By Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

It has become a holiday tradition on the OUPblog to ask our favorite people about their favourite books.  This year we asked authors to participate (OUP authors and non-OUP authors). For the next two weeks we will be posting their responses which reflect a wide variety of tastes and interests, in fiction, non-fiction and children’s books. Check back daily for new books to add to your 2010 reading lists. If that isn’t enough to keep you busy next year check out all the great books we have discovered during past holiday seasons: 2006, 2007, 2008 (US), and 2008 (UK).

This year we asked authors to participate (OUP authors and non-OUP authors). For the next two weeks we will be posting their responses which reflect a wide variety of tastes and interests, in fiction, non-fiction and children’s books. Check back daily for new books to add to your 2010 reading lists. If that isn’t enough to keep you busy next year check out all the great books we have discovered during past holiday seasons: 2006, 2007, 2008 (US), and 2008 (UK).

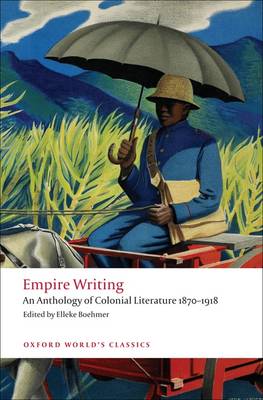

Elleke Boehmer is Professor of World Literature at Wolfson College, Oxford and is internationally known for her research in postcolonial writing and theory, and the literature of empire. She has written or edited five books for OUP: Scouting for Boys, Empire Writing, Nelson Mandela: A Very Short Introduction, Empire, the National, and the Postcolonial, 1890-1920, and Colonial and Postcolonial Literature.

My favourite books keep changing their line-up, with new number ones jostling for attention in phases, depending on shifting interests and moods.

As far as my favourite children’s book is concerned however I will always come back to LM Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, 101 this year, which I must first have read aged about 11 and like so many bookish provincial girls the world over related to at once. As the tale of the parentless redhead who grows up with elderly Matthew and Marilla in Canada’s smallest province, Prince Edward Island, where the soil is as red as her hair, Anne is the ultimate ugly duckling girl’s story. What young teenage reader of that era, I wonder, would not have identified with harum-scarum Anne in her quest for family, friendship, poetry and love, in roughly that order, and who succeeds in that quest without losing her charm and her propensity for falling into ‘scrapes’? I certainly identified, with a vengeance, to the extent that, aged 17, I railroaded and cycled all the way from Toronto to PEI in order to see Anne’s island for myself.

My favourite book for adults at the present time is another story about a child, this time a boy, JM Coetzee’s Boyhood, the first in his ‘self-cannibalizing’ trilogy (to quote Zadie Smith) Scenes from Provincial Life. Boyhood presents as a fiction, in memoir form, as some of the scenes appear to emerg

“Jane, it’s the wreck of a fine man that you see before you,” he said hollowly.

“Dad . . . what is the matter?”

“Matter, says she, with not a quiver in her voice. You don’t know…I hope you never will know… what it is like to look casually out of a kitchen window, where you are discussing the shamefully low price of eggs with Mrs Davy Gardiner, and see your daughter…your only daughter …stepping high, wide and handsome through the landscape with a lion.”

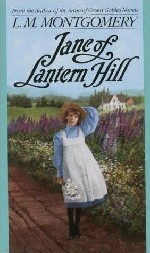

Remember when you first realized the author of Anne of Green Gables had written a ton of other books besides the ones about Anne?

Maybe you found the Emily series next. Perhaps at times you harbored the heretical thought that Emily of New Moon was even better than Anne of Green Gables. You always changed your mind and gave the crown back to Anne because, well, there was something a wee bit prickly about Emily; she was terribly interesting, and you certainly admired her fire and her talent, but she wasn’t exactly bosom friend material. She seemed…hmm…a little cliqueish, perhaps, in her way; she wasn’t always out looking for kindred spirits like Anne. Indeed, she had enough difficulty managing the friends she already had. Emily didn’t need you: she had Ilse and Teddy and her art. Not to mention all that nonsense with Dean Priest, who, let’s be honest, kind of creeped you out from the start. And you knew it would be no use trying to warn Emily; that would just have put her back up.

Still, you were so glad you met her.

Perhaps it ended there, with Emily and Anne. Or maybe, just maybe, you were lucky enough to discover the others, the Pat books, the Story Girl duo, the one-offs, the story collections…and if you were very lucky indeed, maybe one day you met Jane of Lantern Hill.

Oh, Jane, that practical, capable, matter-of-fact miss. At first it is easy to underestimate her: she seems to lack the spunk and impulsiveness that make Anne and Emily so entertaining. Anne has barely arrived at Green Gables when she’s blowing up at Mrs. Lynde; and Emily, my goodness, the way she bursts out from under the table quivering with rage at all the aunts and uncles criticizing her father after his funeral: could you help but applaud? But Jane seems so quiet, so put-upon, so cowed by her horrible grandmother. Sure, you can see she’s seething inside, but isn’t that the point? Anne and Emily don’t seethe: they erupt. You keep waiting for Jane to erupt, practically begging her to.

Oh, Jane, that practical, capable, matter-of-fact miss. At first it is easy to underestimate her: she seems to lack the spunk and impulsiveness that make Anne and Emily so entertaining. Anne has barely arrived at Green Gables when she’s blowing up at Mrs. Lynde; and Emily, my goodness, the way she bursts out from under the table quivering with rage at all the aunts and uncles criticizing her father after his funeral: could you help but applaud? But Jane seems so quiet, so put-upon, so cowed by her horrible grandmother. Sure, you can see she’s seething inside, but isn’t that the point? Anne and Emily don’t seethe: they erupt. You keep waiting for Jane to erupt, practically begging her to.

But Jane’s not the erupting type, and what makes her story so satisfying is that she isn’t a prodigy—not of feistiness, nor imagination, nor talent. She’s an average Jane: which means that if Jane can fix up the mess that is her life, anyone can.

When we meet Jane, she and her mother are living with the aforementioned horrible grandmother. At first Jane’s mom seems like a Mrs. Lennox type a la Secret Garden, and you’re half-expecting typhoid to kill her off. But no, there she is fluttering in for a goodnight kiss on her way to a party, and the tear in her eye belies her lighthearted manner. Mummy’s in pain, Jane knows, and she needn’t look farther than Grandmother’s scowl to see why.

Jane’s mother’s family is Old Money, though the neighborhood is decaying around the family mansion. Jane’s cousins got all the talent, brains, and looks, it seems (Jane’s relatives are somewhat hard to distinguish from the obnoxious family of another meek-but-seething Montgomery heroine, Valancy Stirling of The Blue Castle)—but anyone with sense can see that cousin Phyllis and the rest of them are snooty, unimaginative bores, and Jane’s the only one with any salt to her. She’s warmhearted enough to care about the plight of the orphan next door, and she’s alert enough to be interested in the bustle of the servants, particularly the kitchen staff. Mostly Jane longs for something to do, something or someone to take care of. This desire to be active, not passive, is at the heart of Jane’s story. As a small child she entertains herself by imagining “moon sprees,” flights of fancy involving a host of imaginary chums who help her polish the dull and tarnished moon into a gleaming silver orb. This rather quirky fantasy (the quirkiest thing about Jane, really) is an expression of her longing for warm camaraderie, a happy family circle, a cozy hearth, and some soul-satisfying work to do. In her mind all these things are wrapped up together: Jane longs for the warmth and liveliness of a loving family, and she wants to be one of the people involved in the domestic bustle that creates a cozy and welcoming home. Her grandmother’s mansion is as cold and sterile as the dark side of the moon—the place to which her imaginary creatures must go when they are sulky or lazy, and from which they return “chilled to the bone,” eager to warm themselves up with extra-vigorous polishing.

Until age ten, these imaginary moon sprees are Jane’s only outlet for the urge to do, to work, to transform what is cold and lifeless to something warm and bright. Her tyrannical, hypercritical grandmother makes all decisions having to do with Jane and her mother. The mother is like a butterfly trapped in a cage, miserable, helpless. Jane’s father is absent: she has been led to believe he is dead. Then one day a rather nasty schoolmate discloses a disgraceful secret: Jane’s father isn’t dead; he’s alive and well and living on Prince Edward Island. Her mother, claims nasty Agnes, left him when Jane was three years old.

“Aunt Dora said she would likely have divorced him, only divorces are awful hard to get in Canada, and anyhow all the Kennedys think divorce is a dreadful thing.”

Jane is appalled by this knowledge, but it galvanizes rather than paralyzes her. The passive child becomes a girl of action. Her first action is to demand truth—she marches into a tea party and asks the question point blank: “Is my father alive?” Her mother answers simply “yes,” and this truth sets Jane—gradually and eventually, and not without some pain—free.

Another year passes before the event that will change Jane’s life forever: and here again transformation is possible only when someone who has been passive takes some positive action. Jane’s father writes a letter. He wants Jane to spend a month with him the following summer. Jane, despite the waves of fury emanating from her powerful grandmother and the fear and sorrow pouring out of her mother, chooses to go.

The magic of their reunion is enhanced by the glories of a Prince Edward Island June, but we sense that Jane, given the opportunity to roll up her sleeves and get to work, could bring a sparkle and warmth to any place. Her connection with her long-lost father is immediate: he is a kindred spirit from the first moment of meeting. Of course it helps that she recognizes him from a picture she clipped from a newspaper, a photo of a respected writer whose essays were above young Jane’s head but whose face charmed her for reasons she could not fathom at the time.

“Here’s your baby,” said Aunt Irene. “Isn’t she a little daughter to be proud of, ‘Drew? A bit too tall for her age perhaps, but . . .”

“A russet-haired jade,” said a voice.

Only four words . . . but they changed life for Jane. Perhaps it was the voice more than the words . . . a voice that made everything seem like a wonderful secret just you two shared. Jane came to life at last and looked up.

Peaked eyebrows . . . thick reddish-brown hair springing back from his forehead . . . a mouth tucked in at the corners . . . square cleft chin . . . stern hazel eyes with jolly looking wrinkles around them. The face was as familiar to her as her own.

“Kenneth Howard,” gasped Jane. She took a quite unconscious step towards him.

The next moment she was lifted in his arms and kissed. She kissed him back. She had no sense of strangerhood. She felt at once the call of that mysterious kinship of soul which has nothing to do with the relationships of flesh and blood. In that one moment Jane forgot that she had ever hated her father. She liked him . . . she liked everything about him from the nice tobaccoey smell of his heather-mixture tweed suit to the firm grip of his arms around her. She wanted to cry but that was out of the question so she laughed instead . . . rather wildly, perhaps, for Aunt Irene said tolerantly, “Poor child, no wonder she is a little hysterical.”

Father set Jane down and looked at her. All the sternness of his eyes had crinkled into laughter.

“Are you hysterical, my Jane?” he said gravely.

How she loved to be called “my Jane” like that!

“No, father,” she said with equal gravity. She never spoke of him or thought of him as “he” again.

Long estrangement notwithstanding, Jane’s dad is practically perfect—except for his blind spot where his officious, patronizing, meddling older sister, the poisonously sweet Aunt Irene, is concerned. Jane, a shrewd lass, puts two and two together and begins to see that her parents’ marriage was sabotaged from the get-go: with Aunt Irene on one side and Grandmother on the other, the young couple hardly stood a chance. Both Grandmother and Irene exercise a vast amount of power, each in her way, one ruling with an iron fist and the other insinuating herself between the newlyweds with damaging words like the dangerous, delicate tendrils of an edifice-crumbling vine.

Slowly Jane pieces together the mystery of what shattered her parents’ marriage. One of the most satsifying things about the book is Jane’s fairmindedness, her calm, unflinching gaze. She sees her parents’ mistakes and flaws—and adores them anyway. She will brook no criticism of either one from Grandmother, Aunt Irene, nor anyone else.

Her gradual understanding of the forces that separated her parents takes place against a backdrop of domestic zeal, for in reuniting with her father, Jane finds, at last, Something to Do, a vocation she can throw herself into with energy: keeping house. The quest for just the right home is one of the best parts of the book: Jane holds fast to a certainty that she’ll know the right house by its “lashings of magic,” and after Jane and Dad have ruled out a number of adequate but unmagical houses, they hear about a little place that is vintage L. M. Montgomery.

“The Jimmy Johns have one, I hear,” said the man. “Over at Lantern Hill. The house their Aunt Matilda Jollie lived in. There’s some of her furniture in it, too, I hear…It’s two miles to Lantern Hill and you go by Queen’s Shore.”

The Jimmy Johns and a Lantern Hill and an Aunt Matilda Jollie! Jane’s thumbs pricked. Magic was in the offing.

Jane saw the house first . . . at least she saw the upstairs window in its gable end winking at her over the top of a hill. But they had to drive around the hill and up a winding lane between two dikes, with little ferns growing out of the stones and young spruces starting up along them at intervals.

And then, right before them, was the house . . . their house!

“Dear, don’t let your eyes pop quite out of your head,” warned dad.

It squatted right against a little steep hill whose toes were lost in bracken. It was small . . . you could have put half a dozen of it inside 60 Gay. It had a garden, with a stone dike at the lower end of it to keep it from sliding down the hill, a paling and a gate, with two tall white birches leaning over it, and a flat-stone walk up to the only door, which had eight small panes of glass in its upper half. The door was locked but they could see in at the windows. There was a good-sized room on one side of the door, stairs going up right in front of it, and two small rooms on the other side whose windows looked right into the side of the hill where ferns grew as high as your waist, and there were stones lying about covered with velvet green moss.

There was a bandy-legged old cook-stove in the kitchen, a table and some chairs. And a dear little glass-paned cupboard in the corner fastened with a wooden button.

On one side of the house was a clover field and on the other a maple grove, sprinkled with firs and spruces, and separated from the house lot by an old, lichen-covered board fence. There was an apple-tree in the corner of the yard, with pink petals falling softly, and a clump of old spruces outside the garden gate.

“I like the pattern of this place,” said Jane.

“Do you suppose it’s possible that the view goes with the house?” said dad.

Jane had been so taken up with her house that she had not looked at the view at all. Now she turned her eyes on it and lost her breath over it. Never, never had she seen . . . had she dreamed anything so wonderful.

(snip, though I could happily quote the entire book)

Jane said nothing at first. She could only look. She had never been there before but it seemed as if she had known it all her life. The song the sea-wind was singing was music native to her ears. She had always wanted to “belong” somewhere and she belonged here. At last she had a feeling of home.

Although this reads like a happy ending, it’s actually just the beginning of Jane’s story. First she finds a house, then she makes a home, throwing herself into housekeeping with remarkable facility, fearlessly attempting everything from cooking to roof-mending to silver-polishing, and mastering pretty much all of it except pie crust (which, to Jane’s everlasting irritation, happens to be Aunt Irene’s specialty). At last, at last, Jane can do to her heart’s content. And once she starts doing, there is no stopping her. The formerly lonely and reserved child makes friends at every turn, reveling in the eccentricities of her Lantern Hill neighbors; she tackles a bit of matchmaking between some warmhearted old maids and the impoverished city orphan-child who was once her only friend; she even, in a farfetched yet somehow utterly believable turn of events, captures a runaway circus lion. The sight that causes her poor father such palpitations of the heart, as chronicled in the quote at the top of this post—his “only daughter stepping high, wide, and handsome through the landscape with a lion”—is a snapshot of the confident, collected girl Jane has become. The rest of the town is blown away by this lion-taming business, but Jane does not see what all the fuss is about. She saw a job that needed doing, and she did it. Neither foolhardy nor rash, Jane triumphs over the object of her fear by taking its measure and determining it to be a much weaker creature than its reputation allowed: he is a weary old cat, not a monster, she realizes; and armed with this knowledge, she is able to take command of the situation. Tyrranical grandmothers and meddling aunties had best beware.

Jane’s levelheadedness, her lack of drama even when dramatic events are unfolding around her, is part of what makes her such a refreshing heroine. She is not elfin and uncannily wise like Emily, nor precocious and preternaturally empathetic like Anne. She is no emotional firestorm, smashing her slate on someone’s head, engaging in bitter quarrels, or collapsing into sobs over a poignant daydream. Jane is an ordinary girl, with ordinary tastes and abilities, and that’s exactly what makes her story so satisfying: when we look at Jane we see just how extraordinary an “ordinary girl” can be.

This is the first installment of a new series/experiment. There are plenty of books I never liked, and that’s fine, but there are a few that I felt a kind of compunction to like, and was always kind of regretful that I didn’t So, (here’s the experiment part) I’m going to read them again, and see what I think now. The thing is, once I didn’t like these books the one time I read them as a child, of course I didn’t read them again, so I have limited, vague memories of why I didn’t like them, which makes it hard to hold up my side in discussion with everyone who love love loves them.

Anyway, first up is ANNE OF GREEN GABLES by L.M. Montgomery. This one is actually a slight exception to the group, because I

Anyway, first up is ANNE OF GREEN GABLES by L.M. Montgomery. This one is actually a slight exception to the group, because I never felt as much of a strong sense that I ought to like this book as a kid. But what’s puzzling is I loved Montgomery’s EMILY OF NEW MOON and its sequels, read them over and over again. Granted, they had the special appeal of a main character with my name, which I’m sure is what made me spot them and pull them off the shelf in the first place. Because I loved the EMILY series so much, I tried ANNE a few times over the years…and never got past the first couple of chapters, it was just too boring. So then I stopped trying it, until, as an adult, I discovered the deep love many of my friends have for the ANNE books (and movie, which I have not seen). So I gave it a shot last week, and definitely would have put it down again after a couple chapters if it hadn’t been for my determination to do this post. I will say, about half way through it got a lot more engaging, and while I don’t think I’d read it again I’m glad I got through it the once.

never felt as much of a strong sense that I ought to like this book as a kid. But what’s puzzling is I loved Montgomery’s EMILY OF NEW MOON and its sequels, read them over and over again. Granted, they had the special appeal of a main character with my name, which I’m sure is what made me spot them and pull them off the shelf in the first place. Because I loved the EMILY series so much, I tried ANNE a few times over the years…and never got past the first couple of chapters, it was just too boring. So then I stopped trying it, until, as an adult, I discovered the deep love many of my friends have for the ANNE books (and movie, which I have not seen). So I gave it a shot last week, and definitely would have put it down again after a couple chapters if it hadn’t been for my determination to do this post. I will say, about half way through it got a lot more engaging, and while I don’t think I’d read it again I’m glad I got through it the once.

I think the issue is that it has a lot of what I don’t like so much in the EMILY books, but amplified, and without much of what I do like. In both, I lose patience with the endless descriptions and have to skim - I started enjoying ANNE a lot more once I started skimming. But I find the devices used in the EMILY books to express that side of the character more believable, and less inclined to take over the whole character. Anne’s defining characteristic is her imagination - she gets lost in imaginings and forgets what’s going on around her, and talks endlessly about her imaginings and observations and how beautiful various trees are. Whereas Emily gets similarly lost in her writing, which for me is more believable than a 12 year old spending hours and hours just sitting and imagining; and Emily’s endless descriptions of how beautiful something is, etc come out primarily in her writing, so they don’t dominate her interactions with people and her whole character as much.

I think the issue is that it has a lot of what I don’t like so much in the EMILY books, but amplified, and without much of what I do like. In both, I lose patience with the endless descriptions and have to skim - I started enjoying ANNE a lot more once I started skimming. But I find the devices used in the EMILY books to express that side of the character more believable, and less inclined to take over the whole character. Anne’s defining characteristic is her imagination - she gets lost in imaginings and forgets what’s going on around her, and talks endlessly about her imaginings and observations and how beautiful various trees are. Whereas Emily gets similarly lost in her writing, which for me is more believable than a 12 year old spending hours and hours just sitting and imagining; and Emily’s endless descriptions of how beautiful something is, etc come out primarily in her writing, so they don’t dominate her interactions with people and her whole character as much.

Another key difference for me is that the other characters in the EMILY books are both more interesting and better developed than the supporting characters in ANNE OF GREEN GABLES. Emily’s friends are fully developed and have interesting and distinct personalities, whereas Anne’s friends are kind of flat and boring. And Emily’s adversaries are much more genuinely adversarial than Anne’s - there’s a clear parallel between Marilla in ANNE and Aunt Elizabeth in EMILY, but Marilla gives really only token opposition, whereas Aunt Elizabeth and Emily genuinely clash throughout much of the first book. Plus Emily has Aunt Ruth and her teacher to detest, whereas Anne has no parallel foes.

The reason I’m writing so much about the EMILY books in this post about ANNE OF GREEN GABLES is that most of my sense of ought-to-like-it for ANNE came from the fact that I loved the EMILY books. But I’ve now concluded that the EMILY books are really quite excellent, whereas ANNE is mediocre and kind of boring, so I am now content with my lack of ANNE love.

Next up in this series: Louise Fitzhugh’s HARRIET THE SPY. But maybe not for a little while, because its not the easiest thing to get yourself to sit down and read a book you think you’re not going to like, and two in a row is just too much. Besides, I have to go re-read the EMILY books now that I’ve thought so much about them.

Posted in Anne of Green Gables, Childhood Reading, Emily of New Moon, Flawed, however, can indeed coincide with uninteresting, Montgomery, L.M.

The weather! She has warmed here in NYC! The crocuses and daffodils and purple flowers that I can never identify are blooming in my front yard. The birds are singing and there are buds on the trees. Tis spring spring spring! To celebrate, we begin today with a poetic celebration of baseball (a very spring thing) written by none other than my father. You may have known that my mother was talented in this manner. So too mon pere. Enjoy!

The weather! She has warmed here in NYC! The crocuses and daffodils and purple flowers that I can never identify are blooming in my front yard. The birds are singing and there are buds on the trees. Tis spring spring spring! To celebrate, we begin today with a poetic celebration of baseball (a very spring thing) written by none other than my father. You may have known that my mother was talented in this manner. So too mon pere. Enjoy!

Oh, Jane, that practical, capable, matter-of-fact miss. At first it is easy to underestimate her: she seems to lack the spunk and impulsiveness that make Anne and Emily so entertaining. Anne has barely arrived at Green Gables when she’s blowing up at Mrs. Lynde; and Emily, my goodness, the way she bursts out from under the table quivering with rage at all the aunts and uncles criticizing her father after his funeral: could you help but applaud? But Jane seems so quiet, so put-upon, so cowed by her horrible grandmother. Sure, you can see she’s seething inside, but isn’t that the point? Anne and Emily don’t seethe: they erupt. You keep waiting for Jane to erupt, practically begging her to.

Oh, Jane, that practical, capable, matter-of-fact miss. At first it is easy to underestimate her: she seems to lack the spunk and impulsiveness that make Anne and Emily so entertaining. Anne has barely arrived at Green Gables when she’s blowing up at Mrs. Lynde; and Emily, my goodness, the way she bursts out from under the table quivering with rage at all the aunts and uncles criticizing her father after his funeral: could you help but applaud? But Jane seems so quiet, so put-upon, so cowed by her horrible grandmother. Sure, you can see she’s seething inside, but isn’t that the point? Anne and Emily don’t seethe: they erupt. You keep waiting for Jane to erupt, practically begging her to.

Anyway, first up is ANNE OF GREEN GABLES by L.M. Montgomery. This one is actually a slight exception to the group, because I

Anyway, first up is ANNE OF GREEN GABLES by L.M. Montgomery. This one is actually a slight exception to the group, because I never felt as much of a strong sense that I ought to like this book as a kid. But what’s puzzling is I loved Montgomery’s EMILY OF NEW MOON and its sequels, read them over and over again. Granted, they had the special appeal of a main character with my name, which I’m sure is what made me spot them and pull them off the shelf in the first place. Because I loved the EMILY series so much, I tried ANNE a few times over the years…and never got past the first couple of chapters, it was just too boring. So then I stopped trying it, until, as an adult, I discovered the deep love many of my friends have for the ANNE books (and movie, which I have not seen). So I gave it a shot last week, and definitely would have put it down again after a couple chapters if it hadn’t been for my determination to do this post. I will say, about half way through it got a lot more engaging, and while I don’t think I’d read it again I’m glad I got through it the once.

never felt as much of a strong sense that I ought to like this book as a kid. But what’s puzzling is I loved Montgomery’s EMILY OF NEW MOON and its sequels, read them over and over again. Granted, they had the special appeal of a main character with my name, which I’m sure is what made me spot them and pull them off the shelf in the first place. Because I loved the EMILY series so much, I tried ANNE a few times over the years…and never got past the first couple of chapters, it was just too boring. So then I stopped trying it, until, as an adult, I discovered the deep love many of my friends have for the ANNE books (and movie, which I have not seen). So I gave it a shot last week, and definitely would have put it down again after a couple chapters if it hadn’t been for my determination to do this post. I will say, about half way through it got a lot more engaging, and while I don’t think I’d read it again I’m glad I got through it the once. I think the issue is that it has a lot of what I don’t like so much in the EMILY books, but amplified, and without much of what I do like. In both, I lose patience with the endless descriptions and have to skim - I started enjoying ANNE a lot more once I started skimming. But I find the devices used in the EMILY books to express that side of the character more believable, and less inclined to take over the whole character. Anne’s defining characteristic is her imagination - she gets lost in imaginings and forgets what’s going on around her, and talks endlessly about her imaginings and observations and how beautiful various trees are. Whereas Emily gets similarly lost in her writing, which for me is more believable than a 12 year old spending hours and hours just sitting and imagining; and Emily’s endless descriptions of how beautiful something is, etc come out primarily in her writing, so they don’t dominate her interactions with people and her whole character as much.

I think the issue is that it has a lot of what I don’t like so much in the EMILY books, but amplified, and without much of what I do like. In both, I lose patience with the endless descriptions and have to skim - I started enjoying ANNE a lot more once I started skimming. But I find the devices used in the EMILY books to express that side of the character more believable, and less inclined to take over the whole character. Anne’s defining characteristic is her imagination - she gets lost in imaginings and forgets what’s going on around her, and talks endlessly about her imaginings and observations and how beautiful various trees are. Whereas Emily gets similarly lost in her writing, which for me is more believable than a 12 year old spending hours and hours just sitting and imagining; and Emily’s endless descriptions of how beautiful something is, etc come out primarily in her writing, so they don’t dominate her interactions with people and her whole character as much.

Ooh, thanks for the heads-up for the Mitali play! How awesome is that!?

Meanwhile, I would have to pass on the Victoria story as well… things you write when you’re ten generally only your mother loves.

Hooray for a play of Rickshaw Girl!

Your post title is something I kept singing when we were on vacation and the weather was gorgeous. The teen was a bit taken aback by the conclusion – I need to play him some Tom Lehrer.

I’m so glad you got the reference. I was half worried someone would berate me for propagating beer on a children’s literature blog.

“My heart with be quickening with each drop of strychnine . . . .”

Thanks so much for the shout-out, Betsy! We are so excited to be commissioning the stage adaptation of Mitali Perkins’ Rickshaw Girl! It’s such an amazing story with important themes, plus a glimpse into a different culture, and we hope our production will introduce the book to many children and parents who may have never heard of it. We’re also partnering with the Berkeley Public Library to help get the word out about our season, and they were super-excited about Rickshaw Girl in particular!