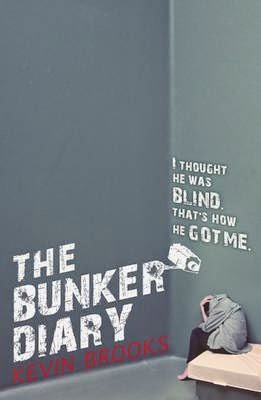

The Bunker Diary by Kevin Brooks. Carolrhoda Books. 2015. Reviewed from ARC.

The Plot: Linus, sixteen, wakes up, alone, in room. No good deed goes unpunished: he was helping a blind guy get some stuff in the back of a van, and, well, turns out the guy wasn't blind after all.

The Plot: Linus, sixteen, wakes up, alone, in room. No good deed goes unpunished: he was helping a blind guy get some stuff in the back of a van, and, well, turns out the guy wasn't blind after all.

And now he's in this bizarre place, with six bedrooms, a bathroom, a kitchen, and an elevator. There is no way in or out except that lift. And there are cameras and microphones. And he's being watched.

And then someone comes down in the elevator: a nine year old girl. And he realizes that there will be more, to fill those bedrooms....

The Good: The Bunker Diary takes place in the secure bunker where Linus finds himself trapped. One of the few things that is there is a journal, and Linus writes in it, and that's what we're reading.

The diary of his days, trapped. His memories of how he got there, his life before.

I'll be honest; this is not usually the type of book I'd read because, well. Sometimes I think I know what I like. But then I listen to other people rave about a book, people I respect, and I say, OK, let me try it. And usually I'm glad I did. This time? So glad I did.

The Bunker Diary is stunning, unforgettable, unpredictable, depressing, sad. While gradually we learn more about Linus's story, at the start he's a runaway who has been living on the streets. So he's a bit street smart, and has guts, and isn't stupid, even if he has been very alone. He's resourceful.

But the person who kidnapped him, and the five others who end up joining him, is also resourceful. And a planner. Because this is always Linus's story, we never find out the motivation of the kidnapper, of the person who put this all together. We can only guess.

In some ways, this is a depressing book. Because these people are trapped, stuck with each other, and with no real hope of escape. Part of the book is just the monotony of these people, in a small space, trying to get back and survive one more day.

And in some ways, it is a book that is not without hope. Which is funny to say, because this is a hopeless book. But Linus, who is no saint, is also no sinner. And he is kind. When nine year old Jenny shows up, Linus looks after her, does his best to protect her.

But there's only so much he can do. About being in the bunker. About Jenny. About the others who join them, who bring their own dangers. About the man who has trapped him there. Who watches. So he writes down what is happening and what he remembers and what he thinks he remembers.

Despite how heart breaking this was (or maybe because of it?), this is a Favorite Book Read in 2015.

Amazon Affiliate. If you click from here to Amazon and buy something, I receive a percentage of the purchase price.

© Elizabeth Burns of A Chair, A Fireplace & A Tea Cozy

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Kevin Brooks, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 10 of 10

Blog: A Chair, A Fireplace and A Tea Cozy (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: reviews, realistic, Kevin Brooks, Carolrhoda, 2015, favorite books of 2015, Add a tag

Blog: Death Books and Tea (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: book review, horror, kevin brooks, thriller, strength 4, the bunker diary, Add a tag

I can't believe I fell for it. It was still dark when I woke up this morning. As soon as my eyes opened I knew where I was. A low-ceilinged rectangular building made entirely of whitewashed concrete. There are six little rooms along the main corridor. There are no windows. No doors. The lift is the only way in or out. What's he going to do to me? What am I going to do? If I'm right, the lift will come down in five minutes. It did. Only this time it wasn't empty . .

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: David Thorpe, writing, Kevin Brooks, Hisham Matar, Add a tag

What is it that distinguishes a book written for adults where children are the main characters and one written for children, where children are the main characters?

When I am writing for children or teenagers at the back of my mind is always this question of the difference between the two.

"I recall now that last summer before I was sent away. It was 1979 and the sun was everywhere. Tripoli lay brilliant and still beneath it. Every person, animal and and went in desperate search for shade, those occasional grey patches of mercy carved into the white of everything."

The novel describes the gradual discovery by the child of his father's involvement in anti-revolutionary activity and what this means, and his desperate love for his mother.

Here are the opening sentences of The Bunker Diary by Kevin Brooks, which controversially won the Carnegie Medal in 2014:

"10.00 a.m."This is what I know. I'm in a low-ceilnged rectangular building made entirely of whitewashed concrete. It's about twelve metres wide and eighteen metres long. A corridor runs down the middle of the building, with a smaller corridor leading off to a lift shaft just over halfway down. There are six little rooms along the main corridor, three on either side."

Much has been written about Brooks' book and whether it is suitable for children, so I'm not going to stray into that territory. You might consider that I have chosen a non-typical example, but many children's books deal with uncomfortable themes and issues.

Both of these openings are physical descriptions which imply a sense of claustrophobia. They perfectly set the scene for what is to follow, which only gets worse.

The two books have several more things in common:

- there is no happy ending in either of them;

- very unpleasant things happen along the way;

- the main character is not conventionally likeable.

You can see other parallels from these extracts: the language in both is direct, the sentences straightforward. These stylistic points are undoubtedly a requirement for writing for children. But one can equally find instances of quite 'literary' writing in books for children, for example in the earlier novels of, say, Philip Pullman, such as A Ruby in the Smoke.

The Bunker Diary deals with important psychological and philosophical themes, that are uncomfortable to contemplate. So does Matar's book.

One aspect which perhaps distinguishes In The Country of Men (and other novels for adults) from most novels written for children is the retrospective angle: the narrator is now about 25 years old, and the narrative eventually catches up with him. This is less common in writing for children.

Another aspect that might signify a difference is non-linear storytelling, in which the narrative darts around in time. This is, again, less common in writing for children (however I did use this technique in my new novel Stormteller and, whilst I can't think of one at the moment, I'm sure I've read other children's books which do this).

The other observations to make about the difference between them are the setting (Gaddafi's Libya compared to contemporary London) and the degree of sophistication in the form of prior knowledge or experience that is assumed in the writing of Matar's book.

So to answer my original question, all other thngs being equal, the main aspect I am monitoring as I write for children rather than for adults is constantly gauging that level so it is pitched correctly.

I'd be very interested to know what you think about this topic?

David Thorpe is the author of Stormteller and Hybrids.

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Kevin Brooks, carnegie medal, Nicola Morgan, Blame My Brain, The Teenage Guide to Stress, Add a tag

(Reposting a post I wrote on my Heartsong blog a couple of weeks ago, because I still think it.)

I rarely review books but I did when Bunker Diary by Kevin Brooks first came out, so I'm on record as thinking it brilliant and brave. Now it has won the prestigious Carnegie Medal, and a storm has brewed. Many adults vehemently object to the book's bleakness, darkness and violence.

I’m not addressing whether it’s the right sort of book for the Carnegie because I want to tackle the wider issue of whether it’s right to write books like this for teenagers and whether it’s OK for them to read them.

I don’t seek to change the minds of those who dislike the book – anyone is free to dislike, even detest, any book. Many of the detractors are experts in children's books; their opinions are strongly held and well-meaning.

What I want to do is shed light on the following things, as someone who spends a lot of time thinking about adolescence, human nature and the psychology and science of reading:

- The reasons why many adults wish teenagers wouldn't read such books.

- The reasons why many teenagers do.

- Whether it matters that they do.

1. Why do many adults wish teenagers didn't read such books? Or, perhaps, that such books weren't written?

Good adults are programmed by biology and culture to protect babies and children. We protect them from actual harm and, when we can, from fears and nasty thoughts. We hope they never have to deal with nasty things themselves, though we realise many eventually will. We know, somewhere in the logical part of our brain, that they must learn to take risks, one day, but we try to control when that risk-taking happens and how. This is right and proper. We want to "protect their innocence" as long as possible. This is understandable.

When I did my first talk as a YA novelist at the Edinburgh Book Festival, I was floored by a question: "How do you feel knowing that you damage children?" It turned out that the questioner had 11 year-old grandchildren and since then I have often met this fear in parents or other relatives of that age group. Through my work, I understand how hard it is to move from being the parent of a child to the parent of a teenager. It's tough to let go. And tougher when it’s the young people themselves who insist on pulling away – as they are biologically driven to do. We don’t like the fact that some of them choose nasty books. We worry.

So, adults who protest against novels like Bunker Diary are being nurturing and protective. That's what we do with young children. At some point, however, we need to remove the cotton wool and tolerate bruises gained in the pursuit of knowledge and independence because they are not damaging. Bruises are temporary, after all.

Teenagers are not children. In the arguments about Bunker Diary, the word "children" has sometimes been used instead of "teenagers". This is not a small distinction. “Adolescent” means "becoming an adult", and that needs to be allowed to happen.

2. Why do many teenagers like bleak books?

First, let's remember that all readers, within any age range, are different; some teenagers will and some won't like reading such books. But why might some be drawn to dark stories? Because fiction is, among other things, for exploring emotions, testing them, feeling what experiences are like. Fiction is for breaking boundaries if we want to break boundaries, and for coming back safely as we wake up and realise that it was "only a story". Just as when we wake up from a nightmare we feel relief that it was only a dream. Sleep researchers tell us that a purpose of dreaming may be to process emotions, stresses and fears healthily. I argue that fiction has that role, too.

The magic of fiction is that we get carried away into the fictional world and almost forget that we aren't really there. That no one is; that it was all constructed inside a writer’s imagination. So strongly does this narrative transportation happen that we can end up having heated arguments about made up stories…

Teenagers often feel extreme emotions; their emotional and reward centres are highly active, bombarded by the changes in their lives, bodies and brains. Hardly surprising that they need extreme books, whether extremely frightening, passionate, funny, or sad.

And how do we practise empathy - that supreme effect of fiction - if we can't practise extremes of feeling? Those extremes will be different for each person. Each of us has our limits. I won’t argue with yours if you will allow me mine.

Teenagers don't always think the same things are horrible or for the same reasons as we do. Adults often require less or different stimulus to be shocked, saddened or scared. Many adolescents love watching horror films or reading misery memoirs. They sometimes feel the need to, perhaps to exorcise some of their fears, to practise the emotions, to test their limits. In safety.

In safety. Freely chosen. And you can stop the moment you want to. (In books, if not so easily in films.)

I remember the first time I cried in a film: Ring of Bright Water. You know the bit. The ditch. The spade. I was nearly twelve. I was shocked - and embarrassed because I didn't know films or books were things you cried in. (I was born and had lived all my life in a boys' school. Does that explain it? It did then. We didn't have YA fiction, either.) When my mother said of course it was OK to cry in a film, I wanted to watch it again, just to cry again. And, remember, RoBW is not fiction. (Actually, at the time I thought it was, which was probably a relief.)

Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. The bleakest fictional ending ever. The moment when Winston gives in to his torturers and betrays his girlfriend with the searing words, "Do it to Julia" and, later, betrays himself and the rest of humanity. I know, it's not a teenage book. But we make teenagers read it. We don’t tell them it’s too bleak for them.

3. So, does it matter that they often choose to read bleak books?

Hell, yes, it matters. It matters that they read, that they engage passionately and willingly with stories and reading. And it matters that if that is what they want to read, it's there for them. Whether it’s Nineteen Eighty-Four or Bunker Diary or whatever. It matters, too, in my opinion, that their choice is not disparaged. It matters that adults don’t imply that they are sick for enjoying it. (And adults are now using a vile term for books in which young people die. I'm not using it here as I think it's also demeaning to the readers of those books.) We don’t have to enjoy the books they choose but we should be very cautious before undermining their enjoyment and choices. (Not all the adults have - I'm just saying we should make sure we don't.)

On the other hand, carry on - teenagers like to read what adults don't like...

But doesn't it damage them? I think it might, conceivably, if you forced a young person to read a book that they didn’t want to read because it was making them feel things they didn’t want to feel or making their low mood worse. Or if the young person had to face ideas or scenarios they weren’t ready to think about. And if they had no way to process those ideas and fears healthily, by talking them through with others, for example.

I admit, too, that reading bleak books when you are already sad is not likely to be therapy. And that reading a book about suicide when you have suicidal thoughts yourself is a very bad idea. In The Teenage Guide to Stress, I recommend fiction as relaxation strategy, but I caution against reading books that make you feel sad if you are already sad.

But those are specific circumstances and Bunker Diary is not a book about suicide. Bunker Diary is a book in which the characters find themselves in a horrifying situation and try to work together to get out of it. (Regarding the Carnegie, I agree there's a possible issue because it's for a wide range of ages and there are shadowing groups, in which a younger than 12yo might be in a position of reading before he or she is ready. But the responsible adults will handle that situation with care, I'm sure. We can't exclude an eligible and highly recommended book because it only suits parts of the valid age range. Very few books suit a 9yo and a 14yo. Anyway, as I say, this isn't about the Carnegie argument.)

Books don’t damage – they do change and transform us. Everything we read and hear and see and think changes us. We are never the same at the end of an engaging book as we were when we started. And that's somewhat scary if you're a caring adult nurturing an adolescent. But we have to be brave and trust teenage (as opposed to younger) readers to make their own choices and feed their thirst for knowledge and ideas, so that they can decide for themselves.

A friend of mine told me how her then nearly-twelve-year-old daughter started reading The Lovely Bones. After a chapter or so, the daughter had to stop, too scared to read on. So scared that she buried the book under a pile of clothes in a cupboard. Next day she took the book out and read the whole thing. Her choice. She was ready. Changed but not damaged. At any time she could have stopped again - and she would have if it was making her feel awful. But she knew it was a story. She knew how to read it. She took control as she explored her emotions.

So, for those teenage readers who want to push the boundaries of their emotions, we need brave and risky books like Bunker Diary, even if it's too bleak for adults. If you can't block them from hearing or reading about the dark side of the real world in the news, don't try to stop them reading about such things in the safety of fiction, where they can explore and experiment on their own, without fear of actual harm.

Let go. Don’t stop caring, but worry less.

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Kevin Brooks, Louise Rennison, Beverly Cleary, Carnegie, Ramona, reality, Emma Barnes, Adrian Mole, humour, Add a tag

There was one of those flurries in the Children’s Book world recently – this time, over the award of the Carnegie, the UK’s most prestigious children’s book award, to the hard-hitting The Bunker Diary by Kevin Brooks. I’m not planning to write much about the controversy (I’ve included some links below) which I’d sum up by saying that some people feel that the Carnegie is forgetting its roots as a children’s book prize by so frequently rewarding the bleaker, and older, end of Young Adult fiction. But the debates that followed did make me think about what exactly we mean when we talk about realism in children’s books.

Because the number one point made by Brooks’ supporters, as it usually is when people complain about bleak children’s books, was the “real life is tough” argument.

“[Children] want to be immersed in all aspects of life, not just the easy stuff. They’re not babies, they don’t need to be told not to worry, that everything will be all right in the end, because they’re perfectly aware that in real life things aren’t always all right in the end.” Kevin Brooks

“the real world is so complex that unambiguously happy endings hardly exist” – author Robert Muchamore

“Children and teenagers live in the real world; a world where militia can kidnap an entire school full of girls, and where bullying has reached endemic proportions on social media” Carnegie Chair of Judges, Helen Thompson

We certainly do live in a grim world. Reading the newspaper can be more heart-breaking than any children’s book. But I’d question whether this explains the preponderance of bleak fiction (and am I being cynical to feel, that if teenagers were truly deeply interested in the worlds’ troubles, there might be more translated foreign fiction available for UK children, instead of, as is actually the case, virtually none?)

For most British children, for all the challenges they face, being imprisoned by a psychopath probably isn’t one of them. (Amazingly the 2014 short list featured two books on the “imprisoned by psychopath” theme – the other by Anne Fine.) Terrorist attack, extreme violence, heroin addiction...these are also very small (though terrifying) risks to most under eighteens, living in a Western world where (though it’s sometimes hard to remember) violence is actually in long-term decline.

Or take childhood cancer. John Green’s The Fault In My Stars is just one the latest of many books where children or teenagers die of terminal cancer. By contrast, I CAN’T THINK OF A SINGLE BOOK WHERE THE CHILD HAS CANCER AND GETS BETTER. And yet, the reality is that about 75% of children do get better. Wouldn't it be great – not least for those children with the disease – if some of the award-winning fiction out there also reflected that reality?

In short, you don’t need to think that children’s books should be all fluffy bunny rabbits and happy ever after to wonder if some so-called “realistic” children’s fiction is...well, actually not that realistic.

Myself, I’ve always thought of “realism” not in association with YA grit but with certain twentieth century American authors: from Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books, through Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy, to Judy Blume’s Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing or Katherine Patterson’s Gilly Hopkins the Great.

Perhaps the supreme example would be Beverley Cleary’s Ramona books. Following the adventures of Ramona Quimby and her family and friends over a number of years, and set in Portland Oregon, these books are breathtaking in their ability to distil the ordinary and humdrum into entertaining fiction.

Beverley Cleary never relies on dramatic events. (She even avoids dramatic titles, with such understated gems as “Ramona and her Mother” and “Ramona Quimby , age 8”.) There are problems for sure – Ramona’s dad loses his job, for example – but as we see things always through Ramona’s eyes, this is on a par with such problems as her class teacher not liking her very much. There is humour (the teacher told me to sit there “for the present” – but I didn’t get any present, Ramona complains). But it’s a gentle, observational humour. There is death (Picky Picky the cat) but no truck with sentimentality (Ramona and Beezus set to work to bury Picky Picky before their parents find out). There are fears to be overcome – confronting a mean dog – and temptations – how can Ramona resist pulling the blonde curls of Susan who sits in front of her in class, however many times she is told off by her teacher? But it is all grounded in a child’s everyday experience.

Beverley Cleary recalled in her memoir,“I longed for funny stories about the sort of children who lived in my neighbourhood.” And she could see that the children she met while working as a librarian felt the same.

Then, as now, this kind of “realism” was often ignored by critics and award-givers. Cleary has been showered with honours and prizes – but that was after her books had proved themselves enduringly popular with young readers. And they still are. I know British children today who ADORE them – because that small town, domestic American life, however distant it is in time and place, still feels absolutely real.

It’s easy to overlook the skill and imagination involved in creating something small scale. As the great mistress of domestic realism, Jane Austen, long ago said of her work, it is “ the little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory on which I work with so fine a Brush, as produces little effect after much labour". It look easy – but

it isn’t.

Take out the big emotional tear-jerking scenes, the drama of life and death, good vs evil, and what do you have left? The common-place. The everyday. The mundane. And creating something entertaining and captivating out of the mundane is challenging – maybe more challenging than “the big stuff”.

Yet it’s always been an important aim of fiction. Cleary said that she always remembered her college lecturer's advice that a novel should seek to explore universal themes through the minutiae of everyday life. I also like this quote from another writer, Susan Patron, about Cleary. “She showed me that the inner life of any child, the dynamics of family and pets, can be captured as rich, comic, fascinating, poignant, and meaningful."

I’m not sure this type of “realism” has ever been as celebrated in British children’s books, although it is an important part of the appeal of writers such as Jacqueline Wilson and Anne Fine (although their prize-winning books are more “issues” led) or Hilary McKay. With the humour ratcheted up, it’s also the bedrock of Sue Townsend’s Adrian Mole or Louise Rennison’s Georgia Nicolson (I confess the near-death of Georgia’s cat Angus moved me more than any gritty YA novel) and much other comic fiction. It’s even been recognised by the Carnegie in the past, in such books as the groundbreaking The Family From One End Street (one of the first children’s books to feature the everyday life of a working-class family) and The Turbulent Term of Tyke Tyler.

There are lots of joys to be had from fiction, and realism is only one of them. I love fantasy and adventure as much as I love the fiction of the everyday. But I’ve also found that it is often the grounded, “real life” books that are the ones that, as child and adult, I have returned to again and again. There is a particular and lasting joy in reading something “real” and recognising the settings and characters.

Let's celebrate it!

CJ Busby's ABBA post on Carnegie criteria

Bunker Diaries storm in Guardian

Bunker Diaries storm in Telegraph

Bunker Diaries storm: Amanda Craig vs Robert Muchamore

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Emma's new series for 8+ Wild Thing about the naughtiest little sister ever (and her bottom-biting ways) is out now from Scholastic.

"Hilarious and heart-warming" The Scotsman

Wolfie is published by Strident. Sometimes a Girl’s Best Friend is…a Wolf.

"A real cracker of a book" Armadillo

"Funny, clever and satisfying...thoroughly recommended" Books for Keeps

Emma's Website

Emma’s Facebook Fanpage

Emma on Twitter - @EmmaBarnesWrite

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Young Adult, horror, Kevin Brooks, Carnegie, Add a tag

"Oooh, that's a bit bleak..."

I'd just told a friend of mine the plot of a short story I am about to pitch to a reluctant reader publisher. And he was right. The ending isn't just a bit bleak - it's abysmally bleak. A real kick you in the stomach-type affair.

But I don't think I could tell it any other way. The story needs to ends with a sucker punch. If everything turns out fine and dandy, it would lose all of its meaning.

It has made me think though. This week, I received copies of my latest reluctant readers from Badger Learning - Billy Button and Pest Control. Both of them end with the protagonist in deep water. Come to think of it, my last two books for Badger were pretty bleak too.

It's probably because they've been conjured up from the same part of my brain that used to enjoy late-night Amicus portmanteau movies such as Vault of Horror and From Beyond the Grave. In fact, what am I saying - I still enjoy them today. Horrible things happening to horrible people - and even sometimes nice people as well. The 70s and 80s were full of horrid little morality tales like these, from the wonderfully macabre Tales of the Unexpected to excesses of Hammer House of Horror.

I guess my recent run of reluctant reader books have come from the same stable. Stories to unsettle and to chill.

And why not? Children like to be scared. It stimulates a different part of their imagination and teaches them valuable lessons - that darkness is just as much a part of life as light. And where better than to experience these emotions than safely curled up reading a book.

Indeed, according to Kevin Brooks, recently crowned winner of the Carnegie medal, books should actively show children that life doesn't always include happy endings. He wasn't talking about the cheap scares of 70s horror movies of course, but novels that deal with the harsher sides of life, subject matter that is sometimes difficult to write about, let alone to read.

Quoted in the Telegraph, Brooks says:

“There is a school of thought that no matter how dark or difficult a novel is, it should contain at least an element of hope.

"As readers, children – and teens in particular – don’t need to be cossetted with artificial hope that there will always be a happy ending. They want to be immersed in all aspects of life, not just the easy stuff. They’re not babies, they don’t need to be told not to worry, that everything will be all right in the end, because they’re perfectly aware that in real life things aren’t always all right in the end."

“To be patronizing, condescending towards the reader is, to me, the worst thing a Young Adult fiction author can do.”

Cavan Scott is the author of over 60 books and audio dramas including the Sunday Times Bestseller, Who-ology: The Official Doctor Who Miscellany, co-written with Mark Wright.

He's written for Doctor Who, Skylanders, Judge Dredd, Angry Birds and Warhammer 40,000 among others. He also writes Roger the Dodger and Bananaman for The Beano as well as books for reluctant readers of all ages.

Cavan's website

Cavan's facebook fanpage

Cavan's twitterings

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Kevin Brooks, violence, Meg Harper, the myth of redemptive violence, Keith Grey, Edinburgh Fringe, 'In a 1000 pieces', Greenbelt, 'Crossing the Line', Add a tag

Tonight I've been reading Gillian's excellent post about knife crime, hot on the heels of the horribly disturbing report about the two brothers who attacked two other boys, hitting one on the head with a sink, forcing them to commit sexual acts and leaving one so battered he was unconscious. Last week I was at the Edinburgh Fringe watching a profoundly moving piece of theatre entitled 'In a thousand pieces' about sex traffiking – girls lured into thinking they will be moving to education and a better life and ending up being carted from British city to British city where they are raped 50 times a day and never see the outside world. As a volunteer school counselor in an inner city school, I have heard stories not so disturbing that they'd hit the Misery bookshelves, but far too violent and unpleasant to be accepted by a YA publisher. One of my own sons has been mugged twice. At the weekend I was at the Greenbelt Christian Arts Festival, listening to a talk about the myth of redemptive violence in Disney movies – time and again we see the only solution to the bad guy being to kill him or her. You worry about violent video games? Saturation in violence starts much younger than that – aren't you worried about that? That was the question being raised.

'But,' said a teenage voice from the floor, 'it's kill or be killed.'

'It's a violent world,' said another young man. 'You've got to get used to it – the sooner the better. Then it's not such a shock later.'

I got chatting to the latter young man on the way out. 'You really think that, do you?' I said. 'That it's a violent world – get used to it?'

'Yeh,' he said. 'There's nothing you can do – you've just got to get on with it. It's human nature.'

'But,' said a friend who was with me (a published poet incidently!) 'so's adultery. Should we just get used to that too?'

'Yeh,' said the young man. 'You might as well.'

On the other hand, I had a youth theatre parent complaining about the use of the word 'bastard' in a YT play being created by 12-14 year olds because she didn't want her daughter to grow up too soon- and I'm sure the editors I've met would be on her side.

I find all this profoundly depressing and I'm sure we all ask ourselves about our role as writers here – observers, moral guardians, activists, entertainers? But my other question is where are the books that reflect this world? I haven't read 'Crossing the Line' but it sounds like it does. Bali Rae's books do I think and possibly Kevin Brooks' and Keith Grey's – but there aren't many. When I suggested a series of books about a gang of young kids, such as those who kick around our estate, unsupervised and at hours of the night abhorrent to parents who are doing bedtime routines which end in a story and a kiss, my agent just laughed. No publisher would publish them because it is middle-class parents and librarians who buy books and they wouldn't want young children reading about dodgy street gangs, apparently. So we all end up reading about a very nice world inhabited by remarkably nice people to whom nothing terribly beastly ever happens – or we read fantasy. Sorry – is there a difference? Isn't it all fantasy?

I haven't met many editors but inevitably they've all been very well- educated and have been well and truly middle class. (They've all been stick-thin too, which is very annoying seeing as they have a sedentary lifestyle!) Most of them have been young and haven't had children. A significant number seem to be products of independent rather than state education. Do they know what it's like to be a kid growing up in today's violent world? I only have the vaguest of insights myself, despite having 4 teenagers and despite spending a large part of my working life working with young people. And we wonder why such a minority reads books.

It's great that 'Crossing the Line' is out there. But where are the books for younger children reflecting our modern world? Is there a raft of books that I have missed? Who is going to publish them? Supposing they are published, which librarians will stock them and which teachers will be bold enough to read them to their classes? And, most importantly, who is going to write them?

One of the endless conundrums of fiction. Do we read it to escape reality – or to embrace it? Do our readers want time away from their lives – or the reassurance that others have been there too?

PS. Sorry there's no picture! My computer died today and I'm using my husband's - and he doesn't have photos of me!!!

Blog: The Penguin Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Web/Tech, Fairytales, kevin brooks, //wetellstories.co.uk, april fools day, Add a tag

... in an office building on the Strand, we had an idea to make a story that was a game and a game that was a story. We called it We Tell Stories and tens of thousands of people looked at the site and wandered around St Pancras station and followed fictional characters on Twitter.

Well, the third story is now up and running and if you like your fairytales both personalizable

and dark you will enjoy this. Kevin Brooks, author of the brilliant Black Rabbit Summer, has constructed the building blocks for a traditional, yet melancholy fairytale. Putting them together is down to you. Go have a play and let us know what you think.

In other news, those wags at the BBC today announced the discovery of flying penguins. Of course we didn't fall for this lame April Fool gag here at Penguin Towers. Everyone knows Penguins can't fly.

Jeremy Ettinghausen, Digital Publisher

..............................................................................

..............................................................................

Add a CommentBlog: The Penguin Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: social networks, kevin brooks, bookcrossing, kevin brooks, free books, Books, social networks, bookcrossing, Add a tag

Keep your eyes peeled for free copies of teen author Kevin Brooks' latest dark thriller - Black Rabbit Summer - in the least likely of places. Penguin have teamed up with US site bookcrossing to release 100 of the books 'into the wild' as those in the know call it.

If you've not come across this phenomenon before, bookcrossing is the warm-fuzzy-feeling-giving practice of leaving a book in a public place to be picked up, read and enjoyed by someone else, who then does the same once they’ve finished it. The books are registered on www.bookcrossing.com – which tracks the titles as they make their literary journeys across towns, cities, countries, and sometimes even oceans.

60 of the books will be lurking in clothes store USC (watch out for them amongst the Deisel trainers and Bench hoodies), and the rest left on buses, tubes and trains and in pubs and cafes around the capital. If you are lucky enough to find one, stay true to the spirit of bookcrossing, read it and pass it on.

60 of the books will be lurking in clothes store USC (watch out for them amongst the Deisel trainers and Bench hoodies), and the rest left on buses, tubes and trains and in pubs and cafes around the capital. If you are lucky enough to find one, stay true to the spirit of bookcrossing, read it and pass it on.

Jodie Mullish, Publicity Manager, Puffin

..........................................................................

...........................................................................

Blog: librarian.net (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: war, petition, haters, armstrade, elevier, reedelevier, weapons, Add a tag

Rory has more information at Library Juice and you can read this earlier post concerning the controversy regarding Elsevier’s involvement in “organizing weapons trade shows attended by representatives of the world’s militaries.” They got pressured, people sent a petition. They backed down. I think this is sort of good news.

armstrade, elevier, petition, reedelevier, war, weapons

Brilliant post, Meg. I live in a middle class area, but my kids have been through state school and some of the stuff their friends get up to is closer to Skins than Enid Blyton. There's some quite hair-raising abuse going on even amongst the middle classes, too - gangs may stalk the estates, but domestic abuse is all over the place.

I agree - there is violence in song lyrics, on TV, in the streets. Surely there is space for books to be a haven for those that want one and yet a reflection of reality for those who want their world acknowledged?

The escape/embrace dichotomy brings us back to Aristotle and catharsis, surely? In books, we experience fear and terror in a safe environment. Some people also experience them in an unsafe environment. It is all part of the human experience, as your teenager noted. Whether we respond with hope, despair, rage or whatever is personal, and all art has a role in reflecting and suggesting responses.

My book (When I was Joe, to be published by Frances Lincoln in January) touches on gangs and knife crime and suchlike. I've tried to convey the fear that children can feel on the streets, and the solutions they come up with. I do hope you're not right about the middle-class parents!

I don't think fiction should reflect reality. It must do something more sophisticated than that. It must focus on aspects of reality and infuse them with meaning, and by so doing add something of value to the world.

A book that just showed a violent reality (as it exists on our streets, for instance) would be worthless. But fiction does more than show; it also comments, however obliquely. It selects, it spins, it finds the unexpected good and the lurking evil. It (why not admit it?) teaches.

A popular theory as to why we dream suggests that dreams are lessons fashioned by our brains, to better prepare us for harsh reality without always exposing us to its dangers. Dreams teach and train us in a safe environment. I believe that stories evolved for a similar purpose.

So: we must never shy away from hard reality. But neither do we merely reflect it. Stories are worth far more than reportage.

Such a great and thought-provoking post, Meg, and thank you for your comments on mine.

I think it's not so much the distinction between fantasy and reality as between sanitised violence and the true kind with all its consequences. You get the latter in fantasy fiction too. I don't know when it's appropriate to introduce children to the real horrors of the world - I'm flying by the seat of my pants with my own two - but I do know I want them to learn that death is not dealt out by magic wand, instantaneous and bloodless (and transient, in the case of Xbox games, which is the part of them I find alarming). I want them to learn it gradually, and I hope gently, but I do want them to know it.

(I'm not having a go at Harry Potter though - I don't see why children can't have both.)

Keren, I'm really looking forward to 'When I Was Joe'. It sounds fantastic.

Nick - you just told me why I have a slight problem with the film Fish Tank, which I saw the other day. It's very good, but I didn't enjoy it. It's too realistic. And only realistic.

I've got a fair amount of violence in my writing (I can get away with exactly what I like, of course), but it has nothing to do with reflecting reality - rather with reflecting my characters' reality.

I was speaking to some teenagers the other day and asked them how they would feel if the main character in a book died. I mentioned that one author I had spoken to told me her publisher had asked her to change the ending because they didn't think the character should die in a book for teens/YA. Their response was that this kind of thing was treating them like babies. They could handle it and wanted the opportunity to make their own choices, not to be spoon fed.

In my book Spider the characters have to deal with the consequences of their actions, sometimes ill-judged actions and unpleasant consequences but I have had young people tell me that they hadn't considered what might happen if they went out 'joyriding' but the book made them realise what could happen.

I feel that is what fiction is all about - allowing young people to experience things through the characters and to see beyond their own life experience. It can perhaps give some insight into the lives of others.

We are not there as gatekeepers or to educate or expose but we lay out possibilities and experiences to allow others to try on someone else's skin for a bit.

I'm reading all this and I'm thinking 'Yes, yes, yes!' to all of it! I once got a review in the TES which didn't like my too evident 'moral purpose' in one of my books. I wanted to jump and down and object vociferously - OK, if the reviewer had read 'moral purpose' I had to take the rap but it wasn't what I was intending - it was what Linda is saying about laying out possibilities and experiences and allowing others to try on - not being didactic but creating an ambiguity in which issues are raised to be pondered upon. But that there is story too, is crucial - or who wants to carry on reading? Who will remember? I don't remember much of what Paul writes in his epistles but I remember Jesus' parables! And I really hope Keren's book sells loads - sounds like just the sort of thing I'm hoping gets published! I'll order a copy!

Oh thank you Meg, how nice of you!

I think it's interesting that a dystopian novel like The Hunger Games and its sequel Catching Fire are such big hits, absolutely full of violence - very cleverly so - and yet seemingly uncontroversial.

For me, I know my children live in a violent world and they know it too. It seems natural to write about it.

That there is violence in the world, and that the world is violent are two different statements. The media would certainly have us believe the latter.

In writing as in painting, it is much easier to create dramatic impact by violence than otherwise. The impressionist painters are so widly loved at least in part because they painted happiness, beauty and love with impact and without banality. How hard is that? Very.

Whatever happened to Anne Shirley? Would she be published today?

Frances

I think Anne Shirley is of her time but there is plenty of feel good fiction out there. It tends to sell well and I wish I could write it.

I write fantasy violence because I think children live with the reality of physical threat a lot of the time and deaing with it in fantasy means that you can make it real but in a diferent space, without the familiar context. It is removed, slightly sanitised and maybe cathartic because of that.I don't feel I could do what I do in a contemporary setting.

Got to disagree with you, Frances, that creating dramatic impact with violence is easy. Done badly it can be just as boring and banal as sweetness-and-light done badly. I don't think anyone who has commented here does write violence in a banal way - yes, it does take time and effort, and it is hard. The quality of the writing is nothing to do with the degree of violence. There are some pretty bad pseudo-Impressionist paintings, after all.

It comes back to the old story - there is room for both.

"I don't think that anyone who has commented here has done violence in a banal way". Oh, I do hope that I didn't suggest such.

Violence is obviously open to very wide definitions: my cat crunching the baby bird: darfur: tutsi: afghanistan etc. What word can encompass such? A death may be quite acceptable, indeed inconsequential, as Linda Strachan says.Indeed.

I'm a non-author, just musing: are violent video games and films ok? Quite possibly yes. If violence is suitable for the mainly middle-class children who read books, shouldn't it also be suitable for others, including the illiterate? (And yes, I do know that maybe all children play video games.) Iwould think that many contributors would agree with that.

At the same time, as society changes, as it does, it seems that all media must be contributing to that change, to some extent. Should they take responsibility for this? Should they be interested in the direction of change, and concerned as to what extent they are orchestrating and signposting the change? I would think that they should. Of course those sections of the media concerned just with profit will have different agendas from those of authors. I think.

I happen to regret that so many young childre's films, eg, even apparent innocuities such as "Nemo", start off with the death - usually violent, car crash or such, - of a parent. This often seems gratuitous...but, it grabs attention, does it not? It's hard to find a child's film without this violent intro. If anyone can suggest to me films of real people, suitable for babes, and lacking these horrors, I would be grateful. And yes, I do understand that this is a different media from fiction.

Will baby fiction catch up to film and YA soon? Of course. Under the guise of "reality" that YA operates under, I expect that enterprising authors will hit younger and younger children with "reality". I recommend that you get in quickly, to catch the wave. Frances

I agree with so many of these thoughtful comments. And I believe that as Nick suggests, there is less of a gap between 'fantasy' and 'realistic' fiction than is often thought. All fiction is make-belief: it answers or attempts to answer the 'what-if's' in life.

I find that themes emerge in my books as I write, which were never consciously planned but rather a consequence of following my characters through sets of circumstances, and seeing how they behave. Subconsciously, however, they must stem from my own concerns or observations about the world. So in 'Troll Blood', a theme emerged of violence and how my main character (a quiet, unassuming lad)was going to deal with someone very violent and also very charismatic, in a culture (the viking culture) which made heroes out of men we would now regard as murderers. And I wanted to show that a sword (an iconically glamorous fantasy weapon: think Excalibur or Anduril)is just the same as a gun or a knife. The book ended up being, for me, a serious exploration of attitudes to violence, and the elements of fantasy and self-deceit implicit hero-worship.

Nobody has ever criticized the book for being too violent, despite its several murders - and I think this is because, cloaked as 'fantasy', critics automatically assume the book cannot be relevant.