new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: obituary, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 40

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: obituary in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Prince died Thursday, and I am sad. I've been asked to write about his death, but staring at the empty expanse beyond the flashing cursor, all I really know how to say is in the line above. Plenty of writers, more ably than I could, have written and spoken movingly about Prince since his death.

The post Prince and “the other Eighties” appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/12/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

obituary,

*Featured,

structuralism,

avant-garde music,

Pierre Boulez,

Jonathan Cross,

integral serialist music,

high modernist,

Music,

Add a tag

I’ve been very struck over the past couple of days listening to the testimony of so many musicians who worked with Pierre Boulez. They all seem to say the same thing. He had a phenomenal understanding of the music (his own and that of others), he had an extraordinary ear, and he was a joy to work with because he gave so much.

The post In memoriam: Pierre Boulez appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Yasmin Coonjah,

on 9/25/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

obituary,

choir,

cambridge,

*Featured,

Conducting,

Arts & Humanities,

Carols for Choirs,

choir music,

david wilcocks,

king's college,

music conductors,

Sir David Wilcocks,

Add a tag

Sir David Willcocks sadly passed away in September 2015. This is OUP’s tribute to a highly gifted musician and outstanding choral director whose leadership, decency, and humanity have inspired countless singers and conductors to try to follow his example.

The post Sir David Willcocks (1919-2015): an inspirational life remembered appeared first on OUPblog.

Gunther Schuller (1925-2015) was one of the most influential figures in the musical world of the past century, with a career that crossed and created numerous genres, fields, and institutions. Oxford offers heartfelt condolences to his family, and gratitude for the profound impact his work continues to have on music performance, study, and scholarship.

The post In memoriam: Gunther Schuller appeared first on OUPblog.

Fantasy author Sir Terry Pratchett has died. He was 66 years-old and suffered from early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

“It is with immeasurable sadness that we announce that author Sir Terry Pratchett has died,” reads a post on the author’s Facebook page. “The world has lost one of its brightest, sharpest minds. Rest in peace Sir Terry Pratchett.”

His Twitter page revealed the news through a series of cryptic messages.

Terry took Death’s arm and followed him through the doors and on to the black desert under the endless night.

— Terry Pratchett (@terryandrob) March 12, 2015

Pratchett was the author of more than 70 books including his most recent novel Discworld, which came out last July. He had collaborated with Neil Gaiman on Good Omens which was recently adapted as a six episode radio play on BBC Radio 4.

By: VictoriaD,

on 2/28/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Quincy Jones,

*Featured,

Arts & Humanities,

1960s girl pop,

1960s girlhood,

Alexandra Apolloni,

It's My Party,

Kathleen Hanna,

Lesley Gore,

You Don't Own Me,

Music,

feminism,

obituary,

activism,

Add a tag

In 2005, Ms magazine published a conversation between pop singer Lesley Gore and Kathleen Hanna of the bands Bikini Kill and Le Tigre. Hanna opened with a striking statement: “First time I heard your voice,” she said, “I went and bought everything of yours – trying to imitate you but find my own style.”

The post Rebel Girl: Lesley Gore’s voice appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press is saddened to report the passing of noted jazz scholar Lawrence Gushee on 6 January 2015. A Professor of Music at the University of Illinois for over 20 years, he held the title of Emeritus Professor of Music at Illinois since 1997. Originally specializing in medieval music, Dr. Gushee turned much of his attention to jazz during his time at Illinois, writing frequently on the history of black American jazz musicians. A prodigious researcher and eloquent writer, his contributions to research on the origins of jazz and its early period simply cannot be overstated. In particular, his 2005 book Pioneers of Jazz, which Oxford is incredibly proud to have published, was a landmark work in jazz history. Bringing to light the hitherto untold story of the early New Orleans jazz band the Creole Band, Gushee revealed how this almost entirely overlooked group played a pioneering role in introducing jazz to America, and bringing about the jazz phenomenon that swept the nation during the 1920s. While he will surely be missed by the jazz community, his contributions to the telling of its history will continue to be of immeasurable value to scholars, students, and fans of the music for generations to come. On behalf of OUP, I offer our deepest sympathies to his family during this difficult time.

The post In memoriam: Lawrence Gushee appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press is deeply saddened to report the passing of Juan Flores on 2 December 2014. Professor of Social and Cultural Analysis and director of Latino Studies at New York University, he was one of the foremost voices in Latino Studies and an exceptionally inspiring and generous writer, teacher, and colleague. His legacy is rich, with ten influential and award-winning books to his name and more on the way, and he had a passion and energy for his work that is rare and infectious. Through this work, Juan Flores will continue to bring understanding and insight to countless readers, students, and fellow scholars. I count myself fortunate to have had the opportunity to know and work with him as an author, and offer heartfelt condolences to his loved ones on this tragic loss.

The post In memoriam: Juan Flores appeared first on OUPblog.

By: LaurenH,

on 7/18/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

excerpt,

obituary,

musical theater,

*Featured,

Theatre & Dance,

Arts & Leisure,

Eddie Shapiro,

Nothing Like a Dame,

Elaine Stritch,

Add a tag

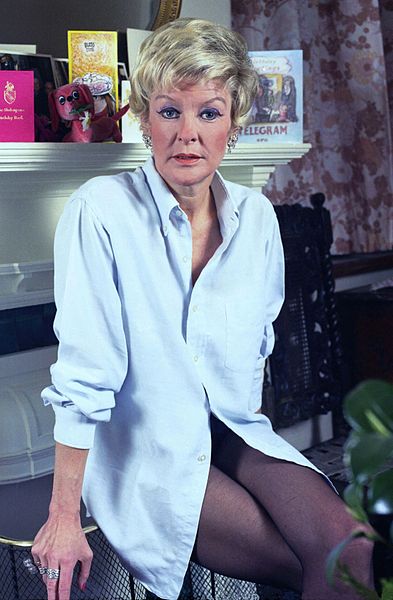

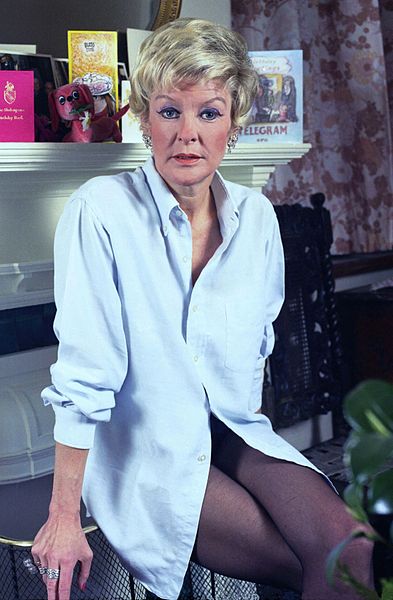

Oxford University Press is saddened to hear of the passing of Broadway legend Elaine Stritch. We’d like to present a brief extract from Eddie Shapiro’s interview with Elaine Stritch in November/December 2008 in Nothing Like a Dame that illustrates her tremendous life and vitality.

“What’s this all about, again?!” came Elaine Stritch’s unmistakable rattle of a voice, part Rosalind Russell, part dry martini, part cheese grater, on the other end of the phone. I was taken aback. After all, we had spoken the day before and the day before that. On the first call, she had told me that she was swamped but really wanted to get this interview out of the way. “Well,” I had offered, “there’s no great rush. I would rather you do this when you feel relaxed than when you are cramming it in.” “Don’t you worry about my disposition,” came the steely reply. “I’ll worry about my disposition.” She hated me, I thought, until the second call, during which she called me “dear” and apologized twice for her schedule. So now, on call number three, when it seemed we were back at square one, I didn’t know what to say. “Well, it’s the interview for my book, Nothing Like a Dame,” I explained. “You asked me to call today.” “And when did you want to do this,” came the deliberate reply. “Well, you asked me about today.” “Today? I can’t possibly do today.” “That’s fine. It’s just that when you called me on Friday, you said you wanted to get it done this weekend.” “I don’t recall saying that to anyone. Gee, Ed, I hate to leave you hanging like this. How about Thanksgiving?” “Thanksgiving Day?” “Yeah, before dinner. You could come for tea.” “That would be fine.” “But I tell you what, give me a call on Wednesday night after 11:00, just to confirm. And I promise I’ll remember.” And that is how I ended up having tea with irascible, cantankerous, outspoken, and utterly charming Elaine Stritch at The Carlyle Hotel on Thanksgiving Day.

Elaine Stritch was born outside of Detroit in 1925. She came to New York to study under Erwin Piscator at The New School, where her classmates included Marlon Brando and Bea Arthur (with whom she’d compete for a Tony Award sixty years later. And win.). She made her musical debut in Angel in the Wings, singing the absurd “Bongo, Bongo, Bongo (I Don’t Want to Leave the Congo)” before her long run as Ethel Merman’s understudy in Call Me Madam. Since Merman never missed a performance, Stritch never went on, and felt safe simultaneously taking a one-scene part in the hit 1952 revival of Pal Joey a block away. “I was close if they needed me,” she says, “which they never did.” When Call Me Madam went out on national tour, though, Stritch, all of twenty-five, was leading the company. Goldilocks followed, before Noel Coward wrote the role of Mimi Paragon in Sail Away just for Stritch. Mimi, like her inspiration, knew her way around an arched eyebrow and a sarcastic bon mot. Not surprisingly, Stritch was a sensation. It nonetheless took almost a decade for her next Broadway musical, but this one was legendary.

Elaine Stritch in her dressing room at the Savoy Theatre, London. 1973. Photo by Allan Warren, via WikiCommons.

As Joanne in Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s Company, Stritch bellowed the searing eleven o’clock number, “The Ladies Who Lunch.” To this day, it is considered one of the all-time greatest interpretations of any musical theater song. Hal Prince’s acclaimed 1994 revival of Show Boat was another triumph but the best was still to come. In 2001, under the direction of George C. Wolfe, Stritch premiered Elaine Stritch at Liberty, an autobiographical one-woman show in which Stritch gossiped, confessed, kvetched, cajoled, and reveled in a musical tour of her life and career. For At Liberty, she finally took home a Tony Award, before playing the show for years in New York, London, and on tour. In 2010, she successfully, if improbably, succeeded Angela Lansbury in A Little Night Music.

Of all the women in [Nothing Like a Dame], she was the only one I was scared to meet. The phone calls didn’t assuage my fears, nor did the Carlyle’s waiter who, upon hearing I was there to meet Stritch laughingly said, “Good luck!” But I needn’t have worried. Stritch isn’t mean, she’s just blunt to a degree that’s so unusual it’s occasionally unnerving. As Bebe Neuwirth says of her, “She doesn’t know how to lie, on or offstage.” And she doesn’t suffer fools well. But once she trusts, she’s delightful. And warm enough to have extended an invitation to Thanksgiving dinner.

…

In your show, Elaine Stritch: At Liberty, you said that you didn’t know why you wanted to be an actress. But you did choose to pursue acting over anything else. What gave you the instinct that you’d be any good?

I don’t think it’s an instinct, I don’t think that’s the right word. I don’t have an answer to that today.

Calling?

Those are all two-dollar words. I don’t believe in all of that, “calling” and “career.” I wasn’t thinking about . . . I think if I was really dead-honest, I was . . . everybody else was going away to college and I didn’t want to. I don’t know the reason why that was, either. I thought I’d rather learn by experience all of the subjects they were going to teach me in college. That’s a dumb statement. But I didn’t want to go to college. I wanted to be an actress but I still can’t tell you why. I think I’m . . . I don’t think I’m really a happy camper inside and I think it’s an escape for me. I’ve gotten to like myself a lot better as the years go by, but I’m still not hung up on myself.

You have actually said that it’s really hard for you to play yourself. During Elaine Stritch: At Liberty, you said that a vacation would be putting on a costume and playing someone else.

At the time I was doing Elaine Stritch: At Liberty I wasn’t thinking about philosophizing my position and what I would or wouldn’t like to do. This was a tremendously courageous thing for me to do, but it was good. Just like I read a good play—I read a Tennessee Williams play, an Edward Albee play—I read what I wrote and what John Lahr wrote and I liked it. I thought, “This is a good part for me.” That sounds like a joke but it was a good part for me to play. It was the first time I had an opportunity to put myself on the stage. Because I am a really true-blue actress. When I take on a part I play the part. Of course I bring Elaine Stritch to it, that’s why they hire me. But I am interpreting another, I am inside somebody else’s skin. So, you know, acting is . . . I don’t know what it is. I don’t think it’s given enough credit in the arts. I think it’s a real art form, acting. I don’t know. I don’t think a lot of people have the talent—my kind of talent—to be an actress. But there are a lot of good ones out there. I am always so thrilled when I go to the theater and see a performance. I just think that’s the best. There was a marvelous expression in the Times the other day in the review of Australia. They talked about all of the epic qualities of the movie but they said a very simple thing about Nicole Kidman, who I think is a very good actress. They said: “she gave a performance.” And I thought, “what a wonderful notice.” I hope she appreciates it.

I want to go back to your early days, you came to New York for whatever reason you . . .

For whatever reason. Look, it’s not as complicated as all that. I was not going steady with someone. My beau had already gone to New York to become an actor. He was a writer named James Lee. He wrote [the play] Career and he also wrote for television; he was one of the writers on Roots. So what was I gonna do? I didn’t want to go to college. I wasn’t in love. I mean, I loved Jimmy but I wasn’t interested in getting married. I wish it would stop there. I wanted to become an actress. Why? I don’t know. I think you deal with that better than I deal with it. I’d like to be able to answer it better. But I do think that I wasn’t too hung up on myself and I wanted to be everybody else I could think of.

The reason I used the word “instinct” is because I think sometimes people have a desire or gut feeling that isn’t calculated, but they know that something speaks to them.

Something stirring.

Yeah.

I see what you mean. Yes. And I also wanted out of Michigan. I love Michigan but I didn’t want to spend all my life there, I wanted to see the world. Another answer I’ve given to the question, “why did you want to become an actress” is that I wanted higher ceilings. It’s as good an answer as any. I once played a game at a party and we all had to give the best answer for “why did you become an actor.” Mine was, “to get a good table at 21.” Ho ho ho. I think “higher ceilings” would have won at that party but I hadn’t thought of that yet. [The actor] Marti Stevens gave the best answer ever. Actually, the question was, “why did you go on the stage” and Marti Stevens said, “to get out of the audience.” That’s a great answer.

Once you were in New York and at The New School, how did you get work and audition?

I was going to school.

Yes, but you were cast in Loco pretty quickly after school. Did that seem like a fluke to you or were your peers also getting work easily? Did it feel like a struggle?

I don’t know.

Did you have to work for money?

I waited tables at The New School, but I did it not because I needed the money; I did it for the experience.

The human experience?

Yeah.

Did it work?

Yeah. And I did it to show off to Marlon Brando.

Did that work?

Yeah. I was showing that I wasn’t just this rich girl from Michigan. I could be a waitress, too. You see there’s a little Joan Crawford/Mildred Pierce in all of us! It was all of those things. . . . I am very honest about things like that today. Then I wasn’t.

In what ways are you honest now that you were not then?

Well, I wish I could have laughed and told Marlon Brando that I was trying to influence him. But you don’t do that at seventeen. You wait ’til you’re in your eighties ’til you get that kind of honesty. I think I could do a lot of things today that I couldn’t do then as far as being straight- forward and on the level with people. I figured it out that none of us have anything to hide. There’s nothing about me that I couldn’t tell everybody in the world. There really isn’t. And that’s a good way to be. I love the expression “secrets are dangerous.” I really think they are. “Don’t tell anybody, but . . .” is the most boring line in the world. It really is. If you don’t want them to tell anybody, don’t tell them!

In saying secrets are dangerous, do you mean that the truth frees you?

Absolutely. And I think what has transpired without your knowing it is that you kind of, at last, dig yourself.

…

I need a Judy Garland story.

I’d have to look ’em up, Honey.

For people like me, it’s like sitting at my grandmother’s lap and listening to family legend.

I know, I know. Judy Garland, when she came to the opening night party of Sail Away, I made up my mind not to drink at all at that party. There were a lot of famous people there. Before I knew it I saw Judy leaving the Noel Coward suite, and she was going home. I thought, “My God, I haven’t talked to her, she hasn’t told me how she liked the show, and I really want to hear what she thought more than anyone.” They had those see-through elevators at the Savoy Hotel. I ran out to the hall and she was just on the elevator and it was starting to disappear. And before her head got out of view from me, she went, “Elaine, about your fucking timing . . . ” and then she disappeared. It was absolutely brilliant. She knew what she was doing! Her timing was divine! And music to my ears, of course.

Do you have any stories about working with George Abbott on Call Me Madam?

Oh, he was a marvelous director, a wonderful man and an extraordinary human being. I loved him. He did one great thing once with me. When I came down to get notes before opening night, I had a scotch and soda in a coffee mug. Of course I was making it very believable. ’Cause while he was giving the notes I was blowing on the coffee. I was blowing on the scotch. And all of sudden George Abbott said to me, “Can I have a taste of that Elaine? Is that coffee?” And my voice went up two octaves and I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Could I have a taste?” And I said, “Sure.” I’ll tell you what a great guy he was. He took the coffee mug from me and he blew on it and then he took a sip. And then he handed it back to me and said, “Man that’s good coffee.”

Do you have Richard Rodgers stories?

Oh, I loved him. But he didn’t like me. He was an alcoholic, you know, and alcoholics resent other alcoholics. He paid me a great compliment once, though. He said, “I would give her the lead in a show but I just don’t think she could handle it. Because when she does a number, it is so good that I never think she can do it again.” It’s a great compliment but it isn’t very conducive to working.

It is a back-handed compliment.

Well he was a back-handed kind of fellow. He is a hard person to talk about.

Did you think it was personal?

Oh no, he liked me very much. But I made him nervous because I drank. That would make any director or producer—but the funny thing with him was that he drank twice as much as I did.

Did he recognize that?

No, he didn’t at all.

Both Abbott and Rodgers knew that you were drinking . . .

It never bothered George Abbott because I didn’t drink too much. Well, I probably did drink too much, but I was never drunk on the stage in my life.

Was drinking in the theater more commonplace in general?

Absolutely. Everybody had booze in their dressing room. Nobody does anymore. In London, in the theater you have cocktail parties at intermission. It’s a big deal having a little sherry or a little of this or that. But too many people have abused the privilege in this country. All of our great actors were huge drinkers. Tallulah Bankhead, John Barrymore, Bela Lugosi. So many. Lots and lots of people.

The people you mention famously got seriously drunk. That was never you, though.

No, absolutely not. Maybe a couple of times my timing was off because I had three instead of two drinks, but nothing to write home about.

…

Do you read reviews?

Oh yes, I can’t wait. Terrified to read them and thrilled to death when they are good. I haven’t gotten a lot of bad reviews; I’ve gotten a few in my life but nothing that upset me terribly.

There are a lot of actors who . . .

I can’t believe that they don’t read their reviews.

Do you go to the theater today?

Yeah, I go. But I am not going to see The Little Mermaid if that’s what you mean. I like Jane Krakowski, I think she’s good. And I like Kristin Chenoweth. I’m getting very excited about the opening of Pal Joey because my good friend Stockard Channing is in it. The theater is not what it was. It’s the fabulous invalid. It’s having a tough time because of the economy but it will come back. I worry about Maxwell [her nephew, a twenty-nine-year-old actor who just moved to New York]. Nobody who comes here to get into the theater can get an agent. It takes years. You have to go on those cattle calls. This is a tough racket. It really is a tough racket.

…

If performing hadn’t worked out for you, do you have any notion of what you might have been doing?

Supposition is really boring but I’ll give it a shot: Stay home!!

Is there anyone you’ve never worked with who you wish you had?

If I am supposed to, it’ll happen. I reiterate: supposition to me is a long yawn.

I think the word is “boring.”

[Laughs] OK, whatever you think is fair.

Excerpted from Nothing Like a Dame: Conversations with the Great Women of Musical Theater by Eddie Shapiro. Shapiro is a freelance writer and theater journalist whose work has appeared in Out Magazine, Instinct, and Backstage West. He is the author of Queens in the Kingdom: The Ultimate Gay and Lesbian Guide to the Disney Theme Parks.

The post In remembrance of Elaine Stritch appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 5/30/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

obituary,

macdonald,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Brahms,

tempo,

malcolm,

Malcolm MacDonald,

Schoenberg,

suzanne,

dallapiccola,

macdonald’s,

calum,

Add a tag

By Suzanne Ryan

With great sadness, Oxford reports the passing of esteemed music author and critic Malcolm MacDonald, who died on 27 May 2014.

MacDonald was until December 2013 Editor of the modern-music journal Tempo, and reviewed regularly for BBC Music Magazine and the International Record Review. He wrote both under his given name and as Calum MacDonald (to avoid confusion with the composer also named Malcolm MacDonald).

MacDonald contributed enormously to the literature and resources on numerous late-nineteenth and twentieth-century composers, and in the community of musicians and scholars, he was a champion of many. The list of figures is long, and includes the likes of Johannes Brahms, John Foulds, Ronald Stevenson, Alan Bush, Erik Bergman, Dmitri Shostakovich, Bernard Stevens, Luigi Dallapiccola, Antal Doráti, and Edgar Varèse. Among MacDonald’s several contributions to The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Grove Opera, his article on English composer and music journalist Havergal Brian was of particular importance, and reflects a substantial body of work elsewhere published on Brian.

As part of his impressively varied list of publications, MacDonald is author of two volumes in the venerable Master Musicians series: the distinguished Brahms (Schirmer 1990, reissued in 2001 from OUP) and the indispensable Schoenberg (the first edition published with Dent in 1976, and the second edition in 2008 with OUP). In his Preface to the First Edition of Schoenberg, we find:

The most a writer may do is to place the music in perspective and give it a human context; from which, perhaps, its human content will emerge more clearly. That is what I have tried to do.

And this is what, at the very least and amidst his myriad achievements, Malcolm MacDonald has indeed done. His work will remain valuable, and his legacy vital, for generations.

Suzanne Ryan is Editor in Chief, Humanities and Executive Editor, Music at Oxford University Press in New York.

The post In memoriam: Malcolm MacDonald appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 4/1/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Geography,

obituary,

Harm de Blij,

harm,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

himmler,

blij,

“harm,

deblij,

misanthropes,

kaveney,

Add a tag

Oxford University Press is saddened to hear of the passing of Harm de Blij on Thursday, 27 March 2014. De Blij was a giant in geography and had an illustrious career as a teacher, researcher, writer, public speaker, and TV personality. He was passionate, and one of those people who brought out the best in those around him.

“I know that was certainly true for me,” noted Dan Kaveney, Executive Editor-Higher Education. “When I was with Harm I always felt like a better and more capable person than I am. I worked just a little bit harder and more carefully to live up to his standard, and feel very fortunate to have had him as a colleague and a friend.”

“Harm was one of the most upbeat misanthropes I have ever known, and I’m very glad that I did,” added Tim Bent, OUP’s Executive Trade Editor. “He was in my office once and spotted the Longerich biography of Heinrich Himmler on a shelf. De Blij said that he had been out walking with his father in the Hague one day in 1943 and that they had seen Himmler drive by in his staff car; Himmler apparently was visiting the former homes of deported Jews and picking out art to steal. Harm always knew how to lend personal and historical depth to his geography.”

Former OUP Editor Ben Keene remarked, “Harm was one of my favorite authors to work with at OUP and in fact the first that I managed on my own, many years ago. I learned so much from him and still remember our first lunch when he ordered steak with a glass of red wine and asked the waitress to hold the green beans.”

Harm de Blij was the John A. Hannah Professor of Geography at Michigan State University. He authored 30 books, including Why Geography Matters, The Power of Place, and Physical Geography.

Harm de Blij

1935 – 2014

Image courtesy of deblij.net

The post In memoriam: Harm de Blij appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 3/14/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

British,

*Featured,

jad adams,

tony benn,

tony benn diaries,

tony benn obituary,

benn,

Books,

History,

Biography,

diary,

Politics,

Current Affairs,

obituary,

diaries,

Add a tag

By Jad Adams

Tony Benn has left as an enduring monument: one of the great diaries of the twentieth century, lasting from 1940, when he was fifteen, to 2009 when illness forced him to stop.

They are published as nine volumes but these are perhaps ten percent of the 15 million words in the original dairy. I am one of the few people to have had access to the manuscript diary, in the course of writing my biography of Benn. For this I received every assistance from him and his staff in the jumbled, chaotic office in the basement of his Holland Park Avenue home.

The diaries of course are of historic interest because they reveal the work of a cabinet minister and member of parliament for more than fifty years. Over time the Benn charts post-war hope, the rise of the Labour militants, the battle of Orgreave, and the decline of the Left. The books also have descriptions of constituents’ experiences in his weekly surgery, an opportunity to meet the people and sample their woes, which is hated by some MPs but was embraced by Benn.

They also show the development of Benn’s family of four children, twelve grandchildren, and the suffering of the death of parents and partner. One would be hard put to it to find anywhere in literature a more poignant description of death and continuing loss than Benn’s of Caroline, his partner of more than fifty years whose illness and death was described in remorseless detail in manuscript, some of which was published in More Time for Politics (2007).

Benn had always felt he ought to be writing a diary, as a part of the non-conformist urge to account for every moment of life as a gift from God. He explained at one of our last formal conversations: ‘It’s very self obsessed. I must admit it worries me that I should spend so much time on myself, I saw it as an account, accountability to the Almighty, when I die give him 15 million words and say: there, you decide. I think there is a moral element in it, of righteousness.’

This need to see time as a precious resource to be accounted for went back to his father, William Wedgwood Benn (Later Lord Stansgate) who expected the boy Benn to fill in a time chart showing how he had made use of his days. Benn senior had read an early self-help book by Arnold Bennett called How to Live 24 Hours a Day on making the best use of time. ‘Father became obsessed with it,’ Benn said.

Tony Benn had been keeping a diary sporadically since childhood. It had always been his ambition to keep one, and early fragments of diary exist, including one during his time in the services, where diary-keeping was forbidden for security reasons so he put key words relating to places or equipment in code. In the 1950s he began keeping a political diary and wrote at least some parts of a diary for every year from 1953. The emotional shock of his father’s death in 1960 and subsequent political upsets stopped his diary writing in 1961 and 1962 but, with a return to the House of Commons in sight, he resumed it in 1963.

He started dictating the diary to a tape recorder in 1966 when he joined the cabinet because he could not dictate accounts of cabinet meetings to a secretary who was not covered by the Official Secrets Act. Benn would store the tapes, not knowing when he would transcribe them, or indeed if they would be transcribed in his lifetime. His daughter, Melissa spoke of arriving at their home late at night when she was a teenager, and hearing her father’s voice dictating the diary, followed by snoring as he fell asleep at the microphone.

Benn stopped writing the diary after he fell ill in 2009 in what was probably the first stroke he was to suffer. He explained to me:

‘You can’t not be a diarist some of the time. One day is much the same as the other and it is a lot of effort. You really do have to be very conscientious and keep it up in detail and keep up the recordings and so on and it took over my life, also I’m not sure now that I’m not in a position on the inside on anything where my reflections would be interesting. I think my reflections might be as interesting as anybody else’s but whether it constitutes a diary when I’m not at the heart of anything…

‘I never thought of it as an achievement, just something I did, it’s been a bit of a burden to have to write it all down every night. It began as a journal where I put down things that interested me during the war, I drew a little bit on that for Years of Hope (1994). You can say you’ve achieved a reasonably accurate daily account of what has happened to you and since people are always shaped by what has happened to them so if you have a diary you get three bites at your own experience: when it happens, when you write it down and when you read it later and realise you were wrong.’

Benn did not think he would publish it in his lifetime, but in about 1983 he decided to type up six months and have a look at it. He invited Ruth Winstone to help with the diary in 1985 and found they worked so well together that she stayed and edited all the diaries.

His final thought on the long labour of the Benn Diaries was: ‘I couldn’t recommend anyone to keep a diary without warning them that it does take over your life.’

Jad Adams’ Tony Benn: A Biography is published by Biteback. His next book is Women and the Vote: A World History to be published by OUP in the autumn.

Image credit: Portrait of Tony Benn. By I, Isujosh. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post In memoriam: Tony Benn appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 3/13/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Andy Calder,

Brain Sciences,

Cognitive Neuroscience,

obituary,

calder,

cognition,

nephews,

nieces,

andy,

Books,

Autism,

*Featured,

Conduct Disorder,

Science & Medicine,

Face Perception,

Oxford Handbook of Face Perception,

Social Abilities,

Susan Gathercole,

The Psychologist,

1965–2013,

gathercole,

neuroscientist,

Add a tag

By Susan Gathercole

Andy Calder (1965–2013)

Andy Calder, dearly loved by his family and his many friends and colleagues from all over the world, died unexpectedly on 29 October 2013. Born in Edinburgh in 1965, he was a loving brother to his sisters Kath and Clare and brothers-in-law Gary and Tony, and a devoted uncle to his nieces and nephews.

Andy was known internationally as a leading cognitive neuroscientist. He was a deep thinker, a meticulous experimenter, and an inspiration for those who worked alongside him. His ground-breaking research led to major new insights into vital social abilities, such as how we recognise faces, and how the brain processes and distinguishes between emotions.

After completing a PhD at Durham, Andy joined the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit at Cambridge (then the Applied Psychology Unit) in 1993, becoming a programme leader in 2000. In addition to his dedicated team in Cambridge, Andy worked closely with many collaborators, bringing to each project excellence in methods and precision in scientific thinking. This led to new discoveries including the brain systems that underlie unusual social abilities in conduct disorder and autism.

The news of his untimely death is devastating for all that knew him. Not yet 50, Andy had a wonderful future as a scientist still ahead of him. His abilities to answer important fundamental questions using rigorous methods will continue to inspire his many collaborators and the broader field of social neuroscience. A passion for overseas exploration made Andy a great travelling companion and a keen guest in the laboratories of his dear friends and fellow scientists, including Gilli Rhodes and Colin Clifford in Australia.

Andy was wonderful company. He was an entertaining house guest with his family every Christmas, and took a keen interest in all his nieces and nephews Clark, Amy, Ava, Rebecca, Cameron, Tim and Eve as they were growing up. He had a passion for film and theatre, and every summer would make the trip home to take full advantage of the Edinburgh Festival. A gifted pianist and singer, Andy was a key figure in pantomimes and productions in Cambridge. He made many lasting friendships with colleagues, who were delighted by his warmth, lightness of spirit, and wit (see colleagues’ memories).

Andy will be held dearly in the hearts of the many that knew him. He is greatly missed, but his spirit, life and achievements will be celebrated for many years to come.

Susan Gathercole is Unit Director at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit. This article originally appeared on The Psychologist.

Andy Calder was a leading social cognitive neuroscientist at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit. He was the lead author on Oxford Handbook of Face Perception.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of Susan Gathercole.

The post Memories of Andy Calder appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/10/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

obituary,

rosen,

gmo,

oxford music online,

OMO,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Grove Music Online,

Charles Rosen,

Add a tag

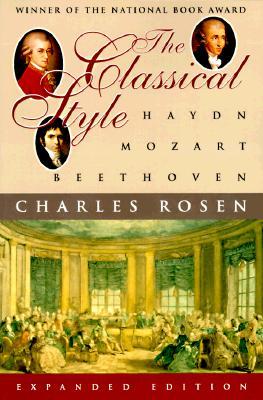

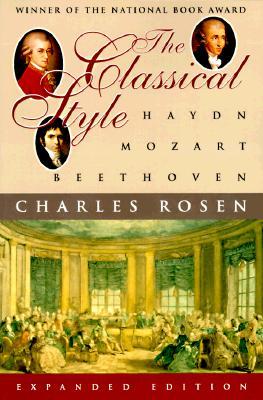

Charles Rosen, a titan of the music world, passed away on Sunday. He was a fine concert pianist, groundbreaking musicologist, and a thoughtful critic who wrote prolifically, including regular articles for the New York Review of Books, not just on music but on its broader cultural contexts. We’re excerpting his entry in Grove Music Online by Stanley Sadie below.

Rosen, Charles (Welles)

(b New York, 5 May 1927). American pianist and writer on music. He started piano lessons at the age of four and studied at the Juilliard School of Music between the ages of seven and 11. Then, until he was 17, he was a pupil of Moriz Rosenthal and Hedwig Kanner-Rosenthal, continuing under Kanner-Rosenthal for a further eight years. He also took theory and composition lessons with Karl Weigl. He studied at Princeton University, taking the BA (1947), MA (1949) and PhD (1951), in Romance languages. Some of his time there was spent in the study of mathematics; his wide interests also embrace philosophy, art and literature generally. After Princeton he had a spell in Paris, and a brief period of teaching modern languages at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But in the year of his doctorate he was launched on a pianist’s career, when he made his New York début and the first complete recording of Debussy’s Etudes. Since then he has played widely in the USA and Europe. He joined the music faculty of the State University of New York at Stony Brook in 1971.

As a pianist, Rosen is intense, severe and intellectual. His playing of Brahms and Schumann has been criticized for lack of expressive warmth; in music earlier and later he has won consistent praise. His performance of Bach’s Goldberg Variations is remarkable for its clarity, its vitality and its structural grasp; he has also recorded The Art of Fugue in performances of exceptional lucidity of texture. His Beethoven playing (he specializes in the late sonatas, particularly the Hammerklavier) is notable for its powerful rhythms and its unremitting intellectual force. In Debussy his attention is focussed rather on structural detail than on sensuous beauty. He is a distinguished interpreter of Schoenberg and Webern; he gave the première of Elliott Carter’s Concerto for piano and harpsichord (1961) and has recorded with Ralph Kirkpatrick; and he was one of the four pianists to commission Carter’s Night Fantasies (1980). He has played and recorded sonatas by Boulez, with whom he has worked closely. His piano playing came to take second place to his intellectual work during the 1990s.

Rosen’s chief contribution to the literature of music is The Classical Style. His discussion, while taking account of recent analytical approaches, is devoted not merely to the analysis of individual works but to the understanding of the style of an entire era. Rosen is relatively unconcerned with the music of lesser composers as he holds ‘to the old-fashioned position that it is in terms of their [Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven’s] achievements that the musical vernacular can best be defined’. Rosen then establishes a context for the music of the Classical masters; he examines the music of each in the genres in which he excelled, in terms of compositional approach and particularly the relationship of form, language and style: this is informed by a good knowledge of contemporary theoretical literature, the styles surrounding that of the Classical era, many penetrating insights into the music itself and a deep understanding of the process of composition, also manifest in his study Sonata Forms (1980). The Classical Style won the National Book Award for Arts and Letters in 1972. His smaller monograph on Schoenberg concentrates on establishing the composer’s place in musical and intellectual history and on his music of the period around World War I. Rosen’s interest in the thought and composition processes of the Romantics, also strong, is shown in his Harvard lectures published as The Romantic Generation. He has written many shorter articles, and contributes on a wide range of topics to the New York Review of Books.

Writings

The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (London and New York, 1971, enlarged 3/1997 with sound disc)

Arnold Schoenberg (New York, 1975/R)

‘Influence: Plagiarism and Inspiration’, 19CM, iv (1980–81), 87–100

Sonata Forms (New York, 1980, 2/1988)

‘The Romantic Pedal’, The Book of the Piano, ed. D. Gill (Oxford, 1981), 106–13

The Musical Languages of Elliot Carter (Washington DC, 1984)

with H. Zerner: Romanticism and Realism: the Mythology of Nineteenth-Century Art (New York, 1984) [rev. articles pubd in The New York Review of Books]

‘Brahms the Subversive’, Brahms Studies: Analytical and Historical Perspectives, ed. G.S. Bozarth (Oxford,1990), 105–22

‘The First Movement of Chopin’s Sonata in B-flat minor, op.35’, 19CM, xiv (1990–91), 60–66

‘Ritmi de tre battute in Schubert’s Sonata in C minor’, Convention in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Music: Essays in Honor of Leonard G. Ratner, ed. W. Allanbrook, J. Levy and W. Mahrt (Stuyvesant, NY,1992), 113–21

‘Variations sur le principe de la carrure’, Analyse musicale, no.29 (1992), 96–106

Plaisir de jouer, plaisir de penser (Paris, 1993) [collection of interviews]

The Frontiers of Meaning: Three Informal Lectures on Music (New York, 1994)

The Romantic Generation (Cambridge, MA, 1995) [based on the Charles Eliot Norton lectures delivered at Harvard; incl. sound disc]

Romantic Poets, Critics, and Other Madmen (Cambridge, MA, 1998)

Critical Entertainment: Music Old and New (Cambridge, MA, 2000) [collection of essays]

Charles Rosen

May 5, 1927 – December 9, 2012

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

The post In memoriam: Charles Rosen appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/10/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

obituary,

lunar,

patrick,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

patrick’s,

Science & Medicine,

david rothery,

rothery,

Patrick Moore,

cupful,

Add a tag

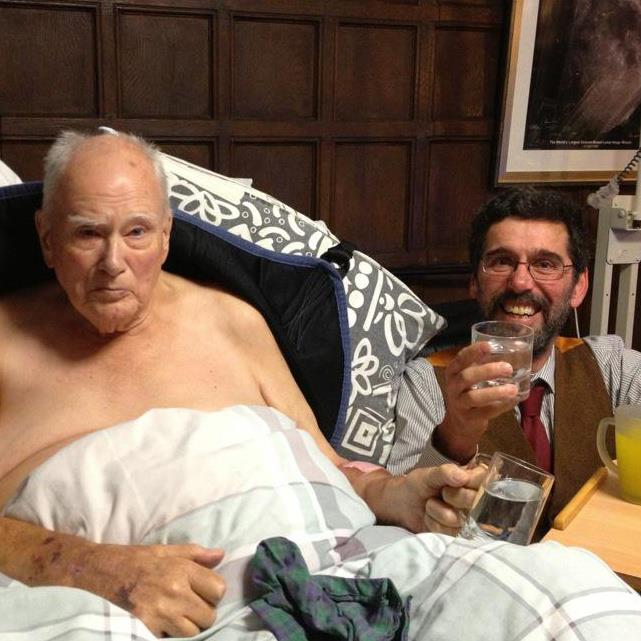

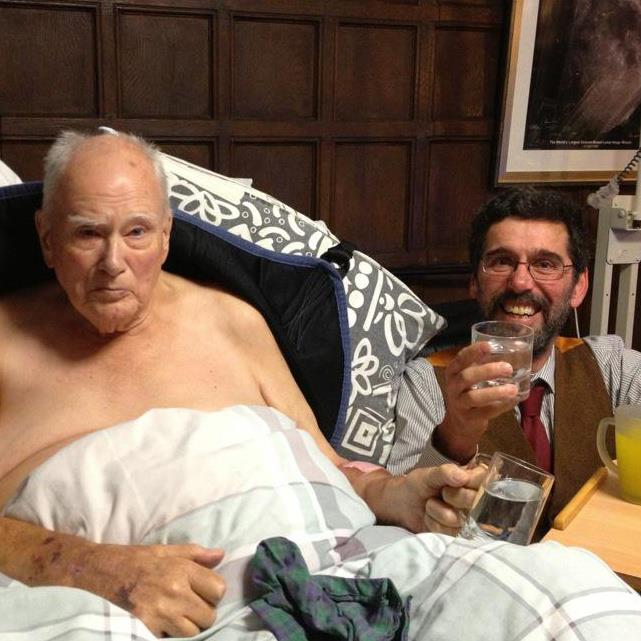

By David Rothery

There’s a Patrick Moore-sized hole in the world of astronomy and planetary science that is unlikely ever to be exactly filled. He presented “The Sky at Night,” a monthly BBC TV astronomy programme, from 1957 until his death. This brought him celebrity, and the books that he wrote for the amateur enthusiast were bought or borrowed in vast numbers from public libraries for half a century — including by myself as a schoolboy. Patrick was the mainstay of the BBC’s Apollo Moon-landing coverage that those of us of a certain age will never forget, and there can be few amateur or professional astronomers who grew up in the UK without having been influenced by him. Tributes posted on the Internet show that he was known and admired beyond these shores too. They also attest to Patrick’s extraordinary generosity, exemplified by numerous accounts of how he replied to letters from strangers (of whom in the early 1970s I was one) or took time to chat after his lectures.

Patrick served with distinction and under age as a navigator with Bomber Command during the war. I believe (on the basis of dark hints made during late night conversations) that he also spent time on special operations in occupied Poland, where his youth and assumed Irish identity afforded him a plausible (but surely high-risk) cover story. An encounter with what he referred to as ‘a working concentration camp’ led to his lifelong professed dislike of Germans (“apart from Werner von Braun, the only good German I ever met”).

After the war, Patrick became a school teacher and also very active in the British Astronomical Association notably in its lunar section on account of his painstaking and careful observations of the Moon, some of which were to prove useful for both the American and Soviet lunar missions. He became a friend of the science fiction visionary Arthur C. Clarke, with whom he shared the authorship of Asteroid (2005) sold in aid of Sri Lankan tsunami relief.

I first met Patrick when we were speakers at a meeting to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the discovery of Neptune, so that must have been 1996. He spoke about Neptune itself, and I about its main satellite Triton. Afterwards he was kind enough to remark that he had read my book (Satellites of the Outer Planets). Our first joint TV appearance was “Live from Mars,” an Open University TV programme on a Saturday morning in 1997 when NASA’s Mars Pathfinder landed, allowing us to broadcast the first new pictures from the surface of Mars for nearly 20 years. I became an occasional guest on “The Sky at Night” more recently, which led to a friendship, as with so many of his guests. The programme was usually recorded at Patrick’s home in Selsey, and Patrick delighted to put his guests up overnight, rather than send them to a nearby hotel. That was a cue for an impressively-laden supper table, copious quantities of lubricant, and entertaining — if sometimes outrageous — conversation. Patrick had a wry sense of humour, and would self-parody his supposed extreme views. However, I think he was being serious when, or several occasions, he styled a certain recent US President as “a dangerous lunatic”.

I witnessed Patrick’s mobility decline from walking sticks, to zimmer frame, to wheelchair. His once famously rapid speech became slurry, but his mind and monocle-assisted eyesight stayed sharp. Co-presenters assumed larger and large roles on “The Sky at Night,” but Patrick was always there as the pivotal host. I last saw him less than three weeks before his death, when I guested on what was to prove his last “Sky at Night.” He was drowsy at first, but his intellect soon kicked in. He steered our discussion as ably as of old, and we were treated to a vintage Patrick moment of scepticism “When someone gives me a cupful of lunar water, then I’ll admit I was wrong.”

I lingered afterwards for a chat — inevitably partly about cats. Noticing the time, Patrick ordered a gin and tonic for each of us, and was soon involved in good-natured banter with his carer about why she would not let him have a second. He encouraged me to write a book about Mercury, and kindly agreed to write the foreword if I did. That’s an offer that I shall no longer be able to take him up on, but wherever you are, Patrick, I hope someone’s brought you that cupful of lunar water by now.

Sir Patrick Moore

4 March 1923 – 9 December 2012

Patrick Moore with David Rothery earlier this year.

David Rothery is a Senior Lecturer in Earth Sciences at the Open University UK, where he chairs a course on planetary science and the search for life. He is the author of Planets: A Very Short Introduction.

Image credit: Image is the personal property of David Rothery. Used with permission. Do not reproduce without explicit permission of David Rothery.

The post In memoriam: Patrick Moore appeared first on OUPblog.

If I were a children's book author of a certain age, I'd be quaking in my boots. So many VIPs have died in 2012 and the year is only little more than half over. To the list of Maurice Sendak, Jean Craighead George, Else Minarik, and Donald Sobol, we must now add

Margaret Mahy, a New Zealander author and winner of the prestigious Hans Christian Anderson medal.

Mahy was a special favorite of mine. She wrote wonderful supernatural novels--I especially like

The Haunting and

The Changeover--but I'm also a big fan of her picture books.

The Man Whose Mother is a Pirate is classic Mahy, as is

The Three-Legged Cat. Both books feature characters who trade in their constricted lives to roam the world.

And what a marvelous stylist she was.

“The little man could only stare. He hadn’t dreamed of the BIGNESS of the sea. He hadn’t dreamed of the blueness of it. He hadn’t thought it would roll like kettledrums, and swish itself on to the beach. He opened his mouth and the drift and the dream of it, the weave and the wave of it, the fume and foam of it never left him again. At his feet the sea stroked the sand with soft little paws. Farther out, the great, graceful breakers moved like kings into court, trailing the peacock-patterned sea behind them.”--From The Man Whose Mother Was a Pirate

RIP Margaret Mahy.

Yes, Australia has lost two poets and it might look like carelessness to some. But we speak highly of them when they are gone.

Many of you will have already read bookmaker and artist Caren Florance's tribute to Rosemary Dobson, published a few days after her death in late June. It is very touching, and there is a link at the end to Jason Steger's obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald.

Here is an obituary by poet David McCooey, in The Age.

David Malouf's review of her Collected Poems appeared in The Age on June 2:

Spare poems point to natural phenomena, ''a small storm, tethered in the garden'', and the lives of friends. Take, for example, this tender but wickedly observant picture of a dying Christina Stead:

I sit beside the bed where she lies dreaming

Of pyrrhic victories and sharp words said,

She will annihilate the hospital …

Suppose her smouldering thoughts break out in flame,

Not to consume bed, nightdress, flesh and hair

But the mind, the working and the making mind

That built these towers the world applauds …

I have dreamt her nightmare for her. She wakes up

And turns to smile with quick complicity.

''I wasn't asleep. I watched you sitting there.''

The poems in Collected offer something more than the usual record of a progression. To read them is to follow a quiet mind, but an acute one, through a writing life that over the decades is increasingly responsive to what is near at hand and to the oddness as well as the grandeur of things.

She is a poet I readily admit to having glossed over and I look forward to remedying that, quickly.

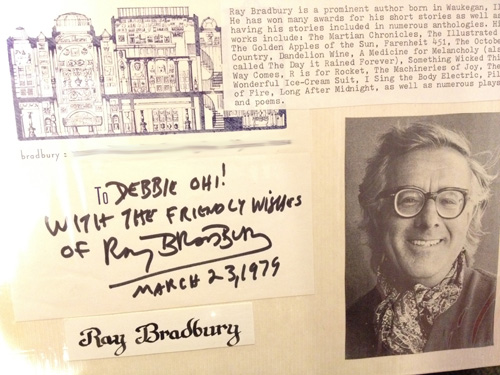

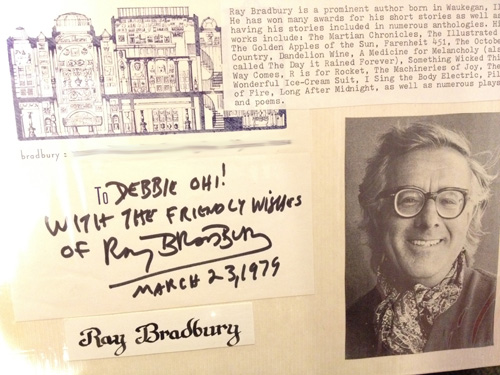

Above: page from my childhood autograph collection.

Just found out that Ray Bradbury died this morning at the age of 91. :-(

I always loved reading, but it wasn't until I read Ray Bradbury's Dandelion Wine that I became aware of style in writing. I'm generally a fast reader, but with Ray Bradbury's books I slowed way down so I could savour the language. His books helped me appreciate the importance of word choice, and also got me hooked on science fiction.

I wrote a song called "Homecoming" that was based on one of my favourite Ray Bradbury short stories, "The Rocket Man" (included in his R Is For Rocket short story collection). You can hear my group, Urban Tapestry, performing Homecoming in our live performance CD. I'm playing the rhythm guitar part on this track, Allison Durno plays lead guitar bits and Jodi Krangle sings lead. Allison and I sing some backup during the chorus. I've included the lyrics/chords below.

Even before I experienced family loss myself, I was deeply moved by this story and others by Bradbury. His writing affected me in so many ways, and was a major factor in my own desire to be a writer. I owe this man so much and had hoped to meet him in person someday.

For more info about Ray Bradbury, see http://www.raybradbury.com/

HOMECOMING

Words & music by Debbie Ridpath Ohi

Performed by Urban Tapestry (included on our live performance CD, Sushi and High Tea)

Many years ago, while at university, one of my professors required that his students write their own obituary. He told us that by writing our obits, we would begin to truly appreciate ourselves and others as individual human beings with innate worth and lasting value. He also said that until we stood back and looked at ourselves as a stranger would see us, we could never really know who we are.

Like most college students, we went along with the program as outlined and did as we’d been instructed. The lesson had interesting consequences for me along the way. I doubt any of us ever forgot what we learned from it.

Trying to look at your image in the mirror, as a stranger would, isn’t an easy task. Self-perception is always influenced by experience and what others have told you of their observations and expectations for you. The physical aspects that have always seemed flawed, or perfect, or questionable are your first impressions.

When you go past the physical to past experience, deeds, and failures with their requisite successes, you dwell on those bits that were less than perfect, less than desirable. Accepting the flawed episodes from a past that can’t be changed is a timely process. Without that acceptance, the successes ring as hollow and lifeless. Small indiscretions overpower small kindnesses. Praise is mitigated by remembered slights. And the cycle continues.

The act of writing one’s personal obituary allows for reflection on the overall picture of a person’s life—yours. The fact is that an obituary is merely a personal profile. It places the person within the framework of their own history.

Family and friends come to the foreground, along with major accomplishments within the person’s life. It’s not concerned with failures, but with successes, relationships, and contributions. It concentrates on those areas of one’s life that reflect the spirit and philosophy of the person.

The amount of detail held within the paragraphs that encompass a person’s life story depends on the purpose of the writer. Make no mistake; the obituary is a telling of a person’s profile or life story in miniature. It can celebrate that life, magnify it, examine it, whatever the writer wishes to convey. It can also bring to light the otherwise unknown deeds of a person, secrets held by those who knew her best.

By the time I finished my assignment, I’d reaffirmed several key points about myself. I’d come away with an acknowledgement of those relationships which mattered the most to me and knew why they did so. My failures up to that point had been assessed and laid to rest. I’d owned all of them, some for the first time, and they could no longer haunt me.

Successes, some of them never properly acknowledged, came to the foreground. I’d never before thought of those times I’d been in a rescue situation as successes. My actions had been necessary to keep another from greater harm. I’d not categorized them as anything other than being in the right place at the right time.

The exercise became a kind of “It’s a Wonderful Life” scenario. When approached that way, failures meant nothing, had no value. Only successes counted, and few, if any, of those for me had anything to do with money or personal gain.<

Many years ago, while at university, one of my professors required that his students write their own obituary. He told us that by writing our obits, we would begin to truly appreciate ourselves and others as individual human beings with innate worth and lasting value. He also said that until we stood back and looked at ourselves as a stranger would see us, we could never really know who we are.

Like most college students, we went along with the program as outlined and did as we’d been instructed. The lesson had interesting consequences for me along the way. I doubt any of us ever forgot what we learned from it.

Trying to look at your image in the mirror, as a stranger would, isn’t an easy task. Self-perception is always influenced by experience and what others have told you of their observations and expectations for you. The physical aspects that have always seemed flawed, or perfect, or questionable are your first impressions.

When you go past the physical to past experience, deeds, and failures with their requisite successes, you dwell on those bits that were less than perfect, less than desirable. Accepting the flawed episodes from a past that can’t be changed is a timely process. Without that acceptance, the successes ring as hollow and lifeless. Small indiscretions overpower small kindnesses. Praise is mitigated by remembered slights. And the cycle continues.

The act of writing one’s personal obituary allows for reflection on the overall picture of a person’s life—yours. The fact is that an obituary is merely a personal profile. It places the person within the framework of their own history.

Family and friends come to the foreground, along with major accomplishments within the person’s life. It’s not concerned with failures, but with successes, relationships, and contributions. It concentrates on those areas of one’s life that reflect the spirit and philosophy of the person.

The amount of detail held within the paragraphs that encompass a person’s life story depends on the purpose of the writer. Make no mistake; the obituary is a telling of a person’s profile or life story in miniature. It can celebrate that life, magnify it, examine it, whatever the writer wishes to convey. It can also bring to light the otherwise unknown deeds of a person, secrets held by those who knew her best.

By the time I finished my assignment, I’d reaffirmed several key points about myself. I’d come away with an acknowledgement of those relationships which mattered the most to me and knew why they did so. My failures up to that point had been assessed and laid to rest. I’d owned all of them, some for the first time, and they could no longer haunt me.

Successes, some of them never properly acknowledged, came to the foreground. I’d never before thought of those times I’d been in a rescue situation as successes. My actions had been necessary to keep another from greater harm. I’d not categorized them as anything other than being in the right place at the right time.

The exercise became a kind of “It’s a Wonderful Life” scenario. When approached that way, failures meant nothing, had no value. Only successes counted, and few, if any, of those for me had anything to do with money or personal gain.<

Oh – I like that. I just put it on my writing list of things to write and reflect about. I had students do that as well when we were talking about culture, but it was much more simplistic. It did, however, teach me a huge lesson about culture. The things I would put on my headstone are far different than the things the native Alaskan kids growing up in rural Alaska would put on theirs. It made me poignantly aware of the disconnect between the local cultural values and the school’s values.

Thanks, Elise. Native Americans I’ve known over the years have an entirely different take on the matter as well. Within the mainstream culture one’s accomplishments and deeds toward other humans reflect the person’s life “validity,” while for those traditional Native American’s I’ve known, the emphasis leans toward the person’s connection to and relationship with the earth and the Creator.

Glad you could use the exercise.

Claudsy

This is perhaps the most valuable of those types of writing exercises I’ve ever done. I wrote my own several years ago–it was the imaginary ‘what do you want people to remember you for’ kind of thing, and I kind of made it my own. It has meant a complete reordering of how I see myself, absolutely for the good.

That’s terrific, Margaret. I’m so glad that you could use something like this for your future benefit. I found the assignment so useful, and still do it on those rare occasions when it smacks my awareness. With the use for it, though, I doubt I’ll forget again.

So happy you dropped by with a comment. Take care and God bless.

Claudsy

This really is a great idea, to see ourselves as others do. We’ll either appreciate ourselves more or see where there’s room for improvement. ’s to you Claudsy.

’s to you Claudsy.

That’s always been the message for me in this exercise. It keeps a reality check available to us to be used whenever we need it.

Glad you enjoyed it. Thanks, Hannah.

Your welcome! You have such a unique voice in your postings, it’s almost as though I’m hearing you when I read even though I don’t know what your voice sounds like!

What a lovely thing to say. Actually, my voice changes with each type of writing that I do. I don’t know that I have only one.

You’d have to ask someone like MEG to know whether I do or not.

Claudsy

Yes, I think I know what you mean, Clauds. My voice takes on different facets with varying style of writing, too. Fun thought to think about!