new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Dictionaries, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 76 - 100 of 311

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Dictionaries in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Lauren,

on 1/27/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

pooh,

Dictionaries,

bloom county,

oed,

Obama,

south park,

mark peters,

abyss,

cylon,

higgledy-piggledy,

Beavis and Butthead,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

buttmunch,

dumbass,

primordial,

taint,

wazoo,

wordlust,

higgledy,

“’higgledy,

Add a tag

By Mark Peters

It’s easy to find articles about words people hate. Just google for a nanominute and you’ll find rants against moist, like, whom, irregardless, retarded, synergy, and hordes of other offending lexical items. Word-hating is rampant.

So if that’s the kind of thing that yanks your lexical crank, look elsewhere: this column is all about word love, word lust, word like, word kissy-face, and word making-sweet-love-down-by-the-fire, as South Park’s Chef would put it.

These words not only float my boat; they rock my socks and warm my cocoa. I love these words, and this is my attempt to figure out why. If such analysis ruins the love, as so often happens in life, big whup. There are plenty of other words in the sea.

wazoo

We’ll never know why intelligent young citizens become proctologists (or how they break the news to Ma and Pa back on the farm) but we do know that words for the butticular region tend to be vivid and fun. Wazoo is my favorite. The OED traces it back to a friendly suggestion made in 1961: “Run it up yer ol’ wazoo!” I couldn’t agree more with a 1975 example: “Dating is a real pain in the wazoo.”

So what’s so great about wazoo? Studies show you can’t say it and be in a bad mood. Try it and see: wazoo wazoo wazoo wazoo wazoo. It’s funny and silly and a blast to say. Surely, it’s a better world with wazoo in it.

Bonus wazoo words: I am also a staunch admirer of gazoomba, bippy, badonkadonk, bottom, tush, fanny, fourth point of contact, and tuchus.

abyss

My mother always warned me to avoid two things: packs of wild dogs and the abyss. Still, I can’t stop reveling in this word. Part of the appeal is its meaning. You have to love a definition this ultra-hellish: “The great deep, the primal chaos; the bowels of the earth, the supposed cavity of the lower world; the infernal pit.” The OED’s secondary meaning is nearly as cool: “A bottomless gulf; any unfathomable or apparently unfathomable cavity or void space; a profound gulf, chasm, or void extending beneath.”

Also, I love looking into the abyss—except when I make the void jealous. The void is very insecure, you know.

buttmunch

When it comes to a perfect marriage of humor and stupidity, you can’t get any better than Beavis and Butthead, and I have yet to greet the day when I get tired of hearing their litany of immature, silly insults, such as dumbass, bunghole, peckerwood, dillweed, dillhole, and butt dumpling.

For me, the dumbass laureate of these words is buttmunch, so I was pleased to learn its origin in the DVD extra “Taint of Greatness: The Journey of Beavis and Butt-head, Part 1.” As B&B creator Mike Judge tells the tale, “Standards at MTV said no to assmunch. So I said, how about buttmunch? So we started saying buttmunch so many times, and then I just inadvertently said assmunch once. And they just heard buttmunch so many times that assmunch didn’t sound like anything new, so then assmunch slipped past ‘em. And that’s the story of assmunch and buttmunch.”

higgledy-piggledy

My marginally reliable memory told me I first saw this magnificent word in a Bloom County cartoon. Lucky for me and the

By: Lauren,

on 1/19/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

sexual,

doggy style,

go nuts,

nut job,

Food and Drink,

Dictionaries,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

testicles,

Oxford Etymologist,

sex,

word origins,

oed,

nuts,

anatoly liberman,

euphemism,

spoon,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Last week I mentioned the idiom to be (dead) nuts on ‘to be in love with’ and the verb spoon ‘to make love’ and promised to say something about both. After such a promise our readers must have spent the middle of January in awful suspense. So here goes. The semantic range of many slang words is often broad, but the multitude of senses attested for Engl. nut (see the OED) is amazing. I will reproduce some of them, both obsolete and current: “a source of pleasure or delight” (“To see me here would be simply nuts to her”), nuts in the phrases to be (dead) nuts on “to be in love of, fond of, or delighted with,” to be nuts about, as in “I was still nuts about Rex,” and to be nuts “go mad” (hence nutjob ~ nut job ~ nut-job “madman; idiot” and nutsy “crazy”). The exclamation nuts! means “nonsense,” while, contrary to expectation, the nuts signifies an excellent person. It will be seen that the senses can be positive, as in “a source a delight” (here are two more examples from my reading: “An English country gentleman might express himself concerning an agreeable incident: ‘It was nuts’” and “To edge his way along the crowded paths of life, warning all human sympathy to keep its distance, was what the knowing ones call ‘nuts’ to Scrooge”), and negative (“madness; stupidity”). Consequently, tracing nuts to German von Nutzen “of use” would be a false move (this origin of nuts has been proposed by a good German scholar). In etymological works, it is common to preface a hypothesis by a disclaimer to the effect that someone may have offered the same hypothesis, but the author is ignorant of it. I am obliged to do the same: my idea is so obvious, even trivial, that it must have occurred to anyone who wondered what nuts (as in hazelnuts or peanuts) have to do with either extreme pleasure or derangement.

The slang word nut in the singular is also frequent, but we note that in all the examples given above the plural nuts occurs. I suspect that the story begins with nuts “testicles,” even though the earliest recorded examples of this sense are late (however, it must have been so well-known in the United States more than a hundred years ago that The Century Dictionary included it). Nuts and genitalia have been compared for centuries. Thus, nut occurred with the sense of “the glans penis,” and the Germans call this part of the male organ of procreation Eichel “acorn” (in older writings on the history of words the glosses in such situations were always given in Latin; those who are embarrassed by plain English are welcome to use membrum virile). I suggest that nuts emerged as a loose word for expressing a strong feeling: nuts! “nonsense,” nuts! “wonderful,” nuts! “crazy,” and so forth. Such an exclamation can express any emotion. Nut “head” is probably an independent coinage (the head has been likened to all kinds of oblong and round objects in many languages); hence off one’s nut, though nuts “mad” may have reinforced that phrase. (The Russian verb o—et’, whose middle contains the most vulgar and formerly unprintable name for “penis,” means “to become mad”—another instance of genitalia and madness being connected; compare the metaphorical sense of Engl. prick).

Naturally, since nuts existed, the singula

By: Kirsty,

on 1/12/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

researching,

vimeo,

elizabeth knowles,

word histories,

george miller,

how to read a word,

knowles,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

podularity,

filmed by,

16866738,

histories,

Reference,

Video,

language,

words,

Dictionaries,

elizabeth,

etymology,

Add a tag

Historical lexicographer Elizabeth Knowles introduces her new book, How to Read a Word, which aims to introduce anyone with an interest in language to the pleasures of researching word histories. In this interview filmed by George Miller of Podularity in the library here at Oxford University Press in the UK she suggests some resources and techniques to get you started. Click here to read more by Elizabeth Knowles, and check back tomorrow for some of her One Minute Word Histories.

Click here to view the embedded video.

By: Lauren,

on 1/6/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

culturomics,

language,

words,

hello,

oed,

graphs,

google books,

Web of Language,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

culturome,

Math,

Dictionaries,

google,

english,

chaucer,

chagall,

better pencil,

Dennis Baron,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

People judge you by the words you use. This warning, once the slogan of a vocabulary building course, is now the mantra of the new science of culturomics.

People judge you by the words you use. This warning, once the slogan of a vocabulary building course, is now the mantra of the new science of culturomics.

In “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books” (Michel, et al., Science, Dec. 17, 2010), a Harvard-led research team introduces “culturomics” as “the application of high throughput data collection and analysis to the study of human culture.” In plain English, they crunched a database of 500 billion words contained in 5 million books published between 1500 and 2008 in English and several other languages and digitized by Google. The resulting analysis provides insight into the state of these languages, how they change, and how they reflect culture at any given point in time.

In still plainer English, they turned Google Books into a massively-multiplayer online game where players track word frequency and guess what writers from 1500 to 2008 were thinking, and why. The words you use tell the culturonomists exactly who you are–and they can even graph the results!

According to the psychologists and mathematicians on the culturomics team, reducing books and their words to numbers and graphs will finally give the fuzzy humanistic interpretation of history, literature, and the arts the rigorous scientific footing it has lacked for so long.

For example, the graph below tracks the frequency of the name Marc Chagall (1887-1985) in English and German books from 1900 to 2000, revealing a sharp dip in German mentions of the modernist Jewish artist from 1933 to 1945. You don’t need a graph to correlate Hitler’s ban on Chagall and his work with the artist’s disappearance from German print (other Jewish artists weren’t just censored by the Nazis, they were murdered), but it is interesting to note that both before and after the Hitler era, Chagall garners significantly more mentions in German books than he does in English ones.

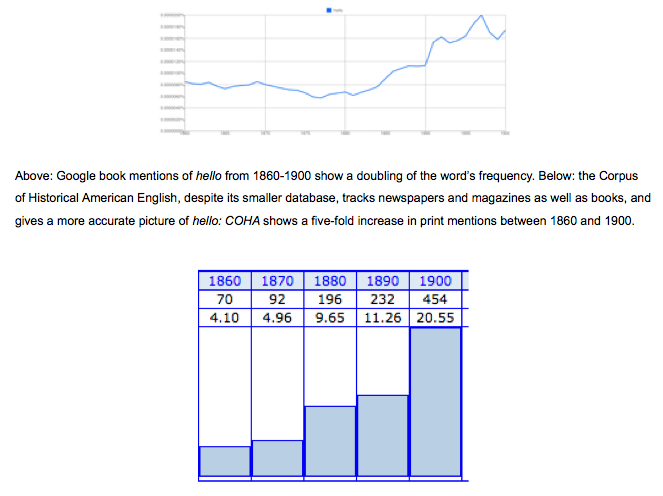

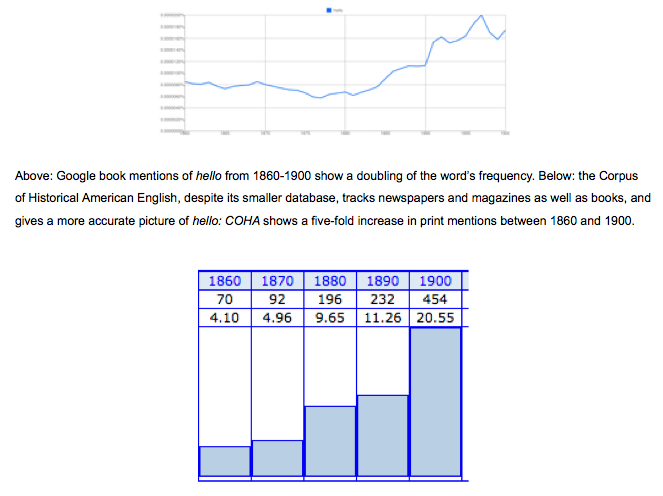

One problem with the culturome data set is that books don’t always reflect the spoken language accurately. When the telephone was invented in 1876, Americans adapted hello as a greeting to use when answering calls. Before that time, hello was an extremely rare word that served as a way of hailing a boat or as an expression of surprise. But as the telephone spread across American cities, hello quickly became the customary greeting both for telephone, and then for face-to-face, conversation.

Expanding the data set of written English to include not just books but also newspapers, periodicals, letters, and informal writing, as we find in the smaller, 400-million word Corpus of Historical American English, gives a better idea of the frequency of words like hello. But crunching numbers doesn’t tell the whole story: we can infer from contemporary published accounts, many of them strong objections to the new term, that hello is much more common in speech than its occurrence in writing indicates.

It’s one thing to read a book and speculate about its meaning—that’s what readers are supposed to do. But culturomics crunches millions of books—more than the most ardent book club groupie could get through in a lifetime. Since mos

By: Lauren,

on 12/9/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

mythology,

beowulf,

Dictionaries,

Online Resources,

Tolkien,

word origins,

C. S. Lewis,

chronicles of narnia,

narnia,

etymology,

voyage of the dawn treader,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

horse and his boy,

jeremy marshall,

oxford dictionaries,

ring of words,

Add a tag

Curious Words from the Chronicles of Narnia

By Jeremy Marshall

Many dictionaries and guides are careful to warn readers about the difference between a

faun and a

fawn. However, anyone familiar with the tales of

C. S. Lewis is unlikely to confuse these two shy inhabitants of woodland glades, since the goat-footed, part-human

faun of classical Roman mythology is the first strange creature we encounter when reading

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Those who know the film/movie version will be flocking back to the theaters this month to see more fantastical creatures in

Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

Many legendary creatures from ancient Greece and Rome, the Middle East, and Northern Europe inhabit Lewis’s Narnia. From the classical world come the beautiful maidens called

nymphs, including the

dryads, spirits of trees, and

naiads, spirits of streams and springs. (Lewis also calls the naiads ‘well-women’, which now reads rather oddly to anyone who has heard of ‘

well woman’ health clinics.) Also familiar to most readers are the

centaur—half horse, half human—and the more sinister

minotaur, or bull-headed man. The classical cast is completed by the god

Bacchus, with

Silenus and the

satyrs—similar to the fauns, but linked more to drunken revels than pastoral idylls—and by the

monopods, a one-legged race featured in

The Voyage of the ‘Dawn Treader’, whose history can be traced back to ‘tall tales’ of the wonders of India, written down by credulous (or unscrupulous) ancient Greek writers and repeated by the Roman encyclopedist

Pliny the Elder.

Mismatched myths

Alongside these—in a mythological mix which is said to have irritated Lewis’s friend Tolkien—we find the

dwarf of Germanic legend and the

ogre of old French tales, as well as the

merman, the

werewolf, the

bogle (Lewis uses the old northern spelling

boggle), and the

wraith. Among the retinue of the White Witch are three entirely unfamiliar types of creature, the

orknies,

ettins,

By: Lauren,

on 11/22/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

refudiate,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

grammar nazi,

grammar police,

grammar,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

english,

twitter,

tweet,

Sarah Palin,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

Last Spring the New York Times reported that more and more grammar vigilantes are showing up on Twitter to police the typos and grammar mistakes that they find on users’ tweets. According to the Times, the tweet police “see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette,” and some of them go so far as to write algorithms that seek out tweets gone wrong (John Metcalfe, “The Self-Appointed Twitter Scolds,” April 28, 2010).

Last Spring the New York Times reported that more and more grammar vigilantes are showing up on Twitter to police the typos and grammar mistakes that they find on users’ tweets. According to the Times, the tweet police “see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette,” and some of them go so far as to write algorithms that seek out tweets gone wrong (John Metcalfe, “The Self-Appointed Twitter Scolds,” April 28, 2010).

Twitter users post “tweets,” short messages no longer than 140 characters (spaces included). That length restriction can lead to beautifully-crafted, allusive, high-compression tweets where every word counts, a sort of digital haiku. But most tweets are not art. Instead, most users use Twitter to tell friends what they’re up to, send notes, and make offhand comments, so they squeeze as much text as possible into that limited space by resorting to abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and numbers for letters, the kind of shorthand also found, and often criticized, in texting on a mobile phone.

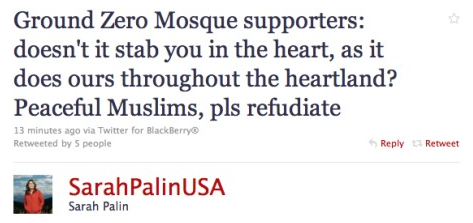

But what the tweet police are looking for are more traditional usage gaffes, like problems with subject-verb agreement, misspellings, or incorrect use of apostrophes. And they don’t like mistakes in word choice, as when Sarah Palin tweeted refudiate, not repudiate, in her objection to the Islamic Cultural Center being built near Ground Zero in lower Manhattan.

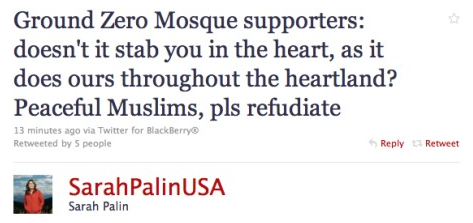

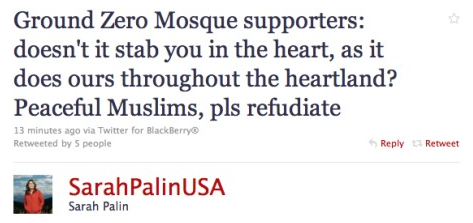

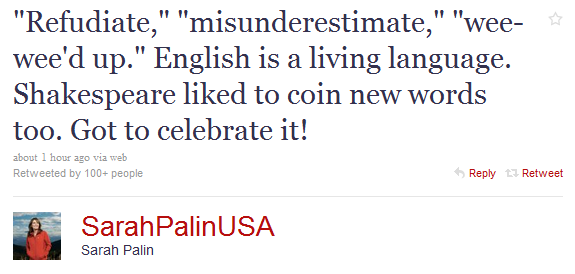

Palin is one of the celebrities on Twitter whose posts get a lot of scrutiny from the grammar watchers. But while refudiate was perceived to be an error, it’s not exactly a new word. According to Ammon Shea, it first appeared in 1891, and Ben Zimmer finds it surfacing again in 1925.

The immediate clamor that followed Palin’s use of refudiate in her July 18, 2010, tweet led Palin or someone on her staff to replace the original tweet with the edited version below. However, switching refudiate to refute didn’t placate the language purists, who insisted that she should have said repudiate.

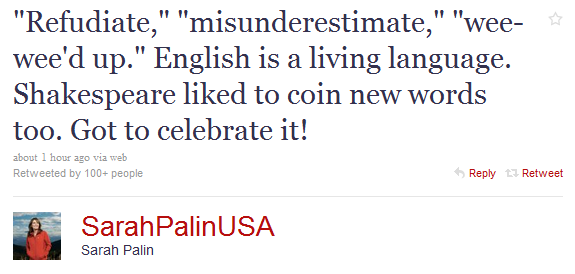

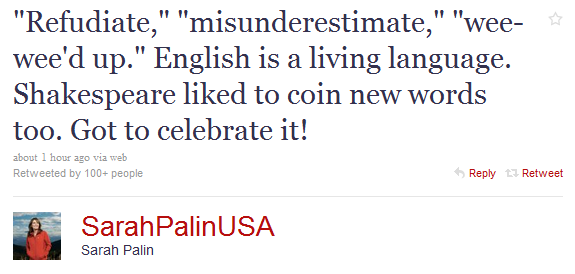

In a tweet later that same day (below), Palin decided to recast her mistake as an experiment in creativity, arguing that word coinage is common in English and suggesting that her use of refudiate was somehow Shakespearean.

As if to prove her point, the editors of the

0 Comments on ” :) when you say that, pardner” – the tweet police are watching as of 1/1/1900

By: Lauren,

on 11/16/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

podcast,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

itunes,

Sarah Palin,

Word of the Year,

New Oxford American Dictionary,

noad,

refudiate,

christine,

The Oxford Comment,

oxford comment,

lexicographer,

*Featured,

quickcast,

lindberg,

Add a tag

If you haven’t heard – well, how haven’t you heard? “Refudiate” is the New Oxford American Dictionary’s 2010 Word of the Year. (And no, that doesn’t mean “refudiate” has been added to the NOAD or any other Oxford dictionary.) In this quickcast, Michelle and Lauren talk with NOAD Senior Lexicographer Christine Lindberg, and take to the streets to see what people think of this special word – or shall we say word blend?

Subscribe and review this podcast on iTunes!

Music by The Ben Daniels Band.

By: Lauren,

on 11/15/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

twitter,

Sarah Palin,

glee,

webisode,

Word of the Year,

crowdsourcing,

New Oxford American Dictionary,

retweet,

tea-party,

vuvuzela,

refudiate,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

bankster,

double-dip,

gleek,

nom,

top kill,

Add a tag

Editor’s note: I love being right. I really, really love it. In July, I guessed that “refudiate” would be named Word of the Year, and TA-DAH! I was right. What Paul the Octopus was to the FIFA World Cup, I am to WOTY (may he rest in peace). But that’s enough about me because what’s really important is that…

Refudiate

has been named the New Oxford American Dictionary’s 2010 Word of the Year!

refudiate verb used loosely to mean “reject”: she called on them to refudiate the proposal to build a mosque.

[origin — blend of refute and repudiate]

Now, does that mean that “refudiate” has been added to the New Oxford American Dictionary? No it does not. Currently, there are no definite plans to include “refudiate” in the NOAD, the OED, or any of our other dictionaries. If you are interested in the most recent additions to the NOAD, you can read about them here. We have many dictionary programs, and each team of lexicographers carefully tracks the evolution of the English language. If a word becomes common enough (as did last year’s WOTY, unfriend), they will consider adding it to one (or several) of the dictionaries we publish. As for “refudiate,” well, I’m not yet sure that it will be includiated.

Refudiate: A Historical Perspective

An unquestionable buzzword in 2010, the word refudiate instantly evokes the name of Sarah Palin, who tweeted her way into a flurry of media activity when she used the word in certain statements posted on Twitter. Critics pounced on Palin, lampooning what they saw as nonsensical vocabulary and speculating on whether she meant “refute” or “repudiate.”

From a strictly lexical interpretation of the different contexts in which Palin has used “refudiate,” we have concluded that neither “refute” nor “repudiate” seems consistently precise, and that “refudiate” more or less stands on its own, suggesting a general sense of “reject.”

Although Palin is likely to be forever branded with the coinage of “refudiate,” she is by no means the first person to speak or write it—just as Warren G. Harding was not the first to use the word normalcy when he ran his 1920 presidential campaign under the slogan “A return to normalcy.” But Harding was a political celebrity, as Palin is now, and his critics spared no ridicule for his supposedly ignorant mangling of the correct word “normality.”

The Short List

In alphabetical order, here are our top ten finalists for the 2010 Word of the Year selection:

It was a lively week fueled largely by misinformation as talk about the Oxford University Press filled blogs and flooded news columns across the Web. “The king’s book may never be seen in print again,” they cried. “Did you hear about those words that were added? What could the king be thinking to allow the lowly words of mere peasants into the holy grail of dictionaries?” For anyone who thought that Dick Snary was companion only to writers and other word-geeks this hoopla was surely a wake-up call. What was the underlying reason for the ruckus? If a book is not available in print do we fear we are being denied the information? If words we consider crass are acknowledged and accepted by a credible source does that somehow dilute the “purity” of our language?

The English language has an almost limitless ability to expand and develop. This is good news for those of us who want to continue to communicate the never-ending evolution of thoughts and ideas. Our ability to express is limited only by our own imagination--or sometimes by our editor—not by printed decree of the king. This is a language created by the people; the use of which can be neither denied nor muffled. It can, however, be recorded.

This brings us back to Oxford University Press and some necessary clarifications:

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has not yet been printed. The ODE just revised RH--rococoesque and added the section to their draft for the new edition. A couple hundred words were added, mostly in this category, and there were some changes made in sub-categories. The new edition will probably be finished around the year 2020. Retail cost for a published volume set is estimated at $995. No final decision has been made regarding the cessation of printed volumes. The

OED is accessible online for a fee. Why pay for access to an online dictionary when you can look up a word for free? The OED is a historical dictionary as opposed to a current-use dictionary; it is more like an encyclopedic language reference.

It is the new edition the

Oxford Dictionary of English (ODE) which was just released along with its cousin, The

New Oxford American Dictionary. These works are where the 2000 new words appear including Muggle, staycation, paywall and unfriend. The ODE and the NOAD are compilations of the common usage of words.

Dictionaries reflect of our ever changing culture. They provide a window into the social habits and communications of our neighbors and a historical reference for generations to come. Consider all the many forms available to us today. We have dictionaries of medieval words, slang dictionaries in almost every language, and urban dictionaries in which everyday people post new phrases daily. Instead of worrying about what words are added to them let us celebrate what they represent-- our passion for words.

By: Lauren,

on 8/25/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

fuck,

f-word,

fogger,

pettifogger,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

How did pettifoggers get their name? Again and again we try to discover the origin of old slang, this time going back to the 16th century. Considering how impenetrable modern slang is, we should always be ready to stay with extremely modest conclusions in dealing with the popular speech of past epochs. In this blog, the essays on chestnut, tip, humbug, scoundrel, kybosh, and the much later copasetic and hubba-hubba, among others, have revealed some of the difficulties an etymologist encounters in dealing with such vocabulary.

In regards to the sphere of application, pettifogger belongs with huckster, hawker, and their synonym badger. All of them are obscure, badger being the hardest. Pettifoggers, shysters, and all kinds of hagglers have humble antecedents and usually live up to their names, which tend to be coined by their bearers. At one time it was customary to say that words like hullabaloo are as undignified as the things they designate. Today we call a marked correspondence between words’ meaning and their form iconicity, admire their raciness, and organize international conferences to celebrate their existence. Pettifogger is unlike hullabaloo (to which, incidentally, another post was once devoted), but there is something mildly “iconic” in it: petty refers to smallness, while fogger resembles f—er and thus commands minimal respect. As we will see, the resemblance is not fortuitous.

The Low (= Northern) German or Dutch origin of fogger is certain. The early Modern Dutch form focker was Latinized as foggerus, with -gg- in the middle. German has Focker, Fogger, and Fucker, none having any currency outside dialects. The OED cites them from the Grimms’ multivolume dictionary. (As is known, the OED had to bow to the morals of its time and excluded “unprintable” words, but in the entries where no one would look for them, offensive forms appeared: such is a mention of German fucker, with lower-case f, under fogger, and of windfucker “kestrel.”) Although today Dutch fokken means “to breed cattle,” its predecessor had a much broader semantic spectrum: “cheat; flee; adapt, adjust; beseem; push; collect things secretly”—an odd array of seemingly incompatible senses. Most likely, “push” was the starting point; hence “adjust,” then “adjust properly” (“beseem”). But despite doing things as it beseems or behooves, pushing suggested underhand dealings (“collect things secretly; cheat,” and even “flee,” evidently from acting in a hurry and clandestinely).

There can be little doubt that the English F-word is also a borrowing of a Low German verb whose basic meaning was, however, “move back and forth” rather than “push.” “Deceive” and “copulate” often appear as senses of one and the same verb. Fokken is a member of a large family. All over the Germanic speaking world we find ficken, ficka, fikla (compare Engl. fickle), fackeln, fickfacken, fucken, fuckeln, and so forth, meaning approximately the same: “make quick, short movements; hurry up; run aimlessly back and forth; shilly-shally; cheat (especially in games).” Unlike German, Dutch, and Scandinavian, English had almost no words with the fi(c)k ~ fa(c)k ~ fu(c)k root, so that fogger is rather obviously not native. The same, I believe, is true of several Romance words like Italian ficcare “copulate,” though in the latest dictionaries it is said to be unrelate

By: Lauren,

on 8/12/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

penn jillette,

humez,

pictographs,

rebus,

phonograms,

overworked,

i love my dog,

pictogram,

play on words,

short cuts,

visual puzzle,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Leisure,

Add a tag

By Alexander Humez

Largely gone from the funny pages but alive and well on the rear bumper of the car, the rebus is a visual puzzle that, in its various forms, encapsulates the history of alphabetic writing from ideograms (pictures designating concepts or things) to pictographs (pictures representing specific words or phrases) to phonograms (pictures representing specific sounds or series of sounds). Dictionaries struggle to define the term in such a way as to capture the range of shapes a rebus can take, typically focussing on its pictographic and phonogrammic attributes, forgoing mention of the ideographic. For example, the OED defines rebus as “a. An enigmatical representation of a name, word, or phrase by figures, pictures, arrangement of letters, etc., which suggest the syllables of which it is made up. b. In later use also applied to puzzles in which a punning application of each syllable of a word is given, without pictorial representation.”

The origin of the word is a matter of some debate (nicely summarized by Maxime Préaud in his “Breve histories du rebus francis” and treated at greater length by Card and Margo lin in their Rebus de la Renaissance: Des images quai par lent), but whatever its pedigree, the thing itself has been a popular item since at least the end of the fifteenth century. In his treatise on orthography of 1526 (Champ Fleur), Geoffroi Tory notes the practice of “jokers and young lovers” who make up “devices,” such as a small a inside a large g to signify “Jay grant appetit,” that is, “g grand a petit,” which he decries because, he says, such practices often result in sloppy penmanship and pronunciation. After giving a few more examples of “devices” made up of letters, he goes on to say that there are devices that aren’t made up of “significative letters,” but, rather, are made up of “images which signify the fantasies of their Author, & this is called a Rebus,” of which he describes (but does not depict) some examples.

The simplest rebuses are those consisting only of letters: IOU, the (in)famous title of Marcel Duchamp’s moustached Mona Lisa “l.h.o.o.q.” (Elle a chaud au cul, literally something like ‘Her ass is hot,’ figuratively, ‘She’s horny’), and such staples of modern day texting as CUL8R or French @2m1 (à deux m un, i.e., “à demain” ‘[See you] tomorrow’).

An elaboration of the all-character rebus is exemplified by the following, the first in English, the second in French (cited by Estienne Tabouret des Accords in his Les Bigarrures et Touches du Seigneur des Accords—roughly, ‘Lord des Accord’s Medley of Colors and Dabs’—which appeared in several editions in the late 16 th century):

(“I am overworked and underpaid”) and

(Le sous het en sur pens le

0 Comments on Are you ready for rebuses? as of 1/1/1900

By: Lauren,

on 7/28/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

spelling,

tattoo,

kibosh,

anatoly liberman,

arctic,

hoosier,

cabaret,

tatoo,

yeo,

Add a tag

by Anatoly Liberman

HOOSIER.

Almost exactly two years ago, on July 30, 2008, I posted an essay on the origin of the nickname Hoosier. In it I expressed my cautious support of R. Hooser, who derived the “moniker” for an inhabitant of Indiana from a family name. I was cautious not because I found fault with his reasoning but because it is dangerous for an outsider to express his opinion on a special subject; American onomastics (a branch of linguistics devoted to the study of names) is not my area. The bibliographers who had done outstanding work in listing the documents pertaining to Hoosier seem to have missed the article in Eurasian Studies Yearbook, 1999, 224-231. However, none of them reacted to my defense of the Hauser/Hoosier hypothesis either. Perhaps they missed that post: it is impossible to follow everything that appears in the Internet. Only Mr. J. Vanhoosier wrote a few words about the history of his family. His comment dates to February 2009. Mr. Randall Hooser (in Yearbook, his full name was not given) noticed my post in June 2010 and responded in some detail. Comments that are added so late have no chance of attracting my attention, because this weekly blog has existed for more than four years, but Mr. Hooser contacted me and sent me numerous supporting materials. His interpretation of historical evidence does not seem to be controversial, and I will deal only with the etymology of the nickname.

Mr. Hooser is not a linguist, and this is why he made too much of the fact that the High German au corresponds to long u (transliterated as Engl. oo) in Alsace, the homeland of the Hausers/Hoos(i)ers. But this correspondence needs no proof. In Middle High German, long i and u (transliterated by Engl. ee and oo) underwent diphthongization, which spread from Austrian Bavarian dialects in the 12th century and later became one of the most important features of the Standard. The “margins” of the German speaking world were unaffected by the change, so that the north (Low German) and the south (Alsace and Switzerland) still have monophthongs where they had them in the past. What has not been accounted for is the variant Hoosier as opposed to Hooser. In my 2008 post, I referred to such enigmatic American pronunciations as Frasier for Fraser and groshery for grocery, but analogs have no explanatory value. However, according to Mr. Hooser, linguists from Kentucky informed him that in the Appalachian area this type of phonetic change is regular, so that Moser becomes Mosier, and so forth. The cause of the change remains undiscovered. Although in this context the cause is irrelevant, I may note that in many areas of the Germanic speaking world one hears sh-like s, notably in Icelandic and Dutch, but not only there. Sh for s and zh (the latter as in Engl. pleasure, as you, and genre) for z characterized the earliest pronunciation of German. The Proto-Indo-European s was, in all likelihood, also a lisping sound. Perhaps the area from which the Hoosers migrated to America has just such a sibilant.

The original derogatory meaning of Hoosier is certain. Yet the word’s adoption by Indiana should cause no surprise; compare Suckers and Pukes for the inhabitants

By: Lauren,

on 7/20/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

palin,

Sarah Palin,

word of the year,

Sean Hannity,

urban dictionary,

google books,

hypermiling,

ground zero,

NAACP,

tea-party,

#shakespalin,

language log,

refudiate,

mediaite,

hannity,

Reference,

shakespeare,

Blogs,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

oxford english dictionary,

twitter,

tweet,

Add a tag

Here at Oxford, we love words. We love when they have ancient histories, we love when they have double-meanings, we love when they appear in alphabet soup, and we love when they are made up.

Last week on The Sean Hannity Show, Sarah Palin pushed for the Barack and Michelle Obama to refudiate the NAACP’s claim that the Tea Party movement harbors “racist elements.” (You can still watch the clip on Mediaite and further commentary at CNN.) Refudiate is not a recognized word in the English language, but a curious mix of repudiate and refute. But rather than shrug off the verbal faux pas and take more care in the future, Palin used it again in a tweet this past Sunday.

Note: This tweet has been since deleted and replaced by this one.

Later in the day, Palin responded to the backlash from bloggers and fellow Twitter users with this:

Whether Palin’s word blend was a subconscious stroke of genius, or just a slip of the tongue, it seems to have made a critic out of everyone. (See: #ShakesPalin) Lexicographers sure aren’t staying silent. Peter Sokolowksi of Merriam-Webster wonders, “What shall we call this? The Palin-drome?” And OUP lexicographer Christine Lindberg comments thus:

The err-sat political illuminary Sarah Palin is a notional treasure. And so adornable, too. I wish you liberals would wake up and smell the mooseburgers. Refudiate this, word snobs! Not only do I understand Ms. Palin’s message to our great land, I overstand it. Let us not be countermindful of the paths of freedom stricken by our Founding Fathers, lest we forget the midnight ride of Sam Revere through the streets of Philadelphia, shouting “The British our coming!” Thank the God above that a true patriot voice lives on today in Sarah Palin, who endares to live by the immorternal words of Nathan Henry, “I regret that I have but one language to mangle for my country.”

Mark Liberman over at Language Log asks, “If she really thought that refudiate was Shakespearean, wouldn’t she have left the original tweet proudly in place?”

He also points out that Palin did not coin the refudiate word blend. In fact, he says, “A

[In fishing for words I seem to have caught rather a lot - this is quite a long post so please enjoy with a nice cup of tea or coffee!]

Photo: kasperbs

M has been learning to read at school since November. It’s been a delight and a source of amazement to me to see her skill unfold and now with just a week left till the summer holidays begin I’ve been looking for different ways to support her reading whilst school’s out. She’s not what I would call an enthusiastic reader at the moment – yes, she loves to listen to stories and can spend a long time taking in every detail of illustrations, but reading by herself hasn’t yet become something she does for the sheer pleasure of it.

I’ve wondered if this might be partly because she’s had such a rich diet of books already – fantastic picture books with great stories and delicious illustrations, or audiobooks and bedtime chapter books with engaging stories of real literary merit that whisk her away to wonderful worlds where she can spend hours and hours, and swapping all of this for simple, cheaply illustrated early readers is asking a lot.

I know that I find it hard to go from The Secret Garden (our current bedtime book), How to train your dragon and all the other stories in that series (M’s favourite audiobooks at the moment) and picture books like One Smart Fish, The Tale of the Firebird or Nothing to Do to things like Ron Rabbit’s Big Day (even if it is written by Julia Donaldson) or A Cat in the Tree.

So with the summer holidays almost upon us I’ve been looking for ways to keep her reading and to bolster her enjoyment. One complaint she explicitly makes about the books she brings home from school is their length. So in thinking how to overcome the lack of motivation when it comes to reading I’ve been looking at … dictionaries.

Perhaps not the most obvious choice when it comes to texts for early readers, especially as I wasn’t looking at them to boost her vocabulary, or to help with her spelling (although this may come later on) but rather as a source of short texts that we could dip in an out of, perhaps a few times a day, rather than sitting down for a “long” reading session (almost an impossibility with a younger sibling around anyway!)

By Anatoly Liberman

Two circumstances have induced me to turn to bamboozle. First, I am constantly asked about its origin and have to confess my ignorance (with the disclaimer: “No one knows where it came from”; my acquaintances seldom understand this statement, for I have a reputation to live up to and am expected to provide final answers about the derivation of all words). Second, the Internet recycles the same meager information at our disposal again and again (I am not the only recipient of the fateful question). Since the etymology of bamboozle is guesswork from beginning to end, it matters little how often the uninspiring truth is repeated. Below I will say what little I can about the verb.

Bamboozle probably appeared in English some time around 1700, that is, roughly when it was first recorded. However, “appeared in English” does not mean “was coined,” for a word may exist in another language for any period of time before English absorbs it. Another problem is the definition of “English.” Bamboozle penetrated “polite society” at the beginning of the 18th century, but a provincialism will occasionally reach the capital and become part of common slang (like the word slang itself, for example) after a long underground existence in a dialect. Obscene words and words current in criminals’ language may also gain acceptance (in the rare cases they leave their natural environment) hundreds of years after their emergence. So we can only suppose that bamboozle was noticed rather than coined in London around 1700. Charles Camden Hotten, the author a famous slang dictionary, quoted Jonathan Swift, who had heard that bamboozle was invented by a nobleman during the reign of Charles II (1649-1688). Hotten was justified in doubting the accuracy of such an early date, even though he did not have the benefit of having the first volume of the OED on his desk. Those who lived 200 years ago knew that bamboozle was recent slang, and their opinion should be trusted. If a nobleman had made the verb popular in the second half of the 17th century, it would not have lain dormant so long: literary men would have made use of it.

In a search for the origin of bamboozle, some insecure roads lead to Rome, others to Paris (that is, to Italian and French). The problem is that the syllables bam, bum, and bom are so obviously onomatopoeic (compare boom) and expressive that words containing them can be found in most languages. They usually denote noises, little children, someone who can be duped like a baby, puppets, and so forth. Bamboozle may be an alteration of some such word, for instance, of French bambocher “to play pranks” or Italian imbambolare “to make a fool of one.” Close enough is German Bambus “a good-for-nothing; idler” (with several other related senses, as in Bambusen “bad sailors”), possibly of Slavic origin. Bambus has for a very good reason never been considered the etymon of bamboozle, but the similarity between the two words is striking.

The idea of borrowing is persuasive only when we succeed in showing how a foreign word reached its new home (through what intermediaries and in what milieu). Bamboozle surfaced among many other slang words at an epoch when London was swamped with such neologisms, and the only support we have for reconstructing its past is that at approximately the same time its synonym bam came into use. If bam is the source of bamboozle, an Italian or French source must be ruled out, but if bamboozle was “abbreviated” into bam, all the questions remain.

Contrary to some of the most eminent etymologists, I tend to think that the story began with bam, a word sugge

By: Charles Hodgson,

on 7/1/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

horses,

Podictionary,

Charles Hodgson,

livestock,

mustang,

mixta,

history of wine words,

mesta,

mestengo,

1808,

Add a tag

iTunes users can subscribe to this podcast

Around 500 years ago the Spanish brought horses to the Americas and in the ensuing mêlée enough of those horses escaped captivity that they reestablished themselves as wild animals in the new world. Evidently more than 50 million years ago they evolved here but had become extinct.

Although the name for wild horses in North America only emerged into English as mustang in 1808 this name was actually in the works by those same Spanish speakers before they ever shipped the horses across from Europe.

Although the name for wild horses in North America only emerged into English as mustang in 1808 this name was actually in the works by those same Spanish speakers before they ever shipped the horses across from Europe.

Back in the 13th century King Alfonso X have his royal approval to a group called mesta. This is sometimes now explained as “an association of livestock owners” but the reason the king cared was because this association had the job of enforcing tax collection among the owners of livestock.

The reason the group was called mesta was because they took their name from Latin and a phrase animalia mixta. After all these centuries it’s still obvious that this meant “a mix of different animals.” The name mesta came from mixta.

In order to collect taxes for the king mesta kept track of the various herds of animals.

Not only did domestic animals sometimes run away and become wild, but sometimes wild animals came in and joined up with the domestic animals. Clearly this was a profitable happenstance for both the owners and the king.

Wild horses such as these began to be called mestengo due to their association with the mesta but the meaning of mestengo was “stray” or “having no master.” The Spanish who came to the Americas with their horses also brought this terminology and another similar, synonymous word mostrenco which was eventually picked up in English, as I said, first showing up in the written record in 1808.

In 1964 the Ford motor company came out with a car they called the mustang. I don’t suppose they spent much time looking into the etymology of mustang. With an etymology that boils down to “without an owner” one might think such a name would encourage car theft. I don’t suppose though that people stealing these mustangs for joy rides were too deeply versed in etymology either.

For five years Charles Hodgson has produced

Podictionary – the podcast for word lovers. He’s also the author of several books including his latest

History of Wine Words – An Intoxicating Dictionary of Etymology from the Vineyard, Glass, and Bottle.

By Anatoly Liberman

I often mention the fact that the questions I get tend to recur, and I do not feel obliged to answer them again and again. Among the favorites is the pronunciation of forte “loudly” and forte “a strong point.” Those who realize that the first word is from Italian and the second from French will have no difficulty keeping them apart, though I wonder why anyone would want to say forte instead of strong point or strong feature: in today’s intellectual climate, elegant foreignisms are paste rather than diamonds. Very common is the query about the difference between “I could care less” and “I could not care less.” The “classic” variant is with the negation. Perhaps someone decided that “I could not care less” means “I do care for it” and removed not. This zeal for extra clarity is misguided, but, since the curtailed phrase has spread, it will compete successfully with the legitimate one and may even oust it.

The moribund subjunctive mood has both friends and enemies. Some correspondents find the phrase if I were you snobbish, while others cannot forgive those who say if I was you. In such constructions (compare: were I twenty years younger…), were is not the plural, but a relic of an ancient grammatical category. Since this subjunctive form is isolated, while the plural were is ubiquitous, unschooled speakers (and as regards grammar, such is the majority of today’s living population) are irritated by the group I were. The substitution of was for were in it is old and will eventually win out. Another grammatical question concerns Greek and Latin plurals. The plural of octopus is octopuses, because we speak English rather than Classical Greek. Should it be syllabi or syllabuses? This is a matter of personal preference. But here too excessive zeal should be discouraged, and those who do not know Latin (let alone Greek) are advised to exercise caution. The ludicrous plurals vademeci and even autobusi have been recorded. However, phenomenon is singular, and phenomena plural (many people who have learned that agenda and data are singulars, take also phenomena for the singular).

Complaints about the misuse of whom are frequent, and I share our correspondents’ chagrin, but this battle was lost long ago. Recently I have seen an article by the Associated Press with the title that began so: “Whomever did it, etc.” This is even more surprising than “No one saw the man whom entered the house,” in which the attraction of saw is the decisive factor.

It is a pleasure to report that I am not a solitary fighter against adverbial fluff. In my students’ papers I cross out every occurrence of actually, definitely, and their likes. Our correspondents “hate” literally and virtually, and so do I, but people tend to think that they will not be understood, appreciated, or even heard (and they have a good reason to think so). To break through the cosmic noise, they add reinforcing words: “The wolf actually swallowed Little Red Hood” (you won’t believe it, but he really did: trust me), “She definitely turned down the proposal” (now, you will agree, there is no way back), “I literally got sick after that binge” (how literally, I’ll leave to your imagination, though binge is a word of murky origin), “There is virtually nothing left of those riches” (something may be left, for virtually suggests the lack of completeness, but in our virtual age, in which we correspond, hate, and make love virtually, this adverb produces a comic effect). The death of the adverb (“Do it quick,” “He writes awful”) has been discussed in this blog several times, and I will pass it by.

By: LaurenA,

on 6/23/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

onomatopoeia,

break,

anatoly liberman,

brake,

bracu,

oink,

Reference,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Add a tag

by Anatoly Liberman

This is the promised continuation of the previous post. As I said last week, break is an old word. In the foggy days of Proto-Indo-European, it may have begun with the consonant bh (or simply bh), pronounced as in Modern Engl. abhor or Rob Hanson. For our purposes, the difference between b and bh matters not at all, because today we are only interested in observing how many words referring to breaking begin with br-. The subject of this essay is: “To what extent is classifying break with sound imitative (onomatopoeic) words justified?”

Moo, meow, and, admittedly, oink-oink are sound imitative. But once we leave the animal world and exclamations like phew and whew, assigning words to onomatopoeia is always problematic. Thus, each member of the set—crack, crash, crush, creak, croak, and cry—looks like any other word beginning with kr-, for example, craft, crawl, and creep, but in their entirety they produce the impression of belonging together and suggest a rather obvious sound effect. The same holds for initial gr-: compare groan, growl, grumble, grunt, and possibly grind. Numerous words signifying grouchy people, as well as grim and gruesome things, also begin with gr-. Labeling them sound imitative will not take us too far, since they have well-developed bodies and not only heads.

Modern scholars have no idea how language originated (or rather they have many ideas that cancel one another out; the usual cliché is “shrouded in mystery”), but in the existing languages words are conventional signs, that is, when we look at a word, we usually do not know its referent in the world of things. If we possessed such knowledge, explanatory and bilingual dictionaries would not be necessary: anybody would be able to look at a “sign” like bed or ten, or give and guess what it means. Moo is fine (presumably, no dictionary is required for translating it), but oink-oink is obscure: perhaps it is a soothing exclamation like tut-tut, a verb like pooh-pooh, a noun like tomtom (a drum), or the name of a disease like beriberi. I am not sure that pigs go oink-oink, and anybody can notice that the canine language is represented by several dialects: compare bow-wow, barf-barf, and yap-yap. And yet, crash, crush, crack, and so forth rather obviously have something to do with onomatopoeia. People seem to have begun with the sound imitative complex kr and added a syllable, to make the words pronounceable. This may be a bit of a stretch, but the etymological principle behind my statement is (if a pun will be allowed) sound.

Old English had the verb breotan, which also meant “break.” It has been lost, except for its cognate brittle “liable to break, fragile.” Breotan lacks attested cognates, and its origin is unknown. But the fact remains that, like break, which had many cognates, it also begins with br-. Though today burst contains a well-formed group bur-, its most ancient form was brestan (in such groups vowels and consonants often play leapfrog—this process is called metathesis: compare Engl. burn and German brennen; the German verb has preserved a more ancient stage: the original form was brannjan; the Old English for run was rinnan alternating with iernan

By: LaurenA,

on 6/16/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

break,

anatoly liberman,

brake,

ablaut,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Like a few other essays I have written in the past, this one has been inspired by a question too long for inclusion in the “gleanings.” Are break and brake related? Yes, they are, but the nature of their relationship deserves a detailed explanation. Break is an ancient word. It has cognates in all the Germanic languages, and Latin frango, whose root shows up in the borrowed words fragile, fragment, and refract, is believed to be allied to it (the infix n may be disregarded for reconstructing the protoform).

The grammatical system of the Germanic (and other Indo-European) languages depended on vowel alternations of the type we still have in break ~ broke, rise ~ rose ~ risen, drink ~ drank ~ drunk, give ~ gave, and so forth. Vowels were arranged in non-intersecting sets and resembled parallel railway tracks. Occasional shunting was allowed, but each move required special dispensation. The principal parts of break in Old English were brecan (infinitive), bræc (preterit singular; æ, as in Modern Engl. man), and brocen (past participle). All the highlighted vowels were short. At that time, verbs like break (so-called strong verbs, which displayed such alternations) had four principal parts, because the preterit singular differed from the preterit plural (the modern language has retained this distinction only in be ~ was ~ were ~ been), but three will suffice for comparing break and brake. In the history of English, vowels have been shortened and lengthened so often, and so many later changes have interfered with the ancient system that the original state is hard to observe from the perspective of the modern language. The vowel of the infinitive underwent lengthening and diphthongization; this accounts for today’s sound shape of break. The past plural form has disappeared altogether, and the extant form broke has the vowel of the past participle, also lengthened and diphthongized.

While I am at it, I may mention that in Middle English the ending -en was usually shed (compare English and German infinitives: break versus brechen), but after a good deal of vacillation past participles retained it (so in broken, spoken, given, and so forth, though we have come ~ came ~ come, as opposed to German kommen ~ kam ~ gekommen). Yet when we are bankrupt, we go broke. From an etymological point of view, broke is the same word as broken. Also, those who can afford it wear bespoke suits; recently, bespoke has spread to computer technology. Bespoke is a variant of bespoken.

The system of vowel alternations, as in Old Engl. brecan ~ bræc ~ brocen, that is, e ~ æ ~ o, is called ablaut (a term coined by Jacob Grimm, the elder and the more famous of the two brothers, who did many things in addition to collecting folk tales), and each vowel represents what is technically called a grade of ablaut. If bræc had not been lost, the modern past tense of break would, most probably, have been brake (compare spake, the archaic preterit of speak). No reflex of bræc has survived, but

Posted on 6/9/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

UK,

london,

Geography,

A-Featured,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

Early Bird,

lane,

place names,

canary,

piccadilly,

buckingham,

Add a tag

From Garlick Hill to Pratt’s Bottom, London is full of weird and wonderful place names. We’ve just published the second edition of A.D. Mills’s A Dictionary of London Place Names, so I thought I would check out the roots of some of London’s most famous addresses.

Abbey Road (in St. John’s Wood): Developed in the early 19th century from an earlier track, and so named from the medieval priory at Kilburn to which it led. Chiefly famous of course as the name of the 1969 Beatles album recorded here at the EMI studios.

Baker Street: Recorded thus in 1794, named after the builder William Baker who laid out the street in the second half of the 18th century on land leased from the estate in Marylebone of Henry William Portman. Remarkably enough, Baker Street’s most famous resident (at No. 221B) was a purely fictional character, the detective Sherlock Holmes created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in 1887!

Buckingham Palace: The present palace stands on the site of Buckingham House 1708, so named after John Sheffield, Duke of Buckingham, who had it built in 1702 (on land partly leased from the Crown) and whose heir sold it to George III in 1762. This building was rebuilt and much enlarged in the 1820s and 1830s according to the designs of John Nash and Edward Blore, becoming Queen Victoria’s favourite town residence when she came to the throne in 1837. The site was earlier known as Mulbury Garden feild 1614, The Mulbury garden 1668, the walled garden having been planted with thousands of mulberry trees by James I who apparently had the grand idea of establishing a silk industry in London.

Canary Wharf: The grand commercial development with its massive 850ft tower (the highest building in the country), begun in 1987, takes its name from a modest fruit warehouse! Canary Wharf was the name given to a warehouse built in 1937 for the Canary Islands and Mediterranean fruit trade of a company called ‘Fruit Lines Ltd’. The name of the Spanish island of Canary (i.e. Gran Canaria, this giving its name to the whole group of ‘Canary Islands’) is of course also of interest: it is derived (through French and Spanish) from Latin Canaria insula, that is ‘isle of dogs’ (apparently with reference to the large dogs found here).

Drury Lane: Recorded thus in 1598, otherwise Drewrie Lane in 1607, named from Drurye house 1567, the home of one Richard Drewrye 1554. The surname itself is interesting; it derives from Middle English druerie ‘a love token or sweetheart’. The lane was earlier called Oldewiche Lane 1393, street called Aldewyche 1398, that is ‘lane or street to Aldewyche (‘the old trading settlement’).

Knightsbridge: Cnihtebricge c.1050, Knichtebrig 1235, Cnichtebrugge 13th century, Knyghtesbrugg 1364, that is ‘bridge of the young men or retainers,’ from Old English cniht (genitive case plural -a) and brycg. The bridge was where one of the old roads to the west crossed the Westbourne stream. The allusion may simply be to a place where cnihtas congregated: bridges and wells seem always to have been favourite gathering places of young people. However there is possibly a more specific reference to the important cnihtengild (‘guild of cnihtas‘) in 11th century London and to the limits of its jurisdiction (certainly Knightsbridge was one of the limits of the commercial jurisdiction of the City in the 12th century).

Piccadilly: This strange-looking stre

By: Rebecca,

on 6/9/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

Bosom,

hrether,

Reference,

language,

Breast,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

spelling,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

In today’s English, the letters u and o have the same value in mutter and mother, and we have long since resigned ourselves to the fact that lover, clover, and mover are spelled alike but do not rhyme. (Therefore, every less familiar word, like plover, is a problem even to native speakers.) Those who want to know more about the causes of this madness will find an answer in any introduction to the history of English. I will state only a few essentials. For example, the vowel of mother was once long, as in school, but, unlike what happened in school, it became short and later acquired its modern pronunciation, as happened, for example, in but. We still spell mother as in the remotest past. Medieval scribes had trouble with combinations uv/vu and um/mu (too many vertical strokes, “branches”) and preferred ov and om. That is why we write love and come instead of luv and cum (or kum). If I may give one more blow to a dead horse, these are the words that spelling reform should leave untouched: love and come are so frequent that tampering with them will produce chaos, even though luv appears in all kinds of parody.

Bosom, with its first o before s, looks odd even against this checkered background, though from a phonetic point of view it is not more exotic than mother. (The difference is that we become familiar with the written image of mother early in our education; also, other and smother produce a semblance of order, whereas bosom is unique in its appearance and is close to a poeticism.) Both mother and bosom had long o, as in Modern Engl. awe and ought in the speech of those who distinguish between Shaw and Shah (isn’t it a pleasure to have the privilege of choosing among aw, au, augh, and ough—compare taw, taut, taught, and ought—for rendering the same sound? In British English they also have or and our, as in short and court, on their menu). Consequently, if bosom were today pronounced like buzz’em, we might perhaps feel less baffled. And at one time it was pronounced so.

The first vowel in bosom alternated with its long partner as in booze and with u as in buzz until at least the end of the 18th century. The Standard Dictionary (Funk and Wagnalls), published in the United States in 1913, recommended the vowel of booze in bosom. Nor is this word an exception. Today it is hard to believe that the pronunciation of soot used to vacillate in the same way and could rhyme not only with loot but also with shut. Professionals, who dealt with soot on a daily basis, preferred the vowel of shut, but the tastes of their cleaner superiors prevailed. In British dialects, book, cook, look, and took often have the vowel of Luke. In what is called Standard English, bosom is now pronounced with a short vowel, and, all the historical elucidations notwithstanding, its spelling produces the impression of a typo. I have not yet met a beginner who would not mispronounce this word, though foreigners studying English are enjoined never to trust what they see, even when the word has the most innocent appearance imaginable (for example, one, gone, done, lone, pint, lead, read, steak, Reagan, and pothole, the latter somewhat reminiscent of Othello).

The etymology of bosom, from bosm, an old word with a long vowel, as noted, has not been found, even though the other West Old Germanic languages (this type of grouping excludes

By: Rebecca,

on 6/2/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

wiko,

“week”,

“week,

Reference,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

Week,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

weak,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

This is a weekly blog, and ever since it began I have been meaning to write a post about the word week. Now that we are in the middle of the first week of the first summer month, the time appears to be ripe for my overdue project.

In Latin there was the word calendae (plural) “the first day of the month.” These dates were “called out” or proclaimed publicly (from calare “proclaim,” not related to Engl. call, unless we take into account the fact that the syllables kal ~ kol ~ gal ~ gol designate “voice” in many languages; therefore, all such words may go back to the same sound imitative complex). The calendae were “called out” because interest was due on the first day of the month; therefore, money changers’ account books of interest got the name calendaria. Fortunately, our calendar (from Latin via Old French) does not remind us of debts and taxes only. Unlike calendar, week is possibly a Germanic word. Why “possibly” will become clear at the end of the post.

We will pass over the question about the origin of the seven day week but remember that, according to the Bible, the creation of the world took a week. Consequently, after the Christianization of Europe a word designating the seven day week had to be coined. Among the Germanic speakers the Goths were the first to be converted to Christianity (this happened in the 4th century), and long fragments of the Gothic Bible have come down to us, though almost only of the New Testament. As a result, we do not know how their bishop Wulfila translated, or would have translated, the Hebrew (or the Greek) word for “week.” The possibilities for naming the week are not too few. For example, Russian nedelia (stress on the second syllable), with cognates everywhere in Slavic, means “day on which no work is done”; the transference to “week” came later. A curious anti-parallel to nedelia may be Sardinian chida ~ chedda “week,” if, as has been suggested, it is a borrowing of Greek khedos “sorrow,” with reference to work and the “suffering” it entails. Yet for the Western translators of the Bible the main sources of inspiration were the ecclesiastic words containing the root for “seven,” namely, Latin septimana and Greek hebdomas. Hence Modern French semaine, Italian settimana, and Spanish semana. But Spanish also has hebdomada, and similar words have been recorded in many old and new Romance dialects.

We can now look at Germanic. In Gothic, the word wikon, the dative of the otherwise unattested wiko, occurred. It means “sequence” (not “week”!) and glosses Greek taxei, the dative of taxis (Engl. tactics, taxidermy, and taxonomy have its root). In the Latin version of Luke I: 8, ordine corresponds to Greek taxei and Gothic wiko. Old Engl. wice ~ wicu is akin to Gothic wiko, and at first sight their etymology poses no difficulty, for they seem to be related to the Germanic verbs for “move, turn; retreat; yield” (German weichen, Icelandic víkja, Old Engl. wician, and others). However, what exactly “moves” or “turns” during a week remains unclear, and various explanations have been offered, none fully convincing. Some Germanic cognates of week differ from the English noun considerably (compare German Woche and Danish uge), but they are still variants of the same word and mean the same, except Old Icelandic vika, which has two senses: “week” and “nautical mile.” Perhaps vika, before it acquired the meaning “week,” referred to the change of shifts in rowing. In my post on the etymology of Viking, I supported the idea that Vikings were called this fro

By: Rebecca,

on 5/19/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

etymology,

kibosh,

anatoly liberman,

“‘kibosh,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

The young Dickens was the first to record the word kibosh. We don’t know for sure how it sounded in the 1830’s, but, judging by the spelling ky(e)-, it must always have been pronounced with long i. The main 19th-century English etymologists (Eduard Mueller, Hensleigh Wedgwood, and Walter W. Skeat) did not include kibosh in their dictionaries. They probably had nothing to say about it, though Mueller, a German, hardly ever saw such a rare and insignificant word. Even in Webster it appeared only at the beginning of the 20th century and, as far as its etymology is concerned, was given short (very short) shrift: “Slang.” Suggestions concerning the origin of kibosh kept turning up in the popular press, but they were too fanciful to satisfy anybody. Dickens wrote the following in Sketches by Boz (“Seven Dials”): “‘What do you mean by hussies?’ interrupted a champion of the other party, who has evinced a strong inclination to get up a branch fight on her own account. (‘Hooroar,’ ejaculates a pot-boy in parenthesis, ‘put the kyebosk [sic] on her, Mary!) ‘What do you mean by hussies?’ reiterated the champion.” (In those innocent days, when one could have intercourse with one’s neighbors, ejaculate meant “exclaim.”) This passage has been reproduced in many works dealing with kibosh.

In 1901, discussion on kibosh resurfaced, and the following explanation, by M. D. Davis became widely known: “…English slang is indebted to these synagogues for another peculiar term, kybosh, signifying a trifling affair, a matter of no moment. The evolution of the word would puzzle a Skeat. Originally it meant eighteenpence, a trifling amount. It is still used in that sense. It consists of two words, the guttural chi = eighteen, and bosh = penny….The Hebrew for penny is poshet, abbreviated into posh, afterwards bosh. Consequently, kybosh is eighteenpence good in Jewish affairs, something of no value in ordinary transactions.” Regardless of a Skeat, the Skeat must have been irritated by this note, but in the absence of a valid proposal, he preferred to keep silent (a rare case in his life). One need not have Skeat’s perspicacity or be a specialist in Hebrew to see how weak Davis’s etymology is. When the name of a small coin is used to characterize a meager quantity, words like penny and farthing come up. Would anyone think of eighteenpence as the embodiment of smallness? And how could a word meaning “trifle” become part of an idiom for “finish off” (with the definite article before it)? Davis did not say that a similar idiom existed in Hebrew or that chibosh means “a trifle” in that language. According to him, “kybosh is eighteenpence good in Jewish affairs,” whatever that means. Incidentally, eighteen pence was not such a small sum in the early part of the 19th century.

The OED had no enthusiasm for Davis’s hypothesis and said only: “Origin obscure. (It has been stated to be Yiddish or Anglo-Hebrew),” with reference to the article quoted above. So far, that entry has not been modified. In addition to the phrase put the kibosh on, kibosh has been recorded with the meanings “nonsense, humbug,” “the proper style or fashion ‘the thing’” (as in the proper kibosh, the correct kibosh), and, surprisingly, “Portland cement.” Unless put the kibosh on arose as an alteration of some foreign idiom, we must assume that kibosh, a separate word, existed before the long phrase. It is hard to imagine that kibosh “stop” (noun), kibosh “nonsense,” kibosh “the proper thing,” let alone kibosh “Portland cement,” are four etymologically distinct words. So what was the proto-kibosh? Was it “nonsense”?

Charles P. G. Scott, the

By: Rebecca,

on 5/12/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

slang,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

rogue,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Slang words are so hard to etymologize because they are usually isolated, while language historians prefer to work with sound correspondences, cognates, and protoforms. Most modern “thick” dictionaries tell us that rogue, the subject of this post, is of unknown origin. This conclusion could be expected, for rogue, a 16th-century creation, meant “a wandering mendicant.” (Skeat attributes the original sense “a surly fellow” to it but does not adduce sufficient evidence in support of his statement.) Words for “beggar,” “vagabond,” and “scoundrel” often originate among beggars, vagabonds, and scoundrels. Not improbably, the first “rogues” called themselves rogues, but even if this is true, it in no way clarifies matters. We do not know where hobo, a much more recent coinage, came from; consequently, it should surprise no one that rogue, which appeared in a text in 1561, remains an unsolved etymological puzzle.

The first English etymological dictionaries were published in 1617 (John Minsheu) and 1671 (Stephen Skinner). Neither author had a clue to the origin of rogue, though for Minsheu it was contemporary slang. But he looked for the answer in a wrong direction and cited a Hebrew and a Greek look-alike as a possible etymon. Skinner thought of an Old English source and (predictably) found nothing of interest. The same holds for Franciscus Junius, the third most erudite English etymologist of the “prescientific” epoch. Other researchers made no progress either, for fanciful references to Dutch and to various English verbs beginning with an r took them nowhere (sterile guesswork can hardly be called an achievement). We seem to be in the same position as our distant predecessors, except that we can now say with a clear conscience: “Origin unknown.” However, something is known, and this “something” is not unimportant.

Quite early, rogue acquired the senses “knave” and “villain” and became a facetious term of endearment. Today we mainly apply it to scamps and mischievous persons, especially to the rogues prone to displaying a roguish smile. The main stumbling block (though it should have been a stepping stone) in reconstructing the history of rogue is French rogue “arrogant, haughty,” which, odd as it may seem, is evidently unrelated to arrogance. Arrogance and arrogant go back to the root of Latin arrogare “claim for oneself,” from the prefix ad- and rogare “ask” (compare interrogate and prerogative). If French rogue is not akin to arrogant, what is its origin? Friedrich Diez, the founder of Romance comparative linguistics, suggested that the French had borrowed rogue from Old Norse (Scandinavian) and cited Old Icelandic hrókr “rook; long-winded talker.” This rather improbable etymology has been questioned a few times, but it still appears, though not without some hedging, in the most authoritative dictionaries of French. Our greater concern is that, according to an opinion that has long since become dogma, French rogue is neither the source nor a cognate of Engl. rogue. Only the great German etymologist Friedrich Kluge thought otherwise (but he devoted a single line to the English word), and Skeat believed that the meaning of roguish had been influenced by French.

Similar Celtic words, such as Scottish Gaelic rag “villain; a thief who uses violence,” with a cognate in Breton, were noticed long ago. Judging by their geographical distribution, they are not loans from French. Nor does the French word look like a borrowing from Celtic. The OED offered no etymology of rogue and did not mention the oldest hypothesis on its origin. William Lambarde, a famous 16th-century author on legal matters, traced rogue to Latin

By: Kirsty,

on 5/11/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

UK,

Politics,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Dictionaries,

Early Bird,

monarch,

conservatives,

commons,

parliament,

labour,

pact,

hung,

minister,

prime,

hung parliament,

liberal democrats,

Add a tag

Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

For the first time in over 30 years, the British general election last week resulted in a hung parliament. The news is full of the latest rounds of negotiations between the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats, and at the time of writing, we still don’t know who will form the next government.

But what does ‘hung parliament’ actually mean? I turned to the Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics to find out.