new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Nine Economic Policy Disasters, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Nine Economic Policy Disasters in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 1/7/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Wrong,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

Nine Economic Policy Disasters,

Richard S. Grossman,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act 2015,

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act,

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act,

risky securities,

What We Can Learn from Them,

Add a tag

Burdensome, costly, and—let’s face it—just plain stupid government regulation is all around us. And even well-meaning, reasonably well-designed regulations can impose costs all out of proportion with their benefits.

Consider the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) (20 U.S.C. § 1232g; 34 CFR Part 99), a Federal law that has the admirable goal of protecting the privacy of student education records. My colleagues and I were recently informed by university officials that we may no longer leave corrected student assignments in a public place for them to pick up, because such materials are part of a student’s confidential record.

This would be a sensible rule if it applied only to exams, term papers, or other major assignments. However, the rule also applies to homework assignments which account for a trivial portion of a student’s actual course grade and are mostly just checked for completion. We will most likely devise a time-consuming work-around: generating random code numbers for each student and using those code numbers in place of names on all of their assignments. The alternative would be to return each problem set individually which, in a class of 100 students, would take too much time away from teaching and learning.

Making fun of these regulations, the politicians who make them, and the regulators and lawyers who make sure that they are adhered to is good sport—and the only compensation we get for putting up with them. Our distain for bad regulations, however, should not get in the way of recognizing that there are also good regulations.

Sadly, one of the good regulations—contained in section 716 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act 2010–was the victim of the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act 2015, the trillion dollar spending bill signed into law by President Obama on 16 December 2014 in order to keep the US government running for a few more months.

Dodd-Frank was passed in the aftermath of the US subprime crisis. The text of the law is 848 pages long and contains a large number of provisions—some good, some bad, and some that have not yet been implemented. Section 716 of the law regulates “swaps,” one of the risker types of derivative securities which played an important role in the subprime meltdown. Known as the “Swap Push-out Rule,” section 716 prohibited institutions that dealt in these securities from receiving “federal assistance,” including advances from the Federal Reserve or FDIC insurance or guarantees.

In other words, if your institution got into trouble by dealing in these very risky securities, the feds would not bail you out with taxpayer money. Further, you could not pay for these securities by using money that you held—at very low cost–by taking federally insured deposits. Under section 716, banks had to “push out” these derivative out to affiliated—but uninsured—firms.

There has been a fair bit of fallout since the rule was revised. It has been alleged that the wording—originally contained in legislation passed by the House (but defeated in the Senate) last year—was written by bank lobbyists, in particular those on Citigroup’s payroll. Few lawmakers have been standing up to take credit for the latest attempt to revise section 716, although former Fed chair Ben Bernanke is on record as having supported some alteration to the regulation. Opponents of the revision come from the right and left, and include Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), David Vitter (R-LA), and Sherrod Brown (D-OH). The White House opposed the measure, as did the Vice Chair of the Federal Deposit Corporation, former Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City President Thomas Hoenig.

The amendment of section 716 is bad news for America’s future financial stability and the American taxpayer. Banks will now be able to use low-cost federally insured deposits to engage in risky swap transactions. And, when these transactions land them in trouble, they will be able to turn to the federal government to bail them out.

The problems generated by the revision of section 716 of Dodd-Frank can be reversed. All that is needed is for the authorities to force institutions that deal in these swap transactions to back them with enough capital to ensure that bank shareholders–and not taxpayers—will pay the price if the transactions sour. Given Congress’s willingness to throw section 716 overboard, such a reform is extremely unlikely.

Headline image credit: Money falling. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post One regulation too few appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 5/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

spreads,

Wrong,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

Nine Economic Policy Disasters,

Richard S. Grossman,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

European economy,

European sovereign debt crisis,

German government,

debtors,

deflation,

fiscally,

grossman,

merkel,

governments’,

Books,

Economics,

Current Affairs,

angela,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

Because Europe accounts for nearly a quarter of the world’s economic output, this question is important not only to Europeans, but to Africans, Asians, Americans (both North and South), and Australians as well. Those who forecast that the United States’s relatively anemic five-year-old recovery is poised to become stronger almost always include the caveat “unless, of course, Europe implodes.”

So, can we stop worrying about Europe?

Recent signs have been encouraging.

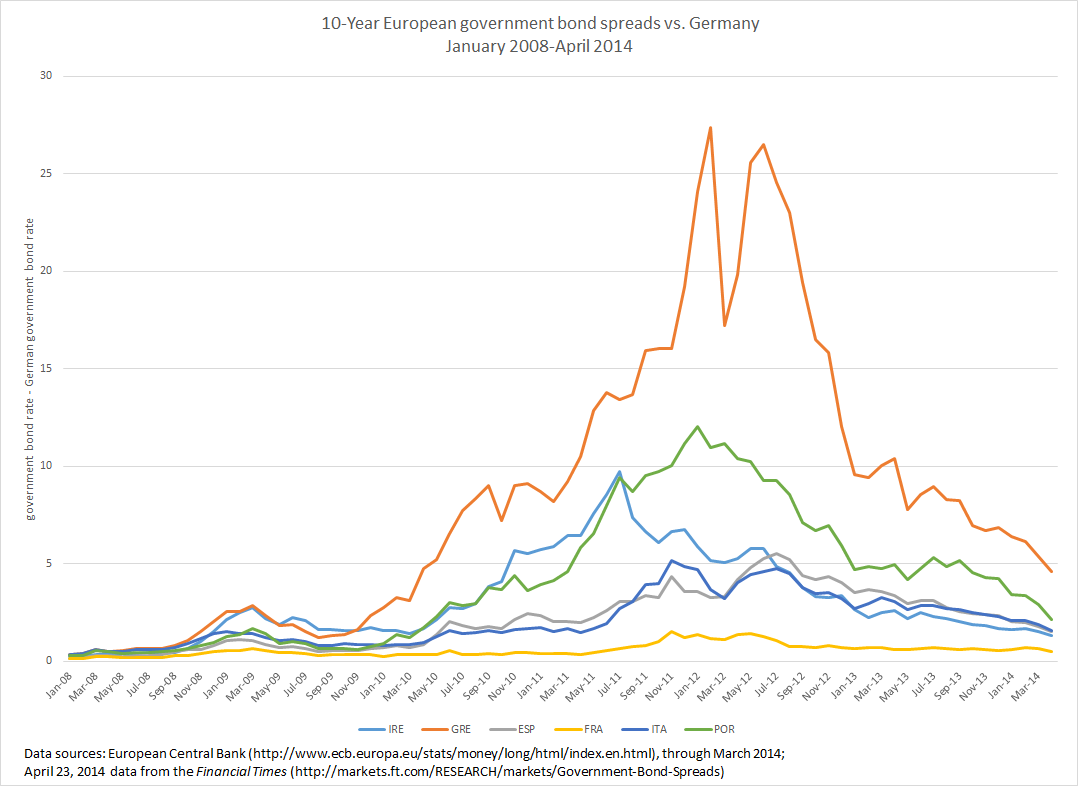

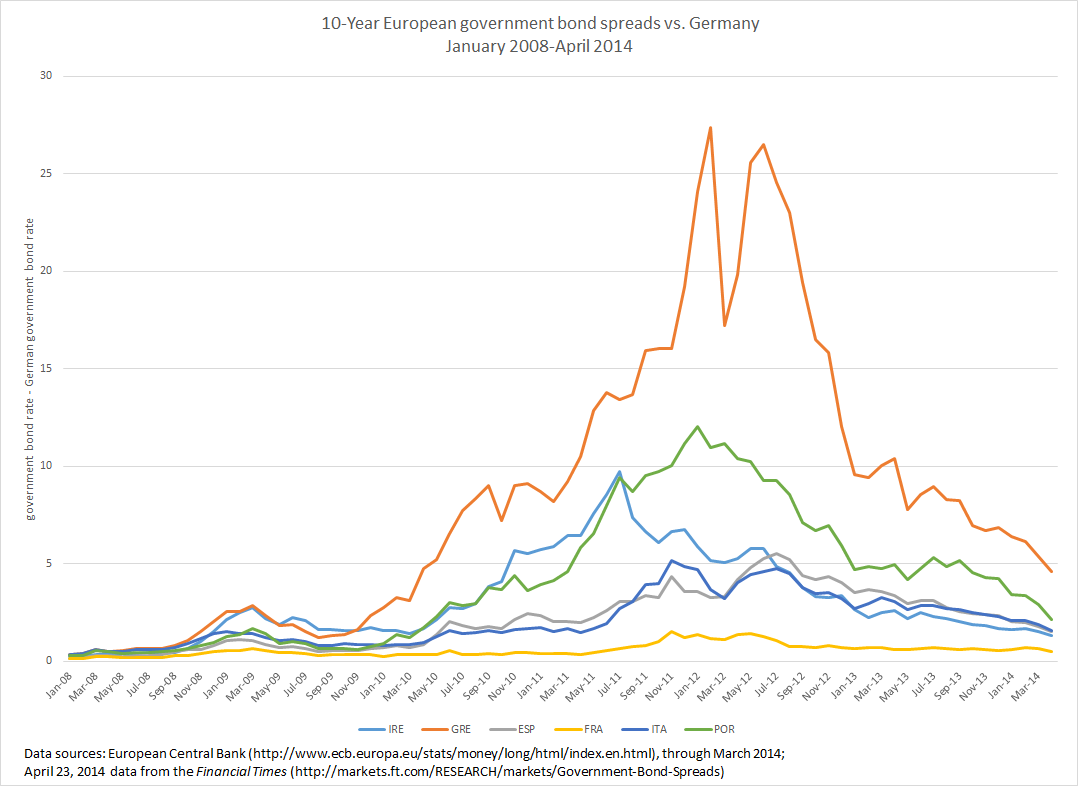

Consider the following graph, which shows the spread between the yields on the 10-year bonds of several European countries and those of the German government. Because the German government’s finances are relatively healthy—and Germany is thus viewed as being quite likely to pay back what it owes—it is able to borrow money more cheaply than most of its neighbors. For 10 years loans, the German government pays interest of about 1.5%, which is among the lowest rates in Europe.

Before the European sovereign debt crisis erupted 2009, spreads were not especially wide. In 2008, the Greek government paid between 0.25-0.75% more to borrow money for 10 years than the German government. When the sorry state of the Greek government’s finances became public, however, the spread between Greek and German yields soared to more than 20% and the European Union (EU) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were called in to bail out the Greek government. Ireland, Portugal, and Spain also received rescue packages (as did Cyprus), while Italy appeared to be headed down the same road. Note the wide spreads between these governments’ borrowing costs and those of the fiscally virtuous Germans.

During the last year or so, Greek, Irish, Portuguese, and Spanish spreads have shrunk considerably — not to their pre-crisis levels, but far below their sky-high levels of 2010-2012 — suggesting that doubts about the sustainability of European governments’ debts is receding. The decline in spreads is due in part to the austerity measures adopted as a condition of the EU/IMF bailouts, which have improved the budget outlook among the fiscally weaker countries. German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s April visit to Greece was widely seen as an effort to show support for fiscal austerity and economic restructuring adopted by the Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras.

Angela Merkel – Αντώνης Σαμαράς, 2012. Photo by Αντώνης Σαμαράς Πρωθυπουργός της Ελλάδας. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

In other positive news, Markit’s European purchasing manager’s composite index for March (released on 23 April 2014), which is considered a proxy for economic output, rose to a nearly three-year high. The index shows a continuous expansion of business activity since last July and forecasts that a backlog of work will lead to further growth in May.

Despite these positive signs, Europe is not out of the woods.

Unemployment remains stubbornly high, due, in part, to austerity: over 25% in Greece and Spain; over 15% in Portugal and Cyprus; and over 10% in France, Ireland, Italy, and a number of other countries.

Although prices are rising slightly in the European Union on average, Greece, Spain, Portugal and a few other European countries are experiencing deflation. Moreover, overall inflation in the EU is below that in the United States, leading the euro to appreciate by between 2-3% against the dollar since the beginning of 2014 and putting a crimp in European exports. Further, Europe’s flirtation with deflation increases the real burden on debtors. During inflationary times, debtors are able to repay their debts in money that is losing its value; deflation forces debtors to repay in money that is gaining in value.

The European economy is improving. But several indicators show that plenty can still go wrong. So let’s not stop worrying yet.

Richard S. Grossman is Professor of Economics at Wesleyan University and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. He is the author of WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them and Unsettled Account: The Evolution of Banking in the Industrialized World since 1800. His homepage is RichardSGrossman.com, he blogs at UnsettledAccount.com, and you can follow him on Twitter at @RSGrossman. You can also read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Graph courtesy of Richard Grossman. Used with permission.

The post Can we finally stop worrying about Europe? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 4/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Wrong,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

sanctions,

Crimea,

Nine Economic Policy Disasters,

Richard S. Grossman,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

economic sanctions,

Russian energy sector,

sector—energy,

Books,

Politics,

Current Affairs,

nato,

Ukraine,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

Russia’s seizure of Crimea from Ukraine has left its neighbors—particularly those with sizable Russian-speaking populations such as Kazakhstan, Latvia, Estonia, and what is left of Ukraine—looking over their shoulder wondering if they are next on Vladimir Putin’s list of territorial acquisitions. The seizure has also left Europe and United States looking for a coherent response.

Neither the Americans nor the Europeans will go to war over Crimea. Military intervention would be costly, unpopular at home, and not necessarily successful. Unless a fellow member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (which includes Latvia and Estonia) were attacked by Russia, thereby requiring a military response under the terms of the NATO treaty, the West will not go to war to check Putin’s land grabs.

Neither the Americans nor the Europeans will go to war over Crimea. Military intervention would be costly, unpopular at home, and not necessarily successful. Unless a fellow member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (which includes Latvia and Estonia) were attacked by Russia, thereby requiring a military response under the terms of the NATO treaty, the West will not go to war to check Putin’s land grabs.

So far, the West’s response—aside from harsh rhetoric—has been economic, not military. Both the United States and Europe have imposed travel and financial sanctions on a handful of close associates of Putin (which have had limited effect), with promises of escalation should Russia continue on its expansionist path.

What is the historical record on sanctions? And what are the chances for success if the West does escalate?

The earliest known use of economic sanctions was Pericles’s Megarian decree, enacted in 432 BCE, in which the Athenian leader “…banished [the Megarians] both from our land and from our markets and from the sea and from the continent” (Aristophanes, The Acharnians). The results of these sanctions, according to Aristophanes, was starvation among the Megarians.

Hufbauer, Schott, Elliot, and Oegg (2008) catalogue more than 170 instances of economic sanctions between 1910 and 2000. They find that only about one third of all sanctions efforts were even partially successful, although the success depends critically on the sanction’s goal. Limited goals (e.g. the release of a political prisoner) have been successful about half of the time; more ambitious goals (e.g. disruption of a military adventure, military impairment, regime change, or democratization) are successful between a fifth and a third of the time. Of course, these figures depend crucially on a whole host of additional factors, including the cost borne by the country imposing sanctions, the resilience of the country being sanctioned, and the necessity of international cooperation for the sanctions to be fully implemented.

Despite these cautionary statistics, sanctions can sometimes be effective. According to the US Congressional Research Service, recent US sanctions reduced Iranian oil exports by 60% and led to a decline in the value of the Iranian currency by 50%, forcing Iranian leaders to accept an interim agreement with the United States and its allies in November 2013. On the other hand, US sanctions against Cuba have been in place for more than 50 years and, although having helped to impoverish the island, they have not brought about the hoped for regime change.

Current thinking on sanctions favors what are known as “targeted” or “smart” sanctions. That is, rather than embargoing an entire economy (e.g. the US embargo of Cuba), targeted sanctions aim to hit particular individuals or sectors of the economy via travel bans, asset freezes, arms embargo, etc. Russian human rights campaigner and former World Chess Champion Gary Kasparov suggested in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece that the way to get to Putin through such smart sanctions, writing:

“If the West punishes Russia with sanctions and a trade war, that might be effective eventually, but it would also be cruel to the 140 million Russians who live under Mr. Putin’s rule. And it would be unnecessary. Instead, sanction the 140 oligarchs who would dump Mr. Putin in the trash tomorrow if he cannot protect their assets abroad. Target their visas, their mansions and IPOs in London, their yachts and Swiss bank accounts. Use banks, not tanks.”

If such sanctions were technically and legally possible—and that the expansionist urge comes from Putin himself and would not be echoed by his successor—this could be the quickest and most effective way to solve the problem.

A slower, but nonetheless sensible course is to squeeze Russia’s most important economic sector—energy. Russian energy exports in 2012 accounted for half of all government revenues. Sanctions that restrict Russia’s ability to export oil and gas would deal a devastating blow to the economy, which has already suffered from the uncertainty surrounding Russian intervention in Ukraine. By mid-March the Russian stock market was down over 10% for the year; the ruble was close to its record low against the dollar; and 10-year Russian borrowing costs were nearly 10%–more than 3% higher than those of the still crippled Greek economy—indicating that international lenders are already wary of the Russian economy.

A slower, but nonetheless sensible course is to squeeze Russia’s most important economic sector—energy. Russian energy exports in 2012 accounted for half of all government revenues. Sanctions that restrict Russia’s ability to export oil and gas would deal a devastating blow to the economy, which has already suffered from the uncertainty surrounding Russian intervention in Ukraine. By mid-March the Russian stock market was down over 10% for the year; the ruble was close to its record low against the dollar; and 10-year Russian borrowing costs were nearly 10%–more than 3% higher than those of the still crippled Greek economy—indicating that international lenders are already wary of the Russian economy.

A difficulty in targeting the Russian energy sector—aside from the widespread pain imposed on ordinary Russians–is that the Europeans are heavily dependent on it, importing nearly one third of their energy from Russia. Given the precarious position of its economy at the moment, an energy crisis is the last thing Europe needs. Although alternative energy sources not will appear overnight, old and new sources could eventually fill the gap, including greater domestic production and rethinking Germany’s plans to close its nuclear plants. Loosening export restrictions on the now-booming US natural gas industry would provide yet another alternative energy source to Europe and increase the effectiveness of sanctions. Freeing the industrialized world from dependence on dictators to fulfill their energy needs can only help the West’s long-term growth prospects and make it less susceptible to threats from rogue states.

If we are patient, squeezing Russia’s energy sector might work. In the short run, however, sanctioning the oligarchs may be the West’s best shot.

Richard S. Grossman is Professor of Economics at Wesleyan University and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. He is the author of WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them and Unsettled Account: The Evolution of Banking in the Industrialized World since 1800. His homepage is RichardSGrossman.com, he blogs at UnsettledAccount.com, and you can follow him on Twitter at @RSGrossman. You can also read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Vladimir Putin. Russian Presidential Press and Information Office. CC BY 3.0 by kremlin.ru. (2) Abrakupchinskaya oil exploration drilling rig in Evenkiysky District. Photo by ShavPS. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia.

The post The economics of sanctions appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 3/5/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Economics,

Technology,

Current Affairs,

currencies,

Wrong,

*Featured,

Books,

Business & Economics,

Nine Economic Policy Disasters,

Richard S. Grossman,

bitcoin,

commercial transaction fees,

gold standard,

online currency,

plan—bitcoin,

bitcoincharts,

bitcoin—or,

bitcoin’s,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

Within months of being introduced in 2009, enthusiasts were hailing bitcoin, the digital currency and peer-to-peer payment system, as the successor to the dollar, euro, and yen as the world’s most important currency.

The collapse of the Mt. Gox bitcoin exchange last month has dulled some of the enthusiasm for the online currency. According to bitcoincharts.com, the price of bitcoin, which had peaked at over $1100 in December, tumbled to about half of that in the wake of the Mt. Gox failure, leading a number of commentators to suggest that bitcoin is finished.

Others remain bullish on the currency, arguing that the collapse will lead to greater scrutiny of the system and the reemergence of a stronger, more secure bitcoin. Although the price of bitcoin has declined since the Mt. Gox collapse and volatility remains high, rallies are not unheard of. On 3 March 2014, for example, bitcoin began the day trading around $580 and peaked at over $700 before falling back into the upper $600s (data from bitcoincharts.com).

I have argued elsewhere that if bitcoin were to replace the leading world currencies, the results would be catastrophic. The most important objection is that—when it works according to plan—bitcoin mimics the gold standard. The total number of bitcoins that can be created (“mined” in bitcoin terminology, just to maintain the image of gold) is fixed and cannot be altered. Adopting a bitcoin standard would make it virtually impossible for central bankers to undertake aggressive monetary measures—as the Fed and European Central Bank have done—to bolster a flagging economy and a financial system on the point of collapse.

Another public policy downside of bitcoin is that because it is peer-to-peer, without a centralized monitoring authority, it allows funds to be transferred away from the prying eyes of government. This famously came to light last fall when the on-line drug bazaar Silk Road—which conducted much of its business in bitcoin–was shut down by the FBI and its proprietor arrested on drug and computer charges. Needless to say, the attractiveness of a payments system like bitcoin to criminals and terrorists should dampen the fervor of even the most enthusiastic bitcoin devotee.

Is there anything to like about bitcoin?

Yes. Bitcoin—or, more precisely, a system with some of bitcoin’s attributes—would give a boost to commerce.

Moving money with bitcoin is cheaper than using PayPal, credit cards, or bank transfers, all of which charge one or both parties fees. The savings on international transactions are even greater, since these transactions, when carried out with traditional currencies, typically involve both higher fees for moving the money as well as additional charges for converting form one currency to another. Denominating the transaction in bitcoin eliminates the currency conversion fee altogether.

Eliminating fees associated with commercial transactions is the most compelling argument in favor of bitcoin, as anyone who has ever used a credit card overseas, tried to transfer money, or used an out-of-network ATM will attest. The disadvantages of bitcoin far outweigh its benefits. Still, its ability to facilitate cheaper trade is appealing. The sooner someone figures out how to adopt that aspect of bitcoin for safer, more adaptable traditional currencies, the better for all of us.

Richard S. Grossman is Professor of Economics at Wesleyan University and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. He is the author of WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them and Unsettled Account: The Evolution of Banking in the Industrialized World since 1800. His homepage is RichardSGrossman.com, he blogs at UnsettledAccount.com, and you can follow him on Twitter at @RSGrossman. You can also read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bitcoin banknote by CASASCIUS. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Something to like about bitcoin appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 9/4/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Economics,

Current Affairs,

Finance,

conspiracy,

Wrong,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

LIBOR,

monetary policy,

Nine Economic Policy Disasters,

regulatory enforcement,

Richard S. Grossman,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

The public has been so fatigued by the flood of appalling economic news during the past five years that it can be excused for ignoring a scandal involving an interest rate that most people have never heard of. In fact, the Libor scandal is potentially a bigger threat to capitalism than the stories that have dominated the financial headlines, such as the subprime meltdown, the euro-zone crisis, the Madoff scandal, and the MF Global bankruptcy.

It’s not surprising that Libor has generated less interest than these other stories. It has left neither widespread financial turmoil nor bankrupt celebrities in its wake. It took place largely outside of the United States, further rendering the American media and public more disinterested. It involves technical issues that induce sleep in even the most hard-bitten financial correspondents.

Yet, despite its lower profile, the Libor scandal is potentially more serious than any other financial catastrophe in recent memory.

The subprime crisis can be blamed on poor government management: irresponsible fiscal policy combined with loose monetary policy and poor regulatory enforcement. The euro crisis resulted from one poorly conceived idea: creating one currency when retaining 17 distinct currencies would have been better. The Madoff and MF Global debacles can be chalked up to a few isolated unscrupulous and reckless individuals.

By contrast, the Libor scandal was nothing less than a conspiracy in which a group of shadowy bankers conspired against the majority of participants in the financial system—that is, you and me. And therein lies the danger.

Libor is the acronym for the London InterBank Offered Rate. Previously produced for the British Bankers’ Association, it was calculated by polling between six and 18 large banks daily on how much it cost them to borrow money. The highest and lowest estimates were thrown out and the remainder—about half–were averaged to yield Libor.

Libor plays a vital role in the world financial system because it serves as a benchmark for some $800 trillion in financial contracts–everything ranging from complex derivative securities to more mundane transactions like credit card interest rates and adjustable rate home mortgages.

Since so much money rides on Libor, banks have an incentive to alter submissions to improve their profitability: raising submissions when they are net lenders; lowering them when they are net borrowers. Even small movements in Libor can lead to millions in extra profits–or losses.

Financial conspiracy theories are about as commonplace–and believable–as those on the Kennedy assassination and the Lindbergh kidnapping. This time, however, emails have surfaced proving that banks colluded on their Libor submissions. In one email, a grateful trader at Barclays bank thanked a colleague who altered his Libor submission at the trader’s behest: “Dude. I owe you big time! Come over one day after work and I’m opening a bottle of Bollinger.”

Unfortunately, efforts to reform Libor have been insufficient.

In July British authorities granted a contract to produce the Libor index to NYSE Euronext, the company that owns the New York Stock Exchange, the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange, and a number of other stock, bond, and derivatives exchanges. In other words, the company that will be responsible for making sure that Libor is set responsibly and fairly will be in a position to reap substantial profits from even the slightest movements in Libor. Like putting foxes in charge of the chicken coop, this is a recipe for disaster.

The financial system’s role is to channel the accumulated savings of society to projects where they can do the most economic good—a process known as intermediation. My retirement savings may help finance the construction of a new factory; yours might help someone pay for a new house. Although Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein exaggerated when he called this function “Doing God’s work,” intermediation is nonetheless a vital function.

Intermediation will come screeching to a halt if individuals, corporations, and governments no longer trust the financial system with their savings. Those who believe that the interest rates they pay and receive are the result of a game that is rigged will just opt out. They may not go so far as to stash their savings under their mattresses, but they will certainly keep it away from the likes of bankers they believe have been cheating them. Instead they will hold it in cash or in government bonds which will reduce the amount of money available for productive purposes. The consequences for the economy will be severe.

Rather than handing Libor over to a firm with a conflict of interest, the British government should announce that a year from now, Libor will cease to exist. How would markets react to the disappearance of Libor? The way markets always do. They would adapt.

Financial firms will have a year to devise alternative benchmarks for their floating rate products. Given the low repute in which Libor—and the people responsible for it—are held, it would be logical for one or more publicly observable, market-determined (and hence, not subject to manipulation) interest rates to take the place of Libor as currently constructed.

Only by making this important benchmark rate determined in a transparent manner can faith be restored in it.

Richard S. Grossman is Professor of Economics at Wesleyan University and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. He is the author of WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them and Unsettled Account: The Evolution of Banking in the Industrialized World since 1800.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Stacks of coins with the letters LIBOR isolated on white background. © joxxxxjo via iStockphoto.

The post The trouble with Libor appeared first on OUPblog.

Neither the Americans nor the Europeans will go to war over Crimea. Military intervention would be costly, unpopular at home, and not necessarily successful. Unless a fellow member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (which includes Latvia and Estonia) were attacked by Russia, thereby requiring a military response under the terms of the NATO treaty, the West will not go to war to check Putin’s land grabs.

Neither the Americans nor the Europeans will go to war over Crimea. Military intervention would be costly, unpopular at home, and not necessarily successful. Unless a fellow member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (which includes Latvia and Estonia) were attacked by Russia, thereby requiring a military response under the terms of the NATO treaty, the West will not go to war to check Putin’s land grabs. A slower, but nonetheless sensible course is to squeeze Russia’s most important economic sector—energy.

A slower, but nonetheless sensible course is to squeeze Russia’s most important economic sector—energy.