new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: grossman, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 3 of 3

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: grossman in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: DanP,

on 8/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Economics,

Current Affairs,

money,

America,

Finance,

wealth,

economy,

reserve’s,

Wall Street,

transparency,

*Featured,

currency,

monetary,

Business & Economics,

Richard Grossman,

Federal Reserve,

economic growth,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

grossman,

economic policy,

federal bank,

federal funds,

federal policy,

Wrong nine economic policy disasters,

fomc,

fed’s,

montagu,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

As an early-stage graduate student in the 1980s, I took a summer off from academia to work at an investment bank. One of my most eye-opening experiences was discovering just how much effort Wall Street devoted to “Fed watching”, that is, trying to figure out the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy plans.

If you spend any time following the financial news today, you will not find that surprising. Economic growth, inflation, stock market returns, and exchange rates, among many other things, depend crucially on the course of monetary policy. Consequently, speculation about monetary policy frequently dominates the financial headlines.

Back in the 1980s, the life of a Fed watcher was more challenging: not only were the Fed’s future actions unknown, its current actions were also something of a mystery.

You read that right. Thirty years ago, not only did the Fed not tell you where monetary policy was going but, aside from vague statements, it did not say much about where it was either.

Given that many of the world’s central banks were established as private, profit-making institutions with little public responsibility, and even less public accountability, it is unremarkable that central bankers became accustomed to conducting their business behind closed doors. Montagu Norman, the governor of the Bank of England between 1920 and 1944 was famous for the measures he would take to avoid of the press. He adopted cloak and dagger methods, going so far as to travel under an assumed name, to avoid drawing unwanted attention to himself.

The Federal Reserve may well have learned a thing or two from Norman during its early years. The Fed’s monetary policymaking body, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), was created under the Banking Act of 1935. For the first three decades of its existence, it published brief summaries of its policy actions only in the Fed’s annual report. Thus, policy decisions might not become public for as long as a year after they were made.

Limited movements toward greater transparency began in the 1960s. By the mid-1960s, policy actions were published 90 days after the meetings in which they were taken; by the mid-1970s, the lag was reduced to approximately 45 days.

Since the mid-1990s, the increase in transparency at the Fed has accelerated. The lag time for the release of policy actions has been reduced to about three weeks. In addition, minutes of the discussions leading to policy actions are also released, giving Fed watchers additional insight into the reasoning behind the policy.

More recently, FOMC publicly announces its target for the Federal Funds rate, a key monetary policy tool, and explains its reasoning for the particular policy course chosen. Since 2007, the FOMC minutes include the numerical forecasts generated by the Federal Reserve’s staff economists. And, in a move that no doubt would have appalled Montagu Norman, since 2011 the Federal Reserve chair has held regular press conferences to explain its most recent policy actions.

The Fed is not alone in its move to become more transparent. The European Central Bank, in particular, has made transparency a stated goal of its monetary policy operations. The Bank of Japan and Bank of England have made similar noises, although exactly how far individual central banks can, or should, go in the direction of transparency is still very much debated.

Despite disagreements over how much transparency is desirable, it is clear that the steps taken by the Fed have been positive ones. Rather than making the public and financial professionals waste time trying to figure out what the central bank plans to do—which, back in the 1980s took a lot of time and effort and often led to incorrect guesses—the Fed just tells us. This make monetary policy more certain and, therefore, more effective.

Greater transparency also reduces uncertainty and the risk of violent market fluctuations based on incorrect expectations of what the Fed will do. Transparency makes Fed policy more credible and, at the same time, pressures the Fed to adhere to its stated policy. And when circumstances force the Fed to deviate from the stated policy or undertake extraordinary measures, as it has done in the wake of the financial crisis, it allows it to do so with a minimum of disruption to financial markets.

Montagu Norman is no doubt spinning in his grave. But increased transparency has made us all better off.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Federal Reserve, Washington, by Rdsmith4. CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) European Central Bank, by Eric Chan. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Transparency at the Fed appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 6/4/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Current Affairs,

unemployment,

inflation,

Wrong,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

Richard S. Grossman,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

economic indicators,

jobs report,

Nine Economic Disasters,

unemployment data,

unrate,

grossman,

statistic,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

For the past half dozen years or so, the first Friday of the month has brought fear and dread to large portions of the United States. This heightened anxiety has nothing to do with the phases of the moon, the expiration of multiple financial derivatives, or concerns about not having a date for the weekend. No, at 8:30 am (Eastern Time) on the first Friday of each month, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics releases the unemployment data for the previous month.

The release of the unemployment data sets off a media frenzy, as pundits speculate on the winners and losers. What do the numbers foreshadow for the economy? Have we put the Great Recession behind us? How will Wall Street receive the news? And, perhaps most importantly, how does it affect the Administration’s popularity?

There are plenty of reasons why unemployment should be the “marquee” economic statistic. Unlike other important economic indicators, such as GDP, exports, and new housing starts, the human cost of unemployment is inescapable. On an aggregate level, every tenth of a percent increase in the unemployment rate represents about an additional 200,000 people out of work. It is a lot tougher to conjure up a picture of a 1.2 percent decline in GDP.

On the personal level, when unemployment touches our family, friends, and neighbors, it is hard to ignore.

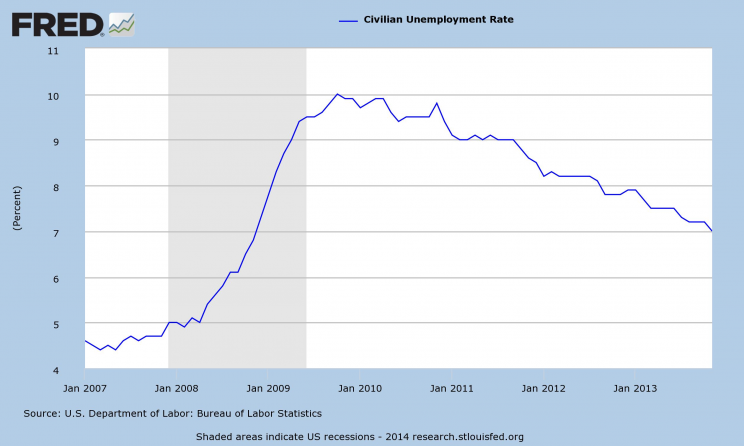

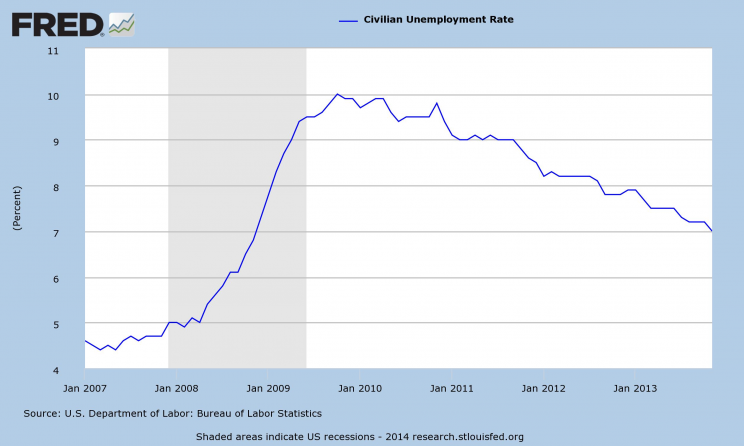

The unemployment rate has been at the center of a monthly drama since the beginning of the Great Recession. As the economy worsened, the unemployment rate surged upward until it hit 10% of the workforce in October 2009, its highest rate in more than 25 years.

Data Source: FRED, Federal Reserve Economic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: Civilian Unemployment Rate (UNRATE); US Department of Labor: Bureau of Labor Statistics; accessed 19 May 2014.

With each uptick in unemployment, political analysts wondered out loud if the bad news spelled the failure of the Obama presidency…or the lengthening of the odds against his chances at a second term. For the Administration’s part, the chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors typically puts out a statement by 9:30 am on the day of the release, putting the best spin possible on the unemployment data.

Although the unemployment numbers have been and will remain an important economic indicator, in recent months their importance is being overshadowed by another statistic: inflation. There are a couple of reasons for this.

First, even though the unemployment rate has fallen consistently since November 2010, when it was 9.8%, until April 2014, when it was 6.3%, it is clear that the economy has not fully recovered from the Great Recession. Wage growth is anemic; there are still an alarming number of discouraged workers (who are no longer counted as unemployed because they have given up looking for work); and GDP growth is sluggish.

Second, despite the continuing weakness in the economy, lower unemployment has raised concerns that that the economy is overheating. Declining unemployment combined with several years of monetary stimulus via quantitative easing and other unconventional methods has led to concerns that inflation may emerge at any moment.

So far, there is little evidence that we are experiencing a sharp upturn in inflation. Nonetheless, concern that emerging inflation will force the Fed to undertake contractionary monetary policy which, in turn, may have adverse effects for both the high flying stock market and the still low flying economy, are now gaining ground.

Don’t expect the unemployment rate to sink into obscurity anytime soon. It has always been an important indicator of the health of the economy and will remain so. Just be prepared for a second media frenzy around the middle of each month—when the inflation indices are released.

Richard S. Grossman is Professor of Economics at Wesleyan University and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. He is the author of WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them and Unsettled Account: The Evolution of Banking in the Industrialized World since 1800. His homepage is RichardSGrossman.com, he blogs at UnsettledAccount.com, and you can follow him on Twitter at @RSGrossman. You can also read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Changing focus appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 5/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

spreads,

Wrong,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

Nine Economic Policy Disasters,

Richard S. Grossman,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

European economy,

European sovereign debt crisis,

German government,

debtors,

deflation,

fiscally,

grossman,

merkel,

governments’,

Books,

Economics,

Current Affairs,

angela,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

Because Europe accounts for nearly a quarter of the world’s economic output, this question is important not only to Europeans, but to Africans, Asians, Americans (both North and South), and Australians as well. Those who forecast that the United States’s relatively anemic five-year-old recovery is poised to become stronger almost always include the caveat “unless, of course, Europe implodes.”

So, can we stop worrying about Europe?

Recent signs have been encouraging.

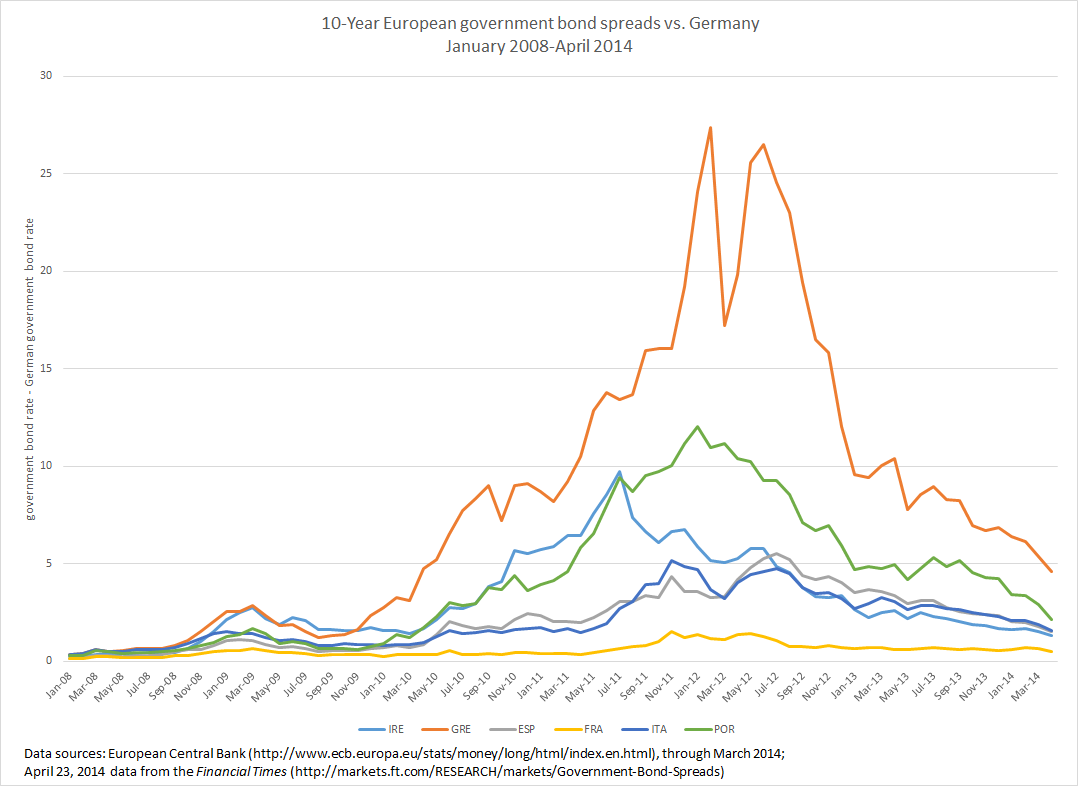

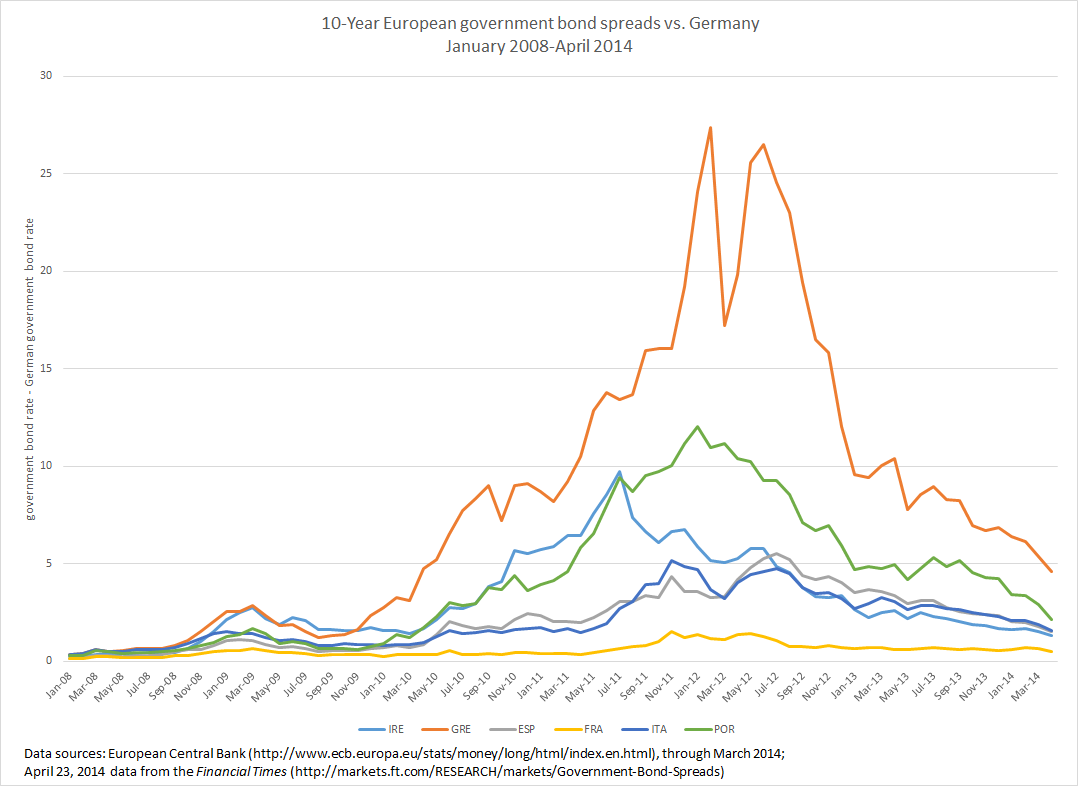

Consider the following graph, which shows the spread between the yields on the 10-year bonds of several European countries and those of the German government. Because the German government’s finances are relatively healthy—and Germany is thus viewed as being quite likely to pay back what it owes—it is able to borrow money more cheaply than most of its neighbors. For 10 years loans, the German government pays interest of about 1.5%, which is among the lowest rates in Europe.

Before the European sovereign debt crisis erupted 2009, spreads were not especially wide. In 2008, the Greek government paid between 0.25-0.75% more to borrow money for 10 years than the German government. When the sorry state of the Greek government’s finances became public, however, the spread between Greek and German yields soared to more than 20% and the European Union (EU) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were called in to bail out the Greek government. Ireland, Portugal, and Spain also received rescue packages (as did Cyprus), while Italy appeared to be headed down the same road. Note the wide spreads between these governments’ borrowing costs and those of the fiscally virtuous Germans.

During the last year or so, Greek, Irish, Portuguese, and Spanish spreads have shrunk considerably — not to their pre-crisis levels, but far below their sky-high levels of 2010-2012 — suggesting that doubts about the sustainability of European governments’ debts is receding. The decline in spreads is due in part to the austerity measures adopted as a condition of the EU/IMF bailouts, which have improved the budget outlook among the fiscally weaker countries. German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s April visit to Greece was widely seen as an effort to show support for fiscal austerity and economic restructuring adopted by the Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras.

Angela Merkel – Αντώνης Σαμαράς, 2012. Photo by Αντώνης Σαμαράς Πρωθυπουργός της Ελλάδας. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

In other positive news, Markit’s European purchasing manager’s composite index for March (released on 23 April 2014), which is considered a proxy for economic output, rose to a nearly three-year high. The index shows a continuous expansion of business activity since last July and forecasts that a backlog of work will lead to further growth in May.

Despite these positive signs, Europe is not out of the woods.

Unemployment remains stubbornly high, due, in part, to austerity: over 25% in Greece and Spain; over 15% in Portugal and Cyprus; and over 10% in France, Ireland, Italy, and a number of other countries.

Although prices are rising slightly in the European Union on average, Greece, Spain, Portugal and a few other European countries are experiencing deflation. Moreover, overall inflation in the EU is below that in the United States, leading the euro to appreciate by between 2-3% against the dollar since the beginning of 2014 and putting a crimp in European exports. Further, Europe’s flirtation with deflation increases the real burden on debtors. During inflationary times, debtors are able to repay their debts in money that is losing its value; deflation forces debtors to repay in money that is gaining in value.

The European economy is improving. But several indicators show that plenty can still go wrong. So let’s not stop worrying yet.

Richard S. Grossman is Professor of Economics at Wesleyan University and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. He is the author of WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them and Unsettled Account: The Evolution of Banking in the Industrialized World since 1800. His homepage is RichardSGrossman.com, he blogs at UnsettledAccount.com, and you can follow him on Twitter at @RSGrossman. You can also read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Graph courtesy of Richard Grossman. Used with permission.

The post Can we finally stop worrying about Europe? appeared first on OUPblog.