new posts in all blogs

Viewing Blog: Anita and Amit Vachharajani, Most Recent at Top

Results 26 - 50 of 111

Books, babies, life, and everything in between!

Statistics for Anita and Amit Vachharajani

Number of Readers that added this blog to their MyJacketFlap: 1

In the six-odd years that I have been chaperoning my kid to birthday parties, I’ve figured that party-wise, there are broadly two kinds of city parents: those who approach their kids’ birthday parties with the same determination that soldier-ants take to gathering food, and those who, like the grasshopper in the folktale, simply outsource the stress.

The soldier-ant-type of parent (mostly the mother) frets, plans and slogs for the birthday party, tearing out her hair and getting irritable bowel syndrome in the process. Fathers are usually assistant-sloggers, perfect for random running around and sacrificing their pollution-weakened lungs to blow balloons.

The grasshopper-type parent, meanwhile, hands it all over to a new breed of professional — the event manager. Mum and dad make phone calls, sign a few cheques, and go for a film or a pedicure. The event manager gets everything from food and ‘games’ to return gifts.

Article continues below the advertisement...

It’s weird, but both the grasshoppers and the soldier-ants take pride in their distinct parties. Stoically, the soldiers flaunt their small, home-made, parent-driven parties. The grasshoppers meanwhile take pride in the fact that their kids’ birthdays are large-scale, ‘exciting’ and more importantly, managed by the hired help. I’d like to state here that I’m a soldier-ant-mum, and I have my husband’s fatigued lungs to prove it.

Growing up in the ’70s, for us a birthday party meant paper plates, chips, a sandwich and a slice of lurid-looking cake. It meant money in an envelope pressed into the birthday kid’s hand. It meant some noise, some Rasna, and ok-tata-bye-bye. But in the Noughties, in globalised India, if it doesn’t hurt the wallet, it’s not just worth it.

Five parties out of the 10 we attend have one or more of the following:

- a bouncy castle which teeters close to the sky and looks downright scary

- glittery, eco-unfriendly, thermocol banners featuring sundry Disney Princesses/Spiderman/Ben 10 ‘cartoons’ which are supposed to define the party’s theme

- a young college student with an accent straight out of an Andheri East call centre as the Master of Ceremonies — my daughter calls this person ‘the manager’

- rehearsed performances by the birthday kid’s older sisters/cousins, featuring highly-sexualised Bollywood numbers — you cringe, but since the parents look like their child has just ended world hunger, you nod and say, ‘Verrrry nice…’

- a magic show (with frightened rabbits/doves) + a tattoo artist + a caricaturist + a hair braider-and-colourer (horrible chemical colours on your child’s head, but never mind)

- games that make your toes curl. Like ‘pick the dad with the biggest paunch’ or asking the birthday kid’s father to choose the best dancer among the assembled mummies, who obligingly shimmy for him

Recently, at a 4-year-old boy’s birthday party, after the professional clowns had romped on the stage, we were in for a hitherto unseen treat. The ‘manager’ invited the headmaster of the child’s playschool to ‘say a few words a

written in 2001, the idea for this story was suggested by amit. then he worked with me to whet it, and later gouri worked on it a lot (special, special thanks for her editorial genius and patience). i sent it to puffin, where sayoni basu at puffin liked it, and though they didn't publish it finally, sayoni pulled me into a lot of fun projects - like the puffin book of bedtime stories, and the tenth rasa.

ambili is a much-travelled story, and finally, she found her form and her book at pratham, where manisha chaudhary was kind enough to choose to publish her! venkat raman singh shyam drew and painted her, in his lovely, restful style... so here she is, in her own story, ambili meets the king!

i love that the idea came from a gujju, was written by a mallu, illustrated by a pardhan gond artist from madhya pradesh...

giju bhai again, is someone i met thru amit and we worked with his folk nonsense in the tenth rasa too. after translating poetry for the tenth rasa, i really wanted to try some prose. then i met sampurna murti of pratham, and turns out they were thinking of translating giju bhai's stories - thru a hindi re-telling of them illustrated by aabid surti.

it was an exciting project, as i worked with both versions - aabid bhai's and giju bhai's. during this project, amit also chanced upon the gujarati giju bhai version he had read as a child, illustrated by aabid bhai!

so here the two volumes are, full of some of the nicest, cheeriest folk stories. and filled with aabid bhai's funny drawings. hope you find them near you people, or else look up their site. you could order online or find a store near you using their store locator.

The eagles who soar through the sky are at restAnd the creatures who crawl, run and creep.I know you’re not thirsty. That’s bull***t. Stop lying.Lie the **** down, my darling, and sleep… Not my lines, but lord, I wish they were. Novelist Adam Mansbach, exhausted with his daughter Vivien’s refusal to sleep, wrote the hilarious, cathartic poem Go the **** to Sleep. While its gentle rhymes and brilliant illustrations (by Ricardo Cortés) make it look like a picture book, it is definitely not to be read to your child. Not unless you want her to grow up with the vocabulary of a truck driver. Because this best-selling ‘children’s book for adults’ is about a father swearing at his child’s reluctance to fall asleep.I can see your raised eyebrows from here. The thing is, till you have tried to put a reluctant child to sleep, you have NO IDEA how tough it can be. Most young parents learn — the hard, humbling way — that kids have their own body clocks. In two years or so you recognise this, and officially give up hope. You may have dinner plates to wash or a cure for cancer to invent or your limbs may be falling off from sheer exhaustion. But baby won’t fall asleep till he wants to. There are still so many toes and fingers to play with, and so much of your hair to pull. It’s enough to make you want a village to raise your child with!

Not my lines, but lord, I wish they were. Novelist Adam Mansbach, exhausted with his daughter Vivien’s refusal to sleep, wrote the hilarious, cathartic poem Go the **** to Sleep. While its gentle rhymes and brilliant illustrations (by Ricardo Cortés) make it look like a picture book, it is definitely not to be read to your child. Not unless you want her to grow up with the vocabulary of a truck driver. Because this best-selling ‘children’s book for adults’ is about a father swearing at his child’s reluctance to fall asleep.I can see your raised eyebrows from here. The thing is, till you have tried to put a reluctant child to sleep, you have NO IDEA how tough it can be. Most young parents learn — the hard, humbling way — that kids have their own body clocks. In two years or so you recognise this, and officially give up hope. You may have dinner plates to wash or a cure for cancer to invent or your limbs may be falling off from sheer exhaustion. But baby won’t fall asleep till he wants to. There are still so many toes and fingers to play with, and so much of your hair to pull. It’s enough to make you want a village to raise your child with! Sleep patterns vary. Some kids sleep at 8pm and wake up shiny-faced at 6am. Some young debauches bounce off the walls till 12am and then crash, only to come around at about 10am the next day. Mine sleeps late and wakes up early. At 11.45 in the night, when my eyelids droop shut in the middle of some story she is telling me, she pulls them apart so that I can listen to her more attentively. At an obscene 6.45am, she’s up again (only on holidays) having remembered some crucial detail she forgot last night.

Sleep patterns vary. Some kids sleep at 8pm and wake up shiny-faced at 6am. Some young debauches bounce off the walls till 12am and then crash, only to come around at about 10am the next day. Mine sleeps late and wakes up early. At 11.45 in the night, when my eyelids droop shut in the middle of some story she is telling me, she pulls them apart so that I can listen to her more attentively. At an obscene 6.45am, she’s up again (only on holidays) having remembered some crucial detail she forgot last night. I have realised that sleep deprivation is a fairly refined device of torture. A friend’s mother who had two kids in quick succession spent the next few years waking up at night for this one’s feeds and that one’s pee. She thought she would never ever sleep again, that her life would pass by in a miasma of tired un-sleptness. The frustrated sense that Mansbach calls ‘…being in a room with a kid and feeling like you may actually never leave that room again...’ Imagine, then, having twins or triplets.As kids grow, their exploration of the day’s stimulus becomes more verbal. My kid isn’t obsessed with her toes now; she has questions. How did cavemen have babies — there were no doctors to cut their tummies open? Why we have skin? Why are kids mean i

I have realised that sleep deprivation is a fairly refined device of torture. A friend’s mother who had two kids in quick succession spent the next few years waking up at night for this one’s feeds and that one’s pee. She thought she would never ever sleep again, that her life would pass by in a miasma of tired un-sleptness. The frustrated sense that Mansbach calls ‘…being in a room with a kid and feeling like you may actually never leave that room again...’ Imagine, then, having twins or triplets.As kids grow, their exploration of the day’s stimulus becomes more verbal. My kid isn’t obsessed with her toes now; she has questions. How did cavemen have babies — there were no doctors to cut their tummies open? Why we have skin? Why are kids mean i

We took part in Zoe Toft's International Postcard Swap this year. It was a way to get n excited about her drawing and her copious reading - as this vacation had us pretty sadly under-engaged, what with her chicken pox and my bad back. She drew about 7 really lovely postcards (including the potatoe monster who eats dishes above) and had great fun choosing from among her books, and then re-reading all her favourite - and sometimes forgotten - books.

So this was our list:

Ten Apples Up on Top by Dr Seuss, illustrated by Roy McKie. An elegant and hilarious read. N has long given up on picture books and beginner readers, but every now and then, she sneaks back to them, looking inside for fun, i guess.  we found this one in pondi, and i was going to gift it away till i caught her reading and re-reading it, and chortling away. when we talking about recommending books, this was one of her first.

we found this one in pondi, and i was going to gift it away till i caught her reading and re-reading it, and chortling away. when we talking about recommending books, this was one of her first.

The Grey Lady and the Strawberry Snatcher by Molly Bang. another total favourite of n's. just loves loves loves this wordless books, even going back to it repeatedly.

The BFG by Roald Dahl. Her first proper big novel. Finished all 200 pages of it last month, using a bookmark and feeling extremely serious. loves it to madness, esp the bits about how people from different parts of the world taste different! ('people from india taste of ink!')

Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise brown - a long forgotten read, but had to be pulled out because we got a 2-yr-old and a 3-yr-old in our list. but a very sweet, calming read, and used to be our bedtime story

Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise brown - a long forgotten read, but had to be pulled out because we got a 2-yr-old and a 3-yr-old in our list. but a very sweet, calming read, and used to be our bedtime story

If you marry someone from another ethnic group in India, two things could happen. Either your parents never talk to you again, or, if they are nice, normal people, they mutter hopeful homilies like, ‘Children of inter-caste-marriages are always very clever…’ Luckily, it’s a while before you learn about the realities of living with differences. As a Malayalee married to a Gujarati, I could tell you a bit about this.

Finally, it all comes down to food and drink. Mallus believe that drinking hot water boiled with jeera, dhania or sunth in summer actually cools the body down. I never drank ice-cold, fridge-water at home, growing up. Once, around 5, I mistook a small bottle of white vinegar for water, grabbed it and drank deep before anyone could stop me. If they saw me, they'd take away the bottle, I knew. My lips turned blue, mom says, but I refused to let go of that bottle. Somehow, in Kerala, anyone wanting to drink ice-cold-water is morally weak and just asking for a sore throat. For the first year of our marriage, the fridge was a silent war zone. He would put in bottles of water, I would take them out. It seemed wrong somehow, to be serving cold water at home. I mean, whatever next? My mum still doesn’t get why her son-in-law blanches at the Malayalee summer cooler: hot, pale-yellow, jeera-infused water.

Perhaps it’s because he’s from Kathiawad, where drinking cold water feels like a minor religious experience. In summer, my mother-in-law freezes vatis of boiled water and then tosses the little bowls of ice into a large vessel of boiled-and-cooled water. Guiltily, I drink glassfuls, while looking around furtively for a yelling adult. The fridge wars have ceased.

Likewise, breakfast in a Mallu house is serious business, with idli, dosha, upma or appam. In a Gujju house, breakfast is the time you kill, munching homemade naasta before a delicious hing-and-gur-tinged lunch. When the sun sets, you want to eat light, and it’s time for a ‘prograam’. A bhel, bhajiya, dhokla or paani-puri no prograam. I watched awe-struck as the elderly polished off fried snacks for dinner. If I gave a Mallu father-in-law bhajiyas for a meal, he’d go nuclear on me. Diabetes! Acidity! Filial brutality! Stuffing my face, I worried about being able to conjure up similar whatnots when the in-laws visited us in Mumbai. Obviously, a square meal just wouldn’t do.

Then there are the specific food-group-related hysterias. Featuring — in our case — rice and proteins. We Mallus like our proteins caught, killed, cooked in kilos of cokennut and served with red rice. To most Gujjus, proteins = dals, which are eaten with rotlis, and not with rice (simply too starchy, no? Not healthy - say the people who mainline deep-frieds).

We found all of it hilarious — till baby arrived. Then the battles-lines were drawn. Rice versus wheat. Oil baths versus just baths. Ragi versus rava. Dal-paani versus rice-kanji. Green bananas versus yellow bananas. Picking-a-name-off-the-top-of-your-head versus naming by rashi. Rubbing a stick made of scented herbs with a bit of gold inside it and giving the baby a drop of the paste (Mallu colic cure) versus fainting at the suggestion (Gujju reaction).

And food-group hysteria again. My mother-in-law implored, ‘Dal is the best protein, no need for non-veg!' And then, seeing I was determined to raise an omnivore, the poor lady got to her specific fear. 'At least don’t give her pig-meat!’ My mother, meanwhile, felt duty bound to enquire, ‘Why haven’t you started fish-chicken for this child still?’ Meanwhile, the fruit of my womb calmly refused Mallu staples like chicken, fish, steamed yellow bananas, jackfruit and rice kanji. She seemed predisposed to sev-gaanthiya, pasta, paneer, pijja, noodles, and still needs her daily Gujju staple: dal-bhaat-shaak-rotli.

Growing older makes you hanker for the ways of your childhood. It makes you want to reclaim some of the past, by teaching your

Described as the Best British Children’s Literature Blog by the School Library Journal, a pre-eminent online magazine for American Libraries, Playingbythebook.net is written by Zoe Toft. The 37-year-old mother from the UK is a trained linguist and a self-confessed lover of dictionaries. She reviews picture books with her children, and, interestingly, builds each review around an activity inspired by the book. For instance, when Toft reviewed my book, Nonie’s Magic Quilt, she merged it with a description of making a quilt for her daughter.

In 2010, Toft had an unusual idea. “We love receiving ‘proper’ mail, and wanted to participate in an online postcard swap,” she says. “There were many swaps, but none that the kids could enjoy. So I thought up a swap where every postcard would include a children’s book recommendation, because sharing a favourite book is a concrete way of making a connection. I hope to hold the swap every year. I don’t want to make the world any smaller, but I think it’s important we feel connected to each other.”

The swap is structured so that each family sends postcards to five families across the world. In turn, they receive postcards from five different families (not the same ones that they sent postcards to). The postcard can be printed or drawn, with a note recommending a favourite book. Effectively, the families find a window into each other’s lives, and share about 10 book suggestions among them. Toft says, “You can suggest the same book to all the families or – ideally – a different book to each. People often tailor their suggestions keeping in mind the recipient’s age.”

Toft’s first postcard swap in 2010 brought together over 250 families from far-flung places: Alaska, Argentina, Brunei, Bulgaria, Israel, Marshall Islands, Pakistan and Poland. “The toughest part is pairing up people, making sure everyone receives families from five different countries, with children of similar ages. The reward is hearing about the little connections they make. People who come back every year will be paired with different families.” After the 2010 swap, many families went on to become penpals.

During the swap, Toft “met” many people, including Sandhya L., a Bangalore-based writer for Saffrontree.org. Sandhya’s family sent cards to the UK, US, Singapore and Spain. Her daughter “was delighted to receive letters addressed to her. One came from the Republic of the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean! In these days of instant communication, it was exciting to get post.”

Another new friend was homeschooling mom Bronwyn Lavery of Christchurch, New Zealand. Lavery says, “I set up a world map, marking the locations of families we connected with. I told my kids about the great distance each card would travel. We loved sharing our favourite books and searched for books that others recommended.”

And connections had indeed been made. When Christchurch had a 6.3-magnitude earthquake in April 2011, Toft got in touch with Lavery and heard that many families had lost their homes. Together, they paired families around the world with those in Christchurch, and, “Thanks to the kindness of strangers, we sent 565 books into welfare centres and care packages as well, so that the families would have something to enjoy as they rebuilt their lives.”

Click here to find out more about the International Postcard Swap for Families. Or email [email protected]. The last date to register is May 17.

A shorter version of this article appeared in The Mint of Friday, May 6, 2011, to see it on the page, click here: http://www.livemint.com/2011/05/05220037/Drop-me-a-postcard.html?h=C

In the long-forgotten past, I worked in a publishing house. With actual adults, politics, a cafeteria, and real gossip. But before I start weeping at those fond memories, let me move on to the one that inspired this article. Colouring books. Full of perfect, pre-drawn pictures, colouring books were our main money-spinners, and their status as such was sacrosanct.

Once, feeling a bit wild — or unwell maybe — I suggested doing an open-ended sort of art-and-activity book for children. Not the kind where the kid colours a smiling mouse, but one where she is encouraged to apply her mind as well. So you have, say, a tiger with a thought bubble, and the child has to figure out — and doodle — what the tiger might want to eat. Shooting Nazar-suraksha-kavach-type rays of condescension my way, the boss said, ‘Why parents buy activity and colouring books? So that children will do timepass. Not so that children will ask them what to draw.’ Point noted. I shut my gob.

Ten years later, working with kids has shown me that art can and should be seen only as a method of self-expression in children. Any adult intervention should be at the level of acting as a facilitator or trigger — and nothing more. To take joy in colours and explore materials should be the primary focus, rather than acquiring the ‘skills’ associated with making perfect pictures. Skill-based art classes — madly popular right now — teach kids 4 to 6-years-old how to draw and colour ‘well’. They come out making pretty pictures no doubt, but their natural and delightful uninhibitedness is pretty much ironed out of them.

Article continues below the advertisement...

Try saying the words ‘colouring books’ to my otherwise mild-mannered-artist husband, and he will break into a taandav and rip your head off. These seemingly-innocent books — or the spawn of Satan as he calls them — meet two key parental desires: perfection in the child’s ‘performance’, and secondly, quiet engagement, or ‘timepass’. Like the classes, they leave no room for open-endedness, imagination and self-expression. They also pass on a subtle signal to kids: drawing is grown-up’s work, and should not be attempted by you. You just colour. Neatly and within the lines.

So as a toddler, our kid was only given paper, paints, water and brushes. She messed around like Jackson Pollock on steroids. Skills, her father said, could be taught later. We were entirely smug about this till she returned bawling one day from pre-school. Colouring a printed picture within the lines had her flummoxed. Given colours and paper, she scribbled, rubbed, crushed, had fun. Unlike most kids in her class, she had never seen a colouring book and didn’t know that you couldn’t — at 4 — let your crayons stray.

It took a long time for that particular penny to drop. Colouring within the lines may be an artistically pointless pursuit, but to educationists, colouring with fat crayons is a good way to teach children better finger-control. Sighing at our over-reaction, we quietly went out and bought colouring books. Gradually — with her kind teacher’s help — our child ‘caught up’ with her friends. Humble pie is delicious when the alternative is a teary child.

Now that she’s older, like others her age she draws stuff and builds stories around it. Silly, strange vignettes that probably pop into the head as the hands move (and her artistic tantrums are part of the package too, her friends’ mothers tell me). We’ve also discovered the Japanese artist Taro Gomi’s delightful doodling books. Open-ended and thought-provoking, they don’t just make time pass, they make it fly like Rajnikant on 3G.

It’s cruelly ironic that though we don’t send her to art tuitions, she shamelessly picks up colouring tips like ‘shading’ from the art-tuition-going-kids at school. As an adult she’ll probably write about her kanjoos, oppressive parents who wouldn’t send her to art class at 4 and how deprived she felt

When I tell people that I write children’s books they usually imagine that I am:

1.As rich as Croesus from all the royalties my kindly publishers send me.

2.If not, then at least as rich as J K Rowling. I mean, at least.

3.If not rich, then surely living in a world full of sweet peppermint twists, where unicorns of joy regularly gambol at my feet.

Article continues below the advertisement...

It’s fun to disabuse people of these charming notions.

They blanch on hearing about some of the ogres in publishing, and when I tell the average Shining Indian Yuppie how much children’s writing actually pays, the silence is deafening.

There’s a fourth notion that some people — mostly mums with streaked hair and big bags — have about people who write books for children. This is the one where they imagine that writers must know enough practical magic to be able to whiz a video-game-and-mall-obsessed child into an avid reader — overnight, at the age of say 9 or 10 years. Easily done, no? Well, er, no.

When parents tell me ‘My kid doesn’t read, what to do?’ I usually ask them if they read. Some laugh out aloud at the quaint notion of themselves as readers, while others look thoughtful and ask if I meant Chicken Soup for the Parent’s Soul. When I say ‘No,’ they reply cheerfully, ‘Then no, I don’t read. But I’d reeeallly like my kid to read!’

So I explain that to inspire their kids to read, they need to get excited about reading themselves. They look shattered. Obviously I should have said something sensible like ‘Soak three newspapers overnight, blend and pour into a purple glass and then pour into your child’s mouth while holding his nose shut and praying to the sun. You can be sure that he will begin reading on the sixth day!’

Unfortunately, human beings are essentially apes, and we learn by imitation. Little apes watch grown-up apes to figure out what is edible and what is not, what is to be loved and what is not. So if parents value shopping, video games and trips to the mall above all other activities, chances are their kids will too. If parents love football and hiking, chances are their kids will too. And typically, if parents read, chances are, their kids will read too.

I personally worry that reading too much makes kids introverted. Sometimes I feel it lets them get their life-experiences second-hand. But that’s probably because my kid reads. I would rather she were sporty and physical, but she has grown up watching her mother read while lounging around, cooking, eating, and even while trying to fall asleep. Father is same-to-same, with the added feature that he also reads on the pot. It would be pointless for me to despair at the fact that she doesn’t run or swim fantastically well, and regards the act of climbing trees with suspicion. But she reads everything, everywhere — all sorts of books, in the car and on the pot. Apples have this nasty habit of falling close to their trees.

So yes, mums-and-dads, the only thing that will get your kid excited about books is you getting excited about them. If you don’t read but genuinely want your kid to, here are some suggestions: buy interesting, age-appropriate books, and read them out to your child. If he or she is too young to get the ‘reading’, then tell the tale. Dramatically, with a sense of fun. While keeping a watch out for signs of engagement and/or boredom. Talk about books, spend money on buying them (yes, that is key) — you could, like us, also trawl through secondhand stores. While your jaw might lock with boredom, chances are your kid might get into a reading habit.

And who knows, maybe it’ll make a happy reader out of you too!

(this article first appeared in the DNA of Mar 27, 2011)

Amy Chua’s Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, which I reviewed for this paper some weeks back, is causing a sharp intake of breath among educationists everywhere. The book is about her life as a hysterical over-ambitious parent, and what disturbed me, personally, is that she is not the only one out there.

Whether it’s Ms Chua in America, or Mrs Rao in Matunga, pushing kids to ‘reach their potential’ begins much earlier these days. Moms I meet at school look at me like I just crawled in from under a particularly grimy rock when I tell them that my 6-year-old has only just begun to learn basketball and music. I can see their antennae quivering: Neglectful Mom Alert!

One lady has been ‘showing’ her kid books of maths tables from the time he was 3; put him in Abacus classes by 4; ‘piano’ or keyboard classes (yes, it’s not just the humble ‘Casio’ anymore) by 4.5; and of course, chess by 5. Another, the mom of a 7-year-old musically gifted child, takes him for Hindustani, Carnatic, and ‘piano’ classes on alternative days, after he’s done seven hours at school. Being excessively liberal, she says, ‘If he finds it too much, I have told him to tell me.’ Yeah, right. See, kids live to please the adults in their lives. Practically everything is acceptable because they don’t know of alternatives. That’s why we, as parents, need to calm the heck down.

Among the favoured classes these days are ‘phonetics’ (doesn’t matter that the term is wrongly used), grammar, tuition, dance, music, Abacus, Vedic Maths, story-telling, creativity, taekwondo and chess. Having shoved their clueless kids into strangers’ homes, mummies enjoy a bit of that precious commodity – free time. And they’ve earned it by paying to have their kids ‘build their potential’ and ‘increase their confidence’, no? It doesn’t matter that being pressurized to do too much early in life can actually lead to anxiety and diffidence in kids.

Increasingly, psychologists tell us that unstructured time – when children hang about with friends or figure out ways to engage themselves – is important. Between school hours and various classes, what about this generation’s unstructured time? Most of us grew up with time which we were allowed to cheerfully waste. Turns out, that ‘wasted’ time – when we could do what we liked – is actually an important tool to de-stress and to build creativity.

The real risk with parents who ‘work so hard’ is that they start expecting rewards. If Aryaman doesn’t make the building aunties swoon at a ‘society function’, then why did we send him to all those Hindustani Music classes, yaar? And if he does sweep ’em off their feet, then, you know, how about Indian Idol next? Alarmingly, The Guardian’s Terri Apter notes that over-parented kids often grow up to be ‘compliant and devious’, ‘obsessed with grades and lacking interest in their subjects’.

Every generation gets the sort of writing on education which reflects its beliefs and aspirations. In the last century Maria Montessori, Rabindranath Tagore, Waldorf Steiner, Aurobindo, Gijubhai Badheka and others propagated a humanistic, benevolent approach to learning. The 70s had John Holt, who advocated homeschooling. It would be truly sad but telling if Amy Chua – who slaps and stresses-out her kids – were to write our generation’s educational classic!

A longer and duller version of this article appeared in the DNA of Sunday Mar 6. They printed an earlier version by mistake :( and they also used a different title!

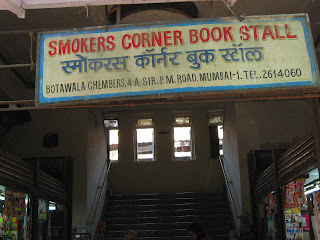

Cities–like the people in them–do not live by bread alone. They need mind and soul food to grow into the vibrant entities that they become. Mumbai has been given its mind food–in the form of stories, novels, pamphlets, athletic rule books, comics and other literary whatnots–by a small band of dedicated bookshops which have been around for 50 years and more. Growing organically with the city, these bookshops have seen it all, and with time, become landmarks in themselves.

A corner of the world

The wonderful, timeless Smoker’s Corner is cleverly laid out in the foyer of Botawala Mansion just outside Ballard Estate, the city’s heritage business district. Suleiman Botawala (76) says, “I bought Smoker’s in 1959 from the original British owners who sold tobacco. Since I loved reading, I slowly changed to books. In those days, P M Road was a two-way street, and it was washed clean regularly.”

There is a clean-cut, spare sort of elegance to the shop, with the display arranged neatly in shelves of lovely, rich teak. A piece of string holds the flap of each book shut – to prevent the covers from getting dog-eared, Botawala explains.

Where are his rarest books, I ask. “All in my house!” he replies with a chuckle. “The moment I spot a rare or unique book, I hold on to it till a customer comes and asks for it. Then I usually gift it to them.” Gift it? Whatever happened to the economics of book selling?

“I’ve sold a lot, and besides, sharing books is the greatest joy in life. Here I’ve met some of the most interesting people in the city and I’ve learned so much from each of them. This is my way of giving back something.” One of his customers in the ’80s, a learned, unassuming man, turned out to be Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. He was then the Governor of the nearby Reserve Bank of India.

Botawala is never in your face, making it a policy ‘not to interfere’ with customers. However, he also knows his regulars’ tastes, and always has a treat saved for them. Knowing my fondness for obscure Russian children’s books, he gets me a stack of his oldest.

Botawala is genuinely delighted by the new books stores. “They will surely click, because reading is popular once again. Only their prices are forbidding.”

He shows me a thick, aged book of quotations called Noble Thoughts in Noble Languages and smiles, “New shops may have a mind-boggling range of best-sellers, but they don’t have real treasures like these!” [Mr Botawala passed away in 2009. His son Zubair now manages the shop.]

Where the price is always right

Just further down the road from Smoker’s, is Strand Book Stall, another treasure-trove. Here they pride themselves on their consistently low pricing. “We keep the thinnest of margins,” says P M Shenvi (60), the ever-smiling manager. “That’s how we sell many books at less than half their prices, and give 20% off on others. Our aim is to be affordable and we curtail all other expenses towards that. No fancy décor for us!” Despite

It’s probably the toughest job in the world, but there’s no training for it. There are no degrees you can get, or papers you could write before they feel you can come on board. Seriously, all it takes to become a parent is the correct set of anatomical parts and a functioning hormonal make-up. And the ‘job’ in concern is a small human being who you have to care for and nurture for the next 20 years. That bit in italics is the scariest thing about parenting.

All you bring to the table, really, are your own emotional baggage and your set of highly idiosyncratic notions on what sort of person your kid should grow up to be. Battle Hymn Of The Tiger Mother is Amy Chua’s description of how she raised her children, bringing her own unique and mildly demented ideas to the process — often, in the face of her American husband Jed Rubenfeld’s quiet anger and disapproval.

A daughter of Chinese immigrants, a professor of law at Yale, and a renowned writer on ethnicity and foreign affairs, Chua is the epitome of the successful, driven, Asian mom. Brought up in the hard, Chinese way, she is determined not to raise her child like Western parents do — with kindness, quick appreciation and indulgence. Much that she sees wrong in the people around her — neuroses, dysfunctional families, entitled kids with no drive or ambition — she attributes to the Western model of parenting, where parents readily accept their children’s under-achievement and laziness. Western parents let children enjoy their childhood; but Chinese parents, she says, prepare children for the future.

She opts to be a ‘Chinese Mother’, which she explains early on, is not a racial identity but a personality type. ‘Chinese Mothers’ are parents who are ambitious for their children and will steamroll their kids’ immediate desires to ensure their future success. Nothing is fun, she says, till you master it. It’s not enough to be ‘good’ at an instrument; you have to be playing at the Carnegie Hall or performing for international audiences to be acceptable.

Chua’s non-acceptance of mediocrity is across-the-board. She rejects the sloppy birthday cards her kids make her because — with her Confucian wisdom — she knows they can do better. The speeches they write for the funeral of their dead paternal grandmother are moving, simply because Chua wouldn’t accept their first ‘Hallmark-card-type’ efforts. Every success is a direct result of her slave-driving.

In Chua’s view, being a hard-to-please parent will ensure that you raise obedient, devoted, focussed kids who excel at classical music, never become neurotic, and best of all, will look after you in your dotage. Well, her older daughter is just 15 or 16 years old, so let’s not start setting off the fireworks of success yet. Will there be a Guess How My Tiger Mother Scarred Me by one of her kids in the future? Let’s wait and see.

Battle Hymn… is engaging because it makes you cringe and laugh at the same time. Chua’s determination to make a genius out of the family’s dog is funny, while her daughter’s stress-induced biting of the piano’s legs, is not. Working within the cruel-to-be-kind school of parenting, she admits that reprimanding her kids is exhausting, heart-wrenching work. So slapping her daughter in Barcelona — for not kicking her fingers high enough while playing the piano — is the price she pays for giving the child the opportunity to play for an audience ‘in a

An old friend from Delhi visited us recently — a really great guy who is stylish in the way that only men from Delhi can be. One evening, I asked him to carry a perfectly good, purple coloured, non-crackly (crucial details) plastic bag. Nothing prepared me for his shocked yelp. “A plastic bag you want me to hold? It crackles and it’s pink! No way! It just won’t go with me.” He shuddered.

I took it back, muttering something like, “Wait-till-you-have-a-kid-bugger.” See, the last six years have changed us. Pista-green candy-striped cloth bags, ugly red-and-yellow umbrellas, Tinkerbell raincoats, sky-blue potty seats and the like have been lugged by us.We have, in many ways, lost our sense of style — and, truly, lost our sense of shame too.

I blame it all on the process of becoming parents. The loss of one’s coolth begins with the woman getting pregnant. As a guy, once your woman’s bump starts to show, and there’s that civilised and public acknowledgement of your sex life by neighbours and parents, you change in crucial ways. Don’t ask me how or why, but it happens. I had fertility issues at one point, and I remember the doctor — a respectable, middle-aged, mom-type — asking us to ‘have relations as many times as possible’ on a particular date. I stared at her for five whole seconds, eyes narrowed, wondering what she was saying. And suddenly I realised that she was asking us to have sex. When we recovered from the acute nails-on-the-wall-feeling induced by her euphemism, we knew that nothing would be the same any more; least of all, the act itself.

As for women — do I really need to elaborate? Somehow, having a child is equivalent to being in a reality show inside a goldfish bowl. Because once you’re pregnant, the human race at large suddenly begins to take an active interest in you. This is probably an atavistic thing, dating back to centuries of being concerned about she-who-bears-life. Apart from being prodded by the doctor and his/her team, the world and its cousin will advise you. The best nugget I got was a vital tip on human anatomy from an elderly Punjabi uncle on my morning walks. He recommended that I eat the ghee-rich ‘panjeeri,’ which would ‘make the insides smooth’ so that the baby ‘comes out easily’. Between incomprehension and shock, there is a small space called parenthood.

Inevitably and slowly, you will relax into the state, wantonly discussing vomiting, acidity and bowel movements with strangers.

I remember that my salwar’s naada used to keep slipping down the parabola of my belly, and I would keep hitching it up. Pull up that naada in full public view often enough and you realise that dignity-wise, it’s all south from here. (Why did I continue wearing falling-naada salwars? Because this was deep, dark 2003, when only aerobics instructors and male dancers wore tights.

Respectable pregnant women were either looking like ducks in frocks, or seahorses in saris, or were wearing ‘punjabi dresses’.)

Once you have the baby, the change is irreversible. You talk about food, poop, milk and breast pumps with a quiet insouciance. You used to be angsty, reserved, cool people. Now you’re loud, hustling parents, who have no qualms asking stern pediatricians daft questions, or doling out free advice to pregnant women and new moms. Yeah, and you stop being so darn particular about things like bags.

Between losing her senses of style, shame and sanity, Anita Vachharajani raises a child and writes children’s books

This article appeared in the DNA of Sunday, Jan 30, 2011

No, frankly, I just pretend to. Really, all I do is answer the doorbell. Answer the doorbell to the cook, who, being trained in the offense-is-the-best-defense school of culinary arts, blasts me immediately for the lack of key ingredients.

Then I answer the doorbell to various couriers — for me, for husband, for neighbour and neighbour’s relative. Answer the doorbell to someone who wants to sell me multiplex coupons. Followed by someone, allegedly from the electric board, who wants to sell me an appliance which will halve my power bills. When the Art of Living guys ring, promising to bring calm into my life, I start foaming at the mouth.

Finally, I plop down on my ‘office’ — the divan in the hall, a parking zone for crayons, earrings, kid’s underpants, notebooks and novels, left-over food and teacups. When you work from home, ‘official’ space and time are ill-defined. Inexplicably, you end up working longer hours and getting paid less.

For instance, while reviewing a long, serious book recently, I carefully wrote on notelets and stuck them in. I normally find sticky notes too wasteful, but this lot were an irresistible leaf-green and plum in colour (in a freelancer’s lonely life, things like nice stationery matter). So I really couldn’t blame my daughter when she opened the book which was lying around and spent a blissful 15 minutes taking out each note, admiring it, and using it to form a long green-and-plum snake. I mean, she’s six. She doesn’t recognise boundaries which are not physical. Colours are irresistible to her. Deep sigh. That’s four hours of my life I’m never getting back, and one needlessly late night to make good.

While working from home, your time is pretty much cut up and tossed all over the place like dhania in the bhel puri. It’s not fair on the kid either, because to a small child it’s inexplicable that mom/dad can be home, but not be available. Nothing says ‘I’m here, but just not for you’ better than looking into a laptop and typing busily while your child is saying something.

I should know — I’ve done it often enough. After six years of accepting my distracted parenting, my daughter finally said the other day, “You don’t spend time with me.” I started to protest and tell her about the hours I have spent shoveling food into her mouth. With the wisdom of her kind, she cut in, “And feeding me lunch is not spending time with me, ok?” For the record, if I didn’t have a chronic health problem, I’d be out there running for the VT fast every single day.

Because kids are small animals, they know it when you’re with them 100% and when you’re somewhere else in your head. When office-going parents come home tired, children, worshipful and huggy, are like balm to their weary souls. To us work-from-home types, kids are just another kind of doorbell. Cute, but still very much in the way.

Eight years back I read that Enid Blyton’s younger daughter had had an unhappy childhood because, apparently, Ma Blyton was more than a little neglectful of her own offspring. She was entirely focussed on creating magic for other people’s kids and on what we would today call ‘building her brand’. Then, my lips had curled in disgust at her cruelty. Now — except for the talent, the success and the wealth — I’ve begun to remind me just a little bit of her.

Between cooks, doorbells and courier deliveries, Anita Vachharajani tries to write children's books

This article appeared in the DNA of Oct 24, 2010

Just back from a holiday in Tamil Nadu. For a spell that was so hopelessly mis-planned and unplanned, I must say it ended up being great fun. Since Amit – calm, efficient, centred – is the producer and general go-to-guy for so many international crews shooting documentaries all over India, it’s logical that the one who plans and executes the family holidays should be me. The paranoid and anxious half.

This trip to TN, started, for some reason, by falling between the stools. I had thought we were on the right track - two days each in Mahabalipuram, Pondicherry, Auroville. Spaced out so my back wouldn’t give way. But then I got dire warnings – of major BOREDOM, among other things! Fearfully we went, and, as it turned out - thanks to serendipity and human kindness - we had a blast in every way, especially the visual.

Not only did we enjoy Pondi and Auroville, we met some lovely people in these places too. The highlights of the trip were the monoliths of Mahabs (for me the Mahishasuramardini cave which I walked in alone and the bizarrely wonderful sculpture college); Auroville and the Gump-a-lump Xmas party; and finally, the heritage walk with Ashok Panda of Intach, Pondicherry (later, getting gloriously lost in the Tamil Quarter, finding Choco-la, eating their rum choc and getting high under a hot TN sun), and later still, with exceptional luck, being allowed into Ananda Rangapillai’s house by his kind family.

Not only did we enjoy Pondi and Auroville, we met some lovely people in these places too. The highlights of the trip were the monoliths of Mahabs (for me the Mahishasuramardini cave which I walked in alone and the bizarrely wonderful sculpture college); Auroville and the Gump-a-lump Xmas party; and finally, the heritage walk with Ashok Panda of Intach, Pondicherry (later, getting gloriously lost in the Tamil Quarter, finding Choco-la, eating their rum choc and getting high under a hot TN sun), and later still, with exceptional luck, being allowed into Ananda Rangapillai’s house by his kind family.

A lot of what we saw and delighted in on this trip – the rock-cut caves in Mahabs, the street sellers sculpting little stone lockets and statues,  the whole of the man-made forest in Auroville, the crocheted shoes they make, the cookies they bake, the houses and streets in Pondi, the plaster cast angels and Santas sold outside Samba Kovil, the beautiful beadwork done on Ravi Varma’s lithos by Ananda Ranga's great-grand-daughter-in-law – was about craft in one form or the other.

the whole of the man-made forest in Auroville, the crocheted shoes they make, the cookies they bake, the houses and streets in Pondi, the plaster cast angels and Santas sold outside Samba Kovil, the beautiful beadwork done on Ravi Varma’s lithos by Ananda Ranga's great-grand-daughter-in-law – was about craft in one form or the other.

Lost And Found is a well-intentioned book. It has its heart in the right place. It’s only the mind which has gone for a long, meandering walk. The result is a plot so full of strains, threads and characters, that you stand a risk of losing yourself — and not in a good way either.

Lakshmi is the content writer for a porn website about ‘the sensory adventures of a beautiful, blind girl’ called, not very originally, ‘Kavita’. Years back, after a sexual encounter on a train one night, Lakshmi had become pregnant. Of the twins she delivered, one was abandoned in a temple and the other was given to a stranger in a taxi. One twin, Nirmal, is now a street child/actor, and the other, Salim, is a Pakistani jehadi. He is in Mumbai as a part of the 26/11 terror squad.

Placid Hari Odannur, a freelance journalist, is the one who, Lakshmi insists, forced himself on her 16 years ago. So, in the present, a night before the terror attack, she has kidnapped him and tied him up in her bathroom. The attack is set against this melee, a Cow Sena march, the terrorist-minder’s midlife crisis, newspaper-office politics and a rickshaw driver’s day.

In the hands of a less self-conscious writer, one with more rigour and economy of expression, the story might have crackled surreally. Surendran’s sub-plots, multiple threads, and tendency to tell you too much about every minor character, get tiresome. Sometimes you feel he is trying hard — but failing — to evoke a Llosa, a Marquez, and even, in desperation, a Manmohan Desai. His prose sparkles occasionally, when he manages to restrain himself from saying too much.

The book does have a few truly attractive elements. The fact that Surendran locates the story in the 26/11 attacks, and decides to delve a bit deeper there, to humanise those that the media has demonised entirely, is interesting. You get a definite sense of his engagement with Mumbai, its history, its realities and the way forces of fundamentalism play out here. To be fair, the novel does tighten up around halfway through.

The teeming landscape of Lost And Found is peppered with the implausible — a double-edged sword which perhaps only authors with the right mix of control and madness must play with. Because we have grown up on Manmohan Desai, we will buy the long-lost-brothers thing, and even the madness of the fictive world where the entire ‘family’ comes together in the course of one turbulent night. But even within this fictional universe, it’s hard to believe that Lakshmi, 19, educated and middle-class, would have had to run away to Goa and spend her pregnancy selling trinkets on a beach. Finally, it is the ham-handed treatment, the lack of really nuanced dialogues and situations that fails Lost And Found.

The newspaper’s dynamics are entertaining, but Surendran spends too much time exploring the local colour of the journalist’s world to really plunge deep. Lakshmi and her friend Beverly show little or no character development. Hari, too, though 35, seems implausibly adolescent. The street boy and the rickshaw driver often become clichés. Culpably, the characters often use words that are more the author’s than their own.

Surendran probably set off to create a mad, chaotic, maelstrom of a book. What he has done, though, is write one that has so many layers piled on to it that it sags under the weight of its own cleverness. And somehow, you can’t help but resent the writer for botching up what must have been a remarkable idea to begin with.

(This review appeared in the DNA of Sunday, Dec 26)

It’s hard work being a parent. But you’ve probably heard that one before. What is more intriguing is why people have kids in the first place. All through those nine months of nausea, I kept feeling that motherhood was evolution’s biggest joke on women. I figured the first time round you could get conned into it, but why would you do it a second or a third time?

There is of course a good measure of self-love involved in having a baby. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Look ma, I made a little human and it looks, talks and behaves like me. Also, as humans we love to be needed, and after six to eight months of being needed so viscerally by a small human being, you sort of begin to get off on the feeling. No one else looks at you with such adoration, no one else smiles with such delight when he sees your face (he’s probably thinking of lunch, but we'll let that pass). No one else, frankly, needs you with such abandon and such fury. Parenting can give you a heady sense of power. The nicest parents, I guess, are those who don’t misuse that power.

Though it isn’t apparent at first, this need to be needed contributes to some extent to most parents taking the plunge again. Five years after cribbing about pregnancy, when my child was beginning to become her own person, I was willing to go through all of it again just to have another needy little butterball in my arms. At some level, I’m guessing we're hard-wired to procreate, to make copies of ourselves and fill the planet. We could slow down now, because the planet has more than enough of us. But I guess our psyches haven’t heard the news yet.

Having a child is not just one long ego-massage, though (praise from passing strangers dries up after your kid hits seven). An emotional knuckle-duster waits just around the corner. Forget all the physical effort: the night feeds, the colic, the teething, the falls, the terrible twos, the preschool-admission rush, the homework, the tiffins you’ve packed andthe various illnesses and accidents that will have your kachhas in a twist forever.

That’s the easy part compared to the painful realisation that no matter what you do, no matter which toys you get and what theme parties you throw, one day the apple of your eye will turn into a Cynical Young Person. She will probably gobsmack you when she looks back at all your years as a devoted helicopter parent and smirks: ‘Well, I didn’t ask to be born, did I?’ To kids of a certain age, the only perfect parent is their best friend’s dad or mom. You just about manage not to disgrace yourself by starving her to death or something.

Six years back, between spraying out jets of vomit, I paused to ask my mother why women went through so much physical stress just to have children. Convinced that I was insane, and being the queen of understatement that she is, she shrugged and said, ‘Because when you have a child, time passes.’ It’s been over six years now that I’ve been a parent myself, and with every passing day, I realise that raising a child does play tricks with time.

Moments get stretched into lifetimes, so that you never forget that first smile, that first word, that first step. But days turn into liquid whirlwinds and simply swish by, till, before you know it, the adorable little cuddlebunny is a snarling teen. One more swish and he becomes a parent himself, aware of how much trouble raising a child can be, and finally, finally ready to be grateful for all you did.

Maybe mom was right. Maybe it’s worth it after all!

This article appeared in the DNA on Sunday, Sept 26, 2010

Link here: http://www.dnaindia.com/lifestyle/comment_mama-knows-best_1443353

Most people who live in Mumbai feel a peculiar sort of love for it. Many things are wrong with this dystopian, poorly-planned city, but most of us probably couldn’t bear to live elsewhere. If, like me, you feel this mix of emotions, then you’re going to love Gyan Prakash’s Mumbai Fables.

The book pulls together Mumbai’s many narratives – cinematic, literary, architectural and artistic. It is a tale of the legends, poems, books, novels, mysteries, newspaper articles, film songs, advertisements, architectural styles, comic books, apocryphal stories and paintings inspired by this city. Through them, Prakash is able to distill an imagining of Mumbai that is more real than a straightforward history, simply because it is told by so many different voices.

Mumbai’s story, as it unfolds in Prakash’s narrative, is an absorbing one, with varied sources: newspapers and pamphlets, books, paintings, interviews and songs, lawsuits and art. To each set of texts, Prakash brings his unique eye. With the entertaining Marathi writer Govind Narayan Madgavkar (Mumbaiche Varnan) or the Parsi writer Sir Dinshaw Wacha (Shells from the Sands of Bombay) or the British police commissioner S M Edwardes (ethnographic sketches for The Times of India), Prakash is interested in the visual ‘reading of the city’. To Madgavkar and Wacha, the ‘kaleidoscopic but orderly’ cosmopolitanism of Bombay is riveting. Edwardes is captivated by the colourful, exotic ‘Indian’ life that unfolds just outside of the British quarter. Like his contemporaries, he too is caught up in the ‘image of otherness’ that the city’s sights offer.

There are nuggets aplenty – you’ll never look at art deco or the Marine Drive in the same way again, and suddenly, street names develop a back-story. Some of our wealthiest philanthropists, for instance, were opium traders (like Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, the Wadias, the Cowasjis and Motichund Aminchund). There were committed professionals as well, like Dr A G Viegas, who diagnosed Bombay’s first case of bubonic plague. Confidence tricks and murder were a Bombay thing back then as well, as seen in Naoroji Dumasia’s crime books – one of which was based on the cases of Sardar Mir Abdul Ali, a real police detective.

The startling thing about Mumbai Fables is its sheer scope. Here you will find the story of the film studios and the secular seeds of the film industry; the rise and fall of the mill politics; the thrilling story of the Nanavati murder case and how the Blitz reported it; and unsettling accounts of the Babri-Masjid riots and the bomb blasts. Hindi film songs and Marathi Dalit poetry feature here, as do Meera Devidayal’s Mumbai-taxi-inspired paintings, the wonderful Hindi comic/graphic novel Doga, cartoons from Marathi newspapers, and the pulsating life and commerce of Dharavi. Like the creators of these texts, Prakash is an outsider and an admirer, but his prose is coloured with a sense of the beauty of this city – of its unique, alluring cosmopolitanism. Reading …Fables, you can understand what it was that drew everyone from the Konkani mill-worker to the Urdu poet here.

Prakash writes of the processes that shaped the city’s geography to accommodate human greed and industrial pressures, often at the cost of common sense. He discusses the various attempts made to ‘plan’ Mumbai, to reclaim land and ‘colonise nature’. Almost all of those attempts were either inspired or marred by greedy collusions between governments and corporates. This greed has overpowered vision, and ‘people’s needs’ have been

from kerala, chasing the red rain and sundry scientists, the male vachharajani tiredly reached trivandrum. where the kind hari, sound recordist, took him to a remaindered books stall, where he found these gems.

pipiou - a french book and disc (a small LP) with really sweet illustrations. it was an advt for green peas, using this fella and a slogan that went: "on a toujours besoin de petits pois chez soi" or in this girl detective's high-school french - one always needs a little peas at home. and please feel free to correct me if i'm wrong.

A Day With Wilbur Robinson

A Day With Wilbur Robinson by William Joyce, which, according to wikipedia 'follows the story of a boy (13 years old) who visits an unusual family and their home. While spending the day in the Robinson household, Wilbur's best friend joins in the search for Grandfather Robinson's missing false teeth and meets one wacky relative after another'. disney made a film based on it called

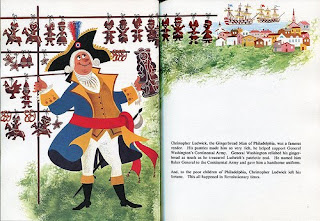

meet the robinsonsand then the jewel of the lot, richard erdoes's (1912-2008)

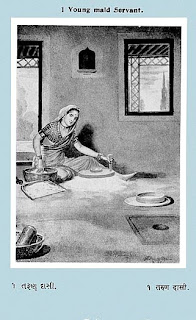

peddlers and vendors of the world. which is a part of the three-book series that this anthropologist-cum-illustrator (i guess in the pre-internet world, people had the time to explore all of their interests!) had done. the other two are: musicians of the world and (of all things) policemen of the world. it's all very crisp and mid-century modernist + western in style and execution, but so so so delightful. here are some pics from the books.

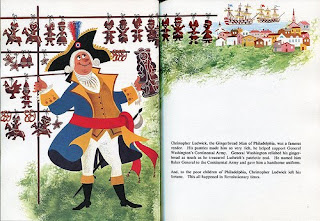

the gingerbread-man seller

the yugoslavian lemonade or coffee seller

![]()

Ayyan Mani, a Tamil Dalit, lives in Mumbai’s BDD chawl. His life is quite meshed with that of his neighbours, and yet, stands a bit apart, in that he dares to think beyond his grim circumstances. Working in the Institute of Theory and Research as PA to its Director, the formidable Arvind Acharya, Ayyan uses his power to make people wait, read confidential letters, listen to private phone calls, and delightfully, to subvert the thought-for-the-day once a week.

A conflict is brewing between Acharya and Jana Nambodri, the Deputy Director. To Ayyan, it is the War of the Brahmins, an event he longs to witness. An astrobiologist, Oparna Goshmaulik, enters the situation somewhere in the middle of all this. The playing out of academic politics takes an ugly hue, weaving its way around sexual politics and Ayyan’s private drama of creating a myth around his child.

Joseph’s plot is a tale that breathes around us. It is a story that needs the parallel realities of Mumbai to flower. His treatment of it, however, sometimes becomes clichéd and tedious, as in the drawing out of his main characters. The less important people – Jana, Ayyan’s wife Oja, his son Adi and Acharya’s wife Lavanya – are drawn with a delicate precision. The descriptions make you sit up, recognizing this human charade here and that foible there. While Ayyan, Acharya and Oparna populate long passages, somehow, their actions seem poorly etched and unconvincing. Acharya, the academic who falls for Oparna, definitely needed more skilful rendering.

Oparna’s character is almost cruelly drawn. She goes from a restrained yet stunning scientist, to a lovelorn seductress and finally, a vengeful saboteur who spills the beans on herself conveniently. Just in time to aid the plot, she disappears. Though Acharya sleeps with her for a fortnight and then tamely goes back to the silence of his marriage, he emerges as the idealist, whose job and personal life fall back in place nicely.

Joseph’s is a male novel, interested in the interior landscapes of men – whether poor or rich, Brahmin or Dalit, scientist or peon. How everyone reacts to Oparna in the Institute that has next to no women, leave alone attractive ones, is keenly observed. This focus on a male internal landscape is not problematic in itself. Many novels have engaged with the landscape of women’s worlds and still worked. Here, however, the plot suffers for it. You could perhaps accept Lavanya’s prompt forgiving of her husband; what you don’t feel convinced by is Oparna’s startling volte face.

The language ranges from tart, funny observations and brilliant single-stroke descriptions (the silver-haired Jana ‘had this affliction to be with the youth’) to awkward, embarrassing turns-of-phrase (like ‘the unmistakable insanity of formidable women who long to crumble’ or when looking at the young mothers outside his son’s school and their clothes, Ayyan observes that ‘their asymmetric panty-lines were like birds in the sky drawn by a careless cartoonist’). That is when you are not skipping pages of pointless prose. Annoyingly, the authorial voice keeps popping in disruptively. Ayyan, an intellectual and a political being, refuses to convert to Christianity and rejects Hinduism. His disdain is discussed economically, often humorously. He has opinions on everything, and sometimes, you suspect they are Joseph’s.

Read Serious Men because it explores the many small politics around us – between the smart man in a chawl and the more laidback; between the parents of the poor-but-brilliant boy in school a

For many days in April, I walked on a cloud of purplish-pink satin. The DNA had asked me to interview Philip Pullman, author of the His Dark Materials, and positively one of my favourite-est writers. As I told Amit, for just a few moments in time and space, he would be reading my words. Amit had wanted to call our first-born Lyra, since we had n when we were fresh from reading all three books. I would have too, except somehow, Lyra Vachharajani didn't quite do it for me.

The DNA had to chop the questions and answers for space, so here, peoples, is the whole truth!

In 1995, a year before Harry Potter flew in on his broom, a fantasy novel by Philip Pullman made a quiet yet significant entry. Northern Lights, the first part of the His Dark Materials Trilogy, tells the story of two children who meet across parallel universes and end up subverting the Church’s authority in a breathlessly exciting journey across seas, skies and worlds. Darker and less gimmicky than J K Rowling’s Potter story, the Trilogy sold 15 million copies, earned critical acclaim, won the coveted Whitbread Book Award and, inevitably, attracted moral censure.

With a wide range of influences like John Milton, William Blake, Heinrich von Kleist, the King James Bible and comic books, Pullman has written around 20 very successful books including plays, fairytales, and novels for the young. In a Pullman book – whatever its scope or size – the story is always king. Over email he tells Anita Vachharajani about his latest book, the allure of stories, and his advice to book-burning fundamentalists everywhere.

The books in the Dark Materials trilogy were filled with a longing for individual freedom within a humane, good and principled universe. There is also a robust rejection of authority. I feel that The Good Man Jesus… takes this theme further. Jesus is the more truly human, the more worshipful brother; while Christ has a larger vision for an organized religion. Could you comment on this?

In one way, the two brothers represent two of the types of authority described by the sociologist Max Weber. Jesus is the embodiment of charismatic leadership, which is based on the domination of the leader by means of miracles, magical powers, prophecy, and so on. Christ is the embodiment of a later sort of leadership: not possessing any sort of charismatic gifts himself, he envisages a church based on the authority of tradition. The progression from one to the other is typical of the way many organisations develop.

For someone who is reportedly an atheist, you take religion very seriously especially when you are being critical of it. Allusions to the Bible, prayers and hymns permeate your work and your discussions. Was religion a very significant part of your childhood?

Yes, very much so. Not in an oppressive way - simply that I grew up in the household of my grandfather, who was a clergyman in the Church of England. I went to church every Sunday, I absorbed the stories, I loved the language of the liturgy and the King James Bible. It's a large part of what made me.

You were a teacher during the ’70s. Did interacting directly with children influence your storytelling and your craft as a writer?

I was a teacher before we had such a thing as the National Curriculum in England. We had a great deal more freedom in those days, and I thought it would be a good idea to tell the children (I was teaching 11-13 year olds) some of the stories of the Greek myths - simply because they were wonderful stories, and I couldn’t see that they would ever hear them otherwise. So I did that, and I also wrote a play to be performed at the

A terrible, terrible writer's block has happened. It’s not your normal walnut-sized block, which you can prod and push with your finger and work around. Usually, at least my instinct to write puerile rubbish is readily available, and no walnut-sized critters can stop that. Nonsense, no-sense, and embarrassing pap – it’s there. On tap. Pours out at will, and then I can whittle and friends and Amit can edit and ‘suggest changes’ till a work of at least some honesty comes out. This time, there's no go. This particular block is – at my estimation – about 18 feet high and 12 feet wide. It’s slate-grey and hard and made up of tough materials like laziness and a good measure of greyhazystuff - a material which fills my mind with moss-like nothingness. It has not been spotted in a long time, but our records show that it has been known to exist.

Logically, this would be the time to take a tiny break. But because deadlines exist in a writer’s world just as they do elsewhere in civilized society, one feels guilty. And that’s when one begins to think of all forms of frittery as Work – as in, this Work will inspire me to get back to real work type of 'work'. Want to read a P D James? Well, I am a writer. So reading = work? Want to chat with a friend instead of struggling against the dark block? Hell-llo, I am a stressed out, work-from-home mom, surely talking to a friend, saving myself a therapist's fee and clearing my head for Writerly Thoughts is helpful? Want to spend my day looking at Doonesbury, Berke Breathed, Wondermark and the Oatmeal? Now isn't that a gesture of solidarity with these masters of sarcasm and irony, and isn’t reading good writing a useful thing in itself? Want to spend a day gazing at people's narcissistic outpourings on fb? Come now, the ability to laugh at human folly is No. 1 important quality in writers. Yes? Want to cheat on diet a bit and eat rubbish? Two threptin biscuits with a giant mug of tea instead of a fruit – surely, eating badly is a writer’s right? Hey, the world is full of idea-triggers. Who knows where my next one will come from?

As a writer, you’re supposed to dip your pen in the inkwell of life (finally, a metaphor – even a cheap one – remember what I said about rubbish on tap?). So practically anything can be Thought of as Work. Even – and especially – wasting time on the net, thinking up clever fb posts, reading recipes, chatting online and writing a blog post after so long (which, compared to fb status msgs, seems like real literature). Into this category fall expensive holidays (communing with nature and the swimming pool?) or shopping (people watching?) and sitting on the sofa eating chips, watching Seinfeld.

In a writer’s world, everything can be thought of as work. Even fun, especially fun. Or at least that's how the lazier among us writers think. Everything is Work, except real work – writing and slogging. Which is just so frickin’ uncool, I tell you. A writer's work should – ideally – be all about answering email interviews, helping design the book's cover, selecting and rejecting artworks with a sweet, condescending smile, signing royalty receipts and 10-page contracts, attending book readings, being gazed at worshipfully and posing for pictures which are a mix of youthful innocence + the self-assurance of age. What is this nonsense about writing, for three-hours-a-day, I say. That is so not what I paid my entrance fee to the mediocre-and-underpaid-writers-club for.

Vinda Karandikar, one of the greatest, liveliest and most radical Marathi poets passed away yesterday. At 92, he had no doubt led a full life... I encountered his Pishi Mavshi or Aunty Witch poems and other nonsense when I was translating for The Tenth Rasa: The Penguin Book of Indian Nonsense Verse. The poems saw me thru a fairly dull pregnancy and everyone on board was great fun to work with.

But Vinda's genius, with its sharp, prickly images and its completely fantastic flights, has stayed with me for the longest time... I missed being taught by him at uni, but am grateful to Mike for having given me the opportunity to translate these...

Pishi Mavshi's Backyard

(Orig title: Pishi Mavshiche Parasu)

The cat digs up the backyard soil;

Pishi Mavshi sows the seeds.

They will grow as tall as her

By morning-time when darkness flees.

If the plants are taller than Pishi

Or seem shorter by a fraction,

Pishi Mavshi’ll wring their necks and

Dance deliriously to distraction.

On the jackfruit tree of Pishi

Mangoes grow in season and out

On the mangoes, guavas grow and

Banana trees on them soon sprout.

When banana bunches appear

Pishi kicks the troubled tree;

The tree starts trembling terribly and

Out pop saplings one, two, three!

The cat digs up the backyard soil,

And people say that they have seen

At high noon Pishi from a skull

Pour water on her garden green.

I wish someone would make this into a picture book. What drawings it would have! I love the image of Pishi shaking the plants' by their necks. It had n in splits too. There are a few more - funny, witty, full of mad wordplay. But Pishi with her reluctance to be liked or understood, with her profound sense of drama and human-ness, is simply my favourite person!

From The Tenth Rasa - The Penguin Book of Indian Nonsense Verse, Edited by Micheal Heyman, Anushka Ravishankar and Sumanyu S., Published by Penguin, © Penguin and Anita Vachharajani

An interview which appeared in the Deccan Herald of December 6, 2009

Anita & Amit Vachharajani are passionately involved with children’s literature, and the books by this writer-illustrator couple are proof of that. While Junagadh-born Amit went to the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad and later shifted to Mumbai to pursue a career in filmmaking, Mumbai-born Anita conducts writing workshops for children, helping them express themselves more freely. The couple, which has an enviable collection of children’s books at their home in Mumbai, has recently come up with Amazing India – A State-By-State Guide (Scholastic), a beautifully-illustrated book introducing all regions of the country in a style that will make them aware about India’s diversity in a fun way. The Vachharajanis spoke to Deccan Herald’s Utpal Borpujari on why it was important to bring out a book of this sort:

How did you conceive the idea for this book?

Scholastic USA had published a book called My World – A Country-by-country Guide, and our publisher, Scholastic India, felt that a similar book on India would be great. We began working on Amazing India about two-and-a-half years back. It’s a richly-illustrated description, covering everything from India’s forests and animals, to its peoples, arts, crafts, music, film-makers, poets, dancers, warriors and artists.

What were in your ‘do’ and ‘not to do’ lists while compiling the book considering that India has so much to offer?

What we did not want to do was give kids a book with a laundry list of facts that they would be tempted to memorise! We wanted to fill kids with the wonder of this large, complex land through an exciting and visually-rich book. We chose to present a mix of facts laced with humour, so that each child who looked at it – irrespective of his or her age and interests – would find it engaging.

How did you go about deciding what to include and what not to in the book?

For each state, we wanted some points on history, geography and ecology; some on monuments; some on people, arts, dance, music and craft; plus some facts and figures. We did focus a little more on ecology, because India’s animals, wetlands, forests, farms, rivers and mountains are all in grave danger. Of course, we kept it flexible – in Karnataka, for instance, we used the monuments built by powerful dynasties to tell the state’s story.

With every state having so much to offer, wasn’t it difficult to leave out quite a lot of info?

It’s incredible that in India, each region is so different from the other, and so full of its distinct species, land forms and cultural practices. Despite this, however, a lot of intermingling happened between the thoughts and practices of different peoples to create what we so easily call ‘Indian culture’ today. To give children a small but memorable peek into this wonderful complexity, we devoted two pages to each state, with a map, informative points, illustrations, a fact file and an arts and crafts section. Space was tight and it was really tough choosing what would go in.

How did you do the research? Did you make personal visits to the states or you relied on available information?

Ideally, we would have loved to experience every single thing we wrote about and drew, but given the wide scope of this book, that might have taken us a little over a lifetime to do. Researching it was like being back in school, but with the freedom to choose what we wanted to study! Once we spotted an interesting fact, the first step would be to cross-check it across different sources. Then we would go to the next step in the research, which was finding correct visual references.

How did you de

View Next 25 Posts

Lovely blog. Thanks for sharing.