: A. R. Braun

Like some published authors, I used to think all self-published books suck. Also, like some authors, I didn't do my homework to find out if I knew what I was talking about. More diligent research has proved me wrong, as I was strapped for cash this month and had the choice of a couple of .99 books or nothing. I took the cheap books.

One of them really surprised me.

Enter Seed by Ania Ahlborn, one of the best horror novels I've ever read in my life, which made me really glad I'm about to self-publish, because now I know I'll be in good company at least some of the time. Ania possesses a descriptive prowess few authors share, and she makes you fall hard in love with her characters, which is a skill a lot of writers think they have, when they don't. Don't forget her ability to give you the straight-up creeps, for I've read few books that gave me the willies like this one.

Without giving too much away, Jack Winter is a blue-collar worker who married Aimee, a lady that's out of his league, but she doesn't mind. She just wanted to put her strict Catholic upbringing behind her. They have a couple of adorable daughters: ten-year-old Abigail and six-year-old Charlotte. The latter, nicknamed "Charlie," is the most delightful character in the book. So, of course, she's the one stricken. It seems she's got too much in common with her old man, who has a beastly past he'd put behind him . . . until now.

If you pass this one up because it's self-published, you're only hurting yourself. She's gone to the top of Amazon's horror charts, above Stephen King, and a New York agent has come calling.

Do the math and solve the equation.

A. R. BRAUN has numerous publication credits, including “NREM Sleep” in the D.O.A. anthology; “Freaks” in Downstate Story; “The Unwanted Visitors” in the Vermin anthology and “Coven” in the Heavy Metal Horror anthology, both through Rymfire eBooks; “Remember Me?” in Horror Bound magazine; and “Shades of Gray (the Symbiosis of Light and Dark)” in Micro Horror magazine.

With every deed you are sowing a seed, though the harvest you may not see.

~Ella Wheeler Wilcox

by Cassie, Associate Publicist

Dennis Baron is Professor of English and Linguistics at the University of Illinois. His book, A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution, looks at the evolution of communication technology, from  pencils to pixels. In this post, also posted on Baron’s personal blog The Web of Language, he looks at an article from Seed magazine claiming that soon we’ll all be authors.

pencils to pixels. In this post, also posted on Baron’s personal blog The Web of Language, he looks at an article from Seed magazine claiming that soon we’ll all be authors.

Researchers are predicting that Twitter is going global: in just four years, everyone on the planet–some 10 billion people–will be tweeting.

Writing in Seed magazine, neuroscientist Denis G. Pelli and graphic designer Charles Bigelow (he co-designed the Lucida font) find that the internet has brought us to the brink of universal literacy, and we’re also fast approaching universal authorship: “Nearly everyone reads. Soon, nearly everyone will publish.”

To illustrate this writing revolution, Pelli and Bigelow have assembled what can only be called an “authorgraph,” a chart plotting the number of book authors from the middle ages to the present, and the far greater number of authors using new media–blogs, Facebook, and Twitter–since the year 2000.

The researchers find that only 50 authors published a book in 1400 (a serious undercount). Then, thanks to the printing press, which came on line in the 1440s, book publication grew steadily over the centuries and peaked at just over a million book authors per year around 2000.

In contrast, the new genres enabled by the internet have shown massive growth in authorship over a far shorter time span. Pelli and Bigelow observe that before the printing press it took a scribe a year to produce a bible, while today you can tweet or update your Facebook status in seconds. They conclude, “The new media are growing 100 times faster than books.”

But comparing books to tweets leads to skewed figures. Plenty of writers in the age of print wrote not books but songs, poems, news articles, chronicles, laws, essays, and plays; they too must be considered authors (and of course scribes copied bibles, they didn’t write them, so they don’t count as authors). And, since books are still a presence in the internet age, we should remember that even in the age of Google and Wikipedia it still takes an author a year or more to write a book (yes, there’s Sarah Palin’s four-month wonder Going Rogue–but I’m only counting books with actual content).

That’s not to deny the impressive impact of the internet on authorship. Pelli and Bigelow’s figures show that blogging takes only five years to go from 60 bloggers to a million. Then social media sites take off, and Facebookers jump from an initial 50,000 to 75 million in just four years. Twitter authorship grows even faster, exploding from10,000 tweeters to a million in only three years and no end in sight–and here’s where Pelli and Bigelow go off the rails: “Extrapolation of the Twitter-author curve (the dashed line) predicts that every person will publish in 2013.”

Even hard-core fans of the internet must realize that’s just not going to happen.

I too have made the claim that because of the internet, everyone’s an author. Computers and the internet mean that more and more people are creating text and publishing it, and the internet has shown a robust ability to connect writers with readers in ways we never before imagined.

I’ve said more than once, as well, that thanks to the digital revolution, all you need to be an author is a laptop, a wi-fi card, and a place to sit at Starbucks. But my claims are hyperbolic.

Assuming that by “everyone” we mean people all over the globe, then we’re far from “nearly everyone” reading, and farther still from “nearly everyone” publishing. Pelli and Bigelow concede that authors today constitute 0.1 percent of the world’s population (according to their standards, an author is someone whose text reaches at least 100 readers, a number which excludes many bloggers and tweeters), but they’re optimistic that “Authors, once a select minority, will soon be a majority.”

That’s going to take a lot longer than four more years. True, the internet opens the possibility of authorship to the other 99.9% of the world’s 10 billion people, but first many of them will have to survive infancy, find a source of clean drinking water, learn to read and write, acquire a computer, find a reliable source of electricity, and, oh yes, locate an internet service provider. That’s assuming they’re motivated to become authors in the first place. And they live in a country where the government doesn’t block Twitter.

And even if all that happens, we’ve still got to increase the capacity of Twitter to handle all that traffic without triggering the fail whale, and we’re still a long, long way from the day when there are enough Starbucks so that everyone will have a place to sit and tweet–plus somebody’s gotta make the latte.

The challenge word on another illustration blog this week is

"seed".

John Chapman was an American pioneer nurseryman. He picked apple seeds from the discarded remains from cider mills in Pennsylvania and travelled across Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, planting apple trees. He became an American legend because of his kind and generous ways, his great leadership in conservation, and the symbolic importance of apples. He came to be known as "Johnny Appleseed".

He was also a missionary for the

Church of the New Jerusalem,(also known as the Swedenborgian Church), teaching the theological doctrines contained in the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. The Swedenborgian Church counted

Walt Whitman,

Helen Keller,

Andrew Carnegie and

Stephen King among its members.

The popular image of Johnny Appleseed had him spreading apple seeds randomly. However, he planted nurseries rather than orchards, built fences around them to protect them from livestock, left the nurseries in the care of a neighbor who sold trees on shares. Appleseed's "caretakers" were asked to sell trees on credit, if at all possible, but he would accept corn meal, cash or used clothing in barter. Johnny Appleseed dressed in the worst of the used clothing he received, giving away the better clothing he received in barter. He wore no shoes, even in the snowy winter. There was always someone in need he could help out, for he did not have a house to maintain. He spent a good portion of his time traveling from home to home on the frontier. He would tell stories to children, spread the Swedenborgian gospel (

"news right fresh from heaven") to the adults, receiving a floor to sleep on for the night, sometimes supper in return. He would often tear a few pages from one of Swedenborg's books and leave them with his hosts. He made several trips back east, both to visit his sister and to replenish his supply of Swedenborgian literature. He typically would visit his orchards every year or two and collect his earnings.

Johnny Appleseed's beliefs made him care deeply about animals. His concern extended even to insects. One cool autumn night, while lying by his campfire in the woods, he observed that the mosquitoes flew into the fire and were burnt. Johnny, who wore a tin pot on his head, which served as both as a hat and a cooking vessel, filled it with water and quenched the fire. He remarked, “God forbid that I should build a fire for my comfort, that should be the means of destroying any of His creatures.”

It has been suggested that Johnny may have had

Marfan Syndrome, a rare genetic disorder. One of the primary characteristics of Marfan Syndrome is extra-long and slim limbs. All sources seem to agree that Johnny Appleseed was slim, but while other accounts suggest that he was tall,

Harper's Magazine described him as "small and wiry."

Those who propose the Marfan theory suggest that his compromised health may have made him feel the cold less intensely. His long life, however, suggests he did not have Marfan's, and while Marfan's is closely associated with death from cardiovascular complications, Johnny Appleseed died in his sleep, most likely from pneumonia.

Despite his charity, Johnny Appleseed left an estate of over 1,200 acres of valuable nurseries to his sister, worth millions even then, and far more now. He could have left more if he had been diligent in his bookkeeping.

In addition to my illustration, I have included my original inked pencil sketch, before I added color.

In New England, in Autumn, there is a lot that is beautiful. Here is a neat article about small town libraries in Western MA with an attractive slide show to go along with it. I’ve made a Flickr set of the libraries I’ve been to with one photo per library. They’re not all small town libraries, but they’re good for looking at as well. [thanks rob!]

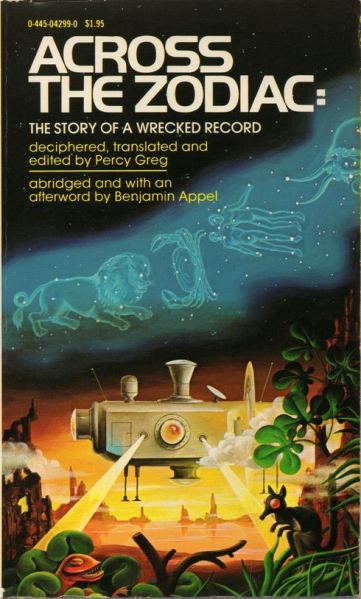

Although there had been interest in Mars earlier, towards the end of the nineteenth century there was a sudden surge of novels describing travel to the red planet. One of the earliest was Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac (1880) which set the pattern for early Mars fiction by framing its story as a manuscript found in a battered metal container. Greg obviously assumed that his readers would find the story incredible and sets up the discovery of the ‘record’, as he calls it, by a traveler to the USA to distance himself from the extraordinary events within the novel. The space traveler is an amateur scientist who has stumbled across a force in Nature he calls ‘apergy’ which conveniently makes it possible for him to travel to Mars in his spaceship. When he arrives there, he discovers that the planet is inhabited. Since then, the conviction that beings like ourselves live on Mars has constantly fed writings about the planet. The American astronomer

Although there had been interest in Mars earlier, towards the end of the nineteenth century there was a sudden surge of novels describing travel to the red planet. One of the earliest was Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac (1880) which set the pattern for early Mars fiction by framing its story as a manuscript found in a battered metal container. Greg obviously assumed that his readers would find the story incredible and sets up the discovery of the ‘record’, as he calls it, by a traveler to the USA to distance himself from the extraordinary events within the novel. The space traveler is an amateur scientist who has stumbled across a force in Nature he calls ‘apergy’ which conveniently makes it possible for him to travel to Mars in his spaceship. When he arrives there, he discovers that the planet is inhabited. Since then, the conviction that beings like ourselves live on Mars has constantly fed writings about the planet. The American astronomer

pencils to pixels. In this post, also posted on Baron’s personal blog

pencils to pixels. In this post, also posted on Baron’s personal blog

I grew up in NYC and still have cousins there, immersed in a good old fashioned NYC Jewish culture. One of my young cousins insisted that "there was a guy who went around planting apple trees, and his name was Johnny Applestein".

Ain't childhood grand?

Love the illustration