I mentioned William Plomer in passing when discussing my summer research on Virginia Woolf. Thanks to the wonders of Interlibrary Loan, I was recently able to read his fourth, and perhaps least-read (which is saying something!) novel, The Invaders. It's an odd book, one that sometimes feels a bit under-cooked, with an ending that seems to me perfunctory, forced, and utterly unsatisfying. Yet there are also moments of real artistry and interest, and I've found myself thinking about it continuously since I finished it a week ago.

The Invaders is, among other things, a gay novel, but it doesn't get noted in even some of the most comprehensive studies of gay fiction, and Plomer deserves to be generally better known by scholars of queer literatures. He was not as talented or accomplished a fiction writer as many of his friends in the London literary scene, but his point of view was unique among them, because though he was mostly educated in England, his home until he was in his 20s was South Africa, and then he moved to Japan for a few years, before finally settling in London (though with many excursions elsewhere, particularly Greece). After The Invaders, he wrote only one more novel (and that 18 years later), but he published numerous volumes of poetry, biography, autobiography, etc. Fiction seemed to defeat him eventually. It's unfortunate, because there's a lot in The Invaders to suggest that if he had let down his guard a bit, if he had trusted the characters and stories more, if he had not been so seduced by English propriety, he might have been able to rekindle the creative fury that propelled him originally.

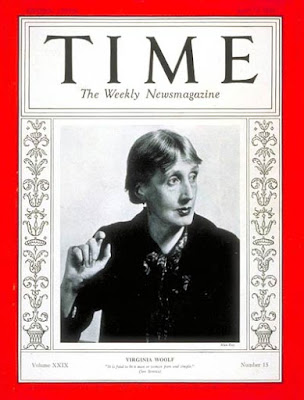

|

| Plomer, 1933. Photo by Humphrey Spender |

Plomer's first novel, Turbott Wolfe, written in his late teens, remains the most famous of his books today, and was championed by Nadine Gordimer. There's a brash energy to it that disappears from a lot of his later fiction, and it's more aesthetically daring than what he wrote subsequently. Sado, his next novel, tells the story of Europeans in Japan. It's more subdued and oblique than Turbott Wolfe, but also more openly about homosexual desire, though "openly" here is a relative term, as all the homosexual desire, though not difficult to see, is implied. Plomer's next novel, The Case Is Altered, is a sort of novel of manners that becomes a tale of murder (as, I would submit, all novels of manners ought). It was a significant success, helping to keep the Hogarth Press afloat during the 1930s. In Leonard and Virginia Woolf as Publishers, J.H. Willis, Jr. describes the novel succinctly, noting first that it was based on a gruesome murder in Plomer's own boarding house:

Although the crazed butchery of Beryl Fernandez by her husband in front of their small child is the shocking climax of the novel, it does not constitute the main interest in the book. Plomer's first English novel explores in depth the traditional subject of a respectable rooming house on its way down, but the most intense aspect of the novel is the thinly disguised homosexual relationship that develops between the Plomer-like hero, Eric Alston, and Willie Pascal [note the initials], the extroverted, working-class brother of Alston's girlfriend Amy. It was Plomer's most overt statement of his sexual identity in fiction and went beyond the lyrical eroticism of Sado. (203-204)By the time The Case Is Altered became a success in 1931, Plomer was well established in England's literary circles. At the end of the '20s, he'd become friends not only with the gay male writers of his own generation (e.g. W.H. Auden, John Lehmann, Stephen Spender, and Christopher Isherwood), but also with E.M. Forster, who remained a close, lifelong friend.

And then in 1933 Plomer changed publishers, moving with a short story collection, The Child of Queen Victoria, from the Hogarth Press to the more mainstream Jonathan Cape (with whom he would soon become an employee, leading to his role in Cape's acquisition of his friend Ian Fleming's James Bond novels). The next year, Cape released The Invaders, a story of a middle-class London family's relations with a variety of mostly working-class people. (I will summarize and quote from a lot of the book as I go on, given how rare it is.)

The novel doesn't really have a plot, just encounters, and yet there's a momentum and tension to it all, because it always feels that one of these encounters could go horribly wrong at any moment. That tension is mostly false. Characters do encounter disappointments, misunderstandings, frustrations, anger, and, in the end, get involved with a robbery ... but the consequences for the middle-class family that we are set to identify with are almost nil, and even most of the working-class characters end up pretty well, if occasionally bruised and disillusioned.

The "invaders" of the title are the working-class characters, and one of the ways the novel is interesting is in its portrayals of class difference. The main character is Nigel Edge, a veteran of World War I (and badly injured in the war), who works at a tea importer/distributor and lives with his cousin, Frances, and her father, Uncle Maurice, who had been a colonel in the Boer War. Uncle Maurice has strong ideas about class differences and considers anyone from the working classes to be congenitally dishonest. Class differences seem to him eminently reasonable and necessary. Nigel and Frances are no revolutionaries, but their faith in the class system is not especially strong, and Nigel especially is drawn to the working classes. In some ways, this is clearly because by spending his time among people of a lower class, he's able to feel better about himself: compared to theirs, his life is comfortable, prosperous, and well-ordered. But his life is neither interesting nor attractive, and he is a failure as a conventional man: he lives with his cousin and uncle rather than a wife, he has no children, and though he fought and was wounded in the war, his tastes and mannerisms are far from virile.

Interestingly, the novel does not begin with Nigel's point of view. The first chapter is a lovely, panoramic description of London that seeks to establish the variety of people and sites, the numerous possibilities of interclass contact, particularly around the Marble Arch. Here's the first paragraph:

Gleaming and stinking, gliding and vibrating, the traffic swerves and jostles round that squat anachronism, the Marble Arch. This was Tyburn. Butchery, cries of agony, steaming entrails, calm courage, Perkin Warbeck and Claude Duval, have helped to prepare the scene. Go this way, there is a nunnery; go that way, there is a public house; go down there, and you will come to rich people's houses. You aren't a nun, you don't drink and will never be rich, so for you there is a large hotel, a large cinema, and behind those hollow cliffs some sort of comfort and amusement may be bought. And over there, beyond the wheels and windows of the traffic, is the grass and the comparatively open air, the common heritage of all of us corpuscles who are carried from time to time through this artery of the great body of London, or held there for a while with the policeman on point-duty, the beggar who scratches himself at the gate, or the commissionaire in gold braid at the foot of the cliff. Here is somebody with a grudge, here is somebody whistling, the old lady is about to light a cigarette, the young woman wears jodhpurs and a monocle, and a pavement artist is arguing with his brother-in-law over the merits of a greyhound.This goes on for a few pages, until the chapter ends with: "Something must be wrong, but something has been and will always be wrong, with the faces round the Arch." The next chapter introduces us to Tony Hart, recently arrived in London from Lancashire. He is starving on the streets, but he rejects charity. He feels watched, judged. One day, he helps a stranger who has fallen on the steps of a tube station. This is Nigel. Tony trusts Nigel for some reason, lets him buy him some food, and Nigel offers to try to find some work for him at Uncle Maurice's house. Soon, we slip into Nigel's point of view, and see him at home with his uncle and cousin. Nigel yearns for a bit of subversion:

"I read in the paper this morning," said Nigel, "that there's an international group which does nothing but smuggle people into countries that won't allow them to come in straightforwardly. They fake passports, provide disguises, teach the elements of conversation in various languages, bribe the captains of coasting steamers, and so on. Of course they do it for profit, but I wouldn't mind doing it for pleasure."Tony comes to clean the windows of the house and meets the new maid, Mavis, herself only recently arrived in the city (seeking to escape a boring rural life, to make her fortune, etc.), and soon enough they fall in love. Eventually, Mavis's brother, Chick, stops by, as he's in the military and based in London. He and Nigel pass each other on the steps, and Nigel is immediately taken with him, even more than he was with Tony. They visit with each other a lot, have long conversations, stare deeply into each other's eyes. (Chick was based on one of Plomer's lovers, a trooper with the Royal Horse Guards.) Tony remains as steadfast and decent as ever, but Mavis is greedy and ambitious, and ends up involved with Tony's felonious brother, Len, an involvement that concludes with a robbery, with Len going back to prison and Mavis realizing the errors of her ways and returning home, where she seems to belong. Nigel's affair with Chick falls apart when Nigel feels that Chick has not entirely honest and has not been paying enough attention to him — Nigel seems to suspect that Chick might prefer being with a woman. (Poor, not-so-bright Chick seems rather blindsided by Nigel's jealousy and his curt dismissal of him.) Nigel goes on holiday to the south of France. He disappears one night, and his proper, married, middle-class friend, Robin, traces him to a seedy bar:

"Why?"

"Oh, simply as a protest against the way the modern world is arranged."

"So you're becoming an anarchist?"

"It looks rather like it, doesn't it?"

"He's only teasing you, father," said Frances. "Don't take any notice of him."

"I'm worried to see him getting more subversive," said the Colonel, speaking of NIgel as if he was not present, "instead of taking things as they are and making the best of them." (33)

The dancing was going on behind a second bead curtain at the end of the room. Together with the stridency of the gramophone could be heard the sibilant steps of the dancers. Robin strolled over to have a look. There were four couples dancing. Two women were dancing together, and so were two men. One of them was Nigel, the other a working man in a blue shirt. Nigel was so engrossed in the dance that he did not notice Robin for a moment or two.Then follows a long paragraph from Robin's point of view — he finds the atmosphere in the place "oppressive and uncomfortable", and the various elements and people combine to "produce a distasteful, an almost horrible effect on him. There was an air of rhythm and ritual, of acceptance and celebration, that made him long to escape" (275-276). Nigel is perfectly happy, and was thinking of spending the night, but decides that he'll go back with Robin and set Yvonne's imagination at rest. The chapter ends:

"Hullo, Robin," he said suddenly.

Robin felt a little uncomfortable.

"I hope I don't intrude?" he said.

"Well, I wasn't expecting you," said Nigel with a smile, "but it's very nice to see you. We'll have a drink."

He came out with his partner, and all three sat at Robin's table. The partner had an amiable face, Robin thought, but rather beady black eyes.

"I came along," he said, "because Yvonne was worried about you. She made me come. I don't think she trusts you to look after yourself."

"What a sweat for you," said Nigel. "I am sorry for dragging you out."

"It's all right. Glad to see you enjoying yourself." (274-275)

"Phew!" said Robin. "It was stuffy in there."This, in many ways, is the climax of the novel. After it, there's fewer than 30 pages left, and they're mostly devoted to tying up loose ends. Nigel returns to London and his job, and he thinks for a moment that he should perhaps marry Frances. (Plomer himself had recently been wondering if he should get married.) He decides not, as their friendship might be ruined, and he clearly isn't really interested in her in the way a husband should be. He wonders if his desire for marriage is a result of the "emancipation of women" and a feeling of the loss of male power and privilege. The thought is not concluded. The brief final scene of the novel begins: "The invaders had gone" (304). Tony shows up at Nigel's apartment (mid-way through the novel, he decided to move out of his uncle's house) to see if the windows need washing. They chat, then the novel ends with Nigel making a proposal:

"I like that place," said Nigel.

"Well, I'll tell you what I'm going to do. I'm going to lend you your fare home. I think it's time you had a holiday. Mind you, I said 'lend', not 'give'. You can pay me back when your ship comes in."It's a strange ending — one in which people return to where they "belong", and in which Nigel has gained a mysterious sense of peace. What is the "phase" of life that has ended? His attraction to working class men? He feels as if he knows where he is ... but where is that? London, his apartment, the modern age? He is no longer possessed with the subversive/anarchistic desire to help immigrants get to London, but instead with the (conservative) desire to help people go home. He is full of hope, but it can't be the hope of a heteronormalized life, because he's rejected that. Somehow, in rejecting Chick, in dancing in a gay bar in Nice, in sending Tony home, he has found the balance and meaning of his life. He is no longer invaded.

Tony's face grew brilliant with pleasure.

As for Nigel, it was a long time since he had felt the wound in his head. He felt calm and resigned, and hopeful about the future. He did not know why he was hopeful, but he felt that a phase of his life was ended. He felt as if he knew where he was. (304).

When The Invaders was published in 1934, Plomer's friends and some of the reviewers tended to refer to its presentation of sexuality as "ambiguous". This is true to some extent, but it would be difficult to argue that Nigel is not a gay man — he is clearly attracted to Tony and infatuated (for a time) with Chick, he goes to the bar in Nice, he's threatened with blackmail (by a lackey of Tony's brother Len). He never quite identifies himself as a homosexual, an invert, a man of the "Oscar Wilde type", etc., nor the does the text ever say that he wants to have sex with the men he is drawn to, but it's not hidden. Where Plomer's narrative reticence in Sado can seem coy, even annoying, in The Invaders it seems to me a useful technique for showing these characters and their world — some of the scenes with Chick are charming, the scene in Nice is marvelous (mostly because of just how comfortable Nigel is there, and how uncomfortable Robin grows), but there is ambiguity, and it's the ambiguity we see in that ending, an ambiguity that seems to defeat a lot of what's going on in the rest of the book (unless we read it ironically, which is certainly possible — after all, the first paragraph of the novel established "you" [which may be us, the readers] as Tony. And indeed, with the story ending, we are being sent home). The chaotic threat of homo-pleasure is defeated and order is restored, with everyone going back to where they belong.

Plomer's quiet approach to writing about gay characters was not in step with the times, as his biographer Peter Alexander noted:

...writers such as Rosamond Lehmann had dealt explicitly with homosexuality, and Plomer's publishers actually encouraged him to be more open about the matter in The Invaders, Rupert Hart-Davis [director of the Jonathan Cape publishing company] writing that the one criticism he had of the manuscript was that Plomer had been vague about the scope of Nigel's relationship with Chick: "You don't say, and hardly even infer, whether they went to bed together or not." But Plomer declined to expand the passage. (194)The overlaps of class and sex in The Invaders are ones that will be familiar to anyone who has read E.M. Forster's Maurice. It's possible, in fact, that Plomer himself had read it when he wrote The Invaders — Forster tended to share the manuscript with gay friends (sometimes as a test of their friendship); Isherwood read it in 1933, and Plomer introduced Isherwood to Forster. (Naming Nigel's conversative old uncle "Maurice" might have been a little in-joke.) But Plomer certainly wouldn't have had to read Maurice to decide on the theme of inter-class relationships, for during this particular era of English gay male history, such relationships were the most common ones upper-class gay men would have, as Alexander notes:

One of the curious features of English homosexuals of the upper class at this period was that as a rule (though with notable exceptions) they did not regard each other as potential lovers. Spender was to remark years later, "It would have been almost impossible between two Englishmen of our class ... Men of the same class just didn't; it would have been impossible, or at least very unlikely." This behavior may have originated in the English public schools in which so many of them had been educated, where a senior boy often chose a younger boy as a "friend", and tended to avoid his equals in the school hierarchy.Plomer wasn't politically committed in the way his friends were, but he detested the English laws regarding homosexual conduct, and he seems to have shared at least some of Nigel's occasionally subversive inclinations. From the time of Turbott Wolfe, he'd seen sex as a solution to political problems, and it's certainly possible that he thought homosex was a path toward dismantling the class system. But he was no class warrior (even if he was more active, in every sense, than Nigel).

Certainly Plomer had always been attracted to his social inferiors, if only because this gave him control over the relationship. ... With the younger writers, Spender, Auden, and Isherwood, the impulse to choose working-class partners was reinforced by left-wing political views. (180)

One of the reasons that The Invaders may have disappeared from even the most inclusive of gay canons is that it was a bit old-fashioned even for its own time. Where writers like Isherwood and Spender delighted in pushing the edges of what was acceptable, Plomer was far more comfortable in a more liminal space.

In a letter to Plomer dated 26 September 1934, E.M. Forster expressed a criticism of The Invaders:

What seems to [be] not satisfactory in the book is a thing which I find wrong in A Passage to India. I tried to show that India is an unexplainable muddle by introducing an unexplained muddle — Miss Quested's experience in the cave. When asked what happened there, I don't know. And you,Forster is insightful here. (More insightful regarding Plomer, I think, than about his own novel.) The Invaders fails to be a great novel at least partly because Plomer couldn't let Nigel become ... something. In the end, his sense of peace rings false because it is so random and so against all the facts the book presented up to that point. If the novel had ended with Nigel and Robin walking out of the bar in Nice — if the last line had been, "'I like that place,' said Nigel", it would have been far more effective, even though lots of loose ends would have still been left untied. But Plomer's instincts (and, perhaps, fears) led him to squeeze Nigel into a form that does not follow from the rest of the book, that makes no sense — that, and not so much Nigel's homosexuality, is the muddle. It's not so serious a fallacy for Forster's work because A Passage to India is actually strengthened by the ability of readers to make their own sense of Miss Quested, but it is a failure for Plomer's novel because while we have enough information to make sense of him as a gay man who genuinely likes (and is also sexually attracted to) working class men, we cannot make sense of him as he is in the final scene. Nor, I suspect, could Plomer.hopingexpecting to show the untidiness of London, have left your book untidy. —Some fallacy, not a serious one, has seduced us both, some confusion between the dish and the dinner.

I'm all for these London books of yours. They seem to me about a real town.

The Invaders was Plomer's last novel until his final one, Museum Pieces, was released in 1952. I haven't read it, but Alexander praises it as Plomer's most accomplished fiction, and also says, intriguingly:

In essence it is the story of [Plomer's friend] Tony Butts's life, told by a young female narrator. What Plomer had done in Turbott Wolfe, in making it possible for his hero to fall in love with another man by slipping the loved one into a dress, he did at much greater length, and with greater success, in Museum Pieces. (266-267)While it may be true that Plomer was most comfortable, and most successful, when writing about men from a female perspective, it would be a shame for the world to completely forget his efforts in Sado, The Case Is Altered, and The Invaders to write, however quietly, however reticently, about gay desire.

"I like that place," said Nigel.