My novel is growing chapter by chapter.

Getting a chapter done.

Here’s a look at a typical process for writing a chapter of a book.

First, I look at the plot synopsis that I have already written. It tells me the bare bones of what happens in this chapter, but often few specifics. I have to decide setting, characters present, the scenes that will Show-Don’t-Tell the plot and get a certain tone or voice in my head.

Setting is often the first thing for me. I want the story to be grounded in a specific place. Not just “my house.” It needs to be the kitchen right after Mom has just burned toast. A specific place and a specific time. This includes time of year and for a historical or futuristic novel, might include the year and the culture around that year. Just deciding this helps ground me in where the scene takes place and what sorts of actions make sense here. In the smelly kitchen, it’s unlikely to find characters dressed up in evening clothes or pirates with treasure.

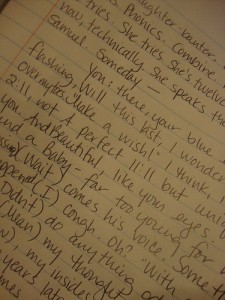

Next, I decide on a goal for a scene. Often by this time, I am writing notes to myself. I find that 750words.com exercises to be helping in sorting out what is important in this section of the story. What does my character want in this scene? Can I make it a deeper need, raise the stakes? What is the disaster at the end of the scene? What happened just before this scene (Mom burned the toast!)?

Sometimes, the setting and scene structure is clear and I just start writing and let the actions unfold as they will. Sometimes, though, I write out possible beats: what small actions could these characters take that will add up to the character seeking his/her goal?Often, I write just a section of the scene and have to leave off because of time, or because I need more information. If needed, I research setting, events, actions, props; I free-write dialogue that might take place; I experiment and write a draft that I know is just a place-holder until I get something better done.

I like to write the scenes needed for a chapter before I stop to go back and reread. For this novel, that’s 1-3 scenes per chapter.

Later–maybe the next day–I come back and re-read everything and edit, change, omit, totally rewrite, rearrange: in short, I revise.

Then, I read everything from the beginning, looking for flow and pacing and trying to make sure the story has consistency in it’s tone and voice.

Finally, I start a new scene or chapter.

The process is messy, circular and imperfect. But in the end, it does produce a first draft. First drafts are to tell you what the story is about; second drafts are to figure out the most dramatic way to tell that story. I’m still figuring out the story of my WIP and for now, it’s going well. The process is working.

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: novel, rejection, write, revise, novel revision, Add a tag

After a stinging rejection: today, just a quote from Art and Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking, by David Bayles and Ted Orland.

It’s called doing your work.

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: kids, humor, comedy, funny, revise, how to write, novel revision, Add a tag

I am working on an short chapter book and I want it to be funny. My kids say I have no sense of humor and they are right. But fortunately, I have a quote for that:

You can be funny–I’m told–if you just revise. Here are some ice cream recipes. Place holders. First, it’s important to know that it’s OK to write a joke-lets or jokoids, places where it could be funny, but it isn’t yet. Or places where there is irony or humor, but I haven’t milked it yet. These placeholders mean that I’ve put into the story the elements that need to be there–I just haven’t exploited them yet. That comes in the revision. Funny Technique #1: Setup, Setup, Payoff

NOT a joke, not even a good joke-let. It’s nothing but a question and answer. But can I make it a joke?

Interesting, but not there yet. What I need is two comparisons and a third that is ridiculous in comparison? What small things are in a kid’s experience, what space or size would they think is tiny? The school janitor’s closet. The boy’s bathroom. A submarine. Kids packed into a school bus. A school bus would seem like a mansion compared to our family space ship. No, flip that and put the payoff last: Compared to our family space ship, a school bus would rank as a mansion. Let’s try that one.

Is that better? Yes. Of course, it is. Not hilarious maybe, but sharper, bettet. Funny Technique #2: Doorbell Effect or Setting up Expectations

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: the end, revise, novel revision, finish, how to know a story is finished, when to stop revising, story, novel, Add a tag

DearEditor.com is hosting a “Revision Week” in which she interviews various authors about their revision process.

It’s true.

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: conflict, novel, authors, deus ex machina, write, revise, rose, starr, how to, external, internal, ending, caroline, protagonist, Add a tag

Debut Novelist Prunes her RosebushIntroduced first in 2007, debut children’s authors have formed a cooperative effort to market their books. I featured Revision Stories from the Classes of 2k8, 2k9, 2k11 and this year, the feature returns for the Class of 2k12. Guest post by Caroline Starr Rose, author of MAY B., MG, January 2012 My first-round edits arrived with a four-page letter attached. In it my editor praised my writing (“This story is like a prize rosebush that needs just a bit of pruning!”) and pointed to some “thorns” that needed work. (From Darcy: Ha! Notice Caroline’s last name.)

My original ending was contrived. It just didn’t work. In order to change this, I had to weave bits into the beginning of the story to make the ending more plausible, and I had to be okay with leaving the outcome/redemption of one character, Mr. Oblinger, open ended. This was hard, as I really believed in his motives (even if they didn’t play out as he anticipated), but in keeping with an ending that wasn’t “artificial or improbable”, there was no room for this. Tying the Revision Process TogetherThroughout the revision Add a CommentBlog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: reading, revise, darcy's books, TOC, novel revision, on screen, search and replace, Add a tag I’m at the point in my WIP when I need to reread with a critical eye. Where did I leave that thing? I’m out of town on family business, stealing a few hours here and there to work. Because of this, I can’t print the thing out, which is what I really need to do. Reading on screen is more difficult for me, because I can’t move back and forth between sections easily, can’t flip a few pages to find what I’m looking for to check for consistency, for gaps, for repetitions. I’m working on a update and revision of The Book Trailer Manual. One goal is to expand the section on how to write a book trailer script, including recommending some software and detailing the process more clearly. Another goal is to update the recommended software for actually producing the video, including adding about a dozen new, free resources. Finally, I”ll be looking at all the examples of trailers and updating the list of trailer to study. Doing this revision all on-screen means I have to find new strategies for working.

What techniques or tips do you have about editing on-screen?

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: author, novel, authors, debut, revise, how to write, kiki hamilton, 2k11, Add a tag

Random Acts of Publicity DISCOUNT:

Debut Novel: Spreadsheets Used for Plotting and Revising a NovelIntroduced first in 2007, debut children’s authors have formed a cooperative effort to market their books. I featured Revision Stories from the Classes of 2k8 and 2k9 and this feature returns this year with the Class of 2k11. RevisionGuest post by Kiki Hamilton Revision is hard work. There’s no two ways about it. But it is necessary to improve the story – sometimes it’s the way the writer finds the real story. Though there can be times when it feels like the process of revision never ends – it doesn’t have to be overwhelming. I like to think of it as making a cake. You have to work in layers. The first layer is the plot structure. There are lots of different ways to draw out the plot or story arc of your novel. I use a color-coded Excel spreadsheet, others use sticky notes – either way is fine – as long as you have some way to see the overall scope of the story. Divide your story into acts: The second layer includes: characters, theme, emotions, plot. Once you’ve got your structure in place, take a look at the elements that create your story: Characters, Theme, Emotions, Plot. Are your characters three dimensional? Is your protagonist well-developed? Do we care about them? Is there a theme present in the story? Here’s a big one for me – is the plot believable? Do the protagonist’s choices make sense? The third layer contains the supporting elements. This is the time to look at side characters, dialogue, scene transitions, and pacing. Are the side characters necessary? Do they get enough time on stage? Do your characters speak in a believable way? Cliffhangers are great but make sure that when you move from one scene to the next, or one chapter ending to a new chapter, that you do it in a way that your reader can follow the timeline and sequence of events. Also, it’s hard to look at your own work objectively, but try to see where the pace of your story drags and where it might move too quickly. The final layer is the details. This is my favorite part of the revision process. I lik Add a CommentBlog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: story, kids, book, picture, picture books, write, revise, how to, childrens, Add a tag

Random Acts of Publicity DISCOUNT:

Writing is rewriting

For years I have been saying that writing is rewriting, and now I have a book that shows it quite clearly, my new picture book, Road Work Ahead (Viking 2011).

Picture Book InspirationWhen my son was 2, he loved to look at all of the trucks and machines along the road, so I started snapping pictures for him. I made him a “look book” that later turned into a picture book. I loved the story in that book, so I sent it out to editors, but it kept coming back, over and over. Editors said they loved it, too, but it wasn’t quite ready. So I kept rewriting it and sending it out…and now 25 years later, it’s finally a book you can hold in your hand. The 6 Ws of StorySo what made the difference? I used ALL of the 6 Ws this time. I made sure the story had who, what, when, where, why and how. Using all 6 Ws made it a story, not just a list of machines along the road. Stories sell, but lists…well, not so much. New Beginning and Ending. After the story finally sold I thought it was ready to go, but my editor thought it needed something more. She asked me to write a new beginning and ending, so we knew why the little boy was on the road looking at all of the road work. That also added a who, by showing us the little boy before he got into the car. So I added my mother and her famous homemade oatmeal cookies to the book. (We used to eat them right after they came out of the oven. Yum!) Driving to Grandma’s house for fresh, warm, homemade oatmeal cookies is definitely a reason to keep going despite all of the traffic delays due to the work along the road. And when you get to eat them at the end of the book, ah, sweet reward! Adding 2 short stanzas was all it took. The change I made was used by the Publishers Weekly reviewer to describe the book.

The text quoted in the review was the original beginning of the story. I had jumped too far into the action. What worked better was taking a few steps back and letting the reader know who the narrato Add a CommentBlog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: revise, bad, good, how to write, novel revision, worst, progressions, novel, Add a tag

Random Acts of Publicity DISCOUNT:

Do things get worse in your story? Then you are using some sort of progression: good, worse, worst. That’s excellent, because you want the story characters to increasingly feel the conflict and tension of the story. But are you using the BEST progression possible?  Close up of Street Vendor in Urumqi, China

CLOSER

CLOSEST Mark Each Add a Comment Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: novel, plot, quest, structure, revise, how to write, novel revision, 3 acts, act 2, act 1, act 3, maturation, plot templates, restructure, Add a tag

Using the 3-Act Structure: Adjusting ExpectationsMost writers use a 3-act structure and for good reason. It works.

Somehow, in all the revisions, the structure has become top-heavy. Skimming those chapters or laying them out in a shrunken manuscript revealed that several scenes repeated; there was escalation with each repetition, so it wasn’t all bad. Still, I wondered if I could cut a considerable chunk from the first section. Today, I cut 2000 words! Hurrah! But, with a sinking feeling, I realized that it is still top-heavy. Could I stand to cut another 8000 words? Probably not. That would gut too much of the emotion and story. Restructure the 3 ActsThe only answer then, is that I must restructure the story, must think about it differently, set it up differently. Fortunately, there are 29 plot variations or plot templates and at least three types of character arcs. Will one of those work? As is, it’s set up as a quest: now in a quest, there should be character growth and often what the character sets out to discover is not what they need, not what they find. But it’s that definitely stepping into a “new world” that is bothering me in this story. The new world can’t be the fantasy world they find in the story because that now comes at about halfway through the story. IF I consider this a story about maturation, and not a quest, then the current structure is very close. At page 21, out of 80 (single spaced, small font—just the way I like to work; I will reformat before I send it out), there is a first step of defiance of Father, a step into the world of adulthood, if you will. That’s about the 25% point and works perfectly. Likewise, the rest of the plot points fall into line. Making this type shift is subtle: it’s not about the plot or actions, per se. Instead, it’s about setting up expectations in a reader’s mind. They intuitively understand this deep structure of dividing a story into acts, and subconsciously expect it to happen. If I set up the story, with subtle word changes, as a story of maturation, I think it will work. That crucial transition from Act 1 to Act 2 will be the move into the world of adulthood, of bei Add a CommentBlog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: writer's block, revise, novel, character, characters, plot, characterization, Add a tag

OK, so I have this revision to do and one key element of it is to deepen characterization and relationships. Uh, oh. My weakness! How did the editor know that it was my weak area? Even after spending agonizing hours on characterization, I’m still not hitting the mark. Which left me stumped on this revision. I’m not blocked. Just don’t know what to do next. Here’s my analogy. In China, we passed by open doorways that led to teensy courtyards from which four houses (or more) might front onto. We could look through the doorways, but the glimpse was brief, you didn’t get much detail.

That’s how I tend to write characters, from the outside looking in. But this week, I’ve been rephrasing the question. The answers can NOT change the plot, the actual actions of what is going on. I’m actually happy with the plot. Instead, I’m looking at the inner person, the relationship which is revealed by the plot events. Asking about relationship seems easier to me than asking about how to characterize. It’s interactive, as one character does something, the other must respond. If I can find a central thing around which I can center conflict and reveal character with that, it will work. In the current scene, the characters are discussing going somewhere and they both agree that they need to do that. Well, there is conflict in the plot, because it’s a daring thing they do. In the revision, though, I’m having Character A hesitate, wondering if she should consult her father or someone other adult before going. Meanwhile, Character B is impulsive and confident. “A” generally has a superior attitude to B, so she can’t let him get the upper hand by being so bold. And thus the relationship develops. Who will bluff the other into action? Who will compromise their ideals to prove to the other they are tough? It’s like zooming into that Chinese courtyard to see the small details. Suddenly, the relationship has revealed details of the character and we see clearly. Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: revise, action, how to write, verbs, novel revision, sensory details, novel, characters, characterization, tone, Add a tag

Working on a novel revision, I realize that I need to refocus the relationship between two characters. The question is where to start. Grand Entrance for Your CharacterI once heard the late Sid Fleischman talk about the importance of giving a character a Grand Entrance. Think about a stage play, where a character sweeps onto stage commanding the attention of the audience. It’s a first look at the character and sets the tone for everything that follows.  Characters out of focus? Start revising with the Grand Entrance Scene. I’ll be focusing at first on the scene where Character B comes on stage and crashes into–literally–Character A. Right now, the scene sets up a romantic relationship and I want to back off that and make it more platonic. How to accomplish that? Actions. First, I’ll look at the action verbs. A story is almost always contained in the verbs. Too many “to be” verbs (is, are, has, had, am, etc.) and the story is flat, uninteresting. Action verbs characterize and I want to sharpen the characterizations while setting up the relationship differently. It’s not that the ACTION — what the character DO — will change much. But the meaning of the actions will take on a different tone. Sensory Details. Likewise, the choice of sensory details will be crucial: visual, auditory, tactile, gustatory (taste) and olfactory (smell). For example, if you want to talk about a romantic relationship, you might describe a guy with these details: musky smell, soft curly hair, rough baritone voice, brush of his lips and –well, let’s forget the taste one for now. On the other hand, a more platonic relationship might be sweaty smell, greasy hair, clear voice, firm handshake and –well, taste just doesn’t work here, either. I’ll be looking at the actual choice of words carefully. I don’t expect that the scene’s actions will change much, but the reader should get a very different feel for the character relationship. ToneOf course, all of this relates to a slightly different tone set up in the relationship. Tone is that underlying attitude that characters have toward something that comes out in the language choices of the writer. I don’t want romance here, but an honest, growing friendship. I’ll use action verbs and sensory details to change that tone in this scene of Grand Entrance. If I can nail it here, it should act as a touchstone as I revise the rest of the novel. Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: how to write, novel revision, tension, stakes, book, novel, character, revise, Add a tag

So What? That’s the question you must get past in your fiction. Why should a reader care? Keep Reader’s Interest: Make Everything Matter MoreThe best way to make a reader care about your story, your novel is to make things matter more, put more at risk, up the stakes. Personal StakesThis can be accomplished on multiple levels. The first is a personal level. We must care about your character for some reason. A typical kid in a typical school is boring. Why do we care about this character?

Public Stakes

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: critique, revise, novel revision, first reader, beta reader, novel, feedback, Add a tag

I’m working on a novel and have just gotten a couple rounds of feedback from friends. Here’s what I noticed. They didn’t give me the answer I wanted!

Notice: They are not telling me that I must change anything! They are merely giving me a professional opinion about what might need a second look. Sigh. Good friends, aren’t they? They don’t let me get by with mediocre. They Let Me Ask QuestionsAccept Ultimate Responsibility. I have no idea where it started, this idea that authors should sit quietly and “take criticism.” It’s ridiculous. At least, to me. No, I’m not arguing and saying that YOU are wrong. Of course, you’re just giving me “your opinion.” Of course, I need to know what you, as the reader, were feeling and experiencing as you read. That’s great. But what I ALSO need is to understand exactly what you mean when you say, “I didn’t like that part.” I need to ask questions to clarify the feedback, or the feedback is pointless to me. Did you not like it because you–personally–hate dogs and would never voluntarily read about them? Or did you not like it because the pacing was off? Or was it a single word choice that would make a difference? Did you pick up on something in the last chapter that leaves you expecting something here? If so, can I change that bit in the last chapter and make this work here? Or, do you really think I must change this bit here? There are so many, many variables in writing fiction: everything builds on what was done before and the choice of WHERE to revise is open; everything builds on the interconnections between ideas and language and the choice of WHERE to revise is open. How can I make a wise choice, if I don’t understand exactly–with a great deal of precision–where the problem lies? Fortunately, my friends let me “argue.” I need that. The Ultimate Choices are Mine: I Appreciate the HelpBe Thankful. In the end, though, my friends also leave the choices with me, as it should be. This is my story and it’s my vision for the story that matters. They suggest, prod, try to veto, nudge and encourage. That’s all they can do. In the end, it’s me and the words on the page. But thanks friends, for those nudges. I need those to keep going!

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: novel, first draft, revise, how to write, novel revision, Add a tag

I woke last night and wrote and rewrote endlessly the first line of my new novel. Yes, it is an important line, but it’s not important enough to stop me from writing a first draft of the first chapter. Place Holders

Place holders have an important function in the first draft. They let you get the story told, without fussing over the exact details. You get a sense of momentum, that you are moving forward. The story is the focus of the first draft, getting it down on paper, from first to last, opening scene to climax to denouement. The function of the first draft is to find your story. So, using place holders in the first draft makes perfect sense.

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: 2k11, bettina, respreto, novel, authors, debut, revise, Add a tag

Bettina Restrepo Debuts with ILLEGALIntroduced first in 2007, debut children’s authors have formed a cooperative effort to market their books. I featured Revision Stories from the Classes of 2k8 and 2k9 and this feature returns this year with the Class of 2k11. Guest post by Bettina Restrepo Recently, I performed a paid critique of a teenager’s novel. While I carefully weighed my words to encourage the young writer, I knew he needed a vigorous critique to move forward to revise. No one wants to feel like they have to redo their work. Rewriting a novel reminds me that revision is like growing up. I want to skip childhood and get to the good part. My novel, ILLEGAL, grew from two picture books. Each time I rewrote the book, I taught myself how to revise. I learned more about the tedious revision process. Then, I discovered the work was learning to live and listen. Characters Calling. First, by combing through each word and sentence, I hear more parts of the story from the characters inside the book. I keep many novel ideas sitting inside a drawer. But, I only work on the stories where the characters call and beckon me with more details of their life. As I grow in maturity, I add new life experience which gives me deeper understanding of my characters. It takes life to influence great writing. Patience and Tenacity. Second, I learned patience and tenacity. Long before I had an agent, I had to print out the pages, schlep to the post office, and send off my baby manuscript to live amongst the slush piles. Three months later I would status query. Three months later, I would nudge. But, during those six months, I went on to write other things. Each time when the manuscript came back, I looked at it with new eyes. The returned manuscript contained a generic rejection letter, sometimes with providing a golden nugget of information. I listened to the advice doled out and I heard (sometimes) what was meant. My tenacity came as I realized that these rejections weren’t about me, but rather about a story that wasn’t ready – yet. Growing as a Writer. Third, I’m continuing to learning patience and it’s getting easier. I am no longer a baby writer, crying for Mama to read every morsel, to feed me the answers. I crawled around the publishing world putting genres and techniques into my mouth to see what worked. I did the rudimentary drills to learn multiplication, faced the schoolyard bullies. I tackled Algebra; even though I was convinced it would never apply to my life (once again, wrong!). Lifelong Challenge. As I begin my fourth novel, I’m beginning to understand that my learning curve is a tangent – stretching out into places I never imagined. Learning how to revise will continue to b Add a CommentBlog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: revise, how to write, novel revision, old draft, book, novel, Add a tag

Do you look at your old drafts? Save! Looking Back or Finding What Worked Old Drafts Yield Strengths and OptionsWell, this time, I went looking at the old drafts and found some surprising things: In one old draft, I told the story early to some youngsters. And–I like that. It worked. I’m going to try that again. But this time, I’ll rewrite the legend itself to make it a more exciting scene and not just a narrative that is told. Playful Elements. I also used some playful elements in earlier drafts. Why did I give those up? Maybe, I wasn’t confident enough to be that playful, to trust that the reader would get it. But I like some of the play there and want to work some of it back in. Mostly, looking at old drafts has given me some options and perhaps, unveiled some hidden strengths of my writing. If you haven’t done it lately, open up some of those old files and look for golden words! Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: write, revise, how to, novel revision, foreshadow, novel, Add a tag

Balancing the Need for ForeshadowingI’ve been revising a mss, taking a break from doing a new project. Recent feedback told me that my novel was great, except the opening didn’t set up the “magic” of the story well enough. It was too great a shock when it suddenly occurred on about page 50.

Foreshadowing is anything that lets the reader have a hint of what’s coming. Hints. More than just that, I needed specific hints of what was coming. These hints needed to hook the reader, not by explaining everything but by creating compelling questions in the reader’s mind. In the new opening, I firmly stayed in the here-and-now, and if the main character already knew something, I didn’t explain it. Instead, I let the reader wonder what the main character knew that the reader didn’t. In other words, I didn’t explain everything. I let some things just stand as stated, that thus-and-so had happened. There were some explanations, but the key here was to achieve clarity in the scene, while still teasing the reader into turning the page. It’s a delicate dance, staying in the present, yet pointing toward what’s coming. But foreshadowing is one of the goals of opening chapters or prologues. Here are some tips:

Blog: Writer's Cramps (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: chick lit, manuscript, literary agent, revise, rewrite, Add a tag

Two agents have weighed in on my book. Agent #1, on whose critique of the first 75 pages I bid at a charity auction, said, This delivers. You have quirky characters, and people up to no good. I love the humor in the book; you’re very funny.

0 Comments on They liked it. They really liked it! as of 1/1/1900

Add a Comment

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: novel, character, plot, scene, write, revise, edit, how to, novel revision, 30 days, stronger, Add a tag

30 Days to Stronger Scenes: Table of Contents

We spent November talking about how to write stronger scenes. Here’s a handy Table of Contents for the series.

SCENE 6: Keeping Scenes on Track SCENE 7: Showdown in Every Scene SCENE 8: List of Possible Scenes SCENE 9: Scene List v. Synopsis SCENE 10: Plotting with Scenes SCENE 12: Avoid 5 Plotting Mistakes by Using Scenes SCENE 13: Not Worthy of a Full Scene SCENE 15: How to Salvage a Scene SCENE 16: Aiming for Bull’s Eye SCENE 17: KaBlam! Dynamite Scenes SCENE 18: Special Scenes: Flashback Scenes SCENE 19: Special Scenes: Openings SCENE 20: Special Scenes: Big Scenes SCENE 21: Special Scenes: Set up big Scenes SCENE 22: Special Scenes: Climax SCENE 23: Special Scenes: Final Scenes SCENE 24: Stories that Spaghetti Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: book, novel, write, revise, how to, novel revision, fix, scene cut, Add a tag

The Stuff Between ScenesGuest Post by Deborah Halverson

As you give thought to what happens in your scenes, give thought, too, to what happens between them. There’s a trove of information and emotion lurking in the white space separating the last line of one scene and the first line of the next. You’re the master manipulator of your story—you should know exactly what’s happening in that space. Magical Leap. Only in fiction can a kid transport magically from, say, a humiliating moment after school to the next morning when he must deal with the fall-out in the school halls. In real life, we don’t get to skip from scene to scene. We must live those in-between moments, going home and dealing with dinner and the family, doing the dishes and brushing our teeth, trying to sleep only to fail or perhaps achieving sleep only to nightmare—or maybe even sleeping soundly and feeling refreshed in the a.m., determined to take down the bully who served up that monster wedgie during the seventh grade talent show. As a writer, you wouldn’t show all that at-home minutiae to your readers because it would hobble your pacing and nuke the tight tension you’ve built up. But you should know what’s happened in that white space so that you can fully understand how one scene’s ending has simmered and stewed its way into the first line of the next scene. Simmer. Consider that kid who suffered humiliation—he might interact badly with his family that night if he interacted at all, he’d scrub the dishes and forget to rinse, he’d fumble his dad’s favorite mug and get chewed out, he’d cut his gums with the floss and cry. He’d work himself into a real funk, or a real stink, or a downright rage as his day flowed from terrible to just too much to bear. When something rotten goes down in your life, your minutiae seems to gang up on you, doesn’t it? Don’t start a new scene with the assumption that a character’s emotion and state of mind are exactly where they were when you left him a day or even an hour ago. That’s not realistic and it undermines your scenes. Simmering happens. And that simmering takes place in the white space. By the time your character reaches the opening line of your next scene, he’s in an advanced state of emotion or has had time to hatch a plan, as flawed as it probably will be. Fully understanding how his mindset and emotion have festered during the scene jump allows you to fully exploit both of those things in the happenings of the new scene. Mull. Mulling is an important part of writing, and that’s what this is—mulling the off-stage events that are part of your character even if you don’t share them with your reader directly. And you won’t. Just as you may know a character’s life story but won’t deliver it when you introduce him, you don’t deliver the stuff in between scenes even tho Add a CommentBlog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: Roz Morris, sense of purpose., conflict, book, novel, change, scene, revise, edit, how to, repetition, consequences, novel revision, Add a tag

Top 5 Tips for Dynamite ScenesGuest Post By Roz Morris

Have you got a scene that’s looking lifeless? Here’s how I pep it up. Have something change. No scene should ever go as the reader expects. If you have a character set out to buy a pint of milk and all they do is amble to the shop, buy their stuff and walk back, you’ve hit the snooze button. Instead, take that scene somewhere the reader is not expecting. It needn’t be a big twist. It could be tiny – a change of mood, a resolution to do something. But if nothing changes, the scene isn’t worth showing. Make that change have consequences for the characters.Suppose you add something to your milk-buying scene – the character realises her boyfriend claimed he bought a certain brand of cigarette from the corner shop, but that shop doesn’t sell them. So where did he get them? And isn’t it odd that they are the same brand smoked by his ex? Are they seeing each other again? If you have to fill a blank, bring something in that you introduced earlier.In the thick of a scene, you often have to invent details off the top of your head. Where was your minor character John last night? The cinema, you write, because it doesn’t matter where he was, he’s not very important. But go back and look at what you’ve written about John before. Is there something else you already invented that you could bring in instead? Three chapters ago, did you send him, quite casually, to choir practice? Why not send him there again, or to the chemist to get throat lozenges? Now we’re fleshing John out and with very little effort. Featured Today in Fiction Notes StoresBringing back ideas you used before is a great way to make the world of your story feel more solid.Even if what you’re using is trivial it can build up – and who knows where it might lead? It’s a technique called reincorporation. It makes stories elegant and satisfying. And it adds to the feeling that everything matters. Add a CommentBlog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap) JacketFlap tags: story, Picture book, picture books, language, revise, length, how long, Add a tag

Stop! Before you send out that picture book manuscript, cut it by at least one-third. Really. Make that revision. Biggest Mistake in Picture Book ManuscriptsI recently read a picture book manuscript from a novice writer and it had the usual problem: too long.

STOP! Cut Your Mss by 1/3. At Least!Before you send out your mss, try to cut it by 1/3 without changing the story. Then try to cut another 50-100 words. Compare the before and after. If the story has changed (for the worse), you can add back a few words; but I’ll wager that the story will be much stronger with the revision. While there are no hard and fast rules, picture books that run 500 words or less tend to sell better. For pre-school stories it’s a stricter limit than for school age (K-3).

|

I like the idea of place holders in fiction. That is, you write something–a sentence, a title, a paragraph, a joke, a piece of dialogue–knowing that this isn’t the best it can be, but also knowing that you’ll come back and fix it.

I like the idea of place holders in fiction. That is, you write something–a sentence, a title, a paragraph, a joke, a piece of dialogue–knowing that this isn’t the best it can be, but also knowing that you’ll come back and fix it.