When interviewed by a reporter from the Wall Street Journal regarding Thomas Ligotti, Jeff VanderMeer was asked: "Can Ligotti’s work find a broader audience, such as with people who tend to read more pop horror such as Stephen King?" His response was, it seems to me, accurate:

Ligotti tells a damn fine tale and a creepy one at that. You can find traditional chills to enjoy in his work or you can find more esoteric delights. I think his mastery of a sense of unease in the modern world, a sense of things not being quite what they’re portrayed to be, isn’t just relevant to our times but also very relatable. But he’s one of those writers who finds a broader audience because he changes your brain when you read him—like Roberto Bolano. I’d put him in that camp too—the Bolano of 2666. That’s a rare feat these days.This reminded me of a few moments from past conversations I've had about the difficulty of modernist texts and their ability to find audiences. I have often fallen into the assumption that difficulty precludes any sort of popularity, and that popularity signals shallowness of writing, even though I know numerous examples that disprove this assumption.

When I was an undergraduate at NYU, I took a truly life-changing seminar on Faulkner and Hemingway with the late Ilse Dusoir Lind, a great Faulknerian. Faulkner was a revelation for me, total love at first sight, and I plunged in with gusto. Dr. Lind thought I was amusing, and we talked a lot and corresponded a bit later, and she wrote me a recommendation letter when I was applying to full-time jobs for the first time. (I really need to write something about her. She was a marvel.) Anyway, we got to talking once about the difficulty of Faulkner's best work, and she said that she had recently (this would be 1995 or so) had a conversation with somebody high up at Random House who said that Faulkner was their most consistent seller, and their bestselling writer across the years. I don't know if this is true or not, or if I remember the details accurately, or if Dr. Lind heard the details accurately, but I can believe it, especially given how common Faulkner's work is in schools.

And this was ten years before the Oprah Book Club's "Summer of Faulkner". I love something Meghan O'Rourke wrote in her chronicle of trying to read Faulkner with Oprah:

Going online in search of help, I worried about what I might find. What if no one liked Faulkner, or—worse—the message boards were full of politically correct protests of his attitude toward women, or rife with therapeutic platitudes inspired by the incest and suicide that underpin the book? But on the boards, which I found after clicking past a headline about transvestites who break up families, I discovered scores of thoughtful posts that were bracingly enthusiastic about Faulkner. Even the grumpy readers—and there were some, of course—seemed to want to discover what everyone else was excited about. What I liked best was that people were busy addressing something no one talks about much these days: the actual experience of reading, the nuts and bolts of it.We often underestimate the common reader.

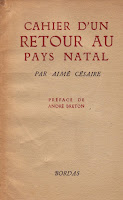

Which brings me to another anecdote. When I was doing my master's degree, I fell in love with the poetry of Aimé Césaire, particularly the Notebook of a Return to the Native Land. I was at Dartmouth, so our instructor (who later very kindly joined my thesis committee) was an expert on Césaire and had spent time in Martinique with him. I asked him how it was possible for someone who wrote such complex, thorny stuff to have become so popular among not just individuals, but whole groups of people who had not had great access to education and who may have little knowledge of modernist poetry. He said something to the effect of: Difficulty depends on what you expect, and what your context for understanding is. If your experience and perception of the world fits with that of the writer, then the form a great writer finds to express that experience and perception is going to be accessible to you, or at least accessible enough to allow you some level of basic appreciation from which to build greater appreciation. He said he'd seen illiterate people deeply, deeply moved by Césaire's poetry when it was read aloud. He knew countless people who had memorized whole passages. He himself fell in love with Césaire's work when he was at school in England, far away from home, and his roommate, who was from the Caribbean, had written (from memory) passages of the Notebook on the ceiling of their dorm room so that it would be the last thing he saw each night and the first thing he saw each morning. Césaire may not have been an international bestseller, but his popularity is real, and is a kind any writer would be humbled by and grateful for.

I've been reading around in Modernism, Middlebrow, and the Literary Canon: The Modern Library Series 1917-1955 by Lise Jaillant, which includes a fascinating chapter on Virginia Woolf. While the information about how Orlando sold well from the beginning is familiar to anyone who's read much biographical material about Woolf, far more interesting and revealing is the discussion of the fate of Mrs. Dalloway in the Modern Library edition in the US. This actually has a lot of parallel to Ligotti becoming part of the Penguin Classics line, for, as Jaillant writes, "The Modern Library was the first publisher's series to market Woolf as a classic writer.") During and immediately after World War II, the Modern Library edition of Mrs. Dalloway sold quite well, at least in part because of its use in schools:

In 1941-42, Mrs. Dalloway sold four copies to every three of To the Lighthouse. This trend continued after the war, a period characterized by a huge rise in student enrolments, and an increasing number of courses on twentieth-century literature. The Modern Library edition of Mrs. Dalloway was often adopted for use in survey courses at large universities. In 1947, for example, one professor at the University of Wisconsin ordered 1,400 copies of Mrs. Dalloway, and another one at the University of Chicago ordered 800 copies of the same book. In the 1940s, Mrs. Dalloway sold around 2,800 copies a year. If we look at the twenty-year period from 1928 to 1948, Mrs. Dalloway sold 61,000 copies.It probably would have gone on like that if the Modern Library hadn't lost the reprint rights to Mrs. Dalloway — Harcourt/Brace had decided to start their own line of inexpensive "classic" editions (Harbrace Modern Classics). Attitudes toward modernist novels had changed, too, as Jaillant says: "...the idea that a modernist work could also be a bestseller was increasingly contested in the 1940s and 1950s, at the time when modernism was institutionalized in English departments. The popularity of Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse was soon forgotten, as modernism came to be seen as a difficult movement for an elite" (102). (I don't know how well Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse sold between 1948 and the 1970s. By 1975 or so, Woolf was championed by feminist scholars and started on her way to becoming one of the most frequently studied writers on Earth. I've been told that sales of her books were pretty dismal by the end of the 1960s, and that most of her books were out of print, but that may be more a matter of memory and perception than fact. This is something I need to look into further.)

Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse are not easy books. They aren't The Waves, but they're still nothing anyone would ever describe as "easy reads". (The Waves did very well at first, since it was Woolf's first novel after Orlando, selling just over 10,000 copies in the first six months in the UK, but it then dwindled to only a few hundred copies sold in the UK in the next six months, according to J.H. Willis) The various editions of Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse still sell well today, and are not only beloved by English professors, but by all sorts of common readers who come upon them in a class or just in the course of ordinary life and find something in the pages worth wrestling with. Even The Waves is deeply loved by many people, and it's one of the most difficult of modernist texts. But it, like all of Woolf's best writing, does things to you few, if any, other books do.

This gets back to what Jeff said about Ligotti: "he’s one of those writers who finds a broader audience because he changes your brain when you read him." If readers trust that the effort of learning to read a strange or difficult writer is worth it, then they may put forth that effort. Brains are stubborn, and sometimes resist being changed. I threw Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom! across the room three times when I first read it. Eventually, I put in enough work that the book was able to teach me how to read it. And then we were in love, eternal love.

There's no sure pathway to such things, for writer or reader, and of course there are plenty of marvelous, difficult writers whose work has never succeeded much, if at all. In many cases, success (eventual or immediate) is a matter of packaging, and sometimes that packaging is deceptive. Look at Faulkner, for instance. His reputation among critics and scholars in the 1930s was generally high, but the only book that sold well was his sensationalist pulp novel Sanctuary. The Southern Agrarians (and, later, New Critics) rather oddly reconfigured and tamed Faulkner, downplaying and flat-out misinterpreting and misrepresenting the darkness, ambiguity, and weirdness of his work. The biggest successes at this were Malcolm Cowley, who gave up left-wing politics around the time he started editing the various Viking Portable editions of major writers, and Cleanth Brooks, who palled around with the Agrarians and helped create and promulgate New Criticism. Cowley's Portable Faulkner presented a simplified and superficial vision of Faulkner, while Brooks's studies of Faulkner provided (mis)interpretations of his works that made Faulkner seem like an unthreatening nostalgist, a writer palatable both to the more conservative of Southern critics and the blandly liberal Northern critics. The simplified/sanitized/superficial view of Faulkner led to a Nobel Prize and quick canonization. Faulkner himself even seems to have bought into the new, cuddly presentation — his last great work was Go Down, Moses in 1942, with nothing written after it of comparable quality, depth, or strangeness. Some of the later books and stories are quite readable, but they're relatively shallow and often cloying. Partly, or perhaps even fundamentally, this was the result of chronic alcoholism catching up to Faulkner, but it was also a matter of his having apparently decided to write what his growing audience expected of him.

Still, even with all its simplicities and superficialities, the canonization of Faulkner allowed his work to stay in print, to receive wide distribution, and to be read. Many people probably didn't read past the Agrarian/New Critic view for decades, but I expect many others did. (Especially people influenced by existentialism, who would have seen the darkness and even nihilism within the best writings. For a long time, and maybe still, people outside the US academy saw a deeper, stranger Faulkner than US professors and critics.) The books were available, the words could be read.

The lesson here, if there is a lesson, is that literary history is complex and doesn't easily boil down to simple oppositions like popular vs. difficult. And that so much depends upon how a book is sold to readers, and how readers have the opportunity to discover a book, and what they expect from it and hope from it, because what they hope and expect from a book will determine how they find their way into it, and it will further determine whether they stick with it when the way in proves challenging. If writers, publishers, critics, and teachers respect readers as intelligent beings and keep high expectations for them, some great things can happen sometimes, especially if a "difficult" book is able to stay in print for a little while, to lurk on shelves until it is discovered by the readers who need it, the readers ready to help its words live.