new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: new york times book review, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 23 of 23

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: new york times book review in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

She's five now and tomorrow is her party. I went to the bookstore and I was appalled to realize that my obsession with middle grade fiction has left me unfamiliar with current picture books. I managed. I bought Mo Willems' The Thank You Book. We are big Mo Willems fans, she and I. And then, because she is my granddaughter and I don't have to care about protecting her from commercialism quite as much, I bought her an I Can Read book about one of her favorite TV shows.

|

| No, Mo, thank YOU!! |

You may be in a similar quandary as the frenzied gift-giving season arrives. All the FB posts and tweets are now counting down in days to You-Know-When.

Just in time!!! The New York Times Book Review has published the Best Illustrated Books of 2016 list. Hmm, it's not the best PICTURE books of the year, but, look, they all seem to be for children.

Here's the list. I am baffled to admit that I recognize only one title on this entire list.

Anyway, these may not be the best picture books but the artwork in each one is superb. If you have the luxury of giving the children in your life books they want to read AND books you want them to experience, well, do it!

Isn't Charles McGrath a right voice in our time?

(Wait. Did that sound critical?)

This week the

New York Times Book Review asked Charles McGrath and Adam Kirsch the question:

Is Everyone Qualified to Be a Critic? It's a question I often ask myself. A question I've been asking myself for the past 20 years, in fact—throughout my reviews of many hundreds of books for print and online publications, my jottings on behalf of the competitions I've judged, and my meanderings on this blog.

What makes me qualified? Am I qualified? And do I do each book—whether or not I like it—justice?

I do know this: If my mind is dull, if I am distracted, if I feel rushed, if I've grown just a tad weary of this trend or that affect, I won't review a book, not even on this blog, where I own the real estate. Writers (typically) work too hard to be summarily summarized, falsely cheered, unhelpfully glossed. Reviews should only be treated as art (as compared, say, to screed or self-glorification). It's important, as McGrath notes, that we reviewers keep reviewing ourselves.

His words:

It’s surprising how much contemporary critical writing is a chore to get through, not just on blogs and in Amazon reviews but even in the printed paragraphs appearing below some prominent bylines, where you find too often the same clichés, the same tired vocabulary, the same humorless, joyless tone. How is it, you wonder, that people so alert to the flaws of others can be so tone deaf when it comes to their own prose? The answer may be the pressure of too many deadlines, or the unwritten law that requires bloggers and tweeters to comment practically around the clock. Or it may be that the innately critical streak of ours too frequently has a blind spot: ourselves.

By:

Valerie,

on 5/12/2015

Blog:

Jump Into A Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

New York Times Book Review,

whale watching,

Parent's Choice,

Something To Do Book Review,

A Symphony of Whales,

A Symphony of Whales Book Review,

Peter Sylvada,

Steve Schuch,

The At-Home Summer Nature Camp eCurriculum,

whale songs,

Add a tag

Last week I put the below video on my personal Facebook page. I was completely awe inspired by the communication between these instrumentalist and the whales. So inspired I put on my Facebook that I’d like to have this very experience !!!

Fellow book-lover Mia Wenjen of PragmaticMom wrote on my Facebook wall that I just had to read, A Symphony of Whales. I went out and got it immediately. Oh how right she was. This book is simply a captivating.

“Inspired by a true story, in the winter of 1984-1985, nearly three thousand beluga whales were found trapped in the Senyavina Strait of Siberia, a narrow body of water crossing the Bering Strait from Alaska. With the bitter cold, the water was freezing rapidly. In places the sea ice was twelve feet thick. For seven weeks, the people of the Chukchi Peninsula and the crew of the icebreaker Moskva risked their lives to save those whales. Against all odds, they succeeded.” Steve Schuch

Woven into the story is a tale about a little girl named Galshka who has a special gift. What if you had the gift to hear the centuries old song of the Whales? Glashka has this gift but with great gifts comes great responsibility. Glashka has always been able to hear music in her head, and the “old ones” of the village tell her she hearing the voice of Narna, the whale. Narna has long been a friend to her people. Glashka uses her gift to find the trapped whales and then through the gift of song discovers the secret to saving them.

Author Steve Schuch, a musician, turns this story into a lyrical and imaginative telling of a real life event. Equally as stunning are artist Peter Sylvia’s exquisite oil paintings which capture the story in texture and light and transport us to the harsh and stark environment of Siberia. Sylvada captures the changing story through light, texture, and movement.

We’re so appreciative to our friend Mia for suggesting this book. How special it is to be inspired by something and then given the gift of further inspiration in a book. Big thank you to you Mia Wenjen.

On our bucket list is to see a whale up close and personal, not in captivity but out there in the deep blue sea.

Somethings To Do

Whale Song

From Journey North

Acoustics is a major area of study for whale researchers. The humpback whales’ song is probably the most complex in the animal kingdom. Researchers study their songs and use this information in many areas of marine research and technology.

The humpback song, which is made up of repeated themes, can last for up to 30 minutes and some humpbacks sing for hours at a time! Only the males sing and all male humpbacks in the same region sing the same song. The song itself changes over time, making it different from year to year. The songs generally occur during the breeding season, suggesting that they are related to breeding. But researchers are still asking why do male humpbacks sing?

Whale Hearing

In addition to singing, humpbacks also hear well. Sound is exceptionally important to marine mammals living in the ocean (a very noisy place). Hearing is a well-developed sense in all cetaceans, largely because of the sensitive reception of waterborne vibrations through bones in the head. Take a look at the size of a whale’s head compared to its entire skeleton. You will notice that the head comprises up to one third of the total body length. The whale ear is a tiny opening that closes underwater. The bone structure of the middle and inner ears is modified from that of terrestrial (land-based) mammals to accommodate hearing underwater.

Let’s Dissect the Song

Humpback whales produce moans, grunts, blasts and shrieks. Each part of their song is made up of sound waves. Some of these sound waves are high frequency. If you could see these sounds, they would look like tall, pointed mountains. Whales also emit low frequency sound waves. These waves are like hills that are wide spread apart. These sound waves can travel very far in water without losing energy. Researchers believe that some of these low frequency sounds can travel more than 10,000 miles in some levels of the ocean!

Sound frequencies are measured in units called Hertz. The range of frequencies that whales use are from 30 Hertz (Hz) to about 8,000 Hz, (8 kHZ). Humans can only hear part of the whales’ songs. We aren’t able to hear the lowest of the whale frequencies. Humans hear low frequency sounds starting at about 100 Hz.

Whale Songs Similar to Other Animals

Researchers have noted that whale songs sound very similar to the songs of hoofed animals, such as. Elk (bugleing), cattle (mooing), and have more than a passing resemblance to some of the elephant noises. One of the leading researchers into humpback whale sounds, Katy Payne, also studies elephant sounds and has found similarities between these two species.

Where are Sounds Produced?

The larynx was originally thought to be the site of sound production in cetaceans but experiments on live, phonating dolphins showed that the larynx does not move during vocalizations. Instead there are structures in the nasal system including the nasal plug and the elaborate nasal sac system which move when sound is produced, although the exact site of the sound generation is still debated. You can read more about this fascinating subject in book called BIOLOGY OF MARINE MAMMALS, by Reynolds and Rommel.

Try This!

You can find the sound files to do this experiment here.

Listen to the humpback songs. Can you tell which parts of the songs are the higher frequencies (short and high pitched) and which are the lower frequencies? How would you describe these songs in words? What do the songs remind you of? How are the three songs similar and how are they different?

A whale’s low frequency sounds can travel up to 10,000 miles. Take out your globe, and using the scale of miles on the key, explore how far this distance is. Imagine you are a whale; how far can you sing?

Listen To Music Inspired by the Whales

As we create a play list of whales and about whales we simply have to start with A Symphony of Whales author Steve Schuch who is also a violinist and composer. On his website he has this link which has him playing violin with the whales. It’s perfect to have playing while reading A Symphony of Whales.

Other additions to our playlist include:

- Songs of the Humpback Whales by Roger Payne

- Whales Alive by Paul Winter/Paul Halley

- Whale Music by David Rothenberg

- “And God Created Great Whales” by Alan Hovhaness

- The Whale by John Tavener

- Ocean by Kenny Larkin Flute Music with Humpback Whale Songs

More Inspirations

Author Steve Schuch was so inspired by this story that he created a piece of music called Whale Trilogy. Then came the book A Symphony of Whales. Here’s a great interview about his inspirations on this story and music incorporated into story.

Looking for a unique way to keep your kids busy this summer…and engaged with nature? The At-Home Summer Nature Camp eCurriculum is available for sale!

This 8-week eCurriculum is packed with ideas and inspiration to keep kids engaged and happy all summer long. It offers 8 kid-approved themes with outdoor activities, indoor projects, arts & crafts, recipes, field trip ideas, book & media suggestions, and more. The curriculum, now available for download, is a full-color PDF that can be read on a computer screen or tablet, or printed out. Designed for children ages 5-11, it is fun and easily-adaptable for all ages!

The At-Home Summer Nature Camp eGuide is packed with ideas & inspiration to keep your kids engaged all summer long. This unique eCurriculum is packed with ideas & inspiration from a group of creative “camp counselors.” Sign up, or get more details, HERE

The post A Symphony of Whales Book Review- A Lyrical Whale-of-a-Tale appeared first on Jump Into A Book.

Brian Turner's immaculate memoir,

My Life as a Foreign Country, is reviewed today in the

New York Times Book Review by Jen Percy.

The book itself is so well worth reading. (My thoughts about it are

here.)

But the review is also a glory, opening with this paragraph about the importance of the empathetic imagination in memoir. Empathy may be nearly impossible to teach. But it does differentiate the great memoirs from the merely articulate ones, the we stories from the me tales. It's what should matter most to the makers and readers of memoir.

Jen Percy speaks of all this with bright, crisp words. Her entire review can be found

here.

There’s a persistent idea in our culture that what we experience is “true,” while what we imagine is “untrue.” But without exploring the possibility of imagination in nonfiction, we leave out a fundamental part of the human experience — digressive wanderings, the chaotic interior self and, most important, our empathy. Empathy, after all, starts as an act of fiction. We must think ourselves into the lives of others.

Something to contemplate as I stand, 162 pages in, with an odd, new, perhaps creation. A novel I have to keep setting aside, a novel I dream with, wake up to, put aside again (real work forever intervening). A novel that makes me ask myself daily, as I lose my battle with time: Is all this private agony worth it? Should I succumb? Wouldn't it just be easier if.... ?

Writing, like life, can drive a person mad. The pages of literary history are stained with the blood of writers who dashed their brains out. They are soaked with the drink that promised temporary consolation — or are left entirely blank, when the writer despaired and gave up. To make a new thing out of no thing is excruciating, but any writer who seeks to cut corners ends as a plagiarist or a hack. Agonizing experiment is inescapable.

— Benjamin Moser, for the

New York Times Book Review Question:

Can Writers Still Make it New?

This weekend's

New York Times Book Review fills me with desire. I imagine a lake house. I imagine time. I imagine a week with nothing but books and a notebook into which I might record my favorite lines.

Alas.

That isn't here, or now. And so I find myself reading the first many chapters of the reviewed books instead, trying to narrow my choices for those days when I will have full reading time. In Joshua Wolf Shenk's

Powers of Two, reviewed by Sarah Lewis, I find this bit of loveliness. I am, to be honest, a lone wolf much of the time—searching my limited brain for a next idea, having the conversation mostly in private, taking the long solo walk to breathe more substance in.

But there have been moments, projects, abbreviated eras when I've found myself in the midst of a heady collaboration. Someone to talk to. Someone who makes the small idea bigger or clearer than it began.

Shenk captures the feeling of that here:

When the quickening comes. When the air between us feels less like a gap than a passage. When we don't know what to say because there is so much to say. Or, conversely, when we know just what to say because somehow, weirdly, all the billions of impulses around thought and language suddenly coalesce and find a direction home.

Sometimes you meet someone who could change your life. Sometimes you feel that possibility. The sense that, in the presence of this celestial body, you fall into a new orbit; that the ground beneath you is more like a trampoline; that you may be able—with this new person—to create things more beautiful and useful, more fantastic and more real, than you ever could before.

How does this happen? What conditions of circumstance and temperament foster creative connection? In other words: Where and how does it begin? And which combinations of people make it most likely?

In 2004, I led the PEN/Martha Albrand Award jury for First Nonfiction—a responsibility that filled my home with books both large and small, historical and personal. I read about presidents and war. I read about tattoos. I read about doctors under siege. I read about landscapes. I shared my thoughts with four other jury members and ultimately traveled to Lincoln Center in New York City to introduce our winner, Paul Elie, whose

The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage had won us all over. At the ceremony, I put our affection for his work this way:

Ingeniously conceived and elegantly crafted, Paul Elie’s The Life You Save May Be Your Own shines an amber light on four twentieth-century Catholic storytellers who dared to believe in the power of literature and in the ultimate integrity of readers. Choosing to focus on the lives and works of Thomas Merton, Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, and Dorothy Day, Elie deftly moves among his illustrious characters —reflecting on influences, unveiling connections, tying one to the other in often unexpected ways. Elie transitions between the personal and the political, the literary and the lived, with enviable ease. Most of all, he does supreme justice to his subjects with vivid, lithe, and never once pretentious prose.

I've been watching Elie's career unfold ever since—grateful for his continuing presence as a mold breaker and deep thinker. This weekend, Elie has a long essay in

The New York Times Book Review titled

"Has Fiction Lost Its Faith?" If you have time on this holiday weekend, take a careful look.

By:

Beth Kephart ,

on 11/30/2012

Blog:

Beth Kephart Books

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

YALSA,

Gotham,

New York Times Book Review,

Publishing Perspectives,

The Atlantic Wire,

Ed Nawotka,

Jen Doll,

A.A. Omer,

CMRLS Teen Scene,

Small Damages Printz Watch,

Add a tag

And so, in this week of breathtaking kindness, I want to thank some special people for throwing light my way.

Ed Nawotka, for inviting me to give the keynote address at the Publishing Perspectives conference and for subsequently

running the talk today on the Publishing Perspectives site. To all of you have retweeted the talk, thank you.

Jen Doll, for including

Small Damages as one of the top 25 book covers here, on the

Atlantic Wire, and for making this the year to remember with

her New York Times Book Review thoughts about the book last July.

The YALSA folks for naming

Small Damages to the BFYA list.

CMRLS Teen Scene for putting

Small Damages on the

Printz watch.

A.A. Omer, for giving

Small Damages

this glorious five-star review.My friends, old and new, for being there. My agent, Amy Rennert, for her enthusiasm. And while this has absolutely nothing to do with

Small Damages, a huge thanks to the Gotham team for being so wholly supportive of

Handling the Truth, a book due out next August. I will do everything in my power to earn your faith in me.

My father, for buying a copy of

Small Damages, and making a go of reading it, even though it's not exactly this history lover's kind of book.

I have been in the book business a very long time. I will hold onto these gifts, in memory, for the rest of my life.

Albert Vigoleis Thelen's The Island of Second Sight received a glowing review in last weekend's New York Times Sunday Book Review. Today, translator Donald White joins us on the blog for an interview to discuss the first English edition what Thomas Mann famously called "one of the greatest books of the twentieth century."

How did you first come

across A.V. Thelen’s Die Insel des zweiten

This leads to the suggestion that story’s role is “intensely moralistic.” Stories serve the biological function of encouraging pro-social behavior. Across cultures, stories instruct a version of the following: If we are honest and play by the social rules, we reap the rewards of the protagonist; if we break the rules, we earn the punishment accorded to the bad guy. The theory is that this urge to produce and consume moralistic stories is hard-wired into us, and this helps bind society together. It’s a group-level adaptation. As such, stories are as important as genes. They’re not time wasters; they’re evolutionary innovations.

I have mentioned her previously here—ageless, gorgeous, a knock-out, smart, funny, perpetually a Kindle in her hand (she not only reads great books, she once owned a bookstore). We dance Zumba together, when I'm very lucky. She shows up all blonde and coiffed, I show up all frizzy haired and old eyelinered, and we do it up. She goes crazy for the Charleston. I'll give her that if she'll dance my tango.

Her name is Joy, and I flat out love her. I refuse to believe the things she tells me about how old she is. Not even close. Not for a minute.

Today I barely got to Zumba on time. I didn't think, in fact, that I'd make it, but I finished a client call with seconds to spare and made a mad dash for the gym. Looking back, imagining myself a no-shower for Zumba, imagining that client call gone just five minutes longer, I feel bereft. For I would never have seen Joy in her joyful frenzy, plastering Xeroxes of

The New York Times review of Small Damages all over the club town. When she saw me she ran for a hug, Xeroxes in hand, then orchestrated a round of applause among the gathered dancers, then went about telling all the ladies I Zumba with that I'm an author in disguise.

I watched her with awe. I listened to what she said. I caught a glimpse of the mess of me in the mirror and tried to reconcile my image of myself with the beauty of her. Not possible. She rushed by as the music was getting started and said,

"I'm as proud as if I were your own mother."

Genuine happiness is genuine gold.

My friends: I'll be at the

BEA on Tuesday, June 5, 2012, working for

Publishing Perspectives, the fabulous book news pub for which I have written about Pamela Paul (

New York Times Book Review children's book editor), Jennifer Brown (

Shelf Awareness children's book editor), Lauren Wein (Harcourt Houghton Mifflin editor), Alane Mason (WW Norton editor, not to mention my first editor), and others. I'll be getting the inside scoop on some important stories. But I'll also be looking for you.

If you'll be there, let me know?

"A short story is by definition an odder, more eccentric creature than a novel: a trailer, a fling, a warm-up act, a bouillon cube, a championship game in one inning. Irresolution and ambiguity become it; it’s a first date rather than a marriage. When is it mightier than the novel? When its elisions speak as loudly as its lines." — Stacy Schiff in the

New York Times Book Review review of Nathan Englander's story collection,

What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank.

Ever since

Dana Spiotta reviewed Shards in the

The New York Times Book Review a few weeks ago, I have been eager to get a copy for myself. Consider, here, what

Dana says:

The novel is constructed of fragments — shards — seemingly written by its main character, Ismet Prcic. Ismet grows up in Tuzla and manages to flee shortly before his induction into the “meat grinder” of the Bosnian infantry. He has survived and made his way to America, but is fractured by what he left behind. The novel comprises mostly segments from his therapist- ordered memoir (or memoirs) and excerpts from his diary. These shards employ several narrative strategies. There are asterisked footnotes, italicized interruptions and self-reflexive comments about unreliability. There are first-, second- and third-person narrations, sometimes switching back and forth within a paragraph. This is a novel about struggling to find form for a chaotic experience. It pushes against convention, logic, chronology. But its disruptions are necessary. How do you write about war and the complications of memory? How do you write about dislocation, profound loneliness, terror? How does a human persevere?

Truth is, I'd been eager to read Ismet Prcic's debut novel ever since I sat in the office of

Lauren Wein, the book's editor, and listened to her read aloud from the opening passage. The book had only recently been released as advance reading copies and, judging from the number of brilliantly hued sticky notes attached to many of the pages, Lauren was still giving this book her extraordinary editorial attentions. I loved the sound of what she had read to me. I could not wait to read more. And then, caught up in the crazy swirl of my own life, I did wait, not buying the book until just recently.

I am only into the early pages at this point. I am not, as I thought I might be, intimidated by the hybrid of forms, techniques, approaches. The word "propulsive" has been attached to this book, and that it is, but the book is remarkably resonant, too, often funny, surprisingly accessible, despite all that is original and new. Here is an early-in example:

I love a girl, Melissa. Her hair oozes like honey. It's orange in the sun. She loves me, mati. She's American. She goes to church. She wears a cross right where her freckles disappear into her cleavage. She volunteers. She takes forty minutes to scramble eggs over really low heat, but when they're done they explode in your mouth like fireworks, bursts of fatty yolk and coarse salt and cracked pepper and sharp melted cheddar and something called thyme. She's sharp. She drives like a lunatic. She's capable of both warmth and coldness, and just hanging around her to see what it will be that day is worth it.

and why they matter in works of art. I was thinking, as I read, that the

New York Times Book Review should hire Amy as a weekly essayist. She is just that good. I was thinking, too, about how lucky I am to count Amy as a faithful reader and so entirely generous friend.

Thank you, Amy, for

these words. Thank you, indeed, for everything.

Back on May 21st I made

the audacious announcement that I had just read the book of the year, which is to say that I'd just finished

Stone Arabia by Dana Spiotta. Audacious because I'd already been singing some pretty sweet blog tunes about many a fine read this year. Audacious because I've not yet read the forthcoming Ondaatje or Otsuka, or, indeed, the entire fall line-up. Audacious because, well, who am I, anyway?

But if one must stand on a cliff, why not stand on

Stone Arabia? This brother-sister story is original, foundational, heartbreakingly sad and heartbreakingly funny, and I don't need to repeat myself, because I called it back in May.

But, hey. It's nice to have some company in that assessment, and so I give you here Kate Christensen's words, published today, on behalf of the

New York Times Book Review. Christensen calls

Stone Arabia "a work of visceral honesty and real beauty." See

what else she has to say.

And if you want to know what big question lies at the heart of this novel, listen to Dana herself,

live from YouTube.

Susan Hill's latest Simon Serralier mystery, SHADOWS IN THE STREET, went on sale in the U.S. last Thursday, and we're thrilled to see that others are loving her wonderful work as much as we are. Did you miss her review in the New York Times? See below for the full review and some other praise that has been rolling in for SHADOWS IN THE STREET.

"As every Trollope reader knows, English cathedral towns can be hotbeds of viciousness and vice. And so it is in Lafferton, where Susan Hill sets her thoughtful mysteries. As if it weren’t bad enough that flesh traffickers from Eastern Europe have been deploying a small army of underage prostitutes on the edge of town in THE SHADOWS IN THE STREET (Overlook, $24.95), the unpopular new dean of the cathedral, a “happy-clappy” Anglican evangelical, and his overbearing wife (“the Mrs. Proudie of St. Michael’s”) are hell-bent on saving the souls of these “Magdalenes,” whether they like it or not. Simon Serrailler, the brooding detective hero, doesn’t appear on the scene until a serial killer begins picking off some of the local working girls who’ve been displaced by the foreign competition. But his absence allows Hill to direct her elegant prose to other characters, especially Serrailler’s widowed sister, observed in depth as she struggles to live with her grief." -- The New York Times

“This is the fifth of Hill's exceptional series (after The Various Haunts of Men, The Pure in Heart, The Risk of Darkness, and The Vows of Silence). Her characters continue to be intelligent and engaging, and the perfect balance of drama, atmosphere, and suspense holds the reader to the very last page. Highly recommended for fans of thoughtful British mysteries, especially those written by P.D. James, Martha Grimes, and Tana French.” -- Library Journal (starred review)

“It is really the characters that are so strong in these novels and even the minor characters are brought to life... As usual, I thoroughly enjoyed this book.” -- Canadian Bookworm Blog

“Hill continues to engage us with fresh characters and intriguing story lines.” -- MostlyFiction.com

"Right from its rain drenched opening lines, Shadows draws the reader into its bleak landscape. Hill is a master at creating atmosphere – the autumn chill hovering over the town seeps right into the story, and tightens its hold on the reader as the plot hurtles towards its climax… strong writing, taut pace and finely etched characters” -- BookPleasures.com

I've now read at least a half dozen reviews of Elizabeth Gilbert's new mega-memoir, Committed, including the Curtis Sittenfeld version that appears on this weekend's cover of the New York Times Book Review. I've watched her talk. I've read the interviews. And it occurs to me that, were I to read this book, I probably wouldn't know much more about Gilbert's travails or voice or happy ending than I already do. There's a remarkable sameness in the press, in the reviews. There is little variation in how Gilbert's story is summarized (she never wanted to get remarried, but she was forced to), in which telling anecdotes are brought forward (her grandmother's marriage story, the marriage stories of Hmong grandmothers), in how Gilbert herself is portrayed (chatty, entertaining, self-knowing bordering on self-absorbed). Were Gilbert running for office no one would be left confused about the party line. There is no murk in the margins. No room, it seems, for the unexpected retelling or interpretation.

I've now read at least a half dozen reviews of Elizabeth Gilbert's new mega-memoir, Committed, including the Curtis Sittenfeld version that appears on this weekend's cover of the New York Times Book Review. I've watched her talk. I've read the interviews. And it occurs to me that, were I to read this book, I probably wouldn't know much more about Gilbert's travails or voice or happy ending than I already do. There's a remarkable sameness in the press, in the reviews. There is little variation in how Gilbert's story is summarized (she never wanted to get remarried, but she was forced to), in which telling anecdotes are brought forward (her grandmother's marriage story, the marriage stories of Hmong grandmothers), in how Gilbert herself is portrayed (chatty, entertaining, self-knowing bordering on self-absorbed). Were Gilbert running for office no one would be left confused about the party line. There is no murk in the margins. No room, it seems, for the unexpected retelling or interpretation.

A dozen years ago, when I was just starting out in this book life, I was encouraged to think about the "one line or two" that summarized my books. The hook that would broadcast their intentions, content, style. I failed for the first book. I failed for the next. I pretty much gave up by the time I'd written a book called Flow, the autobiography of a river. Say what? most editors said, after listening to me talk in a circle about it. Is it history? Is it poetry? Is it fiction? Even my novels have refused to fit inside the lines of what might be easily parlayed; I end up writing most summaries or jacket flap copy with a sense of familiar defeatism. I need more sentences than there's room to print. Again and again, I come up hookless.

I should probably work on that, but frankly, I don't know how to. That's not a boast; it's a confession. It's the reason why I need to write most of my books all the way through before I can try to sell them, for I never fully know, until I'm done too many drafts to count, what my books are all about. Even then, I need some room to explain them. Even then, they will be summarized, reviewed, and interpreted in ways that I often don't see coming.

"You Never Know What You'll Find in a Book," Henry Alford's back-page essay in this weekend's New York Times Book Review, has me remembering this morning; those essays often do. Alford's piece is a roam—across the slice of bacon Reynolds Price once found tucked inside a library book, through the books-as-banks memories of the now-sober Sherman Alexie, and past book-stashed Q tips, notes to self, faux history, cash, even a baby's tooth (I understand that one, and then again I don't).

"You Never Know What You'll Find in a Book," Henry Alford's back-page essay in this weekend's New York Times Book Review, has me remembering this morning; those essays often do. Alford's piece is a roam—across the slice of bacon Reynolds Price once found tucked inside a library book, through the books-as-banks memories of the now-sober Sherman Alexie, and past book-stashed Q tips, notes to self, faux history, cash, even a baby's tooth (I understand that one, and then again I don't).

The essay took me back to the years I spent visiting an old book barn 30 minutes down the road. I went in search of anything Spanish Civil War esque, anything that might tell me more about a novel I kept endlessly rewriting. I'd come home with boxes of things, books inside which had been stashed recipes, memos, polaroids, objets d'art kept safe—for whom? I wondered, for what?

Later, I began to write a novel about the writer who had gone searching—not just for that war, but for herself. I never published that book either, but this morning, looking back over those pages, I found that writer who is still searching, who still loves the holy ground of books:

She was not afraid to stow the seashells in her pockets. Not afraid to chase the moon into the mountains. Not afraid to spend almost the whole of every Sunday in the book barn down the road, which she had fallen in love with for its dozens of stairs, its risers that went up and down, Escher-ized. She had loved the way the books were shelved in old peach crates and how the overturned crates were also chairs. How thick the floors were with splinters. How there was the smell of fruit mixed with the smell of history, and no sound except the sound of turning pages, the sound of an occasional bibliophile’s shoes or the call of Mr. Shipley, “Finding everything you need?” She had loved the room she had thought of as her own: the Spanish room. She had loved the Andrew Wyeth painting on the wall below, and the rocking chair and the old church pew and the gigantic books nobody purchased. She’d needed no one but herself at the book barn. Nothing but the stairs and the gardens of color she could see through the open windows —the reds and greens, the occasional starched yellow.

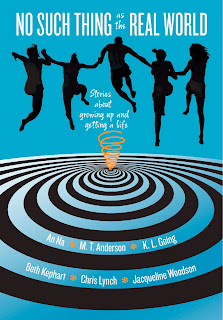

Before Jill Santopolo was officially my editor, she was my editor—calling one day to ask if I might write a story for a planned new HarperTeen anthology. The story, as I understood it, was to focus on a chosen turning point—on a moment of emergence, clarity, vision.

Before Jill Santopolo was officially my editor, she was my editor—calling one day to ask if I might write a story for a planned new HarperTeen anthology. The story, as I understood it, was to focus on a chosen turning point—on a moment of emergence, clarity, vision.

I'd written short stories for years before I'd ever written books; I've always celebrated the form's power. I'm a fan of the deeply distilled, the evocative, the provoked. I favor poetry over plot, emotion over explanation, wisdom over information; the short story seems to favor such things too, or can. Read the exquisite Steven Millhauser piece in this Sunday's NYTBR. Consider his words here:

The short story concentrates on its grain of sand, in the fierce belief that there — right there, in the palm of its hand — lies the universe. It seeks to know that grain of sand the way a lover seeks to know the face of the beloved. It looks for the moment when the grain of sand reveals its true nature. In that moment of mystic expansion, when the macrocosmic flower bursts from the microcosmic seed, the short story feels its power. It becomes bigger than itself. It becomes bigger than the novel. It becomes as big as the universe. Therein lies the immodesty of the short story, its secret aggression. Its method is revelation. Its littleness is the agency of its power.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/05/books/review/Millhauser-t.html?ref=books

The point is, I said yes. I said yes and loved every moment of immersion in a piece I finally called, "The Longest Distance Between Two Places." Written early last year, it confronts teen suicide and its aftermath—and a decision to live on.

I saw the cover of the anthology today, and I'm really proud to be part of this project. I'm especially touched to see An Na's name here, for seven years ago, while chairing the National Book Awards jury for Young People's Literature, I read her gorgeous "A Step from Heaven;" as a team we nominated it as a top five title. I remember many things from that evening of award giving (Jonathan Franzen's talk, sitting beside Terry Tempest Williams on that stage, my son out in the audience, holding court, and, later, Steve Martin entertaining my child). But I especially remember An Na's graciousness in the moments after the winners had been announced. It made me even prouder that I'd pushed for her inclusion in the top five.

I can't wait to read this book.

In the Sunday NYTBR essay, Dorothy Gallagher looks back on the lessons passed on by one Helene Pleasants, a copy editor the author met while a junior editor at Redbook:

In the Sunday NYTBR essay, Dorothy Gallagher looks back on the lessons passed on by one Helene Pleasants, a copy editor the author met while a junior editor at Redbook:

Helene had no literary theories — she had literary values. She valued clarity and transparency. She had nothing against style, if it didn’t distract from the material. Her blue pencil struck at redundancy, at confusion, at authorial vanity, at the wrong and the false word, at the unearned conclusion. She loved good writing, therefore she loved the reader: good writing did not cause the reader to stumble over meaning. By the time Helene was finished with me seven years later, I knew how to read a sentence and how to fix one. I knew what a sentence was supposed to do. I began to write my own sentences; needless to say, the responsibility for them is my own.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/28/books/review/Gallagher2-t.html?_r=1&ref=books&oref=slogin

I wondered about the essay's frigorific opening lines, "My copy editor died. No need to be upset on my account. I hadn't seen Helene Pleasants for at least 10 years before her death; and even those closest to her would agree that her death was timely." I wondered, too, about its gelid last: "And I've changed my mind: it is a pity that Helene died. As long as she lived, I could still think of myself as a young writer."

But the in-between of Gallagher's essay brought poignantly to mind the copy editors who have done their level best to keep me in grammatical line. I moved quite a bit as a child—Wilmington to Alberta to Wilmington to Boston to Wilmington and finally to a suburb of Philadelphia—and in that zagging journey I lost two academic things: continuity with a foreign language (don't test my French) and an ability to stay on course with any grammar lessons. I was perpetually relearning what I already knew, or I was skipping entire chapters of Strunk & White.

Given the Swiss Cheese quality of my brain, this was not good.

So that I have had to rely on copy editors since (and pray for my poor blog readers, who daily encounter the unfiltered, uncorrected Beth), and though I've run the gamut of experiences, I've grown rather fond of one who shall remain unnamed, one I've never met. She stalks my every comma, circles my overblown "just," writes thin-penciled comments in the margins that remind me that it'll always be love of language first for her, struggling writer distant second. What were you thinking? her comments fairly shout. What business have you writing in the first place? Have you taken a good look at yourself?

I read her notes in the privacy of my own house. I turn magnificent shades of red. I tremble. And then I'm severely grateful for her, grateful that she cares so much.

I pay attention. I apply my learnings. I do try to get it right. I fantasize, even, about receiving a Fed Ex with a single note inside: Your manuscript required no changes, it might say. It's gone directly to print.

By: John Mark Boling,

on 9/17/2008

Blog:

The Winged Elephant

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Wodehouse,

p.g. wodehouse,

Paper cuts,

new york times book review,

Galleycat,

Uncle Fred in the Springtime,

Leave it to Psmith,

bonfiglioli,

The Code of the Woosters,

Add a tag

On Monday, Paper Cuts, the blog of the New York Times Book Review, attempted to determine the funniest novel ever. At the top of their list were not one, but two Wodehouse classics: THE CODE OF THE WOOSTERS and LEAVE IT TO PSMITH.

On Monday, Paper Cuts, the blog of the New York Times Book Review, attempted to determine the funniest novel ever. At the top of their list were not one, but two Wodehouse classics: THE CODE OF THE WOOSTERS and LEAVE IT TO PSMITH.

Galleycat, however, disagreed:

"For example, where P.G. Wodehouse is concerned, The Code of the Woosters and Leave it to Psmith may be funny, but they are not UNCLE FRED IN THE SPRINGTIME—which is, in fact, the funniest English-language novel ever published, no matter what any of you care to say different. (Even the ones who point out that the Times left out the works of Kyril Bonfiglioli!)"

So, while there may be some debate as to the exact novel, Paper Cuts and Galleycat agree: If you want to laugh, Wodehouse is the man for the job.

What's your favorite Wodehouse novel? Post your defense below for a chance to win the next two books in our Collector's Wodehouse series: PSMITH, JOURNALIST and NOTHING SERIOUS. The answer that makes us laugh the hardest wins!

By: Rebecca,

on 7/31/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Oxford,

computer,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

quoting,

oed,

dictionary,

ammon shea,

journalists,

NYTBR,

architect,

New York Times Book Review,

verb,

“architect”,

trade,

webster’s,

reviewer,

slander,

Add a tag

Ammon Shea  recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reflects on an article he saw in The New York Times Book Review.

recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon reflects on an article he saw in The New York Times Book Review.

Last Sunday, in the New York Times, I read a book reviewer taking an author to task for her word use. The reviewer stated that “the last time I checked the American Heritage Dictionary, in spite of how computer trade journalists might choose to use the word, “architect” was not recognized as a verb”.

First, putting aside the obvious slander against computer trade journalists (who themselves would likely not claim to be arbiters of what is recognized in language), are there perhaps some other sources that might recognize “architect” as a verb? Surprisingly enough, there are - both the Oxford English Dictionary and Merriam-Webster’s Third International list “architect” as a verb.

The OED provides citations from as far back as 1813, quoting a letter from Keats, in which he writes “This was architected thus By the great Oceanus.” The OED also specifies that the word, in addition to being used as a verb, is used in a figurative and transferred sense. Perhaps those computer trade journalists were engaging their poetic whimsy and quoting this early nineteenth century versifier.

Webster’s Third does not provide dates for their citation (“the book is not well architected”), but it is from the Times Literary Supplement, and so perhaps the aforementioned computer trade journalists were simply imitating the writing style of some other, more lofty and intellectual publication.

It is always a little bit risky to make a claim that something is not a word, or not used thusly, or has never been a certain part of speech. First, there is simply the possibility that you are wrong. But also, if you spend enough time looking through dictionaries you are just as likely as not to find one or two which contradict whatever position you’ve so boldly staked out. Of course, the flip side of this is that if someone states that you are wrong on the meaning of a word, you can usually find some source that will back up your position.

I’ll bet that the hordes of angry computer trade journalists who read that comment are right now sharpening their pens and rifling through their dictionaries, searching about for the perfect vicious rejoinder to refute this review.

ShareThis

Someone just linked me to this last night. I read it but need more time to really digest it. Your additional recommendation makes me eager to do so!

I just read it this morning. I thought it was insightful and spot-on. He raises some great questions.

Great link. One of the things I've found turns people off in reviews is mentioning that a book has an exploration of faith and/or religion, which is sad. It's such a big part of many people's lives, why would we cut it out of our fiction?

Thank you for the link. I'm off to have a look now.