new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: protagonist, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 16 of 16

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: protagonist in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Hi folks, I'm starting a series that will last for the summer. It's called Publish and is in conjunction with my TEENSPublish workshop at the Ringer Library in College Station, Texas. This first week I'm covering pre-writing. I think some of this will relate to any creative life.

Publishing is different than writing. The two are related but not the same. Writing is about splashing the words on the page. Writing can be personal, for yourself. Writing that will be published comes with an added zest. It's not about the writer; it's about the reader. Every word will be seen by others. Every word will have the potential to influence someone's life. Every word must grab the reader and shake them up. If not, the words won't be read.

The most important words of a story are the first five pages. If you can get someone hooked on the first five pages, they will read the rest of the book. I mentioned if main characters were waking up in the first scene that there better be a sack of flesh-eating spiders about to descend upon them. I suggested the participants check out The First Five Pages by Noah Lukeman. This is a handy book to sharpen the hook.

As a part of pre-writing, we talked about the need for an interesting main character. If a character doesn't have redeeming qualities, no one will follow him or her to the end of the story. Anti-heroes are popular right now. Going against the grain is always popular. Sadness is having a heyday too. All this is fine but it is important to add likability to the main character. This is huge. Some quick tricks to garner likability -- save someone or something in the first chapter, create contrast with exterior and interior self (i.e. hard criminal - exterior, wounded protector - interior.), finally, isolate your character by killing off everyone he or she loves.

Finally the last thing in pre-writing was the chance for each writer to discuss their story without interruption. We live in a world that is all about being heard. The chance to speak without anyone immediately jumping and contradicting and offering an opinion is rare. Each participant was given seven minutes to share their vision without interruption. How many times do we get the chance to be heard? It is so rare. It's also a chance to listen. Our society has lost listening to each other, and in this we have lost something of ourselves. It's so important to be quiet, to be still, and hear what is being said. Writers need to listen. To tell the truth, we all do.

I hope this journey into pre-writing was provocative to you. I hope that you think about all this as you move forward with projects. Next week, I'm going to cover characterization.

Now for the doodle. Cat Doodle

Quote for your pocket:

At dawn my lover comes to me

And tells me of her dreams

With no attempts to shovel the glimpse

Into the ditch of what each one means

At times I think there are no words

But these to tell what's true

And there are no truths outside the Gates of Eden

Bob Dylan

The best villain for your story may not be a moustache twirling bad boy. After all, moustache wax is a tad out of fashion. Take a look at this list and see what other options may fit your next work in progress.

The ProtagonistYes, you read that right. Your protagonist can be her own worst enemy. Take a look at her faults. Or try something more difficult. Maybe you could create a situation where her strengths are her greatest handicap. Her issue could be as soap opera as amnesia. Will she remember what she has forgotten in time to save the day? Or maybe it is as ordinary as bad self esteem. She only has three days to apply for the fellowship if she can work up the nerve to do it.

The Best FriendYour main character has a goal. What happens when her best friend wants the same thing and only one can prevail? Or maybe they don’t want the same thing but opposite things. Obviously, someone is going to have to learn to live with disappointment, but which one? And what is each person willing to do to assure that she is the winner? You can make this especially tense if your main character has a reason to let her best friend win.

Animal AgonyWhat if it is a creature who’s got your main character’s goat? A furiously digging armadillo has destroyed the landscaping job that will keep her fledgling company in business. An endangered species has put the development project she needs to jump start her career on hold. We’ve all dealt with them, the feathered, furred and finned that simply will not mind their manners.

Mother NatureBigger and broader than an animal pest is Nature as an opponent. A threatening storm, a towering mountain or stormy seas can all put your character’s hopes in peril. Not sure how this might work? You do remember a wee little boat called the Titanic, don’t you?

The next time you need to throw something between your character and her goal, think of something other than your stereotypic bad boy – unless of course, you’re writing a steamy romance!

–SueBE

Author Sue Bradford Edwards blogs at

One Writer's Journey.

By:

Claudette Young,

on 6/3/2012

Blog:

Claudsy's Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Online Writing,

Plot (narrative),

Mind-Mapping,

Work-related,

Today's Questions,

Writer,

Life,

writing,

Art,

Arts,

Writing and Poetry,

Short story,

Protagonist,

Writers Resources,

Add a tag

Today, I want to show you how many writersgo about clustering ideas for

Blank Mind Map–Clustering

story development.

The process is simple. Daydreams draw on it all the time. Draw a circle, square, whatever you like in the center of a piece of paper. Go ahead, draw it. Inside that shape, put a word or group of words designating a specific something; desire, idea, plan, objective, goal, or whatever.

For our purposes here, I’ve put “Main Character—Isabel” in my circle. Now, all I’m going to do is let my mind provide everything it can think of that could be related to this character named “Isabel” and draw a line radiating from the circle to the new word. “short” “dark hair” “tanned skin” “Speaks with an accent” “watery eyes” “clubbed foot” “Orphaned” “City dweller” Hates mice” “Can’t read” “generous nature” “hears voices” “Knows the king” and on and on until I fill the page.

I do this exercise quickly. (Most of the time I do this on the computer with my eyes closed.) I don’t stop to ponder any of my associations or to question where any came from. I only write whatever word comes to mind as quickly as possible to make way for the next word.

When I look back at what I’ve written, I will find anomalies. In the example above, some items are capitalized and some aren’t. Why? What is it about the ones with caps that make them important enough to warrant a capital?

Isabel speaks with an accent. Where does she come from if that is true within this story?

Isabel is an orphaned city dweller who can’t read. Why is it critical that I know this about this character?

Isabel knows the king. How does she know the king? Now that’s helpful and important. So, why are the other pieces important, too?

Without answering these questions, I’ll move on to the plot cluster to see if I can find answers there.

Plot Idea Cluster center–(Isabel’s story) “Taken from the king’s household during infancy” “Related to the king” “lives in the weaver’s quarter” “indentured to Master Weaver Challen” “Doesn’t go out in the daytime” “King has ordered a celebration for his son’s birthday” “City faces a dread disease”

Lots of capitals here. Let’s see what I have now. Isabel, disabled with a clubbed foot, lives in the capital city where the king has just ordered the celebration of his son’s birthday and at a time when the metropolis faces a dread disease. An indentured person to Master Weaver Challen, Isabel lives in the weaver’s quarter and doesn’t venture out during the day. How she was stolen from the king’s household during infancy is unclear as yet or what

By:

Claudette Young,

on 5/18/2012

Blog:

Claudsy's Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

characters,

Arts,

Programs,

Writing and Poetry,

Protagonist,

Fanfiction,

Online Writing,

Work-related,

Life,

fiction,

Television,

Add a tag

The Star Trek fanzine Spockanalia contained the first fan fiction in the modern sense of the term. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

An entire genre has developed itself over the past 40 years or so. Ever since the original Star Trek warped through space, we’ve toyed with the idea of all those stories that never got written about the characters that intrigued us, who captured out respect and hearts. The movement became known as Fan Fiction.

I doubt any serious TV viewer has passed up an opportunity to fantasize about what would happen if… and brought the conjecture back into the series fold as a full-blown story, whether it was written down or not. I’ve done it for years—had whole scripts with good plots, great characters, and even parts for all the regular characters. And the sad thing is that I could have done something with them, if only as fan fiction and not sent the script to the studio for consideration by that series’ team of writers.

It’s one of those “I should have” things that many of us live with on a daily basis. “I should have” gone to see… “I should have” known better than… Truth is, I had a girlfriend back in ’67 when I lived in LA, who’d just sold her script to Desilu Studios for a Star Trek episode. The day after she got word, she was murdered two blocks from our building. The incident sort of put me off Fan Fiction for a while.

Last year I sat down to write poetry of a minor competition—there were no prizes involved, but critiques. My piece didn’t do very well. The audience was too young. That happens more frequently than older writers want to believe.

I still have the poem, which I’ll share here in a moment. I went back through it and changed a few things here and there. It leaped out of the hard drive this morning, screaming at me to find it a home. Since I don’t have any markets (that I can find), I decided to drop it here in order to create a challenge for those who’re up for it.

Everyone has/had a favorite show from their childhood. Now’s your chance to create a little fan fiction to commemorate that show. Write a story in 200 words or less using your favorite character from that show. Or write a poem about said character in a new situation. Recapture the heart of the character and share it here with us.

There’s no prize involved; no judging either. We are merely sharing bits of imagination for the fun of it. Be sure to inform us at the end of the piece the name of the show and the character’s name if you haven’t used it in your story. That’s all there is too it. Don’t be shy. Branch out and explore some fun. I can hardly wait to see what everyone comes up with.

Here’s my poem and how I approached my character from those long ago days of the 60’s,

Rememberin

By:

Claudette Young,

on 3/19/2012

Blog:

Claudsy's Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writer,

Life,

Games,

writing,

Art,

Writing and Poetry,

Protagonist,

Hero,

Writers Resources,

Roleplaying,

Work-related,

Questions to Ponder,

Add a tag

How does your main character arrive? Does she pop into the mind, complete with secrets, aspirations, and whimsy? Or, do you have to sit down and get out your character building blocks to begin construction on the kind of character you want to deal with for however long it takes you to write an entire story?

Each type of character has possibilities for the writer. Think of the yourself as a casting director. A movie is being planned inside your mind and needs a cast to people the sets that are built to show/tell the story.

Cast of Characters: Primary figures

- Heroine—late twenties, had to leave college during junior year due to family crisis, didn’t finished education, works at local veterinarian’s office as a vet tech rather than the physician she wanted to be.

- Male lead—perhaps late twenties/early thirties, civil engineer, rugged and cocky in looks and attitude, considers heroine interesting but not worth the trouble of getting to know better—he has secrets hiding behind his eyes.

- Female support character—high school classmate, Miss Popularity, divorced socialite in town, waging intimacy war with male lead, has always looked down on heroine.

- Villain—possible murderer, keeping police baffled and jumping through hoops as she/he kills off various townspeople for no apparent reason, leaves too many conflicting clues as if playing cat and mouse with cops.

- Police detective—has known heroine all her life, used to date her in high school, pallbearer at her father’s funeral, struggling to stay in control of murder case even when he knows he’s over his head on this one, rethinking his career choice.

- Setting—rural town, population 12,000, Midwest locale, farming and college town.

With this list of pivotal characters, you can begin to build both plot and character studies. You must decide which to pursue first. For our purposes here, concentrate on characters.

Building a character takes planning. How would you tackle the heroine? When you close your eyes and think about this character, what do you see? How tall is she? What kind of clothing does she typically wear? What color is her hair? Keep thinking about her. Write down what you envision about this person. Listen to her voice, her speech patterns, and her quirks of expression. Have you learned her name yet?

Take a moment to meet her. Shake her hand. Is it callused, soft, long and lean, or square and pudgy? Do you join her at a table at the local diner?

What kind of people are in the diner and what is their behavior like? Is there a feeling of camaraderie among the locals, one of friendship or tension? Do you feel comfortable within this group? If so, describe what you feel as you sit at the table with the heroine.

Do this ceremonial meet and greet with each of your new characters. Find your place among them. Develop a rapport with these people that you’ll be working with for a while in the future.

The story’s setting is a character as well. You noticed it on the casting list. Setting is the biggest and can be the most complex of your characters. Take the time to get familiar with it. Learn so mu

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 2/13/2012

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

conflict,

novel,

authors,

deus ex machina,

write,

revise,

rose,

starr,

how to,

external,

internal,

ending,

caroline,

protagonist,

Add a tag

Debut Novelist Prunes her Rosebush

Introduced first in 2007, debut children’s authors have formed a cooperative effort to market their books. I featured Revision Stories from the Classes of 2k8, 2k9, 2k11 and this year, the feature returns for the Class of 2k12.

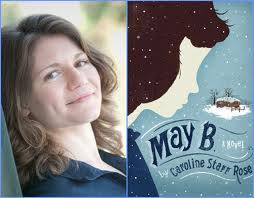

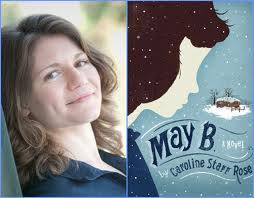

Guest post by Caroline Starr Rose, author of MAY B., MG, January 2012

Caroline Starr Rose, author of May B.

My first-round edits arrived with a four-page letter attached. In it my editor praised my writing (“This story is like a prize rosebush that needs just a bit of pruning!”) and pointed to some “thorns” that needed work.

(From Darcy: Ha! Notice Caroline’s last name.)

- More external conflict to go with all the internal business

MAY B. takes place on the 1870s Kansas frontier. Throughout much of the story, my protagonist fights to survive a blizzard. Nice external conflict, right? But much of the story is internal. There’s little dialogue, for one thing; May spends most of the story alone. She wrestles with memories of her inadequacy in school, and in her abandonment goes through stages of confusion, anger, fear and despair. But without some other tangible challenge, the story was lacking. My editor gave me a few ideas, and I latched onto one: a wolf that could terrify, challenge, and ultimately mirror my protagonist’s struggles.

- Whiny protagonist — don’t let your audience lose compassion!

I find it hard to stick with a book with a whiny character. To learn that May sometimes slipped into overkill was exactly what I didn’t want and exactly what the story didn’t need. As MAY B. is divided into three sections, my editor suggested I let May get her complaints out in the first two parts, but the third needed to be about growth, resolve, and moving forward. This advice provided a good way for me to watch my character’s progression and to temper her outbursts. Once May’s taken charge of her situation, there could be moments of doubt, but she couldn’t fall back into old behaviors. She had to push ahead.

- Ending = Deus Ex Machina

For those of you unfamiliar with this term, here’s the definition:

- (in ancient Greek and Roman drama) a god introduced into a play to resolve the entanglements of the plot.

- any artificial or improbable device resolving the difficulties of a plot.

My original ending was contrived. It just didn’t work. In order to change this, I had to weave bits into the beginning of the story to make the ending more plausible, and I had to be okay with leaving the outcome/redemption of one character, Mr. Oblinger, open ended. This was hard, as I really believed in his motives (even if they didn’t play out as he anticipated), but in keeping with an ending that wasn’t “artificial or improbable”, there was no room for this.

Tying the Revision Process Together

Throughout the revision

by Scott Rhoades

It's fun to make your bad guy an evil villain, wicked through and through. The kind of guy who ties young maidens to railroad tracks for the fun of it, and throws the hero on to the slow-moving conveyor belt at the saw mill, just because he can. You know: the kind of bad guy who spends his time laughing maniacally while he twirls his 'stache.

This kind of villain is motivated solely by the fun of being e-vile. Yeah, he might want something. Maybe he wants the hero's girl. Or the gigantic diamond. But he only wants it for the sake of being wicked. And he would have gotten away with it too, if it weren't for those pesky kids. But this kind of villain is one dimensional, and doesn't work well in most books.

All an antagonist is, really, is somebody who either wants the same thing your protagonist wants, or who has a good reason to stand in the way and keep the good guy from achieving his goal. The antagonist could be a good person, but we're rooting for the other guy, so we don't like him. The antagonist could even be a better person than the protagonist.

The important thing when you're writing is to keep the motivations of both the protagonist and antagonist in mind. Chances are good that your bad guy wants to stop the good guy from winning for reasons that he thinks are good. He might be right, or he might be misguided, but he's convinced.

The bad guy almost always sees himself as the good guy. That means he sees the good guy as the bad guy.

I'm sure Sauron thought he was doing Middle Earth a favor by taking dominion, while Saruman thought he was doing good by trying to stop the Black Lord and taking the power himself. Darth Vadar probably saw the Jedi as nefarious rascals, upstarts who wanted to thwart his plan to make the universe a better place.

My favorite example is politics. Whatever your political position, you believe your candidate is right and the others are wrong. The others see their side as right and the others wrong. For the most part, all sides believe they are going to make the world a better place if they win. If you are interested in politics, you no doubt see a good side and a bad side, and think of people on the other side as misguided at best, but most likely as people who are out to intentionally destroy the country. Guess what. The other side sees you the same way.

That's how it is with your antagonist. He believes he is right, that's why he is so determined to stop your protagonist from succeeding. During the course of the story, your reader might even start to wonder if the antagonist is right, because he clearly means well and is not such a bad guy. Meanwhile, your protagonist's flaws cast doubt on just how good a guy he is.

When two people want the same thing and both believe they are right, you have interesting conflict. As a writer, you can play with that. Maybe your narrator is unreliable. Maybe you play your reader so he thinks the bad guy might actually be the better man. Maybe your good guy does something that's easy to interpret as evil, even if his motivations seem honorable.

In other words, your antagonist is the good guy, at least in his own mind. His wants are every bit as valid as the protagonist's. It's just that he wants the same thing.

If you keep that in mind, you are sure to have an interesting story.

by Bonnie Hearn HillVampires? Zombies? Steampunk werewolves? Trying to dream up a fresh plot for a young adult novel can take you to some crazy places. Yet until you have a strong protagonist, you have only a daydream, not a story. This is as true in young adult fiction as every other genre. There are no shortcuts. Not even the most dazzling over-the-top plot can conceal an undeveloped protagonist.

Your protagonists race your plot forward, swerve around obstacles, and yes, sometimes barrel over the antagonists in their paths.

Sometimes the antagonists barrel over them.

Is your protagonist a sleek, nitrous-injected Corvette, or is he a Gremlin so meek and sickly, that even you, the author, feels the need to get out and push?

Think about some of the traits of great protagonists. Are they intelligent? Warm? Giving? Clever? Brave? Those are perfectly good traits, but if they are all you have, you’re running the risk of a perfect character. Have you ever known a perfect person or someone who pretends to be? What happens when you encounter these people in real life? Do you like them? Can you relate to them? Can you stand to spend any time in their presence? Case closed.

If you want to touch hearts and sell books, your protagonist needs only two basic traits. Think for a moment. What two traits can allow you to trust your story with this character you’ve created? These two. Your protagonist must be proactive, and she must be sympathetic.

• Memorable protagonists are proactive.A strong protagonist

protags. That doesn’t mean that he rushes out the door like a modern day Don Quixote. Something happens—a change—that forces him to take action. Perhaps a loved one is in danger. Maybe he’s motivated by money, honor, even a threat. Regardless of how reluctant your protagonist, something compels him to move forward and refuse to give up, win or lose.

• Memorable protagonists are sympathetic.You want your reader to cheer for and relate to your protagonist. In order for that to happen, that character must be worthy of such attention. In short, your protagonist needs to be sympathetic or at least empathetic.

Sounds easy enough, right? It’s safe to say that an unfeeling tyrant who marches through the countryside searching for orphans to steal is not sympathetic. Yet, it’s rarely that simple. A protagonist who cares for nothing, who feels nothing, or who robotically floats through his life is just as unsympathetic.

Only by revealing the vulnerable parts of his character, the squishy underbelly that most people try to protect, can we allow the reader to feel for him. The protagonist must have a hole in his life, and you must reveal it.

Maybe Mary had to drop out of school to raise little sis. Unfulfilled dreams are an excellent hole. Or she could be in love with somebody who will never return her feelings, which might remind her of how her father always loved the other sister more. A hole in your life is some missing element that both drives and impedes you. You’d better believe that every person on earth has one.

What’s yours? Look around at your friends and family. What are the holes in their lives? What makes them vulnerable? Any person who claims to have it all together, to possess everything he ever wanted, is usually concealing the biggest gaping black hole that ever devoured a galaxy.

Remember, your goal is to reveal the deep emotions that we’re taught as children to hide. Shame. Longing. Envy. Guilt. Those feelings come without

I’ve been working my way through an inspirational YA manuscript for, well, YEARS. I lovingly call it my “learning novel.” Recently I realized that it probably isn't’t a viable YA at all. Not one that today’s sophisticated young adults might be interested in anyway. The protagonist is sixteen years old, but she lives in an era totally foreign to most 21st Century American young adults. Also, her

.jpeg?picon=893)

By: Annie,

on 10/14/2010

Blog:

WOW! Women on Writing Blog (The Muffin)

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

point of view,

fractured fairy tales,

POV,

writing exercises,

protagonist,

LuAnn Schindler,

Nora's Lost,

pov character,

point of view character,

Alan Haehnel,

Add a tag

In Alan Haehnel's play Nora's Lost, Nora (the protagonist) suffers from Alzheimer's and wanders away from a nursing home. Her story is told by point-of-view characters, including a younger version of herself (pink and black scarf) and a younger version of her daughter (pink chiffon).

I'm not sure why Haehnel chose to use these point-of-view characters to share Nora's journey, but it works and creates a dramatic effect.

Think about your favorite stories. What's the POV? My favorite is The Great Gatsby, where a young and naive Nick moves into a cottage on Gatsby's property. We learn about the intense love affair between Nick's cousin Daisy and Jay Gatsby through Nick's eyes. And after Jay is killed by a crazed, jealous husband, we learn the deeper truths from Nick.

As storytellers, we choose through whose eyes readers view action and reaction. And, we decide if the protagonist or a point-of-view character earns the privilege of telling all. Can the protagonist be a POV character? Absolutely!

If you're in the planning stages, several exercises can help you determine who should be the storyteller. I have two tried and true methods that work.

- Fracture it. One of my favorite classroom activities to try differing POV's is to fracture or retell a fairy tale (any story will work) by telling the it from a different character's viewpoint. A great example is The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs by Jon Scieszka. In this version, Alexander T. Wolf explains what really happened when he met up with each of the piglets.

- Send a letter. Assume the persona of a standout character from a memorable story and write a letter to a different character in the same book. What's changed? What would you say to that character if given the chance to ask? How does the character feel about the action that took place in the storyline? Any secrets worth sharing? You may be amazed at the insight!

Limiting the involvement of a POV character can cause a few problems in a manuscript. Most importantly, it prevents the reader from seeing a lot of the action as it occurs. Instead, readers learn about what's happened to the main character ONLY after the narrator discovers the truth.

But the benefits of keeping the two separate can aid storytelling. Storylines can continue, which is important if a tragedy befalls the main character. And, a POV character can reflect on what's happening, offering observations that the main character may have never shared or realized.

At the end of Nora's Lost, all POV characters swirl around the old woman as she struggles for her life, memories colliding with reality, strong will clashing with fragility. It's poignant and leaves an impression on the audience.

POV is a powerful storytelling technique that can make or break a piece of work. Who is telling your story?

Photo of O'N'eill St Mary's Drama Department production taken by LuAnn Schindler (who also directed the award-winning play)

by LuAnn Schindler. LuAnn also writes a column for WOW!s Premium Green and freelances for regional publications. Her work is available on her website, http://luannschindler.com/.

Random Prompts for Character Development

Last year, I bought Natalie Goldberg’s book, Old Friend from Far Away: The Practice of Writing Memoir. A friend saw Goldberg present at a bookstore about this book and was impressed, so I bit.

Now, I’m not much into writing a memoir. My life has been pretty average. But I’ve kept this book close for the last six weeks or so as I work through the revision on my novel-in-progress. Why? Because it centers on character and has tons of prompts.

Yesterday I reached a point where I knew that A was thinking about B and needed to decide to invite her over to visit. But how could A justify this, since they were so different?

Old Friend prompt: The Half-n-Half chapter (p. 199-200) reminded me to look around the setting. Goldberg says, “Public school had it all wrong with their topics: justice, morality, liberty, freedom, education.”

Instead, she suggests you look around your setting. Apparently, she was writing that chapter at a coffee shop, because here is part of her list: “half and half, sugar, cherry jelly, peppermint tea, Pepsi. . . .”

Oh, I remember now. Characters live in the particulars, the specifics of who they are, not in the generalities. It took me only a few seconds of brainstorming to come up with band-aids. Yes, band-aids. A reflects on how B decided to get a plain skin-colored band-aids, not a neon color, or a Barbie or GI Joe one, or some other weird pattern, but just a plain one. That made B an okay person in A’s eyes. Short paragraph, in and out of A’s head in a blink.

That worked for me. Much better than the rambling thing I had tried before.

Old Friend has tons of short prompts, anything from one sentence prompt to a couple pages to explain something. It’s not that I couldn’t have come up with band-aids eventually; it’s just that these prompts, chosen randomly, seem to help me speed up the writing time, while deepening character.

Related posts:

- Motivations

- character development

- Character Bait

Here is another technique I learned from Darcy Pattison at the SCBWI Novel Revision Retreat:

Read the first five pages of your manuscript and stop. Now write down everything you know about your protagonist from what you've read. Be careful not to include things you, as the author, know. Limit yourself to things only included in these pages.

How did you do? Is your list general and vague, or do you have a strong sense of this person's personality, preferences, family, community, speech patterns, likes and dislikes, etc.? By five pages, your character should already be defined for your reader.

If you don't know your character at this point, you might need to move the action forward in your story. Check to see if there is backstory that can be eliminated. Jump in where the story truly begins. Your readers will pick up what they need to along the way.

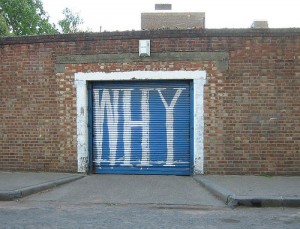

Answering the WHY? question

It’s the WHY question that is plaguing me right now.

Why does my character want to participate in this project?

Why does she want this so much that she will jump out of her comfort zone in order to make it work? Why, why, why?

Oh, how I hate that question! It’s obvious to me that the character wants this because, well, because that’s the story I’m writing. Of course, she wants to do this. Boy, am I in trouble.

I have to go back to the basics – again.

Interview the character. Find the back story details that answers the WHY? I’m such a private person that I hate telling people the whys of anything I do, so why should I expect my characters to be more forthcoming?

But how do you describe a fascination with something? For example: There’s no logical reason for me to like quilting, yet I do. I can make up something that will satisfy you, something about the puzzle of cutting up fabric and sewing it back together; but in the end, quilting transcends those explanations and I just wind up weakly saying, I love to play with color. Really, that’s it. I love to play with color and love the feel of the fabrics and love the semi-precision of sewing, fitting things together into a larger pattern.

How can I describe for a character a fascination with the tasks needed in this new story? There are multiple motivations: the inherent fascination with a hands-on process; the feeling of connection with a missing loved one; the reluctant joy of being pushed out of comfort zones to meet more people and to open up more; the surprise of watching how the project affects others. It’s so many small things that motivate my character. How to put those into the story?

Maybe part of the answer is that I was looking for a single answer, a single incident that motivates her and in reality, it must be multiple small things, which are woven into multiple scenes.

I’m wrestling today with that awful WHY? What are you wrestling with?

Related posts:

- Measuring Progress

- How Do You Get Back Into A Story?

By:

Samantha Clark,

on 7/29/2009

Blog:

Day By Day Writer

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

chapter one,

reworking,

Writing,

characters,

pov,

scenes,

Revising,

protagonist,

writing a novel,

Add a tag

Current word count: 16,822

Words written today: 394

Words til goal: 23,178 / 367 words a day til the end of September

Additional writing: revised two chapters in first novel. Now on chapter 20 of 33.

Yesterday I said that, as well as working on my new book, I have been revising my original novel, especially the opening chapter. In fact, I moved a lot of parts around so that a scene in chapter two became the new opener, a scene from the original chapter one was placed in the new chapter two, and 4,000 words were cut. The opener of this book has had more facelifts than Joan Rivers (ok, maybe not that many, but close  ), but this is normal, especially for the opening scenes.

), but this is normal, especially for the opening scenes.

To me, chapter one is the most important parts of a book, because it has to draw in the reader. The first few sentences have the biggest job of all. After chapter one, the second most important part of a manuscript is every other sentence, because each one has to keep the reader turning pages, and those at the end must resonate with the reader enough that he or she will want to treasure that book, recommend it to friends and seek out more by the same author. But that’s all after the reader has been enticed by chapter one.

There’s a generalization that most of the time, what’s written in chapter three is really the best start for the story because it takes a while for the writer to get into the story. This was very true for this manuscript. As this opener has had so much work done on it, I thought it would be interesting to detail it for you guys:

First draft of chapter one: POV not protagonist’s; scene showed the discovery of an item that is the reason for the protagonist to move.

Second draft of chapter one: same reason for scene but I tried a different POV, again not the protagonist (he can’t be in this scene). The reason I tried this second version of basically the same scene was because the first version was in an adult’s POV and I thought it would be better in a kid’s.

Third draft of chapter one: at a writer’s retreat, an agent suggested I use the same POV throughout, which meant I couldn’t use the item discovery scene as my protagonist couldn’t be in that scene. So my old chapter two, in which the protagonist is back home and first learns about them moving, became chapter one. This scene was reworked about three times for action as I got to know the character, but I’m not including them as individual drafts here.

Fourth draft of chapter one: In my new chapter one, my protagonist learned about them moving, but in chapter two he learned more about it as he eavesdropped on his parents talking, then in chapter three they moved. In the fourth draft, I realized that the story doesn’t start until they get to the new place, so I cut down all that back story to a couple paragraphs (at least it ended up being a couple paragraphs after many edits) and put it in chapter three, which became my new chapter one.

NOTE: All of this was before I had even finished the book! It was around this time that I got more dedicated, starting writing every day, and decided to forge ahead to the end of the book before I did any more editing.

In subsequent drafts of the full novel, the chapter one didn’t change too much from that fourth draft, except getting tighter and using better word choices. Until…

Fifth complete draft of chapter one: This was my latest reworking of the section, in which chapter two (technically, I think it would have been the original chapter four) became chapter one. Now in the opening scene, he has already moved in and is starting to explore his surroundings, the surroundings that bring him into the story.

I haven’t listed all the little word, sentence structure revisions that have been done in the various chapter ones. This lists just the major reworkings. But rest assured, there were numerous revisions for writing.

This kind of reworking is not unusual. Each story is different, and every time you write a new story, it will be different. But working on finding the best opening scene can take multiple tries. But it’s important work, necessary work. Many readers won’t buy a book unless they’ve read the first few pages and want to read more. I’m like that, and I know I’m not alone. If I’m interested in the title, I’ll read the jacket copy, and if I’m interested in the jacket copy, I’ll open the book and read the first few pages. If I’m not bored, I’ll buy the book. So, to satisfy readers like myself, I have to make sure that those opening pages really sing.

In my critique group a few weeks ago, a member of the group brought in his third revision of his chapter one and he sighed — with a smile — saying he didn’t think it would be his last revision. No, it won’t be. But that’s ok. It’s part of the process and part of the journey of writing the story. As I wrote all those chapter ones that eventually got cut, I learned about the characters. I now know more about the characters than what’s in the final book, and I think that’s the way it should be.

So, if you’re on your third and fourth version of your chapter one, don’t worry, you’ll find the perfect opener, even if it takes a few more drafts. The important thing is to keep trying.

How’s your writing or revising coming?

Write On!

The only real antagonist is the protagonist herself.

1) Draw a bubble in the middle of a piece of paper. Write the protagonist's deepest held belief, the one that prevents her from having that which she wants more than anything else in the world. Or do this exercise on yourself to determine what's blocking you -- I'm not good enough, I'm not smart enough, I don't do enough -- pick one, create one, we've all got them.

2) Spiraling out from the bubble, create other bubbles each with an external antagonist that these deepest held beliefs attract -- accidents, bad men, addictions, drama, dead-end jobs, half-finished projects, arguments = conflict, conflict, conflict -- blockage, blockage, blockage... walls that keep the protagonist from achieving her goal(s).

He was balled up, resistant, bitter, deeply resentful and so tight he could barely speak, ready to take offense, full of self-pity = a mess.

Came around to see how the experience (our plot consultation) could work in his benefit. (He didn't stand a chance -- I know what I'm doing and I've worked with so many just like him...)

I give him huge credit for not falling deeper into victimhood. He arose out of the muck long enough to shine.

We'll see how it goes... Wish us luck...

Think of the CRISIS, which generally occurs around 3/4 into the entire project, as the ANTAGONIST'S CLIMAX, or where the antagonists prevail.

OR

The CRISIS is the PROTAGONIST'S moment of truth, where afterwards nothing is ever the same.

OR

In the CRISIS, the PROTAGONIST has a breakdown that leads to a break through.

Sue--

I had completely forgotten about "self sabotage" even though that is the main villain in my own life.

Thanks for a great post. I don't usually do fiction, but who knows...you may have inspired me to write a short story.

A couple "NATURE" villain books: HATCHET--nature is a beast in that book to Brian the main character and THE PERFECT STORM--of course! :) Great ideas, here, Sue.

Sioux,

Self-sabotage is the villain in my current Work-in-progress so it was prominent in my thoughts right now.

Margo,

The Perfect Storm. Of course! I always think of Hatchet but now I have a second example. Thank you!

--SueBE