new posts in all blogs

Viewing Blog: George Shannon - Children's Author, Most Recent at Top

Results 1 - 25 of 115

Picture Books

Essays * Reviews * Critique Services

Statistics for George Shannon - Children's Author

Number of Readers that added this blog to their MyJacketFlap: 2

THE WORLD IN 32 PAGES: PICTURE BOOKS THEN, NOW & ALWAYS

This past weekend I was grateful to be one of the speakers at Wisconsin’s SCBWI conference held in Racine, Wisconsin. As such conferences usually are, it was a time of little sleep and a time of consuming mega-vitamins. Imagine, two days of not having to explain why you want to write for children. Imagine, two days of joyfully talking our particular shop.

In my presentation Friday evening I referred to many books. I promised those in attendance that I would post that bibliography on this blog. And, as time permits, I will try to post bits and pieces from my talk.

Thanks to all in Wisconsin who attended the conference. My plane flight home was a flurry of new book ideas and how to make some old projects better.

Related Bibliography

Ahlberg, Allan. THE ADVENTURES OF BERT. Illus. by Raymond Briggs. Farrar, 2001.

Bader, Barbara. AMERICAN PICTUREBOOKS: FROM NOAH’S ARK TO THE BEAST WITHIN. MacMillan, 1976.

Bright, Robert. GEORGIE. Viking, 1944.

Burton, Virginia Lee. MIKE MULLEGAN AND HIS STEAM SHOVEL. Houghton, 1939

Donaldson, Julie. WHAT THE LADYBUG HEARD. Illus. by Lydia Monks. Holt, 2010.

Goffstein, M.B. GOLDIE THE DOLLMAKER. Farrar, 1969.

Gorbachev, Valeri. WHAT’S THE BIG IDEA, MOLLY? Philomel, 2010.

Hesse, Karen. THE CATS IN KRASINSKI SQUARE. Illus. by Wendy Watson. Scholastic, 2004.

Isol. IT’S USEFUL TO HAVE A DUCK / IT’S USEFUL TO HAVE A BOY. Groundwood, 2007.

Johnson, Crocket. HAROLD AND THE PURPLE CRAYON. Harper, 1955.

Katz, Jill. GALEN’S CAMERA. Illus. by Ji Sun Lee. Picture Window, 2006.

Mack, Jeff. FROG AND FLY: SIX SLURPY STORIES. Philomel, 2012.

Marcus, Leonard, ed. DEAR GENIUS: THE LETTERS OF URSULA NORDSTROM. HarperCollins, 2000.

Moore, Nancy. THE UNHAPPY HIPPOPOTAMUS. Illus. by Edward Leight. Vanguard, 1957

Muntean, Michaela. DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! Illus. by Pascal Lemaitre. Scholastic, 2006.

Rathmann, Peggy. RUBY THE COPYCAT. Scholastic, 1991.

Rosenthal, Amy Krouse and Tom Lichtenheld. DUCK! RABBIT! Chronicle, 2009.

Scarry, Patsy. THE BUNNY BOOK. Illus. by Richard Scarry. Golden Press, 1955.

Scarry, Richard. RABBIT AND HIS FRIENDS. Golden Press, 1953.

Schwartz, Roslyn. THE MOLE SISTERS AND THE RAINY DAY. Annick, 2002.

Shaw, Charles G. IT LOOKED LIKE SPILT MILK. Harper, 1947.

Stein, David Ezra. POUCH! Putnam, 2009.

Thomas, Jan. A BIRTHDAY FOR COW! Harcourt, 2008.

Winter, Jeanette. SEPTEMBER ROSES. Farrar, 2004.

Voice as Character

II of III

For many, one of the challenges of writing is making sure each character has his own unique voice. Who hasn’t received a rejection that referred to our “puppet” or “cardboard” characters? Attending to the body and physicality of our characters can help.

An improv theater exercise has each student walk across the room with a different part of his body leading the way. Try it. Walk across the room with your chin leading the way. Then, with your right shoulder leading the way. By the time the student gets to the other side of the room the way he carries his body has begun to create a particular voice that is not the author’s own.

How does a four-year-old walk across the room? How does an exhausted father walk across the room? Body contributes to voice.

Another way to explore voices is to sink into images (even caricatures) of different people. William Steig’s drawings done long before he thought of SYLVESTER AND THE MAGIC PEBBLE can help our minds play and discover.

Given their body posture and facial expression, how does each of the following characters express their reaction to the scene next to them?

The differences in each character’s response is what makes them unique and interesting.

Bibliography

THE STEIG ALBUM by William Steig. Duel, Sloan and Pearce, 1953.

![]()

Voice as Character

I of III

In many ways voice comes down to character whether we are referring to characters in a story or the author/narrator telling the story. Voice is communication and the desire for connection between people. This connection may be face-to-face or leap over years and miles through reading.

A character’s dialogue and action are guided by back-story, but primarily by her immediate wants or needs of the other characters. If a character has no needs or wants why is she in the story? So…what do we, as writers, want or need from our readers? What does our narrator’s voice reveal about us?

As writers and storytellers our primary “want” is capturing and keeping the attention and emotions of our audience. Even if our desire is to do something supposedly more important than keeping their attention such as teaching them something we need answer this reality: How can you teach or inform anyone unless you have their attention? The vital next question is: What are we doing to achieve that “want” of keeping their attention? Volume? Tone? Attitude?

If we encounter resistance to achieving our want in life, we eventually learn that the best tactic is to try another approach. Then another and another. As picture book writers we want the same toolbox of approaches. And, to always being aware of what our storyteller’s voice reveals about us. Warm? Comical? Demanding? Bossy? Scolding? Condescending? Playful? Challenging? Most of all, is it a voice eager to share an experience with an equal?

By:

George Shannon-Author,

on 1/26/2012

Blog:

George Shannon - Children's Author

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Tips,

Picture Books,

creative process,

Writing Picture Books,

Kevan Atteberry,

FRANKIE STEIN,

Tish Rabe,

Illustrating Picture Books,

Josie Bissett,

TICKLE MONSTER,

Lola M Schaefer,

LOTS OF LETTERS,

Add a tag

Illustrators: Responding to the Text

Kevan Atteberry

#1. What elements of a manuscript first capture your attentions? Plot? Language? Imagery? Tone? Sound? Theme?

Kevan

Obviously, all of those things play a part in choosing to accept a manuscript, with a light edge given to Plot and Tone. The story has to engage me. It must be fun, hopefully funny, and when you finish it feels complete. (And as a note, if the tone is odd or bordering on irreverent, I jump at the opportunity. But even above the elements you list, I think a strong, likeable character is the thing that most often says, “To this!” Though I love most genres of picture books, the ones that stand out for me, the kind I like to illustrate are character-driven. I want characters that endear themselves to the reader. Characters with strong established personalities in the text alone, but that I get to flesh out visually. Maybe add my own traits or peculiarities to.

#2. What elements of a manuscript inspire your choice of style, line, and palette? For example, your illustrations in FRANKIE STEIN, LOTS OF LETTERS, and BOOGIE MONSTER are at once related, yet still different from one another.

Kevan

To be honest, when I am offered a book, the art director or editor has chosen me because of a style they have already seen of mine. In discussion with them, they will reference a sample illustration and let me know that that is why they’ve asked me to illustrate the book. I’ve had editors and art directors make suggestions on both line AND palette. In TICKLE MONSTER, we changed the palette a couple of times because the publisher had a particular vision. I did so reluctantly, but in the end I was certain that they had made the right choice. I LOVE the palette in TICKLE MONSTER and BOOGIE MONSTER—as do others—and give all the credit to the publisher for that decision.

#3. Is there a picture book text that you would love to re-illustrate? What about the text excites you?

Kevan

If you are talking about a picture book text by anyone, hmmm…let me think. The first book that comes to mind in Mercer Mayer’s, ONE MONSTER AFTER ANOTHER. A charming story with lovely, fun illustrations and characters. There is no way I could improve on what Mayer did, but I could have the best time creating my own spin on it. GEORGE by Robert Bright would be fun, too. A sweet story with an endearing protagonist. Jose Arugeo’s LOOK WHAT I CAN DO is a wonderful illustration-dependant picture book that would be hilarious to interpret. The text is nearly non-existent so I don’t know if this is a good example of what about the text excites me. It really is just the inanity of the two characters and their one up-manship. And then I’d really love to illustrate a collection. Where the illustrations weren’t linear but rather vignettes. Each illustration standing on it’s own, not linked to the pre

Groundhog Day

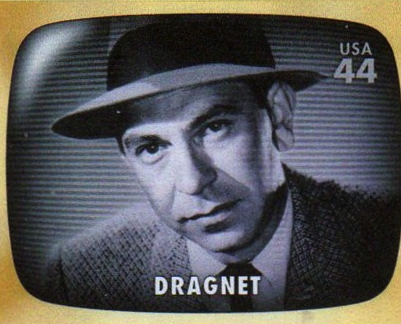

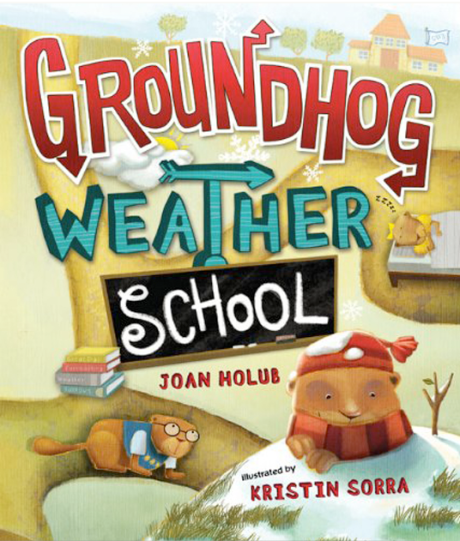

DRAGNET’s detective Jack Webb was famous for supposedly asking for “Just the facts, ma’am.” While that may be advisable for police work, “nothing but the facts” rarely keeps readers engaged. One of the most satisfying developments in recent years has been authors’ ability to blend facts or nonfiction with humor. One of the best is perfect for sharing this time of year–GROUNDHOG WEATHER SCHOOL by Joan Holub. Attempting to impart information about weather, weather forecasting, and groundhogs might have easily induced hibernation amongst readers. But instead, Holub and illustrator Kristin Sorra created a lively, tongue-in-cheek graphic story that’s packed with facts and lots of play.

Find a copy soon. Share it with children, and see what new twists it inspires in your own writing.

GROUNDHOG WEATHER SCHOOL by Joan Holub. Illus. by Kristin Sorra. Putnam, 2009.

Illustrators: Responding to the Text

Craig Orback

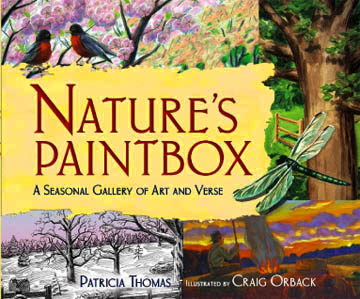

#1. What elements of a manuscript first capture your attention? Plot? Language? Imagery? Tone? Sound? Theme?

Craig

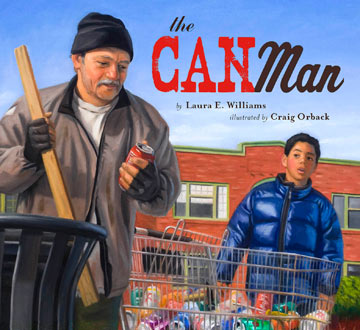

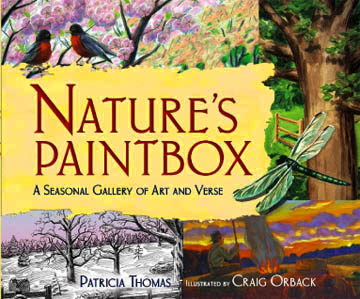

The easy answer would be to say all of the above, which for me is also true. More specifically though I get a lot of enjoyment from the setting, whether it’s historical or not and also the characters. For my picture books THE CAN MAN and NATURE’S PAINTBOX: A SEASONAL GALLERY OF ART AND VERSE both were set in the present which made for a nice change of pace from my typical historical projects. NATURE’S PAINTBOX does not really have a main character; the four seasons were my main characters. Bringing out the fun distinct elements of each season and letting my imagination run wild was really rewarding. It was also my first time illustrating poetry so that brought its own unique challenges. For the book I worked in pen and ink, pastel, watercolor and oil paint to depict each season. Typically an illustrator works in only one consistent medium for each book. For THE CAN MAN it was very character based and deals with serious and topical subject matter like homelessness and wants versus needs as seen through the eyes of a young boy. Tim lives in the city and comes from a family of limited means. He wants a skateboard for his birthday and decides to earn the money himself. I wanted my visuals to be grounded in reality. Living in Seattle at the time I took visual elements from the city but not in any obvious way then put them in the artwork. Traveling around the city with my camera was great fun.

THE CAN MAN

#2. What elements of a manuscript inspire your choice of style, line, and palette?

For example, your illustrations in PAUL BUNYAN, NATURE’S PAINTBOX and THE CAN MAN are at once related, yet still different from one another.

NATURE'S PAINTBOX

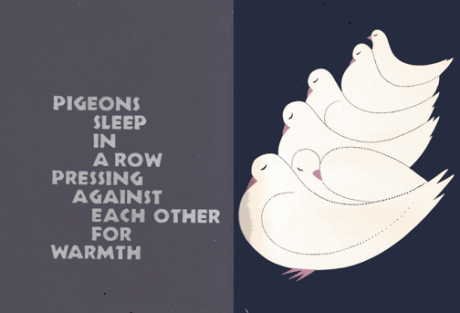

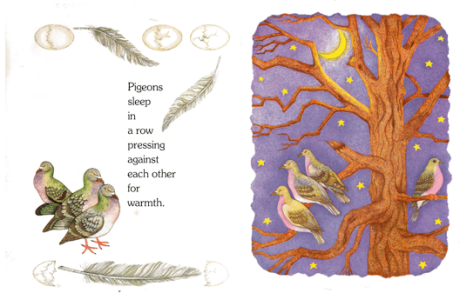

One Picture Book Text: Multiple Interpretations

Charlotte Zolotow

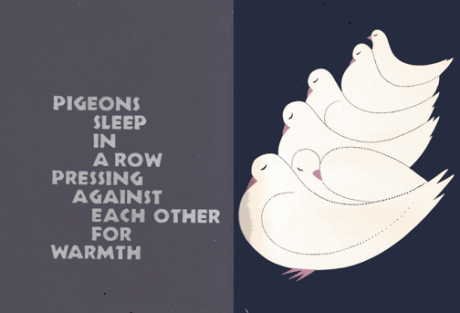

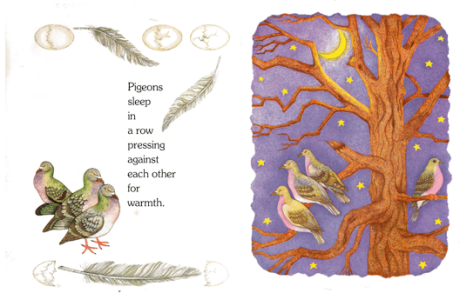

Charlotte Zolotow both edited and wrote many of the outstanding children’s books of the last 60 years. Thanks to the expanse of her writing career, several of her earlier picture books have been re-illustrated in recent years. The differences in styles, trends and printing technology demonstrate once again how many ways there are to interpret a single picture book text.

pigeons illus. by Bobri

pigeons illus. by Plume

cranes illus. by Bobri

cranes illus. by Plume

As picture book writers, we write to communicate with our young readers, but we also write to communicate with our future illustrators.

Picture Books to Explore

IF YOU LISTEN by Charlotte Zolotow. Illus. by Marc Simont. Harper, 1980.

IF YOU LISTEN by Charlotte Zolotow. Illus. by Stefano Vitale. Running Press, 2002.

ONE STEP, TWO by Charlotte Zolotow. Illus. by Cindy Wheeler. Lothrop, Lee & Shepard, 1981.

ONE STEP, TWO by Charlotte Zolotow. Illus. by Roger Duvoisin. Lothrop, Lee & Shepard, 1955.

THE SLEEPY BOOK by Charlotte Zolotow. Illus. by Vladimir Bobri. Lothrop, Lee & Shepard, 1958.

THE SLEEPY BOOK by Charlotte Zolotow. Illus. by Ilse Plume. Harper, 1988.

THE SLEEPY BOOK by Charlotte Zolotow. Illus. by Stefano Vitale. Harper, 2001.

0 Comments on WRITING PICTURE BOOKS as of 1/1/1900

0 Comments on WRITING PICTURE BOOKS as of 1/1/1900

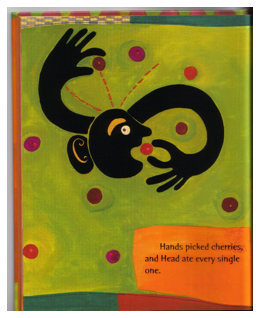

Illustrators: Responding to the Text

Julie Paschkis

#1. What elements of a manuscript first capture your attention? Plot? Language? Imagery? Tone? Sound? Theme?

Language is the first thing that grabs me. But it is hard to pick out any one element; all of the elements work together to create a good story. I respond to a good story first as a reader. When I read something that I want to illustrate I feel a general excitement. I rarely envision specific imagery right away.

I read a text so many times and from so many angles as I am illustrating; I really grow to appreciate a well-written text more and more as I am working on a book.

In your wonderful book WHO PUT THE COOKIES IN THE COOKIE JAR? I responded to the rhythmic qualities of the language and also to the loving message. It felt right to illustrate it in a way that was influenced by the books of my childhood.

2. What elements of a manuscript inspire your choice of style, line, and palette?

For example, your illustrations in THROUGH GEORGIA’S EYES, HERE COMES GRANDMA, and MRS. CHICKEN AND THE HUNGRY CROCODILE are at once related, yet still different from one another.

Before I start drawing at all I let the manuscript percolate in the back of my mind for as long as I can. Gradually I get a sense of what I want the illustrations to look like. It is a combination of intuition and rational decision-making. I will also do research related to the text.

When I illustrated THROUGH GEORGIA’S EYES I read her biography, looked at lots of her paintings, visited her home in Abiquiu and her museum in Santa Fe before starting any sketches. That was the rational part. But I was still stumped for how to approach it. In Santa Fe I went to the folk art museum and saw some Polish paper cuts and made the intuitive leap to illustrate that book as paper cuts. That way I could honor her paintings without trying to paint a Georgia O’Keeffe; translating the medium allowed me to use her imagery in a way that was still mine.

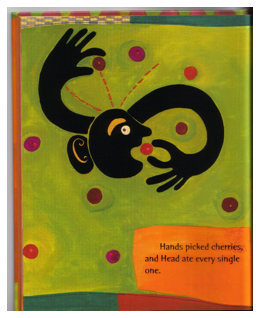

In HEAD BODY LEGS by Meg Lippert and Won-ldy Paye I wanted bright colors and simple shapes intuitively to echo the simple and funny story. Specifically I was inspired by Asafo Flags of West Africa as a way to approach the storytelling. I continued that style in MRS. CHICKEN and in THE TALKING VEGETABLES.

Asafo flag

HEAD BODY LEGS

One Picture Book Text: Two Interpretations

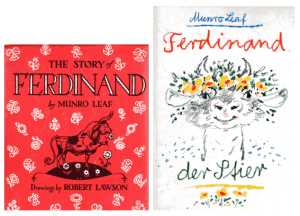

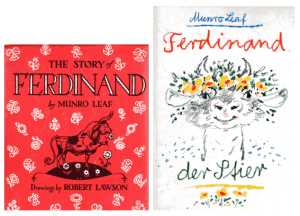

When Richard Jesse Watson mentioned FERDINAND THE BULL as the picture book text he’d most like to illustrate I hurried to my bookshelves. I have loved FERDINAND since childhood, and some 40 years ago found a German edition illustrated by Werner Klemke.

While we’ve grown used to folktales being illustrated or interpreted by a wide range of artists, it is unusual for a modern text to be re-illustrated. Our initial reaction often resembles our response to the remake of a beloved film. “What have they done?” But exploring such examples can be valuable to those of us who write but not illustrate. It helps us understand how two different artists can experience and envision our words and story.

Though this German edition is out of print, we can see all the illustrations thanks to the Internet. Go to YouTube: Ferdinand der Stier.wmv – YouTube.

<www.youtube.cm/watch?v=G8vddifa1RM>

Enjoy!

Picture Books Discussed

Leaf, Munro. FERDINAND THE BULL. Illus. by Robert Lawson. Viking, 1938.

Leaf, Munro FERDINAND DER STIER. Illus. by Werner Klemke. Transl. by Fritz Guttinger. Parabel Verlag, Date Unknown.

Illustrators: Responding to the Text

After 100 posts blog about picture books, I’m yearning to add other voices. I’ve begun to invite illustrators to answer a few questions about how they respond, relate to, and expand a text they didn’t write themselves. In other words, how do illustrators respond to our manuscripts.

Our first illustrator is Richard Jesse Watson.

#1. What elements of a manuscript first capture your attention? Plot? Language? Imagery? Tone? Sound? Theme?

What a clever question, George. The first thing that captures my attention is the envelope (that is, if it arrives by mail). Things are changing so fast, that the traditional form of mail may be obsolete by the time you get this response. But I’m sure you remember what mail is even though your readers may not. So, to clarify for you readers of George, I was referring to Medieval Mail, or Snail-Mail, or Analogue Word Transfer, or in other words, The Hob-Nobbing of Wizards, using paper and ink made from walnuts. . What was the question? Oh, right, am I intrigued by envelopes? In a word, yes. The fact that someone sent me an envelope with yummy words or story, is so exciting. And the possibility of illustrating those words sends me into a little orbit. An orbit of imaginings. Ahhh, what might I do with these words?

The tone of the words is what hits me at first. Does the writer grab me by the…uh, medulla. Am I intrigued? Is this writing fresh? Not like, Slap!!>>fresh, but original voice fresh. Then the other things follow: Imagery. Sound. Plot. Theme. Etc.

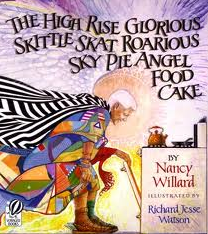

#2. What elements of a manuscript inspire your choice of style, line, and palette?

For example, your illustrations in THE LORD’S PRAYER, THE HIGH RISE GLORIOUS SKITTLE SKAT ROARIOUS SKY PIE ANGEL FOOD CAKE and THE MAGIC RABBIT are at once related, yet still different from one another.

The final emotional delivery of the manuscript will inspire me to want to illustrate the story or not. As an illustrator, forsooth, even as a reader, I want to be led down a garden path; hopefully one with pretty flowers, and ripe fruit. Some lizards would be cool. Maybe I could be wearing a Davy Crockett hat. It sure works if you surprise me with your thoughtfully arranged words, maybe startle me! Amuse me? It does me-the-reader wonders if you can emotionally nudge me, or even wrench me in some lingering way. We could also just have fun. “Good clean fun,” to quote Bill Murray.

But all that to say, a good story will compel me to experiment with medium in some unique way. My goal is to be true to the text but to explore the text and as N. C. Wyeth said, “To paint between the lines.”

THE NIGHT BEFORE CHRISTMAS by Clement C. Moore

#3. Is there a picture book text that you would love to re-illustrate? What about the text excites you toward doing this?

I would love a chance to re-illustrate THE STORY OF FERDINAND by Munro Leaf. Actually it is so perfect the way it is. Forget I said anything. Ixnay on the what I sai

Picture Books and the Short, Short Story

II of II

Illustration by Ethan Long. BIRD AND BIRDIE

The best and best-known picture book short, short stories feature friends and siblings. It only makes sense because an established relationship lets one “cut to the chase” and story. George and Martha are two of the best-known pals and hippos in literature. James Marshall captures and explores their relationship through seven collections of short stories.

Whether one labels them as vignettes or sketch stories, Marshall’s moments revealing the lives of George and Martha engage and entertain. They also linger in the reader’s memory. Who hasn’t been caught putting the equivalent of split pea soup in a shoe in the hopes of not offending the cook?

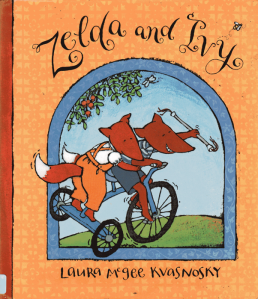

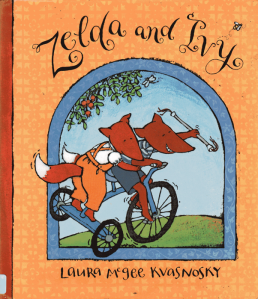

No matter how long or fat the great American novel may be, it still comes down to a series of brief and personal moments. Such moments are the heart of GEORGE AND MARTHA and Laura Kvasnosky’s ZELDA AND IVY. Where George and Martha are chosen friends, Zelda and Ivy are siblings who are expected to act like chosen friends. This common and complex relationship gives author Kvasnosky a rich and varied playground.

While each short story in ZELDA AND IVY feels complete in itself, the full collection brings both a deeper connection with the characters and a deeper connection with reality. Zelda may eventually have a moment of compassion, but she will always be the older sister who makes sure she gets to do everything first.

Ethan Long’s BIRD & BIRDIE is different in that it focuses on the creation of a relationship. And, like all new relationships, BIRD & BIRDIE is series of miscommunication, upsets, and opportunities for empathy.

Some people write long stories. Others write long stories by creating a mosaic of moments. That option is our opportunity. On those days you can’t think of a story or plot, relax and return to the moments of you life. As James Marshall, Laura Kvasnosky and Ethan Lang prove, those moments might well be a collection of stories just waiting to be shared.

Picture Books Discussed

BIRD AND BIRDIE IN “A FINE DAY” by Ethan Long. Tricycle Press, 2010.

GEORGE AND MARTHA by James Marshall. Houghton Mifflin, 1972.

ZELDA AND IVY by Laura McGee Kvasnosky. Candlewick, 1998.

0 Comments on Short Stories in Picture Books as of 12/5/2011 10:49:00 PM

0 Comments on Short Stories in Picture Books as of 12/5/2011 10:49:00 PM

Picture Books and the Short, Short Story

I of II

In the early 1970s Arnold Lobel and James Marshall (who became good friends) each started what became a series of short story collections about two good friends. FROG AND TOAD ARE FRIENDS* and GEORGE AND MARTHA brought a new possibility to the picture book. Rather than a single narrative arc based in plot, one could also focus on characters and relationship in a series of encounters. Another way to look at short stories, be they by Chekhov, Cheever, Marshall or Kvasnosky, is that they are snapshots of human behavior. In the end, every novel and every life is an album of such snapshots.

Within the term short story there are a variety of subgenres and fluid definitions of each. There is no rule that one must not blend these categories, but it is valuable to know their differences and possibilities.

Flash Fiction

Primary characteristics are extreme brevity, fast pacing from one plot point to the next, and less developed characters. Many sight Aesop as the first flash fiction writer.

Eve Feldman’s BILLY & MILLY, SHORT & SILLY brings extreme flash fiction to picture books. These 13 stories are each told in only three or four words. For example:

Stoops. Hoops. Scoops. Oops.

Stoops” establishes setting (front steps). “Hoops” establishes activity (shooting hoops). “Scoops” establishes second character’s activity (eating an ice cream cone). And “Oops” proclaims conflict (rogue basketball ruins the ice cream cone). Tuesday Morning’s illustrations are vital to the reader’s grasp of these very mini stories because they clarify setting, characters and action.

Another of Feldman’s stories manages to establish setting, character, conflict and resolution in only four words.

Bunk. Trunk. Skunk. Clunk.

Whether you’re writing picture book short stories or a single story picture book try a draft using only 5 to 10 words. You’ve got nothing to lose, and it might help you find the primary beats of your story.

Illus. by Tuesday Mourning BILLY & MILLY

Next spring brings another example of cracker-jack flash fiction in picture book form. Jeff Mack’s forthcoming FROG AND FLY: SIX SLURPY STORIES is a playful delight. I read the F & Gs at my local bookstore, and can’t wait to by my copy come March.

Coming next: The “sketch story”, the “vignette”, plus George & Martha, Zelda & Ivy, and Bird & Birdie.

*Because FROG AND TOAD ARE FRIENDS is an early reader

Are You a Good Date?

Edward Lear

One of my favorite quotes about writing refers to two elements we rarely associate with picture books, but I believe they are vital to our writing. #1 Kurt Vonnegut. #2 Dating. The quote comes via John Casey who reports,

“Kurt Vonnegut used to say to his class at Iowa, ‘You’ve got to be a good date for the reader.”

What’s a good date? An equal. Someone engaged in the moment and conversational. Someone who fosters a give and take. Sparks interest. Someone who is open and able to reveal what they have in common. Honest. Gently flirtatious.

Are you a good date for your reader? Are you making sure to work toward keeping his interest and attention? Are you being honest, or pretending to be something you’re not?

Like fish in the sea, there are plenty of books. If we want to make sure our reader wants to see us again we’re wise to capture both their head and heart.

Breaking Through the Fourth Wall

Ferris Bueller's Day Off

In theater and film stories are typically performed inside four walls. The fourth wall is the front of the stage facing the audience. While it is not a real wall, audience and actors agree to treat it as a wall with a very large peephole. Audience and characters do not acknowledge that the other exists. It is a vital part of the suspension of disbelief. Well, most of the time. The same is true for picture books. Again, most of the time.

The movie FERRIS BUELLER’S DAY OFF is one of the best-known examples of a character acknowledging and speaking directly to the audience. Many interactive or concept picture books do this by asking questions like “Can you find?” or “Whose feet are these?” A few picture books break the fourth wall to an even greater extent by having the reader actually become part of the story. Think of it as THE PURPLE ROSE OF CAIRO in reverse!

Michaela Muntean’s DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK views the reader as the second character in the story. The reader becomes the antagonist by simply opening the book and turning the page. We (the reader) don’t mean to cause trouble, we’re just curious to follow the story. Who can’t relate to innocent curiosity getting us into trouble?

THE PURPLE KANGAROO by clever Michael Ian Black not only makes the reader a part of the story. It makes the reader the butt of the joke.

The book that first brought Don and Audrey Wood to everyone’s attention puts yet another spin on breaking the fourth wall. THE LITTLE MOUSE, THE RED RIPE STRAWBERRY, AND THE BIG HUNGRY BEAR gives the reader the role of a concerned observer speaking from the audience. We do what every audience member wishes he could do, warn the characters in the story.

Why not take a playful chance, and see if you can make your reader an active part of your next manuscript.

P.S. For an interesting look at other forms of metafiction in picture books visit Philip Nel’s:

“Metafiction for Children: A User’s Guide – YouTube”

Books Discussed

DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK by Michaela Muntean. Illus. by Pascal Lemaitre. Scholastic, 2006.

THE LITTLE MOUSE, THE RED RIPE STRAWBERRY, AND THE BIG HUNGRY BEAR by Don & Audrey Wood. Illus. by Don Wood. Child’s Play 1984.

THE PURPLE KANGAROO by Michael Ian Black. Illus. by Peter Brown. Simon & Schuster, 2010.

3 Comments on WRITING PICTURE BOOKS, last added: 11/8/2011

3 Comments on WRITING PICTURE BOOKS, last added: 11/8/2011

Thanks for sending this out! How wonderful to have gone and been able to talk shop and enjoy. Recently read a book you may like, that is if you haven’t already discovered it. It is Virginia Lee Burton – A Life in Art by Barbara Elleman. If you haven’t come across it yet, it is a gem. Looking forward to any other informational emails you send out. Thank you – Cara

Wonderful to read a new blog entry. I’ve missed them. Thank you for sharing your bk list with us. Looking forward to reading more about your presentation in Wisconsin