new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Cheney publications, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 76

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Cheney publications in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

At the

Los Angeles Review of Books, I have

a new essay about Samuel R. Delany's 2007 novel Dark Reflections, which is about to be released in

a new and slightly revised edition by Dover Books. Here's a taste:

In many ways, Dark Reflections is a narrative companion to Delany’s 2006 collection of essays, letters, and interviews, About Writing. In the introduction to that book, Delany says that its varied texts share common ideas, primary among them ideas about the art of writing fiction, the structure of the writer’s socio-aesthetic world both in the present and past, and “the way literary reputations grow — and how, today, they don’t grow.” The book is mainly, though not exclusively, aimed at aspiring writers. It provides some advice on craft, but it circles back most insistently to questions of value, and especially to questions of the difference between good writing and talented writing — and what it means, practically and materially, for a writer to shape a life around an aspiration toward the highest levels of achievement. While About Writing poses and explores these questions, Dark Reflections dramatizes them.

Read more at LARB

I have a brief new essay up at The Story Prize Blog,

"Why I Am Not a Poet". Here's a taste:

I care about words, structures, rhythms, resonances, patterns, allusions, borrowings, sentences, images, emotions, voices, dreams, realities, fears, anxieties, failures, yearnings, and much more, but I don't really care about telling stories. The story is a kind of vehicle, or maybe an excuse, or maybe an alibi. The conventions of the story can be followed and forsaken in ways that get me to the other things, the things I care about.

All of those things I care about are things common to poetry — some more common to poetry than to prose, I'd bet — and that is why I read poetry, but even though I read poetry, I write prose because I just don't know how to do those things unless I'm writing prose.

(I think I would rather be a poet, but I am not.)

Literary Hub has published one of the most personal essays I've ever written, an essay about growing up as a reader and person during the AIDS crisis.The original title, which doesn't make a good headline and so wasn't used, is "A Long Gay Book, A Life". (I'm always happy for a Gertrude Stein allusion. And quotation, as you'll see in the piece.)

The piece is fragmentary, like memory. It roams across the page, probably an effect of my recently revisiting some of

Carole Maso's writings. (Also, reading Keguro Macharia's elegant

essays and

blog posts.)

Here's an excerpt:

When I was in the eighth grade I wrote a story about a vampire. He was young, roughly my age, entering puberty, entering vampirism. He ached to touch, to kiss, to drink in the loveliness of what he hungered for, but to do so was to admit his monstrosity and to kill what he loved. He feared himself and hated himself.

I don’t remember anything else about that story except how terrified I was to show it to anyone, lest they notice what I was saying about desire between the lines.

But I did show it to my English teacher. She had been sensitive and supportive of the stories I’d written, no matter how weird and violent. We talked about the story for a while. Now, more than 25 years later, all I remember is that she spoke—casually and not in any way judgmentally, without lingering—about the vampire’s desires being a powerful element of the story because they could also be read as sexual desires.

“No,” I replied quickly, lip trembling, “he’s just a vampire. Vampires have to drink blood or they die.”

She smiled and nodded. “Of course, of course,” she said.

Read more at The Literary Hub.

One of my favorite sites on the internet is Largehearted Boy, which brings music and literature together.

A core series at LB are the Book Notes: playlists of songs to accompany books.

Huge thanks to the Largehearted Boy proprietor, David Gutowski, for inviting me to participate and create

a Book Notes entry for Blood: Stories.

The The, David Byrne, Cowboy Junkies, Washington Phillips, Arvo Pärt, and many more...

Read the rest of this post

When Kelly J. Baker put out a call for essays about music albums and emotions, I knew immediately what I would propose: An essay about The The's

Soul Mining and what it meant to me as an adolescent.

Now, that essay, "Perfect Day", is available on Kelly's site, Cold Takes.Here's the opening:

That moment: album — book — car ride.

How long ago now? Twenty-five years? Something like that.

It was (roughly) sometime between 1988 and 1991, which means sometime between when I was (roughly) 12 years old and 16 years old. Most likely 1989 or 1990. Most likely 14 or 15 years old.

Interstate 93 North between Boston, Massachusetts and Plymouth, New Hampshire.

Blue Toyota Tercel wagon, my mother driving.

Mass market paperback of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep by Philip K. Dick (Blade Runner tie-in edition).

Black Sony Walkman cassette player.

Soul Mining by The The.

read more

In the

Weird Fiction Review conversation I had with Eric Schaller, Eric asked me to talk a bit about designing the cover of

Blood: Stories, and in my recent

WROTE Podcast conversation, I mentioned an alternate version of the cover that starred Ronald Reagan (this was, in fact, the cover that my publisher originally thought we should use, until she couldn't get the image we ended up using out of her mind).

I thought it might be fun to share some of the mock-ups I did that we didn't use — the covers that might have been...

Front(click on images to see them larger)

|

| 1a |

|

| 1b |

1a & 1b. These two are variations on an early design I did, the first one that seemed to work well, after numerous attempts which all turned out to be ghastly (in a bad way). 1b for a while was a top contender for the cover.

|

| 2 |

2. I always liked the idea of this cover ... and always hated the actual look of it.

|

| 3 |

3. I made this one fairly early in the process, using the

Robert Cornelius portrait that is supposedly the first photographic portrait of a person ever made. It ended up being my 3rd choice for the final cover. I love the colors and the eeriness of it.

|

| 4 |

4. This never had a chance of being the actual cover, but I love it for the advertisement alone. As far as I can tell, that was a real ad for revolvers.

|

| 5 |

5. The inset picture is one I took in my own front yard. I like this cover quite a bit, but there's too much of a noir feel to it for the book, which isn't very noir.

|

| 6 |

6. Here it is, the Cover That Almost Was. The image is a publicity photo from one of Ronald Reagan's movies.

|

| 7a |

|

| 7b |

|

| 7c |

7a, 7b, 7c. Once I found

the Joseph Maclise image, I immediately thought I'd found the perfect illustration for the book. It took a long time and innumerable tries to figure out the final version, but it was worth the effort.

|

| Actual cover |

Back

Though the book designer Amy Freels ultimately did the back cover herself, I gave it a stab. As you'll see, we went back and forth on whether to use all of the blurbs or just Chris Barzak's and put the other blurbs on an inside page.

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

1-7. These are a bunch of early attempts. None quite works (some

really don't work), and they would have all felt sharply separate from the front cover. We had lots of conversations about #4, though, as the publisher was quite attracted to the simplicity and boldness of it for a while.

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

8-14. I love these, but they're all too complex for the back cover. As images, though, they still appeal to me deeply. I also like that they use

the Alejandro Canedo (or Cañedo) painting from Astounding (September 1947) that plays such an important role in the story "Where's the Rest of Me", though I also know we probably would have had to figure out how to get the rights to use it, and that could be a huge headache and a wild goose chase.

|

| Full, final cover |

The marvelous

Weird Fiction Review website has now posted

a conversation that Eric Schaller and I had about our books, our magazine

The Revelator, the weirdness of New Hampshire, and other topics.

Along with this,

WFR has posted Eric's story

"Voices Carry" (originally in

Shadows & Tall Trees) and my story

"The Lake" (originally in

Lady Churchill's Rosebud Wristlet).

So if you're curious about us or our writings (or just utterly bored),

Weird Fiction Review is a great place to start.

I'm thrilled that my

A Cappella Zoo story "Killing Fairies" has just been reprinted in

Best Gay Stories 2016 edited by Steve Berman for

Lethe Press.

The table of contents for

Best Gay Stories this year is quite strong, and it's an honor to be among this company. It's especially nice to have my story in a book with a story by Richard Bowes, since "Killing Fairies" is my attempt to write Bowesian tale: something that skirts the line between fiction and memoir. In this case, I wanted to preserve a few memories of my first year of college before those memories slip away (they grow dimmer and dimmer), and I thought a fun way to do that would be to give myself the challenge of trying to write like Rick.

It's harder than it looks. The problem for me was that my memories didn't add up to a story. There were a couple of really great characters (two of the strongest personalities I ever met in my life), but no story, just encounters that ultimately led nowhere because I quickly lost contact with those people as I developed a better network of friends. Then I thought: Who did I

hope to meet in college, but never did? And thus I created the strange, perhaps rakish character of Jack. Once he was added to the mix, the story began to cohere.

Here's a brief excerpt:

Killing Fairies

I met Jack at the end of my first year of college, a year that had begun in misery and ended in something else, though even now I'm not sure what to call it. Jack was two years ahead of me, and like me was one of the few people in our program who wanted to be a playwright and not a screenwriter. He was six-foot-four, scarecrow thin, with short sandy blonde hair and green eyes that won all staring contests. We had our first conversation during the height of a frigid winter. This was back in the mid-'90s, when you could still smoke inside buildings in New York City, and the smoking area for the Dramatic Writing Program at NYU was in a stairwell of the seventh floor of 721 Broadway, headquarters of all my shattered dreams. I regret I wasn't a smoker — it would have been easier to make friends, easier to have the casual conversations that led to connections, especially since the stairwell was an egalitarian place where the distinctions between faculty and students disappeared; the only distinction was between those who were fond of nicotine and those who were not.

I ended up in the stairwell with Jack because we were continuing a conversation we'd begun in class. It was a class called, simply, "Cabaret" — we all wrote and then performed two cabaret shows during the semester. Jack and I had somehow started talking about Arthur Miller, a playwright revered at DWP (he'd taught a course or two just before I enrolled). In class, I'd told Jack I thought Death of a Salesman was sentimental drivel, and he said he was thrilled to hear someone say that. Class ended, and we walked through the narrow DWP hallway to the stairwell, where a couple of other students nodded to Jack, though he paid no attention to them. As our evisceration of Miller's entire career wound down, and as I told Jack for the third time that no, I didn't need to bum a cigarette, he said, "So, tell me something about you I don't know."

"I'm left-handed," I said.

"I know that," he said.

"I'm from New Hampshire."

"Everybody here knows that."

"I used to read a lot of science fiction."

"How cute."

"What about you?" I said.

"Me?"

"It's only fair."

"Fine," he said, exhaling smoke. "I kill fairies."

I'm sure my face displayed exactly what he wanted: wide-eyed shock.

"People give them to me," Jack said. "Fairies. Plastic or glass. Dolls. Icons. And every one of them, I smash with a hammer, or I cut off their hair and wings, or I throw them in front of the subway, or I bite their fucking heads off and spit them to the ground."

Perhaps I chuckled nervously. More likely, I stood silent.

"You should come over sometime," he said. "It's fun. We can have a fairy-killing party."

--------------

Lethe is one of the few LGBT presses out there, and much deserves our support. (And they're currently celebrating their 15th anniversary!) The

Best Gay Stories series is consistently interesting and a valuable guide to queer writing today.

Here's the table of contents:

"A New Gay Fairy Tale" by Sandip Roy

"Repossession" by Jonathan Harper

"Gift-Wrapped" by Daniel M. Jaffe

"Wildlife" by Carter Sickels

"Fordham Court" by Richard Bowes

"What Do You Wear to a Nudist Colony?" by Michael Hess

"Marginalia" by Daniel Scott

"Monograph" by Mike Dressel

"Shoot-out" by Lou Dellaguzzo

"Killing Fairies" by Matthew Cheney

"Acres of Perhaps" by Will Ludwigsen

"Surfaces" by Peter Dubé

"Tea At Balmoral" by Paul Brownsey

"The Lesson" by Kelly Link

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 6/14/2016

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

interviews,

Movies,

horror,

Cheney publications,

aesthetics,

Electric Literature,

Michael Haneke,

neoliberalism,

Blood: Stories,

Adrian Van Young,

Texas Chainsaw Massacre,

Add a tag

The good folks at

Electric Literature invited me to converse with Adrian Van Young, perhaps not knowing that Adrian and I had recently discovered we are in many ways lost brothers, and so we could go on and on and on...

We talked about Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Sublime, writing advice, writers we like, Michael Haneke, neoliberalism, The Witch, and all sorts of other things. It was a lot of fun and we could have gone on at twice the length, but eventually we had to return to our lives.

Many thanks to Electric Lit for being so welcoming.

I have been busy and have neglected this blog. I forgot to make a post here about some of the most exciting news of my year: I have a story in the current issue of my favorite literary magazine, Conjunctions. It's titled "Mass" and it is about, among other things, a mass shooting.

Early this morning, at least 50 people were killed and 53 wounded in a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. The New York Times is currently calling this the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history.

I'm not going to write about the gun politics of this. For that, please read the work of Patrick Blanchfield, particularly "So There's Just Been a Mass Shooting", "God and Guns", and "The Gun Control We Deserve". (He's excellent on Twitter, as well, if you want his most recent thoughts.) I have sputtered on about the topic in the past, not always coherently. Patrick is better at it, and better informed, than I. Thinking through the complex, contradictory, vexing, and emotionally charged landscape of gun politics, I'm better (or at least more comfortable) in fiction. Thus, "Mass".

(Titles fascinate me. The title of this issue of Conjunctions is Affinity: The Friendship Issue. Affinity is something more than friendship. Friendship is useful, it feels good, it glues us socially, and sometimes it may be, yes, an issue. But affinity is more: its etymology [via Latin and French, a story told by the OED] is rich with ideas of relationship: relationship via marriage; any relationship other than marriage; a neighborhood; relationship between people based on common ground in their characters and tastes; spiritual connection; structural relationship; adjacency.)

A character in "Mass" has been reading theoretical physics:

“Not especially detailed theoretical physics, but introductory sorts of texts, popularizations, books for people who don’t really ever have a hope of truly understanding physics but nonetheless possess a certain curiosity. And its words are sometimes beautiful — a tachyonic field of imaginary mass — who couldn’t love such a phrase? I find it all strangely comforting, the more far-out ideas of quantum theory and such. It’s like religion, but without all the rigmarole and obeisance to a god. Or perhaps more like poetry, though really not, because it’s something somehow outside language, but nonetheless elegant, and of course constricted by language, since how else can we communicate about it? But it gestures, at least, toward whatever lies beyond logos, beyond our ability even to reason, though perhaps not to comprehend. At my age, and having spent a life devoted to language, there is comfort and excitement — even perhaps some inchoate feeling of hope — in glimpses beyond the realm of words. There is, I have come to believe, very much outside the text. What is it though? Call it God, call it Nature, call it the Universe, call it what it seems to me now to be — having read and I’m sure misunderstood my theoretical physics — call it: an asymptote.”

Mass. Affinity. Asymptotes.

The OED: b. Relationship by blood, consanguinity; common ancestry of individuals, races, etc.; an instance of this.

And then there is

"Blood". And

Blood: Stories.

"Why did you give it that title?" people ask. There are a lot of answers. (And that, in itself, is an answer.) Here's one: As a child of the early AIDS era, I always knew queer blood is politicized and scary. Scary, thus politicized. Politicized, thus scary.

Until recently, the FDA prohibited any man who had had sex with men since 1977 from donating blood. Now, if you've been celibate for a year, you can donate. The massacre in Orlando

brought this policy back into the news, with various outlets reporting that while queers were attacked, and blood was needed, any man who had had sex with a man in the last year could not, under FDA rules, donate blood.

Blood is a reality and blood is a potent metaphor: beautiful and terrifying, wonderful and evil.

Consanguinity.Blood is life and blood is death; blood is family and blood is genocide.

Is there an opposite to blood? What is

water in our metaphors? It washes blood away, but also sustains us as we live, for much of what we are is water. Tears are made of water, salt, enzymes, hormones. They taste like oceans and look like rain.

Water is what we weep.

I weep for my queer brethren. I weep, too, for the inevitable

homonationalism as queer shoulders are put to the wheel of US imperialism and US exceptionalism; as pride is wielded for Us against Them.

But I am not feeling political today.

Sometime looking backward

into this future, straining

neck and eyes I'll meet your shadow

with its enormous eyes

you who will want to know

what this was all about

—Adrienne Rich,

"A Long Conversation"

Yesterday, my aunt, after (as they say) a (short? long? relative to what?) illness, died.

We had never lived near each other, but she was a profound influence on my life. She and her daughter, my cousin, gave me Stephen King stories when I was much too young for them.

Night Shift, Skeleton Crew. The titles are still magic to me, the covers of the old paperbacks as powerful as any personal icon I have. So much of what I became as a writer is because of those stories. So much of what I became as a writer, then, is because of her.

She was a brilliant artist, a fun and funny person, so smart, so straightforward, saucy, even, and strong as the mightiest metal. She had a magnificent life with magnificent people in it, as well as hardship, oh yes, hardship, indeed, as we all do, yes, but still: she struggled, persevered, survived, didn't let the bastards get her down.

I will miss her forever and cherish her forever. Her husband, my uncle, provided me with my middle name, and I am always proud to have been named for him, one of the best people I know.

(The cover of my book called

Blood is a picture of a man with his heart removed.)

At the wedding of my youngest uncle some years ago, my oldest uncle, this great man now a widower, gave a toast in which he said ours is a motley family of steps and halfs, of once- and twice-removeds, of marriages and unions and affinities, but in the end those designations don't much matter, because family is family, and that's who we are, and what we are, and what we have, because we love each other.

Affinity. And even more so that most important of political cries: Solidarity.

I remember that Auden kept revising his poem

"September 1, 1939", because he couldn't decide between "We must love one another or die," "We must love one another and die," or nothing at all.

Here, then, my own tentative, inadequate revision:

We must love one another or nothing at all.I loved my aunt fiercely, and I love fiercely all you queer folk out there aching and screaming and scared and willing to fight, and all who dance against the gunfire, hands held together through the pain, lips together in solidarity, lives together as we live and live and live — even if separated by oceans, even if drowning in tears — always striving, even if never reaching, like asymptotes, like believers and holy fools — as we remember and honor the dead, as we go on, as we must, you, me, all — whether strangers or the oldest of lovers, we are — we must be — a mass of friends, family, water, blood.

And I dream of our coming together

encircled driven

not only by love

but by lust for a working tomorrow

the flights of this journey

mapless uncertain

and necessary as water.

—Audre Lorde

"On My Way Out I Passed Over You and the Verrazano Bridge"

A new interview with me — the first to come out since

Blood: Stories was released — is now up at

One Story's blog, part of the publicity leading up to the

One Story Literary Debutante Ball. Many thanks to Melissa Bean for conducting the interview, and for her very kind words about the book.

Here's a taste:

MB: On that note, what inspires your stories?

MC: Daydreams and nightmares created by anxieties, fears, and desires.

I don’t write fiction for the sake of therapy, per se, but I am prone to anxiety and I have an active imagination, so it’s often the case that a story starts from one of my weird anxiety fantasies.

Read more at One Story...

This review originally appeared in the January 2006 issue of

Z Magazine. I'd forgotten about it until somebody today mentioned that it's the anniversary of most of the striking workers' demands being met (12 March 1912), and so today seemed like a good one to post this:

by Bruce Watson

New York, Viking, 2005, 337 pp.

Lawrence, Massachusetts was, at the beginning of the twentieth century, what might be called one of the greatest mill towns in the United States, but "greatest" is a difficult term, and underneath it hide all the conditions that erupted during the frigid winter of 1912 into a strike that affected both the labor movement and the textile industry for decades afterward.

Bruce Watson's compelling and deeply researched chronicle of the strike takes its name from a poem and song that have come to be associated with Lawrence, although there is, according to Watson, no evidence that "Bread and Roses" ever appeared as a slogan in Lawrence until long after 1912. This fact might suggest that Watson's position is one of a debunker, but he offers less debunking than revitalizing, and the ultimate effect of his book is to show why the romantic notions behind the "Bread and Roses" phrase do a disservice to the courage and accomplishments of the strikers.

Watson's greatest strength is his ability to weave weighty research into a narrative that is lively and seldom ponderous.

There are costs to this approach, because the minutia of a strike's planning and execution are not always suspenseful, and so, as Watson strives to hold the reader's interest there are times when the sentences sound like the narration of "America's Most Wanted" and swaths of yellow from the journalism of 1912 seem to have seeped into the book's pages.

This is a minor annoyance, though, in a book filled with vivid portraits of ordinary workers and their families, and with precise, careful renderings of an age and culture.

Again and again, Watson brings the book back to the circumstances of the immigrant workers who started the strike, and he compares their lives to those of other workers throughout the United States, to the owners and administrators of the mills, to the politicians, to the police and the soldiers who were sometimes fierce combatants with the strikers, sometimes bewildered and beleaguered sympathizers.

It would be interesting to watch a free-market ideologue respond to Bread and Roses, because again and again Watson presents damning evidence of the failures of unbridled capitalism to produce anything but misery for people who worked in the mills. He includes a budget created by one of the workers' wives; she lists such expenses as rent, kerosene, milk, bread, and meat. Watson lays out the family's other expenses, the fact that they couldn't afford to buy coal and so their only heat during the brutal winters came from the bits of wood their children could scavenge, the luxuries they couldn't buy (butter and eggs), and then comments: "Like most mill workers, the Bleskys could not afford clothes fashioned in Manhattan sweatshops from fabric made in Lawrence. ... The Bleskys each wore the same clothes until they wore out. When the strike began, Mrs. Blesky was still wearing the shawl, skirt, and shirtwaist she had bought in Poland three years earlier, just before coming to Lawrence. Ashamed of her shabby appearance, she almost never left her home."

Searching through numerous archives, Watson has unearthed one story after another like this one, and each undermines the fanciful justifications and accusations made by the mill owners, which Watson also chronicles well. To his credit, though, he does not present the owners, the politicians who supported them, and the reporters who often printed even their most outrageous lies as caricatures, creatures so obsessed with profit that they would happily trod over the people who created that profit for them. Instead, he tries to divine the self-delusions and paranoid fears that motivated the workers' many antagonists. While on the surface it may seem immoral to try to portray the masters of such misery as flawed and idealistic human beings, the result is both complex and useful, because ideology was as much a part of what created the misery as was greed.

The Lawrence strike became a national cause, and it attracted the attention of celebrities and rising stars of the labor movement, including Big Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn of the IWW and John Golden of the AF of L. The events and tactics that brought so much attention to Lawrence are particularly fascinating, and Watson does an admirable job of showing how the strikers decided to carry out the strike and advance their cause, particularly with the controversial and immensely effective "children's exodus", where the children of strikers were sent to the homes of union members in New York, Vermont, and elsewhere. With each new day and week of the strike, more groups joined in, until the strike itself became, for a short time, a panoply of people from all around the world. Numerous women, too, who had often been relegated to the background in labor struggles before, became vital players in Lawrence, and the book includes a marvelous photograph of a parade of women holding their hands high, joyous smiles on their faces as they march down the street, defying the martial law imposed on the city.

Even as more and more strands are added to the story, the tale itself stays clear. Watson manages to show how the different segments of the labor movement both aided and undermined each other, and he doesn't smooth over the conflicts that broke out when the national interests were different from the local ones. (On the whole, though, this strike was remarkably unified compared to others both before and after it.) Haywood and Flynn in particular make for great characters in the story, but Watson skillfully keeps them from stealing the stage, always bringing the story back to the lives of the workers in Lawrence, the people who would have to live with the consequences of the strike once the nation's interest turned to other events.

In the end, it is the ordinary workers who remain the most remarkable element of the Lawrence strike, as Watson tells the story, because here were people from vastly different backgrounds, experiences, religions, and even political views who found solidarity and, through this solidarity, a certain amount of success.

The epilogue is not misty-eyed about the effects and consequences of the strike, but it also offers a kind of quiet hope for the future: for all the possibilities that imaginative, energetic, and compassionate mass action can create.

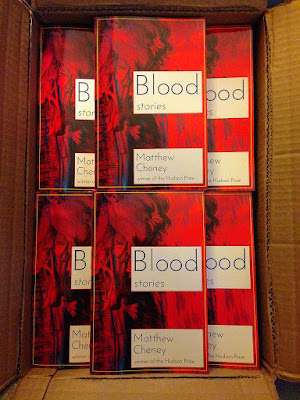

|

| a box of Blood |

Though delayed, my debut collection,

Blood: Stories, now exists. I know because I received copies of it straight from the printer. That means it's also going to arrive at the distributor within the next day or so, and from there ... out into the world.

I'll have plenty more to say later, I'm sure. For now, I'm just going to go marvel at the thing itself...

Read the rest of this post

I was honored to be the nonfiction editor for a special issue of

Fantasy magazine, part of the ever-growing

Destroy series from

Lightspeed, Nightmare, and

Fantasy — this time,

QUEERS DESTROY FANTASY!The editor-in-fabulousness/fiction editor was Christopher Barzak, the reprints editor was Liz Gorinsky, and the art editor was Henry Lien. Throughout this month, some pieces will be put online. So far,

Austin Bunn's magnificent story

"Ledge" is now available, as are our various

editorial statements. More will be released later, but most of the pieces I commissioned are only available by purchasing the

ebook [also available via

Weightless] or

paperback. There are magnificent pieces by Mary Anne Mohanraj, merritt kopas, Keguro Macharia, Ekaterina Sedia, and Ellen Kushner, and only merritt's "Sleepover Manifesto" will be online.

I owe huge thanks to all the contributors I worked with, to the other editors, to managing editor Wendy Wagner who did lots of unsung work behind the scenes, and to John Joseph Adams, who kindly asked me to join the team.

You can now order my upcoming collection Blood: Stories from the publisher, Black Lawrence Press. The book will be released in January 2016, and BLP is offering it for a bit of a discount before the publication date (it's a big book — 100,000 words — so will retail for $18.95).

Should you pre-order it? I don't know. Yes, of course, I would like you to. And if you're going to order it online, this is a good way to do it, because you'll get it pretty quickly and a larger percentage of your money will go to BLP, so you'll help a small publisher stay solvent. Once the book is published, you'll also be able to buy it from bookstores, and since I support people spending as much money as possible in local bookstores, that's a great way to get it as well.

Actually, you should probably both pre-order it and buy it from bookstores, because why would you want only one copy? You need to be able to give them away to friends — or, if you don't like the book, to enemies...

Read the rest of this post

|

| Littleton Opera House, Littleton, NH c.1900, a location in the story |

I have a new story — my first (but not last) of this year — now available on the

Conjunctions website—

"The Last Vanishing Man".

This one's a bit of a departure for me, in that it is a serious story that will not, I'm told, make you want to kill yourself after you read it. In fact, one of my primary goals when writing it was to write something not entirely nihilistic. Various people have, over the years, gently suggested that perhaps I might try writing a ... well ... a

nice story now and then.

(I actually think I've only written one story that is not nice, "Patrimony"

in Black Static last year. And maybe

"On the Government of the Living". Well, maybe

"How Far to Englishman's Bay", too. And— okay, I get it...)

So "The Last Vanishing Man" is a story that has an (at least somewhat) uplifting ending, and the good people triumph, or at least survive, and the bad person is punished, or at least ... well, I won't go into details...

Here's the first paragraph, to whet your appetite:

I saw The Great Omega perform three or four times, including that final, strange show. I was ten years old then. It was the summer of the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, a time when vaudeville and touring acts were quickly fading behind the glittering light of motion pictures and the crackling squawk of radios. What I remember of the performance is vivid, but I am wary of its vividness, as I suspect that vividness derives not from the original moment, but from how much effort I’ve put into remembering it. What is memory, what is reconstruction, what is misdirection?

Continue reading at Conjunctions...

Boomtron just published my latest Sandman Meditation, this one on Chapter Two of The Wake."Sandman Meditation?" you say. "That sounds ... vaguely familiar..."

In July 2010, I started writing a series of short pieces called

Sandman Meditations in which I proceeded through each issue of Neil Gaiman's

Sandman comic and offered whatever thoughts happened to come to mind. The idea was Jay Tomio's, and at first the Meditations were published on his Gestalt Mash site, then later

Boomtron. The basic concept was that we'd see what happened when somebody without much background in comics, who'd never read

Sandman before, spent time reading through it all.

I wrote 71 Meditations between July 2010 and June 2012, getting all the way up through

the first installment of the last story in the regular series, The Wake. 75,000 words.

And then stopped. I read Chapter 2 of

The Wake and had nothing to say. I tried writing through the lack of words, but the more I tried to write the more what I wrote nauseated me. I couldn't go on.

I got through 71 Meditations by only looking back once —

in the piece on "Ramadan", I misread a word (yes, one word) and completely misunderstood the story. When Neil gently brought the mistake to our attention, I was shocked. So I went back and re-read "Ramadan" and what I'd written about it. Though in the immediate moment, I felt like a total idiot with entire chicken farms of egg on my face, I've come to cherish that mistake, because it showed just how carefully and subtly constructed so much of

Sandman is, and how a simple slip in reading can make a text flip all around. It gave me a certain freedom, too. I'd always been terrified of making some dumb, obvious mistake in my reading of

Sandman, because I know it's so well known by its passionate fans, and I didn't want to either let them down or annoy them. Once I made that big mistake, I felt somehow freer to go wrong, and that kind of freedom is necessary for writing. I went forward, trying hard not to think about whether I was writing well or terribly, thinking well or thinking badly, reading well or reading as if I'd never learned to read at all.

But by the 71st installment, my confidence fell apart. I was terrified that I'd written nothing but drivel, and the weight of that fear pulled me back.

Why should anybody want to waste time reading what I've got to say about this? I wondered.

This is a beloved series of comics, a beloved story full of beloved characters, an intricately woven tale that I'm just blundering through blindly. I couldn't do it.

Eric Schaller kept bugging me. "So are you ever going to finish your

Sandman stuff?" he'd ask, and I'd change the subject.

I figured as more time passed, everybody would forget about my crazy reading experiment.

Jay Tomio remembered. I felt terrible for letting him down. He'd been so supportive, and I'd failed in the end. But he never seemed to hold it against me; he seemed to understand. It had been a long run. Boomtron went through some changes. The Meditations disappeared for a while. Then Jay started reconstructing, and so out of the blue one day I got a note: "Any chance you'd like to continue?" he asked.

I was terrified. A lot had changed. What would it mean to continue?

But continue I did, and continue I will. (I'll finish

The Wake in the coming weeks, then continue on to

Endless Nights. If all goes well, I think it would be fun to finish up with the recent

Overture, to return full circle back to the beginning. Fingers crossed.)

As you'll see from the new piece, I thought of

David Beronä, and I knew exactly what he'd say if he were here for me to ask about it. "Use the time you have," he'd say. "Do it now."

It's nice to be back.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 6/15/2015

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Obituaries,

Movies,

film,

horror,

Cheney publications,

video,

actors,

Christopher Lee,

video essays,

Press Play,

Add a tag

Over at Press Play, I have

a brief text essay about and a video tribute to Christopher Lee, who died on June 7 at the age of 93. Here's the opening of the essay:

Christopher Lee was the definitive working actor. His career was long, and he appeared in more films than any major performer in the English-speaking world — over 250. What distinguishes him, though, and should make him a role model for anyone seeking a life on stage or screen, is not that he worked so much but that he worked so well. He took that work seriously as both job and art, even in the lightest or most ridiculous roles, and he gave far better, more committed performances than many, if not most, of his films deserved.

Read and view more at Press Play.

Seeking something else, I came across this review I wrote in 2006 of

Paris Press's editions of two books by the extraordinary Bryher. It was first published in the

Fall 2006 issue of Rain Taxi. I don't think it's ever been put online, so I'm happy to release it into the wild here. (The quotation page numbers were included for copyediting and not in the published version, but I figure they might be useful, so I've kept them in. Also, for more samples from

The Heart to Artemis,

see this post.)

Living in a Time of Transition: Two Books by Bryher

by Matthew Cheney

Bryher

Paris Press ($19.95)

Bryher

Paris Press ($15.00)

"I found my study of history of great practical value," Bryher writes in The Heart to Artemis. "It helped me to assess the future and to be aware of change."[118] Awareness of change runs through the veins of Bryher's body of work, and Paris Press deserves much praise for bringing some of that work back into print. With the majority of her work now out of print, Bryher has been known, if she has been known at all, primarily for her long relationship with the poet H.D. and for her support of many of the major figures of the Modernist movement, but she was a fascinating writer herself, and one deeply deserving continued notice.

The daughter of a wealthy British industrialist, Bryher spent much of her childhood in Egypt, France, Greece, and elsewhere.

Her only experience of formal schooling came later, and left her mostly bitter about institutionalized education.

Again and again in

The Heart to Artemis she states that the openness of her upbringing allowed her to develop an insatiable intellectual curiosity and an independent spirit in a society structured to prevent women from having either.

"The greatest gift parents can give their children," she writes, "is experience.

It is far more valuable than either care or money." [47] Experience, though, needs an environment in which it is meaningful: "How much more peaceful the world might be if there were fewer checks upon development imposed in childhood!

I do not mean licence, there must be discipline but to save ourselves trouble we do not let children work through the various stages of development at their own time and there is too much imposition of socially acceptable ideas upon a growing mind." [21]

The most vivid sections of

The Heart to Artemis occur in the first half, as Bryher chronicles the experiences of her childhood and reflects on the changes in the world since the late Victorian era.

She was not entirely free from the imposition of socially acceptable ideas, but her experiences in different societies and cultures allowed few such ideas to sink unquestioned into her mind, and so when she began reading contemporary poetry in the early years of the twentieth century, she was particularly well prepared for the excitement of its innovations.

Surprisingly, the least memorable scenes in

The Heart to Artemis involve the many well-known writers and artists Bryher knew in her adulthood.

After the extraordinary chapters about her childhood, in which every detail is fresh and suggestive, the quicker pace and more fragmentary nature of the later scenes is a bit of a disappointment.

Though Bryher's eye in the later scenes remains sharp, she staunchly avoids writing about the intimate details of the lives of the people she knew, which makes many of the passages feel thin.

The final chapters, though, regain the richness of the first chapters, because Bryher early on recognized the dangers posed by the Nazis in Germany and the Fascists in Italy, and she became a brave and tireless activist for refugees.

She writes gracefully about her activities, conveying a sense of both moral duty and adventure, and her compassion for the people she helped is clear in the care with which she chronicles their experiences.

She ends the book with the beginning of World War Two, and the last paragraphs brilliantly and devastatingly evoke the anxiety and terror of that time.

History was Bryher's favorite subject, and most of her novels are set in the past. The Player's Boy is an odd and unsettling book about England from 1605 to 1626, the story of an apprentice to the theatre named James Sands—a boy whose masters die before they can ever train him properly, a man whose uncertainty in life reflects the uncertainties of his era. Each of the five chapters of The Player's Boy tells a mostly self-contained story of one particular time in James Sands's life, often through the stories characters relate to each other. The language is lightly Elizabethan (the Elizabethan dramatists being particular favorites of Bryher), but not in a stilted way; through careful attention to diction and to particular details of scenery, Bryher efficiently evokes the setting and circumstances of the novel, creating in a little more than two hundred pages what a less subtle and skilled writer could not do at twice the length. Because of this efficiency, The Player's Boy does not benefit from hasty reading; it requires the reader to slow down and let each sentence live.

Reading the two books together is a particularly rewarding experience, because The Heart to Artemis expands upon many of the ideas and emotions The Player's Boy suggests —most effectively, the experience of living in a time of transition. James Sands never comes to terms with the shifts in his society, he never finds a foundation for himself, and he ends up dissatisfied with life and the world. Bryher escaped this fate herself, perhaps because of her awareness of the forces of history. While she is careful to show how much she loved and needed the innovative art and artists of her time, she is also remarkably clear-eyed about the delusions artists can hold about themselves: "'It's got to be new,' we chanted because old forms were saturated with the war memories that both former soldiers and civilians wanted to forget. We were too savage, too contemptuous, but would you have had us be prudent? We did not realise at the time that it was not the concepts themselves that were at fault but the way that they had been used." [303] Such a willingness to accept the new, while also demanding honesty in its use, distinguishes all of Bryher's work, and the truth of her commitments reveals itself in the remarkably contemporary feel of her writing.

|

| sitting in my office, contemplating what to write... |

I've been wanting to try out

TinyLetter for a little while now, having subscribed to a few newsletters that use it, and so I took some time to create

a newsletter aimed at sending out information, musings, etc. about my upcoming collection, Blood: Stories, which Black Lawrence Press will release in January.

Why create such a thing when I've already got this here blog? Because I think of this blog as a more general thing, not really a newsletter. I will put all important information about

Blood here (as well as on

Twitter, and I'll make a Facebook author page one of these days), but the newsletter will have more in-depth material, such as details of the publishing process, background on the stories, etc. There will be some exclusive content and probably even some give-aways, etc. I probably should have titled it Etc., in fact... And it's not all limited to

Blood — if you take a look at

the first letter, you'll see some of the range I'm aiming for. That letter is public, and some of the future ones will be, too, but for the most part I expect to keep the letters private for subscribers only. (I've always wanted to be part of a cabal, and now I've started my own!)

One of the things I note in that first letter is that Mike Allen is

running a Kickstarter to raise funds for his fifth

Clockwork Phoenix anthology, and

all backers can now read a 2006 story of mine that Mike first published, "In Exile". This is, as far as I remember, the only story I've ever published set in the typical fantasy world of elves and wizards and all that. (To learn why, read the newsletter!) Mike made an editorial suggestion for the manuscript that completely fixed a major problem with the story, so I've always been tremendously grateful to him, and I'm thrilled that it's now available to backers of this very worthy Kickstarter.

Strange Horizons has now posted

my review of John Clute's latest collection of materials, Stay. A taste:

Even a mere glance through Stay, John Clute’s latest collection of book reviews, short stories, and lexicon entries, (or through any of Clute's books, really) will convince you that you are in the presence of genius.

But a genius of what type? The type that can turn a million candy wrappers into a surprisingly convincing small-scale replica of a rocket ship, or the type that zips to the heart of a zeitgeist faster than the rest of us? Is this genius a fox, a hedgehog, an anorak? Does it sing in seemingly effortless perfect pitch, or is its singing, like that of a dog, remarkable simply for being at all?

The desire to taxonomize is inevitable after reading even a few pages of Clute. He is a wild literary Linnaeus: obsessively compulsed to categorize. As someone generally uninterested in taxonomy, I have struggled to learn to read Clute appreciatively. I used to want to shoot his clay pigeonholes, to mock his neologistic frenzies, to clothe the emperor. But then I realized I was enjoying his work too much to do so. Clute’s imperative to categorize is contagious. I’d passed through the portal and made my way into Cluteland.

This review marks ten years of my writing for

Strange Horizons — I began as a columnist in February 2005 with a rather odd piece titled

"Walls". I stopped as a columnist after writing

fifty, since I felt like I'd done what I could do with the form for that audience, but I've continued occasionally to write reviews.

I don't do a lot with genre speculative fiction these days, since other things have taken me elsewhere, but it's nice to be back now and again at a publication that feels so much like home. I owe thanks to lots of people there, especially former editor-in-chief Susan Groppi, who first asked me to write for the magazine, current editor-in-chief (and the first, if I remember correctly, reviews editor) Niall Harrison, recent past reviews editor Abigail Nussbaum, new reviews senior editor Maureen Kincaid Speller, and book reviews editor Aishwarya Subramanian, who not only let me keep some of my bad puns and jokes, but even liked some of them!

Strange Horizons remains a unique, wonderful place out there in the wide world of the web, and it has always been an honor to be associated with it.

The first book written for adults that I ever coveted and loved and read to pieces was a short story collection: Stephen King's

Night Shift, from which my cousin read me stories when we were both probably much too young, and which was one of the first books I ever bought myself. Ever since then, short story collections have seemed to me the most wonderful of all books.

I started publishing short stories professionally with

"Getting a Date for Amelia" back in 2001. I barely remember the kid who wrote it (in the summer of 2000). I'm not a prolific fiction writer; I've been lucky enough to publish most of the stories I've written in the last decade or so, but I average only two stories a year. Fiction is the hardest thing in the world for me to write. Some stories have taken many years to find a final form. The kid who wrote "Getting a Date for Amelia" also managed to write a novel; it was mostly terrible (or, rather, not

terrible, which might be interesting. Just nothing at all special. Rather boring, in fact. An extraordinarily useful exercise, though, dragging yourself through a novel-length piece of writing, even if the end result isn't all that great). I like fragments and miniatures too much to ever write a proper novel, I expect.

And—

What? Get on with it? Ah.

Yes, I am dithering here.

Because I am about to write a sentence that still feels unreal, though I've been writing various forms of it into emails to friends for a little while now:

I am the 2014 winner of the Hudson Prize from Black Lawrence Press for an unpublished manuscript titled Blood: Stories that will be published by BLP in January 2016.The book will mostly contain reprints, and finally bring together all of the stories I've published since 2001 that are 1.) worth bringing together and that 2.) play well with each other. There are also a few unpublished stories, ones that I've never found the right home for but that felt to me like they belonged with the others, both gained and added context from/to the others, and were worth publishing. The editors at Black Lawrence Press agreed. One of the things I love about story collections is the way they can recontextualize stories, and the greatest excitement for me of this collection is that it will finally allow stories that have been scattered across a wide range of publications over many years to speak to each other.

I'm also incredibly excited to have found a publisher that is excited by what some others have considered either a fault or danger of the collection: its breadth of genres and styles. Perhaps out of sheer stubbornness and delusion, I was convinced that I could not be the only person on Earth to think the overall perspective of the work would create a coherence beyond genre or tone, that there was, in fact, a persistence of voice and vision. That's what the BLP editors told me attracted them to the manuscript, and when they said that, I knew I'd found what may be the perfect publisher for my work.

So I am excited. Beyond excited. I don't have words to convey the feeling of achieving something I've work toward for so long, something I often gave up hope of ever achieving. I wanted to write this post not only to let the world know the news, but also to preserve this moment so that, working through the more difficult parts of the experience (oh gawd, people might write reviews!), I can look back and remember what it felt like to be at this moment of triumphant possibility.

And to thank you, whoever you may be, who felt that it was worth some bits of your time and attention to read my words. I hope to continue to reward your interest.

The marvelous

Interfictions Online has now published my short story/prose poem

"On the Government of the Living".

The piece, which takes its

title from Michel Foucault but is not otherwise especially erudite, began purely as an exercise: I wanted to see if I could take what the

Turkey City Lexicon calls "White Room Syndrome" and actually make it a viable, necessary element of the story. (Whenever a writing guide says, "Don't do this!" I inevitably want to try it out...) The effect, perhaps unsurprisingly, is rather Beckettesque.

This review was first published in Rain Taxi in the spring of 2011. I'd actually forgotten all about it, but then came across it as I was reorganizing some folders on my computer. In case it still holds some interest, here it is. (Page references are to the Yale hardcover, and were for the copyeditors to double check my quotes; they weren't in the print version of the review, but I've kept them in because, well, why not...) One of the pleasures of Gabriel Josipovici’s

What Ever Happened to Modernism? is that it all but forces us — dares us, even — to argue with it.

Josipovici presents an idiosyncratic definition of Modernism, he perceives the struggles of Modernist writers and artists as fundamentally spiritual, and he frames it all by describing his disenchantment with most of the critically-lauded British fiction of the last few decades, a disenchantment that he ascribes to such fiction’s attachment to non-Modernist 19

th century desires.

The only readers likely to agree with Josipovici’s general view, then, are readers who accept his terms and share his tastes. Such readers are probably few, and they are also the readers who least need the book. It is those of us who may be sympathetic to one or another of Josipovici’s general arguments who really need it, because it is a powerfully clarifying volume, especially in its extended discussions of particular works.

“Modernism” is one of those terms that has been used in so many different ways, with so many different meanings, that anyone seeking to discuss it must first define it. In general, it is seen as both a tendency and an era, a style of artistic expression mostly occurring in the twentieth century, though with some examples or precursors in the latter part of the 19th century. Josipovici rejects all of this, for while his paragons of Modernism do fit the general periodizing, his definition of the term is far broader, and is not particularly interested in situating Modernism within borders of time. In the first chapter, he defines Modernism as “the coming into awareness by art of its precarious status and responsibilities” [11], a definition that is further refined to see Modernism as a response to the post-Medieval European world’s disenchantments. Modernism reveals itself in the “century of pain, anxiety, and despair on the part of writers, painters, and composers” [5], which Josipovici details with examples from Mallarmé, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Kafka, and Beckett. The pain, anxiety, and despair come from an unresolvable tension between an overwhelming desire to write and a doubt in art’s ability to represent the world. This tension inscribes itself in the texts, undermining or even shattering the enchanting verisimilitude of, for instance, Victorian novelists such as Dickens.

Josipovici begins What Ever Happened to Modernism?with a preface in which he tells the story of being an undergraduate student, hearing a lecture about “The English Novel Today”, seeking out the recommended writers (Anthony Powell, Angus Wilson, Iris Murdoch), and feeling a lack: “They told entertaining stories wittily or darkly or with sensationalist panache, and they obviously wrote well, but theirs were not novels which touched me to the core of my being, as had those of Kafka and Proust” (ix). He goes on to discover Borges and Claude Simon, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Saul Bellow, Georges Perec, and Aharon Appelfeld — all writers whose work he admires — but feels more and more of an outsider within English literary culture. “Occasionally I wondered why my own feelings and those of reviewers or critics were so much at odds, wondered, indeed, who was right, me or the entire establishment. I didn’t think I was mad (though of course the mad rarely do), and I did occasionally meet people who shared my tastes, so how was this anomaly to be explained?

“This little book,” he says, “is an attempt to answer that question.” (xi)

Within the question itself we can glimpse the kernels of Josipovici’s argument, assumptions, and desires. He sets up a polarity: “Who was right, me or the entire establishment?” It’s a feeling many intelligent and thoughtful people have asked (often in their youth) for centuries, and the frustration it provides can be productive, particularly in helping people define their tastes, but in and of itself it’s humorous in its naivety. The claim that What Ever Happened to Modernism? is an attempt to answer the question of why Josipovici’s experiences as a reader are different from those of people who don’t share his tastes may be true in terms of intention — he may have thought that was what he was trying to do — but it is false as a description of the book’s value, because Josipovici shows no interest in trying to understand tastes that differ from his own. He truly doesn’t seem to be able to understand how people of even moderate intelligence and education could find themselves touched to the core of their beings by works that he himself doesn’t respond strongly to, and which seem to him “to belong to a different and inferior world to that of Proust and the others” (x). Not just different, but inferior.

It should not surprise us, then, when Josipovici defines a central element of Modernism as “pain, anxiety, and despair” resulting from European culture’s growing rationalism and waning faith in unquestioned authorities and eternal verities. Over the course of the Middle Ages, perceptions of reality changed. Individualism took hold. Capitalism infiltrated economies. The Enlightenment solidified, expanded, and complexified the disenchantment, and then Romanticism reflected on it. The Victorian novel, that form which Josipovici so disdains, sought to re-enchant the world with the legerdemain of its reality effects, the verisimilitude that lulls the reader into imagined reality. Such a reality is unquestioned, unified — it does not admit the problems of representation in a fallen and fragmented world. Its pains, anxieties, and despairs are not those of the Modernist, but of the illusionist.

Josipovici’s question “Who was right, me or the establishment?” is simultaneously a cliche of individualism (the absolute individualist, unburdened by doubts, answers, perhaps with a copy of The Fountainheadin hand, “ME!”) and an expression of the assumption that prevents Josipovici from empathizing with any view other than his own, because the assumption underlying the question is that there is a right and a wrong, and that this right and wrong can be discovered and elucidated. The first chapters of the book are the weakest, because it is in them that Josipovici attempts to predict criticisms to his arguments, but he is so convinced that those criticisms must be wrong(different and inferior) that what he offers as representations of them are ridiculous: a quote from Evelyn Waugh about Picasso, a parody of Marxism (paraphrasing something Josipovici said he heard from a professor at the University of Sussex once), and a caricature of postmodernism that, were someone to represent his own conception of Modernism so badly, Josipovici would laugh off the page. He quotes an astute statement from the art historian T.J. Clark on the difficulties of writing honestly about pre-Enlightenment Europe without sounding nostalgic, but this seems pro forma — Josipovici verges, especially in the first chapters, toward far more nostalgia than Clark’s Farewell to an Idea does, because Josipovici clings to the notion that the fragmentation and dispersal of authority should cause pain, anxiety, and despair. He wants, still, for there to be one right and one wrong, and he sees “the establishment” as a monolithic and invalid authority.

He knows, though, that this despair can lead to terrible things, and he uses Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus particularly well to point to the dangers, for Doctor Faustus represents a Germany “which is in the grip of a party which believes it is possible to forge a new cultic and communal society in the post-industrial world,” and this Germany “appals and terrifies” the characters, Mann, and Josipovici. What is to be done? “Can one retain the critical insights, feel the loss as real, without at the same time opting for the demented Nazi vision of a new cult? This is the question out of which the tortured novelist, writing in distant California as the Nazi dream drags Europe to its destruction, forges one of his greatest works.” [19-20]

After these introductory pages, the book shifts more toward Josipovici’s real strengths — he moves from denigrating the mysterious forces that don’t share his opinions and perceptions to offering his interpretations of specific writers, artists, and works. In its central chapters, What Ever Happened to Modernism? is a tour de force. As the book draws connections between Albrecht Dürer, Rabelais, and Cervantes; Wordsworth and Caspar David Friedrich; Kierkegaard and everyone, the pages sing with insight. Each reader will find different thrills within the rich texture of the text. While I was familiar with some of Josipovici’s ideas about such writers as Cervantes, Kierkegaard, Kafka, and Beckett from his previous essays, I had passed over things he’d written before about Wordsworth, and so his close readings of some of Wordsworth’s most famous and most obscure poems opened those works up to me in ways I had never considered, and sent me back with passion to a writer I’d previously had little interest in. I expect most readers, especially those unfamiliar with the majority of Josipovici’s other books, will, if they can read past the polemic, find similar moments of epiphany in What Ever Happened to Modernism?.

By the end of the book, the word “Modernism” seemed to me too narrow for the tendency Josipovici described, because he convincingly shows connections between everything from ancient Greek drama to Herman Melville to Francis Bacon, suggesting that for millennia artists have concerned themselves with, if not Modernism exactly, the impulses and experiences that allow Modernism to fully reveal itself in the 19th century. What Josipovici describes is not an artistic movement or school, but a type of perception and expression present in much of the art that has been considered among the greatest of human accomplishments. The fiesty, proselytizing side of Josipovici tries hard to make it seem that everybody who has ever written about literature hates and misunderstands this tendency, but it may just be that he is uncomfortable on the side of the winners. While Proust, Kafka, Borges, et al may not be quite as popular as J.K. Rowling and Dan Brown right now, they’re a whole lot more widely read than Anthony Powell, Angus Wilson, and Iris Murdoch, and a whole lot more universally beloved than even the contemporary British writers who soak up so much of the journalistic ink that rouses Josipovici’s ire.

I suspect, though, that the ire and insights need each other, and that without the passionate sense of being a lone, sane man in a madhouse of philistines, Josipovici may not have been able to make the bold and brilliant interpretive leaps displayed throughout not only What Ever Happened to Modernism?, but his entire oeuvre of essays and fiction. Careful, moderate critics are useful, but it is the fiery, aggrieved ones who scale the highest intellectual heights, and Josipovici has scaled those heights with brio and panache.

Press Play has now posted my latest video essay,

"Terry Gilliam: The Triumph of Fantasy". It also has a short text essay to accompany it. Here's how that one begins:

In a 1988 interview with David Morgan for Sight and Sound, Terry Gilliam proposed that the most common theme of his movies had been fantasy vs. reality, and that, after the not-entirely-happy endings of Time Bandits and Brazil, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen offered the happiness previously denied, a happiness made possible by “the triumph of fantasy”.

That triumph is not, though, inherently happy. Gilliam’s occasional happy endings are not so much triumphs of fantasy as they are triumphs of a certain tone. They are the endings that fit the style and subject matter of those particular films. More often than not, his endings are more ambiguous, but fantasy still triumphs. Even poor Sam Lowry in Brazil gets to fly away into permanent delusion. Fantasy is sometimes a torment for Gilliam’s characters, but it is a torment only in that it is haunted by reality, and reality in Gilliam is a land of pain, injustice, and, perhaps worst of all, ordinariness.

Read and view more...

View Next 25 Posts