As I contemplated cracking on with my novel this morning – I’m only on Chapter Three – I had a comforting thought. The exact words in my head were Synopsis as friend. My mind’s circuitry led me straight to a case study from my long gone life as a marketer. The subject was dog food.

For ten years I was a proper PAYE employee, selling the likes of frozen food, tennis shoes and booze. For the next ten years I was freelance, selling money in the form of mortgages and investments. At some point I was invited to give a guest lecture at the Chartered Institute of Marketing. Given that I was seven months pregnant, I probably should have declined. Instead I pulled on a pair of black trousers with an oh-so-attractive stretchy panel fetchingly topped by an elastic waistband (for that little known waist that is in fact directly beneath your breasts), buttoned the matching black maternity waistcoat (what joker thought of that) and drove to Cookham.

For ten years I was a proper PAYE employee, selling the likes of frozen food, tennis shoes and booze. For the next ten years I was freelance, selling money in the form of mortgages and investments. At some point I was invited to give a guest lecture at the Chartered Institute of Marketing. Given that I was seven months pregnant, I probably should have declined. Instead I pulled on a pair of black trousers with an oh-so-attractive stretchy panel fetchingly topped by an elastic waistband (for that little known waist that is in fact directly beneath your breasts), buttoned the matching black maternity waistcoat (what joker thought of that) and drove to Cookham.

I wasn’t nervous, until I opened my mouth and realised that my lung capacity, whilst adequate for conversations where you only have every other turn and the person is close by, wasn’t up to the job. I cut short my introduction, offering the delegates a chance to say a little about themselves while I recovered my composure.

My subject was segmentation. Bread and butter stuff. I had all sorts of examples from the world known as FMCG (fast moving consumer goods), from retail and from financial services. All I had to do was teach the theory, show examples – the brilliant dog food slides were ready and waiting – and then relate it to the fields they were working in. I could do that with or without oxygen.

My subject was segmentation. Bread and butter stuff. I had all sorts of examples from the world known as FMCG (fast moving consumer goods), from retail and from financial services. All I had to do was teach the theory, show examples – the brilliant dog food slides were ready and waiting – and then relate it to the fields they were working in. I could do that with or without oxygen.

The first attendee mumbled her name and said that she worked on treated mosquito nets. My mind gave a sarcastic ‘yippee!’ Never mind. The others were bound to be working on cars, shampoo, biscuits . . . something I could relate to.

The conch was passed round the room. My confidence ebbed. My smile became as fixed and unresponsive as my twenty-something pupils.

It turned out that I had a global monopoly on marketers of mosquito related products.

Inside I did the equivalent of a refusal at Becher’s Brook.

Whether it was the peppering of the content with irritating little breaths, the hideousness of my maternity waistcoat or my lack of engagement with the mosquito market, by the time I got to the segmentation of the dog food market, I’d lost them. A shame, because it was my favourite part.

Here’s the gist:

Categorising dog food in terms of form – dry, wet, raw – or flavour – lamb, rabbit, chicken – didn’t help marketers understand how to make their products attractive to dog owners. Nor did using the breed, age or size of dog. Research showed that the most meaningful way of sorting the market was by looking at how dog owners thought about their dogs.

Four segments were identified that most influenced the type of dog food chosen:

Dog as grandchild – indulgence

Dog as child – love

Dog as child – loveDog as friend – health and nutrition

Dog as dog – cheap and convenient.

My audience woke up slightly. Proof that a pet can always be relied on to liven things up, be it in business or school visits. We had our first interaction of any length, a welcome reprieve for my pulmonary gas exchange. The treated net marketers had never considered the relationship between dog and master.

Had they not read The Call of the Wild? Seen Bill Sykes mistreat Bull’s Eye? Or Hagrid berate cowardly Fang? Timmy was surely as much a friend as Anne, Dick, Julian and George.

They eagerly volunteered product names and quickly slotted them into the four segments.

Cesar Mini Fillets in a foil tray – Dog as grandchild

Asda Smartprice Dog Meal. – Dog as dog

Pedigree Chum Chicken – the clues in the name . . .

In what was overall a pretty grey-with-clouds lecture, I enjoyed the little spell of sunshine. Motivation wasn’t something mosquito experts thought a lot about. They thought about geography and insects and shelter and disease and mosquito net fixing kits. They didn’t think about what might be on the mind of the traveller, setting off alone to try and find traces of the Hairy-nosed Otter in Borneo, or maybe the traveller’s nervous father, buying the very best treated mosquito net for his passionate but impractical son.

In what was overall a pretty grey-with-clouds lecture, I enjoyed the little spell of sunshine. Motivation wasn’t something mosquito experts thought a lot about. They thought about geography and insects and shelter and disease and mosquito net fixing kits. They didn’t think about what might be on the mind of the traveller, setting off alone to try and find traces of the Hairy-nosed Otter in Borneo, or maybe the traveller’s nervous father, buying the very best treated mosquito net for his passionate but impractical son.

Marketers often end up segmenting by demographics e.g. age, gender, income, despite the power of psychographics like motivation, personality and attitude. Perhaps writers should lecture at the Chartered Institute of Marketing instead . . .

Quite why my inner voice chose the words Synopsis as friend, inextricably linked in my hippocampus to Dog as friend, who knows, but it made me reflect on my changed relationship with synopses.

My first few books grew in a free spirit sort of way, meandering towards a vague nirvana shrouded in uncertainty. The synopses written afterwards, if at all.

This was: Synopsis as bureaucrat.

My new book,

Hacked, out in November, was the product of a synopsis I HAD to write because the publisher, Piccadilly Press, was interested in an idea I’d mooted and wanted it fleshed out.

This was: Synopsis as unwanted dependant.

I developed the beginning, middle and end of the story, my lovely publisher made a few suggestions and then I forgot about the four-page plan until there was a problem, at which point I reluctantly referred to it.

The synopsis for the sequel, however, is printed out and has its own space on my desk. It feels reassuring. Trustworthy, but not prescriptive.

857 words in, with 50 000 ish to go, I’m glad that I’m not alone.

This is: Synopsis as friend

I even enjoyed the discipline of writing it.

Tracy Alexander

By Anatoly Liberman

If I find enough material, I may tell several stories about how after multiple failures the ultimate origin of a common English word has been found to (almost) everybody’s satisfaction. The opening chapter in my prospective Decameron will deal with pedigree, which surfaced in English texts in the early fifteenth century. Many competing spellings have been recorded: pedigre, pedigrew, petigree, and their variants with -ee, -tt-, and -y- (the latter in place of -i-). Although no word resembles it, the French or Latin origin was proposed early on. The first students of English etymology realized that pedigree must be a compound and tried to recover the disguised elements. Strangely, unlike cap-a-pe(e), pedigree has never been spelled as a word group.

This is indeed a pedigree.

Perhaps those elements are

par and

degrés “by degrees,” with an allusion to descending from one generation to another? Not a fanciful guess, but what happened to

r, the last sound of

par or

per? Or is the sought-for etymon

degrés des pères “the rank or degree of forefathers”? But in

pedigree the proposed elements appear in reverse order! Or Latin

petendo gradum “deriving (seeking, pursuing) the descent”? Or

a pede gradus, “like the Jesse window at Dorchester or others of that kind” (with reference to the Jesse tree showing the genealogy of Jesus)? In that etymology,

pede, the dative of Latin

pes “foot,” was taken to mean the stem of the tree; an analog would be German

Stammbaum “genealogy, family tree, pedigree,” literally, “stem tree.” Or

pied de greffe, that is, “the stem of the graft” = “the stem on which later branches were grafted”? Or “the table of degrees” (= of relationships)? Or

pee de crue “the foot of the increase”? Or Greek

país “child” and Latin

gradus “degree”? C. A. F. Mahn, the reviser of the 1864 edition of Webster’s dictionary, who mentioned this etymology in a special publication (I have not seen it anywhere else), referred to A. Wagner. Such irritating references were all over the place in the past. I have no clue to the source and would be grateful to those of our readers who could tell me where A. Wagner (and which of the great multitude of A. Wagners) proposed that truly hopeless etymology.

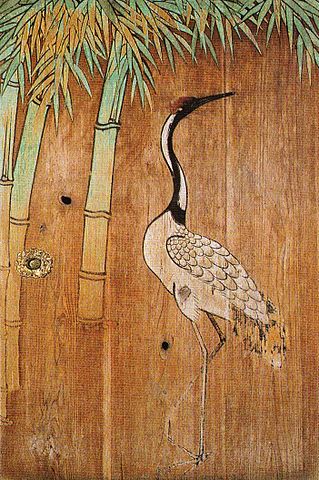

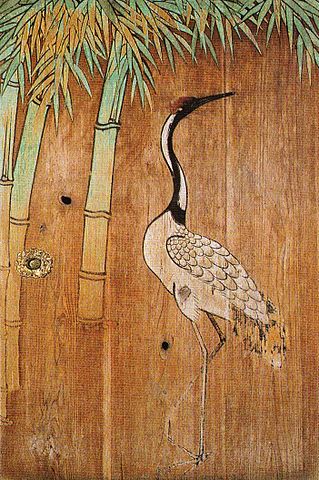

As early as 1769 pedigree was decomposed into pied de grue “the foot of the crane.” The reference would have been to the pedigrees drawn in the form resembling a crane standing on one leg, a position resembling the heraldic genealogical tree. Mahn knew this etymology, rejected it, and chose Stephen Skinner’s par degrés (Skinner’s dictionary appeared in 1671). Apparently, Augustin Thierry, the French historian, shared the crane’s foot idea, but I am not sure where he said so (allegedly, in his book on the Norman Conquest) and would again appreciate a tip.

Does the current etymology of pedigree have a leg to stand on?

Skeat, though at one time he was ready to accept Wedgwood’s “table of relationships” (

Hensleigh Wedgwood occupied center stage in English etymological studies until Skeat displaced him). However, soon he felt convinced that the variants with -

ew ~ -

ewe were particularly revealing and tried to understand what the crane (French

grue) had to do with genealogy or descent. He discovered the Old French proverb

à pied de grue, glossed in a dictionary as “in suspence, on doubtful tearms” (I am retaining the contemporary orthography of the gloss). “Thus,” he said, “it is just conceivable that a pedigree was named from its doubtfulness, in derision.” In a survey of the conjectures on the pedigree of the word

pedigree,

J. Horace Round, a historian and genealogist of the medieval period, wrote (1887): “With reference to Professor Skeat’s suggestion, which is gravely advanced in his Dictionary, I cannot but wonder that so eminent an etymologist should have seriously put forward so far-fetched a derivation, and one so strangely out of the spirit of that age in which the word was formed.” The first edition of

The Century Dictionary copied Skeat’s guess. However, Skeat soon gave it up and offered a convoluted but equally unconvincing new etymology, which Round again ridiculed. Unfortunately, Skeat expressed his strong confidence that a neater etymology than the one he proposed cannot be found. He who never thought twice before castigating his opponents preferred to be praised rather than taken to task (a pardonable attitude) and commented drily on a “not very courteous manner by Mr. Round.”

In 1895 Charles Sweet, the brother of the famous Henry Sweet, and Round put forward the same explanation: according to them, the mark used in old pedigrees had the shape of a so-called broad arrow, that is, a vertical short line and two curved ones radiating from a common center, like three toes of a crane’s foot, with an allusion to the branching out of the descendants from the paternal stock. (In 1887 Round still believed in the source being a crane standing on one leg.) This explanation has become dogma. It can be found in all modern reference works, including the second edition of The Century Dictionary, the last edition of Skeat’s dictionary, and the OED. This situation justifies my title about small triumphs of etymology: after centuries of intelligent guessing, the right solution was found and satisfied nearly everybody.

As some contemporary critics pointed out, several flies stick in the otherwise admirable ointment. We have seen that the letter -g- in the middle of the word pedigree alternated with -c- (pronounced as k) and -d- alternated with -t-. The surnames Pettigrew and Pettygrew bear witness to the popularity of the -t- form. Those variants have never been explained. Also, the modern form is pedigree rather than pedigru(e). Obviously, people did not understand the derivation of that noun and changed -gru to something that looked like degree (as we have seen, many researchers also took -gre at face value). The alternation g ~ c is equally puzzling. At one time, Skeat traced the word to cru- “increase” and believed that the sound of k had acquired voice between two vowels. But the story appears to have begun with gru-, and there was no reason for -g- to turn into k! If the 1410 Latin example (the earliest one known) has value, the form Pedicru in it testifies to the antiquity of c (k) in pedigree.

I suspect that the original editors of the OED followed the Round-Sweet etymology without much enthusiasm, for they quoted Skeat (the latest version) and Sweet and seemed to have accepted their explanation for want of a better one. The OED online suggests that pedi- perhaps shows assimilation to petty or petit, but why should pedigree arouse associations with something small? (Are we ready to return to the idea of “small steps,” so that -gru- will emerge as an alteration of -gre-?) And if -gru- changed to -gre- and pedi- changed to peti- under the influence of degree and petty respectively, why did pedigree become so opaque so early? Speakers begin to indulge in folk etymological games when the word’s form becomes impenetrable through wear and tear. When was our word or the metaphorical phrase transparent and how long did it remain such? As far as we can judge, its provenance was Anglo-French, for on the continent its analogs did not exist (only much later did Engl. pedigree make its way into Modern French). It also remains unclear why the Anglo-Normans needed a neologism for a well-developed concept. Round suggested that pedigree began its life as slang. Perhaps it did. The upper classes do have their jargon. Is then the word centuries older than its first attestation (dignified compositions tend to avoid slang), so that by the fifteenth century no one could recognize the elements of the compound?

Such are etymological triumphs. In Rome, when a triumph was celebrated, a clown ran along the chariot and denigrated the conqueror. In the study of word origins our chariot is still rolling through the streets of Ancient Rome to the shrieks of a comedian.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Jesse window in Dorchester abbey. Photo by Bill Tyne. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Bill Tyne Flickr. (2) Zuiganji Sugito. Painting on sliding door (sugito) c. 1620. Hasegawa Toin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Little triumphs of etymology: “pedigree” appeared first on OUPblog.

For ten years I was a proper PAYE employee, selling the likes of frozen food, tennis shoes and booze. For the next ten years I was freelance, selling money in the form of mortgages and investments. At some point I was invited to give a guest lecture at the Chartered Institute of Marketing. Given that I was seven months pregnant, I probably should have declined. Instead I pulled on a pair of black trousers with an oh-so-attractive stretchy panel fetchingly topped by an elastic waistband (for that little known waist that is in fact directly beneath your breasts), buttoned the matching black maternity waistcoat (what joker thought of that) and drove to Cookham.

For ten years I was a proper PAYE employee, selling the likes of frozen food, tennis shoes and booze. For the next ten years I was freelance, selling money in the form of mortgages and investments. At some point I was invited to give a guest lecture at the Chartered Institute of Marketing. Given that I was seven months pregnant, I probably should have declined. Instead I pulled on a pair of black trousers with an oh-so-attractive stretchy panel fetchingly topped by an elastic waistband (for that little known waist that is in fact directly beneath your breasts), buttoned the matching black maternity waistcoat (what joker thought of that) and drove to Cookham. My subject was segmentation. Bread and butter stuff. I had all sorts of examples from the world known as FMCG (fast moving consumer goods), from retail and from financial services. All I had to do was teach the theory, show examples – the brilliant dog food slides were ready and waiting – and then relate it to the fields they were working in. I could do that with or without oxygen.

My subject was segmentation. Bread and butter stuff. I had all sorts of examples from the world known as FMCG (fast moving consumer goods), from retail and from financial services. All I had to do was teach the theory, show examples – the brilliant dog food slides were ready and waiting – and then relate it to the fields they were working in. I could do that with or without oxygen. In what was overall a pretty grey-with-clouds lecture, I enjoyed the little spell of sunshine. Motivation wasn’t something mosquito experts thought a lot about. They thought about geography and insects and shelter and disease and mosquito net fixing kits. They didn’t think about what might be on the mind of the traveller, setting off alone to try and find traces of the Hairy-nosed Otter in Borneo, or maybe the traveller’s nervous father, buying the very best treated mosquito net for his passionate but impractical son.

In what was overall a pretty grey-with-clouds lecture, I enjoyed the little spell of sunshine. Motivation wasn’t something mosquito experts thought a lot about. They thought about geography and insects and shelter and disease and mosquito net fixing kits. They didn’t think about what might be on the mind of the traveller, setting off alone to try and find traces of the Hairy-nosed Otter in Borneo, or maybe the traveller’s nervous father, buying the very best treated mosquito net for his passionate but impractical son.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Anatoly Liberman is the author of