new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: religion in america, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: religion in america in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: AlyssaB,

on 10/2/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

America,

nature study,

religion in america,

*Featured,

Baptized with the Soil,

Christian Agrarians and the Crusade for Rural America,

Kevin M. Lowe,

Liberty Hyde Bailey,

religion in american history,

Books,

Religion,

Add a tag

In the United States today there is a great push to get children outside. Children stay indoors more and have less contact with nature and less knowledge of animals and plants than ever before. When children do go outside, our litigious society gives them less freedom to explore. Educators and critics such as Richard Louv and David Sobel express a concern that without a real connection to the natural world, something vital will be lost in the next generation -- and that the challenges of climate change may be unsolvable.

The post No child left inside on the Holy Earth: Liberty Hyde Bailey and the spirituality of nature study appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Carolyn Napolitano,

on 10/1/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

evangelicalism,

Arts & Humanities,

Inventing American Religion,

Robert Wuthnow,

sexually active,

Books,

Religion,

poll,

survey,

sexuality,

America,

evangelicals,

Infographics,

religion in america,

*Featured,

American Religion,

Add a tag

Polls about religion have become regular features in modern media. They cast arguments about God and the Bible and about spirituality and participation in congregations very differently from the ones of preachers and prophets earlier in our nation's history. They invite readers and viewers to assume that because a poll was done, it was done accurately.

The post Can we trust religious polls? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlyssaB,

on 8/25/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Religion,

american history,

America,

cartography,

Humanities,

*Featured,

maps,

hell,

slideshow,

religion in america,

Damned Nation,

Hell in America from the Revolution to Reconstruction,

Kathryn Gin Lum,

purgatory,

Add a tag

Antebellum Americans were enamored of maps. In addition to mapping the United States’ land hunger, they also plotted weather patterns, epidemics, the spread of slavery, and events from the nation’s past.

And the afterlife.

Imaginative maps to heaven and hell form a peculiar subset of antebellum cartography, as Americans surveyed not only the things they could see but also the things unseen. Inspired by the biblical injunction to “Enter ye in at the strait gate: for wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction… and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it” (Matthew 7:13-14 KJV), the maps provided striking graphics connecting beliefs and behavior in this life to the next.

-

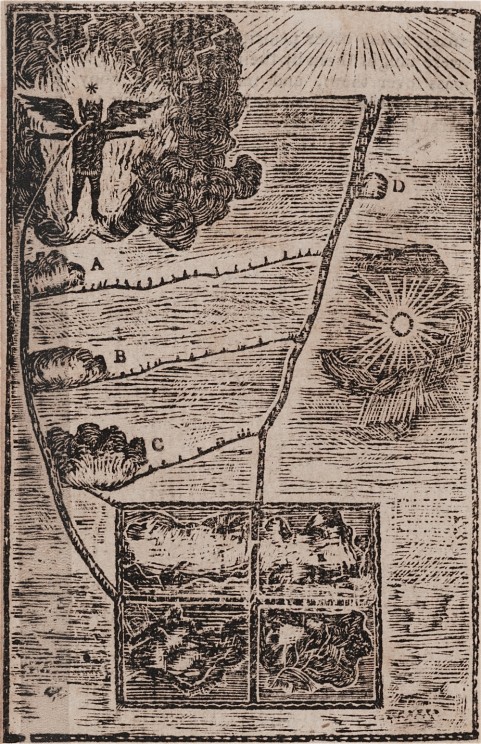

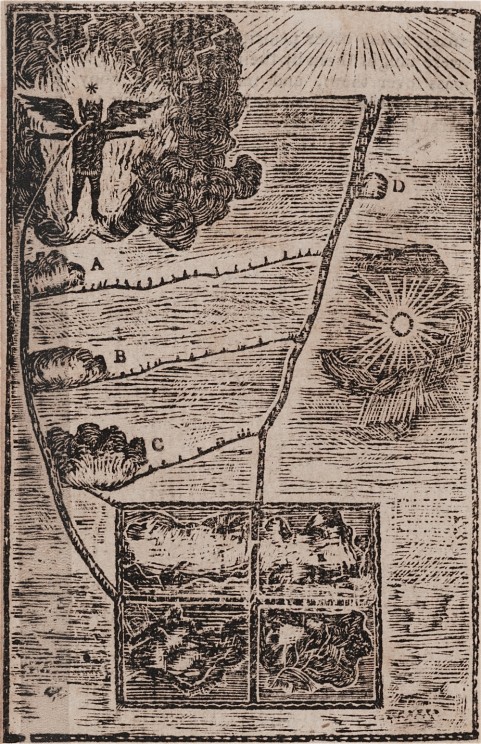

“Mah-tan’-tooh, or the Devil, standing in a flame of fire, with open arms to receive the wicked.”

As early as the 17th century, Catholic missionaries were using didactic visuals of heaven and hell to surmount a language barrier with indigenous North Americans. Such illustrations probably influenced the cosmological map of Neolin, the Delaware Prophet. Born around 1762 near Lake Erie, Neolin experienced a series of otherworldly visions that he turned into a map for his followers. The image here, copied by a white observer, was published some years later in a volume of captivity narratives. The rectangle at the bottom of the map represented the earth and its inhabitants. Those who avoided temptation would proceed directly to future bliss on the path labeled “D,” while those who followed paths A, B, and C would undergo various purgation processes before receiving their reward. The wicked, on the bottom left of the rectangle, would go straight to a fiery hell guarded by the Devil. Neolin warned his followers that the vices Europeans brought, like alcohol consumption, had made the path to future bliss more perilous.

Credit: In Archibald Loudon, A selection, of some of the most interesting narratives, of outrages, committed by the Indians, in their wars, with the white people… (Carlisle [Pa.]: From the press of A. Loudon (Whitehall), 1808-1811). Monroe Wakeman and Holman Loan Collection of the Pequot Library Association, on deposit in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Pequot L92. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

-

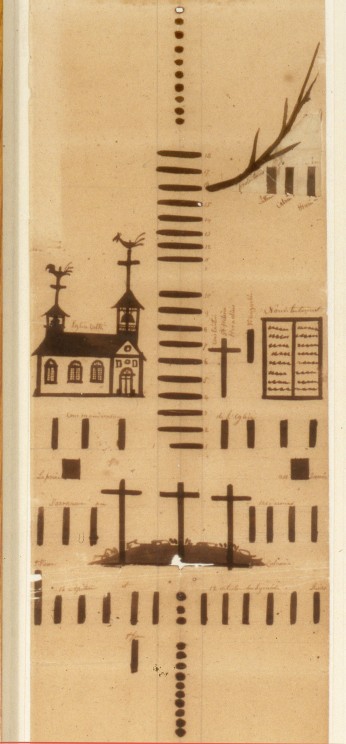

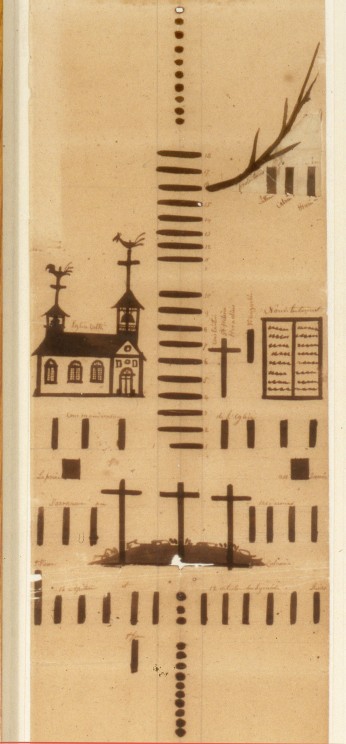

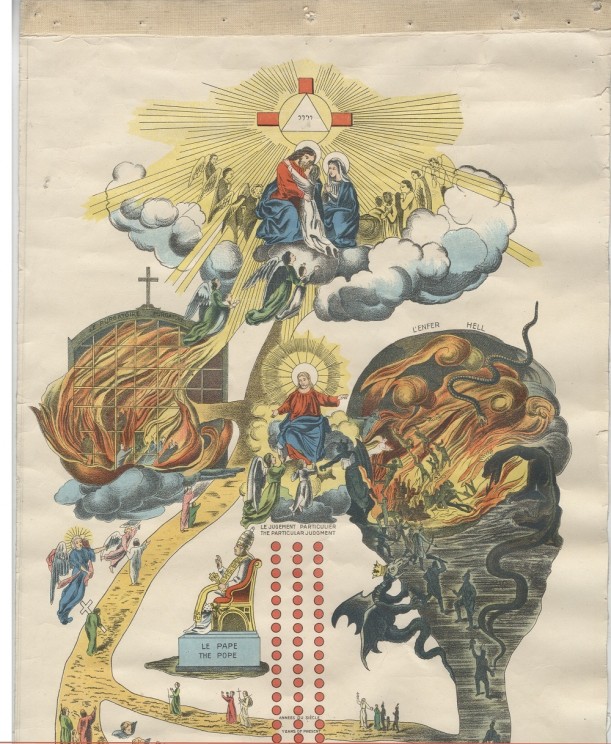

Catholic Ladder

Like earlier didactic devices, this Catholic Ladder (ca. 1840) was created by a French Catholic missionary for the purpose of evangelization. First carved into a large wooden stick, and then painted on a paper scroll measuring nearly five feet long, the Catholic Ladder served as a visual aid for Father Francis Norbert Blanchet and his associates to explain sacred history to the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest. Blanchet drew bars to represent the passage of centuries and dots to represent years in the life of Christ, and added simple pictures to illustrate sacred events. There is no sign of heaven or hell in this ladder, which simply ends with Blanchet’s mission in the present day. But this wasn’t just a neutral timeline: for Blanchet, there clearly is a wrong path to follow. In the detail shown here, Blanchet depicted the Protestant Reformation as a spindly branch off the main course of sacred history, with the three bars below it representing Luther, Calvin, and Henry VIII.

Credit: By Fr. Francis Norbert Blanchet, ca. 1840. 6 1/2 x 58 in. Section from middle of ladder, showing the Crucifixion to the Protestant Reformation. Courtesy of The Oregon Historical Society, Image Number OrHi 89315.

-

Protestant Ladder

Protestant missionaries Henry and Eliza Spalding, who also traveled to the Pacific Northwest, responded to the Catholic depiction of Reformation heroes with a ladder of their own. Six feet long and two feet wide, the ladder made explicit the biblical teaching about the wide and narrow paths. Painted by Eliza with ink and colored dyes made from berries and natural pigments, the ladder, like Blanchet’s, also illustrated sacred history beginning with Adam and Eve. But it divided this history into the good and the bad, and instead of ending in the present, it ended with the reward of the righteous and the punishment of the wicked. On the right (directionally and morally) path to heaven, the Spaldings included Moses, Paul, and Martin Luther. On the left and wider path to hell, they featured the Tower of Babel, the beheading of John the Baptist, and several scenes with the Pope, culminating with his headfirst fall into a fiery hell where a horned devil awaits.

Credit: By Henry H. and Eliza Spalding, ca. 1845. Section from top of ladder. Courtesy of The Oregon Historical Society, Image Number OrHi 87847.

-

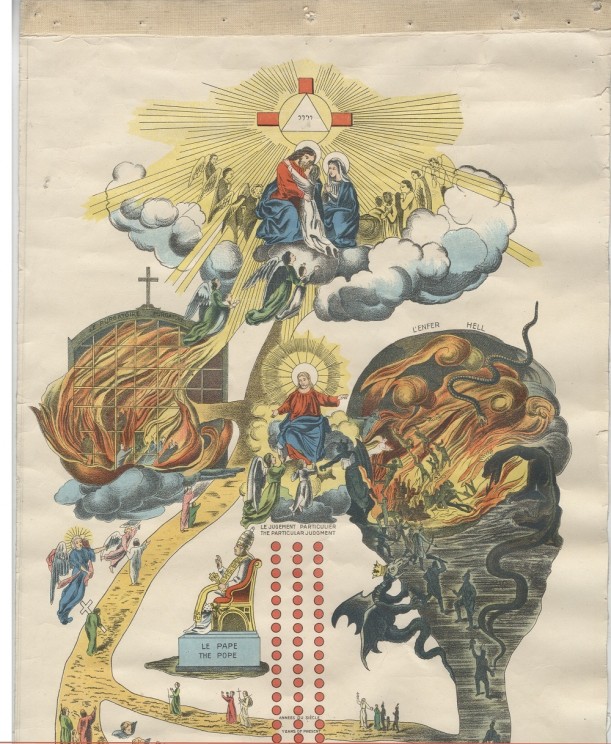

Tableau-catéchisme/Pictorial catechism

If the colorful and dramatic Protestant Ladder was more visually exciting than Blanchet’s monochrome series of bars and dots, Albert Lacombe’s mass-produced version from the 1870s was even more so. Lithography techniques had improved by this time, making it possible to make tens of thousands of copies of the striking six foot by one foot scroll. Like the Spaldings, Lacombe embellished the idea of the two roads to heaven and hell, but his was a Catholic version that included a fiery Purgatory on the path to heaven. And, where the Spaldings had the Pope falling into the flames of hell, Lacombe featured the richly-clad Pope on a gilded throne, pointing the way to heaven. No surprise that the Pope himself endorsed the ladder, which saw use among Catholic missionaries worldwide.

Credit: By Reverend Albert Lacombe, O.M.I., 1874. Purgatory to the left, hell to the right, heaven above. Original at Missionary Oblates, Grandin Province Archives at the Provincial Archives of Alberta. Printed on four pasted panels glued together and backed with linen, attached to a stick, and rolled like a scroll. Electronic image courtesy of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University Libraries.

-

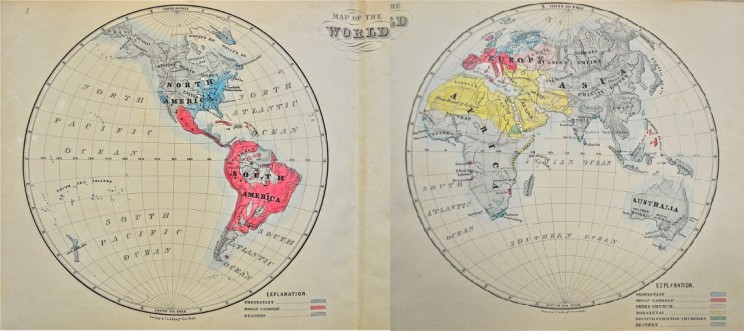

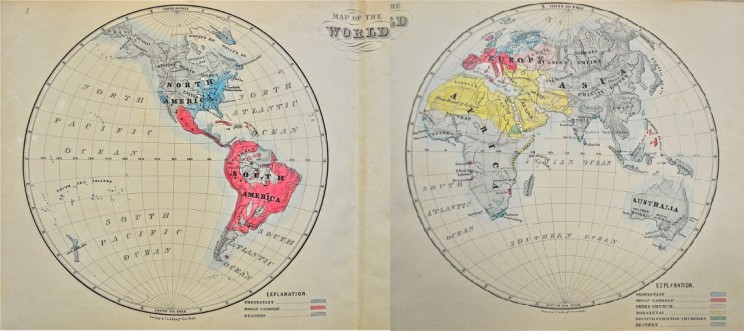

Frontispiece in John Cameron Lowrie, A Manual of Missions, or, Sketches of the Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church

On the face of it, this is not a guide to heaven or hell. It is a detailed map of the world, so rooted in the here-and-now that it is meticulously plotted along latitude and longitude. It seems fairly neutral at first glance. But the color-coded key tells a more partisan story. Each region of the world is colored according to religion. For John Cameron Lowrie, the corresponding secretary of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions, only the blue of Protestantism was salvific. The didactic moral of the map? Live in or move to a blue zone, and help to color the rest of the world blue by converting its inhabitants to Protestantism and hence saving them from eternal damnation.

Credit: Photograph by Nicholas Lum.

-

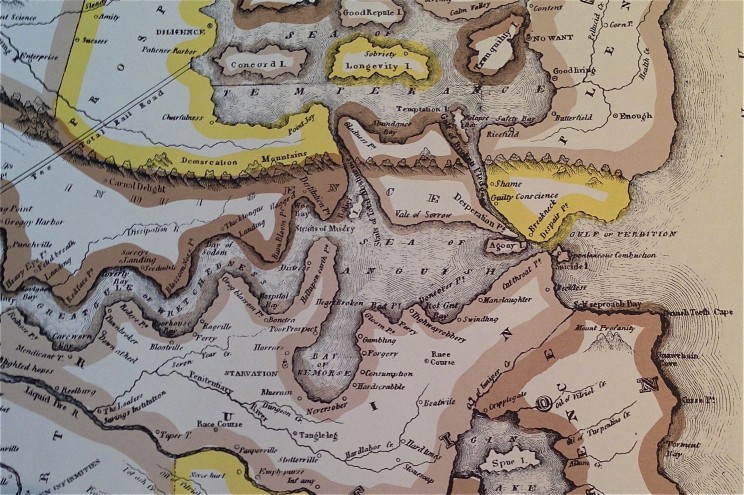

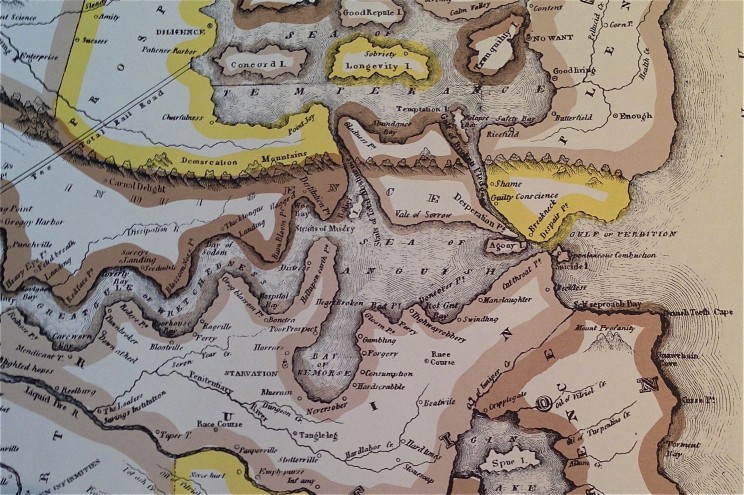

Temperance Map

The nineteenth-century temperance movement in the US sought to curtail alcohol consumption in a nation where it was widespread. Its reach extended to Hawaii, where sailors boozed in port towns and alcohol made its way to the indigenous population. At Lahainaluna Seminary on the island of Maui, Hawaiian students produced this Temperance Map, which depicted the ruinous consequences of alcohol and the rewards of temperance. They also printed a simplified version of the map in Hawaiian. Unlike the ladders, which showed fairly straightforward roads to heaven or hell, the temperance maps offered a tangle of choices that could lead in multiple directions. Viewers were cautioned to exercise constant vigilance. Even if one was happily floating on the Sea of Temperance, making stops at the isles of Longevity and Tranquility, the map showed how easy it was to get swept into Relapse Bay and the Gulf of Broken Pledges. And from there, the Gulf of Perdition was just one wrong turn away.

Credit: by C. Wiltberger Jr. (Published by L. Andrews, Lahainaluna, Maui, Republished in 1972 by the Hale Pa’i Printing Museum of the Lahaina Restoration Foundation, Lahainaluna, Lahaina, Hawaii, 96761). Photograph by author from personal copy. Detail shows the “Sea of Anguish” in the center and the “Sea of Temperance” above it, connected by the “Strait of Total Abstinence” and the “Gulf of Broken Pledges,” which also leads to the “Gulf of Perdition” to the right.

The post The road to hell is mapped with good intentions appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlyssaB,

on 6/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

religion in america,

What Is an American Muslim?,

abstention,

Religion,

Ramadan,

Islam,

Humanities,

Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im,

Embracing Faith and Citizenship,

fasting,

Add a tag

By Abdullahi An-Na‘im

Immigrant Muslims continue to rely on the Ramadan culture of their regional origins (whether African, Middle East, South Asian, etc.). What is the culture of Ramadan for American Muslims? Is that culture already present, or do American Muslims have to invent it? Whether pre-existing or to be invented, where does that culture come from? Does having or cultivating a culture of Ramadan diminish or enhance American cultural citizenship? Can the same question be raised for a culture of Thanksgiving or Christmas?

I am not suggesting by raising such questions that there is a single monolithic culture of Ramadan for all American Muslims, but mean to argue that American Muslims should reflect on how to socialize their children a common core of values and practices around Ramadan for this holy month to be as enriching for the children as it has been their parents. Part of the inquiry should also be how to avoid aspects of the culture of Ramadan for the parents which will be negative or counterproductive for their children. To begin this conversation, let me begin by presenting what I believe my own culture of Ramadan has been growing up along the Nile in Northern Sudan.

Ramadan Prayer. Photo by Thamer Al-Hassan. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Fasting for a Muslim is total abstention from taking any food, drink, or having sex from dawn to sunset. Religiously valid fasting requires a completely voluntary and deliberate decision and intent (niya) to fast that is formed prior to the dawn of the day one is fasting. This intent to fast is entirely a matter of internal consciousness and free choice, but has two highly significant implications. On the one hand, the entirely voluntary nature of fasting and all Islamic religious practices is that the state cannot interfere with the choices Muslims make. That means that the state must be neutral regarding religious doctrine (i.e. secular) and cannot claim to be Islamic, or pretend that it can enforce Sharia because that would encroach on the ability of Muslims to act on their individual conviction and choice. On the other hand, abstention from food, drink, and sex with the required free and autonomous intent to fast must also be accompanied by maintaining appropriate decorum by avoiding harming other people, hurting their feelings, or using abusive language. Moreover, the more affirmative good a person does while fasting, as opposed to simply refraining from causing harm, the more religious benefit she or he achieves. The Prophet repeatedly cautioned against the futility of fasting, as abstention without realizing any religious benefit because of failure to observe the etiquettes (adab) of fasting.

The practice of fasting draws on much more than a religious mandate. There is a whole culture of Ramadan that sustains the practice, including the communal expectations and rewards of social conformity beyond the commands of religious piety. A culture of Ramadan defines and affirms the religious practice, including all the sounds and smells of the season, the shifting of the rhythm of social life to the carnival of evenings of sweet food and special drinks. Fasting the days of Ramadan entitles me to participate in the carnival of the evenings and sanctions my belonging to the community of believers.

As children we used to be excited with special activities, different foods, and delicious unusual drinks in the evenings, with slight apprehension for our own disrupted meals during the day, when grownups were too dehydrated and hungry to cook for us while they fasted. Although children are not allowed to fast until they reach puberty, so we used to dare each other to fast a few days, but often break the fast when we get hungry. Our social code of honor tolerated breaking the fast as children, but imposed harsh stigma and shame upon those who pretend to fast but cheat by eating or drinking in secret. I also remember my parents telling me not to fast because I was a child, but once I began fasting a day, I must keep fasting until sunset because breaking the fast may become a habit. Those were some of the values of the culture of Ramadan I grew up with.

Other values of the culture of Ramadan draws on what we observed in the behavior of our elders. As I recall, it was unthinkable for adults to speak of their ambivalence about fasting Ramadan. Yes, it was also clear to us that our parents were struggling to be productive and take care of us despite the hardship of fasting. All these mixed feelings were so deeply engrained into our consciousness as children that we grew up with a complex combination of love and apprehension of Ramadan. We were also socialized into the values of self-discipline and management of ambiguity and the ambivalence of religious piety and social conformity. When we became old enough to fast regularly, failing to fast was so alien and abhorrent to us, utterly out of the question. This deeply engrained aversion of failure to observe Ramadan may have been more social than religious, but it was social because fasting is one of the essential requirements of Islam.

Another social ritual of Ramadan is arguing about the sighting of the new moon, which signifies both the beginning and ending of the month of fasting. At one level, the debate has always about whether Ramadan should begin, or should end, because a new moon is confirmed. Who has the authority to confirm, however, is a highly charged political question within each country, and contested regional politics across the Muslim world. At another level, the underlying issue is whether to follow the literal language of the Quran and Hadith (physical sighting) or rely on astronomical calculations and trust human judgment and scientific advances. If either side concede the position of the other, that will have far reaching consequences in every aspect of religious doctrine and practice, indeed the totally of Sharia can be transformed as a result of the prevalence of one view or the other among Muslims globally. The debate over the sighting of the new moon also has some immediate practical implications for the ability of American Muslims to negotiate for religious accommodation in their work schedule by giving their employers (or school authorities) advance notice of religious holidays.

Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im is the Charles Howard Candler Professor of Law at Emory Law, associated professor in the Emory College of Arts and Sciences, senior fellow of the Center for the Study of Law and Religion, and senior faculty fellow of the Emory University Center for Ethics. An internationally recognized scholar of Islam and human rights, An-Na’im is the author of six books, including What Is an American Muslim?: Embracing Faith and Citizenship. He is the former Executive Director of Human Rights Watch/Africa.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Is there an American culture of Ramadan? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlyssaB,

on 4/12/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Religion,

mexico,

America,

Humanities,

religion in america,

*Featured,

Mexican-American War,

patricios,

pinheiro,

Add a tag

By John C. Pinheiro

Few Americans today would have difficulty imagining a United States where the citizens disagree over the wisdom of immigration, question the degree to which Mexicans can be fully American, and dispute about the value of religious pluralism. But what if the America in question was not that of 2014 but rather the 1830s and 1840s? Along with being a high point of anti-Catholic nativism, these two decades witnessed the Texas Revolution, the US annexation of Texas, violence in US cities against Catholic immigrants, and the Mexican-American War. As Americans struggled to negotiate their identity as a people in terms of race, religion, and political culture, the war with Mexico clarified and for one century afterward cemented American identity as a Protestant, Anglo-Saxon republic.

Manifest Destiny held that American Anglo-Saxons, by reason of their cultural and racial superiority, were destined to overtake the western hemisphere. This Anglo-Saxonism was not so much based on attributes like skin color, as it was on unique attitudinal traits that predisposed Anglo-Saxons to be the most effective guardians of liberty. From this innate love of freedom had sprung Protestantism and republicanism—the religion and government for free men.

While the majority of Americans condemned a series of mob attacks against Catholic convents, churches, and schools in Boston and in Philadelphia, they nevertheless agreed with nativists that Catholicism was incompatible with representative—or what they called, “republican”—government. Politically unstable Mexico, they said, was proof of this.

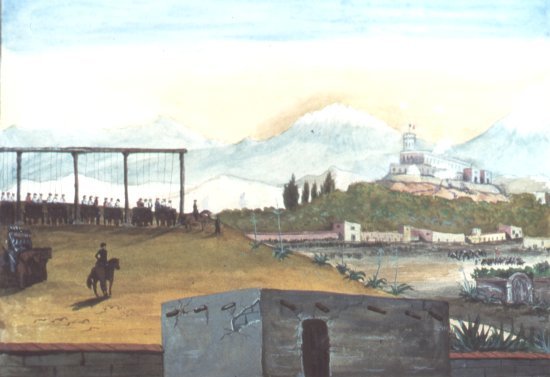

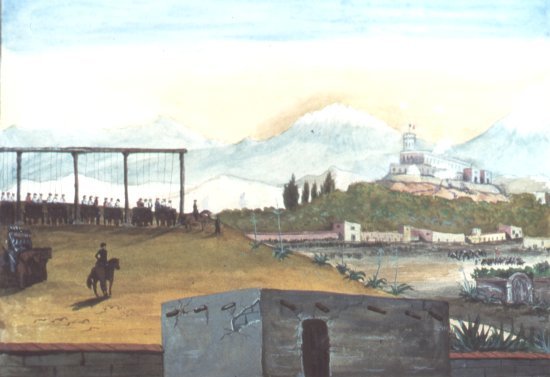

When the United States and Mexico went to war in 1846, doubts quickly surfaced about the patriotic fortitude of foreign-born, Irish-Americans in a war against a Catholic nation. Irish immigrant soldier John Riley fled the US army on 12 April 1846, about two weeks before the first battle of the war. American authorities suspected that in September 1846 he was the leader of a group of mostly Irish and Catholic deserters at the Battle of Monterey. These rumors were true, and in late 1847 the US Army captured the San Patricios, or Saint Patrick Battalion. In the United States, debate ensued over the San Patricios’ motives and goals. At stake was the question of immigrant Catholic loyalty to the United States.

So, what were the factors in the San Patricio desertion? Abuse by nativist American officers was one of them. For a given crime, officers would sometimes merely demote native-born soldiers while imprisoning, whipping, or dishonorably discharging foreign-born men. Atrocities, church looting, and violence against priests by some American troops aggravated the fear that the Protestant United States was attacking not just Mexico but the Catholic faith.

The causes of this desertion, however, were not a one-sided affair. Mexican propaganda enticed Americans to leave their ranks. One broadside was addressed to “Catholic Irishmen” by General Antonio López de Santa Anna but the writer probably was Riley. It beckoned Americans to “Come over to us; you will be received under the laws of that truly Christian hospitality and good faith which Irish guests are entitled to expect and obtain from a Catholic nation.” It then asked, “Is religion no longer the strongest of all human bonds? Can you fight by the side of those who put fire to your temples in Boston and Philadelphia”?

It is most accurate, then, to say that while religion was involved in the defection, most of the San Patricios deserted because of intense abuse by officers, not for love of Mexico or the Catholic Church. This includes Riley. In all, 27 San Patricios were hanged.

Hanging of the San Patricios following the Battle of Chapultepec. Painted in the 1840s by Sam Chamberlain. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The capture and punishment of the San Patricios may have been dramatic, but the questioning of Catholic loyalty was just one small part of religion’s interplay with the war. Religious rhetoric constituted an integral piece of nearly every major argument for or against the war. This civil religious discourse was so universally understood that recruiters, politicians, diplomats, journalists, soldiers, evangelical activists, abolitionists, and pacifists used it. It helped shape everything from debates over annexation to the treatment of enemy soldiers and civilians. Religion also was the primary tool used by Americans to interpret Mexico’s fascinating but alien culture.

More than any other event during the nineteenth century, the Mexican-American War clarified the anti-Catholic assumptions inherent to American identity. At the same time, from the crucible of war emerged an American civil religion that can only be described as a triumphalist Protestant and white, anti-Catholic republicanism. That civil religion lasted well into the twentieth century. The degree to which it is still alive today in current debates over Latino immigration is debatable, but one can hardly miss the resemblance and connection between the issues of the 1840s and those of 2014.

John C. Pinheiro is Associate Professor of History at Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He has written two books on the Mexican-American War. His newest book is Missionaries of Republicanism: A Religious History of the Mexican-American War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Mexican-American War and the making of American identity appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlyssaB,

on 3/15/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

germantown,

avenue,

congregations,

faith on the avenue,

international women's month,

katie day,

religion on a city street,

women in leadership,

hagar,

sandberg,

hurleyite,

sheryl,

Books,

women,

Religion,

women's history month,

pastor,

Philadelphia,

leadership,

pastors,

Humanities,

religion in america,

Add a tag

By Katie Day

I am one of the last professional women I know to read Lean In by Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg (Knopf, 2013). If you are also among the laggards, it is an inspiring call to women to lean into leadership. Too often, Sandberg shows through research and life story, women are not considered “leadership material,” and not just by men. We also send that message to ourselves, and attribute any success to external factors such as luck and the support of others. We just don’t think we have the right stuff to be leaders.

Too bad Sheryl Sandberg has not been to Germantown Avenue in Philadelphia. After studying the communities of faith along that one street—around 88 congregations, the number fluctuating year to year—I found one thing that stumped me. There are a whole lot more women in leadership in these houses of worship than in any national sample of clergy. The most generous research findings reflect 10-20% of congregations to be headed by women in the United States today. In my sample, 44% of communities of faith have female leadership. This phenomenon is true across the religious spectrum. “Prestigious pulpits” in the historic Mainline Protestant churches are disproportionately occupied by women. But so were the pulpits in small independent African-American churches. Two of the three mega-churches had women as co-pastors. In the third, the associate pastor is a woman and considered the heir-apparent for the senior position. Two of the three peace churches had women leaders. There are no longer Catholic churches on the Avenue (which don’t have women priests), and the two mosques I researched were led exclusively by men. But the small Black spiritualist Hurleyite congregation (Universal Hagar) has a woman as pastor.

Universal Hagar Church, a Hurleyite congregation, is located across the street from Fair Hill Burial Ground. Photo by Edd Conboy. Used with permission.

How can we account for this? It might have something to do with Philadelphia’s cultural history of inclusivity, providing a context in which women broke through the stained glass ceiling in the AMEZ and Episcopal traditions. Perhaps it is more closely related with the Great Migration North, in which women sought out church anchors in neighborhoods in which to settle. Frankly, I am hoping a researcher will figure this out…and bottle it!

More impressive to me than the numbers are the amazing women I interviewed. Women like Pastor Jackie Morrow, who started a church and a school in a row house, and ministers to everyone in her corner of Northwest Philly, from the young men who play basketball in her parking lot to the mentally challenged woman who regularly stops by for prayer, food, and a hug. Or Rev. Melanie DeBouse, who pastors in the poorest neighborhood in the city and is teaching young children to “kiss your brain” and older men how to read. Or Rev. Cindy Jarvis, senior pastor at the Presbyterian Church of Chestnut Hill, where she oversees a budget of over a million dollars and has underwritten efforts to prevent gun violence, provide health care for the poor, and a vibrant social and educational program for seniors. These women, and others on the Avenue, are leaning in to take leadership roles not in corporations but in the trenches of gnarly urban problems.

Make no mistake: I like Sandberg’s book. But the clergy women of Germantown Avenue are leaning into stronger headwinds with impressive competence and confidence. They inspired me more.

Katie Day is the Charles A. Schieren Professor of Church and Society at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia. She is the author of Faith on the Avenue: Religion on a City Street and three other books and numerous articles that look at how religion impacts a variety of social realities.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Leaning in appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Lauren,

on 10/5/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

A-Featured,

Western Religion,

A-Editor's Picks,

christianity,

gods,

america's four gods,

baylor,

christopher bader,

images of god,

paul froese,

religion in america,

believers,

thearda,

benevolent,

froese,

bader,

authoritative,

god,

Add a tag

According to surveys, 95% of Americans believe in God. Although it can sometimes feel that the greatest rifts are between believers and non-believers, disputes are more often caused between groups of believers who simply don’t agree about what God is like. In America’s Four Gods: What We Say About God – and What That Says About Us, Paul Froese and Christopher Bader use original survey data, in-depth interviews, and “The God Test” to reveal the four types of god most American’s believe in. Indeed, this is the most comprehensive and illuminating survey of Americans’ religious beliefs ever conducted.

In The God Test, the four gods presented are the Authoritative God, the Benevolent God, the Critical God, and the Distant God.

What distinguishes believers in an Authoritative God is their strong conviction that God judges human behavior and sometimes acts on that judgment. Indeed, they feel that God can become very angry and is capable of meting out punishment to those who are unfaithful or ungodly. Americans with this perspective often view human suffering as the result of Divine Justice. Approximately 31% of Americans believe in an Authoritative God.

Like believers in the Authoritative God, believers in a Benevolent God see His handiwork everywhere. But they are less likely to think that God judges and punishes human behavior. Instead, the Benevolent God is mainly a force of positive influence in the world and is less willing to condemn individuals. Believers in this God feel that whether sinners or saints, we are all are free to call on the Benevolent God to answer our prayers in times of need. Approximately 24% of Americans believe in a Benevolent God.

Believers in a Critical God imagine a God that is judgmental of humans, but rarely acts on Earth, perhaps reserving final judgment for the afterlife. The Critical God appears to hold a special place in the hearts of those who are the most in need of help yet are denied assistance. Approximately 16% of Americans believe in a Critical God.

Believers in a Distant God view God as a cosmic force that set the laws of nature in motion and, as such, the Distant God does not really “do” things in the world or hold clear opinions about our activities or world events. In fact, believers in a Distant God may not conceive of God as an entity with human characteristics and are loathe to refer to God as a “he.” When describing God, they are likely to reference objects in the natural world, like a beautiful day, a mountaintop, or a rainbow rather than a human-like figure. These believers feel that images of God in human terms are simply inadequate and represent naïve or ignorant attempts to know the unknowable. Approximately 24% of Americans believe in a Distant God.