new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: 2015 picture books, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 12 of 12

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: 2015 picture books in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 12/27/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Kids Can Press,

Best Books,

picture book reviews,

Japanese children's literature,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 picture books,

2015 reviews,

Akiko Miyakoshi,

Japanese imports,

Reviews,

Add a tag

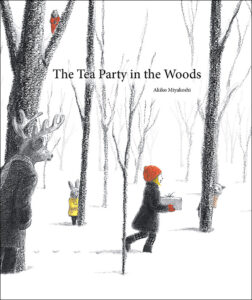

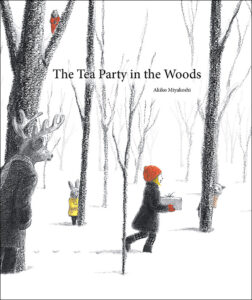

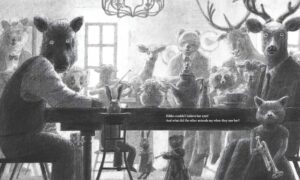

The Tea Party in the Woods

The Tea Party in the Woods

By Akiko Miyakoshi

Kids Can Press

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1771381079

Ages 3-6

There are picture books out there that feel like short films. Some of the time they’re adapted into them (as with The Snowman or The Lost Thing or Lost and Found) and sometimes they’re made in tandem (The Fantastic Flying Books of Morris Lessmore). And some of the time you know, deep in your heart of hearts, that they will never see the silver screen. That they will remain perfect little evocative pieces that seep deep into the softer linings of a child’s brain, changing them, affecting them, and remaining there for decades in some form. The Tea Party in the Woods is like that. It looks on first glance like what one might characterize to be a “quiet” book. Upon further consideration, however, it is walking the tightrope between fear and comfort. We are in safe hands from the start to the finish but there’s no moment when you relax entirely. In this strangeness we find a magnificent book.

Having snowed all night, Kikko’s father takes off through the woods to shovel out the walk of her grandmother. When he forgets to bring along the pie Kikko’s mother baked for the occasion, Kikko takes off after him. She knows the way but when she spots him in the distance she smashes the pie in her excitement. Catching up, there’s something strange about her father. He enters a house she’s never seen before. Upon closer inspection, the man inside isn’t a man at all but a bear. A sweet lamb soon invites Kikko in, and there she meets a pack of wild animals, all polite as can be and interested in her. When she confesses to having destroyed her grandmother’s cake, they lend her slices of their own, and then march her on her way with full musical accompaniment.

Part of what I like so much about this book is that when a kid reads it they’re probably just taking it at face value. Girl goes into woods, hangs out with clothed furry denizens, and so on, and such. Adults, by contrast, are bringing to the book all sorts of literary, cinematic, and theatrical references of their own. A girl entering the woods with red on her head so as to reach her grandmother’s reeks of Little Red Riding Hood (and I can neither confirm nor deny the presence of a wolf at the tea party). The story of a girl wandering into the woods on her own and meeting the wild denizens who live there for a feast makes the book feel like a best case fairy encounter scenario. In this light the line, “You’re never alone in the woods”, so comforting here, takes on an entirely different feel. Some have mentioned comparisons to Alice in Wonderland as well, but the tone is entirely different. This is more akin to the meal with the badgers in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe than anything Lewis Carroll happened to cook up.

Part of what I like so much about this book is that when a kid reads it they’re probably just taking it at face value. Girl goes into woods, hangs out with clothed furry denizens, and so on, and such. Adults, by contrast, are bringing to the book all sorts of literary, cinematic, and theatrical references of their own. A girl entering the woods with red on her head so as to reach her grandmother’s reeks of Little Red Riding Hood (and I can neither confirm nor deny the presence of a wolf at the tea party). The story of a girl wandering into the woods on her own and meeting the wild denizens who live there for a feast makes the book feel like a best case fairy encounter scenario. In this light the line, “You’re never alone in the woods”, so comforting here, takes on an entirely different feel. Some have mentioned comparisons to Alice in Wonderland as well, but the tone is entirely different. This is more akin to the meal with the badgers in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe than anything Lewis Carroll happened to cook up.

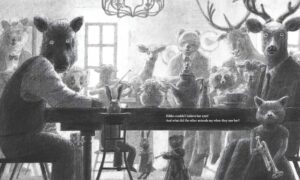

Yet it is the art that is, in many ways, the true allure. Kirkus compared the art to both minimalist Japanese prints as well as Dutch still life’s. Miyakoshi does indeed do marvelous things with light, but to my mind it’s the use of color that’s the most impressive. Red and yellow and the occasional hint of orange/peach appear at choice moments. Against a sea of black and white they draw your eye precisely to where it needs to go. That said, I felt it was Miyakoshi’s artistic choices that impressed me most. Nowhere is this more evident than when Kikko  enters the party for the first time, every animal in the place staring at her. It’s a magnificent image. The best in the book by far. Somehow, Miyakoshi was able to draw this scene in such a way where the expressions on the animals’ faces are ambiguous. It isn’t just that they are animals. First and foremost, it seems clear that they are caught entirely unguarded in Kikko’s presence. The animals that had been playing music have stopped mid-note. And I, an adult, looked at this scene and (as I mentioned before) applied my own interpretation on how things could go. While it would be conceivable for Kikko to walk away from the party unscathed, in the hands of another writer she could easily have ended up the main course. That is probably why Miyakoshi follows up that two-page spread (which should have been wordless, but that’s neither here nor there) with an immediate scene of friendly, comforting words and images. The animals not only accept Kikko’s presence, they welcome her, are interested in her, and even help her when they discover her plight (smashing her grandmother’s pie). Adults everywhere who have found themselves unaccompanied (and even uninvited) at parties where they knew no one, and will recognize in this a clearly idyllic, unapologetically optimistic situation. In other words, perfect picture book fodder.

enters the party for the first time, every animal in the place staring at her. It’s a magnificent image. The best in the book by far. Somehow, Miyakoshi was able to draw this scene in such a way where the expressions on the animals’ faces are ambiguous. It isn’t just that they are animals. First and foremost, it seems clear that they are caught entirely unguarded in Kikko’s presence. The animals that had been playing music have stopped mid-note. And I, an adult, looked at this scene and (as I mentioned before) applied my own interpretation on how things could go. While it would be conceivable for Kikko to walk away from the party unscathed, in the hands of another writer she could easily have ended up the main course. That is probably why Miyakoshi follows up that two-page spread (which should have been wordless, but that’s neither here nor there) with an immediate scene of friendly, comforting words and images. The animals not only accept Kikko’s presence, they welcome her, are interested in her, and even help her when they discover her plight (smashing her grandmother’s pie). Adults everywhere who have found themselves unaccompanied (and even uninvited) at parties where they knew no one, and will recognize in this a clearly idyllic, unapologetically optimistic situation. In other words, perfect picture book fodder.

Translation is a delicate art. Done well, it creates some of our greatest children’s literature masterpieces. Done poorly and the book just melts away from the publishing world like mist, as if it was never there. Because I do not have a final copy of this book in hand, I don’t know if the translator for this book is ever named. Whoever they are, I think they knew precisely how to tackle it. Originally published in what I believe to be Japan, I marvel even now at how the story opens. The first line reads, “That morning, Kikko had awoken to a winter wonderland.” We are plunged into the story in such as way as to believe that we’ve been reading about Kikko for quite some time. It doesn’t say “One morning”, which is a distinction of vast importance. It says “That morning” and we are left to consider why that choice was made. What happened before “That morning” that led up to the events of this particular day? Whole short stories have been conjured from less. I love it.

If none of the reasons I’ve mentioned do it for you, consider this: On the front inside book flap of this book perches a squirrel in a bright red party dress in the crook of a tree. Tiny squirrel. Tiny red flowing gown. A detail you might easily miss the first ten times you read this book but it is there and just makes the book for me. Add in the tone, the light, the mood, and the writing itself and you have a book that will be remembered long after the name has faded from its readers’ minds. Something about this book will stick with your kids for all time. If you want something that feels classic and safely dangerous, Miyakoshi’s book is a rare piece of comfortable animal noir. No one is alone in the woods and after this book no one would want to be.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 11/27/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

David Teague,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 picture books,

Reviews,

picture books,

Hyperion,

Best Books,

Antoinette Portis,

Disney Book Group,

Add a tag

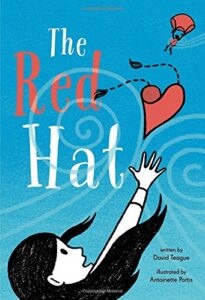

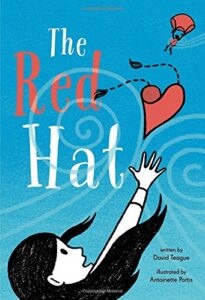

The Red Hat

The Red Hat

By David Teague

Illustrated by Antoinette Portis

Disney Hyperion (an imprint of Disney Book Group)

$16.99

ISBN: 9781423134114

Ages 4-7

On shelves December 8th

There is a story out there, and I don’t know if it is true, that the great children’s librarian Anne Carroll Moore had such a low opinion of children’s books that involved “gimmicks” (read: interactive elements of any sort) that upon encountering them she’d dismiss each and every one with a single word: Truck. If it was seen as below contempt, it was “truck”. Pat the Bunny, for example, was not to her taste, but it did usher in a new era of children’s literature. Books that, to this day, utilize different tricks to engage the interest of child readers. In the best of cases the art and the text of a picture book are supposed to be of the highest possible caliber. To paraphrase Walter de la Mare, only the rarest kind of best is good enough for our kids, yes? That said, not all picture books have to attempt to be works of great, grand literature and artistic merit. There are funny books and silly ones that do just as well. Take it a step even farther, and I’d say that the interactive elements that so horrified Ms. Moore back in the day have great potential to aid in storytelling. Though she would be (rightly) disgusted by books like Rainbow Fish that entice children through methods cheap and deeply unappealing, I fancy The Red Hat would have given her pause. After considering the book seriously, a person can’t dismiss it merely because it tends towards the shiny. Lovingly written and elegantly drawn, Teague and Portis flirt with transparent spot gloss, but it’s their storytelling and artistic choices that will keep their young readers riveted.

With a name like Billy Hightower, it’s little wonder that the boy in question lives “atop the world’s tallest building”. It’s a beautiful view, but a lonely one, so when a construction crew one day builds a tower across the way, the appearance of a girl in a red hat intrigues Billy. Desperate to connect with her, he attempts various methods of communication, only to be stumped by the wind at every turn. Shouting fails. Paper airplanes plummet. A kite dances just out of reach. Then Billy tries the boldest method of reaching the girl possible, only to find that he himself is snatched from her grasp. Fortunately a soft landing and a good old-fashioned elevator trump the wind at last. Curlicues of spot gloss evoke the whirly-twirly wind and all its tricksy ways.

Great Moments of Spot Gloss in Picture Book History: Um . . . hm. That’s a stumper. I’m not saying it’s never happened. I’m just saying that when I myself try to conjure up a book, any book, that’s ever used it to proper effect, I pull up a blank. Now what do I mean exactly when I say this book is using this kind of “gloss”? Well, it’s a subtle layer of shininess. Not glittery, or anything so tawdry as that. From cover to interior spreads, these spirals of gloss evoke the invisible wind. They’re lovely but clearly mischievous, tossing messages and teasing the ties of a hat. Look at the book a couple times and you notice that the only part of the book that does not contain this shiny wind is the final two-page image of our heroes. They’re outdoors but the wind has been defeated in the face of Billy’s persistence. If you feel a peace looking at the two kids eyeing one another, it may have less to do with what you see than what you don’t.

Naturally Antoinette Portis is to be credited here, though I don’t know if the idea of using the spot gloss necessarily originated with her. It is possible that the book’s editor tossed Portis the manuscript with the clear understanding that gloss would be the name of the game. That said, I felt like the illustrator was given a great deal of room to grow with this book. I remember back in the day when her books Not a Box and Not a Stick were the height of 32-page minimalism. She has such a strong sense of design, but even when she was doing books like Wait and the rather gloriously titled Princess Super Kitty her color scheme was standard. In The Red Hat all you have to look at are great swath of blue, the black and white of the characters, an occasional jab of gray, and the moments when red makes an appearance. There is always a little jolt of red (around Billy’s neck, on a street light, from a carpet, etc). It’s the red coupled with that blue that really makes the book pop. By all rights a red, white, and blue cover should strike you on some level as patriotic. Not the case here.

Not that the book is without flaw. For the most part I enjoyed the pacing of the story. I loved the fairytale element of Billy tossed high into the sky by a jealous wind. I loved the color scheme, the gloss, and the characters. What I did not love was a moment near the end of the book where pertinent text is completely obscured by its placement on the art. Billy has flown and landed from the sky. He’s on the ground below, the wind buffeting him like made. He enters the girl’s building and takes the elevator up. The story says, “At the elevator, he punched UP, and he knocked at the first door on the top floor.” We see him extending his hand to the girl, her hat clutched in the other. Then you turn the page and it just says, “The Beginning.” Wait, what? I had to go back and really check before I realized that there was a whole slew of text and dialogue hidden at the bottom of that previous spread. Against a speckled gray and white floor the black text is expertly camouflaged. I know that some designers cringe at the thought of suddenly interjecting a white text box around a selection of writing, but in this particular case I’m afraid it was almost a necessity. Either than or toning down the speckles to the lightest of light grays.

Aside from that, it’s sublime. A sweet story of friendship (possibly leading to more someday) from the top of the world. Do we really believe that Billy lives on the top of the highest building in the world? Billy apparently does, and that’s good enough for us. But even the tallest building can find its match. And even the loneliest of kids can, through sheer pig-headed persistence, make their voices heard. A windy, shiny book without a hint of bluster.

On shelves December 8th.

Source: F&G sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

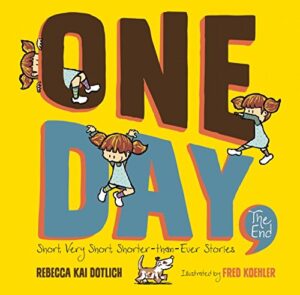

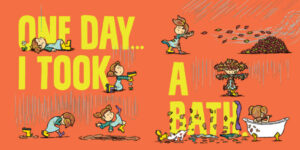

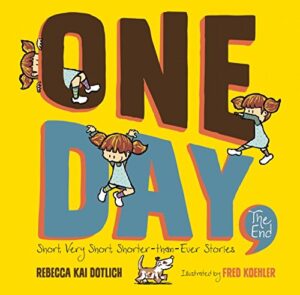

One Day, The End

One Day, The End

By Rebecca Kai Dotlich

Illustrated by Fred Koehler

Boyds Mills Press (an imprint of Highlights)

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-62091-451-9

Ages 4-7

On shelves now.

Last evening I was reading Quest by Aaron Becker to my daughter for bedtime. It’s a good book. I’ve read it approximately 20 times by now, so I should know. Anyway, we’re reading the book, which is wordless and requires that the reader really pay attention to the story, and as we start I point out to my daughter some feature at the beginning involving statues. Immediately she countered with a different statue detail at the back of the book that I, though having read this story over and over again, had completely and totally missed. That’s the cool thing about child readers. Not only do they find the details the adults are completely oblivious to, but on top of that they’re coming up with cool narratives and storylines of their own, on spinning off of the ones conceived of by the author/illustrators. So when I see a book like One Day, The End I just wanna put my hands together and applaud. Rebecca Kai Dotlich is a genius (and Fred Koehler ain’t sleeping on the job either). She figured out that for kids a story is just as much a product of the relationship between a child and a book’s pictures as it is between a child and a book’s words. Sometimes more. Sometimes much more. And sometimes they’ll be handed a book like this one that lets them examine and indulge to their heart’s delight.

Do you know how to tell a story? It’s easy! Listen to a couple of these.

“One day… I felt like stomping. Stomp stomp stomp stomp stomp stomp stomp stomp stomp stomp stomp stomp.”

“One day… I lost my dog. I found him.”

“One day… I ran away. I cam home.”

A small girl tells her tales with a minimum of words. Yet hidden in these words, sometimes literally, are epic narratives. The most ordinary of actions can turn into huge adventures. By the end, the girl is writing whole books out of what could normally be seen as mundane everyday actions. Yet two sentences can yield a whole lot of action.

These days the buzzword of the hour appears to be “visual storytelling” or “visual learning”. And why not? We live in a world of constant, perpetual, enticing screens (or “shiny rectangles” as my brother-in-law likes to call them). Graphic novels have achieved a level of respect and quality hitherto unknown in the history of publishing and I don’t think it’s a stretch to believe that there are more picture books being published today than ever before. Into this brave new world come the kids, their minds making connections and storylines. They mix reality and fantasy together with aplomb. They give their toys lives and thoughts and feelings. So to see a book that sets them free to give these imaginings a little form and structure? That’s great.

On the most basic level, the book is perfect for class writing prompts. The teacher tells the kids to pick a two-sentence story in the book and expand upon it. It works to a certain extent, but I wonder if in some ways it sort of skips the point of the book itself. One of the many points of One Day, The End is that when it comes to picture books, storytelling can be more than simply whatever it is that the words say. Another point is that you don’t have to be loquacious to tell a story. Two sentences will do. It would be fun to do an exercise with kids where they tell two-sentence stories. Two sentences takes off a lot of pressure. There’s no need to include a rise and fall to the action. Anyone can tell a story (a valuable lesson). This book shows you how.

On the most basic level, the book is perfect for class writing prompts. The teacher tells the kids to pick a two-sentence story in the book and expand upon it. It works to a certain extent, but I wonder if in some ways it sort of skips the point of the book itself. One of the many points of One Day, The End is that when it comes to picture books, storytelling can be more than simply whatever it is that the words say. Another point is that you don’t have to be loquacious to tell a story. Two sentences will do. It would be fun to do an exercise with kids where they tell two-sentence stories. Two sentences takes off a lot of pressure. There’s no need to include a rise and fall to the action. Anyone can tell a story (a valuable lesson). This book shows you how.

All that aside, the ending of the book was particularly interesting to me. Picture book authors that can stick the landing (as it were) when they finish their stories are rare birds. Such books don’t necessarily come along every day. That said, the ending of One Day, The End is rather magnificent. The whole book until this point has been showing the reader that in the shortest of stories there can be whole epic narratives. So when our young heroine begins by saying “One Day… I wanted to Write a Book” the accompanying picture shows her at a typewriter (a retro move) imagining a whole host of new situations. Turn the page and the following “So I did” shows a line of thick books, each one with a title that relates to the tiny two sentence stories we witnessed before. The implication at work here for kids is that even in the briefest of moments of our lives, which adults might hurry through or remember in abbreviated ways, there are untold tales just waiting to be told. This book is for the five-year-old burgeoning writer. This character wanted to write a book and did. Who’s to say you couldn’t do the same?

I didn’t recognize Fred Koehler’s style the first time I read through this book. Maybe this is a little more understandable when I mention that he only just debuted this year with his own picture book, How to Cheer Up Dad. That book starred affectionate pachyderms. This one, all too human humans. In order to bring Dotlich’s story to life, Koehler sets the action in a kind of timeless past. Cell phones computers, and even televisions are not in evidence. There’s one sequence when our heroine is playing hide-and-go-seek with her brother and we see a large swath of their home together. It’s rather technologically barren, a fact drilled home later when the typewriter makes its somewhat inexplicable appearance. Fortunately, Koehler has a lot going for him, beyond this attempt at timelessness. The font of the story is practically a tale in and of itself, always shifting and changing to suit the described action. And the layouts! I don’t mind saying that part of the reason this book feels so fresh and interesting and fun has a lot to do with Koehler’s layouts. The words that make up the stories appear as part of the illustrated scenes, sometimes dominating the action and sometimes playing a role in it. For example, the story that begins with “One day… I wanted to be a spy” actually shows the girl peering between the letters of “spy”

I didn’t recognize Fred Koehler’s style the first time I read through this book. Maybe this is a little more understandable when I mention that he only just debuted this year with his own picture book, How to Cheer Up Dad. That book starred affectionate pachyderms. This one, all too human humans. In order to bring Dotlich’s story to life, Koehler sets the action in a kind of timeless past. Cell phones computers, and even televisions are not in evidence. There’s one sequence when our heroine is playing hide-and-go-seek with her brother and we see a large swath of their home together. It’s rather technologically barren, a fact drilled home later when the typewriter makes its somewhat inexplicable appearance. Fortunately, Koehler has a lot going for him, beyond this attempt at timelessness. The font of the story is practically a tale in and of itself, always shifting and changing to suit the described action. And the layouts! I don’t mind saying that part of the reason this book feels so fresh and interesting and fun has a lot to do with Koehler’s layouts. The words that make up the stories appear as part of the illustrated scenes, sometimes dominating the action and sometimes playing a role in it. For example, the story that begins with “One day… I wanted to be a spy” actually shows the girl peering between the letters of “spy”

I also loved that Koehler wasn’t afraid to reward rereadings. Attentive readers will be able to witness the smaller sub-adventures of a cat, a squirrel, a bird, and a little white dog that appear in the periphery of all the action. Then there are even smaller details that you wouldn’t notice on a first glance. The story, “I went to school. I came home” shows our plucky young gal dilly-dallying on her way to class (following a cat that will come up again in a later tale) only to accidentally leave her books somewhere en route. She runs to her classroom, but sharp-eyed spotters will note her missing backpack. Next thing you know the class is following instructions on doing science experiments and she peers at her neighbor (every kid doing the experiments is looking at their book, save her), and accidentally pours her solution into the wrong beaker. And there are other details about the characters themselves that are worth discovering, like that our storyteller always wears mismatched socks. As for the callbacks, if you pay attention you’ll see that an element that appears in one story (like a rubber boot placed over a flower in the rain) may later crop up again later (that same flower grows out of the boot a little later).

To sum up, why not take a page out of this book?

One day… I read a picture book. It was great.

The End.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews: Kirkus,

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 9/23/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

Penguin,

Best Books,

Dial Books for Young Readers,

a cool cool robot,

Adam Rubin,

picture book readalouds,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 picture books,

Daniel Salmeri,

Add a tag

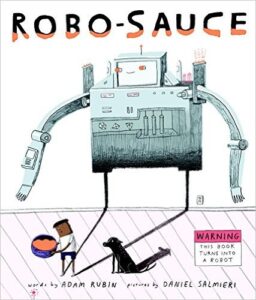

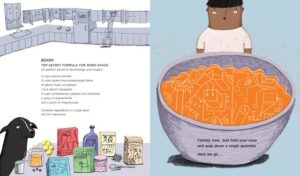

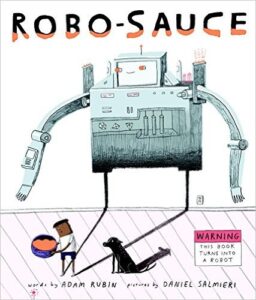

Robo-Sauce

Robo-Sauce

By Adam Rubin

Illustrated by Daniel Salmieri

Dial (an imprint of Penguin Books)

$18.99

ISBN: 978-0525428879

Ages 4-6

On shelves October 20th.

When I whip out the old we’re-living-in-a-golden-age-of-picture-book-creation argument with colleagues and friends, they humor what I’m sure they consider to be my hyperbole. Suuuuuure we are, Betsy. Not prone to exaggeration or anything, are you? But honestly, I think I could make a case for it. Look at the picture books of the past. They were beautiful, intricately crafted, and many of them are memorable and pertinent to child readers today. What other art form for kids can say as much? You don’t exactly have five-year-olds mooning over Kukla, Fran and Ollie these days, right (sorry, mom)? But hand them Goodnight Moon and all is well. Now look at picture books today. We’re living in a visual learner’s world. The combination of relaxed picture books standards (example: comics and meta storytelling are a-okay!), publishers willing to try something new and weird, and a world where technology and visual learning plays a heavy hand in our day-to-day lives yields creative attempts hitherto unknown or impossible to author/illustrators as recently as ten years ago. And when I try to think of a picture that combines these elements (meta storytelling / new and weird / technology permeating everything we do) no book typifies all of this better or with as much panache as Robo-Sauce. Because if I leave you understanding one thing today it is this: This may well contain the craziest picture book construction from a major publisher I have EVER seen. No. Seriously. This is insane. Don’t say I didn’t warn you either.

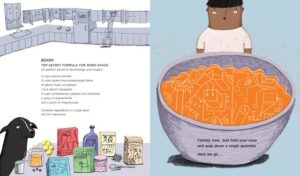

We all know that kid who thinks pretending to be a robot is the most fun you can have. When the hero of this story tries it though he just ends up annoying his family. That’s when the narrator starts talking to him directly. What if there was a recipe for turning yourself into a REAL robot? Would you make it? Would you take it? You BET you would! But once the boy starts destroying things in true mechanical fashion (I bet you were unaware that robots were capable of creating tornadoes, weren’t you?), it’s pretty lonely. The narrator attempts to impart a bit of a lesson here about how to appreciate your family/dog/life but when it hands over the antidote the robot destroys it on sight. Why? Because it’s just created a Robo-Sauce Launcher with which to turn its family, its dog, the entire world, and even the very book you are reading into robots! How do you turn a normal picture book into a robot? Behold the pull out cover that wraps around the book. Once you put it on and open the other cover, the text and images inside are entirely robotized. Robo-Domination is near. It may, however, involve some pretty keen cardboard box suits.

So you’re probably wondering what I meant when I said that the book has a cover that turns into a robot book. Honestly, I tried to figure out how I would verbally explain this. In the end I decided to do something I’d never done before. For the first time ever, I’m including a video as part of my review. Behold the explanation of the book’s one-of-a-kind feature:

These days the idea that a narrator would speak directly to the characters in a book is par for the course. Breaking down the fourth wall has grown, how do you say, passé. We almost expect all our books to be interactive in some way. If Press Here made the idea of treating a book like an app palatable then it stands to reason that competing books would have to up the ante, as it were. In fact, I guess if I’m going to be perfectly honest here, I think I’ve kind of been waiting for Robo-Sauce for a long time. Intrusive narrators, characters you have to yell at, books you shake, they’re commonplace. Into this jaded publishing scene stepped Rubin and Salmieri. They’re New York Times bestsellers in their own right ( Dragons Love Tacos) so they’re not exactly newbies to the field. They’ve proven their selling power. But by what witchcraft they convinced Penguin to include a shiny pull out cover and to print a fifth of the book upside down, I know not. All I can be certain of is that this is a book of the moment. It is indicative of something far greater than itself. Either it will spark a new trend in picture books as a whole or it will be remembered as an interesting novelty piece that typified a changing era.

Let’s look at the book itself then. In terms of the text, I’m a fan. The narrator’s intrusive voice allows the reader to take on the role of adult scold. Kids love it when you yell at a book’s characters for being too silly in some way and this story allows you to do precisely that. Admittedly, I do wish that Rubin had pushed the narrator-trying-to-teach-a-lesson aspect a little farther. If the lesson it was trying to impart was a bit clearer than just the standard “love your family” shtick then it could have had more of a punch. Imagine if, instead, the book was trying to teach the boy about rejecting technology or something like that. Any picture book that could wink slyly at the current crop of drop-the-iPhone-pick-up-a-book titles currently en vogue would be doing the world a service. I’m not saying I disagree with their message. They’re just all rather samey samey and it would be nice to see someone poke a little fun at them (while still, by the end, reinforcing the same message).

Let’s look at the book itself then. In terms of the text, I’m a fan. The narrator’s intrusive voice allows the reader to take on the role of adult scold. Kids love it when you yell at a book’s characters for being too silly in some way and this story allows you to do precisely that. Admittedly, I do wish that Rubin had pushed the narrator-trying-to-teach-a-lesson aspect a little farther. If the lesson it was trying to impart was a bit clearer than just the standard “love your family” shtick then it could have had more of a punch. Imagine if, instead, the book was trying to teach the boy about rejecting technology or something like that. Any picture book that could wink slyly at the current crop of drop-the-iPhone-pick-up-a-book titles currently en vogue would be doing the world a service. I’m not saying I disagree with their message. They’re just all rather samey samey and it would be nice to see someone poke a little fun at them (while still, by the end, reinforcing the same message).

As for Salmieri’s art, the limited color palette is very interesting. You’ve your Day-Glo orange, black, white, brown, and pale pink (didn’t see that one coming). Other colors make the occasional cameo but the bulk of the book is pretty limited. It allows the orange to shine (or, in the case of the robot cover, the limited palette allows for something particularly shiny). And check out that subtle breaking down of visual stereotypes! Black dad and white mom. A sister that enjoys playing with trucks. I am ON BOARD with all this.

I won’t be the last parent/librarian/squishy human to hold this book in my hands and wonder what the heck to do with it. What I do know is that it’s a lot of fun. Totally original. And it has a bunch of robots in it causing massive amounts of destruction. All told, I’d say that’s a win. So domo arigato, Misters Rubin and Salmieri. Domo arigato a whole bunch.

On shelves October 20th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews: A star from Publishers Weekly, Kirkus,

Misc: Still need some help figuring out the cover? Check out the book’s website here.

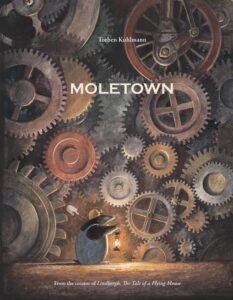

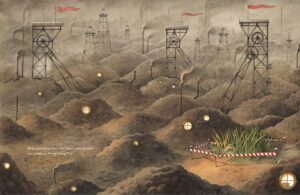

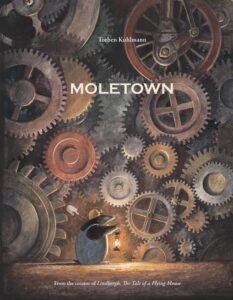

Moletown

Moletown

By Torben Kuhlmann

North/South Books, Inc.

$17.95

ISBN: 978-0-7358-4208-3

Ages 4-6

On shelves October 1st

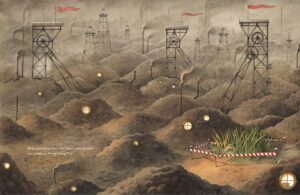

Cautionary tales for kids who can’t do a darn thing about the original problem. It’s sort of a subgenre of its very own. As I hold this lovely little book, Moletown, in my hands I am transported back in time to the moment I first encountered The Lorax by Dr. Seuss. A child of the 80s, my youth was a time when scaring kids straight was an accepted educational technique utilized in everything from environmental protection to saying no to drugs. The film version of The Lorax bore this out and gave me some nice little bite-sized psychological scars for years to come. These days we don’t usually go in for the whole learning-through-fear technique. Even picture books that sport a message are more prone to be mildly sad than anything else. What makes Moletown so very interesting then is its inclination to tap into popular tropes in our own history, then turn them ever so gently on their heads. The end result is a book where you might easily lose sight of the bigger picture, until that final moment when everything becomes horribly clear.

“The story of Moletown began many years ago.” A single solitary mole moves beneath a meadow to live. Not long thereafter he’s joined by other moles “And over time, life underground changed…” Before our eyes we see it. We see the vast construction projects taking place to make Moletown a livable community. We see the population explosion, the increased technological advances, and different transportation models. Life becomes busier for the moles, while outside in the meadow nature is taking a severe hit. The green is close to disappearing altogether, but turn to the last pages in the book and there we see evidence not just of change, but of the moles as a whole taking on the responsibility of their newly green again meadowlands.

Kuhlmann initially burst upon the American picture book scene with the highly detailed Lindbergh, a story of a mouse with a yen for flight. A little bit The Arrival, a little bit An American Tale and a little bit steampunk via Beatrix Potter, it was his hyper realistic animals placed in extraordinary circumstances that stayed with young readers. In Moletown that level of detail and attention is there, but the moles have a far more cartoonish feel to them. This is not to say that they don’t look like moles, every inch of them. Yet Kuhlmann has simplified his hyper-realistic renderings of animals and traded that attention in for set designs and landscapes. Here he plays with perspective, plunging us down into the heart of the moles’ mining operation, the scaffolding twisting around and around, down and down. Sharp eyed spotters will note other spreads where the stop signs are shaped like mole claws and the trains go vertically as well as horizontally. The details are there to an elegant degree, but the feel is different from Lindbergh certainly (as is the length of the piece).

Kuhlmann initially burst upon the American picture book scene with the highly detailed Lindbergh, a story of a mouse with a yen for flight. A little bit The Arrival, a little bit An American Tale and a little bit steampunk via Beatrix Potter, it was his hyper realistic animals placed in extraordinary circumstances that stayed with young readers. In Moletown that level of detail and attention is there, but the moles have a far more cartoonish feel to them. This is not to say that they don’t look like moles, every inch of them. Yet Kuhlmann has simplified his hyper-realistic renderings of animals and traded that attention in for set designs and landscapes. Here he plays with perspective, plunging us down into the heart of the moles’ mining operation, the scaffolding twisting around and around, down and down. Sharp eyed spotters will note other spreads where the stop signs are shaped like mole claws and the trains go vertically as well as horizontally. The details are there to an elegant degree, but the feel is different from Lindbergh certainly (as is the length of the piece).

One of the most amazing aspects of the book is the sense of time passing. In the early days of Moletown you see the immigrants arriving, looking very much like the European immigrants of the late 19th century. As time passes you see moles in Wright Brothers era caps, trench coats and fedoras of the 40s, a possible homage to the MTV image of the 80s (complete with Nintendo video game remotes), and finally the iPods and wind farms of the current age.

One of the most amazing aspects of the book is the sense of time passing. In the early days of Moletown you see the immigrants arriving, looking very much like the European immigrants of the late 19th century. As time passes you see moles in Wright Brothers era caps, trench coats and fedoras of the 40s, a possible homage to the MTV image of the 80s (complete with Nintendo video game remotes), and finally the iPods and wind farms of the current age.

Many European artists find it difficult to break into the American market due to the fact that their art contains a distinctly “foreign” feel. Kuhlmann’s advantage here is that while it is easy enough to believe that the images in this story originated in Germany, there is nothing distinctly “other” about the book . . . at first. It’s only with multiple readings that you begin to notice the elements that probably could not have begun here in the States. For example, in more than one instance you’ll see a mole smoking. This is by no means the focus of the book, and you would have to look somewhat hard to find such moments, but I have seen American parents go ballistic over far lesser crimes in picture book illustration, so I’ve no doubt the occasional library patron will become incensed over what they believe to be the promotion of cigarettes. Other hints that the book is German? Well, I could be wrong but this may well be the only picture book you’ll find on the market today containing a two-page spread dedicated to accountancy.

One interesting thing about the book is the fact that the ending that we so deeply desire is embedded not in the book itself but in its endpapers. The final text in the book reads, “Many generations later, the moles’ green meadow had completely disappeared. Almost.” Turn the page and rather than provide a verbal explanation, the book gives us a glimpse of a series of photographs alongside an article from The Moletown Times which reads, “Agreement on Green”. The pictures show steps taken to preserve the environment and restore the meadow. I didn’t mind this method of summing up the steps taken to correct the past. Yet more interesting to me, by far, was how the book lets the reader reach their own slow realization that the seemingly inevitable trudge of technological advances and population increases are, in fact, detrimental. That picture at the beginning of the book of the immigrants arriving in Moletown, to an American reader, strikes you as a symbol of freedom from oppression and hardship. And because Kuhlmann keeps the book almost entirely wordless from start to finish, the glimpses of the meadow in its downward slide towards decay are shown without commentary. It’s up to the reader to realize that something has gone very wrong. How many will actually make that leap will be interesting to see.

One interesting thing about the book is the fact that the ending that we so deeply desire is embedded not in the book itself but in its endpapers. The final text in the book reads, “Many generations later, the moles’ green meadow had completely disappeared. Almost.” Turn the page and rather than provide a verbal explanation, the book gives us a glimpse of a series of photographs alongside an article from The Moletown Times which reads, “Agreement on Green”. The pictures show steps taken to preserve the environment and restore the meadow. I didn’t mind this method of summing up the steps taken to correct the past. Yet more interesting to me, by far, was how the book lets the reader reach their own slow realization that the seemingly inevitable trudge of technological advances and population increases are, in fact, detrimental. That picture at the beginning of the book of the immigrants arriving in Moletown, to an American reader, strikes you as a symbol of freedom from oppression and hardship. And because Kuhlmann keeps the book almost entirely wordless from start to finish, the glimpses of the meadow in its downward slide towards decay are shown without commentary. It’s up to the reader to realize that something has gone very wrong. How many will actually make that leap will be interesting to see.

Finding books to compare this one to can be difficult. The overall feeling I got was like the one in The Rabbits by John Marsden. But where that was a story of a culture being systematically destroyed, this has a sweeter if no less destructive feel. The Lorax hits the same environmental notes, but Moletown is the subtler of the two since it makes the reader implicit in the enjoyment one derives from Moletown’s culture (and from the fact that it’s a world that feels very much like our own). The best way to describe the story is to say that it’s a combination of the two, with a hopeful endnote all its own. Like all imports, it runs its greatest risk in becomes a forgotten piece since it can’t win many of our American children’s book awards. That said, I have faith that teachers, parents, and students will find in it a new approach to tackling the tricky subject of mass consumption vs. environmental action. Explicit in its message. Subtle in its presentation. In short, a beaut.

On shelves October 1st.

Like This? Then Try:

The Lorax by Dr. Seuss

The Rabbits by John Marsden, illustrated by Shaun Tan

The Promise by Nicola Davies

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 7/7/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Jessixa Bagley,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 picture books,

2015 reviews,

Reviews,

picture books,

death,

grief,

Best Books,

Add a tag

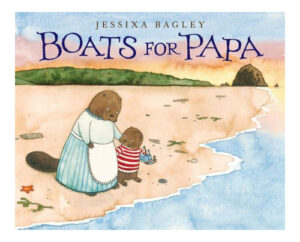

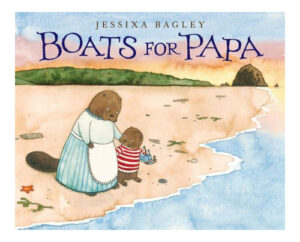

Boats for Papa

Boats for Papa

By Jessixa Bagley

Roaring Brook Press (an imprint of Macmillan)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-1626720398

Ages 4-7

On shelves now

So I’m a snob. A children’s literature snob. I accept this about myself. I do not embrace it, but I can at least acknowledge it and, at times, fight against it as much as I am able. Truth be told, it’s a weird thing to get all snobby about. People are more inclined to understand your point of view when you’re a snob about fine china or wines or bone structure. They are somewhat confused when you scoff at their copy of Another Monster at the End of This Book since it is clearly a sad sequel of the original Jon Stone classic (and do NOT even try to convince me that he was the author of that Elmo-related monstrosity because I think better of him than that). Like I say. Kid book snobbery won’t get you all that far in this life. And that’s too bad because I’ve got LOADS of the stuff swimming between my corpuscles. Just take my initial reaction to Jessixa Bagley’s Boats for Papa. I took one glance at the cover and dismissed it, just like that. I’ll explain precisely why I did so in a minute, but right there it was my gut reaction at work. I have pretty good gut reactions and 99% of the time they’re on target. Not in this case, though. Because once I sat down and read it and watched other people read it, I realized that I had something very special on my hands. Free of overblown sentiment and crass pandering, this book’s the real deal. Simultaneously wrenching and healing.

Buckley and his mama are just two little beavers squeaking out an existence in a small wooden house by the sea. Buckley loves working with his hands (paws?) and is particularly good at turning driftwood into boats. One day it occurs to him to send his best boats off into the sea with little notes that read, “For Papa. Love, Buckley”. Buckley misses his papa, you see, and this is the closest he can get to sending him some kind of a message. As Buckley gets better, the boats get more elaborate. Finally, one day a year later, he runs into his house to write a note for papa, when he notices that his mother has left her desk open. Inside is every single boat he ever sent to his papa. Realizing what has happened, Buckley makes a significant choice with this latest seagoing vessel. One that his mama is sure to see and understand.

The danger with this book is determining whether or not it slips into Love You Forever territory. Which is to say, does it speak more to adults than to kids. You get a fair number of picture books with varying degrees of sentimentality out there every year. On the low end of the spectrum is Love You Forever, on the high end Blueberry Girl and somewhere in the middle are books like Someday by Alison McGhee. Some of these can be great books, but they’re so clearly not for kids. And when I realized that Boats for Papa was a weeper my alarm bells went off. If adults are falling over themselves to grab handkerchiefs when they get to the story’s end, surely children would be distinctly uninterested. Yet Bagley isn’t addressing adults with this story. The focus is on how one deals with life after someone beloved is gone. Adults get this instantly because they know precisely what it is to lose someone (or they can guess). Kids, on the other hand, may sometimes have that understanding but a lot of the time it’s foreign to them. And so Buckley’s hobbies are just the marks of a good story. I suspect few kids would walk away from this saying the book was uninteresting to them. It seems to strike just the right chord.

It is also a book that meets multiple needs. For some adult readers, this is a dead daddy book. But upon closer inspection you realize that it’s far broader than that. This could be a book about a father serving his time overseas. It could be about divorced parents (it mentions that mama misses papa, and that’s not an untrue sentiment in some family divorce situations). It could have said outright that Buckley’s father had passed away (ala Emmet Otter’s Jugband Christmas which this keeps reminding me of) but by keeping it purposefully vague we are allowed to read far more into the book’s message than we could have if it was just another dead parent title.

Finally, it is Bagley’s writing that wins the reader over. Look at how ecumenical she is with her wordplay. The very first sentences in the book reads, “Buckley and his mama lived in a small wooden house by the sea. They didn’t have much, but they always had each other.” There’s not a syllable wasted there. Not a letter out of place. That succinct quality carries throughout the rest of the book. There is one moment late in the game where Buckley says, “And thank you for making every day so wonderful too” that strains against the bonds of sentimentality, but it never quite topples over. That’s Bagley’s secret. We get the most emotionally involved in those picture books that give us space to fill in our own lives, backgrounds, understandings and baggage. The single note reading, “For Mama / Love, Buckley” works because those are the only words on the page. We don’t need anything else after that.

As I age I’ve grown very interested in picture books that touch on the nature of grace. “Grace” is, in this case, defined as a state of being that forgives absolutely. Picture books capable of conjuring up very real feelings of resentment in their young readers only to diffuse the issue with a moment of pure forgiveness are, needless to say, rare. Big Red Lollipop by Rukhsana Khan was one of the few I could mention off the top of my head. I shall now add Boats for Papa to that enormously short list. You see, (and here I’m going to call out “SPOILER ALERT” for those of you who care about that sort of thing) for me the moment when Buckley finds his boats in his mother’s desk and realizes that she has kept this secret from him is a moment of truth. Bagley is setting you up to assume that there will be a reckoning of some sort when she writes, “They had never reached Papa”. And it is here that the young reader can stop and pause and consider how they would react in this case. I’d wager quite a few of them would be incensed. I mean, this is a clear-cut case of an adult lying to a child, right? But Bagley has placed Buckley on a precipice and given him a bit of perspective. Maybe I read too much into this scene, but I think that if Buckley had discovered these boats when he was first launching them, almost a full year before, then yes he would have been angry. But after a year of sending them to his Papa, he has grown. He realizes that his mother has been taking care of him all this time. For once, he has a chance to take care of her, even if it is in a very childlike manner. He’s telling her point blank that he knows that she’s been trying to protect him and that he loves her. Grace.

Now my adult friends pointed out that one could read Buckley’s note as a sting. That he sent it to say “GOTCHA!” They say that once a book is outside of an author’s hands, it can be interpreted by the readership in any number of ways never intended by the original writer. For my part, I think that kind of a reading is very adult. I could be wrong but I think kids will read the ending with the loving feel that was intended from the start.

When I showed this book to a friend who was a recent Seattle transplant, he pointed out to me that the coastline appearing in this book is entirely Pacific Northwest based. I think that was the moment I realized that I had done a 180 on the art. Remember when I mentioned that I didn’t much care for the cover when I first saw it? Well, fortunately I have instituted a system whereby I read every single picture book I am sent on my lunch breaks. Once I got past the cover I realized that it was the book jacket that was the entire problem. There’s something about it that looks oddly cheap. Inside, Bagley’s watercolors take on a life of their own. Notice how the driftwood on the front endpapers mirrors the image of Buckley displaying his driftwood boats on the back endpapers. See how Buckley manages to use her watercolors to their best advantage, from the tide hungry sand on the beach to the slate colored sky to the waves breaking repeatedly onto the shore. Perspective shifts constantly. You might be staring at a beach covered in the detritus of the waves on one two-page spread, only to have the images scale back and exist in a sea of white space on the next. The best image, by far, is the last though. That’s when Bagley makes the calculated step of turning YOU, the reader, into Mama. You are holding the boat. You are holding the note. And you know. You know.

I like it when a picture book wins me over. When I can get past my own personal bugaboos and see it for what it really is. Emotional resonance in literature for little kids is difficult to attain. It requires a certain amount of talent, both on the part of the author and their editor. In Boats for Papa we’ve a picture book that doesn’t go for the cheap emotional tug. It comes by its tears honestly. There’s some kind of deep and abiding truth to it. Give me a couple more years and maybe I’ll get to the bottom of what’s really going on here. But before that occurs, I’m going to read it with my kids. Even children who have never experienced the loss of a parent will understand what’s going on in this story on some level. Uncomplicated and wholly original, this is one debut that shoots out of the starting gate full throttle, never looking back. A winner.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Misc: Be sure to check out this profile of Jessixa Bagley over at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 6/14/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

multicultural,

Reviews,

picture books,

Vietnam,

multicultural picture books,

Creston Books,

Best Books of 2015,

2015 picture books,

2015 reviews,

diverse picture books,

Add a tag

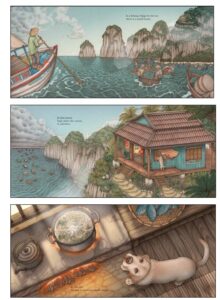

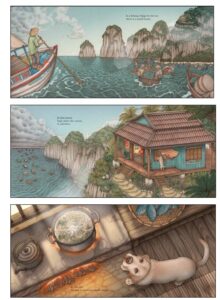

In a Village by the Sea

In a Village by the Sea

By Muon Van

Illustrated by April Chu

Creston Books

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-939547-156

Ages 4-6

On shelves now

We talk a lot about wanting a diverse selection of picture books on our library, bookstore, and home shelves, but it seems to me that the key to giving kids a broad view of the wider world (which is the ultimate effect of reading literature about people outside your immediate social, economic, and racial circle) is finding books that go into formerly familiar territory and then give the final product an original spin. For example, I was just telling a colleague the other day that true diverse literature for kids will never come to pass until we’ve a wide variety of gross out books about kids of different races, abilities, genders, etc. That’s one way of reaching parity. Another way would be to tackle that age old form so familiar to kids of centuries past; nursery rhymes. Now we’ve already seen the greatest nursery rhyme collection of the 21st century hit our shelves earlier this year (Over the Hills and Far Away, edited by Elizabeth Hammill) and that’s great. That’s swell. That’s super. But one single book does not a nursery rhyme collection make. Now I admit freely that Muon Van and April Chu’s In a Village by the Sea is not technically a nursery rhyme in the classic sense of the term. However, Merriam-Webster defines the form as “a short rhyme for children that often tells a story.” If that broad definition is allowed then I submit “In a Village by the Sea” as a true, remarkable, wonderful, evocative, modern, diverse, ultimately beautiful nursery rhyme for the new Millennium. Lord knows we could always use more. Lord knows this book deserves all the attention it can get.

On the title page a single brown cricket grabs a rolled piece of parchment, an array of watercolor paints and paintbrushes spread below her (to say nothing of two soon-to-be-necessary screws). Turn the page and there a fisherman loads his boat in the predawn hour of the day, his dog attentive but not following. As he pushes off, surrounded by other fishermen, and looks behind him to view his receding seaside home we read, “In a fishing village by the sea there is a small house.” We zoom in. “In that house high above the waves is a kitchen.” The dog is now walking into the house, bold as brass, and as the story continues we meet the woman and child inside. We also meet that same industrious cricket from the title page, painting a scene in which a fisherman combats the elements, comforted by the picture of his family he keeps beside him. And in another picture is his village, and his house, and in that house is his family, waiting to greet him safely home. Set in Vietnam, the book has all the rhythms and cadence of the most classic rhyme.

When it comes to rhymes, I feel that folks tend to be fairly familiar with the cumulative form. Best highlighted in nursery rhymes likes “The House That Jack Built” it’s the kind of storytelling that builds and builds, always repeating the elements that came before. Less celebrated, perhaps, is the nesting rhyme. Described in Using Poetry Across the Curriculum: A Whole Language Approach by Barbara Chatton, the author explains that children love patterns. “The simplest pattern is a series in which objects are placed in some kind of order. This order might be from smallest to largest, like the Russian nesting dolls, or a range of height, length, or width . . . A nursery rhyme using the ‘nesting’ pattern is ‘This Is the Key to My Kingdom’.” Indeed, it was that very poem I thought of first when I read In a Village by the Sea. In the story you keep going deeper and deeper into the narrative, an act that inevitably raises questions.

When it comes to rhymes, I feel that folks tend to be fairly familiar with the cumulative form. Best highlighted in nursery rhymes likes “The House That Jack Built” it’s the kind of storytelling that builds and builds, always repeating the elements that came before. Less celebrated, perhaps, is the nesting rhyme. Described in Using Poetry Across the Curriculum: A Whole Language Approach by Barbara Chatton, the author explains that children love patterns. “The simplest pattern is a series in which objects are placed in some kind of order. This order might be from smallest to largest, like the Russian nesting dolls, or a range of height, length, or width . . . A nursery rhyme using the ‘nesting’ pattern is ‘This Is the Key to My Kingdom’.” Indeed, it was that very poem I thought of first when I read In a Village by the Sea. In the story you keep going deeper and deeper into the narrative, an act that inevitably raises questions.

Part of what I like so much about the storytelling in this book is not just its nesting nature, but also the questions it inspires in the child reader. At first we’re working entirely in the realm of reality with a village, a fisherman, his wife, and their child. But then when we dive down into the cricket’s realm we see that it is painting a magnificent storm with vast waves that appear to be a kind of ode to that famous Japanese print, “The Great Wave Off Kanagawa”. When we get into that painting and find that our fisherman is there and in dire straits we begin to wonder what is and isn’t real. Artist April Chu runs with that uncertainty well. Notice that as the fisherman sits in his boat with the storm overhead, possibly worrying for his own safety, in his hands he holds a box. In that box is a photo of his wife and child, his village, and what appears to be a small wooden carving of a little cricket. The image of the village contains a house and (this isn’t mentioned in the text) we appear to zoom into that picture and that house where the sky is blue and the sea is calm. So what is going on precisely? Is it all a clever cricket’s imaginings or are each of these images true in some way? I love the conversation starter nature of this book. Younger kids might take the events at face value. Older kids might begin to enmesh themselves into the layered M.C. Escher-ness of the enterprise. Whatever draws them in, Van and Chu have created a melodic visual stunner. No mean feat.

For the record, the final image in this book is seemingly not of the cricket’s original painting but of the fisherman heading home on a calm sea to a distant home. What’s so interesting about the painting is that if you compare it to the cricket’s previous one (of the storm) you can see that the curls and folds of the paper are identical. This is the same canvass the cricket was working on before. Only the image has changed. How is this possible? The answer lies in what the cricket is signing on the painting’s lower right-hand corner. “AC”. April Chu. Artist as small brown cricket. I love it.

So who precisely is April Chu? Read her biography at the back and you see that she began her career as an architect, a fact that in part explains the sheer level of detail at work in tandem with this simple text. Let us be clear that while the writing in this book is engaging on a couple different levels, with the wrong artist it wouldn’t have worked half as well as it now does. Chu knows how to take a single story from a blue skied mellow to a wrath of the gods storm center and then back again to a sweet peach colored sunset. She also does a good dog. I’ll say it. The yellow lab in this book is practically the book’s hero as we follow it in and out of the house. He’s even in his master’s family photograph.

So who precisely is April Chu? Read her biography at the back and you see that she began her career as an architect, a fact that in part explains the sheer level of detail at work in tandem with this simple text. Let us be clear that while the writing in this book is engaging on a couple different levels, with the wrong artist it wouldn’t have worked half as well as it now does. Chu knows how to take a single story from a blue skied mellow to a wrath of the gods storm center and then back again to a sweet peach colored sunset. She also does a good dog. I’ll say it. The yellow lab in this book is practically the book’s hero as we follow it in and out of the house. He’s even in his master’s family photograph.

One question that occurred to me as I read the book was why I immediately thought of it as contemporary. No date accompanies the text. No elements that plant it firmly in one time or another. The text is lilting and lovely but doesn’t have anything so jarring as a 21st century iPhone or ear bud lurking in the corners. In Van’s Author’s Note at the end she mentions that much of the inspiration for the tale was based on both her family’s ancestral village in Central Vietnam and her father’s work, and mother’s experiences, after they immigrated to American shores. By logic, then, the book should have a bit of a historical bent to it. Yet people still fish in villages. Families still wait for the fisherman to return to shore. And when I looked at April Chu’s meticulous art I took in the clothing more than anything else. The mom’s rubber band in her hair. The cut of the neck of her shirt. The other fishermen and their shirts and the colors of the father’s. Then there was the way the dishes stack up next to the stove. I dunno. It sure looks like it’s set in a village today. But these things can be hard to judge.

There’s this real feeling that meta picture books that play with their format and turn the fourth wall into rubble are relatively new. But if we look at rhymes like “This Is the Key to the Kingdom”, we can see how they were toying with our notion of how to tell a story in a new way long long before old Stinky Cheese Man. I guess what I like most about “In a Village by the Sea” is how to deals with this duality. It manages to feel old and new all at the same time. It reads like something classic but it looks and feels like something entirely original. A great read aloud, beautifully illustrated, destined to become beloved of parents, librarians, and kids themselves for years to come. This is a book worth discovering.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent by publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 4/24/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

folktale review,

picture book folktales,

Inhabit Media,

Neil Christopher,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 picture books,

2015 reviews,

2015 folktales,

Jim Nelson,

Reviews,

Best Books,

Inuit,

Add a tag

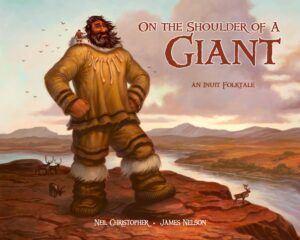

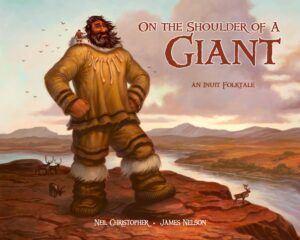

On the Shoulder of a Giant: An Inuit Folktale

On the Shoulder of a Giant: An Inuit Folktale

By Neil Christopher

Illustrated by Jim Nelson

Inhabit Media

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-77227-002-0

Ages 4-7

On shelves now

My daughter is afraid of giants. She’s three so this isn’t exactly out of the norm. However, it does cut out a portion of her potential reading material. Not all giants fall under this stricture, mind you. She doesn’t seem to have any problem with the guys in Giant Dance Party and “nice” giants in general get a pass. Still, we’ve had to put the kibosh on stories like Jack and the Beanstalk and anything else where getting devoured is a serious threat. Finding books about good giants is therefore an imperative and it walks hand in hand with my perpetual search for amazing folktales. Every year I scour the publishers for anything resembling a folktale. In the old days they were plentiful and you could have your pick of the offerings. These days, the big publishers hardly want to touch the stuff, so it’s up to the smaller guys to fill in the gaps. And no one stands as a better folktale gap filler than the Inuit owned company Inhabit Media. Producing consistently high quality books for kids, one of their latest titles is the drop dead gorgeous On the Shoulder of a Giant. Funny, attractive, and a straight up accurate folktale, this is children’s book publishing at its best. And as for the giant himself, my daughter has never run into a guy like him before.

“…if there is only one Arctic giant story you take the time to learn about, this is the one to remember.” Which giant? Why Inukpak, of course! Large (even for a giant) our story recounts Inukpak’s various deeds. He could stride across wide rivers, and fish full whales out of the sea. In his travels, there was one day when Inukpak ran across a little human hunter. Misunderstanding the man to be a small child, the giant promptly adopted him. And since the man was no fool he understood that when a giant claims you, you have little recourse but to accept. He went along with it. The giant fished their dinner and when a polar bear threatened the hunter Inukpak flicked it away like it was no more than a baby fox or lemming. In time the two became good friends and had many adventures together. Backmatter called “More About Arctic Giants” explains at length about their size, their fights, their relationship to the giant polar bears, and how they may still be around – maybe right under your feet!

I’ve read a lot of giant fare in my day and I have never encountered a tale quite like this. Not that the story really goes much of anywhere. The only true question you find yourself asking as you read the tale is whether or not the hunter will ever confess to the giant that he isn’t actually a child. But as I read and reread the tale, I came to love the humor of the tale. Combined with the art, it’s a lighthearted story. In fact, one of the problems is also a point in its favor. When you get to the end of the tale and are told that Inukpak and the hunter had many adventures, you want to read those immediately. One can only hope that Mr. Christopher and Mr. Nelson will join forces yet again someday to bring us more of this unique and delightful duo.

I’m no expert on Inuit culture so it doesn’t hurt that in the creation of “On the Shoulder of a Giant” author Neil Christopher has the distinction of having spent the last sixteen years of his life recording and preserving traditional Inuit stories. Having seen a fair number of books of Native American folktales where the selection of the tales is offhanded at best, the care with which Christopher chooses to imbue his book with life and vitality is notable. The book reads aloud beautifully, and would serve a librarian well if they were told to read aloud a folktale to a group. Likewise, the pictures are visible from long distances. This story begs for a big audience.

I’ve seen a lot of small presses in my day. Quality can vary considerably from place to place. Often I’ll see a small publisher bring to life a folktale but then skimp on the artist chosen to bring the story to life. It’s a sad but common occurrence. So common, in fact, that when it doesn’t happen I’m shocked out of my gourd. Inhabit Media is one of those rare few that take illustration very seriously. Each of their books looks good. Looks not just professional but like something you’d want to take home for yourself. On the Shoulder of a Giant is no exception. This time the artist tapped was freelance illustrator Jim Nelson. He’s based out of Chicago and his art has included stuff like Magic the Gathering cards and the like. He is not, at first glance, the kind of artist you’d tap for a book of this sort. After all, he works with a digital palette creating images that would seemingly be more at home in a comic book than a classic Inuit folktale. Yet what are folktales but proto-superhero stories? What are superhero comics but just modern myths? Inukpak is larger than life and, as such, he demands an artist who can bring his physicality to bear upon the narrative. When he’s fishing for whales I wanna see that sucker fighting back. When he strides across great plains I wanna be there beside him. Nelson feeds that need.

Since Nelson isn’t Inuit himself, the question of how authentic his art may be arises. I am willing to believe, however, that any book published by a company operating with the sole intent to “preserve and promote the stories, knowledge and talent of Inuit and northern Canada” is going to have put the book through a strict vetting process. It would not be ridiculous to think that Nelson’s editor informed him of where to research classic Inuit clothing and landscapes. I loved every inch of Nelson’s art on this story but it was the backmatter that really did it for me. There’s a section that is able to show the difference in size between a inukpasugjuit (“great giant”), a inugaruligasugjuk (“lesser giant”), and a regular human that does a brilliant job of showing scale. That goes for the nanurluit (giant polar bear) in one of the pictures, relentlessly tracking two tiny hunters in their boats. But it is the final shot of a sleeping giant under the mountains as people walk on to of him, oblivious that will really pique young imaginations.

I’m not saying that On the Shoulder of a Giant has the ability to single-handedly rid my daughter of her fear of giants as a whole. It does, however, stand out as a singularly fun and interesting take on the whole giant genre. There’s nothing on my library shelves that sounds or feels or looks quite like this book. It could well be the poster child for the ways in which small publishers should examine and publish classic folktales. Beautiful and strange with a flavor all its own, this is one little book that yields big rewards. Fantastico.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 3/30/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Greenwillow,

Michael Hall,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 picture books,

2015 reviews,

Reviews,

picture books,

Harper Collins,

Best Books,

Add a tag

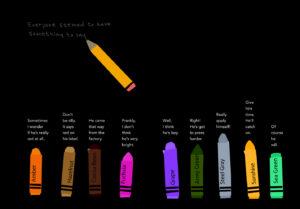

Red: A Crayon’s Story

Red: A Crayon’s Story

By Michael Hall

Greenwillow (an imprint of Harper Collins)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-0062252074

Ages 3-6

On shelves now

Almost since their very conception children’s books were meant to teach and inform on the one hand, and to inform one’s moral fiber on the other. Why who can forget that catchy little 1730 ditty from The Childe’s Guide that read, “The idle Fool / Is whipt at School”? It’s got a beat and you can dance to it! And as the centuries have passed children’s books continue to teach and instruct. Peter Rabbit takes an illicit nosh and loses his fancy duds. Pinocchio stretches the truth a little and ends up with a prominent proboscis. Even parents who are sure to fill their shelves with the subversive naughtiness of Max, David, and Eloise are still inclined to indulge in a bit of subterfuge bibliotherapy when their little darling starts biting / hitting / swearing at the neighbors. Instruction, however, is a terribly difficult thing to do in a children’s book. It takes skill and a gentle hand. When Sophie Gets Angry . . . Really Really Angry works because the point of the book is couched in beautiful, lively, eye-popping art, and a story that shows rather than tells. But for every Sophie there are a hundred didactic tracts that some poor child somewhere is being forced to swallow dry. What a relief then to run across Red: A Crayon’s Story. It’s making a point, no doubt about it. But that point is made with a gentle hand and an interesting story, giving the reader the not unpleasant sensation that even if they didn’t get the point of the tale on a first reading, something about the book has seeped deep into their very core. Clever and wry, Hall dips a toe into moral waters and comes out swimming. Sublime.

“He was red. But he wasn’t very good at it.” When a blue crayon in a wrapper labeled “Red” finds himself failing over and over again, everyone around him has an opinion on the matter. Maybe he needs to mix with the other kids more (only, when he does his orange turns out to be green instead). Maybe he just needs more practice. Maybe his wrapper’s not tight enough. Maybe it’s TOO tight. Maybe he’s got to press harder or be sharper. It really isn’t until a new crayon asks him to paint a blue sea that he comes to the shocking realization. In spite of what his wrapper might say, he isn’t red at all. He’s blue! And once that’s clear, everything else falls into place.

A school librarian friend of mine discussed this book with some school age children not too long ago. According to her, their conversation got into some interesting territory. Amongst themselves they questioned why the crayon got the reaction that he did. One kid said it was the fault of the factory that had labeled him. Another kid countered that no, it was the fault of the other crayons for not accepting him from the start. And then one kid wondered why the crayon needed a label in the first place. Now I don’t want to go about pointing out the obvious here but basically these kids figured out the whole book and rendered this review, for all intents and purposes, moot. They got the book. They understand the book. They should be the ones presenting the book.

A school librarian friend of mine discussed this book with some school age children not too long ago. According to her, their conversation got into some interesting territory. Amongst themselves they questioned why the crayon got the reaction that he did. One kid said it was the fault of the factory that had labeled him. Another kid countered that no, it was the fault of the other crayons for not accepting him from the start. And then one kid wondered why the crayon needed a label in the first place. Now I don’t want to go about pointing out the obvious here but basically these kids figured out the whole book and rendered this review, for all intents and purposes, moot. They got the book. They understand the book. They should be the ones presenting the book.

Because you see when I first encountered this story I applied my very very adult (and very very limited) interpretation to it. A first read and I was convinced that it was a transgender coming-of-age narrative except with, y’know, waxy drawing materials. And I’m not saying that isn’t a legitimate way to read the book, but it’s also a very limited reading. I mean, let’s face it. If Mr. Hall had meant to book to be JUST about transgender kids, wouldn’t it have been a blue crayon in a pink wrapper? No, Hall’s story is applicable to a wide range of people who find themselves incorrectly “labeled”. The ones who are told that they’re just not trying hard enough, even when it’s clear that the usual rules don’t apply. We’ve all known someone like that in our lives before. Sometimes they’re lucky in the way that Red here is lucky and they meet someone who helps to show them the way. Sometimes they help themselves. And sometimes there is no help and the story takes a much sadder turn. I think of those kids, and then I read the ending of “Red” again. It doesn’t help their situation much, but it makes me feel better.

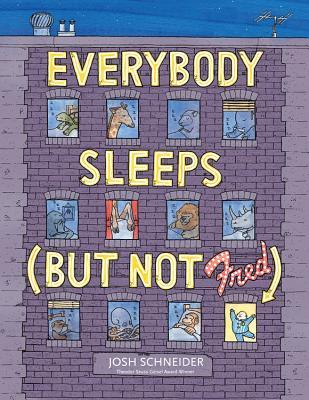

This isn’t my first time at the Michael Hall rodeo, by the way. I liked My Heart Is Like a Zoo, enjoyed Perfect Square, took to Cat Tale, and noted It’s an Orange Aardvark It’s funny, but in a way, these all felt like a prelude to Red. As with those books, Hall pays his customary attention to color and shape. Like Perfect Square he even mucks with our understood definitions. But while those books were all pleasing to the eye, Red makes a sudden lunge for hearts and minds as well. That it succeeds is certainly worth noting.