new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: OMO, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 35 of 35

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: OMO in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 2/26/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Anton Webern,

diatonic,

Meg Wilhoite,

musical texture,

Petrassi,

petrassi…”,

petrassi’s,

accented,

Music,

avant-garde,

gmo,

oxford music online,

OMO,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

consonance,

Online Products,

Grove Music Online,

avant-garde music,

Elliott Carter,

Matthew Hough,

Add a tag

By Meg Wilhoite

In December I blogged about composers whose works challenge listeners to reconsider which combinations of sounds qualify as music and which do not. Interestingly, The Atlantic recently ran an article relating the details of a study that tested how much of our perception of what is “music” – in this case, pleasant, consonant music – is learned (and thus not innate). For me (and perhaps for you) there is nothing too surprising about this — there are far too many types of music in this world of ours for the perception of consonance (or, what is pleasing in music) to be innate — but it serves as a fine backdrop for what I’m about to write.

For if a penchant for consonance is not innate, then our individual definitions of music have the capability for modification and expansion. I remember the first time I heard music that challenged my ears (a piece by Anton Webern); at first I recoiled, but after a few days, when I realized the experience was sticking with me, I decided to take a second listen. Over time, I grew to appreciate and enjoy the sound of it, partly because I began to embrace the idea that music can consist of music that isn’t diatonic, and also because I began to understand Webern’s compositional methods and historical context.

Part of this new appreciation was learning more about the music, and, as a music-theorist-by-night, I thought it might be fun to take a closer analytical look at compositions written by two of the composers mentioned in my last post, just to take a closer look at what makes them tick.

Let’s start with Elliott Carter’s piece 90+ for solo piano (you can watch an excellent performance by Illya Filshtinskiy on YouTube).

For me, the salient feature of this piece is its texture, of which I hear two types. In the first, chords sustain while single notes, some of them accented (marked with the “greater than” sign in the score below), are struck at irregular intervals, as in the first six measures of the piece.

Excerpts from 90+ used with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

In the second, the sustained chords are absent; instead single notes (for the most part), sometimes accented, skitter about all over the keyboard.

Excerpts from 90+ used with permission from Boosey & Hawkes

So much for my first-glance hearing, what does the composer have to say?

“90+ for piano is built around ninety short, accented notes…against these the context changes character…it was composed in March of 1994 to celebrate the ninetieth birthday of my dear and much admired friend, Goffredo Petrassi…”

And thus you can see, on the first page of the score near the top of this post, little numbers in parentheses — which I’ve circled — that begin counting out Petrassi’s ninety years (the little numbers only occur on the first and last pages, the last page beginning with number 85). This knowledge changes my hearing of the piece: Carter is expressing through music ninety years of a man’s life. Though his pitch and rhythmic selections still remain arcane to me at this point, the overall gesture of the piece takes on new meaning.

My second analysis involves a new piece by composer Matthew Hough (one of NPR’s “100 composers under 40”) called “Remembered States” (2011), written for nine performers. Even more so than the Carter piece, texture is by far the most prominent feature of this work, mainly due to the unconventional use of the instruments.

Excerpt from Remembered States used with permission from Hough House (ASCAP)

The piece features tactile clacking, gritty overtones, and various shimmering sounds. In this excerpt, the voice murmurs unintelligible words while the flute and trumpet follow suit “as if speaking”; the composer has called this technique “ghost playing”, a sort of shadow of the music. The clicking of the sax keys is audible, as well as the bassoon’s overtones and the coordinated chords in the piano and electric guitar. High above it all is a dry, stratospheric sustained violin note.

For me the experience is that of blurriness or semi-consciousness, where the overall effect is a sort of pixilated background out of which certain sounds stand out in stark contrast (particularly the bassoon overtones and the violin note). According to the composer, the title of the piece is meant to convey a type of remembering, where details sometimes dissipate in the background, while others jump dramatically to the fore.

While pieces like these can be challenging for some listeners, I think it is unfair to assume, as some have done, that the composers are unconcerned with connecting with their audience. I believe for many avant-garde composers today it’s more of an unconcern about conforming to perceived norms. The audience is welcome to come along for the ride if they so wish.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Follow-up: Is it music? A closer look appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/31/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Memory,

performance,

gmo,

grove,

oxford music online,

memorize,

memorization,

OMO,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Grove Music Online,

Meghann Wilhoite,

megwilhoite,

wilhoite,

at grove,

Anthony Tommasini,

Clara Schumann,

Franz Liszt,

Stephen Hough,

tommasini,

craighead,

Music,

Add a tag

By Meghann Wilhoite

I have a confession to make: I have a terrible memory. Well, for some things, anyway. I can name at least three movies and TV shows that Mary McDonnell has been in off the top of my head (Evidence of Blood, Donnie Darko, Battlestar Galactica), and rattle off the names of the seven Harry Potter books, but you take away that Beethoven piano score that I’ve been playing from since I was 14, and my fingers freeze on the keyboard. My inability to memorize music was in fact the reason I gave up on my dream of being a concert pianist—though, in retrospect, this was probably the right move for me given how lonely I would get during hours-long practice sessions…

I’ve since come to terms with my memory “deficiency,” but a recent New York Times article by Anthony Tommasini on the hegemonic influence of memorization in certain classical performing traditions brought some old feelings to the fore. Why did I have to memorize the music I was performing, especially considering how gifted I was at reading music notation (if I may say so myself)?

As Tommasini points out (citing this article by Stephen Hough), the tradition of performing from memory as a solo instrumentalist is a relatively young one, introduced by virtuosi like Franz Liszt and Clara Schumann in the 1800s. Before that, it was considered a bit gauche to play from memory, as the assumption was that if you were playing without a score in front of you, you were improvising an original piece.

I should be clear at this point that I have nothing against musicians performing from memory. Indeed some performers have the opposite problem to mine: the sight of music notation during performance is a stressor, not a helper. Nonetheless, I do feel that the stronghold that memorization has on classical soloist performance culture needs to be slackened.

One memory in particular related to memorization haunts me still. After sweating through a Bach organ trio sonata during a master class in the early 00s, the dear late David Craighead gave me some gentle praise and encouraged me to memorize the piece. “Make it your own” were his words. I was devastated. How on earth was I going to memorize such a complex piece?

In spite of my devastated feelings, I heard a nagging voice in the back of my mind telling me Dr. Craighead was right. If only I could memorize the piece, it truly would be my own. I’d heard before from other teachers that the best way to completely “ingest” a piece was to practice it until you didn’t need the score anymore. The lone recital I gave from memory during my college years was admittedly an exhilarating experience; I definitely felt that I had a type of ownership over the pieces, even if I was in constant terror of having a memory lapse. In hindsight, though, I believe my sense of ownership was not a result of score-freedom, but from the hours and hours (and hours) I spent in the practice room preparing for the recital.

Whether or not you are moved by my struggles (being a little facetious here), I think that, in 2013, it is time for us to acknowledge the multiplicity of talents a classical soloist may possess, and stop trying to squeeze everyone into the same box.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post To memorize or not to memorize appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/25/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

gmo,

oxford music online,

OMO,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Stanley Sadie,

Grove Music Online,

Anna-Lise Santella,

Dag Henrik Esrum-Hellerup,

Grove Music Spoof Article Contest,

Guglielmo Baldini,

Mountweazel,

hellerup,

Add a tag

By Anna-Lise Santella

On my desk sits an enormous, overstuffed black binder labeled in large block letters “BIBLE”. This is the Grove Music style sheet that was handed to me on my first day on the job, the same one — with a few more recent amendments — assembled by Stanley Sadie and his editorial staff for the first edition of the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians published in 1980. The Bible is daunting, bigger than our house style sheet by dozens of pages, and it carries with it a legacy that has defined my academic field. But in my first year and half as editor of Grove Music Online, I’ve learned to love it — with all its quirks, there is virtually no organizational, grammatical, or structural quandary it does not address. It’s very reassuring. If only the rest of my life had such a tool.

A style as specific as Grove’s lends itself well to parody, so it’s perhaps no surprise that in the first edition of New Grove, a couple of well-honed articles slipped by the sharp eyes of editor in chief Stanley Sadie : an article attributed to Robert Layton on the spurious Danish composer Dag Henrik Esrum-Hellerup, and an equally fictitious 16th-century Italian composer, Guglielmo Baldini. The Baldini article was actually based on a character created nearly a century earlier by German musicologist Hugo Riemann in his own music dictionary. Both articles conformed so well to Grove style that they went undetected until after the books appeared in print, at which point a furious Sadie removed them before New Grove went into a second printing.

A style as specific as Grove’s lends itself well to parody, so it’s perhaps no surprise that in the first edition of New Grove, a couple of well-honed articles slipped by the sharp eyes of editor in chief Stanley Sadie : an article attributed to Robert Layton on the spurious Danish composer Dag Henrik Esrum-Hellerup, and an equally fictitious 16th-century Italian composer, Guglielmo Baldini. The Baldini article was actually based on a character created nearly a century earlier by German musicologist Hugo Riemann in his own music dictionary. Both articles conformed so well to Grove style that they went undetected until after the books appeared in print, at which point a furious Sadie removed them before New Grove went into a second printing.

There is a long tradition of spoof articles appearing in encyclopedias and dictionaries. There’s even a special term for such an entry: Mountweazel, named after a spoof article that appeared in the 1975 edition of the New Columbia Encyclopedia. In a 2005 article in the New Yorker, one of NCE’s editors, Richard Steins, claimed, “It was an old tradition to put in a fake entry to protect your copyright.” The idea was that if someone copied your dictionary, you could prove it by pointing to the fake. Perhaps this is true, but somehow I suspect that the tradition owes at least as much to the suppressed wit of authors and editors toiling on a genre of publication that can, at times, feel over-regulated. The fictional Lillian Mountweazel, for instance, was reportedly born in “Bangs, Ohio,” worked as a photographer specializing in images of mailboxes, and met an untimely death by explosion while on assignment with Combustibles magazine. Clearly a Mountweazel is no mere copyright-protection device.

Despite his elimination of Grove’s Mountweazels, Stanley Sadie did have a sense of humor. A year after the publication of New Grove 1, a collection of spoof articles appeared in the journal Musical Times (also edited by Sadie) laid out in perfect imitation of Grove’s style and format and, according to a brief preface, “obtained for MT from the Grove offices through an operation comparable in its scope, its daring and (we hope readers will agree) its success with the more famous Watergate.” These articles included.

Brown, ‘Mother’ (Mary)

Ear-flute

Hameln

Khan’t, Genghis (Tamburlaine)

Stainglit (Nevers), Sait d’Ail

Toblerone

Verdi, Lasagne

It wasn’t Sadie’s lack of humor, but his dedication to Grove’s accuracy and clarity that motivated him to eliminate the spurious works. He was, perhaps, prescient about the rapidity of the spread of the printed word in the internet age. Once you publish something, you never really know where it goes. Case in point: Both Eklund-Hellerup and Guglielmo Baldini appear in Germany’s answer to Grove, Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Only Eklund-Hellerup is marked as a spoof.

In honor of the co-existent traditions of accuracy and humor in the history of Grove Music, the Grove Music editorial staff would like to encourage the proliferation, not of Mountweazels per se, but of the dedication to the stylistic standards that support the content written by thousands of scholars over more than a hundred years. It is therefore my pleasure to announce the first (annual?) Grove Music Spoof Article Contest. Do you have what it takes to write a convincing Grove Music Mountweazel? Then read on.

Submission Guidelines:

- Articles must be no longer than 300 words, including any bibliography or works lists you might choose to include. There is no minimum length. Entries that do not adhere to the length limit will be folded, spindled, mutilated, and rejected.

- Articles will be judged by a mix of staff and outside judges including Grove Music’s Editor in Chief Deane Root, Editor Anna-Lise Santella, and a guest editor to be named later.

- Judges will consider the following criteria:

- Does the article adhere to Grove style?

- Is it entertaining?

- Could it pass for a genuine Grove article (maybe if you forgot your glasses and you were squinting at it)?

- Submissions must be sent by email sent to editor[at]grovemusic[dot]com as follows:

- Subject must read “Grove Music fake article contest-title” (e.g., Grove Music fake article contest-Ear flute)

- Body of the email must include the title of the article and your full name and contact information (street address, email, phone)

- The article must be included in an attached document. It must not include your name. This is to facilitate blind judging. Use your article’s title as the document name (if your article includes punctuation that can’t be in a document title, replace the punctuation with a space). Once we receive your submission, we will send you a release form that will allow us to publish your article. You will need to sign it and return it before you can be entered into the contest.

- You may send as many as three articles, but please send each submission separately. No more than three entries will be accepted from a single author.

- All submissions must be received by midnight on 15 February 2013. Manuscripts received after that time will not be considered.

- The winning article(s) will be announced on 1 April 2013 on the OUPblog

- The winner will receive $100 in OUP books and a year’s subscription to Grove Music Online. The winning entry will be published on the OUPblog and also at Oxford Music Online where they will appear NOT as part of the dictionary, which we strive to keep accurate, but alongside the historic spoof articles on a special page.

- Fine print: We reserve the right not to award a prize if we feel the submissions do not meet our criteria.

Let the games begin.

Anna-Lise Santella is the Editor of Grove Music/Oxford Music Online. She is currently waging a one-woman campaign to have the word “Mountweazel” added to the OED. When she’s not reading Grove articles, or writing about women’s orchestras — her article, “Modeling Music: Early Organizational Structures of American Women’s Orchestras” was recently published in American Orchestras in the Nineteenth Century, edited by John Spitzer (U. Chicago, 2012) — you can find her on twitter as @annalisep.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A Grove Music Mountweazel appeared first on OUPblog.

By: JonathanK,

on 1/17/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

Oxford,

children's music,

opera,

cookie monster,

coloratura,

Sesame Street,

gmo,

grove,

oxford music online,

classical music,

OMO,

itzhak,

perlman,

marilyn,

barbour,

horne,

horne’s,

*Featured,

sesame,

Arts & Leisure,

Grove Music,

Grove Music Online,

Jessica Barbour,

C is for Cookie,

Marilyn Horne,

Add a tag

Jessica Barbour

Marilyn Horne, world-renowned opera singer and recitalist, celebrated her 84th birthday on Wednesday. To acknowledge her work, not only as one of the finest singers in the world but as a mentor for young artists, I give you one of my favorite performances of hers:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sesame Street has always been a powerful advocate for utilizing music in teaching. “C is for Cookie,” a number that really drives its message home, maintains its cultural relevance today despite being first performed by Cookie Monster more than 40 years ago. Ms. Horne’s version appeared about 20 years after the original, and is an excellent re-imagining of a classic (with great attention to detail—note the cookies sewn into her Aida regalia and covering the pyramids).

Horne’s performance shows kids that even a musician of the highest caliber can 1) be silly and 2) also like cookies—that is, it portrays her as a person with something in common with a young, broad audience. This is something that members of the classical music community often have a difficult time accomplishing; Horne achieves it here in less than three minutes.

Fortunately, many professional classical musicians have embraced this strategy. Representatives of the opera world (which is not known for being particularly self-aware) have had a particularly strong presence on Sesame Street, with past episodes featuring Plácido Domingo (singing with his counterpart, Placido Flamingo), Samuel Ramey (extolling the virtues of the letter “L”), Denyce Graves (explaining operatic excess to Elmo), and Renée Fleming (counting to five, “Caro nome” style).

Sesame Street produced these segments not only to expose children to distinguished music-making, but to teach them about matters like counting, spelling, working together, and respecting one another. This final clip features Itzhak Perlman, one of the world’s great violin soloists, who was left permanently disabled after having polio as a child. To demonstrate ability and disability more gracefully than this would be, I think, impossible:

Click here to view the embedded video.

American children’s music, as described in the new article on Grove Music Online [subscription required], has typically been produced through a tug of war between entertainment and educational objectives. The songs on Sesame Street succeed in both, while also showing kids something about classical music itself: it’s not just for grownups. It’s a part of life that belongs to everyone. After all, who doesn’t appreciate that the moon sometimes looks like a “C”? (Though, of course, you can’t eat that, so…)

Jessica Barbour is the Associate Editor for Grove Music/Oxford Music Online. You can read her previous blog posts, “Foil thy Foes with Joy,” “Glissandos and Glissandon’ts,” and “Wedding Music” and learn more about children’s music, Marilyn Horne, Itzhak Perlman, and other performers mentioned above with a subscription to Grove Music Online.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post C is for Coloratura appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/20/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

gmo,

oxford music online,

carols,

OMO,

britten,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Grove Music Online,

A Ceremony of Carols,

Benjamin Britten,

choral music,

In Freezing Winter Night,

Jessica Barbour,

Robert Southwell,

This Little Babe,

karsh,

babe”,

Music,

Add a tag

By Jessica Barbour

Portrait of Benjamin Britten by Yousuf Karsh, via Wikimedia Commons.

One of

Benjamin Britten’s strengths as a composer was writing music for children. Not just music for children to enjoy — many of his works, particularly his operas, are not really kid-friendly affairs — but for them to perform. I’m thinking particularly of choral music, where he excelled at writing songs that I found both beautiful and really fun to sing when I was very young.

That’s not to say that these songs are easy, of course; much of Britten’s music was described by critics (often derogatorily) as “clever,” and can be highly challenging. But that’s one of the joys of singing it. His songs felt like puzzles we were given solve, and I remember feeling pretty clever when we finally pieced them together.

I was about 10 years old when I first saw A Ceremony of Carols, Britten’s multi-movement Christmas work for treble chorus and harp. I left that performance awestruck, especially by the song “This Little Babe,” which has, off and on, been stuck in my head ever since. In the years after that concert my sister and I hoped emphatically that our church’s choir would sing that song in an Advent service one Sunday; they did, eventually, but not at the breakneck speed we were hoping for.

“This Little Babe” is a Britten puzzle-piece. It begins with all voices singing one line in unison, then, like several other movements in A Ceremony of Carols, uses a canon-like structure. (In a canon, one part of the choir begins a melody, another part joins in after them singing the same melody, and the overlapping of the two or more parts creates harmony. This concept is deftly explained here by a frustrated Stephen Colbert to the band Grizzly Bear.)

But “This Little Babe” isn’t quite a round or a canon. It’s not like “Row, row, row your boat” where each voice sings exactly the same melody as every other. Nor are the entrances of each part spaced out in a way that makes the resulting harmony similar in every measure. The second verse splits the choir into two parts, the third verse in three, and each entrance in the split follows so quickly after the last (only a beat apart) that there’s a ripple effect; it doesn’t sound like harmony so much as like echoes in a racquetball court.

Performing this effect is difficult, and demands focus from the singers. The parts all end simultaneously despite their starting at different moments, which means that the second and third lines are shortened (and, therefore, melodically different) versions of the first line. These slight differences and the speed of the song make it imperative that the chorus members know their parts cold. At a length of about a minute and twenty seconds, however, the song doesn’t demand that the kids learn very much material, just that they learn it well.

Britten began work on the carols in 1942, during a sea voyage to England. He had been living in America for three years as a conscientious objector to WWII, but returned that spring. He’d recently been commissioned to write a concerto for harp, and brought some harp manuals to study on his way home. The boat he was traveling on made a stop in Halifax before crossing the Atlantic, and while on shore there he bought the excellently titled book The English Galaxy of Shorter Poems.

Among this book’s contents are Robert Southwell’s “New Heaven, New War” (from which the stanzas that make up “This Little Babe” were taken) and four other 14th-16th century poems used in A Ceremony of Carols. Britten completed drafts of seven of the carols in the five weeks before he landed in England while working concurrently on another choral piece. He reported to a friend that this happened simply because “one had to alleviate the boredom!” (Trying to calculate how many Ceremonies of Carols I could have written while bored on long trips myself has yielded depressing results.)

The final aspect of what makes “This Little Babe” so thrilling to perform is the words. The first verse begins:

This little Babe, so few days old, is come to rifle Satan’s fold;

All hell doth at his presence quake, though he himself for cold do shake;

For in this weak unarmèd wise, the gates of hell he will surprise.

If you’re the kind of kid (as I was) that preferred the Christmas carols she sang to be in a minor key, and to invoke some scary images (“We Three Kings,” “What Child is This,” or “Coventry Carol,” for example) then getting to sing the words “Satan” and “hell” in concert is something you might relish. And it’s not just that these ideas are involved — you also get to sing about their being vanquished by a tiny baby. Being a child and singing about another child who fights and wins against evil is a glorious sensation — especially when all voices come together in unison again to sing the final line: If thou wilt foil thy foes with joy, then flit not from this heavenly Boy.

“In Freezing Winter Night,” a foil to “This Little Babe,” is slower, and quieter, but its text, also by Southwell, is thematically similar. It addresses the paradox of God existing as a human baby with all the attendant weaknesses, like vulnerability to cold, but in “In Freezing Winter Night” the baby is first described as pitiful, his shivering portrayed in the chilly harmonies in the choir and dissonant harp tremolos.

Click here to view the embedded video.

It also utilizes a sort of canon, and in this one the top two voices do sing exactly the same line. But the harmonies shift underneath them, making the role of the D-sharp sung by the first voice-part different from the role of the D-sharp sung by the second voice part. This gives each line individual musical responsibility — a feeling that both are uniquely vital to the piece.

That is Britten’s gift to children’s choruses. He trusted them with exciting text and difficult music, and gave them the opportunity to make real art despite their age. Children can tell the difference. I’ve read that he originally intended this piece to be performed by a women’s choir, and I recently got to perform it with the women’s ensemble I’m in, but the best parts of that performance were the ones where I felt I was singing like a little kid, foiling my foes with joy.

Jessica Barbour is the Associate Editor for Grove Music/Oxford Music Online. You can read her previous blog posts,

“Glissandos and Glissandon’ts,” “Wedding Music,” and

“Clair de Supermoon,” or learn more about Benjamin Britten on Grove Music Online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Foil thy Foes with Joy appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/10/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

obituary,

rosen,

gmo,

oxford music online,

OMO,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Grove Music Online,

Charles Rosen,

Add a tag

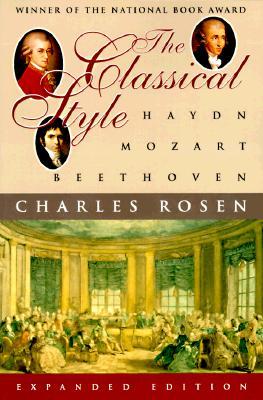

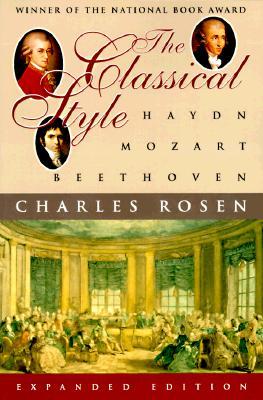

Charles Rosen, a titan of the music world, passed away on Sunday. He was a fine concert pianist, groundbreaking musicologist, and a thoughtful critic who wrote prolifically, including regular articles for the New York Review of Books, not just on music but on its broader cultural contexts. We’re excerpting his entry in Grove Music Online by Stanley Sadie below.

Rosen, Charles (Welles)

(b New York, 5 May 1927). American pianist and writer on music. He started piano lessons at the age of four and studied at the Juilliard School of Music between the ages of seven and 11. Then, until he was 17, he was a pupil of Moriz Rosenthal and Hedwig Kanner-Rosenthal, continuing under Kanner-Rosenthal for a further eight years. He also took theory and composition lessons with Karl Weigl. He studied at Princeton University, taking the BA (1947), MA (1949) and PhD (1951), in Romance languages. Some of his time there was spent in the study of mathematics; his wide interests also embrace philosophy, art and literature generally. After Princeton he had a spell in Paris, and a brief period of teaching modern languages at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But in the year of his doctorate he was launched on a pianist’s career, when he made his New York début and the first complete recording of Debussy’s Etudes. Since then he has played widely in the USA and Europe. He joined the music faculty of the State University of New York at Stony Brook in 1971.

As a pianist, Rosen is intense, severe and intellectual. His playing of Brahms and Schumann has been criticized for lack of expressive warmth; in music earlier and later he has won consistent praise. His performance of Bach’s Goldberg Variations is remarkable for its clarity, its vitality and its structural grasp; he has also recorded The Art of Fugue in performances of exceptional lucidity of texture. His Beethoven playing (he specializes in the late sonatas, particularly the Hammerklavier) is notable for its powerful rhythms and its unremitting intellectual force. In Debussy his attention is focussed rather on structural detail than on sensuous beauty. He is a distinguished interpreter of Schoenberg and Webern; he gave the première of Elliott Carter’s Concerto for piano and harpsichord (1961) and has recorded with Ralph Kirkpatrick; and he was one of the four pianists to commission Carter’s Night Fantasies (1980). He has played and recorded sonatas by Boulez, with whom he has worked closely. His piano playing came to take second place to his intellectual work during the 1990s.

Rosen’s chief contribution to the literature of music is The Classical Style. His discussion, while taking account of recent analytical approaches, is devoted not merely to the analysis of individual works but to the understanding of the style of an entire era. Rosen is relatively unconcerned with the music of lesser composers as he holds ‘to the old-fashioned position that it is in terms of their [Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven’s] achievements that the musical vernacular can best be defined’. Rosen then establishes a context for the music of the Classical masters; he examines the music of each in the genres in which he excelled, in terms of compositional approach and particularly the relationship of form, language and style: this is informed by a good knowledge of contemporary theoretical literature, the styles surrounding that of the Classical era, many penetrating insights into the music itself and a deep understanding of the process of composition, also manifest in his study Sonata Forms (1980). The Classical Style won the National Book Award for Arts and Letters in 1972. His smaller monograph on Schoenberg concentrates on establishing the composer’s place in musical and intellectual history and on his music of the period around World War I. Rosen’s interest in the thought and composition processes of the Romantics, also strong, is shown in his Harvard lectures published as The Romantic Generation. He has written many shorter articles, and contributes on a wide range of topics to the New York Review of Books.

Writings

The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (London and New York, 1971, enlarged 3/1997 with sound disc)

Arnold Schoenberg (New York, 1975/R)

‘Influence: Plagiarism and Inspiration’, 19CM, iv (1980–81), 87–100

Sonata Forms (New York, 1980, 2/1988)

‘The Romantic Pedal’, The Book of the Piano, ed. D. Gill (Oxford, 1981), 106–13

The Musical Languages of Elliot Carter (Washington DC, 1984)

with H. Zerner: Romanticism and Realism: the Mythology of Nineteenth-Century Art (New York, 1984) [rev. articles pubd in The New York Review of Books]

‘Brahms the Subversive’, Brahms Studies: Analytical and Historical Perspectives, ed. G.S. Bozarth (Oxford,1990), 105–22

‘The First Movement of Chopin’s Sonata in B-flat minor, op.35’, 19CM, xiv (1990–91), 60–66

‘Ritmi de tre battute in Schubert’s Sonata in C minor’, Convention in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Music: Essays in Honor of Leonard G. Ratner, ed. W. Allanbrook, J. Levy and W. Mahrt (Stuyvesant, NY,1992), 113–21

‘Variations sur le principe de la carrure’, Analyse musicale, no.29 (1992), 96–106

Plaisir de jouer, plaisir de penser (Paris, 1993) [collection of interviews]

The Frontiers of Meaning: Three Informal Lectures on Music (New York, 1994)

The Romantic Generation (Cambridge, MA, 1995) [based on the Charles Eliot Norton lectures delivered at Harvard; incl. sound disc]

Romantic Poets, Critics, and Other Madmen (Cambridge, MA, 1998)

Critical Entertainment: Music Old and New (Cambridge, MA, 2000) [collection of essays]

Charles Rosen

May 5, 1927 – December 9, 2012

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

The post In memoriam: Charles Rosen appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/8/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

nerve,

ultrasound,

OMO,

anesthesia,

*Featured,

mayo,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Online Products,

James Hebl,

Mayo Clinic Atlas of Regional Anesthesia and Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blockade,

Mayo Clinic Scientific Press,

Oxford Medicine Online,

Regional Anesthesia,

Robert Lennon,

Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blockade,

reding,

brachial,

plexus,

blockade,

Add a tag

The Mayo Clinic Scientific Press suite of publications is now available on Oxford Medicine Online. To highlight some of the great resources, we’ve pulled together some interesting facts about anesthesia from James Hebl and Robert Lennon’s Mayo Clinic Atlas of Regional Anesthesia and Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blockade. Get free access to the Mayo Clinic suite for a limited time with this Facebook offer (watch out, it closes today!).

(1) Egyptian pictographs dating back to 3000 BC showing a physician compressing a nerve in the antecubital fossa while an operation is being performed on the hand.

(2) William Halsted, M.D. (1852–1922; Chair, Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital), used cocaine as local infiltration as he dissected down toward major nerve trunks. He then injected cocaine around them, performing regional blockade under direct vision.

(3) In Paris in the early 1920s, a new technique for blocking the brachial plexus from an axillary approach was introduced. M. Reding, M.D., studying the anatomy of the axilla, discovered that the nerves of the plexus surround the artery in a fascial sheath. Thus, using the artery as a landmark, Reding found that the fascial compartment could be filled with local anesthetic to result in brachial plexus blockade. Reding blocked the musculocutaneous nerve, which lay outside the sheath, by infiltrating the coracobrachialis muscle.

(4) Paresthesia technique—the long-preferred method of regional anesthesiologists—was slowly replaced during the 1980s as peripheral nerve stimulation began to emerge. During its development, peripheral nerve stimulation was thought to provide superior localization of neural structures compared with blind paresthesia-seeking techniques. Peripheral nerve stimulators transmit a small electric current through a stimulating needle that, when in proximity to neural structures, causes depolarization and muscle contraction.

(5) In contemporary medical practice, regional anesthetic techniques have expanding socioeconomic and clinical implications. For example, studies evaluating patient satisfaction have found that perioperative analgesia and the avoidance of nausea and vomiting are consistently two of the highest concerns among patients.

(6) Ultrasound guidance may represent the 21st century’s version of Halsted’s anatomical dissection down to the brachial plexus.

Mayo Clinic Atlas of Regional Anesthesia and Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blockade by James Hebl and Robert Lennon is a practical guide for residents-in-training and clinicians to gain greater familiarity with regional anesthesia and acute pain management to the upper and lower extremity. It emphasizes the importance of a detailed knowledge of applied anatomy to safely and successfully performing regional anesthesia. It also provides and overview of the emerging field of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia, which allows reliable identification of both normal and variant anatomy. Mayo Clinic Atlas of Regional Anesthesia and Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blockade contains more than 200 beautifully illustrated anatomic images important to understanding and performing regional anesthesia. Corresponding ultrasound images are provided when applicable.

The Mayo Clinic Scientific Press suite of publications is now available on Oxford Medicine Online. With full-text titles from Mayo Clinic clinicians and a bank of 3,000 multiple-choice questions, Mayo Clinic Toolkit provides a single location for residents, fellows, and practicing clinicians to undertake the self-testing necessary to prepare for, and pass, the Boards and remain up-to-date. Oxford Medicine Online is an interconnected collection of over 250 online medical resources which cover every stage in a medical career, for medical students and junior doctors, to resources for senior doctors and consultants. Oxford Medicine Online has relaunched with a brand new look and feel and enhanced functionality. Our aim is to ensure that the site continues to deliver the highest quality Oxford content whilst meeting the requirements of the busy student, doctor, or health professional working in a digital world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Six facts about regional anesthesia appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/6/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

Geography,

mars,

gmo,

oxford music online,

place of the year,

OMO,

POTY,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Grove Music Online,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

Claudio Monteverdi,

Gustav Holst,

Kyle Gann,

Add a tag

By Kyle Gann

By long tradition, sweet Venus and mystical Neptune are the planets astrologically connected with music. The relevance of Mars, “the bringer of war” as one famous composition has it, would seem to be pretty oblique. Mars in the horoscope has to do with action, ego, how we separate ourselves off from the world; it is “the fighting principle for the Sun,” in the words of famous astrologer Liz Greene. Michel Gauquelin, who conducted a statistical test for the validity of astrology, found that Mars near the ascendant or midheaven in a person’s chart correlated heavily with choosing athletics or surgery as a career: it connects to physical competition and knives. Mars also rules everything military, and thus in music it is associated mainly with percussion. Most composers have egos, but musicians are not generally a physically aggressive bunch, and fighting isn’t our area. Many a famous composer sat out World War II playing in the Army band. (In high school I was thrilled that my simply taking music classes exempted me from the gym requirement — under the institutional assumption that all music students would get enough exercise in the marching band. I was a pianist.)

Claudio Monteverdi

And so Mars, in the classical music world, has been only an occasional acquaintance. There isn’t much classical music about athletics, though Arthur Honegger did write a rather punchy tone poem called

Rugby (1928), and Charles Ives — a star baseball player in youth — portrayed a

Yale-Princeton Football Game in music around 1899 as a kind of college prank. Music specifically about surgery may have yet to appear (and let’s leave Salomé out of this). Seeking a connection between Mars and music,

Gustav Holst would probably leap to most minds, but I think first of

Claudio Monteverdi. Holst, after all, had to give all his planets equal treatment, but it was Monteverdi who invented the “stile concitato,” the agitated style, to restore in music what he saw as a warlike mode known in poetry but historically absent in music. He made his theories explicit in his scenic cantata

Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda of 1624, its poem a kind of forced sexual encounter disguised as a battle between armed rivals. Monteverdi makes it quite clear what he considered warlike tones:

lots of quick repeated notes in a harmonic stasis. And if you think about it, that description applies equally well to

“Mars” from Holst’s Planets (1914–16), with its hammering, one-note ostinato, and, as we’ll see below, to most other battle pieces as well. Considering the phenomenal evolution of the actual military, its musical signifiers have remained strikingly consistent.

Despite Monteverdi’s continued advocacy in some subsequent Madrigali guerrieri of 1638, the stile concitato did not establish itself as a broad genre. In the centuries following Il combattimento, depiction of martial action is rare enough in music for the well-known instances to be easily enumerated. The first of Johann Kuhnau’s Biblical History sonatas (1700) purports to describe David’s conflict with Goliath, once again with a profusion of quick repeated notes; also with “martial” rhythms such as streams of dotted eighths followed by sixteenths, or the snare-drum rhythm of an eighth and two sixteenths. The Battalia a 9 (1673) of Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber is for only strings, but it too makes a fetish of chords in repeated notes. Its “Der Mars” movement, in addition, brilliantly asks for a piece of paper between the fingerboard and strings of the cello to make the instrument’s rhythmic drone sound plausibly like some kind of drum. Michel Corrette’s Combat Naval from his Harpsichord Divertimento No. 2 (1779) likewise starts off with repeated notes in snare-drum rhythms, and climaxes with forearm clusters that quite effectively signify cannon blasts. In Mozart’s and Haydn’s generations, even the presence of drums and cymbals was enough to suggest Turkish and thus military connotations (since what were the Turks there for, except to make war with?), as in Haydn’s “Military” Symphony, No. 100.

The advent of Romanticism, though, marked a turn at which war became demoted as a subject for serious musical treatment. Two of the 19th century’s most high-profile musical depictions — Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory (1813) and Liszt’s Hunnenschlacht (1857) — are considered among their most embarrassingly literal and superficial works. Bruckner did claim that the Plutonian finale of his Eighth Symphony (1887) depicted two emperors meeting on the field of battle, but that was rather after the fact, since he was trying to throw his lot in among the programmaticists. All this suggests, I think, distinct unease among classical musicians with things military or violent. Of course military music is sometimes appropriated to good effect, as in Berlioz’s Rakoczy March from The Damnation of Faust (1846). But despite Monteverdi’s heroic attempt to establish a martial mode, in retrospect classical attempts to depict battle tend to become anomalous oddities from history (Corrette, Biber) or humorous superficialities (Beethoven, Liszt).

Carl Nielsen

Finally, in the 20th century, the increase in dissonance and percussion brought at least a more respectable realism to battle music, though the carnage of the World Wars made anti-war statements more popular than celebrations of famous victories.

Carl Nielsen’s Fifth Symphony (1922) was a powerful response to the lunacy of World War I, with a first movement in which a solo snare drum seems determined to halt the progress of the orchestra, whose humanistic main theme finally overwhelms it. A couple of conflagrations later, Stravinsky made an anti-war statement in his

Symphony in Three Movements (1945), partly inspired by film images of goose-stepping Nazi soldiers. Less ironically, George Antheil cheered the Allies along with his

Fifth Symphony, subtitled “1942” and written that year as the fortunes of war were changing in North Africa. Shostakovich, in his

Leningrad Symphony (1941), wrote melodies to symbolize the mutual approaches of the German and Russian armies, though the German theme is arguably a rather silly one; at least, Béla Bartók took savage delight in satirizing it in his

Concerto for Orchestra. During the war even the more abstract-leaning Stefan Wolpe wrote a

Battle Piece (1943-7) for piano — once again marked by repeated notes.

The massive War Requiem (1961-2) by the pacifist Benjamin Britten, however — perhaps its century’s grandest anti-war musical protest, filled with snare-drum march rhythms and trumpet fanfares suspended in uneasy irony — seems to close a curved trajectory that opened with Monteverdi’s Il combattimento. Whereas musicians once thought the military mode in music could be innocently brought up with historical interest or patriotic pride, today we invoke it only to condemn it. The Vietnam War era may have rendered any non-pejorative expression of Mars verboten for the foreseeable future. In recent years the pianist Sarah Cahill commissioned anti-war pieces from many composers (Frederic Rzewski, Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, and Meredith Monk among them) for a project called “A Sweeter Music”; my own contribution, War Is Just a Racket, uses a 1933 text by General Smedley Butler, lamenting the army’s too-close ties to corporate interests.

Yet perhaps because Mars and Neptune were conjunct when I was born, I’ve written one un-ironic piece of battle music myself. Aside from the “Mars” movement of my own Planets (yes, I was foolhardy enough to compete with Holst, but my “Mars” is more complaining than belligerent), I depicted the battle of the Little Bighorn in my one-man electronic cantata Custer and Sitting Bull (1999), replete with sampled gunfire. The Sioux warriors are in one key, the US Cavalry in another a tritone away, and as they take turns the music jumps between two different tempos. But there’s something so peculiar about the expression of Mars in music that I have to wonder if, a couple of centuries from now, that battle scene will survive only as a curious anomaly, like Battalia a 9 or the Combat Naval or the battle of David and Goliath.

Kyle Gann is a composer who writes books about American music, including, so far; The Music of Conlon Nancarrow; American Music in the Twentieth Century; Music Downtown: Writings from the Village Voice; No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage’s 4’33”; Robert Ashley; and, coming up in 2015, a book on Ives’s Concord Sonata. His music explores tempo complexity and microtonality. He writes the blog, Postclassic and teaches at Bard College.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World – the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mars and music appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 9/4/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

sibelius,

gmo,

oxford music online,

OMO,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Grove Music Online,

John Zorn,

Meghann Wilhoite,

zorn,

zorn’s,

tzadik,

megwilhoite,

meghann,

wilhoite,

at grove,

Add a tag

By Meghann Wilhoite

It’s difficult to pin a label on John Zorn. Active since the early 70s, Zorn has effectively woven his peculiar style of musical experimentation into the fabric of New York City’s downtown scene. His work — in the general sense of the word — has varied from philanthropic to shocking, with a curatorial bent that has often held quite a bit of sway.

Where to start? I could talk about Zorn’s music venue, The Stone, which pays for itself through CD sales and other contributions, so that “100% of the nightly revenue” goes directly to the performing musicians.

Or I could talk about his Obsessions Collective, a “non-profit alternative to the commercial Arts scene,” which boasts zero overhead so that, like with The Stone, every cent derived from sales goes directly to the artists.

Or maybe I should tell you about Zorn’s record label, Tzadik, which releases the work of contemporary composers “who find it difficult or impossible to release their music through more conventional channels.”

But perhaps I should first tell you about his “radical Jewish music” projects, which found initial voice when Zorn curated the Art Projekt Festival in Munich in 1992, and resulted in what has since been considered a sort of radical Jewish music manifesto (written by Zorn and guitarist Marc Ribot).

What I really don’t want to do is try to “describe” the MacArthur Fellow’s music to you — because, to be honest, it’s almost impossible. Sometimes it’s noise, sometimes it’s atonal, sometimes it’s klezmer, sometime it’s jazz. It’s always pushing the boundaries of what you think it will be.

In honor of Zorn’s 59th birthday (which took place over the weekend), why don’t we just enjoy this clip from 1991, featuring Zorn’s group Naked City performing at the Vienna Jazz Festival? Be warned, this might fall in the “shocking” category for you! (Zorn is the one the camouflage trousers and that’s Mike Patton from Faith No More on vocals.)

Click here to view the embedded video.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts: “Saving Sibelius: Software in peril” and “The king of instruments: Scary or sleepy?”

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

By: Rebecca,

on 4/1/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Gil Scott-Heron,

OMO,

The Revoltion Will Not Be Televised,

Music,

History,

Politics,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

birthday,

Add a tag

On April 1, 1949, Gil Scott-Heron was born. To celebrate his birthday we turned to Oxford Music Online which led us to The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Below we have excerpted his biography.

b. 1 April 1949, Chicago, Illinois, USA. Raised in Jackson, Tennessee, by his grandmother, Scott-Heron moved to New York at the age of 13. His estranged father played for Glasgow Celtic, a Scottish soccer team. Astonishingly precocious, Scott-Heron had published two novels (The Vulture and The Nigger Factory) plus a book of poems (Small Talk At 125th And Lenox) by 1972. He met musician Brian Jackson when both were students at Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, and in 1970 they formed the Midnight Band to play their original blend of jazz, soul and prototype rap music. Small Talk At 125th And Lenox was mostly an album of poems (from his book of the same name), but later albums showed Scott-Heron developing into a skilled songwriter whose work was soon covered by other artists: for example, LaBelle recorded his ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’ and Esther Phillips made a gripping version of ‘Home Is Where The Hatred Is’. In 1973, Scott-Heron had a minor hit with ‘The Bottle’, a song inspired by a group of alcoholics who congregated outside his and Jackson’s communal house in Washington, DC. Winter In America (on which Jackson was co-credited for the first time) and The First Minute Of A New Day, the latter for new label Arista Records, were both heavily jazz-influenced, but later sets saw Scott-Heron and Jackson exploring more pop-orientated formats, and in 1976 they scored a hit with the disco-based protest single, ‘Johannesburg’. During this period they began working with pioneering electronic producer Malcolm Cecil from Tonto’s Expanding Headband, with the duo’s musical emphasis naturally shifting to synthesizer-based sounds.

One of Scott-Heron’s best records of the 80s, Reflections (1981), featured a fine version of Marvin Gaye’s ‘Inner City Blues’; however, his strongest songs were generally his own barbed political diatribes, in which he confronted issues such as nuclear power, apartheid and poverty and made a series of scathing attacks on American politicians. Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Barry Goldwater and Jimmy Carter were all targets of his trenchant satire, and his anti-Reagan rap, ‘B-Movie’, gave him another small hit in 1982. An important forerunner of today’s rap artists, Scott-Heron once described Jackson (who left the band in 1980) and himself as ‘interpreters of the black experience’. However, by the 90s his view of the development of rap had become more jaundiced: ‘They need to study music. I played in several bands before I began my career as a poet. There’s a big difference between putting words over some music, and blending those same words into the music. There’s not a lot of humour. They use a lot of slang and colloquialisms, and you don’t really see inside the person. Instead, you just get a lot of posturing’.

In 1994, Scott-Heron released his first album for 10 years, Spirits, which began with ‘Message To The Messengers’, an address to today’s rap artists: ‘… Young rappers, one more suggestion before I get out of your way, But I appreciate the respect you give me and what you got to say, I’m sayin’ protect your community and spread that respect around, Tell brothers and sisters they got to calm that bullshit down, ’Cause we’re terrorizin’ our old folks and we brought fear into our homes’. Scott-Heron’s life was becoming increasingly bedevilled by drug addiction, however, and in 2001 he was imprisoned for three years for cocaine possession. It was a tragically ironic fate for an artist who had preached so eloquently about the danger of drugs. Scott-Heron and Jackson revived their musical partnership following the former’s release from prison in 2003

A style as specific as Grove’s lends itself well to parody, so it’s perhaps no surprise that in the first edition of New Grove, a couple of well-honed articles slipped by the sharp eyes of editor in chief

A style as specific as Grove’s lends itself well to parody, so it’s perhaps no surprise that in the first edition of New Grove, a couple of well-honed articles slipped by the sharp eyes of editor in chief