Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Holmes, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

Blog: the enchanted easel (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: painting, children's art, bird, etsy, forest, sale, kawaii, print, fox, whimsical, holmes, sherlock, nursery art, the enchanted easel, december discount days, Add a tag

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: holmes’, doyle’s, wakes, Literature, short stories, mystery, garden, sherlock holmes, holmes, april fools, Oxford World's Classics, arthur conan doyle, Humanities, sherlock, *Featured, Add a tag

Here at Oxford University Press we occasionally get the chance to discover a new and exciting piece of literary history. We’re excited to share the newest short story addition to the Sherlock Holmes mysteries in Sherlock Holmes: Selected Stories. Never before published, our editorial team has acquired The Mystery of the Green Garden, now believed to be Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s first use of the Sherlock Holmes’ character in his writing. Written during Doyle’s time at Stonyhurst College before entering medical school, the short story displays an early, amateur style of writing not seen in his later published works.

The Mystery of the Green Garden is set during Sherlock Holmes’ childhood – a rarely discussed part of Holmes’ life. Holmes’ is only sixteen years old when he is called to his first case. Unlike many of the stories in the Holmes series which are narrated by the loyal Dr. Watson, Holmes himself tells the short, endearing tale of his mother’s beloved garden. Getting our first look at his parents, Holmes briefly describes his mother as a “lively but often brooding woman.” We catch only a glimpse of his father who he calls a tireless civil serviceman with, “rarely enough time to fix even a long ago missing board in the kitchen’s creaking floor.”

Before attending university where he first acquired his detective skills, and moving to 221S Baker Street to practice his craft, Holmes lived at 45 Tilly Lane overlooking “a lush, never ignored garden.” Described as his mother’s favorite pastime, she gardened tirelessly day in and day out. As a young boy he recalls “spending countless hours playing in the dirt as mother tended to her beloved flowers and ferns.”

One morning, Holmes wakes to discover the garden destroyed. Flower beds are overturned, and shrubbery and plants are ripped apart. His mother is beside herself upon seeing her hard work demolished, and Holmes vows to discover the foolish culprit behind the dastardly act. A neighbor provides the first clue that sets the wheels in motion. His elderly neighbor who often wakes “before the sun has met the sky,” describes to Holmes a “tall, lean man with a crooked gray cap” that he saw running down the pathway between their two houses in the early hours of the morning while everyone in town still slept. Without any experience at solving cases, Doyle displays the first use of Holmes’ abductive reasoning skills later developed in the stories. As Holmes gathers clues as to what seems to be a random act, a story bigger than anyone can imagine slowly unravels.

April Fools! We hope we haven’t disappointed you too much. Although The Mystery in the Green Garden is just the work of a fool’s mind, there are seven Sherlock Holmes novels in the Oxford World’s Classics series. Sherlock Holmes: Selected Stories includes over a dozen stories truly written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Sherlock Holmes’ beginnings appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Editor's Picks, *Featured, Physics & Chemistry, Science & Medicine, ciphers, James O’Brien, Scientific Sherlock Holmes, typewritten documents, Literature, dogs, Edgar Allan Poe, sherlock holmes, holmes, fingerprints, footprints, handwriting, arthur conan doyle, forensic science, sherlock, Add a tag

By James O’Brien

Between Edgar Allan Poe’s invention of the detective story with The Murders in the Rue Morgue in 1841 and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes story A Study in Scarlet in 1887, chance and coincidence played a large part in crime fiction. Nevertheless, Conan Doyle resolved that his detective would solve his cases using reason. He modeled Holmes on Poe’s Dupin and made Sherlock Holmes a man of science and an innovator of forensic methods. Holmes is so much at the forefront of detection that he has authored several monographs on crime-solving techniques. In most cases the well-read Conan Doyle has Holmes use methods years before the official police forces in both Britain and America get around to them. The result was 60 stories in which logic, deduction, and science dominate the scene.

FINGERPRINTS

Sherlock Holmes was quick to realize the value of fingerprint evidence. The first case in which fingerprints are mentioned is The Sign of Four, published in 1890, and he’s still using them 36 years later in the 55th story, The Three Gables (1926). Scotland Yard did not begin to use fingerprints until 1901.

It is interesting to note that Conan Doyle chose to have Holmes use fingerprints but not bertillonage (also called anthropometry), the system of identification by measuring twelve characteristics of the body. That system was originated by Alphonse Bertillon in Paris. The two methods competed for forensic ascendancy for many years. The astute Conan Doyle picked the eventual winner.

TYPEWRITTEN DOCUMENTS

As the author of a monograph entitled “The Typewriter and its Relation to Crime,” Holmes was of course an innovator in the analysis of typewritten documents. In the one case involving a typewriter, A Case of Identity (1891), only Holmes realized the importance of the fact that all the letters received by Mary Sutherland from Hosmer Angel were typewritten — even his name is typed and no signature is applied. This observation leads Holmes to the culprit. By obtaining a typewritten note from his suspect, Holmes brilliantly analyses the idiosyncrasies of the man’s typewriter. In the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) started a Document Section soon after its crime lab opened in 1932. Holmes’s work preceded this by forty years.

HANDWRITING

Conan Doyle, a true believer in handwriting analysis, exaggerates Holmes’s abilities to interpret documents. Holmes is able to tell gender, make deductions about the character of the writer, and even compare two samples of writing and deduce whether the persons are related. This is another area where Holmes has written a monograph (on the dating of documents). Handwritten documents figure in nine stories. In The Reigate Squires, Holmes observes that two related people wrote the incriminating note jointly. This allows him to quickly deduce that the Cunninghams, father and son, are the guilty parties. In The Norwood Builder, Holmes can tell that Jonas Oldacre has written his will while riding on a train. Reasoning that no one would write such an important document on a train, Holmes is persuaded that the will is fraudulent. So immediately at the beginning of the case he is hot on the trail of the culprit.

FOOTPRINTS

Holmes also uses footprint analysis to identify culprits throughout his fictional career, from the very first story to the 57th story (The Lion’s Mane published in 1926). Fully 29 of the 60 stories include footprint evidence. The Boscombe Valley Mystery is solved almost entirely by footprint analysis. Holmes analyses footprints on quite a variety of surfaces: clay soil, snow, carpet, dust, mud, blood, ashes, and even a curtain. Yet another one of Sherlock Holmes’s monographs is on the topic (“The tracing of footsteps, with some remarks upon the uses of Plaster of Paris as a preserver of impresses”).

![]()

CIPHERS

Sherlock Holmes solves a variety of ciphers. In The “Gloria Scott” he deduces that in the message that frightens Old Trevor every third word is to be read. A similar system was used in the American Civil War. It was also how young listeners of the Captain Midnight radio show in the 1940s used their decoder rings to get information about upcoming programs. In The Valley of Fear Holmes has a man planted inside Professor Moriarty’s organization. When he receives an encoded message Holmes must first realize that the cipher uses a book. After deducing which book he is able to retrieve the message. This is exactly how Benedict Arnold sent information to the British about General George Washington’s troop movements. Holmes’s most successful use of cryptology occurs in The Dancing Men. His analysis of the stick figure men left as messages is done by frequency analysis, starting with “e” as the most common letter. Conan Doyle is again following Poe who earlier used the same idea in The Gold Bug (1843). Holmes’s monograph on cryptology analyses 160 separate ciphers.

DOGS

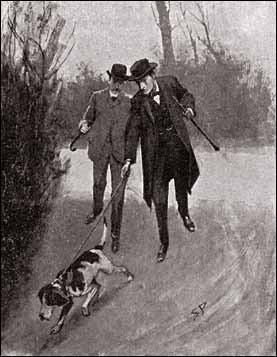

Conan Doyle provides us with an interesting array of dog stories and analyses. The most famous line in all the sixty stories, spoken by Inspector Gregory in Silver Blaze, is “The dog did nothing in the night-time.” When Holmes directs Gregory’s attention to “the curious incident of the dog in the night-time,” Gregory is puzzled by this enigmatic clue. Only Holmes seems to realize that the dog should have done something. Why did the dog make no noise when the horse, Silver Blaze, was led out of the stable in the dead of night? Inspector Gregory may be slow to catch on, but Sherlock Holmes is immediately suspicious of the horse’s trainer, John Straker. In Shoscombe Old Place we find exactly the opposite behavior by a dog. Lady Beatrice Falder’s dog snarled when he should not have. This time the dog doing something was the key to the solution. When Holmes took the dog near his mistress’s carriage, the dog knew that someone was impersonating his mistress. In two other cases Holmes employs dogs to follow the movements of people. In The Sign of Four, Toby initially fails to follow the odor of creosote to find Tonga, the pygmy from the Andaman Islands. In The Missing Three Quarter the dog Pompey successfully tracks Godfrey Staunton by the smell of aniseed. And of course, Holmes mentions yet another monograph on the use of dogs in detective work.

Conan Doyle provides us with an interesting array of dog stories and analyses. The most famous line in all the sixty stories, spoken by Inspector Gregory in Silver Blaze, is “The dog did nothing in the night-time.” When Holmes directs Gregory’s attention to “the curious incident of the dog in the night-time,” Gregory is puzzled by this enigmatic clue. Only Holmes seems to realize that the dog should have done something. Why did the dog make no noise when the horse, Silver Blaze, was led out of the stable in the dead of night? Inspector Gregory may be slow to catch on, but Sherlock Holmes is immediately suspicious of the horse’s trainer, John Straker. In Shoscombe Old Place we find exactly the opposite behavior by a dog. Lady Beatrice Falder’s dog snarled when he should not have. This time the dog doing something was the key to the solution. When Holmes took the dog near his mistress’s carriage, the dog knew that someone was impersonating his mistress. In two other cases Holmes employs dogs to follow the movements of people. In The Sign of Four, Toby initially fails to follow the odor of creosote to find Tonga, the pygmy from the Andaman Islands. In The Missing Three Quarter the dog Pompey successfully tracks Godfrey Staunton by the smell of aniseed. And of course, Holmes mentions yet another monograph on the use of dogs in detective work.

James O’Brien is the author of The Scientific Sherlock Holmes. He will be signing books at the OUP booth 524 at the American Chemical Society conference in Indiana on 9 September 2013 at 2:00 p.m. He is Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Missouri State University. A lifelong fan of Holmes, O’Brien presented his paper “What Kind of Chemist Was Sherlock Holmes” at the 1992 national American Chemical Society meeting, which resulted in an invitation to write a chapter on Holmes the chemist in the book Chemistry and Science Fiction. He has since given over 120 lectures on Holmes and science. Read his previous blog post “Sherlock Holmes knew chemistry.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) From “The Adventure of the Dancing Men” Sherlock Holmes story. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Sherlock Holmes in “The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter.” Illustration by Sidney Paget. Strand Magazine, 1904. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Six methods of detection in Sherlock Holmes appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: ACHOCKABLOG (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Deals, series, holmes, sherlock, Add a tag

New Three-Book Deal For Young Sherlock Author

from The Bookseller:

Macmillan Children's Books has acquired three titles from its Young Sherlock Holmes author Andrew Lane, which focus on the hunt for valuable endangered creatures. MCB associate publishing director Polly Nolan bought world rights from Robert Kirby at United Agents to the three novels in The Lost World series. MCB will publish a title a year from May 2013 as £5.99 paperback originals and as e-books. It is planning a "major marketing and publicity campaign".

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Alexandre Desplat, Buck Sanders, hans Zimmer, James Horner, Kathryn Kalinak, Marco Beltrami, Michael Giacchino, Original Score, Original Song, Kalinak, Fantastic, Mr, Score, Soundcheck, Horner, Alexandre, Desplat, Marco, Beltrami, Buck, Sanders, Giacchino, Music, Film, The, Avatar, Current Events, oscars, A-Featured, Media, sherlock holmes, Song, Up, Fox, Holmes, Oscar, Zimmer, VSI, Locker, Hurt, James, Original, nomination, The Hurt Locker, hans, Kathryn, Michael, nominees, WNYC, Sherlock, category, Fantastic Mr. Fox, Add a tag

Lauren, Publicity Assistant

Kathryn Kalinak is Professor of English and Film Studies at Rhode Island College. Her extensive writing on film music includes numerous articles and several books, the most recent of which is Film Music: A Very Short Introduction. Below, she has made predictions for the Oscar Music (Original Score) category, and

picked her favorites.

We want to know your thoughts as well! Who do you think will win the Oscar for Original Score? Original Song? Send your predictions to [email protected] by tomorrow, March 6, with the subject line “Oscars” and we’ll send a free copy of Film Music: A Very Short Introduction to the first 5 people who guessed correctly.

We also welcome you to tune in to WNYC at 2pm ET today to hear Kathryn discuss Oscar-nominated music on Soundcheck.

This Sunday’s Oscars will recognize an exceptionally fine slate of film scores, and it’s nice to see such a deserving group of composers. The nominees represent a range of films and scores including the lush and symphonic (Avatar), whimsical (Fantastic Mr. Fox), edgy and tension-producing (The Hurt Locker), eclectic and genre-bending (Sherlock Holmes), and beautifully melodic (Up). While there are always surprises, I’ve considered each composer and score, coming to the following conclusions and predictions.

On Avatar:

James Horner has been around a long time, having been nominated ten times in the last 32 years, and receiving Best Score and Best Song Oscars for Titanic. He’s a pro at what he does best: big, symphonic scores that hearken back to the classical Hollywood studio years. Horner’s music gives Avatar exactly what it needs—warmth and emotional resonance—and connects the audience to a series of images and characters that might be difficult to relate to otherwise. If Horner wins Sunday night, look for the evening to go Avatar’s way.

Blog: Writing and Ruminating (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: alexander, austen, quoteskimming, kirkup, holmes, alexander, quoteskimming, kirkup, austen, holmes, Add a tag

On what writing is

"I always thought writing was arraying words in beautiful patterns, but now I think it's more like walking blindfolded, listening with your whole heart, and then looking backward to see if you made any tracks worth keeping." Sara Lewis Holmes in her recent Poetry Friday post at Read Write Believe.

On why fiction/fantasy matter

Ten days ago, I put up a post entitled "Why We Need Fiction", about which I remain pleased. One of my rationales for why fiction is important reads as follows: "We need fiction because it allows us to create an artificial barrier, behind which we can examine Big Important Issues in a hypothetical setting, instead of beating people's brains out, possibly literally, by addressing those issues in the real world."

I've started reading my copy of The Wand in the Word: Conversations with Writers of Fantasy by Leonard S. Marcus, and it appears that Lloyd Alexander agreed with me in part:

"Q: Why do you write fantasy?

A: Because, paradoxically, fantasy is a good way to show the world as it is. Fantasy can show us the truth about human relationships and moral dilemmas because it works on our emotions on a deeper, symbolic level than realistic fiction. It has the same emotional power as a dream."

On poetry

Here, the first seven lines of a fourteen-line poem by James Kirkup called "The Poet":

Each instant of his life, a task, he never rests,

And works most when he appears to be doing nothing.

The least of it is putting down in words

What usually remains unwritten and unspoken,

And would so often be much better left

Unsaid, for it is really the unspeakable

That he must try to give an ordinary tongue to. And from Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey, which airs tonight at 9 p.m. on most PBS stations, the novel of which I reviewed last July. Here is a portion of the text taken from a description of the developing friendship between Catherine Morland and Isabella Thorpe. This section is often referred to as Austen's "defence of the novel", and is found in Volume I, chapter 5 of the novel:

And from Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey, which airs tonight at 9 p.m. on most PBS stations, the novel of which I reviewed last July. Here is a portion of the text taken from a description of the developing friendship between Catherine Morland and Isabella Thorpe. This section is often referred to as Austen's "defence of the novel", and is found in Volume I, chapter 5 of the novel:

. . . and if a rainy morning deprived them of other enjoyments, they were still resolute in meeting in defiance of wet and dirt, and shut themselves up, to read novels together. Yes, novels; ——for I will not adopt that ungenerous and impolitic custom so common with novel-writers, of degrading by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding ——joining with their greatest enemies in bestowing the harshest epithets on such works, and scarcely ever permitting them to be read by their own heroine, who, if she accidentally take up a novel, is sure to turn over its insipid pages with disgust. Alas! if the heroine of one novel be not patronized by the heroine of another, from whom can she expect protection and regard? I cannot approve of it. Let us leave it to the Reviewers to abuse such effusions of fancy at their leisure, and over every new novel to talk in threadbare strains of the trash with which the press now groans. Let us not desert one another; we are an injured body. Although our productions have afforded more extensive and unaffected pleasure than those of any other literary corporation in the world, no species of composition has been so much decried. From pride, ignorance, or fashion, our foes are almost as many as our readers. And while the abilities of the nine-hundredth abridger of the History of England, or of the man who collects and publishes in a volume some dozen lines of Milton, Pope, and Prior, with a paper from the Spectator, and a chapter from Sterne, are eulogized by a thousand pens, -- there seems almost a general wish of decrying the capacity and undervaluing the labour of the novelist, and of slighting the performances which have only genius, wit, and taste to recommend them. "I am no novel-reader ——I seldom look into novels ——Do not imagine that I often read novels ——It is really very well for a novel." ——Such is the common cant. —— "And what are you reading, Miss ——————?" "Oh! it is only a novel!" replies the young lady; while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame. ——"It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda;" or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language. Now, had the same young lady been engaged with a volume of the Spectator, instead of such a work, how proudly would she have produced the book, and told its name; though the chances must be against her being occupied by any part of that voluminous publication, of which either the matter or manner would not disgust a young person of taste: the substance of its papers so often consisting in the statement of improbable circumstances, unnatural characters, and topics of conversation which no longer concern anyone living; and their language, too, frequently so coarse as to give no very favourable idea of the age that could endure it.

Seems the more things change, the more they remain the same. No?