new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Story Design, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 15 of 15

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Story Design in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/8/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Novel Structure,

Three Act Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Plots,

Alternative Structures,

Designing Principle,

Classical Design,

Add a tag

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

Happy plotting, structuring, and designing, everyone!

Organic Architecture Series:

Classic Design and Arch Plot:

Alternative Plots:

Alternative Structures:

Designing Principle:

Full Bibliography for this Series:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Anderson, Tobin. “Theories of Plot and Narrative.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt Inc., 1927.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Hawes, Louise. “Desire Is the Cause of All Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Kaufman, Charlie. “Charlie Kaufman: BAFTA Screenwriting Lecture Transcript.” BAFTA Guru. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 30 Sept. 2011. Web. 18 Aug. 2012.

Larios, Julie. “Once or Twice Upon a Time or Two: Thoughts on Revisionist Fairy Tales.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Layne, Ron and Rick Lewis. “Plot, Theme, the Narrative Arc, and Narrative Patterns.” English and Humanities Department. Sandhill Community College. 11 Sept, 2009. Web. 7 May 2011.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007. McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Sibson, Laura. “Structure Serving Story: A Discussion of Alternating Narrators in Today’s Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Tobias, Ron. Twenty Master Plots: And How to Build Them. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1993.

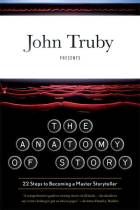

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/8/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Plot Structure,

Novel Structure,

Three Act Structure,

The Hero's Journey,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Plots,

Alternative Structures,

Designing Principle,

Classical Design,

Add a tag

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

Happy plotting, structuring, and designing, everyone!

Organic Architecture Series:

Classic Design and Arch Plot:

Alternative Plots:

Alternative Structures:

Designing Principle:

Full Bibliography for this Series:

Alderson, Martha. The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master. New York: Adams Media, 2011.

Anderson, Tobin. “Theories of Plot and Narrative.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Critical Thesis. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Bayerl, Katie. “Must We All Be Heroes? Crafting Alternatives to the Hero’s Journey in YA Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. July 2009.

Bechard, Margaret. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2008.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narative Craft. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 2011.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Second Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster: Vetting the Verse Novel.” The Horn Book Magazine. Sept.-Oct.2004: 611-616.

Capetta, Amy Rose. “Can’t Fight This Feeling: Figuring out Catharsis and the Right One for Your Story.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier, VT. Jan 2012.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Chapman, Harvey. “Not Your Typical Plot Diagram.” Novel Writing Help. 2008-2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2012.

Chea, Stephenson. “What’s the Difference Between Plot and Structure.” Associated Content. 16 Feb. 2010. Web. 7 May 2011.

Doan, Lisa. “Plot Structure: The Same Old Story Since Time Began?” Critical Essay. Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2006.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Revised ed. New York: Delta, 2005.

Fletcher, Susan. “Structure as Genesis.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt Inc., 1927.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Gulino, Paul. Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Hauge, Michael. Writing Screenplays That Sell. New York: Collins Reference, 2001.

Hawes, Louise. “Desire Is the Cause of All Plot.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2008.

Kalmar, Daphne. “The Short Story Cycle: A Sculptural Aesthetic.” Critical Thesis, Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2009.

Kaufman, Charlie. “Charlie Kaufman: BAFTA Screenwriting Lecture Transcript.” BAFTA Guru. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 30 Sept. 2011. Web. 18 Aug. 2012.

Larios, Julie. “Once or Twice Upon a Time or Two: Thoughts on Revisionist Fairy Tales.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Layne, Ron and Rick Lewis. “Plot, Theme, the Narrative Arc, and Narrative Patterns.” English and Humanities Department. Sandhill Community College. 11 Sept, 2009. Web. 7 May 2011.

Lefer, Diane. “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure.” Words Overflown by Stars. Ed. David Jauss, Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2009. 62-69.

Marks, Dara. Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc. Ojai: Three Mountain Press, 2007. McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

McManus, Barbara F. Tools for Analyzing Prose Fiction. College of New Rochelle, Oct. 1998. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Schmidt, Victoria Lynn. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Sibson, Laura. “Structure Serving Story: A Discussion of Alternating Narrators in Today’s Fiction.” Graduate Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. July 2012.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2005.

Tanaka, Shelley. “Books from Away: Considering Children’s Writers from Around the World.” Faculty Lecture. Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montpelier, VT. Jan 2010.

Tobias, Ron. Twenty Master Plots: And How to Build Them. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1993.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

TV Tropes. Three Act Structure. TV Tropes Foundation, 26 Dec. 2011. Web. 11. Sept. 2012.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 2nd Edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

Williams, Stanley D. The Moral Premise. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2006.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/5/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Plot,

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Classic Design,

Goal Oriented Plot,

Designing Principle,

Mountain Structure,

Add a tag

I’ve spent the last two months talking all about classical design, alternative structures and plots, and designing principles! Hopefully you’ve seen that there are innumerable design possibilities at your fingertips. But as I walked us through this series, I’m sure a few of you read my posts and thought to yourself: Doesn’t that story fit into multiple types of structure? For example, as I explained that The Godfather uses a fairy-tale structure, you might have been thinking: But Ingrid, it also uses the mountain structure!

I’ve spent the last two months talking all about classical design, alternative structures and plots, and designing principles! Hopefully you’ve seen that there are innumerable design possibilities at your fingertips. But as I walked us through this series, I’m sure a few of you read my posts and thought to yourself: Doesn’t that story fit into multiple types of structure? For example, as I explained that The Godfather uses a fairy-tale structure, you might have been thinking: But Ingrid, it also uses the mountain structure!

To which I’d say: You’re right!

Which brings me to my final point in this series: design and structure are layered. You won’t necessarily pick on design concept and be done.

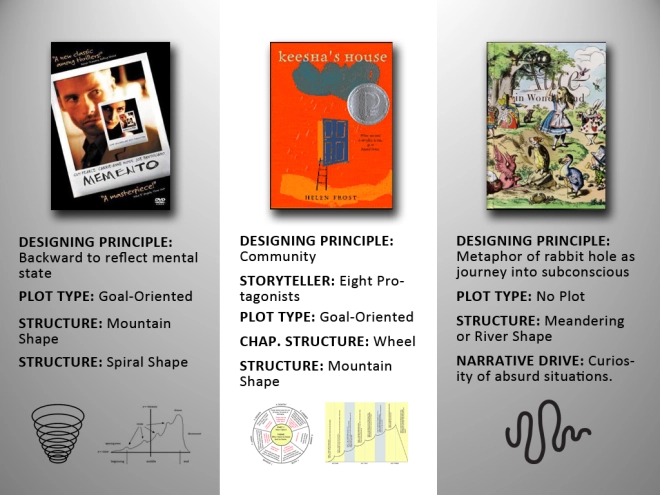

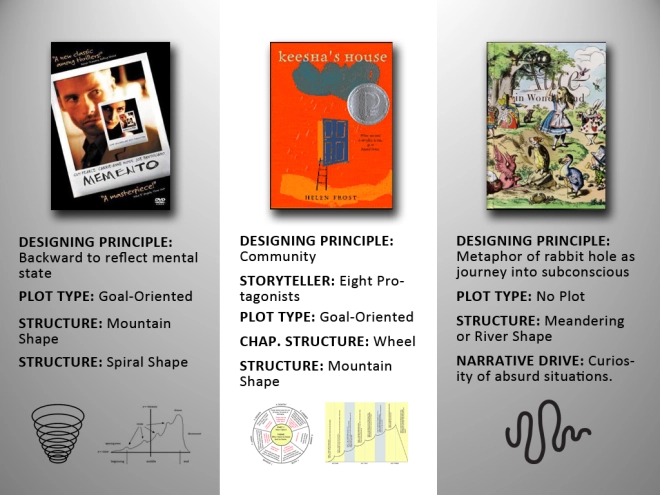

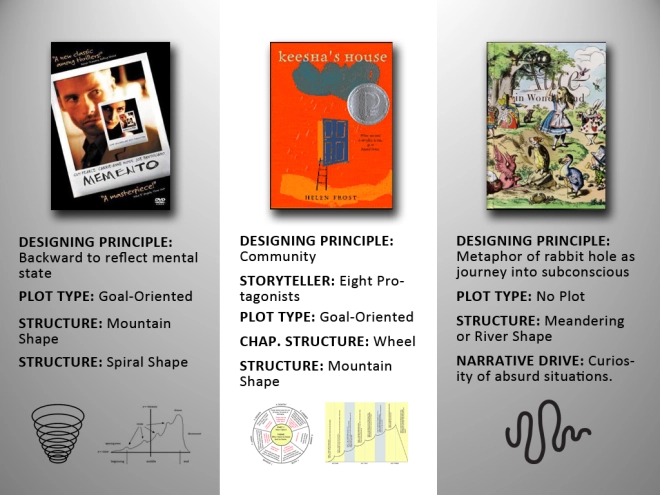

In the film Memento, the designing principle uses a backwards structure to reflect short term memory. But it also has a goal-oriented plot and a mountain structure. Only the major structural beats are flipped. If the story was told forward, what would be considered the inciting incident becomes the climax when it’s told backwards. Additionally, because the story revisits events of the past, again and again, you could also consider this movie to have a spiral structure.

Helen Frost’s novel Keesha’s House is also layered. It’s told with eight protagonists as a portrait of a community and each chapter uses a wheel structure to unify the characters through a theme. But the structure of the whole novel still uses a mountain escalation as each chapter introduces new obstacles. It’s also a goal-oriented plot: to find a safe place to live.

Stories are layered. And you may find, like me, that the story you’re trying to tell doesn’t fit easily into a three act structure or the hero’s journey. Or maybe it does. And it’s okay if it does. Just make sure that’s a choice you’ve made because it’s right for your story.

Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman said in a lecture to the British Film Academy that “there’s no template for a screenplay, or there shouldn’t be. There are at least as many screenplay possibilities as there are people who write them. Don’t let anyone tell you what a story is, what it needs to include or what form it must take.”

Only you know how to tell your story and only you know how to design it.

Thanks for reading this series!

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 8/5/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Plot,

Writing Craft,

Structure,

Story Structure,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Classic Design,

Goal Oriented Plot,

Designing Principle,

Mountain Structure,

Add a tag

I’ve spent the last two months talking all about classical design, alternative structures and plots, and designing principles! Hopefully you’ve seen that there are innumerable design possibilities at your fingertips. But as I walked us through this series, I’m sure a few of you read my posts and thought to yourself: Doesn’t that story fit into multiple types of structure? For example, as I explained that The Godfather uses a fairy-tale structure, you might have been thinking: But Ingrid, it also uses the mountain structure!

I’ve spent the last two months talking all about classical design, alternative structures and plots, and designing principles! Hopefully you’ve seen that there are innumerable design possibilities at your fingertips. But as I walked us through this series, I’m sure a few of you read my posts and thought to yourself: Doesn’t that story fit into multiple types of structure? For example, as I explained that The Godfather uses a fairy-tale structure, you might have been thinking: But Ingrid, it also uses the mountain structure!

To which I’d say: You’re right!

Which brings me to my final point in this series: design and structure are layered. You won’t necessarily pick on design concept and be done.

In the film Memento, the designing principle uses a backwards structure to reflect short term memory. But it also has a goal-oriented plot and a mountain structure. Only the major structural beats are flipped. If the story was told forward, what would be considered the inciting incident becomes the climax when it’s told backwards. Additionally, because the story revisits events of the past, again and again, you could also consider this movie to have a spiral structure.

Helen Frost’s novel Keesha’s House is also layered. It’s told with eight protagonists as a portrait of a community and each chapter uses a wheel structure to unify the characters through a theme. But the structure of the whole novel still uses a mountain escalation as each chapter introduces new obstacles. It’s also a goal-oriented plot: to find a safe place to live.

Stories are layered. And you may find, like me, that the story you’re trying to tell doesn’t fit easily into a three act structure or the hero’s journey. Or maybe it does. And it’s okay if it does. Just make sure that’s a choice you’ve made because it’s right for your story.

Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman said in a lecture to the British Film Academy that “there’s no template for a screenplay, or there shouldn’t be. There are at least as many screenplay possibilities as there are people who write them. Don’t let anyone tell you what a story is, what it needs to include or what form it must take.”

Only you know how to tell your story and only you know how to design it.

Thanks for reading this series!

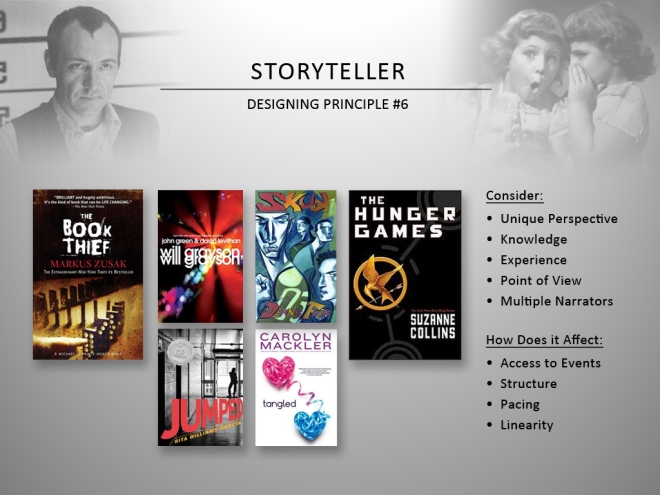

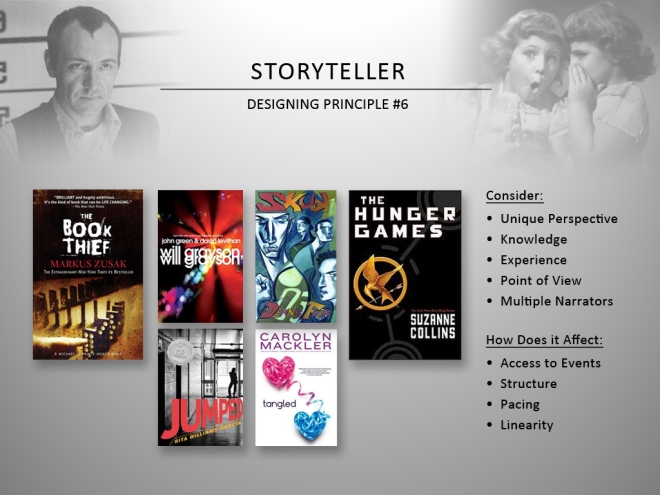

The final category in my series on designing principles is the storyteller.

Who is your novel’s storyteller?

At the outset, it might not seem like the point-of-view or the narrator you chose to tell your story would have a large impact on its structure, but it does. Imagine if how differently the The Usual Suspects would be if it wasn’t told from the POV of Kevin Spacey’s character sitting in a New York City police station. Or imagine how the design of The Book Thief would be different if it wasn’t narrated by death. Or how the structure of The Hunger Games changes when you move out of the first person narration of Katniss’ mind in the book, to the omniscient eye taken in the movie? The choices of what is put where, and why, changes.

Additionally, consider the design effect of having multiple POV narrators as done in the book Will Grayson, Will Grayson which has two narrators, or Jumped which has three, or Tangled which has four, or Keesha’s House which has eight. How does one move from POV to POV? By alternating chapters? By telling the whole story of one and then the whole story of another? Or maybe weighing the POV of one over another?

The storyteller of your book is going to affects it pacing, its linearity, its patterns of repetition, and the breadth of knowledge and experience the storyteller has access to. It has ramifications in all your other design choices and shouldn’t be chosen lightly.

Hopefully, these six categories have helped you to think about how to structure and plot your own novel in a way that is organic, instead of plugging your characters in to a pre-designed template. Have fun exploring all the alternate plots and structures at your fingertips, and remember that using them should come organically from your premise and characters!

I know this has been a long series (thanks for hanging in there with me). I’ve only got a few final notes before wrapping it all up.

Up Next: Structural Layering (because yes, you probably won’t pick one structure and be done!)

Want to know more about designing principles? Try these links:

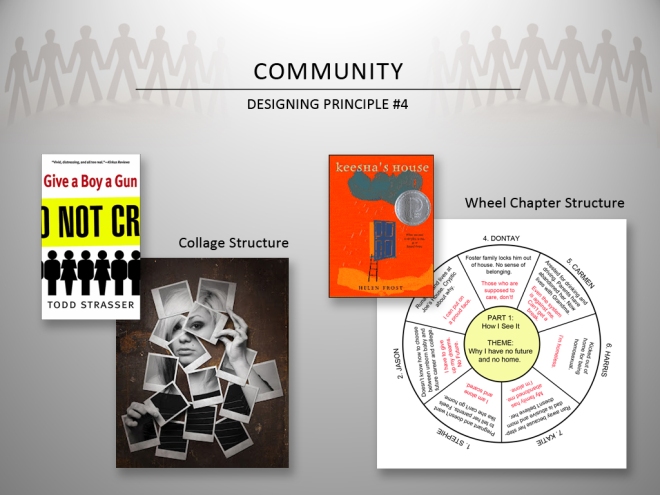

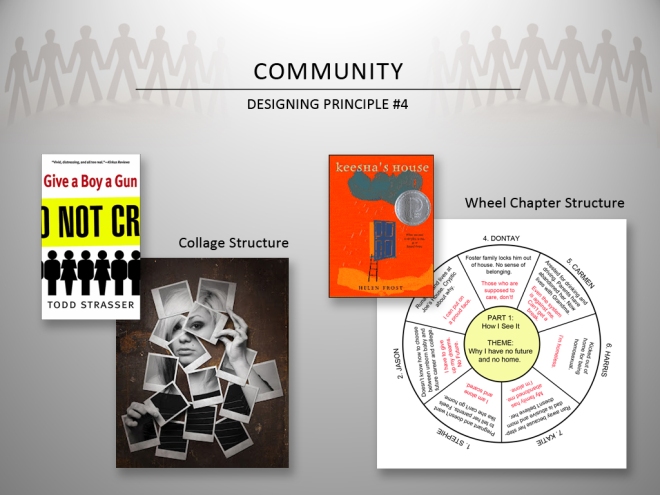

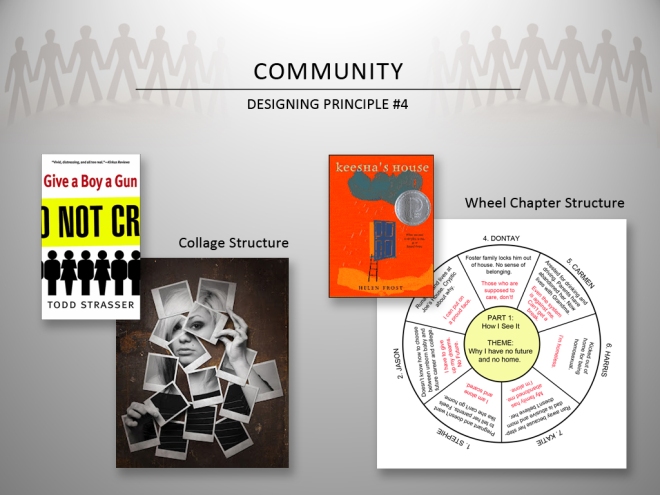

Some stories are not about a single protagonist. Sometimes a group or community becomes the larger focus. Using a community as a designing principle is the fourth category in this series.

Give a Boy a Gun by Todd Struasser explores the complexity of a school shooting and could have been told from POV of the shooter, or a friend of the shooter, or a teacher. Instead Struasser lets an entire community tell this story: friends, parents, teachers, students, etc. In so doing, a portrait of the shooters and the events is constructed by the reader through snippets, interviews, and emails. The structure unveils the fragmentation and chaos of the event itself, and how hard it is to find a single truth of an event or person.

Helen Frost’s verse novel Keesha’s House also creates a portrait of a community, but in a different way. The story follows eight protagonists who become homeless. Each character has his or her own arc, and is given one poem per chapter with which to tell his or her story. Frost’s creates unity between these eight individual stories with the use of a wheel chapter structure. At the core of each chapter is a theme, for example: “Why I can’t live at home,” and each poem of that chapter touches upon the theme in a way that is specific to each character. This structure unites an entire community of abandoned children.

Is your story about a community or ensemble of people? How might you use this to influence the structure of your story?

Up Next: Designing Principle #5 – Parallel Stories and Myth

Want to know more about designing principles? Try these links:

Some stories are not about a single protagonist. Sometimes a group or community becomes the larger focus. Using a community as a designing principle is the fourth category in this series.

Give a Boy a Gun by Todd Struasser explores the complexity of a school shooting and could have been told from POV of the shooter, or a friend of the shooter, or a teacher. Instead Struasser lets an entire community tell this story: friends, parents, teachers, students, etc. In so doing, a portrait of the shooters and the events is constructed by the reader through snippets, interviews, and emails. The structure unveils the fragmentation and chaos of the event itself, and how hard it is to find a single truth of an event or person.

Helen Frost’s verse novel Keesha’s House also creates a portrait of a community, but in a different way. The story follows eight protagonists who become homeless. Each character has his or her own arc, and is given one poem per chapter with which to tell his or her story. Frost’s creates unity between these eight individual stories with the use of a wheel chapter structure. At the core of each chapter is a theme, for example: “Why I can’t live at home,” and each poem of that chapter touches upon the theme in a way that is specific to each character. This structure unites an entire community of abandoned children.

Is your story about a community or ensemble of people? How might you use this to influence the structure of your story?

Up Next: Designing Principle #5 – Parallel Stories and Myth

Want to know more about designing principles? Try these links:

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 7/22/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Story Structure,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Story Structures,

Designing Principle,

Backwards Structure,

Non-Linear Structure,

Time and Design,

Add a tag

We live our lives in a linear progression and that affects the way we think about narrative, how to live our lives, and what we value. Structurally and metaphorically time can be an interesting element to design with. Continuing our discussion on designing principles, lets see how the way we use time can become an organic structural framework.

Backward structures, like the film Memento or Pinter’s play Betrayal become causal mysteries. Charles Ramirez Berg notes that they “draw attention to causal connections, like forward moving structures, but … the narrative fuel is the search for the first cause of known effects.” The play Betrayal begins with a couple’s separation, and as we move back in time, we search for the moment that caused the relationship’s end.

But time can also be chopped up and moved around in any way that serves your story best. In The Time Traveler’s Wife the non-linearity reflects both the premise and unveils the importance of memory to our relationships. In the novel One Day, there’s a linear progression, but each chapter skips forward a year, forcing the reader to fill in the time between. In Groundhog Day and Before I Fall, the protagonists must repeat the same day over and over until they get it right. Even a ticking clock can create a structure; the TV show 24 takes a 24 hour ticking-clock and allots a single episode to each hour.

Does your novel span a day or many years? How does time affect your characters? Is it about looking back, moving forward, or the gaps between? Can the way you slice and dice time reveal another of level of content in your novel and is appropriate for your novel?

Up Next: Designing Principle #4 – Community

Want to know more about designing principles? Try these links:

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 7/22/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Story Structure,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Story Structures,

Designing Principle,

Backwards Structure,

Non-Linear Structure,

Time and Design,

Add a tag

We live our lives in a linear progression and that affects the way we think about narrative, how to live our lives, and what we value. Structurally and metaphorically time can be an interesting element to design with. Continuing our discussion on designing principles, lets see how the way we use time can become an organic structural framework.

Backward structures, like the film Memento or Pinter’s play Betrayal become causal mysteries. Charles Ramirez Berg notes that they “draw attention to causal connections, like forward moving structures, but … the narrative fuel is the search for the first cause of known effects.” The play Betrayal begins with a couple’s separation, and as we move back in time, we search for the moment that caused the relationship’s end.

But time can also be chopped up and moved around in any way that serves your story best. In The Time Traveler’s Wife the non-linearity reflects both the premise and unveils the importance of memory to our relationships. In the novel One Day, there’s a linear progression, but each chapter skips forward a year, forcing the reader to fill in the time between. In Groundhog Day and Before I Fall, the protagonists must repeat the same day over and over until they get it right. Even a ticking clock can create a structure; the TV show 24 takes a 24 hour ticking-clock and allots a single episode to each hour.

Does your novel span a day or many years? How does time affect your characters? Is it about looking back, moving forward, or the gaps between? Can the way you slice and dice time reveal another of level of content in your novel and is appropriate for your novel?

Up Next: Designing Principle #4 – Community

Want to know more about designing principles? Try these links:

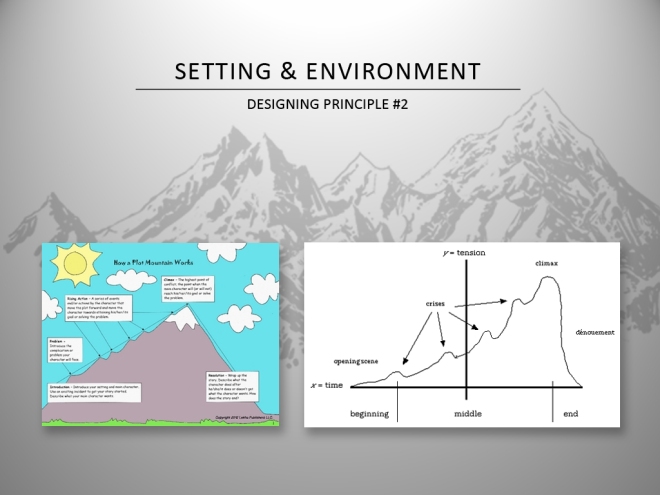

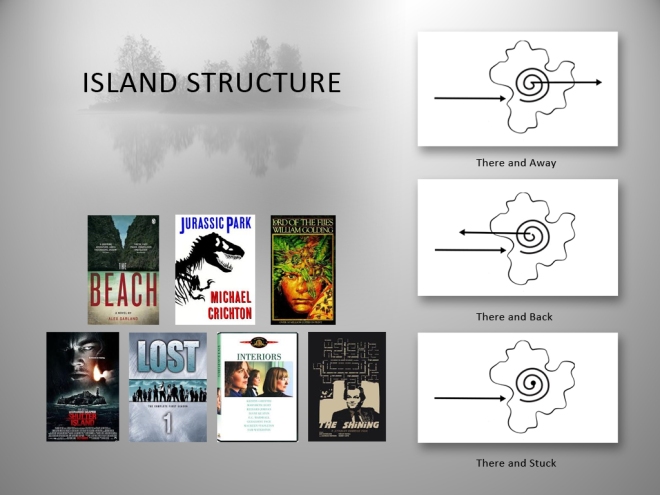

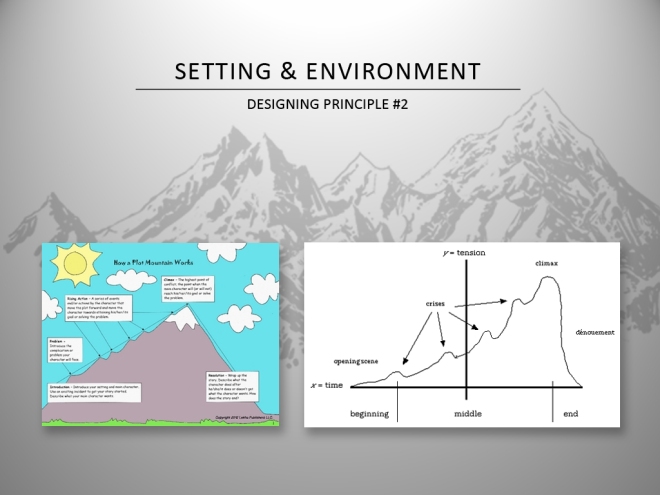

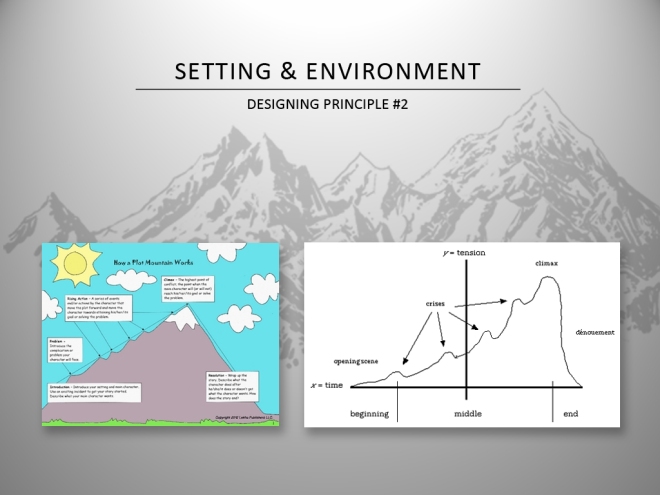

My second category in my series on designing principle is using your setting and environment to as inspiration for your story’s design.

It’s interesting that the predominant structure we talk about is a mountain, which is ultimately a metaphor for a certain kind of movement and escalating energy to a story. In my first post on designing principle I mentioned the river as structure for the Heart of Darkness. Huck Finn is another example of river design and it’s worth noting that both novels have a different rhythm than the mountain structure. They meander more, they’re quieter, they reflect the inherent structure that exists in the novel’s setting.

Let’s consider other environments.

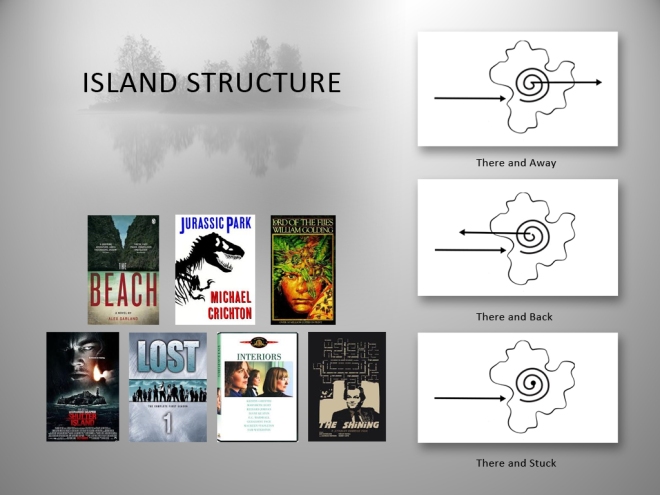

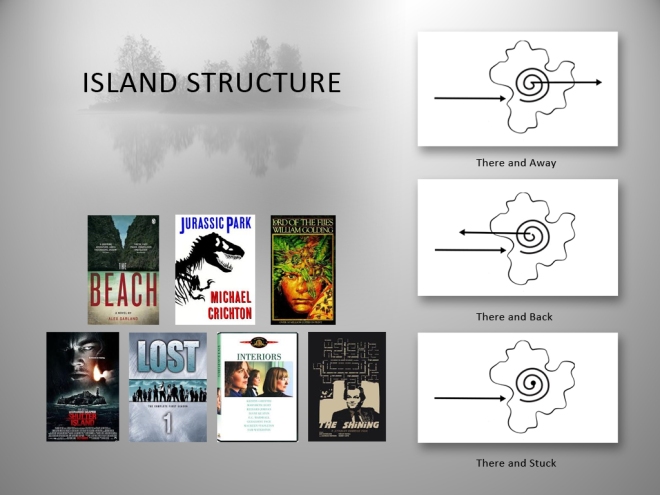

For example: Island Structure.

The initial energy is getting to the island, but once you’ve arrived there is an intense spinning in circles like being lost in a labyrinth. There is a desire to leave the island, but the island won’t let you go. It develops its own rules. In Shutter Island, the island becomes a metaphor for insanity. In Jurassic Park man becomes the rat in a maze of his own experiments. New rules and societies come to exist, as in The Beach, Lord of the Flies, and the TV show Lost. The overall energy is an isolated churning with no way out.

Haunted house stories have a similar structure where the house is the island – or prison – with its own rules, like in The Shining, or The House on Haunted Hill, or even Woody Allen’s dramatic film Interiors where the house is an emotional island isolating its characters.

What about the Ocean?

It has two levels: the surface and the deep. Diving underwater has a different energy than climbing a mountain; the descent becomes increasingly claustrophobic as you get closer to drowning. Whereas the surface is vast and isolating, you can go in any direction, but you must face the wildness of the waves, and the threat of the deep like in Moby Dick and The Perfect Storm.

How about the Forest?

It can be place where you get lost or find magic. In Martine Leavitt’s Keturah and Lord Death the forest becomes an important design element. The forest is death’s realm and the town is the land of the living. The forest’s edge is line upon which Keturah must dance. Initially Keturah is about to die in the forest, but Death gives her a second chance, allowing her to return home. But she’s given tasks and must come back to the forest and revisit Death, creating touch-points in the structure of the story. The story’s rhythm is this undulation between the pull of death and the desire for life.

Think about the environment of your book and ask yourself:

- Does the environment of your book have metaphorical meaning?

- How do your character’s move within it?

- Is it a prison, a path, a portal?

- What natural movement does the environment already provide for your story?

Your story may not be a mountain escalation, but the mountain also provides another good lesson, because you don’t have to be on a mountain to use mountain structure. Look at your environment to see how it might parallel another that you can use an access point to your design.

Up Next: Designing Principle #3 – Time

My second category in my series on designing principle is using your setting and environment to as inspiration for your story’s design.

It’s interesting that the predominant structure we talk about is a mountain, which is ultimately a metaphor for a certain kind of movement and escalating energy to a story. In my first post on designing principle I mentioned the river as structure for the Heart of Darkness. Huck Finn is another example of river design and it’s worth noting that both novels have a different rhythm than the mountain structure. They meander more, they’re quieter, they reflect the inherent structure that exists in the novel’s setting.

Let’s consider other environments.

For example: Island Structure.

The initial energy is getting to the island, but once you’ve arrived there is an intense spinning in circles like being lost in a labyrinth. There is a desire to leave the island, but the island won’t let you go. It develops its own rules. In Shutter Island, the island becomes a metaphor for insanity. In Jurassic Park man becomes the rat in a maze of his own experiments. New rules and societies come to exist, as in The Beach, Lord of the Flies, and the TV show Lost. The overall energy is an isolated churning with no way out.

Haunted house stories have a similar structure where the house is the island – or prison – with its own rules, like in The Shining, or The House on Haunted Hill, or even Woody Allen’s dramatic film Interiors where the house is an emotional island isolating its characters.

What about the Ocean?

It has two levels: the surface and the deep. Diving underwater has a different energy than climbing a mountain; the descent becomes increasingly claustrophobic as you get closer to drowning. Whereas the surface is vast and isolating, you can go in any direction, but you must face the wildness of the waves, and the threat of the deep like in Moby Dick and The Perfect Storm.

How about the Forest?

It can be place where you get lost or find magic. In Martine Leavitt’s Keturah and Lord Death the forest becomes an important design element. The forest is death’s realm and the town is the land of the living. The forest’s edge is line upon which Keturah must dance. Initially Keturah is about to die in the forest, but Death gives her a second chance, allowing her to return home. But she’s given tasks and must come back to the forest and revisit Death, creating touch-points in the structure of the story. The story’s rhythm is this undulation between the pull of death and the desire for life.

Think about the environment of your book and ask yourself:

- Does the environment of your book have metaphorical meaning?

- How do your character’s move within it?

- Is it a prison, a path, a portal?

- What natural movement does the environment already provide for your story?

Your story may not be a mountain escalation, but the mountain also provides another good lesson, because you don’t have to be on a mountain to use mountain structure. Look at your environment to see how it might parallel another that you can use an access point to your design.

Up Next: Designing Principle #3 – Time

Some of you may know that I am obsessed with story structure. If you didn’t know this, please check out my WIP novel structure chart or my collection of story structure diagrams.

Some of you may know that I am obsessed with story structure. If you didn’t know this, please check out my WIP novel structure chart or my collection of story structure diagrams.

It’s no big surprise that I did my VCFA graduate lecture on structure and story design. I love this topic. Thus, I’ve broken down the meat of my lecture into several posts that I will be sharing this month. Thus, I introduce the June blog series: Organic Architecture!

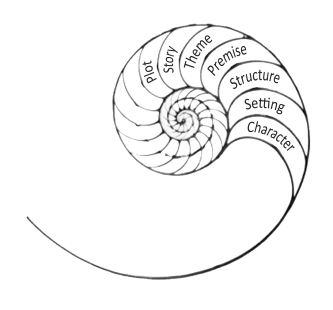

Recently I talked about the difference between literary talent and story talent, and this series is all about developing the story-talent side of a writer’s repertoire. Often we think there is only one way to structure and design a story. Yes, I’m talking about the influence of three-act structure, the hero’s journey, and Aristotle. Well, it turns out these ideas are not the only possibilities, and are actually pretty limiting!

And man, do I get excited when I read quotes like this:

Three act structure and Aristotilean terms (i.e. rising action, climax, denouement) “are so broad and theoretical as to be almost meaningless … they have no practical value for storytellers … [They are] surprisingly narrow … extremely theoretical and difficult to put into practice … Three act structure is hopelessly simplistic and in many ways just plain wrong. ” – John Truby (The Anatomy of Story).

Did John Truby just blow your mind?

Did John Truby just blow your mind?

He blew my mind when I read that quote. So, I set out to see what other options are available for structure and story design. This blog series will give an overview of what I learned on that journey. It will start with three-act structure and the hero’s journey (so we’re all on the same page), and then push to explore the limitations of that structure, and the other options available!

Here’s the blurb for my lecture:

Organic Architecture: Structure, Screenwriting, and Story Design

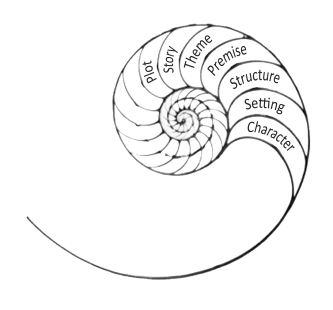

Thanks to American film, you may think that the only way to plot and structure your story is with three acts and a hero’s journey. But do you ever feel limited by this recipe? What if your novel doesn’t even fit into this template? From the point of view of a screenwriter-turned-novelist, this lecture will explore the limitations of classic design, then push into the wild-and-woolly territory of alternative plots and structures. What if you could develop a story design that is unique to your novel, and arises organically from its premise, characters, setting, and themes? Unchain yourself from formulaic storytelling and see how many options are really at your fingertips! Familiarity with the film Toy Story is suggested. Core Topics: Plot/Structure, Writing Process, Character, Theme.

Please stay tuned for this exciting blog series which will cover:

- Arch Plot and Classic Design

- The Limitations of Classic Design

- Alternative Plot Types

- Alternative Story Structures

- Designing Principals

- Finding Your Stories Organic Architecture

Some of you may know that I am obsessed with story structure. If you didn’t know this, please check out my WIP novel structure chart or my collection of story structure diagrams.

Some of you may know that I am obsessed with story structure. If you didn’t know this, please check out my WIP novel structure chart or my collection of story structure diagrams.

It’s no big surprise that I did my VCFA graduate lecture on structure and story design. I love this topic. Thus, I’ve broken down the meat of my lecture into several posts that I will be sharing this month. Thus, I introduce the June blog series: Organic Architecture!

Recently I talked about the difference between literary talent and story talent, and this series is all about developing the story-talent side of a writer’s repertoire. Often we think there is only one way to structure and design a story. Yes, I’m talking about the influence of three-act structure, the hero’s journey, and Aristotle. Well, it turns out these ideas are not the only possibilities, and are actually pretty limiting!

And man, do I get excited when I read quotes like this:

Three act structure and Aristotilean terms (i.e. rising action, climax, denouement) “are so broad and theoretical as to be almost meaningless … they have no practical value for storytellers … [They are] surprisingly narrow … extremely theoretical and difficult to put into practice … Three act structure is hopelessly simplistic and in many ways just plain wrong. ” – John Truby (The Anatomy of Story).

Did John Truby just blow your mind?

Did John Truby just blow your mind?

He blew my mind when I read that quote. So, I set out to see what other options are available for structure and story design. This blog series will give an overview of what I learned on that journey. It will start with three-act structure and the hero’s journey (so we’re all on the same page), and then push to explore the limitations of that structure, and the other options available!

Here’s the blurb for my lecture:

Organic Architecture: Structure, Screenwriting, and Story Design

Thanks to American film, you may think that the only way to plot and structure your story is with three acts and a hero’s journey. But do you ever feel limited by this recipe? What if your novel doesn’t even fit into this template? From the point of view of a screenwriter-turned-novelist, this lecture will explore the limitations of classic design, then push into the wild-and-woolly territory of alternative plots and structures. What if you could develop a story design that is unique to your novel, and arises organically from its premise, characters, setting, and themes? Unchain yourself from formulaic storytelling and see how many options are really at your fingertips! Familiarity with the film Toy Story is suggested. Core Topics: Plot/Structure, Writing Process, Character, Theme.

Please stay tuned for this exciting blog series which will cover:

- Arch Plot and Classic Design

- The Limitations of Classic Design

- Alternative Plot Types

- Alternative Story Structures

- Designing Principals

- Finding Your Stories Organic Architecture

Did you know that literary talent and story talent are not the same thing?

Literary talent is the use of words. It’s the ability to create beautiful sentences and spin a stunning metaphor. It’s the language of imagery, the emotion of a carefully placed consonant, crafty dialogue, and gorgeous descriptions.

But according to Robert McKee in his book Story “literary talent is common.” Where as story talent (in his opinion) is rare. He goes on to say that “literary and story talent are not only distinctively different but are unrelated, for stories do not need to be written to be told. Stories can be expressed any way human beings can communicate. Theater, prose, film, opera, mime, poetry, dance” (27).

Story talent is rare.

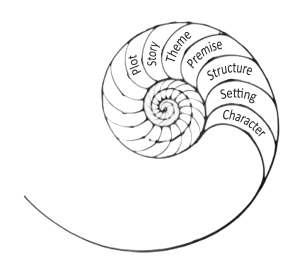

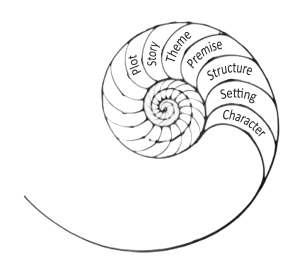

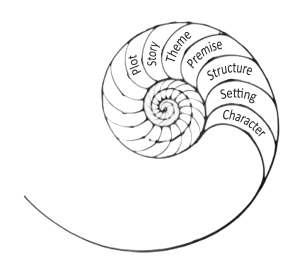

But what is story talent? Well, it’s everything else you are telling the story with. It’s the underlying life that the words evoke. It’s what you’d tell you story with if you couldn’t use words. It’s the character, plot, structure, and elements you use to construct your story. I like to think of this as the story design part of writing. The piece of you who must consider which piece goes where and why, and design the story so each of those pieces is essential. McKee defines story talent as “the creative conversation of life itself to a more powerful, clearer, more meaningful experience” (27).

To be a good writer you need to have both of these talents. You must master literary craft, but you must also master story design craft.

It was an important milestone in my personal writing journey to realize that these were not the same thing. In fact, I often find I might agree with McKee’s statement that story talent is rare. When a book is weak, it is seldom the literary writing that has disappointed me, but the design and telling of the story itself that I have problems with. Additionally, books lacking in beautiful phrases and witty dialogue, somehow still have me turning pages because the design of the story is so good. Which do you find lacking in the books you read? Literary talent or story talent?

Also, when people say “this book is really well written,” I find myself wondering if they mean the literary words or the story design? When you think a book is good, which part of the book are you talking about?

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

Did you know that literary talent and story talent are not the same thing?

Literary talent is the use of words. It’s the ability to create beautiful sentences and spin a stunning metaphor. It’s the language of imagery, the emotion of a carefully placed consonant, crafty dialogue, and gorgeous descriptions.

But according to Robert McKee in his book Story “literary talent is common.” Where as story talent (in his opinion) is rare. He goes on to say that “literary and story talent are not only distinctively different but are unrelated, for stories do not need to be written to be told. Stories can be expressed any way human beings can communicate. Theater, prose, film, opera, mime, poetry, dance” (27).

Story talent is rare.

But what is story talent? Well, it’s everything else you are telling the story with. It’s the underlying life that the words evoke. It’s what you’d tell you story with if you couldn’t use words. It’s the character, plot, structure, and elements you use to construct your story. I like to think of this as the story design part of writing. The piece of you who must consider which piece goes where and why, and design the story so each of those pieces is essential. McKee defines story talent as “the creative conversation of life itself to a more powerful, clearer, more meaningful experience” (27).

To be a good writer you need to have both of these talents. You must master literary craft, but you must also master story design craft.

It was an important milestone in my personal writing journey to realize that these were not the same thing. In fact, I often find I might agree with McKee’s statement that story talent is rare. When a book is weak, it is seldom the literary writing that has disappointed me, but the design and telling of the story itself that I have problems with. Additionally, books lacking in beautiful phrases and witty dialogue, somehow still have me turning pages because the design of the story is so good. Which do you find lacking in the books you read? Literary talent or story talent?

Also, when people say “this book is really well written,” I find myself wondering if they mean the literary words or the story design? When you think a book is good, which part of the book are you talking about?

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: IT Books, 1997.

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

[…] First off, Ingrid Sundberg. Ingrid Sundberg is a fellow VCFA alum. She recently posted a fabulous series taken from her thesis on story architecture. If you only saw bits, or missed the whole thing, bookmark this page which includes the links for the entire series. Organic Architecture: Links to the Whole Series […]

Thank you for this marvelous and informative series! Bookmarking this page for future reference!

Thanks for this wrap-up! You did such an awesome job with this!!!

Thank you for this amazing series, Ingrid! I haven’t thanked you often enough, but yours is the one blog I always read.

You are awesome!

Very impressed by what you’ve managed to put together here.