found the right balance in the public and personal, and has found a way to make an honest picture book biography that touches on the big issues and how they formed the man as an artist without letting them take over the book itself.

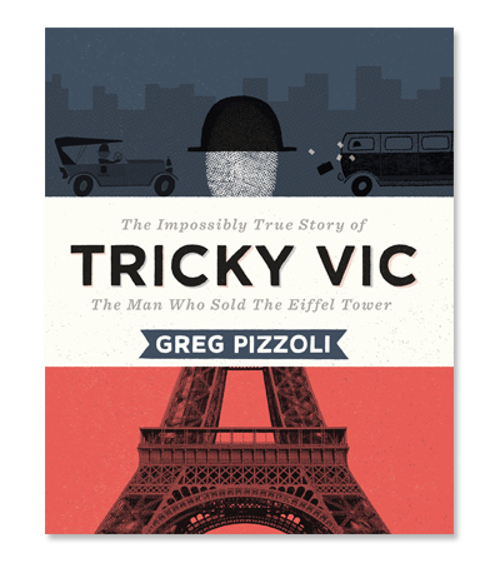

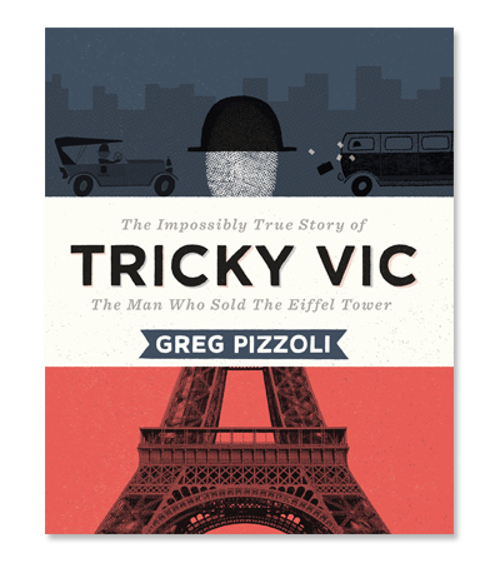

Robert Miller a.k.a. Tricky Vic

Personal Difficulty: Um . . . his whole entire life? Remember when I said you couldn’t write a bio of a villain? Well, Tricky Vic was more of an anti-hero, but that’s splitting hairs. This may well be the only picture book bio I’ve seen of a true shyster. He was a con man, and he didn’t exactly repent. Or learn. Or grow.

Personal Difficulty: Um . . . his whole entire life? Remember when I said you couldn’t write a bio of a villain? Well, Tricky Vic was more of an anti-hero, but that’s splitting hairs. This may well be the only picture book bio I’ve seen of a true shyster. He was a con man, and he didn’t exactly repent. Or learn. Or grow.

Does the Book Address This? The book doesn’t address anything BUT this! How did Pizzoli do it? There wasn’t even an outcry against this book when it came out. People were on board with it. I wonder if they saw it more as a history than a bio. I wonder too if the fact that Vic isn’t that well known contributed to the lack of protestation. If you wrote a biography of a famous sadist, people would assume the book was, by definition, in favor of that person. But if the person is low-level and not particularly well known it flies right under the radar. Much to chew on here.

Conclusion: Let’s say someone wanted to write a serious picture book biography of Donald Trump tomorrow and have it published by a major publisher. Let us also say that this person was not personally associated with Mr. Trump and wanted to present him as honestly as possible to a child readership. Finally, let’s say that this person wanted this to be a “good” book. Could it be done?

I don’t know the answer to this question. I told the reporter that American picture book biographies were capable of nuance, and I’ll stand by that. But they are also, by their very design, meant to inspire as well as inform. If you take away that initial intent, do you do harm to the form itself?

Deep thoughts for a Tuesday, folks. Be interested in your opinions.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 7/27/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

nonfiction picture books,

Best Books,

picture book biographies,

Little Brown and Company,

African-American history,

Javaka Steptoe,

African-American biographies,

African-American picture book biographies,

African-American authors and illustrators,

2016 Caldecott contenders,

Best Books of 2016,

Reviews 2016,

2016 nonfiction picture books,

2016 picture book biographies,

Add a tag

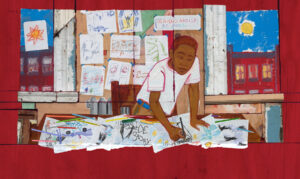

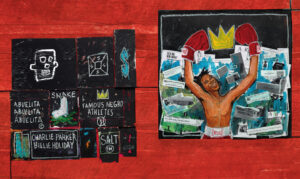

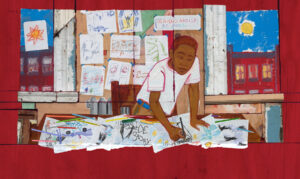

Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat

Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat

By Javaka Steptoe

Little, Brown & Co.

$17.99

ISBN: 978-0-316-21388-2

Ages 5 and up

On shelves October 25th

True Story: I’m working the children’s reference desk of the Children’s Room at 42nd Street of New York Public Library a couple years ago and a family walks in. They go off to read some books and eventually the younger son, I’d say around four years of age, approaches my desk. He walks right up to me, looks me dead in the eye, and says, “I want all your Javaka Steptoe books.” Essentially this child was a living embodiment of my greatest dream for mankind. I wish every single kid in America followed that little boy’s lead. Walk up to your nearest children’s librarian and insist on a full fledged heaping helping of Javaka. Why? Well aside from the fact that he’s essentially children’s book royalty (his father was the groundbreaking African-American picture book author/illustrator John Steptoe) he’s one of the most impressive / too-little-known artists working today. But that little boy knew him and if his latest picture book biography “Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat” is even half as good as I think it is, a whole host of children will follow suit. But don’t take my word for it. Take that four-year-old boy’s. That kid knew something good when he saw it.

“Somewhere in Brooklyn, a little boy dreams of being a famous artist, not knowing that one day he will make himself a KING.” That boy is an artist already, though not famous yet. In his house he colors on anything and everything within reach. And the art he makes isn’t pretty. It’s, “sloppy, ugly, and sometimes weird, but somehow still BEAUTIFUL.” His mother encourages him, teaches him, and gives him an appreciation for all the art in the world. When he’s in a car accident, she’s the one who hands him Gray’s Anatomy to help him cope with what he doesn’t understand. Still, nothing can help him readily understand his own mother’s mental illness, particularly when she’s taken away to live where she can get help. All the same, that boy, Jean-Michel Basquiat, shows her his art, and with determination he grows up, moves to Manhattan, and starts his meteoric rise in the art scene. All this so that when, at long last, he’s at the top of his game, it’s his mother who sits on the throne at his art shows. Additional information about Basquiat appears at the back of the book alongside a key to the motifs in his work, an additional note from Steptoe himself on what Basquiat’s life and work can mean to young readers, and a Bibliography.

Javaka Steptoe apparently doesn’t like to make things easy for himself. If he wanted to, he could illustrate all the usual African-American subjects we see in books every year. Your Martin Luther Kings and Rosa Parks and George Washington Carvers. So what projects does he choose instead? Complicated heroes who led complicated lives. Artists. Jimi Hendrix and guys like that. Because for all that kids should, no, MUST know who Basquiat was, he was an adult with problems. When Steptoe illustrated Gary Golio’s bio of Hendrix (Jimi: Sounds Like a Rainbow) critics were universal in their praise. And like that book, Steptoe ends his story at the height of Basquiat’s fame. I’ve seen some folks comment that the ending here is “abrupt” and that’s not wrong. But it’s also a natural high, and a real time in the man’s life when he was really and truly happy. When presenting a subject like Basquiat to a young audience you zero in on the good, acknowledge the bad in some way (even if it’s afterwards in an Author’s Note), and do what you can to establish precisely why this person should be mentioned alongside those Martin Luther Kings, Rosa Parks, and George Washington Carvers.

Javaka Steptoe apparently doesn’t like to make things easy for himself. If he wanted to, he could illustrate all the usual African-American subjects we see in books every year. Your Martin Luther Kings and Rosa Parks and George Washington Carvers. So what projects does he choose instead? Complicated heroes who led complicated lives. Artists. Jimi Hendrix and guys like that. Because for all that kids should, no, MUST know who Basquiat was, he was an adult with problems. When Steptoe illustrated Gary Golio’s bio of Hendrix (Jimi: Sounds Like a Rainbow) critics were universal in their praise. And like that book, Steptoe ends his story at the height of Basquiat’s fame. I’ve seen some folks comment that the ending here is “abrupt” and that’s not wrong. But it’s also a natural high, and a real time in the man’s life when he was really and truly happy. When presenting a subject like Basquiat to a young audience you zero in on the good, acknowledge the bad in some way (even if it’s afterwards in an Author’s Note), and do what you can to establish precisely why this person should be mentioned alongside those Martin Luther Kings, Rosa Parks, and George Washington Carvers.

There’s this moment in the film Basquiat when David Bowie (playing Andy Warhol) looks at some of his own art and says off-handedly, “I just don’t know what’s good anymore.” I have days, looking at the art of picture books when I feel the same way. Happily, there wasn’t a minute, not a second, when I felt that way about Radiant Child. Now I’m going to let you in on a little secret: Do you know what one of the most difficult occupations to illustrate a picture book biography about is? Artist. Because right from the start the illustrator of the book is in a pickle. Are you going to try to replicate the art of this long dead artist? Are you going to grossly insert it into your own images, even if the book isn’t mixed media to begin with? Are you going to try to illustrate the story in that artist’s style alone, relegating images of their actual art to the backmatter? Steptoe addresses all this in his Note at the back of the book. As he says, “Instead of reproducing or including copies of real Basquiat paintings in this book, I chose to create my own interpretations of certain pieces and motifs.” To do this he raided Basquiat’s old haunts around NYC for discarded pieces of wood to paint on. The last time I saw this degree of attention paid to painting on wood in a children’s book was Paul O. Zelinsky’s work on Swamp Angel. In Steptoe’s case, his illustration choice works shockingly well. Look how he manages to give the reader a sense of perspective when he presents Picasso’s “Guernica” at an angle, rather than straight on. Look how the different pieces of wood, brought together, fit, sometimes including characters on the same piece to show their closeness, and sometimes painting them on separate pieces as a family is broken apart. And the remarkable thing is that for all that it’s technically “mixed-media”, after the initial jolt of the art found on the title page (a full wordless image of Basquiat as an adult surrounded by some of his own imagery) you’re all in. You might not even notice that even the borders surrounding these pictures are found wood as well.

The precise age when a child starts to feel that their art is “not good” anymore because it doesn’t look realistic or professional enough is relative. Generally it happens around nine or ten. A book like Radiant Child, however, is aimed at younger kids in the 6-9 year old range. This is good news. For one thing, looking at young Basquiat vs. older Basquiat, it’s possible to see how his art is both childlike and sophisticated all at once. A kid could look at what he’s doing in this book and think, “I could do that!” And in his text, Steptoe drills into the reader the fact that even a kid can be a serious artist. As he says, “In his house you can tell a serious ARTIST dwells.” No bones about it.

The precise age when a child starts to feel that their art is “not good” anymore because it doesn’t look realistic or professional enough is relative. Generally it happens around nine or ten. A book like Radiant Child, however, is aimed at younger kids in the 6-9 year old range. This is good news. For one thing, looking at young Basquiat vs. older Basquiat, it’s possible to see how his art is both childlike and sophisticated all at once. A kid could look at what he’s doing in this book and think, “I could do that!” And in his text, Steptoe drills into the reader the fact that even a kid can be a serious artist. As he says, “In his house you can tell a serious ARTIST dwells.” No bones about it.

How much can a single picture book bio do? Pick a good one apart and you’ll see all the different levels at work. Steptoe isn’t just interested in celebrating Basquiat the artist or encouraging kids to keep working on their art. He also notes at the back of the book that the story of Basquiat’s relationship with his mother, who suffered from mental illness, was very personal to him. And so, Basquiat’s mother remains an influence and an important part of his life throughout the text. You might worry, and with good reason, that the topic of mental illness is too large for a biography about someone else, particularly when that problem is not the focus of the book. How do you properly address such an adult problem (one that kids everywhere have to deal with all the time) while taking care to not draw too much attention away from the book’s real subject? Can that even be done? Sacrifices, one way or another, have to be made. In Radiant Child Steptoe’s solution is to show Jean-Michel within the lens of his art’s relationship to his mother. She talks to him about art, takes him to museums, and encourages him to keep creating. When he sees “Guernica”, it’s while he’s holding her hand. And because Steptoe has taken care to link art + mom, her absence is keenly felt when she’s gone. The book’s borders go a dull brown. Just that single line “His mother’s mind is not well” says it succinctly. Jean-Michel is confused. The kids reading the book might be confused. But the feeling of having a parent you are close to leave you . . . we can all relate to that, regardless of the reason. It’s just going to have a little more poignancy for those kids that have a familiarity with family members that suffer mental illnesses. Says Steptoe, maybe with this book those kids can, “use Basquiat’s story as a catalyst for conversation and healing.”

That’s a lot for a single picture book biography to take on. Yet I truly believe that Radiant Child is up to the task. It’s telling that in the years since I became a children’s librarian I’ve seen a number of Andy Warhol biographies and picture books for kids but the closest thing I ever saw to a Basquiat bio for children was Life Doesn’t Frighten Me as penned by Maya Angelou, illustrated by Jean-Michel. And that wasn’t even really a biography! For a household name, that’s a pretty shabby showing. But maybe it makes sense that only Steptoe could have brought him to proper life and to the attention of a young readership. In such a case as this, it takes an artist to display another artist. Had Basquiat chosen to create his own picture book autobiography, I don’t think he could have done a better job that what Radiant Child has accomplished here. Timely. Telling. Overdue.

On shelves October 25th.

Source: F&G sent from publisher for review.

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus

Okay. So now we’re finally getting some interesting picture book biographies on a regular basis. When I was a kid you had your Helen Keller and your Abraham Lincoln and you were GRATEFUL! These days, people are interested in celebrating more than just the same ten people over and over again. Why this year alone I’ve seen some incredibly interesting picture book biographies of comparatively obscure figures. These include . . .

- Ada Lovelace, Poet of Science: The First Computer Programmer by Diane Stanley, ill. Jessie Hartland

- Ada’s Ideas: The Story of Ada Lovelace, the World’s First Computer Programmer by Fiona Robinson (Ada’s really hot this year)

- Anything But Ordinary: The True Story of Adelaide Herman, Queen of Magic by Mara Rockliff, ill. Iacopo Bruno

- Around America to Win the Vote: Two Suffragists, a Kitten, and 10,000 Miles by Mara Rockliff, ill. Hadley Hooper

- Cloth Lullaby: The Woven Life of Louise Bourgeois by Amy Novesky, ill. Isabelle Arsenault

- Esquivel! Space‐Age Sound Artist by Susan Wood, ill. Duncan Tonatiuh

- Fancy Party Gowns: The Story of Ann Cole Lowe by Deborah Blumenthal, ill. Laura Freeman

- I Dissent: Ruth Bader Ginsburg Makes Her Mark by Debbie Levy, ill. Elizabeth Baddeley

- The Kid from Diamond Street: The Extraordinary Story of Baseball Legend Edith Houghton by Audrey Vernick, ill. Steven Salerno

- Lift Your Light a Little Higher: The Story of Stephen Bishop: Slave‐Explorer by Heather Henson, ill. Bryan Collier

- Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean‐Michel Basquiat by Javaka Steptoe

- Solving the Puzzle Under the Sea: Marie Tharp Maps the Ocean Floor by Robert Burleigh, ill. Raul Colon

- To the Stars! The First American Woman to Walk in Space by Carmella Van Vleet & Dr. Kathy Sullivan, ill. Nicole Wong

- Whoosh! Lonnie Johnson’s Super‐Soaking Stream of Inventions by Chris Barton, ill. Don Tate

- The William Hoy Story by Nancy Churnin, ill. Jez Tuya

And those are just the ones I’ve seen!

It’s encouraging. And then I wonder – do people need suggestions for more fun biographies? Because if they do have I got the woman for you!

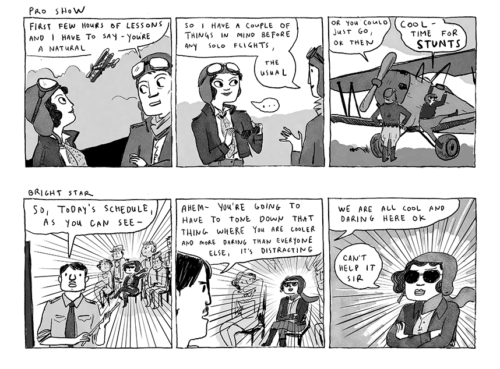

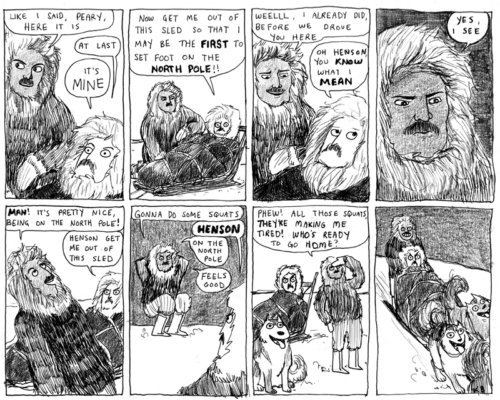

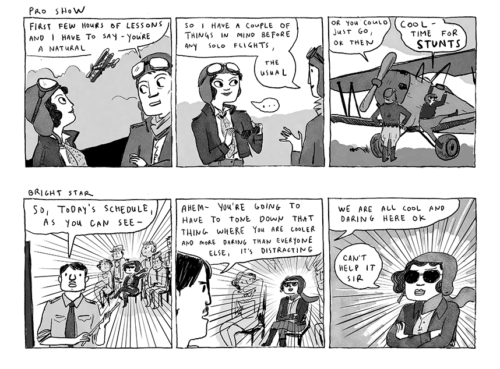

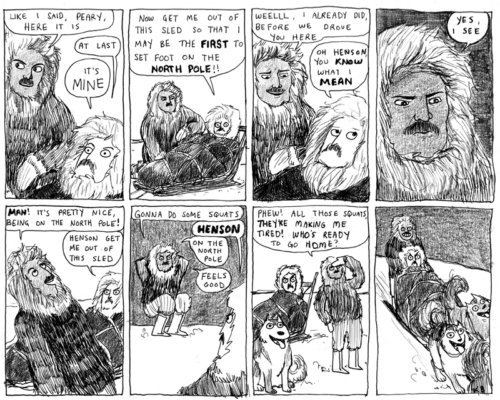

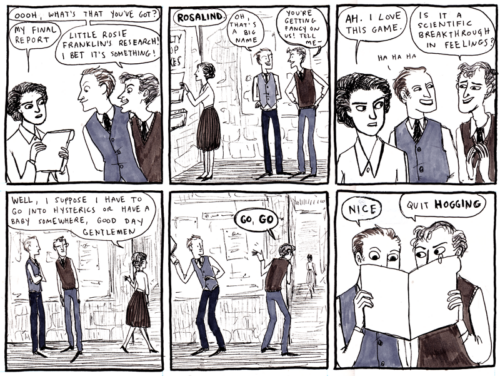

First off, meet Kate Beaton. You may only know her from her two Scholastic books, last year’s The Princess and the Pony and this year’s King Baby. But Kate has been running an online comic site called Hark, A Vagrant! for years. There are many lovely things about the site, but I’m particularly fond of her brief biographical comics on obscure historical figures. She’s been doing them for years and once in a while I really do see one turned into a picture book (paging Ada Lovelace . . .). So in today’s goofy post I’m going to pull out some of Kate’s work in the hopes that maybe there’s an author or illustrator there who’d like to write a picture book biography about someone awesome and relatively unknown.

By the way, you can follow these links to read these comics in a clearer format, if you like. And I think you can even buy prints of them, if you want.

First up:

Katherine Sui Fun Cheung

I legitimately had never heard of her. A badass Asian-American aviatrix heroine? Um… how is she NOT in a picture book bio? Because quite frankly we could use a huge uptick in our Asian-American women bios in general. Particularly if they involve air stunts.

Matthew Henson

Is it weird that there isn’t a really well-known Henson picture book biography out there? I guess his life wasn’t completely perfect (second family at the North Pole and all) but as African-American explorers go, he’s fantastic. As it happens, this was the first Hark, A Vagrant! comic I ever read. I was a fan for life afterwards.

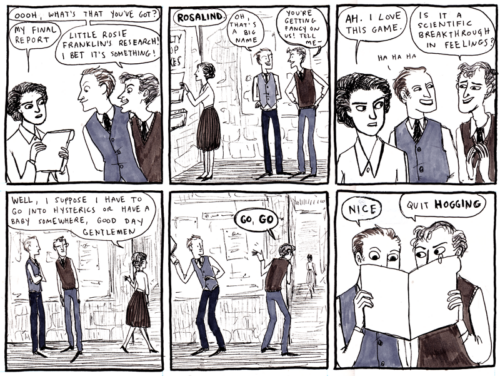

Rosalind Franklin

She helps to discover DNA! She doesn’t get credit for it! This story has everything!

Dr. Sara Josephine Baker

She’s so often just linked to Typhoid Mary, but Ms. Baker did wonders for infant mortality rates and just generally sounds like an amazing woman. And I like how Beaton draws her hair.

Ida B. Wells

I’m pretty sure we’ve had picture book bios on her before, but the only one I can remember was for older kids.

Mary Seacole

Again, never heard of her. And as Kate put it regarding Nightingale, “” This is timely too since as of three days ago there was a report in The Guardian over the huge furor over a statue honoring Seacole’s achievements. Read it, when you get a chance. Then write a bio of Seacole.

Harvey Milk

Maybe not so obscure thanks to his biopic, but sure as shooting lacking in some significant pic bios.

Of course when all is said and done, Kate should really just make her own picture book biographies. Or, do a book for older readers of Biographies You Should REALLY Know and Don’t.

Oh, it would work.

Happy writing!

You may have seen the Guardian article the other day ‘Oh, what a big gun you have': NRA rewrites fairytales to include firearms. The title pretty much is the whole story, except that these are tales posted on the NRA’s website and not (at this time) actual published books. I was looking at the post and the books themselves and for whatever reason it made me think about the current crop of picture books for kids today about the candidate for president. Candidate singular, you see, because of the people running, only one has several picture book biographies to her name.

Flashback: The year is 2008 and I’m attending a Simon & Schuster publisher preview. Here is my write-up from the time. What you will not find in the write-up was what happened when the John McCain picture book biography was shown to the librarians in attendance. They were . . . let us say less than pleased as a whole, though obviously I cannot speak for everyone. The editor, incensed, stood and suddenly made a passionate speech about having to show both sides of every story. That we owe it to our young readers to have picture book biographies of the candidates of both parties.

Fast Forward to 2016: Now I cannot say what the future holds in political publishing. All I can say is that at this moment in time, there are at least three picture book biographies out about Hillary Clinton and only Hillary Clinton. They are:

I confess that it was a co-worker who pointed out to me the red, white, and blue streaks in her hair. Totally missed that on a first read.

I’ll not comment on these individually (though I do a fantastic one-woman show reenacting the opening of one of these three books – see if you can guess which one). What I will say is that in the children’s book publishing industry few find themselves surprised when only one candidate gets a book. I’m no psychic, but I think it’s safe to say that we probably won’t be seeing a Trump or Cruz picture book bio from a mainstream publisher in the next year. Now I could be wrong, but the difference between McCain and these two potential candidates is immense. Quite frankly, McCain was better suited to the format.

So what does this say about the publishing industry of 2016 and is it the same or different from 2008? No idea. One thing is certain, though. No matter who secures the Republican nomination, picture book bios of that person will appear. They’ll just be coming from smaller, conservative presses.

By:

Roger Sutton,

on 2/10/2016

Blog:

Read Roger - The Horn Book editor's rants and raves

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews of the Week,

hbmjan16,

hbmjan16revs,

Reviews,

Nonfiction,

primary,

Recommended Books,

Horn Book Magazine,

picture book biographies,

Add a tag

The Kid from Diamond Street: The Extraordinary Story of Baseball Legend Edith Houghton

The Kid from Diamond Street: The Extraordinary Story of Baseball Legend Edith Houghton

by Audrey Vernick;

illus. by Steven Salerno

Primary Clarion 40 pp.

3/16 978-0-544-61163-4 $17.99 g

Edith Houghton was “magic on the field,” a baseball legend of the 1920s. Playing starting shortstop for the

all-women’s professional team the Philadelphia Bobbies, she drew fans to the ballpark with her impressive offensive and defensive talent. Besides that, Edith was just ten years old; her uniform was too big, her pants kept falling down, and her too-long sleeves encumbered her play. But she was good, and the older players took “The Kid” under their wing. And that’s the real story here, told through Vernick’s conversational text. It’s not so much about the baseball action but the team — barnstorming through the Northwest U.S. playing against male teams; experiencing ship life aboard the President Jefferson on the way to Japan; playing baseball in Japan; and learning about Japanese culture. Salerno’s appealing charcoal, ink, and gouache illustrations evoke a bygone era of baseball with smudgy-looking uniforms, sepia tones, and double-page spreads for a touch of ballpark grandeur. An informative author’s note tells more of Houghton’s story — the other women’s teams she played for, her job as a major league scout for the Philadelphia Phillies, and being honored at the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006. An engaging story that reminds readers that “baseball isn’t just numbers and statistics, men and boys. Baseball is also ten-year-old girls, marching across a city to try out for a team intended for players twice their age.”

From the January/February 2016 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

The post Review of The Kid from Diamond Street: The Extraordinary Story of Baseball Legend Edith Houghton appeared first on The Horn Book.

Cheating marathoners; a trailblazing sports reporter; a girl shortstop; and an illegal integrated b-ball game. Here are some nonfiction sports picture books that capture the dramatic action both on and off the track/field/court.

Meghan McCarthy’s The Wildest Race Ever: The Story of the 1904 Olympic Marathon describes America’s first Olympic marathon, which took place in St. Louis during the World’s Fair. It was a zany one, with cheating runners (one caught a ride in a car), contaminated water, pilfered peaches, and strychnine poisoning. McCarthy’s chatty text focuses on a few of the frontrunners and other colorful characters, shown in her recognizable cartoonlike acrylic illustrations. A well-paced — and winning — nonfiction picture book. (Simon/Wiseman, 5–8 years)

Meghan McCarthy’s The Wildest Race Ever: The Story of the 1904 Olympic Marathon describes America’s first Olympic marathon, which took place in St. Louis during the World’s Fair. It was a zany one, with cheating runners (one caught a ride in a car), contaminated water, pilfered peaches, and strychnine poisoning. McCarthy’s chatty text focuses on a few of the frontrunners and other colorful characters, shown in her recognizable cartoonlike acrylic illustrations. A well-paced — and winning — nonfiction picture book. (Simon/Wiseman, 5–8 years)

Edith Houghton was “magic on the field,” a baseball legend of the 1920s. Playing starting shortstop for the all-women’s professional team the Philadelphia Bobbies, she drew fans to the ballpark with her impressive talent. Besides that, Edith — “The Kid” — was just ten years old. The Kid from Diamond Street: The Extraordinary Story of Baseball Legend Edith Houghton by Audrey Vernick relates, in conversational text, Houghton’s life on the team. Appealing digitally colored charcoal, ink, and gouache illustrations by Steven Salerno evoke a bygone era of baseball. (Clarion, 5–8 years)

Edith Houghton was “magic on the field,” a baseball legend of the 1920s. Playing starting shortstop for the all-women’s professional team the Philadelphia Bobbies, she drew fans to the ballpark with her impressive talent. Besides that, Edith — “The Kid” — was just ten years old. The Kid from Diamond Street: The Extraordinary Story of Baseball Legend Edith Houghton by Audrey Vernick relates, in conversational text, Houghton’s life on the team. Appealing digitally colored charcoal, ink, and gouache illustrations by Steven Salerno evoke a bygone era of baseball. (Clarion, 5–8 years)

“It seemed that Mary was born loving sports,” writes Sue Macy in her affectionate portrait of a pioneering journalist, Miss Mary Reporting: The True Story of Sportswriter Mary Garber. It was during WWII that Garber “got her big break” running the sports page of Winston-Salem’s Twin City Sentinel while the (male) sportswriters were fighting in the war. For much of the next six decades, she worked in sports reporting, blazing trails for female journalists. Macy’s succinct text is informative and engaging, her regard for her subject obvious. C. F. Payne’s soft, sepia-toned, mixed-media illustrations — part Norman Rockwell, part caricature — provide the right touch of nostalgia. (Simon/Wiseman, 5–8 years)

“It seemed that Mary was born loving sports,” writes Sue Macy in her affectionate portrait of a pioneering journalist, Miss Mary Reporting: The True Story of Sportswriter Mary Garber. It was during WWII that Garber “got her big break” running the sports page of Winston-Salem’s Twin City Sentinel while the (male) sportswriters were fighting in the war. For much of the next six decades, she worked in sports reporting, blazing trails for female journalists. Macy’s succinct text is informative and engaging, her regard for her subject obvious. C. F. Payne’s soft, sepia-toned, mixed-media illustrations — part Norman Rockwell, part caricature — provide the right touch of nostalgia. (Simon/Wiseman, 5–8 years)

John Coy’s Game Changer: John McLendon and the Secret Game (based on a 1996 New York Times article by Scott Ellsworth) tells the dramatic story of an illegal college basketball game planned and played in secret in Jim Crow–era North Carolina. On a Sunday morning in 1944, the (white) members of the Duke University Medical School basketball team (considered “the best in the state”) slipped into the gym at the North Carolina College of Negroes to play the Eagles, a close-to-undefeated black team coached by future Hall of Famer John McClendon. Coy’s succinct narrative is well paced, compelling, and multilayered, focusing on the remarkable game but also placing it in societal and historical context. Illustrations by Randy DuBurke nicely capture the story’s atmosphere and its basketball action. (Carolrhoda, 6–9 years)

John Coy’s Game Changer: John McLendon and the Secret Game (based on a 1996 New York Times article by Scott Ellsworth) tells the dramatic story of an illegal college basketball game planned and played in secret in Jim Crow–era North Carolina. On a Sunday morning in 1944, the (white) members of the Duke University Medical School basketball team (considered “the best in the state”) slipped into the gym at the North Carolina College of Negroes to play the Eagles, a close-to-undefeated black team coached by future Hall of Famer John McClendon. Coy’s succinct narrative is well paced, compelling, and multilayered, focusing on the remarkable game but also placing it in societal and historical context. Illustrations by Randy DuBurke nicely capture the story’s atmosphere and its basketball action. (Carolrhoda, 6–9 years)

From the February 2016 issue of Notes from the Horn Book.

The post Winning sports picture books appeared first on The Horn Book.

By:

Roger Sutton,

on 11/11/2015

Blog:

Read Roger - The Horn Book editor's rants and raves

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews of the Week,

hbmnov15,

hbmnov15revs,

Reviews,

Nonfiction,

Recommended Books,

Horn Book Magazine,

picture book biographies,

Vaunda Micheaux Nelson,

Add a tag

The Book Itch: Freedom, Truth & Harlem’s

Greatest Bookstore

The Book Itch: Freedom, Truth & Harlem’s

Greatest Bookstore

by Vaunda Micheaux Nelson; illus. by R. Gregory Christie

Primary, Intermediate Carolrhoda 32 pp.

11/15 978-0-7613-3943-4 $17.99

e-book ed. 978-1-4677-4618-2 $17.99

If the central character of Nelson’s Boston Globe–Horn Book Award-winning No Crystal Stair (rev. 3/12) was the author’s great-uncle, Lewis Michaux, this picture book adaptation of the same source material shifts the focus just enough to give younger readers an introduction to his singular achievement: the National Memorial African Bookstore, founded by Michaux in Harlem in the 1930s. Where No Crystal Stair had more than thirty narrators, this book has but one, Michaux’s young son Lewis, a late-in-life child who witnessed the store’s doings during the tumultuous 1960s. Studded with Michaux’s aphorisms (“Don’t get took! Read a book!”), the book successfully conveys the vibrancy of the bookstore and its habitués, including Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X, whose assassination provides the emotional climax of the story. Christie, whose black-and-white drawings are such an inextricable part of No Crystal Stair, is here allowed full pages drenched with expressionistic color to convey the spirit of the place, time, and people. While middle-graders might need some context to understand that the book is set fifty years in the past, its concerns remain: as Michaux “jokes” to Lewis, “Anytime more than three black people congregate, the police get nervous.” Nelson provides full documentation in a biographical note, and some of the bookseller’s best slogans decorate the endpapers.

From the November/December 2015 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

The post Review of The Book Itch appeared first on The Horn Book.

In our November/December issue, our editors asked Vaunda Micheaux Nelson about revisiting the source material of her BGHB Award–winning No Crystal Stair in new picture book The Book Itch. Read the full review of The Book Itch here.

In our November/December issue, our editors asked Vaunda Micheaux Nelson about revisiting the source material of her BGHB Award–winning No Crystal Stair in new picture book The Book Itch. Read the full review of The Book Itch here.

Horn Book Editors: What compelled you to revisit the material from No Crystal Stair to create your picture book The Book Itch?

Vaunda Micheaux Nelson: I was writing in Lewis Jr.’s voice in No Crystal Stair when I realized that his perspective might entice younger readers into Lewis Sr.’s world. Moved by Lewis Jr.’s story, I wanted to explore how his father and the bookstore influenced him in particular. You could say Lewis Jr. cut in line and stepped onto the speaker’s platform, making me pause the longer work.

From the November/December 2015 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

The post Vaunda Micheaux Nelson on The Book Itch appeared first on The Horn Book.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 9/9/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

2015 Sibert Award contender,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 nonfiction,

2015 nonfiction picture books,

2015 biography,

Reviews,

nonfiction,

Don Tate,

Chris Barton,

nonfiction picture books,

biographies,

Best Books,

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers,

picture book biographies,

Add a tag

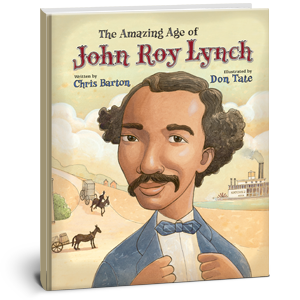

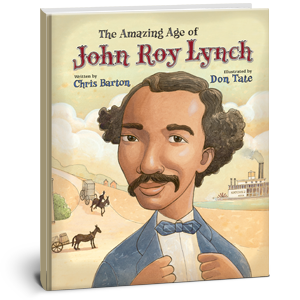

The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch

The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch

By Chris Barton

Illustrated by Don Tate

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers

$17.00

ISBN: 978-0-8028-5379-0

Ages 4-8

On shelves now

“It’s the story of a guy who in ten years went from teenage field slave to U.S. Congressman.” Come again? That’s the pitch author Chris Barton pulled out when he wanted to describe this story to others. You know, children’s book biographies can be very easy as long as you cover the same fifteen to twenty people over and over again. And you could forgive a child for never imagining that there were remarkable people out there beyond Einstein, Tubman, Jefferson, and Sacajawea. People with stories that aren’t just unknown to kids but to whole swaths of adults as well. So I always get kind of excited when I see someone new out there. And I get extra especially excited when the author involved is Chris Barton. Here’s a guy who performed original research to write a picture book biography of the guys who invented Day-Glo colors (The Day-Glo Brothers) so you know you’re in safe hands. The inclusion of illustrator Don Tate was not something I would have thought up myself, but by gum it turns out that he’s the best possible artist for this story! Tackling what turns out to be a near impossible task (explaining Reconstruction to kids without plunging them into the depths of despair), this keen duo present a book that reads so well you’re left wondering not just how they managed to pull it off, but if anyone else can learn something from their technique.

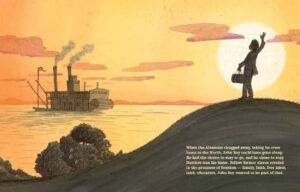

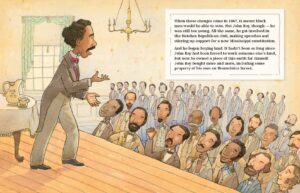

From birth until the age of sixteen John Roy Lynch was a slave. The son of an overseer who died before he could free his family, John Roy began life as a house slave but was sent to the fields when his high-strung mistress made him the brunt of her wrath. Not long after, The Civil War broke out and John Roy bought himself a ride to Natchez and got a job. He started out as a waiter than moved on to pantryman, photographer, and in time orator and even Justice of the Peace. Then, at twenty-four years of age, John Roy Lynch was elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives where he served as Speaker of the House. The year was 1869, and these changes did not pass without incident. Soon an angry white South took its fury out on its African American population and the strides that had been made were rescinded violently. John Roy Lynch would serve out two terms before leaving office. He lived to a ripe old age, dying at last in 1939. A Historical Note, Timeline, Author’s Note, Illustrator’s Note, Bibliography of books “For Further Reading”, and map of John’s journey and the Reconstructed United States circa 1870 appear at the end.

How do you write a book for children about a time when things were starting to look good and then plummeted into bad for a very very long time? I think kids have this perception (oh heck, a bunch of adults too) that we live in the best of all possible worlds. For example, there’s a children’s book series called Infinity Ring where the basic premise is that bad guys have gone and changed history and now it’s up to our heroes to put everything back because, obviously, this world we live in right now is the best. Simple, right? Their first adventure is to make sure Columbus “discovers” America so . . . yup. Too often books for kids reinforce the belief that everything that has happened has to have happened that way. So when we consider how few books really discuss Reconstruction, it’s not exactly surprising. Children’s books are distinguished, in part, by their capacity to inspire hope. What is there about Reconstruction to cause hope at all? And how do you teach that to kids?

How do you write a book for children about a time when things were starting to look good and then plummeted into bad for a very very long time? I think kids have this perception (oh heck, a bunch of adults too) that we live in the best of all possible worlds. For example, there’s a children’s book series called Infinity Ring where the basic premise is that bad guys have gone and changed history and now it’s up to our heroes to put everything back because, obviously, this world we live in right now is the best. Simple, right? Their first adventure is to make sure Columbus “discovers” America so . . . yup. Too often books for kids reinforce the belief that everything that has happened has to have happened that way. So when we consider how few books really discuss Reconstruction, it’s not exactly surprising. Children’s books are distinguished, in part, by their capacity to inspire hope. What is there about Reconstruction to cause hope at all? And how do you teach that to kids?

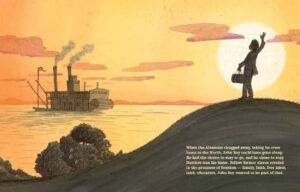

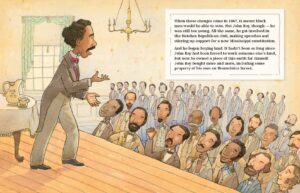

Barton’s solution is clever because rather than write a book about Reconstruction specifically, he’s found a historical figure that guides the child reader effortlessly through the time period. Lynch’s life is perfect for every step of this process. From slavery to a freedom that felt like slavery. Then slow independence, an education, public speaking, new responsibilities, political success, two Congressional terms, and then an entirely different life after that (serving in the Spanish-American War as a major, moving to Chicago, dying). Barton shows his rise and then follows his election with a two-page spread of KKK mayhem, explaining that the strides made were taken back “In a way, the Civil War wasn’t really over. The battling had not stopped.” And after quoting a speech where Lynch proclaims that America will never be free until “every man, woman, and child can feel and know that his, her, and their rights are fully protected by the strong arm of a generous and grateful Republic,” Barton follows it up with, “If John Roy Lynch had lived a hundred years (and he nearly did), he would not have seen that come to pass.” Barton guides young readers to the brink of the good and then explains the bad, giving context to just how long the worst of it continued. He also leaves it up to them to determine if Lynch’s dream has come to fruition or not (classroom debate time!).

And he plays fair. These days I read nonfiction picture books with my teeth clenched. Why? Because I’ve started holding them to high standards (doggone it). And there are so many moments in this book that could have been done incorrectly. Heck, the first image you see when you open it up is of John Roy Lynch’s family, his white overseer father holding his black wife tenderly as their kids stand by. I saw it and immediately wondered how we could believe that Lynch’s parents ever cared for one another. Yet a turn of the page and Barton not only puts Patrick Lynch’s profession into context (“while he may have loved these slaves, he most likely took the whip to others”) but provides information on how he attempted to buy his wife and children. Later there is some dialogue in the book, as when Lynch’s owner at one point joshes with him at the table and John Roy makes the mistake of offering an honest answer. Yet the dialogue is clearly taken from a text somewhere, not made up to fit the context of the book. I loathe faux dialogue, mostly because it’s entirely unnecessary. Barton shows clearly that one need never rely upon it to make a book exemplary.

And he plays fair. These days I read nonfiction picture books with my teeth clenched. Why? Because I’ve started holding them to high standards (doggone it). And there are so many moments in this book that could have been done incorrectly. Heck, the first image you see when you open it up is of John Roy Lynch’s family, his white overseer father holding his black wife tenderly as their kids stand by. I saw it and immediately wondered how we could believe that Lynch’s parents ever cared for one another. Yet a turn of the page and Barton not only puts Patrick Lynch’s profession into context (“while he may have loved these slaves, he most likely took the whip to others”) but provides information on how he attempted to buy his wife and children. Later there is some dialogue in the book, as when Lynch’s owner at one point joshes with him at the table and John Roy makes the mistake of offering an honest answer. Yet the dialogue is clearly taken from a text somewhere, not made up to fit the context of the book. I loathe faux dialogue, mostly because it’s entirely unnecessary. Barton shows clearly that one need never rely upon it to make a book exemplary.

Finally, you just have to stand in awe of Barton’s storytelling. Not making up dialogue is one thing. Drawing a natural link between a life and the world in which that life lived is another entirely. Take that moment when John Roy answers his master honestly. He’s banished to hard labor on a plantation after his master’s wife gets angry. Then Barton writes, “She was not alone in rage and spite and hurt and lashing out. The leaders of the South reacted the same way to the election of a president – Abraham Lincoln – who was opposed to slavery.” See how he did that? He managed to bring the greater context of the times in line with John Roy’s personal story. Many is the clunky picture book biography that shoehorns in the era or, worse, fails to mention it at all. I much preferred Barton’s methods. There’s an elegance to them.

I’ve been aware of Don Tate for a number of years. No slouch, the guy’s illustrated numerous children’s books, and even wrote (but didn’t illustrate) one that earned him an Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Honor Award (It Jes’ Happened: When Bill Traylor Started to Draw). His is a seemingly simple style. I wouldn’t exactly call it cartoony, but it is kid friendly. Clear lines. Open faces. His watercolors go for honesty and clarity and do not come across as particularly evocative. But I hadn’t ever seen the man do nonfiction, I’ll admit. And while it probably took me a page or two to understand, once I realized why Don Tate was the perfect artist for “John Roy Lynch” it all clicked into place. You see, books about slavery for kids usually follow a prescribed pattern. Some of them go for hyperrealism. Books with art by James Ransome, Eric Velasquez, Floyd Cooper, or E.B Lewis all adhere closely to this style. Then there are the books that are a little more abstract. Books with art by R. Gregory Christie, for example, traipse closely to art worthy of Jacob Lawrence. And Shane W. Evans has a style that’s significantly artistic. A more cartoony style is often considered too simplistic for the heavy subject matter or, worse, disrespectful. But what are we really talking about here? If the book is going to speak honestly about what slavery really was, the subjugation of whole generations of people, then art that hews closely to the truth is going to be too horrific for kids. You need someone who can cushion the blow, to a certain extent. It isn’t that Tate is shying away from the horrors. But when he draws it it loses some of its worst terrors. There is one two-page spread in this book that depicts angry whites whipping and lynching their black neighbors.  It’s not shown as an exact moment in time, but rather a composite of events that would have happened then. And there’s something about Tate’s style that makes it manageable. The whip has not yet fallen and the noose has not yet been placed around a neck, but the angry mobs are there and you know that the worst is imminent. Most interesting to me too is that far in the background a white woman and her two children just stand there, neither approving nor condemning the action. I think you could get a very good conversation out of kids about this family. What are they feeling? Whose side are they on? Why don’t they do something?

It’s not shown as an exact moment in time, but rather a composite of events that would have happened then. And there’s something about Tate’s style that makes it manageable. The whip has not yet fallen and the noose has not yet been placed around a neck, but the angry mobs are there and you know that the worst is imminent. Most interesting to me too is that far in the background a white woman and her two children just stand there, neither approving nor condemning the action. I think you could get a very good conversation out of kids about this family. What are they feeling? Whose side are they on? Why don’t they do something?

And Tate has adapted his style, you can see. Compare the heads and faces in this book to those in one of his earlier books like, Ron’s Big Mission by Rose Blue, in this one he modifies the heads, making them a bit smaller, in proportion with the rest of the body. I was particularly interested in how he did faces as well. If you watch Lynch’s face as a child and teen it’s significant how he keeps is features blank in the presence of white people. Not expressionless, but devoid of telltale thoughts. As a character, the first time he smiles is when he finally has a job he can be paid for. With its silhouetted moments, good design sense, tapered but not muted color palette, and attention to detail, Mr. Tate puts his all into what is by far his most sophisticated work to date.

This year rage erupted over the fact that the Confederate flag continues to fly over the South Carolina statehouse grounds. To imagine that the story Barton relates here does not have immediate applications to contemporary news is facile. As he mentions in his Author’s Note, “I think it’s a shame how little we question why the civil rights movement in this country occurred a full century following the emancipation of the slaves rather than immediately afterward.” So as an author he found an inspiring, if too little known, story of a man who did something absolutely astounding. A story that every schoolchild should know. If there’s any justice in the universe, after reading this book they will. Reconstruction done right. Nonfiction done well.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews:

Misc: For you, m’dear? An educator’s guide.

Videos: A book trailer and everything!

With all of the push to get young children more interested in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) topics, many schools, libraries, and after school programs are integrating these topics into their activities. And, with so many great picture book biographies of scientists available, there is no reason that storytime activities and at-home reading time can’t also complement these activities and help to inspire young children to pursue their interest in STEM topics. Check out some of these books to bring out the inner scientist in your preschool through third grade students.

On a Beam of Light: A Story of Albert Einstein by Jennifer Berne, illustrated by Vladimir Radunsky

On a Beam of Light: A Story of Albert Einstein by Jennifer Berne, illustrated by Vladimir Radunsky

This book starts with Einstein’s childhood and introduces readers to a boy who didn’t talk, but did look with wonder at the world around him. As it progresses through to his later life, the book focuses on the way that Einstein thought and how this led to his contributions to science. The illustrations fit well with this focus as they have a decidedly dreamy quality to them. Perfect for younger readers.

Look Up!: Henrietta Leavitt, Pioneering Woman Astronomer by Robert Burleigh, illustrated by Raúl Colón

Look Up!: Henrietta Leavitt, Pioneering Woman Astronomer by Robert Burleigh, illustrated by Raúl Colón

Though Henrietta Leavitt may not be a name that is familiar to most, she made key contributions to the field of astronomy during her time at the Harvard College Observatory during the late 1800s. This biography brings her work to life through a combination of beautiful artwork and a compelling story. Leavitt’s story and the included information about astronomy will inspire young children to study the stars.

The Watcher: Jane Goodall’s Life with the Chimps by Jeanette Winter

The Watcher: Jane Goodall’s Life with the Chimps by Jeanette Winter

Jane Goodall remains one of the most famous primatologists ever and this book tells her life story starting during her childhood in England through to her time working among the chimpanzees in Tanzania with the scientist Louis Leakey. The book also includes Goodall’s important work as an advocate and activist for chimpanzees and, as such, will introduce children who love animals to the world of activism as well.

Star Stuff: Carl Sagan and the Mysteries of the Cosmos by Stephanie Roth Sisson

Star Stuff: Carl Sagan and the Mysteries of the Cosmos by Stephanie Roth Sisson

Another great book for children who are interested in stars and the field of astronomy, this book offers an insight into Carl Sagan’s life and inspiration. Starting with a trip to the New York World’s Fair in 1939 and his nights spent looking out his window to stare at the stars, this book follows Sagan throughout his life and career as a renowned astronomer who worked with NASA. This is a wonderful addition to any collection of science picture books.

A Boy and a Jaguar by Alan Rabinowitz, illustrated by Catia Chien

A Boy and a Jaguar by Alan Rabinowitz, illustrated by Catia Chien

The only book on this list written by its subject, this book tells the story of Alan Rabinowitz, a biologist and conservationist whose love of animals helped him to overcome his stuttering when he found that he could talk to animals without any problem. This winner of the 2015 Schneider Family Book Award will inspire all students to pursue their passions.

This list offers a few suggestions for great science biographies, but there are plenty more to choose from. Let me know in the comments if your favorites didn’t make my list. I also love learning about new science biography picture books!

The post Inspire interest in STEM with science biography picture books appeared first on The Horn Book.

We recently received Luna & Me: The True Story of a Girl Who Lived in a Tree to Save a Forest by Jenny Sue Kostecki-Shaw (Holt/Ottaviano, May 2015). It’s sort of dual picture-book biography, telling the stories of a thousand-year-old redwood tree called Luna, which was slated to be logged; and of young activist Julia Butterfly Hill, who lived in the tree for over two years to prevent it from being cut down.

We recently received Luna & Me: The True Story of a Girl Who Lived in a Tree to Save a Forest by Jenny Sue Kostecki-Shaw (Holt/Ottaviano, May 2015). It’s sort of dual picture-book biography, telling the stories of a thousand-year-old redwood tree called Luna, which was slated to be logged; and of young activist Julia Butterfly Hill, who lived in the tree for over two years to prevent it from being cut down.

When I was an undergrad attending Humboldt State University in northern (waaaaay northern) California, I read Hill’s 2000 memoir The Legacy of Luna: The Story of a Tree, a Woman and the Struggle to Save the Redwoods (HarperOne) for a sociology class. Hill discusses the day-to-day experiences of living in the tree (she had a lot of help) and depicts the volatile — occasionally verging on violent — conflict between the activists and the Pacific Lumber Company. My class discussed The Legacy of Luna and Hill’s tree-sit as an exercise in local sociology: Luna is located about 40 miles from HSU, in the same county. We were reading the memoir only a year or two after its publication, and tensions between activists and loggers were still high. In fact, the year after the book came out, the tree was vandalized.

When I was an undergrad attending Humboldt State University in northern (waaaaay northern) California, I read Hill’s 2000 memoir The Legacy of Luna: The Story of a Tree, a Woman and the Struggle to Save the Redwoods (HarperOne) for a sociology class. Hill discusses the day-to-day experiences of living in the tree (she had a lot of help) and depicts the volatile — occasionally verging on violent — conflict between the activists and the Pacific Lumber Company. My class discussed The Legacy of Luna and Hill’s tree-sit as an exercise in local sociology: Luna is located about 40 miles from HSU, in the same county. We were reading the memoir only a year or two after its publication, and tensions between activists and loggers were still high. In fact, the year after the book came out, the tree was vandalized.

Though I tended to side with Hill and other activists trying to protect the old-growth forest, I soon realized (no doubt as the professor intended) that the situation was extremely complex. The logging industry had long been a major part of the region’s economy, but was starting to flag, and environmentalists were attempting to curtail it further. To make matters worse, there was an “us” and “them” mentality at work: activists tended to be young out-of-towners attracted to the area by the university or by liberal politics, while loggers were frequently locals whose families had lived there for generations. (The university’s mascot? The lumberjack.) Our professor mentioned that, due to its anti-logging stance, Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax had caused some controversy when taught in local elementary schools.

In Luna & Me, Kostecki-Shaw is definitely on Hill’s (and Luna’s) side, emphasizing the activist’s courage and determination as well as the historical and ecological value of the ancient tree and others like it. Though she doesn’t demonize the loggers, Kostecki-Shaw doesn’t humanize them, either. (The tree Luna, on the other hand, is personified quite a bit.) There is no mention of loggers’ need to make their livelihood and feed their families. Perhaps that sort of sociological context is a tall order for a primary-level picture book. Kostecki-Shaw writes in her author’s note that she “chose to tell of Julia’s time in Luna in [her] own way — simplifying a very complex, intense, and political journey and depicting her as a girl” rather than as an adult.

Will Luna & Me be embraced by teachers, librarians, and parents in northern California? Or, like The Lorax, will it be viewed by some as problematic? I hope, either way, that it will provoke some thoughtful discussion.

Have you come across any children’s books that are divisive for your own community?

The post Luna, Julia, and readers appeared first on The Horn Book.

Most biographies for kids feature upstanding citizens and if they do have a fault or two, the writer quickly glosses over them.