Last week marked two important events in the unfinished story of southern racial violence. On February 10, the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative released Lynching in America, an unflinching report that documents 3,959 black victims of mob violence in twelve southern states between 1877 and 1950.

The post Mississippi hurting: lynching, murder, and the judge appeared first on OUPblog.

By Tim Allen

Josephine Baker, the mid-20th century performance artist, provocatrix, and muse, led a fascinating transatlantic life. I recently had the opportunity to pose a few questions to Anne A. Cheng, Professor of English and African American Literature at Princeton University and author of the book Second Skin: Josephine Baker & the Modern Surface, about her research into Baker’s life, work, influence, and legacy.

Josephine Baker, as photographed by Carl Von Vechten in 1949. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Baker made her career in Europe and notably inspired a number of European artists and architects, including Picasso and Le Corbusier. What was it about Baker that spoke to Europeans? What did she represent for them?

It has been traditionally understood that Baker represents a “primitive” figure for male European artists and architects who found in Baker an example of black animality and regressiveness; that is, she was their primitive muse. Yet this view cannot account for why many famous female artists were also fascinated by her, nor does it explain why Baker in particular would come to be the figure of so much profound artistic investment. I would argue that it is in fact Baker’s “modernity” (itself understood as an expression of hybrid and borrowed art forms) rather than her “primitiveness” that made her such a magnetic figure. In short, the modernists did not go to her to watch a projection of an alienating blackness; rather, they were held in thrall by a reflection of their own art’s racially complex roots. This is another way of saying that, when someone like Picasso looked at a tribal African mask or a figure like Baker who mimics Western ideas of Africa, what he saw was not just radical otherness but a much more ambivalent mirror of the West’s own complicity in constructing and imagining that “otherness.”

Baker was present at the March on Washington in August 1963 and stood with Martin Luther King Jr. as he gave his “I have a dream” speech. What did Baker contribute to the struggle for civil rights? How was her success in foreign countries understood within the African American community?

These are well-known facts about Baker’s biography: in the latter part of her life, Baker became a very public figure for the causes of social justice and equality. During World War II, she served as an intelligence liaison and an ambulance driver for the French Resistance and was awarded the Medal of the Resistance and the Legion of Honor. Soon after the war, Baker toured the United States again and won respect and praise from African Americans for her support of the civil rights movement. In 1951, she refused to play to segregated audiences and, as a result, the NAACP named her its Most Outstanding Woman of the Year. She gave a benefit concert at Carnegie Hall for the NAACP, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Congress of Racial Equality in 1963.

What is fascinating as well, however, is the complication that Baker represents to and for the African American community. Prior to the war and her more public engagement with the civil rights movement, she was not always a welcome figure either in the African American community or for the larger mainstream American public. Her sensational fame abroad was not duplicated in the states, and her association with primitivism made her at times an embarrassment for the African American community. A couple of times before the war, Baker returned to perform in the United States and was not well received, much to her grief. I would suggest that Baker should be celebrated not only for her more recognizable civil rights activism, but also for her art: performances which far exceed the simplistic labels that have been placed on them and which few have actually examined as art. These performances, when looked at more closely, embody and generate powerful and intricate political meditations about what it means to be a black female body on stage.

Did your research into Baker’s life uncover any surprising or unexpected bits of information? What was the greatest challenge you experienced in carrying out your research?

I was repeatedly stunned by how much writing has been generated about her life (from facts to gossip) but how little attention has been paid to really analyzing her work, be it on stage or in film. The work itself is so idiosyncratic and layered and complex that this critical oversight is really a testament to how much we have been blinded by our received image of her. I was also surprised to learn how insecure she was about her singing voice when it is in fact a very unique voice with great adaptability. Baker’s voice can be deep and sonorous or high and pitchy, depending on the context of each performance. In the film Zou Zou, for example, Baker is shown dressed in feathers, singing while swinging inside a giant gilded bird cage. Many reviewers criticized her performance as jittery and staccato. But I suggest that her voice was actually mimicking the sounds that would be made, not by a real bird, but by a mechanical bird and, in doing so, reminding us that we are not seeing naturalized primitive animality at all, but its mechanical reconstruction.

For me, the challenge of writing the story of Baker rests in learning how to delineate a material history of race that forgoes the facticity of race. The very visible figure of Baker has taught me a counterintuitive lesson: that the history of race, while being very material and with very material impacts, is nonetheless crucially a history of the unseen and the ineffable. The other great challenge is the question of style. I wanted to write a book about Baker that imitates or at least acknowledges the fluidity that is Baker. This is why, in these essays, Baker appears, disappears, and reappears to allow into view the enigmas of the visual experience that I think Baker offers.

Baker’s naked skin famously scandalized audiences in Paris, and your book is, in many respects, an extended analysis of the significance of Baker’s skin. Why study Josephine Baker and her skin today? What does she represent for the study of art, race, and American history? Did your interest in studying Baker develop gradually, or were you immediately intrigued by her?

I started out writing a book about the politics of race and beauty. Then, as part of this larger research, I forced myself to watch Josephine Baker’s films. I say “forced” because I was dreading seeing exactly the kind of racist images and performances that I have heard so much about. But what I saw stunned, puzzled, and haunted me. Could this strange, moving, and coated figure of skin, clothes, feathers, dirt, gold, oil, and synthetic sheen be the simple “black animal” that everyone says she is? I started writing about her, essay after essay, until a dear friend pointed out that I was in fact writing a book about Baker.

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center. You can follow him on Twitter @timDallen.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Discussing Josephine Baker with Anne Cheng appeared first on OUPblog.

What Happens next? Trayvon’s Life Has to Count for Something! By Monica Hayes, Ed.D., MAT, MSW (Health and Education Consultant)

The discussions inthe media and on line have focused on a variety of perspectives. There have been calls for investigations and arrests and in too many cases calls for caution, so that we do not rush to judgment. The major judgment has already been made and acted upon. Young Trayvon Martin is dead; there was no evidence gathering, no statements taken...just assumptions and tragically misguided and unwarranted action. We have seen too many cases where the Black or Hispanci youth is arrested first, and questions asked later. Maybe.

The good news is that the loss of this young man seems to have touched millions and the parents are receiving much needed support in their quest for justice. The president's message gently reminded all parents about the senselessness of the act and the critical need for all of us to understand how such a tragedy could have happened.

On Meet the Press on Sunday morning, Ben Jealous, president of the NAACP, his voice evincing both angst and rage, reminded those who haven't yet connected the dots that this loss is pervasive. The neglect by law enforcement and the lack of justice across this country, he said, in response to the deaths of Black you regardless of whom or from which race/ethnicity the perpetrator comes is staggering.

The quiet rage that has been rumbling in the Black community is building. Some in the Hispanic communities are looking at the enmity that too often exists among young Blacks and Latinos. Thoughtful and mutually respectful Whites are wondering aloud how this can still be happening. On Sunday's Meet the Press, Doris Kearns, the noted presidential historian spoike poignantly about the youthful innocence reflected in young Trayvon's face. She likened the situation the that of Emmitt Till! Remember that injustice?

~~~~There's more! To read the rest from Dr. Mon's Place, please visit her blog.~~~~

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 6–May 13: Nashville, TN, to Birmingham, AL

Day 6 started with a torrential downpour–the first bad weather of the trip–that prevented us from walking around the Fisk campus and touring Jubilee Hall and the chapel. So we headed south for Birmingham, passing through Giles County, the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan, and by Decatur, AL, the site of the 1932 Scottsboro trial. We arrived in Birmingham in time for lunch at the Alabama Power Company building, a corporate fortress symbolic of the “new” Birmingham. We spent the afternoon at the magnificent Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, where we were met by Freedom Riders Jim Zwerg and Catherine Burks Brooks, and by Odessa Woolfolk, the guiding force behind the Institute in its early years. Catherine treated the students to a rollicking memoir of her life in Birmingham, and Odessa followed with a moving account of her years as a teacher in Birmingham and a discussion of the role of women in the civil rights movement. Odessa is always wonderful, but she was particularly warm and humane today. We then went across the street for a tour of the 16th Street Baptist Church, the site of the September 1963 bombing that killed the “four little girls.”

The rest of the afternoon was dedicated to a tour of the Institute; there is never enough time to do justice to the Institute’s civil rights timeline, but this visit was much too brief, I am afraid. Seeing the Freedom Rider section with the Riders, especially Jim Zwerg and Charles Person who had searing experiences in Birmingham in 1961, was highly emotional for me, for them, and for the students. As soon as the Institute closed, we retired to the community room for a memorable barbecue feast catered by Dreamland Barbecue, the best in the business. We then went back across the street to 16th Street for a freedom song concert in the sanctuary. The voices o

Here at Oxford, we love words. We love when they have ancient histories, we love when they have double-meanings, we love when they appear in alphabet soup, and we love when they are made up.

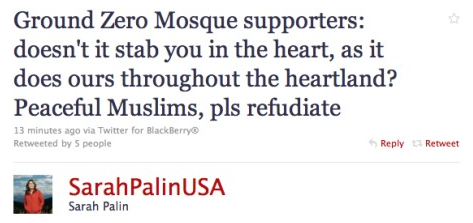

Last week on The Sean Hannity Show, Sarah Palin pushed for the Barack and Michelle Obama to refudiate the NAACP’s claim that the Tea Party movement harbors “racist elements.” (You can still watch the clip on Mediaite and further commentary at CNN.) Refudiate is not a recognized word in the English language, but a curious mix of repudiate and refute. But rather than shrug off the verbal faux pas and take more care in the future, Palin used it again in a tweet this past Sunday.

Note: This tweet has been since deleted and replaced by this one.

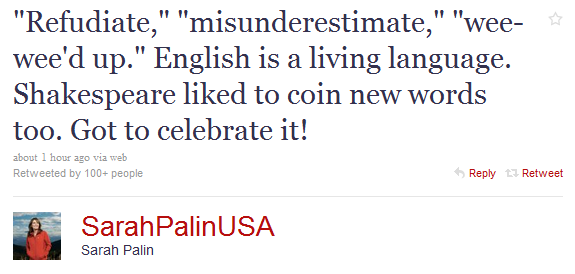

Later in the day, Palin responded to the backlash from bloggers and fellow Twitter users with this:

Whether Palin’s word blend was a subconscious stroke of genius, or just a slip of the tongue, it seems to have made a critic out of everyone. (See: #ShakesPalin) Lexicographers sure aren’t staying silent. Peter Sokolowksi of Merriam-Webster wonders, “What shall we call this? The Palin-drome?” And OUP lexicographer Christine Lindberg comments thus:

The err-sat political illuminary Sarah Palin is a notional treasure. And so adornable, too. I wish you liberals would wake up and smell the mooseburgers. Refudiate this, word snobs! Not only do I understand Ms. Palin’s message to our great land, I overstand it. Let us not be countermindful of the paths of freedom stricken by our Founding Fathers, lest we forget the midnight ride of Sam Revere through the streets of Philadelphia, shouting “The British our coming!” Thank the God above that a true patriot voice lives on today in Sarah Palin, who endares to live by the immorternal words of Nathan Henry, “I regret that I have but one language to mangle for my country.”

Mark Liberman over at Language Log asks, “If she really thought that refudiate was Shakespearean, wouldn’t she have left the original tweet proudly in place?”

He also points out that Palin did not coin the refudiate word blend. In fact, he says, “A

Elvin Lim is Assistant Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. See Lim’s previous OUPblogs here.

The NAACP was doing its job when it accused the Tea Party movement of harboring “racist elements,” but it didn’t necessarily go about it in the most productive way.

All it took was for supporters of the Tea Party movement like Sarah Palin to write, “All decent Americans abhor racism,” and that with the election of Barack Obama we became a “post-racial” society, and the NAACP’s charge was soundly “refudiated.” Or, as Senate Minority Leader, Mitch McConnell put it to Candy Crowley on CNN on Sunday, he’s “got better things to do” than weigh in on the debate. He was elected to deal with real problems, not problems made up in people’s heads. Case closed.

If one has decided not to see something, one won’t see it. (And to be sure, if one has decided to see something, one will always see it. That’s a stalemate.)

I think the NAACP ought to consider the possibility that the residuum of racism that exist today are more thoughts of omission than acts of commission. Racism is a very different beast today than it was on the eve of the Emancipation Proclamation, or on the eve of the Civil Rights Act. Indeed, it is so difficult to detect and even harder to eradicate precisely because it is no longer hidden behind a white conical hood.

Because our standard for what counts as “post-racialism” has gone up with each civil rights milestone, the NAACP should realize that as the old in-your-face racism is gone, so too should the old confrontational techniques of accusation and litigation. Unconscious racism can only be taught and remedied by explanation, not declamation.

To understand unconscious racism, consider the case of Mark Williams of the Tea Party Express, who was expelled by the Tea Party Federation, an organization that seeks to represent the movement as a whole when Williams posted a fictional letter to Abraham Lincoln, saying “We Coloreds have taken a vote and decided that we don’t cotton to that whole emancipation thing. Freedom means having to work for real, think for ourselves, and take consequences along with the rewards.”

The stridently mocking tone of this letter belied a breezy assumption that any and everyone could see that this was a l