new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: renaissance, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 15 of 15

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: renaissance in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Celine Aenlle-Rocha,

on 9/18/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Literature,

Philosophy,

Thomas Mann,

Language,

thomas hardy,

renaissance,

francis bacon,

beethoven,

Charles Perrault,

*Featured,

modern literature,

Ben Hutchinson,

European identity,

Late Style and its Discontents,

Lateness and Modern European Literature,

modern european literature,

modernism in literature,

post-Enlightenment,

The old age of the world,

Add a tag

At the home of the world’s most authoritative dictionary, perhaps it is not inappropriate to play a word association game. If I say the word ‘modern’, what comes into your mind? The chances are, it will be some variation of ‘new’, ‘recent’, or ‘contemporary’.

The post The old age of the world appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Marissa Lynch,

on 9/4/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

renaissance,

Europe,

*Featured,

medici,

Classics & Archaeology,

italian history,

italian renaissance,

18th century poetry,

Alessandro de' Medici,

Catherine Fletcher,

multiracial familes,

The Black Prince of Florence,

The Spectacular Life and Treacherous World of Alessandro de' Medici,

Books,

History,

Add a tag

The Medici, rulers of Renaissance Florence, are not the most obvious example of a multiracial family. They’ve always been part of the historical canon of “western civilization,” the world of dead white men. Perhaps we should think again. A tradition dating back to the sixteenth century suggests that Alessandro de’ Medici, an illegitimate child of the Florentine banking family who in 1532 became duke of Florence, was the son of an Afro-European woman.

The post A look at historical multiracial families through the House of Medici appeared first on OUPblog.

Here's a post that originally ran in the now-defunct Edge of the Forest

Duchessina: A Novel of Catherine de' Medici Carolyn Meyer

Duchessina: A Novel of Catherine de' Medici Carolyn Meyer

Catherine de’Medici is mostly known as the power behind the throne during the reigns of her ineffective sons, the kings of France. History has also placed her with the blame of the St. Bartholomew’s massacre in which over two thousand Huguenots were killed. Not much is known about the early life of Catherine de’Medici, beyond her use as a pawn in various Florentine power struggles.

In this latest installment in her Young Royals series, Carolyn Meyer’s imagination fills in the gaps in her story. Orphaned as an infant, she is known as Duchessina, the little Duchess after her duchy in Urbino. She grows up in Florence, in the Plaza de Medici under the watchful eye of her cardinal uncle, the future Pope Clement VII. After her guardian uncle assumes the pontificate, Italy is plunged into several wars against the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Catherine is eight at the time and does not completely understand the political machinations at play as the citizens of Florence take the excuse to reassert their independence from Medici rule. Catherine is taken as a war hostage and sent to an anti-Medici convent. She then changes convents from time to time as the turmoil mounts and recedes. Eventually, Catherine is taken to Rome to be with the Pope as he arranges her marriage to the French dauphin.

Once in France, Catherine’s life does not become easier. It is obvious her new husband’s affections lie elsewhere. But, with the skills she has learned, she makes a place for herself.

This is an exciting tale with historic splendor, adventure, love, and true friendship. Unfortunately, the historical notes at the end act mainly as an epilogue to her life, not as illuminating background information to the events of the book. During the Italian Wars, the young Catherine does not fully understand the political maneuverings at play, and as she is the narrator, neither does the reader. Also, there is nothing to let the reader know which details of the story are fact, and which sprung from Meyer’s mind. It is also interesting to note that Catherine’s speaking voice is the same at the age of three as it is as an adult.

(note-- I did go an read an adult biography of her, Leonie Frieda's Catherine de Medici: Renaissance Queen of France, which I reviewed here in 2007)

Book Provided by... The Edge of the Forest, for review

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links. Read my full disclosure statement.

By: Alice,

on 2/7/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

renaissance,

musica,

performance,

sheet music,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

early music,

authentic editions,

Francis Steele,

Griselda Sherlaw-Johnson,

historical context,

Musica Dei donum,

original manuscripts,

practical format,

Renaissance music,

Sally Dunkley,

Sospiri Choir,

dunkley,

donum,

sospiri,

sally,

dtiiy3grilo,

griselda,

clerkes,

Add a tag

How can modern singers recreate Renaissance music? The Musica Dei donum series by Oxford University Press explores lesser known works of the Renaissance period. Early music specialists and series editors Sally Dunkley and Francis Steele have gone back to the original manuscripts to create authentic editions in a practical format for the 21st century singer. Every piece includes an introduction to the work and its composer, tying together historical context with performance issues and notes are included by pre-eminent performers and performance scholars in the field of early music.

Sally Dunkley, series editor of Musica Dei donum, speaks to Griselda Sherlaw-Johnson, choral promotion specialist, about the series and the importance of performing from reliable editions. The Sospiri Choir performs.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sally Dunkley was a student at Oxford University, where she sang with the pioneering group the Clerkes of Oxenford. Since then, her career as a professional consort singer has developed hand-in-hand with continuing in-depth study of the music as editor, writer, researcher, and teacher. She is a founder member of The Sixteen and sang with the Tallis Scholars.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition.

The post In conversation with Sally Dunkley appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

Smoore,

on 1/29/2013

Blog:

Great Books for Children

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

YA,

children's books,

Young Adult,

Historical Fiction,

Renaissance,

Mona LIsa,

Leonardo da Vinci,

The Arts,

YA (Young Adult),

Napoli,

Add a tag

If you’re a fan of historical fiction, then Donna Jo Napoli‘s YA novel The Smile is for you. It tells the story of fifteen-year-old Elisabetta, the girl later immortalized as Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Monna Elisabetta hopes to marry for love, but knows she’s destined for an arranged marriage. As members of the lesser nobility in Florence, Elisabetta’s family needs her to marry well and she is bound by the limited role prescribed to her. But Elisabetta, unconventional and strong, meets a boy she can love, Guiliano de’ Medici. Against all odds and due to the introduction by her father’s famous friend, Leonardo da Vinci, Elisabetta meets the Medici family, the most powerful and wealthy family in Florence. She and the youngest son, Giuliano meet and fall in love. But can their love survive the violent political upheavals of the Renaissance and the overthrow of the Medici rule? In Napoli’s hands, the mysterious Mona Lisa smile is created from love, loss, poignancy and passion.

By: Alice,

on 12/8/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

shakespeare,

Geography,

renaissance,

mars,

John Donne,

astrology,

astronomy,

marlowe,

place of the year,

Copernicus,

john evelyn,

galileo,

Humanities,

POTY,

Social Sciences,

Kepler,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Middleton,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

OSEO,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

Claude Mylon,

Francois de Verdus,

Gascoigne,

Girolamo Preti,

John Skelton,

Marilyn Deegan,

Robert Burton,

Samuel Sorbière,

Thomas Hobbes,

Thomas Stanley,

William Lilly,

Literature,

Add a tag

By Marilyn Deegan

The new discoveries of the Mars rover Curiosity have greatly excited the world in the last few weeks, and speculation was rife about whether some evidence of life has been found. (In actuality, Curiosity discovered complex chemistry, including organic compounds, in a Martian soil analysis.)

Why the excitement? Well, astronomy, cosmology, astrology, and all matters to do with the stars, the planets, the universe, and space have always fascinated humankind. Scientists, astrologers, soothsayers, and ordinary people look up to the heavenly bodies and wonder what is up there, how far away, whether there is life out there, and what influence these bodies have upon our lives and our fortunes. Were we born under a lucky star? Will our horoscope this week reveal our future? What is the composition of the planets?

Astronomy is one of the oldest natural sciences, but it was the invention of the telescope in the early 17th century that advanced astronomy into a science in the modern sense of the word. Throughout the course of the 16th and 17th centuries, Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, and others challenged the established Ptolemeic cosmology, and put forth the theory of a heliocentric solar system. The Church found a heliocentric universe impossible to accept because medieval Christian cosmology placed earth at the centre of the universe with the Empyrean sphere or Paradise at the outer edge of the circle; in this model, the moral universe and the physical universe are inextricably linked. (This is a model that is typified in Dante’s Divine Comedy.)

Authors from John Skelton (1460-1529) to John Evelyn (1620-1706) lived in this same period of great change and discovery, and we find a great deal of evidence in Renaissance writings to show that the myths, legends, and scientific discoveries around astronomy were a significant source of inspiration.

The planets are of course not just planets: they are also personifications of the Greek and Roman gods; Mars is a warlike planet, named after the god of war. Because of its red colour the Babylonians saw it as an aggressive planet and had special ceremonies on a Tuesday (Mars’ day; mardi in French) to ward off its baleful influence. We find much evidence of the warlike nature of Mars in writers of the period: Thomas Stanley’s 1646 translation Love Triumphant from A Dialogue Written in Italian by Girolamo Preti (1582-1626) is a verbal battle between Venus and her accompanying personifications (Love, Beauty, Adonis) and Mars (who was one of her lovers) and his cohort concerning the superior powers of love and war. Venus wins out over the warlike Mars: a familiar image of the period.

John Lyly’s play The Woman in the Moon (c.1590-1595) also personifies the planets and plays on the traditional notion that there is a man in the moon. Lyly’s use of the planets is thought to reflect the Elizabethan penchant for horoscope casting. The warlike Mars versus Venus trope is common throughout the period, and it appears in the works of Shakespeare, Marlowe, Middleton, Gascoigne, and most of their contemporaries. A search in the current Oxford Scholarly Editions Online collection for Mars and Venus reveals almost 300 examples. Many writers of the period also refer to astrological predictions; Shakespeare in Sonnet 14 says:

Not from the stars do I my judgement pluck,

And yet methinks I have astronomy,

But not to tell of good or evil luck,

Of plagues, of dearths, or seasons’ quality;

This is thought to be a response to Philip Sidney’s quote in ‘Astrophil and Stella’ (26):

Who oft fore-judge my after-following race,

By only those two starres in Stella’s face.

Thomas Powell (1608-1660) suggests astrological allusions in his poem ‘Olor Iscanus’:

What Planet rul’d your birth? what wittie star?

That you so like in Souls as Bodies are!

…

Teach the Star-gazers, and delight their Eyes,

Being fixt a Constellation in the Skyes.

While there is still much myth and metaphor pertaining to heavenly bodies in 17th century literature, there is increasing scientific discussion of the positions of the planets and their motions. To give just a few examples, Robert Burton’s 1620 Anatomy of Melancholy discusses the new heliocentric theories of the planets and suggests that the period of revolution of Mars around the sun is around three years (in actuality it is two years).

In his Paradoxes and Problemes of 1633, John Donne in Probleme X discusses the relative distances of the planets from the earth and quotes Kepler:

Why Venus starre onely doth cast a Shadowe?

Is it because it is neerer the earth? But they whose profession it is to see that nothing bee donne in heaven without theyr consent (as Kepler sayes in himselfe of all Astrologers) have bidd Mercury to bee nearer.

The editor’s note suggests that Donne is following the Ptolemaic geocentric system rather than the recently proposed heliocentric system. In his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions of 1623 Donne castigates those who imagine that there are other peopled worlds, saying:

Men that inhere upon Nature only, are so far from thinking, that there is anything singular in this world, as that they will scarce thinke, that this world it selfe is singular, but that every Planet, and every Starre, is another world like this; They finde reason to conceive, not onely a pluralitie in every Species in the world, but a pluralitie of worlds;

There are also a number of letters written in the 1650s and 1660s between Thomas Hobbes and Claude Mylon, Francois de Verdus, and Samuel Sorbière concerning the geometry of planetary motion.

William Lilly’s chapter on Mars in his Christian Astrology (1647), is a blend of the scientific and the metaphoric. He is correct that Mars orbits the sun in around two years ‘one yeer 321 dayes, or thereabouts’, and he lists in great detail the attributes of Mars: the plants, sicknesses, qualities associated with the planet. And he states that among the other planets, Venus is his only friend.

There are few areas of knowledge where myth, metaphor, and science are as continuously connected as that pertaining to space and the universe. Our origins, our meaning systems, and our destinies — whatever our religious beliefs — are bound up with this unimaginably large emptiness, furnished with distant bodies that show us their lights, lights which may have been extinguished in actuality millenia ago. Only death is more mysterious, and many of our beliefs about life and death are also bound up with the mysteries of the universe. That is why we remain so fascinated with Mars.

Marilyn Deegan is Professor Emerita in the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College, University of London. She has published widely on textual editing and digital imaging. Her book publications include Digital Futures: Strategies for the Information Age (with Simon Tanner, 2002), Digital Preservation (edited volume, with Simon Tanner, 2006), Text Editing, Print and the Digital World (edited volume, with Kathryn Sutherland, 2008), and Transferred Illusions: Digital Technology and the Forms of Print (with Kathryn Sutherland, 2009). She is editor of the journal Literary and Linguistics Computing and has worked on numerous digitization projects in the arts and humanities. Read Marilyn’s blog post where she looks at the evolution of electronic publishing.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) is a major new publishing initiative from Oxford University Press. The launch content (as at September 2012) includes the complete text of more than 170 scholarly editions of material written between 1485 and 1660, including all of Shakespeare’s plays and the poetry of John Donne, opening up exciting new possibilities for research and comparison. The collection is set to grow into a massive virtual library, ultimately including the entirety of Oxford’s distinguished list of authoritative scholarly editions.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World – the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Written in the stars appeared first on OUPblog.

.jpg?picon=1621)

By:

DIANE SMITH,

on 6/2/2012

Blog:

DIANE SMITH: Illo Talk

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

girl,

flowers,

mural,

DVD,

Renaissance,

Michelangelo,

panel,

strawberry,

contrat,

Santa Maria Sun,

Add a tag

Well, lots to tell today. First of all, I did a phone interview with the Santa Maria Sun last week (a local weekly paper) and it is in this week's issue! Exciting stuff for me - you can check it out here.

Secondly, I was pretty frustrated with yesterday's progress - or lack thereof. I didn't really have the time that's needed to spend on the strawberry girl, so I had to leave her in a pretty poor state - I hate to walk away from something without some degree of resolution. Then, this morning we ended our history study of the Renaissance for the school year with a biography DVD on Michelangelo. To see his amazing work and then go out to the garage to my mural was rather humbling as an artist.

Anyway, I am happy to say that I was able to solve - or at least improve - several issues on the strawberry panel today. I fixed skin tones, proportions, and adjusted contrast (particularly the background wave vs. figure's skin tone). I spent a lot of time trying to get her arms and hands in believable positions - grrrrrr. I worked on the flowers and strawberries, but there is work to be done there still - in this case, I need to tone down the contrast and have the seeds blend in a bit more.

One of my favorite details today is the hair - I gave her some curls and I like the color (I thought the strawberry girl should have red hair).

By: Alice,

on 3/2/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Past and Present,

History,

renaissance,

translation,

Europe,

catholic church,

Pope Pius V,

Lent,

Benedict XVI,

*Featured,

Counter Reformation,

liturgical reform,

Medieval History,

Natalia Nowakowska,

Roman Missal,

Somerville Historian,

liturgical,

missal,

bishops,

pius,

nowakowska,

Add a tag

By Natalia Nowakowska

As the Catholic Church embarked upon its observance of Lent last week, many congregations will be holding in their hands brand new, bright red liturgical books — copies of the new English translation of the Roman Missal (the service book for Catholic Mass), introduced throughout the English-speaking world at the end of 2011 on the instructions of the Vatican.

This is not a new experience for Catholic congregations and clergy. The rare book collections of the world’s research libraries are full of the ‘new’ liturgical books produced for European dioceses between 1478 and 1500, on the orders of bishops making enthusiastic use of the recently developed printing press. Some of these books, missals printed on vellum in full folio size, are too heavy for me to pick up. Others, tiny breviaries with heavily-thumbed pages, would fit in your pocket, or that of a late medieval priest. In their prefaces, bishops explained that the point of printing these new liturgical books was to reform the church. Their aim was to provide parishes with new liturgies which were an improvement upon the service-books already in use, both the “crumbling” liturgical manuscripts from which communities had been praying for centuries, and recent, pirated printed editions. This fifteenth-century initiative was reprised during the Counter Reformation; echoing the actions of late medieval North European bishops, Pope Pius V’s Breviarium Romanum (1568) and Missale Romanum (1570) provided the entire Catholic world with new liturgical editions in Europe and beyond. The printing of improved liturgical books was therefore at the forefront of many high clerical minds in Renaissance Europe, just as it is a priority for the Vatican today.

Pope Pius V by El Greco. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The links between these Renaissance-era projects and what is currently happening in English-speaking Catholic churches go beyond a general impulse by high clergy to roll out improved worship-books, however. I’ve been struck by how similar the language used by fifteenth-century bishops, Pius V, and the current Roman Catholic hierarchy is. Late medieval bishops, in their neatly printed prefaces, complained bitterly at the “corruption,” “distortion,” and “manifest errors” of old liturgical books. The provision of the 2011 Roman missal is, meanwhile, justified with reference to the oversimplified, “plain,” and possibly inauthentic words of the earlier translation. Fifteenth-century prelates stressed that an authorised, printed liturgy would ensure a “unanimity” in worship which symbolised the essential unity of the church; the modern Congregation of Rites states that the new missal translations will function as “an outstanding sign and instrument of… integrity and unity.” Late medieval bishops took care to stress the academic credentials of the clergy-scholars who had prepared the new editions;

Benedict XVI has thanked the “expert assistants” who worked on the new missal, “offering the fruits of their scholarship.” The language of liturgical reform, corruption and renewal, unity and authenticity, which we hear today is also that of the sixteenth and fifteenth-century church, which had in turn inherited it from the early medieval church.

New books, same story. Yet the introduction of new books for worship is about power and authori

By: Emily Smith Pearce,

on 5/14/2011

Blog:

Emily Smith Pearce

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Siena,

early Renaissance,

Italian art,

Travel,

history,

Art,

Culture,

Madonna,

painting,

art history,

Renaissance,

mother,

Italy,

Italian,

Museum,

nursing,

La Leche League,

breastfeeding,

Add a tag

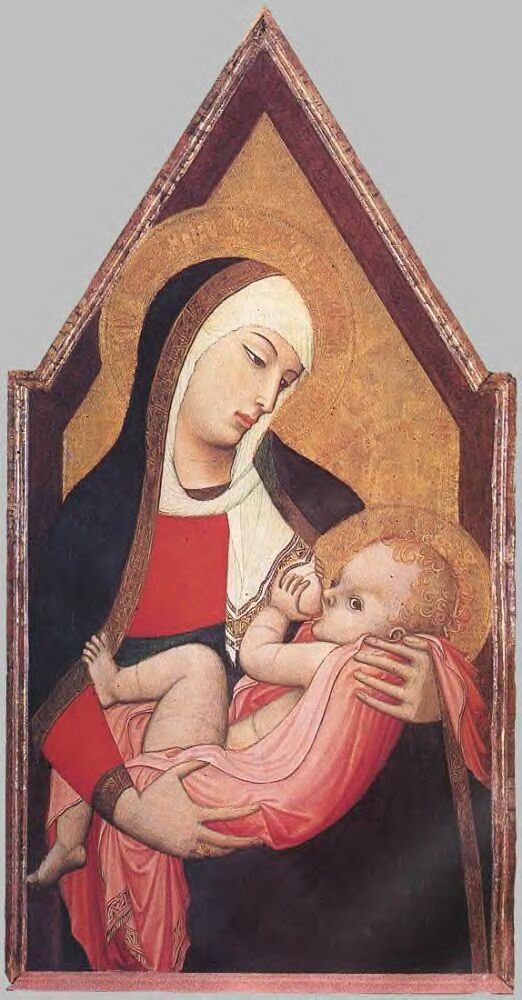

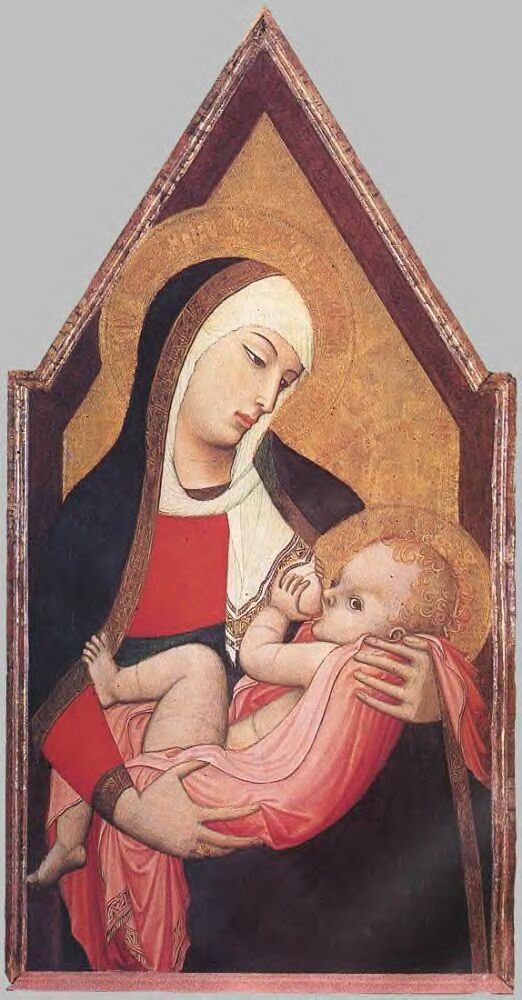

Madonna del’latte, Ambrogio Lorenzetti c. 1330

I really enjoyed the museums in Siena in part because they were small enough to manage with children, and not so packed. But the best part was their troves of early Renaissance art. I like the early stuff because it’s not so all-fired perfect like the late Renaissance art. During the early period, artists had figured out a few things about perspective, but they hadn’t yet cracked the whole code.

The art from the early period also seems brighter and more colorful than the later Renaissance. I find myself relating to it because it’s more like what I’d want to create myself. Perfection in artwork doesn’t really interest me that much, probably because I’m living after the invention of photography. So the beautiful but imperfect early Renaissance paintings (as well as pre-Renaissance works) have an almost modern feel to me.

Disclaimer: this isn’t an all that scholarly perspective, so bear that in mind.

St. Bernardino Preaching, by Sano di Pietro (above)—This scene takes place in the same Piazza del Campo from my previous post. I couldn’t find a better image of it, but in real life the colors are much brighter. The building behind St. Bernardino is the color of papaya flesh.

(detail from The Siege of the Castle of Montemassi, by Simone Martini)

The image above is just a tiny bit of a beautiful and famous painting. You can see the artist has made an attempt to show the dimensionality of the castle, but it’s still a bit flat, with an almost cubist feeling. I love it.

Our favorite pieces in the museum were the nursing Madonnas. I had never seen anything like them and was so moved by their tenderness. Whoever thought of Mary breastfeeding Jesus? Evidently plenty of artists have, but I hadn’t. I found the images so intimate, so human. So different from some other Madonnas where she’s looking away from baby Jesus, holding him like she’s not sure whose kid this is but would someone please take him?

Evidently there are a lot of these lactating Madonnas from 14th century Tuscany. According to Wikipedia, they were “something of a visual revolution for the theology of the time, compared to the Queen of Heaven depictions.”

Madonna del latte, Paolo di Giovanni Fei

“During the Council of Trent in the mid-16th century, a decree against nudity was issued, and the use of the Madonna Lactans iconography began to fade away.”

Sigh. At least they didn’t burn them.

The coolest thing about seeing these paintings was how much my small children responded to them. I think the idea of baby Jesus being so like themselves, so like oth

By: Kirsty,

on 10/20/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

gucci,

shoes,

bags,

schwarz,

slim,

ulinka rublack,

rublack,

ulinka,

braids,

History,

UK,

fashion,

renaissance,

A-Featured,

clothes,

italy,

Early Bird,

dressing up,

Add a tag

By Ulinka Rublack

I will never forget the day when a friend’s husband returned home to Paris from one of his business trips. She and I were having coffee in the huge sun-light living-room overlooking the Seine. We heard his key turn the big iron door. Next a pair of beautiful, shiny black shoes flew through the long corridor with its beautiful parquet floor. Finally the man himself appeared. “My feet are killing me!”, he exclaimed with a veritable sense of pain. The shoes were by Gucci.

We might think that these are the modern follies of fashion, which only now beset men as much as women. My friend too valued herself partly in terms of the wardrobe she had assembled and her accessories of bags, sunglasses, stilettos and shoes. She had modest breast implants and a slim, sportive body. They were moving to Dubai. In odd hours when she was not looking after children, going shopping, walking the dog, or jogging, she would write poems and cry.

Yet, surprisingly, neither my friend nor her husband would seem very much out of place at around 1450. Men wore long pointed Gothic shoes then, which hardly look comfortable and made walking down stairs a special skill. In a German village, a wandering preacher once got men to cut off their shoulder-long hair and slashed the tips of the pointed shoes. Men and women aspired to an elongated, delicate and slim silhouette. Very small people seemed deformed and were given the role of grotesque fools. Italians already wrote medical books on cosmetic surgery.

We therefore need to unlock an important historical problem: How and why have looks become more deeply embedded in how people feel about themselves or others? I see the Renaissance as a turning point. Tailoring was transformed by new materials, cutting, and sewing techniques. Clever merchants created wide markets for such new materials, innovations, and chic accessories, such as hats, bags, gloves, or hairpieces, ranging from beards to long braids. At the same time, Renaissance art depicted humans on an unprecedented scale. This means that many more people were involved in the very act of self-imaging. New media – medals, portraits, woodcuts, genre scenes – as well as the diffusion of mirrors enticed more people into trying to imagine what they looked like to others. New consumer and visual worlds conditioned new emotional cultures. A young accountant of a big business firm, called Matthäus Schwarz, for instance, could commission an image of himself as fashionably slim and precisely note his waist measures. Schwarz worried about gaining weight, which to him would be a sign of ageing and diminished attractiveness. While he was engaged in courtship, he wore heart-shaped leather bags as accessory. They were green, the colour of hope. Hence the meaning of dress could already become intensely emotionalized. The material expression of such new emotional worlds – heart-shaped bags for men, artificial braids for women, or red silk stockings for young boys – may strike us as odd. Yet their messages are all familiar still, to do with self-esteem, erotic appeal, or social advancement, as are their effects, which ranged from delight in wonderful crafting to worries that you had not achieved a look, or that someone just deceived you with their look. In these parts of our lives the Renaissance becomes a mirror which leads us back in time to disturb the notion that the world we live in was made in a modern age.

Ever since the Renaissance, we have had to deal with clever marketing as well as the vexing questions of what images want, and what we want from images, as well as whether clothes wear us or we wear them.

Ulinka Rublack is Senior Lecturer in early modern European history at Cambridge University and a Fellow of St John’s College. Her latest

By:

Nina Mata,

on 9/24/2010

Blog:

Beautifique

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

old fashioned,

old painting,

tancredi,

texture painting,

Illustrations,

digital painting,

renaissance,

masks,

good and evil,

book cover illustration,

nina mata illustration,

beautifique,

Add a tag

I was looking through my old college archives and found this renaissance inspired (digital) painting I did during my junior yr (or was it senior yr?) of college. Since this weeks topic is old fashioned, I thought ‘well you can’t get anymore old fashioned than this!’ It’s taking a lot of restraint not to render the rough edges of this, but I think it’s good leaving the past unrendered, it’s easier to see how much ones evolved.

Have fab weekend yall! xoxo

Primavera by Mary Jane Beaufrand

Publisher: Little, Brown

Release date: March 2008

REVIEW FROM ARC

Overview: Flora Pazzi was as close to royalty as you could get in Renaissance Italy. Born to a family that rivaled the Medicis, Flora was the “forgotten” sister – the youngest and the plainest. She loved her garden and her grandmother. Through Flora’s meanderings, the reader is exposed to the intrigues of her time – her father’s attempts to first join with the Medicis, and then overthrow them – and the downfall of her family as a result of the plotting. Flora survives her family’s decimation and lives to tell her story.

Love, history, intrigue, action, disaster and triumph run through this narration. Flora is a likable girl with a spark. Definite read-alike for Karen Cushman fans.

© Elizabeth Burns of A Chair, A Fireplace & A Tea Cozy

By: Bruce K. Hollingdrake,

on 2/14/2009

Blog:

The Bookshop Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Elsewhere on the Net...,

News & Opinions,

Bits & Pieces,

Clay Shirkey,

Edna St Vincent Milay,

internet,

renaissance,

Gutenberg,

Brick and Mortar Thoughts,

Naomi Klein,

Add a tag

When books become available and affordable, the value of reading and writing became apparent. Ideas could be spread rapidly. When people could read they could learn more from others and from the past. Things started to change very rapidly (for the times). Can you imagine how exciting it would have been to live during the renaissance?

By: Mike,

on 1/10/2008

Blog:

Sugar Frosted Goodness

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

hipno,

SFG: Science Fiction,

Science Fiction,

robots,

computers,

sun,

Mike Cressy,

SFG: Robots,

Renaissance,

snakes,

Sci Fi,

devil,

moon,

Add a tag

Sci Fi art is some of my favorite, especially retro. Funny I don't care to read Sci Fi anymore but the images can be very cool. I'll be posting some more Sci Fi art later today...

By: Jennie,

on 8/7/2007

Blog:

Biblio File

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Edge of the Forest,

Biography,

China,

Taiwan,

France,

Renaissance,

Laura Tyson Li,

Madame Chiang Kai Shek,

Catherine de Medici,

Add a tag

I promise kid/YA books later this week, today's more adult non fiction, but with really good reason!

I have reviews up today in the new issue of Edge of the Forest. Head over there to read lots of reviews and cool stuff, as well as my thoughts on Leap and Duchessina: A Novel of Catherine de' Medici.

Now, when reviewing a work of historical fiction, it's always nice to know something about the time period. If you're reviewing a novelization of someone's life, you should know something about that person besides what Wikipedia and Biography Resource Center (my favorite biography database) can give you.

So, I turned to

Catherine de Medici: Renaissance Queen of France by Leonie Frieda.

This is an exhaustive look at a complicated woman. Catherine was Queen of France, and mother to 3 kings of France. She held most of the power during the religious civil wars, was a contemporary of Queen Elizabeth (Elizabeth's "Frog" was Catherine's youngest son) and history has placed the blame for the Saint Bartholomew's Day massacre squarely at Catherine's feet.

Frieda has tried to free Catherine of this blame-- she paints a picture of a surgical assassination gone horribly wrong but... the fact that she wasn't guilty of massacre, just ordering the political killings of a dozen men? I'm not entirely sure that makes her better.

Frieda writes a compelling story about a place and time period I know little about. She explains context extremely well and her story is well researched and well told-- for my research, I really only needed the first few chapters, but I was so intrigued by Frieda's portrait that I had to continue reading.

There are 3 inserts of color photographs and paintings that serve as great visual aids and I really appreciated the "Cast of Characters" at the beginning of the book--it's hard to keep all those Henri's straight, plus the ever-changing Duke of Guise...

If you like biography, France, powerful women, religious history, or Renaissance history, I recommend this book.

Another powerful woman who is often a controversial figure is Madame Chiang Kai Shek.

In

Madame Chiang Kai-shek: China's Eternal First Lady by Laura Tyson Li, we get another look at a complicated and complex person.

I think Li really wanted this to be a sympathetic view of Madame Chiang Kai- Shek, but after a certain point, the material just wouldn't let her. I learned a lot about Taiwan, as well as the craziness that was the first 50 years of the twentieth century in China. (1911 brought the overthrow the the Qing Dynasty and the new Republic, which never fully gained control of all of China-- much was ruled by warlords, then the Communists were making noises so there was that war, then the Japanese were invading, so there was that war, then back to the Communists...)

After reading this book, I finally understood why Communism succeeded in China and why many saw it as a much better alternative to Chiang's government. But oh, she played the American government and people like a fiddle to get support for a losing cause for years. The KMT (Guomingdang) only lasted as long as it did because of US support...

A revealing and fascinating look at the birth of Communist China, China/Taiwanese political tensions, and the woman who stood in the middle of it all.

Sweet illo! Welcome back Mr. Cressy...you were missed!

I second that emotion... your great work was missed as well!

Great illustration! So retro and yet so modern. The colour combination works really well and all the "religious" details brings in a good story

this is brilliantly splendid.

Thanks all. I'm glad to be back. I hope to be posting more art. I hope everyone had a Happy New Year and that we will all be prosperous in 2008.