new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: not recommended, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 157

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: not recommended in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

|

| Source: http://blogs.aaslh.org/big-questions/ |

In January, a reader wrote to ask me about

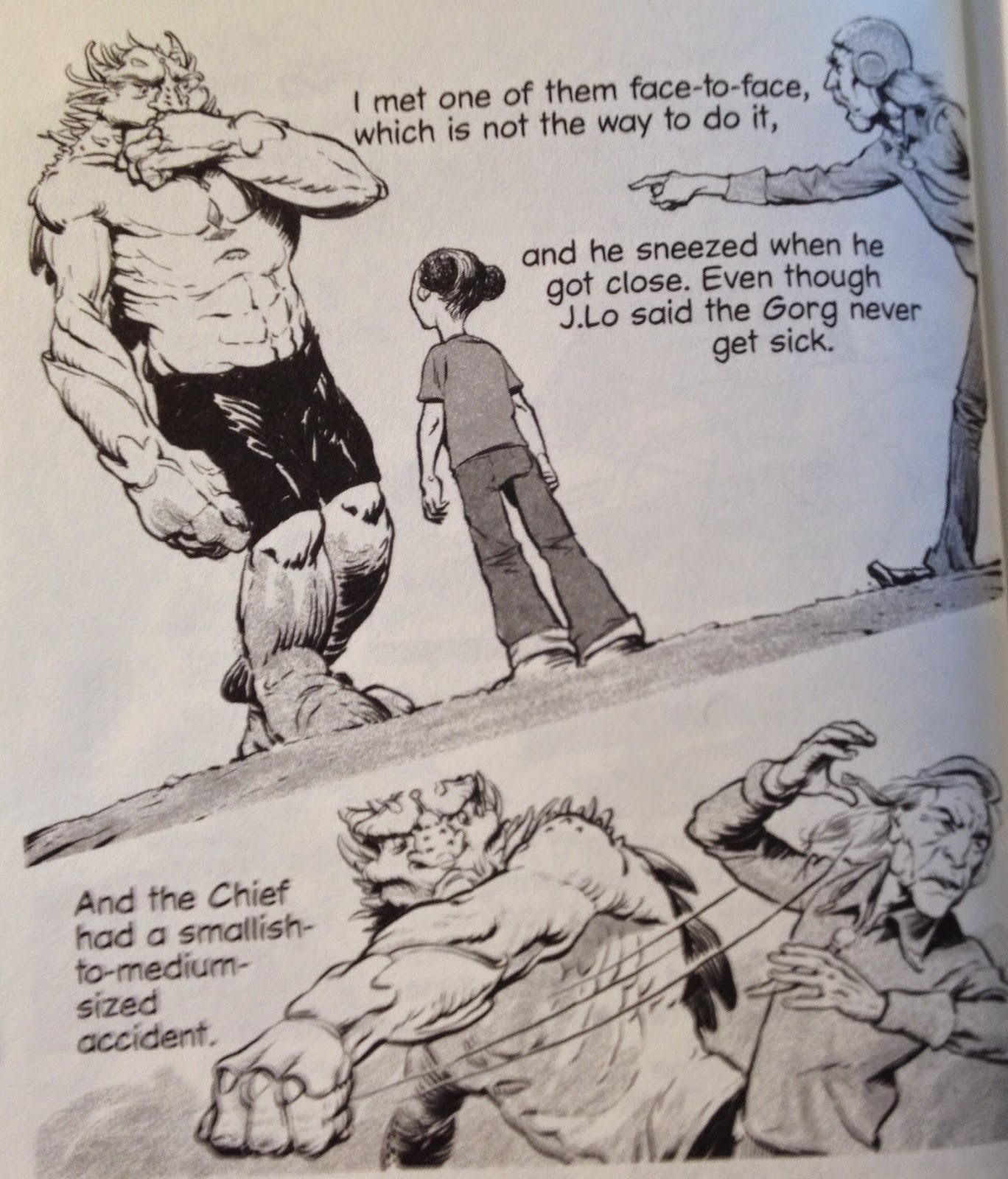

Dark Energy by Robison Wells. I got an ARC (advanced reader copy) from Edelweiss and read it last week. I have a lot of questions. The book itself will be released on March 29, 2016. Let's start with the synopsis:

We are not alone. They are here. And there’s no going back. Perfect for fans of The Fifth Wave and the I Am Number Four series, Dark Energy is a thrilling stand-alone science fiction adventure from Robison Wells, critically acclaimed author ofVariant and Blackout.

Five days ago, a massive UFO crashed in the Midwest. Since then, nothing—or no one—has come out.

If it were up to Alice, she’d be watching the fallout on the news. But her dad is director of special projects at NASA, so she’s been forced to enroll in a boarding school not far from the crash site. Alice is right in the middle of the action, but even she isn’t sure what to expect when the aliens finally emerge. Only one thing is clear: everything has changed.

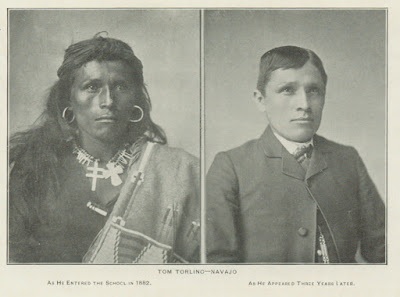

The synopsis doesn't tell us that Alice is "half Navajo." Her dad is white; her deceased mom was Navajo.

Back in January, I noted that I was interested in the author's note.

I'll begin with it. There, Wells writes that he used to live on the Navajo reservation. Because he wanted to be respectful "of the tribes and ancestors of tribes mentioned in the book" he sent the manuscript out to several readers. He names seven individuals (Orlando Tsosie, Sammy Jim, Thomas Begay, Angelina Begay, Nadine Padilla, Susie Sandoval, and Thomasita Yazzie). Some of their surnames are clearly Navajo. Wells listened to what they had to say:

The small amount we see of ceremony and meeting with the Elders is a very whittled down version of a real Navajo ceremony. Originally we saw all of it, but the Navajos I spoke to--with only one exception--said it was too sacred to depict. I cut it back and and back until they were satisfied.

I am glad to read that Wells cut it more than once until his readers were satisfied. But--I have many questions, because equally important to the story Wells tells are Pueblo peoples. He doesn't say he sent the manuscript to Pueblo Indian readers. I'm not sure what I'd have said...

Let's back up.

From the synopsis, we know an alien ship has crashed in Iowa and that Alice's dad has to go there. The boarding school Alice is sent to is the Minnetonka School for the Gifted and Talented. Soon after Alice and her dad get to the site, the aliens start to emerge. The US government welcomes them and through a translator, figures out they call themselves the Guides. All but two are housed in a tent city next to the giant ship.

The school's gifted and talented student body is important to the story. Alice and her friends befriend the two Guides (these two are a brother and sister). Brynne, one of the Minnetonka students, tests the DNA of the girl alien (they call her Coya) and finds out that she's not an alien at all. She is human. Another student who is into languages records some of Coya's words, analyzes them, and figures out that Coya and her brother are speaking a Pueblo language:

"Keresan is a language spoken by half a dozen tribes in New Mexico. They're Pueblo tribes. Acoma, Laguna--those are the ones I've been to. There are others to the east."

Brynne says:

"...the DNA databases I've searched say they're not any one of those tribes, but they have markers for being an older tribe that those are descendants from."

Alice says:

"the language is like a puebloan nation, but not. And the DNA is like a puebloan nation, but not. Are we talking about the Anasazi here?"

The conversation continues, with Brynne and Rachel giving the rest of the group some information about the Anasazi, including that the preferred name is Ancestral Puebloans.

So--Coya and her sibling and the Guides who were on that ship are not aliens. They're Ancestral Puebloans who were abducted by some bad aliens (they're called Masters), who we'll learn later, look like lizards. These bad aliens enslaved the Ancestral Puebloans and used them as incubators for parasites the Masters grow till they become like the Masters, too. How all that becomes known is laid out in the story in a gruesome discovery when Alice and her friends go onto the ship and find bloody rooms where, Alice's dad tells her, they think thousands committed mass suicide after puncturing their abdomens.

Are you unsettled by any of that? I am, and while that part of

Dark Energy has nothing to do with ceremony, it does a few things that I would have asked Wells to revisit.

This alien abduction idea is one that appears here and there. As I did some research, I read that tourists tell tour guides at Chaco Canyon that abduction story. It is part of an X-Files episode, too. All of this feeds into New Age activity that is harmful to the sites, which have significance to us today. Will

Dark Energy inadvertently encourage that abduction idea? Maybe, maybe not. Either way, consider sacred or significant aspects of your own spiritual or cultural or religious life and how they are (or could be) exploited by others who don't understand those ways.

I wonder if Wells took the feelings of Pueblo people into consideration? Why did he not ask Pueblo readers to read his manuscript? I think I can offer an answer. The entire story is dependent on abducted Ancestral Puebloans. If I said "no, don't go there," I can't imagine how this story could be told. Can you?

Another thread that I am uncomfortable with is the ways in which Alice and her friends go about teaching "our culture" to Coya. There are places in the story where Alice says something that tells us she's well aware of politics, history, and oppression of Native peoples, but there are other places where that orientation disappears, like when teaching Coya "our" culture. Alice is clearly a US teen, into things most other US teens are into, but for me, she slips in and out of a Navajo orientation in ways that I find jarring. At one point she talks sarcastically about small pox, and then at this "our culture" part, there's this:

It was amazing the things that she didn't have any concept of: awards, winning, competition, prizes.

And there is another part where another student (he's from India and has applied for US citizenship) and Alice are talking about what the government will do with the Guides. He says:

"I wonder what they'll do about the Guides' citizenship. They landed in America--does that make them American? It's not like we can load them on a bus and send them back to where they came from. Besides, from what you said, putting them on a bus would just be shipping them back to Mesa Verde, right?"

"I don't see us creating a new little nation for them, I said. "We've seen how well that's worked out in the past, with Native American reservations."

"I don't know what they'll be," I said. "These Guides are going to need a lot of education, and they don't have any money. Are we just going to give them free houses?"

See? Her voice, her orientation, her political knowledge.. it seems uneven, or, inconsistent.

As the story draws to a close, Alice and her friends are running, along with Coya and her brother, to the Navajo reservation where a ceremony will be done by a Hopi man who talks of monsters who came from the sky, and, a bundle with the skull of one of those monsters. It isn't clear to me who does a sandpainting of the ship... is it a Navajo man or the Hopi one? I can't tell, but, we learn that the Hopi learned how to kill the monsters, using a poison they make from juniper berries, dried insects, and dried flowers. Arrows are dipped into that poison. Alice and her friends go to Chaco Canyon, the Masters/Monsters arrive there.

Alice talks with one (through a translator mechanism that Coya and her brother have been using). It is angry. It asks her if she knows what her friends have cost his people. She says they're

her people. It replies:

"What do you mean 'your people'? These slaves were taken from this weak little planet more than eight hundred of your Earth years ago. We took only what we needed--we bred the rest. Your population is exploding. You seem to have more than enough to spare a few."

Some dramatic fighting ensues, but those poison tipped arrows do the trick. The four Masters/Monsters are killed.

These parts about enslavement are meant to make a point about enslavement of Africans and they're the part about history that the Kirkus reviewer referenced, but I don't know... It doesn't sit well with me.

What Wells does in

Dark Energy is too over-the-top and, as noted earlier, the abduction/alien theme plays into New Age abuses of our ancestral sites. I've read and re-read what I've written here, trying to bring it into a useful and coherent sharing of my thoughts, but I feel confounded by what I read in

Dark Energy. Obviously, I've decided to stop trying and just hit the upload button.

Published in 2016 by HarperCollins (a major publisher), I conclude with this: I do not recommend

Dark Energy by Robison Wells. I invite your thoughts.

Back in January, a reader wrote to ask me about Emily Henry's The Love that Split the World. I've now gotten a copy, read it, and am working on an in-depth review of it.

However! Last week I learned it was being picked up by Lionsgate. If all goes according to plan, it will be a movie. That troubled me deeply because of the errors I found in the book.

I started tweeting about it, and got some pretty fierce pushback from people who are friends of the writer.

If you're interested in the tweets and my response to the pushback, I created two Storify's about them (Storify is a way to capture a series of tweets in a single place.) I've also got them available as pdf's--let me know by email if you want a copy of the pdf.

Here's the first one:

What Emily Henry got wrong in THE LOVE THAT SPLIT THE WORLDAnd here's the second one:

Derailing Native Critique of THE LOVE THAT SPLIT THE WORLD

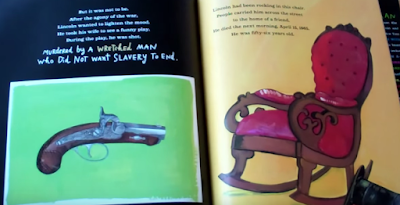

With President's Day upon us, people are pulling out picture books about Lincoln, like Maira Kalman's Looking at Lincoln. The child in the book reveres Lincoln. Most Americans do, I think, but what we know about him is... incomplete.

What do you know about Lincoln and Native peoples?

Most people do not know that he issued an order for the mass execution of 38 Dakota men. It was the largest mass execution in the United States. That is not included in Kalman's book.

Is mass execution not age appropriate? Violence is ok, as these pages demonstrate.

One page shows a uniform with a bullet hole in it:

And there's a page showing a numbered grave:

And Kalman includes a page about Lincoln's assassination:

So.... what to make of decisions of what to include, and what not to include. Of course, her book--or any book--can't include everything. True enough, but I wonder what we'd find if we started looking carefully. Would we find it in any books?

Earlier in the book, the little girl goes to a library and finds out there's over 16,000 books about him. I wonder how many of those are for children and young adults, and of them, I wonder if any of them include that mass execution?

What do you think about what is included, and what is not included?

The Crow's Tale by Naomi Howarth came out last year (2015) from Frances Lincoln Children's Books. That's a publisher in London.

The complete title of Howarth's book is The Crow's Tale: A Lenni Lenape Native American Legend.

In her "About the story" note, Howarth writes:

The Rainbow Crow -- a Pennsylvania Lenni Lenape Indian legend--is the perfect example of a story that was first told to explain the mysteries of the natural world. When I came across this beautiful tale, my imagination was immediately soaring with Rainbow Crow across wide winter skies and landscapes. The tale has been passed down through generations of Lenni Lenape Indians, mostly orally, and I have tried to remain true to the narrative, although I have visualized the Creator as the Sun, as I wanted to make the Sun a character in his own right.

On her website page for the book, I see this:

Inspired by a Lenape Native American myth, this beautiful debut picture book shows how courage and kindness are what really matter.

Yes, courage and kindness matter, but so do other things. Clearly Howarth felt that she was doing a good thing with this story.

I have several questions.

What is the source Howarth used for this story? She doesn't tell us, which means we can't tell if her source is legitimate, or, if it is amongst the too-many-made-up stories attributed to Native peoples. Without that information, teachers are in a bind. Can they use this book to teach students about Lenni Lenape people and culture?

Is Howarth's story a Lenni Lenape one if she changed a key part of it? She tells us that she visualized Creator as the sun. Could she (or anyone) do that--say--with the Christian God and still call that story a Christian one? Maybe, but I think most people would say that doing so would be tampering with a religion in ways that border on sacrilege. How do the Lenni Lenape people visualize Creator? Did she talk with them, to see if she could depict Creator as the sun?

By "them" I mean--did Howarth talk with someone who has the authority to work with her on this project? Increasingly, tribal nations are working to protect their stories by setting up protocol's researchers and writers should use if they're going to do anything related to their people, history, culture, etc.

As we might predict, Howarth's book is well-received in some places. This morning I read that this story is on the

shortlist for a 2016 Waterstones Children's Book Prize. If you're in the UK, or if you know people in the UK who are on the committee, please ask them these questions. You could ask Howarth, if you know her, or her editor (I don't know who that is). Asking questions is what leads to change.

Published in 2015,

The Crow's Tale by Naomi Howarth is not recommended.

A reader sent me some photos of Eric Carle's Have You Seen My Cat? First published in 1973 by Little Simon, it looks like it may have first been published in German, in 1972. It is a Ready To Read book. It is also available as a board book. You can also get it in Dutch. Or Afrikaans.

Here's the synopsis:

In Eric Carle’s charming and popular story, Have You Seen My Cat?, a little boy worries about his missing cat and travels to different places in search of his pet. The boy encounters numerous feline counterparts as he searches, including lions, leopards, and tigers—but it isn’t until the last page that he finally finds his missing pet!

Is this kid a time traveler?! Or, is he going to Hollywood movie sets?! What I'm getting at is this: the illustrations depict people--who are not like the, shall we say American white boy--as exotic. This is just like we saw in 2015's much acclaimed

Home, by Carson Ellis. Remember that?!

I wrote about them, and so did

Sam Bloom at

Reading While White. Here. Take a look at some of the illustrations in

Have You Seen My Cat? This is a page from the Chinese board book edition:

Here's two pages from a video of someone reading the Ready to Read edition:

I'm going to be a bit snarky here...

Have you seen this book? Is it on your shelf?

Editor's Note: Beverly Slapin submitted this review essay of Paul Goble's Custer's Last Battle: Red Hawk's Account of the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Slapin uses quotation marks around the name "Red Hawk" because that is a fictional character. Slapin's review may not be used elsewhere without her written permission. All rights reserved. Copyright 2016. Slapin is currently the publisher/editor of De Colores: The Raza Experience in Books for Children. ______________

Goble, Paul, Custer’s Last Battle: Red Hawk’s Account of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, with an introduction by Joe Medicine Crow. Wisdom Tales / World Wisdom, 2013.

Each year on June 25, Oglala Lakota families at Pine Ridge gather to celebrate the Lakota people’s victory at the Battle of the Greasy Grass, where, in 1876, as Oglala author and activist Debra White Plume says, “Custer wore an Arrow Shirt.”

“Warriors get ready,” the announcer calls. “Be safe, and thank your horse when you’re done.” The warriors, mostly teens, race off to find and count coup on the white guy who’s volunteered to stand in for Custer. No one knocks him off his horse, but they take his flag. “Our ancestors took that flag from the United States of America,” White Plume says, smiling. “We’re the only people who ever did.”

“I think it’s important,” she continues, “for the young men and young women to receive the training of the Warrior Society as our ancestors lived it, because that’s where the important values are played out, like courage and helping your relative and taking care of your horse and taking care of the land. All of that was important to us then and is important to us now.”

How different the people’s reality is from “Red Hawk’s” lament at the beginning of Goble’s story:

We won a great victory. But when you look about you [sic] today you can see that it meant little. The White Men, who were then few, have spread over the earth like fallen leaves driven before the wind.

Goble’s new edition of his first-published book contains a revised “narrative,” a new Author’s Introduction, and a short Foreword by Crow historian Joe Medicine Crow, whose grandfather had been one of Custer’s scouts. According to Goble himself, “The inclusion of the Foreword by Joe Medicine Crow… gives the book a stronger Indian perspective.” Of the 20 sources in Goble’s reference section, only two are Indian-authored—My People, the Sioux and My Indian Boyhood—both by Luther Standing Bear, who was not at the Greasy Grass Battle (because he was only eight years old at the time).

In the two previous editions of Red Hawk’s Account of Custer’s Last Battle, Goble acknowledges the aid of “Lakota Isnala,” whom one might presume to be a Lakota historian. He was not. In this 2013 edition, Goble finally discloses that “Lakota Isnala” was, in fact, a Belgian Trappist monk named Gall Schuon, who was adopted by Nicolas Black Elk. Custer’s Last Battle, writes Goble, is his fictional interpretation of Fr. Gall Schuon’s interpretation of John G. Neihardt’s interpretation of Nicolas Black Elk’s story. (And there has been much criticism by scholars—and by Black Elk’s family—of Neihardt’s exaggerating and altering Black Elk’s story in order to increase the marketability of Black Elk Speaks.) In other words, Goble’s book is a white guy’s interpretation of a white guy’s interpretation of a white guy’s controversial interpretation of an elder Lakota historian’s oral story, which he related in Lakota. Finally, at the end of his introduction, Goble writes, “Wopila ate,” which is probably supposed to mean, “Thank you, father.” Except it doesn’t. “Wopila” is a noun and means “gift.” So, “wopila ate” would mean, “gift father,” which is just a joining of two unrelated words. “Pilamaya,” which is a verb, means “thank you.”

Returning to Goble’s introduction, there’s this:

Because no single Indian account gives a complete picture of the battle, Indian people telling only what they had seen and done, I added explanatory passages in italics to give the reader an overview of what might have taken place…

In truth, Native traditionalists in the 1800sdid not offer linear recitations of events. Rather, they narrated only those events in which they had participated. Sometimes historical records consisted entirely of these narratives. Sometimes contemporaneous Indian historians, such as Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa), assembled credible historical records. Sometimes persons from outside the culture, who knew and respected the Indian traditionalists, successfully assembled written records of oral narratives.And there certainly is, today, a wealth of material, much of it put together by descendants of those who fought in the Greasy Grass Battle.

In the same paragraph, Goble writes,

[T]here were no survivors of Custer’s immediate command, and there has always been considerable controversy about exactly what happened.

By limiting his discussion (and the story) to the casualties of Custer’s “immediate” command, Goble sidesteps the reality that, although five of the 12 Seventh Cavalry companies were completely destroyed, there were many survivors in the other seven. And, according to the histories passed down by Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho traditionalists, there was never any “considerable controversy about exactly what happened.” In one of the major battles, for instance, it’s said that as the fighting was coming to an end, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse saw no sense in continuing. Rather, Crazy Horse posted snipers to keep the surviving Blue Coats behind their barricades—watching helplessly as he and his thousands of warriors returned to camp to help take down their lodges and move south.

So, to be clear, there is nothing in Goble’s fictional Indian narrator’s voice, accompanied by Goble’s explanatory passages—even if they were accurate and appropriate, which they’re not—that might add anything of value for children or anyone else.

Piling romantic metaphor onto romantic metaphor appears to be Goble’s way of trying to imitate “Indian” storytelling style, which it doesn’t. Toward the beginning of the story, for instance, “Red Hawk” describes Crazy Horse: “A tomahawk in his hand gave him the power of the thunder and a war-bonnet of eagle feathers gave him the speed of the eagle.” Goble’s magical tomahawk stuff notwithstanding, Crazy Horse never wore a headdress. Following instructions given to him in an early vision, Crazy Horse always dressed plainly, wearing one eagle feather in his hair and a single stone tied behind one of his ears; and, before engaging in battle, he rubbed his body with dust.

Besides being mired down with cringe-worthy metaphor and misinformation, Goble’s fictional narrative paints the Lakota people as “brave yet doomed.” Here, for instance, “Red Hawk” relates the camp’s panicked response to an impending cavalry attack:

In an instant everyone was running in different directions…. The air was suddenly filled with dust and the sound of shouting and horses neighing. Dogs were running in every direction not knowing where to go…. Warriors struggled to mount their horses, which reared and stamped in excitement, while women grabbed up their babies and shrieked for their children as they ran down the valley away from the oncoming soldiers. Old men and women with half-seeing eyes followed after, stumbling through the dust-filled air. Medicine Bear, too old to run, sat by his tipi as the bullets from the soldiers’ guns already splintered the tipi-poles around him. “Warriors take courage!” he shouted. “It is better to die young for the people than to grow old.”

Goble’s melodrama notwithstanding, the Indian camps were extremely well organized. In times of war, everyone knew what to do. Children were protected, as were elders—not abandoned, helplessly sitting around “splintered tipi poles” or “stumbling through the dust-filled air.” Compare Goble’s fictional “narrative” above with a piece from Joseph Marshall III’s In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse, in which Grandpa Nyles explains what happened to his grandson:

It was customary for Lakota wives and mothers to hand weapons to their husbands and sons. And they had a saying that gave them encouragement and reminded them of their duty as warriors…. The women would say, “Have courage and be the first to charge the enemy, for it is better to lie a warrior naked in death than it is to run away from the battle.”…It means that courage was a warrior’s best weapon, and that it was the highest honor to give your life for your people.

And. Goble’s description of “shrieking” women is taken from the many outsider accounts of “wailing” women. In reality, the camp women were singing Strong Heart songs to give their warriors courage as they rode off to battle.

And. “Red Hawk’s” recounting of what Medicine Bear said seems to have been “borrowed” from Luther Standing Bear’s Land of the Spotted Eagle. But what Standing Bear really wrote was this:

When (I was) but a mere child, father inspired me by often saying: “Son, I never want to see you live to be an old man. Die young on the battlefield. That is the way a Lakota dies.” The full intent of this advice was that I must never shirk my duty to my tribe no matter what price in sacrifice I paid…. If I failed in duty, I simply failed to meet a test of manhood, and a man living in his tribe without respect was a nonentity.

More misinformation: Toward the end of “Red Hawk’s” story, he says, “White Men have asked me which man it was who killed Long Hair. We have talked among ourselves about this but we do not know. No man can say.”

Although there may not be written narrative accounts of who killed Custer, Indian people know it was Rain-In-The-Face. Besides the oral stories that have been handed down, there exist Winter Count histories in pictographs, which are at least, if not more, reliable than histories written by outsiders. On one particular Winter Count, the pictograph detailing the most important event of that specific year, or winter, shows Rain-In-The-Face (along with his name glyph, or signature tag, of rain falling in his face) firing a rifle (with smoke coming out of it) directly at Custer (who is shown with long hair, falling backwards).

For the most part, and for cultural and pragmatic reasons, Indian people at the time did not have a lot to say to white people about their participation in the Battle of the Greasy Grass. Dewey Beard, for instance, said only that: “The sun shone. It was a good day.” But Goble chose to rely on the easily available written versions, rather than on the oral and pictograph versions—which he probably would not have understood or respected anyway.

In what has come to be known as ledger art, the Indian artists used basic media of whatever was available—crayon, colored pencil, and sometimes ink—on pages torn out of discarded ledger books. What they created was art of great beauty. Early ledger art related the histories of the great battles, the buffalo hunts, and other scenes from their lives. In the battle scenes, there were iconic name glyphs over the heads of individual warriors to identify them. There were handprints on their horses—coup marks—to show that these horses were war ponies, that they and their riders had previously seen battle. There were horses of many colors—reds, yellows, purples, and blues—because people who really knew horses could see their many shades. There were hoof prints at the bottom of the pages to denote action. The warriors shown often carried the prizes of war that they had taken from the enemy—US flags, cavalry sabers and bugles—that represented power. And often, there were wavy lines coming out of the mouths of the warriors as they charged, to symbolize that they were “talking” to the enemy—“I’m not afraid of you!” “I’m coming to get you!”

Although the details were generally the same or similar, techniques varied from tribe to tribe. According to Michael Horse, a talented contemporary ledger artist and historian, Cheyenne and Lakota styles, for example, were mostly stick figures, while Kiowa and Comanche styles were more realistic.

Even after people had been incarcerated in the prisons and on the reservations, these ledger paintings represented freedom and bravery.

On the other hand, Goble, as a European transplant, has transplanted his European aesthetic and style onto his “Indian ledger art.” It’s clear that he has looked at—maybe even studied—the old ledger paintings, taken what elements or designs he considers important or typical or romantic, and discarded the rest. His paintings are devoid of the historical and cultural content that were so important in the originals—they have no story and no spirit. All of Goble’s warriors are decked out in regalia and carrying weaponry—much of it unbelievably cumbersome—yet none of the warriors is identified by a name glyph, so we don’t know who they are. The warriors are not shouting at their enemies—they don’t even appear to have mouths. There are no symbolic, brightly colored war ponies—Goble’s “Indian” ponies exist only as blacks, browns, roans and an occasional gray. None of the ponies has a coup sign. There are no hoof prints, so there is no motion—just ponies and their riders suspended in space and time. They are indistinguishable, with a lack of identity, a lack of action, and a lack of Indian reality.

It would not be a stretch to say that Paul Goble does not know—and probably does not care to know—how to read Indian ledger art. Rather, it would seem that he perused actual direct statements from the original artists and saw only “decorative motifs” to be kept or discarded. I would also opine that Goble does not regard Indian ledger artists—traditional or contemporary—as artists.

Speaking at a conference a few years ago, Joseph Bruchac coined the term, “cultural ventriloquism,” to refer to the many non-Native authors who create “Native” characters that function as dummies to voice the authors’ own worldviews. So it would not be a stretch to imagine that Goble’s “using the voice of a (fictional) Indian participant” and “illustrat[ing] the picture pages in the style of ledger-book painting” are to showcase his own art by pretending to make this whole thing authentic. As such, Custer’s Last Battle can in no way be considered an Indian perspective of an historical event. It’s not even a well-told story that approximates an Indian perspective. It wasn’t successful in 1969 and it’s not successful now.

Returning for a moment to Goble’s introduction. He writes,

I grew up believing that Indian people had been shamefully treated, their beliefs mocked, their ways of life destroyed. I tried to be objective in writing this book, but for me the battle represented a moment of triumph, and I wanted Indian children to be proud of it. (italics mine)

Plains perspectives of the Battle of the Greasy Grass are not difficult to understand and do not need to be interpreted by someone from outside the culture. Plains traditional narratives are not incomplete and do not need to be rewritten by someone from outside the culture. Plains traditional and contemporary ledger art forms are not primitive and do not need to be fixed by someone from outside the culture. The children at Pine Ridge, against all odds, are holding on to their traditions, histories, arts, and cultures. The last things they need are fake narratives and fake art, combined with a cultural outsider’s arrogance and sense of entitlement—to “give” them pride.

—Beverly Slapin

References

There are many excellent sources of information about the Battle of the Greasy Grass; biography, fiction and nonfiction about the people who lived in that time period; and historic and contemporary ledger art. This is by no means an exhaustive list.

An outstanding short film, produced by the Smithsonian and from an Oglala perspective, is “The Battle of the Greasy Grass,” and might be a good beginning for study (grades 4-p).

For information about the Battle of the Greasy Grass or that era, see:

Edward and Mabel Kadlecek, To Kill an Eagle: Indian Views on the Last Days of Crazy Horse

Joseph Marshall III:

The Day the World Ended at Little Big Horn: A Lakota History (2007)

In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse (2015)

The Long Knives are Crying (2008)

Soldiers Falling Into Camp: The Battles at the Little Rosebud and the Little Big Horn (2006)

Luther Standing Bear, Land of the Spotted Eagle

James Welch and Paul Stekler, Killing Custer: The Battle of Little Big Horn and the Fate of the Plains Indians

For examples of, and information about, traditional ledger art, see:

Howling Wolf and the History of Ledger Art by Joyce M. Szabo (University of New Mexico Press, 1994)

For examples of, and information about, contemporary ledger art, see:

See To Kill an Eagle: Indian Views on the Last Days of Crazy Horse by Edward and Mabel Kadlecek, who lived near Pine Ridge and listened to the stories of Indian elders who had known Crazy Horse.

Some of the best accounts of this historic battle, in fiction and nonfiction, include: Killing Custer: The Battle of Little Big Horn and the Fate of the Plains Indians by James Welch (Blackfeet / Gros Ventre) and Paul Stekler (1994); Welch and Stekler also collaborated on the important documentary, “Last Stand at Little Bighorn.” There’s alsoThe Day the World Ended at Little Big Horn: A Lakota History (2007), The Long Knives are Crying (2008) and Soldiers Falling Into Camp: The Battles at the Little Rosebud and the Little Big Horn (2006) by Joseph Marshall III (Sicangu Lakota), as well as Marshall’s new children’s book, In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse (2015). See a description of this maneuver, for example, in Marshall’s In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse, pp. 120-121. Each Winter Count pictograph portrays the most important event that occurred in a particular winter, or year. It could be a major battle, or an outbreak of disease, or the death of a leader, or something else. The pictograph that represents 1876 shows the killing of Custer at the Battle of Greasy Grass.

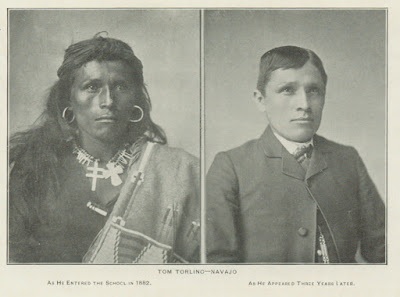

Some months ago, I learned that Lori Piestewa was being written about in a book by Nancy Bo Flood. My immediate reaction was similar to the reaction I had in 1999 when I read Ann Rinaldi's My Heart Is On The Ground. In preparation for her book on Native children at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Rinaldi visited the cemetery there. She used the name of one of the children buried there as a name for one of her characters. That--and many other things about her book--astonished me. What happened to Native Nations and our children because of those schools is something we have yet to recover from. Rinaldi using the name of one of those children was wrong.

Flood is doing that, too.

Soon after the Iraq War began in 2003, Lori Piestewa was killed in Iraq. Her death was felt by people across Native Nations, who started a movement to rename "Squaw Peak" in her honor. Janet Napolitano (she was the governor of the state of Arizona at that time; the Hopi Nation is in Arizona) supported the move. Though it was a difficult change to make (due to governmental regulations), it did take place. What was once "Squaw" Peak (squaw is a derogatory term) is now Piestewa Peak. Each year, there are gatherings there to remember Lori Piestewa. Her family is at those gatherings, as are many Native people.

Tess--the main character in Flood's Soldier Sister, Fly Home--is Navajo. The story opens on the morning of a "ceremony" for Lori. Tess and her parents will go to it, but her older sister, Gaby won't be there because she is in the service. Tess is angry that her sister enlisted in the first place, but also angry that Gaby can't be at the service. The reason? Gaby and Lori were friends (p. 14):

Lori was the first of my sister's friends to join, the first to finish boot camp, the first deployed to Iraq. "Nothing fancy, nothing dangerous," Lori had emailed. "I'll help with supplies, help the soldiers who do the fighting. They're the real warriors. Before you know it, I'll be back."

It is implied that Lori wrote to Gaby. That passage feels wrong to me, too. Several news articles report that Lori sent an email to her mother. In it, she said "We're going in," and "Take care of the babies. I'll see you when I get back." Whether she used Lori's actual words or ones she made up and attributed to Lori doesn't matter. What matters is that she did it in the first place.

The "ceremony" for Lori that Tess and her parents go to bothers me, too. It is going to be held in a gymnasium in Tuba City. When they get there, Tess sees that there are "three large wide drums clustered together." Three different times during this "ceremony," the drumbeat is described as "boom-BOOM."

In newspaper accounts, I find that there was a memorial service held for her in a gymnasium in Tuba City on April 12, 2003, but I don't find any descriptions of it. What is important, is that it was a memorial. Not a "ceremony." At these kinds of Native gatherings (many are held in gyms, so that is not a problem with Flood's story), there is a drum and honor guard, but no "ceremony" of the kind that is implied. And characterizing the sound of the drum as "boom-BOOM" is, quite frankly, laughable.

On page 14 of

Soldier Sister, we read that Tess's mother is going to give Lori's family a Pendleton blanket. Tess remembers her sister in that gym, standing at center circle ready to play basketball (p. 15):

Today Lori's mother stood in that circle, wrapped in a dark-purple blanket. Purple, the color of honor. Fallen Warrior. On each side of her stood two little children, Lori's children. Did they hope Lori would come home and surprise them?

Surprise them?! That part of that passage strikes me as utterly callous and lacking in sensitivity for Lori's children and family.

It is possible that, at the actual service that happened that day (news accounts indicate her family was given Pendleton blankets are other memorials since then), someone gave Lori's family a Pendleton blanket. It may have been one of the

Chief Joseph blankets. They're available in purple. Pendleton blankets figure prominently throughout Native nations. I've been given them, and I've given them to others, too.

I doubt, however, that a purple one was chosen because purple signifies honor to Hopi or Navajo people. Purple carries that meaning for others, though. In the US armed services, for example, there's the Purple Heart.

All of what I find in Soldier Sister, Fly Home

that is specific to Lori Piestewa, is cringe-worthy.

In the back of the book, Flood writes at length about getting Navajo consultants to read the story to check the accuracy of the Navajo parts of the story and her use of Navajo words, too. There is no mention of having spoken to anyone at Hopi, or anyone in Lori Piestewa's family, about this story.

In her "Acknowledgements and Author's Note," Flood writes that (p. 153):

A percentage of the royalties from the sale of this book will be contributed to the American Indian College Fund to support the education of Lori's two children.

That, too, is unsettling. Using her children to promote this book is utterly lacking in grace. It may sound generous and kind, but the reality is that most authors have day jobs. They can't support themselves otherwise. Various websites indicate that an author may receive 10% (or up to 15%) of the sale of each book. Amazon indicates the hardcover price for this book will be $16.95 (it is due out in August of 2016). If we round that to $17.00 and use the 10% figure, Flood could get $1.70 per book. How much of that $1.70 does she plan to send to the American Indian College Fund? Did she talk with Lori's parents (Lori's children live with them) about this donation?

Given that Flood specifically names many Navajo people who helped her with this book, the lack of naming of Hopi people makes me very uneasy. Without their names, it feels very much like Flood is exploiting a family and a people. For that reason alone, I can not recommend this book.

I could continue this review, pointing to problems in the ways Flood depicts Tess as a young woman conflicted over her biracial identity. Doing that would help other writers who are developing biracial characters, but I think I'll save that for a stand-alone post.

Soldier Sister, Fly Home by Nancy Bo Flood, published by Charlesbridge in 2016, is not recommended.

Earlier this month I received a review copy of Talasi, A Story of Tenderness and Love. Written by Ellen S. Cromwell and illustrated by Desiree Sterbini, it purports to be about a Hopi child. The author is not Native.

Here's some of my notes:

Page 6

Talasi is the little girl's name, which, the author tells us "comes from corn tassel flowers that surround her pueblo home in Arizona."

I think readers are meant to think that her name may be a Hopi name. Let's pause, though, and think about that. The word tassel is an English word. The Hopi have their own language, and likely have a word for tassel. Wouldn't the child's name reflect that word rather than the English one?

As regular readers of American Indians in Children's Literature know, my grandfather is Hopi. I've been to Hopi. Homes on the mesas aren't surrounded by corn fields. The mesas are, so maybe that is what the author means, but written as-is, it reminds me more of farms in the midwest where homes are surrounded by corn fields.

Page 7

There's an error about materials used to build homes. The text says that "dwellings" (that word, by the way, sounds like an anthropologist, not a storyteller) are made from "adobe stone and clay." That ought to be "dried bricks and adobe clay" as stated in the "About the Hopis" at the end of the book.

We read that the best part of "multi-level living" is that Talasi can climb up and down a ladder. Sounds odd to me... let's think about a child in the midwest living in a two-story house. Is that child likely to say going up and down the stairs is the best thing about living in that multi-level home? I doubt it. Presenting that activity as a favorite thing for Talasi to do sounds very much like an outsider's imaginings of what life is like for a Hopi child. I suppose it is possible, but, not likely.

Page 10

The illustration shows Talasi and her grandmother, who sits in a rocking chair. The wall behind them has a six-paned glass window... which strikes me as an inconsistency. So does Talasi lying on the floor. It reminds me of a modern day house (again, in the Midwest) more than it does a Hopi home at one of the mesas. It also makes me wonder about the time period for this story.

On that page Talasi's grandmother tells her that she's going to move to a new home and that she'll go to a school to learn things that she (the grandmother) can no longer teach her. This foreshadows what is to come: Talasi's grandmother is going to die and upon her death, Talasi and her mom are going to move away to a city.

Page 14-15

On this page we have a double paged spread showing a city with tall buildings and bright lights. I wonder if it is Phoenix? And again I wonder about the time period for the story.

Page 16

Talasi goes to school but feels out of place. The text says that there are things to play with, but "no Katsina dolls to comfort her." Reading that, I hit the pause button. This, again, feels very much like an outsider voice. A "Katsina doll" isn't a plaything in the way that sentence suggests.

Page 18

Talasi brings a Katsina doll into the classroom. She wants to share it, and a story about it. I find that page especially troubling. It makes me wonder if Cromwell and Sterbini submitted this project to the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office. The acknowledgements page in the front of the book thanks Stewart B. Koyiyumptewa, the archivist at HCPO, for his "generous attention." His name there suggests that he endorsed Cromwell's book, but "generous attention" gives me pause. Given the care with which the HCPO protects Hopi culture from appropriation and misrepresentation, I doubt that HCPO approved what I see on page 18.

That said, the way that Talasi tells that story sounds--again--very much like an adult who is an outsider rather than how a Hopi child would speak.

***

I have too many concerns about the content of

Talasi, A Story of Tenderness and Love. If I hear from any of the people in the Acknowledgements, telling me that they do recommend it, I'll be back to say so.

A few days ago, I began to see Sujei Lugo's tweets about Kenneth Oppel's The Boundless. Intrigued, I got a copy from the library. Published in 2014 by Simon and Schuster, here's the synopsis:

The Boundless, the greatest train ever built, is on its maiden voyage across the country, and first-class passenger Will Everett is about to embark on the adventure of his life!

When Will ends up in possession of the key to a train car containing priceless treasures, he becomes the target of sinister figures from his past.

In order to survive, Will must join a traveling circus, enlisting the aid of Mr. Dorian, the ringmaster and leader of the troupe, and Maren, a girl his age who is an expert escape artist. With villains fast on their heels, can Will and Maren reach Will’s father and save The Boundless before someone winds up dead?

The country that train is crossing is Canada. In chapter one, Will ends up driving the final stake--a gold one--into the tracks, thereby completing the track in Craigellachie, presumably in 1885.

Let's step out of the book and look at a little bit of history.

The final stake connecting the eastern and western portions of the Canadian Pacific Railway was driven into a railroad tie on November 7, 1885, in Craigellachie. Here's a map showing where it is, in British Columbia:

And here's a map from the

website of the Canadian Museum of History, showing the route of the Canadian Pacific Railway:

Prior to the arrival of Europeans,

all that land belonged to Native Nations.

In the US, the last spike of the Transcontinental Railroad was driven into the track in 1869. Train stories about railroads are popular. I read them with a critical eye, wondering if the author is going to provide readers with any information about what the railroads meant for Native people. They were, in short, a key reason land was taken from Native Nations. It is with that knowledge that I read books about railroads and trains.

The Boundless came out in 2014--the same year that Brian Floca's

Locomotive won the Caldecott Medal.

The synopsis (above) for

The Boundless doesn't mention anything about Native people, but the story Oppel gives us has a lot of Native content. Let's start with Mr. Dorian. We first meet him at the end of chapter one, when he captures a sasquatch. The year for that chapter is 1885. Chapter two picks up three years later (1888).

The next time we see Mr. Dorian is in chapter three, where, in his role as circus master, he talks to passengers about the train, saying:

Cut from the wilderness, these tracks take us from sea to sea, through landscapes scarcely seen by civilized men.

I was intrigued about Oppel's treatment of sasquatch in chapter one. The sasquatch Mr. Dorian captured becomes part of the circus (though it doesn't do anything in performances) and is on the train three years later. I wasn't keen on seeing that one captured and put in a cage because the sasquatch is in Native stories of tribes in the northwest. And, I didn't like reading "scarcely seen by civilized men" either because it suggests that the peoples of the northwest tribal nations were uncivilized. Reading that line, of course, reminded me of the grueling discussions about "civilized" Indians in

The Hired Girl (those discussions took place on Heavy Medal and prompted me to do a stand-alone post,

A Native Perspective on The Hired Girl).

Those two concerns jumped to a whole new level when I got to chapter seven and learned that Mr. Dorian is Native. The bad guy, Mr. Brogan, is looking for Will (the protagonist). Brogan thinks Dorian is hiding him and threatens to throw Dorian and the entire circus off the train. Dorian doesn't think Brogan has the authority to do that, and Brogan says (p. 124):

"You'd be surprised. And I don't take my orders from circus folk--especially half-breeds like you."

We're not supposed to like Brogan, so having him use "half breed" is supposed to provide us with a cue that the use of the phrase is not ok. Even so, I cringed when I read it. Such words--even when uttered by despicable characters--sting.

That said, it was hard for me to think of a Native person capturing a sasquatch and keeping it in a cage (he also wants to catch a Wendigo, which is also a problem), and it is hard for me to think that a Native person would say that Native homelands were "scarcely seen by civilized men." Would he think that? Maybe it is a script he uses as a circus ringmaster? A performance designed to stir up the imagination of the (white) audience? If so, Oppel should have given readers a clue about those words, but he didn't.

Either way, portraying Native peoples and our nations as "primitive" or "uncivilized" fits with white supremacy and ideas that we didn't know how to use the land (as Europeans used land), and therefore the land itself could simply be claimed by European nations and Europeans who knew what to do with it (by their definition, of course).

Back to the story...

Mr. Dorian doesn't like being called a "half breed" and calmly replies that he prefers the term Métis. Will overhears their conversation and thinks:

Having grown up in Winnipeg, Will is familiar with the Métis--the offspring of French settlers and Cree Indians--and the insults they endured, especially after their failed uprising.

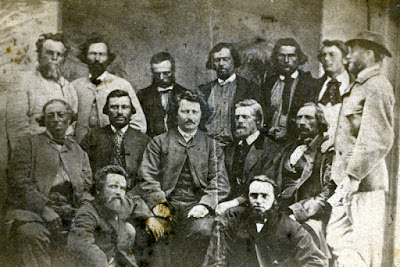

Is what Will says accurate? Partially, but there's a lot more to it than that. And, is the "failed uprising" about Louis Riel? And... why use "uprising" to refer to that period of Métis activism? What image of comes to mind with the word "uprising"? Is it one like this? This is Riel and men who were, in the late 1860s/early 1870s, part of a provisional government he formed:

|

| Source: http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/events/rielcouncillors.shtml |

Other words in what Will says about Métis are odd, too. Uprising is one, but so is "offspring." Technically, it does mean children, but why not have Will use children, or kids?

Skipping ahead now, to page 145 (chapter 8) where Maren (she's a main character, too) is showing Will around the train car where the circus performers practice. Specifically, they're looking at the trapeze artists (the train is huge):

Both men are lean and muscular. Their heads are bald except for a tuft of long hair at the back, which is gathered into three braids.

Will asks Maren if they're Mohawk. She says yes, and that they're fearless, that heights mean nothing to them. I don't know about those three braids, but Oppel is definitely using what he knows about

Mohawk steelworkers. Fearless, though? Nope.

In chapter nine, Will is headed up to the "colonist" cars which are overcrowded. The person who takes them through the cars tells them that (p. 177):

"These people are fortunate to get passage on the Boundless at all," Drurie says with a sniff. "They're the poorest of the poor, and they've washed up on the shores of our country to claim our land."

They're German, French, and Italian. Mr. Dorian replies to Drurie (he's white):

"My mother's people are Cree Indian. Perhaps it's people like you who have washed up on our shores. A stimulating thought, don't you think?"

Drurie ignores him, but let's pause. Remember what I pointed out about Dorian's use of "civilized" in chapter three? Dorian is expressing a very political point here, but didn't do so earlier. That is an inconsistency in his characterization. Of course, I like the point he makes here. That line gets at current political discussions about immigration.

There's more I could note (like the

brownface Sujei Lugo pointed out), but I'll end with a brief discussion of the buffalo hunting scene. It takes place in chapter 12. The train has a shooting car, in which passengers can pay to use a rifle (provided by a steward) to shoot at wildlife they pass. Just at the moment that Will and Maren are in the shooting car, a herd of buffalo moves over a hill and toward the train. Passengers start shooting at them. Will thinks it unsportsmanlike. He's right, of course, but that activity was common on trains during that time. Mr. Dorian says (p. 251):

"This is how you exterminate a people," the ringmaster says bitterly, "You kill all their food."

Then, passengers see Indians riding behind the herd, driving the herd away from the train. Some have rifles and some have bows. The steward tries to get people to leave the car, but they don't want to. One man shouts (p. 252):

"Damn redskins! They're steering them away from us."

Angry, that man then takes aim at one of the Indians on horseback. Dorian grabs the rifle and tells the angry man that the Indians need those buffalo for food and hides. The angry man says he's helping them by shooting the buffalo. Dorian points out that the man was shooting at the Indians, and the man says:

"What's one less Indian?"

He's killed an instant later, by an arrow, and Dorian murmurs "one less white man." The steward manages to get everyone inside, where Will hears a man call out how they "showed those redskins."

Earlier, I talked about a bad-guy using "half-breed." Here, the people using "redskins" are not likable either, and that's supposed to help readers know that what those men are doing is not ok. I think it does that, but as before, such language stings. In this case, it is even worse.

I don't like

The Boundless. Like many of Oppel's books, it has sold well. It got starred reviews from the major children's literature journals--stars, in my view, it does not merit. Given its inconsistencies and use of troubling ideas and phrases, I cannot recommend Oppel's

The Boundless.

Today's post is one that walks you (readers of AICL) through my evaluation process (what I do) when I pick up a book that is put forth as a Native "legend."

The focus of today's post?

The Legend of the Beaver's Tail "as told by" Stephanie Shaw, with illustrations by Gijsbert van Frankenhuyzen. It was published in 2015 by Sleeping Bear Press. As the note above the cover indicates, I do not recommend it.

First commentSee the word "legend" in the title? The word "legend" is often used to describe Native stories. It is one of those catch-all words that should be used in a universal way (applied to all peoples stories) but isn't.

Let's pause here. I'd like you to think about all the Bible legends you've read in the children's picture book format. Can't think of one? You're not alone. Most of the stories from the bible are not treated as "legends."

If you look up the definition of legend, you'll find the word is used to describe an old story. You're not likely to find "sacred" as part of that definition. Bible stories are old, but they don't get categorized as legends because they're sacred to the people who tell them.

Native stories are as sacred to Native people as Christian stories are to Christians. I view the selective use of "legend" as the outcome of a long history of Christians putting Native people forward as "other" to Christianity, with Christianity as THE religion that matters. Those "other" religions aren't religions at all in that Christian point of view. Instead, they're less-than, primitive, superstitious, quaint... You get the point.

So--when I see "legend" used to describe a Native story, I wonder if the person telling that story (or retelling it) is aware of the bias that drives that person to use the word "legend."

Second commentWho is this "legend" supposed to be about? Who tells it? The front cover doesn't tell us. Neither does the back cover. On the copyright page, we read this summary:

"Vain Beaver is inordinately proud of his silky tail, to the point where he alienates his fellow woodland creatures with his boasting. When it is flattened in an accident (of his own making), he learns to value its new shape and seeks to make amends with his friends. Based on an Ojibwe legend." --Provided by publisher.

Let's consider that last line: "Based on an Ojibwe legend." A lot of those "based on" books for children--the ones about Native people--draw from more than one Native nation's stories. A good example are the ones by Paul Owen Lewis. He used stories from more than one nation to come up with

Frog Girl and

Storm Boy. On his website, you can read that

"Storm Boy follows the rich mythic traditions of the Haida, Tlingit, and other Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast..."

Those are distinct nations with their own stories. If you look at his books, they look like they are Native stories, but are they? If they combine aspects of more than one tribal nation? My answer: No. Let's look just at two that Lewis listed: the Haida and the Tlingit. In the US (in Alaska) there is the

Central Council of the Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes. At their website, you read that they're "two separate and distinct people" and there's also the

Yakutat Tlingit Tribe (their direct website is down), also in Alaska. And in Canada, there's the

Haida Nation.

The difference in the books Lewis does and Shaw's story is that he names several nations and she names one (Ojibwe). Does that make a difference? Maybe... let's keep on with this evaluation process.

Third commentWho is Stephanie Shaw? Is she Native? With the "as told by" on the cover, do we have a story being told by a tribal member? At

her website, I see that she lives in Oregon, but there is no mention of any Native heritage or working with Native populations or attending Native events... Nothing. None of her other books are about Native people. I assume then, that she is not Native. I wonder what prompted her to do this book?

As some of you know, I do not insist that a writer be Native in order to write Native stories. As I discussed elsewhere, I prefer Native writers, but I also think that a person who is not Native can write a Native story, and do it well--if they are careful with their research. Wondering about Shaw's research leads to my fourth comment.

Fourth CommentWhat does Shaw say about her sources? Have you read Betsy Hearne's article,

Cite the Source, Reducing Cultural Chaos in Picture Books, published in

School Library Journal in 1993? An excellent article, it was a call for better source notes. It includes a "source note countdown" that can help reviewers evaluate a source note. The worst kind of note is nonexistent. It is #5 in Hearne's countdown. The best kind is #1, "the model source note."

So... let's look at the notes in Shaw's book.

There is a page in the back of the book titled "The Ojibwe People and Legends." Beneath it is a bibliography. Let's start with the note about Ojibwe people. The first paragraph tells us about various spellings of Ojibwe. The second paragraph is this:

Legends are an important part of Ojibwe culture. They are stories passed from one generation to the next, usually through oral storytelling. They are sometimes meant just for fun and entertainment. Other times they are used to teach a lesson about behavior. In a legend such as The Legend of the Beaver's Tail, we learn about how pride and boastful behavior can drive friends away. We also learn how sharing among friends can build a community.

It starts with that word (legend). I've already said a lot about it, but I invite you to read that paragraph, with Christianity in mind. Some of what we read in the Bible are stories about behavior. Can you think of a picture book that presents one of those stories as a legend?

Now let's look at the bibliography.

It consists of eleven items. Seven of them are about beavers. I assume Shaw and perhaps her illustrator, Gijsbert van Frankenhuyzen, used those items for information about beavers. The other four (two books and two websites), I assume, are sources for what she provides about Ojibwe people. Let's take a look.

She lists Joseph Bruchac and Michael J. Caduto's

Native American Stories published in 1991 by Fulcrum. It doesn't have an Ojibwe story about beaver. Shaw also lists Michael G. Johnson and Richard Hook's

Encyclopedia of Native Tribes of North America published in 2007 by Firefly Books. I don't know that book, but from what I can see, it doesn't have a story about beaver in it.

She lists First People--the Legends. "How the Beaver Got His Tail." Accessed December 11, 2012, at www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Legends/HowTheBeaverGotHisTail-Ojibwa.html. I've been to that site before--and cringed. You're invited to "Click on my little kachina friends" to see what has recently been added to the site. Yikes! "Little kachina friends" is way over the line. Think of it like this: "Click on my little Catholic saint friends below..." instead. Feel uneasy? That's how I feel as I read "my little kachina friends." I wonder who wrote "my little kachina friends"? We don't know who owns, manages, or writes the content of that "First People" site. They use the word "we" a lot but who is "we" anyway?! They've got a section called "our favorite artists that paint Native Americans" --- but the ones they list aren't Native artists. Unless you're doing a study of appropriation, I think this site is one to stay away from. She also lists Native Languages of the Americas, a site maintained by Orrin Lewis and Laura Redish. Though we do know who runs that site, its content is unreliable. Like the First People site, I've looked it over before and found it lacking. According to the site, Lewis is Cherokee and not as involved with the content as he once was. Redish is not Native. I don't see any Ojibwe stories there, either.

Maybe the bibliography isn't one that Shaw developed. Maybe that page was put together by someone at the publishing house. Either way, it is troubling to see what gets listed in a book, as information to pass along to children.

Applying Hearne's countdown, I think Shaw's notes are at the not-good end of the scale:

4. The background-as-source-note. Better than nothing but still close to useless, this note gives some general information on the culture from which a picture-book folktale is drawn. It's important to know about traditions, but that's a background note, not a source note. In some ways, it's worse than no note at all because it's deceptive. It looks like a source note, so we let it slide by. Some notes (variation 4A) even manage to tell the history of a tale but avoid citing the book or books from which the tale was adapted. Others (variation 4B) declare that the picture-book author heard many stories from his/her grandmother/grandfather, but beg the question of where he/she heard/read this particular story. Implication is a sneaky and highly suspicious maneuver. Source notes, once and for all, tell sources. How can we know what's been adapted without being able to track down the author/artist's source?

Fifth commentI imagine you're wondering, "well, what about the story itself?" The answer? It doesn't matter. Shaw may have told what some think is a terrific story, but without the information to support that story, it doesn't matter. It is introducing or affirming the chaos Hearne wrote about in her article.

Conclusion: Not recommendedIf you care about providing young people with authentic or accurate stories about Native people, this one won't work.

I find Danielle Daniel's Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox unsettling.

In a 2013 article in The Sudbury Star, I read that she is Métis, but that she wasn't raised knowing anything about her Métis heritage. She didn't want her son to grow up without knowing something about that heritage, so she wrote and illustrated Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox as a self-published book that is out this year in hardcover from Groundwood Books (House of Anansi Press). Here's an excerpt from the article (from October 28):

For first-time author and local artist Danielle Daniel, her new children's book Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox was a way to help her 10-year-old son connect to his Metis roots. Daniel, who stopped working as a teacher full-time last year so she could pursue her art, said she was not encouraged to learn about her Metis heritage when she was growing up. "I didn't want that to be the same for my son," she said. "I wanted him to feel proud about it and to celebrate it. "She dedicated the book - which explores 12 different totem animals -to her son and all the Metis and Aboriginal children who never had a chance to know the totem animals because of the residential schools.

The article suggests that residential schools are the reason she didn't know her culture and that this book can help her son and others, but I'm not sure it can. Daniel says she started dreaming about bears and so feels that a bear is her totem animal. That lines up with what I see in new age writings, and not with what I understand about the ways that Anishinaabe people view any of this.

In the Author's Note, Daniel writes:

The word totem, or doodem in Anishinaabe, means clan.

From my reading of key writings, and conversations with Ojibwe friends, I know that clans hold tremendous significance.

That significance is lost in Daniel's treatment of them in the book. The words on each page start with "Sometimes I feel like..." There are 12 different pages for 12 different "totem animals." On each page, is an illustration of a child whose head/face are modified to look like the animal. This is done with a paper mask tied onto the child's head, or a headpiece that fits entirely over the child's head, or with some aspect of the animal being shown as though the child were part it and part human (the page about a beaver has a child with beaver ears, nose, and teeth).

That treatment of the clans trivializes the importance of the clan system. Someone who lives with that system doesn't shift from one to another in the way Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox suggests. Daniel's book feels more like playing at being Indian than something that her son or any child can actually learn from.

That's one part of why I'm unsettled but the other is because I have so much empathy for Native people who lost culture because of the boarding schools in the US (and the residential schools in Canada). Those "educational" systems were--and are--devastating to Native people and our cultures and respective nations. I support efforts to learn, but it must come by way of being with the people one identifies with. Artistic efforts to reconnect will fail without the teachings that come from being with the people you're trying to connect with.

Not recommended.

E. K. Johnson's Prairie Fire is the sequel to The Story of Owen. Both are works of fantasy for young adults that are also described as alternative histories. Here's the synopsis for The Story of Owen:

"Listen! For I sing of Owen Thorskard: valiant of heart, hopeless at algebra, last in a long line of legendary dragon slayers. Though he had few years and was not built for football, he stood between the town of Trondheim and creatures that threatened its survival. There have always been dragons. As far back as history is told, men and women have fought them, loyally defending their villages. Dragon slaying was a proud tradition. But dragons and humans have one thing in common: an insatiable appetite for fossil fuels. From the moment Henry Ford hired his first dragon slayer, no small town was safe. Dragon slayers flocked to cities, leaving more remote areas unprotected. Such was Trondheim's fate until Owen Thorskard arrived. At sixteen, with dragons advancing and his grades plummeting, Owen faced impossible odds—armed only with a sword, his legacy, and the classmate who agreed to be his bard.

Listen! I am Siobhan McQuaid. I alone know the story of Owen, the story that changes everything. Listen!"

Henry Ford hiring dragon slayers! Cool? I don't know because I didn't read

The Story of Owen. I did, however, read the sequel,

Prairie Fire. Here's the synopsis for it:

Every dragon slayer owes the Oil Watch a period of service, and young Owen was no exception. What made him different was that he did not enlist alone. His two closest friends stood with him shoulder to shoulder. Steeled by success and hope, the three were confident in their plan. But the arc of history is long and hardened by dragon fire. Try as they might, Owen and his friends could not twist it to their will. Not all the way. Not all together. The sequel to the critically acclaimed The Story of Owen.

Prairie Fire is primarily about Owen and Siobhan (who tells the story). Their assignment as dragon slayers is to guard Fort Calgary. As I started to read, I saw a lot of place names specific to First Nations but... no people who are First Nations (that comes later).

Early in the book, there's a reference to Manitoulin, a place that (I think) was destroyed in

The Story of Owen. I read "Manitoulin" and right away wondered if that is a Native place. The answer? Yes. According to the Wikwemikong

website, Manitoulin is home to one of the ten largest First Nations communities in Canada. I understand--of course--that in stories like

Prairie Fire, writers can write what they wish--including wiping out existing places--but when the writer is not Native, and one of the places being wiped out is Native, it too closely parallels recent and ongoing displacements and violence done to Indigenous peoples. As such, I object.

We learn a bit more about Manitoulin when we get to the chapter, The Story of Manitoulin(ish) (p. 55):

Once upon a time, there was a beautiful island where three Great Lakes met. Named for a god, it could well have been the home of one: rolling green hills and big enough that it was dotted by small blue lakes of its own. It was the biggest freshwater island in the world, and Canada was proud to call it ours.

Named for a god? I don't think so. From what I'm learning, it means something like 'home of the ancestors.' I also wondered, as I read that line, who named it Manitoulin? Canadians? Canadians who are "proud to call it ours"? Another big pause for me. I doubt that First Nations people reading

Prairie Fire would be ok with that line.

In

Prairie Fire, we learn that the island, situated between the US and Canada, is inhabitable due to American capitalism (p. 55):

Two whole generations of Canadians grew up, never having set foot on that pristine sand, never staying in those quaint hotels, and never learning to swim in those sheltered bays, but always there was hope that we would someday return.

Hmmm. That sounds to me like White people who are lamenting loss of pristine sand and quaint hotels. Again, no Native people. Kind of shouts privilege, to me. Another place named is Chilliwack, home to the Sto Lo people, but no Sto Lo people are in

Prairie Fire. The chapter, Totem Poles, is unsettling, too. These poles are at Fort Calgary. Siobhan and Owen get there, via train. As they traveled, Siobhan worried that they'd be attacked by dragons (p. 69):

There are any number of American movies about dragon slayers fighting dragons from the tops of trains, but I was quite happy not to be reenacting one. We made it all the way to Manitoba before we even saw a dragon out the window, and it was far enough away that we didn’t have to worry about it.

That reminded me of westerns in which Indians are attacking the trains, and while I don't think Johnston intended us to equate dragons with Indians, I kind of can't help but make that connection when I read that passage. Anyway, as the train nears Fort Calgary, they see a row of metal teeth that stretch up into the air (p. 71):

The metal teeth were the tops of stylized totem poles, taller than the California Redwoods on which they were modeled, and thrusting jagged steel into the bright prairie sunset. Though most of the poles were around the wall of the fort, they were also scattered throughout the city itself, to prevent the dragons from dive-bombing any of the buildings.

One of the dragon slayers thinks they are beautiful, but another says (p. 71):

“They’re probably covered with bird crap up close,” Parker pointed out.

Totem poles hold deep significance to the tribes who create them. I haven't studied Parker as a character, and it may be that he's an unpleasant sort who we readers are expected to dislike, but still... Was that "bird crap" line necessary? And why are totem poles cast as tools of defense in the first place? It reminds me of the United States Armed Services use of names of Native Nations and imagery for weapons of war (examples include the Apache attack helicopter and the tomahawk cruise missile). They--like mascot names--are supposedly conveying some sort of honor, but with victory over a foe the goal, are these honorable things to do?

The book goes on and on like that...

In Disposable Civilians, we read about a dragon called the Athabascan Longtail.

Athabascan's are Native, too. And then there's the chapter called The Story of the Dragon Chinook. For those who don't know, Chinook is also the name of a First Nation. In

Prairie Fire, the Chinook dragons are especially vicious. Their attacks are preceded by smoke. There's more railroad trains in this part of the story. To get railroad tracks laid, the government brings Chinese workers to Canada, "paying them just enough that they might forget about the dragons in the sky" (p. 124). And yes, those Chinese workers are amongst those disposable civilians.

In the Haida Welcome chapter (Owen and Siobhan are visiting Port Edward, on the coast), we get to know a character named Peter and his family. They are Haida. They play drums made of dragon's hearts. There's a stage where they dance. The stage has a row of waist high totem poles (p. 221):

These were wooden poles, traditional and fierce looking, each with painted white teeth inside a grinning mouth and an odd crest upon each head.

Owen, Siobhan, and the others gathered there watch the dancers on stage move in ways that suggest they're in a canoe. Siobhan remembers that the Haida are a sea-going nation. The person in front is their dragon slayer. She throws a rope with a large ring on its end to a dragon. On the fourth throw she catches it, the song and dance change, and the dragon is brought to the totem poles where it lies down, defeated. Owen wonders aloud if the dragon had drowned, and Peter laughs, telling him (p. 222):

“No,” Peter said. “The orcas took care of it.” “The whales?” Owen said. “They’re not called Slayer Whales for nothing,” Peter reminded him.

That part of the story makes me uneasy. What Johnston has done is create what she presents as a Native ceremony or dance. It reminds me of what Rosanne Parry did in

Written In Stone. After that dance part, I quit reading

Prairie Fire. Though I can see why it appeals to fans of stories like this, the erasure of Native peoples, the weaponizing of Native artifacts, and the creation of Native story are serious problems. I cannot recommend

Prairie Fire.

I've never used "absolutely disgusted" in a title before today. There are vile things in the world. Some of them are subtly vile, which makes them dangerous because you aren't aware of what is going into your head and heart.

Some things, like Catherynne M. Valente's Six-Gun Snow White are gratuitously vile. As a Native woman, it is very hard to read it in light of my knowledge of the violence inflicted on Native girls and women--today. Here's the synopsis:

A plain-spoken, appealing narrator relates the history of her parents--a Nevada silver baron who forced the Crow people to give up one of their most beautiful daughters, Gun That Sings, in marriage to him. With her mother s death in childbirth, so begins a heroine s tale equal parts heartbreak and strength. This girl has been born into a world with no place for a half-native, half-white child. After being hidden for years, a very wicked stepmother finally gifts her with the name Snow White, referring to the pale skin she will never have. Filled with fascinating glimpses through the fabled looking glass and a close-up look at hard living in the gritty gun-slinging West, readers will be enchanted by this story at once familiar and entirely new.

There is no redeeming Valente's words. There is nothing she could write, as the book proceeds, that will undo what she says in the first half. I quit.

I don't think this is meant to be a young adult novel but I've seen a colleague in children's literature describe it as "fantastic" which is why I decided I ought to see what it is about. As the synopsis indicates, it is a retelling of Snow White. It was first published in 2013 by Subterranean Press as a signed limited edition (1000 signed and numbered hardcover copies), but is being republished in 2015. This time around, the publisher is Saga Press.

Obviously, I don't recommend it. I've never read anything Valente wrote before. I asked, online, if this is typical of her work, and the reply so far is no. So why did she do this? Why would anyone do this?

Six Gun Snow White is not fantastic. It is not brilliant. It is grotesque. It is so disgusting that I will not sully my blog with actual quotes from the book.

- Valente uses animal-like depictions to describe the main character's genitals. Yes, you read that right, her genitals. Animal-like characteristics are often used in children's literature but none, that I recall, that are anything like these. In children's books, you'll find things like Indians who "gnaw" on bones or have "steely patience, like a wolf waiting." Such descriptions dehumanize us.