Recently Slate decided to create a “pop-up blog” of sorts with a concentration on children’s literature. They’ve called it nightlight. A good name. We would have also accepted “flashlight under the sheets”. In any case, I was initially worried that this would be another case of writers who have just found themselves to be parents writing the same articles we’ve seen a million times before about the usual. And while their writers aren’t children’s literature experts, they’ve surprised me with the quality of their pieces. There was one defending Anne Carroll Moore in a very balanced manner, one on branded children’s books, and one on the rise of LGBTQ stories for families. Yet the one getting the most attention so far is We Don’t Only Need Diverse Books. We Need More Diverse Books Like the Snowy Day.

Professor Ebony Elizabeth Thomas was the person who raised some concerns about the piece in a series of posts the fell under the title Should *The Snowy Day* Be the Example for Diverse Children’s Books?

In the piece Ms. Thomas discusses something that’s always sort of struck me as difficult when we discuss the Keats classic. A classic that I should say I adore, mind you. But consider a situation I encountered about a year and a half ago. From December 10, 2014 through February 7, 2015, the Grolier Club hosted the exhibit One Hundred Books Famous in Children’s Literature. It was a once in a lifetime opportunity. Collectors from all over the country donated their most precious pieces, bringing together titles never seen together before (and probably never to be seen again). I was floored by some of the offerings. It was only as I looked through them that I began to get a nagging sensation that it was awfully awfully awfully white. In fact, the sole dark face I saw (aside from Uncle Remus on a cover) was Peter’s on The Snowy Day. Coward that I am, I didn’t bring this up at the time. Had I, I suspect the answer would have been similar to the justification given for the inclusion of Harry Potter. Mainly, that the exhibit was only covering “books famous”. And after all, how many diverse children’s books are overwhelmingly famous?

Well . . . quite a few, but let’s first consider why it is that The Snowy Day was included. It was a groundbreaking work during its day (and if you haven’t read the K.T. Horning story of its history or heard about Andrea Davis Pinkney’s upcoming and eerily lovely bio of Keats A Poem for Peter then do so now). Often I hear people say that it was the “first” picture book featuring a black protagonist on the cover. Or that it was the “first” picture book where the color of his skin was incidental. I am not a scholar in the field, but this sounds sketchy to me. Let us consider something else that Ebony Elizabeth wrote in that recent post:

“Where has the mainstream media covered Black authors & illustrators of books for children published in the 60s & 70s that are out of print?”

That got to me. She’s dead right. Because Keats was wonderful but he was by no means the only guy making books about African-Americans out there. A lot of Black authors and illustrators books were out there at the time (paging Langston Hughes). Consider the 2014 Walter Dean Myers article in the New York Times Where Are the People of Color in Children’s Books? Actually, no. Scratch that. Go back further. Look at the 1986 Walter Dean Myers article in the New York Times I Actually Thought We Would Revolutionize the Industry. He writes:

“By the end of the 60’s the publishing industry was talking seriously about the need for books for blacks. Publishers quickly signed up books on Africa, city living and black heroes. Most were written by white writers. In 1966 a group of concerned writers, teachers, editors, illustrators and parents formed what was to be called the Council on Interracial Books for Children. The council demanded that the publishing industry publish more material by black authors. The industry claimed that there were simply no black authors interested in writing for children. To counter this claim the council sponsored a contest, offering a prize of $500, for black writers. The response was overwhelming . . .

. . . In 1974 there were more than 900 children’s books in print on the black experience. This is a small number of books considering that more than 2,000 children’s books are published annually. But by 1984 this number was cut in half. For every 100 books published this year there will be one published on the black experience.”

Now let’s double back to Ebony Elizabeth’s question. I repeat, “Where has the mainstream media covered Black authors & illustrators of books for children published in the 60s & 70s that are out of print?”

Well, shoot. I’m mainstream media, right? And out-of-print titles are a delight to me. And yet I have never seriously considered just how many Black penned and illustrated children’s books have disappeared from the public consciousness.

Here’s something else I realized. There are publishers out there that reprint out-of-print titles. Folks like New York Review of Books and Phaidon and such. Yet even in the era of We Need Diverse Books, not a single publisher has ever created an imprint specifically designed to reprint classic and older multicultural children’s literature. Correct me if I’m wrong about this. I’d love to be wrong. But at this moment in time, I haven’t seen a publisher fully commit. Which is to say, there is a gap in the marketplace.

Today then, let’s conjure up a list. Since we began with The Snowy Day, let’s limit it today to picture books by and about African-Americans. I want you to tell me your favorite out-of-print titles. The stipulation is that they have to have been published by a major publisher, they have to feature Black characters, and they have to have been written and/or illustrated by someone African-American. To do this list properly I wish I still had access to New York Public Library’s lists of The Black Experience in Children’s Books dating back decades. In lieu of that, I’ll just start with my own personal favorites.

Here are the books that should be reprinted and reprinted right now.

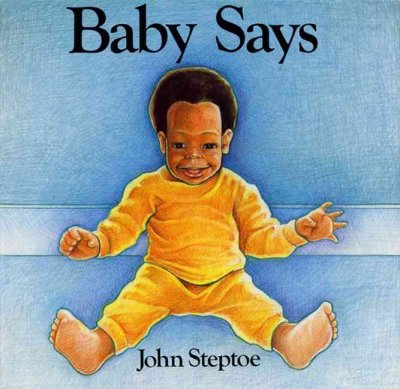

Baby Says by John Steptoe

I’m beginning with the most egregious of the errors. There are a lot of out-of-print Steptoe books to choose from, but this is the one that’s the weirdest. I mean, Harper Collins itself basically acknowledged that this book was a classic when they included it in their Harper Collins Treasury of Picture Books Classics (<—see? In the title and everything!) That book contains everything from Goodnight Moon and Harold and the Purple Crayon to If You Give a Mouse a Cookie and, you guessed it, Baby Says. So I decided to do some checking. Are any of the other stories in this book out-of-print? Yes. One other – George Shrinks. Be that as it may be, I’d argue that Steptoe’s book is board book perfection. My son, who is two, specifically asks for the “baby book” in that collection and I have read it over and over and over again. So what exactly is going on here? Why is it out-of-print?

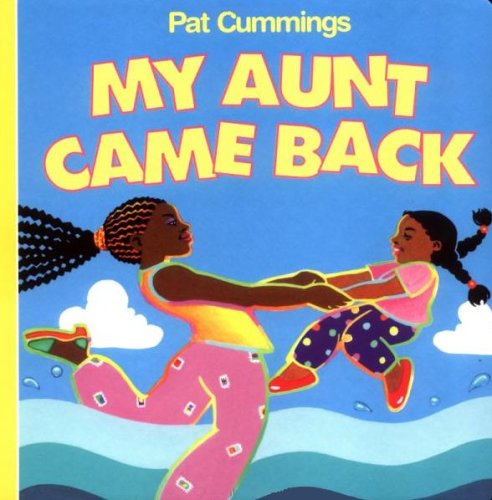

My Aunt Came Back by Pat Cummings

This one also makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up in fury. A brilliant book. A fun, catchy, magnificent board book that’s so colorful and delightful that you’ll be happy to read it over and over again. So why exactly is it out of print? Again it’s a Harper Collins title. So, uh, hey, HC. You guys are big. You have a back catalog that’s immense and impressive. Why not start that out-of-print diverse imprint I was just talking about? You clearly have the stock.

The Everett Anderson book series

Had to do some research on this one. As it happens, Everett Anderson’s Goodbye is still in print, but all the other books in the series are long gone. Why? I used to get parents and teachers in my library asking for the other books in the series. Particularly One of the Problems of Everett Anderson which discusses the incredibly difficult topic of what to do when you’re a kid and one of your friends at school is being abused at home. And after all, if you can find another book that covers the same topic with half the skill, all power to you. Until then, reprint these books. Re-illustrate them even, if you like. I wouldn’t mind, as long as the text was available again.

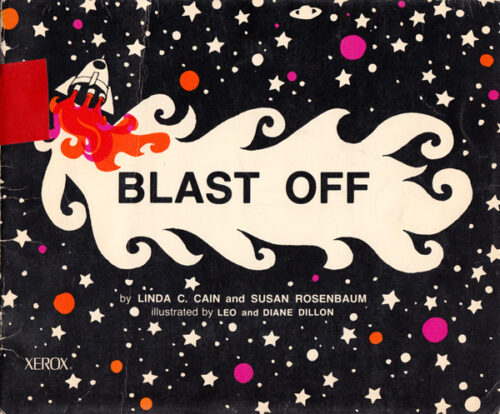

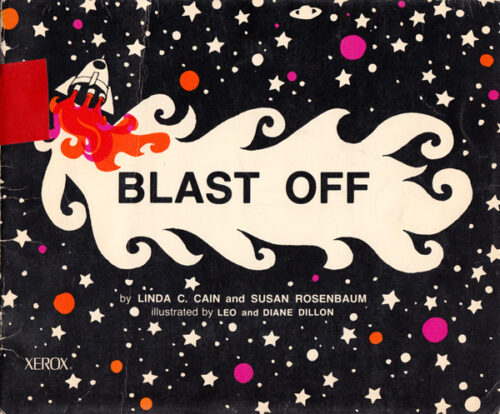

Blast Off by Linda C. Cain and Susan Rosenbaum,

ill. Leo and Diane Dillon

I’ve written about this one before and admittedly I haven’t read it myself. However, it looks beautiful and features an African-American girl dreaming of becoming an astronaut.

This is just to start. Your turn now. Which titles would you add to this list? Tell me and I’ll do my best to add them.

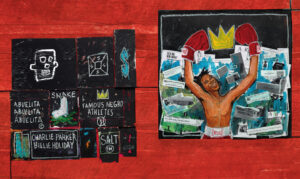

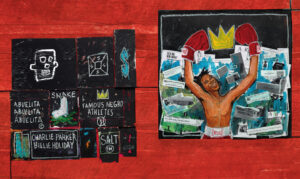

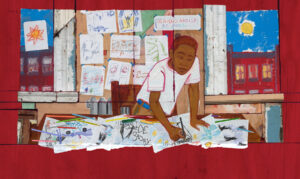

Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat

Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat

By Javaka Steptoe

Little, Brown & Co.

$17.99

ISBN: 978-0-316-21388-2

Ages 5 and up

On shelves October 25th

True Story: I’m working the children’s reference desk of the Children’s Room at 42nd Street of New York Public Library a couple years ago and a family walks in. They go off to read some books and eventually the younger son, I’d say around four years of age, approaches my desk. He walks right up to me, looks me dead in the eye, and says, “I want all your Javaka Steptoe books.” Essentially this child was a living embodiment of my greatest dream for mankind. I wish every single kid in America followed that little boy’s lead. Walk up to your nearest children’s librarian and insist on a full fledged heaping helping of Javaka. Why? Well aside from the fact that he’s essentially children’s book royalty (his father was the groundbreaking African-American picture book author/illustrator John Steptoe) he’s one of the most impressive / too-little-known artists working today. But that little boy knew him and if his latest picture book biography “Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat” is even half as good as I think it is, a whole host of children will follow suit. But don’t take my word for it. Take that four-year-old boy’s. That kid knew something good when he saw it.

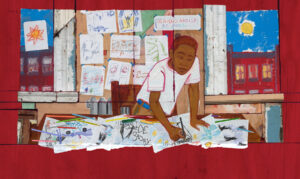

“Somewhere in Brooklyn, a little boy dreams of being a famous artist, not knowing that one day he will make himself a KING.” That boy is an artist already, though not famous yet. In his house he colors on anything and everything within reach. And the art he makes isn’t pretty. It’s, “sloppy, ugly, and sometimes weird, but somehow still BEAUTIFUL.” His mother encourages him, teaches him, and gives him an appreciation for all the art in the world. When he’s in a car accident, she’s the one who hands him Gray’s Anatomy to help him cope with what he doesn’t understand. Still, nothing can help him readily understand his own mother’s mental illness, particularly when she’s taken away to live where she can get help. All the same, that boy, Jean-Michel Basquiat, shows her his art, and with determination he grows up, moves to Manhattan, and starts his meteoric rise in the art scene. All this so that when, at long last, he’s at the top of his game, it’s his mother who sits on the throne at his art shows. Additional information about Basquiat appears at the back of the book alongside a key to the motifs in his work, an additional note from Steptoe himself on what Basquiat’s life and work can mean to young readers, and a Bibliography.

Javaka Steptoe apparently doesn’t like to make things easy for himself. If he wanted to, he could illustrate all the usual African-American subjects we see in books every year. Your Martin Luther Kings and Rosa Parks and George Washington Carvers. So what projects does he choose instead? Complicated heroes who led complicated lives. Artists. Jimi Hendrix and guys like that. Because for all that kids should, no, MUST know who Basquiat was, he was an adult with problems. When Steptoe illustrated Gary Golio’s bio of Hendrix (Jimi: Sounds Like a Rainbow) critics were universal in their praise. And like that book, Steptoe ends his story at the height of Basquiat’s fame. I’ve seen some folks comment that the ending here is “abrupt” and that’s not wrong. But it’s also a natural high, and a real time in the man’s life when he was really and truly happy. When presenting a subject like Basquiat to a young audience you zero in on the good, acknowledge the bad in some way (even if it’s afterwards in an Author’s Note), and do what you can to establish precisely why this person should be mentioned alongside those Martin Luther Kings, Rosa Parks, and George Washington Carvers.

Javaka Steptoe apparently doesn’t like to make things easy for himself. If he wanted to, he could illustrate all the usual African-American subjects we see in books every year. Your Martin Luther Kings and Rosa Parks and George Washington Carvers. So what projects does he choose instead? Complicated heroes who led complicated lives. Artists. Jimi Hendrix and guys like that. Because for all that kids should, no, MUST know who Basquiat was, he was an adult with problems. When Steptoe illustrated Gary Golio’s bio of Hendrix (Jimi: Sounds Like a Rainbow) critics were universal in their praise. And like that book, Steptoe ends his story at the height of Basquiat’s fame. I’ve seen some folks comment that the ending here is “abrupt” and that’s not wrong. But it’s also a natural high, and a real time in the man’s life when he was really and truly happy. When presenting a subject like Basquiat to a young audience you zero in on the good, acknowledge the bad in some way (even if it’s afterwards in an Author’s Note), and do what you can to establish precisely why this person should be mentioned alongside those Martin Luther Kings, Rosa Parks, and George Washington Carvers.

There’s this moment in the film Basquiat when David Bowie (playing Andy Warhol) looks at some of his own art and says off-handedly, “I just don’t know what’s good anymore.” I have days, looking at the art of picture books when I feel the same way. Happily, there wasn’t a minute, not a second, when I felt that way about Radiant Child. Now I’m going to let you in on a little secret: Do you know what one of the most difficult occupations to illustrate a picture book biography about is? Artist. Because right from the start the illustrator of the book is in a pickle. Are you going to try to replicate the art of this long dead artist? Are you going to grossly insert it into your own images, even if the book isn’t mixed media to begin with? Are you going to try to illustrate the story in that artist’s style alone, relegating images of their actual art to the backmatter? Steptoe addresses all this in his Note at the back of the book. As he says, “Instead of reproducing or including copies of real Basquiat paintings in this book, I chose to create my own interpretations of certain pieces and motifs.” To do this he raided Basquiat’s old haunts around NYC for discarded pieces of wood to paint on. The last time I saw this degree of attention paid to painting on wood in a children’s book was Paul O. Zelinsky’s work on Swamp Angel. In Steptoe’s case, his illustration choice works shockingly well. Look how he manages to give the reader a sense of perspective when he presents Picasso’s “Guernica” at an angle, rather than straight on. Look how the different pieces of wood, brought together, fit, sometimes including characters on the same piece to show their closeness, and sometimes painting them on separate pieces as a family is broken apart. And the remarkable thing is that for all that it’s technically “mixed-media”, after the initial jolt of the art found on the title page (a full wordless image of Basquiat as an adult surrounded by some of his own imagery) you’re all in. You might not even notice that even the borders surrounding these pictures are found wood as well.

The precise age when a child starts to feel that their art is “not good” anymore because it doesn’t look realistic or professional enough is relative. Generally it happens around nine or ten. A book like Radiant Child, however, is aimed at younger kids in the 6-9 year old range. This is good news. For one thing, looking at young Basquiat vs. older Basquiat, it’s possible to see how his art is both childlike and sophisticated all at once. A kid could look at what he’s doing in this book and think, “I could do that!” And in his text, Steptoe drills into the reader the fact that even a kid can be a serious artist. As he says, “In his house you can tell a serious ARTIST dwells.” No bones about it.

The precise age when a child starts to feel that their art is “not good” anymore because it doesn’t look realistic or professional enough is relative. Generally it happens around nine or ten. A book like Radiant Child, however, is aimed at younger kids in the 6-9 year old range. This is good news. For one thing, looking at young Basquiat vs. older Basquiat, it’s possible to see how his art is both childlike and sophisticated all at once. A kid could look at what he’s doing in this book and think, “I could do that!” And in his text, Steptoe drills into the reader the fact that even a kid can be a serious artist. As he says, “In his house you can tell a serious ARTIST dwells.” No bones about it.

How much can a single picture book bio do? Pick a good one apart and you’ll see all the different levels at work. Steptoe isn’t just interested in celebrating Basquiat the artist or encouraging kids to keep working on their art. He also notes at the back of the book that the story of Basquiat’s relationship with his mother, who suffered from mental illness, was very personal to him. And so, Basquiat’s mother remains an influence and an important part of his life throughout the text. You might worry, and with good reason, that the topic of mental illness is too large for a biography about someone else, particularly when that problem is not the focus of the book. How do you properly address such an adult problem (one that kids everywhere have to deal with all the time) while taking care to not draw too much attention away from the book’s real subject? Can that even be done? Sacrifices, one way or another, have to be made. In Radiant Child Steptoe’s solution is to show Jean-Michel within the lens of his art’s relationship to his mother. She talks to him about art, takes him to museums, and encourages him to keep creating. When he sees “Guernica”, it’s while he’s holding her hand. And because Steptoe has taken care to link art + mom, her absence is keenly felt when she’s gone. The book’s borders go a dull brown. Just that single line “His mother’s mind is not well” says it succinctly. Jean-Michel is confused. The kids reading the book might be confused. But the feeling of having a parent you are close to leave you . . . we can all relate to that, regardless of the reason. It’s just going to have a little more poignancy for those kids that have a familiarity with family members that suffer mental illnesses. Says Steptoe, maybe with this book those kids can, “use Basquiat’s story as a catalyst for conversation and healing.”

That’s a lot for a single picture book biography to take on. Yet I truly believe that Radiant Child is up to the task. It’s telling that in the years since I became a children’s librarian I’ve seen a number of Andy Warhol biographies and picture books for kids but the closest thing I ever saw to a Basquiat bio for children was Life Doesn’t Frighten Me as penned by Maya Angelou, illustrated by Jean-Michel. And that wasn’t even really a biography! For a household name, that’s a pretty shabby showing. But maybe it makes sense that only Steptoe could have brought him to proper life and to the attention of a young readership. In such a case as this, it takes an artist to display another artist. Had Basquiat chosen to create his own picture book autobiography, I don’t think he could have done a better job that what Radiant Child has accomplished here. Timely. Telling. Overdue.

On shelves October 25th.

Source: F&G sent from publisher for review.

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus

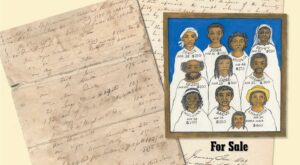

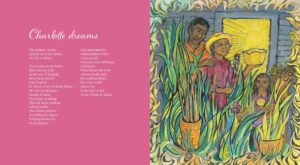

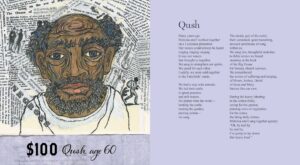

Freedom Over Me: Eleven slaves, their lives and dreams brought to life

Freedom Over Me: Eleven slaves, their lives and dreams brought to life

By Ashley Bryan

Atheneum (an imprint of Simon & Schuster)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-1481456906

Ages 9 and up

On shelves September 13th

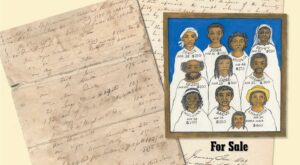

Who gives voice to the voiceless? What are your credentials when you do so? When I was a teen I used to go into antique stores and buy old family photographs from the turn of the century. It still seems odd to me that this is allowed. I’d find the people who looked the most interesting, like they had a story to tell, and I’d take them home with me. Then I’d write something about their story, though mostly I just liked to look at them. There is a strange comfort in looking at the faces of the fashionable dead. A little twinge of momento mori mixed with the knowledge that you yourself are young (possibly) and alive (probably). It’s easy to hypothesize about a life when you can see that person’s face and watch them in their middle class Sunday best. It is far more difficult when you have no face, a hint of a name, and/or maybe just an age. Add to this the idea that the people in question lived through a man made hell-on-earth. When author/illustrator/artist Ashley Bryan acquired a collection of slave-related documents from the 1820s to the 1860s he had in his hands a wealth of untold stories. And when he chose to give these people, swallowed by history, lives and dignity and peace, he did so as only he could. With the light and laughter and beauty that only he could find in the depths of uncommon pain. Freedom Over Me is a work of bravery and sense. A way of dealing with the unimaginable, allowing kids an understanding that there is a brain, heart, and soul behind every body, alive or dead, in human history.

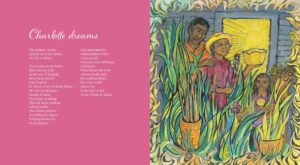

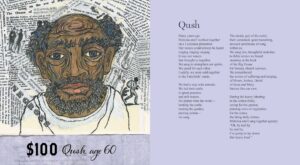

The date on the Fairchilds Appraisement is July 5, 1828. On it you will find a list of goods to be sold. Cows, hogs, cotton . . . and people. Eleven people, if we’re going to be precise (and we are). Most have names. One does not. Just names on a piece of paper almost 200-years-old. So Ashley Bryan, he takes those names and those people, and for the first time in centuries we get to meet them. Here is Athelia, a laundress who once carried the name Adero. On one page we hear about her life. On the next, her dreams. She remembers the village she grew up in, the stories, and the songs. And she is not alone in this. As we meet each person and learn what they do, we get a glimpse into their dreams. We hear their hopes. We wonder about their lives. We see them draw strength from one another. And in the end? The sale page sits there. The final words: “Administered to the best of our Judgment.”

I have often said, and I say it to this day, that if there were ever a Church of Ashley Bryan, every last person who has ever met him or heard him speak would be a member. There are only a few people on this great green Earth that radiant actual uncut goodness right through their very pores. Mr. Bryan is one of those few, so when I asked at the beginning of this review what the credentials are for giving voice to the voiceless, check off that box. There are other reasons to trust him, though. A project of this sort requires a certain level of respect for the deceased. To attain that, and this may seem obvious, the author has to care. Read enough books written for kids and you get a very clear sense of those books written by folks who do not care vs. folks that do. Even then, caring’s not really enough. The writing needs to be up to speed and the art needs to be on board. And for this particular project, Ashley Bryan had a stiffer task at hand. Okay. You’ve given them full names and backgrounds and histories. What else do they need? Bryan gives these people something intangible. He gives them dreams. It’s right there in the subtitle, actually: “Eleven slaves, their lives and dreams brought to life.”

I have often said, and I say it to this day, that if there were ever a Church of Ashley Bryan, every last person who has ever met him or heard him speak would be a member. There are only a few people on this great green Earth that radiant actual uncut goodness right through their very pores. Mr. Bryan is one of those few, so when I asked at the beginning of this review what the credentials are for giving voice to the voiceless, check off that box. There are other reasons to trust him, though. A project of this sort requires a certain level of respect for the deceased. To attain that, and this may seem obvious, the author has to care. Read enough books written for kids and you get a very clear sense of those books written by folks who do not care vs. folks that do. Even then, caring’s not really enough. The writing needs to be up to speed and the art needs to be on board. And for this particular project, Ashley Bryan had a stiffer task at hand. Okay. You’ve given them full names and backgrounds and histories. What else do they need? Bryan gives these people something intangible. He gives them dreams. It’s right there in the subtitle, actually: “Eleven slaves, their lives and dreams brought to life.”

And so the book is a work of fiction. There is no amount of research that could discover Bacus or Peggy or Dora’s true tales. So when we say that Bryan is giving these people their lives back, we acknowledge that the lives he’s giving them aren’t the exact lives they led. And so we know that each person is a representative above and beyond the names on that page. Hence the occupations. Betty is every gardener. Stephen every architect. Dora every child that was born to a state of slavery and labored under it, perhaps their whole lives. And there is very little backmatter included in this book. Bryan shows the primary documents alongside a transcription of the sales. There is also an Author’s Note. Beyond that, you bring to the book what you already know about slavery, making this a title for a slightly older child readership. Bryan isn’t going to spend these pages telling you every daily injustice of slavery. Kids walk in with that knowledge already in place. What they need now is some humanity.

Has Mr. Bryan ever done anything with slavery before? I was curious. I’ve watched Mr. Bryan’s books over the years and they are always interesting. He’s done spirituals as cut paper masterpieces. He’s originated folktales as lively and quick as their inspirational forbears. He makes puppets out of found objects that carry with them a feeling not just of dignity, but pride. But has he ever directly done a book that references slavery? So I examined his entire repertoire, from the moment he illustrated Black Boy by Richard Wright to Susan Cooper’s Jethro and the Jumbie to Ashley Bryan’s African Folktales, Uh-Huh and beyond. His interest in Africa and song and poetry knows no bounds, but never has he engaged so directly with slavery itself.

Has Mr. Bryan ever done anything with slavery before? I was curious. I’ve watched Mr. Bryan’s books over the years and they are always interesting. He’s done spirituals as cut paper masterpieces. He’s originated folktales as lively and quick as their inspirational forbears. He makes puppets out of found objects that carry with them a feeling not just of dignity, but pride. But has he ever directly done a book that references slavery? So I examined his entire repertoire, from the moment he illustrated Black Boy by Richard Wright to Susan Cooper’s Jethro and the Jumbie to Ashley Bryan’s African Folktales, Uh-Huh and beyond. His interest in Africa and song and poetry knows no bounds, but never has he engaged so directly with slavery itself.

Could this have been done as anything but poetry? Or would you even call each written section poetry? I would, but I’ll be interested to see where libraries decide to shelve the book. Do you classify it as poetry or in the history section under slavery? Maybe, for all that it seems to be the size and shape of a picture book, you’d put it in your fiction collection. Wherever you put it, I am reminded, as I read this book, of Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! where every lord and peasant gets a monologue from their point of view. Freedom Over Me bears more than a passing similarity to Good Masters. In both cases we have short monologues any kid could read aloud in class or on their own. They are informed by research, and their scant number of words speak to a time we’ll never really know or understand fully. And how easy it would be to turn this book into a stage play. I can see it so easily. Imagine if you turned the Author’s Note into the first monologue and Ashley Bryan his own character (behold the 10-year-old dressed up as him, mustache and all). Since the title of the book comes from the spiritual “Oh, Freedom!” you could either have the kids sing it or play it in the background. And for the ending? A kid playing the lawyer or possibly Mrs. Fairchilds or even Ashley comes out and reads the statement at the end with each person and their price and the kids step forward holding some object that defines them (clothing sewn, books read, paintings, etc.). It’s almost too easy.

The style of the art was also interesting to me. Pen, ink, and watercolors are all Mr. Bryan (who is ninety-two years of age, as of this review) needs to render his people alive. I’ve see him indulge in a range of artistic mediums over the years. In this book, he begins with an image of the estate, an image of the slaves on that estate, and then portraits and renderings of each person, at rest or active in some way. “Peggy” is one of the first women featured, and for her portrait Ashley gives her face whorls and lines, not dissimilar to those you’d find in wood. This technique is repeated, to varying degrees, with the rest of the people in the book. First the portrait. Then an image of what they do in their daily lives or dreams. The degree of detail in each of these portraits changes a bit. Peggy, for example, is one of the most striking. The colors of her skin, and the care and attention with which each line in her face is painted, make it clear why she was selected to be first. I would have loved the other portraits to contain this level of detail, but the artist is not as consistent in this regard. Charlotte and Dora, for example, are practically line-less, a conscious choice, but a kind of pity since Peggy’s portrait sets you up to think that they’ll all look as richly detailed and textured as she.

The style of the art was also interesting to me. Pen, ink, and watercolors are all Mr. Bryan (who is ninety-two years of age, as of this review) needs to render his people alive. I’ve see him indulge in a range of artistic mediums over the years. In this book, he begins with an image of the estate, an image of the slaves on that estate, and then portraits and renderings of each person, at rest or active in some way. “Peggy” is one of the first women featured, and for her portrait Ashley gives her face whorls and lines, not dissimilar to those you’d find in wood. This technique is repeated, to varying degrees, with the rest of the people in the book. First the portrait. Then an image of what they do in their daily lives or dreams. The degree of detail in each of these portraits changes a bit. Peggy, for example, is one of the most striking. The colors of her skin, and the care and attention with which each line in her face is painted, make it clear why she was selected to be first. I would have loved the other portraits to contain this level of detail, but the artist is not as consistent in this regard. Charlotte and Dora, for example, are practically line-less, a conscious choice, but a kind of pity since Peggy’s portrait sets you up to think that they’ll all look as richly detailed and textured as she.

Those old photographs I once collected may well be the only record those people left of themselves on this earth, aside from a name in a family tree and perhaps on a headstone somewhere. So much time has passed since July 5, 1828 that it is impossible to say whether or not the names on Ashley’s acquired Appraisement are remembered by their descendants. Do families still talk about Jane or Qush? Is this piece of paper the only part of them that remains in the world? It may not have been the lives they led, but Ashley Bryan does everything within his own personal capacity to keep these names and these people alive, if just for a little longer. Along the way he makes it clear to kids that slaves weren’t simply an unfortunate mass of bodies. They were architects and artists and musicians. They were good and bad and human just like the rest of us. Terry Pratchett once wrote that sin is when people treat other people as objects. Ashley treats people as people. And times being what they are, here in the 21st century I’d say that’s a pretty valuable lesson to be teaching our kids today.

On shelves September 13th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus

Misc: Interested in the other books Mr. Bryan has written or illustrated over the course of his illustrious career? See the full list on his website here.

On January 19th, Claire Fallon, a Books and Culture Writer at The Huffington Post, wrote an article called 13 Honest Books About Slavery Young People Should Actually Read. The piece was a response to the news about Scholastic pulling the publication of A Birthday Cake for George Washington and got shared hither and thither and yon (mostly yon). It’s not a bad list by any means, but looking at it I was struck by how old the titles were. Nightjohn is from 1993. The Glory Field from 1994. Even the most recent title on the list, Never Forgotten by Patricia McKissack, originally dates to 2011.

I love older books, but there’s nothing wrong with including recent titles as well. With that in mind, here is a companion list of thirteen books about slavery for young people published in the last five years.

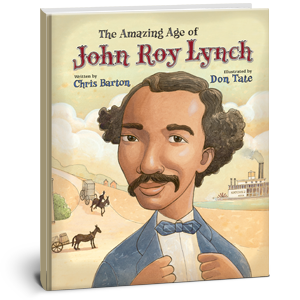

The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch By Chris Barton, illustrated by Don Tate

Best dang book about Reconstruction you’ll ever read to a kid. I find that when I try to sell this book to adults their eyes glaze over at the word “Reconstruction”. Kids don’t know anything about it so they’re a bit less prejudiced in that respect. A great story about a great man. As Barton puts it, “It’s the story of a guy who in ten years went from teenage field slave to U.S. Congressman.”

Best dang book about Reconstruction you’ll ever read to a kid. I find that when I try to sell this book to adults their eyes glaze over at the word “Reconstruction”. Kids don’t know anything about it so they’re a bit less prejudiced in that respect. A great story about a great man. As Barton puts it, “It’s the story of a guy who in ten years went from teenage field slave to U.S. Congressman.”

Jefferson’s Sons by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley

Long before she’d win a Newbery Honor for The War That Saved My Life, Ms. Bradley was earning my respect with a book that dared to delve into the lives of Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved children. It’s an issue complicated enough for adult readers, but Baker managed to make it understandable to a middle grade audience. I thought she’d get some award recognition for her efforts. Not that time around, but the awards would certainly get her in the end.

Words Set Me Free: The Story of Young Frederick Douglass by Lesa Cline-Ransome, illustrated by James E. Ransome

Lesa and James are a husband and wife team that just keep on producing great book after great book to too little fanfare. Their take on Douglass’s life comes after James did meticulous historical research to get the clothing and dress of the time period exactly right. A very well done bio of a famous figure in his youth.

Africa Is My Home: A Child of the Amistad by Monica Edinger, illustrated by Robert Byrd

One of those books that should really be better known. You may think you know the story of The Amistad but boy howdy you’d be wrong. Monica’s book follows the true story of Magulu, one of the children taken on the boat, and it is just one of the best pieces of writing and research on the topic you will find. Plus the story is engrossing. That doesn’t hurt.

Underground: Finding the Light to Freedom by Shane W. Evans

As you read the story, pay close attention to what’s going on in the art. Though it’s not obvious, there’s a subplot about one of the pregnant slaves running away and the baby she gives birth to in the middle of her escape.

I Lay My Stitches Down: Poems of American Slavery by Cynthia Grady, illustrated by Michele Wood

Not many books of poetry out there about slavery these days. Make sure you pull out this book not just for Black History Month but in April for Poetry Month as well.

The Underground Abductor by Nathan Hale

If you haven’t read this by now then you are seriously missing out. Absolutely, without a doubt, a nail-biting tale and all true true true. Again, I thought I knew Harriet Tubman’s life. I could not have been more wrong. If you read no other book on this list, read this one.

All Different Now: Juneteenth, the First Day of Freedom by Angela Johnson, illustrated by E.B. Lewis

When I lived in New York I lived in Harlem. Each and every year on Juneteenth there would be a great big street fair in celebration going down 116th Street. A friend of mine visited one Juneteenth and had never heard of the celebration before. Can you think of a better reason for Johnson and Lewis’s book to gain a little more attention?

Heart and Soul: The Story of America and African Americans

by Kadir Nelson

Since this book encompasses a great deal of African-American history, not just slavery, I wondered if I should include it here. But then looking back at it and remembering how well Nelson encapsulates everything from the tale of one of George Washington’s slaves to the free men who fought for the Union side during the Civil War . . . well, it would be ridiculous not to include it.

Hand in Hand: Ten Black Men Who Changed America by Andrea Davis Pinkney, illustrated by J. Brian Pinkney

Again, not including this book on this list would leave a gap a mile wide. Andrea Davis Pinkey, let us remember, is a killer writer. This book was released in a rather silent, sly way. A lot of year end Best Of lists missed it. Make sure you don’t miss it yourself. Some of the biographies here are the best you’ll ever find for a young audience.

The Other Side of Free by Krista Russell

Remember, you must never ever judge a book by its cover? It applies here. I described the book in my review this way: “We’ve all heard of how slaves would escape to the North when they wished to escape for good. But travel a bit farther back in time to the early 18th century and the tale is a little different. At that point in history slaves didn’t flee north but south to Spain’s territories. There, the Spanish king promised freedom for those slaves that swore fidelity to the Spanish crown and fought on his behalf against the English. 13-year-old Jem is one of those escaped slaves, but his life at Fort Mose is hardly stimulating. Kept under the yoke of a hard woman named Phaedra, Jem longs to fight for the king and to join in the battles. But when at last the fighting comes to him, it isn’t at all what he thought it would be.”

Brick by Brick by Charles R. Smith Jr., illustrated by Floyd Cooper

The first book I read for kids that really delved deeply into the fact that the White House was built on the backs of slaves. Smith and Cooper make for a winning team.

Freedom in Congo Square by Carole Boston Weatherford, illustrated by R. Gregory Christie

Take a good long look at this 2016 release. You’re going to be hearing a lot more about it in the months to come.

Seeking out some recent titles about African-Americans, not just slaves, in children’s literature? Check out last year’s African-American Experience Children’s Literary Reference Guide (2010-2015). I’ll be updating it to be 2011-2016 in February.

And finally, in related news, the Delaware House recently passed an official apology for slavery. Thanks to @debraj112 for the alert.

We’re in the thick of the month of February now and recently I ran into an interesting problem. It being Black History Month and all I was looking to create a list of Black Experience children’s books for my librarians to pull from for displays and purchasing and such. So I trolled about online looking for a recent list of titles. Don’t get me wrong – I love books like Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry, but in spite of the relatively small publishing numbers we really have had some wonderful books come out in the last few years. So I looked about and looked about and found almost nothing. If it’s not an award winner or 20+ years old, it’s hard to find lists of recent books.

We’re in the thick of the month of February now and recently I ran into an interesting problem. It being Black History Month and all I was looking to create a list of Black Experience children’s books for my librarians to pull from for displays and purchasing and such. So I trolled about online looking for a recent list of titles. Don’t get me wrong – I love books like Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry, but in spite of the relatively small publishing numbers we really have had some wonderful books come out in the last few years. So I looked about and looked about and found almost nothing. If it’s not an award winner or 20+ years old, it’s hard to find lists of recent books.

So I created my own. I wanted a list of titles from the last five years. Moreover, I didn’t want to limit it to just historical books. So in the end what I came up with was an African-American Experience Literary Reference Guide. This is by NO MEANS an all-encompassing list. It’s just some of the recent things I’ve liked and enjoyed and that we all have a need for. Please note that all listed titles are currently in print. Also, they are organized by where they are cataloged in the New York Public Library system.

Enjoy and feel free to add your own in-print titles out in the last five years in the comments.

Picture Books

Knock Knock: My Dad’s Dream for Me by Daniel Beaty, illustrated by Bryan Collier, ISBN: 9780316209175

Knock Knock: My Dad’s Dream for Me by Daniel Beaty, illustrated by Bryan Collier, ISBN: 9780316209175

Lucky Beans by Becky Birtha, illustrated Nicole Tadgell, ISBN: 9780807547823

Beautiful Moon: A Child’s Prayer by Tonya Bolden illustrated by Eric Velasquez, ISBN: 9781419707926

My Cold Plum Lemon Pie Bluesy Mood by Tameka Fryer Brown, illustrated by Shane W. Evans, ISBN: 9780670012855

Can’t Scare Me! by Ashley Bryan, ISBN: 9781442476578

Duke Ellington’s Nutcracker Suite by Anna Harwell Celenza, illustrated by Don Tate, ISBN: 9781570917004

Max and the Tag-Along Moon by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9780399233425

Firebird by Misty Copeland, illustrated by Christopher Myers, ISBN: 9780399166150

A Dance Like Starlight: One Ballerina’s Dream by Kristy Dempsey, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9780399252846

Chocolate Me! by Taye Diggs, illustrated by Shane W. Evans, ISBN: 9780312603267

Underground by Shane W. Evans, ISBN: 9781250056757

We March by Shane W. Evans, ISBN: 9781596435391

The Hula Hoopin’ Queen by Thelma Lynne Godin, illustrated Vanessa Brantley-Newton, ISBN: 9781600608469

The Hula Hoopin’ Queen by Thelma Lynne Godin, illustrated Vanessa Brantley-Newton, ISBN: 9781600608469

My Hands Sing the Blues: Romare Bearden’s Childhood Journey by Jeanne Walker Harvey, illustrated by Elizabeth Zunon, ISBN: 9780761458104

My Friend Maya Loves to Dance by Cheryl Willis Hudson, illustrated by Eric Velasquez, ISBN: 9780810983281

Lullaby (For a Black Mother) by Langston Hughes, illustrated Sean Qualls, ISBN: 9780547362656

Goal! by Mina Javaherbin, illustrated by A.G. Ford, ISBN: 9780763658229

All Different Now: Juneteenth, the First Day of Freedom by Angela Johnson, illustrated by E.B. Lewis, ISBN: 9780689873768

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind by William Kamkwamba and Bryan Mealer, illustrated by Elizabeth Zunon, ISBN: 9780803735118

We Shall Overcome: The Story of a Song by Debbie Levy, illustrated by Vanessa Brantley-Newton, ISBN: 9781423119548

Hope’s Gift by Kelly Starling Lyons, illustrated Don Tate, ISBN: 9780399160011

Tea Cakes for Tosh by Kelly Starling Lyons, illustrated by E.B. Lewis, ISBN: 9780399252136

Ellen’s Broom by Kelly Starling Lyons, illustrated by Daniel Minter, ISBN: 9780399250033

Every Little Thing: Based on the Song ‘Three Little Birds’ by Bob Marley and Cedella Marley, illustrated by Vanessa Brantley-Newton, ISBN: 9781452106977

Every Little Thing: Based on the Song ‘Three Little Birds’ by Bob Marley and Cedella Marley, illustrated by Vanessa Brantley-Newton, ISBN: 9781452106977

One Love by Cedella Marley, Vanessa Brantley-Newton, ISBN: 9781452102245

These Hands by Margaret H. Mason, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9780547215662

Busing Brewster by Richard Michelson, illustrated by R.G. Roth, ISBN: 9780375833342

H.O.R.S.E.: A Game of Basketball and Imagination by Christopher Myers, ISBN: 9781606842188

My Brother Charlie by Holly Robinson Peete & Ryan Elizabeth Peete, illustrated by Shane W. Evans, ISBN: 9780545094665

Belle, the Last Mule at Gee’s Bend: A Civil Rights Story by Calvin Alexander Ramsey, Bettye Stroud, Bettye, and John Holyfield, ISBN: 9780763640583

Ruth and the Green Book by Calvin Alexander Ramsey, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9780761352556

Under the Same Sun by Sharon Robinson, illustrated by A.G. Ford, ISBN: 9780545166720

Me and Momma and Big John by Mara Rockliff, illustrated by William Low, ISBN: 9780763643591

Little Melba and Her Big Trombone by Katheryn Russell-Brown, illustrated by Frank Morrison, ISBN: 9781600608988

I Got the Rhythm by Connie Schofield-Morrison, illustrated by Frank Morrison, ISBN: 9781619631786

In the Land of Milk and Honey by Joyce Carol Thomas, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9780060253837

In the Land of Milk and Honey by Joyce Carol Thomas, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9780060253837

As Fast As Words Could Fly by Pamela M. Tuck, illustrated by Eric Velasquez, ISBN: 9781600603488

Grandma’s Gift by Eric Velasquez, ISBN: 9780802720825

Freedom Song: The Story of Henry “Box” Brown by Sally M. Walker, illustrated by Sean Qualls, ISBN: 9780060583101

Sugar Hill: Harlem’s Historic Neighborhood by Carole Boston Weatherford, illustrated by R. Gregory Christie, ISBN: 9780807576502

A Beach Tail by Karen Lynn Williams, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9781590787120

Jazz Age Josephine by Jonah Winter, illustrated by Marjorie Priceman, ISBN: 9781416961239

This Is the Rope: A Story from the Great Migration by Jacqueline Woodson, Jacqueline, illustrated by James Ransome, ISBN: 9780399239861

Pecan Pie Baby by Jacqueline Woodson, illustrated by Sophie Blackall, ISBN: 9780399239878

Early Chapter Books

Dog Days by Karen English, illustrated by Laura Freeman, ISBN: 9780547970448

Dog Days by Karen English, illustrated by Laura Freeman, ISBN: 9780547970448

Election Madness by Karen English, illustrated by Laura Freeman, ISBN: 9780547850719

Skateboard Party by Karen English, illustrated by Laura Freeman, ISBN: 9780544283060

Birthday Blues by Karen English, illustrated by Laura Freeman, ISBN: 9780547248936

Nikki and Deja by Karen English, illustrated by Laura Freeman, ISBN: 9780547133621

Substitute Trouble by Karen English, illustrated by Laura Freeman, ISBN: 9780544223882

Keena Ford and the Secret Journal Mix-Up by Melissa Thomson, illustrated by Frank Morrison, ISBN: 9780142419373

Keena Ford and the Field Trip Mix-Up by Melissa Thomson, illustrated by Frank Morrison, ISBN: 9780142415726

EllRay Jakes and the Beanstalk by Sally Warner, illustrated by Brian Biggs, ISBN: 9780670784998

EllRay Jakes the Dragon Slayer! by Sally Warner, illustrated by Brian Biggs, ISBN: 9780670784974

EllRay Jakes Walks the Plank! by Sally Warner, illustrated by Jamie Harper, ISBN: 9780670063062

EllRay Jakes Is a Rock Star by Sally Warner, illustrated by Jamie Harper, ISBN: 9780670011582

EllRay Jakes is Not a Chicken! by Sally Warner, illustrated by Jamie Harper, ISBN: 9780670062430

Ellray Jakes Rocks the Holidays! by Sally Warner, illustrated by Brian Biggs, ISBN: 9780451469090

Ellray Jakes Is Magic! by Sally Warner, illustrated by Brian Biggs, ISBN: 9780670785001

Middle Grade Fiction

Sasquatch in the Paint by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Raymond Obstfeld, ISBN: 9781423178705

Sasquatch in the Paint by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Raymond Obstfeld, ISBN: 9781423178705

The Crossover by Kwame Alexander, ISBN: 9780544107717

How Lamar’s Bad Prank Won a Bubba-Sized Trophy by Crystal Allen, ISBN: 9780061992728

Hold Fast by Blue Balliett, ISBN: 9780545299886

The Zero Degree Zombie Zone by Patrik Henry Bass, illustrated by Jerry Craft, ISBN: 9780545132107

Zora and Me by Victoria Bond, Victoria and T.R. Simon, ISBN: 9780763643003

Kinda Like Brothers by Coe Booth, ISBN: 9780545224963

Serafina’s Promise by Ann E. Burg, ISBN: 9780545535649

Riding on Duke’s Train by Mick Carlon, ISBN: 9781935248064

Etched in Clay: The Life of Dave, Enslaved Potter and Poet by Andrea Cheng, ISBN: 9781600604515

The Madman of Piney Woods by Christopher Paul Curtis, ISBN: 9780545156646

Africa Is My Home: A Child of the Amistad by Monica Edinger, illustrated by Robert Byrd, ISBN: 9780763650384

Unstoppable Octobia May by Sharon Flake, ISBN: 9780545609609

Winter Sky by Patricia Reilly Giff, ISBN: 9780375838927

The Perfect Place by Teresa E. Harris, ISBN: 9780547255194

Buddy by M.H. Herlong, ISBN: 9780142425442

The Great Greene Heist by Varian Johnson, ISBN: 9780545525527

The Great Greene Heist by Varian Johnson, ISBN: 9780545525527

Upside Down in the Middle of Nowhere by Julie T. Lamana, ISBN: 9781452124568

Nightingale’s Nest by Nikki Loftin, ISBN: 9781595145468

True Legend by Mike Lupica, ISBN: 9780399252273

The Sittin’ Up by Sheila P. Moses, ISBN: 9780399257230

Ghetto Cowboy by G. Neri, illustrated by Jesse Joshua Watson, ISBN: 9780763649227

Ninth Ward by Jewell Parker Rhodes, ISBN: 9780316043083

8th Grade Superzero by Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich, ISBN: 9780545097253

The Other Side of Free by Krista Russell, ISBN: 9781561457106

Eddie Red Undercover: Mystery on Museum Mile by Marcia Wells, illustrated by Marcos Calo, ISBN: 9780544238336

One Crazy Summer by Rita Williams-Garcia, ISBN: 9780060760885

P.S. Be Eleven by Rita Williams-Garcia, ISBN: 9780061938627

The Blossoming Universe of Violet Diamond by Brenda Woods, ISBN: 9780399257148

Crow by Barbara Wright, ISBN: 9780375873676

Non-Fiction

What Color Is My World?: The Lost History of African-American Inventors by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Raymond Obstfeld, and Ben Boos, illustrated by A.G. Ford, ISBN: 9780763645649

A Splash of Red: The Life and Art of Horace Pippin by Jen Bryant, illustrated by Melissa Sweet, ISBN: 9780375867125

A Splash of Red: The Life and Art of Horace Pippin by Jen Bryant, illustrated by Melissa Sweet, ISBN: 9780375867125

The Cart That Carried Martin by Eve Bunting, illustrated by Don Tate, ISBN: 9781580893879

Words Set Me Free: The Story of Young Frederick Douglass by Lesa Cline-Ransome, illustrated by James E. Ransome, ISBN: 9781416959038

Ballerina Dreams: From Orphan to Ballerina by Michaela Deprince, Michaela and Elaine Deprince, illustrated by Frank Morrison, ISBN: 9780385755160

Spirit Seeker: John Coltrane’s Musical Journey by Gary Golio, illustrated by Rudy Gutierrez, ISBN: 9780547239941

Jimi: Sounds Like a Rainbow: A Story of the Young Jimi Hendrix by Gary Golio, illustrated by Javaka Steptoe, ISBN: 9780618852796

I Lay My Stitches Down: Poems of American Slavery by Cynthia Grady, illustrated by Michele Wood, ISBN: 9780802853868

The Great Migration: Journey to the North by Eloise Greenfield, illustrated by Jan Spivey Gilchrist, ISBN: 9780061259210

When the Beat Was Born: DJ Kool Herc and the Creation of Hip Hop by Laban Carrick Hill, illustrated by Theodore Taylor III, ISBN: 9781596435407

Dave the Potter: Artist, Poet, Slave by Laban Carrick Hill, illustrated by Bryan Collier, ISBN: 9780316107310

I, Too, Am America by Langston Hughes, illustrated by Bryan Collier, ISBN: 9781442420083

The Girl from the Tar Paper School: Barbara Rose Johns and the Advent of the Civil Rights Movement by Teri Kanefield, ISBN: 9781419707964

Queen of the Track: Alice Coachman: Olympic High-Jump Champion by Heather Lang, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9781590788509

We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March by Cynthia Levinson, ISBN: 9781561456277

We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March by Cynthia Levinson, ISBN: 9781561456277

When Thunder Comes: Poems for Civil Rights Leaders by J. Patrick Lewis, illustrated by Various, ISBN: 9781452101194

Touch the Sky: Alice Coachman, Olympic High Jumper by Ann Malaspina, illustrated by Eric Velasquez, ISBN: 9780807580356

Farmer Will Allen and the Growing Table by Jacqueline Briggs Martin and Will Allen, illustrated by Eric-Shabazz Larkin, ISBN: 9780983661535

Nelson Mandela by Kadir Nelson, ISBN: 9780061783746

Heart and Soul: The Story of America and African Americans

by Kadir Nelson, ISBN: 9780061730740

Skit-Scat Raggedy Cat: Ella Fitzgerald by Roxane Orgill, illustrated by Sean Qualls, ISBN: 9780763664596

Martin & Mahalia: His Words – Her Song by Andrea Davis Pinkney, Andrea Davis, illustrated by J. Brian Pinkney, ISBN: 9780316070133

Hand in Hand: Ten Black Men Who Changed America by Andrea Davis Pinkney, illustrated by J. Brian Pinkney, ISBN: 9781423142577

Sit-In: How Four Friends Stood Up by Sitting Down by Andrea Davis Pinkney, illustrated by J. Brian Pinkney, ISBN: 9780316070164

Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker by Patricia Hruby Powell, illustrated by Christian Robinson, ISBN: 9781452103143

Jackie Robinson: American Hero by Sharon Robinson, ISBN: 9780545569156

Something to Prove: The Great Satchel Paige Vs. Rookie Joe Dimaggio by Robert Skead, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9780761366195

Brick by Brick by Charles R. Smith Jr., illustrated by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9780061920820

Brick by Brick by Charles R. Smith Jr., illustrated by Floyd Cooper, ISBN: 9780061920820

Stars in the Shadows: The Negro League All-Star Game of 1934

by Charles R. Smith Jr., illustrated by Frank Morrison, ISBN: 9780689866388

Black Jack: The Ballad of Jack Johnson by Charles R. Smith Jr., illustrated by Shane W. Evans, ISBN: 9781596434738

Courage Has No Color: The True Story of the Triple Nickels: America’s First Black Paratroopers by Tanya Lee Stone, ISBN: 9780763651176

It Jes’ Happened: When Bill Traylor Started to Draw by Don Tate, illustrated by R. Gregory Christie, ISBN: 9781600602603

She Loved Baseball: The Effa Manley Story by Audrey Vernick, illustrated by Don Tate, ISBN: 9780061349201

My Uncle Martin’s Words for America: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Niece Tells How He Made a Difference by Angela Farris Watkins, illustrated by Eric Velasquez, ISBN: 9781419700224

My Uncle Martin’s Big Heart by Angela Farris Watkins, Angela illustrated by Eric Velasquez, ISBN: 9780810989757

Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson, ISBN: 9780399252518

Perhaps not a familiar classic, but a book that I’d love to see back in print is Joyce Hansen’s The Captive, a middle grade work of historical fiction that starts a story about slavery in Africa, beautiful researched and told, I think. I use it with my 4th graders and snap up as many used copies as I can find via amazon. The cover of the Apple Paper is pretty dated but my students like it nonetheless. The main character is based on two real people: Olaudah Equiano and Paul Cuffee.

Excellent. I thought about delving into middle grade but all I could come up with was Andre Norton’s LAVENDER GREEN MAGIC which is now available in ebook form through Open Road Media.

One of my favorite books growing up was Mary Jane, by Dorothy Sterling. Now that I think about it, though, I have no idea if the author was black or white.

Don’t You Remember written by Lucille Clifton and illustrated by Evaline Ness. This was my favorite book for a long time. Every time my parents took me to the library I had to check out this book.

Hah! You’ve already included Blast Off! And here I was all ready to add it onto the list . . .

Here’s another SF book though : Cosmo and the Robot by Brian Pinkney Just the story of a kid and his robot on Mars . . .

“The House of Dies Drear” by Virginia Hamilton was great–about an African American 13-year-old whose family moves into a house that was an Underground Railroad stop, that is said to be haunted by two skaves who ran away and were killed. It’s a really good mystery, and good history, too!

Happily that book is still in print. I came to it as a kid through the movie first. Oh yes. There was a movie. And that guy emerging out of the ground like the devil himself scared the bejeezus out of me.

Brian Pinkney’s “Hush, Little Baby” – I want this book back in print so badly! I also long for “Snow on Snow on Snow,” illustrated by African-American artist Synthia St. James. While it doesn’t exactly fit your author criteria, I really want “I’m Your Peanut Butter Big Brother” by Selina Alko back in print as well. We need this imprint!

Hush, Little Baby is out of print?!? Okay, so now I’m really mad. That is a travesty!

I love “Snow on snow on snow” . I read it in many story times over years — in Florida.

Curiously watching the suggested titles for possible new material at Purple House!

Yes, Blast Off! needs to be reprinted right now. Publication of Blast Off! + 19 years = Mae Jemison. Coincidence? Maybe not… It is at least available digitally through Open Library: https://openlibrary.org/works/OL16033950W/Blast_off

It is at least available digitally through Open Library: https://openlibrary.org/works/OL16033950W/Blast_off

Two books by Jeannette Caines, Just Us Women, and I Need a Lunchbox.

Let me clarify. These titles are available as paperbacks, so they aren’t technically out of print, but I would very much like to see them back as hardcovers.

That’s one of my favorites, too. Such a lovely book.

Hi Betsy,

Our assistant editor, Raven Neely, brought your recent blog post to my attention so I’m writing to respond to your concern over the lack of characters of color in children’s literature. In citing Professor Thomas, you pointed out disappearing literature that celebrates the Black plight and stated, “Yet even in the era of We Need Diverse Books, not a single publisher has ever created an imprint specifically designed to reprint classic and older multicultural children’s literature. Correct me if I’m wrong about this.”

If I may, I would like to respond to your challenge. Although, it is true that we haven’t created a specific imprint to reprint these works, August House is constantly seeking exceptional multicultural books, where the rights have reverted back to the author. As you know, we are a relatively small, independent publisher of folktales and resource books (approximately 250 active titles), however, in recent years, we have acquired the rights and brought a number of award winning, multicultural out-of- print, folktale titles back to life including: Pickin’ Peas, by Margaret Read MacDonald and illustrated by Pat Cummings, A Natural Man: The True Story of John Henry, by Steve Sanfield and Peter Thornton and Broken Tusk: Stories of the Hindu God Ganesha, by Uma Krishnaswami. As you might imagine, at times, it can be challenging to identify when the rights have reverted back to the author and it can be challenging to negotiate the intellectual property issues but there are many timeless books that deserve to be enjoyed by a new generation of children. These three titles are representative of our effort to locate and publish similar multicultural titles.

We share your interest in continuing to re-introduce classic literature to the market and we share this passion with you. For the record, we are actively engaged in identifying these opportunities and we would love to hear from you, as well as, other librarians or anyone else who can connect us with other deserving multicultural properties that have gone out of print.

All the best,

Steve

August House

Marvelous! This is precisely what I hoped to hear when I wrote the post. Thank you for bringing August House to my attention. I’ll be sure to cite you in the future when this discussion comes up again (as it is certainly wont to do). Much appreciated.

Thank you, we really appreciate your insightful comments and observations about children’s literacy.