Viewing Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani, Most Recent at Top

Results 1 - 25 of 111

Books, babies, life, and everything in between!Statistics for Anita and Amit Vachharajani

Number of Readers that added this blog to their MyJacketFlap: 1

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

‘Probably his tongue.’

Which the cousin warned us

Some mud, tinged maroon

With your drying blood.

That sudden laugh.

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

|

Stepping out into the sun, how could I not laugh out loud at Shanthamani Muddaiah’s Backbone, a sculptural installation in the shape of a large spinal column? With my back brace on, carrying my cushion, I had to selfie!

Stepping out into the sun, how could I not laugh out loud at Shanthamani Muddaiah’s Backbone, a sculptural installation in the shape of a large spinal column? With my back brace on, carrying my cushion, I had to selfie! Bharti Kher’s giant wooden triangles loomed at us from inside a large room in the Pepper House. Like a giant baby’s cradle toys, they hung from the ceiling and reminded me of the huge wooden dividers and protractors our maths teacher used to bring to class so that all 64 of us could watch her plot an angle on the board. Not surprisingly, Kher’s display is related to navigation and geometry. Called Three decimal points, Of a minute, Of a second, Of a degree , it’s great fun to look at. The Penrose Triangle is one of the geometric entities Kher’s work refers to.

Bharti Kher’s giant wooden triangles loomed at us from inside a large room in the Pepper House. Like a giant baby’s cradle toys, they hung from the ceiling and reminded me of the huge wooden dividers and protractors our maths teacher used to bring to class so that all 64 of us could watch her plot an angle on the board. Not surprisingly, Kher’s display is related to navigation and geometry. Called Three decimal points, Of a minute, Of a second, Of a degree , it’s great fun to look at. The Penrose Triangle is one of the geometric entities Kher’s work refers to. The last bits of the KMB we saw were the street art – the mind-blowing Debtor’s Prison by BC or the Backyard Civilization. I don’t think the piece was commissioned for the KMB specifically, but truly, what a treat it was to turn a corner of a road and suddenly see these colours and the details of the mural!

The last bits of the KMB we saw were the street art – the mind-blowing Debtor’s Prison by BC or the Backyard Civilization. I don’t think the piece was commissioned for the KMB specifically, but truly, what a treat it was to turn a corner of a road and suddenly see these colours and the details of the mural!

Pic credits: Mostly to Amit, and a few to me.

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

So home was always just slightly off-kilter, a very informal, very to-hell-with-rituals sort of place. Not that my parents were itinerant or irresponsible – far from it. They were just your average hard-working immigrants who had a decidedly rationalistic outlook to life. I grew up without many of the rules most ‘70s kids had to deal with. I don’t remember having too many toys or clothes, but what I did have, as a gift from mom, for as long as I can remember, was the right to always, but always, voice my opinion and do just as I wanted. (And boy, did that come back to bite her!)

When I was 9-and-a-half, my dad died. Much changed in our lives – I felt like I’d moved out of the pleasant fog of childhood into a crystal-sharp reality. With one less adult around, our clock got wound a lot less and developed an eccentricity. It began to gain time. Once wound, it would go faster by a few minutes every day. We discovered this quite accidentally. Initially, we could never predict how much faster it was – but in a while we figured out that it usually gained time in multiples of five.

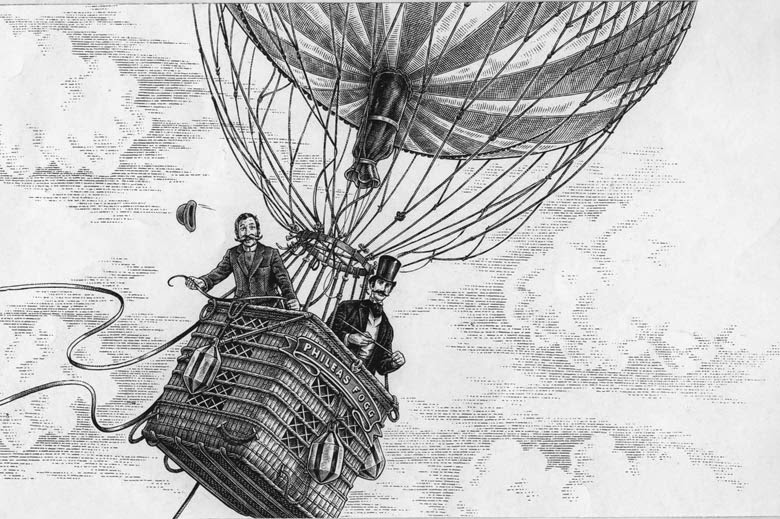

Honestly? I don’t know. All I can say is that I remember the excitement of that moment in Around the World in 80 Days when Phileas Fogg and Passpartout return to London, dejected, believing that they have lost Fogg’s bet. Only to find out that they have, in actual fact, gained a whole day. The author – in a totally pedagogical exercise – explains how time is gained when you travel from West to East and back again, in small accumulations of 5 minutes each day, dropping like coins into a box. And something about that careful calibration of time – minute for minute – appeals to me, and makes me feel like I’m in a race against myself.

Honestly? I don’t know. All I can say is that I remember the excitement of that moment in Around the World in 80 Days when Phileas Fogg and Passpartout return to London, dejected, believing that they have lost Fogg’s bet. Only to find out that they have, in actual fact, gained a whole day. The author – in a totally pedagogical exercise – explains how time is gained when you travel from West to East and back again, in small accumulations of 5 minutes each day, dropping like coins into a box. And something about that careful calibration of time – minute for minute – appeals to me, and makes me feel like I’m in a race against myself.It keeps me tethered to that quirk-filled household of my mother's even as I obsess about stuff like breakfast, the two tiffins, the two precise pony tails, and so much else.

So yes. In short, the clocks in our house continue to be set ahead of time. For no particular reason.

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

Our little suburb has changed so much in three years - and not in nice ways either. Fewer trees, more heritage-category bungalows that have been demolished, more high-rises in their place, and a real-estate-market-driven 'Chembur Festival'. It's getting increasingly anodyne, and spiralling home-buying costs mean that more of the terribly-rich come in. And once that happens, there goes the neighbourhood!

Feels silly posting this now, so many years later, but the piece has its moments - I think!

I love Chembur

But you mustn’t think of Chembur as a bucolic hick-town. We’ve been groped by glamour in our day. Raj Kapoor built the RK Studios here in 1950, and between the ’60s to the ’80s, stars like Ashok Kumar, Nalini Jaiwant, Shivji-ke-filmi-avtar, Trilok Kapoor, the redoubtable Kishore Sahu, and lovable Dhumal lived here. Shilpa Shetty was my junior in school (I personally have no recollection of this, but hey, that was many surgeries ago!) and so, they tell me, was Vidya Balan. Anil Kapoor and Shankar Mahadevan attended the boys’ school across the playground from ours.

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

|

| Earrings Hansa once made me |

|

| Bike-riding girl wends her way thru the landscape |

Hansa builds little cityscapes with girls riding bicycles, makes small photo boxes with newspaper cuttings of her friends’ favourite artists and attempts small animations where she frickin’ makes every prop and character.

|

| Shoebox house with driftwood tree |

|

| Detail from shoebox house |

We’re two days down now in our summer art project, N and I, and I can already sense my internal discomfort, a restless shifting-of-the-feet. I don’t know what to paint. But I feel like I want to write a little. The good professor in the article said he reached the ‘what next’ point at the end of three weeks. Yoohoo! Guess who got there on Day 3?

|

| The Fragrant Ant is mine and the chalk pastel Waterfall is N's |

|

| Painting 1.5, wet butterflies |

|

| Painting 2, Day 2, a dragon in the making |

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

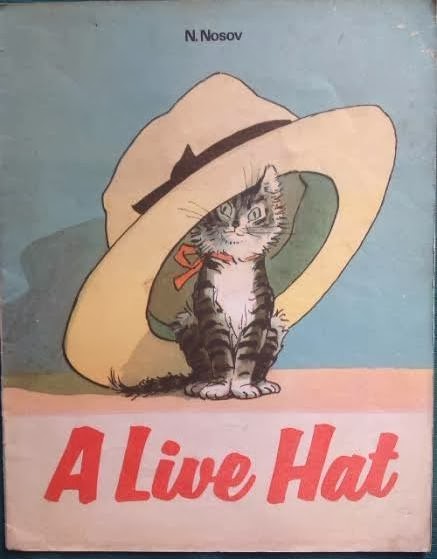

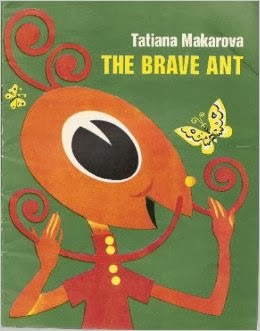

Two of the books we recently found did that for us – The Live Hat for me, and the The Brave Ant for Amit. Here are images from some lovely old picture books (uploading pics on Blogger is not fun – or satisfying!).

| photo 1-1 | photo 1-2 | photo 1-3 |

|

|

The Brave Ant by Tatiana Makarova. Illustrated by Gennadi Pavlishin. Translated into English by Fainna Glagoleva. Written circa 1940, English translation: Progress Publishers, 1976. When we found this book, Amit gasped because it brought to mind his many attempts to draw out the luminous pictures as a kid. Truly, my image doesn't do justice to that respectable mosquito and his leaf-letter! Try this page for a few images from the book. You'll have to scroll down, though.

| photo 1-1 | photo 1-2 | photo 1-3 |

Life with Grandmother Kandiki (below) by Anna Garf. Illustrated by Victor Duvidov. 0828511829 In wraps. Translated by Joy Jennings.

| photo 1-1 | photo 1-2 | photo 1-3 |

Gallant and Dopey, Pages from a Dog's Scrapbook, by Marjorie Turner. Raphael Tuck & Sons, Tuck Books (more about them and their lovely postcards later!). 1930. Please head to Cyndee Marcoux's page for see some really good quality images of each page. Two below are from her pinterest page.

| photo 1-1 | photo 1-2 | photo 1-3 |

The White Deer, (below) a Latvian Folk Tale. Translated from the Russian by Fainna Solasko. Illustrations by Nikolai Kochergin. Progress Publishers, 1973. The most jewel-bright of all the books we have!

photo 1-1

photo 1-2

photo 1-3

The Wolf who Sang Songs by Boris Zakhoder (below). Illustrated by V Chizhikov and Translated by Avril Ryman. Progress Publishers, 1973. You can see beautiful scans of whole pages of the comically-drawn book here.

.jpg)

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

Let’s ban longing.

No more should it be allowed to seep into the mind like rainwater that comes in from the poorly-built window next to the porous wall.

Use newspaper, quickly, in sheaves, to suck up the water that seeps in without pause,

And hope that the rain, with its delirious smells, will stop.

But rain, like longing, knows how to defeat you into quiet hopefulness.

It knows the power of perfume and persistence,

So that finally, all there is, is abject surrender to the wetness.

Let’s ban longing.

Let’s say no more of this shit.

Let’s stop the clouds from gathering droplets into themselves

And swelling up till they can hold it in no more.

Let’s sit by our feeble selves and protest.

Let’s ban clouds from gathering and letting go of their promise at our windows.

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

But she was strangely grim. She pointed out to a large residential building. ‘That thing wasn’t supposed to be there because it was on the path of the Freeway. We didn’t allow them to go ahead with it. But later, they bribed someone...’ All her work life, mum had dodged the bribe bullets by the simple expedient of not taking any. It sometimes made things awkward at work, but being a gentle, very pragmatic soul, she managed to opt out without ruffling too many feathers.

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

Do Ankhen... was V Shantaram’s 1957 classic on the rehabilitation of criminals. It was visually powerful and dramatic in a grand, pull-out-your-guts-and-roll-in-them way. I’d been raised on the tepid diet of 1970s Indian television, and the film didn’t so much blow my circuits, as it smashed them and danced on the pieces. My Do Ankhen... nightmare continued to terrorise me for a year or two.

Do Ankhen... was V Shantaram’s 1957 classic on the rehabilitation of criminals. It was visually powerful and dramatic in a grand, pull-out-your-guts-and-roll-in-them way. I’d been raised on the tepid diet of 1970s Indian television, and the film didn’t so much blow my circuits, as it smashed them and danced on the pieces. My Do Ankhen... nightmare continued to terrorise me for a year or two.Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

This article appeared in the DNA of Sunday, May 6, 2012.

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

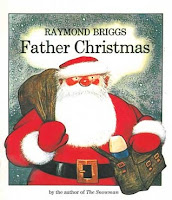

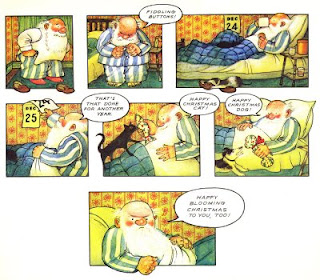

Now normally, sentimentality tends to sicken me, and so I keep away from books full of silly tropes on festivals. But this one seemed strange, with a grim, definitely unsentimental Father Christmas (and from now on, I'll just call him FC) on the cover. I think what got me was the thermos in the satchel. When the book came off the lending list and on to the withdrawn one, it came home with us!

Now normally, sentimentality tends to sicken me, and so I keep away from books full of silly tropes on festivals. But this one seemed strange, with a grim, definitely unsentimental Father Christmas (and from now on, I'll just call him FC) on the cover. I think what got me was the thermos in the satchel. When the book came off the lending list and on to the withdrawn one, it came home with us!

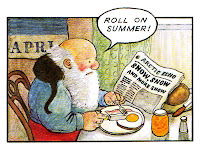

Full of what a critic called a 'gloomy magic' the book begins with FC waking up from a dream of a sunny beach, slamming his alarm clock which shatters the warm dream, and realising that 'bloomin' christmas' is here again. He is a curmudgeon, and sets about doing his chores carefully, grumpily, sincerely. Feeding his pets - a cat, a dog, a few reindeer, making his tea and his breakfast, packing sandwiches and coffee in a thermos for the journey.

Full of what a critic called a 'gloomy magic' the book begins with FC waking up from a dream of a sunny beach, slamming his alarm clock which shatters the warm dream, and realising that 'bloomin' christmas' is here again. He is a curmudgeon, and sets about doing his chores carefully, grumpily, sincerely. Feeding his pets - a cat, a dog, a few reindeer, making his tea and his breakfast, packing sandwiches and coffee in a thermos for the journey. He flies over all sorts of weather (mostly Western) and lands in odd places like sloping roofs with inconvenient chimneys (from the sleigh-parking point of view) and small vans with no chimneys (from the entering point of view). And igloos ('At least there are no chimneys!'). Not to mention the pain of getting gifts into a lighthouse.

The details in the book are what get you - the small things, the large, the ordinary, the quotidien. Like FC sitting on a roof, eating his sandwiches and listening to the weather forecast. Like him getting caught among bloomin' TV aerials (remember it was written in 1973 :)) and tripping on bloomin' cats. He gets a cold, has to climb stairs, stairs, stairs, and finally, someone has the brains to leave him some alcohol.

When he is nearly done, he runs into a milkman. The milkman was Briggs' tribute to his own father, a milkman, who had a similar duty - one of waking up early, and setting off to make deliveries - every day, come rain, shine or snow. All of FC's troubles with snow - even his morning chore-doing - were Briggs' father's too.

When he gets back homes, finally, FC is a sooty, cold, tired man. But he does his chores - feeds the animals, keeps them warm, then bathes, puts on some talc, curls up with travel brochures featuring warm places, cribs about his presents and finally, makes himself dinner!

When he gets back homes, finally, FC is a sooty, cold, tired man. But he does his chores - feeds the animals, keeps them warm, then bathes, puts on some talc, curls up with travel brochures featuring warm places, cribs about his presents and finally, makes himself dinner!The other Briggs N really took to was Fungus the Bogeyman (1974), so full of dirt and grime and boils and slime, that I wonder what appealed to her. But appeal it did. Again an amazing book, drawn with so much love and detail and colour, that it seeps into your mind (yes) and makes you smile!

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

And every now and then, things of beauty and innate value pop up on Facebook. For stay-at-home moms like me (and non-moms as well) it’s a window into magic which happens elsewhere in the world of art and technology. Thanks to Facebook shares, I’ve seen lots of lovely films, art, craft, writing – and cakes! One of the nicest finds recently has been a 20-year-old book called The Rights Of A Reader by Daniel Pennac. A friend shared a link to a hilarious promotional poster of the book drawn by Quentin Blake. The title was intriguing. Whoever heard of rights for readers? I ordered the book to find out.

And every now and then, things of beauty and innate value pop up on Facebook. For stay-at-home moms like me (and non-moms as well) it’s a window into magic which happens elsewhere in the world of art and technology. Thanks to Facebook shares, I’ve seen lots of lovely films, art, craft, writing – and cakes! One of the nicest finds recently has been a 20-year-old book called The Rights Of A Reader by Daniel Pennac. A friend shared a link to a hilarious promotional poster of the book drawn by Quentin Blake. The title was intriguing. Whoever heard of rights for readers? I ordered the book to find out.A writer of children’s books, Pennac is also a parent and a teacher. And The Rights… grew from his experience of trying to inspire a bunch of not-so-bright teenagers to read. Pennac examines three fundamental issues: how much small children love hearing stories; how wonderful it is when they discover they can put letters together and actually read; and how between parents and schools, we push kids away from books in the years that follow.

Pennac’s tip for getting kids — of all ages — to read is simple: read to them. If you are a reader, chances are someone read to you when you were small. This is instinctive with most parents. Present reading to the child as an engaging activity that you love, and the child will grow to love it too. I know this is true because my mom patiently read to me till the day I took the book out of her hands.

There are habits that foster reading — we all evolve these instinctively for ourselves as readers. Pennac calls these ‘reader’s rights’. It’s just that when we become parents and teachers, we forget them. Readers, for instance, have the right to skip pages. We all do this, but not many of us like our kids doing so. Also, readers have the right to not read and the right to read anything – anywhere. Even comics while sitting on the pot.

There are many parental habits vis-à-vis reading that Pennac disapproves of. Monitoring children’s reading is one, as is the need to test kids and ask them to ‘describe’ what they just read. I’m guilty of both. Because I want to be a part of her life, I often ask my daughter what happened in the book she just read. She loves telling me about them on some days, and on others, she does not, probably because as Pennac observes, ‘Reading is a retreat into silence… it is about sharing, but a deferred and fiercely selective kind of sharing’.

To some of us reading is a special kind of oxygen. We need it. Others don’t. As parents and educators, our job is simply to enable kids to read. Whether they read later or not is their choice. As Pennac reminds us, while it’s fine for a child to grow up and reject reading, ‘it’s totally unacceptable for someone to feel that they have been rejected by reading’. Wise words indeed!

This post first appeared in the DNA of June 10, 2012.

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

And every now and then, things of beauty and innate value pop up on Facebook. For stay-at-home moms like me (and non-moms as well) it’s a window into magic which happens elsewhere in the world of art and technology. Thanks to Facebook shares, I’ve seen lots of lovely films, art, craft, writing – and cakes! One of the nicest finds recently has been a 20-year-old book called The Rights Of A Reader by Daniel Pennac. A friend shared a link to a hilarious promotional poster of the book drawn by Quentin Blake. The title was intriguing. Whoever heard of rights for readers? I ordered the book to find out.

And every now and then, things of beauty and innate value pop up on Facebook. For stay-at-home moms like me (and non-moms as well) it’s a window into magic which happens elsewhere in the world of art and technology. Thanks to Facebook shares, I’ve seen lots of lovely films, art, craft, writing – and cakes! One of the nicest finds recently has been a 20-year-old book called The Rights Of A Reader by Daniel Pennac. A friend shared a link to a hilarious promotional poster of the book drawn by Quentin Blake. The title was intriguing. Whoever heard of rights for readers? I ordered the book to find out.A writer of children’s books, Pennac is also a parent and a teacher. And The Rights… grew from his experience of trying to inspire a bunch of not-so-bright teenagers to read. Pennac examines three fundamental issues: how much small children love hearing stories; how wonderful it is when they discover they can put letters together and actually read; and how between parents and schools, we push kids away from books in the years that follow.

Pennac’s tip for getting kids — of all ages — to read is simple: read to them. If you are a reader, chances are someone read to you when you were small. This is instinctive with most parents. Present reading to the child as an engaging activity that you love, and the child will grow to love it too. I know this is true because my mom patiently read to me till the day I took the book out of her hands.

There are habits that foster reading — we all evolve these instinctively for ourselves as readers. Pennac calls these ‘reader’s rights’. It’s just that when we become parents and teachers, we forget them. Readers, for instance, have the right to skip pages. We all do this, but not many of us like our kids doing so. Also, readers have the right to not read and the right to read anything – anywhere. Even comics while sitting on the pot.

There are many parental habits vis-à-vis reading that Pennac disapproves of. Monitoring children’s reading is one, as is the need to test kids and ask them to ‘describe’ what they just read. I’m guilty of both. Because I want to be a part of her life, I often ask my daughter what happened in the book she just read. She loves telling me about them on some days, and on others, she does not, probably because as Pennac observes, ‘Reading is a retreat into silence… it is about sharing, but a deferred and fiercely selective kind of sharing’.

To some of us reading is a special kind of oxygen. We need it. Others don’t. As parents and educators, our job is simply to enable kids to read. Whether they read later or not is their choice. As Pennac reminds us, while it’s fine for a child to grow up and reject reading, ‘it’s totally unacceptable for someone to feel that they have been rejected by reading’. Wise words indeed!

This post first appeared in the DNA of June 10, 2012.

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

I couldn’t have been more wrong. This is one of those rare things in non-fiction: an Unputdownable. Robins’ account of the East India Company’s business practices in India is a riveting blend of crisp, almost thriller-like writing with a great amount of intelligence and passion. While we all pretty much know the broad outlines of what happened, Robins looks at that time in Indian and British history so closely, and with such a unique perspective, that you can’t help but be swept along on his fascinating journey.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. This is one of those rare things in non-fiction: an Unputdownable. Robins’ account of the East India Company’s business practices in India is a riveting blend of crisp, almost thriller-like writing with a great amount of intelligence and passion. While we all pretty much know the broad outlines of what happened, Robins looks at that time in Indian and British history so closely, and with such a unique perspective, that you can’t help but be swept along on his fascinating journey. Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

People who have kids, that’s who.

Certainly, we can be broadly classified under the title of Parentis Lunaticus, but if you were to look at us carefully, you would see subtle differences. And the best place to spot these differences is outside the average well-heeled school. This is where parents of a certain class gather in large numbers at regular intervals — and gravitate towards others who are a little more like themselves. (When I say ‘parents’, I really mean mothers; because despite my best efforts to not think in stereotypes, rarely do I see dads in these primitive huddles!)

Waiting to give their kids dabbas or to pick them up, are armies of mommies. Some are exquisitely coiffeured, perfumed and designer-kurta-clad; others are in the JLo/Beyonce mould, bumble-bee-glares, skin-fit jeans and all. Then there are those who wear leopard-print stilettos to match leopard-print capris in the exact same colour as their recently-gone-blonde hair. The rest are a broad swathe of well-dressed women, with a few stragglers, like yours truly, who look like they barely managed to pull on something before leaving home.But the real difference between us moms is not how well-groomed we are. It is the level of naked ambition we feel on behalf of our kids. Everything we wept at during Taare Zameen Par is quickly forgotten once inside the bubble of naked ambition and hysteria that exists around schools. This is Comparison Central, where certificates for extracurricular activities won by kids are shown off, gifts for teachers are secretly planned, and next year’s classes are discussed.

Generally, you can spot the really ambitious moms easily. Firstly, they talk non-stop in glowing terms about their kids and the classes they go to, and secondly, they flatter teachers and sidle around them on occasions like Teacher’s Day, Christmas and Divali, coaxing them to accept cakes, gifts and bouquets.

Each school has its own demographic, and in ours, the most ambitious moms huddle in two large and mututally-exclusive clusters. The larger, chattier cluster is made up of Gujarati moms. The smaller is made up of equally driven South-Indian moms (being a Malayalee married to a Gujarati, I scuttle around the fringes of the Southie cluster).

Each cluster has its own mores and manners. The Gujju moms have all the hottest tuition teachers and classes on speed dial. They know everyone who matters on the PTA; have direct access to the teachers, and can tell you the best places to eat, play or study. Nothing can come between their kids and success or happiness, because all’s fair in love, dhando and education. But refreshingly, they also believe in th

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

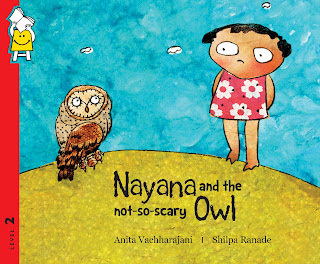

and bringing joy into my life on an otherwise dull day was this new book, drawn by the wonderfully talented shilpa ranade :)

it was written three years back and has been two years in the making, but what a louliness!

more strength to pratham, the guys who have created this space for affordable picture books that are pulished in english but are also translated into 5 other indian languages. i'm waiting for my language copies - hindi, kannada, mallu, marathi etc :)

http://store.prathambooks.org/ecommerce/control/productSummary;jsessionid=9BC0CC919785102DE21870846F1C64A5.jvm1?productId=9788184792706

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

as a boyfriend-starved college student, I knew one thing for a fact: the dreary Sahara desert of my lovelife was made more wretched by the fact that I had grown up going to an all-girls’ school. Boys were exotic creatures for us. We only met them inside the pages of books. In college, where they appeared in human form, we had no idea what to say to them.

While the co-educated girls seemed to make male friends easily, our little gang of girls-schooled late-bloomers found ourselves in fairly splendid isolation. We weren’t sad about it, of course, but we did conclude eventually that all-girls’ and all-boys’ schools were the earthly representations of hell. It was weird, because unlike the co-ed girls, we were actually very uninhibited, we laughed loudly, talked a lot; were witty, uncensored and hilarious. What we were not able to do, though, was have normal, relaxed friendships with boys. We swayed from being arch and flirtatious to completely stern and reproving.

My little girl goes to a mixed-sex or a co-ed school. One day, in Senior KG, she came home and told me that a boy had put his head on her lap and kissed her. Images flashed through my mind: Silsila. Rekha’s head on Amitabh’s lap. Mist. Flowers touching. Bees buzzing. Major coochie-cooing. I sat up with a start and asked my husband if I should go talk to the teacher about this Emraan-Hashmi-in-the-making. ‘No!’ replied the co-ed schooled man, ‘You’ll just traumatise the poor boy!’

Feeling traumatised myself I remembered my mother’s utter terror of co-eds and her dire warnings against sending her granddaughter to one. Mom went to a convent school and then studied engineering while staying in a girls’ hostel run by nuns. The Mother Superior there often warned them with these wise — and rather poetic — Malayalam words: ‘Whether a thorn falls on a grape, or a grape falls on a thorn, the grape is the one that gets hurt. So STAY AWAY from college boys.’ The story usually sent me into peals of laughter, but that day the thought of soft fruits and sharp objects terrified me.Post that, there have been no romantic adventures so far and we have reached Class 2 without any need for major hysterics on my part. But I’m slowly beginning to wonder if mixed-sex education is the solution to the world’s ills that I had imagined it to be.

Studies show that co-education makes children conform to gender stereotypes — in the UK, for instance, girls in same-sex schools did better in Maths and Science, just as boys in same-sex schools did better in Languages. I personally feel that same-sex schools allow you to grow up without being sexualised too early.

We live in fairly frenzied times. The films and adverts our kids see are full of highly sexualised images of picture-perfect girls and women. Even on children’s channels, ads talk about milky, age-defying skin and tangle-free hair. I fear — perhaps without reason — that when you grow up in a co-ed, there’s going to be the added peer pressure of always appearing attractive to the opposite sex. Can you be yourself, gender-unstereotyped and, perhaps, un-cool?

Once when my daughter complained about a boy hitting her in class, I told her that I went to a school with no boys in it. Her eyes widened. ‘Reallllly??’ she squealed, ‘But WHY?’ Umm. Just. Then I asked her if she’d like to go to a school with only girls in it. Wouldn’t it be nice? No, she shook her head vehemently. ‘Boys are fun. Only girls would be boring.’ Interestingly, many studies show that overall, children in co-eds are under a lot less stress than their counterparts in same-sex schools. That must explain the ‘fun’ bit!

Less stress for the kids, no doubt, but probably much more for the parents! I know what I’m going to do for the next 10 years: sit in a corner, close my eyes and hold

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

December. That time of the year when my little daughter’s sense of magic fights with her awareness of the real world – and loses. She comes from two generations of fairly laidback, irreligious, non-ritual-practicing people on both sides of the family, and is probably hard-wired to grow into a non-believer.

But all children need some magic in their lives. And by magic I mean that basic human urge to try and explain natural phenomena. Life. Death. How people were made. How the sun and moon were born. Or why cutting onions makes you cry. This need to explain – to basically create a beginning and an end for ourselves and our experiences – is a very human one. And perhaps it is the fount of all religious thought.

Both the thinner half and I had fairly non-religious childhoods. Our irrational cravings, therefore, are those inspired by the popular culture of our youth. Thanks to Linda Goodman, I can’t begin my day without reading my horoscope in three newspapers. The man saw E.T. in his childhood (an experience he is unlikely to let me forget) and probably because of that believes firmly in life on other planets.

But religion and ritual do offer great comfort. Ursula LeGuin nailed it when she wrote, ‘In our loss and fear we crave the acts of religion, the ceremonies that allow us to admit our helplessness, our dependence on the great forces we do not understand.’ When I am calmer, when someone I love isn’t unwell, I’m all scientific and agnostic. But it doesn’t take much to bring on that helpless feeling – a minor fall or an eye infection can terrify me. And then I’ll leap frantically across to the other side, promising coconuts, Saturday temple visits and Hail Marys.

Every now and then, I worry about my daughter not having a framework of belief to reach out to in times of distress. Then I drag her off to the temple. But since I can’t sustain the momentum, it falls slightly flat. She remains curious and watchful, but I can tell there’s very little real, emotional connect.

My mother, who life has badgered into non-belief, worries about this. Don’t ask me why. ‘Your child doesn’t believe in god!’ she says frantically, ‘Do something!’ I try not to remind her that she was the one who told the girl, at 4 years of age, that god didn’t exist, that temples and churches were just full of statues and pictures. At that time, my 26-year-old brother had just met with a fatal accident, leaving us hurt and bitter. It’s hard to always watch what you’re teaching a child.

When my kid lost her first tooth, I suggested the tooth fairy. She laughed at me. So I threw away all subsequent teeth. A year later, her friend lost her first tooth and got a gift from the tooth fairy. ‘There’s no such thing as the tooth fairy,’ mine declaimed. ‘I’ve lost so many teeth and never got a gift!’ The friend replied, ‘That’s because you don’t believe in the fairy!’

And that’s how she learnt, at 6, that sometimes it just pays to suspend disbelief, and hold out your hand. So the next tooth was saved, and the tooth fairy visited us. But Doubting Thomasina re-surfaced. Our long, hair-splitting discussions always ended with me saying helplessly, ‘Well, yes, she doesn’t exist, but if you want, you can think she does. And anyway, you got a gift, na?!’ Like my friend Hansa says, finally, chances are the only deity she'll believe in will be the tooth fairy!

Now it’s Christmas again, that time of the year when

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Add a tag

For years now, Ramesh has had my loyal custom. Back in the '80s, when I first spotted him outside Ambedkar Udyan, I was a humongously fat teenager, and he was a really thin young man in his 20s. He had strangely 'new' looking books. Unlike most street book sellers, he wasn't selling used books. His were all new, all titles that would - for sure - excite my young reluctant reader of a brother. I didn't know then that what he was doing then was selling the West's inventoried books - or books that are 'remaindered' in the warehouses, and are later auctioned off to distributors. Everyone has a favourite book guy. In Chembur, Ramesh happens to be mine.

So The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, Isaac Asimov's Futuredays (it had lovely cigarette card representations of what people in fin de siecle France - 1899 - thought life held in store for the world in 2000; each card was wondrously illustrated and juxtaposed with a brief discussion by Asimov. The best part - it had me panting with excitement - was how he found the set of cards in a toy shop in Paris); the book of the movie Young Sherlock Holmes; and many more that I've forgotten about.

Cut to 2001, Chakala, deep dark Andheri East, walking around with Amit. I'm a lot less humungous, and we are crawling the lanes of our new-found suburb, trying to find something other than shops full of Chinese-made figurines to stare at. I see a book seller with books like The Animal of Farthing Wood and a series that has English being taught using Asterix comics. Delighted I look up at the seller, and whatdjaknow. It's Ramesh, plumper, older. We both grin and laugh and get down to the business of books.

2004, Chembur, and there's Ramesh again suddenly at his usual spot near Ambedkar Udyan. We buy tons of books form him, and finally, give him lots of our pulp crime novels. We find copies of Hoot with him, and colouring books, and more novels, and more vintage children's books. Last week was a bonanza though. Look at all that he had for us! The Keeping Quilt by Patricia Polacco, the story of a Russian migrant whose mother and extended family make a quilt using old clothes belonging to relatives.

The Keeping Quilt by Patricia Polacco, the story of a Russian migrant whose mother and extended family make a quilt using old clothes belonging to relatives.

The quilt sees many generations of her family thru many

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: DNA, small blunders, Add a tag

As a parent, there’s just one thing I’m totally certain of: no matter what you do, you’re wrong. You’re either too strict, or too lenient, or too nice or too nasty, too loving or too emotionally reserved.There’s more good news: you’ll only realise the complete error of your ways about 15 years from now, when you look back with hindsight, and see all the things you did that you shouldn’t have. Don’t ask me to prove this — I just know it the way a flower knows when to bloom, or the way we know that every year, come monsoon, Mumbai’s roads will feel like the surface of the moon.

You always start off with the hope of becoming your ideal of the best-ever parent — the best-pal parent, the pushiest parent, the most-free-spirited parent, etc. I aspired to be a combination of the parents I had plus the sort of parents I wished I had. After seven years of trying, I can freely admit to absolute, humbling failure. I had a wonderful role model in my mother, but turns out I’ve all her few faults and none of her virtues.

One of the things I know I’d love to give my child is the sense of freedom that my mum instinctively gave me. The feeling of total acceptance was the best thing about growing up in my family. I don’t remember mum ever laying down the rules or yelling at us (though her mother — my grandmum — more than made up for that).

But growing up with very few rules unfortunately leaves you unequipped for the harsher realities of life and work. So my totally inspired and unique plan was to raise my child with all the love and freedom my mum gave, plus a sense of discipline.

It didn’t quite work out. Turns out that I have my grandmother’s hissy tongue and temper, and her need for discipline, plus my own inherent laziness and indiscipline. And while I refuse to push my kid hard to succeed, I don’t have my mum’s true sense of laissez-faire either. I do however have her high levels of maternal anxiety. As Himesh Reshammiya once said: It’s Complicated.

As parents are we very different from our own? I think we spoil our kids more — we are wealthier, busier, and it’s easier to buy toys than to give kids time. In 15 or 20 years this will come back and bite us on our butts for sure. Unlike us, our parents were also a lot more secure about their methods. Whether they were beating us up or spoiling us silly, they did it with the firm conviction that they knew what was best for us. Or maybe it just seems that way now.Perhaps each generation of parents has to re-learn the skills of passing on the rules of living.

Sometimes parents succeed and raise happy, well-adjusted people, and others, well, don’t. I remember reading Philip Larkin’s (1922-1985) poem This Be the Verse, and going saucer-eyed at the eff word in it. I didn’t get it then, but now, with more perspective on what it is like to be both a parent and a child, I do.

In three very tight stanzas, Larkin spells out his bitterness:

They **** you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

The poem becomes kinder towards parents in the second stanza — after all, he writes, they were screwed up by their parents too. The solution? Stop having kids and deepening the ‘coastal shelf’ of misery. Larkin’s advice doesn’t work because nature’s urge to multiply is — thankfully — stronger than good poetry.

Sometimes I think the greatest lesson we can teach our children is how to be kind - so that when they grow up, they can look back at our mistakes with a large measure of forgiveness!

(This article appeared in the DNA of Sunday, Oct 2, 2011, in my column called 'Small Blunders'.)

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Shinibali Siagal, Gijubhai Badheka, Timeout, Add a tag

Found in Translation

Found in Translation

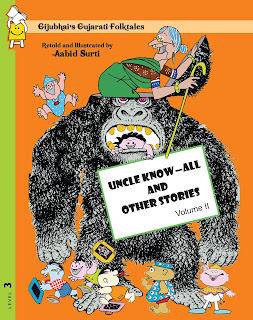

What kind of stories do children find appealing? Strong narratives, arresting visuals and irreverent ideas are crucial, according to children’s writer Anita Vachharajani. Gijubhai Badheka’s Gujarati folk tales not only meet these criteria, but like most folk tales, are also a combination of the absurd, the philosophical and the fun. A contemporary of Mahatma Gandhi, Badheka wrote a variety of children’s stories, which were later retold and illustrated in Hindi by author, painter and cartoonist Aabid Surti. Associated with children’s publishing since 1998 and author of children’s books Amazing India and Nonie’s Magic Quilt, Vachharajani has translated Badheka’s folk tales into English that include a set of two books titled The Phoo-Phoo Baba and other Stories (Volume I) and Uncle Know-All and other Stories (Volume II). She has used both Badheka’s and Surti’s texts for the English version. In an e-mail interview, Vachharajani tells Shinibali Mitra Saigal that folk tales show kids how “sense and nonsense can be tossed together for fun.”

What prompted you to translate Gijubhai’s Gujarati folk tales?

My husband Amit is a Gujarati, and he introduced me to these folk tales. Gijubhai was an educationist who propagated freedom and love as being central to the process of learning. I translated some of Gijubhai’s nonsense verse for The Tenth Rasa: The Penguin Book of Indian Nonsense Verse, edited by Michael Heyman. Later, the editors at Pratham Books asked me to translate Aabid Surti’s Hindi re-tellings of Gijubhai’s stories. I worked with both the Gujarati and the Hindi texts.

Which was your favourite Gijubhai story in the collection and why did you like it? Each one was a discovery. The one I had the most fun with was Uncle Know-All. It's about an old know-it-all who lords over a village of fools and the bizarre nuggets of wisdom he doles out. It had a really weird and completely irreverent feel .

What is more difficult? Writing an original story or translating one? Both are challenging. When one translates, one has to make sure that the text lives and sparkles in the target language as well. In an original story, you can take the narrative where you want to, whereas in a translation, your path is more or less decided for you. Your job is to make that path as rich and joyous as possible.

Can you always retain the subtle nuances of the original? You do lose some nuances. It’s inevitable. But you aim to capture the spirit of the original, without becoming heavy or pedantic. Also, even as you lose one set of nuances, you create others. Since I had both the Hindi and the Gujarati texts to work with, I could see that each version was slightly different. It’s an intuitive process and every re-teller of a story – especially in the folk tradition – makes choices and decisions to suit his or her style. Gijubhai himself was re-telling some of these stories, and you can sense that the language – informal, chatty – is entirely his own.

Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: DNA, parenting column, dna small blunders getting kids to read, Having friends, Add a tag

My daughter has it easier - freelance, stay-at-home parents; a choice of wildly similar cartoons and reality shows on TV; and apparently, a liberal academic system. What does she lack that I had? I guess the answer is friends. Friends who live nearby and are just one loud, afternoon-nap-ruining yell away. We had this growing up - friends who were always ready for play, fights, trips to the corner shop and sharing comics.

Now we live in a neighbourhood of low-rises, where all the young people have left, following jobs that take them to where other young couples - and their kids - are. We live among retirees and are indisputably the only people of child-bearing age around. Our kid, therefore, has no playmates.

In fact, our neighbourhood is so kid-free that BMC’s Pulse Polio staff took a long time to figure out that we existed and needed reminders and booster doses. This may make no sense to the un-kidded among you, but those with kids know that the Pulse Polio people are the most dedicated sniffer-outers of children under five. It took them time to find us, and that is saying a lot. When they found us, they shook their heads in wonder and said, ‘Kisko maloom tha ki iss building mein bhi bachche hai...’

So we started taking baby to the garden. The few kids who turned up there were a floating population. The only permanent people were the grannies, and though our child loved playing with the arthritic old ladies, it was obvious that she needed peers.

Young couples with kids automatically seem to gravitate towards the newer gated complexes, and since we couldn’t move to one of those, playdates seemed like a solution. But fixing up ‘appointments’ for toddlers is an insanely awkward and pointless exercise. Firstly, it’s not like you’re walking into the neighbour’s place for a game of ‘house-house’. So it’s not casual. The moms and dads have to like and ‘approve of’ each other. Then schedules have to be discussed and tweaked. It all begins to feel way too strained, artificial, and too much like work.

What I wanted was for my kid to have a village of her own. A set of friends to play, fight and gossip with every day. Children need to build relationships outside the comfort zone of families, so that they understand the dynamics of social intercourse. This knowledge is so important that most tribal societies have formal spaces like youth dormitories and age-sets to foster it.

Just when I was about to give up hope, I met an old schoolmate in the garden, who generously said, “Come play in our building, there are many kids.” So I located her building, about eight streets away from us, full of young people, their kids, and their friends’ kids. A small oasis of 25 children! Presto, my daughter had her village, albeit a bit further from home th

an I liked.

an I liked.At first, playing with peers was difficult for her. So far her playmates had been obliging adults. Children are instinctively not polite or obliging to one another - with them, you have to, like in the jungle, earn your stripes. So every evening would end in a fight and her howling loudly, and y

View Next 25 Posts

A lovely read, as always, Ani!!

A lovely read as always Ani!

thanks, ashish! (for some reason google trying to sign me in as 'unknown' :)) ani

I could say picture Omana valliamma through all this.. N had such a small role but what a stellar discovery..In our house, it is Achcha who comes up with the analysis while Mom tries to not burst our bubble when we proudly show off some part of the city! And the horror over the food bills we love to foot..ohhhh I know that so well:) Loved this piece..

ah deepthy, i think food bills are more justified in moms mind than ridiculous bbay coffee prices! but i hear you :)

Lovely piece, Anita. Thoroughly enjoyed it.