new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: 2016 reviews, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 33

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: 2016 reviews in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 11/17/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

middle grade graphic novels,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2017 Caldecott contenders,

2016 graphic novels,

2016 middle grade graphic novels,

Reviews,

graphic novels,

Matt Phelan,

Best Books,

Candlewick,

Add a tag

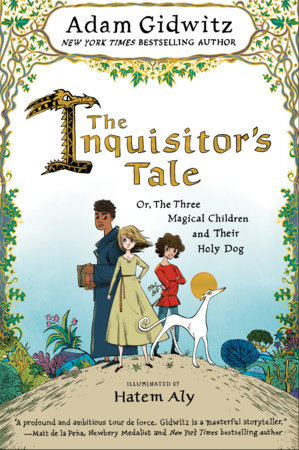

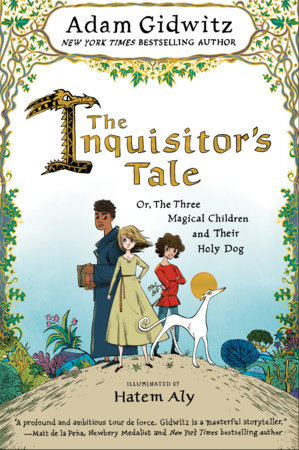

Snow White: A Graphic Novel

Snow White: A Graphic Novel

By Matt Phelan

Candlewick Press

$19.99

ISBN: 978-0-7636-7233-1

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

I’d have said it couldn’t be done. The Snow White fairytale has been told and retold and overdone to death until there’s not much left to do but forget about it entirely. Not that every graphic novel out there has to be based on an original idea. And not that the world is fed up with fairytales now (it isn’t). But when I heard about Matt Phelan’s Snow White: A Graphic Novel I was willing to give it a chance simply because I trusted its creator and not its material. The crazy thing is that even before I picked it up, it threw me for a loop. I heard that the story was recast in 1920s/ early-1930s Depression-era New York City. For longer than I’d care to admit I just sort of sat there, wracking my brain and trying desperately to remember anything I’d ever seen that was similar. I’ve seen fairytales set during the Depression before, but never Snow White. Then I picked the book up and was struck immediately by how beautiful it was. Finally I read through it and almost every element clicked into place like the gears of a clock. I know Matt Phelan has won a Scott O’Dell Award for The Storm in the Barn and I know his books get far and wide acclaim. Forget all that. This book is his piece de resistance. A bit of fairytale telling, to lure in the kids, and a whole whopping dollop of cinematic noir, deft storytelling, and clever creation, all set against a white, wintery backdrop.

The hardened detective thinks he’s seen it all, but that was before he encountered the corpse in the window of a department store, laid out like she was sleeping. No one could account for her. No one except maybe the boy keeping watch from across the street. When the detective asks for the story he doesn’t get what he wants, but we, the readers, do. Back in time we zip to when a little girl lost her mother to illness and later her father fell desperately in love with a dancer widely proclaimed to be the “Queen of the Follies.” Sent away to a boarding school, the girl returns years later when her father has died and his will leaves all his money in a trust to Snow. Blinded by rage, the stepmother (who is not innocent in her husband’s death) calls in a favor with a former stagehand to do away with her pretty impediment, but he can’t do the deed. What follows is a gripping tale of the seven street kids that take Snow under their wing (or is it the other way around?), some stage make-up, a syringe, an apple, and an ending so sweet you could have gotten it out of a fairytale.

Let’s get back to this notion I have that the idea of setting Snow White during the Depression in New York is original. It honestly goes above and beyond the era. I could swear I’d never read or seen a version where the seven dwarfs were seven street kids. Or where the evil stepmother was a star of the Ziegfeld Follies. Snow’s run from Mr. Hunt is through Central Park through various shantytowns and he presents the stepmother with a pig’s heart procured at a butcher. Even making her glass coffin a window at Macy’s, or the magic mirror an insidious ticker tape, feels original and perfectly in keeping with the setting. You begin to wonder how no one else has ever thought to do this before.

Let’s get back to this notion I have that the idea of setting Snow White during the Depression in New York is original. It honestly goes above and beyond the era. I could swear I’d never read or seen a version where the seven dwarfs were seven street kids. Or where the evil stepmother was a star of the Ziegfeld Follies. Snow’s run from Mr. Hunt is through Central Park through various shantytowns and he presents the stepmother with a pig’s heart procured at a butcher. Even making her glass coffin a window at Macy’s, or the magic mirror an insidious ticker tape, feels original and perfectly in keeping with the setting. You begin to wonder how no one else has ever thought to do this before.

You’d also be forgiven for reading the book, walking away, giving it a year, and then remembering it as wordless. It isn’t, but Phelan’s choosy with his wordplay this time. Always a fan of silent sequences, I was struck by the times we do see words. Whether it’s the instructions on the ticker tape (a case could easily be made that these instructions are entirely in the increasingly deranged step-mother’s mind), Snow’s speech about how snow beautifies everything, or the moment when each one of the boys tells her his name, Phelan’s judiciousness makes the book powerful time and time again. Can you imagine what it would have felt like if there had been an omniscient narrator? The skin on the back of my neck shudders at the thought.

For all that the words are few and far between, you often get a very good sense of the characters anyway. Snow’s a little bit Maria Von Trapp and a little bit Mary Poppins to the boys. I would have liked Phelan to give her a bit more agency than, say, Disney did. For example, when her step-mother informs her, after the reading of her father’s will, that her old room is no longer her own, I initially misread Snow’s response to be that she was going out to find a new home on her own. Instead, she’s just going for a walk and gets tracked down by Mr. Hunt in the process. It felt like a missed beat, but not something that sinks the ship. Contrast that with the evil stepmother. Without ever being graphic about it, not even once, this lady just exudes sex. It’s kind of hard to explain. There’s that moment when the old stagehand remembers when he once turned his own body into a step stool so that she could make her grand entrance during a show. There’s also her first entrance in the Follies, fully clothed but so luscious you can understand why Snow’s father would fall for her. The book toys with the notion that the man is bewitched rather than acting of his own accord, but it never gives you an answer to that question one way or another.

Lest we forget, the city itself is also a character. Having lived in NYC for eleven years, I’ve always been very touchy about how it’s portrayed in books for kids. When contemporary books are filled with alleyways it makes me mighty suspicious. Old timey fare gets a pass, though. Clever too of Phelan to set the book during the winter months. As Snow says at one point, “snow covers everything and makes the entire world beautiful . . . This city is beautiful, too. It has its own magic.” So we get Art Deco interiors, and snow covered city tops seen out of huge plate glass windows. We get theaters full of gilt and splendor and the poverty of Hoovervilles in the park, burning trashcans and all. It felt good. It felt right. It felt authentic. I could live there again.

Lest we forget, the city itself is also a character. Having lived in NYC for eleven years, I’ve always been very touchy about how it’s portrayed in books for kids. When contemporary books are filled with alleyways it makes me mighty suspicious. Old timey fare gets a pass, though. Clever too of Phelan to set the book during the winter months. As Snow says at one point, “snow covers everything and makes the entire world beautiful . . . This city is beautiful, too. It has its own magic.” So we get Art Deco interiors, and snow covered city tops seen out of huge plate glass windows. We get theaters full of gilt and splendor and the poverty of Hoovervilles in the park, burning trashcans and all. It felt good. It felt right. It felt authentic. I could live there again.

We live in a blessed time for graphic novels. With the recent win of what may well be the first graphic novel to win a National Book Award, they are respected, flourishing, and widely read. Yet for all that, the graphic novels written for children are not always particularly beautiful to the eye. Aesthetics take time. A beautiful comic is also a lot more time consuming than one done freehand in Photoshop. All the more true if that comic has been done almost entirely in watercolors as Phelan has here. I don’t think that there’s a soul alive who could pick up this book and not find it beautiful. What’s interesting is how Phelan balances the Art Deco motifs with the noir-ish scenes and shots. When we think of noir graphic novels we tend to think of those intensely violent and very adult classics like Sin City. Middle grade noir is almost unheard of at this point. Here, the noir is in the tone and feel of the story. It’s far more than just the black and white images, though those help too in their way.

The limited color palette, similar in many ways to The Storm in the Barn with how it uses color, here invokes the movies of the past. He always has a reason, that Matt Phelan. His judicious use of color is sparing and soaked with meaning. The drops of blood, often referred to in the original fairytale as having sprung from the queen’s finger when she pricked herself while sewing, is re-imagined as drops of bright red blood on a handkerchief and the pure white snow, a sure sign of influenza. Red can be lips or an apple or cheeks in the cold. Phelan draws scenes in blue or brown or black and white to indicate when you’re watching a memory or a different moment in time, and it’s very effective and easy to follow. And then there’s the last scene, done entirely in warm, gentle, full-color watercolors. It does the heart good to see.

The limited color palette, similar in many ways to The Storm in the Barn with how it uses color, here invokes the movies of the past. He always has a reason, that Matt Phelan. His judicious use of color is sparing and soaked with meaning. The drops of blood, often referred to in the original fairytale as having sprung from the queen’s finger when she pricked herself while sewing, is re-imagined as drops of bright red blood on a handkerchief and the pure white snow, a sure sign of influenza. Red can be lips or an apple or cheeks in the cold. Phelan draws scenes in blue or brown or black and white to indicate when you’re watching a memory or a different moment in time, and it’s very effective and easy to follow. And then there’s the last scene, done entirely in warm, gentle, full-color watercolors. It does the heart good to see.

The thing about Matt Phelan is that he rarely does the same story twice. About the only thing you can count on with him is that he loves history and the past. Indeed, between showing off a young Buster Keaton ( Bluffton) and a ravaged Dust Bowl setting (The Storm in the Barn) it’s possible “Snow White” is just an extension of his favorite era. As much a paean to movies as it is fairytales and graphic novels, Phelan limits his word count and pulls off a tale with truly striking visuals and killer emotional resonance. I don’t think I’ve ever actually enjoyed the story of Snow White until now. Hand this book to graphic novel fans, fairytale fans, and any kid who’s keen on good triumphing over evil. There might be one or two such children out there. This book is for them.

On shelves now.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 11/13/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

middle grade historical fantasy,

Kate Saunders,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 imports,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 middle grade fantasy,

2016 middle grade historical fiction,

Reviews,

middle grade fantasy,

Random House,

Best Books,

Delacorte Press,

WWI,

middle grade historical fiction,

Add a tag

Five Children on the Western Front

Five Children on the Western Front

By Kate Saunders

Delacorte Press (an imprint of Random House)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-553-49793-9

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

Anytime someone writes a new prequel or sequel to an old children’s literary classic, the first question you have to ask is, “Was this necessary?” And nine times out of ten, the answer is a resounding no. No, we need no further adventures in the 100-Acre Woods. No, there’s very little reason to speculate on precisely what happened to Anne before she got to Green Gables. But once in a while an author gets it right. If they’re good they’ll offer food for thought, as when Jacqueline Kelly wrote, Return to the Willows (the sequel to The Wind in the Willows) and Geraldine McCaughrean wrote Peter Pan in Scarlet. And if they’re particularly talented, then they’ll do the series one better. They’ll go and make it smart and pertinent and real and wonderful. They may even improve upon the original. The idea that someone would write a sequel to Five Children and It (and to a lesser extent The Phoenix and the Carpet and The Story of the Amulet) is well-nigh short of ridiculous. I mean, you could do it, sure, but why? What’s the point? Well, as author Kate Saunders says of Nesbit’s classic, “Bookish nerd that I was, it didn’t take me long to work out that two of E. Nesbit’s fictional boys were of exactly the right ages to end up being killed in the trenches…” The trenches of WWI, that is. Suddenly we’ve an author who dares to meld the light-hearted fantasy of Nesbit’s classic with the sheer gut-wrenching horror of The War to End All Wars. The crazy thing is, she not only pulls it off but she creates a great novel in the process. One that deserves to be shelved alongside Nesbit’s original for all time.

Once upon a time, five children found a Psammead, or sand fairy, in their back garden. Nine years later, he came back. A lot has happened since this magical, and incredibly grumpy, friend was in the children’s lives. The world stands poised on the brink of WWI. The older children (Cyril, Anthea, Robert, and Jane) have all become teenagers, while the younger kids (Lamb and newcomer Polly) are the perfect age to better get to know the old creature’s heart. As turns out, he has none, or very little to speak of. Long ago, in ancient times, he was worshipped as a god. Now the chickens have come home to roost and he must repent for his past sins or find himself stuck in a world without his magic anymore. And the children? No magic will save them from what’s about to come.

A sequel to a book published more than a hundred years ago is a bit more of a challenge than writing one published, say, fifty. The language is archaic, the ideas outdated, and then there’s the whole racism problem. But even worse is the fact that often you’ll find character development in classic titles isn’t what it is today. On the one hand that can be freeing. The author is allowed to read into someone else’s characters and present them with the necessary complexity they weren’t originally allowed. But it can hem you in as well. These aren’t really your characters, after all. Clever then of Ms. Saunders to age the Lamb and give him a younger sister. The older children are all adolescents or young adults and, by sheer necessity, dull by dint of age. Even so, Saunders does a good job of fleshing them out enough that you begin to get a little sick in the stomach wondering who will live and who will die.

This naturally begs the question of whether or not you would have to read Five Children and It to enjoy this book. I think I did read it a long time ago but all I could really recall was that there were a bunch of kids, the Psammead granted wishes, the book helped inspire the work of Edgar Eager, and the youngest child was called “The Lamb”. Saunders tries to play the book both ways then. She puts in enough details from the previous books in the series to gratify the Nesbit fans of the world (few though they might be) while also catching the reader up on everything that came before in a bright, brisk manner. You do read the book feeling like not knowing Five Children and It is a big gaping gap in your knowledge, but that feeling passes as you get deeper and deeper into the book.

One particular element that Ms. Saunders struggles with the most is the character of the Psammead. To take any magical creature from a 1902 classic and to give him hopes and fears and motivations above and beyond that of a mere literary device is a bit of a risk. As I’ve mentioned, I’ve not read “Five Children and It” in a number of years so I can’t recall if the Psammead was always a deposed god from ancient times or if that was entirely a product from the brain of Ms. Saunders. Interestingly, the author makes a very strong attempt at equating the atrocities of the Psammead’s past (which are always told in retrospect and are never seen firsthand) with the atrocities being committed as part of the war. For example, at one point the Psammead is taken to the future to speak at length with the deposed Kaiser, and the two find they have a lot in common. It is probably the sole element of the book that didn’t quite work for me then. Some of the Psammead’s past acts are quite horrific, and he seems pretty adamantly disinclined to indulge in any serious self-examination. Therefore his conversion at the end of the book didn’t feel quite earned. It’s foolish to wish a 250 page children’s novel to be longer, but I believe just one additional chapter or two could have gone a long way towards making the sand fairy’s change of heart more realistic. Or, at the very least, comprehensible.

When Ms. Saunders figured out the Cyril and Robert were bound for the trenches, she had a heavy task set before her. On the one hand, she was obligated to write with very much the same light-hearted tone of the original series. On the other hand, the looming shadow of WWI couldn’t be downplayed. The solution was to experience the war in much the same way as the characters. They joke about how short their time in the battle will be, and then as the book goes along the darkness creeps into everyday life. One of the best moments, however, comes right at the beginning. The children, young in the previous book, take a trip from 1905 to 1930, visit with their friend the professor, and return back to their current year. Anthea then makes an off-handed comment that when she looked at the photos on the wall she saw plenty of ladies who looked like young versions of their mother but she couldn’t find the boys. It simply says after that, “Far away in 1930, in his empty room, the old professor was crying.”

So do kids need to have read Five Children and It to enjoy this book? I don’t think so, honestly. Saunders recaps the originals pretty well, and I can’t help but have high hopes for the fact that it may even encourage some kids to seek out the originals. I do meet kids from time to time that are on the lookout for historical fantasies, and this certainly fits the bill. Ditto kids with an interest in WWI and (though this will be less common as the years go by) kids who love Downton Abbey. It would be remarkably good for them. Confronting issues of class, disillusion, meaningless war, and empathy, the book transcends its source material and is all the better for it. A beautiful little risk that paid off swimmingly in the end. Make an effort to seek it out.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Other Blog Reviews: educating alice

Professional Reviews:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 11/3/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Mo Willems,

Reviews,

Hyperion,

Best Books,

Dan Santat,

easy books,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

Disney - Hyperion,

Add a tag

The Cookie Fiasco

The Cookie Fiasco

By Dan Santat

Additional Art by Mo Willems

Hyperion Books for Children (an imprint of Disney)

$9.99

ISBN: 978-1484726365

Ages 3-6

On shelves now

See, this is tricky. Very tricky indeed. On the one hand, as a reviewer of children’s books, not bound to any single periodical, I have the freedom to select any book I wish. As such, I like to highlight books that haven’t gotten a lot of attention. Imports, books from small presses, books that get lost in the ginormous publishing cycle each year, etc. It gives me a little kick. This isn’t to say I won’t review a bestseller, but what’s the point? The book gets lots of lovely money and doesn’t need my help. And though I absolutely adored the new easy book The Cookie Fiasco (part of the new Mo Willems “Elephant & Piggie Like Reading” series) I could see it sitting deservedly on the top of the New York Times bestseller list, as is right. A job well done then? Not quite. I made the mistake of reading some of the professional reviews of this book. Reviews that clearly had it in for this title from the start and failed to take into account what Dan Santat has managed to pull off here. It’s not just the art (which is far more complex than an initial reading yields). It’s not just the fact that it’s a brilliant story told in an easy book format with limited words. It’s not just the fact that it’s also a story about MATH (and why is it that no one is complimenting this book enough on that score?). It’s the fact that all these elements are combined together to make what I can honestly say is one of the best books of the year. Clever, funny, beautiful to look at, and an easy book that is actually easy (not a given), don’t pooh-pooh this one for its popularity. Take a moment instead to savor what Santat’s accomplished here. I like reviewing the underdogs, but sometimes the top dog IS the underdog. To prove it, I give you Example A: The Cookie Fiasco.

Three friends. Four cookies. It’s a conundrum, to say the least. When two squirrels, a hippo, and a crocodile find themselves with an insufficient number of snacks they attempt to solve the problem in a number of different ways. Perhaps someone will not get a cookie? Impossible! “We need equal cookies for all!” Could two people share one cookie together? Unfair idea. Do crocodiles actually like cookies? They do. Should they share by size? Unfair when you’ve a hippo for a friend. As the tension increases, the hippo finds the best way to relieve stress is to break the cookies into halves. Next thing you know there are twelve pieces. That means each person gets three apiece! Problem solved! Now about those three glasses of milk . . .

How would you definite a fiasco? In one of my favorite episodes of This American Life (titled, appropriately enough, “Fiasco!”) they defined the word as, “when something simple and small turns horribly large”. I don’t think you can truly appreciate this concept unless you have children. No one quite like a small, young person can take a basic idea like, say, eating banana slices rather than a whole banana before bed, and turn it into WWIII, complete with tears, mess, unearthly cries, and parents that vow they will never slice another banana again as long the world does turn. Children begat chaos and, as such, children LOVE controlled chaos. The kind of chaos that ultimately gets cleaned up by grown-ups in the end. Recently I’ve been noticing how it’s used in books more and more. Whether it’s the aquatic antics of Curious George Gets a Medal, the joyous free-for-all of I Ain’t Gonna Paint No More or what I consider to be the most absolutely insane, grotesque, explosion of the id upon the page, A Day at the Firehouse by Richard Scarry (seriously, you have to check it out), I love me a good jaunt through the wild side. Santat taps into this snowball effect all too well. The “fiasco” of this book sounds tame (the gentle breaking apart of the cookies) but like my 2-year-old son, the characters in this book react as if the hippo were snapping the very tendons of their limbs. It’s a gentle reminder that for kids, sometimes the greatest fiasco comes in bite-sized pieces.

Let it never be said that I am a librarian that cares about leveling. Lexile, Fountas and Pinnell, you name it, it’s not my cup of tea. As a public librarian I don’t really have to care, though. That’s my prerogative. Now I will freely admit that for an easy book The Cookie Fiasco has some slightly more complex words. Heck, the word “fiasco” is even in the title. That said, I really and truly believe that Santat did a stand up and cheer job with keeping the text on the simple side. My five-year-old is currently learning to read and doesn’t have an overt amount of difficulty getting through this text. Extra Added Bonus: The overly dramatic moments allow her to rage against the heavens with drama inflected voices. A nice plus.

You don’t need to teach your five-year-old fractions, you know. You’re not going to fail the Parent of the Year awards if you prefer to wait until the kid is a little older to bring them up. It’s fine. But by the same token, there’s nothing out there saying that you can’t be sneaky about them. The fact that the solution to everyone’s problems is fraction-based is notable. I try to read as many math books for kids published in a given year as possible and let me tell you, it’s not easy to find them. The thing about The Cookie Fiasco, though, is that it’s not promoting itself as a math book in any way, shape, or form. Santat just works it oh-so-casually into the text so that by the time you stumble upon it you’re caught off-guard. And hey, if you happen to mention that these are fractions to a kid, and then show what you mean with some additional information . . . well, that’s just your prerogative, isn’t it? Clever parent.

So I’m talking to a friend the other day and the subject of this book comes up. “Do you think it could be a Caldecott winner?” they asked me. I was stunned. Under normal circumstances easy books do not win Caldecotts. It’s not unheard of for them to garner awards above and beyond the Geisel (see: Frog and Toad Together which won a Newbery) but nobody usually puts enough work into the art of an easy book to even start the discussion. Yet after my friend mentioned this possibility to me, I began to remember what Santat did with The Cookie Fiasco. A sane man would have just slapped together some pictures, grabbed his paycheck, and skedaddled. Santat, on the other hand, went a little crazy. He decided that the wisest course of action was to create teeny tiny multi-colored models of the heads of all his characters. That way, when they imagine different solutions to their cookie problem, the heads will indicate that this an idea and not what’s actually happening. Now look closely at those models. Even when they look simple, Santat’s obviously been thinking about them. For example, when the hippo suggests that the squirrels share a cookie together, the accompanying model is of a single squirrel body with a heads of the two characters attached. Did you notice that the heads are red and blue but that the body is purple? Love that attention to detail there. I also started paying attention to repetition in facial expressions. Insofar as I can tell, Dan never has the exact same facial expression on a character appear on its model version twice in a row. Either the mouth is slightly open or the eyes are looking in a different direction. Remarkable.

And now, an ode to good speech balloons. It is not a commonly known fact, but speech balloons can make or break a book. Done poorly, as they often are, they make good books bad. They draw attention to themselves and not to the action on the page. You might think that since Santat is constantly mucking with the font sizes and sometimes the fonts themselves in this book, that is a bad thing. You would be wrong. The placement of these speech balloons is superb. There is never a moment a parent, whether or not they’ve ever read a speech balloon a day in their life, will get confused about the order of who speaks when. Which, when you think about it, really is a speech balloon’s sole job anyway.

Finally . . . what I didn’t like about the book: The female squirrel’s ponytails. Seemed superfluous. They come right out. That’s about it.

As I mentioned before, book doesn’t need me to review it. It’s been on the New York Times bestseller list and will certainly garner a Geisel Award if there is any justice in the universe. It has sold mad bank and will continue to sell well into the future. That said, I feel a need to defend its honor. This isn’t some random title in a popular series. If it came out without the name “Mo Willems” anywhere in sight I bet it would STILL be a massive hit. It has humor and fractions and killer art, and all sorts of things going for it. I review very few easy books, and even fewer popular easy books, in a given year, but I can always make exceptions. And this book, put plainly, is exceptional. Top notch stuff all around.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 10/27/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

nonfiction picture books,

Feiwel and Friends,

macmillan,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 nonfiction picture books,

Jonathan Tweet,

Karen Lewis,

Add a tag

Grandmother Fish: A Child’s First Book of Evolution

Grandmother Fish: A Child’s First Book of Evolution

By Jonathan Tweet

Illustrated by Karen Lewis

Feiwel and Friends (an imprint of Macmillan)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-1250113238

Ages 3-6

On shelves now

Travel back with me through the Earth’s history, back into the farthest reaches of time when the sand we walk today was still rock and the oceans of an entirely salination. Back back back we go to, oh about 13 years ago, I’d say. I was a library grad student, and had just come to the shocking realization that the children’s literature class I’d taken on a lark might actually yield a career of some sort. We were learning the finer points of book reviewing (hat tip to K.T. Horning’s From Cover to Cover there) and to hone our skills each of us was handed a brand new children’s book, ready for review. I was handed Our Family Tree: An Evolution Story by Lisa Westberg Peters, illustrated by Lauren Stringer. It was good, so I came up with some kind of a review. It was, now that I think about it, the very first children’s book review I ever wrote (talk about evolution). And I remember at the time thinking (A) How great it was to read a picture book on the topic and (B) That with my limited knowledge of the field there were probably loads and loads of books out there about evolution for small children. Fun Fact: There aren’t. Actually, in the thirteen years between then and now I’ve not seen a single evolution themed picture book come out since the Peters/Stringer collaboration. Until now. Because apparently two years before I ran across Our Family Tree author Jonathan Tweet was trying to figure out why there were so few books on the subject on the market. It took him a while, but he finally got his thoughts in order and wrote this book. Worth the wait and possibly the only book we may need on the subject. For a while, anyway.

Let’s start with a fish. We’ll call her Grandmother Fish and she lived “a long, long, long, long, long time ago.” She did familiar fishy things like “wiggle” and “chomp”. And then she had ancestors and they turned out to be everything from sharks to ray-finned fish to reptiles. That’s when you meet Grandmother Reptile, who lived “a long, long, long, long time ago.” From reptiles we get to mammals. From mammals to apes. And from apes to humans. And with each successive iteration, they carry with them the traits of their previous forms. Remember how Grandmother Fish could wiggle and chomp? Well, so can every subsequent ancestor, with some additional features as well. The final image in the book shows a wide range of humans and they can do the things mentioned in the book before. Backmatter includes a more complex evolutionary family tree, a note on how to use this book, a portion “Explaining Concepts of Evolution”, a guide “to the Grandmothers, Their Actions, and Their Grandchildren for your own information to help you explain evolution to your child”, and finally a portion on “Correcting Common Errors” (useful for both adults and kids).

What are the forbidden topics of children’s literature? Which is to say, what are the topics that could be rendered appropriate for kids but for one reason or another never see the light of day? I can think of a couple off the top of my head, an evolution might be one of them. To say that it’s controversial in this, the 21st century, is a bit odd, but we live in odd times. No doubt the book’s creators have already received their own fair share of hate mail from folks who believe this content is inappropriate for their children. I wouldn’t be too surprised to hear that it ended up on ALA’s Most Challenged list of books in the future. Yet, as I mentioned before, finding ANY book on this subject, particularly on the young end of the scale, is near impossible. I am pleased that this book is filling such a huge gap in our library collections. Now if someone would just do something for the 7-12 year olds . . .

What are the forbidden topics of children’s literature? Which is to say, what are the topics that could be rendered appropriate for kids but for one reason or another never see the light of day? I can think of a couple off the top of my head, an evolution might be one of them. To say that it’s controversial in this, the 21st century, is a bit odd, but we live in odd times. No doubt the book’s creators have already received their own fair share of hate mail from folks who believe this content is inappropriate for their children. I wouldn’t be too surprised to hear that it ended up on ALA’s Most Challenged list of books in the future. Yet, as I mentioned before, finding ANY book on this subject, particularly on the young end of the scale, is near impossible. I am pleased that this book is filling such a huge gap in our library collections. Now if someone would just do something for the 7-12 year olds . . .

When you are simplifying a topic for children, one of the first things you need to figure out from the get-go is how young you want to go. Are you aiming your book at savvy 6-year-olds or bright-eyed and bushy-tailed 3-year-olds? In the case of Grandmother Fish the back-story to the book is that creator Jonathan Tweet was inspired to write it when he couldn’t find a book for his daughter on evolution. We will have to assume that his daughter was on the young end of things since the final product is very clearly geared towards the interactive picture book crowd. Readers are encouraged to wiggle, crawl, breathe, etc. and the words proved capable of interesting both my 2-year-old son and my 5-year-old daughter. One would not know from this book that the author hadn’t penned picture books for kids before. The gentle repetition and clincher of a conclusion suggest otherwise.

One problem with turning evolution into picture book fare is the danger of confusing the kids (of any age, really). If you play it that our ancestors were monkeys, then some folks might take you seriously. That’s where the branching of the tree becomes so interesting. Tweet and Lewis try hard to make it clear that though we might call a critter “grandmother” it’s not literally that kind of a thing. The problem is that because the text is so simple, it really does say that each creature had “many kinds of grandchildren.” Explaining to kids that this is a metaphor and not literal . . . well, good luck with that. You may find yourself leaning heavily on the “Correcting Common Errors” page at the end of the book, which aims to correct common misconceptions. There you will find gentle corrections to false statements like “We started as fish” or “Evolution progresses to the human form” or “We descended from one fish or pair of fish, or one early human or pair of early humans.” Of these Common Errors, my favorite was “Evolution only adds traits” since it was followed by the intriguing corrective, “Evolution also take traits away. Whales can’t crawl even though they’re descended from mammals that could.” Let’s talk about the bone structure of the dolphin’s flipper sometime, shall we? The accompanying “Explaining Concepts of Evolution” does a nice job of helping adults break down ideas like “Natural Selection” and “Artificial Selection” and “Descent with Modification” into concepts for young kids. Backmatter-wise, I’d give the book an A+. In terms of the story itself, however, I’m going with a B. After all, it’s not like every parent and educator that reads this book to kids is even going to get to the backmatter. I understand the decisions that led them to say that each “Grandmother” had “grandchildren” but surely there was another way of phrasing it.

This isn’t the first crowd-sourced picture book I’ve ever seen, but it may be one of the most successful. The reason is partly because of the subject matter, partly because of the writing, and mostly because of the art. Bad art sinks even the most well-intentioned of picture books out there. Now I don’t know the back-story behind why Tweet paired with illustrator Karen Lewis on this book, but I hope he counts his lucky stars every day for her participation. First and foremost, he got an illustrator who had done books for children before (Arturo and the Navidad Birds probably being her best known). Second, her combination of watercolors and digital art really causes the pages to pop. The colors in particular are remarkably vibrant. It’s a pleasure to watch them, whether close up for one-on-one readings, or from a distance for groups. Whether on her own or with Tweet’s collaboration, her clear depictions of the evolutionary “tree” is nice and fun. Plus, it’s nice to see some early humans who aren’t your stereotypical white cavemen with clubs, for once.

This isn’t the first crowd-sourced picture book I’ve ever seen, but it may be one of the most successful. The reason is partly because of the subject matter, partly because of the writing, and mostly because of the art. Bad art sinks even the most well-intentioned of picture books out there. Now I don’t know the back-story behind why Tweet paired with illustrator Karen Lewis on this book, but I hope he counts his lucky stars every day for her participation. First and foremost, he got an illustrator who had done books for children before (Arturo and the Navidad Birds probably being her best known). Second, her combination of watercolors and digital art really causes the pages to pop. The colors in particular are remarkably vibrant. It’s a pleasure to watch them, whether close up for one-on-one readings, or from a distance for groups. Whether on her own or with Tweet’s collaboration, her clear depictions of the evolutionary “tree” is nice and fun. Plus, it’s nice to see some early humans who aren’t your stereotypical white cavemen with clubs, for once.

I look at this book and I wonder what its future holds. Will a fair number of public school libraries purchase it? They should. Will parents like Mr. Tweet be able to find it when they wander aimlessly into bookstores and libraries? One can hope. And is it any good? It is. But you only have my word on that one. Still, if great grand numbers of perfect strangers can band together to bring a book to life on a topic crying out for representation on our children’s shelves, you’ve gotta figure the author and illustrator are doing something right. A book that meets and then exceeds expectations, tackling a tricky subject, in a divisive era of our history, to the betterment of all. Not too shabby for a fish.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 10/18/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

international children's books,

Juana Medina,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 early chapter books,

Reviews,

Best Books,

Candlewick,

Latino children's books,

early chapter books,

Add a tag

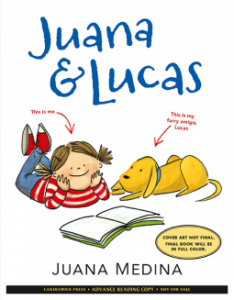

Juana and Lucas

Juana and Lucas

By Juana Medina

Candlewick Press

$14.99

ISBN: 978-1-7636-7208-9

Ages 6-9

On shelves now

Windows. Mirrors. Mirrors. Windows. Windowy mirrors. Mirrory windows. Windows. Mirrors. Sliding doors! Mirrors. Windows.

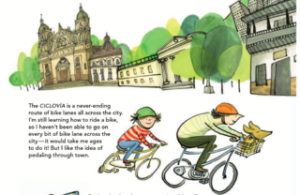

In the world of 21st century children’s literature, diversity should be the name of the game. We want books for our children that reflect the worlds they know and the worlds they have yet to greet. We want them to see themselves in their books (mirrors), see others unlike themselves (windows), and have a way to get from one place to another (sliding doors). To accomplish this, all you have to do is publish a whole bunch of books about kids of different races, religions, abilities, persuasions, you name it. Great strides have been made over the last few years in the general consciousness of the publishing industry (the publishers, the librarians, the teachers, and even the parents) even as teeny tiny, itty bitty, itsy bitsy tiptoes have been made in terms of what actually is getting published. Much of the credit for spearheading efforts to bring to light more and more books for all children can be given to the We Need Diverse Books movement. That said, our children’s rooms are still filled with monumental gaps. Contemporary Jewish characters are rare. Muslim characters rarer still. And don’t even TALK to me about the state of kids in wheelchairs these days. Interestingly enough, the area where diversity has increased the most is in early chapter books. Whether it’s Anna Hibiscus, Lola Levine, Alvin Ho, or any of the other new and interesting characters out there, there is comfort to be found in those books that transition children from easy readers to full-blown novels. Into this world comes Juana Medina and her semi-autobiographical series Juana & Lucas. Short chapters meet universal headaches (with details only available in Bogota, Colombia) ultimately combining to bring us a gal who will strike you as both remarkably familiar and bracingly original.

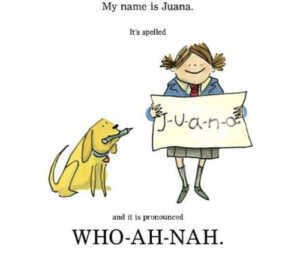

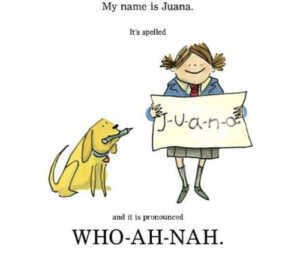

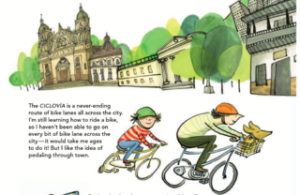

You might think that Juana has it pretty good, and for the most part you’d be right. She lives in Bogota, Colombia “the city that’s closest to my heart” with her Mami. She has a good furry best friend (her dog, Lucas) and a good not-so-furry best friend (Juli). And hey, it’s the first day of school! Cool, right? Only nothing goes the way Juana planned. The whole unfortunate day is capped off when one of her teachers informs the class that they will be learning “the English” this year. Could anything be more unfair? Yet as Juana searches for sympathy amongst her friends and relatives, she realizes that everyone seems to think that learning English is a good thing. Are they crazy? It isn’t until an opportunity comes up to visit somewhere fantastic, far away, and English speaking that she finally takes what everyone has told her to heart. In a big way.

You might think that Juana has it pretty good, and for the most part you’d be right. She lives in Bogota, Colombia “the city that’s closest to my heart” with her Mami. She has a good furry best friend (her dog, Lucas) and a good not-so-furry best friend (Juli). And hey, it’s the first day of school! Cool, right? Only nothing goes the way Juana planned. The whole unfortunate day is capped off when one of her teachers informs the class that they will be learning “the English” this year. Could anything be more unfair? Yet as Juana searches for sympathy amongst her friends and relatives, she realizes that everyone seems to think that learning English is a good thing. Are they crazy? It isn’t until an opportunity comes up to visit somewhere fantastic, far away, and English speaking that she finally takes what everyone has told her to heart. In a big way.

I love, first and foremost, the fact that the emotional crux of this book is fixated on Juana’s detestation of learning “the English”. Now already I’ve heard some commenters online complain that Juana’s problem isn’t something that English-speaking children will identify with. Bull. Any child that has ever learned to read will know where Juana is coming from. What English speaker would fail to sympathize when she asks, “Why are read and read written the same way but sound different? How can I know when people are talking about eyes or ice when they sound about the same? And what about left hand and left the room? So many words, so little sense”? Some kids reading this book may have experience learning another language too. For them, Juana’s complaints will ring true and clear. That’s a key aspect of her personality. She’s sympathetic, even when she’s whining.

For all that we’ve seen books like Juana’s, Lola Levine, Zapato Power, Pedro, First Grade Hero, Sophia Martinez, and a handful of others, interestingly this increase in Latino early chapter book is relatively recent. For a long time it was Zapato Power or nothing. The change is great, but it’s significant to note that all the books I’ve mentioned here are set in the United States. American books set in South American countries where the kids just live their daily lives and don’t have to deal with civil wars or invasions or coyotes or drug runners are difficult to find. What makes Juana and Lucas so unique is that it’s about a child living her life, having the kinds of problems that Ramona or Ruby Lu or Dyamonde Daniel could relate to. And like Anna Hibiscus or The Great Cake Mystery I love books for younger children that go through daily life in other present day countries. Windows indeed.

Early chapter books are interesting because publishers see them as far more series-driven than their writers might. An author can crank out title after title after title to feed the needs of their young readers, always assuming the demand is there, and they can do it easier with books under 100 pages than above. Juana could fit the bill in this regard. Her personality is likable, for starters. She’s not rude like Junie B. Jones or willfully headstrong in the same way as Ramona, but she does screw up. She does complain wildly. There are aspects of her personality you can identify with right from the start. I’d be pleased to see more of her in the future, and young readers will undoubtedly feel the same way. Plus, she has one particular feature that puts her heads and tails above a lot of the competition: She’s in color.

Early chapter books are interesting because publishers see them as far more series-driven than their writers might. An author can crank out title after title after title to feed the needs of their young readers, always assuming the demand is there, and they can do it easier with books under 100 pages than above. Juana could fit the bill in this regard. Her personality is likable, for starters. She’s not rude like Junie B. Jones or willfully headstrong in the same way as Ramona, but she does screw up. She does complain wildly. There are aspects of her personality you can identify with right from the start. I’d be pleased to see more of her in the future, and young readers will undoubtedly feel the same way. Plus, she has one particular feature that puts her heads and tails above a lot of the competition: She’s in color.

Created in ink and watercolor, Medina illustrates as well as writes her books. This art actually puts the book in a coveted place few titles can brag. You might ask if there’s a middle point between easy books and, say, Magic Tree House titles. I’d say this book was it. Containing a multitude of full-color pictures and spreads, it offers kids the comfort of picture books with the sensibility and sophistication of chapter book literature. And since she’s already got the art in place, why not work in some snazzy typography as well? Medina will often integrate individual words into the art. They swoop and soar around the characters, increasing and decreasing in size, according to their wont. Periodically a character will be pulled out and surrounded by fun little descriptor tidbits about their personage in a tiny font. Other times sentences move to imitate what their words say, like when Juana discusses how Escanilberto can kick the ball, “hard enough to send it across the field.” That sentence moves from his foot to a point just above his opponent’s head, the ball just out of reach. I like to think this radical wordplay plays into the early reader’s enjoyment of the book. It’s a lot more fun to read a chapter book when you have no idea what the words are going to pull on you next.

The writing is good, though the conclusion struck me as a bit rushed. Admittedly the solution to Juana’s problems is tied up pretty quickly. She won’t learn, she won’t learn, she won’t learn. She gets to have a prize? She studies and studies and studies. So rather than have her come to an understanding of English’s use on her own, an outside force (in this case, the promise of seeing Astroman) is the true impetus to her change. Sure, at the very end of the book she suddenly hits on the importance of learning other languages and visiting other places around the globe but it’s a bit after the fact. Not a big problem in the book, of course, but it would have been cool to have Juana come to this realization without outside influences.

The writing is good, though the conclusion struck me as a bit rushed. Admittedly the solution to Juana’s problems is tied up pretty quickly. She won’t learn, she won’t learn, she won’t learn. She gets to have a prize? She studies and studies and studies. So rather than have her come to an understanding of English’s use on her own, an outside force (in this case, the promise of seeing Astroman) is the true impetus to her change. Sure, at the very end of the book she suddenly hits on the importance of learning other languages and visiting other places around the globe but it’s a bit after the fact. Not a big problem in the book, of course, but it would have been cool to have Juana come to this realization without outside influences.

As nutty as it sounds, Juana and Lucas is a bit short on the “Lucas” side of that equation. Juana’s the true star of the show here, relegating man’s best friend to the sidelines. Fortunately, I have faith in this series. I have faith that it will return for future sequels and that when those sequels arrive they’ll have a storyline for Lucas to carry on his own. With Juana nearby, of course. After all, she belongs to the pantheon of strong female early chapter characters out there, ready to teach kids about life in contemporary Colombia even as she navigates her own trials and successes. And it’s funny. Did I mention it’s funny? You probably got that from context, but it bears saying. “Juana and Lucas” is the kind of book I’d like to see a lot more of. Let’s hope Ms. Medina is ready to spearhead a small revolution of early chapter book international diversity of her very own.

On shelves now.

Like This? Then Try:

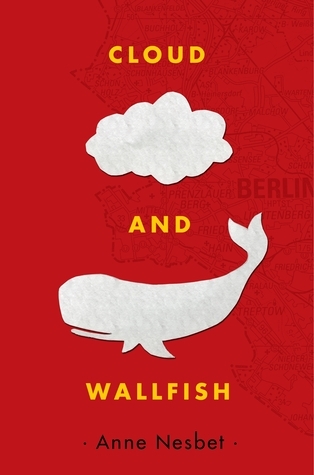

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 10/11/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

Best Books,

Anne Herbauts,

French children's books,

Enchanted Lion Books,

French picture books,

translated picture books,

international children's books,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 imports,

2016 picture books,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 translated children's books,

Add a tag

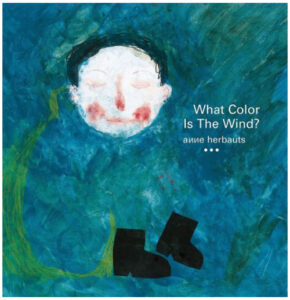

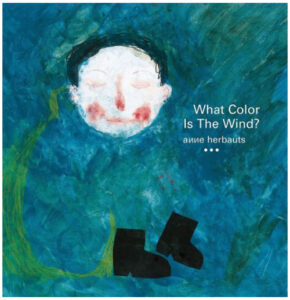

What Color Is the Wind?

What Color Is the Wind?

By Anne Herbauts

Translated by Claudia Zoe Bedrick

Enchanted Lion Books

$19.95

ISBN: 978-1-59270-221-3

Ages 5 and up

On shelves now

I’m going to have a hard time of it when my kids grow up. When I had them I swore up, down and sideways that I wouldn’t turn into the kind of blogger that declares that a book is good or bad, based solely on the whims of my impertinent offspring. For the most part, I’ve kept that promise. I review picture books outside of their influence, though I’m always interested in their opinions. Indeed, these opinions, and the sharp eyes that inform them, are sometimes not what I’d expect at all. So while I’ve never changed my opinion from liking a book to not liking it just because it didn’t suit my own particular kids’ tastes, I have admittedly found a new appreciation for other books when the children were able to spot things that I did not. What Color Is the Wind? is a pretty good example of this. I read the book at work, liked it fine, and brought it home for a possible review. My daughter then picked it up and proceeded to pretty much school me on what it contained, front to finish. Had I noticed the Braille on the cover? No. Did I see that the main character’s eyes are closed the whole time? No. How about the tactile pages? Did you notice that you can feel almost all of them? No. For a book that may look to some readers as too elegant and sophisticated to count as a favored bedtime story, think again. In this book Anne Herbauts proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that a distinct European style is engaging to American children when their parents give it half a chance. Particularly when tactile elements are involved.

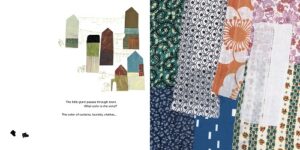

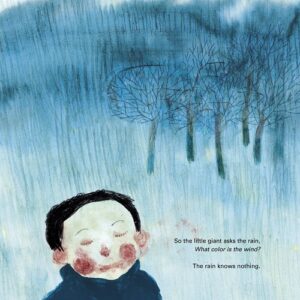

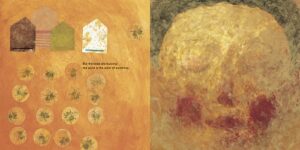

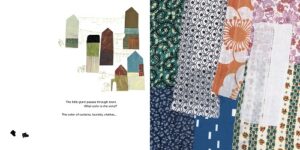

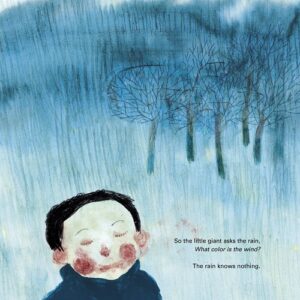

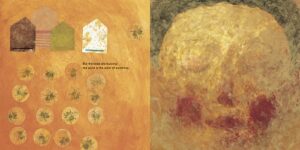

“We can’t see the wind, / we hear what it brings. / We can’t hear the wind, / we see what it brings.” The book begins with a question. A boy, his eyes closed, walks behind the cutout of a house. “What color is the wind? asks the little giant.” As he walks along, various plants, birds, animals, and inanimate objects offer answers. A wolf says the wind’s color is “the dark smell of the forest” while a window disagrees and says it’s “the color of time.” Everything that answers the little giant has a different feel on the page. The stream feels like consecutive ripples emanating from a dropped pebble, the roots of an apple tree like long, thin rivulets. At last the little giant encounters something that he senses is enormous. He asks his question and an enormous giant replies, “It is everything at once. This whole book.” He flips the book’s pages with his thumb so that they fly, and you the reader do the same, feeling the wind the book is capable of producing with its thick, lustrous pages. The color of the wind. The wind of this book.

“We can’t see the wind, / we hear what it brings. / We can’t hear the wind, / we see what it brings.” The book begins with a question. A boy, his eyes closed, walks behind the cutout of a house. “What color is the wind? asks the little giant.” As he walks along, various plants, birds, animals, and inanimate objects offer answers. A wolf says the wind’s color is “the dark smell of the forest” while a window disagrees and says it’s “the color of time.” Everything that answers the little giant has a different feel on the page. The stream feels like consecutive ripples emanating from a dropped pebble, the roots of an apple tree like long, thin rivulets. At last the little giant encounters something that he senses is enormous. He asks his question and an enormous giant replies, “It is everything at once. This whole book.” He flips the book’s pages with his thumb so that they fly, and you the reader do the same, feeling the wind the book is capable of producing with its thick, lustrous pages. The color of the wind. The wind of this book.

The Kirkus review journal said that this book was, “ ‘The blind men and the elephant’ reworked into a Zen koan” and then proceeded to recommend it for 9-11 year-olds and adults. I’m fairly certain I disagree with almost every part of that. Now here’s the funny part. I didn’t read this review before I read the book. I also didn’t read the press release that was sent to me with it. When I read a book I like to be surprised by it in some way. This is usually a good thing, but once in a while I can be a bit dense and miss the bigger picture. As I mentioned before, I completely missed the fact that this book was an answer to a blind child who had asked Anne Herbauts the titular question. I just thought it was cool that the book was so much fun to touch. Embossing, debossing, die-cuts, lamination, and all kinds of surfaces give the book the elements that make it really pop. As I read it in the lunchroom at work, my co-workers would peer over my shoulders to coo at what they saw. All well and good, but would a kid be interested too? Kirkus says they’d have to be at least nine to grasp its subtleties.

Obviously my 5-year-old daughter likes the book but she’s just one kid. She is not a representative for her species (so to speak). That said, this book just drills home the advantage that physical books have over their electronic counterparts: the sensation of touch. Play with a screen all day if you like, but you will never be able to move your fingers over these raised dots of rain or the rough bark of a tree’s trunk. As children become more immersed in the electronic, they become more enamored of tactile books. The sensation of paper on skin has yet to be replicated by our smooth as silk screens. And this will prove true with kids on the younger end of the scale. I’ll agree with Kirkus about the adult designation, though. When I worked for New York Public Library there was a group of special needs adults that would come in that were in need of tactile picture books. We would be asked if we had any on hand that we could hand over to them in some way. There were a few, but our holdings were pretty limited (though I do remember a particularly keen tactile version of The Very Hungry Caterpillar that proved to be a big hit). Those kids would have loved this book, but children of all ages, and all abilities, would feel the same way about it. Kids are never too old for tactile picture books. As such, you could use this book with Kindergartners as well as fifth graders. Little kids will like the fun pictures. Older kids may be inspired by the words as well.

Obviously my 5-year-old daughter likes the book but she’s just one kid. She is not a representative for her species (so to speak). That said, this book just drills home the advantage that physical books have over their electronic counterparts: the sensation of touch. Play with a screen all day if you like, but you will never be able to move your fingers over these raised dots of rain or the rough bark of a tree’s trunk. As children become more immersed in the electronic, they become more enamored of tactile books. The sensation of paper on skin has yet to be replicated by our smooth as silk screens. And this will prove true with kids on the younger end of the scale. I’ll agree with Kirkus about the adult designation, though. When I worked for New York Public Library there was a group of special needs adults that would come in that were in need of tactile picture books. We would be asked if we had any on hand that we could hand over to them in some way. There were a few, but our holdings were pretty limited (though I do remember a particularly keen tactile version of The Very Hungry Caterpillar that proved to be a big hit). Those kids would have loved this book, but children of all ages, and all abilities, would feel the same way about it. Kids are never too old for tactile picture books. As such, you could use this book with Kindergartners as well as fifth graders. Little kids will like the fun pictures. Older kids may be inspired by the words as well.

“Mom,” said my daughter as we went down the stairs for her post-reading, pre-brushing, nighttime snack. “Mom, you know the wind doesn’t have a color, right?” My child is a bit of a literalist. She’s the kid who knew early on that magic wasn’t real and once told me at the age of three that, “If ‘please’ is a magic word, it doesn’t exist.” So to read an entire book, based on the premise of seeing a color that couldn’t possibly be real, was a stretch for her. Remember, we read this entire book without really catching on that the little giant was blind. I countered that it was poetry, really. Colors were just as much about what they looked like as what they felt like. I asked her what blue made her feel, and red. Then I applied that to the emotions we feel about with the wind, which wasn’t really an analogy that held much water, but she was game to hear me out. “It’s poetry”, I said again. “Words that make you feel something when you read them.” So, as she had her snack, she had me read her some poetry. We’ve been reading poetry with her snack every night since. So for all that the book could be seen to be a straightforward picture book, to me it’s as much an introduction to poetry as anything else.

As for the art, I’ll admit that the combination of the style of art, the image on the cover, and the fact that the book is softcover and not hardcover (a cost-saving measure for what must be a very expensive title for Enchanted Lion Books to publish) did not immediately appeal to me. There’s no note to explain what the medium is and if I were to guess I’d say we were looking at crayons, mixed media, thick paints, colored pencils, ink blots, pen-and-inks, and more. Ironically, I really began to gravitate to the art when the little giant wasn’t stealing my focus. Nothing is intricately detailed, except perhaps the anatomy of honeybees or the raised and bumpy parts of the book. At the same time, for a book that celebrates touch, poetry, and physical sensation, the colors are often bright and lush. Whether it’s the blue watercolors of rain over trees or the hot orange that emanates from the page like a sun, Herbauts is simultaneously rendering illustrations obsolete with the unique format of What Color is the Wind? and celebrating their visual extremes.

I tend to give positive reviews to books that exceed my expectations. That’s just the nature of my occupation. And while I do believe that there are elements to this book that could be clearer or that there must have been a book jacket choice they could have chosen that was more appealing than the one you see here, otherwise I think this little book is a bit of a wonder. Deeply appealing to children of all ages, to say nothing of the adults out there, with so many uses, and so many applications. It reminds me of the old picture books by Bruno Munari that weren’t afraid to try new things with the picture book format. To get a little crazy. I don’t think we’ll suddenly see a big tactile picture book craze sweep the nation or anything, but maybe this book will inspire just one other publisher to try something a little different and to take a risk. Could be worth it. There’s nothing else like this book out there today. More’s the pity.

On shelves now.

Source: Final edition sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews:

Misc: A deeper look at some of the art over at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 10/5/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Misuzu Kaneko,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 poetry,

2016 picture book biographies,

David Jacobson,

Michiko Tsuboi,

Toshikado Hajiri,

Reviews,

poetry,

Best Books,

picture book biographies,

Sally Ito,

funny poetry,

middle grade poetry,

Add a tag

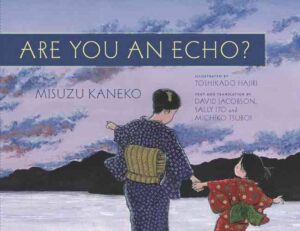

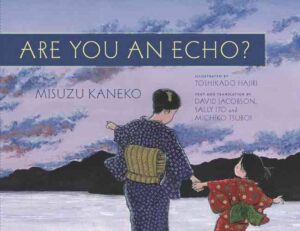

Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko

Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko

Narrative and Translation by David Jacobson, Sally Ito, and Michiko Tsuboi

Illustrated by Toshikado Hajiri

Chin Music Press

$19.50

ISBN: 9781634059626

Ages 5 and up

On shelves now

Recently I was at a conference celebrating the creators of different kinds of children’s books. During one of the panel discussions an author of a picture book biography of Fannie Lou Hamer said that part of the mission of children’s book authors is to break down “the canonical boundaries of biography”. I knew what she meant. A cursory glance at any school library or public library’s children’s room will show that most biographies go to pretty familiar names. It’s easy to forget how much we need biographies of interesting, obscure people who have done great things. Fortunately, at this conference, I had an ace up my sleeve. I knew perfectly well that one such book has just been published here in the States and it’s a game changer. Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko isn’t your typical dry as dust retelling of a life. It crackles with energy, mystery, tragedy, and, ultimately, redemption. This book doesn’t just break down the boundaries of biography. It breaks down the boundaries placed on children’s poetry, art, and translation too. Smarter and more beautiful than it has any right to be, this book challenges a variety of different biography/poetry conventions. The fact that it’s fun to read as well is just gravy.

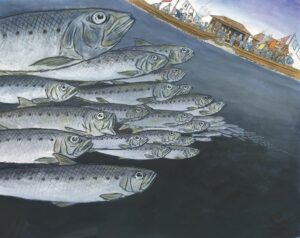

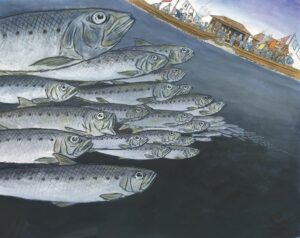

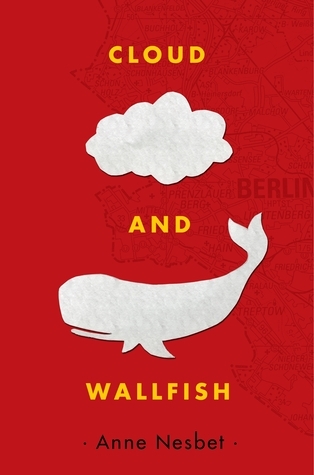

Part biography, part poetry collection, and part history, Are You an Echo? introduces readers to the life and work of celebrated Japanese poet Misuzu Kaneko. One day a man by the name of Setsuo Yazaki stumbled upon a poem called “Big Catch”. The poet’s seemingly effortless ability to empathize with the plight of fish inspired him to look into her other works. The problem? The only known book of her poems out there was caught in the conflagration following the firebombing of Tokyo during World War II. Still, Setsuo was determined and after sixteen years he located the poet’s younger brother who had her diaries, containing 512 of Misuzu’s poems. From this, Setsuo was able to piece together her life. Born in 1902, Misuzu Kaneko grew up in Senzaki in western Japan. She stayed in school at her mother’s insistence and worked in her mother’s bookstore. For fun she submitted some of her poems to a monthly magazine and shockingly every magazine she submitted them to accepted them. Yet all was not well for Misuzu. She had married poorly, contracted a disease from her unfaithful husband that caused her pain, and he had forced her to stop writing as well. Worst of all, when she threatened to leave he told her that their daughter’s custody would fall to him. Unable to see a way out of her problem, she ended her life at twenty-six, leaving her child in the care of her mother. Years passed, and the tsunami of 2011 took place. Misuzu’s poem “Are You an Echo?” was aired alongside public service announcements and it touched millions of people. Suddenly, Misuzu was the most famous children’s poet of Japan, giving people hope when they needed it. She will never be forgotten again. The book is spotted with ten poems throughout Misuzu’s story, and fifteen additional poems at the end.

There’s been a lot of talk in the children’s literature sphere about the role of picture book biographies. More specifically, what’s their purpose? Are they there simply to inform and delight or do they need to actually attempt to encapsulate the great moments in a person’s life, warts and all? If a picture book bio only selects a single moment out of someone’s life as a kind of example, can you still call it a biography? If you make up dialogue and imagine what might have happened in one scene or another, do those fictional elements keep it from the “Biography” section of your library or bookstore, or is there a place out there for fictionalized bios? These questions are new ones, just as the very existence of picture book biographies, in as great a quantity as we’re seeing them, is also new. One of the takeaways I’ve gotten from these conversations is that it is possible to tackle difficult subjects in a picture book bio, but it must be done naturally and for a good reason. So a story like Gary Golio’s Spirit Seeker can discuss John Coltrane’s drug abuse, as long as it serves the story and the character’s growth. On the flip side, Javaka Steptoe’s Radiant Child, a biography of Basquiat, makes the choice of discussing the artist’s mother’s fight with depression and mental illness, but eschews any mention of his own suicide.

There’s been a lot of talk in the children’s literature sphere about the role of picture book biographies. More specifically, what’s their purpose? Are they there simply to inform and delight or do they need to actually attempt to encapsulate the great moments in a person’s life, warts and all? If a picture book bio only selects a single moment out of someone’s life as a kind of example, can you still call it a biography? If you make up dialogue and imagine what might have happened in one scene or another, do those fictional elements keep it from the “Biography” section of your library or bookstore, or is there a place out there for fictionalized bios? These questions are new ones, just as the very existence of picture book biographies, in as great a quantity as we’re seeing them, is also new. One of the takeaways I’ve gotten from these conversations is that it is possible to tackle difficult subjects in a picture book bio, but it must be done naturally and for a good reason. So a story like Gary Golio’s Spirit Seeker can discuss John Coltrane’s drug abuse, as long as it serves the story and the character’s growth. On the flip side, Javaka Steptoe’s Radiant Child, a biography of Basquiat, makes the choice of discussing the artist’s mother’s fight with depression and mental illness, but eschews any mention of his own suicide.

Are You An Echo? is an interesting book to mention alongside these two other biographies because the story is partly about Misuzu Kaneko’s life, partly about how she was discovered as a poet, and partly a highlight of her poetry. But what author David Jacobson has opted to do here is tell the full story of her life. As such, this is one of the rare picture book bios I’ve seen to talk about suicide, and probably the only book of its kind I’ve ever seen to make even a passing reference to STDs. Both issues informed Kaneko’s life, depression, feelings of helplessness, and they contribute to her story. The STD is presented obliquely so that parents can choose or not choose to explain it to kids if they like. The suicide is less avoidable, so it’s told in a matter-of-fact manner that I really appreciated. Euphemisms, for the most part, are avoided. The text reads, “She was weak from illness and determined not to let her husband take their child. So she decided to end her life. She was only twenty-six years old.” That’s bleak but it tells you what you need to know and is honest to its subject.

But let’s just back up a second and acknowledge that this isn’t actually a picture book biography in the strictest sense of the term. Truthfully, this book is rife, RIFE, with poetry. As it turns out, it was the editorial decision to couple moments in Misuzu’s life with pertinent poems that gave the book its original feel. I’ve been wracking my brain, trying to come up with a picture book biography of a poet that has done anything similar. I know one must exist out there, but I was hard pressed to think of it. Maybe it’s done so rarely because the publishers are afraid of where the book might end up. Do you catalog this book as poetry or as biography? Heck, you could catalog it in the Japanese history section and still be right on in your assessment. It’s possible that a book that melds so many genres together could only have been published in the 21st century, when the influx of graphic inspired children’s literature has promulgated. Whatever the case, reading this book you’re struck with the strong conviction that the book is as good as it is precisely because of this melding of genres. To give up this aspect of the book would be to weaken it.

But let’s just back up a second and acknowledge that this isn’t actually a picture book biography in the strictest sense of the term. Truthfully, this book is rife, RIFE, with poetry. As it turns out, it was the editorial decision to couple moments in Misuzu’s life with pertinent poems that gave the book its original feel. I’ve been wracking my brain, trying to come up with a picture book biography of a poet that has done anything similar. I know one must exist out there, but I was hard pressed to think of it. Maybe it’s done so rarely because the publishers are afraid of where the book might end up. Do you catalog this book as poetry or as biography? Heck, you could catalog it in the Japanese history section and still be right on in your assessment. It’s possible that a book that melds so many genres together could only have been published in the 21st century, when the influx of graphic inspired children’s literature has promulgated. Whatever the case, reading this book you’re struck with the strong conviction that the book is as good as it is precisely because of this melding of genres. To give up this aspect of the book would be to weaken it.

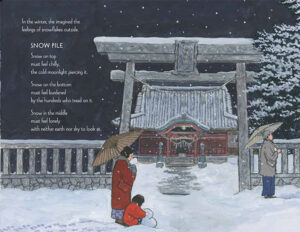

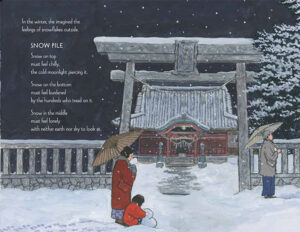

Right off the bat I was impressed by the choice of poems. The first one you encounter is called “Big Catch” and it tells about a village that has caught a great number of fish. The poem ends by saying, “On the beach, it’s like a festival / but in the sea they will hold funerals / for the tens of thousands dead.” The researcher Setsuo Yazaki was impressed by the poet’s empathy for the fish, and that empathy is repeated again and again in her poems. “Big Catch” is actually one of her bleaker works. Generally speaking, the poems look at the world through childlike eyes. “Wonder” contemplates small mysteries, in “Beautiful Town” the subject realizes that a memory isn’t from life but from a picture in a borrowed book, and “Snow Pile” contemplates how the snow on the bottom, the snow on the top, and the snow in the middle of a pile must feel when they’re all pressed together. The temptation would be to call Kaneko the Japanese Emily Dickenson, owing to the nature of the discovery of her poems posthumously, but that’s unfair to both Kaneko and Dickenson. Kenko’s poems are remarkable not just because of their original empathy, but also because they are singularly childlike. A kid would get a kick out of reading these poems. That’s no mean feat.

Mind you, we’re dealing with a translation here. And considering how beautifully these poems read, you might want a note from the translators talking about their process. You can imagine, then, how thrilled I was to find a half-page’s worth of a “Translators’ Note” explaining aspects of the work here that never would have occurred to me in a million years. The most interesting problem came down to culture. As Sally Ito and Michiko Tsuboi write, “In Japanese, girls have a particular way of speaking that is affectionate and endearing . . . However, English is limited in its capacity to convey Misuzu’s subtle feminine sensibility and the elegant nuances of her classical allusions. We therefore had to skillfully work our way through both languages, often producing several versions of a poem by discussing them on Skype and through extensive emails – Michiko from Japan, Sally from China – to arrive at the best possible translations in English.” It makes a reader really sit back and admire the sheer levels of dedication and hard work that go into a book of this sort. If you read this book and find that the poems strike you as singularly interesting and unique, you may now have to credit these dedicated translators as greatly as you do the original subject herself. We owe them a lot.

Mind you, we’re dealing with a translation here. And considering how beautifully these poems read, you might want a note from the translators talking about their process. You can imagine, then, how thrilled I was to find a half-page’s worth of a “Translators’ Note” explaining aspects of the work here that never would have occurred to me in a million years. The most interesting problem came down to culture. As Sally Ito and Michiko Tsuboi write, “In Japanese, girls have a particular way of speaking that is affectionate and endearing . . . However, English is limited in its capacity to convey Misuzu’s subtle feminine sensibility and the elegant nuances of her classical allusions. We therefore had to skillfully work our way through both languages, often producing several versions of a poem by discussing them on Skype and through extensive emails – Michiko from Japan, Sally from China – to arrive at the best possible translations in English.” It makes a reader really sit back and admire the sheer levels of dedication and hard work that go into a book of this sort. If you read this book and find that the poems strike you as singularly interesting and unique, you may now have to credit these dedicated translators as greatly as you do the original subject herself. We owe them a lot.

In the back of the book there is a note from the translators and a note from David Jacobson who wrote the text of the book that didn’t include the poetry. What’s conspicuously missing here is a note from the illustrator. That’s a real pity too since biographical information about artist Toshikado Hajiri is missing. Turns out, Toshikado is originally from Kyoto and now lives in Anan, Tokushima. Just a cursory glance at his art shows a mild manga influence. You can see it in the eyes of the characters and the ways in which Toshikado chooses to draw emotions. That said, this artist is capable of also conveying great and powerful moments of beauty in nature. The sunrise behind a beloved island, the crush of chaos following the tsunami, and a peach/coral/red sunset, with a grandmother and granddaughter silhouetted against its beauty. What Toshikado does here is match Misuzu’s poetry, note for note. The joyous moments she found in the world are conveyed visually, matching, if never exceeding or distracting from, her prowess. The end result is more moving than you might expect, particularly when he includes little human moments like Misuzu reading to her daughter on her lap or bathing her one last time.