Michael Sedano

Oscar Castillo is posing for a photographer’s lens. “Look right here into the lens,” the photog calls. Oscar can’t resist. He pulls up his own digital and fires off a frame. It’s the latest in a career of moments in chicano culture Castillo’s captured. And it’s a lesson in photography every photographer should practice: carry your camera everywhere and be liberally decisive with your shutter.

The lesson is highly explanatory for why a hundred heated bodies fill the sultry sotano gallery of the Latino Museum of History, Art & Culture housed at the Los Angeles Theatre Center. They’ve come to witness themselves and honor Oscar Castillo in a major retrospective exhibit, El Movimiento: Chicano Identity and Beyond Through the Lens of Oscar Castillo, curated by Gregorio Luke.

Castillo’s photographic work documents critical moments in United States history and Chicano culture. From Castillo's files, Luke assembles a wide selection. From the 1960s farmworker movimiento continuing into the 1970s as the urban movimiento hit the streets. From the earliest big-time gallery show of Chicano paintings to musician and folk portraits—many in color—illustrating the quiescent post-movimiento era.

Images of Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta engender mute respect. These require no comment. “Hey, that’s my prima!” a visitor calls out, pointing to an anti-Vietnam war photo. “I’m right behind that guy with the sign,” exclaims another voice. “Hey, I’m holding the sign!” Well-executed photographs bring thrilling moments of recognition like these, or, moments of serious reflection looking into the eyes of a giant.

When the frame is properly exposed. And there’s another lesson about photography coming forth as a subtext for visitors: as well as exercise a keen eye and decisive finger, know your equipment and be in the right place at the right time. As evidenced by the walls of The Latino Museum, that is Oscar Castillo’s story.

The ritual speeches begin with The Latino Museum officials taking the floor. When Jaime Rodriguez, aide to a California State Senator, takes the floor to make a Sentate Presentation recognizing Oscar's work, Oscar interrupts Jaime to bring his wife to the stage with him. It is a touching moment of well-deserved recognition. Being in the right place at the right time also means being away from home a lot, or locked away in the darkroom.

Castillo’s foto of Los Four--Gilbert Magu Lujan, Carlos Almaraz, Frank Romero, Beto de la Rocha-- documents the first Chicano artists to make the walls of the previously all-Westside all-New York Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Tonight, Magu and Beto happily pose in front of the image of their younger selves. Almaraz died long ago. Romero is probably painting in his Frogtown studio. We missed him.

Ni modo. A cross-section of Los Angeles has assembled, including a who’s who of artists.

Patssi Valdez.

Barbara Carrasco.

Mario Trillo.

Guillermo Bejarano.

Ron Arias.

Chuy Treviño. Joe Rodriguez from the old Mechicano Art Center.

Armando Baeza.

Sergio Hernandez and Diane. Several of these, along with numerous visitors, begin to join the artists for a yesterday-today portrait.

Beto’s son Zack comes in. Then Magu’s son Naiche joins the fun. Oscar makes his way over for one of those one-in-a-lifetime shots of photographer, subjects, and notable foto.

Even Beto's son comes in for foto fun. Zack, a popular musician, enjoys a moment with a happy visitor. I should have practiced my piano more diligently, I think.

I failed to get her name and email, so if anyone recognizes the woman above, please advise her to email me for a souvenir print.

Dozens of people carry cameras, from Chuy Treviño’s professional video camera to point-and-shoot digital devices. Time, place, eye and finger have as much to do with a great image as top notch technology, but there’s a lot to be said for top notch technology. Fortunately, Castillo used a twin-lens reflex 2.25” film camera before switching to the precision optics of a 35mm Nikon. Large, and high quality negatives allow the Latino Museum to create the generous prints hanging the gallery this evening. Extraordinary images require archival reproduction; do that and a print will survive 100 years with proper conservation. Which has me thinking I need to get a copy of Oscar’s shot of me. A century from now my great great grandkidlet will point to a 3-D holograph and say, “that’s a genuine Castillo and that’s my bis- bis-abuelo Michael. Have you ever seen a camera before?”

El Movimiento: Chicano Identity and Beyond Through the Lens of Oscar Castillo, is currently at

The Latino Museum of History, Art and Culture

514 S. Spring Street

Los Angeles, California 90013

News from the Latino Book Festival at Cal State Los Angeles (Press Release)

Click

here for a PDF of the Saturday and Sunday events schedule for this outstanding literary and family festival. Click the link to the organization's website at the bottom of the press release for a message from festival founder and Zoot Suit's El Pachuco Edward James Olmos.

History in the Making: The 12th Annual

Los Angeles Latino Book & Family Festival will feature 70 Latino Authors

Los Angeles, September 2009—The upcoming Los Angeles Latino Book & Family Festival, to be held at California State University, Los Angeles (CSULA) on the weekend of October 10-11, will feature an outstanding lineup of 70 Latino authors, including Victor Villaseñor, Pat Mora, Luis J. Rodríguez, Josefina López, Helena María Viramontes, Reyna Grande, María Amparo Escandón, Graciela Limón, Gustavo Arellano, Alicia Gaspar de Alba, Rigoberto González, Daniel Olivas, Ana Nogales, Marisela Norte, Montserrat Fontes, Margo Candela, Patricia Santana, Ligiah Villalobos, Julio Martínez, Héctor Tobar, Rubén Martínez, Eliud Martínez, Eduardo Santiago, Lucha Corpi, Evelina Fernández and Mary Castillo, among many others.

Special events taking place at this year’s festival include 24 sessions, such as Chicas, Chicanas & Latinas, a panel featuring some of the most promising Latina authors in the country, Latino LA: The City of Angels through Fiction, Poetry and Journalism; Barrio Stories; Chicano/Latino Thought & Art; Border Stories, Writing Books For Children, two Mariachi sessions, an editors/agents panel, and a screenwriters panel featuring up-and-coming Latina screenwriters such as Ligiah Villalobos (Under the Same Moon) and Josefina López (Real Women Have Curves). In addition, Helena María Viramontes will do a one hour creative writing workshop on the novel; Victor Villaseñor, Pat Mora, and filmmaker Robert Young will each do individual presentations. There will also be 12 Spanish workshops held throughout the day.

This year the festival will have a children’s area and stage dedicated to renowned Latina author Pat Mora’s literacy initiative “Día de Los Niños/Día de los Libros,” which she founded in 1996 to promote literacy and celebrate books among Spanish-speaking communities. The children’s stage will feature several children’s book authors and celebrities for story-time, including a 20 minute reading by Ms. Mora. In addition, The Los Angeles Theater Academy (LATA), founded by Alejandra Flores, is proud to present a play called "A Turtle Story" created by the Solano Elementary School students based on a legend from the Tongva (Gabrielino) Tribe. LATA students who participated in their after school and weekend program will also perform two songs from Crí-Crí (Francisco Gabilondo Soler). The Main Stage will feature Folklórico dance performances, singers, plays, poetry jams, and much more.

Edward James Olmos, actor and community activist, is the Co-Producer of the Latino Book & Family Festival, a weekend event that promotes literacy, culture and education in a fun environment for the whole family. Launched in 1997 in Los Angeles and organized by the non-profit organization Latino Literacy Now, the LBFF has provided people of all ages and backgrounds the opportunity to celebrate the beauty and diversity of the multicultural communities of the United States. “We are proud to be presenting so many wonderful authors at this year’s Los Angeles Latino Book & Family Festival,” said Olmos. “In our twelve year history of putting on some 45 Festivals around the country, this is the largest gathering of authors we’ve ever had. Truly, something for everyone.”

New in this year’s festival include:

- More Chicana/Latino authors – five times as many!

- A stronger partnership with California State University, Los Angeles – more support, more volunteers, more attendees!

- Support from other organizations such as Raise Literacy Campaign, Latina Leadership Network, RCOE Early Reading First

- More quality vendors/exhibitors

This year the Festival will be promoted by a strong list of media partners headed up by Telemundo and La Opinión. CVS Pharmacy will once again provide health screenings for all attendees. New sponsor Amway Global will have beauty and nutritional experts on hand for consultations (and to hand out samples).

To exhibit at this year’s festival, sponsor, volunteer or donate raffle prizes or children’s books, visit the festival’s website at www.LBFF.us For more information call 760-434-4484.

That's the middle Tuesday of the year's ninth month, a September Tuesday like any other September Tuesday, except You Are Here. Thank you for visiting La Bloga.

mvs

La Bloga welcomes your comments and observations on today's or any day's columns. Simply click the comments counter below to share your views. When you have a column of your own, a book review, a report on an arts or cultural event, remember La Bloga welcomes guest columnists. Click here to discuss your invitation to be our guest.

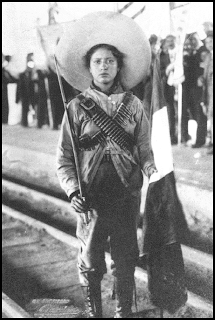

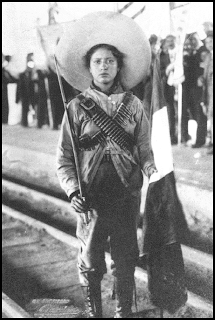

Unknown Soldaderas - Mexican Revolution

Porfirio Dias was Mexico’s president for 30 years following centuries of occupation, colonization, uprisings, invasions by Spain and France, and war with the United States. Dias’ autocratic regime gave rise to a new, industrialized Mexico, made possible by exploiting the majority of the people, stripping them of human rights while Dias built political power and personal wealth. Those who suffered most were the poor, the laborers, indios and women. In 1895, civil code was passed which severely restricted Mexican women to a life of serving their husbands, their families, and the Catholic Church.

The country was divided on these and other issues and Mexico fell into a ten-year period of chaos, with back-to-back political coups and foreign intervention. But, through the shifts in power, peasants gathered together to create a land that could serve all of Mexico’s people, including her women.This presented a conflict between traditional women who enjoyed their more domestic, subservient roles and an emerging feminism completely unknown in Mexico before. It became one of the underlying principles of the Mexican Revolution and the subject of one of the great reforms to arise from this period.

The women who stood up for higher ideals and demanded change were extraordinary, particularly given their social position and their time in history. They joined the Revolution, demanding reform across a country in disarray. Some became political voices, journalists who wrote articles opposing the tyranny of the ruling class. Some became nurses treating wounded revolutionary soldiers. Others served as spies or procured provisions for the small bands of peasants who continued fighting for freedom from 1910 until well after 1920. A few picked up weapons and joined forces, with Zapata in the south or Villa in the north, to fight along side the men. They became known as las soldaderas.

My mother, now in her late eighties, recalled the stories from her childhood in Mexico of a mysterious woman her Mama hated, a woman who came to their house to see the son she had left behind. Her name was Soledad.

For years, Soledad was described by my grandmother as a reckless harlot who irresponsibly left her child in the care of others so she could follow the revolutionary soldiers. To my grandmother, who could only view the events through the lens of her traditional upbringing, it was disgraceful. And, for more than a lifetime, only one side of the story was told. Finally, decades later, when my mother researched Mexican history, another story, long forgotten, materialized. This is my mother, Gloria's, recollection.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I was born in 1921 but I can remember from about the age of 4, our life in Mexico. Papa’s name was Juan. He was born in Linares, Mexico, located about 130 km from Monterrey City in the State of Nuevo Leon.

Juan

JuanHe was orphaned in early childhood and sent to the seminary where he got an education. He was a newspaper reporter, book binder and writer. He was also an amateur ‘novillero,’ a novice bullfighter who fights young bulls. He had a younger sister, Soledad.

My parents settled in Monterrey once they were married. Mama was quite young, about 13. In the early years of the marriage, Mama – still a child herself, loved dressing up in beautiful clothes - taffeta dresses in popular styles of the time, fur coats and gold jewelry. She wore them on Sunday outings. Papa was very active in social clubs, sports and celebrations around town. Mama, beautiful and proud, saw her life as sophisticated and special, the life she was born to live.

We had 2 maids- one to care for us children, the other to cook and clean. Our house was always spotless and it seemed very grand. There was a pond with fine little pebbles inside the house, and here I could play for hours as a child. In the back yard was a beautiful garden. We seldom interacted with Mama but rather with my Nana, because proper women of class did not bother with domestic chores. When I was bathed by my Nana, dried with clean sheets, dressed in a hand- embroidered slip, I felt like a princess.

Gloria, age 4

Gloria, age 4

The few memories of going out with Mama were of going to the tailor for new clothes of fine materials, fur trim, and adornments. Mama always wore jewels and lace and very delicate clothing. We children always had to be dressed up as well. We were like her little dolls.

The biggest problem in Mama’s life was her sister-in-law, Soledad. At the age of about 17, Soledad had become a ‘Villista,’ one of the volunteers supporting Pancho Villa in the Revolution. This was a great embarrassment to Mama. To make matters worse, Soledad fell in love with a French soldier and bore their son, Alfonso. But, instead of coming home and managing her responsibilities, Soledad continued fighting the war. Alfonso lived with us.

Between battles, Soledad nursed the wounded or went begging for food and supplies, not seeing her son for months. They say that that she would sneak to our house at night, all filthy and hungry, and want to see Alfonso. She didn’t bring money or food, and even asked for provisions to take back with her. Mama hated her for this.

Mama was not political. She enjoyed her role, surrounded by domestic affluence and security. What did she care about women’s rights? To Mama, Soledad’s uncivilized behavior represented everything coarse and disgusting in a woman. She was deeply offended by the excitement that Soledad caused when she came to the house. Finally, sick from an epidemic and malnutrition and exhaustion, Soledad’s tiny body gave out. She died and, much to Mama’s anger, her son Alfonso became Mama’s irrevocable responsibility.

Mama did not see her sister-in-law as heroic, although Soledad had fought for ten years in the harsh terrain of Mexico, ill equipped and out manned, unpaid and driven only by the shredded dream of freedom. Mama only saw the additional burden of the child she would now have to raise with her own.

Daily, Mama expressed her frustration to Alfonso, berating his mother and her foolish choices. She called his mother a whore who lived like a gypsy, bedding any soldier who would tell her she was pretty. He was lucky, Mama would say, that his mother had died. Her jealousy of the romantic and heroic woman masked for all of Alfonso’s life the courage and spirit of the mother he never knew.

A few years later, one of Papa’s cousins, who already lived and worked in the US, insisted that we come right away to take part in the opportunities and wealth just north of the border. With the pressure of our growing family, including Alfonso, it seemed the right thing to do. So, Papa took Alfonso and came to Texas first to see if it was as fantastic as it was described. And it was, in every way. Six months later, Papa came for us.

As if on a splendid adventure, we crossed the border, dressed in all our finery. It was Washington’s Birthday, February 22, 1926. I remember entering the city of Laredo, Texas like I was walking in a dream. There were fireworks everywhere and flags and people celebrating in the streets, so beautiful and exciting. I was nearly five years old.

The family settled in San Antonio where Papa was working as a newspaper reporter and started a printing and bookbinding business. And, even after a problem with our documents caused us to be temporarily repatriated, we finally established roots in South Texas and Mama believed that her life of luxury was about to become even better. And it did . . . for almost three years.

Then, the Depression came and everything crashed overnight. The stock market and jobs, businesses - everything just crumbled. There was no time to plan or adjust- it seemed like the prosperous life everyone was enjoying burst like a water pipe and everyone’s dreams just gushed out into the street.

After that, things became very difficult for Mexican people. With no jobs for the men and many mouths to feed, my Mama was forced to work beneath her class in order to survive. She learned to raise chickens so the family could eat. She made liquor to sell during prohibition. She cooked for the parish priest or made garments for women who could afford new clothes. She became a maid, cleaning Anglo women’s homes. She gave birth to 13 children but only six survived. Through it all, Mama maintained an air of the life she once had, the elegance she still dreamed of.

Many years later, I found some research on the soldaderas. I started collecting it for Alfonso because I wanted him to know that he should be proud of his mother. I wanted to tell him that Soledad was fighting against discrimination and injustice. The soldaderas had helped the revolution stay alive. They were heroes. But he died before I could talk to him about it. I don’t think he ever knew.

Alfonso 1950 My mother, Gloria 1940

My mother went on to earn a college education, in spite of her Mama’s objection. She taught school for 33 years in Texas and taught her three daughters to be independent thinkers, self- sufficient and proud of our Mexican heritage. In only two generations, women of our family were transformed from both traditionalist women of leisure and zealous freedom fighters into penniless immigrants, and finally, into progressive American women of conviction and purpose.

I dream that there’s a little of Soledad in each of us. Whether she was a silly girl following the camps or a woman of grit who heard freedom’s call to arms, we will never know. I prefer to think that she was a little of both . . . dutiful to her cause and yet romantically in love with the idea that she would spill her blood to wash away injustice.1915 My Grandparents 1960

About The Author...

About The Author... Annette Leal MatternDuring her long career in technology, Annette held numerous corporate leadership positions with Fortune 100 companies where she championed development of minorities for upper management. She received the National Women of Color Technology Award for Enlightenment for her diversity achievements and was recognized by Latina Style and Vice President Gore as one of the most influential Latinas in American business. In 2000, she left her corporate work to devote herself to women's cancer causes. She published her first book, Outside The Lines of love, life, and cancer, to help others cope with the disease. She has also been published in Hispanic Engineer and several other media. Annette serves on the board of directors of the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance and founded the Ovarian Cancer Alliance of Arizona, for which she serves as president. Annette also writes for http://www.empowher.com/. She and her husband, Rich, live in Scottsdale AZ.

Annette Leal MatternDuring her long career in technology, Annette held numerous corporate leadership positions with Fortune 100 companies where she championed development of minorities for upper management. She received the National Women of Color Technology Award for Enlightenment for her diversity achievements and was recognized by Latina Style and Vice President Gore as one of the most influential Latinas in American business. In 2000, she left her corporate work to devote herself to women's cancer causes. She published her first book, Outside The Lines of love, life, and cancer, to help others cope with the disease. She has also been published in Hispanic Engineer and several other media. Annette serves on the board of directors of the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance and founded the Ovarian Cancer Alliance of Arizona, for which she serves as president. Annette also writes for http://www.empowher.com/. She and her husband, Rich, live in Scottsdale AZ.

I failed to get her name and email, so if anyone recognizes the woman above, please advise her to email me for a souvenir print.

I failed to get her name and email, so if anyone recognizes the woman above, please advise her to email me for a souvenir print.

Thank you for such a wonderful piece of family and Mexican history. I suggest that you share the link with Somos Primos at:

http://www.somosprimos.com/

These stories are so important for our people and others.

How family stories echo in literature. Elena Poniatowska has a soldadera whose story could mirror incidents in granma's and mama's history.

http://books.google.com/books?id=xGAGAAAACAAJ&dq=inauthor:%22+Elena+Poniatowska%22

Nice post - thanks for sharing your family stories. They are very similar to stories my mother still tells, and to the stories my grandmother used to tell.

Hola Annette,

Welcome to La Bloga. Thank you for your great family story.

saludos,

Rene

What a beautiful story. Although Alfonso wasn't able to read it, we have and therefore Soledad's story will live.

Thank you so much for sharing Soledad's life (and yours!) with us.

Thanks for such a warm welcome to La Bloga. I'm honored to add a small voice to the intelligent conversation of this site.

What an extraordinary story! Thank you for sharing this.